Introduction

This article presents a critical synthesis of recent and ongoing archaeological work in Byzantine Thrace from the seventh to the fourteenth century, with a particular focus on developments across Bulgaria, Greece, and Türkiye from the past decade. Through the examination of systematic excavations, regional surveys, and interdisciplinary research initiatives, we highlight how these efforts have deepened our understanding of the region’s complex historical landscape. Special attention is given to key thematic concerns shared across projects, including long-term human–environment interaction, evolving settlement patterns, and dynamic urban–rural connections. Collectively, these findings have enriched the archaeological record and led to significant revisions of long-standing historical interpretations.

Alongside new fieldwork, a growing wave of publications has reassessed earlier discoveries and legacy data. These re-evaluations, often based on archival material, unpublished site reports, or understudied assemblages, seek to contextualize previously isolated finds within the broader socio-political and economic frameworks of Byzantine Thrace. This includes both landmark monuments and lesser-known sites, now integrated into wider interregional and imperial narratives. Such efforts have reinvigorated scholarly interest in the historical region of Thrace and made previously inaccessible data available to a broader audience.

Recent discoveries and specialized studies, from ecclesiastical architecture and urban planning to ceramic production and burial practices, further illuminate the region’s social, religious, and economic transformations. These contributions reveal Thrace not as a marginal hinterland, but as a strategically vital and multifaceted province, shaped by maritime and inland routes, its geopolitical role, and its internal regional diversity.

This review also underscores the urgent need to overcome modern political boundaries that have long fragmented the study of Thrace across Greece, Bulgaria, and Türkiye. Although notable exceptions exist, collaborative research and dialogue across national borders remain limited. Yet the historical region of Thrace cannot be fully understood without a transnational approach. Major Byzantine cities are being excavated across all three countries, but the lack of coordinated frameworks often prevents meaningful comparison or synthesis. As a result, crucial questions remain underexplored: what role did Thrace play in different centuries? How did its settlements relate to networks like the Via Egnatia or imperial grain routes? And how did its environmental diversity shape distinct regional and micro-regional trajectories? Although this report is not exhaustive, it aims to reframe Thrace not as a monolithic grain-producing plain, but as a mosaic of interconnected microregions, each with its own ecological, economic, and cultural profile.

While the body of work grows, Byzantine Thrace remains underrepresented in broader Mediterranean discourse. Its settlements are too often treated in isolation, overshadowed by better-known regions such as Cappadocia or the Peloponnese. This imbalance reflects gaps in scholarly synthesis, not a lack of historical significance. By bringing disparate projects and datasets into dialogue, we aim to show how Thrace’s rich, varied, and interconnected landscapes offer immense potential for understanding the Byzantine world.

The current wave of research in Byzantine Thrace builds upon a foundation laid by earlier pioneering studies calling for integrated, cross-regional, and transnational approaches. Among these, the work of Charalambos Bakirtzis and Robert Ousterhout stands out. Their landmark volume on the monuments of the Evros River valley (Ousterhout and Bakirtzis Reference Ousterhout and Bakirtzis2007) was the first to systematically document and interpret sites on both sides of the modern Greek–Turkish border. By situating these monuments within broader regional and transregional frameworks, they demonstrated that the river valley functioned historically not as a dividing line, but as a vital artery of movement and exchange. Bakirtzis also played a catalytic role in organizing two major international symposia on Byzantine Thrace, which brought together scholars from across southeastern Europe. The second of these (Bakirtzis, Zekos and Moniaros Reference Bakirtzis, Zekos and Moniaros2011), published just before the main period covered here (2015–2025), helped to reinvigorate interest in the region and laid important groundwork for the collaborative spirit that defines many current projects.

Similarly foundational was the TAY (Archaeological Settlements of Türkiye) project, led by Engin Akyürek and his team, which sought to systematically document the archaeological heritage of Turkish Thrace (Akyürek Reference Akyürek, Bakirtzis, Zekos and Moniaros2011 and at http://tayproject.org/enghome.html). Their accessible gazetteer of sites remains a critical resource for scholars and the public. The Tabula Imperii Byzantini series has also shaped our understanding of the region. The volumes by Soustal (Reference Soustal1991) and Külzer (Reference Külzer2008) continue to serve as indispensable references for the historical geography of Thrace, offering systematic documentation of settlements, road networks, and toponyms that transcend political boundaries.

In the realm of material culture, synthetic and comparative studies have provided essential analytical tools. The volume on Late Byzantine glazed pottery by Papanikola-Bakirtzi and Zekos (Reference Papanikola-Bakirtzi and Zekos2007) remains one of the few efforts to trace commercial exchange across Greek Thrace through ceramic assemblages. Their cross-site approach has shown how even modest, previously isolated finds can be placed into meaningful economic and cultural contexts. Such studies underscore the potential of material culture to reveal the interconnectedness of secular and ecclesiastical settlements across a region too often treated in national or disciplinary isolation.

Fortified urban sites

Significant strides have been made toward understanding the architecture, organization, and historical development of fortified settlements in Byzantine Thrace. Diverse in size, layout, and function, these sites collectively demonstrate the region’s strategic importance and the value of its natural and economic resources, which warranted substantial military and infrastructural investment. Variation in fortification styles reflects local conditions and broader imperial concerns. Serving as administrative centres, elite residences, monastic enclaves, or nodes in defence systems, they reveal Thrace’s deep integration into the Byzantine world.

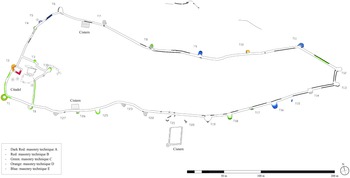

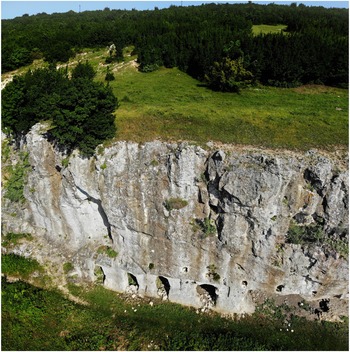

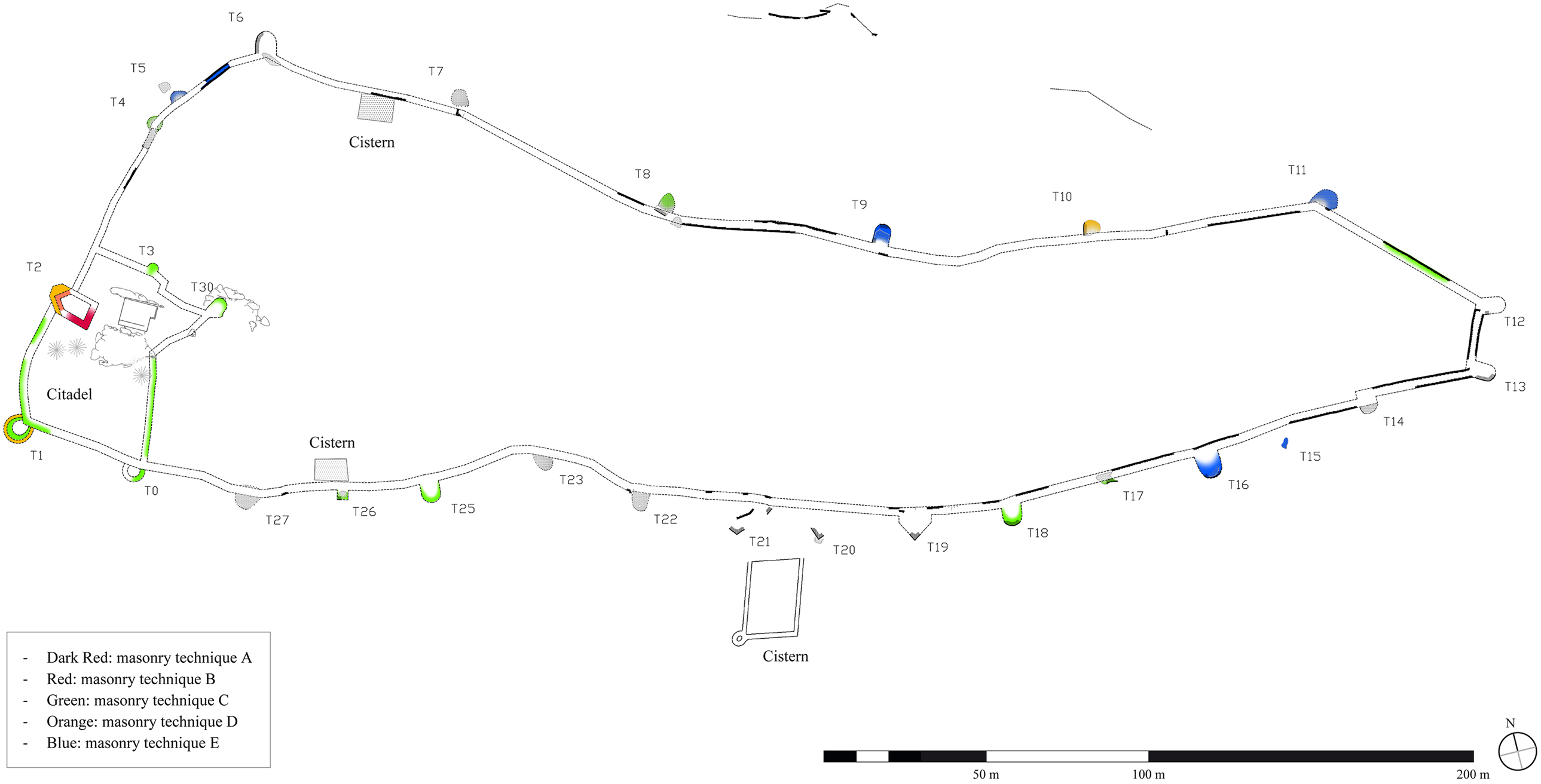

The site of Skopelos (modern Polos Kalesi; Map 4.1), at the foot of the Strandzha Mountains in modern Türkiye, was a large hilltop fortified settlement emerging in the ‘Dark Ages’ (eighth century AD) and active through the fourteenth century (Fig. 4.1). Identified in Byzantine sources as both a fortified settlement and an episcopal seat, Skopelos lay on the shortest route between Pliska and Constantinople, making it a frontier linchpin between Byzantine and Bulgarian spheres of influence. Field campaigns in 2015 and 2017 mapped a fortification system of around four hectares, with 31 towers, an acropolis, and a secondary northern wall (Fildhuth and Ar Reference Fildhuth and Ar2016; Fildhuth Reference Fildhuth2019). Habitation traces, including large structures likely used for public or storage purposes, are densest in the central and northwestern areas. Its water system, two vaulted cisterns inside the walls, and a massive external cistern (24 × 18m; Fig. 4.2) show advanced hydraulic planning and sustainable provisioning.

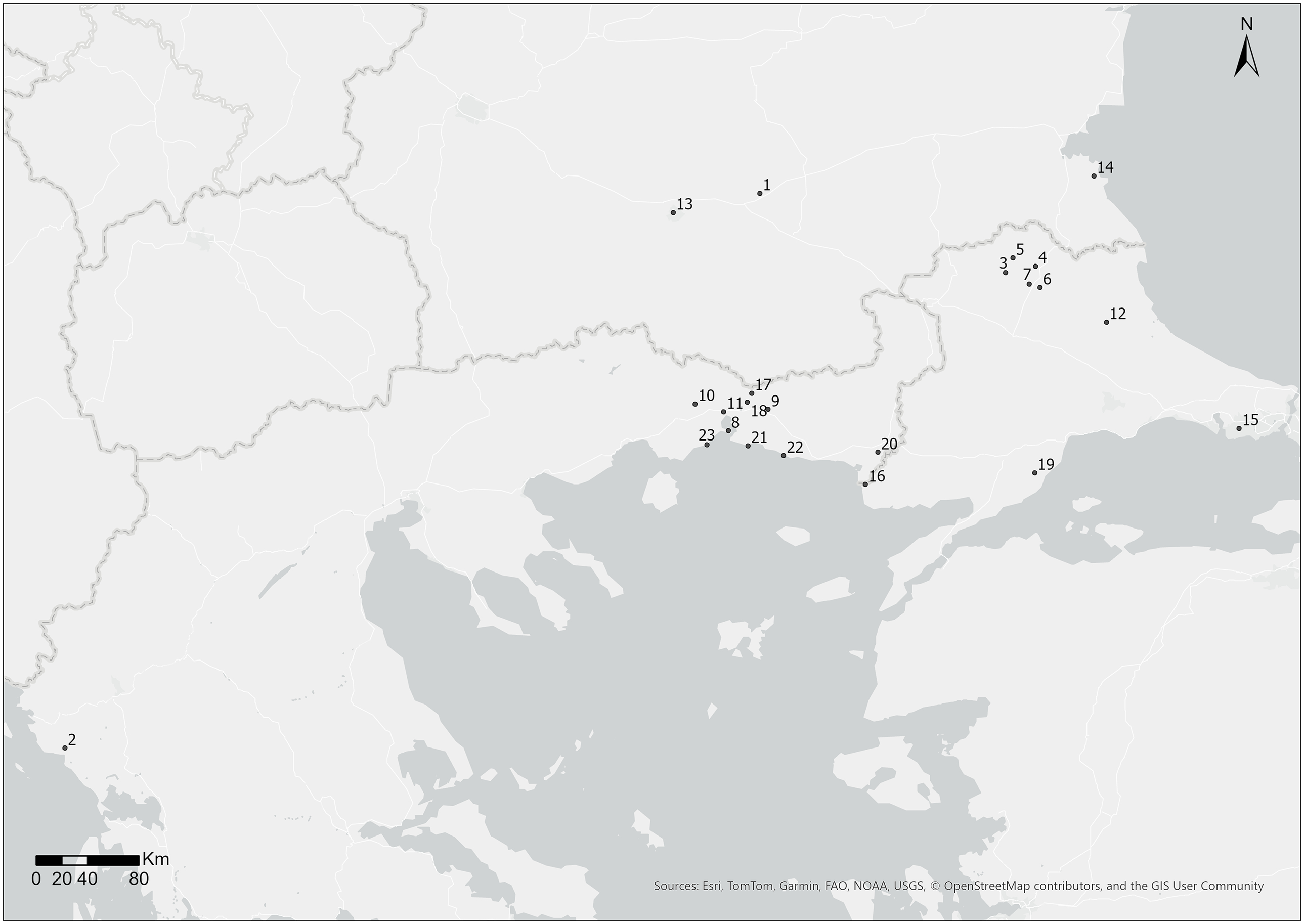

Map 4.1. 1. Karasura; 2. Sveti Ivan Island; 3. Skopelos (modern Polos Kalesi); 4. Kuzulu Kalesi; 5. Erikler Hisar Kalesi; 6. Yündalan (Böyük) Kalesi; 7. Keçikale Kalesi; 8. Poroi; 9. Koumoutzena (modern Komotini); 10. Xantheia (modern Xanthi); 11. Peritheorion; 12. Bizye (Vize); 13. Philippopolis (Plovdiv); 14. Malkoto Kale; 15. Firuzköy; 16. Ainos (modern Enez); 17. Mount Papikion; 18. Linos; 19. Mount Ganos; 20. Bera (modern Feres); 21. Molyvoti; 22. Maroneia; 23. Abdera/Polystylon.

Fig. 4.1. Plan of the Skopelos fortifications, including different masonry techniques, as cited in Fildhuth and Ar Reference Fildhuth and Ar2016: fig. 3. Courtesy of The Skopelos Survey Project.

Fig. 4.2. Skopelos: large cistern seen from the north, as cited in Fildhuth and Ar Reference Fildhuth and Ar2016: fig. 7. Courtesy of The Skopelos Survey Project.

The 2017 campaign documented a network of smaller fortifications, Keçi Kalesi, Yündalan (Böyük) Kalesi, Erikler Hisar, and Kuzulu Kalesi, that illuminate regional defensive organization (Fildhuth Reference Fildhuth2019). Keçi Kalesi and Yündalan Kalesi, visually connected to Skopelos, acted as military outposts safeguarding strategic routes. Keçi Kalesi shows three main phases: Late Antique; eighth-century rebuilding; and twelfth–fourteenth-century modification. Within its interior, where dense vegetation permits, archaeologists have recorded at least seven structures, supporting the interpretation of a garrison site capable of monitoring a wide area.

Yündalan Kalesi shows similar characteristics, while Erikler Hisar incorporates a Byzantine watchtower within an earlier fortification, indicating multi-period reuse. Collectively, these sites point to a coordinated system of military forts designed to maintain visual control over the region and protect its resources and communication routes. In contrast, Kuzulu Kalesi seems to have served a different purpose. With limited defensive visibility, but adjacent to a rock-cut chapel and monastic caves, it may have been part of a fortified monastic complex. This architectural and functional diversity highlights the multifaceted nature of fortified sites in the region, encompassing defence, religious activities, and territorial control.

Around Lake Vistonis in Greece, Makris (Reference Makris2020) reexamines earlier evidence (ID 17786) for a substantial fortified urban settlement, likely identifiable with Byzantine Poroi, between modern Porto Lagos and the lagoon. Features include a sizable church (Fig. 4.3), a circuit wall with towers, and widespread surface material, indicating Poroi’s sustained occupation and its role as a key node in the regional network during the Middle and Late Byzantine periods. Rich finds suggest Poroi was a commercial hub linking land and maritime trade between the Nestos River and Koumoutzena (Komotini). Moreover, its integration into a defensive network alongside nearby Xantheia (modern Xanthi) and Peritheorion highlights Late Byzantine efforts to secure military and commercial passage through the valley north of Lake Vistonis. These findings demonstrate how fortified waterscapes could simultaneously serve as defensive bastions and active nodes of exchange within the empire.

Fig. 4.3. Excavated church, view toward the east, Poroi, Xanthi. Photo © G. Makris/courtesy of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Xanthi.

Ayça Beygo’s dissertation explores Bizye’s (Vize) urban development, fortifications, and ecclesiastical architecture, from its Thracian origins through to the Byzantine period (Beygo Reference Beygo2015). Beygo notes the use of carefully cut ashlar masonry combined with brickwork in the construction of defensive walls and towers. She also highlights the incorporation of polygonal and rectangular towers designed to maximize defensive coverage. Beygo explores how the church of Hagia Sophia, a rare example of the compact domed basilica type, illustrates broader architectural transitions in the Byzantine provinces.

In Bulgaria, Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv) has long attracted scholarly attention due to its enduring political and religious importance, as well as its well-preserved architectural remains.

Excavations (2019–2021) at the episcopal basilica uncovered two richly decorated mosaic floors (700–2000m2). These mosaics, now conserved and integrated into the site’s presentation, belong to two major construction phases: the first (mid-fourth–early fifth century) has geometric patterns and crosses; the second (late fifth–early sixth century) features the ‘Fountain of Life’ with numerous bird species (Kantareva-Decheva, Stanev and Stanchev Reference Kantareva-Decheva, Stanev and Stanchev2020).

Building on this discovery, Topalilov’s analysis of the second mosaic layer reveals the participation of at least four distinct workshops: a metropolitan team likely originating from Constantinople; two provincial groups heavily influenced by the capital’s aesthetic language; and a local workshop employing regional iconographic and stylistic elements (Topalilov Reference Topalilov2023). This combination of artistic inputs underscores Philippopolis’s role as a cultural exchange zone, a city where imperial artistic standards were localized and reinterpreted, producing a visually unified but culturally layered sacred space (Topalilov Reference Topalilov2021). The collaborative mosaic programme reflects both the city’s growing ecclesiastical stature and its integration into wider networks of patronage, craft, and liturgical display.

Philippopolis also remained a vibrant urban centre well into the Middle Byzantine period, as recent excavations in other parts of the city demonstrate (Stanev and Bozhinova Reference Stanev and Bozhinova2020). Investigations have revealed densely built architectural remains from the twelfth to thirteenth centuries, suggesting that the city had reached a period of substantial growth and complexity in the Middle Byzantine period. Several two-story buildings have been identified, with stone and brick construction on the ground floor and mudbrick superstructures above. The widespread use of roof tiles suggests a high level of architectural uniformity and resource availability. Even open spaces between buildings were paved with stone and pottery sherds, indicating a carefully managed and developed urban environment.

The fortified settlement of Karasura, northwest of modern Chirpan, also offers a long-term perspective on site transformation and strategic continuity. Occupied almost continuously from the third to the thirteenth centuries, Karasura’s position along key routes made it both a desirable settlement and a recurrent target for invasion. Excavations in 1987, and again in 2003 and 2004, supplemented by recent publications, revealed a fortified acropolis, necropolis, and an abundant array of material culture (Rauh, Reference Rauh2020; Wendel Reference Wendel2020). These include ceramics, coins, and a wider range of small finds, such as tools for agriculture, textile production, medicine, and writing, alongside weapons and objects of personal adornment. Together, these finds offer important insights into the economic practices, domestic life, and cultural identities of the settlement’s inhabitants.

During Late Antiquity (fourth–sixth centuries), Karasura functioned as a fortified road station, securing a key route and offering protection to the local population. In the eighth century, a new settlement developed to the north of the Kaleto hill, associated archaeologically with Slavic-Bulgarian cultural influences. Following the reestablishment of Byzantine control in the eleventh century, Karasura grew into a substantial settlement with stone-built houses, granaries, and churches, leading scholars to suggest that this might have been the city of Alexiopolis, mentioned by Anna Komnene. Karasura’s eventual destruction and abandonment in the late twelfth century, likely during the Third Crusade (1189–92), mirrors the fate of many Thracian sites affected by regional instability at that time.

Karasura’s diverse material culture, including imports from Central Europe, Asia Minor, and the Islamic world, reflects its integration into long-distance trade networks, its population’s growing socio-economic status, and important episodes of population movement, making it a key site for studying frontier transformation and regional connectivity.

Finally, Malkoto Kale, a smaller fortress near Voden, offers a contrasting yet equally revealing example of a fortified elite residence (Bakardzhiev and Rusev Reference Bakardzhiev and Rusev2019; Reference Bakardzhiev and Rusev2020). Constructed in the late eleventh century and abandoned by the end of the twelfth century, the fortress likely served as the residence of a high-ranking Byzantine official. The small fortress has an irregular quadrangular form, closing a space just over 1,000m2, strengthened by a semi-round bastion in the northwest corner of the fortress and a square tower in the middle of the western wall. The interior of the fortress includes rooms attached to the inner face of the western fortification wall and part of the rooms adjacent to the southern fortress wall. Of great interest is the inner rectangular courtyard 12.5 × 17.5m, framed by these rooms and open from the north. The survival of exposed beam steps in front of the rooms indicates the existence of porticoes leading to the courtyard, while the courtyard’s walking level is plastered with a thick layer of pink mortar. Excavations have also uncovered decorated architectural elements such as decorative bricks and ceramic decorations, as well as a high proportion of luxury ceramics, glassware, personal ornaments, ecclesiastical objects, and a notable group of eight lead seals. These include several related to the prominent Vatatzes family, one belonging to a Byzantine dignitary named Michael Tzitas, of (proto)kouropalates (high-ranking dignitary) and the position of doux (general), and one belonging to the metropolitan bishop of Athens, named Nicetas, further confirming the site’s high-status occupants (Kanev Reference Kanev2022). Malkoto Kale thus functioned not only as a military post but also as a centre of aristocratic control, bridging the worlds of imperial governance and local authority.

Together, these case studies provide a nuanced and multidimensional view of fortified settlements in Byzantine Thrace. They illustrate a spectrum of functions, from fortified cities and economic hubs to frontier defence posts, elite residences, and religious refuge, and highlight the adaptability of local communities to shifting political, military, and environmental conditions. Crucially, they underscore the active role of Thrace and its inhabitants in the Byzantine Empire, not as passive frontier dwellers or a peripheral landscape, but as dynamic agents embedded in and shaping regional and imperial systems of power, identity, and exchange.

Ports and waterscapes

While the archaeology of Thrace is often associated with mountain ranges and valleys, recent research increasingly draws attention to the vital role of waterways – rivers, lakes, and coastal zones – in shaping settlement patterns, economic activities, and religious and military logistics. Far from marginal, aquatic environments were central to the formation and transformation of Byzantine landscapes. Ports, in particular, acted as dynamic interfaces where imperial, regional, and local interests met, enabling mobility, resource exploitation, and cultural exchange.

Significant progress has come through the sustained efforts of Turkish, German, and Polish scholars, often in collaboration with the German Archaeological Institute. These projects investigate ports along the coasts as well as riverine and lacustrine settings, integrating environmental and geoarchaeological approaches to show how sedimentation, shoreline shifts, and river-course changes affected human activity. This shift in focus from purely terrestrial centres to water-based systems invites a more holistic understanding of Byzantine connectivity, spatial organization, and resilience.

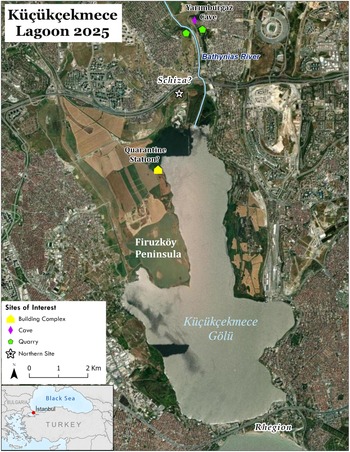

Recent discoveries on the Firuzköy Peninsula and around Lake Küçükçekmece from a German–Polish collaborative project (Cultural Heritage and Archaeological Investigations in East Thrace; https://projekty.ncn.gov.pl/en/?projekt_id=267154), exemplify this approach (Stanisławski and Aydingün Reference Stanisławski and Aydingün2018). Excavations revealed a remarkably complex port settlement, expanding our notion of Byzantine port landscapes, particularly outside major urban centres. At Firuzköy, archaeologists documented a large, intricately planned harbour complex, possibly accommodating foreign ships, such as those of the Rus’ or Scandinavians, that were barred from docking in Constantinople.

Far from a simple anchorage, the site reveals a politically, economically, and spiritually vibrant settlement. Key features include a martyrium possibly linked to the cult of Saint Theodore, a hagiasma (holy spring), a bath complex, a small church, and possibly a baptistery. The identification of a nosokomeion (hospital) points to the presence of a xenodocheion (hostel) for travellers, pilgrims, or merchants. A large, paved forum, connected to the port via a stone road, functioned as a market, evidenced by an assemblage of imported amphorae, coins, glazed ceramics, lead seals, and an amber cross. Together, these finds indicate a settlement designed to regulate and accommodate foreign access to the capital’s hinterland, while also supporting long-distance trade and religious exchange.

Complementing these architectural discoveries are landscape investigations around Lake Küçükçekmece. On the western edge, at least seven additional settlement points were recorded, their distribution suggesting a coordinated network. Underwater sonar surveys further revealed submerged harbour structures, reinforcing the view that the entire basin functioned as an expansive, interconnected port system.

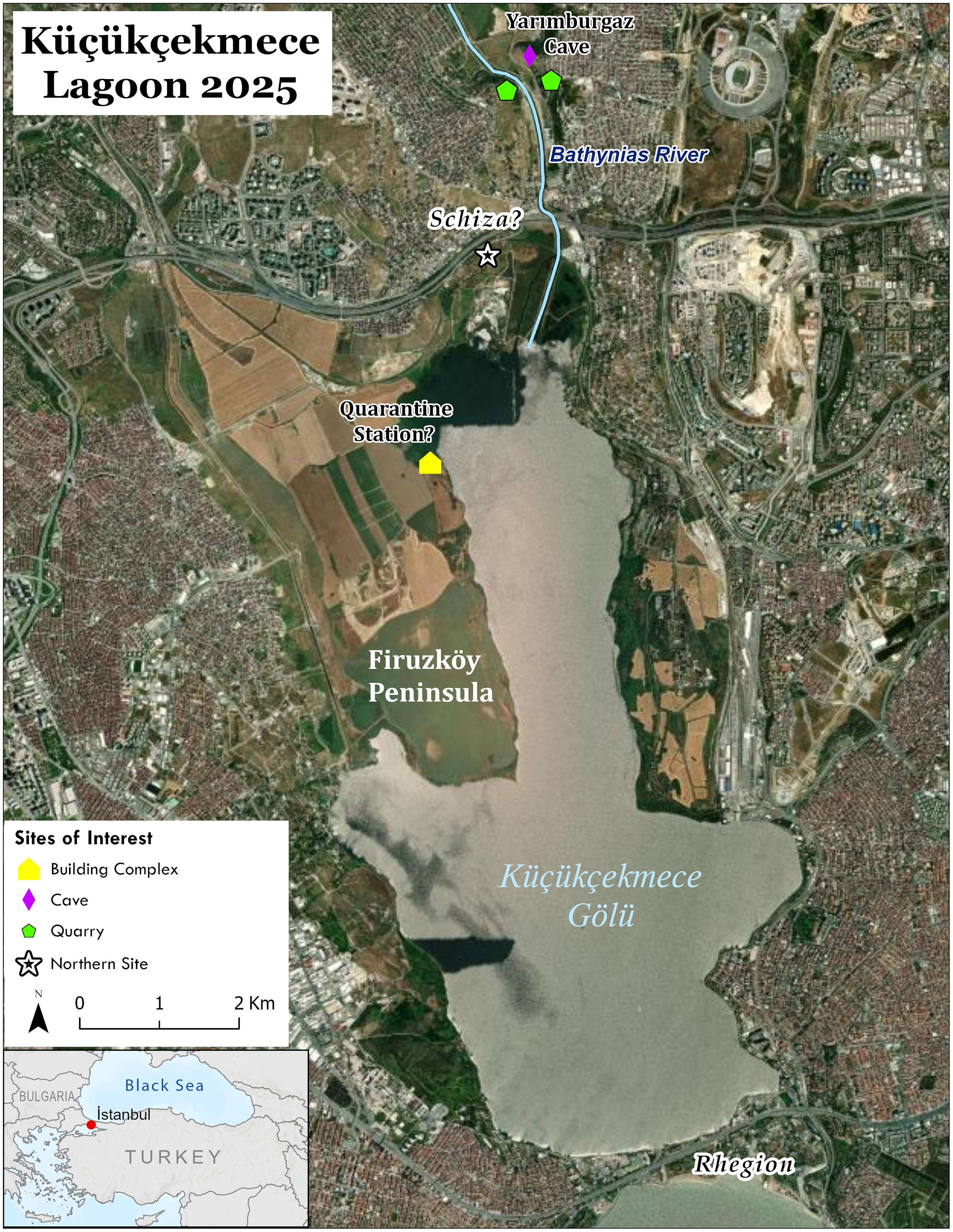

On the northern side, renewed excavations on the Firuzköy Peninsula, conducted since 2022 by Alkiviadis Ginalis and Sengul Aydingün with support from Dumbarton Oaks (https://www.doaks.org/research/byzantine/project-grants/gianlis-2023-2024), have focused on uncovering the maritime significance of the Küçükçekmece Lagoon and the Bathynias River within regional harbour networks (Ginalis Reference Ginalis, Kara and Aydingün2022; Aydingün Reference Aydingün and Ginalis2024; Fig. 4.4). These investigations have revealed extensive Early Byzantine remains, including basilicas, cisterns, sea walls, and port infrastructure, suggesting that the area played a central role in local and long-distance maritime networks. The site may correspond to the ancient Thracian port city of Bathonea, with historical ties to Byzantine settlements such as Schiza or Melantias.

Fig. 4.4. Küçükçekmece Lagoon with relevant sites. Photo © Alkiviadis Ginalis.

Surveys conducted between 2021 and 2022 by Ginalis and Aydingün along the lagoon’s northern shore identified substantial architectural remains near the river estuary, including a massive sea wall enclosing three hectares. Geophysical prospection in 2023 revealed a dense urban layout with streets and large buildings, strongly indicating a significant coastal settlement, likely a town rather than a monastic or military outpost.

Ainos (modern Enez) offers a comparable model. An interdisciplinary research project (2012–2017) investigated the city’s topography and harbour infrastructure from the Roman period through to the Middle Ages (Schmidts et al. Reference Schmidts, Başaran, Bolten, Brückner, Bücherl, Cramer, Dan, Dennert, Erkul, Heinz, Kocak, Pint, Seeliger, Triantafillidis, Wilken and Wunderlich2020). Integrating archaeological, geoarchaeological, and geophysical methods, the project examined how environmental changes, particularly sedimentation from the advancing Evros Delta, reshaped Ainos’ urban configuration and connectivity. With much of the harbour now buried or altered by modern development, the project focused on documenting remaining architectural features and surveying undeveloped coastal zones.

The findings at Ainos highlight two key themes. First, environmental shifts, while often viewed as disruptive, also created new opportunities for urban adaptation. For example, the silting of northern harbour areas led to the continued use of the Taşaltı lagoon, where a large church was constructed nearby, suggesting sustained activity despite landscape transformation. Second, this multi-scalar approach integrates environmental history with material and architectural analysis, situating Ainos as a key Late Antique administrative node, with inland links to Hadrianoupolis (modern Edirne) and grain exports to the Aegean.

Architectural evidence points to intensive building activity in Late Antiquity and the Early Byzantine period, especially in churches and fortifications (Schmidts et al. Reference Schmidts, Başaran, Bolten, Brückner, Bücherl, Cramer, Dan, Dennert, Erkul, Heinz, Kocak, Pint, Seeliger, Triantafillidis, Wilken and Wunderlich2020). Drawing on a combination of surviving ruins, archival photographs, and written accounts, a recent study reconstructs the architectural evolution of many churches photographed and studied by Georgios Lampakis in 1902 (Mamaloukos, Perrakis and Koumantos Reference Mamaloukos, Perrakis and Koumantos2025). The study also illustrates a continuity of church building and stylistic change from Late Antiquity through to the Post-Byzantine period. Moreover, the Late Medieval period saw the expansion of fortifications, including a 130-metre wall with towers stretching from the castle hill to the lagoon, constructed no earlier than the twelfth century and later reinforced by the Genoese Gattilusio family in the fifteenth century. Though not a mole, the wall reflects strategic investment in coastal defence.

Although direct evidence of harbour installations remains limited, geophysics and historical sources indicate active harbour zones north and south of the city, possibly including an outer harbour near Dalyan Gölü. Despite challenges posed by environmental change, Ainos remained an important maritime hub throughout the Medieval period, with salt production, fishing, and shipbuilding supporting a thriving local economy.

Along Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast, Byzantine ports were vital commercial gateways, facilitating the exchange of goods. Mariya Manolova-Voykova’s study (Reference Manolova-Voykova2023) of ceramic imports and local production across 13 coastal settlements in Bulgaria has mapped long-distance trade routes from the Black Sea to inland Thrace, while also identifying patterns of local adaptation and consumption between the eighth and fourteenth centuries.

Taken together, these discoveries underscore the need for focused archaeological attention to riverine, lacustrine, and coastal infrastructures. Water-based systems structured Byzantine life – economically, politically, and spiritually. Ports such as Firuzköy, Bathonea, and Ainos were multifunctional hubs sustaining imperial ambitions and local livelihoods. By combining underwater archaeology with geomorphological survey, they offer a richer, more integrated understanding of how natural and built environments intersect across Thrace.

Monastic landscapes

Thrace is defined by its biogeographic variability and complexity. The vast valleys, mountain chains, and lengthy coastlines along the Mediterranean and the Black Sea explain the wide distribution of monastic sites. To a certain extent, the evident variety of monastic settlements highlights the kinds of locations monks and nuns considered ideal for long-term habitation; sites were often naturally protected and fairly accessible to the laity. The most prominent agglomerations of rural monastic communities were concentrated primarily on Thrace’s holy mountains. The extensive monastic complexes excavated on Mount Papikion and the remains of monasteries, pottery kilns, and the numerous amphora sherds discovered along the Marmara coast at the foothills of Mount Ganos in the 1980s and 1990s testify to the function of these holy mountains as important economic centres (ID 12372, 12373, 13116, 14036, 15066, 15085, 17461, 17721, 17763, 18371, 19080, 19413, 20132). In his forthcoming book, Georgios Makris situates these communities within their broader religious and socio-historical landscape, combining archaeological remains with written sources (Makris forthcoming). He contends that the discourse must move beyond the narrow focus on the katholikon (main church of a monastery) to encompass the ancillary spaces, objects, and nearby rural and urban settlements – elements essential to the rhythms of monastic life. Revisiting the concept of the Byzantine ‘holy mountain’, Makris challenges the Mount Athos-centric model, turning instead to archaeological evidence and topography to reveal how Thracian holy mountains forged commercial and socio-political ties with surrounding villages and towns. This network of exchanges reframes the holy mountain not as an isolated, inaccessible sanctuary, but as a territorially embedded institution deeply enmeshed in the lay world.

Beyond the holy mountains, monasteries were founded near major river and sea routes, such as the Theotokos Kosmosoteira at Bera (now Feres) (ID 17466, 14462) or the monastery of St John Prodromos on the island of Sveti Ivan a few kilometres off Sozopolis on the Black Sea coast (Popkonstantinov and Kostova Reference Popkonstantinov, Kostova and Pazos2020). In many cases, proximity to the empire’s main public roads, including the Via Egnatia and the Via Militaris, ensured longevity and prosperity through access to resources. New and synthetic studies of Thrace’s monastic landscapes contextualize archaeological sites, standing monuments, and written sources to argue that monasteries were connected to important political and socio-economic networks. The Kosmosoteira Monastic Landscape Project (KosMoLand) (Dumbarton Oaks project grant: https://www.doaks.org/research/byzantine/project-grants/kondyli-makris-2023-2024) conducted an architectural survey, along with an extensive field and mapping survey, to reconstruct the landscape around the Kosmosoteira monastery and place it within a broader landscape narrative (Kondyli et al. Reference Kondyliforthcoming). Well-known for its monumental architecture and its imperial patron, Isaakios Komnenos, the extant katholikon seems disconnected from its original setting. By studying the landscape, the architectural remains in the surroundings in tandem with a close reading of the typikon (regulations and rule of a monastery), Kondyli et al. explore how human–environment interactions influenced the monastery’s architecture and rituals. This perspective offers new insights into the monastic landscape, the economic and political activities it sustained, and its role in reshaping the founder’s identity.

The variety of monastic topographies offered rulers, individuals of high political or military status, and local elites across Thrace the opportunity to sponsor and invest in monastic foundations. Recent studies have discussed acts of patronage by members of the Byzantine, Serbian, and Bulgarian imperial courts from the late thirteenth through to the fourteenth centuries. In these approaches, we can observe a tendency to re-examine materials and records from past excavations to understand important moments in a monastery’s life story. For example, a close reading of the monastic complex near the village of Linos on Mount Papikion (ID 12372), combined with an analysis of a fresco in the narthex, has demonstrated the capacity of wealthy women and their families to commission their portraits on the walls of churches and support monastic life during the turbulent fourteenth century (Makris Reference Makris2019a). Similarly, an investigation of the long-excavated remains of a medieval church and circuit wall at the fortified site of Poroi on the southern shore of Lake Vistonis coupled with a study of Athonite archives revealed that the emperor, the Vatopedi monastery, and, later, Serbian lords increasingly invested unprecedented amounts of money in the natural resources and towns of southwest Thrace, as these provided safe access to Constantinople, the interior of the Balkans, and the Aegean Sea (Makris Reference Makris2020).

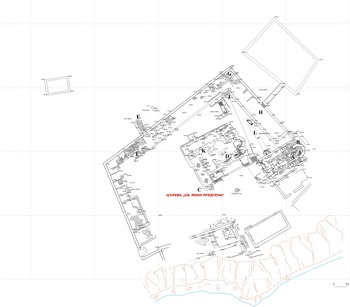

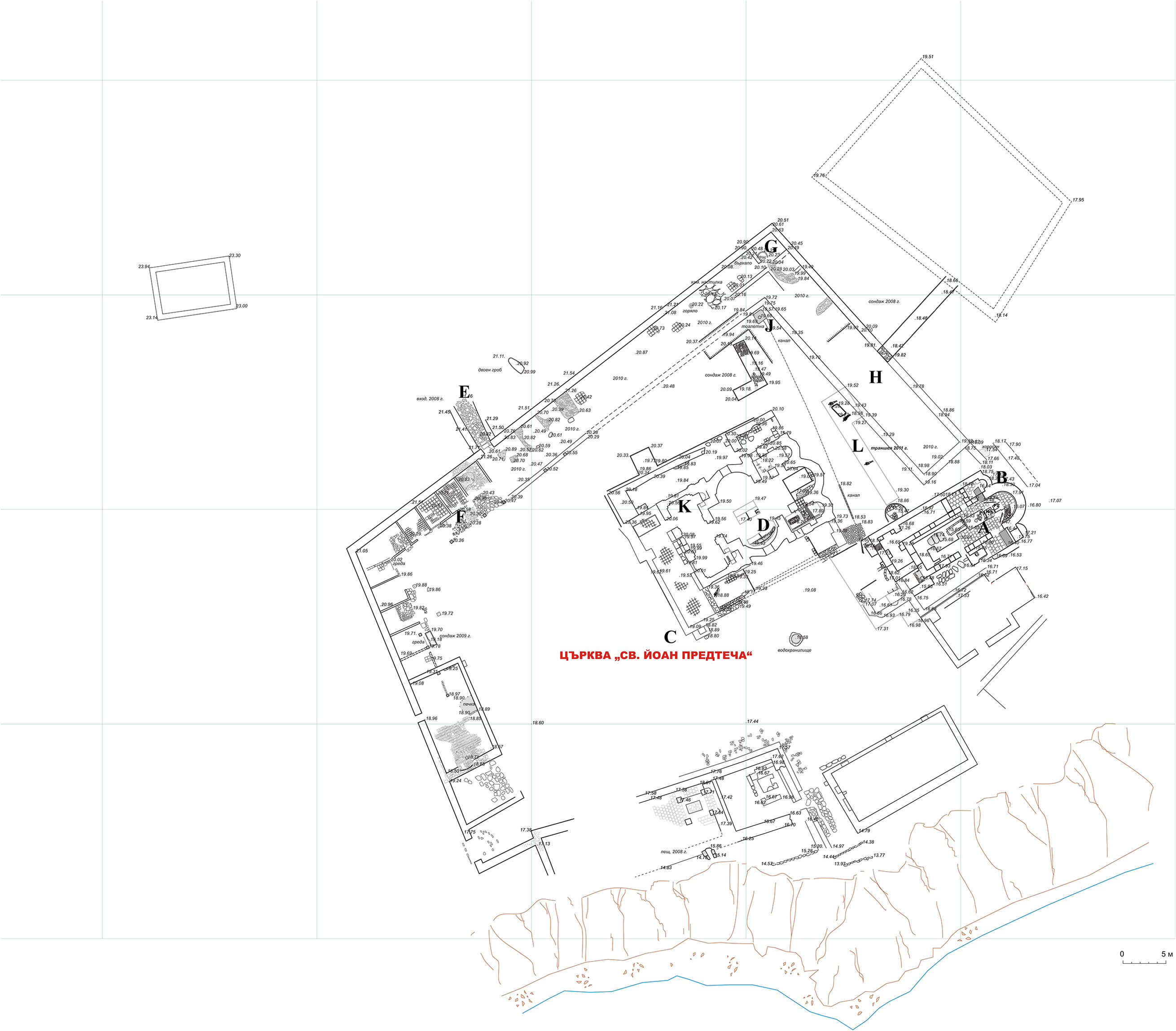

In the Late Byzantine period, the remains of monasteries can also be regarded as material signatures of the close relations between the emperor and religious institutions on the borders of the empire. A prime example is the monastery of St John Prodromos on the island of Sveti Ivan, about a kilometre northwest of Sozopol (medieval Sozopolis). Ongoing excavations have revealed the remains of two three-aisled basilicas built on top of one another sometime between the fourth and the late sixth century (Popkonstantinov, Drazheva and Kostova Reference Popkonstantinov, Drazheva and Kostova2015; Popkonstantinov and Kostova Reference Popkonstantinov, Kostova and Pazos2020; Fig. 4.5). Another triconch church in the vicinity was constructed in the thirteenth or early fourteenth century to serve as the katholikon of the monastery of St John Prodromos (Fig. 4.5); written sources indicate that the church was restored by the officer Michael Glabas Tarchaneiotes in the late thirteenth century (Makris Reference Makris, Mattiello and Rossi2019b).

Fig. 4.5. Plan of the monastery of St John the Forerunner with the excavated structures after 2008, as cited in Popkonstantinov, Drazheva and Kostova Reference Popkonstantinov, Drazheva and Kostova2015 (reproduced with permission).

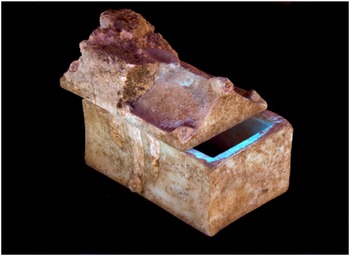

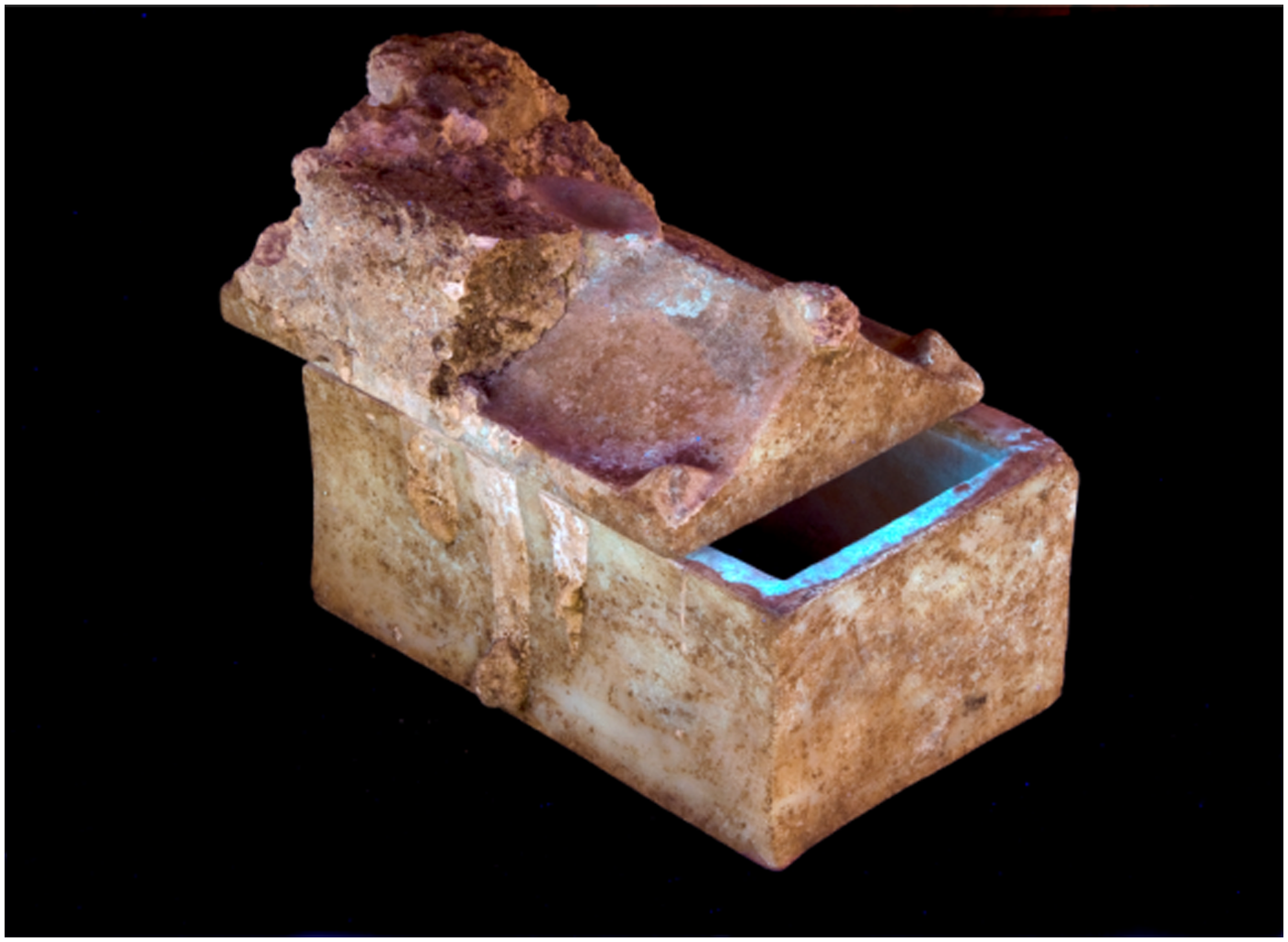

Excavations have also revealed a substantial part of the surrounding wall, including a gate, the monastic cells built against the circuit wall, a refectory, a kitchen, a baking oven, a monumental cistern, and a luxurious building of uncertain function. The remains of the monastery’s scriptorium are of the Ottoman period, but the structure’s earlier foundations are also visible (Popkonstantinov and Kostova Reference Popkonstantinov, Kostova and Pazos2020). The excavation on the island made the news when archaeologists discovered two reliquaries inside the sanctuary of the Early Byzantine basilica (sixth century; Fig. 4.6). An inscription on the smaller reliquary made of stone records the name of St John Prodromos, a certain Thomas, and the date of 24 June. The marble reliquary contained pieces of human bone, for which an anthropological and DNA analysis indicated that the individual was a male, probably from the Near East, who likely lived in the first century AD. Due to various obstacles related to bone preservation and the rights of ownership, the potential identification of the individual as St John the Baptist should be treated with caution (Popkonstantinov and Kostova Reference Popkonstantinov, Kostova and Pazos2020).

Fig. 4.6. The marble reliquary found in the old church of the monastery, as cited in Popkonstantinov and Kostova Reference Popkonstantinov, Kostova and Pazos2020: fig. 13 (reproduced with permission).

The rural landscape

Despite growing interest in Byzantine Thrace, the region’s rural landscape remains significantly underexplored, with archaeological attention historically focused on urban centres and fortified sites. However, recent scholarship has begun to shift this urban-centric lens, revealing an active, complex, and interconnected countryside where various social groups, economic activities, and settlement types coexisted and interacted. The conventional dichotomy between urban and rural breaks down here, as the evidence points to fluid networks of movement, exchange, and mutual influence between cities, villages, estates, monastic sites, and isolated rock-cut complexes.

A notable example of this reorientation is the Molyvoti Thrace Archaeological Project (MTAP; https://mtap.scholar.princeton.edu/overview), which conducted an intensive field survey of the countryside surrounding the ancient coastal city near the Molyvoti Peninsula. Unlike many prior investigations focused on monumental or fortified urbanism, MTAP centred its efforts on unfortified rural settlements (ID 5057, 5452, 6182). The survey’s Byzantine ceramic assemblages reveal that even ostensibly rural areas were deeply embedded in broader socio-economic systems (Makris Reference Makris, Arrington, Terzopoulou, Tasaklaki and Tartaron2025). These settlements maintained close ties to nearby urban centres such as Maroneia, Poroi, Mosynopolis, and Koumoutzena, as well as to coastal trade routes. The material culture, especially the prevalence of fine wares, suggests prosperous rural residences or estate-based communities situated near arable land. While their precise layout and function remain somewhat elusive, these sites participated in regional networks of production, distribution, and consumption.

Complementing this view of a vibrant rural landscape is the emerging field of rupestrian (rock-cut) architecture in Thrace, which offers new insights into how communities shaped and adapted to their environments (Günay Reference Günay2021; Reference Günay2024; Reference Günay2025; Mısırlı Reference Mısırlı2023). Günay’s recent archaeological and architectural survey of Byzantine rupestrian landscapes in the Strandzha Mountains is reshaping how we understand these spaces, their architectural choices, and their socio-environmental contexts (Günay Reference Günay2025; Fig. 4.7). First, by documenting a wide range of caves and rock-cut structures in Thrace, Günay reframes rupestrian architecture not as a regional phenomenon, known primarily from Cappadocia and Phrygia, but as a broader practice within the Byzantine Empire, shaped by distinct geological and environmental conditions. Second, the complexity of these structures suggests that their creation was not driven solely by necessity; rather, they reflect deliberate choices that blended built and carved elements, often requiring specialized knowledge and technical skill. Importantly, this focus also shifts our attention away from large urban centres and toward a better understanding of how the rural hinterland was occupied, organized, and experienced. Günay’s work reveals a densely inhabited and interconnected landscape in which rupestrian sites included chapels, monastic communities, cemeteries, residences, and spaces for economic production, especially wine-making facilities. By documenting also their proximity and integration into networks of roads, rivers, ports, and quarries, Günay reframes these features not as marginal or exceptional, but as integral to the regional settlement pattern.

Fig. 4.7. Monastic settlement in Asmakayalar valley near Bizye (Vize), hermitage north of the monastic core, as cited in Günay Reference Günay2021: fig. 1 (reproduced with permission).

Together, the findings from MTAP and Günay’s rupestrian studies enrich our understanding of Thrace as a dynamic and densely inhabited region, shaped by imperial policies, local agency, environmental adaptation, and shared infrastructures. As such, the countryside emerges not as a backdrop to urban life, but as an essential and active part of Byzantine Thrace.

Macro and micro-histories of Byzantine Thrace

Over the past decade, research in Thrace has significantly advanced our understanding of both long-term developments and moments of profound transformation in the region during the Byzantine period. This growing body of work reveals how large-scale political events, such as the Crusades and territorial shifts, had wide-reaching effects, yet were experienced differently across sites. Thrace emerges as a region of complex, often parallel trajectories, shaped by local responses to empire-wide changes.

In the transitional centuries (seventh–ninth centuries), responses to instability included the construction of new fortified settlements such as Skopelos and Abdera, or the reoccupation and transformation of older, Late Antique centres. At Karasura, for example, the abandonment of the original settlement and the rise of a new site with Bulgaro-Slavic material culture reflect broader patterns of population movement and changing political control along the empire’s frontiers. Meanwhile, long-established centres like Abdera/Polystylon remained vital ecclesiastical and administrative hubs, with archaeological evidence pointing to robust health, a diverse diet, and sustained activity into the tenth century (Agelarakis and Agelarakis Reference Agelarakis and Agelarakis2015).

The Middle Byzantine period marks a time of recovery and prosperity. Thrace benefited from its strategic location, abundant natural resources, and connectivity via land and sea routes. Once Byzantine control was firmly reasserted in the eleventh century, efforts were made to enhance regional security through fortifications and surveillance infrastructure. The reconfiguration of settlement and trade networks in the wake of losses in Asia Minor may also be reflected in imported goods from Anatolia and the Islamic world found at sites like Karasura. The rise of elite estates and monasteries, such as those at Malkoto Kale and Kosmosoteira, underscores the growing role of aristocrats and imperial figures in shaping the landscape and economy of Thrace during this time.

The Late Byzantine period presents a more turbulent picture. The devastation brought by the Third Crusade led to the destruction or abandonment of several fortified settlements. Nonetheless, there were efforts at restoration, such as those at the monastery of St. John Prodromos on Sveti Ivan and by Michael Glabas Tarchaniotes in the thirteenth century. Monastic centres like Papikion flourished, while others show signs of severe trauma and social breakdown. For example, at Abdera, examination of Late Byzantine skeletons indicates widespread injury and stress, reflecting a population under extreme duress despite continued habitation and maritime activity (Agelarakis and Agelarakis Reference Agelarakis and Agelarakis2015).

The cave at Maroneia provides a microcosmic view of regional patterns (ID 640, 641, 2315, 5772; Panti Reference Panti2023). Initially used for storage in the Early Byzantine period, it later became a refuge during Middle Byzantine instability, before being abandoned in the fourteenth century when the site of Maroneia was resettled. Its material culture, including imported pottery, points to strong trade connections with Asia Minor and the Eastern Mediterranean, underscoring Thrace’s role as a cultural and economic crossroads despite geographical barriers such as the Rhodope Mountains.

Conclusions

The varied and systematic archaeological work undertaken across all three sides of Byzantine Thrace – Greek, Bulgarian, and Turkish – demonstrates both the depth of regional histories and the value of viewing them through an integrated lens. This review underscores how much we gain by moving beyond site-specific narratives to consider broader questions: how were these settlements interlinked? What roles did they play in shaping and responding to imperial, environmental, and social changes? While excavation reports have yielded rich spatial data, such as architectural plans and detailed find catalogues, they often leave larger regional dynamics underexplored. By reassessing these findings collectively, new patterns emerge about Thrace’s function, not merely as a strategic corridor, but as a vibrant frontier shaped by overlapping political, economic, religious, and environmental forces.

One of the most striking themes that emerges is resilience. Despite recurring conflict, shifting borders, and repeated attempts to extract or control its resources, Thrace shows a remarkable continuity of settlement across centuries. The survival and even flourishing of small and large sites suggest that local populations adapted effectively to disruption, maintaining connections with imperial centres and regional networks alike. In some periods, Thrace functioned as a heartland closely integrated with Constantinople; in others, it was reshaped as a borderland, but one that remained active, attractive to elites, and globally connected through trade, pilgrimage, and political alliances. Studies of ports, fortifications, and religious landscapes further reveal how local agency, strategic geography, and environmental opportunity were harnessed to sustain life and identity in changing times.

This diversity of responses also speaks to the region’s varied geomorphology, which is far too often flattened in traditional narratives. Thrace was not simply a landlocked frontier bounded by mountain ranges, but a dynamic environmental mosaic of rivers, lakes, lagoons, and coastlines – vital arteries for mobility, commerce, and communication. Recent research into fluvial and lacustrine port sites shows how these waterscapes functioned as connective tissue for settlements, religious centres, and economic exchange, often rivalling the importance of major sea ports. Their fragile yet productive ecosystems offered fertile lands, transport routes, and strategic advantages, underscoring the need for more interdisciplinary approaches that unite environmental history with archaeology and historical geography.

Indeed, one of the most promising developments in recent scholarship is the move toward interdisciplinary methodologies, especially in the study of coastal and riverine environments. Research that integrates archaeological, environmental, architectural, and geospatial data is yielding far more holistic understandings of human–environment interaction. In the case of port landscapes, such approaches illuminate not only the material infrastructure of trade and defence, but also the lived experience of communities negotiating space, water, and empire. These models set a valuable precedent for future research across other underexplored regions of the Byzantine world.

At the same time, this review highlights a pressing challenge. While the archaeological record of Byzantine Thrace is growing rapidly, much of this scholarship remains siloed within national traditions, linguistic boundaries, and disparate publication venues. Despite the region’s strategic significance, Thrace continues to be underrepresented in broader Byzantine studies, its many insights often obscured by fragmented research infrastructures. Greater scholarly integration is essential to fully grasp the historical significance of this borderland, not only as a zone of military and political transformation, but as a space of cultural creativity, spiritual life, and environmental adaptation.

The BRIA project (https://briaproject.com) responds directly to these challenges. As a cross-border initiative, BRIA brings together scholars and students from Bulgaria, Greece, and Türkiye, offering a model for collaborative, interdisciplinary, and sustainable research. Through joint fieldwork, workshops, and partnerships with local institutions, BRIA fosters knowledge-sharing and mentorship for students and early career scholars across national and disciplinary divides. Its work highlights the rich but overlooked cultural heritage of Byzantine Thrace, from monasteries and fortresses to settlements, ports, and sacred landscapes, and aims to place the region within broader historical narratives of the Byzantine and Post-Byzantine world. By promoting a shared academic space, BRIA not only amplifies the visibility of Thrace’s heritage but also sets a model for how international scholarship can be reimagined: rooted in cooperation, accessibility, and a deep commitment to future generations of scholars.

Taken together, the studies and research initiatives reviewed here show that Byzantine Thrace is no longer a marginal or peripheral space, but a region of complexity, resilience, and innovation. Yet to truly realize its potential in Byzantine studies, the field must continue to embrace integrative, comparative, and interdisciplinary research strategies, linking local discoveries to regional and imperial narratives.