Introduction

On January 22, 1973, the US Supreme Court handed down Roe v. Wade, ruling that state and federal statutes criminalizing abortion or unduly restricting access violated a woman’s constitutional right to privacy.Footnote 1 The seeming suddenness of this decision was jarring for many, particularly in North Dakota, which had just seen an initiative to liberalize its abortion laws suffer overwhelming defeat 76 days earlier. The state’s pro-life movement was stunned. “I am in contact with our National Right to Life office in Washington,” Dr. Albert Fortman, director of the North Dakota Right To Life Association (NDRLA), told a reporter that day. “I can’t make a statement as to intent or reaction until we know what the decision means. This should be cleared up and then we can make a statement. Right now it’s in a state of flux.”Footnote 2

Supporters of the defeated initiative were gleeful. “That’s great, that’s really great news,” said Wendy Walsh, who played a prominent role in getting the measure on the ballot.Footnote 3 “We’re glad the Supreme Court recognizes the rights of women in this matter.” Walsh added that, in retrospect, she was glad her group had spent so little on the election. State Representative Aloha Eagles (R), who had introduced unsuccessful bills to liberalize abortion laws in 1969 and 1971, said she was “delighted that they [the court] went that far.”Footnote 4

The NRDLA governing board met on January 29 to consider strategy.Footnote 5 Attendees were dissatisfied with the state legislature, feeling that “many of the bills now being presented actually make it seem as though the supporters of such a bill support abortion in some cases.”Footnote 6 In response, the Association held a “Board Meeting & Political Action Meeting” on February 25, followed by a two-day meeting in May. The group generated five long-term objectives at these meetings: (1) elect pro-life politicians to the state legislature; (2) educate North Dakotans on the true nature of abortion; (3) expand the number of Right to Life chapters across North Dakota; (4) engage in state and national letter-writing campaigns; and (5) contact local doctors, hospitals, and clinics with questions about their abortion policies.Footnote 7

This study examines the development of North Dakota abortion law and policy in the years after Roe. Using government documents, archival data, and contemporary media accounts, it illustrates how this process unfolded in the state legislature and the government bureaucracy as well as how pro- and anti-abortion groups responded. The study also considers how the state’s political culture shaped abortion policy over the 1970s.

Political Culture, Abortion, and North Dakota

The political culture approach to public policy in the United States asserts that a state’s policies are shaped not only by demographic and economic variables but by cultural, historical, and political factors associated with that state as well.Footnote 8 Political culture can be defined as “the summation of persistent patterns of underlying political attitudes and values—and characteristic responses to political concerns—that is manifest in a particular political order, whose existence is generally unperceived by those who are part of that order and whose origins date back to the very beginnings of the particular people who share it.”Footnote 9 These patterns help determine what is acceptable political behavior within a state as well as which policies are likely to be promoted.

Elazar divided states into three types of political culture: individualistic, moralistic, and traditionalistic. The individualistic political culture “emphasizes the conception of the democratic order as a marketplace”Footnote 10 and is less interested in promoting the common good. Government is reluctant to interfere with the private sector. The moralistic political culture “emphasizes the commonwealth conception as the basis for democratic government,” with politics seen as a means of promoting the public good. Government is empowered to “intervene into the sphere of private activities when it is considered necessary to do so for the public good or the well-being of the community.”Footnote 11 The traditionalistic political culture “is rooted in an ambivalent attitude toward the marketplace coupled with a paternalistic and elitist conception of the commonwealth.”Footnote 12 Power is in the hands of an elite whose position is based on long-standing family and social connections.

When considering the Great Plains states, Elazar noted “the relatively small and stable populations of the plains region adds to the possibility for seriously exploring the region’s political-cultural patterns in great detail.”Footnote 13 Agriculture still dominated the region, even as it declined in terms of importance to the national economy. There was a tension “between the polity as a marketplace—a means to respond efficiently to individual and group demands—and the polity as a commonwealth—a means to achieve the good community.”Footnote 14 Pluralism was one whereby citizens “are free to choose their societal links, but they are expected to choose some fundamental mode of association—a church, a political party, or even some kind of basic social or professional activity—and stay with it the rest of their lives.”Footnote 15 North Dakota with its moralistic political culture had a “particular synthesis of marketplace and commonwealth.”Footnote 16 Although the establishment of a state-owned bank in 1919 and a state-owned grain elevator in 1922 might seem socialistic, these actions were not really “antimarketplace” but communitarian policies “designed to stabilize a very unstable market in which the small farmers were at a great disadvantage.”Footnote 17 However, this communitarian tradition conflicted with the “streak of moralistic conservatism endemic to North Dakota.”Footnote 18 Finally, the “commonwealth orientation of its citizenry once encouraged relatively greater levels of state activity,” although this has declined.Footnote 19

Research on the relationship between political culture and abortion policy is mixed: some studies indicate that demographics, economics, and partisanship are not enough to understand state behavior and that culture-based measures were necessary.Footnote 20 Others found that cultural measures provided little explanatory value.Footnote 21 It should be emphasized that Elazar “conceived political culture as an indicator of political style and process rather than an explanation of policy outcomes.”Footnote 22 The inability of states to achieve preferred policies does not necessarily mean that cultural differences on abortion were irrelevant. Instead, political culture can help explain such policy matters as why some state parties focused on abortion while others did not, why antiabortion groups became prevalent in some states and not others, and why some legislatures took an aggressive antiabortion stance.Footnote 23

With 617,792 residents in 1970, North Dakota’s demographics suggested some degree of cultural conservativism, particularly on abortion. The percentage of the population identifying as Catholic was 27.9% in 1971Footnote 24 and 26.7% in 1980,Footnote 25 or about one-fifth higher than the national average. In 1970, some 97.0% of the population identified as white and 55.7% lived in rural areas, whereas in 1980, 95.8% identified as white and 51.2% lived in rural areas.Footnote 26 Research confirms this conservatism: using national survey data to compute state estimates of public opinion on abortion, Uslaner and Weber found that in 1969, 34.7% of North Dakotans favored abortion on demand in the first three months of pregnancy and 53.1% opposed.Footnote 27 They calculated that 34.6% favored abortion in 1972 and 56.0% opposed. In addition, a 1974 state Democratic Party survey reported that 51% favored a constitutional amendment prohibiting abortion and 38% opposed.Footnote 28 However, the best indicator of North Dakotan attitudes was the 1972 initiative to liberalize state abortion laws, which was defeated 76.6% to 23.4%.Footnote 29

The North Dakota state legislature reflected the state’s cultural conservatism by passing a series of bills and resolutions that were intended to reduce the availability of abortion. There was little organized opposition against this approach at first. Examining legislative activity across the states, Halva-Neubauer divided policy-making approaches to abortion from 1973 to 1989 into challengers, codifiers, acquiescers, and supporters.Footnote 30 Challenger states were most hostile to Roe v. Wade, with their legislatures devoting considerable time to abortion policy and passing restrictive laws.Footnote 31 North Dakota proved to be a critical challenger state, with its legislature passing more abortion restrictions than any other.

The Development of Abortion Law before Roe v. Wade

General Development

The American states did not have any statutes overseeing abortion at the start of the nineteenth century. Instead, state courts relied on common law whereby “abortion was a criminal act only after the pregnant woman felt fetal movement,”Footnote 32 or “quickening.” States maintained this approach even as they started regulating the procedure itself in the 1820s. “Very early abortion laws functioned as malpractice laws that were designed to protect women but became more restrictive by the 1850s, increasingly punishing earlier-term abortions and prosecuting rather than protecting women.”Footnote 33 After the Civil War, states made abortion illegal throughout pregnancy and proscribed criminal sanctions on anyone seeking an abortion or assisting in its provision.Footnote 34 Such changes were recommended by formally trained physicians, particularly those with the American Medical Association, who held “a scientific understanding of human development as continuous from the point of conception,” whereby “quickening” had no relevance.Footnote 35 Drawing upon their medical knowledge, physicians argued that abortion was wrong at any point after conception.Footnote 36

Nineteenth-century statutes generally prohibited abortions except to save the life of the mother.Footnote 37 With patient health defined as a medical matter, access to a legal abortion was left to the discretion of physicians,Footnote 38 thereby keeping any discussion about abortion out of the public sphere. State legislatures had little reason to reexamine these statutes, which remained largely unchanged in most states for decades. Although disputes over abortion policy could be found in medical journals as early as the 1920s, public debate remained minimal into the 1950s.Footnote 39

Liberalization of state abortion laws began in earnest with the publication of the Model Penal Code by the American Law Institute in 1962. Intended to help states modernize their statutes, the Code permitted abortions in cases where pregnancy would (1) result in the death or impairment of the mother, (2) the fetus would be born with severe physical or mental defects, or (3) pregnancy was a result of incest or rape.Footnote 40 These changes represented “a major contraction of the role of the criminal law in family affairs.”Footnote 41 By the end of the decade, more than a dozen states had incorporated the Model Penal Code into their laws.Footnote 42

In 1970, Hawaii passed legislation that went beyond the Model Penal Code by allowing abortion on request for state residents.Footnote 43 New York legalized abortion access that same year, but without any residency requirements.Footnote 44 Alaska followed shortly thereafter.Footnote 45

Washington held the nation’s first referendum on abortion liberalization in 1970, leading to a bitter campaign between the Voice for the Unborn (VFU) and the doctor-led Washington Citizens for Abortion Reform.Footnote 46 The VFU inundated voters with campaign literature and door-to-door canvassers. They also sponsored billboards with pictures of a four-month-old fetus and the message “Kill Referendum 20, Not Me.” In contrast, the Washington Citizens for Abortion Reform relied on a television campaign to get its message across. The referendum passed with 56.5% of the vote, doing particularly well in Seattle.

Polls indicate that popular support for abortion to preserve the mother’s life or prevent child deformity grew steadily over the 1960s.Footnote 47 Support for abortions for economic reasons or the desire not to have children also expanded, though at a slower pace. Notably, support among Catholics grew at greater rates than the rest of the population.

In 1972, supporters of more liberal abortion laws gathered enough signatures to place the issue on the ballot in Michigan and North Dakota. “Pro-abortion forces believe they are on the verge of major victories that will soon make abortion on request available throughout much of the country,” reported the New York Times. Footnote 48 Success in the socially conservative Midwest would bode well for a national movement. Conversely, the nascent Right-to-Life movement, having endured a series of setbacks, needed a clear victory to halt the momentum towards liberalization.

North Dakota Abortion Law

North Dakota abortion law was based on the 1877 Dakota Territory statutes, which mentioned abortion in two places. First, the Territory Code contained a section based on the legal theory of coverture, which excused a wife from punishment if she committed a criminal act in the presence or with the assent of her husband. However, coverture was not absolute and the Code provided a list of serious crimes, including abortion, which served as exceptions.Footnote 49 These coverture statutes would be removed with statehood.

Second, the 1877 Code declared,

Every person who administers to any woman pregnant, or who prescribes for such woman, or advices or procures any such woman to take any medicine, drug or substance whatever or who uses or employs any instrument or other means with intent thereby to procure the miscarriage of such woman, unless the same shall have been necessary to preserve her life is punishable by imprisonment in the territory prison not exceeding three years, or in a county jail not exceeding one year.Footnote 50

In addition, any woman “who solicits of any person any medicine, drug or substance whatever” to procure a miscarriage (unless necessary to preserve her life) could be jailed for a year or fined up to $1,000.Footnote 51

With statehood came change. The 1895 Revised Codes of North Dakota defined “abortion” as “The willing killing of an unborn quick child by an injury committed upon the person of the mother of such child.”Footnote 52 It also noted that, when under trial for procuring or attempting to procure an abortion, a defendant “cannot be convicted upon the testimony of the person injured unless she is corroborated by other evidence.”Footnote 53

In 1909, the state prohibited any advertising of medical treatment where “it is claimed that sexual diseases of men and women may be cured or relieved, or miscarriage or abortion produced, or … any medicine or means whereby the monthly periods of women can be regulated, or the menses re-established if suppressed.”Footnote 54 Violation of this statute was a misdemeanor with a fine of $50 to $500 or imprisonment for up to six months. By 1913, the state code allowed the State Board of Medical Examiners to revoke the medical license of any physician engaged in “the procuring or aiding or abetting in procuring or attempting to procure a criminal abortion.”Footnote 55 Finally, in 1915 the legislature gave the newly organized state board of chiropractic examiners the power to refuse or revoke a license for such “dishonorable, unprofessional, or immoral conduct” as the performance of a criminal abortion.Footnote 56

Data on the enforcement of such laws is difficult to find. One report noted that the North Dakota state Attorney General reported nine convictions between 1921 and 1932.Footnote 57 In addition, several North Dakota Supreme Court decisions involved failed efforts to modify or overturn abortion convictions, such as State v. Shortridge (1926), State v. Phillips (1938), and State v. Dimmick (1941).

Decades passed before the state legislature took up the subject of abortion again. On February 7, 1967, state senators from Fargo, Grafton, and Grand Forks introduced Senate Concurrent Resolution “KKK” directing the legislative research committee “to study the miscarriage and abortion statutes of the state to determine whether or not they were in need of amendment.”Footnote 58 The Resolution was referred to the Committee on Social Welfare and Veterans’ Affairs and then re-referred to the Legislative Research Resolutions Committee. The Resolution was “indefinitely postponed” and allowed to die with the end of the session.Footnote 59

In January 1969, Representative Aloha Eagles (R-Fargo) introduced House Bill 319 to expand the circumstances under which a legal abortion could be performed.Footnote 60 These included: rape or incest; the woman’s life was in danger; or “strong indications of possible physical deformity or mental retardation of the unborn child.”Footnote 61 Abortion remained illegal after the sixteenth week of pregnancy. Eagles’s bill also called for the creation of hospital panels to decide whether an abortion was warranted. HB 319 received a Do Pass vote of 11-7 in the House Social Welfare committee.Footnote 62 However, the full House voted 52–42 against the bill. Eagles reintroduced the bill in 1971, but it was defeated 85–15.Footnote 63

In December 1971, Wendy Walsh, a research assistant at North Dakota State University in Fargo, helped organize North Dakota Citizens for Legal Termination of Pregnancy (NDCLTP) in an attempt to use the initiative process as a means of liberalizing abortion laws. The initiative would allow a licensed physician to perform an abortion (1) before the woman entered her twentieth week of pregnancy or was “quick with child,” (2) with the woman’s consent unless she was under 18, in which case her husband or guardian needed to consent, (3) the woman was a state resident, and (4) the procedure was done in a state-approved facility.Footnote 64 Within weeks, dozens of volunteers were canvassing Fargo, Grand Forks, and Minot with petitions. Needing 10,000 signatures, the group collected 10,845 by September, mostly from Fargo-area residents.Footnote 65 The measure easily qualified for the November ballot.

The signature-gathering efforts garnered the attention of the North Dakota Right to Life Association. Incorporated in 1970, the association was chaired by Albert H. Fortman, a Lutheran vascular surgeon with a practice in Bismarck.Footnote 66 Montana-born, Fortman received his medical degree from Northwestern Medical School in Illinois, held active staff membership at St. Alexius and other facilities, and served for a time as Clinical Professor of Surgery at University of North Dakota Medical School.Footnote 67 He became the public face of the NDRLA, willing to debate at public forums, give speeches, and speak to the media. Fortman would be named a board member of the National Right to Life Committee in November 1972.Footnote 68

The NDRLA spent over $100,000 campaigning against the initiative, an unusually large amount at the time.Footnote 69 In contrast, initiative supporters waited until October to form the North Dakota Abortion Initiative Committee.Footnote 70 The Committee operated under severe financial limitations, gathering a little over $2,000 in contributions by election day.

The measure lost badly, receiving 62,604 of 267,456 votes statewide, or 23.4%. Support at the county level ranged from 9.9% in McIntosh County to 35.3% in Cass County.Footnote 71 The measure did poorly in the cities as well, receiving 28.8% in Bismarck, 39.0% in Fargo, and 38.8% in Grand Forks.Footnote 72 A presidential election year, voter turnout across the state was high at 71%.Footnote 73

Euphoric, the NDRLA board held a celebratory meeting on December 6, 1972.Footnote 74 At this meeting, Dr. Fortman announced that the organization would shift its focus to supporting policies that help young families, such as mandatory Rubella vaccinations, greater assistance with foster child programs, and stronger family life programs within the schools.Footnote 75 Edwin Becker, political director for the NDRLA and executive director of the North Dakota Catholic Conference, agreed with this policy change: “And now we’re going to the state legislature with a program that calls for birthright services, day care centers for the poor, equal rights for women, better health care and family life education.”Footnote 76

The Evolution of Abortion Law and Policy in North Dakota, post Roe

Post-Roe Reaction

The North Dakota legislature responded quickly to Roe v. Wade. On January 24, 1973, four Republican senators introduced Senate Bill 2404, which permitted abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy but only for medical reasons. Under this bill, a legal abortion would require consent from “the woman, her physician and the unborn father, if he is known.”Footnote 77 Anyone convicted of performing an illegal abortion would receive a minimum 10-year sentence. It also required service providers to maintain abortion records through a process overseen by the state Division of Vital Statistics. The bill was referred to the Committee on Social Welfare and Veterans’ Affairs. Initially, SB 2404 had the support of the North Dakota Right to Life Association and the North Dakota Catholic Conference, but these groups had second thoughts about a bill that, ultimately, eased restrictions on abortion access.Footnote 78 It was returned to the full Senate on February 8 and withdrawn through unanimous consent.Footnote 79

Next, the state legislature passed a conscience clause for medicine personal. House Bill 1533, sponsored by a Bismarck Republican, declared that “no hospital, physician, nurse, hospital employee, nor any other person, shall be under any duty, by law or contract, nor shall such hospital or person in any circumstances be required to participate in the performance of an abortion, if such hospital or person objects to such abortion.”Footnote 80 In addition, “no such person or institution shall be discriminated against because he or they so object.”Footnote 81 The first reading of the bill was held February 9. Although some questioned whether a conscience clause could lead to the withholding of essential services,Footnote 82 there was no organized opposition. The final version of HB 1533 passed the House 88-10 on February 14 and the Senate 47-4 on February 27.Footnote 83 Governor Arthur Link (D-NPL) signed it on March 21. The law took effect immediately.

The legislature then considered two Senate Concurrent Resolutions directed at Congress. Senate Concurrent Resolution 4069 urged Congress to “propose an amendment to the United States Constitution for ratification by the states which will guarantee the right of the unborn human to life throughout is intrauterine development subordinate only to saving the life of the mother, and will guarantee that no human life shall be denied protection of law or deprived of life on account of age, sickness, or condition of dependency.”Footnote 84 In contrast, Senate Concurrent Resolution 4019 called on “the United States Congress to exercise its power, granted under Article 3, Section 2, of the United States Constitution to limit the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court” with respect to abortion law.

The NDRLA strongly supported Senate Concurrent Resolution 4069, believing a Constitutional amendment was the best means of ending abortion nationwide. The sponsoring senator was invited to address the February 25 meeting of the NDRLA.Footnote 85 The leadership announced afterwards that the NDRLA would hold a rally in Bismarck on March 5, just before the Senate Judiciary Committee held hearings on the resolution. In preparation, the Association purchased newspaper advertisements publicizing the event, arranged for car and bus caravans to Bismarck, and gathered signatures for a petition in support of the resolution. These efforts brought hundreds to the state capital. “It’s a show of force by the Right to Life Association,” said Senator Ernest Pyle (R).

On March 5, the Senate Judicial Committee heard testimony from Dr. Fortman, who said, “a constitutional amendment was needed to restore ‘personhood’ to the unborn, the aged, the retarded and others who are dependent.” The North Dakota State University campus pastor and Edwin Becker also testified in favor of the resolution.

Concurrent Resolution 4069 passed the Senate 41-8 on March 6 and the House 84-12 on March 12. Concurrent Resolution 4019 died in the Senate without a vote. By June, 10 state legislatures had passed resolutions in support of a Human Life amendment to the US Constitution, including North Dakota, South Dakota, Maine, Maryland, Indiana, Idaho, Utah, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Minnesota.Footnote 86

Finally, on March 21, 1973, North Dakota joined 14 states in an appeal to the US Supreme Court to reconsider its stance on abortion by hearing a case out of Connecticut.Footnote 87 State Attorney General Allen Olson (R) supported the appeal, arguing that the 1972 election “represents the feelings of most North Dakotans.”Footnote 88 However, the US Supreme Court refused to hear the case, though, sending it back to the lower court.Footnote 89

With abortion a prominent and ongoing issue, the North Dakota Right to Life Association sought to stabilize its operations. The Association determined that $15,000 a year would cover its costs, with $5,000 coming from the Bismarck and Fargo Dioceses, $4,000 from the state Knights of Columbus, and $6,000 from membership dues.Footnote 90 At $5.00 per member, the NDRLA would need at least 1,200 paying members.

Despite Roe v. Wade, North Dakota continued to enforce its old abortion laws. A May 11, 1974, opinion by Attorney General Olson to the Cass County State’s Attorney indicated that, so long as the federal courts did not specifically declare a state statute unconstitutional, that statute remained state law:

From the decision of the United States Supreme Court, it can be readily ascertained that some provisions of Chapter 12-25 are not in harmony with the holding. Be that as it may, this office is not clothed or vested with legislative authority. We cannot rewrite or enact laws governing the conditions under which abortions may or may not be performed… . We cannot as a matter of law state that no state’s attorney may prosecute anyone for performing any abortion. Each state’s attorney, if the situation arises, will have to evaluate the specific facts and circumstances in the light of the United States Supreme Court decision and determine whether or not criminal process should be instituted.Footnote 91

North Dakota doctors were aware of their ambiguous legal status but remained hesitant to seek relief in federal court. “The state law is still in the books and the federal law is unclear,” an anonymous doctor told a reporter. “That plus all the legal battles you’d have to go through and the heat from the Right-to-Life people—well, life is too short. It’s just not worth it.”Footnote 92

The federal District Court for the District of North Dakota ended this legal ambiguity with Leigh v. Olson (1974). The Court stated,

plaintiff Richard Leigh is a practicing physician in Grand Forks, North Dakota, where he specializes in obstetrics and gynecology. From time to time, he is called upon to render medical decisions on behalf of his patients with respect to the advisability of seeking an abortion. At times, his best medical judgment dictates that with respect to certain patients and the special circumstances involved with those patients, an abortion should be performed.Footnote 93

North Dakota statutes interfered with the plaintiff’s ability to practice medicine as well as establish conducive doctor–patient relationships. The right of a woman to decide, in consultation with her doctor, to end her pregnancy “has been thoroughly discussed by Justice Blackmun in Roe and Doe.” The Court ruled in favor of Dr. Leigh: “It is incumbent upon the North Dakota Legislature to tailor the State’s abortion statutes to fit within the area of permissible state regulation as set out in Roe.” The old statutes were declared unconstitutional.

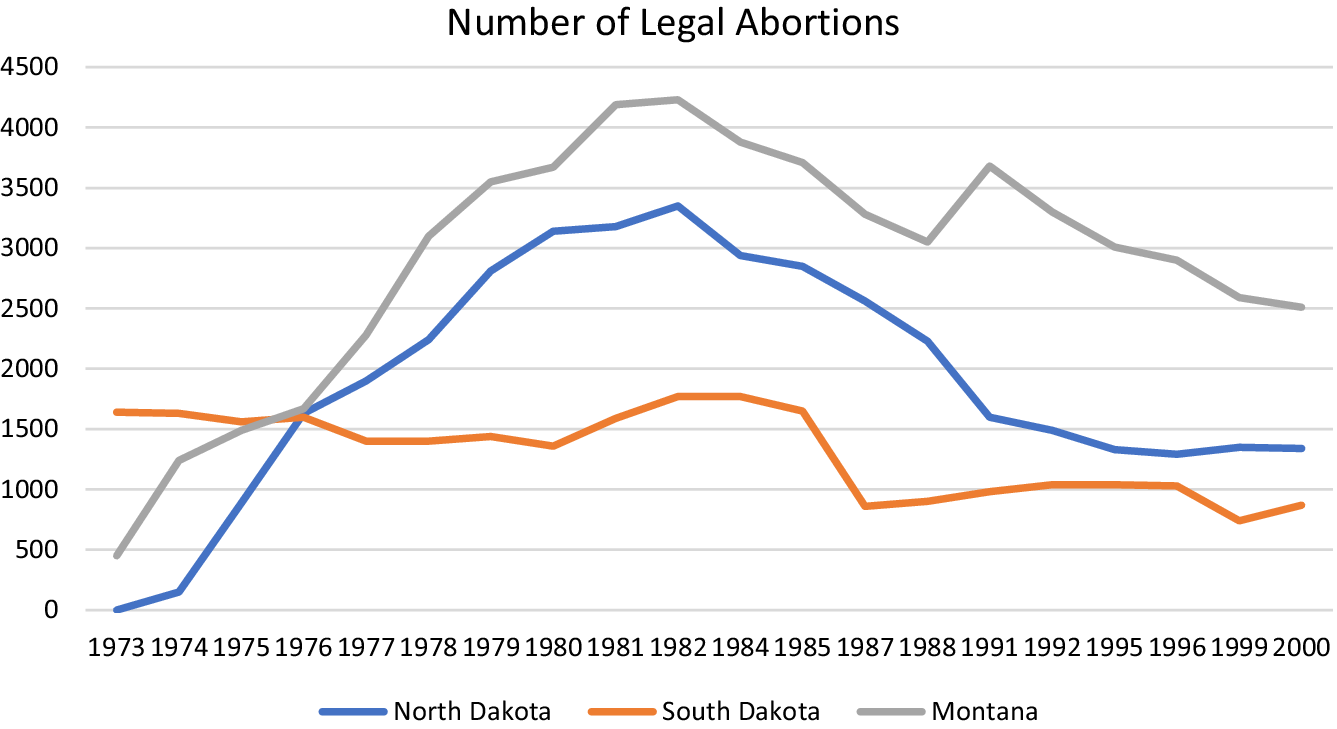

The decision noted that Olson had advised State’s attorneys to continue applying the old statutes, thereby placing medical professionals under legal threat: “the statutes and the stance of the Attorney General have caused the hospitals in Grand Forks, North Dakota, to refuse to permit their facilities to be used for performing abortions.”Footnote 94 Guttmacher Institute reports show that North Dakota and Louisiana (another state enforcing old statutes) were the only states without a single legal abortion in 1973. In contrast, South Dakota had 1,640 legal abortions and Wyoming had 180 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Legal Abortions in Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota, 1973–2000.

Source: Stanley K. Henshaw and Kathryn Kost, Trends in the Characteristics of Women Obtaining Abortions, 1974 to 2004, (Guttmacher Institute 2008), https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/pubs/2008/09/23/TrendsWomenAbortions-wTables.pdf.

With the threat of criminal prosecution removed, two private practitioners made abortions openly available to patients. Dr. Leigh had started providing the procedure four months after Roe v Wade despite the legal risk.Footnote 95 He would become the state’s primary abortion provider throughout the 1970s, performing some 2,500 abortions each year.Footnote 96 Dr. Robert Lucy waited until Leigh v. Olson before making abortions available at his Jamestown clinic. He would perform approximately 500 abortions each year during the mid-1970s.Footnote 97 Leigh would stop performing abortions in 1988, and Lucy retired in 1990.Footnote 98 Not a single private practitioner in North Dakota has offered abortion services since.

Despite Leigh v. Olson, the NDRLA continued to request information from schools and hospitals regarding their policies on abortion. For example, in 1975 the Association contacted administrators of two of the state’s largest hospitals with questions.Footnote 99 The administrators responded that it was their policy to not perform abortions except to save the mother’s life. Not satisfied, the Association requested face-to-face meetings “to determine whether the practice of the Hospital coincides with the Hospital’s policy.”Footnote 100 The Association also asked representatives of the United Fund whether any of the agencies they worked with were involved in abortion services. Finally, the NDRLA sent letters to the chair of the Fargo School Board as well as the school superintendent regarding school policy on abortion counseling.Footnote 101

The Abortion Control Act of 1975 and 1979

In 1975, the North Dakota legislature passed the Abortion Control Act to strictly regulate abortion while still complying with federal court decisions. The Act, introduced as House Bill 1295 and sponsored by four Republicans and a Democrat, passed the House 97-1 on January 31Footnote 102 and the Senate 44-5 on March 6.Footnote 103 It became law on April 11, without the governor’s signature. The stated purpose of the law was “to protect unborn human life and maternal health within present constitutional limits. It reaffirms the tradition of the state of North Dakota to protect every human life whether unborn or aged, healthy or sick.”Footnote 104

The Abortion Control Act had six components. Most notably, the Act required women to give their “informed consent” prior to an abortion:

“Informed consent” means voluntary consent to abortion by the woman upon whom the abortion is to be performed only after full disclosure to her by the physician who is to perform the abortion of such of the following information as is reasonably chargeable to the knowledge of such physician in his professional capacity:

-

a. The state of development of the fetus, the method of abortion to be utilized, and the effects of such abortion method upon the fetus.

-

b. The possible physical and psychological complications of abortion.

-

c. Available alternatives to abortion; namely, childbirth or adoption, or both.Footnote 105

Physicians had to give a written statement indicating they had made the mandated disclosures and that these disclosures had been understood. In addition, an unmarried minor seeking an abortion had to get written consent from a parent or guardian and then wait 48 hours.

Second, only a licensed physician could perform an abortion, and abortions performed after the first 12 weeks could only be done in a licensed hospital.Footnote 106 Physicians were expected to “preserve the life and health of a fetus which has survived the abortion and has been born alive as a premature infant viable by medical standards.”Footnote 107 Failure to do so was a Class C felony. Third, the Act banned medical practices from advertising abortion services to the public,Footnote 108 specifically communications with the purpose of “inviting, inducing, or attracting of a pregnant woman to undergo an abortion.”Footnote 109

Fourth, hospitals had to maintain records for at least seven years, including information on the physician performing the procedure and the status of the fetus. These records had to be submitted to the Department of Health within 30 days. Fifth, aborted fetuses had to be disposed in a humane manner “under regulations established by the department of health.”Footnote 110 In addition, “it shall be a class A misdemeanor for a person to conceal the stillbirth of a fetus or to fail to report to a physician or to the county coroner the death of an infant under two years of age.”Footnote 111 Finally, the Act formally repealed North Dakota’s old abortion statutes.

The NDRLA strongly supported HB 1295. Dr. Fortman testified before the House and Senate Judiciary Committees and met with Governor Link to argue for its passage even though the bill fell far short of ending abortion.Footnote 112 “This legislation does, however, to the limited degree that the state is permitted to act under the Court’s decision, afford some protection to maternal welfare, and some protection to the unborn child,” he wrote the governor.Footnote 113 Fortman felt that HB 1295 was the best that the legislature could do under the circumstances.

The legislature continued its work. On January 16, 1975, four Republicans and a Democrat sponsored House Bill 1294 to outlaw research using aborted fetuses: “No person shall perform or offer to perform an abortion where part or all of the consideration for said abortion is that the fetal remains may be used for experimentation or other kind of research or study.”Footnote 114 Violation was a class C felony. House Bill 1294 passed the House on January 27 by 96-1, the Senate on February 25 by 48-1, and signed by Governor Link on March 12.

On January 28, 1977, a Republican senator introduced Senate Concurrent Resolution 4043 urging “the Congress of the United States to exercise its power, granted under Section 2 of Article 3 of the United States Constitution, to limit the jurisdiction of the United States Supreme Court and to amend Section 242 of Title 18 of the United States Code to prevent deprivation of rights under color of law.”Footnote 115 The resolution was amended during its second reading to include a statement that “77 percent of those voting in the November 7, 1972 general election in North Dakota rejected abortion as an alternative to solving the problems of maternal and prenatal and natal health.”Footnote 116 The Senate adopted the resolution by voice vote on February 22, and the House voted 92-2 in favor on March 11.Footnote 117

The legislature revisited the Abortion Control Act in 1979 when two Democratic and two Republican representatives sponsored House Bill 1581 to make five revisions to the original Act.Footnote 118 First, informed consent now required the physician to describe “the probable anatomical and physiological characteristics of the unborn child,” the physical dangers and psychological trauma associated with abortion, and a more extensive listing of alternatives. Second, an adult woman would have to wait 48 hours after submitting her written consent before undergoing the procedure. Third, the parents of a minor seeking an abortion must be notified at least 24 hours before that minor can submit their written consent.

Fourth, an abortion of a viable child could only be performed in the presence of a second physician “who shall take control and provide immediate medical care for the viable child born as a result of the abortion.”Footnote 119 The physician performing the abortion and the second physician “shall take all reasonable steps” to keep the child alive. Finally, the records and reporting requirements were expanded.Footnote 120

The final version of HB 1581 passed the Senate 38-8 on March 21Footnote 121 and the House 74-20 on March 26.Footnote 122 It was signed by Governor Link on April 8. “On behalf of the pro-life movement of North Dakota, let me express to you our sincere appreciation that you saw fit to sign into law SB 2385 [see below] and HB 1581,” Dr. Fortman wrote to Governor Link. “These legislative actions are major steps in the responsible control of abortion and its practice in North Dakota.”Footnote 123

Abortion Funding in North Dakota

In the aftermath of Roe v. Wade, states were left to consider what responsibility, if any, they had in providing financial assistance to women seeking an abortion. Some states, such as Minnesota, were ready to use state funds to assist eligible women “as it would for any other operation.”Footnote 124 North Dakota proved less willing.

The state Social Service Board’s initial policy was to cover medical costs for eligible women who were referred to out-of-state facilitates.Footnote 125 “A number of eligible Medical Assistance recipients have obtained abortions in other states and we have paid for them because they are generally referred by North Dakota physicians,” wrote Richard Myatt, director of Medical Services for the Board. Many were for nontherapeutic abortions. The Social Service Board had sought clarification regarding its obligations from the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare shortly after Roe. A year passed before the Department finally declared that payments should be made in accordance with a state’s laws. Since North Dakota law at the time only allowed abortion to preserve the life of the mother, the Board announced on April 2, 1974, that Medicaid funds could only be used for therapeutic abortions.Footnote 126 The Social Service Board’s restrictions were challenged in federal court by a local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union and overturned. The Board modified its position on January 28, 1976, such that “it would pay for non-therapeutic abortions performed in accordance with state law.”Footnote 127

In 1977, Congress passed the Hyde Amendment, barring the use of federal funds to pay for abortions except to save the life of the woman or instances of incest or rape. Subsequently, on June 20, 1977, the Social Service Board declared a moratorium on the payment of all Medicaid abortions with the noted exceptions.Footnote 128 An October 20 memorandum added,

No payments will be made for any recipient of Medical Assistance on and after June 20, 1977 unless the following statement and signature of the attending physician appears legibly on the face of the authorization or claim form exactly as underlined below: I CERTIFY THE PREGNANCY OF (Recipient’s name) WAS TERMINATED OF MEDICAL NECESSITY BECAUSE HER LIFE WOULD BE ENDANGERED HAD THE PREGANANCY GONE TO TERM.Footnote 129

Only “prompt treatment for rape and incest victims before the fact of pregnancy is established will qualify for payment.”Footnote 130 Otherwise a physician would have to certify that the mother’s life was endangered.

On January 16, 1979, three Republican senators introduced Senate Bill 2385, the Abortion Accessibility Restricted Act, to establish that “it shall be the policy of the state of North Dakota that normal childbirth is to be given preference, encouragement, and support by law and by state action, it being in the best interests of the well-being and common good of North Dakota citizens.”Footnote 131 The bill prohibited (1) the use of state or local resources to pay for abortions unless to prevent the death of the mother; (2) the use of state or local resources to fund family planning organizations which perform, refer, or encourage abortions; (3) health insurance that provides abortion coverage as part of its basic policy unless done through an optional rider with additional charges; and (4) abortions in hospitals overseen by state or local government. Violation was a class B misdemeanor.

Originally, the bill included a section declaring that state and local resources could not be used for “a dilatation and curettage procedure in which the pathological examination of the surgical specimen indicates the presence of trophoblastic or chorionic tissue” unless the attending physician signed a statement indicating the procedure did not involve abortion.Footnote 132 However, support for this section proved weak in the House and so, on March 21, the House divided SB 2385 into four parts and voted on each separately. The portion requiring a physician statement lost 32-64. The Senate responded by dropping this requirement altogether and voting on the parts that passed the House. The revised bill passed 40-7 on March 26Footnote 133 and became law April 8.

Although Dr. Fortman praised the state legislature and governor, he warned,

[a]t the outset, let me pledge that this law shall not be used to interfere with the legitimate activities of family planning. We will, however, demand that the law be followed and respected… We reserve the right to monitor these clinics from time to time to insure that the provisions contained within this law are adhered to. Girls will be sent through the various clinics throughout our state for the express purpose of monitoring the activity within these planning units. If we find violations, we will first resort to reason, discussion and public disclosure to correct them. If these reasonable means do not succeed, we will be forced to resort to legal action.Footnote 134

The NDRLA would also keep watch over pro-life legislation and inform constituents “on the voting record of every legislator as we prepare to move into the 1980 election.”Footnote 135

Challenges to North Dakota Abortion Law

The Abortion Control Act in Federal Court

One of the most influential promoters of abortion rights in North Dakota during this period was Jane Bovard.Footnote 136 Born Jane French in 1943, her family moved to Minneapolis when she was in high school.Footnote 137 She married Richard Bovard and relocated to Fargo in 1972 after he accepted a position at North Dakota State University. Bovard became involved with such local groups as the Young Women Christian Association, the National Organization for Women, and the North Dakota Women’s Coalition. In 1974, she started an abortion counseling and referral phone service out of her home.Footnote 138 That same year, a representative of the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL) contacted her about opening a state chapter. On April 26, 1975, Bovard oversaw the organizing conference of the North Dakota Council for Legal Safe Abortion (NDCLSA).Footnote 139 The NDCLSA was incorporated as a 501 (c)(4) organization on October 6, 1975,Footnote 140 with Bovard as state coordinator, Leah Rogne of Kindred as vice president, Sharon Crass of Fargo as treasurer, and Jane Skjei of Fargo overseeing membership.Footnote 141 Using lists from supportive organizations, the group sent out a series of mailings, resulting in 75 dues-paying members by May 1977.Footnote 142

On September 28, 1976, the NDCLSA announced its first attempt at electoral politics with “an eleventh hour drive” to inform and influence candidates for office in the upcoming election.Footnote 143 However, the group did not endorse any candidates. Although the “eleventh hour drive” did not influence the results, it allowed Bovard to observe the antiabortion movement at work in North Dakota, which she summarized as part of a sworn statement for McRae v. Califano (1980).Footnote 144 By the end of 1979, the NDCLSA had nearly 200 members and a mailing list with over 400 names. “Bulk of the members are from the Eastern part of the state,” Bovard wrote in a 1979 report to NARAL. “Very few are from the rural western part of the state.”Footnote 145 The NDCLSA reported $2,148 in donations that year, with $550 from a single donor, a $500 NARAL grant, and $492 in dues.

Working with the Red River Valley Chapter of the ACLU, Bovard and Dr. Leigh challenged the 1979 amendments to the Abortion Control Act as well the section of the 1975 law banning hospital, clinics, and practitioners from advertising abortion services.Footnote 146 However, they did not challenge sections related to the protection of a viable fetus that is born alive because they did not have standing.

On July 9, 1979, Chief Judge Paul Benson of the District Court for North Dakota enjoined sections of the Act pertaining to informed consent, a mandatory waiting period, parental notifications for unemancipated minors, humane disposal of nonviable fetuses, and the solicitation of abortions.Footnote 147 The enjoined provisions were struck down altogether on September 26, 1980, with Leigh v. Olson. Footnote 148 The court determined that requiring a physician to describe “the probable anatomical and physiological characteristics of the unborn child at the time the abortion is to be performed” as well as “the immediate and long-term physical dangers of abortion, psychological trauma resulting from abortion, sterility and increase in the incidence of premature births, tubal pregnancies and stillbirths in subsequent pregnancies, as compared to the dangers in carrying the pregnancy to term” imposed undue burdens on a woman’s ability to have an abortion as well as intruding into the physician–patient relationship.Footnote 149

The court also declared the mandatory 48-hour waiting period to be an unconstitutional burden. It noted that Dr. Leigh was the state’s primary abortion provider, performing 2,500 abortions per year in his Grand Forks clinic. “Less than ten percent of his patients are from Grand Forks County, and many of his patients travel more than 200 miles from their homes to Grand Forks.”Footnote 150 The waiting period would result in not only “additional mental anguish” for those seeking abortions but also an economic burden. In addition, the court ruled that requiring parental notification for an unemancipated minor was “constitutionally defective because it violates the privacy rights of the minor and is an undue burden on the exercise of the minor’s right to an abortion.”Footnote 151 The court left it to the attending physician to exercise their medical judgement and determine whether the minor was mature enough to make their own decision or the parents should be notified.

The Court also declared unconstitutional the portion of the law stating that no person “shall advertise or participate in any form of communication having as its purpose the inviting, inducing, or attracting of a pregnant woman to undergo an abortion.” Not only did this violate the First Amendment; it was so vague as to violate the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.Footnote 152 The District Court agreed that the state has a legitimate interest in insuring the proper disposal of dead fetuses. However, the law did not clearly define what “humane” disposal involved or describe how fetal remains should be discarded. Instead, it required women to fill out a form stating, “I do hereby request that the fetus severed from the body of the undersigned be disposed of in the following manner: (1) Be delivered to the undertaker for (burial) or (cremation) (2) Be delivered to (name of hospital), for disposal at the hospital’s discretion.”Footnote 153 This requirement was also ruled an undue burden. Finally, those portions having to do with hospital recordkeeping as well as requiring doctors to inform patients of alternatives to abortion were allowed to stand.

In 1981, the state legislature revised the law so that an unmarried minor seeking an abortion needed either parental consent or authorization by a juvenile court judge. The judge would determine whether the minor was “sufficiently mature and well informed” to make such a decision.Footnote 154

The Abortion Accessibility Restricted Act in Federal Court

In 1979, Valley Family Planning challenged the Abortion Accessibility Restricted Act’s prohibition on the use of state funds by any entity “which performs, refers or encourages abortion” in the federal District Court of the District of North Dakota.Footnote 155 Valley Family Planning, a nonprofit organization, provided services across six counties and received more than 50% of its budget from federal funds distributed via the state of North Dakota.Footnote 156

Valley Family Planning neither performs abortions nor encourages its clients to obtain abortions. It does provide to women with problem pregnancies information on their legal options, including abortion. The staff members of Valley Family Planning explain to such women the procedures, risks and cost of abortion, the stage of fetal development, if asked for, and give the client the names of physicians in the area who perform abortions. Valley Planning does not contact the physician for the client.Footnote 157

Working with lawyers from Legal Assistance of North Dakota and the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation, the plaintiffs argued that such terms as “encourage” and “refer” were unconstitutionally vague and violated the First and Fourteenth amendment rights of Valley Family Planning employees. They requested a preliminary injunction against enforcement of the Abortion Accessibility Act. The court agreed, ordering an injunction on August 16, 1979.Footnote 158

The court declared the Abortion Accessibility Restricted Act unconstitutional on May 15, 1980, in Valley Family Planning v. State of North Dakota. Footnote 159 “The State of North Dakota has no constitutional duty to subsidize family planning programs,” Chief Judge Benson noted. “But when the state chooses to subsidize, it must do so subject to constitutional limitations.”Footnote 160 A recipient of governmental benefits cannot be required to give up constitutional rights to get those benefits. The law was ruled invalid under the Supremacy Clause. The decision was upheld by the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit on October 12, 1981.Footnote 161

Analysis

This study considered the political culture of North Dakota in relation to the evolution of state abortion law and policy over the 1970s. Elazar described North Dakota as having a moralist political culture with a predilection toward cultural conservatism. “In the moralistic political culture, individualism is tempered by a general commitment to utilizing communal—preferably nongovernmental, but governmental if necessary—power to intervene into the sphere of private activities when it is considered necessary for the public good of the community.”Footnote 162 Given their attitudes about abortion, North Dakotans would have expected a strong, negative response by the legislature and other political actors to Roe v. Wade. However, citizens in a moralistic political culture would also be expected to do more than just have opinions or cast the occasional vote: they should organize new groups as well as participate in existing groups with the goal of bringing about the good society regarding abortion.

This study produced three findings. First, opposition to the liberalization of abortion law in North Dakota by its citizens was deep-seated during the 1970s. Though North Dakota polling was limited, what polling exists suggests that a large majority disapproved of greater access to abortion before and after Roe v. Wade. In addition, the failure of the abortion liberalization measure in 1972 by such large margins provided state politicians with clear evidence of this disapproval. Consequently, citizens supported the legislature in its efforts to limit the influence of Roe v. Wade on North Dakota as much as they could. Indeed, state officials felt empowered to ignore Roe altogether until Leigh v. Olson (1974) forced the issue.

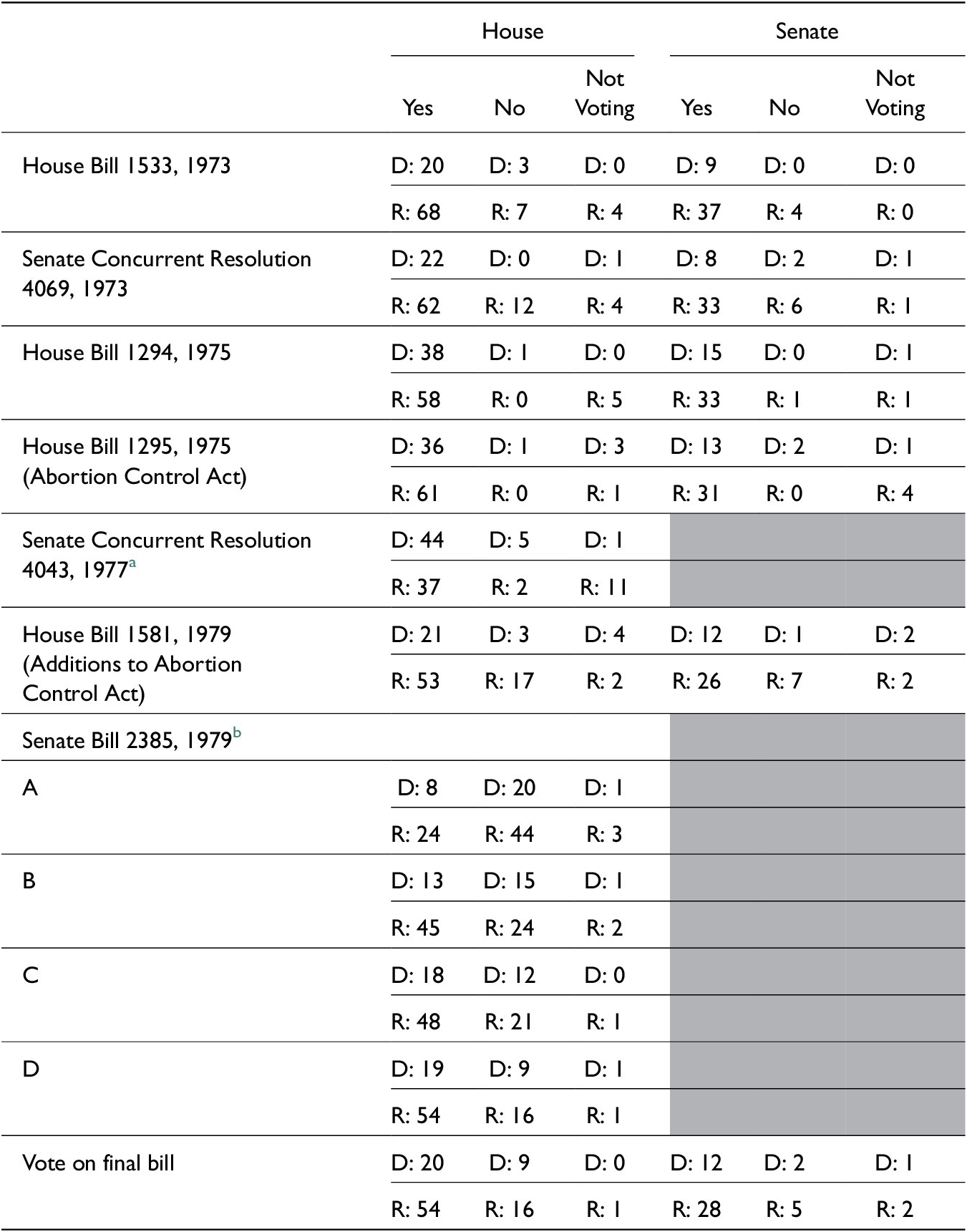

Second, support for these bills was bipartisan: whether Democrat or Republican, most legislators voted for statutes that either placed greater restrictions on access to abortion services or called on Congress to ban the procedure altogether. Although North Dakota is now a Republican-dominated state, this was not the case during the 1970s. Republicans made up 74.5% of the House and 78.4% of the Senate in 1973, 60.8% of the House and 66.7% of the Senate in 1975, 50.0% of the House and 64.0% of the Senate in 1977, and 71.0% of the House and 70.0% of the Senate in 1979. However, Democratics remained competitive and held the governor’s office from 1973 to 1981. Thus, both parties were politically relevant, and a determined party could likely stop a bill if it desired.

Table 1 presents the final votes for the seven abortion bills considered by the state legislature between 1973 and 1979. The partisan breakdown indicates that large majorities of Democrats and Republicans supported each bill, with the exception of Part A of Senate Bill 2385 in 1979. There are two explanations for this bipartisan support. The first is most obvious: Democratic and Republican politicians interpreted the 1972 initiative vote as representing the electorate’s true attitude toward abortion. Voters strongly opposed the initiative whether they lived in rural areas out west or urban centers along the Minnesota border. Consequently, neither party was predisposed to support abortion rights. The second explanation is related to the first: North Dakota was a culturally conservative state where opposition to abortion was strong before Roe and remained so in the years after. No matter their affiliation, elected officials shared this conservativism and were therefore prone to support restrictions.

Table 1. Support for Abortion Bills in the North Dakota General Assembly, 1973–1979

a The state senate passed Senate Concurrent Resolution 4043 via a voice vote.

b House split SB 2385 into four parts, passing three. The House then voted on a final bill consisting of those three parts. The Senate passed this abridged bill.

Third, befitting a moralistic political culture, a number of interest groups arose to pursue pro- and antiabortion policies in the aftermath of Roe v. Wade. The North Dakota Right to Life Association became the most influential due to its successful campaign against the 1972 measure. The margin of victory in that election was so impressive that the NDRLA became an example for antiabortion groups in other states to emulate.Footnote 163 However, this success nearly drove the organization out of business: after all, if abortion was settled policy, then what was the point of a right-to-life organization? The NDRLA responded by arguing for pro-natal policies, but these did not produce much excitement. The association seemed destined to fade away, but Roe v. Wade gave it renewed purpose.

Although the NDRLA was the most prominent antiabortion organization, other such groups formed during this time including Home Front,Footnote 164 Birthright,Footnote 165 Save Our Unwanted Lives (SOUL),Footnote 166 North Dakota Citizens Concerned for Life,Footnote 167 and Women Aglow.Footnote 168 In addition, the NDRLA and the North Dakota Catholic Conference encouraged the creation of pro-life committees in every parish. A network of antiabortion organizations soon covered the state. Given the political and cultural circumstances, it is little wonder that the NDRLA proved so successful at lobbying the legislature. The NDRLA would maintain its predominant position until the opening of a Fargo abortion clinic in 1981 caused supporters to question the organization’s tactics.

The 1972 initiative and Roe v. Wade also sparked the formation of women’s-rights-based organizations, such as chapters of the National Organization for Women in Fargo, Bismarck, and Grand Forks, the North Dakota Council on Abused Women’s Services, the North Dakota Council for Legal, Safe Abortion, the Coordinating Council for the Equal Rights Amendment, and the Rape Task Force.Footnote 169 Although each supported abortion rights, the NDCLSA became the most prominent pro-abortion organization.

With limited resources and a difficult political environment, the NDCLSA gamely tried to build support for abortion in the state legislature. Bovard regularly contacted legislators as well as the local media to reiterate the group’s opposition to bills under consideration.Footnote 170 She lobbied Governor Link,Footnote 171 Attorney General Olson,Footnote 172 and other officials on matters of abortion policy. In 1976, the NDCLSA urged supporters to turn out for party caucuses, noting that caucuses determined nominations and shaped party platforms.Footnote 173 Bovard also announced an “eleventh hour drive” to influence state lawmakers who were up for reelection. However, these attempts at a legislative strategy proved ineffective, largely because the NDCLSA was unable to build a mass movement in the state. Consequently, the organization had to pursue a legal strategy in the federal courts where the state’s political culture had much less bearing. This strategy proved to be much more successful, with Leigh v. Olson (1980) declaring whole sections of the Abortion Control Act unconstitutional. In conjunction with Valley Family Planning (1980), legal restrictions on abortion access in the state were eased significantly.

Conclusion

The early 1970s was a tumultuous time for abortion law and policy in the United States. These disruptions had a particular effect on North Dakota, which had experienced the defeat of a measure to liberalize abortion just 76 days before the release of Roe v. Wade (1973). As a result, North Dakota provides a useful case study of the development of abortion law at the state level during this period. Using a political culture approach, this study illustrates the ways the state legislature, interest groups, and the courts in North Dakota reacted to a series of disruptions in the area of abortion policy.

Political upheaval sparked the formation of pro- and antiabortion groups in North Dakota during the early 1970s. These groups sought to build popular and legislative support for new abortion policies. The political and cultural circumstances strongly favored the North Dakota Right to Life Association, which saw much of its agenda passed by the legislature with overwhelming bipartisan support. This allowed the state’s antiabortion movement to shape state law and policy within the parameters established by Roe. However, despite this success, Roe v Wade (1973) meant that abortion could not be banned outright. In addition, the North Dakota Council for Legal, Safe Abortion and other actors pursued a legal strategy that placed sharp limits and even overturned portions of state law and policy. Abortion became a continuing source of conflict in North Dakota politics.