In order for leadership to exist, there must be followers; yet followers remain an understudied component of the dynamic between leaders and followers (Baker, Reference Baker2007; Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera, & McGregor, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010; Shamir, Reference Shamir, Shamir, Uhl-Bien, Bligh and Pillai2007, Reference Shamir, Uhl-Bien and Ospina2012). Followers represent the majority of participants in the leadership process (Crossman & Crossman, Reference Crossman and Crossman2011), highlighting the need for a followership-based approach, which incorporates the ‘nature and impact of followers and following the leadership process’ (Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe, & Carsten, Reference Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe and Carsten2014: 96). The role-based view of followership suggests that followers construct and enact their own roles in relation to leaders (Carsten et al., Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010; Uhl-Bien & Pillai, Reference Uhl-Bien, Pillai, Shamir, Uhl-Bien, Bligh and Pillai2007). However, the extent to which followers' social constructions of their roles influence leadership processes is still unclear (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018). By studying the extent to which such role constructions influence leaders' behavior and effectiveness, a more thorough understanding of how followers influence the leader-follower dynamic can be achieved (Carsten et al., Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010; Lord & Maher, Reference Lord and Maher1991; Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe and Carsten2014).

Studies using a role-based approach have shown that follower characteristics, traits, and styles influence how they construct their role in the leadership process (Benson, Hardy, & Eys, Reference Benson, Hardy and Eys2016; Carsten et al., Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010; Carsten & Uhl-Bien, Reference Carsten and Uhl-Bien2012; Oc & Bashshur, Reference Oc and Bashshur2013). Notably, followers' beliefs about the ways they view and enact their roles – follower role orientations – can influence their ability to be successful (Carsten et al., Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010; Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe and Carsten2014). Carsten et al., (Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018) demonstrated that the extent to which followers socially construct their roles using a passive, anti-authoritarian, and co-productive role orientations allows followers to upwardly influence leaders' attitudes and motivations. Yet, despite considerable research defining follower role orientations, there has been little guidance on how individuals enact role-oriented beliefs to influence leader behavior and effectiveness through the leader-follower relationships (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018). Because the leadership process involves social exchanges between leaders and followers, interaction closeness and quality may serve as a critical link to these important leader outcomes (Lord & Maher, Reference Lord and Maher1991; Martin, Guillaume, Thomas, Lee, & Epitropaki, Reference Martin, Guillaume, Thomas, Lee and Epitropaki2016; Thomas, Martin, Epitropaki, Guillaume, & Lee, Reference Thomas, Martin, Epitropaki, Guillaume and Lee2013). As such, research that provides a better understanding of how followers with different role orientations pursue relationships with leaders and how these interactions allow them to contribute to leader outcomes is key to situating the importance of the follower role (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Griggs, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, Griggs, Gentry, Clerkin, Perrewe, Halbesleben and Rosen2016).

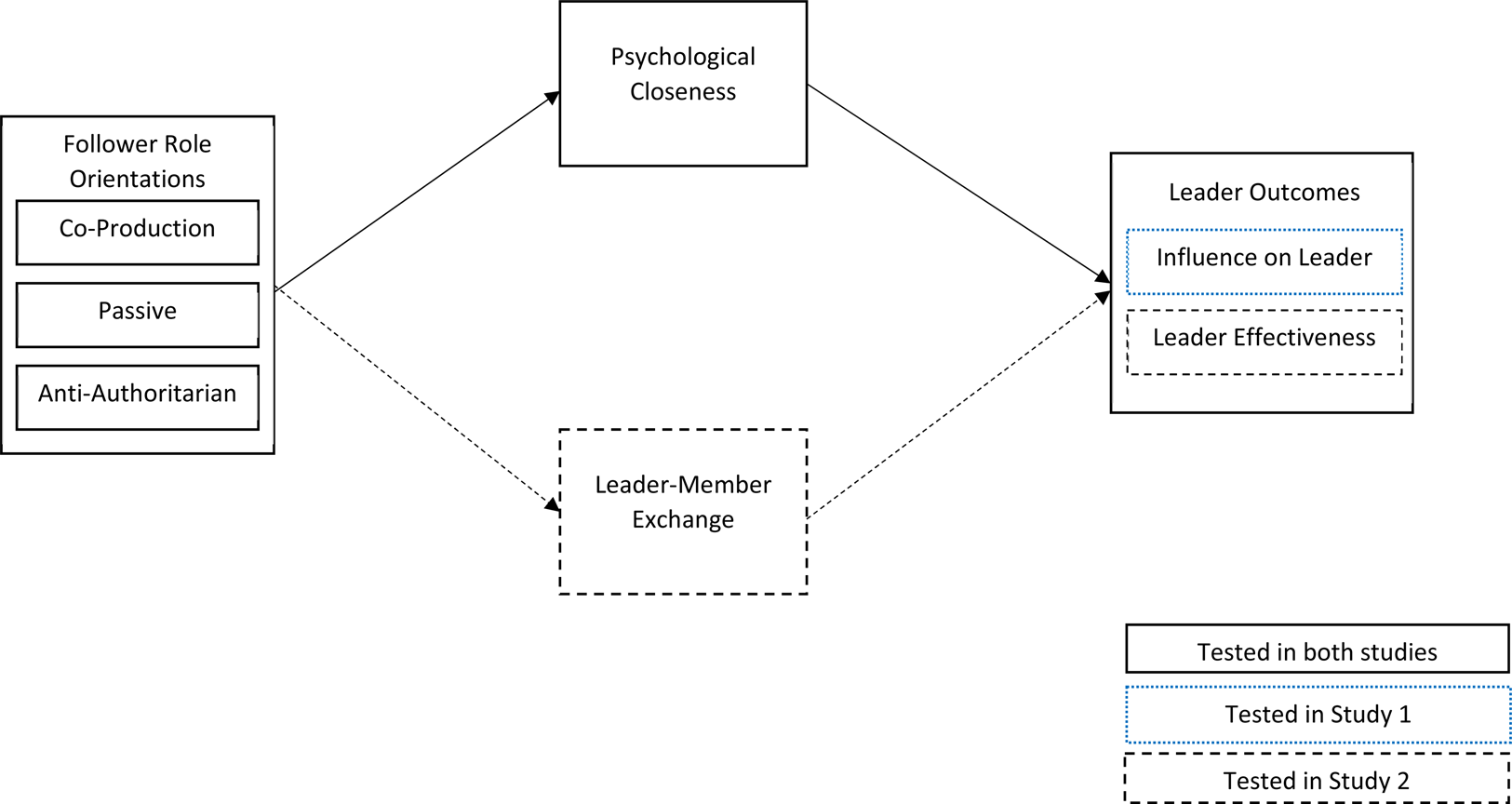

This present study attempts to address that gap by incorporating an essential aspect of the leadership process presently missing in the followership research: how follower's social constructions of their own roles impact the psychological and social relationship with leaders and, subsequently, help shape and attain leadership goals. Over two studies, the current research draws from literature using a role-based view of followership (Carsten et al., Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010; Carsten & Uhl-Bien, Reference Carsten and Uhl-Bien2012; Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe and Carsten2014) to examine how follower role orientations (co-production, passive, anti-authoritative) influence the development of positive relationships with leaders – through psychological closeness and leader-member exchange (LMX) – and subsequent leader outcomes, such as influence on leader and leader effectiveness.

In doing so, this research makes three contributions to existing literature. First, this study is one of the first to simultaneously explore the potential impact of different follower role orientations. Prior studies have predominantly looked at outcomes produced by proactive personality (e.g., Xu, Loi, Cai, and Liden, Reference Xu, Loi, Cai and Liden2019), co-production role orientation (e.g., Carsten and Uhl-Bien, Reference Carsten and Uhl-Bien2012) or passive followers (e.g., Carsten, Uhl-Bien, and Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018), yet this leaves a notable dearth in the literature on follower role orientations, as there is need to examine any collective or shared variance in how all three role orientations (e.g. co-construction, passive, and anti-authoritarian) predict relevant leader outcomes. This is especially important, as recent research has demonstrated the potential impact of anti-authoritarian members in affecting group outcomes (e.g., Aghaei, Isfahani, Ghorbani, & Roozmand, Reference Aghaei, Nasr Isfahani, Ghorbani and Roozmand2021; Almeida, Ramalho, & Esteves, Reference Almeida, Ramalho and Esteves2021; Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester, & Lester, Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018). Therefore, this study fills an important need by extending existing role-based followership literature to incorporate the effects of several different follower role orientations. In doing so, this study uncovers which role orientations are most influential on aspects of the leadership process.

Second, this study adds a meaningful contribution to research in the role-based view of followership by advancing knowledge on how followers co-create leader-follower relationships. While existing literature has noted that proactive followers can influence LMX relationships (Carsten & Uhl-Bien, Reference Carsten and Uhl-Bien2012; Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Loi, Cai and Liden2019), followers' role beliefs shape the way they psychologically relate to their leaders. Psychological closeness is often thought to moderate the relationship between behaviors and leadership outcomes and often viewed only from the leader's perspective (Antonakis & Atwater, Reference Antonakis and Atwater2002). This research attempts to show that followers actively construct their psychological relationship with the leader, in addition to their social exchanges. Thus, the present investigation adds to the current understanding of leader-follower relationships by showing an impact of follower-perceived psychological closeness, in conjunction with contributions to LMX.

Finally, the current research explores the way in which follower's perceptions of their own roles (e.g., follower role orientations) can affect important leader outcomes, thus helping contextualize the impact of the follower role (Howell & Shamir, Reference Howell and Shamir2005). Unlike prior studies, the current research shows that follower role orientations have an effect beyond influencing follower behaviors (e.g., Carsten and Uhl-Bien, Reference Carsten and Uhl-Bien2012) and changing leader perceptions (e.g., Carsten, Uhl-Bien, and Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018). Specifically, this research shows that followers' role orientations influence task-related leader behaviors and leader effectiveness. By addressing how follower role orientations influence both in the context of the same study, this research answers calls to provide a holistic understanding of how role-based followership can facilitate leader performance (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018; Sy, Reference Sy2010; Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe and Carsten2014).

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Role-based perspectives of followership

The treatment of followers historically in leadership research has been mixed, despite playing an integral role in the leadership process (Shamir, Reference Shamir, Uhl-Bien and Ospina2012; Uhl-Bien & Carsten, Reference Uhl-Bien, Carsten, Berson, Katz, Eilam-Shamir and Kark2018). As a result, there have been multiple perspectives on how to include followers as instrumental components in the process. Research using the ‘leader-centric’ perspective focus on how leader traits and behaviors influence followers in organizations (Chemers, Watson, & May, Reference Chemers, Watson and May2000; Gooty, Connelly, Griffith, & Gupta, Reference Gooty, Connelly, Griffith and Gupta2010). These studies tend to downplay the role of followers, treating them as passive recipients of leaders' influence (Carsten & Uhl-Bien, Reference Carsten and Uhl-Bien2012; Sy, Reference Sy2010; Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe and Carsten2014). In other cases, studies provide a more ‘follower-centric’ view that incorporates the followers' beliefs and attributions of leadership more prominently in the construction of leadership (Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe and Carsten2014). Although follower-centric studies consider the effect of leaders on followers, followers are frequently conceptualized as mere situational factors that leaders need to consider (Judge, Piccolo, & Ilies, Reference Judge, Piccolo and Ilies2004), overlooking how followers perceive their own roles in the leadership process (Collinson, Reference Collinson2006; Crossman & Crossman, Reference Crossman and Crossman2011; Kellerman, Reference Kellerman2008; Uhl-Bien & Pillai, Reference Uhl-Bien, Pillai, Shamir, Uhl-Bien, Bligh and Pillai2007). Ultimately, both perspectives neglect to explicitly incorporate how followers view their roles in relation to leaders. In response to this omission, Shamir (Reference Shamir, Shamir, Uhl-Bien, Bligh and Pillai2007) called for researchers to ‘reverse the lens’ in leadership studies by considering the role of followers as active and instrumental in the leadership process.

One-way researchers have reversed the lens is through a ‘role-based view of followership,’ which considers how followers and leaders interact in the context of their hierarchical positions (Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe and Carsten2014: 90; Uhl-Bien & Carsten, Reference Uhl-Bien, Carsten, Berson, Katz, Eilam-Shamir and Kark2018). Katz and Kahn (Reference Katz and Kahn1966) define social organizations as systems of roles. Roles are implicit to the structure of the organization as they imply standardized requirements for responsibilities, and as a result govern expected behaviors for specified positions in the organization's hierarchy (Katz & Kahn, Reference Katz and Kahn1966). When role theory is applied to followership, followers derive their expected tasks and behaviors in relation to their leaders from their formal or informal hierarchical position (Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe and Carsten2014). Yet, because of the implicit nature, individual interpretation of one's role and how it should be enacted brings variation into the followership process and can affect the way that followers interact with leaders. By investigating follower interpretation and enactment of their roles, role-based views of followership advance an understanding of how followers work with leaders in ways that contribute to or detract from leadership and organizational outcomes (Carsten et al., Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010; Oc & Bashshur, Reference Oc and Bashshur2013; Sy, Reference Sy2010).

Follower role orientations

Follower role orientations are rooted in this role-based perspective. Role orientations represent an individual's beliefs and expectations regarding the duties and responsibilities inherent in a specified role and how to effectively carry out that role (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018; Parker, Reference Parker2007; Parker, Wall, & Jackson, Reference Parker, Wall and Jackson1997). Follower role orientations are specifically defined as the beliefs that individuals hold about the responsibilities inherent in the follower role and the types of tasks and behaviors that make followers effective while working with leaders (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018; Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe and Carsten2014). Because followers are not treated as a homogeneous group unquestioningly obeying the directives of leaders (Frisina, Reference Frisina2005), they may have different schema for how they should enact their roles. Recent work by Carsten and colleagues propose that prominent follower role orientations can be classified as co-production, passive, or anti-authoritarian (Carsten, Harms, & Uhl-Bien, Reference Carsten, Harms, Uhl-Bien, Lapierre and Carsten2014; Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018).

Co-production role orientation is the belief that followers should engage with the leader to mutually identify and solve problems, as well as help the team to achieve goals. They believe that leadership is a process that is co-created when leaders and followers work together (Shamir, Reference Shamir, Shamir, Uhl-Bien, Bligh and Pillai2007). As such, they see leadership as being impossible without the direct contribution of followers. They are not deterred by the power and authority that leaders have, but rather perceive their own personal power as an accompaniment to leadership; engaged and active followers are necessary to support leadership for organizational outcomes. Individuals with strong co-production orientation believe that followers are responsible for contributing information to leaders and groups, proactively identifying problems and solutions, and constructively interacting with their leader (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018).

Passive role orientation is the belief that there is a high-power distance between leader and followers (Kelley, Reference Kelley1992); these followers believe the leader is responsible for both determining goals and how teams should achieve these goals. Followers with a strong passive role orientation believe that leaders are afforded greater power and authority for good reason and believe that deferring to this power is the best way to enact followership. As a result, passive role orientation leads followers to remain deferent to leaders' knowledge, expertise and ability, and refrain from participating in decision-making (Carsten et al., Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010; Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018). They believe their role is to support the leader by essentially implementing leaders' directives, which reinforces the hierarchical positions of the leader and follower.

Anti-authoritarian role orientation involves the belief that followers should avoid domination by a leader and combat the leader's authority or desire to control them (Bennett, Reference Bennett1988). These individuals resist subordination by attempting to avoid situations where they are forced to take directives from above (Bennett, Reference Bennett1988). They believe that simply complying with the leader gives the leader power over them, but they do not inherently trust the authority afforded by the hierarchical position. As a result, they resist (actively or passively) the power that the leader has as a means of safeguarding themselves from manipulation. These followers often exhibit non-following behaviors in resisting authority. For instance, non-following behaviors may manifest as active disagreement, disapproval, or interruption with the leadership process, or it may manifest as withdrawal or circumventing the current leadership structure (Uhl-Bien & Carsten, Reference Uhl-Bien, Carsten, Berson, Katz, Eilam-Shamir and Kark2018).

In line with prior work on follower role orientations, the orientations are not conceptualized as opposite ends of a continuum (Carsten et al., Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010). Instead, followers may possess beliefs that are high or low on the different orientations. For instance, Carsten, Uhl-Bien, and Huang (Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018: 734) point out that followers may be low in both co-production and passive orientations, ‘believing that they should neither engage nor defer (i.e., non-following).’ Similarly, being moderate on both orientations may mark the belief ‘they should engage to a certain point but defer to the leader's decision no matter what (i.e., active followership)’ (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018: 734). Thus, to fully understand the impact of different follower role orientations on leader-follower relationship and leader outcomes, it is necessary to separately examine each dimension of the follower beliefs.

Further, formative studies in the literature have most frequently focused on co-production and passive orientation as the most prominent behaviors for followers: those that believe they should proactively engage or alternately believe they should defer to a leader's directives (e.g., Baker, Reference Baker2007; Carsten, Harms, & Uhl-Bien, Reference Carsten, Harms, Uhl-Bien, Lapierre and Carsten2014). However, non-following behaviors, which stem from specific anti-authority beliefs, can manifest in behaviors that may overlap with active or passive followers and have distinct effects. Recent work has increasingly shown, in fact, that followers who resist following their leader's authority can play a role in shifting goals or deterring destructive group behaviors (Aghaei et al., Reference Aghaei, Nasr Isfahani, Ghorbani and Roozmand2021; Almeida, Ramalho, & Esteves, Reference Almeida, Ramalho and Esteves2021; Harms et al., Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018). Thus, to fully understand the effects of followers on broader leadership outcomes, it is important to include all ways that followers may shape the leadership process. The role of anti-authoritarian beliefs is an important piece that the current study incorporates in the model.

Psychological closeness

Role orientation beliefs are an important driver of behavior (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018; Parker, Reference Parker2007), and a key component of how followers enact their role in the leadership process is the development of closeness with their leaders (Shamir, Reference Shamir, Uhl-Bien and Ospina2012). Psychological closeness describes the perception of similarities between a leader and follower, which affects the intimacy and connection between them (Antonakis & Atwater, Reference Antonakis and Atwater2002; Shamir, Reference Shamir1995). People tend to form closer psychological relationships when they perceive similarity in attitudes, personality characteristics, or background variables. Psychologically close leaders appear to be more similar to their followers, and as a result, close leaders build stronger interpersonal relations by developing rapport, a strong sense of trust, and higher identification with followers (Michaelis, Stegmaier, & Sonntag, Reference Michaelis, Stegmaier and Sonntag2009; Shamir, Reference Shamir1995). Proximity to a leader may also allow followers to view their superior as more human and fallible, increasing identification and trust (Yagil, Reference Yagil1998).

It is clear from prior work that psychological closeness facilitates leadership behaviors (Antonakis & Atwater, Reference Antonakis and Atwater2002; Waldman & Yammarino, Reference Waldman and Yammarino1999). In general, when leaders are socially and psychologically close with their followers, they are better able to serve as role models and viewed as increasingly approachable (Yagil, Reference Yagil1998). When followers perceive their leaders as close, they are more receptive to individual messaging from their leader, which allows the leader to encourage them to perform more effective workplace behaviors (Yagil, Reference Yagil1998). Psychological closeness can even affect the willingness of followers to follow a leader; it helps to reinforce leadership signals because followers are more likely to attribute positive outcomes to more easily observed and identifiable leadership behaviors (Erickson & Krull, Reference Erickson and Krull1999; Shamir, Reference Shamir1995). Less information is known about how psychological closeness affects leader outcomes. In theory, psychological closeness should increase the likelihood that followers will link leader behaviors to group outcomes because psychological closeness can shift follower attention to the consequences of their interactions (Rim, Hansen, & Trope, Reference Rim, Hansen and Trope2013). However, few studies have looked at this relationship directly.

Relatedly, prior research has established that psychological closeness is meaningful not only for the leader but also affects follower outcomes. For instance, psychological closeness has been shown to increase follower performance and satisfaction (Napier & Ferris, Reference Napier and Ferris1993), improve self-identification and organizational commitment (Gunia, Sivanathan, & Galinsky, Reference Gunia, Sivanathan and Galinsky2009; Story, O'Malley, & Hart, Reference Story, O'Malley and Hart2011), and enhance leaders' ability to influence their followers (Erkutlu & Chafra, Reference Erkutlu and Chafra2016). Psychological closeness also has been shown to help a leader shift the goals and purpose of their followers. For example, Vanderstukken, Schreurs, Germeys, Van den Broeck, and Proost (Reference Vanderstukken, Schreurs, Germeys, Van den Broeck and Proost2019) find that psychological closeness with a subordinate helps supervisors articulate short-term vision but may hinder their ability to align followers with long-term, more abstract goals.

Follower role orientations and psychological closeness

While psychological closeness between leaders and followers affects many aspects of productivity, far less is known about how followers are active participants in building that closeness. In general, most studies assume that psychological closeness is a feature of the leader-follower relationship (Erkutlu & Chafra, Reference Erkutlu and Chafra2016; Roberts & Bradley, Reference Roberts, Bradley, Conger and Kanungo1988; Vanderstukken et al., Reference Vanderstukken, Schreurs, Germeys, Van den Broeck and Proost2019). As a result, psychological closeness is often treated as a predetermined characteristic of the leader-follower context, serving to moderate how leader behaviors impact followers' attitudes and outcomes.

In contrast, this study suggests that follower beliefs about their role are key to the expectations and representations used to determine similarity and engender connection with a leader. Psychological closeness does not have to reflect objective similarities in characteristics, but it may be generated by the perceptions of alignment between a leader and follower (Antonakis & Atwater, Reference Antonakis and Atwater2002; Shamir, Reference Shamir1995). This perception of overlap in roles, attitudes, and characteristics are necessarily constructed by what the follower believes their role and responsibilities should be. In this way, psychological closeness can shape the boundaries between the follower and leader and, as a result, can lead individuals to experience and behave more consistently with their conceptualization of leader-follower roles (Gunia, Sivanathan, & Galinsky, Reference Gunia, Sivanathan and Galinsky2009).

In general, follower role orientations can affect psychological closeness in two ways. First, followers will behave in accordance with their role orientations. Differences in how they interact shapes the leader-follower relationship in terms of engagement and access. Second, their beliefs about how they should be enacting their role changes how they conceptualize their similarity with their leader. When followers see their role as more similar, leaders appear to be more similar to their followers and followers will identify with them more. Thus, the development of closeness varies depending on the specific follower role orientation.

Followers who display high co-production role orientations frequently collaborate with their leaders in problem identification and problem-solving (Carsten et al., Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010). Their high engagement with proactivity and communication with the leader affords them the opportunity to form deep and meaningful connections with the leader (Napier & Ferris, Reference Napier and Ferris1993). Further, when followers believe that their role is to mutually solve problems and work together, they are more likely to see overlap between themselves and their leader, which reinforces their similarity. Therefore, when followers are high in co-production orientation, they believe there's an overlap in leader-follower roles, perform leader-like behaviors such as problem-solving, and act as active contributors to the group, which increases their psychological closeness to their leader.

Hypothesis 1a: Co-production role orientation is positively related to the development of psychological closeness with a leader.

Passive followers on the other hand, usually refrain from engaging with the leaders. They keep interactions at a minimum, primarily in responding to leader's orders and avoiding an active role in the process. As a result, passive followers miss the opportunities to develop intimacy and connectedness with the leaders (Carsten et al., Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010; Napier & Ferris, Reference Napier and Ferris1993). Similarly, followers who believe that their role is to defer to leaders' decisions are less likely to see overlap in their roles with the leader. Leaders then seem less identifiable and their attributes and behaviors less aligned with the follower, increasing distance. Therefore, when followers are high in passive orientation, they adhere to stricter hierarchical roles, which leads them to believe there is not a similarity in the characteristics or attributes necessary for a leader and follower. As a result, these followers do not form close relationships with their leader or overlap in their roles, which decreases the psychological closeness between the leader and follower.

Hypothesis 1b: Passive role orientation is negatively related to the development of psychological closeness with a leader.

Anti-authoritarian followers also lack exposure to their leaders, for different reasons than passive followers. Because they tend to be suspicious of their leaders, anti-authoritarian followers actively avoid opportunities for interaction, collaboration, and decision-making with the leaders. As a result, they are not likely to be close to the leader as they evade engagement and reduce involvement (Carsten et al., Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010). Therefore, when followers are high in anti-authoritarian orientation, they avoid adherence to traditional, hierarchical roles. With a tendency to promote non-following behaviors, anti-authoritarian followers perceive little overlap in the characterizations and behaviors of leaders and followers, which creates a more antagonistic relationship with their leader. As a result, anti-authoritarian followers decrease in psychological closeness with their leaders.

Hypothesis 1c: Anti-authoritarian role orientation is negatively related to the development of psychological closeness with a leader.

Leader-Member Exchange (LMX)

Because leadership involves a bidirectional process between leaders and followers, the development of the leader-follower relationship must include how follower beliefs drive their interactions and exchanges (Graen & Uhl-Bien, Reference Graen and Uhl-Bien1995; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Loi, Cai and Liden2019). Although follower personality has been previously shown to influence the leader relationship (Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer, & Ferris, Reference Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer and Ferris2012), the individual differences in how followers see and enact their roles may also impact the quality of the leadership relationship. Followers' assessment of their roles can provide important insights into how they approach the leader-follower dynamic.

One important aspect of this dynamic is the leader-member exchange relationship (LMX), which represents followers' assessment of leaders' contribution to the relationship through social exchanges (Liden & Maslyn, Reference Liden and Maslyn1998; Liden, Sparrowe, & Wayne, Reference Liden, Sparrowe and Wayne1997). Relationships with high-quality exchanges are typically associated with concern and support, whereas low-quality relationships are restricted to perfunctory duties and expectations (Graen & Uhl-Bien, Reference Graen and Uhl-Bien1995). High-quality relationships develop through social exchange of resources between the two parties and generate future obligations to return beneficial behaviors (Blau, Reference Blau1964; Gouldner, Reference Gouldner1960). Consistently, leaders who experience the benefits of having a close relationship can feel obligated to reciprocate in terms of carrying out actions that benefit their followers (Blau, Reference Blau1964; Gouldner, Reference Gouldner1960). For example, leaders may reciprocate with close followers by going beyond their formal duties to elevate the group's work and to act in ways to maximize long-term gains not only for themselves but for the entire work group (Avolio & Bass, Reference Avolio and Bass1991).

Follower role orientations and LMX

Followers cognitively generate expectations for the quality of social exchanges in a leader-follower relationship (Coyle & Foti, Reference Coyle and Foti2015; Lord & Shondrick, Reference Lord and Shondrick2011; Shondrick, Dinh, & Lord, Reference Shondrick, Dinh and Lord2010). These expectations are represented through knowledge structures such as schemas (Lord & Dinh, Reference Lord and Dinh2014; Lord & Shondrick, Reference Lord and Shondrick2011). Role orientations are crucial schemas because they prime expectations regarding a positive leader-follower dynamic. Specifically, role orientations represent interpersonal scripts called relational schemas, which specify characteristics and within-role behavior of those involved in a high-quality relationship (Baldwin, Reference Baldwin1997). Additionally, relational schemas within role orientations represent generalized expectations of how the self and other experience the relationship (Baldwin, Reference Baldwin1992, Reference Baldwin1997). Thus, followers' perceptions of LMX quality should vary as a function of their specific role orientation.

The specific content of role orientations, however, is also crucial because different role orientations could differentially contribute to the quality of the relationship with the leader (Dienesch & Liden, Reference Dienesch and Liden1986). Followers who have high co-production role orientation tend to work actively with the leader, co-partnering to help them identify problems and develop mutual understanding. These followers are more likely to assume relational schemas that will manifest in high-quality interaction with the leader (Baldwin, Reference Baldwin1992, Reference Baldwin1997). In line with exchange theory, such role orientations will create expectations and obligations for the leader to give back to the relationship (Blau, Reference Blau1964; Gouldner, Reference Gouldner1960). This will manifest in followers' contribution towards leaders work goals (e.g., performing work beyond what is specified followers' job description), liking for the leader, leaders' loyalty towards a follower, and professional respect for the leader is enhanced.

Hypothesis 2a: Co-production role orientation is positively related to the development of high-quality LMX.

Alternatively, followers may construe relational schema in their role orientations as more instrumental (Liden, Sparrowe, & Wayne, Reference Liden, Sparrowe and Wayne1997), in which social relationships are governed by the primary intentions of meeting an objective goal. In this case, follower intentions are restricted to meeting the needs of job descriptions. Because passive followers usually limit interactions to responding to leader's orders and avoid an active role in the process, these individuals are largely disengaged from the leadership process while unquestionably carrying out tasks. As a result, they remain absent from the opportunities of partnering with the leader in decision making and problem solving (Carsten et al., Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010). Thus, passive role orientation, due to a more instrumental model for guiding relationships, will negatively affect LMX.

Hypothesis 2b: Passive role orientation is negatively related to the development of high-quality LMX.

Finally, anti-authoritarian followers are suspicious of their leaders and may actively avoid opportunities for interaction, collaboration, and decision-making as such (Gregory, Reference Gregory1955). Unlike followers who are merely passive, anti-authoritarian followers may resist a traditional leadership structure, which would lead them to actively resist activities that support or legitimize a leadership relationship. So, they may remain withdrawn but with the goal of deterring productive leadership behaviors. As a result, these types of followers are not likely to develop high LMX as they evade engagement and reduce involvement (Carsten et al., Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera and McGregor2010).

Hypothesis 2c: Anti-authoritarian role orientation is negatively related to the development of high-quality LMX.

Follower role orientations and leader outcomes

Research has begun to investigate how leaders react to how different followers enact their roles. Most prominently, researchers have investigated the effects of co-production or proactive follower orientations; however, the findings are mixed (Benson, Hardy, & Eys, Reference Benson, Hardy and Eys2016; Dulebohn et al., Reference Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer and Ferris2012; Grant, Parker, & Collins, Reference Grant, Parker and Collins2009; Sun & van Emmerik, Reference Sun and van Emmerik2015). Although some research suggests that leaders are generally appreciative of followers who are proactive in their roles (e.g., Dulebohn et al., Reference Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer and Ferris2012), others suggest that when leader-follower roles are defined, co-production beliefs and actions may elicit negative leadership outcomes (e.g., Benson, Hardy, and Eys, Reference Benson, Hardy and Eys2016). Far less is known about how passive or anti-authoritarian followers may affect the goals and effectiveness of the leader. Studies into non-proactive followers tend to be leader- or follower-centric: focused on follower outcomes and perceptions in the face of leader behaviors (e.g., Almeida, Ramalho, and Esteves, Reference Almeida, Ramalho and Esteves2021).

Building upon this leadership literature, this research extends the focus beyond follower outcomes to examine how follower role orientations help followers shape the direction of the group through their influence on the leader and contribute to how well the leader serves the group through leader effectiveness.

Influence on leader (Study 1)

Role theory positions followers as key agents in influencing leader outcomes, and psychological closeness plays an important mechanism through which followers are able to exercise influence on leaders (Oc & Bashshur, Reference Oc and Bashshur2013; Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe and Carsten2014). Psychological closeness has been shown to promote leader influence because closeness allows leaders to adjust their appeal appropriately (van Houwelingen, Stam, & Giessner, Reference van Houwelingen, Stam and Giessner2017); the extent that a follower can translate closeness into influence over a leader also will stem from the same dynamics (Oc & Bashshur, Reference Oc and Bashshur2013). Increased psychological closeness results from perceived similarity on rank, power, social standing, and values (Antonakis & Atwater, Reference Antonakis and Atwater2002; Napier & Ferris, Reference Napier and Ferris1993). When followers perceive a high psychological closeness, they experience feelings of attachment and connection that help build trust and rapport. For example, a follower who feels close to their leader may be more able to identify the leader's strengths weaknesses, values, attitudes, and beliefs (Antonakis & Atwater, Reference Antonakis and Atwater2002). This similarity enhances the degree of intimacy and social contact which facilitates identification with the leader, enables followers to build rapport, thus making leaders more receptive to followers' impact (Oc & Bashshur, Reference Oc and Bashshur2013).

Previous studies have shown favorable outcomes of psychological closeness such as high job performance (Crouch & Yetton, Reference Crouch and Yetton1988; Kacmar, Witt, Zivnuska, & Gully, Reference Kacmar, Witt, Zivnuska and Gully2003), follower job satisfaction (Baird & Diebolt, Reference Baird and Diebolt1976), and relationship quality (Story, Youssef, Luthans, Barbuto, & Bovaird, Reference Story, Youssef, Luthans, Barbuto and Bovaird2013). This closeness with their leader gives followers a strategic advantage in the leadership influencing process (Antonakis & Atwater, Reference Antonakis and Atwater2002), more able to observe and understand leaders' thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors (Shamir, Reference Shamir, Uhl-Bien and Ospina2012). In sum, followers whose role orientations help promote a psychological closeness (as opposed to distance) with their leaders are strategically placed in the relationship to establish better rapport with the leader, understand leader goals and directions, and exert more influence on the leader.

Hypothesis 3a: Co-production role orientation will have an indirect, positive effect on influence on leader through psychological closeness.

Hypothesis 3b: Passive role orientation will have an indirect, negative effect on influence on leader through psychological closeness.

Hypothesis 3c: Anti-authoritarian role orientation will have an indirect, negative effect on influence on leader through psychological closeness.

Leader effectiveness (Study 2)

Leader effectiveness is a critical assessment that encompasses how leaders meet the requirements of their job, as well as their capacity to go beyond job requirements in service of the group or organization (Avolio & Bass, Reference Avolio and Bass1991). Followers' perceptions of leader effectiveness can shed important insight into how the leadership process unfolds (Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe and Carsten2014). First, follower perceptions can provide a perspective of whether the leadership process actually served those who are central to the process. By examining leader effectiveness from a follower's perspectives, a narrow, leader-centric view of leader accomplishments (Gooty et al., Reference Gooty, Connelly, Griffith and Gupta2010) can be avoided. In addition, examining the impact of follower role orientation on leader effectiveness creates a more holistic view by representing not only how followers can influence their leader's work, but also how leaders in turn serve their group (Uhl-Bien et al., Reference Uhl-Bien, Riggio, Lowe and Carsten2014).

Role orientations can, as with influence on leader, affect leader effectiveness through the development of psychological closeness. Therefore, followers' ability to affect leaders' outcomes may flow through how well their role orientation beliefs allow them to develop a close and intimate connection with their leaders. Followers with co-production role beliefs will proactively engage with their leaders and seek out regular interactions with them. This type of engagement and identification helps create reciprocal insight and dedication into group needs (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018) by increasing closeness. Further, when followers are proactively engaged, they are more active in helping to identify and achieve goals and see leader enactment as being highly effective. In contrast, individuals holding passive role orientations will minimally communicate with their leaders. As a result, they have fewer intimate relationships, less connection with their leader, and reduced insight into their motivations (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018), which offers fewer insights into whether a leader is serving group needs. In addition, leaders will not feel the need to engage beyond their directive input to the group. Similarly, followers with anti-authoritarian role orientations will also keep a distance from their leaders. Because of this, followers are unlikely to engage with leaders in everyday functions such as decision making (Carsten, Harms, & Uhl-Bien, Reference Carsten, Harms, Uhl-Bien, Lapierre and Carsten2014). As anti-authoritarian followers work against subordination and are psychologically distant, leaders may be skeptical of their motivations and concentrate more on elevating their own outcomes than the group.

In addition, the effect of follower role orientations in shaping LMX relationships can also affect leader effectiveness (Dulebohn et al., Reference Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer and Ferris2012; Ilies, Nahrgang, & Morgeson, Reference Ilies, Nahrgang and Morgeson2007; Yammarino & Dansereau, Reference Yammarino and Dansereau2008). Followers' support, respect, and contributions create an obligation for the leader to adequately meet job-related work needs and the job-related needs of the work unit. The extent to which a leader meets those needs represents leader effectiveness (Avolio & Bass, Reference Avolio and Bass1991). Previous studies have found a positive relationship between LMX and leader effectiveness (Brouer, Douglas, Treadway, & Ferris, Reference Brouer, Douglas, Treadway and Ferris2013; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Guillaume, Thomas, Lee and Epitropaki2016). When leaders experience followers' liking for the leader, contribution to leaders' goals, and professional respect, it creates an obligation to return such favorable treatment. This incentivizes leaders to go beyond to fulfill their followers' needs in ways such as enacting extra-role behaviors to represent their groups to higher authorities or relying on their followers to help make better decisions or solve problems (Avolio & Bass, Reference Avolio and Bass1991). In sum, followers whose role orientations help build both psychological closeness and high-quality LMX with their leaders are better able to understand and contribute to the group goals and tasks and, ultimately, increase a leader's effectiveness.

Hypothesis 4a: Follower co-production role orientation will have a positive indirect effect on leader effectiveness through psychological closeness and LMX.

Hypothesis 4b: Follower passive role orientation will have a negative indirect effect on leader effectiveness through psychological closeness and LMX.

Hypothesis 4c: Follower anti-authoritarian role orientation will have a negative indirect effect on leader effectiveness through psychological closeness and LMX.

Overview of the current research

This research is carried out across two studies. In study 1, the extent to which follower role orientations impact psychological closeness from followers' perspective and, subsequently, influence how leaders work with follower was explored, using a longitudinal investigation of entrepreneur teams. This approach provides an ideal setting for exploring how psychological closeness builds in newly formed leader-follower relationships as they work to accomplish comparable competition tasks. Results from study 1 suggest follower role orientations have differential effects on how followers perceive closeness with their leader, which primes their expectations for the relationship and leader-directed influencing. While closeness is one indicator of a relationship, leader-follower exchange quality may also be primed by role orientations. Therefore, study 2 extends the model from study 1 to examine how role orientation influences leaders not only through psychological closeness, but also concurrently through exchange quality of the leader-follower relationship. Study 2 uses a panel data of individuals working across industries, which allowed the testing of the model with leader-follower relationships that were already formed and were less transient than the short-term entrepreneur teams. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of hypothesized relationships.

Method (Study 1)

Sample and procedure

Data were collected at an entrepreneurship competition held at a public university in the Northeastern United States. Participation in the competition was voluntary and open to undergraduate, graduate, and recent alumni of the university. As part of the competition, teams identified a venture to develop into a real service, product, or business. Throughout the competition, organizers provided teams with guidance in developing a concept proposal, which was then judged by a panel of entrepreneurs and industry experts who awarded prize money to the top teams. This setting was well-suited to study the input of different types of followers in a meaningful project. Although each team had a designated leader, the team had latitude in the extent that members took a role in developing, presenting, and implementing the solution. Therefore, individual differences in the beliefs and actions of the followers on the team created variation in their relationships with their team leader and in how much they influenced the group outcomes.

Surveys were distributed at two times. The first survey was distributed prior to the competition, after teams submitted an application to participate where they designate their leader and team members. The second survey was distributed at the end of the competition, after teams had turned in their final project plans but prior to judging. At time 1, members were asked to rate their follower orientation and demographics. At time 2, members were asked to rate their psychological closeness with the leader and leaders were asked to rate the extent that each member influenced or changed their work.

Participation in the study was completely voluntary and was open to anyone who applied to the entrepreneurship competition. Investigators emailed competition participants with a link to a Qualtrics survey maintained by the investigators after they submitted their application to the competition (time 1) and after they had submitted their final project plans to the competition organizers (time 2). Competition organizers were not informed of which participants responded to the survey. For completing the surveys, the participants were given $5 gift cards to Starbucks. The methods were approved by the university Institutional Review Board (protocol: 19-006-EVA-EXM).

The final sample consisted of 43 followers (74% response rate) placed on 19 teams (69%). Of the 28 eligible teams with leaders and followers, 22 teams participated in the surveys (79% participation). Three were ultimately excluded because the leaders did not respond with final influence ratings for the followers. The participants were all different levels in their education with freshmen (18.6%), sophomores, (9.3%), juniors (16.3%), seniors (9.5%), and graduate students (11.6%). Participants also represented numerous disciplines (30.2% Engineering, 27.9% Health Sciences, 23.3% Business, 11.6% Sciences, 2.3% Humanities, 4.7% Undisclosed). On average, teams had 3.30 people, with 55% male. Followers had on average 2.98 years of experience with their leaders.

Measures

All items were measured on a 6-point scale (1-strongly disagree to 6-strongly agree) unless otherwise noted.

Co-production role orientation

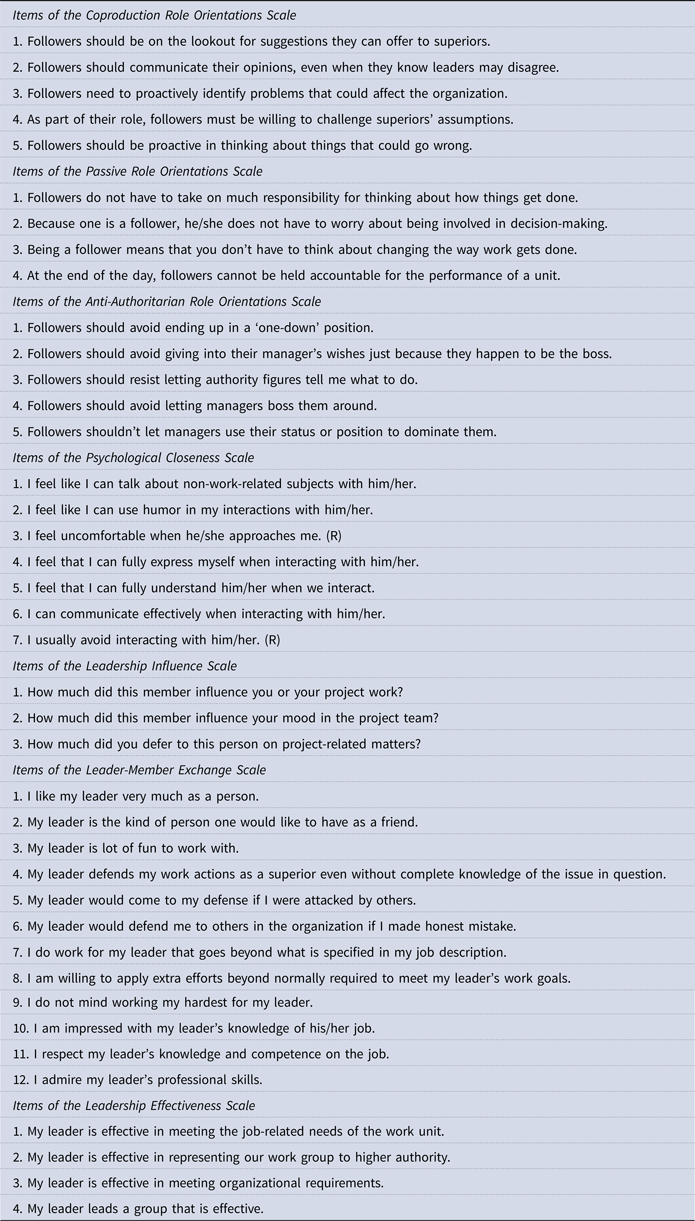

Co-production role orientation was measured using a 5-item scale from Carsten, Uhl-Bien, and Huang (Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018). Items included ‘Followers should communicate their opinions, even when they know leaders may disagree’, and ‘Followers need to proactively identify problems that could affect the organization’ (α = .89).

Passive role orientation

Passive role orientation was measured using a 4-item scale from Carsten, Uhl-Bien, and Huang (Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018). Items included ‘Followers do not have to take on much responsibility for thinking about how things get done’ and ‘Because one is a follower, he/she does not have to worry about being involved in decision-making’ (α = .89).

Anti-authoritarian role orientation

Anti-authoritarian role orientation was measured scale using a 6-item scale from Carsten, Harms, and Uhl-Bien (Reference Carsten, Harms, Uhl-Bien, Lapierre and Carsten2014). Items included ‘Followers should avoid accepting their manager's authority’ and ‘Followers should avoid giving into their manager's wishes just because they happen to be the boss’ (α = .72).

Psychological closeness

Psychological closeness was measured using a 7-item scale from Torres and Bligh (Reference Torres and Bligh2012) on a 7-point scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree). Items included ‘I feel that I can fully express myself when interacting with him/her’ and ‘I feel that I can fully understand him/her when we interact’ (α = .85).

Influence on leader

The extent that each follower influenced the leader during the project was measured using a dyadic rating approach consistent with Bunderson, Van Der Vegt, Cantimur, and Rink (Reference Bunderson, Van Der Vegt, Cantimur and Rink2016). Leaders rated three items to indicate the extent to which each team member ‘influenced you or your project work’ or to which ‘you deferred to this person on project-related matters’ during the project. Each teammate was rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (a lot). The three items were averaged to obtain one dyadic rating for each team member's influence over the leader over the course of the project (α = .93).

Controls

Leader-follower dynamics can be affected by variables such as gender and tenure working with the leader (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018; Qin, Chen, Yam, Huang, & Ju, Reference Qin, Chen, Yam, Huang and Ju2020; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Loi, Cai and Liden2019). Prior work has shown that the gender of the follower may affect the extent that they work with leaders and can affect team member influence on project teams (Ridgeway & Berger, Reference Ridgeway and Berger1986). Similarly, when leaders are familiar with team members and have worked with them before, they may be more likely to be influenced by them (Bunderson, Reference Bunderson2003). Therefore, a control for how long (in months) each team member had worked with the team leader was included. In addition, team size varied (ranging from 3 to 7 people), which has been shown to influence the extent that a follower could interact with a leader (Ancona & Caldwell, Reference Ancona and Caldwell1992). Thus, data analysis was performed controlling for the gender of the individual (coded 0 for male and 1 for female), their experience with the leader (in months), and, at the team-level, controlled for team size.

The hypotheses were first tested without any controls, and then theoretically relevant control variables and demographics that would affect the findings were assessed (Becker, Reference Becker2005; Spector & Brannick, Reference Spector and Brannick2011). No combination of controls that changed the direction or statistical significance of the findings was found, so those that had theoretical importance were included.

Results (Study 1)

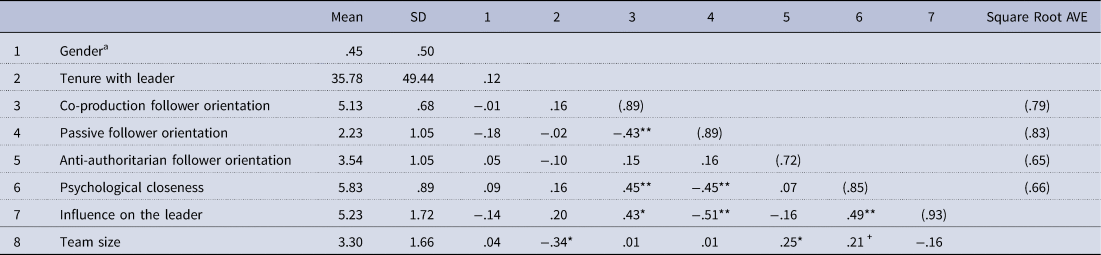

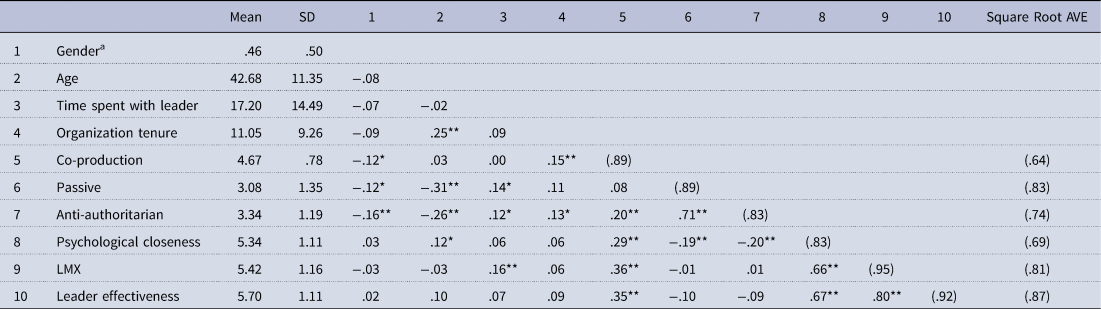

Descriptive statistics for study 1 variables appear in Table 1.

Table 1. Correlations and descriptive statistics in study 1

SD is standard deviation. Statistics above the dashed line are at the individual-level and below the dashed line are at the team-level.

aMale = 0; Female = 1

+ p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01 (two-tailed)

Notes. N = 43 for follower variables; N = 19 for team variables. Cronbach's alphas are reported in parentheses along the diagonal.

Common Method Variance (CMV)

Procedural and statistical methods were adopted to mitigate and evaluate the potential influence of common method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2012). In the data collection phase, procedural remedies were adopted. Specifically, measures reported by the same individuals were temporally separated, such that the independent variables were measured at time 1 and the mediator variable was measured at time 2. In addition, measures at time 2 were obtained from different sources/raters; the predictor variable was assessed by the followers and the outcome variable was assessed by the leaders in the teams. We also performed two statistical remedies to test the common method bias. First, a single-factor procedure based on CFAs was performed (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). The fit of the single-factor model in which all items loaded onto one factor to address the problem of common method variance was examined. The results showed that the single-factor model was highly nonsignificant and thus can be rejected (CFI = .41, TLI = .34, RMSEA = .22, SRMR = .16). Second, another well-documented set of statistical remedies for common method variance is classified as partial correlation techniques (Lindell & Whitney, Reference Lindell and Whitney2001; Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). A marker variable was identified that does not theoretically or empirically relate to the study variables (communal orientation); none of the significant correlations among variables turned nonsignificant after controlling for this variable. These results indicate that the relationships between the study variables are not significantly biased by CMV, because all partial correlations remained unchanged while controlling for the marker variable (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003).

Study 1 was designed to be an exploratory study, so there was only a small sample size (N = 43). Problems may arise from small sample size when running confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (Kyriazos, Reference Kyriazos2018; West, Finch, & Curran, Reference West, Finch, Curran and Hoyle1995). Because the model does not face non-convergence, the parameter estimates are likely to be unbiased (Chen, Bollen, Paxton, Curran, & Kirby, Reference Chen, Bollen, Paxton, Curran and Kirby2001), so Marsh and Hau (Reference Marsh and Hau1999) recommend, to ensure distinctiveness of variables, that all factor loadings have standardized coefficients greater than .70 and to run an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to examine cross-loading items. This model met both recommendations. Finally, the Fornell and Larcker (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981) method was applied to check for convergent and discriminant validity. The square root of the average variance extracted for each latent construct is in the last column of Table 1. As recommended, all the estimates exceed the correlation between the factors comprising each pair.

Hypothesis testing

Multilevel modeling (MLM) was used to test hypothesis 1a-1c because individuals were on interdependent teams (Raudenbush & Bryk, Reference Raudenbush and Bryk2002). MLM is recommended for nested data, such as individuals working in a group, because it explicitly models the interdependence between the individual (level-1) and the group (level-2) (Raudenbush & Bryk, Reference Raudenbush and Bryk2002). To validate the use of MLM, the amount of variance in the outcome variable, leader influence, explained by variation among teams, was estimated (Hofmann, Reference Hofmann1997). A null (one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]) model was tested without predictor variables, in order to estimate the amount of variance in influence predicted by variation among teams. We estimated the amount of between-team variance in influence by examining the Level-2 residual variance of the intercept (τ 00), by examining the Level-1 residual of variance (σ2), and by computing ICC(1). For influence on leader, the residual variance of the intercept was significant (τ 00 = .97, p < .001), the level-1 residual of variance was significant (σ2 = 1.95) and 33% of the variance was explained by group differences (ICC(1) = .97/(1.95 + .97) = .33). Therefore, although all hypothesized variables and outcomes pertain to the individual level, it is appropriate to use MLM to account for the non-independence due to the variance between competition teams.

All predictor variables, except gender, were mean-centered to reduce multicollinearity. The team-level control variable, size, was included at level-2 of the model. The MLmed macro (Hayes & Rockwood, Reference Hayes and Rockwood2020) was used to test hypotheses 3a–3c which tests the significance of the indirect effect of role orientation on influence through psychological closeness. The MLmed macro is an SPSS macro similar to the PROCESS macro (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2004) except that the MLmed macro is able to fit models that have variables at multiple levels of analysis and can account for variance due to the nested structure of the data (i.e., individuals in interdependent groups).

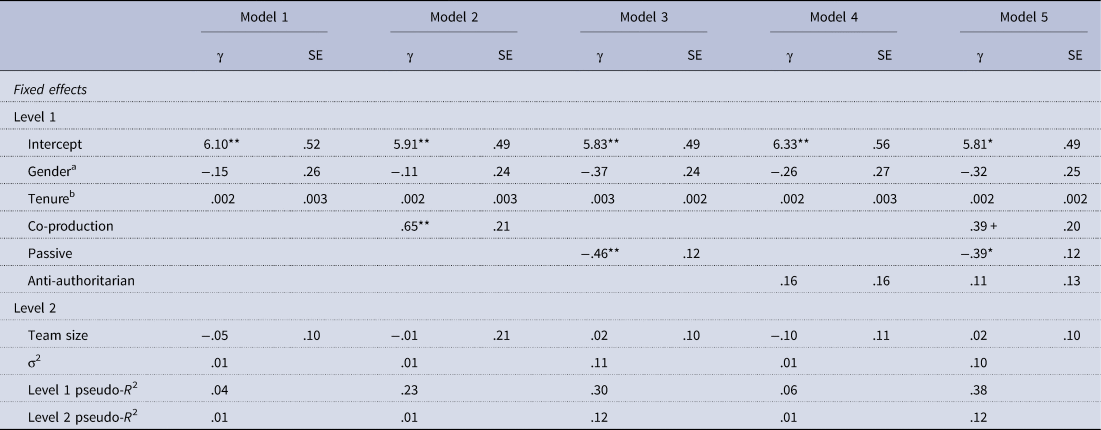

Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1c predicted that role orientations would be related to the psychological closeness a follower develops with their leader. The models to test the direct links between role orientations and psychological closeness are presented in Table 2. As predicted co-production role orientation was positively related to psychological closeness (Model 2, Co-production: γ = .65, p = .004), while passive role orientation was negatively related to psychological closeness (Model 3, Passive: γ = −.46, p < .001). Thus, hypotheses 1a and 1b were supported. Anti-authoritarian role orientation was not significantly related (Model 4, Anti-authoritarian: γ = .16, p = .329), so hypothesis 1c was not supported.

Table 2. Multilevel regressions predicting psychological closeness in study 1

a Male = 0; Female = 1.

b Months.

* p < .05; ** p < .01 (two-tailed)

Notes. N = 43 leader-follower dyads;

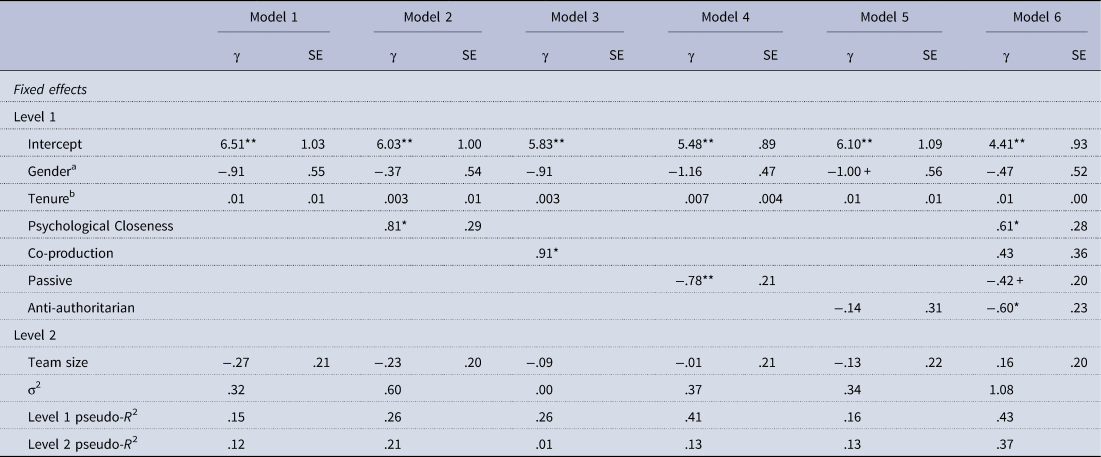

Hypotheses 3a, 3b, and 3c predicted that role orientations would be related to influence on the leader through psychological closeness. To test the indirect effects of co-production, passive, and anti-authoritarian role orientation on influence through psychological closeness, the direct effects of the links were verified. Table 3 shows the effect of the role orientations on influence on leader (Model 3, Co-production: γ = .91, p = .055; Model 4, Passive: γ = −.78, p = .001; Model 5, Anti-authoritarian: γ = −.14, p = .630). Psychological closeness also had a positive effect on the influence on a leader (Table 3, Model 2: γ = .81, p = .011). The significance of the indirect effect of co-production role orientation through psychological closeness on leader influence (β = .68, p = .021) was tested. The results indicated that the indirect effect of co-production follower orientation was significant because the 95% confidence interval (CI = .19, 1.34) did not contain zero. Thus, hypothesis 3a was supported. The indirect effect of passive follower orientation on leader influence through psychological closeness (β = −.33, p = .056) was significant because the 95% confidence interval (CI = −.70, −.05) did not contain zero. Thus, hypothesis 3b was supported. The indirect effect of anti-authoritarian follower orientation through psychological closeness indicated that the indirect effect of anti-authoritarian follower orientation was not significant and the 95% confidence interval (CI = −.18, .49) contained zero. Thus, hypothesis 3c was not supported.

Table 3. Multilevel regressions predicting influence on leader in study 1

a Male = 0; Female = 1.

b Months.

* p < .05; ** p < .01 (two-tailed)

Notes. N = 43 leader-follower dyads.

Additional analyses were conducted to check if endogeneity was an issue in the data; endogeneity is an issue if the covariance of the errors of the mediator and dependent variable is significant. As recommended, a two-stage least square estimator was used to check for the robustness of the OLS results (Antonakis, Bendahan, Jacquart, & Lalive, Reference Antonakis, Bendahan, Jacquart and Lalive2010). A structural equation model with maximum likelihood was ran in STATA 16 to test for endogeneity (StataCorp, 2019). The results revealed that the covariances of the error terms of psychological closeness and influence for hypothesis 3a (−.03; CI = −1.17, 1.11), hypothesis 3b (−.34; CI = −1.35, .66), and hypothesis 3c (.19; CI = −.69, 1.09) were all non-significant, suggesting endogeneity did not bias the results, and that the OLS estimates were trustworthy.

Method (Study 2)

Sample and procedure

Data for study 2 were collected using a sample of full-time employees recruited through the Centiment platform, which recruits and pays a preexisting pool of employees from a variety of industries. The Centiment platform was chosen because it has been shown to provide a heterogeneous group of participants whose psychometric quality is comparable or even better than that of organizational samples, when proper precautions such as deleting non-purposeful responses are used (Behrend, Sharek, Meade, & Wiebe, Reference Behrend, Sharek, Meade and Wiebe2011; Piccolo & Colquitt, Reference Piccolo and Colquitt2006). Participants were included in the survey if they indicated they work at least 30 hours a week, work as part of a team, and have a direct supervisor. These characteristics were broad enough to capture variations in role orientations, closeness, LMX, and leader effectiveness ratings. If participants met the criteria, they were provided with a Qualtrics survey link to respond.

Data were collected at two different points in time. At time 1, members were asked to report their role orientations (co-production, passive, anti-authoritarian). At time 2, three months later, members provided information about the psychological closeness, leader-member relationship, and leader effectiveness. For the survey, 895 participants responded at time 1. All members who participated at time 1 were contacted at time 2; 498 participants responded (56% response rate). Participants were compensated $1.50 for completing the survey at time 1 and an additional $1.50 for completing the survey at time 2. Respondents who completed only time 1 were compared to those completing both time 1 and time 2, and there were no significant differences in demographics (age, gender, tenure) or role orientations between the two groups. In addition to temporal separation of measures, checks were included in the study to ensure attentiveness and quality of responses (e.g., Behrend et al., Reference Behrend, Sharek, Meade and Wiebe2011). Specifically, participants who did not respond to at least 95% of the survey were excluded from the sample, and items were used to gauge inattentive responding (Huang, Bowling, Liu, & Li, Reference Huang, Bowling, Liu and Li2015) including questions like ‘I have never used a computer.’

After eliminating respondents who did not meet these criteria and matching data collected at times 1 and 2, the final sample included a total of 318 full-time workers residing within the United States. Participants were majority Caucasian (81.6%) males (54%) with a mean age of 42.67 years (SD = 11.35). The majority had completed a bachelor's degree (31.8%) or a professional degree (20.1%). Average organizational tenure was 11.05 years. The average tenure reported with the leader was 7.19 years and reported 17 hours as average interaction with the leader in a week. Further participants worked on an average 43.52 hours (SD = 8.73) in a week and represented various industries such as construction (5.7%), banking (3.1%), electronics (3.1%), food and beverage (5%), retail (7%), government (7.2%), health care (10.4%), manufacturing (6.3%), telecommunications (3.1%), financial non-bank (4.1%), and education (4.4%).

Measures

All items were measured on a 6-point scale (1-strongly disagree to 6-strongly agree) unless otherwise noted.

Co-production role orientation

As in study 1, co-production role orientation was measured using the 5-item scale (α = .89) from Carsten, Uhl-Bien, and Huang (Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018).

Passive role orientation

As in study 1, passive role orientation was measured using the 4-item scale (α = .89) from Carsten, Uhl-Bien, and Huang (Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018).

Anti-authoritarian role orientation

As in study 1, anti-authoritarian role orientation was measured using the 6-item scale (α = .83) from Carsten, Harms, and Uhl-Bien (Reference Carsten, Harms, Uhl-Bien, Lapierre and Carsten2014).

Psychological closeness

As in study 1, psychological closeness was measured using the 7-item scale (α = .83) from Torres and Bligh (Reference Torres and Bligh2012).

Leader-member exchange

LMX was measured by the 12-item LMX-MDM scale (Liden & Maslyn, Reference Liden and Maslyn1998). Items included ‘I like my supervisor very much as a person’ and ‘My supervisor would come to my defense if I were ‘attacked’ by others.’ All items were assessed on a 7-point scale (1-strongly disagree to 7-strongly agree). The LMX-MDM is a multidimensional measure of LMX quality (affect, loyalty, contribution, and professional respect). However, this study focused on the overall quality of the leader-member relationship, so this was averaged into one scale (α = .95).

Leader effectiveness

Leader effectiveness was measured with a 3-item scale (α = .93) from Avolio and Bass (Reference Avolio and Bass1991). An example item rated by followers was ‘My leader is effective in helping to meet the job-related needs of the work unit.’

Controls

As in study 1, a number of demographics that have been shown to affect leader-follower relationship dynamics were controlled for (Carsten & Uhl-Bien, Reference Carsten and Uhl-Bien2012; Thomas, Whitman, & Viswesvaran, Reference Thomas, Whitman and Viswesvaran2010). Based on prior studies of followership, gender, race, education, and age were included (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, & Huang, Reference Carsten, Uhl-Bien and Huang2018; Qin et al., Reference Qin, Chen, Yam, Huang and Ju2020; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Loi, Cai and Liden2019). Prior work has also suggested that when leaders work more frequently with followers, it may increase their opportunity to build their relationship, regardless of follower role orientations (Maslyn & Uhl-Bien, Reference Maslyn and Uhl-Bien2001; Popper & Mayseless, Reference Popper and Mayseless2007; Thomas, Whitman, & Viswesvaran, Reference Thomas, Whitman and Viswesvaran2010). Therefore, controls to account for tenure, including how long participants had worked in their organization (in years), tenure working with the leader (in years), and how frequently followers worked with their leaders (in hours per week), were also included. Models were run with and without controls and no combination changed the direction or significance of the findings.

Results (Study 2)

Descriptive statistics for the study 2 variables appear in Table 4.

Table 4. Correlations and descriptive statistics from study 2

aMale = 0; Female = 1;

* p < .05; ** p < .01 (two-tailed)

Notes. N = 318. Cronbach's alphas are reported in parentheses along the diagonal. SD is standard deviation.

Common method variance

Procedural and statistical methods were adopted to mitigate and evaluate the potential influence of common method bias (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2012). In the data collection phase, temporal separation was used to collect the predictor and outcome variables, as the data were collected from a single source. In addition, the order of the questionnaire items was randomized. Two statistical remedies to test the common method bias were also performed. First, we performed a single-factor procedure based on CFAs (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003), and examined the fit of the single-factor model in which all items loaded onto one factor to address the problem of common method variance. The results showed that the single-factor model was highly nonsignificant and thus can be rejected (CFI = .59, TLI = .57, RMSEA = .14, SRMR = .15). Second, similar to study 1, partial correlations between a marker and these study variables (Lindell & Whitney, Reference Lindell and Whitney2001; Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003) were examined. For this study, followers' race was used as a marker variable that does not theoretically or empirically relate to other variables. None of the partial correlations changed after controlling for race, suggesting that the relationships are not significantly biased by CMV.

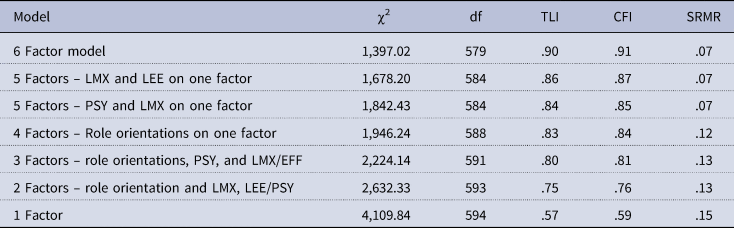

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to ensure the distinctiveness of the variables. As shown in Table 5, the proposed six-factor model showed a good overall measurement fit with χ2(579) = 1397.02, CFI = .91, TLI = .90, SRMR = .07). All the factor loadings were significant, indicating convergent validity. Discriminant validity of the proposed six-factor model was tested by contrasting it with alternative CFA models. The fit indexes in Table 5 show that the proposed six-factor model fits the data better than the alternative models, confirming discriminant validity. Fornell and Larcker (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981) method was applied to check for convergent and discriminant validity. The square root of the average variance extracted for each latent construct is in the last column of Table 4. As recommended, all the estimates exceed the correlation between the factors comprising each pair.

Table 5. Confirmatory factor analysis for survey items in study 2

Notes. LMX, Leader-member exchange; LEE, Leader effectiveness; PSY, Psychological closeness.

CFI, comparative fit index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis index; SRMR, standardized root mean square residual.

N = 318.

STATA ivreg2 was used to detect if endogeneity and overidentification of the model were concerns. Estimates from the Hausman Test (6.41, p > .05; Hausman, Reference Hausman1978) and the Sargan-Hansen test (for overidentification check; 1.58, p > .05; Hansen, Reference Hansen1982) were non-significant. This indicated that endogeneity was not a concern, and that the model was tenable. However, the first stage of two-stage least squares had an F = .50, suggesting that the instruments might be weak (Stock & Yogo, Reference Stock, Yogo, Andrews and Stock2005). The values of the endogeneity and overestimation test are questionable given the weak instruments. Given that the instruments were weak, following the recommendations of Antonakis, Bendahan, Jacquart, and Lalive (Reference Antonakis, Bendahan, Jacquart, Lalive and Day2014), structural equation modeling using a maximum likelihood approach was used correlating the disturbance term for psychological closeness and LMX. More details are given in the hypotheses testing section.

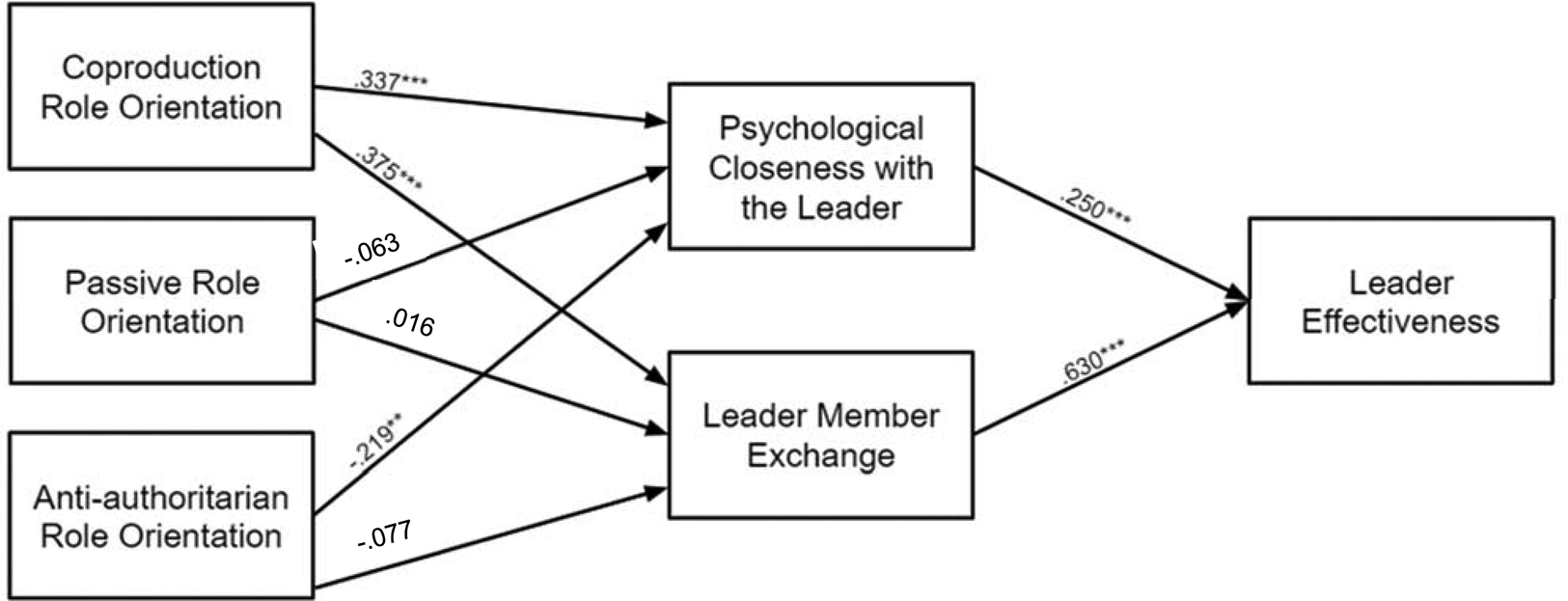

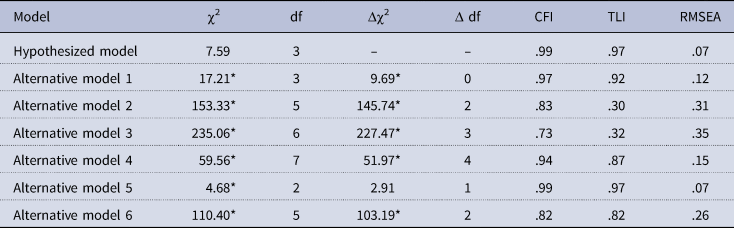

Hypothesis testing

All models were tested using path analysis in AMOS (version 24) using maximum-likelihood (ML) estimation. All effects were evaluated using standardized regression coefficients. All hypothesized variables and relationships were at the individual level. First, the hypothesized model where co-production, passive, and anti-authoritarian role orientation indirectly affect perceived leader effectiveness via psychological closeness and LMX was tested. In this model, psychological closeness and LMX were allowed to covary (.627, p < .001), given prior research indicating that these variables are closely related (Story et al., Reference Story, Youssef, Luthans, Barbuto and Bovaird2013). The results of this test revealed that the model fit well (χ2 (3, N = 165) = 7.59, CFI = .99, TLI = .97. RMSEA = .07), thus the hypothesized model was considered a reasonable means to test the hypotheses. See Figure 2 for significant standardized coefficients. A model was also tested including the effects of control variables as well, however, none significantly predicted leader effectiveness. Thus, this model was not used.

Figure 2. Path model depicting role orientation indirectly impacting leader effectiveness via psychological closeness and leader-member exchange in study 2.

Notes. *p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

The hypothesized model along with several alternative models was tested to address alternate conceptualizations of the relationships between variables in this study (Raykov & Marcoulides, Reference Raykov and Marcoulides2006). See Table 6 for results. Alternative model 1 removed psychological closeness as indirectly affecting the relationship between co-production, passive, and anti-authoritarian role orientation and leader effectiveness, due to research suggesting LMX may explain more variance than closeness (Story et al., Reference Story, Youssef, Luthans, Barbuto and Bovaird2013). Alternative model 2 tested the possibility that communication frequency could indirectly impact the relationship between role orientations and relationship quality (e.g., psychological closeness and LMX), as prior research has shown that frequency of communication could encourage followers to become close to a leader (Antonakis & Atwater, Reference Antonakis and Atwater2002). Specifically, frequent interactions between a leader and a follower may give more opportunities for followers to get to know leaders and establish friendship (Napier & Ferris, Reference Napier and Ferris1993; Torres & Bligh, Reference Torres and Bligh2012). Alternative model 3 tested a reverse causality model. Alternative model 4 tested a model in which co-production, passive, and anti-authoritarian role orientation impacted closeness and LMX indirectly via leader effectiveness on the basis that effective leaders develop positive relationships Antonakis & Atwater, Reference Antonakis and Atwater2002; Liden & Maslyn, Reference Liden and Maslyn1998; Napier & Ferris, Reference Napier and Ferris1993). Closeness and LMX were not allowed to covary as outcomes in this model. Alternative model 5 tested the possibility that co-production role orientation could have a direct effect on leader effectiveness by adding a direct path. This path was non-significant, indicating the absence of a direct effect, via psychological closeness and LMX. Finally, alternative model 6 tested the possibility of LMX and psychological closeness indirectly impacting leader effectiveness through all three follower role orientations. It is worth noting that alternative model 6 featured LMX and psychological closeness collected at time 2, and all role orientations collected at time 2. These alternative models fit less well than the hypothesized model. Thus, the hypothesized model deemed to be the most parsimonious and best fit.

Table 6. χ2 difference tests and fit indices for hypothesized and alternative models in study 2

Notes. N = 318. Δχ2 = chi-square difference. Δ df = difference in degrees of freedom.

CFI, comparative fit index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA, root mean square of approximation.

*p < .05.

Standardized path estimates were used to test hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1c, as well as 2a, 2b, and 2c. As shown in Figure 2, co-production role orientation significantly positively predicted psychological closeness (β = .337, p < .001) and anti-authoritarian role orientation significantly negatively predicted psychological closeness (β = −.219, p < .01), however, passive role orientation did not (β =−.063, p = n.s.). Therefore, hypotheses 1a and 1c are supported, but not hypothesis 1b. In addition, co-production role orientation significantly positively predicted LMX (β = .375, p < .001), but passive role orientation (β = .016, p = n.s.) and anti-authoritarian role orientation (β = −.077, p = n.s.) did not. Therefore, hypotheses 2a is supported, but not hypotheses 2b and 2c.

Bootstrap analyses for estimating indirect effects with 20,000 bootstrapped samples were used to test hypotheses 4a, 4b, and 4c. The significance of the indirect effects was tested using 95% confidence intervals. This method provides benefits over regression testing because corresponding confidence intervals may not be normally distributed (Shrout & Bolger, Reference Shrout and Bolger2002). The standardized indirect effect from co-production role orientation to leader effectiveness (M = .321, p = .001, CI = .325, .402) was positive and significant, supporting hypothesis 4a. The standardized indirect effects from passive role orientation (M = −.006, p = .000, CI = −.124, .113) and anti-authoritarian role orientation (M = −.103, p = .099, CI = −.227, .019) to leader effectiveness, via psychological closeness and LMX were negative, however, non-significant; thus, hypotheses 4b and 4c were not supported.

General discussion