Introduction

The Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa (EAMENA) project was established in 2015, in response to the rapidly increasing threats facing heritage in the region today, including urbanisation, agricultural expansion and conflict (Bewley et al. Reference Bewley, Wilson, Kennedy, Mattingly, Banks, Bishop, Bradbury, Cunliffe, Fradley, Jennings, Mason, Rayne, Sterry, Sheldrick, Zerbini, Campana, Scopigno, Carpentiero and Cirillo2016). Since its foundation, the project has primarily employed remote sensing methodologies, in combination with other methods including fieldwork and archival research, to document heritage sites across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, monitor their condition and to record and assess disturbances and threats affecting them (e.g. Rayne et al. Reference Rayne, Bradbury, Mattingly, Philip, Bewley and Wilson2017a; Rayne et al. Reference Rayne, Sheldrick and Nikolaus2017b; ten Harkel & Fisher Reference ten Harkel and Fisher2021; Rouhani & Huet Reference Rouhani and Huet2024). The data collected are held online in the EAMENA database (https://database.eamena.org/), which is available open-access for use by heritage professionals, researchers and students. The project is a collaboration between the Universities of Oxford, Leicester and Durham and is supported by the charitable foundation, Arcadia.

In 2017, the EAMENA project was awarded additional funding from the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund (CPF), to support training, capacity building and collaboration with heritage professionals in several countries across the Middle East and North Africa. As part of this programme, between 2017 and 2019, the University of Leicester branch of the EAMENA team organised a series of training workshops for participants from the Libyan Department of Antiquities (DoA). The workshops provided training for more than 20 Libyan heritage professionals and archaeologists in the use of digital methods and resources for heritage documentation, assessment and protection, including satellite imagery remote sensing, GIS, Google Earth Engine and the EAMENA database (Hobson Reference Hobson2019). A further grant from the CPF enabled the Leicester team to organise additional advanced workshops for our Libyan colleagues in late 2020 and early 2021 to reinforce and build on these skills, particularly with respect to using GIS and Google Earth Engine. Although initially intended to be in person, these workshops were held remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The work reported on in this article was initiated in early 2023 with the award of a third grant from the CPF to EAMENA, for a project entitled Mitigating Conflict and Climate Change Risks through Digital Heritage, Capacity Building and Consolidation, which was completed in January 2025. The overall aims of this project were to continue to build on the partnerships and skills established during the previous programmes and to enhance local capacity for monitoring and managing at-risk cultural heritage through the development of digital tools. Earlier training programmes emphasised issues such as conflict, urbanisation and agricultural expansion as threats to heritage, and while these have remained a key focus, the growing impact of climate change on heritage has also become of increasing concern among heritage professionals (ICOMOS 2019; Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Clarke, Wambui Ngaruiya and Wangui2020; Westley et al. Reference Westley, Andreou, El Safadi, Huigens, Nikolaus, Ortiz-Vazquez, Ray, Smith, Tews, Blue and Breen2021). Therefore, an additional aim of this project was to better understand and improve methods for assessing and addressing climate risks and their impacts on cultural heritage sites.

The work of the EAMENA project and our ongoing collaborations with our many regional partners are tailored to the differing needs and priorities of our partners in different countries. The EAMENA project’s work with partners in Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine and Iraq, for example, led by the Oxford and Durham teams, has focused on establishing bespoke, national and regional heritage management databases, and deepening sustainable capacity for maintaining them. In Jordan and Palestine, efforts to improve climate change assessment methodologies and assess current and future climate threats to heritage have also been undertaken through case studies emphasising local community involvement, research and fieldwork.

A key aim of the Leicester team has been to improve capacity within the Libyan DoA to monitor threats to heritage, particularly climate change, over large areas and in remote locations, through advanced remote sensing methods. The training with our Libyan partners during this phase of the project therefore focused on reinforcing skills learned in previous workshops in the use of Google Earth Engine and working on embedding these skills into existing workflows.

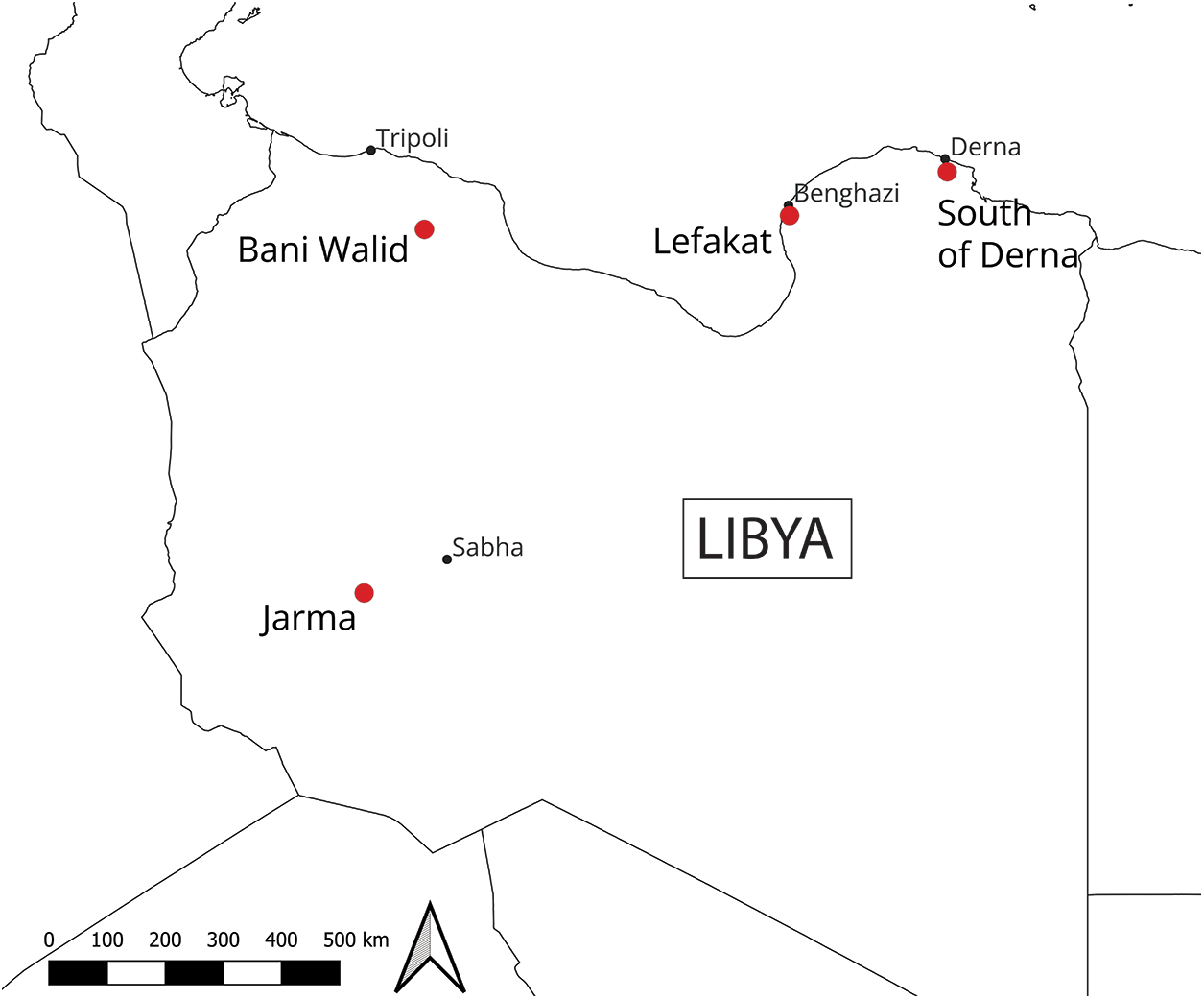

In particular, participants were trained in the use of a new Machine Learning Automated Change Detection (MLACD) method recently developed by the Leicester EAMENA team (Mahmoud et al. Reference Mahmoud, Sheldrick and Ahmed2024). The MLACD method was adapted for application to four case studies in different parts of Libya: Lefakat (Cyrenaica), Bani Walid (Tripolitania), the region south of Derna (Cyrenaica) and Jarma (Fazzan). Each of these case studies was followed by a survey campaign by our Libyan partners to validate the results of the remote sensing, survey the archaeological sites, record their condition and assess the disturbances and threats affecting them. A short extension to the project, which will take place during the latter half of 2025, was also granted by the CPF to support follow-up sessions to reinforce the technical skills and provide ongoing support for the DoA in their use of the MLACD method, as well as to support further analysis of the data collected during the fieldwork.

In the following sections, this article will provide an introduction to the MLACD method and its application to Libyan heritage and an overview of the training workshops and case studies investigated, providing background and context for the fieldwork campaigns, which will be reported on more fully in a series of separate articles. This introduction to the method and fieldwork will be followed by a summary of the successful outcomes of, and reflections on, this most recent EAMENA-CPF training programme and collaboration with our Libyan partners.

A new remote sensing method for monitoring heritage in Libya

Since the project’s foundation, the use, development and dissemination of open-access, remote sensing methodologies has been a core part of EAMENA’s work both in Libya and the MENA region more widely (Bewley et al. Reference Bewley, Wilson, Kennedy, Mattingly, Banks, Bishop, Bradbury, Cunliffe, Fradley, Jennings, Mason, Rayne, Sterry, Sheldrick, Zerbini, Campana, Scopigno, Carpentiero and Cirillo2016; Rayne et al. Reference Rayne, Sheldrick and Nikolaus2017b). The Leicester EAMENA team has primarily focused on the North-Africa region, and on the development of automated methods for detecting change to landscapes and heritage sites, to help speed up heritage monitoring efforts over large areas and enable heritage managers to target limited resources more effectively. Making use of the open-access, cloud-computing platform Google Earth Engine, EAMENA’s first Automated Change Detection (ACD) method was developed by the Leicester team and published in 2020 (Rayne et al. Reference Rayne, Gatto, Abdulaati, Al-Haddad, Sterry, Sheldrick and Mattingly2020). The method utilises Sentinel-2 satellite imagery, which has a resolution of 10 m per pixel. The main advantages of using this imagery is its global coverage and frequent revisit time: images are captured over the same part of the earth on average every five days. The full catalogue of these images is available for free through the Google Earth Engine platform.

The first ACD method works by selecting and comparing two Sentinel-2 satellite image composites of a user-defined area (e.g. a heritage site or landscape), from different dates, to identify any differences between them by calculating the difference in the values for each pixel of each image. The method generates a map which highlights the areas where differences in pixel value have been detected, i.e. areas of potential landscape change. These changes might be vegetation growth or clearance, construction, bulldozing, flooding, etc. The locations of known heritage sites are then overlaid onto this map and, where areas detected by the ACD as potential change intersect the buffer zones of the sites, these sites are highlighted, so that they can be prioritised for investigation and monitoring for potential damage (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Example of EAMENA ACD method results, around Waddan, Libya,assessing change between 2020 and 2024 (base map: Google Earth Satellite via xyz tiles, QGIS).

The advantages of this version of the ACD method are that it is easy to implement and to adapt to different contexts, and has a high level of overall accuracy, making it an effective and useful tool for detecting change to heritage sites. Training in this method was provided in previous CPF training workshops, and the script is available open access as part of the supplementary materials of the publication. Training documents and videos with step-by-step instructions on how to implement it are also available via the EAMENA website (https://eamena.org/cpf-training).

One limitation of this method, however, is that it offers only a binary assessment of change; it is not able to identify the type of change that has occurred. A second limitation is that it can only confirm that a change has taken place at some time between the start and end dates input by the user; it cannot identify precisely when an identified change has occurred. Users applying this method must consult high-resolution satellite imagery to further refine and validate the results.

The next phase of Leicester’s ACD work therefore aimed to develop a tool which would be able to identify the types of change detected as well as the date when they occurred, by incorporating advanced machine learning methods; the result is the EAMENA Machine Learning Automated Change Detection (MLACD) tool (see Mahmoud et al. Reference Mahmoud, Sheldrick and Ahmed2024 for full technical description of the method and the outputs it produces). Like the first ACD tool, the MLACD method was also developed using the Google Earth Engine platform and works by analysing Sentinel-2 satellite imagery based on user-defined locations and dates. However, where it differs, is that, instead of comparing only two images from the beginning and end of a given period, it employs supervised machine learning models to create land-classification maps for every available image within the range of dates specified by the user (Figure 2). This sequential time series of classified images enables the user to examine and illustrate in more detail how land-use across the defined study area has changed over time.

Figure 2. Example of a Sentinel-2 image and land-classification map generated by the MLACD for an excerpt of the Bani Walid case study area.

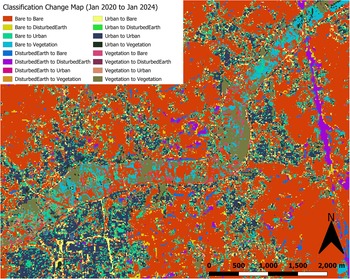

Users can then choose any two classified images from the time series to compare in order to generate a change map, which shows if and how each pixel has changed from one class to another between those two specific dates and assigns a new class categorising the type of change which has occurred (Figure 3). For example, if one or more pixels are classified as bare soil in one image, but as vegetation in a later image, they are categorised with the ‘Bare to Vegetation’ change class; pixels classed in this change category could represent areas of agricultural expansion. Validation using either high-resolution satellite imagery or fieldwork is still necessary to confirm the results, but this initial categorisation provides users with a rapid overview of the types of change which have been detected in a given landscape as well as an idea of their extent.

Figure 3. Change classification map for an excerpt of the Bani Walid case study area, showing change between 20 January 2020 and 4 January 2024.

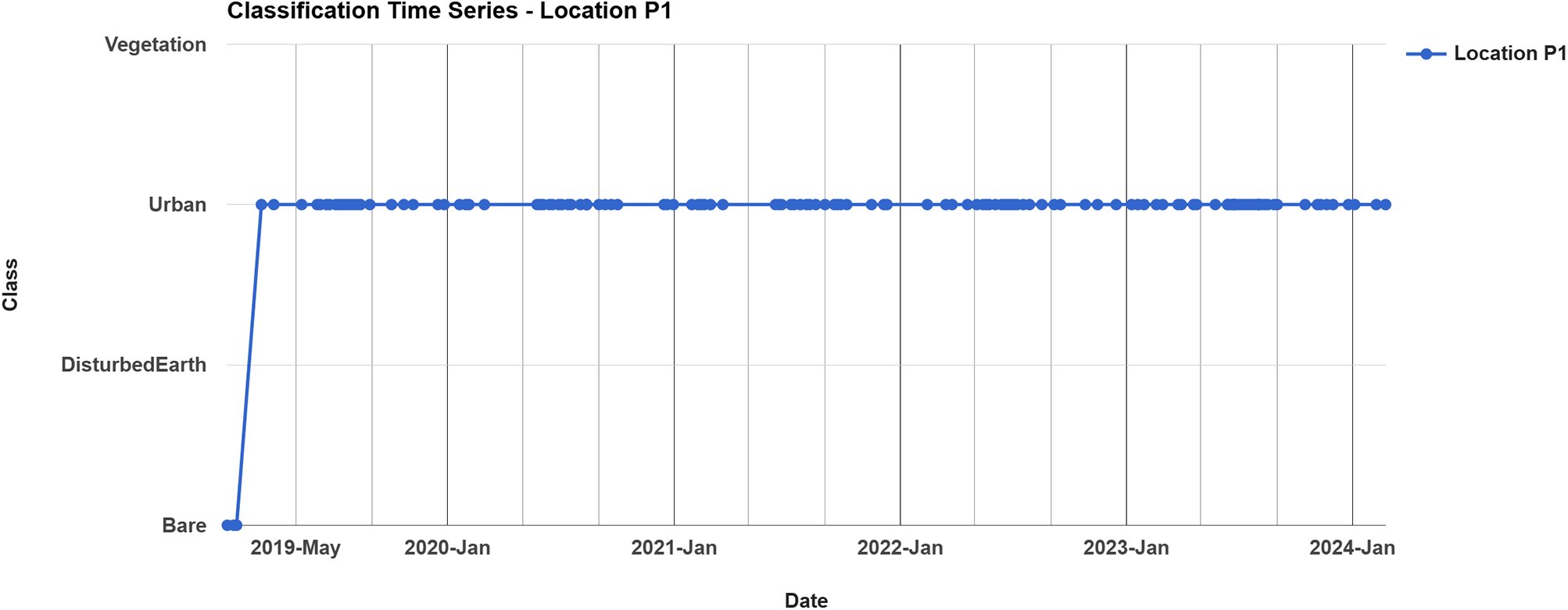

Like the initial ACD method, these data are then combined with the locations of known heritage sites, to identify which ones may be affected by a particular type of disturbance or threat. Users can also isolate a specific change class to illustrate the effects of one or more particular categories of disturbance. For example, Figure 4a shows a medieval village (EAMENA-0189418/Ziadda, Md230, Barker et al. Reference Barker, Gilbertson, B and Mattingly1996b, 191) in the Bani Walid case study area, with the location of pixels which were identified by the MLACD as having changed from Bare to Urban (i.e. modern buildings) between 2019 and 2024 highlighted. The detected change is confirmed by the high-resolution imagery in Figures 4b–d, which show the construction of a modern building over the south part of the archaeological site, first appearing in March 2019. This change is also corroborated by the classification time series chart which is automatically generated by the MLACD during analysis, showing how the pixel values at location P1 (indicated in Figure 4), have changed from the value indicating the Bare class to that of the Urban class (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Example of heritage site EAMENA-0189418, in Bani Walid, where the MLACD detected a change from Bare to Urban (Basemaps: Airbus, Google Earth).

Figure 5. Classification time series chart generated by the MLACD for location P1, showing the change in class from Bare to Urban in early 2019.

The MLACD script employs a user-interface to facilitate the entry of certain variables, though others must be entered directly into the code. Comprehensive training documentation has therefore been produced to help enable users with varying abilities and experience to apply the method and adapt it to different case studies. The code and documentation are available online and open access via the EAMENA project’s Github page: https://github.com/eamena-project/EAMENA-MachineLearning-ACD.

Training workshops and case studies

Between October 2023 and November 2024, supported by the CPF grant, the Leicester EAMENA team organised three workshops to introduce the MLACD method to Libyan heritage professionals and train them to implement and adapt it to different regions and case studies. The grant was initially intended to fund only one, in-person training workshop, which was held in late 2023 for six Libyan participants. The aim of this workshop was to address two case studies (Lefakat and Bani Walid), to be followed by fieldwork, also funded by the grant (Workshop 1). However, the unexpected cancellation of another element of the project (due to issues beyond our control) enabled us to redeploy the unused funding to organise two further hybrid workshops, each addressing an additional case study (the region south of Derna and Jarma) and accompanying fieldwork. These events took place in 2024 (Workshops 2 and 3), with participants attending from Libya and EAMENA team members providing teaching and support online. The four case studies investigated were chosen in collaboration with the DoA, taking into account different issues affecting the heritage of different regions of Libya (Figure 6). A more detailed report on each of the four case studies and the results of the fieldwork campaigns will be published in separate articles.

Figure 6. Location of the four case studies investigated in Libya.

The organisation of each workshop was overseen by the Leicester EAMENA-CPF team, in direct collaboration with the Libyan DoA, and led by Training Manager Dr Ahmed Buzaian and Researcher Dr Ahmed Mahmoud, with support from Dr Nichole Sheldrick, Prof. David Mattingly and Dr Mohamed Kenawi. Prof. Muftah Ahmed (az-Zaytuna University, Libya) also provided support in delivering and organising all of the training events and during the subsequent fieldwork. Across the three workshops, 21 participants from the DoA received training in the MLACD method, each of whom received a new laptop to facilitate the work. The DoA was responsible for the final selection of participants, though we requested that they be selected from different regions of Libya to ensure that the skills would reach people in different offices across the country.

Each workshop followed a similar programme, beginning with a general introduction and overview of the EAMENA project’s aims and methods and a rapid overview of the EAMENA database, focusing in particular on searching and exporting data. These introductions were followed by reviews of QGIS and the use of open-access, high-resolution satellite imagery for assessing the condition of heritage sites. This also included a review of the main tools and features of Google Earth Pro, in particular how to create point, polygon and line features, view historical imagery and how to edit and add shapefiles and rasters, which are important skills for validating training samples and change classification results generated by the EAMENA MLACD.

Participants were then given a detailed introduction to the MLACD method, starting with an overview of the features, functions and capabilities of Google Earth Engine as a geospatial analysis platform (Figure 7). This was followed by instructions and demonstrations for each of the steps of the MLACD process, including defining variables and classification settings, selecting and inputting training samples, setting visualisation parameters and running the script. Once the technical steps were presented, sessions were also devoted to understanding and interpreting the outputs generated by the MLACD method and the importance of validating the results through fieldwork or consulting high-resolution satellite imagery. Each trainee was asked to prepare a presentation based on the application of the method to their own areas of interest in order to help them practise the method and demonstrate the skills they had learned. At the end of each workshop, each participant was presented with a certificate to mark the successful completion of the training.

Figure 7. Dr Ahmed Mahmoud leading the EAMENA MLACD training during Workshop 1 in Tunis (Photo: EAMENA project).

Workshop 1: Lefakat (Cyrenaica) and Bani Walid (Tripolitania)

The first workshop took place in Tunis, over the course of five days in October 2023, with three members of the EAMENA Leicester team providing training for six participants from the Libyan DoA (Figure 8). Three of the Libyan participants had attended at least one previous EAMENA training workshop in remote sensing and GIS methods, and all participants had at least some previous training and experience in remote sensing and/or GIS, at various skill levels. Two of the participants came from the Tripoli office, two from Benghazi, one from Lepcis Magna and one from Ghadames.

Figure 8. Libyan participants and Leicester EAMENA-CPF team members at Workshop 1 in Tunis (Photo: EAMENA project).

In the course of this workshop, two case studies were investigated and analysed using the MLACD method. The first concerned the region of Lefakat, on the south edge of Benghazi in western Cyrenaica. Goodchild’s 1950–51 expedition covering the area between Ajdabiya and Benghazi, identified a series of fortified farms (Goodchild Reference Goodchild1951), one of which is located within the Lefakat case study area; a more recent survey by Ahmed Buzaian in the area southwest of Benghazi recorded two additional sites within the Lefakat area (Buzaian Reference Buzaian2022). However, beyond these studies, the area has received relatively little attention.

Adding a number of sites identified through remote sensing survey, the EAMENA team initially identified a total of 39 sites for investigation, 30 of which were visited in the field and targeted for more detailed analysis using the MLACD. Most of these sites seem to be previously unpublished, but appeared to be primarily Roman structures and settlements, often referred to locally as ‘Sira’ or ‘Qasr’. The rapid expansion of Benghazi poses a direct threat to the sites in this area, with the remote sensing survey and MLACD indicating that a variety of related issues such as bulldozing, dumping and construction have affected many of these sites (Figure 9). Fieldwork in January 2024 enabled the team from the DoA to validate the findings of the remote sensing and MLACD, record the condition of the sites and assess the extent of the damage (for the full publication of this case study, see Buzaian et al. Reference Buzaian, Mahmoud, Sheldrick, Alhrari and Alshareef2025).

Figure 9. Locations of two Roman-period sites in the Lefakat case study area in 2009 and 2025. NB the development around the southern of the two sites occurred after the fieldwork, illustrating the ongoing nature of the issue (Basemaps: Maxar Technologies, Google Earth).

The second case study investigated during Workshop 1 focused on the area of Bani Walid, in northwestern Libya. In the 1980s, the UNESCO Libyan Valleys Survey recorded hundreds of sites along the banks of the wadi in and around the modern town, dating from the Roman through medieval and early modern periods (Barker et al. Reference Barker, Gilbertson, B and Mattingly1996a; Reference Barker, Gilbertson, B and Mattingly1996b). However, since that time, many of these sites have been damaged or destroyed due to the rapid expansion of the modern town of Bani Walid and in the aftermath of the 2011 revolution (see Figure 4, above). The aim of this case study was therefore to reassess the condition of a selection of these previously recorded sites and investigate the extent to which they have been affected by these issues. A total of 211 sites were analysed using the MLACD, with fieldwork taking place in February 2024 to validate the results.

Workshop 2: South of Derna (Cyrenaica)

As mentioned above, after the first workshop had been completed, we were able to redeploy extra grant funds to support additional workshops in Libya, due to the unexpected cancellation of another part of the project. The first of these additional training workshops took place online over four days in May 2024. Seven members of the DoA participated, including four from the Shahat office, one from Tocra, one from Tobruk and one from Bani Walid. Only one participant had previously attended an EAMENA workshop, and others had varying levels of familiarity with remote sensing and GIS. Most of the trainees were able to gather together in person in Shahat with Prof. Muftah Ahmed present as a tutor, in order to better facilitate learning the method together with the core Leicester EAMENA-CPF training team leading the training remotely and providing instruction and support online. In addition to the core training team, three participants of the first workshop also attended Workshop 2 to act as additional tutors and provide support.

In consultation with both the British Council and the DoA, we proposed that this workshop should focus on assessing the damage to heritage sites caused by Storm Daniel, which devastated northeastern Libya in September 2023. The city of Derna was one of the worst-hit areas, and a number of reports quickly emerged assessing the scale of the damage in the region (Abdulkariem Reference Abdulkariem2023; Walda et al. Reference Walda, Alkhalaf and Wootton2023a; Reference Walda, Alkhalaf, Wootton, Bushah and Al-Haddad2023b). This case study aimed to assess the heritage sites in rural areas south of the city and to better understand how natural disasters of this kind, which are becoming more and more frequent due to climate change, may affect archaeological landscapes. Previous surveys in the area, conducted by the DoA in co-operation with the French Archaeological Mission prior to seismic survey for oil exploration, had already identified many sites in this area, from prehistoric lithic sites to Hellenistic, Roman and medieval sites (de Faucamberge et al. Reference de Faucamberge, Marini, Nadalini and Michel2015). A total of 90 sites were analysed by the MLACD, with fieldwork taking place immediately following the training in late May and early June 2024 (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Qasr Bu Zayd (EAMENA-0116631), a probable Hellenistic temple-tomb in the South Derna case study area, photographed during the field work (Photo: DoA Libya).

Workshop 3: Jarma (Fazzan)

The third training workshop took place with eight Libyan participants gathered in Jarma, Fazzan over a four-day period in November 2024. The training workshop was conducted in a hybrid format, with Prof. Muftah Ahmed leading sessions in person, while members of the Leicester EAMENA-CPF team offered support and presented certain sessions online. This marked the first time that one of our advanced training workshops was primarily led by a Libyan expert. Having the majority of the sessions run in person reduced the impact of problems such as internet and power outages in Libya, which frequently cause delays and interruptions when trying to run the sessions remotely from the UK. Of the eight participants, most were based in different areas of the Fazzan region, with one coming from Tripoli (Figure 4).

The area around Jarma is home to a uniquely preserved landscape related to the ancient Garamantes, who established the first true Libyan state and urban society in the Saharan oases (ca. 1000 BCE to AD 700), based on sophisticated irrigation technology and advanced oasis agriculture. This region holds great cultural significance for Libya’s heritage, and hundreds of sites dating from the Palaeolithic through to Early Modern periods were previously recorded during surveys conducted by a British-Libyan Fazzan Project in the region from 1997 to 2011, as well as by earlier archaeologists and explorers like Charles Daniels (Mattingly et al. Reference Mattingly, Daniels, Dore, Edwards, Hawthorne and Mattingly2003, Reference Mattingly, Daniels, Dore, Edwards, Hawthorne and Mattingly2007, Reference Mattingly, Daniels, Dore, Edwards and Hawthorne2010, Reference Mattingly, Daniels, Dore, Edwards, Hawthorne, Thomas, Leone and Mattingly2013). When the sites were surveyed in the early 2000s, a protection plan was proposed to preserve this important landscape by limiting the modern farming development. However, the collapse of state power in 2011 and the subsequent lack of state funding to support agreements with local landowners has meant that agricultural development schemes have now restarted in this area.

A total of 311 sites that had been previously recorded by the Fazzan Project in the area around the town of Jarma were therefore analysed in the MLACD case study, a selection of which were investigated during the fieldwork which immediately followed the training. The new fieldwork has highlighted the extent of new damage and recorded indications of planned further expansion of the farms, causing visible impacts on archaeological sites (Figure 11). Of equal concern is the ongoing development, including the drilling of new water wells and the installation of power lines. At the invitation of our Libyan colleagues within the DoA, the Leicester EAMENA team helped to draft a new emergency plan to present to the Libyan government concerning the protection of this important landscape.

Figure 11. Example of heritage sites in the Fazzan case study area affected by agricultural expansion, including foggaras (ancient irrigation channels) and Garamantian cemeteries (Basemaps: Maxar Technologies, Google Earth).

Training feedback and outcomes

At the end of each training workshop, participants were given the opportunity to rate various aspects of the training and to provide feedback on their experiences. Overall, the feedback received from the trainees was very positive, with most rating various aspects of the training such as the communication and organisation highly. The workshops were delivered almost entirely in Arabic by native speakers among the EAMENA-CPF team, rather than via translators; many of the trainees specifically mentioned that this added greatly to their understanding of and engagement with the material. This not only ensured more direct and clear communication, but also created a more inclusive learning environment, contributing significantly to the overall effectiveness of the training.

Almost all of the participants indicated that they would be interested in attending further training in Google Earth Engine, and the EAMENA MLACD method in particular, and would recommend the training to other colleagues. In comments, trainees noted that these skills were relevant to their jobs and they were enthusiastic about learning and improving their skills in using Google Earth Engine for archaeological purposes. An important point raised was that ongoing communication and support from the EAMENA team after the formal training programme had ended would be key in order to ensure that they were able to continue honing these skills and incorporate them effectively into their work.

For those who attended Workshops 2 and 3 online, questions about the effectiveness and accessibility of this format received mixed ratings. Internet service in Libya is generally inefficient, a challenge further exacerbated by frequent power cuts. In addition to the technical challenges, participants noted that in-person events facilitate more direct interaction between trainers and trainees, allowing for immediate clarification of doubts and a more dynamic learning environment. Additionally, face-to-face training can create a more focused and immersive experience, minimising distractions that are often present in online or hybrid formats. The social aspect of in-person training also encourages networking and direct collaboration with peers, which can further enrich the learning process. While it was acknowledged that online training is a practical option when in-person attendance is not feasible, all the trainees indicated that they would prefer to have the training face to face, whenever possible.

User experience and technical feedback from the trainees on the MLACD method itself, both during the training and subsequently as participants have put the method into practice, has also been invaluable. Applying and adapting the MLACD across three workshops and four different case studies resulted in the method being repeatedly tested by users, who were able to identify problems with the script and suggest improvements and refinements, based on real-world experience. For instance, based on user feedback and experience, since the trainings the user interface panel has now been modified to further reduce the need to engage directly with the code interface, as well as to simplify and automate the generation of outputs related to specific types of identified changes. One trainee also raised the important point that most remote sensing methods are more effective at detecting sites which have more substantial archaeological traces such as mounds or buildings, and less effective when applied to sites with lithic scatters or rock art, emphasising that the MLACD method is a tool which can be used to enhance, but not replace, more traditional fieldwork activities.

Finally, an unplanned but welcome and positive outcome of the training was that, while the first workshop was organised and run fully by the Leicester EAMENA-CPF team, during the second and third workshops, Libyan colleagues, who had either acted as tutors or participants in the first training, were increasingly able to take on more of the direct teaching responsibility. As mentioned above, Workshop 3 was almost entirely led by Prof. Muftah Ahmed, with members of the EAMENA Leicester team on hand only to offer support and answer questions where necessary. This was not a deliberate strategy, but came about as a natural progression of the training events, as those who had taken part in the earlier workshops became more confident with the method and in their ability to train others.

Discussion

Both in discussions during the course of the training workshops and in subsequent feedback forms, participants were asked to reflect on and identify what they felt were the most urgent threats facing heritage in Libya. By far the most common threat to Libyan heritage mentioned by the participants in the written feedback was urban expansion, with 20 of the 21 trainees referring to it specifically. There is no doubt that this has long been a threat to Libyan heritage, in many parts of the country (Menozzi et al. Reference Menozzi, Di Valerio, Tamburrino, Shariff, d’Ercole and Di Antonio2017; Rayne et al. Reference Rayne, Sheldrick and Nikolaus2017b), and the case studies and fieldwork in Bani Walid and Lefakat in particular have shown that it continues to be a threat to heritage which needs to be monitored.

The second most commonly cited problem was agricultural expansion, with eight trainees specifically mentioning it. Interestingly, in this case, six of the eight who identified agricultural expansion as a major threat were participants from the Fazzan training, perhaps reflecting the fact that uncontrolled agricultural expansion has been a particular problem in this area (see e.g. Rayne et al. Reference Rayne, Sheldrick and Nikolaus2017b, 40). This particular issue was also discussed in an online meeting held during the course of the fieldwork in Fazzan following the final workshop, when the Libyan team reported their first-hand observations of the most significant threats affecting the area and their documentation of the recent re-escalation of agricultural development.

Both looting and climate change were mentioned by seven participants each as significant issues affecting Libyan heritage; other problems identified included vandalism, erosion, quarrying, lack of awareness and lack of resources. While these observations are anecdotal and represent only a small sample size of heritage professionals in the country, they are important indicators of the experience and perceptions of those who are currently working within the DoA.

Participants were also asked to give their views on how climate change is affecting Libyan heritage both in the feedback and in discussions which took place at the end of each workshop. The trainees largely agreed that climate change is having a serious impact on archaeological sites both in their own country and worldwide. Participants cited examples from their personal experience in Libya, clearly illustrating how climate change is affecting these sites. The example of Storm Daniel and its devastating impact on Derna and the surrounding landscape, which had occurred only weeks prior to Workshop 1, was foremost in many people’s minds. Some mentioned the impact of rising sea levels, putting coastal sites at risk of erosion and submersion. Others noted that temperature fluctuations and changing weather patterns (e.g. drought or heavier than normal rainfall) negatively impact specific types of Libyan heritage, such as mudbrick architecture and rock art.

This dialogue aimed to explore the challenges faced by archaeologists in protecting these sites in the face of these issues and how to mitigate the effects. It was noted that detecting the impact of climate change is not an easy task; while sometimes sudden, extreme events can be attributed to climate change, more often, it is seen in long-term, gradual change, which we may not see the full effects of for many years. As one participant pointed out, while we may not be able to halt climate change entirely, as heritage professionals, we can mitigate its impact through monitoring the condition of sites, addressing identified problems and conducting rescue interventions when necessary. The trainees emphasised the need to develop innovative methods, such as the EAMENA MLACD, to protect and safeguard cultural heritage, as well as the need for governments to invest in and support this work.

Conclusions and looking forward

The recent EAMENA-CPF programme summarised in this article has been a successful and productive collaboration and has served to strengthen both EAMENA’s and the University of Leicester’s long-standing partnership with the Libyan DoA. The training and fieldwork have provided the opportunity for members of the DoA and the EAMENA team to identify and reflect together on the greatest threats affecting Libyan heritage today and to discuss, develop and test new methods for approaching this problem, in a collaborative manner. Each of the four regions targeted by the chosen case studies face serious threats to heritage, from a variety of factors including rapid urban and agricultural development, lack of (enforcement of) regulations, particularly during and immediately after the civil war, and rapidly changing climatic and environmental conditions. The training and fieldwork have been crucial in demonstrating the potential of the EAMENA MLACD workflow for rapid assessment and the advantages of integrating this method into the work of the Libyan DoA through hands-on training. The application of the method to the real-world case studies undertaken by our participants, the results of which will be published in detail in forthcoming articles, has been an invaluable testing ground for the method. The feedback provided by participants on the ease of use and effectiveness of the online tool and workflow have been integral to continuing to refine and develop it, and the short extension to the project granted by the British Council for the latter half of 2025 will allow us to provide ongoing support and continue this important collaboration.

Our hope is that the development and dissemination of advanced remote sensing methods like the EAMENA MLACD can contribute to building capacity within the DoA, and will continue to aid Libyan heritage professionals in their important work of protecting and caring for Libya’s heritage. While the EAMENA project is committed to continuing this partnership and providing support in these methods for as long as it remains active, these methods will only have long-term impact and sustainability if our partners are willing and able to take active steps to incorporate them into their working practice, train others and ultimately take the lead on continuing to build on and develop them. The willingness and enthusiasm of our Libyan participants to not only learn and apply this method, but also to be able to move into training roles during the course of this project is a positive and encouraging indicator that these steps are being taken, and that this method will continue to be used and disseminated by Libyan heritage professionals in the DoA and across Libya.

Acknowledgements

The EAMENA training and fieldwork programmes described in this paper were funded by the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund (LG1-0097-22). The core work of the EAMENA project is generously funded by Arcadia (2312-5142). We wish to express our gratitude to the Libyan Department of Antiquities and especially its Director Dr Mohamed Faraj, the Board of Directors and the Head of the Training Office, Abdulmunam Abani, for their continued support of the EAMENA project and co-operation. Prof. Muftah Ahmed (az-Zaytuna University) has been instrumental in organising several of the trainings and leading the fieldwork campaigns in Bani Walid and Jarma and also co-directed the south Derna fieldwork. Naser Alhrari (DoA Benghazi) led the fieldwork in the Lefakat region and also co-directed the south Derna survey.

We are extremely grateful to the British Council offices in Algeria, Libya and Tunisia, for facilitating the import and shipment of laptops to our trainees in Libya. During the period in which the work described in this article was undertaken, the Leicester EAMENA team was directed by Prof. David Mattingly and from July 2025 it has been directed by Prof. Ruth Young and we are grateful to both for their ongoing support of this work. We wish to thank our admin team at the University of Leicester, particularly Krupesh Mistry, for all their help organising travel and logistics. We are also grateful to EAMENA Project Director Bill Finlayson and the Oxford team for their support.

Finally, we wish to thank all of the participants in the training and fieldwork for their hard work and enthusiasm: Abdulmunam Abani, Lamin Ali Lamin Abdulaati, Emhemd Alaskri, Naser Alhrari, Abdulkarem Ali, Ahmed Mohammed Ali, Fouzi Abdulsalam al-Raeid, Hani Alshareef, Husayn AlSherif, Abulsamad Mohammed Alshiyn, Nader El Kanadi, Dawoud Husayn, Muntasir Fadheel, Abdullah Farhat, Munsif Khatab, Abdalnasser Mansur Madi, Ali Yousuf Jarymi Makani, Abdulqadir Adrees Salih, Ahmed Abdulmawlay Tayib, Almahde Abdulraziq Yousuf, Ashref Zurgani. Omar Muhammad Burwais, Abdullah Muhammad Muftah and Riyad Al-Said also took part in the fieldwork campaigns.