Introduction

Venezuela has been subject to sanctions from the US since 2006. While the EU, Canada, and some Latin American countries have also imposed sanctions on Venezuela, in this chapter, our focus will be those imposed by the US. An arms embargo was introduced in 2006, and over the subsequent years individuals loyal to the government first of Hugo Chávez, then Nicolás Maduro were targeted with individual sanctions. These sanctions had limited effect on the goals they were established to achieve, ranging from improving the human rights situation to creating a wedge in the governing coalition and forcing democratization of the political regime. They also had limited consequences for the Venezuelan economy. However, the August 2017 Executive Order that prohibits access to US financial markets by the Venezuelan government marked the start of a series of Executive Orders issued by the US introducing sectoral restrictions targeting finance, oil, gold, and government transactions. Although they are all “targeted” in theory, taken together, these sanctions amount to what is defined as comprehensive sanctions.

The main debates related to the sanctions against Venezuela have centered on the extent to which they have contributed to their stated goals, and what consequences they have had for the economy and humanitarian situation. What is clear is that between 2017 and 2024, sanctions failed to achieve their stated goal of weakening the regime of Nicolás Maduro.Footnote 1 To the contrary, Nicolás Maduro consolidated his power after sanctions were imposed, despite his dwindling popular support.

Following the literature on sanctions, it is no surprise that the sanctions have failed in reaching the goal of regime change. Sanctions rarely succeed in encouraging a shift from an authoritarian to a democratic regime,Footnote 2 and any sanctions will be more likely to succeed when they are multilateral and used strategically associated with negotiations.Footnote 3 In Venezuela, none of these conditions were present when the sanctions were first imposed. A less developed part of the literature looks at when and why sanctions have negative effects.Footnote 4 Yet, many case studies demonstrate the unintended effects of sanctions on targeted countries. Gordon has shown that sanctions have produced dire effects on the Cuban economy despite being ineffective in bringing regime change.Footnote 5 Iran is another case where sanctions have generated economic costs and social repercussions.Footnote 6

In this chapter, we seek to contribute to this literature, by first briefly reviewing the sanctions against Venezuela. We then review the existing literature on the impact of the sanctions against Venezuela. Here we first discuss the different arguments about the economic impact of the sanctions. We then discuss the impact of the sanctions on the humanitarian situation, and subsequently, how the dynamic interaction between governmental policies and measures and sanctions have forced businesses in different sectors to apply strategies that in sum have led to an informalization of the economy and the emergence of new business elites. We argue that by weakening the private sector, sanctions have hurt the potential allies of the democratization agenda and contributed to the fragmentation of the social and political coalition that opposes the government. Thus, they have contributed to divisions within the opposition, rather than to the collapse of the Maduro regime. These issues are the focus of the final section before we draw implications of the Venezuelan case for the literature on sanctions. The chapter is based on a thorough review of the literature and secondary sources, as well as around fifty interviews with business representatives in Venezuela in five separate periods between 2017 and 2024.

The Sanctions against Venezuela: How Targeted Sanctions Become Comprehensive

The first sanctions imposed by the US on Venezuela were introduced as a crackdown on lack of compliance with US policies regarding drug trafficking, terrorism, and human trafficking. Between 2006 and 2014, obstacles to arms purchases and shame-listing Venezuela for not cooperating with US-led anti-narcotics, human trafficking, and anti-terrorism efforts comprised the bulk of US sanctions.

In 2014, a wave of protests dubbed “the exit” ended with state repression. As a response, in December 2014, the U.S. Congress enacted the Venezuela Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society Act of 2014.Footnote 7 Among its provisions, the law requires the President of the United States to impose sanctions (asset blocking and visa restrictions) against those whom the President determines are responsible for significant acts of violence or serious human rights abuses associated with the protests or, more broadly, against anyone who has directed or ordered the arrest or prosecution of a person primarily because of the person’s legitimate exercise of freedom of expression or assembly. In 2016, Congress extended the 2014 Act through 2019 in Pub. L. No. 114-194. In March 2015, President Barack Obama issued Executive Order 13692 to implement Pub. L. No. 113-278, and the Treasury Department issued regulations in July 2015.Footnote 8 The Executive Order targets (for asset blocking and visa restrictions) those involved in actions or policies undermining democratic processes or institutions; violence or serious human rights abuse; prohibiting, limiting, or penalizing the exercise of freedom of expression or peaceful assembly, or engage in corruption.

In 2017, protests escalated with the government’s attempt to shut down the National Assembly. The protests were crushed with violent repression from state and para-state groups and the government’s decision to convene a National Constituent Assembly (NCA), capable of overriding the power of any other public power. Sanctions continued to expand amid the harsh repression and the election of the NCA.

Starting in August 2017, President Donald Trump imposed broader financial sanctions on Venezuela through three additional Executive Orders: E.O. 13808 (August 6, 2019), which restricts the Venezuelan government’s access to US bond and equity markets; E.O. 13827 (May 19, 2018), which prohibits transactions involving the Venezuelan government’s issuance and use of digital currency; and E.O. 13835 (May 21, 2018), which expands E.O. 13808 to include all transactions of with debt, including secondary sales, seeking to avoid any form of debt-rescheduling. After the first financial sanctions, the government convened a round of dialogue in the Dominican Republic, with the support of Danilo Medina’s government and ministers of foreign affairs from governments of the region. The government’s goal was to force a National Assembly call to ease or end the sanctions.Footnote 9 Among the priorities of Maduro’s economic policies at the time was an attempt to reschedule the debt, something that required first the lifting of financial sanctions.

The opposition’s representative sought a set of minimal conditions to secure their participation in the elections of 2018. In addition, the institutional normalization of the National Assembly, freeing of political prisoners, and dismantling of the NCA were part of the opposition’s demands. The Dominican Republic dialogue ended in no agreement. Instead, the NCA called for presidential elections for May 2018, as opposed to December when they are normally held, with no change in the conditions of the electoral process. The call for anticipated presidential elections is the background of the following standstill, in which Nicolas Maduro’s term was not recognized by most democracies, nor by the 2015 National Assembly.

On November 1, 2018, President Trump issued E.O. 13850, setting forth a framework to block the assets of, and prohibit certain transactions with, any person determined by the Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the Secretary of State, to operate in the Venezuelan gold sector (or any other sector of the economy as determined in the future by the Secretary of the Treasury) or to be responsible or complicit in transactions involving deceptive practices or corruption. On January 28, 2019, pursuant to E.O. 13850, the U.S. Treasury Department’s OFAC designated PDVSA, Venezuela’s state-owned petroleum and natural gas company, as subject to US sanctions. As a result, all property and interests in property of PDVSA subject to US jurisdiction were blocked, and US persons were prohibited from engaging in transactions with the company. In essence, the Maduro government was blocked from accessing the accounts of PDVSA’s main asset in the US, Citgo.

At the same time, OFAC issued general licenses to allow certain transactions and activities related to PDVSA and its subsidiaries, some within specified time frames or wind-down periods.

The PDVSA sanctions were imposed after the president of the National Assembly, Juan Guaidó, declared he was the interim president of Venezuela on January 20, which came as a rejection of the May 2018 election. The explicit goal was to drive a wedge into the government coalition, hoping to produce sufficient defection, particularly among the military, to shift power to Guaidó. The Guaidó-led opposition announced in May 2019 that it was negotiating with the Maduro government for a political solution, mediated by Norway. Yet, on August 5, 2019, President Trump signed E.O. 13884, blocking any property of the Venezuelan government in the US. It also subjected to sanctions any person who has materially assisted, sponsored, or provided financial, material, or technological support for, or goods or services to or in support of, any person involved with the Venezuelan government and all its entities. This led to the immediate withdrawal of the Maduro government from the table, and by September the same year, the opposition formally withdrew.

At the same time as E.O. 13884 was enacted, general licenses 4c was signed. This allows for the exemption from E.O. 13884 and previous Executive Orders for the exports of medicines and in order to mitigate the humanitarian effects of the sanctions. Italy’s Eni, Spain’s Repsol, India’s Reliance Industries, and Thailand’s Tipco Asphalt received oil in return for diesel, based on a quiet clearance with the OFAC. At the end of 2020, OFAC changed its attitude and started to consider these swaps as a break of the sanctions regime. In other words, US law enforcement gradually tightened the measures through sanctioning not only companies directly involved with the Venezuelan government, oil or gold sectors, but also subsidiaries of those companies. However, after the Joe Biden administration took over in 2021, the US also started to actively support political negotiations between the opposition coalition, the Unitary Platform, and the Maduro government. These negotiations have been facilitated by Norway and have taken place in Barbados and Mexico from the fall of 2021. Two partial agreements were signed. The last of these, signed in Barbados in October 2023, included clear conditions for free and fair presidential elections in 2024. The US negotiated in parallel with Maduro and announced the subsequent day, a six-month suspension of all sectoral sanctions, conditioned on progress in implementing the Barbados-accord. When those conditions were not fulfilled, given continued repression and a ban on the most popular opposition candidate, Maria Corina Machado, sanctions were reimposed in April 2023. After the presidential election of July 28 ended in a clear and well-documented fraud,Footnote 10 giving Maduro the victory, hope dwindled of any sanctions relief. However, several licenses were given to oil companies, most notably US-based Chevron, allowing for continued and increasing oil production.

The Impact of Sanctions on the Economy

There is little agreement in the literature about the economic impact of the sanctions. This is partly due to several methodological problems with distinguishing between the impact of the policies and events leading to the pre-existing crisis, and the additional limitations resulting from the sanctions.

Among the main contributors to the debate (including Rodríguez,Footnote 11 Weisbrot and Sachs,Footnote 12 Hausmann and Muci,Footnote 13 Bahar et al.,Footnote 14 Oliveros,Footnote 15 and SutherlandFootnote 16), there is a consensus regarding the fact that Venezuela was already in a deep economic crisis when the first sector sanctions – the financial sanctions – were introduced in August 2017. By then, the Venezuelan economy had been through fourteen trimesters of consecutive economic contraction; inflation was about to reach levels of hyperinflation, imports had been reduced by almost 70 percent since the peak in 2013 (see Figure 16.1) and Venezuela had already lost access to many financial markets.Footnote 17

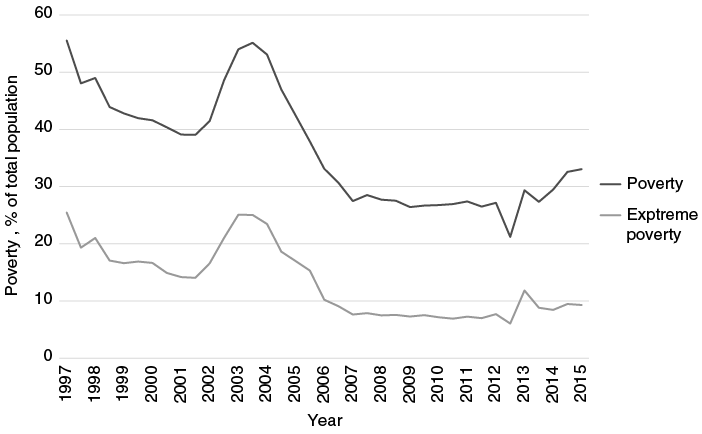

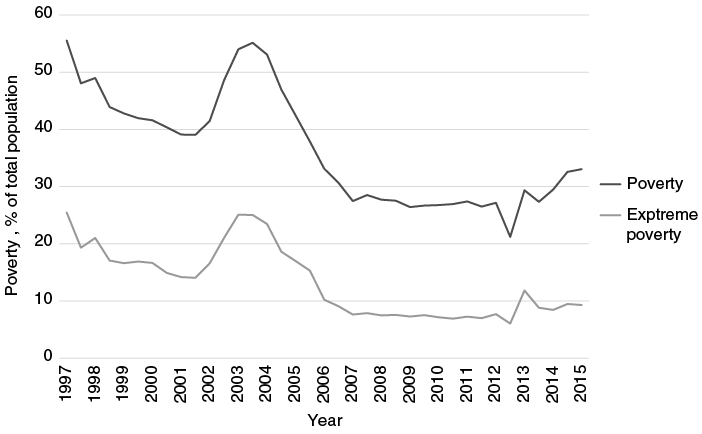

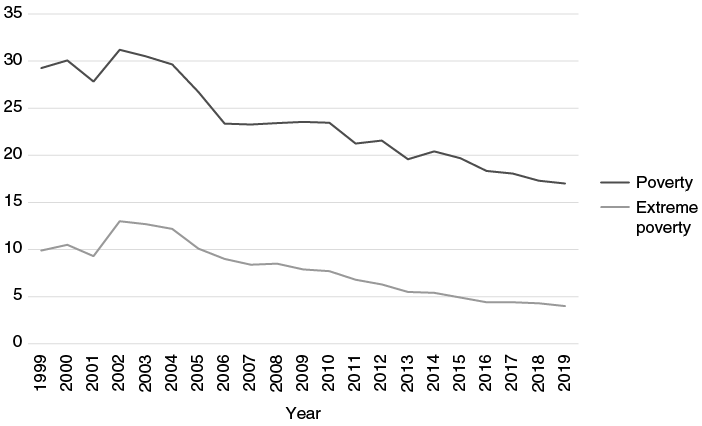

Figure 16.1 Monetary poverty according to the National Statistics Institute.

There is also little disagreement about the fact that the steep drop in oil prices at the end of 2014, and the further slump in 2016, led to an acceleration of the reduction in economic growth that had started even before the oil-price drop. While 2013 and 2014 saw relatively moderate contractions, as oil prices hit a $38 low in 2016, the economy contracted by nearly 15 percent, the negative growth rates continued into 2017 and 2018. While there is no official information about 2019 and 2020, the total contraction between 2014 and 2020 was calculated to be over 80 percent.Footnote 18 As Rodríguez emphasized, the drop in oil income was the single most important reason for the worsening of the economic crisis.Footnote 19

There is also little disagreement that the Chávez and Maduro governments bear the brunt of the general responsibility for the long-term crisis, due to their failure to reduce Venezuelan oil dependency, overspending and indebtedness during the boom years, mismanagement of the oil sector, and introducing a currency regime and monetary policies that contributed to inflation. The use of ground rents to subsidize dollars encouraged an import-dependent industry as well as high domestic consumption of end products.Footnote 20 However, there is less consensus about the reasons for the worsening of the crisis after 2016.

One question is why the oil production failed to stabilize or recover after the 2014 and 2016 oil price drops. Venezuelan oil production had been on a downward trend since 1998. It was then at 3.5 million barrels a day (b/d) but had dropped to 2.7 million b/d by 2013. Nevertheless, there is relative agreement that the subsequent drop in oil prices contributed to the steep contraction in oil production starting in 2015. However, while oil production dropped in most oil-producing countries (including neighboring Colombia) during the oil-price slump, in most other countries, production recovered relatively rapidly. Venezuela, in contrast, reported production of 2.1 million b/d to OPEC in mid 2017. However, since then, the production fell even more steeply. By January 2019, when sanctions banned all oil trade in Venezuela, production had dropped to 1.1 million b/d and by mid 2020 to below 0.4 million b/d.Footnote 21

Rodríguez (2018) was the first to relate the failure to stabilize oil production to financial sanctions. His argument was that while many oil companies had incurred debt due to the oil-price drops, PDVSA was restrained from rescheduling its debt, and was thus unable to recover production. This led to a continued decline in GDP. This was corroborated by Weisbrot and Sachs (2019), which linked the GDP decline directly to the worsening of the humanitarian situation. However, they have been criticized on many accounts. Hausmann and Muci rejected the usefulness of comparing Venezuela with Colombia, due to the number of additional differences between the two countries.Footnote 22 Bahar et al. focused on a series of changes to the Venezuelan oil industry starting with Hugo Chávez, the sacking of 18,000 oil workers in 2001, and continuing with the militarization and draining of the company of expertise that disabled it from implementing the strategies needed to recover.Footnote 23 Moreover, they argued that it was not the financial sanctions that primarily cut off Venezuela from access to global finance, as the Venezuelan sovereign spread (the premium that bondholders demand the country pay over the so-called “risk-free” rate) had been 7.8 times the spread paid by the rest of Latin America before the sanctions hit. Venezuela was, in other words, basically cut off from financial markets already before the sanctions hit.

In his rebuttal, Rodríguez estimated whether sanctioned companies fared better or worse than those not affected by sanctions (joint ventures with Russian and Chinese companies). He found that oil output from joint ventures with Russian and Chinese firms, which were much less affected by sanctions and financial “toxification” than the US-related companies, remained stable and even grew as the remainder of Venezuelan oil production was collapsing.Footnote 24

Sutherland, on the other hand, underlines the lack of necessary connection between sanctions and inflation by pointing to comparable sanctions episodes in Russia and Iran that have not led to anywhere close to the same inflation rates.Footnote 25 Thus, at best, sanctions are a factor that has contributed to a deepening of the conditions that lead to hyperinflation in a particular context of an economy already prone to inflation.

One may conclude that there is little agreement about the overall impact of sanctions on the Venezuelan economy. Yet it is likely that the 2017 financial sanctions are partly responsible for the lack of recuperation of oil production after the 2014–2016 drop in prices with its associated drop in GDP. The impact has probably been even more pronounced after the introduction of sanctions against oil trading in 2019. While these macroeconomic issues are clearly related to both how the micro-functioning of the economy, and the humanitarian situation, these are influenced also by the strategy of the government and private actors to confront them.

Sanctions and the Humanitarian Situation

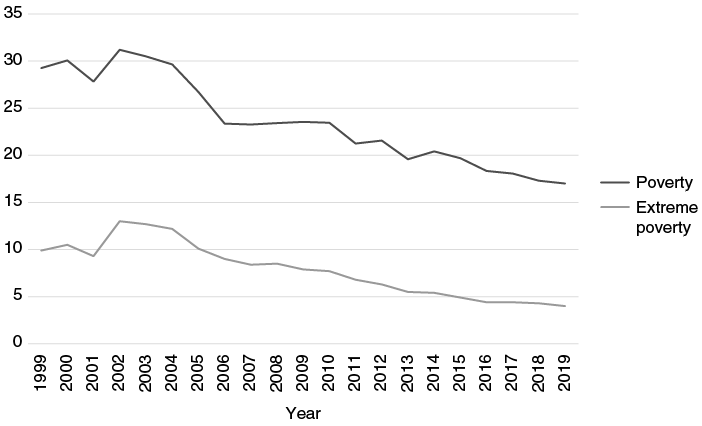

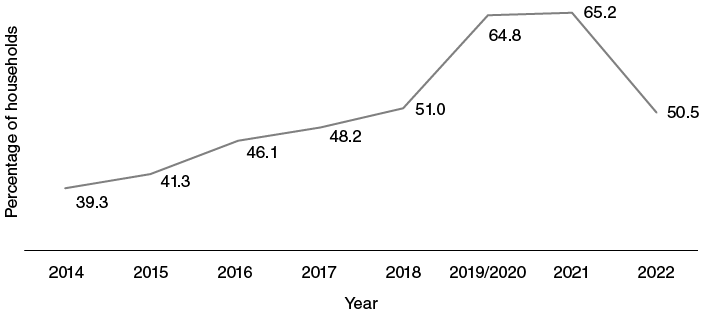

The most pressing and hotly debated possible consequence of sanctions is, of course, their impact on poverty and the humanitarian situation. There are scant official data for the period after 2015. However, as shown in Figure 16.1, the official measure of monetary poverty (population below national poverty lines) data shows a steep decline in poverty starting in 2003. Monetary poverty reaches its lowest level in 2012, and then starts to climb, despite continued increase in oil income and imports until 2014. For data on monetary poverty after 2015, we need to lean on a consortium of universities in Venezuela that conducted broad surveys of living conditions since the 1970s, but intensified after INE stopped publishing data, the ENCOVI survey. As shown in Figure 16.2, according to ENCOVI data, a steep upsurge in poverty was recorded since the start of the survey in 2014. Income poverty levels are directly affected by inflation, leading to a decline in real wages. Between 2013 and 2020, the real minimum wage declined by 94 percent, mainly because of inflation.Footnote 26 However, we see no major change in poverty trends in 2017 when the financial sanctions were introduced. Rather, we see a continued steep upsurge in poverty that starts in 2014.

Figure 16.2 Monetary poverty according to ENCOVI.

The picture is somewhat different regarding multidimensional poverty, including access to food, housing, and public services. The official data on this, collected by INE, show a decline in multidimensional poverty that starts in 2001, and continues until the last survey collected in 2019 (Figure 16.3). This is in stark contrast to the numbers collected by ENCOVI and other sources. It also contradicts other macroeconomic indicators, most importantly, a drastic contraction in GDP from 2013 until 2020.

Figure 16.3 Multidimensional poverty (Necesidades Básicas Insatisfechas [NBI, Unmet Basic Needs] indicators), National Statistics Institute.

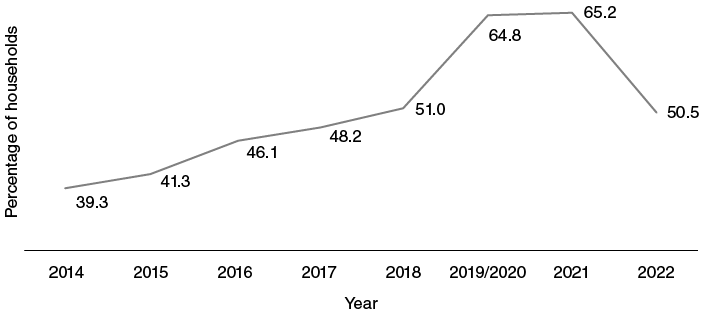

Unlike the official data, ENCOVI data show a gradual increase of multidimensional poverty between 2014 and 2022 with the most distinct jump taking place in 2018, which coincides with the imposition of financial sanctions (Figure 16.4). Moreover, the number of respondents reporting lack of sufficient funds to access food jumped from 80 percent in 2014 to 93.5 percent in 2016. After that it declined moderately in 2017, probably explained by introduction of the government food program Comité Local de Abastecimiento y Producción (Local Supply and Production Committees, CLAPs) in 2016. In other words, the decline in ability to buy food was unrelated to the financial sanctions that were introduced in 2017. By 2017, 6.7 million people were dependent on receiving the CLAP boxes containing basic food items. This contributes to explaining another finding: Venezuelans depend increasingly on governmental support and other noncash transfers from employers or other private individuals, mostly the diaspora of Venezuelan migrants, who coincidentally were leaving the country en masse to avoid these conditions.

Figure 16.4 Multidimensional poverty (ENCOVI), percentage of population.

Various data collected by Caritas show a rapid deterioration of the nutrition and general humanitarian situation. Chronic malnutrition increased from affecting 24.7 percent of children in 2017 to 35.1 percent in 2019.Footnote 27 Nevertheless, the longer curves that exist show a continuity in the worsening of the humanitarian situation, rather than any clear break in 2017. Venezuela imports more than 90 percent of its medicines and 75 percent of its food.Footnote 28 Thus, it is highly likely that the humanitarian situation is affected by the drop in imports. An overview over public and private import shows that both fall drastically after peaking in 2013. The steepest drop occurs between 2013 and 2016.

Venezuela has also seen as steep deterioration of public services. An April 2020 report by the Venezuelan Observatory of Public Services (OVSP) revealed that only 16.7 percent of Venezuelan households receive water on a continuous basis. In February 2020, according to the World Food Program, four out of ten households suffer daily electricity outages and 72 percent have an irregular gas supply.Footnote 29 Once again, whereas it is easy to establish that there has been a worsening of the situation, most represent a continuation of a trend that started before the 2017 sanctions.

The same is true for the health situation. Mortality by disease has increased significantly, but it is difficult to connect that directly with sanctions. A 2019 article in The Lancet shows, for example, a strong increase in mortality from different diseases starting in 2013. The cases of TB increased by 68 percent between 2014 and 2017, and the HIV cases increased by 78 percent between 2012 and 2016. The study also shows that Venezuela had the highest increase in malaria deaths in the world between 2016 and 2017, and there was an outbreak of diphtheria and malaria in 2016 and 2017, respectively. Increases in infant mortality in Venezuela started already in 2009, but shot up between 2012 and 2017. In this period there was an increase of infant mortality of 76 percent, while maternal mortality doubled in the same period. The main reasons point to the drop of imports starting in 2012, as well as a general deterioration of health systems.Footnote 30

A report from the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) highlighted the additional factor of the emigration of health personnel. The report estimated that 22,000 doctors emigrated from the country in 2018, a third of the total in the country in 2014, in addition to 6,000 laboratory technicians and 3,000–5,000 nurses.Footnote 31

These trends of social indicators’ worsening started before the sector sanctions were imposed in 2017. The increase in the infant mortality statistics started also before oil prices dropped in 2014, as did the rise in monetary poverty according to official data. The former may be an indication of structural problems. Thus, there is some evidence of forces other than deteriorating oil prices and its subsequent decline in imports affecting some of aspects of standard of living and these forces might have continued, even with a rapid recovery of oil income that sanctions partly prevented. However, most of the declines in standard of living seem to be linked with the timing of the decline in oil prices. While the sanctions did not turn the tide on any of these trends, they can be understood as preventing recovery once oil prices rebounded.

The sanctions are also thought to have caused some direct negative impacts on the humanitarian situation. One direct impact came from increasing scarcity of fuel. The inability to import refined gasoline used to mix with Venezuela’s heavier crude is mainly a consequence of the 2019 oil sanctions. Diesel was imported due to a special exemption, yet by 2020, it was withdrawn. This had significant consequences for the transportation of food and other essential goods. A second direct impact was the difficulty that humanitarian organizations and other civil society organizations experienced in operating in the country due to the financial sanctions. Although humanitarian imports are exempt from sanctions, many organizations experienced problems in conducting the transactions and accessing important goods in addition to the problems experienced due to a collapsing infrastructure and difficulties in accessing fuel for transport.

Sanctions and the Private Sector

While the sanctions intended to produce an economic contraction, they were aimed mainly at the public sector. Yet they have had several direct and indirect effects on the local private sector. Indeed, by 2024, according to a poll conducted by the business federation Fedecámaras, 81 percent of Venezuelan private businesses considered that they were negatively affected by sanctions.Footnote 32 The indirect effects are produced as the government has sought to adapt to the situation. Jointly, public, and private adaptation strategies have translated into a reconfiguration of the Venezuelan economy.

One of the direct effects of the sanctions on Venezuelan businesses is the decline in access to credit abroad. After the imposition of financial restrictions in August 2017, international banks started to avoid giving credit to any Venezuelan actor out of fear of being sanctioned. Although the three executive orders only prohibit transactions with the public sector, “overcompliance” was widespread. Companies report to have experienced reduced access to credit because of what Rodríguez calls “financial toxification,” leading banks to stop providing services to the Venezuelan private sector, often citing increased reputational risk.Footnote 33 Lack of access to foreign finance has led industrial enterprises to face difficulties accessing raw materials, in part due to lack of dollars. Others were cut off from their markets as they were unable to receive payment from abroad. To bypass the sanctions, businesses tried to “triangulate,” transferring payment in euros or rubles, or to bitcoin and from bitcoin to dollars. Even leaders of small and medium sized enterprises reported to have traveled to Moscow to open bank accounts, often with little success. Those who were successful reported that the “financial triangulation” allowed them to continue to operate, but with an estimated 10 percent increase in costs. The situation became even more difficult for the various industry and service companies that operate in the hydrocarbon sector. After the designation of PDVSA as a company subject to sanction in early 2019, credits were closed off for the many companies producing goods or services for some PDVSA-associated companies. Investments in the oil sector have thus dried up even further.

In addition, sanctions had several indirect effects. The contraction has led to a profound decline in aggregate demand fueled by a decline in real government spending. Moreover, as the government experienced a decline in income from the hydrocarbons sector, tax pressure increased on the manufacturing and commerce sectors. By 2019, the government demanded weekly tax payments to make up for the loss of income. As a consequence of increased tax pressure and arbitrarily implemented regulations and controls, more companies decided to move all or parts of their operations into the informal sector. Business representatives have stated that while in the past there was a common practice of “over-billing” (sobrefacturación) of 20 percent by private companies – 45 percent by public companies – to obtain subsidized dollars from the government, now the tendency is to “under-bill” to avoid taxes.Footnote 34 In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, some businesses moved operations online to cope with the lockdowns and other restrictions. Many Venezuelan businesses closed their formal operations but continued to operate on an informal basis.

Another effect of the sanctions is the deepening of political and often military control of different productive sectors. The complex impact of sanctions leading to this outcome can be illustrated by the agriculture and food production and distribution sectors. From the mid 2000s, the Venezuelan government sustained a policy of expropriations and centralization, intended to build food sovereignty, push forward land re-distribution, and weaken landed elites. These policies led to a decline in production and the political use of supplies and dollar allocation to producers. At the same time, the country became more reliant on imports. Increasing reliance on imports meant that the credit crunch and revenue reduction that resulted from the financial sanctions affected the ability of government food acquisition.

Food imports were then centralized through the enterprise of the armed forces, AgroFan, in 2017 while the food distribution mechanism established in 2016, the CLAPs, is also run by the military. The CLAPs function through community organizations that allocate food boxes directly to families. In a nutshell, food distribution became an important source of social control and, at the same time, a source of business for military actors who became crucial for the Maduro regime’s survival.

After the imposition of the oil ban, the Venezuelan government imposed a stringent monetary policy aimed at curbing inflation while also allowing dollars to circulate in the economy. In addition to a steep devaluation, in February 2019, the government obliged banks to maintain a reserve of 60–100 percent of deposits. This restrictive monetary policy ended access to credit for the nongovernment-aligned agricultural sector.Footnote 35 These restrictions were compounded by increasing fuel shortages that affected agricultural producers. Many resorted to military officers to distribute their output, since the military already has the logistical capacity to distribute, and controls supply chains and fuel access.

A further indirect effect has been a shift in the foreign economic relations with implications for how the different sectors are governed. To bypass sanctions, the Maduro regime allied closely with alternative powers. PDVSA partners with companies in the UAE and Russia to transport its oil and sell it in international markets. The bulk of oil exports have been purchased by Chinese private traders, while PDVSA has used transport operatives who sell Venezuela’s output through Malaysian intermediaries. These transactions and oil shipments occur off the radar with no proper registration and are disguised through different company operations.

The lack of international credit to Venezuela pushed the government to use gold ingots as a form of payment for transnational transactions. Gold extraction has spiked as the military has associated with criminal organizations who control mining territories and local.Footnote 36 The increased extraction has been crucial in the government’s ability to purchase goods abroad, through opaque sales of gold in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. In this case, the triangulation of transactions from gold to a convertible currency to a specific good or service means increasing transactional costs and a network of informal exchanges.

Last, to counter the effects of sanctions, the Maduro regime resorted to many changes to the economic policy. Gradually, the government has deregulated foreign currency use and liberalized the economy, through, for example, providing tariff exemptions. In late 2020, the NCA approved the “anti-blockade law,” which allows the government to privatize state-owned assets, including changing the composition of joint ventures in the oil industry (which would normally require parliamentary approval and force the state to hold at least 50% of assets). The law gives the government unchecked license to sell assets and disregards constitutional mandates in confidentiality and secrecy, with the goal of “protecting and assuring the effectiveness of measures taken by the Venezuelan government,” in the “protection against the coercive, unilateral, restrictive and punitive measures.”Footnote 37

The result of all these measures is a significant re-arrangement in the Venezuelan economic elite and economic governance. Privatization has benefitted business allies of the government in different sectors, from the agri-food business, such as AgroPatria stores and milk processing plants, to supermarket outlets and other companies in retail. Investors from Iran as well as Venezuelan private investors linked to the corruption scandal that led to the split of part of the opposition may have benefitted from these sales.Footnote 38 The government has also allowed private enterprises to issue dollar-denominated debt.Footnote 39 New businesses have emerged in the now more generalized dollar-denominated commerce of luxury products. The groups that have benefitted from these new markets are associated with government officials and cronies with sustained access to foreign currency.

The most significant losers are the traditional and medium to small business sector with no access to foreign currency and import lines. This has been affected not only by the sanctions’ financial restrictions but also by the government’s countermeasures. As a result, there is a weakened and less autonomous business sector, unwilling and incapable of providing material support to the political agenda of the Venezuelan opposition.

The Political Effect of Sanctions: A Divided Opposition

These impacts may also have contributed to the lack of achievements of the goals with the use of sanctions. The US initially formulated its goals in terms of combating drug-trafficking and ensuring respect for human rights. Later it went further in demanding the substitution of Nicolás Maduro and regime change. The Qatar accords of 2023 state that the goal and condition for eventual sanctions lifting is the celebration of presidential elections according to a set of criteria in 2024, and the subsequent entering into power of a “duly elected” president.Footnote 40

However, since the first sanctions were imposed the human rights situation has deteriorated sharply. This was evidenced in the report issued by the OHCHR in September 2020. It shows that while there were 120 extrajudicial killings by Venezuelan security forces in 2014 when the US imposed individual sanctions due to their alleged involvement in human rights abuses, the number had increased to 185 in 2017 and to 1,233 in 2019.Footnote 41 Cases of torture, disappearances and arbitrary detentions and imprisonment also increased.

At the same time, Venezuela took new steps in the process toward consolidating an authoritarian regime. While the 2017 financial sanctions were imposed as a reaction to the establishment of the NCA that set aside the legally elected National Assembly, the subsequent subnational and presidential elections were marked by electoral irregularities to an extent not seen previously.Footnote 42 Moreover, there was government intervention in political parties, and opposition politicians were banned, harassed, and imprisoned. With the noncompetitive election of the National Assembly on December 6, 2020, the Maduro government had essentially eradicated all opposition in national institutions and consolidated his authoritarian regime. In 2021, Maduro called for new negotiations and, in the context of a general review of the US foreign policy under the Biden administration, some measures reflecting a timid alleviation of the sanctions emerged. A more comprehensive attempt at lifting sanctions in exchange for electoral conditions and political participation for all came with the 2023 Barbados accord.

However, as previously mentioned, the 2024 elections were everything but free and fair. Moreover, following the government’s electoral fraud, an unprecedented wave of repression was set in motion. An October 15 2024 report on the pre- and post-electoral violence from the UNHRC documented widespread unlawful detentions, abuse and torture, twenty-nine deaths and close to 2,000 political prisoners, including over 60 children and youth.Footnote 43

The main theory of change behind the US sanctions was that reducing the income of the regime would produce internal divisions in the governing coalition, leading to a fall of the government. Since then, the desire to lift the sanctions has given Nicolás Maduro an incentive to negotiate with the opposition.Footnote 44 Moreover, Maduro has lost electoral support, and the governmental coalition shows signs of divisions.Footnote 45 However, we have not seen the kind of military defection or other forms of breakup of the government coalition that the proponents of sanctions had envisioned. Rather, as the regime has become more authoritarian, it has come to depend on a narrow “selectorate,”Footnote 46 rather than the electorate – an inner circle of strong regime supporters, and a new elite consisting of the military, and a new well-connected bourgeoisie (known in Venezuela as “enchufados” or “plugged-in”).

Moreover, the sanctions have produced clear division within the opposition. While the Venezuelan opposition has been divided since the entering of Hugo Chávez, the strategy that proposed Juan Guaidó as a new leader of a plan to bring the government down, achieved a unity not seen for many years. It was, however, short-lived. Opposition coordination soon broke down and different opposition factions have emerged around what strategies can be most efficient in achieving the goals of bringing a transition to democracy.Footnote 47 One of the most divisive issues has been the use of sanctions.

One may divide the opposition into three groups on that issue. The more radical parts of the opposition welcome sanctions. This group was for some time led by Guaidó. More radical leaders such as María Corina Machado and Antonio Ledezma have long been vocal defenders of the “maximum pressure” strategy and the idea of scaling up tensions to force a multilateral military coalition to intervene under the banner of Responsibility to Protect. As the Interim Government strategy failed, and accusations of corruption have plagued its administration, this group is now led by Machado, who overwhelmingly won the primary elections of the Unitary Platform in late 2023 for the opposition candidacy against Maduro. A second group, led by Henrique Capriles, former presidential candidate, has continuously called to stop measures that hurt the Venezuelan population, and argued that sanctions do not solve these problems. Another strand of the opposition has emerged to try and work within the parameters of the authoritarian nature of Venezuela’s political regime. Opposition parties such as Avanzada Progresista, Cambiemos, and Esperanza por el Cambio have sat with the government in a National Dialogue Table and participated in elections organized by the NCA. Among the main discursive elements of these organizations in a strong rejection of sanctions. Other groups have been implicated in maneuvers with the government to hijack party symbols. In essence, while sanctions were intended to pressure and divide the government, they have in turn served to divide the opposition.

According to surveys, a majority of Venezuelans are opposed to the sanctions. Although most people also answer that they mainly hold Maduro responsible for the economic collapse, the number of people additionally blaming sanctions is increasing.Footnote 48 This should indicate that the sanctions have a potential of backfiring and consolidating Maduro’s power.

The Political Economy of a Sanctioned Economy: Lessons for the Sanctions Literature

The Venezuelan case offers important lessons to the sanctions literature. The results of sanctions in Venezuela confirm the ineffectiveness of unilateral measures in provoking regime change. However, the most important lessons are about what changes these measures have created. First, there is an expansion of shadow economies and empowering of illicit and informal actors. Second, the military, as a fundamental constituency of the targeted regime, has gained considerable power, not only as a veto player in political decisions but as an active economic actor. Third, the Maduro government has used sanctions effectively as a unifying and justifying device that allowed it to weather the storm and, most importantly, use it as unconventional weapon to divide the opposition. This last point represents an important takeaway: sanctions can unintendedly hurt those who they are designed to help. Through a study of the effects of sanctions in Venezuela, we have highlighted these three processes.

In terms of the broader importance of this case for the literature on sanctions regimes, the downstream effects of sanctions in Venezuela confirm some of the developments that have occurred in other countries. Gordon argues that the impact of the sanctions regime in Cuba is substantial for the economy. Sanctions imposed on Cuba, according to Gordon, contribute to a case of “negative development” due mostly to the lack of access to markets and necessary imports as well as financial limitations that make simple transaction costly and cumbersome.Footnote 49

The issue of extraterritoriality is another important aspect of the US sanctions regime which seeks to expand its power over jurisdictions where it may not hold legitimate authority.Footnote 50 Similarly, the long history of sanctions in Iran helped strengthen the power of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which have slowly gained control over the economy, including in the oil sector, through acquiring contracts that other companies were barred from due to the sanctions’ regime.Footnote 51 Like in Iran, sanctions encouraged waves of privatization in Venezuela, which often benefitted the armed forces and elites associated with the government.

Another important lesson that stems from taking a more comparative and transnational perspective is that the shared experiences of targeted regimes may go beyond a political posturing and authoritarian solidarity. These shared experiences can also translate into effective alliances and fertile ground for business opportunities among targeted countries. Support for Venezuela from Iran, Russia, Turkey, and Syria – that add to the existing linkages with Cuba – is a testament of these developments. In past decades, China and other allies in Latin America were Venezuela’s closest partners, notwithstanding the continued linkages to the US. Recently, however, Venezuela’s elite has shifted the country’s economic and geopolitical allegiance to a close circle of sanctioned regimes that are willing to bypass sanctions and strengthen existing partnerships, even beyond ideological affinities.