Introduction

This article uses role theory to bridge the gap between Confucian and Western conceptions of International Relations (IR). With the support of role theory, my comparative analysis of IR universe mainly focuses on two different types of relations: prior rule-based relations and improvised relations. Different cultural preparations for these two relations partially explain plurality in the IR universe. In my comparison, both Confucian IR and Western IR have prior as well as improvised relations, similarly aimed at dealing with estrangement between actors. I argue that role making and role taking according to these types of relations can reveal how the two seemingly irreconcilable IR universes interact and coexist.Footnote 1

Western IR and Confucian IR represent two styles of prior relations – the state of nature and Tianxia – and two styles of improvised relations – an interactive process that socialises alters into like members and that establishes the parameters of mutual acceptance regardless of the differences between actors. In the state of nature, a shared resemblance, in terms of the rights and laws of nature, constitutes all actors. In so doing, the resemblance denotes the prior relation, which obliges all to incorporate it into their self-identities and, hence, connects them. In contrast to relating by consensual rights and laws of nature, the Confucian relational theory of Tianxia (literally ‘all-under-heaven’), which argues that all living things are bound to be related without deriving a consensus on who/what they are, obliges all to improvise in order to fulfill the mandate of being related. This is where role theory contributes to the study of Confucian relations. I mention gift giving and ritual/name-bestowing as two ways to explore and reproduce mutually agreeable roles in the Confucian relation.

I will first discuss the Confucian ‘state of nature’ and its sensibilities to strangers, compare it with the social contract tradition, and introduce the Confucian style of relations and roles. To illustrate the value of a composite agenda of relations and roles, I will use Kim Jong-un of North Korea (hereafter NK) as an example. I will describe the processes of Kim's role making/taking with three other heads of state – Moon Jae-in in South Korea (hereafter SK), Donald Trump in the United States, and Xi Jinping in China – through the lens of Confucian IR. Such an exercise illustrates how a presumably weak power can rely on both shared prior relations and improvisation in role making to oblige reciprocal responses from strong powers. In the process, a prior familiarity with Confucianism is unnecessary for a mutually estranging alter such as Washington to enter the role relationship improvised for it.

The Confucian state of nature

Consider the evasiveness of Confucian relationality. While the heavenly reason constitutes all, it belongs to an unlimited variety of people and objects. However, from the point of view of each of these ten thousand phenomena, they are easily mutually misperceived as strangers because of the absence of a transcendent divinity to remind them of their prior resemblance,Footnote 2 embedded in a common, albeit undecidable, form of existence. Misperceived strangeness would curtail their natural relation, so ways of interacting must be improvised to neutralise the mutually perceived strangeness caused by the unlimited, albeit superficial and transient, variety.Footnote 3 On the one hand, variety is a heavenly phenomenon and, therefore, natural. On the other hand, it makes no sense to attempt to draft universal rules or norms in the light of the apparent variety qua strangeness. Investigating strangeness against a standard out of curiosity or converting an alter life accordingly is highly discouraged,Footnote 4 leading to a policy preference for relationship management rather than governance.Footnote 5 The capacity for gift giving looms essential to the production and reproduction of an existing relational arrangement in every bilateral interaction. Gift giving is, arguably, the most common self-/socialising mechanism in Confucianism's dyadic style of relationality.Footnote 6

Confucianism preaches the wisdom of ‘keeping the aliens governable by not governing them’. This evasion of ontological settlement suggests that, for Confucius, aliens are not equivalent to strangers. In fact, he praised the true gentlemen as those who presumably bring with them gifts and lofty postures that are appreciated by aliens and whom aliens have no difficulty in accepting; however, unfaithful princes can become estranged, even in their own neighbourhood, because they levy rather than give.Footnote 7 In other words, distance does not define strangeness, which is internally untamed.Footnote 8 Strangeness is thus politically incorrect but revealing wherever self-roles are rejected by the audience. It is the heavenly mandate – a kind of natural contract between each prince and heaven – that obliges princes to win acceptance by the existing member of the population through their benevolence, which further enables those who accept them to accept one another. Mutual acceptance is called face culture. Face, the vernacular side of role, pertains to camouflaging, taming, and disciplining the stranger inside everyone.

The derived notion of a stranger from Confucianism echoes the recent call for a critical reflection on the literature of the stranger.Footnote 9 The critical approach discovers ‘ahistorical, Orientalist, racialized, colonialist, and historicist fault lines’ in the literature. It justifies a parallel call for a relational analysis of the stranger and foregrounds the revisiting of Confucianism.Footnote 10 The Confucian stranger is simultaneously an internal object, shameful, unrelated, as well as threatening, and an external object to appease, so she is neither an Orientalised outsider nor an autonomous entity. She appears only where mutually congruent expectations fail to emerge for she loses a role relationship. Such a stranger conception contrasts with the other kind of stranger in the social contract tradition. In the latter version, the stranger, constituted by her prior right of nature, can and should be socialised into a prudent citizen.Footnote 11 Whereas Confucianism regards the strangers as misperceived self-identities caused by their inherent diversity, which can and should be avoided by all acquiescing to mutual benevolence, prudent citizens are entitled to individualised preference and opinion that inform their identities each distinctively.

Relational strangers, who are related through their likeness according to the European traditions of the state of nature, would suffer under the dreadful anarchy if not because of the security provided by the social contract. The difference between the Confucian and Western cosmologies in the formulation of the state of nature alludes to the subsequent bifurcation of the relation conception. Let us take Thomas Hobbes as an example, since his narrative on anarchy inspired modern IR. Hobbes ‘ascribes to each person in the state of nature a liberty right to preserve herself’, which he terms ‘the right of nature’.Footnote 12 Humans will recognise as imperative the injunction to seek peace, and do whatever necessary to secure it, when this can be done safely. Hobbes calls these practical imperatives the ‘Lawes of Nature’,Footnote 13 a rule-prone relation that binds all to the absolutist Leviathan, who may compromise this right in exchange for providing security.

Social contract theorists in general embrace ‘natural rights’, with or without Hobbes’ Leviathan, as the prior relation that constitutes all, individual as well as national, actors. Alexander Wendt, for example, shows how anarchy is about collective qua social figuration. English School scholars, especially ‘solidarists’, would tend to agree.Footnote 14 Such prior relations, informed as they are by the law of nature, postulate a humanist ontological semblance a priori. Even so, a noticeable component of the Hobbesian state of nature speaks to ‘the primitive units’, such as families, that are ordered by ‘internal obligations’ – affection, sexual affinity, friendship, clan membership, and shared religious belief.Footnote 15 This latter line of thinking echoes the core of Confucianism – kindred love. That said, in general, the natural law in the West transcends the primitive relation to privilege autonomy, rationality, and equality, where all are entitled to identities and desires as a natural right. Such shared entitlement offers a guarantee of security, which breeds social tolerance, solidarity, and communitarianism.Footnote 16

Confucianism, likewise, adopts an implicit stance on the state of nature. In fact, Confucius stated clearly that the ethical order was built upon humans’ natural love for their kin. He proceeded to use the family – the Hobbesian primitive unites – as a metaphor to guide rulers so that all living beings can be metaphoric brothers under the reign of the Son of Heaven. Confucius inspired later generations in their quest for kingly leadership, embedded in the virtue of benevolence towards kin. Regardless of its different interpretations, benevolence is pragmatically about the prince prioritising either moral exemplification or the provision of affluence.Footnote 17 A couple of complementary concepts, Yi (oneness, that connotes being accepted anywhere) and Dao (the Way, that connotes accepting anyone),Footnote 18 that ontologically constitute both humans and nature, could be in line with either the moral or affluent styles of benevolence.Footnote 19

Such a familial/patriarchal metaphor is spontaneously hierarchical, ritual, and moral. The metaphor is composed of familial roles, not directly human actors. Familial roles define proper benevolence; benevolence indicates love; love camouflages strangeness otherwise. Note, however, that metaphorical love is ritual, not affective. Benevolence is practically either gift giving to promise affluence or sacrifice in the ritual to exemplify a common origin. Benevolence as role playing inevitably produces contradictive relations. On the one hand, roles replace identities, which incorrectly connote strangeness, so individual differences are silenced. The benevolence as role playing of any (universal) rule at a particular moment in a particular context to win acceptance by the existing members of the anarchical relations is, ironically, implied here. On the other hand, benevolence camouflages who we are, thereby shielding individual differences. The non-interventionism sensibilities are registered here to tolerate the evasion of rule.Footnote 20 In short, for those subscribing to the rule-based governance, Confucianism's predisposition to avert strangeness can be a mixed blessing.

Confucianism advocates nominal roles to oblige the elite to engage in benevolence and self-restraint. Confucianism relies on the seasonal rituals of heavenly and ancestor worship to socialise all into their familial obligations to demonstrate benevolence towards each other. Confucianism pursues no monotheistic/Abrahamic transcendence.Footnote 21 Rather, familial roles merge nature with the human. The mysterious and yet commonsensical notion that Heaven and Humans constitute each other (tian ren he yi) continues to be widely quoted today,Footnote 22 testifying to this desired symbiosis between nature and society. Confucianism's reliance on kin roles determines that every individual, if left unassociated, is reduced to a politically incorrect stranger. Confucian governance prioritises education in the hope that all of the elite will play suitable roles. Roles tame their temper and desire so that commoners can learn from their faithful giving of benevolence and feel secure and willingly dependent.

Confucian education, aimed at gentlemen's malleability to mingle with but not be inquisitive about nature, the family, the regime, the population, and encountered aliens, contrasts with the humanist tradition that is embedded in truth, aesthetics, and ethics within Western education. Preferably, for Western IR, consensual rules and norms will cast newcomers into liberal roles and establish an ontological likeness to enable the appreciation of each other's being special. The presence of strangers thus obliges two different missions. The Western mission is to respect the same humanity that strangers are believed likewise to possess or to socialise them if they practice no such humanity; the Confucian mission is to enhance strangers’ benefits and acquiesce to their concealed strangeness once they agree to accept the counter roles that honour the self-roles. The problem of role failure, for Western relations, lies in alters’ insufficient solidarity, but, for Confucian relations, in the self's insufficient benevolence. Their respective prescriptions are intervention and gift giving, alongside ritual learning.

Given the aversion to hidden strangeness in the Confucian self, naturalness can ironically be preserved as long as the self succeeds in socialisation, that is, selflessness. To that extent, the right of nature that recognises autonomous selves can, contrarily, be threatening. Hence, a plausible relational proposition under Confucianism is: the need to have a role is stronger than which specific role to have. Confucianism's relational base for role theory necessarily leaves both value and institutional guidance blank for the self and the alter to improvise according to their bilateral trafficking. As such, the relational inevitability of all being kindred and friends does not determine which kindred or friendly roles to enlist or how. All are obliged to do so, presumably through proper, at times competitive, gift giving. Kindred and friendly relationships necessarily evolve through inconsistent, cyclical, and contradictive role making. Thus, the Confucian relationality breeds anxiety towards the revelation of the self, conceived of as incorrect stranger, and an absolute necessity for self-disciplining.

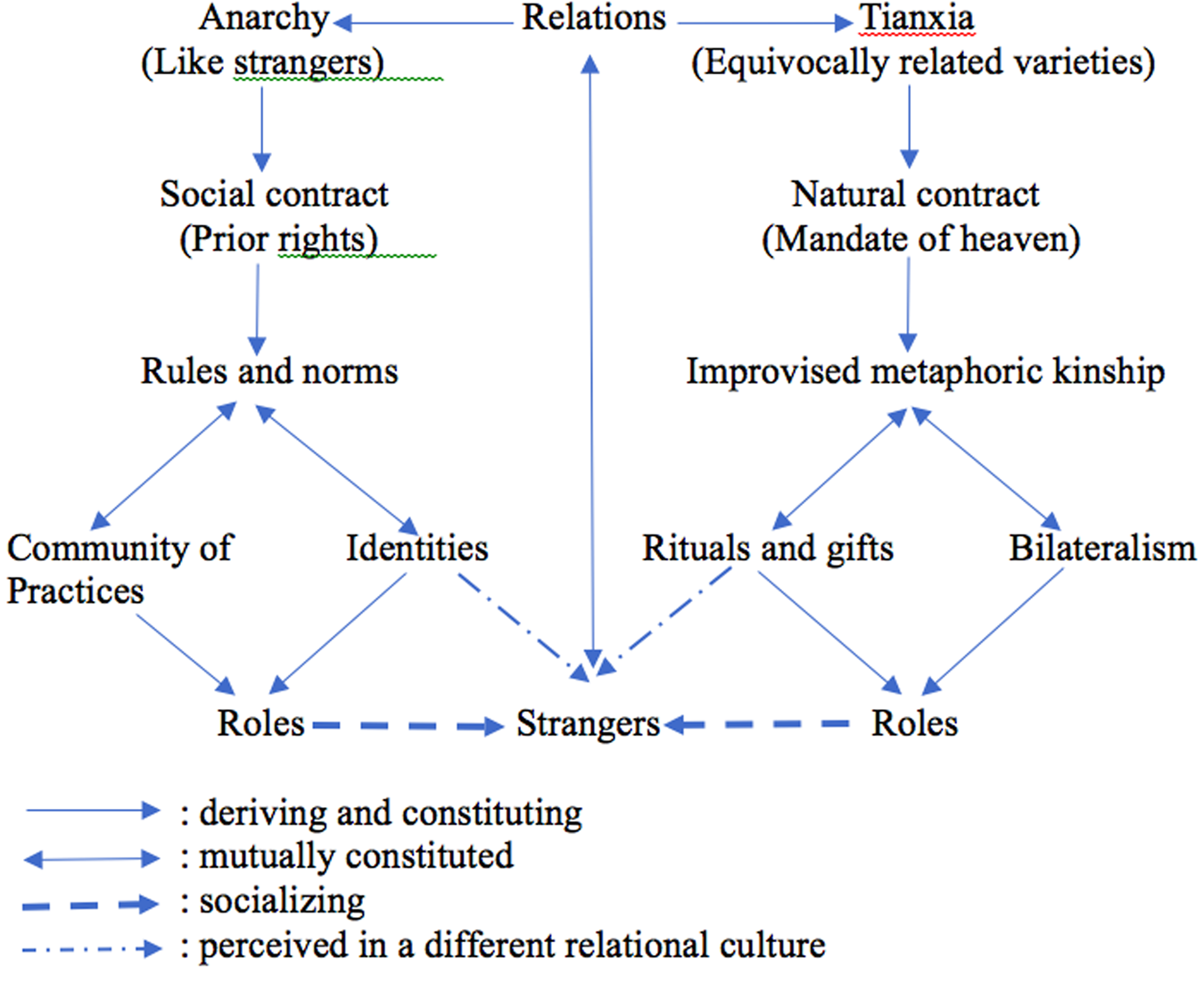

In sum, role making to connect actors with no apparent prior resemblance shows how mis/perceived strangers cope with each other's otherness and strategise relationally.Footnote 23 Both imposing and facing the socialising pressure are intrinsically concerned with an interrogation of how the self is mainly about role playing. Confucianism is conscious about this and mindful of how a stranger-alter exposes a stranger-self. The processes whereby a strategic agent casts a target stranger into accepting the former's self-role conception, as in Confucianism, contrasts those socialising the stranger to accept and perform rules and norms, as in the social contract traditions.Footnote 24 The two kinds of prior relations constitute and yet divide states beforehand and roles practice relations and/or socialise each other thereafter (Figure 1).Footnote 25

Figure 1. Relations and roles of the two states of nature.

Defining relation and role for Confucianism

Contemporary Confucian IR interrogates the place of Western IR in Tianxia.Footnote 26 Confucian relations are intellectually accessible to the Western nations through Confucian role theory because it is directly comparable with Western role theory's symbolic interactionism tradition. Confucianism enlists the natural love of kinship and relies on its metaphorical extension to maintain Tianxia's relationality that symbolically encompasses all.Footnote 27 Such a formulation produces a sense of apprehension towards strangers and strangeness. As no stranger is cosmologically possible in a social environment, presumably strangers can only be internal to each self. Confucian role theory proceeds to tame internal strangeness. Reversing the typical processes in the Western role theory of socialising role takers each to their respective positions,Footnote 28 gift giving in Confucianism abides by the alters’ benefits instead and attends to winning acceptance of the self-roles by as many alters as possible.Footnote 29

Given that strangeness and resemblance are antonyms, I will use ‘relations’ to indicate how actors imagine their symbolic resemblance to one another (in terms of genesis, kinship, nationality, race, residence, religion, culture, ideology, alliance, interest, alma mater, work, and so on) and therefore should, through self-restraint, act in solidarity to a minimal degree,Footnote 30 and ‘roles’ to incur specific expectations that one must fulfill.Footnote 31 These definitions arise from readings of symbolic interactionism, recognise their diversity, and revise them in order to allow the ready contribution of Confucianism. The significant component in the readings is social construction, as relationalism attends to prior patterns, processes, social interactions, discourses, cultures, practices, and so on, on the one hand, that constitute identities of interacting actors,Footnote 32 and a foreign policy role points to a salient position in social situations as well as socially recognised categories of actors on the other hand.Footnote 33 In comparison, the abovementioned definitions further derived in this article are succinct and yet broad. The purpose is to consider those aspects of relations and roles that are not socially or practically prior either between strangers or actors estranged from past association. This de-emphasis on the construction of prior social consensus is epistemologically intrinsic to Confucianism.

Symbolic interactionism,Footnote 34 according to which social relations shape role making, informs roles. Interactions between the actors only acquire meaning if placed against the prior construction of the shared resemblance that sensitises them.Footnote 35 Accordingly, roles are embedded in generally consensual rules that explain social control. The theory recognises that the ‘multiplicity’ of social environments, which necessitates individuals mediating between the rules, preserves the agency for role making.Footnote 36 The prior construction for international politics occurs in three kinds of role locations – prior rules and norms applied to all interacting parties, prior conventions viable only for the interacting couple, and prior history of national self-role conception shared by a domestic audience. As already discussed, however, the Confucian role theory is preoccupied with the self as well as the bilateral, as opposed to the universal/multilateral kinds of location. Given the domestic as well as multilateral sensibilities of symbolic-interactionism-informed role theory, the overlap with Confucian role theory is apparent on the third agenda of constructing the national self-role conception.

Furthermore, the attention of symbolic interactionism to the prior construction is also insufficient, as it attends primarily to how to socialise the alter according to the perceived prior consensus.Footnote 37 For example, this was the essence of Westernisation when Russia joined Europe or when China left the Sinic order.Footnote 38 Confucian relations focus instead on how the self can prove to the alter that the self can be socialised. This leads to attempts mainly to pre-empt the perception and wording, as opposed to behaviour, of the alter. In addition to the interpretation of the self, concerning the self's role,Footnote 39 that is important to symbolic interactionism, the interpretation adopted by the alter is equally, if not even more, a stressful target of the Confucian self's role enactment, leading to self-socialising to satisfy the perceived expectations of the alters.

Concerning the socialisability of the self, the two most relevant kinds of Confucian locations – the national and bilateral selves – constitute a procedural continuum, with those acting on behalf of the national self to select a role judged to be both acceptable to the alter and legitimate to their own audience and, then, to provide gifts that are deemed proper for the presentation of the selected role to convey the socialisability of the bilateral self to the alter. For the Confucian self-role, legitimacy and gift are the two major points to consider.

Legitimacy, the former concern that is contested domestically, reflects the self's interpretation of a prior (metaphorically extended familial) relation that is perceived to be shared among the domestic audience of the national self as well as the members of the international community, to which the national self, bilateral self, and alter commonly belong.Footnote 40 Gifts, the latter concern, are improvisations to lure the alter, introduce the national self-role, and cast the alter in a counter-bilateral role. Gift giving is a peculiar style of symbolic interactionism. An improvised gift is nonetheless embedded in social meaning, although often not intended to reproduce the prior social (that is, multilateral) norms. Rather, if it is essential to bypass them to achieve a mutually acceptable relationship specifically with the alter, the gift giver will do so. In sum, a gift should make the alter happy, so it can be welfare, honour, or simply help when in need, but never interventionary to the alter or implicating third parties.

The striving for domestic legitimacy nonetheless alludes to the caring for distinctive self-interest only for the nation, implying ulterior and incorrect strangeness, and embarrassed relationality.Footnote 41 The self-interest sensibilities contrast with the cosmology of Tianxia, according to which the self and the alter resemble each other in terms of a shared heavenly mandate to remain related to all. As a result, Confucian relations must engage in self-balancing:

Since the self exists simultaneously with others, their interests are related, shared, and realized through joint effort. It is mistaken to assume that self-interest is of primacy and it is equally mistaken to assume that collective interest comes before everything else. For Confucianism, a balance of the two is the key to a healthy society.Footnote 42

Given the embarrassment to relationality caused by the revelation of politically incorrect, albeit misperceived, strangeness, the contents of the role are less important to the Confucian relationality than the acceptance of a relationship. As a corollary, wherever a mutually agreeable role relation between two strangers emerges successfully, it can evolve into a bilateralised prior relation and dominate one's relations elsewhere, because being accepted by a seeming stranger necessarily indicates a salient role. On the contrary, the repeated role failure or mutual estrangement caused by domestic legitimacy/interest concerns threatens solidarity. Nevertheless, the strength of a prior relation cannot always be known until the roles to fulfil the actors’ expected duty are aborted and there is a call for intervention or sanctions. In the same vein, a gift for a stranger-alter to compensate the alter for non-conformity of the self, purely as a demonstration of goodwill, can be mistaken for a testimony of solidarity, until another perceived nonconformity with the rules disillusions both sides.

In any case, Confucian roles and relations are not identical. The relations that align the members belonging to Tianxia concern resemblance and, thus, epistemologically, are symmetric in terms of their relevance and importance in determining the level of relatedness to their alters. However, mutual roles are often expressed through socially higher and lower statuses in a hierarchy, as elsewhere, for example, colonisers and the colonised, which exemplify the asymmetric norms of interaction. For weak nations to compel a strong counterpart to comply, they must rely on the skill of evoking a co-constituted, that is, symmetric, resemblance. As Tianxia is undecidable and evasive, altercasting the strong party into accepting the self's role conception through gift giving becomes essential to triggering the reciprocal relation. Gift giving usually reflects an asymmetric role relationship, but a resulting order of Tianxia immediately ties the self-integrity of the strong party to the acceptance by the weak party.

In addition, roles are actor-centred but relations are about collective resemblance. Following symbolic interactionism, the multiplicity of the social environment determines that each actor is definitely involved in more than one relation, which makes the aggregate of communities of practice necessarily dissimilar for different people.Footnote 43 Given the evasiveness of Tianxia, however, staying related is almost synonymous to being accepted rather than affirmatively practicing any specific relationality. A role that can ensure a minimal level of acceptance is one that can camouflage the incongruence caused by multiplicity, hence a nominal, abstract, and metaphoric set of role conceptions for as many as possible, whose resemblance stems not from shared commitments to rules or norms, but from the gifts that accompany symbolic togetherness in Tianxia. Being a nominally selfless, practically inconsistent, and politically bribing actor, the prime motivation is to win acceptance. Specifically, gift giving evades the incongruence between the self and the alter and the resulting incorrect estrangement. The gift lures the alter not to stress its distinctive role conception as a way of acquiescing to the otherwise incongruent role conception of the self.

Given the condition of unlimited human diversity, existentially the onus is on the gift giver to repeatedly show herself to be sociable enough despite mis/perceived strangeness. Preoccupied with domesticating estrangement and strangeness, Confucian IR can make an additional contribution to the pluralisation of relational IR in the following three senses. First, when a strong nation seeks acceptance by a weak alter to indicate the socialisability of the former, even a weak nation's relational identity can be privileged. Secondly, when rules and norms fail to prevail, nations can temporarily prioritise acceptance over rule setting because, ‘regardless of the variation in their regional environments, political systems, and political culture’,Footnote 44 all must have roles. Thirdly, enacting rules in a particular context may convey less about successful socialisation to the prior social norms than the strategised expedience of the self to win acceptance by those who strive to socialise the self. The two relationalities intersect in a pragmatically undecidable hub of coexistence, with whichever better controlling mutual estrangement prevailing.

Confucian IR and foreign policy facing estranging alters

Confucian relations posit that all are bound to be related.Footnote 45 Therefore, Confucianism predisposes international relations to pre-empt estrangement with the aim of mutual acceptance between all. Socialising self/stranger is the major agenda of Confucian relations. In the classic wisdom, the pre-emption of estrangement calls for gift giving and name bestowing, rather than annihilation or conversion, because the latter approach would disclose the incorrect strangeness of the self to the alter in the eyes of onlookers. On the other hand, assimilation will presumably arise naturally provided that Confucianism remains attractive. In the long run, this means repeated gift giving and periodical rituals of name bestowing through an imagined common root.

Confucian IR accordingly involves the analysis of the interactions between mis/perceived strangers as well as role-informed acquaintances, defined by the level of improvised relations, as opposed to prior consensual rules and norms, in terms of the mix of gifts and interest. Confucian foreign policy is the practice of self-socialising through gift giving, with the purpose of: (1) ensuring that the self's roles are accepted by each different alter; (2) releasing all to pursue their own interests without worrying about becoming mutually estranging; and (3) preparing for friendly renegotiation whenever interests collide.

In the Confucian relations of Tianxia, nations resemble each other not because of any internalised, natural, rational, and necessary code of conduct, but because they are willing and capable to create roles for each other to reify their spontaneous but socially flexible, inexpressible common origin. Confrontation is only legitimate if it ultimately contributes to the improvisation or restoration of role relations. In this light, an enemy is not a legitimate role in Confucian relations lest it should exemplify strangeness in the self. It can, at best, be a transient role to be jettisoned in the future.

In the first order of Tianxia, metaphors of heavenly natural kinship can unite all. Where such metaphors are unconvincing due to cultural alterity as well as the corrupt practices of the Confucian actors, a show of goodwill is the common way to restore mutual acceptance. As such, a gift that the alter can appreciate and a nominal relationship to shield the interaction from mutual estrangement are two aspects of role making in Confucian foreign policy. The pool of nominal roles is predominantly kin roles in the past, which are usually hierarchical. Nowadays, these nominal roles incorporate modernity. Take the People's Republic of China (PRC) foreign policy for example. They can include comrade, friend, neighbour, brother, partner (with many different versions),Footnote 46 and so on, but the same categories may entail vastly different gift-giving arrangements while the same arrangements may apply to different categories. These roles are not internationally consensual roles, but historically familiar and should be appropriate internally as well as bilaterally. Gift giving is a separate process that is oriented towards the benefit of the alter. Gifts are improvised for others in their contexts to encourage them to accept the PRC as it is.

The PRC has, historically, had multilateral self-role conceptions, for example, a responsible major power, a world revolutionary, a socialist nation, etc., which are neither constituted by any consensual rules, nor constitute any bilateral interactions. In fact, few specific foreign policy implications can be drawn from them, nor is this the intention. As such, the aim of having multilateral roles is to calm others’ alert at the PRC's being self-centred, and demonstrate its socialisability.Footnote 47 There is a conscious effort in these self-naming attempts not to cause surprise. At most, a multilateral role can justify boycotting the West from imposing rules in the developing World on the ground that no one should be left out or singled out as failure if multilateralism is meant to include all equally. Rarely does it involve rule setting. Foreign policy agency lies more in the abovementioned bilateral roles than in the multilateral roles.

Even so, with the right of nature having evolved into a Western relational habitus to oblige all nations to care for human rights, regardless of their specific relationships or identities,Footnote 48 the PRC cannot escape the expectations to enforce multilateral rules to establish a minimal level of resemblance to Western countries.Footnote 49 Acceptance of a newcomer by the West as a normal state would be unlikely without successful role taking.Footnote 50 The PRC is caught between taking sides to win acceptance and avoiding taking sides to remain related to all, albeit separately achieved. This is particularly poignant regarding the global agenda of anti-proliferation, for example, which can be a good background issue for the subsequent case study. This agenda is also illuminating in the sense that the Western countries are stronger than the PRC, and the PRC than NK, but NK has not easily given in to the socialising pressure that trickles down.

Given that anti-proliferation is a regime encompassing allegedly ‘normal’ states, Beijing must weigh the priority between Washington, an apparent stranger with whom Beijing seeks a role relationship, and Pyongyang, an acquaintance determined to pursue nuclearisation. Between the two, Beijing has vacillated to show both sides its sincere desire to comply with the expectations of each, and in the process show Pyongyang how much sacrifice Beijing has suffered for its protection. After the first-generation leader Kim Il-sung passed away, the new leadership under Kim Jong-il decided to pre-empt Beijing's further estrangement due to its abortion of role duty (such as supporting NK's nucleariation), as the third-generation Kim Jong-un once did. It took Beijing over a decade to establish the internal legitimacy to decide that the relational value for the PRC to be accepted by the West is too high a stake to renounce while the long acquaintance with Pyongyang could be restored, albeit in disarray currently. After all, in this reckoning, Beijing would be far better placed to protect Pyongyang once entering a good relationship with Washington and its Western allies,Footnote 51 which Pyongyang would understand in due course, if not now. From this perspective, Beijing was able to achieve a balance between internal legitimacy regarding Pyongyang's long-term comradeship and gift giving towards Washington.

The power asymmetry between the two allies does not silence the relatively weak Pyongyang,Footnote 52 whom Beijing could not convince or restrain because Beijing betrays the prior socialist relations that bind Beijing's own identity to Pyongyang's interests.Footnote 53 They are relationally equal actors. In any case, Beijing's self-casting in joining the sanctioning of Pyongyang is largely unconnected with the value of anti-proliferation that undergirds the solidarity between the members of the anti-proliferation regime. A strategic partnership with the US was a priority due to the need to control the risk that China, on the rise, would become increasingly less acceptable to a growing number of countries. Given China's stranger identity in the eyes of Washington, a mutually congruent expectation with Washington would create a salient role for Beijing, through which Beijing may assess all other future relationships, including the request for Pyongyang to abandon nuclearisation.

Pyongyang's act in shaming Beijing for its betrayal led to the perception that the Sino-NK relationship is beyond repair.Footnote 54 From the relational perspective, Pyongyang's strong sanctions actually testify to the strength of the relation.Footnote 55 Hindsight confirms that Beijing was constantly on the alert to resupply necessities to NK at the first sight of a forthcoming NK-US rapprochement, without conditioning such supplies on Pyongyang's continuity or even the effectiveness of denuclearisation. In other words, Beijing's compliance with anti-proliferation is intended to satisfy the expectation of estranged Washington. Its tolerance of being reduced to a betrayer of Pyongyang, despite the latter's rejection of Beijing's advice regarding denuclearisation, was already maximal. (Pyongyang's role leverage over Beijing will be discussed later in the case study.)

The Confucian relations are biases towards the restoration, reinforcement, and enhancement of the reciprocal role relations while Western IR expects to see a newcomer socialised into becoming a subscriber to the consensual rules. With Washington again resorting to competitive relations in general and economic sanctions in particular, embedded in the right of nature, Beijing's quest for acceptance fails badly. Beijing appeals to the nominal and abstract discourse of a ‘Shared Future for Humankind’. Ensuing Chinese foreign policy attempts consistently to create bilateral partnerships elsewhere to insinuate that: (1) the responsibility of the nascent US-China rivalry lies not in China; and (2) the window of opportunity for Washington to begin a partnership role remains open. This requires Beijing to make greater concessions to both the EU as well as the Global South first and then the US, presumably after a partnership has been achieved. Thinking Tianxia while acting bilaterally in this way, Beijing is able to explain away its own strangeness from the liberal international relations and wait for Washington to reverse its estranging behaviour.

Case study: Pyongyang's improvisation

I employ Pyongyang as a case because it has been an incorrect stranger to both the Western and Confucian relations for almost two decades. I rely on the notion of stranger to explain Pyongyang's quest for acceptance, as opposed to power, and its use of role casting instead of alliance to illustrate the contribution of Confucian IR.

As Kim Jong-il came to power amid the breakdown of the Socialist camp, he pursued an isolationist role of being the socialist substitute for the USSR to continue the bipolar rivalry with the US. Pyongyang was estranged from Beijing, too, due to the latter's diplomatic recognition of Seoul and its reform and openness to the US as well. Both practices undermined Kim Jong-il's legitimacy. Kim cast Washington as an enemy, and the Bush administration's conservative turn confirmed this expectation.Footnote 56 It simultaneously cast Beijing as a betrayer, an image that Beijing shunned. Neither Beijing nor Washington accepted Pyongyang's isolationist role as viable in their relationalities, defined respectively by prior rules and the NK-China bilateral history. Pyongyang's determined quest for nuclear weapons reflected the assessment that neither was trustworthy. The ultimate motivation is, nonetheless, relation qua acceptance – acknowledging NK's nuclear status in the anti-proliferation regime, ending all of the sanctions, and permanent peace and security for the Korean Peninsula and the world.Footnote 57

The case will illustrate the processes that led to the most explosive breakthrough that occurred in June 2018 between Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump. They were seemingly permanent rivals, but succeeded in holding a historical summit.Footnote 58 In a nutshell, Pyongyang evoked nostalgia for nationalism and kin metaphors in both Seoul and Beijing, respectively. It took advantage of the existing role relationships between Washington and Seoul to explore a new role relationship with Washington. All three reverted quickly, too, indicating that the drive away from strangeness can override the incongruent role conceptions that appeared deeply rooted in earlier interactions. The reversal of the bitter interactions overnight between Pyongyang and Beijing attests to the irrelevance of Realist power.

Pyongyang's five prior relations

A nation usually has many prior relations, which restrain its agency for relating to strangers. A review of the literature yields five relations, inductively. These are usually prior multilateral relations that are not amenable to either Pyongyang or its alter.Footnote 59 Within the limited number of relations that remain subjective to Pyongyang's role making, they are either bilateral but contested by Beijing and Seoul, or unilateral. However, the dominant ones since the end of the Cold War have apparently been the hegemonic relations led by Washington, aimed at synchronising all nations according to, in our case, the anti-proliferation agenda. Pyongyang tried to take small steps of concession as a gift to cast Washington into a security provider, but failed due to perceived insufficient conformity to anti-proliferation.Footnote 60 In response, it adopts a ‘powerful state role’,Footnote 61 which in hegemonic relations is equivalent to a completely estranging role of a ‘rogue state’.Footnote 62

Related but distinctive are the postcolonial relations arising from the Japanese colonial legacy.Footnote 63 Tokyo's dual role as a former colonial master and a US ally makes Pyongyang's aversion towards Tokyo almost irresolvable. Pyongyang asserts its independence and power by denouncing Tokyo's dependence on Washington. A break would have to originate from Tokyo's economic aid qua gift giving to Pyongyang.Footnote 64

The Juche Idea (Thought of Subjectivity) has been the single most important role source, that has given the NK people the morale, reason, and determination to strive together to attain all-round autonomy.Footnote 65 Kim Jong-un has been particularly vulnerable in inheriting the Juche spirit as a third-generation leader, if not because of his determination to resist the legacies of his father, Beijing, and Washington. The triadic revulsion provides him not only with a desired independent mark on the Juche identity, but also the image of a ruthless leader in the eyes of Washington – an ontological stranger to the right of nature. A change occurs only after the Juche identity, originally enacted by the powerful state role, is extended to include a development state role.Footnote 66 This role opens the window of opportunity for Tokyo, Beijing, and Seoul to arrange economic gifts.

Pyongyang has more room for choosing between entry and exit in two other prior bilateral relations. One involves Korean national relations, as the Cold War split Korea into two regimes.Footnote 67 Of the entire world, only Pyongyang and Seoul directly subscribe to Korean national relations, which obliges both sides to enforce either an integrating or a conquering platform towards the other.

Pyongyang inherited the fifth prior relation from the historical relations with tributary China, which later continued in the shape of the allegedly comradely, kindred relationship with Socialist China.Footnote 68 Consequently, Pyongyang automatically anticipates Beijing's support during times of need and resorts to defiance if dissatisfied. Embarrassingly for Pyongyang, Washington may blame Beijing instead of Pyongyang for the latter's nonconformity. Because Beijing likewise relies on the bilateral relations to fulfill its reciprocal self-identity, shaming, for example, purging the pro-China forces in NK, can be Pyongyang's threat to estrange Beijing while actually a brinkman's request for compensation and restoration.Footnote 69 Pyongyang has the leverage to oblige Beijing to remain silent regarding its recalcitrant acts or to boycott interventionism on its behalf.Footnote 70 However, Beijing felt equally obliged to meet the role expectation of Washington to support anti-proliferation.

Pyongyang's repeated missile tests to deter Washington as well as distancing from Beijing testify to a powerful state role,Footnote 71 in a quest for the ultimate status as an equal party to the Treaty of Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. While the estranging role conception of a rogue state is by all means transient, improvising a resemblance either in terms of Pyongyang committing to anti-proliferation or being accepted into the nuclear club is unrealistic. Instead, improvising a resemblance through gift giving can be the alternative. In reality, Seoul substitutes for Beijing as the site for Washington and Pyongyang to improvise a common network.

Inter-Korean relations

Moon Jae-in, who passionately pursues the rehabilitation of inter-Korean relationships, was inaugurated in May 2017 as the SK President. He immediately invited Pyongyang to form a joint Olympic team in the South in February 2018. Kim accepted and sent Kim Yo-jong, his sister, to lead the delegation. A summit was arranged for Kim to meet with Moon in April. Kim's agreement to a Korean national role enables Moon to act on his behalf. Thereby, a total stranger, if not an enemy, suddenly gained access to the Washington-Seoul alliance through a gift for Kim from Moon. Before Kim arrived in Seoul, he forwarded a gift-like message respectively to the two most powerful players – Washington and Beijing – both of whom the powerful-state-role player had fearlessly antagonised in 2017. To begin with, Kim himself paid a secret but later highly publicised visit to the Chinese President, Xi Jinping, to honour Beijing's superior Socialist and strategic role. Consequently, Beijing not only reversed its estrangement from Pyongyang but even regained the higher position in the hierarchy. What a gift for Beijing!

On the other hand, Pyongyang did not trust Washington's guarantee. While a stranger to rules, Pyongyang demanded that Washington's guarantee of its security and equal status was the proper first step towards ending their mutual strangeness. For Washington, the proper first step towards reducing strangeness was contrarily for Pyongyang to comply with the anti-proliferation rule rather than any bilateral agreement. In between, Moon took advantage of his dual role as both an inter-Korean patriot and Washington's faithful ally. Kim cast Moon in a Korean national role; Moon cast Trump in an ally role. Thus, there was no risk of Kim being rejected by Trump. Besides, Moon brought a significant gift from Kim – forgoing the cliché of ‘the reduction and withdrawal of US forces from SK’.Footnote 72

The first encounter was sensational. Kim was the first NK leader to set foot in SK. After crossing the line, Kim improvised an onsite invitation to Moon to cross back into NK. Chung-in Moon, who had attended all three summits since 2000,Footnote 73 pointed to such ritual symbolism as a crucial step towards the success of the ‘audacious’ third summit in Panmunjom. He highlighted a statement in a NK report that ‘it was an act that demolished the artificially drawn demarcation line. That impromptu gesture by Kim moved all Koreans.’ The 12-hour gathering succeeded in ‘restoring normal inter-Korean relations’, enacting a shared one-nation role in agreeing a joint liaison office, a spirit of national reconciliation and unity, the reunion of separated families, the modernisation of the eastern transportation corridor, and the building of roads between Seoul and Sinuiju.Footnote 74 The consensual reference to ‘the nation’ in the Panmunjom declaration was regarded ‘as a starting point for putting an end to the history of division’, and ‘inheriting and further fostering the unification plans’ of 1989 and 1994.Footnote 75

National relations trickle down to constitute interpersonal relations, too. In Chung-in Moon's words, Kim's ‘charm offensive was taken seriously by many’ and even became a ‘sort of rediscovery of Kim’. Furthermore, the personal trust and amity between the two leaders and their spouses were visible and the ‘endless exchanges of toasts among them cemented human networks, signaling a bright future for inter-Korean relations’. All of this was down to Kim's reliance on Moon's willingness to play ‘the role of honest broker’, including numerous clandestine contacts between officials to persuade Pyongyang to proceed.Footnote 76

The historical relations

Beijing's compliance with Washington's expectation that Beijing would support denuclearisation alienated Pyongyang.Footnote 77 Comparing the role analysis that combines relational analysis with that which does not,Footnote 78 the latter is far more pessimistic. Beijing expected Pyongyang to remain acquiescent, for a short time at least. This, for Beijing, was to overcome its own estrangement from Washington through a gift of complying with the anti-proliferation rule for the time being. From Beijing's perspective, eventually, Pyongyang would understand that being an acquaintance in the major power relationship would enable Beijing to protect Pyongyang from US intervention.Footnote 79 There was also speculation about Beijing's anxiety regarding its own sidelining regarding the issues of inter-Korean relations and Pyongyang-Washington summitry.Footnote 80 Beijing could have done little about this, had this speculation proved true.Footnote 81 Although annoyed by the high profile of Pyongyang's resistance based upon the Juche Idea, Beijing displayed enormous pleasure as well as honour in celebrating Kim's March visit, as if Pyongyang's pique in the recent past had never happened.

The contemporary sovereignty and historical vassal are currently parallel roles for almost all East Asian neighbours of China.Footnote 82 Such a trajectory contextualises the contrivance of the Juche Idea, but the sovereign relation here does not incorporate a prior resemblance of the right of nature, as between EU nations. Being a sovereign actor with each other entails mutual estrangement and requires improvisation and constant negotiation, at times inspired by the historical tributary relations, between the two long-term acquaintances. In the latter relations, Pyongyang could afford to be recalcitrant without suffering any security anxiety and even take advantage of the embarrassment created for Beijing, which would appear to be failing in its benevolent role.

In the same vein, Beijing's siding with the international sanctions against Pyongyang's nuclearisation is more a double play of showing displeasure to the acquaintance Pyongyang and placating the seeming stranger Washington than complying with the anti-proliferation regime.Footnote 83 As such, Beijing's commitment to sanctions could not be wholehearted because they circularly estranged Beijing from an acquaintance. In reality, Pyongyang could not afford to sideline Beijing. Seoul has been so dependent on Washington that, from Pyongyang's perspective, Seoul's goodwill could not effectively service the former's quest for equality and respect, apart from by serving as a credible messenger. To earn respect from Washington, Pyongyang needed to act in the name of a far greater relational entity, that includes China. Ironically, when they both faced pressure from Washington, they could not cooperate between themselves. With contact with Washington in preparation, Pyongyang had relieved Beijing of the pressure to comply with anti-proliferation.

It has been a relational prophecy that China and NK are bound to be related closely. That is why Pyongyang could be almost certain that Beijing would be willingly cast as a helping hand and delighted.Footnote 84 In fact, Kim appeared in the media to be busy taking notes while Xi was speaking. This dramatic humility constituted a ritual metaphor for the tributary relationship. Xi recollected how past leaders resembled ‘close relatives’; Kim reiterated that his trip was precisely based on ‘this passionate relationship and the moral propriety’.Footnote 85 Both enlisted the arrival of spring as a metaphor to describe their first meeting, insinuating the mutual acknowledgement of a misunderstanding now bygone. China's soft power lies in its patience with role incongruence and Kim's in knowing that China can merely await his return. They are both relationally equal, despite a huge difference in size, and socially hierarchical within their historical relationship.

The first visit took place after the US secret envoy visited Pyongyang to confirm Washington's readiness to attend a summit and prior to Kim's first summit with Moon. Kim's role enactment of Xi, as the former's senior, solidified his confidence about meeting with Trump as an equal.Footnote 86 Most importantly, Beijing had no intention of taking advantage of Pyongyang at a time when it was vulnerable, nor retaliating against its recalcitrance. Rather, Beijing was ready to support Pyongyang's desire eventually to become a developmental state. In fact, there was no other appropriate role left for Beijing. Between controlling and supporting Pyongyang, the greater power's choice was strictly in line with the weaker power's expectation.Footnote 87

The hegemonic relations

Through Seoul, Pyongyang is no longer a stranger to Washington, neither an acquaintance, who would comply with the role duty of denuclearisation. To begin with, the Panmunjom Declaration deliberately adopts a textual structure in the order of inter-Korean relations, a peace settlement, and denuclearisation to indicate the desired sequence and synchronous approach that binds the security of Pyongyang to the speed of denuclearisation.Footnote 88 This is a strategic road map for targeting Washington's earlier insistence on unconditional, complete denuclearisation. Washington was able to listen to Seoul, though, and receive an indirect promise from Pyongyang regarding the initiation of unilateral, complete denuclearisation.

In addition, the issue of a peace treaty to end the Korean War, which was an unlikely message to be delivered directly from Pyongyang to Washington, was then presented to Washington. The treaty insinuated that Pyongyang was becoming a normal state, that would not require nuclear weapons. Premised upon the Washington-Seoul alliance, the inter-Korean détente could merely implicate Seoul's role-making effort to oblige Washington to support its ally by joining in the peace treaty process. In fact, even by the time of the Winter Olympics, the expectation regarding Seoul was already that collegiality at the Games would be ‘inducing inter-Korean dialogue to act as a driving force for US-NK dialogue’.Footnote 89 Without Seoul's role as ally in the hegemonic relations, Kim would have lacked any channel by which to cast Washington into recognising NK as a nuclear power before proceeding with complete denuclearisation.Footnote 90

Moon Jae-in enacted his junior ally role by praising Trump for the ‘maximum pressure’ approach, in the expectation that the stoked ‘ego of the impulsive American leader’ would support his effort.Footnote 91 Moon was able to reassure Pyongyang that it was unnecessary to worry about regime replacement. Both sides understood that the inter-Korean relations were ‘designed to provide a more secure environment in which NK could maintain its commitment of denuclearisation and continue negotiations with the US’.Footnote 92 Moon also facilitated an opportunity for Washington to review ‘the level and the scope of denuclearization for the first time’ by arranging for Kim to identify them in their joint declaration.Footnote 93 No risk of losing face with Washington was possible through such a medium.Footnote 94

Considering the fast-improving inter-Korean relations, with or without Washington, the peace processes would continue on the peninsula. Both Koreas have appeared determined to congeal the mutual drive for an increasingly national relationship. If Washington had rejected Pyongyang's indirect denuclearisation offer by Seoul, it would have risked witnessing an inter-Korean detente without denuclearisation. This would have seriously estranged the Washington-Seoul relationship and jeopardised Washington's leadership role, despite the fact that Washington seemed far too powerful to resist in the eyes of Seoul.

In other words, it was not only the bilateral relationship with Seoul that Washington had to consider. Seoul's request for a summit between Kim and Trump simultaneously involved three bilateral relationships. Seoul was, in principle, issuing a request based on its role as a relationally equivalent (and actually the only other) member of the Seoul-Washington alliance. This was not a familiar rule-based act. Washington was still obliged to respond positively, even if the junior ally seemed to act incompatibly with what the alliance was supposed to achieve; namely containing, if not overthrowing, Pyongyang. The situation would be relatively easy for Washington, once Pyongyang and Washington could develop a direct relationship. It would contrarily oblige Seoul, as a US ally, to pace the inter-Korean relationship in accordance with the evolving relationship between Washington and Pyongyang.

Conclusion

Both relations and roles are intersubjective, but relations constitute the actors prior to their interaction while roles require the actors to improvise during the interaction according to each other's conditions. These two theories share significant epistemological common ground in terms of substituting the mutuality of actors for their autonomy and neutralising the analytical relevance of power by introducing culture and identity.

In order to avoid the mutual estrangement caused by differences in culture and identity, the flexible style of Confucian relations oblige actors to establish and maintain relations through improvising roles that are agreeable to each other. This contrasts rule-based relations, the stronger ontological sensibilities of which enable the actors already to feel a level of solidarity prior to exploring their differences. Confucian relationality evades solidarity. Under Confucianism, humankind is neither shaped in the same image as the Christian God nor has the same capacity to relate to Him. As a result, the amorphous heavenly reason is embodied by an unlimited variety of dissimilar lives. Therefore, universal rules and norms to constitute equally people who are alike or generate the community of practice in the Christian and liberal traditions are implausible.

Western IR is rooted in the imagined state of nature, where strangers become prudent citizens by subscribing to an indiscriminate social contract. Given Tianxia's aversion to universal rules, gift givers are reduced to unruly strangers from the social-contract perspective. On the other hand, whenever gift givers fail to enlist appreciation of the Western alter, they see the latter threaten to expose their internal strangers. Western IR finds a place in Confucian IR when: (1) gift givers strategically follow a universal rule in an event as a gift to win temporary acceptance by the parties to a social contract; or (2) the parties to a social contract relinquish their demand on the rule in an event as a gift to ensure that non-subscribers feel accepted and gradually consent to conversion in the future.Footnote 95

Wherever role relations have been practiced with a bilateral consensus, these historically already improvised relations, for example, the NK-China relationship, create a bilaterally specific prior relation – they become acquaintances. Its enforcement and reproduction differ from the enforcement of the Western style of prior relations, though. Namely, prior improvised relations between acquaintances, that come with certain consensual role norms, are not interventionary in nature, since they are aimed at camouflaging estrangement. Rather, a breach of Confucian prior relations calls for further gift giving to reconfirm it or sanctions to restore/rebuild it. Sanctions are justified only if their purpose is to restore reciprocal role play. They are by no means an ontological pursuit, so they can be improvised to a greater extent than prior relations. This explains how Pyongyang and Beijing were able to restore their seemingly severed relationship almost overnight.

An additional and yet significant point of comparison is how to cope with strangers’ relations. Given the ontological vagueness under the Tianxia circumstance, politically incorrect strangers inside are simply exposed by those without a past record of reciprocity, that is, NK and the US, or China and the US, in our case. The task for them is, therefore, to exchange gifts and improvise mutually beneficial rituals to stabilise future harmonious relations. Since all are bound to be related, these processes will continue despite their failure at a particular time. If, however, the law of nature as well as the right of normal states is formulated as ‘ontological normalcy’, strangers to it essentially pose an ontological threat, with the result that strangers unavoidably become a target of conversion, quarantine, or battle.

Pyongyang in 2018 is an excellent case, in which security is ultimately more about acceptance, that is, being related, than power. Rivalry is only rational when it is aimed at restoring relationships. To begin with, NK's Tianxia is so limited that Beijing is the one relevant actor that is still ready to accept NK's role making. NK is, at best, a failed role player, due to its inability, first, to adopt the available roles that are derived from the anti-proliferation regime and, second, even to improvise gift giving to oblige Seoul, Beijing, or Tokyo each to return to certain historically contributive roles. It can only rely on a powerful state role – Juche – which legitimised and yet reinforced its isolation. Pyongyang went as far as to jeopardise its prior security dependence on Beijing, a move to force all others to mind its status and quest for roles acceptable to the national, historical, as well as hegemonic relations.

However, the Tianxia relations oblige all to explore and cultivate a resemblance in order to camouflage strangeness. Indeed, Seoul moved first to end years of rivalry with NK. The Winter Olympics serves as the best stage for ritualising the prior Korean national relations. With the national relations restored, Seoul was able legitimately to act on behalf of Pyongyang, evoke its junior partnership with Washington, and distract the latter from the rigid rules of the anti-proliferation regime and towards exploring ritualised reciprocity with Pyongyang. It is hoped that the extended reciprocity between Seoul and Washington and then between Washington and Pyongyang will convert NK into an anti-proliferation regime. The summit thus marked the very first occasion when NK realistically negotiated its entry into an ontological strangers’ regime. Meanwhile, with Washington's participation confirmed, Pyongyang arranged a show of deference to Beijing and restored the prior hierarchical role relationship.

The case study shows that, at the moment when actors evoke Confucian relations, their sensibilities towards self-/strangers will motivate gift giving that leaves strangeness inside untouched to fulfill the mandate that all are bound to be related. Between those where this is not available, strangers inside emerge, and the Hobbesian state of nature takes over, prompts rivalry, and inspires the social contract that alternatively breeds the rule-based order between strangers. Intervention is required to ensure the socialisation of those not following rules into followers, but gift giving appears an equally compelling socialising mechanism that evades the rules and yet reconnects perceived strangers to the extent that expediently abiding by rules can constitute a gift for the time being. Therefore, two relationalities exist simultaneously on different agendas, between different actors, at different times. Roles are improvised to socialise the actors of different relationalities respectively and also connect them in the intersection. All nations can access both relationalities. Western and Confucian relations are not in an either/or relationship.Footnote 96