Introduction

October 2024

As I brace myself for the impact of the cold water, I plunge and immediately feel that the water is warmer than I expected. I think about how long I can now go without a wetsuit. It is even longer than last year. And then I see them, the jellyfish bloom that has much perturbed the lady I just spoke to. Jellyfish in October, what is happening?

As the vignette above suggests, I am a frequent sea swimmer. I swim in water I know intimately and as such feel I know it and its inhabitants well. It is this embodied knowledge that heightens my awareness of changes that I can see, smell, experience, and touch in this space. For example, the presence of a jellyfish bloom in October is not something I ever remember. While jellyfish have always been part of my sea swimming in summer months, they are not usually present outside of that time frame. Equally, the length of time I can swim in the sea is increasing year by year because the water feels warmer. Where is the place for embodied and multisensory knowledge in a semiotic landscape approach to the Anthropocene? It is this question the article aims to answer.

As Smith (Reference Smith2025b) outlines, the Anthropocene nomenclature is heavily criticised and inherently problematic. Yet the term is widely accepted to refer to the impact humans have had on nature through the excesses of capitalism. The sea is a locus of such exploitation, and one can argue that in the Anthropocene era humans are in a chronically exploitative relationship with the sea. This is evidenced in a myriad of ways, including rising sea levels (Gehrels & Garrett Reference Gehrels, Garrett and Letcher2021), loss of marine species (Nimma, Devi, Laishram, Ramesh, Boddupalli, Ayyasamy, Tirth, & Arabil Reference Nimma, Devi, Laishram, Ramesh, Boddupalli, Ayyasamy, Tirth and Arabi2025), and increased waste in the sea (Thurlow Reference Thurlow, Kosatica and Smith2025). From an anthropogenic point of view, rising global sea levels is one of climate change’s most daunting properties, particularly when one considers that two-thirds of the world’s population live by the sea (Dermawan, Wang, You, Jiang, & Hsieh Reference Dermawan, Wang, You, Jiang and Hsieh2022). The United Nations General Assembly resolution recognised that ‘oceans, seas and coastal areas form an integrated and essential component of the Earth’s ecosystem and are critical to sustaining it…’ (United Nations General Assembly 2012:30).

Seascapes in the Anthropocene are overexploited and endangered sites (Jayalath & Ratnayake Reference Jayalath, Vithanage, Samarasekara, James and Reddy2025; Kaur, Thakur, Singh, Ramasamy, & Mudgal Reference Kaur, Thakur, Singh, Ramasamy, Mudgal, Prakash, Kesari and Negi2025). Coastal areas are often commodified as ecotopias, particularly so in the context of tourism where such spaces are promoted as ‘untouched imaginaries’ as described by Smith (Reference Smith2023). Coastal areas are marketed as idealised quiet spaces of escape from the dystopian realities of life in large urban environments, where images of a romanticised, idealised past where nature remains untouched abound. However, in the context of the Anthropocene, the reality for such coastal areas is that these spaces are far from utopian. They are complex socio-ecological systems where the anthropogenic interface between socio-economic development and environmental sustainability is keenly felt. Seascapes are thus characterised by their vulnerability to climate change. Vulnerability is a complicated theoretical concept on which several scholars have debated its strengths and weaknesses. In the context of this article, I use the term in line with Butler’s (Reference Butler2004, Reference Butler, Butler, Gambetti and Sabsay2016) approach to vulnerability in which she describes it as one of the most universal of all human conditions. As Butler (Reference Butler, Butler, Gambetti and Sabsay2016:14) suggests, we are ‘vulnerable to, and affected by, discourses that we never chose’. In applying Butler’s approach to semiotic landscape research, Moriarty (Reference Moriarty2025) highlights the need for a focus on the duality of vulnerability. Semiotic landscape research allows for an attunement to vulnerability but can also point to the resistance to vulnerability enacted by given actors, in given spaces. Thus, in arguing that the seascape is vulnerable, we can focus the attention on the local complex interaction between the various actors who work together to create a rhizomatic assemblage of climate vulnerability and resilience.

One way to begin to explore this, as Oppermann (Reference Oppermann2023) suggests, is to address this complexity. There is a need for transdisciplinary cooperation that encourages thinking with water and thinking together beyond the conventions of tentacular anthropocentric thought. This asks us to think disanthropocentrically, to decentre the human and foreground ‘the entangled web of interdependency of the human and more-than-human’ (Westgate Reference Westgate2023:76). To adequately address climate change, an engagement with the fluid, dynamic, and amorphous narrative of human–nature relationships are required. Semiotic landscape is an example of a lens that can be mobilised to offer one alternative view. The multisensory approach to the semiotic landscape I advocate for—where we move beyond the visual approach to semiotic landscape and incorporate embodied knowledge through feeling, touching, and smelling—is one way for semiotic landscape to build its contribution to climate change. To emphasise the multisensory and multispecies approach drawing human, non-human, and more-than-human examples is necessary, but I recognise that non-human and more-than-human are often used interchangeably; in this case, non-human refers to animate but not human and more-than-human to inanimate objects. From this perspective, this study promotes a rhizomatic assemblage approach to the study of the human, non-human, and more-than-human nexus that the seascape entails and adds to the growing literature of critical posthumanism approaches to socio- and applied linguistics.

Cornips, Deumert, & Pennycook (Reference Cornips, Deumert, Pennycook, Declercq, Brisard and D’hondt2024) suggest that posthumanism asks what our relationship is to the planet, to other animals, and to the objects around us, and re-evaluates ideas such as human agency, nature, language, and universalism. The posthumanism perspective helps us ‘to understand the multiple ways non-human entities are enmeshed in linguistic, social, cultural, material and political relations’ (Cornips et al. Reference Cornips, Deumert, Pennycook, Declercq, Brisard and D’hondt2024:171). Similarly, Lamb (Reference Lamb2024a:14), in his application of a multispecies approach to the semiotic landscape of monk seals in Hawai‘i, foregrounds the ‘possibilities for a multispecies approach to linguistic and semiotic landscape research that seeks to “multiply” our understanding of social life and meaning making in public space as a rich, multispecies entanglement’. The aim here is to add to this expanding body of work through an application of rhizomatic semiotic assemblage to map and understand the human-nature entanglements evident in the seascape.

In what follows, the concept of seascape—its origin, components, and how it should be understood in this article—are outlined. This is followed by a description of the MARA approach. First, an outline of why such an approach maps on to recent work in posthumanism approaches to rhizomatic semiotic assemblage is provided. Second, a multisensory semiotic landscape approach is foregrounded as a method to apply this approach to seascape research in the Anthropocene. MARA is then exemplified through a case study of a rhizomatic seascape of Ireland’s Wild Atlantic Way (WAW).

Seascape as an ordinary Anthropocene

The seascape has been studied extensively in disciplines such as cultural geography, maritime studies, and sustainability. Traditionally understood as a one-dimensional static space and passive backdrop for human activity due to its early representation in art, the seascape has evolved into a more fluid concept. This evolution has, as Pungetti (2002) notes, added to the complexity of defining exactly what the seascape entails.

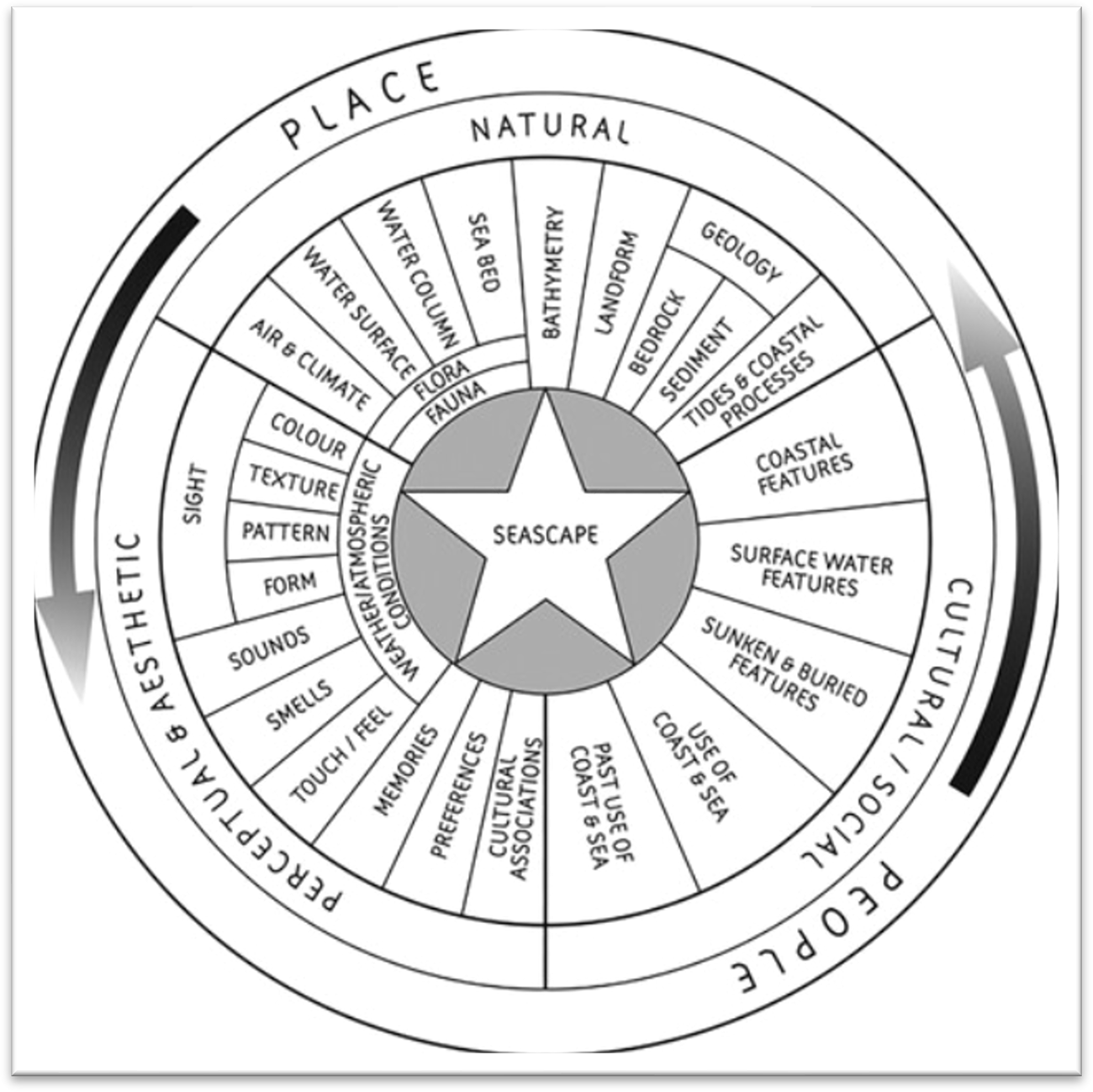

Jay & Acott (Reference Jay2023) provide a detailed account of the seascape as conceptualised by Natural England for the purposes of spatial planning. They foreground the notion of the seascape wheel (see Figure 1) as an apt means to capture the reality that the components of a seascape include human, non-human (fish, birds, plankton, etc.), and more-than-human (water, wind, sand) components. While it is beyond the scope of this study to examine the seascape wheel in detail, it provides a useful visual for understanding how the seascape is put forward here as human-nature entanglement. To ignore the non-human and more-than-human element is to foreground the human and to situate them ‘above’ the other components. An alternative to such an approach is what I aim to provide here.

Figure 1. The seascape wheel (from Jay & Acott 2023).

McNiven (Reference McNiven2024) provides a comprehensive overview of the concept of the seascape, and three key aspects of this account are pertinent when outlining how the seascape is conceptualised in this article. First, the term seascape encapsulates two dimensions that McNiven describes as ‘marine seascape’ and ‘terrestrial seascape’. In the present study, the terms seascape is used to encapsulate both dimensions. The ‘marine seascape’ is a view from within the sea, and ‘terrestrial seascape’ refers to both the ‘land’ adjacent to the sea (including beachscapes, coastal cliffs, and sand dunes) as well as maritime cultural landscapes (including rock art described in McNiven & Brady (Reference McNiven, Brady, McDonald and Veth2012) and the maritime souvenirs, such as those illustrated in Figure 3).

Second, the seascape is identified as locally meaningful and as a result requires a material and spatial engagement with the sea. It is widely accepted that anthropogenic-induced climate-change impact is a global condition described by Morton (Reference Morton2013) as a ‘hyperobject’. However, the reality is that it is felt and experienced at the level of lived everyday experiences, as Tsing (Reference Tsing2015:3) contends: ‘None of us live in a global system; we live in places’. It is this juncture that the present study links to recent work by Friedriksen (Reference Fredriksen2025), who proposes the term ‘anthropogenic ordinary’ as a means to understand planetary dynamics in the context of climate change and vulnerability through a focus on the ordinary and everyday experiences. She argues, ‘the Anthropocene becomes legible through particular, sensory and emplaced encounters between people and the tangled more-than-human worlds in which they find themselves’ (Friedriksen Reference Fredriksen2025:1). This approach is applied to the example offered in the case study where I focus on swimming with jellyfish.

A third dimension of McNiven’s account taken up here is the notion of agentive seascape. Here, I make a distinction between the two-dimensional passive ‘seascape’ and the ‘agentive seascape’, where the approach I put forward aims to examine from the bottom-up how the sea, with its non-human and more-than-human constituents, is an active agent of climate change, vulnerability, and resilience. This is taken up in the presentation of the examples offered in the case study. Here, the political economy of blue tourism in the context of Ireland’s WAW is discussed as an example of the limitations of a focus on a human-centred passive seascape. To focus only on the one-dimensional space equates the sea with an economic driver of blue tourism but fails to recognise the agency of the seascape to amplify or destroy that potential through rising sea levels. This is contrasted with two examples of the agentive seascapes and the affordability to resist climate vulnerability when the non-human and more-than-human are explored as part of a multispecies entanglement. In this case, I focus on jellyfish, waves, and sand dunes as examples of the non-human and more-than-human, respectively.

The connection between the Anthropocene and the seascape lies in the recognition of how human activities have transformed the marine environment and impacted the seascape but also foregrounds the agency of non-human and more-than-human nodes in reconfiguring this relationship. For example, as the case study shows, a focus on sand dunes, jellyfish, and tourism interactions with the seascape form a rhizome through which climate vulnerability and resilience can be examined.

I argue that the application of this latter dimension foregrounds the seascape as a relational force that co-produces ecological, social, and political realities. This approach connects to Latour’s (Reference Latour2018) ‘Parliament of things’ which invites us to consider how entities like the sea might ‘speak’ or exert influence in assemblages that include, in this case, government policies, jellyfish, sand dunes, and swimmers. This involves not only mapping the entanglements of human and non-human actors but also reconfiguring the seascape as a deliberative space, a site where decisions should be made not just about the sea, but with the sea. This aligns with recent posthumanism and new materialist scholarship that seeks to decentre the human and recognise the distributed nature of agency (as per Lamb Reference Lamb2024b; Smith Reference Smith2025a; Thurlow Reference Thurlow, Kosatica and Smith2025).

In working towards the development of a framework to investigate the seascape as a multispecies entanglement, I wish to foreground MARA, which stands for mapping and applying rhizomatic assemblage, to capture the shifting rhizomatic movements of the human, non-human, and more-than-human entanglements evident in the seascape. Although not an element that is discussed in this article, it is important to point out that MARA is also the Irish language term for seascape, and it links to the significance of indigenous linguistic heritage to climate sustainability, another node worth considering in a more comprehensive approach to the seascape. Dovchin, Dovchin, & Gower (Reference Dovchin, Dovchin and Gower2024) offer a comprehensive account of the significance of indigenous heritage in posthumanist approaches to applied linguistic research.

MARA: Mapping and applying the rhizomatic assemblage of the seascape

This intermingling and relationality of the human and non-human agency can be approached by the application of rhizome thinking (Deleuze & Guattari Reference Deleuze and Guattari2004), where a rhizome is a metaphor for a mode of thinking that resists fixed structures and embraces multiplicity. Rhizome thinking has previously been employed in the study of language and society by scholars including Pietikäinen (Reference Pietikäinen2015) and Milani & Levon (Reference Milani and Levon2016), who argue for its utility as an approach of the complex dynamics that underscore the movement away from modernist thinking of fixity to that of fluidity and mobility. In the context of rhizome thinking, the seascape is understood as a fluid, multispecies entangled system, where the porous boundaries between the human, non-human, and more-than-human are in a constant state of flux.

In adding the semiotic assemblage to the rhizome approach, scholars such as Canagarajah (Reference Canagarajah2018) and Soica & Metro-Roland (2002) address both linguistic and non-linguistic sources that intersect across temporal and spatial contexts. The term assemblage in this context refers to the coming together of diverse elements or entities and implies the emergence of a complex system through the connections and interactions of its constituent parts. Dewsbury (Reference Dewsbury2012:150) notes that assemblage ‘operates not as a stable term but as a process of putting together arranging and organising the compound of analytical encounters and relations’.

A posthumanist approach to social semiotics (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2017, Reference Pennycook2018, Reference Pennycook, Burkette and Warhol2021) enables us to treat natural landscapes, such as seascapes, as intra-actively constructed (see, for example, Soica & Metro-Rolands (Reference Soica and Metro-Roland2022) for work on the linguistic landscape of nature trails; see also Lamb Reference Lamb2024a; Baiqi Reference Baiqi2025; Smith Reference Smith2025b). Cornips (Reference Cornips, Cutler, Røyneland and Vrzić2024, Reference Cornips2025), drawing on a multispecies ethnography of dairy cows, highlights that in an assemblage perspective the focus should not be a discrete and fixed entity but, on viewing each entity, as an emergent and distributed formation. She argues that both the human and non-human have the potential to enact agency where ‘things and objects are connected in a recursive relationship: not only do people (and non-humans) make things, but things also make their (socio-culturally mediated) capacity to act and influence other human and non-human actors’ (Gibas, Pauknerová, & Stella Reference Gibas, Pauknerová and Stella2011:24, quoted in Cornips Reference Cornips2025). In this way, the actors and processes that are inscribed in the semiotic resources of an assemblage have the potential ‘to influence the terms of debate within that assemblage’ and reshape how the assemblage functions (McFarlane Reference McFarlane2011:661).

In applying such thinking to the seascape, I return to Latour’s (Reference Latour2018) notion of distributed agency and add that the potential of the rhizomatic assemblage of the seascape is the capacity to enact a form of ‘disruptive agency’ (Bennett Reference Bennett2010:21). To disrupt the normative thinking that climate change is a simple cause-and-effect relationship to which humans only have the capacity to respond and to bring the non-human and more-than-human agency into the discussion may allow for a more nuanced understanding of climate vulnerability and resilience.

Methods: A multisensory semiotic landscape approach

In keeping with the ethos of assemblage thinking, the methodological approach to MARA requires an interdisciplinary methodology that foregrounds relational thinking. In the context of the case study offered here, the WAW, a government-designated tourist driving route along Ireland’s west coast, provides the locus for this exploratory application of MARA. The case study traces how tourism infrastructures, local communities, marine species, and other natural forces co-constitute this example of a seascape as a dynamic and ever evolving assemblage, which, in the context of the political economy of tourism, experiences enhanced climate vulnerability but also exhibits an ability to become resilient.

Kirksey & Helmreich (Reference Kirksey and Helmreich2010) foreground an emerging multispecies ethnography that encouraged researchers to let the non-human and more-than-human speak for themselves. Such an approach has been applied in semiotic landscape research in Lamb (2024) and Cornips (Reference Cornips, Cutler, Røyneland and Vrzić2024, Reference Cornips2025), among others. In taking this as a methodological starting point for the application of rhizomatic assemblage thinking to the seascape, a mixed method toolkit is presented in which I advocate for a multisensory semiotic landscape approach. To fully appreciate the rhizomatic assemblage of the seascape, it is insufficient to simply map its visual manifestations, one also needs to account for how it feels, smells, and sounds.

Based on this approach, data were gathered using a framework that included swimming, walking on coastal sites, and driving the WAW as methods to capture the semiotic landscape from within, beside, and above the seascape. Both walking (Oyama, Moore, & Pearce Reference Oyama, Moore, Pearce and Melo-Pfeifer2023) and drive-by (Hult Reference Hult2014) methods have been used in previous semiotic landscape studies. The application of swimming as an embodied method for semiotic landscape research is an underutilised methodology. In the swim-along method, swimming is seen as ‘sensory experience, embodiment, emplacement about what changes and what stays the same, and about the configuration and recognition of assemblages of objects, people, ideas and information’ (Büscher & Urry Reference Büscher and Urry2009:110). To become sensitive to the changes in the seascape requires an embodied interaction with the sea. Through embodied and semiotic submergence in the sea, our capacity for what we ‘know’ shifts. As Foley (Reference Foley2017:44) argues, ‘the swimmer literally shifts from being a subject to becoming a co-subject within the object’. The focus on thinking in and with the sea, much like that of Lamb’s work on the beachscape, estranges us from human-centred ontologies.

Participant observation and field notes become important methods for documenting and noticing how these elements of the rhizome bear witness to climate change. In the context of the present study, participant observation was conducted using a walking method in which I combined the collection of images with note-taking of the observations made of the view from the shoreline. Similarly, I took the sensory approach into the water and used an embodied approach to the collection of data within the sea, which consisted of images, field notes, and a researcher diary. The vignette presented at the beginning of the article is an example of this. Walking and swimming are seen as a non-linear emergent mapping of the nodes of the rhizome.

The human-centred data were collected from two sources. One was a virtual semiotic mapping of the top–down tourism sites used to market the WAW. The second involved a drive-by approach to document what you see as you drive through given stages of the tourist route. The non-human and more-than-human data include images and field notes of what is seen and touched in the seascape. Specifically, I include data from a focus on waves, sand dunes, and jellyfish.

To date, I have documented the southwestern route most extensively, and it is from this site I draw much of the data presented in this article. The rationale for focusing on this area is personal: it is the area I grew up in, and so I have an intimate knowledge of the archive of the seascape in my own lifetime, and as such it epitomises the ordinary Anthropocene approach. It is this knowledge that drew me towards the inclusion of the sea; my own embodied action of swimming in this sea provided evidence of the significance of and the rate of anthropogenic-driven change, and how both we humans respond to, but also how the waves, sand dunes, and jellyfish, as equally important rhizomes in this seascape assemblage, respond to climate vulnerability and enact their agency to resist.

Case study: MARA applied to the rhizomatic assemblage of the WAW

To give direction to the understanding of the rhizomatic assemblage, the remainder of this article applies it to a case study of blue tourism and the seascape in Ireland. Blue tourism broadly refers to tourism areas and activities that centre around, in, and with water. It is described by Ndhlovu, Dube, & Kifworo (Reference Ndhlovu, Dube and Kifworo2024:14) as a form of tourism ‘that is intrinsically linked to marine and coastal environments, encompassing a wide range of activities—recreational, cultural, ecological, and economic—within oceanic and littoral spaces. It is shaped by the interplay of environmental sustainability, socio-economic development, and cultural heritage, and is increasingly influenced by digital technologies and climate change imperatives’. This definition reflects the evolving understanding of blue tourism as not just a source of leisure but also deeply embedded in sustainability discourses and complex socio-ecological systems. Yet when one examines the rationale for blue tourism initiatives, it becomes clear that a failure to think ‘with’ the non-human and more-than-human elements that make up such seascapes is added to the vulnerability of these spaces. It is at this interface that the current study is placed. Ireland, as a small island nation, relies on tourism to secure the economic future of the country’s more rural coastal towns and villages. The sea is the most important commodity for these areas and is subject to use and abuse by the tourism industry. One key example of this is a blue tourism initiative knows as the WAW that was undertaken by Fáilte Ireland, Ireland’s national tourism body, to encourage tourism beyond key urban sites to the rural maritime communities. According to Fáilte Ireland, the WAW is ‘synonymous with great experiences of Atlantic heritage, culture, landscapes and seascapes in a high-quality environment’ (Fáilte Ireland 2015:5).

The WAW is a self-guided driving route along the western seaboard of Ireland. It is the longest defined coastal route in Europe spanning 2,500 km, and it takes in 517 coastal communities and promotes 159 discovery points that offer the potential for an intimate experience of the wild nature. WAW is marketed as a niche product chosen by sustainability sensitive travellers seeking contact with nature and tranquillity. It maps sites for recreation, tourism, food, provision, and traditional cultural practices and has allowed for local ecotopian experiments such as slow food movements, re-wilding of spaces, foraging and seaweed cultivation, and wild swimming as linked to individual peace. It is marketed to both international and domestic tourists as a space you return to and one that has something to offer 365 days a year.

It is celebrated as one of the country’s most successful blue tourism initiatives designed to attract tourists outside of key sites to more remote, rural, and ‘authentic’ parts of the country. WAW is framed as contributing to the well-being of coastal communities through trickle down economies, but this comes with limited actions to ensure sustainability of the very resources drawn on to promote this ecotopia. For example, there are limited public transport options for visiting the route, and the campaign actively promotes it as a drive. But a significant increase in tourist numbers brings with it an increase in traffic to spaces previously unimpacted by traffic congestion, with little care given to the ecological impact of such increases. Yet, this human-centred approach is at a disjuncture with the reality that Ireland’s WAW is dynamic seascape shaped by the North Atlantic drift and seasonal storms (such as El Niño), and has a rich biodiversity including marine animals, coral reefs, kelp forests, and migratory seabirds. A seascape that can and does exert an agency of its own—for example, rising sea levels—are indicative of the sea’s capacity to disrupt the economic success of this initiative.

Example 1: Blue tourism as human centred Anthropocene ordinary

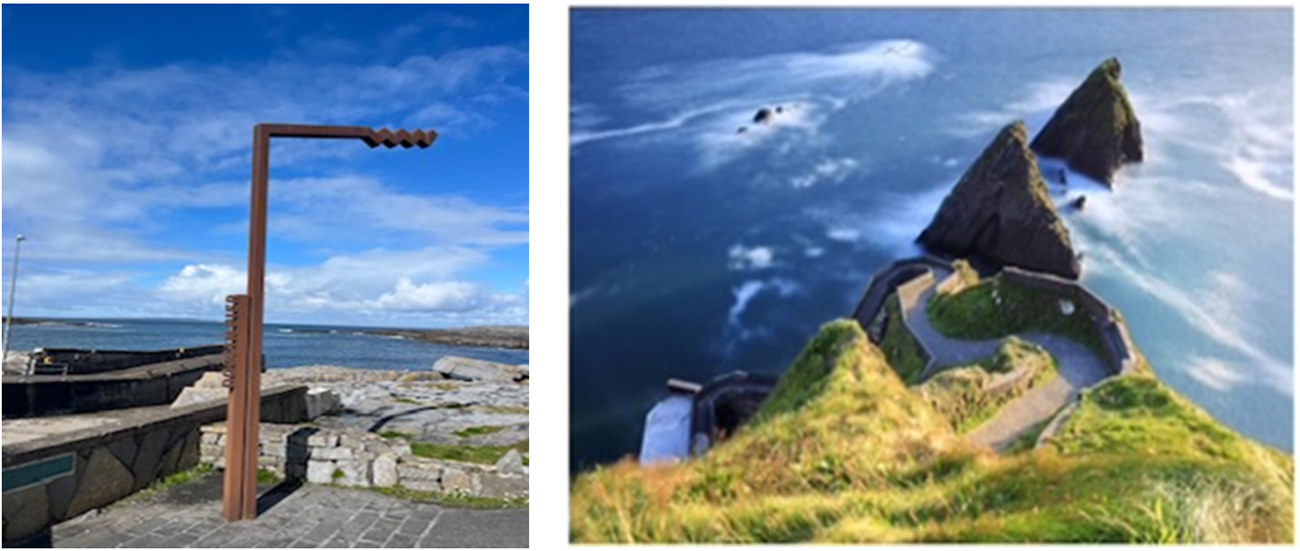

For policy officials involved in the development of blue tourism initiatives such as the WAW, the seascape is a commodity to be leveraged in the pursuit of economic gains. Evidence of how the WAW was conceived by marketers, who for the most part live in urban centres, is evident in both the physical and virtual semiotic landscape where an ideology of consumption of real and authentic experiences by the sea is foregrounded. The essence of the branding lies in the proximity to authentic experiences by the sea where locations along the WAW are branded as quiet, peaceful, and remote from the hectic nature of urban life. Figure 2 presents images from the official website that promotes the WAW.

Figure 2. Wild Atlantic Way and the political economy of pristine nature.

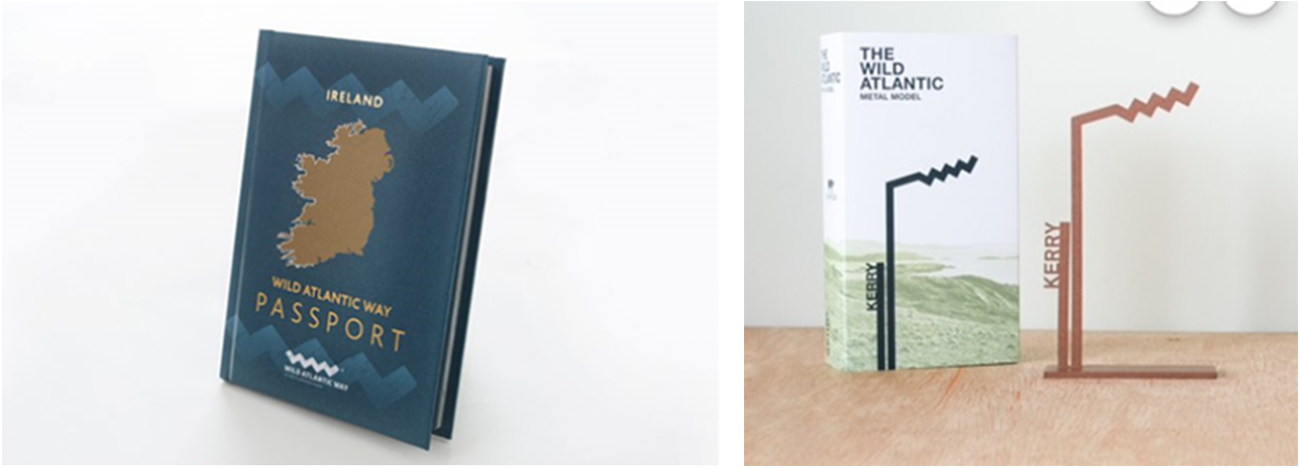

The images presented in Figure 3 show how the WAW is commodified. Road signs ensuring tourists stay on the right route mark the semiotic landscape along the entirety of the WAW, and tourists are encouraged to return to the WAW through the collection of memorabilia including photographs at each of the 159 sites and the collection of stamps on a WAW passport. Each of the 159 designated sites of interest are marked by metal signs that are intended to be collected by tourists, both in terms of images taken at these signs but also in the purchasing of small plastic replicas of these signs.

Figure 3. WAW souvenirs as political economy of terrestrial seascape.

Figure 3 exhibits this through the ‘thingification’ of the seascape, to borrow from Urla’s (Reference Urla, Duchêne and Heller2012) account of the ‘thingification’ of language. The passport and related souvenirs, made from unsustainable materials, are to be gathered by tourists as they drive by pristine nature. In this way, WAW is an example of structural unsustainability in the context of a semiotics of sustainability (Smith Reference Smith2025a).

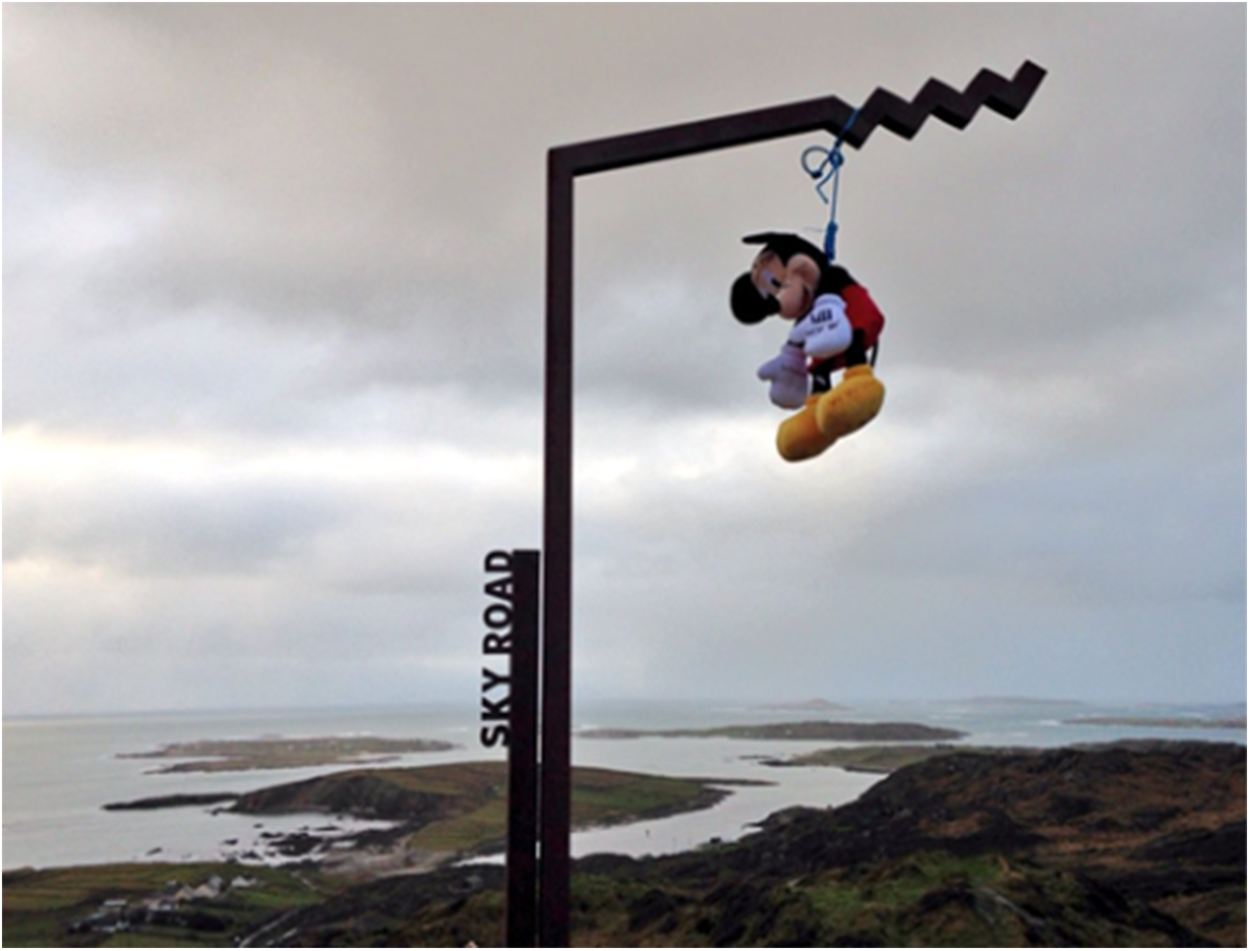

These spaces along the WAW are also examples of ordinary Anthropocene for the permanent residents. Figure 4 suggests, despite the clear economic gains for these areas, that there are some locals who object to the intensification of tourism in the context of scarcity of resources and the potential impact on the local maritime community.

Figure 4. Humans attune to the Anthropocene ordinary.

Figure 4 provides an example of the human and more-than-human nexus. The local community is thinking with the local environment. They are attuned to the impact of the increased tourism not only on their own lived experience but also on the sustainability of the resources within this seascape. WAW locals have resisted what they see as the Disneyfication of the seascape. For these communities, they object to how the seascape is conceived of in marketing campaigns and see the sea not as ‘capital’ for advertising executives but as a fundamental life-providing resource.

Figure 4 offers a glimpse of the beginning of a human/non-human interaction through the local objection to the increased pressure this blue tourism initiative is having on the local environment. It highlights an exposure to capitalist ideals that makes the environment more susceptible to subjection of climate vulnerability. To come back to Tsing’s (Reference Tsing2015) idea that the local experience is valuable to sustainability discourses, this example shows how the local community is more ‘attuned’ to the need to work with nature. The next example brings sharper focus to attunement.

Example 2: Attunement to the more-than-human and walking the seascape

In foregrounding a walking methodology along the shoreline, the border of the terrestrial and marine seascape, my focus is on what becomes visible when I am attuned to the movement of the sea through the ebb and flow of the tide and the movement of the waves. I was immediately struck by two important sights. The first is to the presence of large bodies of waste, a human induced hazard, that is swallowed by the waves and taken to sea with the potential for harm to marine life and wider ecology as well as to humans who may eventually ingest a fish that contains microplastics. While I do not attempt to map the waste presented in Figure 5, I present it as a view from the water’s edge.

Figure 5. Human hazards and the seascape.

These images are at odds with the pristine untouched image of the WAW presented in the top-down promotional material (see Smith Reference Smith2025b for a further example of the impact of trash on the human perception of pristine nature). Yes, it is visually displeasing, but the imminent consumption of waste by the waves is more problematic. It exemplifies the seascape’s vulnerability to human-induced hazards. For a more comprehensive account, see Thurlow (Reference Thurlow, Kosatica and Smith2025) who provides an example of the trajectory of plastic bottles in, on, and near water as an example of this multilayered entanglement of the water and waste with wider patterns of sustainability.

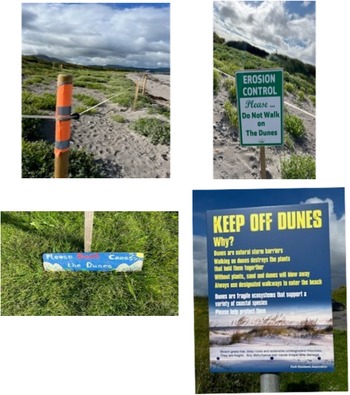

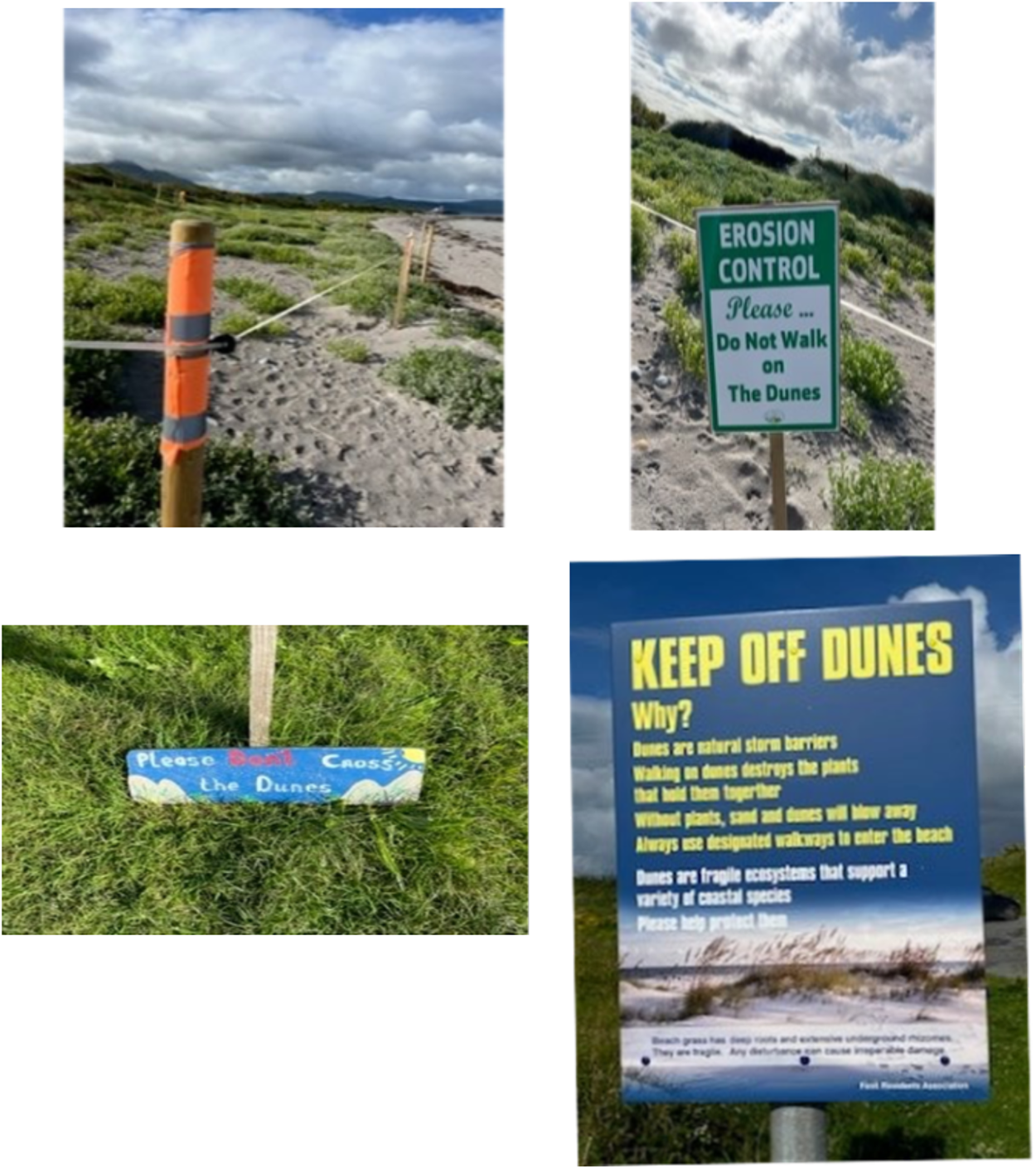

The second factor I am drawn to is a series of signs and other semiotic resources erected by humans in an effort to protect the local sand dune system that has been significantly damaged both by the waves and by human traffic on the dunes. Sand dune systems are an important mosaic of grasslands and shrubs and protect humans and animals alike. Sand dunes epitomise rhizomes, as there are no central organising components; sand dunes are self-regulating and highly adaptive.

These images are relevant to multispecies entanglement for the following reasons. First, Figure 6 exemplifies the type of disturbed agency related to Latour earlier in this article. The sand dunes ‘grieve’ through the wave-induced erosion, and the humans, through the enactment of their own agency to protect the sand dunes, express their attunement to the fate of the sand dunes. Each of the examples in Figure 6 are the actions of local community groups. In a way, this exemplifies from the human perspective the emotional process of solastalgia at play in the semiotic landscape—where solastalgia is understood as the emotional distress caused by environmental damage that is most keenly felt when it affects one’s home or sense of place (Albrecht Reference Albrecht2005). From a multispecies perspective, the waves, sand dunes, and humans represent an emerging climate resilience when entanglement of place and species mobilises action, care, and resistance. In attuning to the ordinary Anthropocene of the waves and the sand dunes, the need for further examination of solastalgia becomes apparent.

Figure 6. Human and more-than-human nexus in the seascape.

Example 3: Embodiment and climate resilience of jellyfish

In this last example of the application of MARA, I return to the jellyfish that I referenced in the opening vignette. Jellyfish are often cited as emblematic of the anthropogenic impact on the sea, though some scholars remark on the need for more robust evidence to situate this claim on a global scale. In the context of Ireland, there is an increasing presence of jellyfish both in terms of volume and species in Irish waters, and this has been attributed to degraded ocean environments brought about by anthropogenic change (e.g. overfishing, eutrophication, and warming seas; Lynam, Lilley, Bastian, Doyle, Beggs, & Hays Reference Lynam, Lilley, Bastian, Doyle, Beggs and Hays2011; Kennerley, Lorenzoni, Luisetti, & Wood Reference Kennerley, Lorenzoni, Luisetti and Wood2021). The increase in jellyfish blooms and massive arrivals of jellyfish is often remarked in the Irish media as spectacular but is concerning in terms of the risk to humans (stinging) and on blue tourism. Roca, Tuya, Goméz, & Machìn (Reference Roca, Tuya, Gómez and Machín2025) describe the impact of increased jellyfish stings on blue tourism in Mallorca.

The images presented in Figure 7 are examples of jellyfish I co-inhabit the sea with when I swim. I see them, feel them, and aim not to have the boundary between us punctuated by a sting. While their presence does heighten my own vulnerability in the water—a space swimmers firmly recognise as a more powerful space—I am struck by their ability to survive.

Figure 7. Non-human components of the seascape as vulnerability and resilience.

Figure 7 highlights the capacity of the non-human to encapsulate climate vulnerability and resilience simultaneously. Despite this negative impression of jellyfish, the reality is that they are a hugely important element of the sustainability of ocean biodiversity. They are important hosts for smaller marine species (e.g. sprat, crabs), while jellyfish are also important sources of food for larger fish and turtles (cf. Lee, Tseng, Yoon, Ramirez-Romero, Hwang, & Molinero Reference Lee, Tseng, Yoon, Ramirez-Romero, Hwang and Molinero2023). Figure 7 shows a large compass jellyfish doing its job of protecting other creatures (within the large mass below its main body) in the WAW seascape. On the one hand, jellyfish are living indicators of the degradation of the sea, but on the other, they are symbols of the possibility to adapt and adjust to the agentive resilience. Jellyfish can stand as a metaphor for a more hopeful future; they can survive due to an ability to adapt to new conditions.

Rather than viewing jellyfish solely as invasive disruptors, a more-than-human perspective invites us to consider their role in shaping semiotic landscapes—where meaning is co-produced by human and nonhuman actors. For instance, jellyfish blooms alter sensory and affective experiences of the sea, influencing fisheries, tourism, and public perception, while also signalling shifts in oceanic health. This aligns with Purcell’s (Reference Purcell2012) call for a more holistic understanding of jellyfish as ecological participants rather than anomalies. Such an approach challenges anthropocentric narratives and opens space for multispecies storytelling, where jellyfish become mediators of environmental knowledge, resilience, and change. Jellyfish do not resist climate change; they move with it and adapt an approach that may prove beneficial to human approaches to climate change. Such an approach challenges anthropocentric narratives and opens space for multispecies storytelling, where jellyfish become mediators of environmental knowledge, resilience, and change.

Discussion

The multispecies and multisensory approach to the study of the seascape as a rhizomatic assemblage in the context of climate change has attempted to offer an alternative to the human-centred view. This reductionist view obscures the ecological entanglements and semiotic vitality of the sea. A human-only approach is indicative of the extractive logics that produced the Anthropocene, which further highlights the need to think ‘with’ nature. In adding a focus on non-human and more-than-human actors—namely, waves, sand dunes, and jellyfish—this rhizomatic assemblage approach to the seascape engages Haraway’s (Reference Haraway2016) call to ‘stay with the trouble’. Climate change is a messy and entangled reality, and resistance to it can only be brought about by viewing the elements as co-constitutive agents.

The three examples discussed here are trans-scalar (global–regional–local) multisensory networks that coproduce climate vulnerability and resilience. Of course, we cannot ignore the wider structural (anthropogenic) forces of coloniality, capitalism, and extractivism that have produced the climate vulnerability. Such an understanding could be seen as a naive attempt to romanticise and depoliticise climate discourses. But to attune to uneven vulnerabilities and resilience is to recognise the complexity of the rhizomatic assemblage of seascape. Recognising these forms of non-human resilience does not negate human vulnerability; rather, it reframes resilience as a shared, distributed, and relational process—one that is essential for imagining more just and sustainable futures in coastal Ireland and beyond. The resilience identifies how a focus on the ‘Anthropocence ordinary’ enables a place-sensitive ecology of care. There is no environmental justice without multispecies engagement.

Conclusion

In the context of climate change, this seascape is under pressure. The rise of the sea levels, the acidification of the sea, and the growth of invasive species (like jellyfish) are all manifestations of climate vulnerability that has both social and ecological consequences. As I have argued previously (Moriarty Reference Moriarty2025), we need to think about vulnerability in terms of its relation to resilience and hope. In the context of climate vulnerability, resilience is not a properly isolated entity but an emergent quality of the whole system: the human, non-human, more-than-human, material, and symbolic. As the application of MARA to the WAW has demonstrated, the rhizomatic assemblage approach offers an exploratory, theoretical, and methodological framework for foregrounding a multispecies and multisensory approach.

In terms of a multispecies approach, this study invites a rethinking of the human, non-human, and more-than-human nexus that the seascape encapsulates, and it becomes clear that knowledge about climate change, climate vulnerability, and resilience to such vulnerability is embedded in contingent multispecies assemblages. As the case study examples have illustrated, this nexus is evident in the seascape of the WAW. For example, the locals contest the Disneyfication of the WAW, they work with nature to protect the sand dunes, and they can see the jellyfish as a species capable of resisting climate vulnerability through their adaptive behaviours. As result, this approach frames climate resilience as a disturbed and shared process across this multispecies entanglement. Reimagining the seascape as a rhizomatic semiotic assemblage allows for a more inclusive, ethical, and ecologically attuned understanding of blue tourism. It challenges the dominance of political economy frameworks that marginalise non-human agencies and calls for multispecies justice.

A semiotic landscape approach to climate vulnerability reveals how meanings are constructed, contested, and mobilised in the face of environmental crisis. A multisensory semiotic landscape approach to climate vulnerability adds an ability to examine how climate change is being felt, seen, heard, and lived. As the second example in the case study has shown, the climate vulnerability of sand dunes prompts a human reaction and intervention to work with the sand dunes to protect them. In further developing a multisensory semiotic landscape, I encourage the use of more embodied and situated methods of research. In addition to the already growing body of semiotic research that focuses on smellscapes (Pennycook & Otsuji Reference Pennycook and Otsuji2015), among others, affective mapping is another potential route to add to a multisensory semiotic landscape toolkit.

Embracing complexity, rejecting hierarchies, and foregrounding relationality provides a more accurate and ethically grounded understanding of climate vulnerability. In a time of ecological crisis, such a shift is not only intellectually necessary but morally imperative. By situating blue tourism within a rhizomatic and post-anthropocentric framework, this study challenges anthropocentric and economistic narratives, advocating for relational ethics that recognises the co-constitutive agency of human and non-human actors in the making of seascapes. This approach challenges the anthropogenic desire for control, prediction, and mastery and foregrounds a need to be receptive to feelings of uncertainty.