George Alfred Walker’s campaign to relocate burial from London’s crowded (intramural) city churchyards to new out-of-town (extramural) cemeteries has been identified by scholars of death, burial and cemeteries as crucial to the reform of burial practices in nineteenth-century Britain. Walker (1807–84) was a London-based surgeon-apothecary (or general practitioner) who argued prominently against burial in towns primarily on the grounds of public health.Footnote 1 He conveyed his argument across a series of sensationalist writings and activities, successfully grabbing the attention of the legislature, medical practitioners and public at different times throughout his campaigning career. However, Walker’s work has remained peripheral to, and burial reform ‘always sat awkwardly’ with, the historiography of public health and its focus on sanitary reform and sewer building in the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 2 At the same time, Walker’s significant and diverse campaigning activities that utilised his medical knowledge for his political ends have not received a full account, despite long-standing calls for such work.Footnote 3 This article provides the first comprehensive account of Walker’s diverse campaigning activities, linking his work to major developments in public health and science communication. We thereby provide new avenues for understanding the development of public health and cemetery management in the nineteenth century. Most significantly we show (i) that burial reform provided medical practitioners with reasons to support the otherwise debateable sanitary ideal of Poor Law Commission Secretary and key sanitary reformer Edwin Chadwick as it potentially offered work for underemployed surgeon-apothecaries, and (ii) that sanitary reform politics was central to permanently changing the face of British death and burial management, reshaping the place of the dead in the landscape in the nineteenth century and beyond.

Walker’s prominent place in the history of British cemetery reform stems from his 1839 book Gatherings from Grave Yards: Particularly Those of London which gave a historical, moral and medico-scientific account of the insanitary nature of graveyards in a ‘radical’ descriptive style.Footnote 4 Julie Rugg has shown that though the insanitary nature of intramural graveyards was well known, Walker presented ‘an almost Gothic relish of the worst conditions’, which ‘transformed the language then used to describe graveyards’.Footnote 5 For instance, concern with public health and Walker’s vivid descriptions were employed by private extramural burial grounds as an advertising strategy from the 1840s.Footnote 6 Moreover, his presentation of the burial issue, which included ‘rudimentary statistics’ on poor districts, and ‘his unbending insistence that national legislators solve the problem’, was a key catalyst for reform. Mary Elizabeth Hotz argues that Walker led the way in determining the debate on burial and subsequent reform, as his work shaped how Edwin Chadwick ‘identified and represented the problem of corpses and graveyards’, evidenced in Chadwick’s report on intramural burial practices, A Supplementary Report on the Results of a Special Inquiry into the Practice of Interment in Towns (1843, henceforth Interment Report).Footnote 7 This document is generally viewed as the turning point for burial reform, eventually ushering in a comprehensive programme of reform through a series of legislative acts throughout the 1850s, referred to collectively as ‘the Burial Acts’, which initially prioritised metropolitan reform but soon found wider national deployment. Walker’s role in the history of burial reform, then, is primarily one of initiator, summarising and popularising the scientific orthodoxy that miasma emanating from overcrowded burial grounds was a public health risk in terms that captured the public’s imagination and shaped Chadwick’s report. At the same time, in the ample histories of the sanitary reform movement Walker is largely absent, and burial reform in general has remained peripheral to the main narrative of sanitary reform because, as Julie Rugg summarises, it was tied up ‘with religious politics and the authority and, more pertinently, economics of the Established Church’.Footnote 8 Burial fees were an important source of income for parishes.Footnote 9 Reforming the system therefore required a separate financial solution from the main thrust of sanitary reform which was eventually provided by the Burial Acts. The distinct legislation required goes some way to explaining why burial reform has often been set apart from the main thrust of nineteenth-century public health reform. Though often highlighted as part of analyses of public health development in the period, Rugg’s assessment is apt: that burial reform has served as ‘simply one more item in a catalogue of disamenities’ or been discussed primarily as an adjunct aspect of Edwin Chadwick’s career.Footnote 10

Here, we examine how Walker’s whole campaigning career – – from his 1839 book to his final set of pamphlets published in 1852 – – intersected with the broader sanitary reform movement. Drawing on the history of medicine and scientific publishing, we substantially revise key aspects of Walker’s work and thereby his role in British cemetery reform. Most significantly, we argue that Walker’s Gatherings from Grave Yards was intended to directly address Chadwick and the Poor Law Commission following the 1838 publication of the Fourth Annual Report of the Poor Law Commissioners of England and Wales (henceforth Fourth Annual Report) aimed at including burial reform as part of their remit by presenting it as a nuisance to public health like poor sewerage.

The most important aspect of Walker’s work in this regard was his unorthodox representation of fever causation (contra historians of burial reform): he attributed fever not to a range of potential factors that included miasma, but primarily to miasma caused by putrefying matter. Walker, in particular, drew on the work of Thomas Southwood Smith – the favourite medical theorist of Chadwick and the Poor Law Commission – despite Southwood Smith’s views being widely perceived as heterodox by his contemporaries.Footnote 11 This difference over disease causation may seem small, but as Christopher Hamlin has argued, it was central to the development of public health policy that avoided social policy solutions that might help the poor directly, in favour of sanitary infrastructure that would remove barriers for the poor for their indirect benefit – a more agreeable solution to middle-class sensibilities.Footnote 12 By demonstrating the clear links between Walker’s and Southwood Smith’s fever theory for the Commission, a broader context for cemetery reform is established that provides a clear role for burial reform in the sanitary movement and presents Walker’s scientific work as contingent on historical factors. Thus, Walker did not simply present ‘the scientific facts’, as has typically been suggested by historians of burial reform.Footnote 13 Rather, he presented a particular argument for burial reform that employed heterodox medical theory to pique middle-class interest and fear, and garner support.

Walker’s argument that burial in city churchyards should be considered as a public health issue had its roots in what historians of public health have identified as a developing focus on the control of miasmatic environments to promote health for public benefit by mid-nineteenth-century legislators. In this equation, theoretical correctness on fever causation ultimately played a secondary role to political expediency and the eradication of notorious ‘fever nests’ because detailed medical knowledge was often deemed unnecessary to the debates at hand.Footnote 14 Chadwick being, in Anne Hardy’s terms, ‘notoriously mistrustful of the medical profession’ accounts for some of this attitude.Footnote 15 But legislators and key actors like the judiciary also felt able to act on their understanding of miasma without always referring to medical expertise. James G. Hanley has made this argument most forcefully in his exploration of how the ‘salubrity, liability, and sanctity’ of property was redefined between 1815 and 1872 as legal concepts like the environmentally based health hazard were developed. Focusing on decision-making in various locales, Hanley shows that lay understandings of miasmatism did ‘political and legal work’ in the redefinition of the bounds of liability by private property owners for sewerage works that benefitted the public, with miasmatism ultimately becoming ‘a doctrine of liability, not of disease transmission’ in British public health.Footnote 16 By making the danger of burial in London concur with Southwood Smith’s fever theory, Walker presented city graveyards as a nuisance consistent with other acknowledged issues like poor sewerage, in turn making intramural interment subject to the same kind of political scrutiny by legislators and the public.

To facilitate this, Walker used a range of communication strategies, old and new, that reflected the shifting nature of political campaigning as it related to science in the nineteenth century. It is through these communication strategies that the strongest links that burial reform had to the broader public health movement can be sketched out.Footnote 17 This article therefore takes Walker’s campaign as an exemplar of how burial reform was intertwined with the broader sanitary reform movement – with its science, political concerns and communication methods. Of course, Walker was not the only actor who promoted the cause of burial reform. However, he was highly prominent in this cause and, as a medical practitioner, helps to bridge the historiographical divide that has kept burial reform and sanitary reform separate in historical accounts of nineteenth-century public health. As a result, our analysis of the reception of Walker’s campaigning focuses primarily on medical literature, particularly journals such as The Lancet which campaigned on behalf of surgeon-apothecaries and the Provincial Medical & Surgical Journal (now British Medical Journal) focused on practitioners in the provinces. This enables direct comparison across the issues of sanitation and burial as Walker’s campaign developed. The remainder of the introduction outlines how the three distinct stages of Walker’s campaigning career (which correspond to the three sections of this article) illuminate the links between burial reform, the sanitary movement and science communication in different ways.

Walker began his campaign with his only full-length book on the subject of burial reform, the aforementioned Gatherings from Grave Yards. As we show in the first section, the work paralleled features of the Fourth Annual Report to aid burial reform’s amenability to the Poor Law Commission. Crucially, this included the report’s statistical and narrative elements, its use of the local to illuminate the national, and its moral imperative. These features were closely tied to contemporary writing on statistics. Historians of statistics have argued that nineteenth-century statistical science had a public character that addressed a broad constituency of citizens.Footnote 18 As Maeve E. Adams has argued, this included mixing ‘numerical and narrative genres’ in accounts of the state to help frame problems ‘in terms of parts and wholes’.Footnote 19 This meant that accounts of horrendous local conditions, such as Walker provided in his famous virtual tour of London graveyards, were intelligible as microcosms of the macro – Walker presented this as a national problem. Moreover, the statistics Walker provided may have been rudimentary but were in keeping with the Fourth Annual Report and the Commissioner’s concerns.Footnote 20 They also shared the ‘tone of exhortation’ that Edward Higgs has identified in statistical accounts produced by the General Registry Office (GRO), founded in 1837 and which became a key body providing supporting evidence for public health measures.Footnote 21 Simon Szreter has argued that the presentation of data on mortality by the GRO was intended ‘to shame’ local authorities into action – an apt description of Walker’s work also.Footnote 22

Alongside his book, Walker composed petitions, pamphlets and letters to target key stakeholders – clergy, politicians, reform’s opponents and medical practitioners. The second section shows that Walker married arguments for burial reform that had appealed to particular audiences to publication formats in order to present his case in ways best suited to that audience. Common across this strategy was Walker’s use of cheap publication formats. The production of cheap periodicals on scientific subjects had been an established part of political campaigning since the founding of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge in 1826; Barry Barnes and Steven Shapin argue that the production of periodicals like the Penny Magazine by the Society had been in part an attempt to shift working-class politics away from revolution by providing them with scientific knowledge that transcended politics.Footnote 23 Walker’s use of pamphlets in particular thus fits well with work connecting print format, science and politics to develop and exploit the public’s understanding of science in this period.Footnote 24

After a promising start, Walker’s campaign faltered in the mid-1840s, prompting a change in strategy. The third section shows that he continued producing pamphlets and letters, but also began to copy the activities of reforming societies like the Health of Towns Association by founding his own reforming society, giving public lectures and planting sympathetic articles in friendly reforming newspapers. What was different about this phase of activity was Walker’s explicit aim to cause controversy. In part this was facilitated by changing standards of print culture, as some newspapers took on roles as tribunes of the people, purposefully stoking controversy for political effect.Footnote 25 But crucially, Walker’s role also changed as his personal presence in public became more important. Scientific showmanship was an important avenue through which epistemic and political ends could be articulated in the nineteenth century.Footnote 26 Beyond simply discussing dreadful conditions in city cemeteries in public lectures, Walker’s strategy blended the disgusting and instructive in ways akin to public performances of galvanism (animal electricity) on a human corpse, or public anatomical exhibitions.Footnote 27 This is typified by Walker’s protracted engagement with an infamously overstuffed burial vault at Enon Chapel, a Methodist chapel founded in a pre-existing structure in 1822, with its basement restyled as a burial vault, and which had accepted as many as 10,000–12,000 (paid) interments by the time of its closure in 1839.Footnote 28 Walker’s protracted criticism of this site culminated in his stunning personal acquisition, public exhibition and clearance of the vault in 1846–7. Our reconstruction of this spectacle (and the controversy Walker stoked over the Spa-Fields Burying Ground) shows how this could be an effective strategy for public health campaigners to unite the concerns of national legislators with local judiciary and the public.

The sheer range of campaigning activities Walker was involved in challenges the current narrative around burial reform in Britain: his continued, active engagement with various stakeholders to promote his cause shows that its success was not guaranteed once Chadwick’s Interment Report was published. Reconstructing Walker’s varied campaigning career chronologically demonstrates his proactive and responsive approach to pushing burial reform through parliament. Moreover, his close association with the science, political aims and strategies of sanitary reform throughout his career underlines the close association that sanitary reform had with burial reform. From Walker’s Gatherings from Grave Yards to the passage of the Burial Acts in 1852/53, the causes of sanitation and cemetery management were mutually supportive.

Appealing to the Poor Law Commission

Published in 1839, Gatherings from Grave Yards directly engaged with the most recent findings of the Poor Law Commission, published in their 1838 Fourth Annual Report. Walker was concerned specifically with the supplementary reports on the physical causes of fever in London, produced for the Commission by three physicians – one report by Neil Arnott and James Phillips Kay, and two reports by Thomas Southwood Smith. In Gatherings from Grave Yards, Walker registered his ‘surprise’ that the commissioners had not given more attention to graveyards in their reports. He noted that ‘the only direct medical testimony’ was a short letter sent to the Commission in Arnott and Kay’s combined report, and went on to criticise Southwood Smith’s two reports, which he viewed as competent but incomplete without consideration of graveyards.Footnote 29 By providing his own reports on metropolitan graveyards, Walker thus supplemented and expanded the work of the Poor Law Commission.

Though traditionally associated with the development of Chadwick’s ‘sanitary idea’ and the development of sewerage systems, Christopher Hamlin argues that these three reports ‘were to make the case for investing poor law funds in nuisance removal. This would lower disease, and ultimately lower poor law costs’.Footnote 30 Arnott and Kay’s report did recommend ‘A perfect system of sufficiently sloping drains or sewers’ and water for households, but this was not yet the ‘comprehensive sanitation’ system that the ‘sanitary idea’ would become.Footnote 31 Also recommended by Arnott and Kay was a service of scavengers to remove street rubbish, widened streets to improve ventilation, prohibition of overcrowded lodging houses, and the removal of noxious trades such as ‘cattle-markets, slaughter-houses, … burying-grounds, &c.’, as far as possible from cities.Footnote 32 The changes envisaged at this point were small; ‘only sanction for the small charges … in removing nuisances’. Doing so would ensure that local authorities would not use poor law money to tackle destitution, instead focusing on ‘removable filth’.Footnote 33 Exactly what removable filth was to be targeted was still up for debate.

In order to present intramural burial as an appropriate nuisance to be targeted, Walker reflected the scientific and social concerns of the commissioners, primarily the ‘extreme views’ of Southwood Smith on fever. As Margaret Pelling has explained, in the early nineteenth century most medical practitioners held that the character of fevers was ‘mixed’ and existed on a spectrum of causation. At one end of the spectrum, fevers could arise from the effects of the atmosphere and individual constitution (such as intermittent fevers). At the other end of the spectrum they had ‘a constant character’ independent of atmospheric or individual variation (like smallpox). By contrast, in his 1830 A Treatise on Fever Southwood Smith had put forth a ‘unitary’ view, that there was one kind of varying fever – diverse at the clinical level, but not in its specific cause.Footnote 34 This cause was atmospheric fever ‘poison’ formed by putrefying animal and vegetable matter, which caused inflammation in the solids of the body. In different climates and at different concentrations, it caused different kinds of fever. Typhoid and plague were both caused by high concentrations of exposure to ‘animal malaria’ – that is, ‘putrefying animal matter’ – but plague was more common in the ‘sultry heats of July and August’ in Egypt, typhoid in the colder climes of northern Europe.Footnote 35 For Southwood Smith, this meant that fevers could not be caused by debility in the individual’s constitution; a dissenting view to that held by most of his contemporaries, who regarded the deleterious effects of poverty as a possible cause of fever.Footnote 36

Southwood Smith’s fever theory, by contrast, made poverty a factor incidental to disease, not a potential cause. The locus of disease therefore became places from which the fever poison emanated, and the potential remedies were infrastructure and technology, not provision for the poor.Footnote 37 As Pelling shows, Southwood Smith’s views were criticised by his contemporaries ‘as categorical, philosophically affected, and redolent of a lack of both sobriety and experience’ when he published his A Treatise on Fever in 1830.Footnote 38 His 1838 report espoused the same views and he was severely attacked again.Footnote 39 The January 1841 edition of the British and Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review assessed that his speculations took medicine ‘a century back in etiology’.Footnote 40 Nevertheless, Southwood Smith’s work, along with the corroborating report of Arnott and Kay, provided, in Hamlin’s terms, ‘the gift of medical authority’ to Chadwick, and became the intellectual cornerstone of Chadwick’s sanitary ideal.Footnote 41

We have stressed the debated and debateable nature of Southwood Smith’s fever theory to underline that Walker was not, as most scholars have claimed, summarising the broad opinion of medical practitioners in Gatherings from Grave Yards. Instead, Walker identified the city graveyard as another source of Southwood Smith’s poison. As Walker explained:

The vast numbers of burying places within the bills of mortality are so many centres or foci of infection – generating constantly the dreadful effluvia of human putrefaction – acting according to the circumstances of locality, nature of soil, depth from the surface, temperature, currents of air – its moisture or dryness, and the power of resistance in those subjected to its influence – (and who is not?) – as a slow or energetic poison.Footnote 42

The effect of this poison was the production of typhus fever.Footnote 43

To support his views, Walker provided evidence from medical writers. This comprised two separate sections. The first section was a translation from the French by Walker of M. Vicq. d’ Azyr’s ‘On the Dangers of Interment’.Footnote 44 This was partly a historical summary of ancient burial practices, and partly a summary of the development of cemetery standards in France, which included practices like graves being dug to at least five feet. The second section extracted medical writers demonstrating the dangers of city interment through ‘facts and experiments’. After briefly summarising how putrid matter could be carried in the air from insalubrious places, Walker quoted and abridged work by prominent contemporary medical writers such as Antoine-François de Fourcroy, John Armstrong, Xavier Bichat, and James Macartney. Furthermore, he illustrated Macartney’s statement that the gases generated in the initial and extreme stages of putrefaction were the most dangerous by providing several corroborating cases of his own and others; he criticised Mathieu Orfila for understating the danger posed to gravediggers; and he speculated that the ‘generation of fugacious poison’ – which gravediggers believed originated in the abdominal cavity and was ‘capable of distending and even rending asunder’ cadavers – could not only originate in abdomen.Footnote 45 The section ended with his comments on the commissioner’s reports, outlined above.

What Walker did not do in his medical summary was engage with work that dissented from: (a) Southwood Smith’s views on there being a single fever poison, or (b) the view that burial in cities was bad for the health of the local population. Both views were amply available in the literature. (a) Walker simply ignored the substantial contemporary literature concerned with the causal links between destitution and fever, limiting his analysis of other authors to their direct statements on putrefaction and/or the dangers of graveyards.Footnote 46 The main consideration Walker gave on the effect of poverty was by emphasising that the poor were merely more susceptible to fever due to ‘their circumstances, their condition, their habits, and modes of living’ – in short, it was partly due to the lack of infrastructure, but it was also their own fault, as the commissioners argued.Footnote 47 Similarly, (b) several medical authors denied that putrefaction from dead bodies caused fever, and therefore denied that city churchyards were centres of infection. For instance, the prominent Manchester physician John Ferrier had argued that the smell of putrefaction was insufficient to cause fever in part because of the evidence that churchyards provided.Footnote 48 Henry MacCormac’s 1835 book on fever acknowledged the dangers of city interment, but went on: ‘it seems quite certain that mere putrefaction has no such influence. … the contents of grave-yards, as in the noted case of the cemetery of the innocents at Paris, have been removed – …without in any case, producing fever, or at least, rendering it perceptibly more frequent than under other circumstances’.Footnote 49 Addressing either of these concerns would have potentially undermined his argument. Instead, by ignoring these lines of debate Walker provided a partial reading of the contemporary literature in order to bolster his case, in turn providing the Poor Law Commission with clear medical support for burial reform, uncluttered by academic nuance. This was the same tactic that Chadwick used to promote infrastructure over relief for the poor.Footnote 50 The only nuance Walker did provide was to acknowledge that the kinds of infrastructure the Poor Law Commission was concerned with were indeed on a similar par with that of the state of burial.Footnote 51

As well as paralleling Southwood Smith’s medical theory, Walker paralleled how the commissioners presented their findings to drive home the idea that graveyards were a comparable nuisance to issues like water supply, sewerage and rubbish removal. Arnott and Kay’s report provided narrative and numerical accounts of their locales that were intended to illuminate the national picture, in keeping with contemporary statistical science.Footnote 52 Thus their report contained a series of ‘illustrative facts’ by Arnott on origins of filth in the capital, which were really his ad hoc local observations; statistical analysis by Kay on the ‘state of the streets and houses’ in Manchester (calculating numbers of ill-ventilated, unpaved streets with stagnant refuse, and so on); and a series of letters from various sources on local nuisances across London.Footnote 53 Walker provided a section to match, ‘Of the Present Modes of Interment’, which provided illustrative facts (for example on the ‘management’ of graveyards by gravediggers), statistics (over two million buried in London from 1741 to 1837), and letters from relevant witnesses.Footnote 54

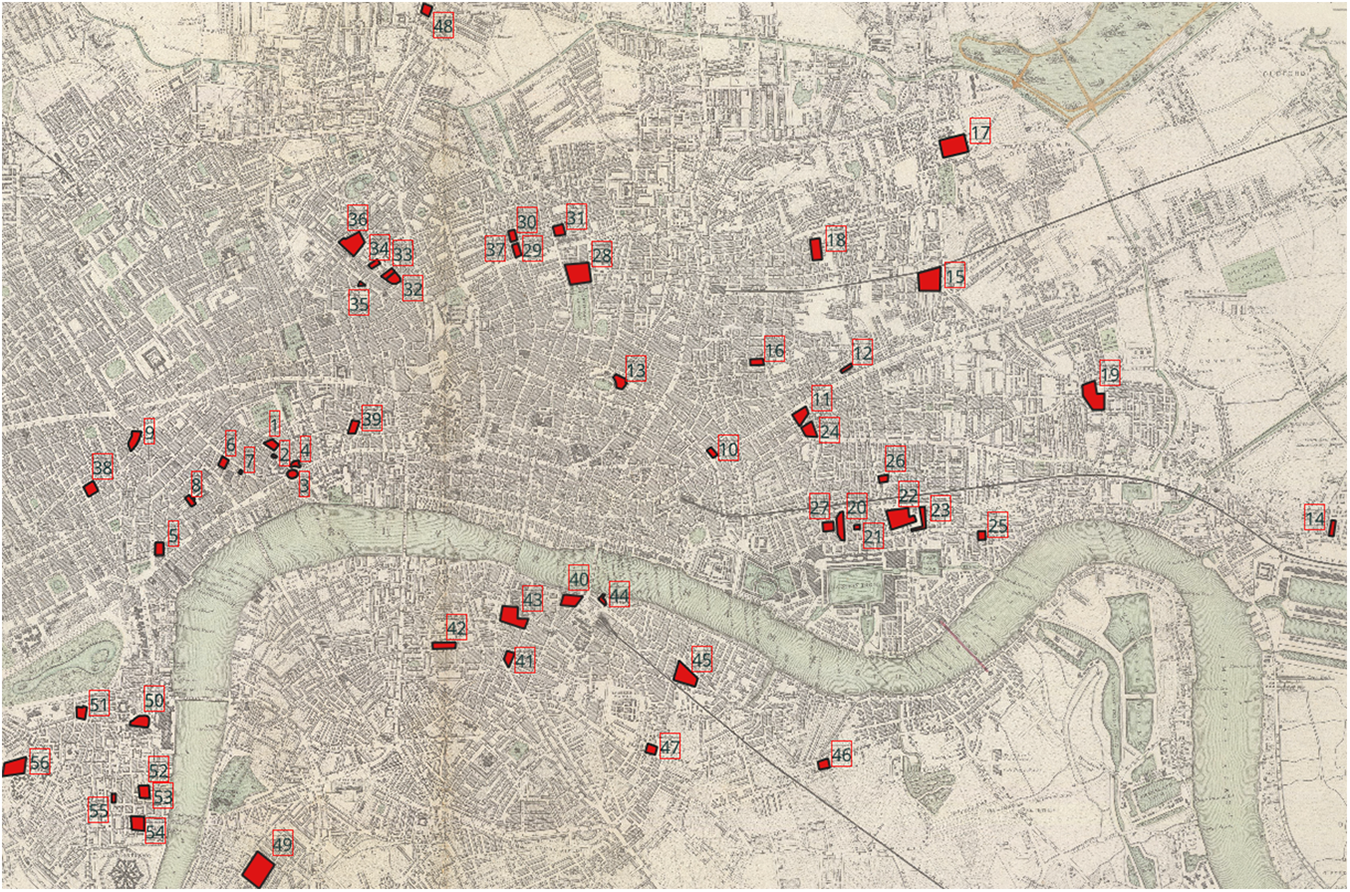

Walker also paralleled aspects of Southwood Smith’s reports. Southwood Smith’s two reports comprised firstly of his main report (quoted at length by Walker), which summarised his findings on the causes of fever from his work at the London Fever Hospital and subsequent investigations.Footnote 55 These investigations included Southwood Smith’s ‘Personal Inspection of Bethnal Green and Whitechapel, in May, 1838’, published in full as his second report. Such inspections had become increasingly common in the 1830s as reformers published social investigations incorporating tours to support their calls for reform; reform that was necessary to head off the prospect of revolution.Footnote 56 Walker provided much of the same for the Poor Law Commission in Gatherings from Grave Yards. His virtual tour of London burial grounds is the most famous aspect of his work, presenting a dire picture of city burial. It also covered much of the same physical ground as Southwood Smith. This is shown in Figure 1, where we have plotted the streets/graveyards directly profiled by Walker (see also Table S1 in appendix for full details).

Figure 1. Cemeteries listed in George Alfred Walker’s Gatherings from Grave Yards (1839) in order of their discussion. All graveyard locations approximate (see Table S1 in Appendix for details). Map: B.R. Davies for the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, ‘London, 1843’ (London, 1844), accessed via David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries (davidrumsey.com last accessed 22 April 2024). Locations were plotted using QGIS and London Burial Grounds (londonburialgrounds.org.uk last accessed 22 April 2024).

Southwood Smith listed the ‘most remarkable’ of the affected districts as St Clement Danes (Strand), St Giles and St George (Bloomsbury), and St Andrew’s (Holburn). Walker began his own tour in the Strand near his residence, with the centrally located St Clement Danes being the fourth graveyard covered. He also covered Elim Chapel on Fetter Lane in Holburn (no. 39, on the same street as St Andrew’s), though omitted Bloomsbury. More significant was the similarity between Southwood Smith’s tours of Bethnal Green and Whitechapel – where ‘the very worst forms of fever always abound’ – and Walker’s own tours of the same districts.Footnote 57 As is evident from Figure 1, Walker worked to supplement Southwood Smith’s tour directly, particularly the clusters around Bethnal Green (nos. 11–18) and Whitechapel (nos. 21–27). Additional burial grounds were covered because some churches had out-grounds to the main church graveyard, such as St Mary’s Catholic Church in Moorfields (no. 13) which had a burial ground in Poplar (no. 14).Footnote 58 Walker also covered areas such as Southwark (nos. 40–47) and Westminster (nos. 50–56) to broaden and underscore his point that city burial was not acceptable in any part of London.Footnote 59

Walker’s recommendations to combat this nuisance aligned with the political and social aims of the commissioners. As Hamlin has summarised, their interest was in what ‘Proper sanatory measures’ might be undertaken to improve the state of towns without addressing ‘the great social issues of prices, wages, hours, and liberty’ – a focus on filth, not poverty.Footnote 60 Following Arnott and Kay’s lead, Walker recommended national legislation to centralise the control of burial, arguing that the current largely unregulated system led to profiteering, low standards and ‘criminal’ treatment of the dead.Footnote 61 Overcrowding was a chief culprit of poor conditions, and was particularly bad in privately owned burial grounds.Footnote 62 Owners of private burial grounds profited by overcrowding their grounds, while the lack of regulation shielded profiteers from legal culpability. Walker’s characterisation of these practices as ‘criminal’ was thus rhetorical rather than legally correct, but this was his point: that the real ‘crime’ was that these practices were not necessarily illegal. As a result, he argued that private burial grounds should ‘Unquestionably … be immediately and for ever closed’, with the thorny issue of the proprietor’s land ownership settled by their receiving ‘a just compensation for their interest in the LAND ONLY’. Instead, Walker argued that Britain ought to follow the French system. They had legislated at the national level to relocate burial outside towns following the advice of ‘scientific and professional men’. Furthermore, Walker suggested establishing a registry of burial grounds to record the capacity of graveyards monitored by a ‘responsible superintendent’.Footnote 63

Walker thereby concurred with the general thrust of the reports to the Poor Law Commission in their medical theory, presentation of information, and recommendations for reform. By doing so he represented burial reform as an appropriate potential target for the Poor Law Commission. However, as discussed in the introduction, burial reform came with additional political challenges which elevated it beyond simple nuisance removal – its associated vested interests and vestry interests. That is, the important role of burial fees in supporting church parishes, and the profitmaking potential of private burial grounds. This probably accounts for why burial reform was not taken up as a concern of the Sanitary Inquiry that led to Chadwick’s Sanitary Report (1842), despite Walker being called in 1840 to R. A. Slaney’s Select Committee on the Health of Towns, which heavily influenced the agenda of Chadwick’s report.Footnote 64 But being amenable to the wider aim of nuisance removal was ultimately a boon for Walker’s cause. Chadwick based much of his later Interment Report (1843) on Walker’s book and via the testimony he had given in 1840.Footnote 65 This led, for example, to Walker’s new recommendation for superintendent oversight of burial grounds being taken up by Chadwick as part of the role of Medical Officers of Health.Footnote 66

Promoting his cause, 1840–1843

Despite Walker’s recommendations being taken up by Chadwick, throughout the 1840s it was not clear that burial reform would progress along the lines that Walker advocated due to the additional, or at least separate, political challenges reforming burial encountered compared to sewerage outlined above.Footnote 67 By 1846 the Provincial Medical & Surgical Journal was lamenting ‘the arduous and lengthened conflict he [Walker] has had to endure’ in the cause of burial reform, which remained several years away.Footnote 68 This section examines Walker’s initial campaign for burial reform, 1840–3, which focused on directly appealing to those with decision-making powers or influence: politicians, clergy, and medical practitioners generally. To do so, Walker used a campaign strategy of petitioning, letter-writing and pamphleteering that primarily repurposed and repackaged his existing work for these key audiences. For politicians, his pamphlet The Graveyards of London collated and summarised the aspects of his work that had particularly interested the 1840 Select Committee on the Health of Towns. His petitions to the clergy and legislators emphasised the moral and legal duty which they had to change matters. To his opponents, he wrote letters that underlined his scholarly disinterestedness in the matter, reasserted the accuracy of his observations and stressed that the facts spoke for themselves. And in the same letters, he argued for the particular expertise of medical practitioners to solve the problems of burial. This latter point utilised suggestions that had been made in medical reviews of his work and was included to appeal directly back to medical practitioners. In doing so, Walker drew lines of support and opposition that remained throughout his reforming campaign. This was particularly influential in providing medical practitioners with positive reasons for supporting Chadwick’s sanitary reforms: they promised much-needed salaried positions.

Following his Select Committee appearances in 1840, Walker initially continued his campaign through petitions and pamphleteering. In June 1841 he wrote to the bishop of London on the condition of the city’s graveyards, which secured him two subsequent interviews with the bishop, but without result.Footnote 69 This was in part because the bishop himself had lived near a cemetery in Bishopsgate without ill effect.Footnote 70 In August, Walker’s pamphlet The Grave Yards of London presented a shortened and reorganised version of Gatherings from Grave Yards which was appended by Walker’s testimony in front of the Slaney committee. It retained most of Walker’s graveyard tour, as well as selected passages from the rest of the work, and opened with a rewritten version of the section that underlined the duty that society had to dispose of the dead decently.Footnote 71 Most of the other retained sections were those which were directly comparable with Arnott and Kay’s report (see above). The historical and medical sections were much reduced, and French legislation only briefly discussed, mirroring the focus of the Select Committee questioning, which largely ignored these aspects of Walker’s work. The pamphlet was thus aimed at the current interests of potential legislators, whilst Walker explained that its ‘condensed and cheap form’ was intended to ‘diffuse more generally, information, instruction, and the author ventures to believe, conviction’ on the subject – a short and sharp format that Walker would return to for different purposes throughout the rest of his campaigning career.Footnote 72

Walker’s focus on appealing directly to Parliament gained initial success. In January 1842 he wrote a letter to the Home Secretary, Sir James Graham, before sending a full petition to Parliament in February.Footnote 73 This helped to secure a Commons Select Committee on interment in towns, led by the MP for Lymington, William Mackinnon. It was purposefully broader than Walker’s own inquiry, gaining oral and written testimony from a range of interested parties across Britain. But Walker’s work was central to the committee’s findings. As well as appearing twice before the committee, on 6 and 20 April 1842, Walker and his work was regularly discussed by other witnesses.Footnote 74 In the final report, Walker was vindicated by the committee, who recommended legislation against burial in towns. MacKinnon prepared a bill but it was never proposed, and the cause of burial reform was ultimately unsuccessful in 1842.

This was due to a combination of factors. On one hand, there was significant opposition by interested parties – resistance came from Anglican, non-conformist and secular controllers of cemeteries whose income was threatened, as well as medical practitioners who were unconvinced of Walker’s findings.Footnote 75 On the other, opposition came from reformers themselves. Chadwick criticised the potential bill’s restricted remit, which was limited to the prohibition of burial in towns and providing powers to municipalities to construct cemeteries outside their towns.Footnote 76 The government neither wished to aggravate those interests nor produce inadequate legislation.Footnote 77 Instead, the Home Secretary requested that Chadwick prepare a supplementary report to his main Sanitary Report (1842) on interment in towns. This appeared the following year – the aforementioned Interment Report – but in 1842 the momentum behind burial reform had stalled. As well as political problems, the country’s improving economic situation also stymied action, as new private cemeteries were built across Britain, which promised to alleviate some ongoing burial pressure.Footnote 78

With progress halted in 1842, Walker turned to letter writing. Beginning in November, he penned a weekly letter to the Morning Herald to promote the cause of burial reform. These letters were, in turn, published in collected form in 1843 as the pamphlet Interment and Disinterment. Again, much of their content stemmed from Gatherings from Grave Yards, but similar to The Grave Yards of London, Walker responded to the changing political situation and reviews of his work by changing the emphasis of his output. First, Walker now had a discernible opposition party to direct his arguments against, and he wrote against them directly. Walker’s first letter (3 November) identified them (possibly sarcastically) as ‘religionists’ from ‘a highly respectable body’, while letter viii (5 January 1843) detailed that this body constituted an anonymous letter writer, ‘Bornoyeur’, and a newly formed Anti-Abolition of Intra-mural Interment Society.Footnote 79 The writer was, in Walker’s terms, ‘a so-called minister of the Gospel’ who wrote to the ‘professedly religious organ, the PATRIOT newspaper’.Footnote 80 The letters by Bornoyeur were published in collected form by the ‘Committee for Opposing the Bill for “The Improvement of Health in Towns”’. They dismissed Walker’s account as a ‘mass of fictitious horrors’, disputed witness credibility, lampooned committee members, and characterised Walker’s allegations related to Enon Chapel’s overstuffed burial vault and its minister (the vault had closed following the minister’s death in 1839) as a ‘foul and cruel calumny on the memory of a beloved husband and revered father’, thereby publicly calling into question Walker’s evidence and moral character.Footnote 81

Walker in turn presented his detractors as misunderstanding and misrepresenting his case, asking for ‘a fair field and no favour’ in correcting their mistakes. His first letter underlined his own disinterestedness in the matter (‘I have never been connected, directly or indirectly, with any cemetery; I have nothing to gain, nothing to lose’) and the concurrence of the Mackinnon Committee and its witnesses with his position. Thus, his argument was that if the ‘religionists’ would only look at the facts before them, their objections would dissipate.Footnote 82 The exposition of these facts was the main purpose of the remaining eight letters, the publication of which concluded on 12 January 1843. This emphasis on facts was new in Walker’s output and had been suggested by the general press’s reaction to his work. The periodical The Age summarised that opinion, stating that Walker’s ‘accumulation of facts’ convinced the reader ‘of the importance of the case which he so fully makes out’.Footnote 83 As the general reader would be convinced by the weight of facts, so too would the partial one.

Alongside this new emphasis on facts, Walker also argued for the specific expertise of medical practitioners over questions of burial reform, using an argument that had been made in the medical press in relation to his work.Footnote 84 The Lancet made this argument across three reviews in subsequent editions from November 1839. The first review was most explicit on the matter. It asserted that medical practitioners were well placed to deal with questions regarding interment, despite the notorious controversies that put the profession on the defensive regarding the treatment of cadavers, and which had ultimately led to the passage of the Anatomy Act (1832). In its current state, dissection was more respectful than burial, the author argued.Footnote 85 Medical practitioners were also best placed to investigate the effects of grave gases, and to link those effects to ‘the morale and physique of the surrounding population’.Footnote 86 The medical press was keen to emphasise their specific expertise on these matters because it followed that they would gain employment opportunities. The Lancet’s argument that more research on the dangers of grave gases was needed necessitated medical employment: the subject was ‘too extensive for a private individual, and well deserves to be undertaken by the government’ who can use ‘accurate methods of chemistry, experimental physiology, pathology, and vital statistics’ to discover the ‘direct and indirect effects of the church-yard poison’.Footnote 87 Similarly, the Provincial Medical & Surgical Journal, writing after the Slaney Select Committee on the Health of Towns (1840) had reported their findings, advocated a new role for medical practitioners. They suggested that the Slaney Committee’s recommendation to establish local boards of health should be modified primarily to omit poor law officers, include medical professionals, and make them answerable to a central board of health that was itself directly answerable to the Home Secretary.Footnote 88

The utility of Walker’s work for medical practitioners and the emphasis on their importance in running the proposed burial system go some way to explaining the generally favourable response it received. As Irvine Loudon and Anne Digby have shown, nineteenth-century medical practice was characterised by fierce competition between physicians, surgeons and surgeon-apothecaries for patients and positions such as Poor Law appointments. Accusations of ‘overcrowding’ were common, with excessive competition blamed on low fees and the low social status of many surgeon-apothecaries (like Walker). Appointment to a salaried position, whether part- or full-time, was therefore an important avenue through which surgeon-apothecaries could organise a portfolio career and avoid underemployment, particularly in the provinces.Footnote 89 During the century, there was, according to Digby, ‘an increasing range’ of such salaried positions: from work in public institutions such as workhouses and asylums, to roles like certifying factory surgeons and private employment by mining and railway companies.Footnote 90 The potential new role inspecting graveyards therefore offered much-needed work, as well as attendant political and social influence. This was not to say that Walker’s work was wholly accepted. His position on fever and the overall prospect of overturning burial customs were criticised, but the prospect of new employment for an oversupplied medical profession was reason enough to play down those concerns.Footnote 91 In doing so, the cause of burial reform provided medical practitioners with reason to support the general thrust of Chadwick’s developing sanitary movement.

This demonstrates the importance of burial reform to the overall success of the sanitary movement, as a potentially powerful lobby group was placated. Hamlin has focused on the work Chadwick did to avoid requiring the support of medical practitioners, arguing that by ignoring the fever-destitution debate in his reports, Chadwick effectively side-stepped the issue, marginalised those still concerned with destitution, and provided a clear way forward for infrastructure to be the answer to the question of public health.Footnote 92 However, the reaction of medical journals to Walker’s work shows that Chadwick’s sleight-of-hand was accompanied by positive reasons for medical practitioners to support infrastructure-focused sanitary reform: positions through burial reform. The result can be seen in reviews of Chadwick’s Interment Report (1843), which was praised in The Lancet ‘for the impression that it is calculated to create in favour of the value and importance of medical science to the community’. What made this a ‘juster appreciation of the merits and utility of the medical profession than he before deserved the credit of entertaining’ was ‘a complete review of the practice of interment in towns’ and, crucially, the prospect of respectable employment for medical practitioners:

a plan is laid down for the appointment of officers of public health, for visiting every dead body; ascertaining, as nearly as possible, the cause of death; giving notice to and assisting the coroner, if necessary; offering their services to the survivors in directing the funeral arrangement, and inspecting cemeteries. The scale of payment for this complex, arduous, and dangerous service, which must continually expose the officer to infection, and demand of him incessant labour, for death gives no holidays, – the scale of salary is proposed to be the same as for staff-surgeons.Footnote 93

Following the publication of Chadwick’s Interment Report and the commencement of the Royal Commission on the Health of Towns and Populous Districts in spring 1843 the cause of burial reform was well served, and Walker’s campaign paused through the remainder of the year.Footnote 94 It appears that this pause was also in part for personal reasons: Walker seems to have moved house around this time, to St James’s Place, and also joined the board of a life assurance company.Footnote 95 But the real prospect of legislation being passed lessened the urgency of Walker’s cause also.

Causing sensation and broadening the constituency for reform, 1844–1852

Walker’s next phase of campaigning began in December 1844, the same month that the Health of Towns Association was founded by Southwood Smith. The Association listed burial reform as one of its key subjects on which to ‘diffuse information very extensively among the Working Classes, by addresses from the Committee, Lectures, Public Meetings, Pamphlets, the formation of Libraries and every other available means’ – such public meetings and publications were the main business of the society from 1845 to 1847.Footnote 96 Walker’s return to campaigning focused on the same public, whom he would engage by a change in tactic: causing sensation. This marked a general change of strategy by Walker that attempted, along the lines of the Health of Towns Association, to broaden the constituency for reform. Campaigning associations and societies were important to this shift of strategy. As well as the Health of Towns Association, burial reform was supported by other societies such as the National Philanthropic Association, and Walker’s own new society, the Metropolitan Society for the Abolition of Burial in Towns (henceforth Metropolitan Society). Now Walker’s public presence – physically and rhetorically – became more significant in his campaign activities. He gave public lectures and attended public meetings, was President of his own society, and most strikingly of all, purchased, exhibited and cleared the vault of Enon Chapel; the spectacle of which attracted thousands of onlookers. All the while, he continued to publish pamphlets, which continued to remind the legislator and medical profession of the need for reform. This was complemented by newspaper articles written and arranged by Walker to reach a broader reading audience, who might exert pressure on the government on their own initiative. As public health bills were finally passed from 1848, Walker’s campaign wound down; his remaining work was limited to two pamphlets that exhaustedly reiterated his main points once again. By the end of his campaign, medical journals were already lionising his success, and held Walker up as a model for other medical practitioners to follow.

To launch his new campaign of generating sensation in 1844, Walker focused on two cases. First, he wrote and circulated a paper on the current state of Enon Chapel, which had been sold and repurposed as an event space for a Temperance association following its closure in 1839.Footnote 97 The paper, entitled ‘Dancing Over the Dead’, focused on the ‘plain and fancy dress balls’ that now occurred there directly over the overstuffed vaults below.Footnote 98 The article appeared in multiple local and national papers simultaneously on 21 December, and was reprinted in further outlets throughout the first two weeks of January 1845, but with little further comment at this stage.

His second case was more successful initially. In January 1845 he wrote ‘to the Editor of every newspaper in the United Kingdom’ concerning ‘A London Golgotha’, the Spa-Fields Burying Ground, where graves were reportedly being disinterred with the remains burned in order to make room for new burials.Footnote 99 There was an immediate public reaction. By late February, an application to close the burial ground was heard in Clerkenwell Court. The graveyard manager ‘and mathematical instrument maker’, Mr Bird, who had denied Walker’s accusations in an earlier letter, was called before the court on the last day of February for cross-examination. The Home Secretary was soon alerted to the situation and ordered an inspection of the graveyard.Footnote 100 On 9 March, ‘many hundreds of persons were present in the grave-yard’ to ask about the burial of friends and relatives, and to see the state of the ground for themselves. Soon after, the ‘system of INHUMATION and CREMATION pursued … suddenly ceased’. Walker followed up this success by publishing a triumphant summary of the case in a letter to the Sun, published on 27 March.Footnote 101 The government, local judiciary and public, it seemed, agreed that the current state of burial required reform.

However, the public health bill introduced by Lord Lincoln at the end of the 1845 parliamentary session disappointed Walker as ‘his Lordship has not at present found time to attend to this important subject’.Footnote 102 In response, Walker commenced the busiest stint of public health campaigning of his career (1845–7), all with the aim of creating as broad a constituency for burial reform as possible. This motivated the foundation of the Metropolitan Society and stimulated Walker ‘to throw together in a brief form an account of my labours and their results’ in a new pamphlet, Burial Ground Incendiarism, published in early 1846.Footnote 103 Its title capitalised on the attention brought by his Spa-Fields exposé, with its content being a summary of his campaigning to date along with his 1845 letters to newspapers, primarily on Spa-Fields. Another 1846 pamphlet collated the ‘Opinions of the London and Provincial Press’ on Walker’s assorted works, emphasising national interest in the subject.Footnote 104 In mid-1846 it seemed as though Walker’s cause would be successful at last; the Provincial Medical & Surgical Journal reported that a bill ‘is about to be introduced into Parliament for the remedy of this growing evil’.Footnote 105 Yet by the end of the year, the same journal was lamenting the slow progress of burial reform. They did, however, ‘rejoice to see Mr. Walker again at his post in the prosecution of his benevolent purposes’. They hoped in particular ‘that the public press will now especially aid him with powerful assistance’.Footnote 106

To that purpose, in November 1846, Walker commenced a series of four lectures at the Mechanics’ Institution on Chancery Lane. These lectures largely reiterated his work to date but were a conscious attempt to broaden the constituency for burial reform by broadening public understanding of the issue.Footnote 107 Associated with his new society, Walker now utilised strategies of other similar public-facing scientific societies. Public-facing lectures were increasingly common in the mid-nineteenth-century as organisations like the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (1826–46) and the British Association for the Advancement of Science (1831–) aimed to improve the common knowledge of science and create a working-class constituency for ‘scientific’ policy.Footnote 108 These lectures were often accompanied by accounts of their content in pamphlets or in the press, which Walker’s own Metropolitan Society duly obliged by sponsoring the publication of his lectures in 1847.

Walker was by now fully ensconced in the public health circle around the Health of Towns Association. This is evident from Walker’s participation as part of a committee to raise funds for the widow and children of Dr Jordan Roche Lynch, who had died in service ‘devoted to sanitary reform’. The committee included notaries such as The Lancet founder Thomas Wakley, as well as Chadwick, Southwood Smith and Arnott.Footnote 109 Once again, a burial reform bill seemed close at hand, with The Lancet congratulating Walker ‘for this wholesome reform’ in March 1847.Footnote 110 But, once again, the bill did not materialise. This time due to the general election held that year. So, Walker continued to promote his cause to a broader audience in new and increasingly dramatic ways; namely, by returning to the case of Enon Chapel.

Late in 1847 he began collaborating with a new penny publication, The Poor Man’s Guardian. The newspaper was the voice of the progressive and newly founded Poor Man’s Guardian Society (1846) chaired by the reformer Charles Cochrane, who wrote most of its articles himself.Footnote 111 Such cheap, mass market, serial publications had become crucial to the discussion of science in wider culture, and were potential avenues for social campaigning.Footnote 112 Cochrane was a passionate reformer who was deeply concerned with issues of public health. He was founder (in 1841) and President of the National Philanthropic Association, a member of the Health of Towns Association, and a member of Walker’s Metropolitan Society. In turn, Walker was a member of Cochrane’s National Philanthropic Association, which published on ‘sanitary progress’.Footnote 113 The very first issue of The Poor Man’s Guardian contained a description of a visit that Cochrane made with Walker and other members of the Metropolitan Society to the vault of Enon Chapel, which was described in lurid detail.Footnote 114 The visit began a series of articles through November and December that attempted to inflate the importance of the issue. For example, in The Poor Man’s Guardian’s fifth issue, 4 December, a letter to the editor on Enon Chapel by Cochrane, representing himself as the President of the National Philanthropic Society, formed the lead story.Footnote 115

Soon after, Walker was also physically catalysing sensation at Enon Chapel. While the precise chronology remains unclear, by late 1847, Walker was in possession of Enon Chapel as either owner or leaseholder, and opened it to visitors.Footnote 116 On Monday 16 November, Walker’s assistant ‘was engaged disinfecting the burying vault under Enon Chapel, by chlorine gas, preparatory to its being cleared’, with it being suggested that ‘the removal [of human remains] cannot take place before January without endangering public health’.Footnote 117 Despite this apparent danger, on Wednesday 1 December, the vault was ‘opened for public inspection’ and ‘lighted by four large gas-lamps, which expose to public view the mangled remains and empty coffins that are huddled together in confusion’.Footnote 118 Crowds gathered to witness the scandal, attracting considerable media coverage and local action.

Churchwardens of nearby St Clement Danes wrote to their local magistrate to request that the exhibition be shut down, it being offensive to both local feelings and health. They found themselves ‘at a loss to know what motive Mr. Walker, a surgeon, … could have in exposing such a nuisance, it being quite contrary to the doctrines promulgated by him, both in his lectures and writings upon the subject’. In response, Walker stated that ‘he hoped to see the executive authorities make themselves acquainted with the horrors of a system perpetrated and even tolerated in the very heart of the metropolis’ – insisting that the vault’s public exhibition was necessary, as people would not believe the conditions without seeing them for themselves.Footnote 119

Crowds grew so large that a constable was installed to control them, with access regulated by tickets obtainable from Walker’s house. These tickets were crucially not sold, but rather, offered in exchange for donations toward ‘the decent interment of the bodies’, which tactfully subverted criticism of Walker profiting from the ghoulish exhibition.Footnote 120 When approached by the local magistrate in response to the churchwardens’ complaint, Walker declined to close the vault but agreed to manage public disturbance better by regulating ‘the number and class of persons admitted’, before he ‘entered into some particulars respecting his services in the sanitary cause’ and gave the magistrate a pamphlet.Footnote 121 The vault’s opening was defended in the London Mercury by a fellow surgeon and also by a member of the Health of Towns Association on sanitary and moral grounds. They clarified that Walker had sought their advice in advance, kept the vault closed on Sundays ‘until after divine service’, and refused to admit children and ‘dissipated persons’.Footnote 122 In total, it was estimated that around 6,000 people visited the vault, including ‘many members of the House of Commons’.Footnote 123

Despite Walker’s initial insistence that the vault was being disinfected for clearance, the remains were still being exhibited in situ four months later.Footnote 124 This was possibly due to the expense of removal, and the difficulties Walker encountered in locating a suitable location for reburial.Footnote 125 It was only in late March 1848 that clearance occurred, with ‘several large waggons’ of remains being removed to Norwood Cemetery (an extramural cemetery established in 1837) over several nights, concluding around midnight on 26 March, for reburial in a grave measuring 9 × 9 × 20 ft, which contemporary coverage suggests was donated by the cemetery’s chairman and directors.Footnote 126 Surprisingly, this conclusion to the Enon Chapel saga was little covered in the press.

In 1848 a Public Health Bill finally passed with progress on burial reform finally established. A system of churchyard closure was outlined, and interments in churches constructed after the Act were prevented.Footnote 127 It also included a version of the medical officer role that had been the initial catalyst for medical support of sanitary reform along Chadwickian lines, though the role envisaged was quite different from its potential, and it was criticised by the Health of Towns Commission.Footnote 128 Other parts of the bill were disappointing for reformers too. For example, the clauses to allow local authorities to own and administer cemeteries were dropped on the bill’s third reading.Footnote 129 Also disappointing was the composition of the new General Board of Health: ‘Where is Mr. G. A. Walker, who has successfully laid bare, single-handed, so many revolting enormities’, asked The Lancet.Footnote 130 The Provincial Medical & Surgical Journal decried the focus on ‘foul sewers and drains’ over all else and joined The Lancet’s call for Walker to be appointed to the board.Footnote 131 Also disappointing was the omission of London from the provisions of the bill. In April, a public meeting of the National Philanthropic Association was called to consider ‘Has the City of London any and what right to be exempted from a general measure of Sanitary Reform?’Footnote 132

The questions of burial and London were made urgent by a new cholera pandemic in 1848–9. In preparation, emergency but inadequate legislation was passed on burial in September 1848.Footnote 133 S. E. Finer argues that a key problem became the refusal of local authorities in London to close burial grounds, as advised by the Board of Health. The board had no legal authority to order such closure, which allowed burials to continue and underlined the need for more robustly empowered burial reform.Footnote 134 The cause was taken up by newspapers and supported by ‘clamorously successful’ meetings of Walker’s society, now renamed the National Society for the Abolition of Burial in Towns.Footnote 135 Walker again promoted the cause with a pamphlet, Practical Suggestions for the Establishment of National Cemeteries (1849). One of his shortest at fifteen pages, this largely summarised his recommendations that had been supported and supplemented by the 1842 Mackinnon Select Committee. However, there was room for new innovations, such as using ‘funeral railway trains’ to remove bodies for burial from London.Footnote 136

In August 1850 a burial law passed. It was primarily based on Chadwick’s 1843 report, creating a theoretical monopoly on burial fees for the Board of Health, though other details on its implementation were sketchy. The bill was significantly opposed by London MPs, including Wakley (The Lancet’s founder), but comfortably passed into law with large majorities.Footnote 137 The Lancet viewed the bill as ‘the virtual overthrow of the system’, but highlighted that it had ‘grave and numerous faults’. Nevertheless, Walker’s work was fulsomely praised – ‘let it not be forgotten that to him, and to him only, is due the entire merit of having directed public attention to the matter’ – and a testimonial fund set up to reward Walker.Footnote 138

However, problems with the bill prevented its effective institution. Part of the problem was financial. A £40,000 annuity had been awarded to the Church, and the Treasury baulked at paying a potentially indefinite sum to buy graveyards, causing delays to the bill’s implementation.Footnote 139 For Walker, the Board of Health was to blame. He provided his own commentary on the matter in yet another pamphlet, On the Past and Present State of Intramural Burying Places, published in 1851, with a second edition published in 1852. In his view, the Board’s work had resulted in ‘Nothing – nay, worse than nothing; … Since August, 1850, the receptacles of this metropolis have received some 70,000 additional bodies.’ He called for ‘renewed action’, praised the press which had ‘done its duty in the most noble and disinterested manner’, and called for ‘the people’ to insist that intramural burial cease. In his second edition he went on to outline a ‘remedy’ to the current problems – primarily passing a new national act.Footnote 140 The Lancet’s review of the pamphlet barely discussed its content, but once again provided fulsome praise of Walker.Footnote 141 His point had been made and remade.

Effective legislation on interment was finally passed in 1852 for London and in 1853 for the rest of the country, ending Walker’s campaign. The Burial Acts, as Finer argues, were not necessarily better legislation, but they avoided the problems encountered by the Board of Health.Footnote 142 A properly financed system which linked cemetery closure with new cemeteries being opened was developed, the costs borne by Public Works Loan Board finance after approval by the Secretary of State. Furthermore, Burial Boards establishing new cemeteries had access to detailed guidance containing advice that included placing the cemetery ‘in such a position that any effluvia from the ground may be carried away from the town by the prevailing winds’ – Walker’s fever theory clearly influential – as well as advice on the depth of the grave (four feet for an adult) and formulas calculating the amount of burial space required for town and country populations respectively.Footnote 143 By April 1854, burial had ceased in over 100 London locations.Footnote 144 Reform continued throughout the 1850s as the Burial Acts continued to reshape burial in Britain.Footnote 145 Walker was consequently held up as an example of exemplary practice by the medical profession.Footnote 146

Conclusion

Walker’s campaigning career underlines that nineteenth-century cemetery reform happened due to a range of scientific, political and social contingencies. Scholars of death, burial and cemeteries have tended to represent the science as relatively undebated, with the associated hygienic reforms flowing logically from the sheer unsanitariness of graveyards and the clear danger they posed. However, reform did not ‘follow the science’. Many medical practitioners flatly disagreed with the model of fever proposed by Southwood Smith and its attendant implications that direct poor relief would not improve the health of the poor. Nevertheless, Walker’s work used Southwood Smith’s fever theory as part of his strategy to make the cause of burial reform appeal to the Poor Law Commission and the sanitary reformers who gradually coalesced around Edwin Chadwick. Gatherings from Grave Yards could be likened to a fifth report on the unhygienic state of London that agreed with the Commission’s broader aim to improve through infrastructure – in this case the development of extramural burial grounds. Though based on shaky theoretical grounds, the cause of burial reform was taken up by many medical practitioners, including by reforming publications such as The Lancet, because it potentially offered much-needed work and social status to underemployed surgeon-apothecaries. In turn, this provided positive reasons for medical practitioners to support Chadwick’s broader sanitary movement: sewers became acceptable because burial reform promised salaried positions.

Beyond being able to accept burial reform in theory, Walker took an active role in promoting the cause of burial reform throughout the 1840s. The different phases of Walker’s campaign underline that he adapted his messaging and communication strategies to the different audiences he was targeting. His initial appeals and petitions focused on the political elite from 1840 to 1843 were traditional campaigning strategies. His later turn to sensationalism, accompanied by his own campaigning society, served his aim of broadening the constituency for burial reform. This mirrored broader changes in the sanitation movement. By becoming involved in campaigning societies as well as founding his own, Walker inserted himself socially and politically in the right places to affect burial reform: alongside Chadwick, Southwood Smith and Cochrane at meetings.

The burial reforms that followed Walker’s campaign stemmed from the politics of the sanitary reform movement. The solutions were infrastructure first, and not necessarily the most hygienic, or respectful of funerary practices. Nonetheless, it was issues of perceived disrespect and indecency surrounding the treatment of the dead which proved a key catalyst for change within Walker’s evolving strategy. By stoking public outrage through articles on the Spa-Fields Burying Ground and high-profile stunts such as the exhibition of Enon Chapel’s burial vault, Walker engaged the public as well as medical and political professionals. By bringing together and harnessing the pressures exerted by multiple audiences, Walker and his contemporaries created an engine which not only drove reform forward, but kickstarted it whenever it stalled.

The stakes and results of this process were national as well as local, with London’s shift to extramural burial serving as a blueprint for national reform. This repositioning had a profound effect on the ongoing material and cultural evolution of relationships between the living and the dead in Britain, with its results tangible in the predominantly Victorian cemetery infrastructure and burial landscapes which remain visible and in use today.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0080440125100170.

Table S1: Placement and placement certainty of cemeteries listed in George Alfred Walker’s Gatherings from Grave Yards (1839) in order of their discussion.

Data availability statement

No new data were generated or analysed during this study.

Acknowledgements

This article was written as part of the authors’ participation in The Human Remains Project (UKRI Future Leader’s Fellowship, University of Liverpool). For their encouragement and feedback on the paper the authors would like to thank the project’s Principal Investigator, Dr Ruth Nugent, and participants at the Problematic Bodies Conference organised by The Human Remains Project at the University of Liverpool in 2023. Our thanks also to Dr James Butler who provided significant technical help in orientating the authors with the Human Remains Digital Library (HRDL: https://doi.org/10.17638/datacat.liverpool.ac.uk/3010). For their careful editing and suggestions for the article, our thanks to Dr Coreen McGuire, Dr Jan Machielsen, and the two anonymous peer reviewers.

Financial support

This work was supported by the UKRI Future Leader’s Fellowship ‘The Human Remains: a digital library of British science and mortuary investigation’ [MR/S032800/1/MR/X023567/1].

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Author biographies. Richard T. Bellis is Associate Lecturer in Medical Humanities at the University of St Andrews School of Medicine. His background is in the history of science and medicine, specialising in the history of anatomy, disease and science communication in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, with a particular focus on the use of human remains in medical research and the legacies of this research for modern medical collections. From 2022 to 2023 he was a Resident on The Human Remains Project.

Thomas J. Farrow is a Ph.D. candidate whose University of Liverpool doctoral scholarship is attached to The Human Remains Project. His thesis focuses on how disarticulated human remains (charnel) were managed, curated and encountered in English church(yard) and cathedral spaces, c.1500–c.1900. He has previously published on charnel in late medieval and early modern England, and institutional death and burial management in nineteenth- and twentieth-century British psychiatric hospitals.