Introduction

Since Mainwaring and Scully's (Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995) formative work on party systems in Latin America, the concept of party system institutionalization (PSI) – which refers to the stability and predictability in the set of parties in the party system and the patterns of competition between them – has been used to explain the performance and consolidation of democracies. Institutionalized party systems allow political actors to acquire information and develop more accurate expectations about who the parties are, what they prefer and how they might behave. Consequently, PSI has come to be regarded as critical to democracy as it facilitates representation and accountability, with less institutionalization linked to ineffective governance and democratic breakdown (Casal Bértoa & Enyedi, Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2021; Kim, Reference Kim2023; Mainwaring, Reference Mainwaring2018).

While the study of party systems has been a staple in the comparative analysis of democracies, the role that party systems play in authoritarian contexts has gone largely unexplored. This is not without reason, as interparty competition was non‐existent or irrelevant in many conventional authoritarian regimes. However, the rise of competitive authoritarian (CA) regimes engendered a novel type of party system in which a dominant ruling party ‘competes’ against opposition parties, albeit while enjoying significant structural and resource advantages. Elections in these regimes are fundamentally distinct from those typically observed in democracies as they do not offer a means to keep governments accountable, but instead establish an institutional channel through which incumbents can extend and legitimize their rule. Nonetheless, acknowledging that elections are biased in favour of the incumbent does not mean these elections and the accompanying party systems are meaningless. Indeed, the stakes involved in CA elections can be quite substantial – while democracies routinely survive significant turnover in their party systems,Footnote 1 a loss by the incumbents in a CA regime signals not just the potential for government turnover but also the possibility of regime change.

Our purpose is to assess whether PSI is valuable for understanding the durability of CA regimes.Footnote 2 An extensive body of research highlights the importance of elections for strengthening authoritarian rule (Levitsky & Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2010), but also demonstrates that such elections still carry varying degrees of uncertainty and can trigger authoritarian breakdown (Bernhard, Edgell & Lindberg, Reference Bernhard, Edgell and Lindberg2020; Knutsen et al., Reference Knutsen, Nygård and Wig2017). We argue that the institutionalization of the party system reflects the ruling party's ability to minimize such uncertainty by consolidating its dominance within the party system and pacifying opposition activity, which in turn enables the regime to ‘reap the fruits of electoral legitimacy without running the risks of democratic uncertainty’ (Schedler, Reference Schedler2002, p. 37).

To make our case, we develop unique measures of PSI for CA contexts by modifying Pedersen's (Reference Pedersen1979) index of electoral volatility, which is the standard measure of PSI in democracies. As in democracies, electoral volatility broadly captures the stability and predictability of the party system in CA regimes and thus reflects the extent to which ruling parties successfully minimize electoral uncertainty by managing interparty competition. On the other hand, and unlike in democracies, the ruling party is generally expected to win the election in CA regimes, which means that the electoral performance of the ruling party and opposition parties can have different ramifications for regime stability. To reflect this segmentation of the party system, we also disaggregate the system‐level measure into ruling party seat change and opposition party volatility. Furthermore, we break down opposition party volatility into Type‐A and Type‐B volatility (Powell & Tucker, Reference Powell and Tucker2014) – which, respectively, account for the entry and exit of opposition parties and shifts in the distribution of seats among repeat opposition contendersFootnote 3 – to better capture two of the three dimensions of Mainwaring's (Reference Mainwaring2018) more recent conceptualization of PSI: stability in the membership of the party system and stability in the seat shares of parties.Footnote 4 These modified volatility measures allow us to investigate how the interactions between different electoral dynamics within the ruling party and the opposition party sub‐systems matter for the survival of CA regimes.

We construct an original data set that covers 111 CA regimes across 79 countries from 1945 to 2018 and examine how these different types of electoral volatility condition pathways of regime failure in CA regimes. To our knowledge, this study presents the first large N cross‐national study that applies the concept of PSI to non‐democratic contexts. We find that CA breakdown – notably via democratization – becomes more likely when a deterioration of the ruling party's electoral standing coincides with disruptions in the competitive equilibrium that arise from the reapportionment of seats among repeat contenders, that is, opposition party Type‐B volatility. This runs counter to what is typical in democracies, where Type‐A volatility is considered to be more inimical to regime durability. These results indicate that PSI is not only important for understanding the fate of democratic regimes but can also have distinct implications in non‐democratic regimes. In sum, we show that the study of party systems in electoral authoritarian contexts warrants further attention.

The paper is organized as follows: in the next section, we review the existing literature on PSI in democracies before discussing the applicability of the concept to authoritarian contexts. In the third section, we develop hypotheses that link different types of electoral volatility with the durability of CA regimes. In the fourth section, we discuss our data, empirical strategy and results, and present our conclusions in the last section.

PSI across regimes

PSI in democracies

The notion of PSI grows out of classic work on the origins and viability of democracy. In their foundational study, Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967) argue that a series of political cleavages intrinsic to the emergence of modernity in Western Europe became frozen in the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries and continued to structure party competition for decades. The creation of durable and regular structures of interparty competition came to be regarded as characteristic of successful democratization, and subsequent studies of Western Europe seemed to confirm Lipset and Rokkan's theory of durable cleavages (e.g., Bartolini & Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair1990; Rose & Urwin, Reference Rose and Urwin1970).Footnote 5 This set expectations that party systems should become more institutionalized over time in democracies.

The historical patterns observed in Europe do not seem to hold for the rest of the world, however. Instead of early elections functioning as a ‘great electoral lottery’ (Innes, Reference Innes2002) that settles which parties become mainstays of an institutionalized system, the weeding‐out period has proven to be of longer duration or shown no signs of ever abating in many newer democracies (Bielasiak, Reference Bielasiak2005; Mainwaring & Zoco, Reference Mainwaring and Zoco2007).Footnote 6 These developments are troubling because under‐institutionalized party systems impair the smooth functioning of democracy (Kim, Reference Kim2023) by reducing accountability (Mainwaring & Scully, Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995; Sartori, Reference Sartori1976; Schleiter & Voznaya, Reference Schleiter and Voznaya2018), generating short‐lived governing coalitions that can make rule unpredictable and ineffective (Helmke, Reference Helmke2017; Hicken, Reference Hicken, Lancaster and van de Walle2018; Lupu & Stokes, Reference Lupu and Stokes2010; Mainwaring & Scully, Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995; Stokes, Reference Stokes2001) and undermining the exercise of horizontal constraints over poorly performing governments and those who try to overreach in their exercise of power. Democracies with weakly institutionalized parties have been shown to be more prone to breakdown (Bernhard et al., Reference Bernhard, Edgell and Lindberg2020), and the collapse of party systems has been identified as a central mechanism in some cases of democratic backsliding (Helmke, Reference Helmke2010, Reference Helmke2017; Morgan, Reference Morgan2011; Seawright, Reference Seawright2012). Ultimately, the failure to develop institutionalized party systems in democracies can produce unstructured polities in which policy is incoherent, government disorganized, governance ineffective and accountability weak, thus leading to endemic instability or democratic failure (Sartori, Reference Sartori1976).

PSI in authoritarian regimes

In contrast to democracies, there has been very little impetus to study PSI in authoritarian regimes since most conventional authoritarian regimes were either no‐party or one‐party regimes. No‐party authoritarian regimes are devoid of meaningful parties or interparty competition. In one‐party authoritarian regimes – which represent the most stable form of authoritarianism for most of the twentieth century (Geddes et al., Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018; Smith, Reference Smith2007) – the ruling party is the pre‐eminent political actor, and any minor parties that are permitted to exist are often fully licensed satellites subservient to the ruling party.Footnote 7 The essence of no‐party and one‐party regimes is a monopoly of political organization by the authoritarian incumbents (Przeworski, Reference Przeworski1991) or an absence or a highly constrained degree of opposition party subsystem autonomy (Sartori, Reference Sartori1976). The study of PSI is effectively meaningless in such contexts as there is no real interparty competition.

PSI in competitive authoritarian regimes

Over the last four decades, however, the share of authoritarian regimes that prohibit elections and opposition parties has decreased substantially. By the mid‐ to late‐1990s, the number of electoral authoritarian regimes surpassed that of conventional authoritarian regimes (Lührmann et al., Reference Lührmann, Tannenberg and Lindberg2018, pp. 67–77), and the discipline has wrestled with the rise of CA regimes that relax their monopoly over political organization and authorize some degree of electoral competition.

In CA regimes, opposition parties are permitted to compete against the ruling party and electoral results are generally dependent on the votes cast. However, interparty competition is constrained by the structural and resource advantages granted to the incumbent holders of state power and the range of manipulative strategies available to them, which can – if wielded effectively – shield incumbents from electoral punishment and diminish the probability that they cede power (Levitsky & Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2010; Schedler, Reference Schedler2002). A large number of authors argue that elections in CA regimes hold the key to maintaining credible commitments within the ruling authoritarian coalition (Boix & Svolik, Reference Boix and Svolik2013; Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2008; Svolik, Reference Svolik2012; Wright & Escribà‐Folch, Reference Wright and Escribà‐Folch2012), containing popular challenges to authoritarian rule by enabling those in power to co‐opt or disrupt counter‐elites who could lead popular challenges to incumbent authority (Arriola et al., Reference Arriola, Devaro and Meng2021; Gandhi & Przeworski, Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007; Lust‐Okar, Reference Lust‐Okar and Lindberg2009), granting concessions to important social constituencies to garner popular support (Greene, Reference Greene2010) and regularizing popular legitimation via electoral competition (Schedler, Reference Schedler2002).

Nonetheless, elections in CA regimes are not devoid of uncertainty and can be a double‐edged sword for ruling parties that can destabilize the regime (Bernhard, Edgell & Lindberg, Reference Bernhard, Edgell and Lindberg2020; Gandhi & Przeworski, Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007). For instance, elections can amplify the voices of disgruntled actors against ruling incumbents or facilitate the solution of collective action problems by the opposition (Knutsen et al., Reference Knutsen, Nygård and Wig2017; Tucker, Reference Tucker2007). Despite their best laid plans, incumbents in CA regimes can be surprised by election results and do, sometimes, lose elections.

In this spirit, we argue that the durability of CA regimes is a function of the ability of ruling parties to establish institutionalized party systems that minimize electoral uncertainty by reinforcing their dominance and taming the opposition in the electoral arena. Elections channel opposition activity into a formalized arena, which can provide ruling parties with information about the degree and sources of elite and mass support. Ruling parties can exploit such information to identify and appease key opposition actors via access to appointments and spoils or punish those who defect from or oppose the regime, which create perverse incentives for the opposition to participate in elections without truly challenging the ruling party to maintain good standing and the flow of benefits (Weghorst, Reference Weghorst2022). Such acquiescence through participation legitimizes the ruling party and simultaneously divides and demoralizes anti‐regime actors, thereby diminishing threats to the regime. As ruling parties establish an ‘autocratic collusive equilibrium’ (Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2010) by managing elites, opposition parties and larger groups within society through elections, the patterns of interparty competition observed in the electoral arena should become more stable and predictable, that is, institutionalized. This, in turn, should generate expectations that the status quo – which revolves around the ruling party – will persist into the future. Consequently, and contrary to democracies in which institutionalized party systems typically manifest in familiar sets of parties alternating in power, institutionalized party systems in CA regimes should correspond with an entrenchment of the ruling party.

Conversely, incumbents who preside over under‐institutionalized party systems face greater uncertainty over their own electoral performance and may well confront a more active and less predictable opposition. When ruling parties are unable to successfully consolidate their position within the party system and manage the opposition in the electoral arena, they may be forced to resort to higher levels of repression or more overt electoral manipulation to maintain power, but such measures can undermine their legitimation claims, galvanize the opposition and expose the fragility of their position.

Thus, the failure of ruling parties to develop institutionalized party systems can signal a heightened vulnerability of the regime. However, pathways of regime breakdown are more complex in CA regimes than in democracies (Geddes et al., Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014). Whereas democratic failure leads to authoritarianism, CA regime failure can result in a democratic transition or give rise to a new authoritarian regime seizing power – what we call ‘authoritarian replacement’. It is important to account for these different pathways as PSI may well have different ramifications for the two types of regime failure. More specifically, the institutionalization of the party system encapsulates both elite and mass support for the collusive equilibrium and thus can be expected to closely capture the propensity for democratic transition as this process typically involves both the elites and the masses. On the other hand, the concept may hold less relevance for authoritarian replacement, which is usually a product of ruptures within the incumbent camp (Svolik, Reference Svolik2012) that may not necessarily be channelled through the party system or elections. As a result, PSI may be a more useful concept for understanding pathways to democratic transition than authoritarian replacement in CA regimes.Footnote 8

In the next section, we propose a set of novel measures of electoral volatility that allow us to predict and assess the consequences of PSI in CA regimes.

Electoral volatility across regimes

Electoral volatility in democracies

Electoral volatility (Pedersen, Reference Pedersen1979) aggregates the movement of seats from party to party across electionsFootnote 9 and is a central measure of the stability and predictability of the party system.Footnote 10 This system‐level measure of volatility ranges from 0 to 100, with a value of 0 indicating no change in the composition of the legislature across two consecutive elections, and a value of 100 indicating that the composition of the legislature in election t is completely novel relative to election t−1.

Generally, institutionalized party systems are expected to exhibit low levels of volatility, whereas high levels of volatility are associated with under‐institutionalized party systems and pervasive uncertainty within the electoral arena. Powell and Tucker (Reference Powell and Tucker2014) also differentiate between Type‐A and Type‐B volatility, which both contribute to overall system‐level volatility but are driven by different dynamics. The former captures changes in seat shares resulting from the entry and exit of parties and thus reflects the stability in the set of parties that make up the party system. The latter summarizes the reallocation of seats between existing parties and is more closely associated with the stability of electoral support for repeat contenders. Type‐A volatility is thought to be potentially dangerous and destabilizing for democracies,Footnote 11 whereas Type‐B, when not excessive, is regarded as a reflection of the normal operation of vertical accountability wherein voters redistribute their support based on their satisfaction with the incumbent.

Electoral volatility in authoritarian regimes

Does electoral volatility convey any useful information in authoritarian contexts? Is it an indicator with any utility when interparty competition is less than fully competitive? To begin, there are three settings in which an application of electoral volatility would be nonsensical, superfluous or misleading. First, there are regimes in which there are no direct national elections or where political parties are not allowed (e.g., China). Second, there are regimes that hold elections in which only the ruling party is allowed to compete as a party (e.g., Vietnam). Finally, there are regimes in which electoral results have little relationship to underlying voter preferences as expressed through the ballot (e.g., cases with massive electoral fraud or those in which officials are not elected through popular elections).

Electoral volatility in competitive authoritarian regimes

On the other hand, we expect electoral volatility to be a useful indicator of PSI in CA contexts. Some might contest this point by arguing that electoral results in these regimes are endogenous to incumbent preferences and convey little else apart from the incumbent's strategic decisions over how much competition to allow, who will be allowed to vote and what strategies to employ to ensure the desired result. To accept this view, however, is to reject the assumptions of competitive authoritarianism as a concept and ignore the compelling evidence that the chance of incumbent loss is non‐negligible. Research has shown that these regimes can be both vulnerable and relatively fragile (Bernhard, Edgell & Lindberg, Reference Bernhard, Edgell and Lindberg2020; Bunce & Wolchik, Reference Bunce and Wolchik2011; Knutsen et al., Reference Knutsen, Nygård and Wig2017). Of the CA regimes sampled in this paper, almost two‐thirds come to an end. Thus, unless one is willing to assume that incumbents are more interested in losing than winning, then elections and the accompanying patterns of interparty competition should offer meaningful insight into the strength and durability of CA regimes.

But what specific information does electoral volatility provide about CA regimes? System‐level volatility reflects the overall stability and predictability of the party system and should broadly inform about the extent to which the ruling party is successfully managing the electoral arena. However, the measure is quite blunt as it conflates electoral dynamics concerning the ruling party and opposition parties, which can have distinct implications for the regime. To create more nuanced measures that allow us to investigate the consequences of more complex patterns of interparty competition, we partition the party system based on ruling party and opposition party status and calculate volatility measures for each sub‐system.

Party systems in CA regimes revolve around the ruling party, and changes in the ruling party's electoral performance can have more pronounced consequences for regime durability. As such, while conventional calculations of electoral volatility assess the magnitude of seat share changes by taking the absolute value, we note that such a calculation is less appropriate for ruling parties since both the magnitude and direction of changes in their seat shares matter for regime stability, for example, a 20 per cent decrease in the ruling party's seat share has very different implications compared to a 20 per cent increase. Thus, we create a measure of ruling party seat change (i.e., without taking the absolute value) to better account for potentially large swings in the ruling party's standing.

In turn, we calculate an opposition party volatility measure using Pedersen's index to capture the magnitude of instability in opposition party seat shares (i.e., excluding the ruling party).Footnote 12 Furthermore, we divide opposition volatility into Type‐A and Type‐B volatility to account for two different dynamics in the opposition party sub‐system: stability in its membership and stability in the seat shares of repeat contenders (Mainwaring, Reference Mainwaring2018).

Hypotheses

We build on our preceding discussion to develop hypotheses that link these volatility measures to the breakdown of CA regimes. Central to our argument is the idea that the ability of the ruling party to manage the party system is key for the durability of these regimes.

Our first hypothesis concerns general system‐level (i.e., Pedersen's) volatility. This measure may be noisy as it conflates electoral dynamics related to both the ruling party and opposition parties. Nonetheless, high levels of volatility across the party system indicate a general disruption in the status quo and that the ruling party has not sufficiently resolved the uncertainty in the electoral arena. This signals a heightened vulnerability of the regime, and thus we expect that this measure should be associated with regime breakdown.

H1: Higher system‐level electoral volatility should be associated with a higher risk of CA regime breakdown.

We also apply our disaggregated measures of electoral volatility to assess how more nuanced patterns of interparty competition within the ruling party and opposition party sub‐systems may matter for regime durability. In the case of the ruling party, decreases (increases) in the ruling party's seat share indicate a weakening (strengthening) of the ruling party, which in turn should lead to a higher (lower) risk of regime breakdown.

H2: Decreases in the ruling party's seat share should be positively associated with a higher risk of regime breakdown.

While the logic underlying the ramifications of the losses of seats by the ruling party is relatively straightforward, such losses only offer indirect information about the opposition party sub‐system, which still plays a key role in shaping the future of the regime. As such, we next turn to opposition party volatility, which directly accounts for instability in the seat shares held by opposition parties. From our theoretical perspective, low opposition volatility indicates that the opposition parties have been contained or sufficiently handicapped, leaving them with both less capacity and fewer incentives to challenge the status quo. On a popular level, it can also correspond with the satisfaction, resignation or apathy of voters. High opposition party volatility, on the other hand, indicates a disruption of the status quo. It can occur when opposition parties and their voters become dissatisfied with and seek to alter the present state of affairs by adopting new electoral strategies, such as choosing a new leader or coordinating with one another. Conversely, such volatility could also be a result of the ruling party attempting to co‐opt or divide the opposition or remaking the collusive bargain with a modified set of negotiating partners, perhaps to punish non‐compliant parties or remove weakened parties that may be less relevant for maintaining power.Footnote 13 Nonetheless, these disruptions – at least in the short term – change the relative bargaining positions of the opposition parties and the subsequent payouts that they could receive. This can empower opposition parties to assert greater influence or alternatively foster discontent, which generates uncertainty about how future interactions between the ruling party and opposition parties might play out. While we do not argue that such volatility by itself is sufficient to cause regime breakdown, it can increase the ability or incentives of opposition parties to contest the status quo, which should correspond with an increased probability of regime failure.

H3: Increases in opposition party volatility should be positively associated with a higher risk of regime breakdown.

Furthermore, opposition party Type‐A and Type‐B volatility represent different types of instability within the opposition party sub‐system and thus we apply our disaggregated measures to examine if either or both forms of instability might be particularly consequential for CA regimes. If Type‐A is significant, this would indicate that the ability of ruling parties to maintain stability in the membership of the opposition party sub‐system is important for regime durability. If Type‐B is significant, this would suggest that minimizing electoral uncertainty associated with repeat opposition contenders is critical.

H4a: Higher Type‐A opposition party volatility should be associated with a higher risk of regime breakdown.

H4b: Higher Type‐B opposition party volatility should be associated with a higher risk of regime breakdown.

Lastly, the preceding hypotheses are based on the premise that electoral volatility in the ruling party or opposition parties sphere offers useful information about PSI and the strength of CA regimes. However, since the party system encompasses the interactions between the ruling party and opposition parties, it may be the combination of specific patterns of ruling party seat change and opposition party volatility that portend regime failure. For example, volatility that is the product of a strengthening of the ruling party at the expense of the opposition does generate some uncertainty about how the opposition might react. Nonetheless, such a pattern is less likely to correspond with an increased risk of regime failure since it is in part a consequence of the ruling party expanding its control at the expense of the opposition. The inverse, however, could be a strong indicator of the kind of de‐institutionalization that could trigger regime breakdown. If the key to CA stability involves both the ruling party's ability to sustain its dominance within the party system and manage opposition parties, the combination of ruling party enfeeblement and significant disruptions in the opposition party sub‐system should have the strongest implications for the durability of the regime. For instance, a ruling party that performs poorly in elections will have reduced leverage to re‐establish a favourable collusive bargain, particularly given the shift in the balance of power, which can, in turn, undermine the ruling party's position.Footnote 14 As such, it may be the interaction between these types of instability within the ruling party and opposition party sub‐systems that are particularly consequential for regime durability.

H5: Increases in opposition party (Type‐A or Type‐B) volatility should be associated with a higher risk of regime breakdown when the ruling party concurrently loses seats.

Empirical analysis

Competitive authoritarian regimes

To test our hypotheses, we first construct a sample of CA regimes by using the Varieties of Democracy (V‐Dem) Regimes of the World variable (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg and Teorell2020) to identify electoral autocracies and then apply more stringent criteria to exclude electoral autocracies that are not CA. More specifically, we first limit our sample to non‐monarchicFootnote 15 regimes that hold minimally competitive multiparty elections with basic de jure provisions of suffrage.Footnote 16 We then further constrain our sample to regimes in which the ruling party wins a minimum of two consecutive elections that meet our baseline criteria since electoral volatility – and PSI in general – cannot be assessed given one time point. This produces a final sample that contains 111 ruling party regimesFootnote 17 and 372 elections across 79 countries from 1945 to 2018Footnote 18 for a total of 940 country‐year observations. This makes up less than 30 per cent of observations that are classified as electoral autocracies in the V‐Dem data set. An overview of the regimes is provided in the online Appendix A.

Dependent variable

We use two dependent variables and models in our analysis. We first estimate the conditional probability of CA regime breakdown using a logistic regression model. However, party system dynamics can have different consequences for the nature of regime failure in CA regimes. As such, we follow Geddes et al. (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014) and apply a trinary categorical coding scheme that indicates the survival of the ruling party regime, the displacement of the incumbent by another authoritarian regime (i.e., authoritarian replacement) or democratic transitionFootnote 19 and utilize a multinomial logistic regression model to assess whether different types of electoral volatility are associated with particular types of regime breakdown. We match the dependent variables with values of the independent variables from the preceding year.Footnote 20 Around two‐thirds of the CA regimes in our sample come to an end; there are 50 instances of authoritarian replacement and 24 instances of democratic transition.Footnote 21

Independent variables

We first calculate Pedersen's (Reference Pedersen1979) index of electoral volatility (EV) using seat share data from general lower house legislative elections.Footnote 22 We also further disaggregate this system‐level measure as we expect different types of electoral volatility to have distinct implications for ruling party survival. We calculate ruling party seat change (RPSC), which is simply the change in the ruling party seat share across two consecutive elections and can be positive or negative. Opposition party volatility (OPV) is calculated using the Pedersen index and the seat shares of all other parties (i.e., excluding ruling party seat shares). Moreover, we further break down opposition party volatility into Type‐A and Type‐B. Opposition party Type‐A volatility (OPV‐A) reflects changes in the distribution of opposition seat shares stemming from the entry and exit of opposition parties while opposition party Type‐B volatility (OPV‐B) represents shifts in the distribution of seats between existing opposition parties.

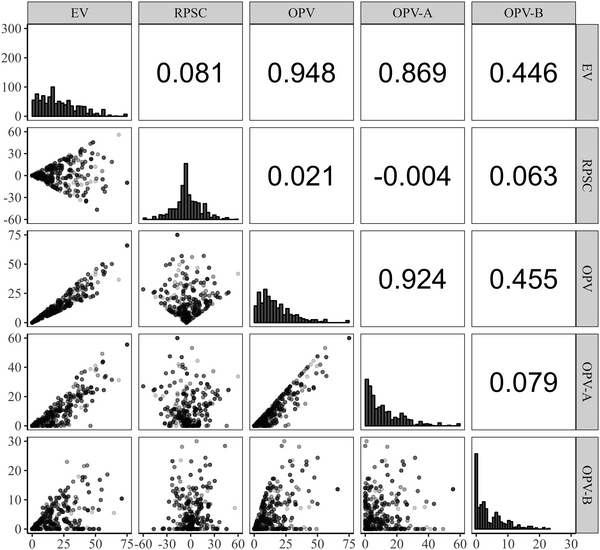

Figure 1 plots the different types of electoral volatility. As in democracies, degrees of electoral volatility vary widely across CA regimes. Changes in the ruling party's seat shares are centred around zero, which indicates that ruling party seat shares usually remain steady across elections. Furthermore, changes in opposition party volatility are generally of higher magnitude and tend to be driven by opposition party Type‐A volatility rather than Type‐B volatility. This is to be expected since opposition parties face significant electoral disadvantages and costs in CA regimes, which can undermine their ability to be consistently competitive across elections. Moreover, the lack of uniform trends in electoral dynamicsFootnote 23 across the different measures demonstrates that there is some uncertainty about how patterns of interparty competition might unfold in CA regimes.

Figure 1. Different types of electoral volatility: scatterplots, histograms and correlations. EV, electoral volatility; RPSC, ruling party seat change; OPV, opposition party volatility; OPV‐A, opposition party Type‐A volatility; OPV‐B, opposition party Type‐B volatility.

Control variables

We also control for a battery of other factors that may influence the durability of CA regimes. Ruling parties should be better situated to prolong their rule the longer they are in power and as they gain electoral experience (Bernhard, Edgell & Lindberg, Reference Bernhard, Edgell and Lindberg2020). We account for regime age and time dependence by including cubic polynomials of regime age in our models (Carter & Signorino, Reference Carter and Signorino2010).Footnote 24 On the other hand, a dissatisfied and determined opposition may well pursue extra‐institutional action against the regime when opportunities to contest elections become infrequent. Because this can affect regime stability, we include the variable Years since election, which counts the number of years that have passed since the last competitive multiparty election. We also include the effective number of parties (ENP) in our model since, ceteris paribus, the ruling party may find it easier to maintain its position as the dominant party when the party system is more fragmented. We use the log of ENP due to the variable's right skew.

Economic development and growth have been frequently linked to regime stability and are measured using a log of per capita GDP (GDP per capita) and per capita GDP growth rates (GDP growth), which are sourced from the Maddison Project (Bolt & van Zanden, Reference Bolt and van Zanden2020). Since state capacity dictates the ability of regimes to maintain control of the state apparatus, we include V‐Dem's estimate of the percentage of a state's territory over which the state has effective control (Territory control).

Extensive ethnic fractionalization can foster conflict (Easterly & Levine, Reference Easterly and Levine1997; Horowitz, Reference Horowitz1993), which can threaten regime stability. We calculate ethnic fractionalization scores (EF) using ethnic data from the Composition of Religious and Ethnic Groups (CREG) data set (Nardulli et al., Reference Nardulli, Wong, Singh, Peyton and Bajjalieh2012). Although the CREG data set is only available up to 2013, ethnic fractionalization changes very slowly over time. Thus, we use linear prediction based on all past scores to calculate scores for post‐2013 years. We substitute ethnic fractionalization scores calculated by Alesina et al. (Reference Alesina, Devleeschauwer, Easterly, Kurlat and Wacziarg2003) for the handful of countries that are not covered in the CREG data set. Nonetheless, we show that our results are robust to using observations from the original CREG data set, that is, without linear prediction and substitution.

We also include a variable from the V‐Dem data set that reflects the proportion of losing parties that accept the results of the national election within 3 months (Election accepted). Regardless of whether fraud was committed, the contesting of election outcomes signals opposition dissatisfaction with the electoral arena, which can weaken the ruling party's ability to control the opposition through elections. Furthermore, the presence of an active civil society through which citizens can collectively voice their demands should increase the impetus towards democratization (Bernhard & Edgell, Reference Bernhard, Edgell, Coppedge, Edgell, Knutsen and Lindberg2022; Bunce & Wolchik, Reference Bunce and Wolchik2011; Newton, Reference Newton2001), and so we also include a 5‐year moving average of V‐Dem's Civil Society Participation Index (Civil society). Lastly, we include the mean regional V‐Dem electoral democracy score (Regional polyarchy) to control for neighbourhood democratization effects, and a post‐Cold War (Post‐Cold War) dummy variable since electoral authoritarian regimes became much more commonplace during this period. The summary statistics for all variables used in our main models are presented in the online Appendix B.

Oil production per capita and district magnitude could also be included in our models since rent capacity can facilitate more effective co‐optation and repression, while modifications to the electoral system could mechanically alter the seat distribution between parties. Moreover, ‘Western leverage’ (Levitsky & Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2006) in the form of foreign aid may push authoritarian regimes towards democratization. However, the use of associated variables would force us to drop a significant number of our observations due to missing data. As such, while we do not include such variables in our main models, we show that our results are robust to their inclusion in the online appendix.

Results

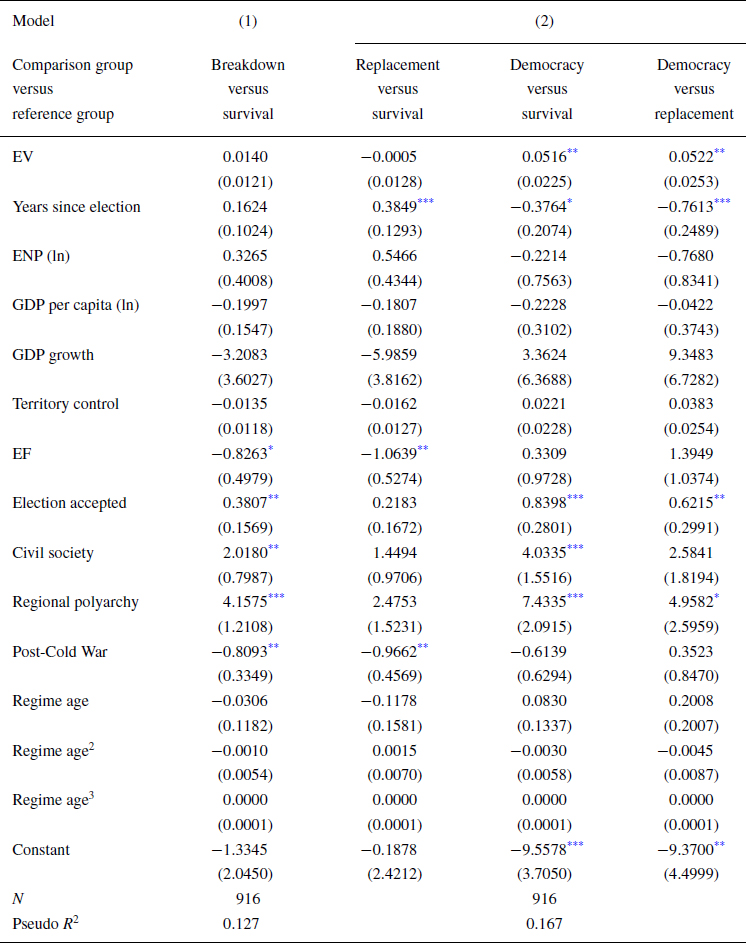

Table 1 presents the results of the logistic (Model 1) and multinomial logistic (Model 2) regressions using system‐level electoral volatility as the key independent variable. While the results of Model 1 indicate that system‐level electoral volatility shares a relatively weak association with regime breakdown in general,Footnote 25 Model 2 shows that this measure is a significant predictor of democratic transition in particular. This supports Hypothesis 1 and our proposition that the inability of the ruling party to minimize electoral uncertainty can be consequential for the durability of CA regimes. In subsequent models, we examine whether this association is driven by more specific patterns of electoral instability.

Table 1. Regime Breakdown and Electoral Volatility

Notes: Results report country‐clustered standard errors in the parentheses. Abbreviations: EV, electoral volatility; ENP, effective number of parties; EF, ethnic fractionalization scores.

* p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

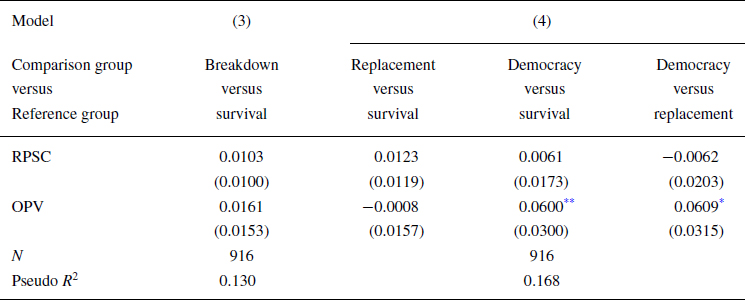

Table 2 replaces system‐level electoral volatility with ruling party seat change and opposition party volatility. In Table 3, we further disaggregate opposition party volatility into Type‐A and Type‐B to assess whether these different types of volatility have contrasting implications for CA regimes. Given that estimates of the control variables are generally similar across the board to those reported in Table 1, we present the full results including the control variables in online Appendix C.

Table 2. Regime Breakdown, Ruling Party Seat Change, and Opposition Party Volatility

Notes: Results report country‐clustered standard errors in the parentheses. Full results are presented in online Appendix C. Abbreviations: RPSC, ruling party seat change; OPV, opposition party volatility.

* p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Table 3. Regime Breakdown, Ruling Party Seat Change, and Opposition Party (Type‐A and Type‐B) Volatility

Notes: Results report country‐clustered standard errors in the parentheses. Full results are presented in online Appendix C. Abbreviations: RPSC, ruling party seat change; OPV‐A, opposition party Type‐A volatility; OPV‐B, opposition party Type‐B volatility.

* p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

In these tables, we do not observe an association between ruling party seat change and regime survival. This runs counter to Hypothesis 2, though this may be because the model does not account for the type of conditional relationship outlined in Hypothesis 5, which we test later.Footnote 26 On the other hand, Table 2 shows that opposition party volatility is associated with a greater risk of regime breakdown via democratization. This evidence is consistent with Hypothesis 3 and aligns with our argument that the ruling party's ability to manage the opposition party sub‐system appears to be an essential feature of PSI that connects it to the durability of CA regimes. Furthermore, and in accordance with Hypothesis 4b, Table 3 reveals that it is opposition party Type‐B volatility in particular that is associated with a higher likelihood of democratization.Footnote 27 Although opposition party Type‐A volatility is also estimated to have a similar association with democratization and achieves statistical significance in some of our models, robustness checks reveal that this result is sensitive to model specification or dropping influential cases. These results suggest that common understandings of electoral volatility in democracies that regard Type‐A volatility as being more detrimental to regime stability than Type‐B volatility are not reproduced in CA regimes, and the ruling party's ability to minimize electoral uncertainty among repeat opposition contenders appears to be more important for CA regime durability than its ability to regulate the entry and exit of opposition parties from the party system.

This discrepancy regarding opposition party Type‐A and Type‐B volatility may be due to differences in the types of parties that contribute to each type of volatility. Opposition party volatility generates uncertainty about how future interactions between the ruling party and opposition parties might play out and can incentivize opposition parties to contest the status quo. However, even in such cases, parties that are new, small or unable to remain competitive in elections – that is, those that typically contribute to Type‐A volatilityFootnote 28 – are unlikely to possess the infrastructure, resources or support to push for meaningful changes, which could in part explain why such volatility does not exhibit a robust association with regime durability in our models. Conversely, repeat opposition contenders – that is, those that contribute to Type‐B volatility – that consistently win seats across multiple elections despite facing electoral disadvantages are more likely to have the organizational capacity, electoral experience and political influence to pose a credible challenge against the regime. In other words, opposition party Type‐B volatility may share a more robust association with regime durability as it better reflects disruptions among key opposition actors who can play a more central role in shaping the future of the regime.Footnote 29

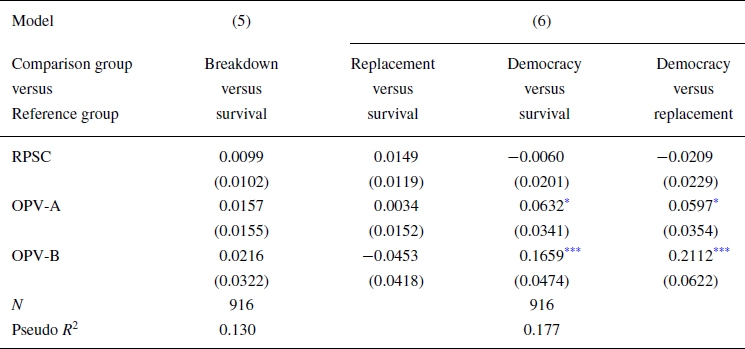

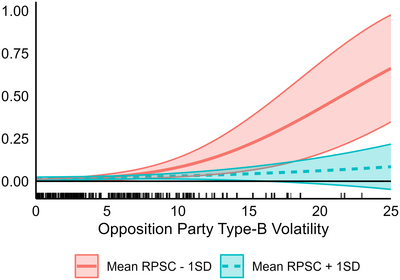

Nonetheless, in our discussion of Hypothesis 5, we noted that opposition party volatility may be more likely to lead to democratization when the ruling party concurrently suffers electoral setbacks. That is, regime durability may depend on what happens in both the ruling party and opposition party sub‐systems. Given the robust and significant results regarding opposition party Type‐B volatility, we estimate a model that interacts with this variable with ruling party seat change to test such a dynamic.Footnote 30 Estimates of the coefficients of interest are presented in Table 4. To facilitate interpretations of the interaction, we plot the predicted probability of democratic transition along with 90 per cent confidence intervals across the range of observed OPV‐B values when RPSC is held at ±1 standard deviation (SD) from its mean value (approximately −13 and 16), and other variables are held their means. The plot is shown in Figure 2.

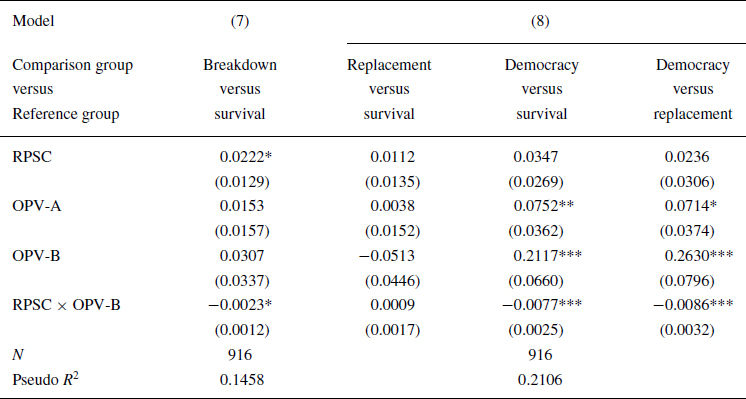

Table 4. Regime Breakdown and the Interaction between Ruling Party Seat Change and Opposition Party Type‐B Volatility

Note: Results report country‐clustered standard errors in the parentheses. Full results are presented in online Appendix C. Abbreviations: RPSC, ruling party seat change; OPV‐A, opposition party Type‐A volatility; OPV‐B, opposition party Type‐B volatility.

* p < 0.10; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

Figure 2. Predicted probability of democratization. RPSC, ruling party seat change; SD, standard deviation of RPSC.

The figure shows that the likelihood of democratic transition is largely unaffected by increase in opposition party Type‐B volatility when the ruling party improves on its past electoral performance, which is intuitive since the latter indicates a strengthening of the ruling party's position at the expense of opposition parties. However, when the ruling party loses a relatively significant share of seats and opposition party Type‐B volatility begins to exceed its mean value (4.11), the predicted probability of regime breakdown via democratization begins to grow substantially. At its maximum value in our sample (22.95), the predicted probability of democratic transition becomes quite large (around 0.56). That is, opposition party Type‐B volatility appears to be particularly inimical for prospects of CA survival when the ruling party is relatively weakened.

Robustness checks

We conduct an assortment of robustness checks to mitigate issues that could undermine our results. For parsimony, we focus on Models 7 and 8 presented in Table 4, and specifically on the coefficient estimates of RPSC, OPV‐B and their interaction given that they are the strongest predictors of regime failure.

In online Appendix E, we include oil production per capita as a measure of rent capacity using data from Ross and Mahdavi (Reference Ross and Madhavi2015) supplemented by Wimmer and Min (Reference Wimmer and Min2006), although this reduces our sample by 129 observations. In online Appendix F, we include changes in district magnitude across elections using data from the Database of Political Institutions (Cruz et al., Reference Cruz, Keefer and Scartascini2018) since electoral volatility may also be driven by institutional changes. This causes us to lose around a third of our observations. In online Appendix G, we account for the level of Official Development Assistance – a form of foreign aid typically provided by developed democracies – received by CA regimes as a proxy for external pressure to democratize, that is, the degree of ‘Western leverage’ (Levitsky & Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2006). The data are available from the OECD (2021), though only from 1960 onwards and thus we lose 108 observations from our sample. In online Appendix H, we use the original ethnic fractionalization scores calculated from the CREG data set, that is, without linear prediction and substitution. This drops around a fifth of our observations. In online Appendix I, we drop right‐censored regimes, which leaves us with around 60 per cent of our sample. As shown in the appendices, the empirical patterns between RPSC, OPV‐B and the probability of democratization observed in the main results remain consistent across all models.

Adding all these variables to our model and using the original ethnic fractionalization scores would cause us to lose more than half of our sample. As such, we re‐estimate this full model after using Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations to impute missing values based on observed values of our variables. We impute 10 complete data sets and present the pooled estimates in online Appendix J. The results remain robust.

There may also be concerns that our results could be driven by a single influential regime. To address this point, we re‐estimate Model 8 in Table 4 dropping one country at a time. This presents a more challenging test of robustness since multiple regimes may be dropped when a country is excluded from the sample. As shown in online Appendix K, our results are not driven by one influential case.

In online Appendix L, we re‐estimate Table 4 after including V‐Dem's party institutionalization (PI) Index, which measures average levels of party institutionalization across the main parties in the party system (Bizzaro et al., Reference Bizzaro, Hicken and Self2017). Our main results hold while the PI index is estimated to have little association with regime durability. This lends support to our claim that the patterns of interparty competition between the ruling party and opposition parties, that is, the party system, can be an important unit of analysis for understanding regime‐level outcomes in CA contexts.

Lastly, in online Appendix M, we also replace the dependent variable with V‐Dem's electoral democracy index to examine changes in a continuous measure of democracy and estimate the model using ordinary least squares with panel‐corrected standard errors. To summarize, the estimated marginal effect of OPV‐B becomes increasingly positive and statistically significant (i.e., associated with higher levels of democracy) as the ruling party loses seats, but becomes generally negligible when the ruling party gains seats. This corroborates the main finding that CA regimes may be more likely to undergo democratization when ruling parties are weakened and levels of opposition party Type‐B volatility are particularly high.

Conclusion

The eclipse of conventional authoritarian regimes by competitive authoritarianism requires us to re‐examine our democracy‐based expectations of parties and party systems in light of the logic of these new forms of rule. The literature argues that the holding of elections is a strategic move designed to enhance the viability of authoritarianism in the face of domestic demand and international pressure for democratization. While the empirical evidence in support of such arguments is mixed, we argue that the success of CA regimes depends crucially on the ability of ruling parties to legitimize and extend their rule by effectively managing elections and the opposition. Rather than focusing on whether competitive elections in themselves fortify or undermine authoritarian rule, we explain CA regime durability as a product of the capacity of the authoritarian incumbent to resolve electoral uncertainty by establishing an institutionalized party system.

To test our claim, we explore the relationship between electoral volatility and the durability of CA regimes and find that it is positively associated with an increased risk of regime breakdown but specifically through democratic transition rather than authoritarian replacement. Moreover, because elections in CA regimes revolve around the ruling party, they follow a different logic than elections in democracies. We capture the specificities of electoral competition under authoritarianism by disaggregating the system‐level electoral volatility measure, and the subsequent analyses offer more nuanced insights into how varied patterns of interparty competition could be associated with regime breakdown. We find robust results that democratic transition becomes more likely when decreases in the ruling party's seat share coincide with an increase in opposition party Type‐B volatility. This pattern contrasts with those observed in democracies where Type‐A volatility is considered to be more dangerous for regime durability. In addition, measures of electoral volatility tend to be noisy (Casal Bértoa et al., Reference Casal Bértoa, Deegan‐Krause and Haughton2017), which can weaken empirical associations. The fact that our analyses identify significant and robust results lends evidence to our argument that electoral outcomes and the party system do provide meaningful information about the survival and breakdown of CA regimes.

We show that the ability of the incumbent to manage elections holds one of the keys to success or failure, and this paper demonstrates that an increased focus on the institutionalization of party systems in authoritarian contexts is warranted. Furthermore, our findings on regime breakdown seem to be driven by democratization rather than authoritarian replacement. This corroborates existing arguments that elections can pave the way towards democratization in CA regimes and suggests that the conditions under which authoritarian replacement occurs may be less contingent on the electoral sphere, which requires additional exploration.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Scott Mainwaring, Ekrem Karakoç, and the late Keith Weghorst for their comments on the original draft of the manuscript. We also want to thank the participants of the American Political Science Association 2020 Annual Meeting; Politics Colloquium at the University of Oxford, England; the unit on Politische Verantwortlichkeit und Partizipation at the Leibniz‐Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien, Hamburg, Germany; and the Research Seminar on Politics at the University of Florida, United States, for their supportive and constructive suggestions at presentations of our findings. Michael Bernhard's work on the article was supported by the University of Florida Foundation.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information