In 1973, the front page of a major East German newspaper reported that ‘urgent help had arrived by plane from Moscow’. Three weeks earlier, so the article read, the Berlin transplantation centre had received a donor kidney from the Soviet Institute for Experimental and Clinical Surgery and transplanted it to a 37-year-old worker suffering from end-stage renal disease (ESRD), who had recently left the hospital fully restored to health.Footnote 1 If this incident of medical co-operation seems to have occurred within the expected realms of official German-Soviet Friendship, another press item from 1977 tells a more complex story: for the kidneys of a brain-dead person in New York with the rare blood group AB, no recipient could be found in the United States or through the West European Eurotransplant organisation. The well-connected East German transplantation surgeons had learned about this opportunity, and thanks to excellent Czech-German co-operation within the socialist Intertransplant organisation, one US kidney had finally been transplanted to a Czech citizen.Footnote 2

These two samples of state-socialist journalism reflect the mixed messages that generally can be found in the coverage celebrating transplantation as an outstanding achievement. On the one hand, clinical kidney transplantation became a showcase for Cold War competition and the global comparison of health care systems. On the other hand, international collaboration created opportunities to be recognised as an advanced, peaceful society and to gather knowledge about the latest developments. As organ transplantation represented one of the most advanced areas of biomedicine, it signalled the GDR’s modernity and competitiveness to the world and promised East German citizens that health care would not only be universal and free but would also meet international standards.Footnote 3

Still, the two articles cited above raise several questions with regard to the international dimension of this endeavour, especially if seen against the backdrop of the GDR’s relative isolation in the global political arena in the 1950s and 1960s. How did the GDR get involved and participate in the interconnected networks of knowledge, data and organ exchange in ESRD treatment? In what ways did the domestic system of kidney transplantation depend on intra- and trans-bloc exchange? Where did the GDR profit, and what did it have to offer on an international scale, both in the First and the Second World? And how did this complex, resource-intensive, specialised area of medicine resonate with the more general outlook of East German foreign policy?

My chapter will draw on current historiography, which puts the GDR in a transnational perspective. The obvious starting point has been inter-German histories, which showed that despite the marked ideological and political rivalry – including the West German policy of isolating the GDR internationally – many parallels, convergences, and entanglements can be observed in the field of medicine and health care.Footnote 4 Recently, a new focus on the GDR’s relations to the Global South has emerged, often again in comparison with the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG).Footnote 5 In contrast, health-related intra-socialist connections and interchanges, as exemplified by the Intertransplant project, have only just begun to be investigated. I can build on several studies that have followed trajectories of medical knowledge, people, and objects that multidimensionally connected the GDR to Western, Eastern, and Southern states, as well as to medical companies and international agencies, such as the World Health Organisation (WHO).Footnote 6

As kidney transplantation has been historically defined by the interplay of ‘activities, participants, and structures at transnational, national, and local levels’,Footnote 7 it offers an excellent opportunity to broaden our understanding of those complex interactions and their changes over time. On a national level, different medical disciplines and institutional actors had to interact in the creation and maintenance of a kidney transplantation system; apart from the kidney transplantation centres, this included decentralised infrastructure for chronic dialysis, immunological laboratories for tissue typing, committees for the determination of brain death, and surgical teams for organ procurement.Footnote 8 In the 1960s, when clinical ESRD treatment was new and resources were limited everywhere, advances in any of these different fields mostly arrived through learning from abroad. Theoretical and practical knowledge was disseminated from a few pioneering centres around the globe, via person-to-person contacts, and through emerging cross-border professional communities, such as the International Society of Nephrology (ISN, 1960), the European Dialysis and Transplant Association (EDTA, 1963), and the International Histocompatibility Workshops (1964). I want to investigate how GDR physicians interacted with this unfolding international landscape and how their expectations and the stakes shifted during the 1970s and 1980s against the backdrop of general developments, such as the GDR’s international standing or the structural crisis of public debt.

My story relies on a specific accumulation of documents that characterised socialist statehood in East Germany. One main group of records originates from the Ministry of Health Care, which extensively monitored and controlled the activities of physicians and medical associations. The same goes for the documents of the Ministry of State Security. Several key players in dialysis and kidney transplantation were approached to report as unofficial informants to the secret police (and were likewise spied on by their colleagues). What we do not find are indications of illegal organ trafficking, neither with regard to East German citizens nor non-citizen residents or transit travellers between the German-German border and West Berlin. The absence of such documents does not mean that nothing illegal or unethical happened.Footnote 9 However, the focus of my article will be on official, legal, and non-commercial kidney transplantation.

The first subchapter will introduce the key medical players who held major positions in ESRD treatment and travelled extensively. I will then outline how the immunological understanding of transplantation encouraged trans-border co-operation early on, followed by a sketch of how Intertransplant was established. East German kidney exchange activity will be analysed and placed in a wider context of exchange relations before conclusions are drawn for the overall questions of this special issue.

‘Three red musketeers’

Recent historiography has shown that international and transnational medical exchange in state-socialist countries very much depended on mobile individuals, oftentimes professionals and scientists who were travel cadres and were well-connected both in the domestic arena and with their peers abroad. Though committedly or opportunistically promoting the advancement of their home country and the ‘socialist camp’, they usually had a professional agenda of their own, which did not neatly coincide with the supposedly unified state interest or party line.Footnote 10 This observation holds true for East German ESRD treatment as well. Its story can be told through the lens of some of those medical diplomats, dubbed the ‘three red musketeers’ by their Western colleagues when they entered the international arena in the 1960s.Footnote 11

If you had to single out the one most important figure in East German kidney transplantation, it would be urologist Moritz Mebel (1923–2021). He led the team that performed the first successful East German kidney transplantation in 1967, kicking off the national kidney transplantation programme. In 1969/70, he was the founding director of the first kidney transplantation centre based at the Friedrichshain Municipal Hospital in Berlin, to be followed by centres in Halle (1974), Rostock (1976), and at the Charité University Hospital in Berlin (1983). With the Friedrichshain centre serving as headquarters for all of the GDR, Mebel was de facto chief co-ordinator of kidney transplantation, despite the fact that he was only officially appointed the Minister of Health Care’s Representative for Kidney Transplantation in 1983, after he had become head of the Charité Urological University Clinic.

However, as Mebel himself pointed out, it was nephrologists who first initiated international contact with colleagues in non-socialist countries.Footnote 12 A pioneer in both respects was Harald Dutz (1914–2010), who started haemodialysis at the medical clinic of Rostock University in the late 1950s. Summoned back to the Charité in East Berlin to compensate for the exodus of many high-profile physicians, he headed the Charité’s Second Medical Clinic from 1962 until 1979 and helped to establish a nationwide network of dialysis centres. Back in Rostock, Horst Klinkmann (b. 1935) had started his clinical career under Dutz and contributed a marked interest in the technical aspects of dialysis. From 1974 until 1989, he was head of the medical clinic at Rostock University and enjoyed the leeway that the distance from the capital allowed. Due to his managerial qualities and international networks, he was appointed president of the Council for Medical Sciences in the GDR in 1982.Footnote 13 In comparison with these three, the haematologists at the Berlin District Institute for Blood Donation and Transfusions, who managed the East German immunological reference laboratory, played only a secondary role.

Mebel, Dutz, and Klinkmann not only represented two medical subdisciplines and different aspects of ESRD treatment, but they also covered different geographical areas when it came to international co-operation. Mebel’s biography inclined him towards the Eastern bloc: born into a Jewish communist family with origins in Eastern Europe, his parents had left Germany in 1932/3 to raise their children in the Stalinist Soviet Union. In the 1940s, Mebel volunteered for the Red Army, studied medicine in Moscow, and qualified as a urologist before returning to Germany in 1958. He identified a hundred per cent with the German socialist state project.Footnote 14 After his retirement, in 1986, he was elected to the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party. Due to his impeccable ideological record and political connections, he was in a position to pressure the health administration, though not always successfully. Fluent in Russian language and culture, he guaranteed access to decision makers in Moscow and ensured friendly relations with colleagues throughout Eastern Europe and the socialist Global South (without his network being restricted to socialist countries).

Harald Dutz, in contrast, was not a natural supporter of the GDR, but as a highly sought-after professional, he was flexible and loyal enough to earn himself a distinguished clinical career and influential positions. His correspondence testifies to diligent cross-border networking, supported by his closest international ally, Swedish pioneer of blood cleansing treatment Nils Alwall (1904–1986), who was on friendly terms with peers in both East and West and a key figure in international co-operation in ESRD treatment.Footnote 15 Horst Klinkmann represented an even more profiled Western orientation. In 1969/70, he spent a year at Willem Kolff’s (1911–2009) clinic in Salt Lake City, a major hub for the development of artificial organs. Having returned to the GDR without hesitation, he capitalised on the language skills and connections he had acquired, both in the academic field and with Western producers of dialysis technology.

Each of these figures had their own agenda, but they managed to combine their efforts productively. In 1967, Dutz and Mebel convinced the Ministry of Health Care, as well as state and party leadership, to set up a state-sponsored nationwide dialysis programme, following the model of Sweden and the UK, which was a prerequisite for the transplantation programme.Footnote 16 In the competition for financial, human, and technical resources in medicine, they successfully lobbied for a treatment that benefitted only a comparatively small number of patients. Likewise, Mebel, Dutz, and Klinkmann complemented their respective strengths when it came to fostering international ties.

Collaboration as a (perceived) necessity: The HLA system, tissue typing, and the beginnings of organ exchange in Europe

In the 1960s, kidney transplantation evolved from an experimental into a clinical treatment of ESRD in the Global North. Chronic renal failure was the first fatal disease that became manageable through a combination of long-term dialysis and transplantation. Working together over spatial distances and exchanging between different health systems were considered necessities from the start, surpassing the usual level of international collaboration in medicine.Footnote 17 The reason for this was the problem of tissue incompatibility that would make the immune system of the recipient reject the transplanted organ if tissue profiles differed too much. In the late 1950s, the first human leukocyte antigen (HLA) group was described. It was but a small sector of the vast and highly variable major histocompatibility complex, a series of genes located on the sixth chromosome. This anti[body-]gen[erating] molecular structure was found to bind antibodies during an acquired immune response.

The expansion of kidney transplantation as a regular clinical treatment meant that organ donation from living relatives with similar tissue profiles would not provide kidneys for every patient in need. With local deceased non-relatives, so-called cadaveric donors, on the other hand, tissue compatibility was unpredictable and improbable in most cases. Thus, in order to expand kidney transplantation, two approaches seemed possible. One was to suppress the natural immune response with radiation or pharmacologically. Effective immunosuppressive drugs had been in use since 1963, but the therapy was still unspecific and put the transplanted patient at a high risk of dying from a serious infection. It was not until the early 1980s that the new drug cyclosporine A would largely solve this problem. The other option was finding ‘good matches’ in the multitude of possible combinations between donor and recipient tissues. In particular, European transplantologists believed it necessary to ensure at least a certain degree of HLA compatibility, though the significance of the HLA-D region in this process was properly understood only in the 1970s.Footnote 18

Before matching could be put into practice on a clinical scale, the HLA system had to be mapped bit by bit in a common effort of international division of laboratory labour.Footnote 19 In 1964, the first International Histocompatibility Workshop kicked off a series of meetings that aimed at detecting and characterising HLA loci and defining antigens. Eventually, a worldwide standard of HLA nomenclature, typing sera, and typing techniques was established. Even if this definitory work was dominated by some twenty laboratories from a handful of countries, many more contributed by obtaining and providing different typing sera, the necessary reagents, including laboratories from the Soviet bloc.

As the contours of the HLA system and the distribution of its variants among populations began to emerge, it was estimated that a pool of at least several hundred potential recipients would be needed to find a good match for a cadaveric kidney.Footnote 20 This meant that the patient pool of a single hospital or even a single city would be way too small. Therefore, transplantation pioneers started to recombine their growing patient pools into larger entities. In the wake of the third Histocompatibility Workshop, held in Italy in 1967, one protagonist of early immunogenetics, Dutch haematologist Johannes van Rood (1926–2017), launched the first European exchange organisation. The Eurotransplant foundation was meant to be a registry of potential recipients to optimise HLA matching. It was housed at the blood bank of Leiden University Hospital, which was the reference laboratory and co-ordination centre for transplantation in the Netherlands.Footnote 21 Transplantation centres from the Netherlands, Belgium, West Germany, and Austria joined (as did Luxemburg in 1982) to exchange patient data and organs. Following this example, Scandiatransplant – for the Nordic countries – and France-Transplant were founded in 1969. In the UK, the National Organ Matching and Distribution Service was established in 1972, as was the North Italy Transplant Program.Footnote 22

What did the exchange programmes do? Basically, they assembled, stored, and updated immunological and clinical information on potential kidney recipients, i.e. patients who were on chronic dialysis but otherwise healthy enough to undergo surgery at any moment. Transnational networks like Eurotransplant received this data input from the national waiting lists. The second basic function of the programmes was to act quickly when the critical moment arrived: when fresh kidneys were reported, the co-ordination centre would start the recipient selection procedure, which, from the 1970s, was not carried out by human decision makers but by computer algorithms. The model was the famous Eurotransplant computer programme, promising fair selection based on medical possibilities and urgency alone. If no matching recipient could be found in their own database, the organ would be reported to interconnected exchange programmes, e.g. from Eurotransplant to Scandiatransplant. To be sure, the choices that fed into the algorithm were man-made and represented another task in the portfolio of the exchange organisations: the background work of standardisation and quality control. What were the criteria for the acceptance of a patient into the waiting list? How was medical urgency defined? Which tissue incompatibilities should be tolerated? Documentation and research were constant activities, especially for Eurotransplant: defining typing techniques and reagents, assembling and evaluating data on the outcomes of transplantation, and making recommendations for treatment based on such evaluations.Footnote 23

Here, Eurotransplant overlapped with the major professional association in the field, the European Dialysis and Transplant Association (EDTA, from 1981 EDTA–ERA (European Renal Association), later ERA–EDTA, now ERA). Its most important output were annual statistical surveys on dialysis and transplantation activity in centres which were willing to share their data. Eventually, Eurotransplant and Intertransplant would streamline their data gathering with the annual EDTA reporting.Footnote 24 The EDTA Registry displayed the joint progress in the field of kidney replacement therapy, but it also ranked countries according to their performance in graft and patient survival rates and the ratio of dialyses and transplantations per million inhabitants – a striking example of ‘competition through co-operation’.Footnote 25 East German physicians were eager to participate from early on – Dutz, Mebel, and Klinkmann were among the first socialist members – and during the 1970s, centres from all over Europe and from non-European countries bordering the Mediterranean contributed to what became the WHO reference statistics in the field of ESRD treatment.Footnote 26

Geographical outreach that went beyond formal membership similarly characterised Eurotransplant statistics, which knew three categories of exchange partners: the core of participating centres in the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, the FRG, and Luxemburg; sister organisations in Switzerland, the Scandinavian countries, France, and the UK; and a wider circle of ‘others’ in Europe and beyond, namely Italy, the GDR, the USA (from 1976), Iran (1977/8), Israel, the USSR, Czechoslovakia (from 1977), Turkey (from 1978), Spain, Greece, Poland (from 1979), Yugoslavia, Hungary (from 1980), Kuwait, Canada, Portugal (from 1981), and Saudi Arabia (from 1984).Footnote 27 Interestingly, individual state-socialist countries appear in Eurotransplant reporting, but its socialist counterpart, Intertransplant, is never mentioned. In 1984, there were still no official connections between the two.Footnote 28 This raises the question of what Intertransplant looked like from the inside.

The making of Intertransplant: an East German perspective

The Intertransplant scheme was created as an adaptation of the multilateral Eurotransplant model to state socialism. Therefore, unlike Eurotransplant, Intertransplant was not a civil society initiative but evolved as a result of central planning. While Eurotransplant was realised through contracts between the Dutch foundation and individual members – the dialysis and transplantation centres – Intertransplant was a treaty between states, represented by the respective ministries of health care. It was signed by Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, the GDR, Hungary, Poland, and the USSR in November 1980, joined in the following years by the non-European members Cuba, Mongolia, and Vietnam, and dissolved on 1 January 1991.Footnote 29

However, the process of establishing Intertransplant had begun a decade before. As early as 1968, when ‘first’ transplantations had been carried out in several countries or were underway,Footnote 30 the emerging state-socialist transplantation community started a conversation about joining their efforts. In 1969, nephrologists and urologists from the GDR, Hungary, Bulgaria, Poland, and the Soviet Union requested that their ministries of health care put the topic on the agenda of the regular conferences of socialist health ministers; they proposed installing a transnational expert group that would suggest a framework for collaborating on transplantation.Footnote 31 From 1970/1, the name ‘Intertransplant’ was used.Footnote 32 In parallel, bilateral organ exchange began to materialise between socialist states on the basis of Friendship Agreements, which allowed physicians, scientists, and technicians to visit health care facilities in the partner country and medical associations to organise joint conferences. GDR transplantologists also hoped to establish formal exchange ties with Sweden through the support of Nils Alwall, but they did not materialise.Footnote 33 In 1971, East Germany shipped the first two organs abroad. No matching recipients had been found for the kidneys of an accident victim in Berlin, so they were transferred to Prague and transplanted to two Czech patients. In an interview, Moritz Mebel referred to the ‘“Intertransplant” organisation’ enabling this life-saving mission.Footnote 34 Even if an Intertransplant spirit was undoubtedly already there, it seems that it was bilateral relations that initially facilitated this transnationalism in socialist kidney transplantation.

Even if Czech-German affiliations in medicine went back for decades, it is nonetheless remarkable that it was this duo which started the actual organ exchange. After the military suppression of the Prague Spring, which the GDR leadership fully supported, attitudes towards East German dialysis physicians had been rather hostile in Prague, to the extent that artificial kidneys produced in the GDR were put out of service.Footnote 35 Following the hint of a Polish colleague, an immunologist from the East German reference laboratory refrained from going to Eurotransplant headquarters for training, ‘as a rejection on [Johannes van Rood’s] part may be expected in connection with the events in the ČSSR’.Footnote 36 Repercussions had also been felt in international organisations, regarding East Germany’s ambition to host the annual conference of the EDTA and to be accepted into the ISN. In 1968/9, the Czech member of the EDTA council, nephrologist Albert Válek (1925–1995), stated that he would never agree to the GDR being nominated as a conference venue, as did several members from Western countries.Footnote 37 Later in 1969, Válek came around, and thanks to Nils Alwall’s intervention, the GDR was nominated as a host for the EDTA conference of 1971 and joined the ISN.Footnote 38 But at a conference held in West Berlin, Horst Klinkmann learned that Czechoslovak colleagues ‘did not adhere to the common stipulations of the CMEA [Council for Mutual Economic Assistance] countries with regard to the organisation of organ transplants, but went their own way’, oriented towards ‘the FRG and Austria in particular’.Footnote 39 In kidney replacement therapy, relations with the Czech side only fully ‘normalised’ in the mid-1970s.Footnote 40

This was when the East German Ministry of Health Care concluded new bilateral agreements with their counterparts in the ČSSR and Hungary, which specifically dealt with the exchange of donor organs. Objects of the agreement would later on be addressed in the Intertransplant treaty as well: shared clinical, immunological and surgical standards, and the regular exchange of waiting lists and of clinical and experimental experiences.Footnote 41 Connections including occasional organ exchange also existed with Poland in the person of Tadeusz Orłowski (1917–2008) from the First Medical University Clinic in Warsaw, who in 1975 became head of the Transplantation Institute of the Medical Academy.Footnote 42 Relations with the Soviet Union were less developed, despite official rhetoric to the contrary. In the early 1970s, one informer told his secret police officer that co-operation in kidney transplantation with the Soviet Union was non-existent.Footnote 43 Only the news-breaking kidney flown in from Moscow in 1973 seems to have been a starting point for a good working relationship between the Friedrichshain transplantation centre and the Research Institute of Transplantology and Artificial Organs headed by Valery Ivanovich Shumakov (1931–2008).Footnote 44

After the Intertransplant project had been jumpstarted through interconnected bilateralism in Central Eastern Europe by the middle of the decade, the first steps towards a multilateral solution were taken in 1975. A Standing Committee on Co-operation in Health Care was established within the CMEA. The first plan for the period of 1976 to 1980 defined eleven subjects or ‘complex problems’ of scientific collaboration in medicine. Subject no. 8 was devoted to ‘transplantations of organs and tissues and questions of transplantation immunology’. It was divided into several subfields, including kidney transplantation, organ conservation, artificial organs, and, last but not least, the establishment and consolidation of Intertransplant.Footnote 45 The plan defined responsibilities for each subfield and more circumscribed contributions that institutions had to make according to their expertise. For the GDR, Moritz Mebel co-ordinated kidney transplantation and Horst Klinkmann artificial organs. The Berlin District Institute for Blood Donation and Transfusions was supposed to support the immunological work of their Czech colleagues.Footnote 46

From the start, the national transplantation systems were represented by high-profile institutions and their heads, which ensured both the principle of hierarchy and economic organisation with clear responsibilities. Also, with limited resources for traveling to hard currency countries, this structure made sure that the best-connected people would bring the knowledge they picked up in the West back into the Intertransplant community. A case in point was the histocompatibility workshops Intertransplant members conducted, devised as preparation for the International Histocompatibility Workshops.Footnote 47 For the GDR, the Friedrichshain transplantation centre and Moritz Mebel were Intertransplant liaisons, as were the National Institute of Haematology and Blood Transfusion in Budapest, the Transplantation Institute of the Warsaw Medical Academy, the Centre for Nephrology and Urology of the Medical Academy, Sofia, Shumakov’s Institute in Moscow, and the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine (IKEM) in Prague, for their respective countries.

The IKEM soon assumed an outstanding position among the peer institutions. Within the CMEA Standing Committee on Co-operation in Health Care, political decisions were taken in Moscow, and the official language of complex problem no. 8 was Russian,Footnote 48 but executive responsibilities were concentrated in Prague. The IKEM was a non-university institution founded in 1971 which reported directly to the ministry of health. Its Research Department for Organ Transplantation ran the major transplantation centre and the tissue typing reference laboratory in the ČSSR. From 1976, the IKEM computing centre operated a joint Intertransplant waiting list, and an IKEM-led working group evaluated the outcomes of transplantation and immunosuppressive therapy.Footnote 49 In 1978, the IKEM group also co-ordinated the process of devising a more permanent structure for Intertransplant and drafted the ‘manual’, a guideline for the procedures of managing a joint waiting list and of exchanging organs, including criteria and standards for all aspects of the transplantation process. The Intertransplant treaty designated the IKEM as the headquarters, and, in 1981, distinguished IKEM transplantation surgeon Vladimír Kočandrle (1933–2017) was elected first president of the Intertransplant council.Footnote 50

The pronounced role of Czech transplantation medicine does not mean that Czech actors simply had their way. In 1979, there were three competing proposals for an Intertransplant structure: one by the Czech delegation; another one by the CMEA, which had incorporated suggestions from the participating countries, and a last-minute one from the Soviet delegation. Moritz Mebel complained about the Soviet head of the secretariat, who ‘did not always demonstrate great expertise and sometimes left much to be desired in terms of form’.Footnote 51 During the decisive meeting in Moscow, the delegations voted for the Czech proposal as a starting point for discussion, but it was difficult to resolve the critical issues.Footnote 52 To begin with, the Czechs and Hungarians wanted the exchange programme to be a formal organisation. Instead, the Soviets ensured that Intertransplant became a legal agreement. A point that concerned the East German Ministry of Health Care was that member countries were not obliged to report all of their donor organs. ‘Optimal recipients’ in a shared waiting list would not be served preferentially, instead, member states could still prioritise less-than-optimal patients on the domestic waiting list.

Data gathering was supposed to serve at least two different purposes, drawing on both the annual EDTA statistical reportsFootnote 53 and the Eurotransplant waiting list. First, a cumulative patient database would allow a comparison of ‘the results and the quality of dialysis treatment in the Intertransplant member states’, and East German nephrologists expected to compare favourably.Footnote 54 The same competitive perspective would be applied to transplantation performance. East German physicians and health bureaucrats frequently referred to Intertransplant statistics as provided by the IKEM just like they referred to EDTA statistics, to negotiate what was necessary, desirable, and possible for ESRD treatment in their country. Second, the shared data would also form an Intertransplant waiting list for kidney transplantation. A computerised selection mechanism was to ensure the most beneficial and effective matches between donor organs and recipients. Drawing on experiences with the EDTA statistics and for lack of domestic computing resources, East German physicians opted for a liberal exchange of (encoded) patient data in order to gain knowledge about the performance of East German kidney replacement therapy – the Czech colleagues at the IKEM had an efficient computer at their disposal. It was out of the question, though, that ‘persons whose data require special protection’ would appear in this database: patients treated at the Government Hospital. Sensitive health information on high-ranking party members and state officials was not to be disclosed to the socialist brother countries.Footnote 55

After the Intertransplant treaty had been signed, hopes were that ‘in the nearest future a broader collaboration between’ transplantation programmes throughout the world would materialise.Footnote 56 However, although Intertransplant was one of the rare instances where the Standing Committee enabled practical – not only scientific – exchange, complex problem no. 8 did not meet expectations. Transplantation and organ exchange characteristically relied on decentralised and flexible decision-making by heterogenous actors on local and national levels. Intertransplant was thwarted by rigid hierarchies and centralism, reporting duties, planning bureaucratism, and relative isolation from international developments, as former GDR health official Konstantin Rimkeit put it. The most productive part remained bilateral research co-operation between individual institutions.Footnote 57

Kidney exchange activity in the GDR

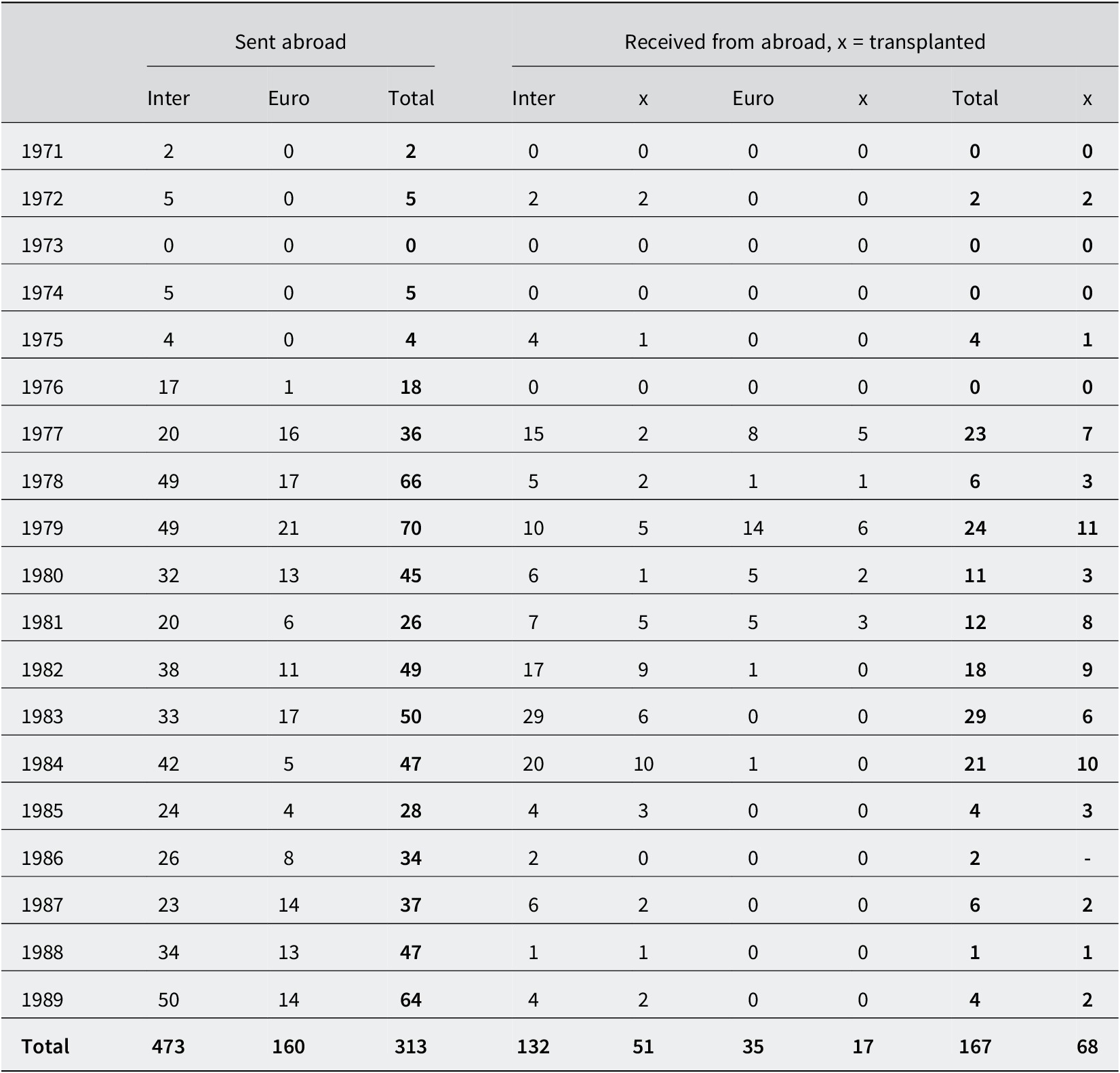

Given the European paradigm of HLA matches and the GDR’s all-in-all successful establishment of a domestic transplantation system, the question arises: what significance did transnational organ exchange have, in quantitative as well as qualitative terms? Statistics provided by the Ministry of Health Care may help here. Though we cannot be sure that the figures are entirely correct, they probably convey a fair impression of the quantitative dimensions.

Significant and continuous exchange both within the Intertransplant group and with Eurotransplant started in 1976/7.Footnote 58 Exchange activity peaked in 1979, with seventy grafts going out and twenty-four coming in. Most kidneys were shipped to socialist countries, also in 1978/9 (and 1989), even before the Intertransplant treaty was negotiated and came into effect. Most kidneys were received from socialist countries between 1982 and 1984; after that, the numbers dropped to an insignificant level. This possibly reflects the market launch of cyclosporine A in 1983. With the specific suppression of the rejection response, matching became less crucial, and kidneys were generally transplanted more often in the donor region, as now a higher degree of HLA incompatibility could be tolerated. Thus, fewer organs were reported to the international exchange organisations.Footnote 59 Exchange was still indispensable for the group of highly immunised patients who showed incompatibility with the bulk of the standardised typing panel and would run a huge risk of severe rejection.Footnote 60 If we look at the number of kidneys transplanted within Intertransplant in the 1980s, the GDR provided 104 kidneys to Czechoslovakia, seventy-eight to Hungary, twenty to Poland, and thirteen to the Soviet Union. The other way around, seventeen grafts from Czechoslovakia were transplanted in the GDR, eight from Hungary, six from the USSR, and three from Eurotransplant (none from others).Footnote 61

A more significant exchange with Eurotransplant from 1977 coincided with selected staff members of the Friedrichshain transplantation centre attending the annual Eurotransplant conferences and training workshops, as did scientists of the District Institute for Blood Donation and Transfusions and the Charité transplantation centre in the 1980s.Footnote 62 Organ exchange with Eurotransplant continued until the autumn of 1989, albeit with considerable fluctuation. We have only scattered knowledge from some of the Eurotransplant Annual Reports about the destinations and origins of kidneys. According to the 1979 report, for instance, two kidneys from the GDR were transplanted in Italy and one in Turkey, while East German patients received two kidneys from West Germany, three from Dutch donors, and another kidney came from the Scandiatransplant network.Footnote 63

From a different official source, we know that between 1967, when the transplantation programme started, and the end of 1988, 2,216 kidneys from cadaveric donors were transplanted in the GDR altogether.Footnote 64 According to Table 1, only sixty-six – or three per cent – out of these 2,216 transplanted kidneys came from organised transnational exchange. As much as the sixty-six kidneys were beneficial to individual patients in the GDR, their sheer number seems not to have been essential for the functioning of the East German transplantation system. Moreover, only some of the kidneys reported or even of those received from abroad could actually be transplanted. Of the 35 kidneys received from Eurotransplant, only a little more than fifty per cent could be used for transplantation. The ratio was even worse for kidneys received from Intertransplant: only forty-nine out of 128 kidneys were transplanted to East German citizens. But the same was true the other way around. As far as the incomplete data allow us to conclude, from seventy-seven East German donors, or 144 potential kidneys, reported to Eurotransplant, only fifty-one transplantations resulted.Footnote 65 Transplantation practice on both sides of the Iron Curtain meant that transnationally reported organs often were of minor quality (for various reasons) or had been taken from donors with rare blood group and tissue profiles, while ‘good’ grafts with ‘easy’ matches would be used on the spot.Footnote 66

Table 1. Kidneys sent abroad/received from abroad and transplanted from 1971 to 1988

Note: Inter = Intertransplant; Euro = Eurotransplant

Source: In das Ausland verschickte/aus dem Ausland erhaltene u. transplantierte Nieren von 1971–31.12.1988, BArch DQ 1/14219. Figures for 1989 from Mebel, May and Althaus, op. cit. (note 3), 77, table 6. Other sources suggest slightly different numbers. Cf. Eurotransplant Foundation, Eurotransplant Annual Report 1978, table VIb; Aantal niertransplantaties centrum GEBPT (voorheen East Berlin) (received from the Eurotransplant public relations office via email on 17 June 2022).

We can also learn from Table 1 that the GDR was a net supplier of kidneys in trans-border exchange, shipping almost 633 kidneys to both Intertransplant and Eurotransplant while receiving only 167. Disadvantageous imbalances of this kind were no exception. Structural disproportions of giving and taking in kidney exchange were a constant irritation within the Eurotransplant community, for instance.Footnote 67 They evolved because the treatment, despite its transnational quality, was informed by national differences in organising health care. These concerns included funding, reimbursement, and care infrastructure, but also bioethical debates and legislation.

The GDR had introduced legal regulation of organ transplantation in 1975, comparatively early in international comparison. Tailored towards the needs of transplantation medicine, it confirmed the practiced principle of presumed consent: deceased or brain-dead persons automatically became organ donors unless it was known that they had objected during their lifetime. From the start, East German ESRD specialists had thought it perfectly legitimate to use organs of a deceased person to save someone else’s life. The regulation of 1975 mirrored their ethical priorities, as it was rather laconic on cadaveric donors but rather detailed with regard to physical risks and emotional stress for living donors. It also obliged physicians to obtain and document graft recipients’ informed consent.Footnote 68

Though socialist countries tended to dispose rather liberally of the dead bodies and body parts of their citizens,Footnote 69 political systems did not correspond neatly with presumed versus informed consent approaches. Throughout the West, legal regulations and practices of cadaveric organ donation remained diverse and fluid. From the late 1970s, several West European countries enacted opt-out legislation (e.g. Spain in 1979, Austria in 1982, and Belgium in 1986).Footnote 70 Significant differences, however, can be discerned regarding the measures taken to ensure informed decision-making. The GDR practised what is nowadays called a ‘hard opt-out’: relatives of cadaveric donors were neither asked for consent nor informed. Furthermore, a deliberate lack of transparency characterised its organ donation legislation. The Ministry of State Security had advised that the 1975 regulation be kept secret, as the opt-out paragraph could raise critical responses within the GDR and abroad, including the expression of ‘religious and also ethical-moral views’.Footnote 71 While it was published in the Law Gazette, nonetheless, there was no information campaign that would have made citizens aware of it, let alone a public debate. Nor did the health administration create an official mechanism to register objection to being an organ donor.Footnote 72

However, resolute pro-organ-harvesting legislation alone did not guarantee a satisfactory degree of implanting activity, as other variables left much to be desired. Especially in the 1980s, shortages, friction, and delays frequently disrupted the East German system of kidney transplantation. Insufficient conservation technology put the selection and preparation of patients on a tight time schedule. As dialysis treatment capacities and equipment were never sufficient, the patients’ state of health deteriorated, so they could not undergo transplantation. The paperwork necessary for keeping patient information up to date was overwhelming when personnel were already overburdened by clinical routines. Dialysis centres did not communicate properly with the co-ordinating office at the Friedrichshain transplantation centre, so patients flagged ‘ready for transplantation’ in the database often turned out not to be when a suitable organ became available. Also, immunological typing was delayed, and often, local brain death commissions could not be summoned in time. As a consequence, many organs had to be reported to the exchange organisations.Footnote 73

Kidneys travelling thousands of miles to save lives remained solitary events that made the news but did not reflect clinical routines. In quantitative terms, over a stretch of almost twenty years, the GDR transplantation centres did not tangibly profit from international organ exchange. But does that mean this engagement was inefficient or even a failure? Archival sources indicate that medical professionals, as well as health bureaucrats, seemed to think the commitment was worth it. Then how did the GDR benefit from non-commercial organ exports if not by getting a fair quantity of organs in exchange?

A network of exchange networks

Organ transplantation systems have been described as ‘networks heterogeneously recombining other networks’, such as energy, traffic, and telecommunication infrastructure.Footnote 74 In fact, traffic flow and information management processes were critical preconditions of transplantation becoming a routine. But this observation can throw some light if applied on a different plane as well. Maybe participating in networks of organ exchange, even if not per se advantageous for the GDR, helped to successfully pursue other goals: proving capability, staying connected, being included, gaining recognition as a state, and having a foot in the door of international biomedical progress. Organ exchange networks were intertwined and intersected with other networks relevant to kidney replacement therapy. Besides organs and typing sera, knowledge, data, technical devices, and drugs circulated in this wider network of interconnected exchange relations, where giving and receiving did not necessarily come in the same currency. A negative balance in the shipping of organs could be economic when it indirectly helped to secure a positive balance in the flows of data, knowledge, or drugs.

Such an indirect exchange rationale had emerged already in the 1960s. At first, when GDR physicians still hoped to excel in kidney replacement treatment and sell homemade dialysis machines to the world, the lack of international recognition was in the foreground. Presenting at EDTA conferences, getting hold of offices, hosting an annual meeting, and the East German Association of Nephrology becoming a member of the ISN were seen as steps towards acceptance into the WHO, and more generally towards being a respected member of the international community, in terms of diplomatic relations with Western countries.Footnote 75 International contact resulting from EDTA activity also helped to improve the emerging domestic system of ESRD therapy: Annual EDTA conferences and council meetings at alternating venues allowed GDR representatives to visit leading dialysis and transplantation centres and to arrange internships for their junior and senior physicians and their laboratory staff.Footnote 76 Here, they could acquire hands-on knowledge of a variety of general and specific problems, e.g. tissue typing, performing kidney biopsies, how to use the respective new generation of artificial kidneys, how to manage preoperative blood transfusions and postoperative care, and how to run a transplantation centre. International contact directly improved the level of treatment through the transfer of knowledge,Footnote 77 at least in the privileged top institutions.

In the 1970s, when the treatment system expanded but hopes to be among the top performers or at least to become self-reliant with regard to technology dwindled, the focus of exchange shifted towards a more material one. As dialysis technology, consumables, and immunosuppressant drugs had to be imported, commissioned testing of dialysis devices and membranes became a systemically relevant factor, as it saved hard currency and provided access to the latest technology.Footnote 78 Horst Klinkmann’s excellent connections to the US and other parts of the world helped to establish the Rostock Medical University Clinic as the leading dialysis centre in the GDR, in his perception, actually the leading institution in the socialist bloc and the ‘acknowledged test clinic for all socialist countries.’Footnote 79 What helped in this respect was that the East German Society of Nephrology, approved by the EDTA leadership, had assumed a co-ordinating function with regard to Eastern bloc members’ EDTA activities early on. Practically, this included getting people elected to office and securing conference venues in socialist countries. Klinkmann strategically rallied support among socialist as well as non-socialist colleagues to hold offices in international associations: in 1979–84, he served as president of the International Society for Artificial Organs, in 1975–8 and 1984–8 he was a member of the EDTA council, and in 1988 was elected its first and only president from a socialist country.Footnote 80

Despite this very successful networking, from the mid-1970s, it became evident that the GDR would fall short of its self-proclaimed goals in kidney replacement therapy. There was a growing gap between the real achievements of an expanding transplantation system, international developments in the field, and the promises made to the population. The situation worsened in the 1980s, when a structural debt crisis put East German health care under enormous pressure. As the acquisition of hard currency through ‘immaterial export’ became an explicit task for university clinics, the testing of drugs for Western pharmaceutical companies intensified.Footnote 81 This was especially the case for cyclosporine A, a drug manufactured by the Swiss Sandoz company, which dramatically increased graft and patient survival rates. Authorized in 1983; it soon became standard medication in countries with hard currencies. This made East German physicians and health officials worry, not only because it would make the GDR look bad abroad. The social contract of free, accessible and up-to-date health care was at stake, as East German patients and dialysis physicians learned about the new drug via mass media and West German relatives. A ‘massive ideological and moral pressure’ arose: ‘It is politically unacceptable that private individuals and institutions, including the church, conduct collections for Cyclosporine for our patients in Western countries or that kidney transplant patients illegally leave the GDR for the sake of Cyclosporine therapy’.Footnote 82

With no financial means available for buying drugs on the market, a veritable campaign of clinical testing in the field of graft rejection therapy and prevention was launched. This also happened against the backdrop of other socialist countries like Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia successfully seeking co-operation with Western companies.Footnote 83 The East German testing of graft protection medication was centralised at the Urological Clinic of the Charité University Hospital, in the hands of Moritz Mebel’s long-time co-worker Dietmar Scholz (b. 1942). Since the mid-1970s, he had been involved in the Charité administration, where he was in charge of negotiating clinical tests with Western pharmaceutical companies.Footnote 84 In 1983, he was appointed consultant of the Ministry of Health Care for drug provision in the context of transplantation, which meant that every single dose given to GDR patients had to be approved and assigned by him. Scholz also toured cyclosporine symposia and other conferences around the globe, often paid for by drug manufacturers, to present results, negotiate further support, and acquire new contracts or participation in multicentric studies.Footnote 85 In this vein, Eurotransplant workshops became platforms for meeting representatives of pharmaceutical companies so that the most urgently needed medications would be provided for free.Footnote 86 From early 1984 until the end of 1985 alone, cyclosporine A, anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), monoclonal antibodies, and medication countering cytomegalovirus infection, worth half a million Deutsche Marks (the West German currency), were imported via clinical testing.Footnote 87

Conclusions

If one would expect that reciprocal organ exchange was a prerequisite for a successful national transplantation system, the East German case can teach an interesting lesson. The GDR transplantation system was able to procure enough kidneys to keep the system running but failed to achieve the number of transplantations determined by the plan, which would have met the estimated needs of patients. However, to overcome the shortage, the priority was not importing but increasing the frequency and quality of domestic harvesting.Footnote 88 Organs crossing the national borders were anything but instrumental for the system to work, though the insufficient number of organs increased inequalities between Berlin and the rest of the country, between normal citizens and privileged ones.Footnote 89 Still, it made sense for the GDR to participate in organ exchange and even ship many organs abroad, as they were only one element in a wider network of exchange relations. What the GDR had to gain from networking and exchange in general was recognition: that it had a decent level of health care, that it could compete in specialised treatment, and moreover that it was capable of international co-operation and that it was a reliable partner. This reputation paid off most prominently when, in the 1980s, urgently needed medication could only be accessed through commissioned clinical testing. This was at a time when testing on humans had become more difficult in Western countries due to legal restrictions, reluctance on the part of patients, and general suspicion towards big pharma. GDR physicians and health officials were aware that they had something to offer to Western companies: a centralised, well-organised testing environment with clear-cut responsibilities, compliance with international standards of clinical testing, and no agitation to be expected from patients, relatives, or the critical public.Footnote 90

Apart from these material benefits, being part of a data exchange community was equally important. In a country where sensitive statistical information like the rates of suicide, crime, and alcoholism were kept secret, it was desirable to have access to reliable data (and computing resources) via transnational networking. And vice versa: the EDTA Registry acknowledged that, due to the uniquely centralised data gathering process in the GDR, the East German questionnaire response rate was always a hundred per cent, and the data arrived in a handy single package.Footnote 91 Figures from EDTA annual reports or similar international statistics circulated in the East German health care system, as they allowed performance and achievements to be evaluated ‘objectively’. Medical professionals frequently used them to underline their demands to the health administration. From the mid-1970s, they pointed out how the GDR, after a successful start in ESRD treatment, had managed to assert a leading position among the socialist countries (until it was ‘overtaken’ by Yugoslavia in the early 1980s) but fell behind in international rankings year after year. Though the absolute number of treatments continuously grew, the system stagnated and left East German physicians struggling to catch up with the Western average, at best.Footnote 92

Despite many achievements realised self-reliantly or in joint socialist efforts, the GDR never escaped dependency on Western imports, be they material or immaterial. That does not mean the key point of this story is Western dominance – or Soviet dominance, either. Intertransplant provides an example of how Central Eastern European initiatives, invigorated by international connections, counterbalanced Soviet hegemony. At Intertransplant council and expert meetings, everybody would switch to English as soon as the official parts, conducted in Russian, had been finished. Even Moritz Mebel conceded that the obligation to communicate in Russian made co-operation more difficult.Footnote 93 Though Mebel was a most loyal friend of the Soviet Union, his transplantation centre mostly worked with institutions in the neighbouring countries, Czechoslovakia and Poland. Geographical proximity and a long-standing shared academic tradition in Central Eastern Europe appear to have been more effective than the ideological agenda of Soviet leadership. The main actors at Intertransplant were Czechoslovakia, the GDR, and Hungary, while the Soviet colleagues and health administration kept to themselves. This is mirrored in Soviet kidney exchange activity, or lack of it. From 2,057 transplanted kidneys harvested in the USSR in the 1980s, only ten went abroad.Footnote 94

To conclude, what did ‘therapies crossing borders’ mean in the case of East German kidney transplantation? From the perspective of organisational sociology, it has been argued that Eurotransplant lost its organ-supplying function soon after the arrival of cyclosporine. Monitoring, quality control, creating public trust, and overcoming the tenacious reluctance to donate organs moved to the fore, while organs kept being exchanged.Footnote 95 Though critical discussion of organ donation was never the point in the GDR, a parallel can be seen in that organ exchange ceased to be (or maybe never was) primarily about organs. In the 1980s, it was, instead, about being part of an international professional and scientific community. Organ exchange, even on a very low level, rounded off a complex and shifting set of foreign relations in a particular field of medicine that helped stabilise the GDR healthcare system while also leaving it vulnerable at the same time. In kidney transplantation, as in politics more generally, the dynamics of opening up to the world and asserting independence were ridden with ambivalence and dialectical effects that were difficult to control.Footnote 96

Acknowledgements

The writing of this article, which is part of the project ‘Taming the European Leviathan: The Legacy of Post-War Medicine and the Common Good’, was supported by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 854503). Valuable suggestions and feedback from the anonymous reviewers helped to improve the manuscript.

Competing interests

The author declares none.