Introduction

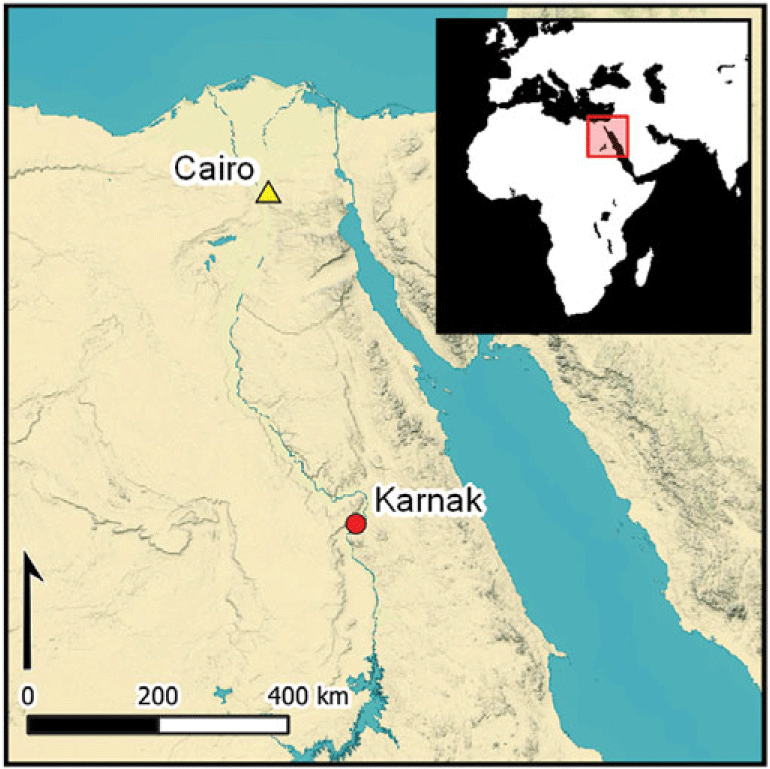

Five hundred metres east of the present course of the River Nile near Luxor (Egypt) stands one of the ancient world’s largest temple complexes—Karnak—at the ancient Egyptian religious capital of Thebes (Barguet Reference Barguet1962). Occupied for some three thousand years, religious areas were dedicated to three main deities: Amun-Ra, Montu and Mut (Figure 1), with additional deities also incorporated into the built architecture. Karnak’s principal domain is the approximately 30ha temple precinct of Amun-Ra (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Location of study area and archaeological features: 1) Amun-Ra temple complex, Karnak; 2) Montu temple complex, North Karnak; 3) Mut temple complex; 4) Kom el-Ahmar; 5) Avenue of Sphinxes; 6) Luxor Temple; 7) temples and necropoleis (not all shown). The core transects outside the Karnak area are published elsewhere (Toonen et al. Reference Toonen2018, Reference Toonen2019; Peeters et al. Reference Peeters2024) (figure by authors).

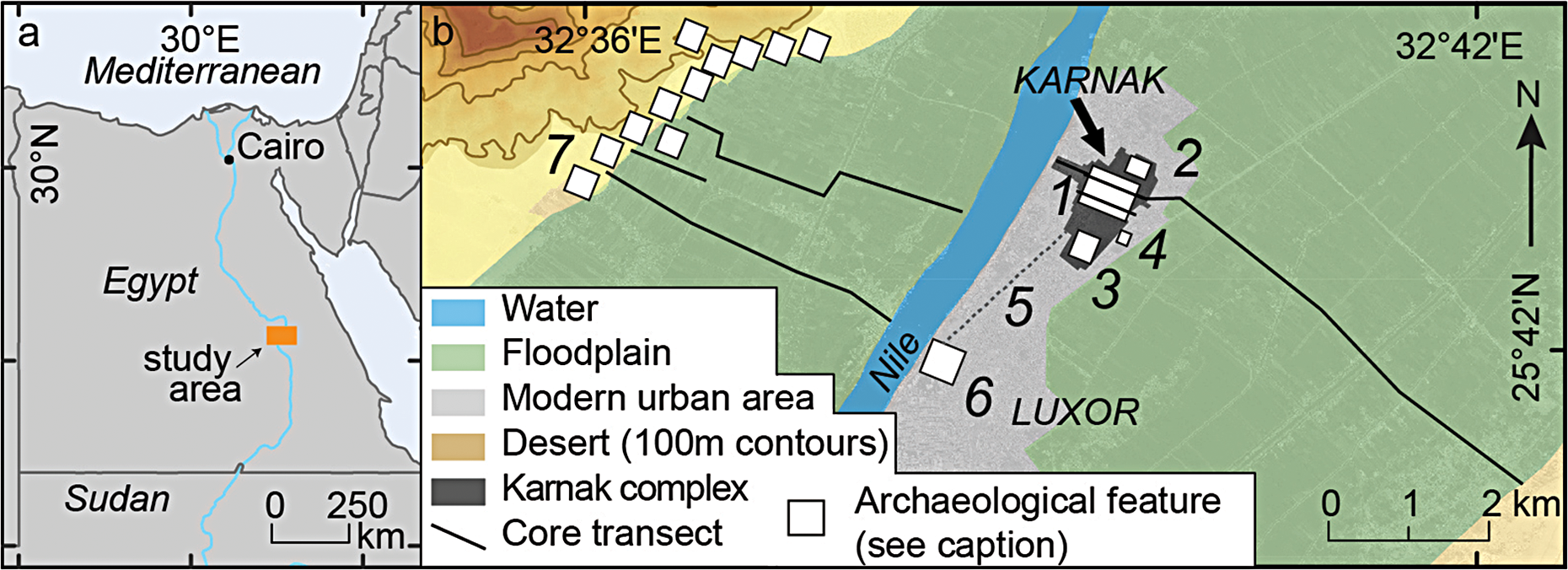

Figure 2. Location of coring sites and transects. a) Plan of the Temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak: pylons (monumental gateways) are indicated with Roman numerals; archaeological excavations as follows: E1 Karnak North (Jacquet Reference Jacquet1983: 80, 95–96, Reference Jacquet2001: 13–14); E2 Ptah Temple (Charloux et al. Reference Charloux2018, Reference Charloux, Abady Mahmoud, Elnasseh and Marchand2021: 924–26); E3 MK Court (Carlotti et al. Reference Carlotti, Czerny and Gabolde2010; Charloux & Mensan Reference Charloux and Mensan2011; Larché Reference Larché2020); E4 Osirian Catacombs (Charloux et al. Reference Charloux, Abady Mahmoud, Elnasseh and Marchand2021: 928); E5 East Karnak (Redford et al. Reference Redford, Orel, Redford and Shubert1991); E6 SE Sacred Lake (Millet Reference Millet2007, Reference Millet2008; Masson-Berghoff Reference Masson-Berghoff2021); E7 Opet Temple (Charloux et al. Reference Charloux, Angevin, Marchand, Monchot, Roberson and Virenque2012: 255); E8 tenth pylon court (Azim Reference Azim1980). The Chevrier Drain is modern. MK: Middle Kingdom; FIP: First Intermediate Period. b) Hand auger in use at AS040; c) percussion corer in use at PC026; d) extracting drilled sediments at PC027 (figure by authors).

Archaeological investigations have been ongoing at the site for approximately 150 years (Legrain Reference Legrain1929; Barguet Reference Barguet1962; Arnaudiès & Laroze Reference Arnaudiès and Laroze2007; Gabolde Reference Gabolde2018), yet the dynamic riverine landscape within which the temple was conceived, built and extended has not been understood in detail and the age of earliest occupation continues to be debated. Most researchers favour a First Intermediate Period (c. 2152–1980 BC; see also online supplementary material (OSM) Table S1) origin for Karnak based on in situ excavated archaeological remains and a written reference to a temple of a ‘Ra-Amun’ from the reign of Intef I, II or III (traditionally Intef II c. 2066–2017 BC; Postel Reference Postel2004: 72–73; Hornung et al. Reference Hornung, Krauss and Warburton2006: 491; Ullmann Reference Ullmann, Dorman and Bryan2007: 4; Millet Reference Millet2008: 308–9; Charloux & Mensan Reference Charloux and Mensan2011: 231; Larché Reference Larché2020: 121). These earliest excavated remains are found in the eastern part of the complex and south-east of the Sacred Lake (Figure 2: E4–6) and variously consist of mudbrick walls (including silos at E4) associated with ceramic material from the First Intermediate Period/early Eleventh Dynasty (Charloux et al. Reference Charloux, Abady Mahmoud, Elnasseh and Marchand2021: 928, 931; Gabolde Reference Gabolde2018: 154–66; Millet Reference Millet2007, Reference Millet2008). Further north, near the Ptah Temple (Figure 2), a hearth is dated to the mid-Eleventh Dynasty (Eleventh Dynasty = c. 2080–1940 BC; Hornung et al. Reference Hornung, Krauss and Warburton2006: 491) (Charloux et al. Reference Charloux, Abady Mahmoud, Elnasseh and Marchand2021: 24, fig. 4). Other authors suggest Predynastic occupation (3900–3100 BC) at Karnak, based on material from old excavations and objects ex situ (Legrain Reference Legrain and Griffith1906a: 21; Franchet Reference Franchet1917: 87, 99; Gabolde Reference Gabolde2018: 135–36, 167).

Recent attempts to reconstruct the palaeoenvironmental setting of early Karnak (Gabolde Reference Gabolde2018; Charloux et al. Reference Charloux, Abady Mahmoud, Elnasseh and Marchand2021) have primarily relied on details obtained from archaeological excavations and limited coring (Millet Reference Millet2007: pl. 39; Bunbury et al. Reference Bunbury, Graham and Hunter2008; Ghilardi & Boraik Reference Ghilardi and Boraik2011). These attempts have often tried to locate ancient river channels by identifying palaeosurfaces sloping down to presumed channel depressions, and by cross-comparing pottery levels found in different excavations. They bring together ideas that an unidentified river channel, of unknown date and size, likely existed east of the site (Redford Reference Redford1988: 37, fig. 8), and that a second channel was probably present during the Middle Kingdom (c. 1980–1760 BC) west of the north-south axis of the Amun-Ra temple—an axis defined by the monumental gateways of the seventh to tenth pylons (Figure 2) (Legrain Reference Legrain1906b: 137–61; Bunbury et al. Reference Bunbury, Graham and Hunter2008: 364, 367). This second channel may have subsequently shifted westward (Bunbury et al. Reference Bunbury, Graham and Hunter2008: 364, 367; Ghilardi & Boraik Reference Ghilardi and Boraik2011; Boraik et al. Reference Boraik, Gabolde, Graham, Willems and Dahms2017: 130–35). The site was thus at some point possibly situated on an island (Egli Reference Egli1959: 40–43; Millet Reference Millet2008: 324–30; Graham Reference Graham, Bietak, Czerny and Forstner-Müller2010), whose northern limit may have been at North Karnak (Figure 2). A channel could have existed further north of this point, as an early Middle Kingdom surface slopes downwards to the north-west (Jacquet Reference Jacquet1983: 95), and ceramics potentially dating from the Middle Kingdom onwards are found at relatively deep levels, suggesting a topographic depression (Bunbury et al. Reference Bunbury, Graham and Hunter2008: 365; Graham Reference Graham, Bietak, Czerny and Forstner-Müller2010: 134; Boraik et al. Reference Boraik, Gabolde, Graham, Willems and Dahms2017: 123). South of the Amun-Ra temple, Late Period ceramics (664–332 BC) at depths of up to 12m may suggest another channel depression, constraining the southern limit of settlement (Lauffray Reference Lauffray1968: 339).

Although informative, these recent reconstructions remain incomplete, drawn as they are from data that are fragmentary, spatially restricted to excavation localities—limiting the scope for palaeoenvironmental conclusions—and often collected as a byproduct of other research objectives. Few dedicated palaeogeographic surveys of the area have been conducted, and fewer than 10 deep (>5m) sediment cores have been published in any detail (Lauffray Reference Lauffray1968, Reference Lauffray1969; Bunbury et al. Reference Bunbury, Graham and Hunter2008; Ghilardi & Boraik Reference Ghilardi and Boraik2011; Charloux et al. Reference Charloux, Abady Mahmoud, Elnasseh and Marchand2021). The geoarchaeological survey conducted by Bunbury and colleagues (Reference Bunbury, Graham and Hunter2008) provides a notable exception, as part of a research programme that preceded the present study. Their preliminary reconstruction was based primarily on 15 sediment cores with an average depth of 4.9m set in locations limited by the hand-augering method.

As detailed below, the present programme builds on this earlier work with a dataset more than four times larger, derived from cores strategically placed to align with the research objectives. Coring covers both the Karnak site and its surroundings, and the data collected are synthesised with archaeological information (Gabolde Reference Gabolde2018; Charloux et al. Reference Charloux, Abady Mahmoud, Elnasseh and Marchand2021), luminescence dating as well as an updated understanding of local floodplain dynamics (Toonen et al. Reference Toonen2018; Peeters et al. Reference Peeters2024). As a result, the reconstructions presented here are the most comprehensive interpretations currently available.

We present information from 61 sediment cores (average depth: 6.4m, maximum depth: 11.65m) (Figure 2, Table S2), most of which were archaeologically dated through analysis of the tens of thousands of ceramic fragments they contained (Table S3). By positioning these cores at relatively even intervals, broadly along northern (‘N’) and southern (‘S’) west–east transects through the site (Figure 3), two cross-sections of sub-surface deposits were created. These cross-sections were then interpreted using standard geoarchaeological methods (Miall Reference Miall1996; Brown Reference Brown1997; Toonen et al. Reference Toonen2018). Isochrons, based on typologically dated ceramic fragments, reveal the palaeotopography (Figure 3) and shed light on the dynamic nature of the environment (Figure 4).

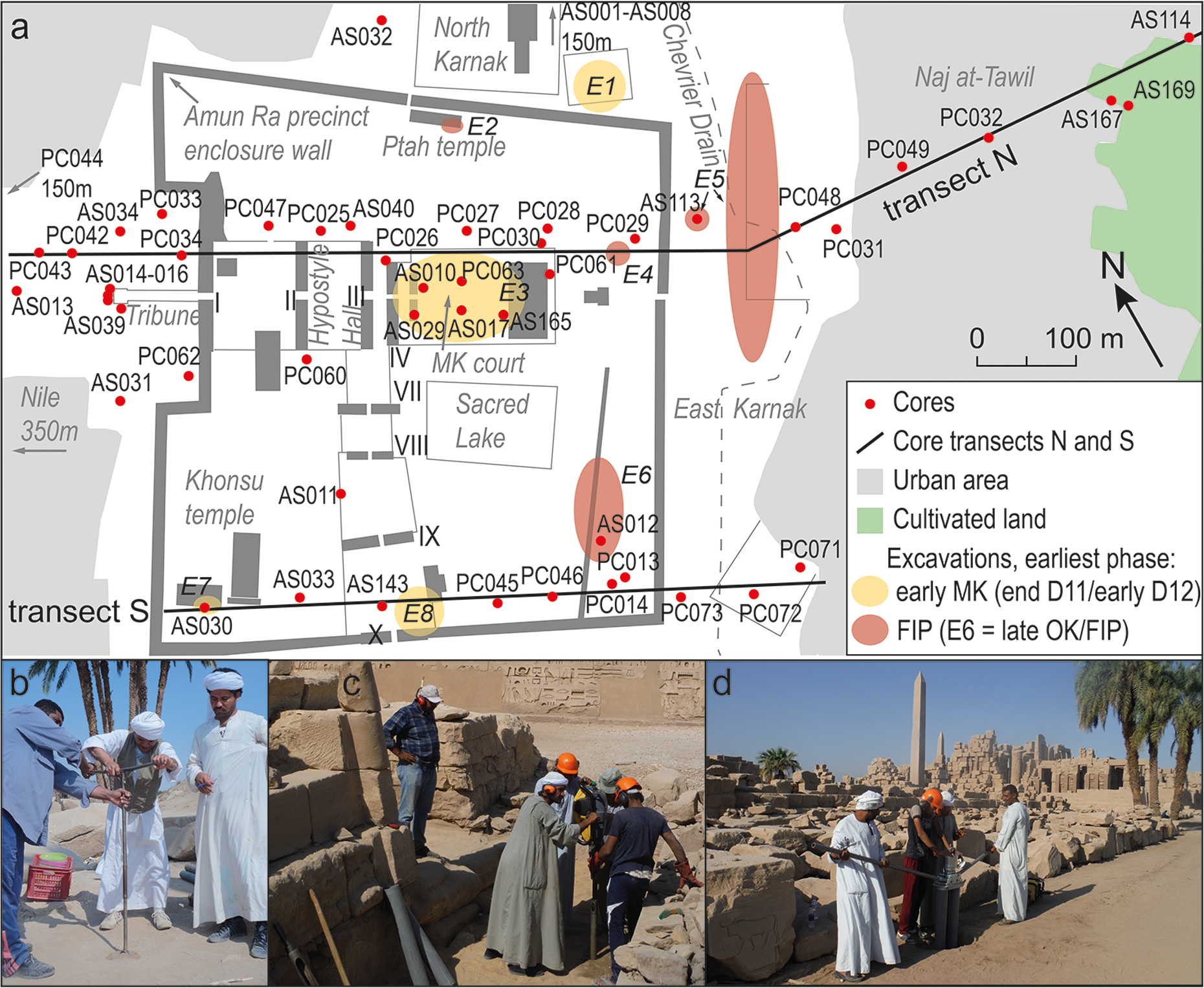

Figure 3. Simplified transects through Karnak: a) transect N; b) transect S. Cores/excavations indicated to aid location (not all shown). Figures S1–3 provide further detail; masl: metres above sea level; NK: New Kingdom; MK: Middle Kingdom; FIP: First Intermediate Period (figure by authors).

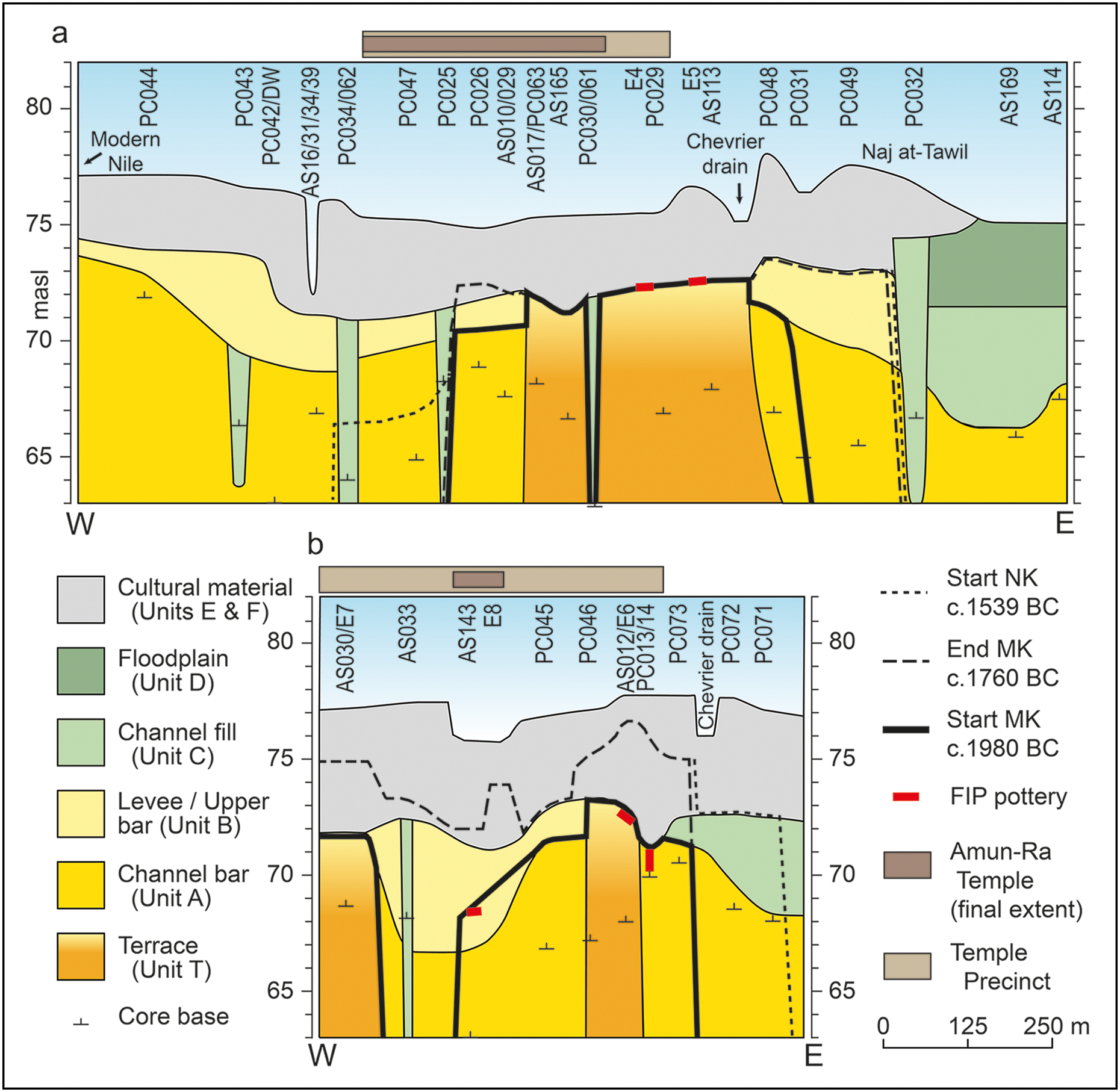

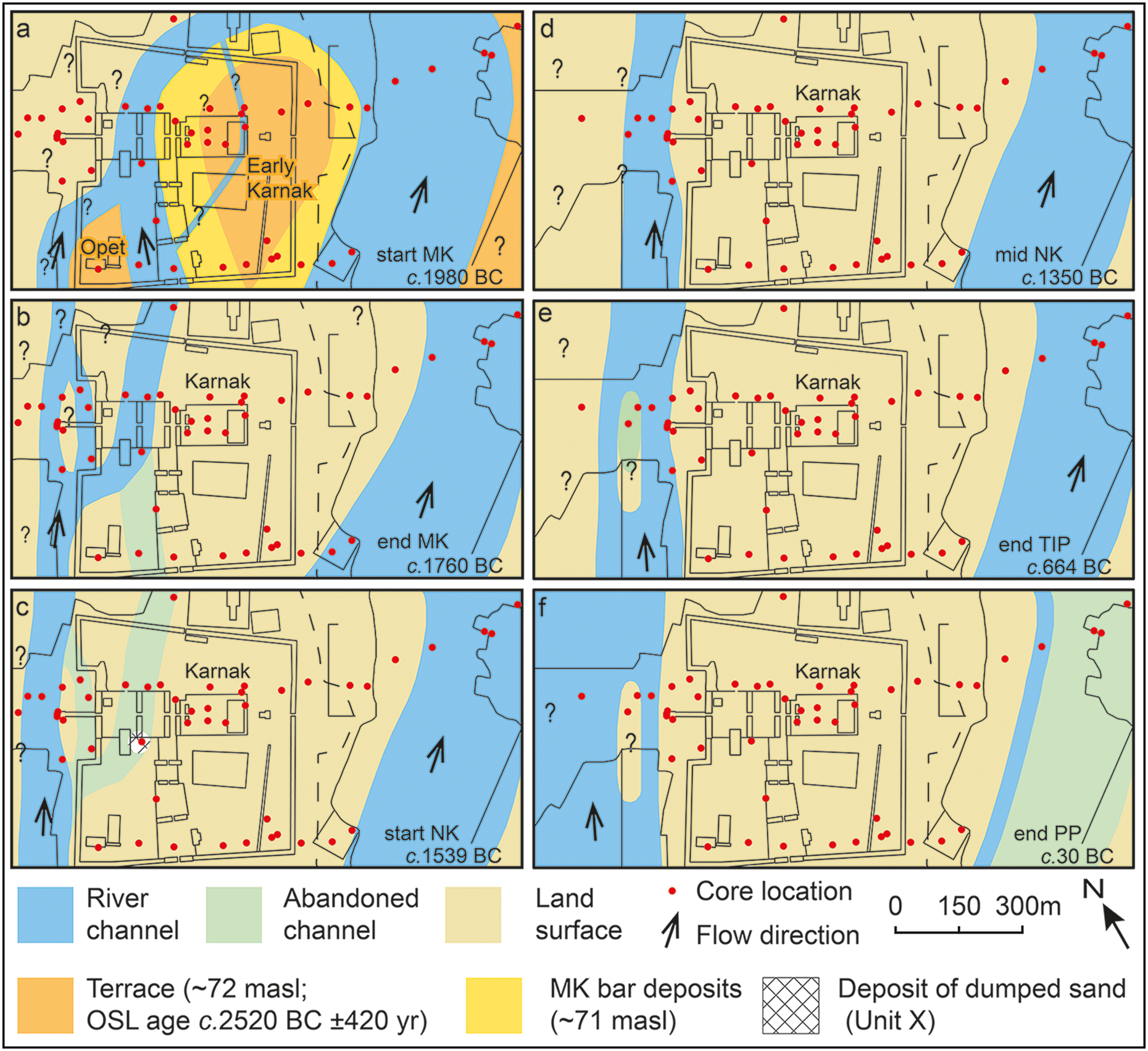

Figure 4. Palaeolandscape reconstruction at Karnak: a) beginning of the Middle Kingdom (MK); b) end of the Middle Kingdom; c) start of the New Kingdom (NK); d) middle of the New Kingdom; e) end of the Third Intermediate Period (TIP); f) end of the Macedonian/Ptolemaic period (PP) (figure by authors).

The work is palaeogeographically contextualised (Figure 1) using lithological and chronostratigraphic information from 142 cores similarly drilled across the wider local area (Toonen et al. Reference Toonen2018, Reference Toonen2019; Peeters et al. Reference Peeters2024), and a novel set of 48 optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) ages from the vicinity of Karnak (Peeters et al. Reference Peeters2024).

Methods

Sediments were retrieved using an Eijkelkamp hand auger (ASnnn) and/or a Cobra TT percussion corer (PCnnn) (Figure 2b–d) and their basic sedimentological characteristics were analysed in the field (see OSM). Recovered sediments were wet-sieved in approximately 100mm intervals, and fractions were manually sorted into ceramic and non-ceramic material. Ceramic fragments were assigned an age within a Karnak-specific typology (see OSM). Through this, archaeological chronostratigraphies were ascertained for most cores in as much detail as possible (Table S3).

Results

Our survey reveals that the entire Karnak zone is ultimately founded on sandy deposits (Figure 3: Units T, A, B). Based on their sedimentary characteristics, particularly their fine to medium sand grade, well-sorted nature and fining-upwards sequences, these deposits are interpreted as river channel sediments, though not all were laid down simultaneously. Further east, and also at isolated localities within the temple precinct, silts prevail (Units C & D). These record infills of abandoned river channels (Unit C) or floodplain sedimentation (Unit D), as fine material is dropped from suspension in low-energy conditions. Atop these sands and silts typically lies several metres of cultural material: heterogeneous deposits comprising the ‘archaeology’ of the site (Unit E), as well as windblown cover (Unit F).

River terrace foundation

Although all the basal deposits are sands, a difference in age is inferred between the lowermost sands in the central/eastern zone of Karnak (Unit T: from the Middle Kingdom Court to East Karnak/east of the Sacred Lake), and the sands at either side (Units A & B) (Figure 3). Unit T contains no in situ ceramic fragments except at its surface, but Units A and B (and all others) usually contain tens to hundreds of ceramic fragments per vertical metre of cored sediment. This suggests that Unit T was deposited pre-occupation, but Units A and B were deposited contemporaneously with occupation. These units are also lithologically distinct.

Further detail is provided by ceramic typology. The oldest ceramics atop Unit T date from sometime between the Sixth and early Eleventh dynasties: c. 2305–1980 BC (core AS012 and excavations E4–6) (Figure 2, Table S3), placing them within the First Intermediate Period or possibly the late Old Kingdom (Old Kingdom = c. 2591–2152 BC). They are of a similar age to the oldest ceramics within Units A and B (early Eleventh Dynasty: c. 2080–1980 BC; Hornung et al. Reference Hornung, Krauss and Warburton2006: 491), in cores AS143 and PC014. This also suggests Unit T is older than Units A and B.

This age difference is reflective of the fact that Unit T, at an elevation of approximately 72m above sea level (masl), is an old river terrace—a preserved remnant of an earlier riverplain—a conclusion supported by 29 more cores drilled to the east of Karnak (Peeters et al. Reference Peeters2024) (Figure 1). The relatively large grain size (150–350µm) of Unit T sands suggests deposition by fast-flowing water. Later, this alluvial plain was eroded on both its eastern and western sides by incising river channels, leaving a segment of high ground—a terrace (island)—in the east/south-east of the present site that then became occupied. The courses of the river channels that carved out this island are marked by Units A and B. Unit A is interpreted as lower channel bar sediments: sands laid down near the margins of the channels (Miall Reference Miall1996), which generally fine upwards into the upper bar and levee sediments of Unit B. After deposition of Unit T ceased, the terrace top lay above the normal level of inundation, since Unit B deposits dating to the early Middle Kingdom are nowhere situated atop this terrace.

The 29 cores drilled further east (Peeters et al. Reference Peeters2024) show that the terrace existed for several kilometres in this direction, and they also provide an OSL age for the terminal phase of deposition at this level of 4.54±0.42 ka (2520 BC ±420 years). The fluvial erosion on either side that formed the terrace/island would thus have taken place after this date.

The age of this river terrace is important because it places a temporal constraint upon earliest occupation at Karnak. When this area was being actively deposited by fast-flowing water, at and prior to 2520 BC ±420 years, it was unsuitable for permanent occupation/construction, although non-permanent activities may have occurred there during annual stages of low flow. After this date, incision resulted in the formation of the terrace segment/island, upon which occupation could have been initiated. This chronology corroborates the ceramic information: the earliest ceramics date from sometime between c. 2305–1980 BC, within the OSL 68.27% (1σ) confidence interval.

The coring results cannot precisely delimit the northern or southern margins of the island. Five cores further south, at the temple of Mut, provide little information, primarily encountering Unit E only (AS024–028: Figure S3). However, the narrowness of the terrace observed in transect S (Figure 3b) suggests proximity to its southern tip, corroborating previous ideas (see Introduction). The northern limit may be at North Karnak, based on earlier cores and excavation data (Bunbury et al. Reference Bunbury, Graham and Hunter2008). The island may, therefore, have extended from North Karnak to near the southern enclosure wall, an area of approximately 10ha (Figure 4a). A small channel crossed the terrace at the rear of the extant Amun-Ra temple, shown by Unit C in PC030 and PC061(Figure 3a); the ceramic records of these cores suggest that the channel gradually silted up through the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period (Second Intermediate Period = c. 1759–1539 BC) (Table S3).

It also appears that another, smaller terrace segment lay in the south-west corner of the site, upon which the Opet Temple was constructed (Figures 3b & 4a), since early Middle Kingdom archaeology is found atop Unit T (AS030) in this location (Charloux et al. Reference Charloux, Angevin, Marchand, Monchot, Roberson and Virenque2012). The deposits here (Unit T) are lithostratigraphically correlated with the main terrace segment. They were deposited concurrently and were originally continuous across the area. However, by the early Middle Kingdom (if not before) the areas were interposed by an incised channel (Units A, B, C in AS033, AS143, PC060, AS011, hosting early Middle Kingdom ceramics), thus placing early occupation on individual islands (Figure 4a).

Western Nile channels

The channel that separated the ‘Opet terrace’ from the main Karnak terrace was one of various minor river courses in what is now the western part of Karnak. During the early Middle Kingdom this channel had its eastern bank near the third pylon, within the courtyards of the seventh to tenth pylons, themselves constructed centuries later during the New Kingdom (c. 1539–1077 BC) (Figures 2 & 4a). This bank is indicated by an interpreted erosional margin in the ‘start MK’ isochron (Figure 3: near AS143 & PC025), and archaeological investigations showing a sloped margin (Legrain Reference Legrain1906b). This channel, itself marked by Unit A, was also active earlier, as First Intermediate Period ceramics are found in AS143 within levee and bar deposits. The width of the channel was 90–150m, as its western bank was east of the ‘Opet terrace’ segment at AS030. Recent interpretations may further constrain the placement of its eastern margin under the New Kingdom Hypostyle Hall (Larché Reference Larché and Colin2023).

The southern part of this channel—west of the later eighth to tenth pylons—naturally silted up in the later Middle Kingdom (Figure 4b), recorded by ceramics of this period embedded within channel fill deposits (AS011, AS033: Table S3), with Second Intermediate Period and New Kingdom cultural deposits above (Unit E). This process allowed for a land connection between the ‘Opet terrace’ and the main terrace (the focus of early Karnak) in the south-east. However, the channel maintained a river connection north of the ‘Opet terrace’ through the Second Intermediate Period (Figure 4b), as the infill in this section is dated to the beginning of the New Kingdom (PC060, PC025, PC047: Table S3).

Part of this northern section of the channel, immediately south of what was shortly to become the Hypostyle Hall, was deliberately filled in with a 3.6m-thick deposit of desert sand (Unit X in core PC060; see OSM). Since this deposit is bracketed above and below by sediments hosting similar late Seventeenth Dynasty/early Eighteenth Dynasty ceramics (around c. 1540 BC; Hornung et al. Reference Hornung, Krauss and Warburton2006: 492), it seems likely this infilling took place at the beginning of the New Kingdom (Figure 4c). This action targeted a channel that was already silting up, as channel fill deposits lie underneath Unit X, and PC047 and PC025 directly north of the Hypostyle Hall also indicate a natural silting up at this time (Figure S1). Another minor channel may also have naturally silted up a little further west, in the vicinity of the first pylon (itself constructed later), recorded by Unit C in cores PC062 and PC034 (Figures 3a & 4b–c).

All these fluvial changes seem to be connected to the development of a substantial river channel further to the west, which was present by the New Kingdom, if not before (Figure 4b–c). This channel subsequently migrated westwards to become the main modern branch of the Nile (Figures 1 & 4d–f). Deposits indicating its existence (Units A & C) were retrieved from cores AS031, AS039 and AS034 and all others further west. This channel is dated by the earliest (Middle Kingdom–early New Kingdom) ceramics encountered in fluvial deposits in AS039, as well as from a radiocarbon date in fluvial sediments which suggests its existence certainly by the early New Kingdom (Ghilardi & Boraik Reference Ghilardi and Boraik2011). Subsequent westward movement of the channel is shown by more recent ceramics in Units A and B further west in PC042–044 (Table S3), as well as the upward-sloping nature of the units in this direction (Figure 3a). As the river migrated and aggraded, it left younger deposits at higher levels (prior to c. 2000 BC the river was incising, it was aggrading thereafter; Peeters et al. Reference Peeters2024). Fine-grained sediments at PC043 may also record a subaerially-exposed bar within the Nile (Figure 4e–f), potentially corroborating textual sources (Boraik et al. Reference Boraik, Gabolde, Graham, Willems and Dahms2017: 99–101, 103–6) (see OSM).

Eastern Nile channel

A key finding of our research is the evidence for and dating of a substantial Nile channel to the east of Karnak. Bar and levee deposits in this location (Units A & B), and the occurrence of relatively young ceramics (New Kingdom–Macedonian/Ptolemaic period; Macedonian/Ptolemaic period = 332–30 BC) at lower levels than older, early Middle Kingdom surfaces further west (Figure 3) provide evidence for a channel depression. That this channel was active during the First Intermediate Period and early Middle Kingdom is indicated by the plentiful, stratified early Middle Kingdom ceramics embedded in fluvial bar deposits in PC049, and First Intermediate Period ceramics in riverine deposits in PC014 (Figure 3). The channel then shifted eastwards during the Middle Kingdom and/or Second Intermediate Period (Figure 4a–c). In the early Middle Kingdom, the channel’s western margin was in East Karnak, between PC048 and PC049 in the north (near PC031: see OSM), and between PC073 and PC072 in the south, shown by the steep slope in the ‘start MK’ isochron between these cores (Figure 3). By the New Kingdom, however, the western margin was between PC049 and PC032 in the north (within the modern village of Naj at-Tawil), and further east than any of the cores drilled in transect S, indicating an eastward shift of approximately 150m. The New Kingdom archaeology at Kom al-Ahmar, slightly further south (Figure 1), also required the river to have moved by this time (Redford Reference Redford1994: 28). As it shifted east, the former riverbank in the south may have become a marshy area favoured for waste disposal, shown by large amounts of bone, ceramic and mudbrick fragments within deposits included in Unit C in PC071 and PC072 (Figure 3b).

This eastern river channel was a substantial branch of the Nile, with its eastern terminal margin located east of AS114. During the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1076–664 BC), the channel had a width between 220 and 500m, suggesting that it was likely a major Nile branch during the earlier history of Karnak.

The main part of this channel finally silted up during or just after the Macedonian/Ptolemaic period, indicated by mixed New Kingdom–Macedonian/Ptolemaic period ceramics in cores AS169 and AS114 within fine-grained sediments reflecting waning flow. Core PC032, hosting mixed New Kingdom–Roman/Byzantine period ceramics (Roman/Byzantine period = 30 BC–AD 642) in similar sediments, likely represents the final residual channel, or perhaps a maintained canal, that silted up later still (Figure 4f). Two OSL dates from this core at 68.13–68.51masl (Peeters et al. Reference Peeters2024) confirm the dating of this residual channel infill as AD 470±140 years, based on a combined 68.27% probability from both dates. Afterwards, this area became part of the Nile’s east-bank floodplain.

Discussion: interconnected cultural and natural landscapes

As at other places in the Nile Valley (Hassan Reference Hassan1997; Pennington et al. Reference Pennington, Wilson, Sturt and Brown2020; Toonen et al. Reference Toonen, Cortebeeck, Hendrickx, Bader, Peeters and Willems2022), the natural riverine landscapes at Karnak appear strongly connected to cultural dynamics. They can be linked to the religious and cosmogonical views of the inhabitants, who also opportunistically adapted to changes in their physical environment.

In addition, the work provides dates for the earliest possible occupation of Karnak, which was constrained by the formation of the site’s original landscape setting: the river terrace underlying central/eastern Karnak. Fluvial deposition at this level ended after 2520 BC ±420 years; prior to this time the area was unsuitable for permanent occupation and construction.

Following fluvial deposition, subsequent channel incision took place to the east and west, creating the terrace-segment/island where occupation at Karnak began—in the south and east of the present site, and on the smaller ‘Opet terrace’ segment. Ascertaining exact dates is difficult, in part due to restrictions on taking samples from the site, but if all chronological indicators are taken into account then some conclusions can be drawn. The available chronological indicators are:

-

The OSL age of Unit T, reflecting active fluvial deposition of Karnak’s natural foundation (2520 BC ±420 years);

-

The earliest (late Old Kingdom–) First Intermediate Period ceramics atop the (post-incision) fluvial terrace (c. 2305–1980 BC);

-

First Intermediate Period ceramics in the surrounding river deposits (c. 2080–1980 BC);

-

Probable religious architecture during the First Intermediate Period reign of Intef II (c. 2066–2017 BC) (Hornung et al. Reference Hornung, Krauss and Warburton2006: 491; Ullmann Reference Ullmann, Dorman and Bryan2007: 4, fig. 2.2; Gabolde Reference Gabolde2018: 170–73); and

-

No significant soil formation at the top of the terrace, nor many aeolian deposits between Unit T and Unit E, both of which suggest little time elapsed between Unit T’s deposition and occupation at the site.

Taking all information together, it seems most likely that deposition of Unit T ended and subsequent incision took place at some point during the Old Kingdom (c. 2591–2152 BC), with occupation soon thereafter. A Predynastic or earlier origin for Karnak is therefore not viable.

The site itself, upon a raised terrace segment and forming an island, may have potent symbolism—a simple but striking example of site selection, connecting human action, the natural environment and religious views. The Pyramid Texts, from the late Old Kingdom, indicate that the creator god manifested as ‘high ground’ (Bickel Reference Bickel1994: 67–70). The texts further attest to the notion that land ‘came out’ or ‘emerged’ from ‘the lake’ (Popielska-Grzybowska Reference Popielska-Grzybowska2016: 162), although they do not at this time provide a clear connection between the ‘primeval mound’ and the ‘Waters of Chaos’ (Bickel Reference Bickel1994: 67–68; see below). The terrace segment upon which Karnak was founded is the only area of high ground surrounded by water thus far identified in the Theban area. No other topographic highs existed between this location and the western desert edge, and higher terrain further east was not surrounded by permanent watercourses (Peeters et al. Reference Peeters2024: 649). Although it is uncertain whether the Pyramid Texts were well-known in Thebes at this time, their references to Amun (Gabolde Reference Gabolde2018: 390–99), make this likely. As such, it is tempting to suggest that the Theban elites chose Karnak’s location for the dwelling place of a new form of Amun, ‘Ra-Amun’ (Ullmann Reference Ullmann, Dorman and Bryan2007: 4–6; Gabolde Reference Gabolde2018: 473–74), as it fitted the cosmogonical picture of high ground emerging from surrounding water (Gabolde Reference Gabolde2018: 201–3). Of course, caution must be heeded with such a link. The pragmatic location of Karnak on non-flooded land across from at-Tarif, a focus of Old Kingdom–First Intermediate Period activity (Arnold Reference Arnold1976; Gabolde Reference Gabolde2018: 96–97), may also have been a factor in site selection.

Nonetheless, the choice of location does foretell the later, more developed, Egyptian cosmogony. The Middle Kingdom Coffin Texts and later documents clearly develop the idea of high ground—the ‘primeval mound’—rising from the inundation, embodied as the Waters of Chaos/‘Nun’ (Bickel Reference Bickel1994: 29–31, 68–69). During the early Middle Kingdom, Karnak would have recreated this cosmogony each year: as the annual flood abated, the mound upon which Karnak was built would have appeared to rise from the receding water.

The illusion of Karnak rising from the inundation would also have been enhanced by a further aspect of the site’s geological configuration. A surface of early Middle Kingdom ceramics lying atop bar deposits in PC026, AS029 and PC048 (transect N) and PC045 and PC073 (transect S) (Figures 3 & 4a) indicate that an area of land 1m lower than the terrace top (at approximately 71masl) surrounded the terrace in the early Middle Kingdom. During flood conditions this level would have been inundated, since early Middle Kingdom levee deposits of Unit B lie directly above, while the top of the terrace remained dry. As the flood receded, the island could have doubled in area (Figure 4a) as the bar deposits ‘came out’ of the water, thus completing the impression of the upward movement of the mound. Seasonal activity would have been possible on the lower levels.

The occupants of the island were also opportunistic in adapting to changes in the local fluvial environment. The post-New Kingdom westward expansion of the temple (Bunbury et al. Reference Bunbury, Graham and Hunter2008: 351) demonstrates the progressive utilisation of new land, with the construction of the seventh to tenth and first to third pylons as the western channels silted up (Figure 4b–d). In some instances, changes to the landscape were made proactively, indicated by the dumping of desert sand into a channel just south of what was shortly to become the Hypostyle Hall (PC060).

Given that a large river channel originally lay to the east of the site, it would be instructive to consider further archaeological surveys in that area. Early archaeological features may be focused there, dating from before the eastern channel moved away and the western channel became a larger, more clearly-defined feature in the landscape (Figure 4a–e). A change of temple orientation from east to west based upon architectural evidence has even been proposed, with the earliest temple facing east (Larché Reference Larché2007: 481–83), though this remains contentious (Gabolde Reference Gabolde2018: 225–26).

Conclusion

New data from 61 sediment cores has allowed for a more detailed palaeogeographic reconstruction of evolving landscape settings at Karnak. Earliest possible occupation at the site is constrained probably to the Old Kingdom, and activity there demonstrates a coupling between the natural environment and the religious, functional and constructional aspects of the temple. Understanding the evolution of Karnak—from a small island to one of the defining institutions of Ancient Egypt—is thus possible only with advancing knowledge of its ever-changing environment.

Data availability statement

The summary geological data supporting the findings of this study are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11581016. Technical details of the sedimentary interpretation as well as detailed sedimentary figures, core metadata and ceramic chronostratigraphies are provided in the OSM.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, all at the Centre Franco-Égyptien d’Étude des Temples de Karnak (CFEETK) and at Chicago House (Luxor /University of Chicago), the Farouk family and our local team members. The research was carried out under the auspices of the Egypt Exploration Society (London).

Funding statement

The work was supported by the Knut och Alice Wallenbergs Stiftelse (KAW 2013.0163) and Uppsala Universitet (HUMSAM 2014/17) to A.G. as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2014–2020, together with a small grant from M och S Wångstedts Stiftelse (A.G.).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. The views expressed in the article do not necessarily represent the views of the National Park Service or the government of the USA.

Online supplementary material (OSM)

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10185 and select the supplementary materials tab.