Introduction

Recent scholarship has noted that studies of organizational control often examine existing control mechanisms in mature organizations, sometimes study just a single control mechanism rather than the entire suite of practices an organization employs, focus on “coercive” rather than “enabling” control mechanisms, and heavily emphasize formal control mechanisms (Cardinal et al. Reference Cardinal, Kreutzer and Miller2017; Chown Reference Chown2020). Scholars suggest that studies would be more relevant to knowledge-based organizations if they instead examine “how control mechanisms come to exist and operate in organizations” (Chown Reference Chown2020, 5), provide a holistic examination of an organization’s control mechanisms rather than studying a single mechanism (Cardinal et al. Reference Cardinal, Kreutzer and Miller2017, 570–72; Chown Reference Chown2020, 23), give equal attention to “enabling” control mechanisms (Adler & Borys Reference Adler and Borys1996; Cardinal et al. Reference Cardinal, Kreutzer and Miller2017, 567–69), and include informal as well as formal forms of control (Cardinal et al. Reference Cardinal, Kreutzer and Miller2017, 567).

This paper takes up that challenge by describing how the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC’s) recent reorganization of its economists into a new Office of Economics and Analytics (OEA) incorporated insights from multidisciplinary management scholarship on organizational structure, decision rights, and formal and informal control mechanisms in organizations. We document the complementary alterations in decision rights, formal control systems, and informal practices (culture) involved in a specific instance or organizational change. The FCC’s experience illustrates several key points made in the theoretical literature.

First, the FCC’s reorganization underscores how a successful organizational change initiative requires a holistic approach, with complementary changes in decision rights, formal control systems, and informal practices – not just rearrangement of boxes in an organizational chart.

Second, the reorganization provides a paradigmatic example of using control mechanisms that are enabling rather than coercive, in Adler and Borys’ (Reference Adler and Borys1996) terminology. Creation of OEA enabled economists to conduct their work in a manner more consistent with the norms of their profession. When information, analysis, and advice move upward through an agency to decision-makers, organizing professional staff by technical expertise (such as economics, engineering, and legal) helps ensure that top decision-makers hear more diverse perspectives. To ensure that economists’ perspectives would be considered, the FCC gave OEA explicit authority to advise the commission on all items with economic content. The reorganization helped enable economists to offer objective analysis by moving them into an office where they are managed and evaluated by other economists, rather than by the rule-writers whose recommendations and choices they were evaluating.

Finally, the FCC relied heavily on complementary changes in formal and informal control mechanisms. To establish formal processes for coordinating with the policymaking bureaus and incorporating economists’ input into all items, OEA capitalized on existing informal personal relationships at each level of the office and the bureaus. To ensure that economic analysis is timely and relevant, OEA built processes that paralleled and complemented existing processes of the policymaking bureaus. OEA implemented a number of other practices to promote a culture that would complement the formal structural changes. These include articulation of best practices and standards for analysis; establishment of a mentorship program for economists, data scientists, and data analysts; revitalization of a longer term research and development program to inform future policy decisions; and production of a joint memo with the Office of General Counsel (OGC) to outline the role of economics and economists in policy development.

The FCC’s economists advise on matters that come before the commission for a vote, and they also conduct longer term research to inform policy decisions. Thus, their work is almost completely knowledge work. The principles that guided the FCC’s reorganization should therefore have relevance to the study of other types of organizations engaged in knowledge production. Because this kind of organization change is notoriously difficult, the FCC’s experience may also be helpful to other agencies or organizations contemplating a similar type of reorganization involving management of technical experts.

Background

On April 5, 2017, FCC Chairman Ajit Pai gave a speech at the Hudson Institute in which he outlined his intention for the FCC to establish an office that would improve the quality and consistency of economic and data analysis across the agency (Pai Reference Pai2017). He specifically noted that “(t)he FCC’s rulemakings, transactional reviews, and auctions have direct and tangible impacts. It is therefore especially important that economics be incorporated at the beginning, not the end, of the deliberative process with respect to these functions” (Pai Reference Pai2017, 5).

The FCC’s authorizing statute vests ultimate decision-making authority in the five commissioners. The chair and the four commissioners are political appointees, nominated by the president of the United States and confirmed by the Senate. They serve staggered, five-year terms. Every year the term for one of the five seats expires, though a sitting commissioner may be nominated and confirmed for another term.

In theory, the FCC’s nearly 1,500 staff work for the commission as a whole. In practice, the chairman appoints the heads of bureaus and offices, and they in turn manage the staff. The legal, engineering, economic, and policy aspects of an issue or potential rule are analyzed and moved upward through the hierarchy to reach the office of the chairman and the commissioners. Potential rulemakings are released for public comment, with the agency following a notice-and-comment procedure, as required by the Administrative Procedure Act. The decision of the chairman and other commissioners must consider filed comments when they adopt proposed rules, and they also rely at least to some extent on research and advice from the FCC’s staff. In the typology of Katayama et al. (Reference Katayama, Meagher and Wait2018), FCC decision-making generally follows a model of “consultative centralization” rather than “authoritarian centralization.”

The new office involved a major reorganization of FCC professional staff. At the time, most of the agency’s roughly 60 economists were spread out among the Commission’s various operating bureaus, and most reported to noneconomists. The result, as Chairman Pai (Reference Pai2017, 3–4) described it, was no systematic incorporation of the economists in the agency’s policy work, a tendency for economists to work in siloes and be sidelined, little use of cost–benefit analysis or evidence-based policymaking, and inadequate collection and use of data. Chairman Pai proposed to group the economists and economic functions together in a new, centralized office, which would be managed by economists. The office was eventually named the OEA.

Soon after Chairman Pai’s speech in April 2017, a working group was formed to advise on establishing the new office. It was diverse by design. Chairman Pai emphasized the need for the working group to understand best practice in economic analysis at other agencies, in addition to the legal aspects of policymaking and the bureaucratic organization of the agency. With this in mind, the working group was made up of four experienced PhD economists with different backgrounds as well as three attorneys, one with expertise in data analysis, one from the Office of Managing Director, and one from the OGC. This diversity helped to minimize the chance of errors in implementation and maximize the chance for “buy-in” across the agency.

The working group conducted 32 interviews with existing FCC managers and staff from across the agency and 48 interviews with former FCC leadership, current and former managers of economic analysis in other agencies, and experts in public administration (FCC 2018a, 4). Based on learning from these interviews and a review of relevant literature, the working group developed recommendations for an office structure and the authorities to be granted to the office. In January 2018, the working group released a detailed reorganization plan (FCC 2018a). Later that same month, the commission voted to adopt a report and order that established OEA, along with rules that specified the authorities of the new OEA (FCC 2018b). From there, experts from various teams at the agency engaged in a nearly year-long effort to realign approximately 100 employees while coordinating with the agency’s union, Congress, and the White House.Footnote 1 The office officially began operating in December 2018.

It was clear from the outset that successfully accomplishing the chairman’s goals would require much more than moving boxes around on an organization chart. Consistent with the recommendations in the working group’s proposed reorganization plan, the commission’s rules establishing the new office substantively changed the type of analysis the economists produced. Economists were now required to conduct cost–benefit analysis on all items with an annual economic impact exceeding $100 million and to provide economic review, commensurate with impact, of smaller items. The responsibilities of the office, as codified in the rules, obligated economists to conduct objective analysis and required that they be involved earlier in the regulatory development process, so that their perspective would be considered before policy decisions were made. As the working group noted, “A separate Office also would afford the opportunity for economic analysis and data policy to gain a new prominence at the Commission. Whereas the voices of economists may sometimes be diluted in a particular Bureau, or not heard at all as policy is developed, a single Office could routinely speak with a clear voice and be heard” (FCC 2018a, 15–16).

Achieving these outcomes would require significant changes in several key areas. In addition to changing where the economists would be placed in the organization chart, effectively elevating economics required altering the decision rights that would be granted to OEA, and the practices and procedures that would be necessary to ensure that this new team functions effectively within the agency as a whole.

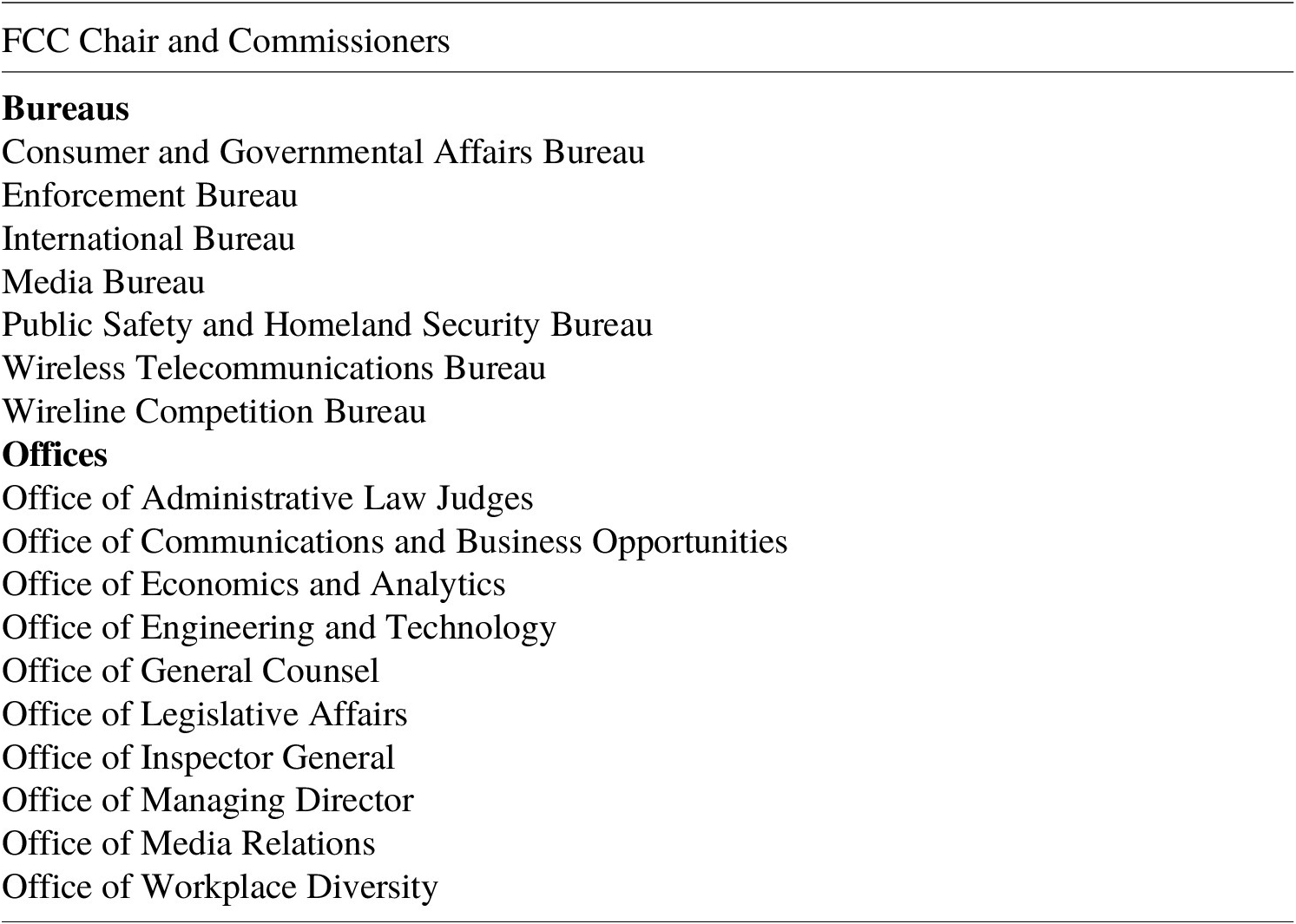

A key responsibility of the working group was proposing a way to integrate the new office into what it referred to as the agency’s structure, authorities, and practices (FCC 2018a, 4–5). Its report recommended an organizational structure for the new office that would parallel arrangements used in other bureaus and offices across the FCC. The goal of the new office was to integrate the work of economists within the agency’s existing operations. Table 1 shows the agency’s organizational chart following the creation of the new OEA. The list includes the chairman and commissioners, seven bureaus that are generally policymaking in nature and organized by industry sector or function (e.g. wireline communications, wireless communications, and media such as broadcast radio and television as well as cable television), and 10 offices that provide critical services and technical expertise in support of the commission leadership and the policymaking bureaus (e.g. general counsel, engineering, and technology). With limited exceptions, the economists previously dispersed in various bureaus and offices across the agency are now concentrated in OEA.

Table 1. FCC organizational chart

The working group recognized that a new office in the agency organizational chart would be meaningless without corresponding authorities. It therefore recommended that the new office “be authorized to carry out functions aligned with its role in providing expertise in economic and data analysis, as well as the existing functions of divisions in various offices and bureaus. These included the division responsible for conducting auctions of spectrum licenses and universal service subsidies, and the division responsible for the agency’s most significant industry data collection efforts” (FCC 2018a, 14). The working group further recommended that the new OEA take the lead in establishing agency-wide data-management policies, in close coordination with other bureaus and offices, in particular the agency’s Information Technology group.

Finally, the working group recommended a set of formal and informal practices to help the new OEA effectively carry out its duties. It noted that these practices may help address the problems identified by Chairman Pai and the working group and that otherwise might not be addressed by the new structure and authorities (FCC 2018a, 15). The working group’s discussion of practice is further broken into two categories of recommendations: improving operations and building culture, both of which are discussed below in a review of formal practices (operations) and informal practices (culture).

Organizational structure and design: Some theory

The working group’s plan and subsequent implementation drew heavily on insights from interdisciplinary literature on organization structure and control systems. An agency’s organizational structure influences “which options are to be compared, in what sequence, and by whom” (Hammond Reference Hammond1986, 382). For “advisory tasks” (such as those performed by FCC professional staff), the structure affects the information, advice, and options that reach the ultimate decision-maker at the top of an agency, who Hammond refers to as the “director.” In a relatively simple model that assumes individual subordinates have different preferences among policy options, Hammond (Reference Hammond1986, 387–93) demonstrates that one can change the outcomes chosen by the director by changing which subordinates report directly to the director or changing which individuals report to the director’s subordinates. Who reports to whom, and how information is provided to the key decision-maker(s), can determine the options considered and ultimately influence the policy decision.

Hammond (Reference Hammond1986, 405–07) also offers a stylized model of alternative ways of organizing the State Department that parsimoniously illustrates the basic choice the FCC faced in organizing its economists. Hammond assumes that recommendations come from just two types of in-country professionals: political officers and economic officers. Organizing the department by geographic regions, with both types of officers reporting to a common supervisor in each region, ensures that conflicts between the political and economic officers are resolved at a low level, and hence the economists’ advice may never reach the head of the department. Organizing the department into two divisions – political and economic – ensures that when there are significant disagreements, the top decision-maker will hear both sides’ recommendations and arguments. Analogously, organizing economists into a separate division at the FCC helps ensure that their input is received by top decision-makers.

Similarly, Froeb et al. (Reference Froeb, Pautler and Röller2009) assess theoretically how organizational structure affects the production of economic analysis to inform enforcement decisions in antitrust agencies. They examine how different structures influence the likelihood that economists will produce high-quality analysis that addresses relevant issues and is communicated effectively to decision-makers. Though focused on antitrust agencies, Froeb et al. assess the same two organizational forms employed at different times at the FCC: a divisional organization that houses separate groups of economists with attorneys in various operating divisions (like the FCC pre-2018), and a functional organization that houses economists in a dedicated economics office headed by an economist (like the FCC post-2018 OEA). They conclude that a functional organization is likely to produce higher quality economic analysis and ensure that the analysis reaches the ultimate decision-makers because the head of the economics office reports directly to those decision-makers.

In theory, a divisional organization has the potential to produce economic analysis that is more carefully focused on the issues most significant for the decision, because the economists are working side-by-side with the staff who are writing the regulation. However, the economic analysis may never reach the top decision-makers because conflicts between attorneys and economists are resolved at lower levels and a single unified recommendation proceeds up the hierarchy:

Decentralizing decision making down to the division level means that information is lost in a single recommendation. To use a metaphor from statistics, a single recommendation is not a sufficient statistic for the individual recommendations of the economists and attorneys. In other words, by combining recommendations, you lose valuable information contained in separate economic or legal analyses supporting the recommendations. (Froeb et al. Reference Froeb, Pautler and Röller2009)

Organizational design can influence decisions by altering the information that reaches decision-makers. Incorporating an understanding of organizational design predicts that an agency head who wants the agency to conduct more objective economic research and systematically incorporate that research into policy work would likely prefer a functional organization, which allows for economists to work independently, but in close collaboration with the policy-writing staff.

In practice, achieving those goals requires a functional organization that actually functions – that is, one that incorporates the elements necessary to work smoothly. More than rearranging some boxes on an organizational chart, it requires attention to the primary elements of “organizational architecture” (Brickley et al. Reference Brickley, Smith and Zimmerman1997).

Two major elements of organizational architecture are allocation of decision rights and creation of a control system that induces individuals to exercise those rights in ways that further organizational goals. Delegation of decision rights is necessary because some knowledge is costly to communicate to a decision-maker at the top of the organization. In those cases, it may be more efficient to delegate the decision-making authority to the individuals with the best knowledge, instead of moving the knowledge to the top decision-makers.

In Jensen and Meckling’s (Reference Jensen, Meckling, Werin and Wijkander1992) formulation, a decision should be located in an organization at the point where the sum of costs due to poor information (“information costs”) and the costs due to misalignment of the individual decision-maker’s objectives with the organization’s objectives (“agency costs”) are minimized. In the case of advisory work performed by FCC staff, the delegated decisions are often decisions about which policy alternatives to consider and how to evaluate them. The formal control system consists of the system to measure and evaluate performance and to establish effective incentives (Brickley et al. Reference Brickley, Smith and Zimmerman1997, 176–82).

However, not all control systems are formal; many are informal (Cardinal et al. Reference Cardinal, Kreutzer and Miller2017; Chown Reference Chown2020, 2; Ouchi Reference Ouchi1980). It is costly to foresee all future contingencies, and therefore the formal control system cannot establish a comprehensive set of predetermined rewards and punishments that covers all contingencies. Organizational culture is a set of values, norms, habits, and practices that coordinate behavior in unforeseen circumstances (Camerer & Vepsalanien Reference Camerer and Vepsalainen1988; Hart Reference Hart2001; Hermalin Reference Hermalin2000; Kreps Reference Kreps and Drew1995). While a poor culture may increase costs related to organization and management, an effective culture may reduce agency costs by motivating employees to identify as “insiders” who have adopted the organization’s goals as their own (Akerlof & Kranton Reference Akerlof and Kranton2005; Anteby Reference Anteby2008; Ouchi Reference Ouchi1980). Culture is not part of the organization’s formal control system (Cordes Reference Cordes, McElreach and Schwesinger2010, 467) but rather an “informal institution” (North Reference North1991). A key challenge of organization design is to develop a balanced system of formal and informal control systems, such that the organization “exhibits a harmonious use of multiple forms of control” (Cardinal et al. Reference Cardinal, Sitkin and Long2004, 412).

“Cultural values are ideals employees strive to fulfill, while cultural norms are the day-to-day practices that reflect these values” (Graham et al. Reference Graham2017, 1) Empirical research finds that shared perceptions of actual behavioral practices, rather than an organization’s espoused values, are better indicators of its culture (Hofstede et al. Reference Hofsteed1990). Norms that actually affect behavior are positively correlated with organizational performance, whereas stated values are not (Graham et al. Reference Graham2017, 31). Some norms commonly identified by researchers that are relevant to government organizations include “coordination among employees,” “employees are comfortable in suggesting critiques,” and “new ideas develop organically” (Graham et al. Reference Graham2017, 39).

Organizational culture has implications for the success or failure of organizational change initiatives. A new organizational structure will be more readily adopted and accepted to the extent that it is perceived as consistent with the existing organizational culture (Janicejivek Reference Janićijević2013, 40–41). This is a more general insight from the literature on institutional change. New formal institutions are more readily perceived as legitimate and accepted when they are more consistent with existing norms, practices, and customs (Boettke et al. Reference Boettke, Coyne and Leeson2008; Guiso et al. Reference Guiso, Sapienze and Zingales2015). The working group’s report recognized this, noting that it was “establishing several new practices – and reinforcing some existing ones – to directly improve how the Commission operates” (FCC 2018a, 15).

Building on the insights of organization theory but using nomenclature that corresponded more closely to administrative law and the FCC’s management, the working group’s report divided its recommendations into the categories of structure, authorities, and practices. Structure and authorities correspond to the scholarly literature’s treatment of decision rights. Some practices recommended by the working group affect formal control systems; others affect informal practices. Thus, the working group’s report touched on all three of these aspects of organization theory, although its nomenclature was somewhat different. Applying the nomenclature of organization theory, the following three sections illustrate how the FCC’s organizational change strategy and implementation paid significant attention to decision rights, formal control systems, and informal control systems such as culture.

Decision rights: Defining authorities for a new office

A free-standing economics office in an agency could potentially function as a “silo” that isolates economists from decision-making (Hazlett Reference Hazlett2011, 8; Kraus Reference Kraus2015, 302; Brennan Reference Brennan2017; Shapiro Reference Shapiro2017, 692). This risk is not theoretical, as the FCC’s organizational structure has been criticized by expert observers from across the political spectrum for relying on bureau and office “silos” that regulate by industry (e.g. media, wireless, wireline) rather than operate by function (e.g. law, economic, engineering), which makes it harder to integrate specialized knowledge (Honig Reference Honig2018, 99–105; Hundt & Rosston, Reference Hundt and Rosston2006, 31–3; May Reference May2006, 104–108). One institutional norm that attempts to thwart this problem at the FCC can be seen in the long-standing practice for its OGC to “sign off” on items that require a commission vote before such a vote takes place, thus ensuring that input is not isolated or ignored.Footnote 2 To ensure that creation of the new OEA would not isolate economists from decision-making, the FCC explicitly gave OEA similar advisory authority on specific issues.

The agency’s bureaus and offices have many attorneys in both leadership and staff roles who provide valuable legal input in addition to the guidance that is received from attorneys in the OGC. In contrast, as part of this reorganization almost all the FCC’s economists were reassigned to OEA. This means that economic expertise is almost entirely centralized within OEA, so it must be consulted to offer an economic perspective.

The January 2018 order establishing OEA outlines in section 0.21 of the CFR the following responsibilities for the office (among others, with the most relevant responsibilities highlighted here):

(c) Prepares a rigorous, economically justified cost–benefit analysis for every rulemaking deemed to have an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more.

(d) Confirms that the Office of Economics and Analytics has reviewed each Commission rulemaking to ensure it is complete before release to the public.

(e) Reviews and comments on all significant issues of economic and data analysis raised in connection with actions proposed to be taken by the Commission and advises the Commission regarding such issues. (FCC 2018b, 5)

In short, the order establishes for OEA an initial authority to review all commission-level items involving economic analysis. Froeb et al. (Reference Froeb, Pautler and Röller2009) argue that having the economists write their own recommendation memo ensures that critical information will reach decision-makers. The working group report included that recommendation (FCC 2018a, 16). In its first year of operation, OEA coordinated with leaders from FCC bureaus and offices to implement OEA review of key items as a standard practice. A cover memo on each item before the commission indicates whether the item involves any significant economic issues and whether OEA believes the draft presented to the commission deals with those topics satisfactorily (Ellig Reference Ellig2019, 27). Thus, the FCC explicitly articulated OEA’s review role, and put a specific procedure in place, to help ensure that the reorganization would make economic advice more consistently available to the commissioners.

The rule is clear that OEA is to review all rulemakings – including a more significant review of regulations with economic impacts that exceed $100 million annually – but it is less clear what other actions the office is expected to review. The chairman’s office clarified this ambiguity by deciding that any item that will come before the commission for a vote must be reviewed by OEA. For non-rulemaking items, the chairman’s office did not attempt to define an optimal allocation of authority for OEA. In effect, this meant that OEA was required to review everything that went before the commission.

In its first year of operation, OEA reviewed all commission-level items produced by the FCC’s other bureaus and offices for a vote by the commissioners. In theory, such an approach is likely to impose at least some inefficiencies as OEA staff economists review all items, including those with no obvious economic implications. In practice, the FCC may vote on two dozen items in a month, and for some of these – e.g. the agency’s assessment of a fine for a tower operator that fails to provide the required lighting for a tower – there is no obvious need for economic or data analysis.

Rather than determine ex ante a specific demarcation of which types of non-rulemaking items would need OEA review, the commission adhered to a strict standard initially. As OEA gained experience with review, and as the policymaking bureaus and offices began to build a practice of consulting with this new office, OEA coordinated with the other bureaus and offices to develop standards that worked for both sides. In 2019, consistent with the Commission’s rules, OEA reviewed all rulemakings for completeness before release to the public. For efficiency, OEA agreed to less formal review when an item clearly did not have economic issues to be addressed, or there were statutory provisions that did not provide an opportunity for alternatives to be considered as part of an economic analysis. In such cases, OEA informed the originating bureau or office to expedite the approval process within the Commission. This is now standard practice at the Commission. Table 2 shows a broad sample of these types of items.

Table 2. Commission-level items receiving expedited OEA review in 2019

If these types of items did not involve significant economic issues, one might wonder why OEA was instructed to review everything. Arguably a more efficient approach would have been for the chairman’s office to identify the non-rulemaking items with significant economic content and give OEA the authority to review those items. This approach presumes, however, that someone near the top of the FCC either already knew which non-rulemaking items had significant economic implications or could obtain that information at relatively low cost. That person would need to possess or acquire a great deal of specific knowledge about individual items and economics. When that knowledge is not centralized in a single person, it may be more efficient to move the decision-making authority to the individuals with the best knowledge, rather than moving the knowledge to a high-level decision-maker (Jensen & Meckling Reference Jensen, Meckling, Werin and Wijkander1992).

That logic also supports the decision to initially grant to OEA, rather than to the bureaus, the right to decide which items required its review. The agency’s economists have the requisite background and training (the specific knowledge) to determine whether an item has economic implications. Noneconomists were sometimes surprised to find out that actions they were working on involved economics (Ellig Reference Ellig and Konieczny2019, 27). However, given that economists did not previously have broad purview into all rulemakings, it is unlikely that the commission’s economists would have had the knowledge to specify ex ante precisely which items would have significant economic implications and which would not. Indeed, prior to the establishment of OEA, most of the economists had focused on the specific items of the bureau or office in which they were based. While it is true that some actions on their face arguably had no economic implications, drawing any line would run the risk that the list of items that OEA would have to review would be underinclusive. Further, and perhaps most notably, establishing a requirement to review everything created the incentive for OEA and other bureaus and offices to work together to identify items that could be streamlined for review due to a clear expectation that no economic or data analysis was warranted. This also ensured other bureaus and offices made it routine to always consult with OEA.

The establishment of OEA does not mean that economic considerations outweigh other considerations. The role of OEA is to develop objective and independent economic analysis to inform the commission’s policymaking. The key insight is that economic considerations should at least be heard. This is consistent with the theorists (Froeb et al. Reference Froeb, Pautler and Röller2009, Hazlett Reference Hazlett2011) as well as the practitioners who put the reorganization process in motion (Pai Reference Pai2017).

In practice, the working group and OEA leadership viewed it was essential from the outset to firmly establish a culture of objective and independent economic analysis with OEA. This means that OEA staff must deliver an objective economic assessment, even if it does not align with the direction of the bureau or office with responsibility for developing the proposed rule. The role of OEA is to develop and provide objective economic input, recognizing that policymakers may use this input however they think best. At the same time, economic analysis must be relevant to the policy discussion to be effective. In order to balance independence with relevance, OEA leadership established guidance that analysis must be subject to the constraints of laws, statutes, and Commission authorities. This cultural value of objective analysis, subject to the relevant legal constraints, also ensures that staff economists be empowered to perform objective and policy relevant analysis.

Central to this structure is a clear distinction of the roles of policymakers and economists. The role of policymakers (elected or appointed by elected officials) is to direct policy as they see appropriate. This is what they have been entrusted to do, either by the populace or the elected officials that appoint them. The role of economists, by contrast, is to inform top decision-makers on the economic implications of those policy decisions. The new organization of economists within the FCC, with appointed commissioners as ultimate decision-makers and economists functionally separated as one of the agency’s expert teams of advisors, is consistent with this approach.

Formal control systems: Building the office’s structure to match the agency’s

In addition to establishing decision rights for OEA’s managers to formally incorporate the input of economists, the creation of OEA also established an opportunity for the agency’s economists to be formally organized in a way that manages these experts (discussed immediately below), and to develop both formal and informal norms for how the ideas of these economists are communicated within the agency (discussed in the next section).

Organizing economists as managers

Prior to the establishment of OEA, economists at the FCC were seldom managed by other economists. In the largest bureaus and offices (e.g. Media Bureau, Wireless Communications Bureau, and Wireline Competition Bureau) where most of the economists were based, most economists were managed by attorneys. Each bureau had a chief economist, but the economists in the bureau did not report to the chief economist. The Office of Strategic Planning and Policy Analysis (OSP), which was folded into the new OEA, arguably operated as a consulting shop and “think tank” for the agency and had a number of economists with specialized knowledge and skills. For most of its history, however, this office was managed by attorneys or other noneconomist professionals. With the establishment of OEA, how economists are managed and supervised fundamentally changed.

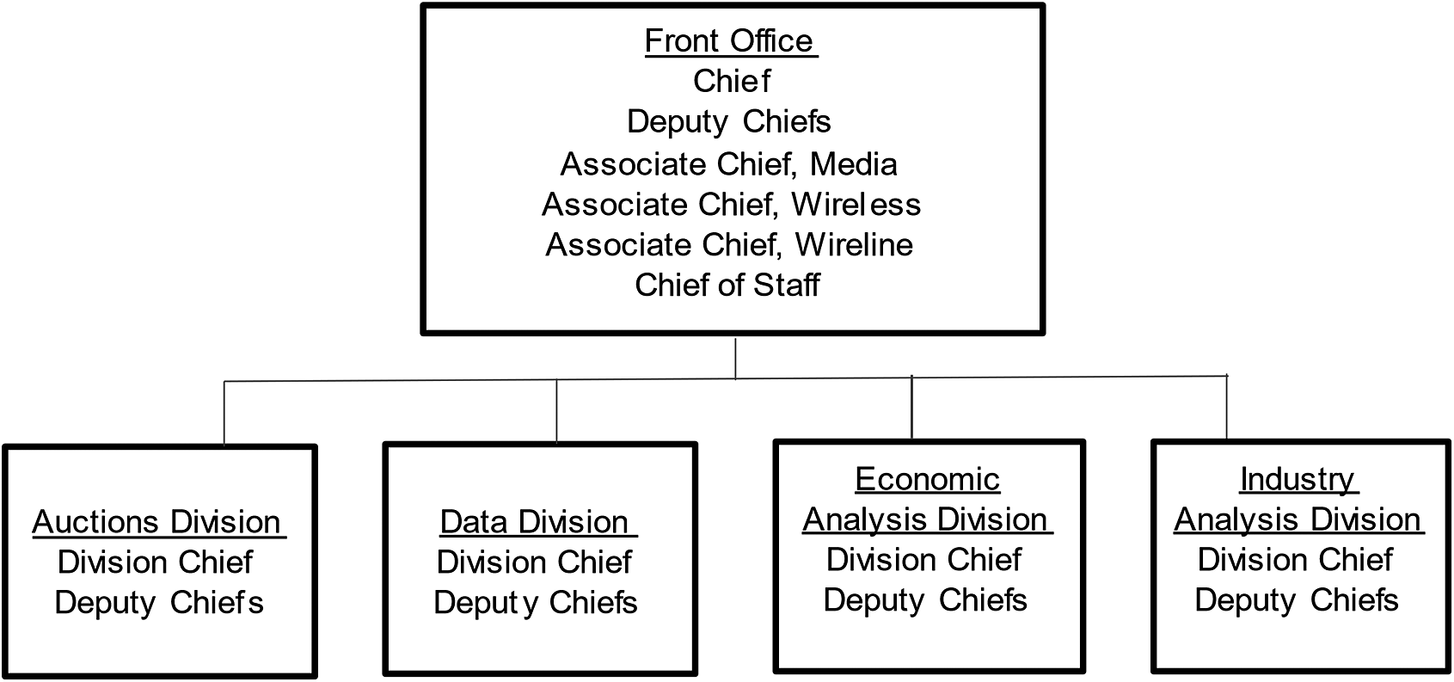

Under the new arrangement, with only a few exceptions, the FCC’s economists now work in OEA’s Economic Analysis Division, Industry Analysis Division, or OEA’s leadership.Footnote 3 On these teams, all managers except three are PhD economists. In the OEA front office, with the exception of the chief of staff and legal advisors, all of the leaders who oversee the functions of the Economic Analysis Division and the Industry Analysis Division are economists. As a result, the vast majority of the FCC’s economists are managed by economists. Figure 1 shows the organizational chart for the new office.

Figure 1. OEA organizational chart.

The management of economists by economists is especially important, given the FCC’s distribution of professionals such as attorneys, engineers and economists. In balancing the input of approximately 600 attorneys, 300 engineers, and 60 economists in a way that leads to good public policy, it is easy to see how economists might have less leverage or get less attention. Further, attorneys are prevalent throughout the agency, and thus it is easier for them to be managed by other attorneys. To achieve the same professional oversight with economists, a functional organization is required.

Almost all economists at the FCC are career civil servants and those who are not managers are covered by a collective bargaining agreement.Footnote 4 The creation of OEA did not involve any significant change in the formal criteria that govern pay and career advancement for economists. Nevertheless, the reorganization had a powerful effect on incentives that guide day-to-day behavior by ensuring that economists are managed and evaluated by other economists. In OEA, staff economists perceive that they have meaningful decision rights that allow them to point out economic issues and have them heard, and that their managers are more likely to understand the importance or relevance of issues they may raise. It is also likely that economists under this arrangement perceive that their performance is more effectively evaluated.

Interviews with (non-FCC) economists who conduct regulatory analysis in the federal government often reveal conflicts with superiors in the program office who want the economists to change their analysis so the agency’s preferred regulatory approach would look more cost beneficial (Williams Reference Williams2008, 10–12). It is a truism that pay raises and promotions in a bureaucracy depend on performance evaluations by an individual’s superiors (Downs Reference Downs1967, Tullock Reference Tullock and Rowley1965). One economist commented, “It’s very difficult to conduct a [benefit–cost analysis] if your boss wrote what you are analyzing” (Shapiro Reference Shapiro2017, 691). In contrast, an FTC inspector general’s report on the FTC’s Bureau of Economics (BE) noted, “Virtually all stakeholders interviewed recognized the importance of the BE’s purpose in providing unbiased and sound economic analysis to support decision-making, a function that is facilitated by its existence as a separate organization” (FTC OIG 2015, 9).

A separate economic office managed by economists is more likely to reflect the economics profession’s norms of objective analysis:

As in the worker-managed firm structure of academic departments at universities, incentives to improve the human capital of the professionals heavily influence institutional choices and activities. Economists are driven to provide public goods, relatively reliable estimates of net regulatory benefits, in seeking to improve their standing within the economics profession.

(Hazlett Reference Hazlett2011, 6)As one FCC economist remarked in 2019, “My job used to be to support the policy decisions made in the chairman’s office. Now I’m much freer to speak my own mind” (Ellig Reference Ellig and Konieczny2019, 26). The organizational structure is still a classic bureaucracy, but it could be characterized as more of an “enabling bureaucracy” (Adler & Borys Reference Adler and Borys1996) that helps economists better accomplish their tasks and assert their professional identity – itself a powerful form of motivation (Anteby Reference Anteby2008).

The imperative to have economists managed by economists did lead to one departure from the working group’s recommendations. The working group report recommended that in bureaus/offices in which economists served initially, the existing chief economist should remain and serve as a liaison between his or her bureau and the new OEA (FCC 2018a, 14). As critical staffing decisions were made in setting up OEA, it became clear that these bureau chief economists had relevant management and supervisory skills that were needed in the new office, and it was decided that the bureau chief economists would be based in OEA. This new role would be quite different from their previous role, which had been largely advisory. Now they would need to better understand both the theoretical as well as practical implications of their recommendations and help to provide close coordination between their former bureaus and the new office. Leaving these bureau chief economists in their policymaking bureaus also could have created tensions between those economists overseeing analysis from within the bureaus and staff economists within OEA. The former bureau chief economists were moved to OEA leadership, to serve as associate office chiefs. Their expected linkage with the bureaus from which they came, and the industry sectors in which they have expertise, can be seen in their titles: Associate Chief – Media, Associate Chief – Wireline, and Associate Chief – Wireless.

At the staff level, economists who had previously served in a bureau and developed expertise in a particular sector (e.g. media, wireline, and wireless) generally continued to work on items that focused on that sector from within OEA. In this sense, the design for the new office is similar to a consultancy, with experts who are called upon when needed. Importantly, these economists are available for work elsewhere when there is less demand for analysis in the market sector they know best, or they wish to expand their expertise. This allows for better human resource management, career advancement for economists, and also allows development of human capital as they build skills that serve different parts of the agency.

Fostering cross-functional communication

Two significant potential disadvantages of this organization by function are that the economic analysis may not be as focused on answering questions directly relevant to decisions, and economists may miss opportunities to have input into decisions at early stages (Froeb et al. Reference Froeb, Pautler and Röller2009; Shapiro Reference Shapiro2017, 692). A logical solution is that agencies with functional organization should foster linkages and interaction between economists and attorneys at all levels of the organization. Moreover, there must be processes in place to ensure that economists are brought into matters at the earliest stages, when the policy choices are initially being considered. This practice is common in the U.S. antitrust agencies, where economists are organized functionally (Froeb et al. Reference Froeb, Pautler and Röller2009).

A recent survey of economists and noneconomists in federal regulatory agencies that organize their economists functionally revealed that coordination occurs in several different ways. Some agencies, as a standard practice, include economists on multidisciplinary teams that develop regulations. Other agencies get economists involved at early stages when higher decision-makers clearly request economic input and the head of the economics office has the ear of the agency’s leadership. In still other agencies, coordination of economic analysis with regulation is driven largely by personal relationships and varies depending on the regulation (Ellig Reference Ellig and Konieczny2019, 39–40).

Beyond requiring that all items be reviewed by OEA, effective and objective economic analysis requires that the economists must be brought in early in the rule-making process. As made clear in both the working group report (FCC 2018a, 1) and Chairman Pai’s comments on the order establishing OEA (FCC 2018b, 10), cross-functional coordination at all levels and starting at the earliest stages of rulemaking was essential. Economics must be incorporated at the beginning of the rule-making process, rather than once the policy is fully developed. Without this requirement, economists cannot evaluate the potential alternative options. In the extreme, this could effectively mean economists are siloed. The goal is to ensure that input from the economists is relevant, timely, and considered.

The FCC’s approach to addressing this issue began with establishing an organizational structure in OEA that closely matched the structure in other bureaus and offices across the agency. With mirroring structures, OEA could leverage existing, and build new, personal relationships at all levels of the hierarchy to encourage communication and cooperation across functional boundaries.

Across the FCC, the bureaus that draft regulations and the offices that provide specialized expertise follow a standard organizational structure. Each bureau or office is led by a chief with an executive team (“front office”) that includes deputy chiefs, a chief of staff, and legal advisors. The bureau or office is further separated into divisions, and each division has a division chief and deputy division chiefs and anywhere from a few staff to a few dozen. Communications across bureaus and offices exist at all of these levels: bureau chief to bureau chief (executive level), division chief to division chief (middle management), and staff to staff.

As its name implies, OEA is organized as an office (rather than a bureau), a logical arrangement given that its services support policymaking and other activities that may require economic or data analysis and that may be led by any of the policymaking bureaus. As shown in Figure 1, the OEA front office includes the chief, deputy chiefs, a chief of staff, several associate chiefs who have responsibilities divided by function (which corresponds to both the bureau and the industry segment in which they hold expertise), and legal advisors.

In theory, the ideal arrangement exists when individuals at each level have a good working relationship and excellent communications with their peers at the same level in bureaus and offices (Froeb et al. Reference Froeb, Pautler and Röller2009). In practice, it is not reasonable to expect that a new office (or even a well-functioning existing office) would have consistently excellent communications with other bureaus and offices at all levels, whether in a government agency, a corporation, or any other type of organization. Keeping this in mind, managers can try to play to their strengths, drawing upon the best relationships or the clearest lines of communication to raise the probability that the new economics office understands the issues to which it should contribute and the areas in which it should add value.

With regard to the organization of the executive team (front office) of OEA, the structure appropriately addresses the need to have continuous engagement with other bureaus and offices at high levels, ultimately with the goal of ensuring that economist input is relevant and timely. It is common for strong professional working relationships to be built across these levels in the organization – senior leadership, middle management, staff – and for these relationships to play an important role in how the agency ultimately does its work. Those at the executive level interact with each other in the course of coordinating rulemakings that cut across their various teams and in senior management meetings with the agency’s top leadership (i.e. the chief of staff and/or chairman). Those at the division level, including many staff, also are likely to engage their counterparts in other bureaus and offices when working on items that cut across their teams, as is common. Among the attorneys, economists, engineers, and other professional staff who may spend much of their careers in the agency, many long-term professional working relationships are formed. Leveraging these preexisting informal relationships was critical in setting expectations that OEA fit into the preexisting culture of the FCC.

While each bureau or office adheres generally to the organizational structure described above, this does not mean that OEA’s coordination with each bureau or office is identical or guaranteed. OEA leadership worked hard to establish relationships with their counterparts. Once these relationships existed, OEA leaders worked hard to establish cultural norms and processes that dictated OEA be consulted early. Front office executives and divisions chiefs communicated with their counterparts in the other bureaus and offices to communicate how OEA was consistent with the existing organizational culture of the agency and why economic review would strengthen their policy and rulemaking goals. OEA leadership worked directly with individual offices and bureaus to develop and maintain mutually agreeable best practices to ensure OEA would be brought in early.

OEA leadership also recognized that each relationship with other bureaus and offices will be unique. At least two (probably more) conditions explain this result. First, the nature of the work performed (or industry segment regulated) by a particular bureau or office may make the input of an office dedicated to economic and data analysis highly valuable (and welcome) in some cases, whereas in other cases such analysis may be seen as less valuable or relevant (and less welcome). Second, the managers of a given bureau or office may have better or worse relationships (or simply be more or less familiar) with OEA managers than their peers in other bureaus or offices. These factors may determine when, how, and at what level a particular item is coordinated between OEA and another bureau or office.

For example, for a given item, OEA’s leaders may have a close working relationship with the bureau or office in charge of that item or see a pressing need for top-level coordination because of the nature of the economic or other issues at hand. For another item led by a different office or bureau within the agency, OEA middle management (i.e. division level) may take the lead on coordination. In addition, professional relationships that predated the formation of OEA may facilitate the coordination of items in many cases. To the extent possible, establishing open communications at all levels creates important redundancies in coordination that ensure OEA is brought in early on rulemakings.

Informal control systems: Fostering culture to align expectations

The best-designed organizational structure will fail to produce consistent and relevant results without informal systems – in effect, a culture – that nurture and reinforce the formal control systems. The FCC’s reorganization includes some of the most important informal elements. The working group’s plan discussed structure, authority, and practices. The category of practices includes many informal elements that are not covered under structure and authorities:

By “practices” we mean the use of new activities, processes, or tools that can improve the way the Commission goes about its work. These practices seek to address problems that we have identified but that may not be adequately addressed by the new Commission structure and OEA authorities alone. These practices also may help to create a culture that values collaboration across the agency, a consistent application of economic thinking, and ultimately, an environment that promotes sound policy to the benefit of the American public.

(FCC 2018a, 15)Over time, consistently reinforced practices serve to build a culture that helps make the structure and authorities work effectively (FCC 2018a, 15). Below, we list the practices that the FCC working group considered to be especially important for the FCC’s reorganization and discuss the steps taken to foster such informal controls during OEA’s first 18 months of existence.

OEA should establish expectations and standards for economists and data professionals to ensure high-quality analysis.

The Office of Management and Budget has issued guidance for the conduct of regulatory impact analysis by executive branch agencies (OMB 2003), and numerous agencies developed their own guidelines on best practices for analysis of regulations specific to each agency (see, e.g. DOE 1996, EPA 2010, HHS 2016, USDA 1997). OEA’s leadership team, including the agency’s chief economist, developed a set of best practices for economists and other professional staff assigned to this office. These best practices include guidelines for conducting specific types of economic analysis that are useful and relevant for FCC regulatory decisions, in particular cost–benefit analyses and merger reviews. The best practices also include a description of the agency’s peer review process.

OEA should develop a program for mentorship and training of economists, data scientists, and data analysts by their peers and more experienced staff.

The best practices developed by OEA’s leadership team include guidelines for staff development. These guidelines do not substitute for formal employee performance evaluations that are required for all nonmanagerial staff at the agency, and which determine eligibility for promotions. Rather, these are optional guidelines to help economists and other professionals in OEA to grow professionally. They build on the agency’s established human resources practices while simultaneously encouraging staff to take advantage of supplemental materials as well as mentorship opportunities. The supplemental materials range from internal memorandums on how to determine the level of economic analysis to be applied to particular item, how to double check the quality of one’s work, and how to work productively with other staff (within OEA and across the agency) to effectively incorporate useful economic or data analyses. In addition, OEA leaders encourage staff to take advantage of classes offered by the agency’s highly competent training team (known as FCC University), with courses that include project management, professional communications, organizational leadership, conflict resolution, and other valuable skills. The mentorship initiatives include optional pairing of new staff with senior staff members who volunteer to help them develop institutional knowledge as well as early-career skills, and opportunities for staff with specific and highly valuable skills (e.g. expertise with an important statistical package) to mentor peers who wish to acquire or improve in such skills.

OEA should revitalize longer term research programs, with a focus on producing peer-reviewed white papers for public release.

The reference to a “revitalized” research program is consistent with Chairman Pai’s observation that the FCC’s economists have a long history of producing quality research on emerging issues that helps produce better informed policymaking, and that the new OEA should build on this tradition. For example, an FCC working paper by Kwerel and Felker (Reference Kwerel and Felker1985) explained how auctions could be a more efficient way of assigning spectrum licenses than the FCC’s other methods: comparative hearings or lotteries. Kwerel and Williams (Reference Kwerel and Williams1992) estimated consumer benefits of $1 billion from allocating spectrum for a third cellular telephone system in Los Angeles, an estimate that helped demonstrate the value of auctioning spectrum licenses, later authorized by Congress. Kwerel and Williams (Reference Kwerel and Williams2002) proposed two-sided spectrum auctions to encourage incumbents to relinquish their licenses for higher valued uses, which was later authorized by Congress and implemented by the FCC with an auction that compensated television broadcasters for returning spectrum usage rights that were then made available to mobile broadband providers. DeGraba (Reference DeGraba2000, Reference DeGraba2002) showed how an interconnection regime in which terminating networks were not allowed to charge interconnecting networks for termination could be efficient, thus providing an efficient default regime if telephone networks negotiating interconnection terms cannot reach an agreement, and the FCC utilized this analysis when it adopted “bill and keep” interconnection rules.

OEA’s leadership team, along with the agency’s chief economist, placed renewed emphasis on research, reminding staff of the FCC’s past history of producing quality research as well as Chairman Pai’s commitment to such research. In the first year of operation, OEA published two white papers (Ellig & Konieczny Reference Ellig and Konieczny2019; Carare & Kauffman Reference Carare and Kaufman2019) and established a pipeline of research for future years.

OEA should organize studies, workshops, roundtables, advisory committees, or other fora as needed to learn about or present information about emerging issues or policy challenges.

Like the recommendation on the working paper program, this recommendation called for more extensive use of existing practices. Many of these activities had been organized under OSP, which was to be incorporated into the new OEA. The working group observed that “[t]his wider strategic role, currently maintained by OSP, should be continued in OEA” (FCC 2018a, 17). In addition to revitalizing the working paper series, OEA continued OSP’s long-running tradition of inviting outside researchers to present academic papers before economists and other FCC staff. This outside research tends to focus on economic issues in telecommunications markets, or in markets with lessons that are applicable to telecommunications. In addition, OEA instituted a new series of presentations with information of value for all staff, not only economists. The subjects presented range from the fundamentals of new technology (e.g. 5G) to introductions to key Commission programs (e.g. auctions, universal service) for staff who work in other areas but could benefit from a working knowledge of these programs.

The new OEA and the OGC should jointly produce a memo on how economic analysis should be incorporated into the agency’s decision-making processes.

In 2012, the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) general counsel and chief economist produced a guidance memo on how economic analysis should be conducted and how economists should be involved in regulatory development (SEC RSFI & OGC 2012). Significant improvement in the quality of SEC economic analysis ensued (Ellig Reference Ellig2020). The FCC’s working group report recommended that the leaders of the FCC’s OGC and OEA should develop similar guidance for the FCC. In its second year of operation, OEA jointly produced with the OGC an agency-wide guidance memo on the use of economic analysis in commission items. As the report recommended, this memo helps to establish general expectations for when and how OEA staff are to be included on project teams, indicates the extent to which economic analysis is expected for rules with different levels of economic impact, and outlines the main elements to be covered in such an analysis. It also explains why thorough economic analysis advances the FCC’s mission and is often necessary to uphold FCC regulations in court.

Many of these expectations and guidelines are informal, in the sense that they are not incorporated into the formal employee performance evaluation system. At the FCC, a nonmanagerial employee’s performance review ties to other factors already established after significant coordination between the agency and its union. The informal factors discussed above, therefore, will not be tied directly to such reviews. This does not mean they do not impact OEA’s performance. These guidelines and expectations seek to encourage an organizational culture that provides guidance and coordination in situations that the formal control system does not address – the classic role of organizational culture described in management literature.

Conclusion

When Chairman Pai (Reference Pai2017) announced the goal of creating OEA, he cited a multi-billion-dollar example of the good the FCC accomplished in the past when it allowed its economists to engage in long-term research and development and then followed their advice. FCC economists played a key role in turning Coase’s (Reference Coase1959) concept of spectrum license auctions into a specific policy the FCC could implement to foster competition in wireless communications services. First authorized by Congress with bipartisan support in 1993, spectrum auctions raised more than $100 billion for the U.S. Treasury and created even more value than that for the consumers who use wireless services. Former FCC chief economist Thomas Hazlett (Reference Hazlett2017, 217–18) estimated that the annual value of wireless voice service to consumers exceeded the $141 billion they paid for the service by more than $200 billion in 2008. That figure does not even include the value of wireless Internet service, which exploded after 2008. The example of spectrum license auctions demonstrates how an agency can achieve significant public benefits when it uses economic analysis effectively. The creation of OEA is a bet that the future public benefits of more effective economic analysis, which may endure for generations, will outweigh the administrative and organization costs that the agency and its staff have incurred to make this more-effective operation possible.

The term “reorganization” most readily brings to mind shifting boxes on an organizational chart. Yet the FCC’s reorganization of economists was much more extensive, involving complementary changes in decision rights, formal control systems, and informal control systems – that is, informal practices intended to influence organizational culture. The FCC’s example illustrates how an organization can take a holistic approach instead of just changing one control mechanism, enable knowledge workers to perform their work in a manner more consistent with their professional values, and adopt a balanced blend of formal and informal control mechanisms.

The FCC did not just create a new office to house its economists; it conferred decision rights on that office that economists had not previously been able to exercise. OEA received the right to review and advise on all items voted on by the commission. The rule establishing the office obligated it to review all rulemakings, review all items with content relevant to economics or data analysis, and prepare a rigorous benefit–cost analysis for all rulemakings with an economic impact of $100 million or greater. These changes were essential to integrating economic analysis into the FCC’s processes.

Formal control systems also changed. The FCC’s economists now report to and are managed by other economists. This change gives economists greater freedom to conduct objective analysis and helps create the expectation that they will do so. To encourage economists to keep their work relevant to rulemaking and other practical activities, OEA was structured in parallel fashion to the policymaking bureaus, and personnel at each level are expected to develop working relationships with their counterparts in the policymaking bureaus with which they collaborate.

Finally, the reorganization addressed day-to-day practices and culture. Some initiatives sought to implement successful past practices more consistently, such as the long-term research and development efforts represented by the working paper series and interactive events such as workshops and roundtables. Others sought to implement new practices that support the more formal structural changes. These include establishment of expectations and standards for analysis, mentorship programs, and articulation by OEA and OGC of the role of economists and economic analysis in decision-making. In addition to the greater rights and formal control systems, OEA established processes for coordination that were consistent with the existing organizational culture of the FCC. OEA leadership also leveraged informal relationships at all levels of hierarchy to communicate continuously with other policy bureaus and offices. In so doing, OEA ensured that economists are brought into matters at the early stages in order to be able to provide timely economic input.