As is well known, Aquinas takes there to be an absolute prohibition against lying.Footnote 1 In this respect, Aquinas's views are part of a longstanding tradition in ethics, one that includes the majority of moral philosophers from Augustine to Kant.Footnote 2 But unlike many others in this same tradition, Aquinas rejects the view that lying essentially involves any form of intentional deceit. On his account, the mere assertion of falsehood is all that's necessary and sufficient for lying.

Aquinas's views about the morality of lying are well known and often discussed by commentators.Footnote 3 But his views about the nature of lying have yet to receive the attention they deserve. Indeed, as far as I am aware, there is no detailed analysis of his views in this regard to be found in the literature. In this article, I take some of the first steps necessary to correct this state of affairs by clarifying and offering a limited defense of the account of lying that Aquinas presents in his Summa Theologiae—more specifically, in that portion of it known as the treatise on truth (Part 2-2, Questions 109–113).Footnote 4 Here, as elsewhere, Aquinas accepts the traditional characterization of lying as a type of action that is opposed to the truth and develops his own preferred account by offering a gloss on this characterization. As we shall see, Aquinas's account turns on a specific understanding of both (a) the kind of truth to which lying is opposed (namely, truthfulness), and (b) the kind of opposition that lying bears to such truth (namely, formal opposition).

In what follows, I present and explain each of these two aspects of Aquinas's account. In Section 1, I focus on the relevant notion of truth as truthfulness. In Section 2, I turn to the specific way in which Aquinas takes lying to be opposed to truthfulness. As will become clear, Aquinas's account of the nature of lying has three substantive philosophical commitments. In Section 3, therefore, I conclude my discussion by offering a limited defense of each of these three commitments—including, in particular, his surprising contention that we can lie without any intent to deceive.

1. Truth as Truthfulness

Aquinas's treatise on truth in Secunda secundae (qq. 109–113) is part of a more general treatment of justice and its associated virtues (qq. 57–122).Footnote 5 In this context, Aquinas does not typically use ‘truth’ as we do now (and as he himself does elsewhere) to refer to a property of beliefs or mental representations (namely, the property of corresponding to reality). Instead, he tends to use it here to refer to a specific type of virtue—truthfulness—which is importantly associated with justice and, therefore, with the will.Footnote 6 In q. 109, Aquinas makes this point explicit, distinguishing truthfulness (or ‘truth in the will’) from truth in the more familiar sense (‘truth in the intellect’):

Truth as cognized belongs to the intellect. But it is on account of the will, through which human beings make use of both their habits and their bodily members, that they produce external signs for the sake of expressing the truth [as cognized]. It is in accordance with this expression of truth, moreover, that truth is an act of the will. (ST 2-2.109.3 ad 2)

Truth in the intellect, Aquinas tells us, is a property that rational agents have insofar as they cognize the truth (that is, insofar as they believe or perhaps are properly disposed to believe what is true). By contrast, truth in the will (or truthfulness) is a property that such agents have insofar as they are disposed to express the truths they've cognized.Footnote 7

So far so good. But what exactly does Aquinas have in mind when he speaks of the expression (manifestatio) of truths or beliefs? In the passage just quoted, he suggests that the notion has something to do with the production of ‘external signs’. In the next question (q. 110), he sets out his meaning more fully:

The virtue of truth—and consequently, [each of] the vices opposed to it—consists in the expression of something by means of a certain kind of sign. This sort of expression, or assertion (enuntiatio), involves an act of reason, one which compares a sign to what it signifies (indeed, every representation consists in such a comparison, which is the distinctive act of reason). This explains why, even though non-rational animals express things, they don't intend (intendunt) to express them. On the contrary, they do things by natural instinct that result in the expression of something. (ST 2-2.110.1)

In this passage, Aquinas distinguishes two different types of truth expression: one that is characteristic of rational agents or human beings (he calls this type ‘assertion’); and another that is characteristic of irrational or non-human animals (he doesn't give this type a special name). Both types of expression involve the production of external signs—that is, the performance of observable actions that indicate the truth of some proposition or belief. But only the former, Aquinas tells us, involves the intention (intention) to express the truth; hence only this type is relevant to the virtue of truthfulness.

What Aquinas has in mind here can perhaps best be illustrated by example. Consider a vervet monkey who, on seeing an approaching predator, produces a bark that alerts the other monkeys in its group to the danger. In such a case, the vervet monkey clearly expresses a truth (namely, that a dangerous animal is approaching), and expresses this truth via the production of an observable sign (namely, a bark). Even so, we might suppose, the monkey's bark arises merely from natural instinct rather than from any conscious desire or intention to express some truth.Footnote 8 By contrast, intentional expression—which Aquinas calls ‘assertion’—requires this further desire or intention.

As the foregoing makes clear, Aquinas thinks assertion involves two and only two things: (i) the production of a sign, (ii) and the intention thereby to express or communicate some proposition. As he sees it, moreover, there is no restriction on the type of sign produced; hence there can be both verbal and non-verbal assertions.Footnote 9 Since this account of assertion will figure prominently in what follows, I provide a schematic statement of it here:

-

(A) A subject S asserts a proposition p iff (i) S performs some observable action Φ, and (ii) S performs Φ with the intention of expressing that p.

Although this schema goes some distance toward clarifying Aquinas's account of assertion (more on this in §3 below), it does not by itself give us all we need to characterize the virtue of truthfulness. For truthfulness isn't merely a disposition to assert propositions; it is a disposition to assert only those propositions that one in fact believes are true. To characterize truthfulness, therefore, we must distinguish mere assertions (as at A) from what we might call truthful assertions:

-

(AT) A subject S truthfully asserts a proposition p iff (i) S asserts p, and (ii) S believes that p is true.

In light of this definition, we can say that truthfulness is a virtue of will that inclines its possessors to truthful assertion—that is, a property that disposes its possessors to assert only those propositions they believe are true.

Now just as we can define truthful assertions, so too we can define untruthful assertions:

-

(AU) A subject S untruthfully asserts a proposition p iff (i) S asserts p, and (ii) S believes that p is false.

As we shall see, this latter definition turns out to be important, since it captures Aquinas's own account of lying, and hence his understanding of the type of action that is opposed to truthfulness.

2. Opposition to Truthfulness

In the first article of q. 110, Aquinas distinguishes three different ways that an action can be opposed to the expression of truth, and hence to the virtue of truthfulness:

Suppose the following three things occur at once—namely, [1] that what is asserted is false, [2] that there is a desire to assert what is false, and [3] that there is an intention to deceive. In that case, there is falsity materially (because what is said is false), formally (because of the desire to say something false), and effectively (because of the desire to produce falsity). (ST 2-2.110.1)

Here Aquinas claims that an assertion can be opposed to the expression of truth either materially, formally, or effectively. If we allow for the fact that he moves freely between ‘desire’ (voluntas) and ‘intention’ (intentio) in this context, we can clarify his three types of opposition as follows:

Types of opposition to truthfulness

-

• Material. An assertion A (made by a subject S) is materially opposed to truthfulness iff A is false.

-

• Formal. An assertion A (made by a subject S) is formally opposed to truthfulness iff A is asserted (by S) with the intention of asserting something false.

-

• Effective. An assertion A (made by a subject S) is effectively opposed to truthfulness iff A is asserted (by S) with the intention of producing a false belief in someone.

Aquinas's terminology is intended to suggest an analogy between these different types of opposition and three of Aristotle's four causes—material, formal, and efficient.Footnote 10 In the case of material opposition, the point of the analogy is obvious. An assertion is materially opposed to the truth (or has ‘material falsity’) just in case its ‘matter’ (or content) is false—that is, just in case the proposition that it asserts is false. In the case of formal opposition, the point of the analogy is also straightforward. According to Aquinas, all actions are individuated by their forms, and the forms of human actions in particular are given by their intended objects.Footnote 11 Hence, to say that an action is formally opposed to the truth (or has ‘formal falsity’) is just to say that its intended object includes the assertion of something false. As for the case of effective opposition, here the point of analogy is less straightforward, but still fairly clear. ‘Deception’ Aquinas tells us ‘is the characteristic effect of a false assertion’ (a. 1). Hence, to say that an action is effectively opposed to the truth (or has ‘effective falsity’) is just to say that its intended object includes the production of this characteristic effect.

Having distinguished these different types of opposition, Aquinas presents his own account of lying in terms of the second type:

The nature of a lie is taken from formal falsity—that is, from the fact that someone has the intention (voluntatem) of asserting what is false. This explains why the word ‘lie’ (mendacium) is derived etymologically from something ‘spoken against the mind’ (contra mentum dicitur). (ST 2-2.110.1)

Here Aquinas characterizes lying in terms of ‘formal’ falsity or opposition to the truth. To lie, he claims, is to intentionally assert what is false. Recalling that assertion, for Aquinas, is a matter of performing an action with the intention of expressing some proposition, we can state this account of lying as follows:

-

(L) A subject S lies iff (i) S asserts a proposition p, and (ii) S believes that p is false.

As should be clear, L just is the account of untruthful assertion given at AU above.

Having presented this account of lying, Aquinas now proceeds to defend it. He begins with a comparison between formally and materially false assertions:

If someone says something formally false, [i.e.,] with the intention (voluntatem) of saying something false, then even if what is said turns out to be true, insofar as an act of this sort is a voluntary and moral act, it has falsity in itself, and truth only extrinsically. Hence it satisfies the specific nature of a lie. (ST 2-2.110.1)

Here Aquinas asks us to consider a case where someone is intending to assert something false but inadvertently says something true. Suppose it's 1942, and the members of a Nazi search party come to your door looking for Jews. Suppose, moreover, that you tell the Nazis ‘there are no Jews in the house’, fully believing that this is false, but your claim turns out to be true (say, because unbeknown to you, the family you are hiding has just left the premises). Have you lied? Aquinas thinks the answer is clearly ‘Yes’, and hence that material falsity is neither necessary nor sufficient for lying. And the reason is that he takes material falsity to be an extrinsic feature of assertions (since it depends at least partly on the way the world is), whereas he takes that which makes an action a lie to be an intrinsic feature of it (and hence one that depends solely on the form or intention that individuates them).

But is the intention to assert a falsehood by itself sufficient to qualify an action as a lie? Aquinas recognizes that one might object to this claim, insisting instead that for an action to count as a lie it must also possess the intention to deceive. In response, however, he says the following:

The fact that someone intends to produce a false opinion in someone else, by deceiving him, does not pertain to the specific nature of a lie. On the contrary, it pertains to a certain kind of perfection of the lie—just as, among natural things, something is placed in a given species when it has the form [definitive of that species], even if the perfection of that form is lacking. This is clear, for example, in the case of a heavy body held up by force, so that it doesn't come down in accordance with the inclination of its form. In the same way, therefore, it is clear that a lie is directly and formally opposed to the virtue of truth. (ST 2-2.110.1)

In this passage Aquinas develops an analogy designed to show that the intention to deceive (or effective falsity) is not necessary for lying—though it is sufficient for it. Consider, he says, a heavy body such as a rock. Just in virtue of possessing its specific form or nature, it has the disposition to fall. But whether or not it manifests this disposition, and hence is actually falling, is a further question—one that pertains not to the form, but to its complete manifestation or perfection. The same is true, Aquinas suggests, with lying and the intention to deceive. He grants that deception is the characteristic effect of lying. That is to say, he grants that when we assert a falsehood, we typically do so for the sake of producing a false belief in someone else. In this respect, he thinks, an action characterized by formal falsity (i.e., the intention to assert a falsehood) is naturally disposed to manifest effective falsity (i.e., the intention to deceive). Still, the action needn't manifest this further disposition. And even if it doesn't, he thinks the action still qualifies as a lie. Thus, just as falling pertains to the perfection of a body rather than its nature, so too the intention to deceive pertains to lying.

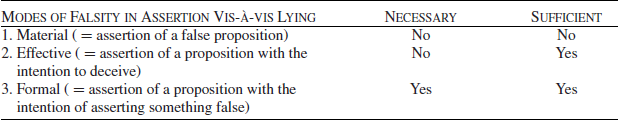

What all of this shows is that Aquinas regards effective falsity as occupying a kind of middle ground between material and formal falsity. Unlike material falsity, which is neither necessary nor sufficient for lying, effective falsity is sufficient for it. But unlike formal falsity, which is both necessary and sufficient for lying, effective falsity is not necessary. Putting this altogether, we can summarize Aquinas's account of lying in tabular fashion as follows:

3. A Limited Defense of Aquinas's Account

As we can see from the table above, Aquinas's account carries three substantive philosophical commitments:

-

(a) We can lie without asserting anything false.

-

(b) We cannot make an intentionally deceptive assertion without lying.

-

(c) We can lie without any intention to deceive.

Let us consider each of these claims in turn.

I think it's fair to say that many philosophers, past and present, would agree with Aquinas's claim at (a), that we can lie without asserting anything false. It is sometimes said that telling a lie entails saying something false, but as Donald Davidson (Reference Davidson and Sacks1979, 40) points out, this seems wrong: ‘Telling a lie requires not that what you say be false but that you think it is false’ (emphasis added). Still, it must be admitted that there is something puzzling about this view.Footnote 12 To return to our earlier example: if you tell the Nazis ‘there are no Jews in the house’, believing that this is false, but your claim turns out to be true, it is tempting to think that you have not actually succeeded in lying. Perhaps you tried to lie; even so, you failed. If this description of your action were correct, it would turn out that, contrary to Aquinas's view, lying requires the assertion of something false after all.

But should we accept this description of your action? I think not—and precisely for the reasons Aquinas himself suggests. Lying is a voluntary or moral action, and hence something over which we have control. If lying required not only the possession of certain intentions, but also the correspondence of our beliefs to reality, then whether we are lying on a given occasion would often be a matter of moral luck. Better, therefore, to distinguish lying (which involves only the intention to assert something false) from asserting something that is actually false (which involves both this intention and the cooperation of the world), and to say that whereas success with the latter is by no means guaranteed, success with the former always is.

What about Aquinas's claim at (b)—that if we assert some proposition with the intention to deceive, we thereby tell a lie (even if the proposition in question is true)? Do all cases of intentionally deceptive assertion also count as cases of lying? In an important paper, Jonathan Adler (Reference Adler1997) defends a negative answer to this question. Indeed, in defending a negative answer, he claims to be upholding the traditional view that lying is a specific type of intentional deception. Taking Augustine's treatment of the biblical case of Abraham as paradigmatic, Adler says:

Abraham, venturing into a dangerous land and fearing for his life if Sarah is taken to be his wife, tells Abimelech the king that she is his sister. God appears to Abimelech to warn him away from taking Sarah because ‘She is a married woman’. Frightened, Abimelech confronts Abraham, who defends his obvious deception by denying that he lied:

‘…they will kill me for the sake of my wife. She is in fact my sister, she is my father's daughter though not by the same mother; and she became my wife …’.

Augustine defends Abraham as not having lied, classifying this as only a case in which Abraham ‘concealed something of the truth’. Augustine does not even comment on the deception. Why do Abraham, Augustine, and many others take the lie to be so much worse, and are they correct? (Adler Reference Adler1997, 436)

It's not clear to me that Adler's interpretation of Augustine is correct. Aquinas, for example, who certainly takes himself to be following Augustine, also speaks of Abraham's intention to ‘conceal the truth’, but only to distinguish it from the intention to deceive or to assert something false:

It must be said, as Augustine does, that certain people are introduced in Sacred Scripture as examples of perfect virtue, and we must not judge any of these people to be liars … Thus, as Augustine says in his commentary on Genesis, when Abraham claims ‘Sarah is my sister’, he wanted to ‘conceal the truth’, not to tell a lie. (ST 2-2.110.3 ad 3)

But none of this is quite to the point. What we're interested in here is not a historical or psychological question: Did Abraham, as described in the biblical story, actually have the intention to deceive (as opposed, say, to the intention to conceal the truth)? On the contrary, we're interested in a purely philosophical question: Granting (perhaps even contrary to fact) that Abraham had the intention to deceive, does it thereby follow that he lied in saying that Sarah is his sister? As the claim at (b) makes clear, Aquinas is committed to an affirmative answer. But why think that he's right about this? After all, the only thing Abraham explicitly says is ‘Sarah is my sister’—and that is true. Why not agree with Adler that this sort of case (never mind the actual interpretation of biblical texts) constitutes a genuine counterexample to (b)?

Aquinas doesn't explicitly address this objection, but I think it is clear he has the resources to do so. Even if ‘Sarah is my sister’ is all that Abraham explicitly says, there is still a further question about whether this is all he intentionally expresses—or, in Gricean terms, whether this is all he communicates via conversational implicature. And here, I think, the answer is clearly ‘No’. To deceive the king, Abraham must intend his true assertion to lead the king to think that Sarah is not his wife. But this is just to say that Abraham intends his assertion that Sarah is his sister to ‘implicate’ the false proposition that Sarah is not his wife. To the extent that such an implicature counts as an untruthful assertion, however, Aquinas will say that Abraham has lied.

The phenomenon of implicature (or indirect expression) is familiar enough, and though Aquinas doesn't explicitly discuss it, it is clear that any adequate theory of belief expression must take it into account.Footnote 13 If you ask me to go to the movies, and I respond by saying ‘I've got to work’, I thereby intentionally express two propositions—one directly (namely, that I have to work), and one indirectly (namely, that I can't go to the movies). Using this example, we can distinguish two different ways of a subject can assert a proposition:

Types of assertion of a proposition

-

• Indirect. A subject S indirectly asserts a proposition p iff S asserts p by asserting another proposition q.

-

• Direct. A subject S directly asserts a proposition p iff S asserts p, but not indirectly.

And in terms of these definitions, we can clarify Aquinas's claim at (b) as follows

-

(b*) We cannot make an intentionally deceptive assertion without (at least indirectly) asserting something untruthful (and hence lying).

Understood in this way, Aquinas's claim seems not only true, but necessarily so. To assert something with the intention of deceiving someone, you must aim at the production of a false belief in that person. But to do that, you must somehow express the false proposition that you wish to be believed. It's a short step from here, however, to the conclusion that all cases of assertion involving intentional deception are cases of lying. In fact, it requires only the assumption (1) that indirect assertions (via, say implicature) are nevertheless assertions, and (2) that assertions of falsehood (in Aquinas's sense of ‘assertion’) are sufficient for lying.

With this last assumption, we come to the heart of Aquinas's account. This is the assumption driving the most controversial aspect of his account, namely, his commitment to the claim at (c), that we can lie without any intention to deceive. Many philosophers reject this claim, accepting instead what we might call ‘the intentional-deception view of lying’—that is, the view that lying essentially involves some type of intentional deception. Unlike Aquinas, therefore, who thinks that all cases of intentional deception are cases of lying (but not vice versa), many philosophers think that all cases of lying are cases of intentional deception (but not necessarily vice versa).

What should we say about the intentional-deception view of lying? The first thing to note is that it is not committed to the view that lying involves any obvious forms of deceit. On the contrary, the deceit involved may be of a very special or peculiar sort. Here again it is useful to cite the views of Donald Davidson:

While the liar may intend his hearer to believe what he says, this intention is not essential to the concept of lying; a liar who believes that his hearer is perverse may say the opposite of what he intends his hearer to believe. A liar may not even intend to make his victim believe that he, the liar, believes what he says. The only intentions a liar must have, I think, are these: (1) he must intend to represent himself as believing what he does not (for example, and typically, by asserting what he does not believe), and (2) he must intend to keep this intention (though not necessarily what he actually believes) hidden from his hearer. So deceit of a very special kind is involved in lying, deceit with respect to the sincerity of the representation of one's beliefs. (Davidson Reference Davidson and Elster1985, 88)

Davidson is not alone in appealing to something like insincerity to characterize the special type of deceit involved in lying. Many others have developed similar accounts, arguing that the liar must, at very least, intend to deceive his audience with respect to his own attitude toward the proposition he expresses.Footnote 14

But even these more plausible versions of the intentional-deception view of lying seem to me open to counterexample. Suppose you find yourself in a situation where you believe that there is no chance of your deceiving your listeners in any way. In such a case, let us grant, it is impossible to form, much less act on, the intention to deceive. Even in this sort of situation, you can presumably still utter certain words (or perform some other action) that would, as a matter of fact, express or communicate a proposition that you believe is false. But can't you also do so intentionally? It seems to me clear that you can—and that, if you do, your intentional expression counts as a lie. Perhaps a concrete example will help to drive the point home.

Suppose you find yourself in court, accused of a crime of which you are in fact guilty, and with the belief that the judge and jurors all know that you're guilty. Let us also suppose that you believe that you will be found guilty of the crime in question if and only if you explicitly claim that you committed it (never mind how you arrived at this belief). In this situation, can you intentionally express the false proposition that you are innocent? I find it hard to see why not. After all, your doing so requires only that you utter the words ‘I am innocent’ with the intention of expressing your innocence. Admittedly, you can't intentionally express these words for the sake of deceiving your hearers; that, we can assume, really is impossible. But surely this is not the only reason you might have for intentionally expressing the proposition that you are innocent. You might, for example, intentionally express your innocence to avoid being found guilty of the crime in question (and hence to avoid going to jail or paying a fine). Again, you might intentionally express your innocence ‘just for the fun of it’, or to show contempt for your accusers, or perhaps even to manifest your ability to intentionally express propositions that you think are false without any intention to deceive. Whatever the reason, your performing the action in question certainly seems possible; and assuming you do perform it, it seems clear that you have lied. But, then, assuming (as Aquinas does) that assertion just is intentional expression, it follows that the mere assertion of a falsehood is sufficient for lying, and hence that the claim at (c) is true.

I can see only three ways to resist this conclusion: (i) deny that it is possible to intentionally express your innocence in cases like the one that I've described; (ii) deny that this intentional expression of your innocence (even if possible) qualifies as an assertion; or (iii) deny that, such an expression (even if possible and even if it's a genuine assertion) counts as a lie. None of these lines of resistance seems to me promising.

Consider the first. What reason could we have for thinking it's impossible to intentionally express your innocence in cases like the one I've described? The only reason that suggests itself is that it is impossible in general to intentionally express a proposition with respect to which you think there is no chance of deceiving your listeners. But that seems excessively strong. Suppose a child is asked by her parents ‘Did you steal that gum?’, believing all the while that her parents know she has stolen it, and hence that nothing she says will count as evidence that she did not. Is there really nothing the child can do, in these circumstances, to express the proposition that she did not steal it? Can't she shake her head, or utter the words ‘No’, with the intention of expressing that she is innocent? It would certainly seem that she can. Nor is there any obvious difference between this case and the one in which the judge asks you directly ‘Did you commit the crime?’ Indeed, as I see it, even if the judge were God—and you knew that he is omniscient and hence incapable of being deceived—there would be nothing to prevent you from intentionally expressing the (false) proposition that you did not commit the crime.

Of course, we can still ask whether the intentional expression of falsehood in such cases qualifies as an assertion of anything. This brings us to the second line of resistance mentioned above. Here, I suspect, is where most defenders of the intentional-deception view of lying will want to dig in their heels. For the intentional-deception view goes hand-in-hand with a popular, Gricean conception of assertion.Footnote 15 According to this conception, assertion is a speech act that essentially involves an intention on the part of the speaker to produce a certain belief in their hearers, or at least to provide their hearers with evidence for believing something (as a means toward producing belief).Footnote 16 Very likely, this is the conception driving Davidson's account of lying. Indeed, as we have seen, Davidson thinks the liar must ‘intend to represent himself as believing what he does not’.Footnote 17

The problem with this line of resistance, however, is that the conception of assertion on which it is based appears to be open to counterexample. In each of the cases I've described (involving the child and her parents, you and the judge or God), a speaker performs an action fully convinced that the audience will regard the speaker as dishonest, and hence will not regard anything the speaker says or does as providing any evidence for the speaker's innocence. Even so, the action performed by the speaker in each of these cases seems intuitively assertoric. That is to say, the child certainly seems to be asserting something by shaking her head ‘No’, and you certainly seem to be making an assertion when you utter the words ‘I am innocent’. Intuitions are surely debatable here, but the plausibility of these cases makes it at very least problematic to rest the rejection of Aquinas's account on such a specific conception of assertion.Footnote 18

What, then, of the third and final line of resistance—denying that mere assertion of falsehood, as in the cases just described, is sufficient for lying? Here, I think, the grounds for resistance are weakest. It seems clear that the child does something wrong in denying to her parents that she's stolen the gum; likewise, it seems clear that you do something wrong in asserting your innocence before the judge (or God). But few parents would hesitate to say that the child is lying in such a case, and few judges (or theologians), I suspect, would hesitate to say that you were lying to the judge (or God) in the court case. Of course, one could always respond that the wrongdoing in these cases is not due to lying but to something else (say, failure to fulfill one's obligations to tell the truth). But it is hard to see what would motivate saying this. There is a strong intuition (codified by the traditional characterization of lying) according to which lying is opposed to telling the truth. But given that falsehood is the opposite of truth, and truth-telling is a matter of intentionally expressing what one believes is true, it seems to follow straightforwardly that lying is a matter of intentionally expressing what one believes is false.

For all these reasons, then, Aquinas's account of lying (as expressed at L) seems to me plausible—or at any rate, as plausible as the main alternatives to which it is opposed.Footnote 19