Introduction

As Chapter 1 showed, the central economic and social role of the informal sector is increasingly appreciated. Yet while evidence shows that informal entrepreneurs can drive innovation, research on innovation in developing countries has been devoted mostly to formal sectors, organizations and institutions. What is lacking are studies assessing the role of innovation emanating within and from the informal sector. Who is the archetypical innovator in the informal economy? What types of innovations are generated? What is different from what one would encounter in the formal economy?

Finding answers to these questions is a new field of research. On the one hand, the literature devoted to the study of the informal sector does not directly address the topic of innovation. In fact, the ability of the informal economy to do “new things in a different way,” its inventive ingenuity, rarely features as a topic at all. On the other hand, the equally vast literature on national innovation systems in countries at different stages of development largely overlooks the informal sector.

The objective of this chapter is to push the boundaries of research in this field, first by conceptually integrating so far separate analyses of innovation and the informal economy and second by using research methods not often used by those studying the economic and employment aspects of innovation or the informal economy. The findings are based on an analysis of the existing literature, but more importantly on analytical fieldwork conducted for this book in three countries, and in the context of research undertaken by the Open African Innovation Research (Open AIR) network.Footnote 1

Defining Innovation

At the outset, it is important to establish a clear conceptual understanding of innovation. Often innovation is equated with research and development (R&D) – intensive technological breakthroughs or, in IP circles, patentable inventions. In the context of this book, however, a broader and deeper understanding of innovation is needed.

One does not need to reinvent the wheel for this purpose. In high- and low-income countries alike, for measurement purposes, innovation is now understood as the “implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service), or process, a new marketing method [e.g. a novel product design], or a new organizational method in business practices, workplace organization or external relations” (OECD/Eurostat 2005, p. 46). This definition includes incremental innovations that are new to the firm or new to the country.

According to this well-established innovation framework, innovation activities could include the acquisition of machinery, equipment, software and licenses, engineering and development work, design, training, marketing and R&D where undertaken to develop and/or implement a product or process innovation. Motives to innovate include the desire to increase market share or enter new markets, to improve the product range, to increase the capacity to produce new goods and to reduce costs.

While the above characteristics mainly describe innovation in relatively developed countries, they have also been adapted to developing countries and provide a good conceptual guidepost for studies of innovation in the informal economy.

However, measures of innovation based on the conventional definition given above may not always be appropriate in the context of developing countries or activities in the informal sector. Generally, definitions of innovation in developing countries posit it as a way to improve people’s lives by transforming knowledge into new or improved ways of doing things in a place where, or by people for whom, they have not been used before (Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae Reference Kraemer-Mbula, Wamae, Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae2010a). In Chapter 8 of this book, we examine how existing metrics, survey instruments, notions of collaboration and linkages, and impact assessment tools apply – or do not apply – in this setting.

What We Know about Informal Sector Innovation in Developing Countries

Clearly, innovation-driven growth is no longer the prerogative of high-income countries. Fostering innovation is now firmly on the agenda of many low- and middle-income countries to spur economic and social development (Lundvall et al. Reference Lundvall, Vang, Joseph, Chaminade, Lundvall, Joseph, Chaminade and Vang2009; Gault Reference Gault and Gault2010; Hollanders and Soete Reference Hollanders and Soete2010; NEPAD 2010; Dutta et al. Reference Dutta, Escalona Reynoso, Bernard, Lanvin, Wunsch-Vincent, Dutta, Lanvin and Wunsch-Vincent2015).

The fact that innovation should not be equated simply with R&D-intensive technological breakthroughs or patentable inventions is important in this context.

It is notable, however, that for the most part, studies and metrics of innovation in developing countries focus on large-scale, formal sector R&D activities, organizations and institutions.

Several insights can be drawn from this literature.Footnote 2 Generally, there is a lower level of science and technology (S&T) activity in developing countries than in developed countries, in part due to human capital and infrastructure constraints. Often, government and international donors are the main funders of S&T. National public research organizations are the main R&D performers. Also, government S&T expenditures often focus on agriculture rather than on engineering or industrial research. There is a lack of applied research, a deficit of trained engineers and scientists, weak technological capability and mostly inadequate scientific and technological infrastructures in these economies.

Limited science–industry linkages are explained by the low absorptive capacity of firms and an ensuing lack of “business” demand for S&T. Questions also persist about the relevance of research to the business sector. Finally, there is a lack of policies and institutional structures necessary to facilitate the establishment of new firms, as well as constrained access to financing.

While assessments of innovation systems in developing countries have produced a number of important insights, the informal sector is usually not considered a potential source of innovation. As noted by Maharajh and Kraemer-Mbula (Reference Maharajh, Kraemer-Mbula, Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae2010, p. 138),

The informal sector, especially in developing countries, comprises millions of enterprises that operate under extreme conditions of survival, scarcity and constraints. The dynamics of innovation in the informal sector, which is most extensive in developing countries, are largely ignored in the literature on both developing and more developed economies. Yet disregarding the role of such innovation in developing countries produces misleading, asymmetrical or ineffective innovation strategies.

At best, the limited literature focused on innovation in the informal economy has concentrated on the “development of technological capacity” and/or the purchase and use of machines to produce a given set of outputs (ILO 1972, 1992).

To be fair, an economic literature has developed that focuses on urban informal entrepreneurs in developing countries (Nordman and Coulibaly Reference Nordman and Coulibaly2011; Ouedraogo et al. Reference Ouedraogo, Koriko, Coulibaly, Fall, Ramilison and Lavallée2011; Grimm, Knorringa and Lay Reference Grimm, Knorringa and Lay2012; Grimm et al. Reference Grimm, van der Hoeven, Lay and Roubaud2012; Thai and Turkina Reference Thai and Turkina2012). The group of researchers involved in these studies consists mostly of labor economists who have continually improved the methods for surveying informal sector firms via better questionnaires and better sampling and data collection strategies (Joshi, Hasan and Amoranto Reference Joshi, Hasan and Amoranto2009). However, these studies generally do not focus on innovation, neither explicitly nor – for the most part – implicitly.

In addition, a fast-growing body of recent research has begun to identify innovation in low-income economies. Many terms and definitions have emerged in this context: “grassroots” innovation, “base-of-the-pyramid” (BoP) innovation, innovation “for the poor by the poor,” “frugal,” “jugaad” and “inclusive” innovation are just some examples that are relevant to this study of the informal economy,Footnote 3 although these terms are not synonymous (Gupta Reference Gupta2013). Some of this literature focuses on serving low-income populations through innovations on the consumption side, namely radically lower-cost goods and services that meet poor people’s ability to pay, thus providing business strategies for global firms entering emerging markets (Radjou, Prabhu and Ahuja Reference Radjou, Prabhu and Ahuja2012). Other studies look at the actual experiences and perspectives of “knowledge rich – economically poor people,” explaining how groups such as the Honey Bee Network have helped to catalog 140,000 grassroots innovations throughout India during the past twenty years (Gupta Reference Gupta2012b). This blossoming part of the literature increasingly encapsulates the study of the informal sector, though often without defining it as such.

Innovation in the informal sector is also largely overlooked in the available survey data. Even in those countries and regions for which surveys of the informal economy exist – for example, establishment or enterprise surveys and mixed surveys along the lines discussed in Chapters 1 and 8 of this book – the information gathered about informal employment and economic units is not directly related to innovation. Such data cover matters such as the socio-demographic characteristics of workers, terms of employment, wages and benefits, and the place of work and working conditions. Survey data and analysis that focus on firms relate to, for example, the size, type and industry of enterprise; bookkeeping and accounting practices of enterprises; input purchasing and investment; sales and profits; access to credit, training and markets; forward and backward linkages; major difficulties encountered in developing the business; and demands for public support (ADB 2011). One exception aside – see Fu et al. (Reference Fu, Zanello, Essegbey, Hou and Mohnen2014) for work surveying formal and informal textile firms in Ghana carried out in parallel to the fieldwork underlying this book – there has been no survey specifically examining innovation in the informal sector.

Partly in consequence, few existing innovation or S&T policy frameworks do target innovation in the informal economy (see Chapter 7 of this book and IDRC 2011).

In the following section, the innovation system approach is used to overcome the current knowledge gap and distil the main characteristics of innovation in the informal sector.

Analyzing Informal Innovation Systems

Whether exploring innovation within a conventional, formal paradigm or in the emerging context of informality, there is a consensus that the analysis of so-called innovation systems is required (see, e.g. Nelson (Reference Nelson1993), Freeman (Reference Freeman1987) and Lundvall (Reference Lundvall1992) on the innovation system literature).

This systemic approach takes a broader understanding of innovation, beyond R&D, taking into account the role of firms, education and research organizations and S&T policies and including the public sector, financing organizations and other actors and elements that influence the acquisition, use and diffusion of innovations (Freeman Reference Freeman1987; Lundvall Reference Lundvall1992). Understanding innovation as a systemic process puts emphases on its interactive character, the connections among actors involved in innovative activities and the complementarities that emerge between incremental, radical, technical and organizational innovations in the context in which they emerge. Innovation systems thus evolve as the result of different development trajectories and institutional evolution – with very specific local features and dynamics.

The existing literature building on the innovation system approach has largely been applied in high-income countries and the formal sector, but researchers are now starting to apply and modify the innovation system framework to the conditions of developing countries, where economic activities are largely informal (Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae Reference Kraemer-Mbula, Wamae, Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae2010b, Gault et al. Reference Gault2012; Konté and Ndong Reference Konté and Ndong2012; WIPO and IERI, 2012). Funding agencies also increasingly appreciate the need for better understanding of – and support for – the linkages between the supply of new ideas from research and the demand for those ideas by local economies (Rath et al. Reference Rath, Diyamett, Borja, Mendoza and Sagasti2012).

Usefully, this more recent work in developing countries also stresses the importance of the localized character of systems of innovation (Cassiolato and Lastres Reference Cassiolato and Lastres2008). For instance, the work of the Research Network on Local Productive and Innovative Systems (RedeSist) in Brazil has highlighted the local dimension of innovative and productive processes, aiming to identify challenges in and concrete opportunities for fostering local development (see also Soares, Scerri and Maharajh Reference Soares, Scerri and Maharajh2013). These systems range from the simplest, most modest and disjointed to the most complex and articulated (De Matos, Soares and Cassiolato Reference De Matos, Soares and Cassiolato2012). They include actors with (a) different dynamics and trajectories, from the most knowledge intensive to those that use traditional or indigenous knowledge, and (b) different sizes and functions, originating in the primary, secondary and tertiary sectors and operating on a local, national or international plane (De Matos, Soares and Cassiolato Reference De Matos, Soares and Cassiolato2012). This work provides a useful platform for incorporating a set of economic, political and social actors, including informal entrepreneurs that mainly operate “locally” in relatively small geographical territories.

Figure 2.1 illustrates how the informal economy would fit within such a “local innovative and productive system” framework, alongside the formal sector, suppliers, users and broader innovation parameters such as the economic and social context, the productive and national Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) infrastructure and relevant policies and regulations.

Figure 2.1 The informal economy in a local innovation framework

Note: Adapted from De Matos, Soares and Cassiolato (Reference De Matos, Soares and Cassiolato2012). Erika Kraemer-Mbula with comments from Christopher Bull, George Essegbey and participants in the International Workshop on “Innovation, Intellectual Property and the Informal Economy,” Pretoria, South Africa, November, 2012.

At the core of this framework, we find a diverse range of productive structures in developing economies. These comprise formal and informal suppliers exchanging goods, services and knowledge with formal and informal businesses (in agriculture, manufacturing or services), which in turn transform those inputs into goods and services that are distributed and commercialized through both formal and informal channels until they reach the final customers or users. This diverse productive system in developing countries is largely populated by micro and small enterprises, and the majority of them are informal.

The flows of goods and services around micro and small enterprises tend to remain in their immediate locality, especially in a context where insufficient infrastructure (both physical and digital) may limit the geographical coverage of productive activities. Similarly, the information and knowledge that is assimilated and used by productive organizations also tends to remain local. These knowledge flows would involve what are commonly known as the formal organizations – comprising training and education organizations, banks and other financial organizations, as well as formal representative associations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), community-based organizations (CBOs) and the like. There are also relevant organizations that may not hold a legal status but have some degree of structure and often membership, such as associations of traditional healers, apprenticeship training organizations and so on. It is inherently difficult to delimit these types of organizations, but they are nonetheless very relevant in shaping and steering knowledge flows, especially at the local level. In this respect, the local innovation system encloses the space where learning processes happen, productive and innovative capabilities are created and tacit knowledge flows are exchanged. In their context, therefore, territory, history and cultural context do matter.

Also importantly, as the figure illustrates, the informal economy is not disconnected from the range of economic and productive actors surrounding it. It interacts with and is influenced by parameters that are shared by formal sector innovation actors and networks. Moreover, the formal sector is impacted by the presence and activities of the informal sector as well. The most appropriate conceptualization of the informal economy (IE) is as a continuum from formal to informal, where different activities and actors occupy different places along the continuum. The transition from informal to formal status is gradual; single firms, households and workers may carry out some activities informally and others formally at the same time. In some circumstances, the IE competes with the formal sector. Often, however, the IE produces for, trades with, distributes for and provides services to the formal economy, interacting symbiotically (see Box 2.1).

Box 2.1 Evolving understanding of the informal economy

Traditionally, formal and informal firms and their characteristics have been juxtaposed as extremes on two opposite sides of a spectrum.

A typified view of the informal sector firm retained the following characteristics: (i) low entry requirements in terms of capital and professional qualifications; (ii) a small scale of operations, often with fewer than five employees; (iii) unskilled labor/skills often acquired outside formal education; (iv) labor-intensive methods of production and simple/adapted technology; (v) scarce capital, low productivity and minimal saving; (vi) an unregulated and competitive market; and (vii) family ownership of enterprises.

These characteristics were often contrasted to the somewhat idealized characteristics of formal firms, which are often presented as having the exact opposite characteristics, that is, large scale of operations, skilled labor, capital-intensive production and so on (ILO 1972; see Table 2.1).

As argued above, the more appropriate conceptualization of the informal sector is to look at it as a continuum, from formal to informal, where different activities and actors occupy different locations along the continuum. In reality, small firms in the formal sector probably share many commonalities with firms of the IE as to what innovation and the use of appropriation mean. The transition from informal to formal enterprise status is also gradual; indeed, single firms and single households/workers can carry out some activities informally and others formally at the same time.

The degree of informality, the type of activity, the technology used, the profile of the owner and the market characteristic in which the informal sector firm operates vary significantly from one firm to another. Some IE actors are single street traders with limited education and skills who essentially operate for subsistence. Others can be unofficial firms with labor-intensive or more knowledge-intensive operations. The latter can operate in markets with high barriers to entry and capital requirements and can be dynamic businesses with wage employment.

In some sectors, firms in the IE are perceived to be more competitive than those in the formal sector. Indeed, firms may prefer to remain small and informal, rather than large and formal, if they perceive advantages in doing so. Such advantages may include greater agility to respond to changes in the technological or competitive landscape, or resilience in the face of systemic macroeconomic risks and adversity such as the recent global economic crisis.

| Informal firms | Formal firms | |

|---|---|---|

| Business size | Small – fewer than five workers/paid employees | Large – greater than fifty workers |

| Start-up capital/ qualification | Low – easy to start a business | High – difficult to start a business |

| Factor of production | Labor intensive | Automated production |

| Work conditions | Unprotected by contracts, social welfare or unions | Protected by contracts, social welfare and unions |

| Skills | Skills passed on through informal apprenticeships | High-level skills from formal training institutions |

| Raw materials | Scrap from formal and informal sources | New from local and imported sources |

| Infrastructure | Unreliable power and insecure premises | Reliable power and secure premises |

| Resources | Limited access to capital goods and funding | Extensive access to capital goods and funding |

| Selling price | Affordable to local population | Out of reach of local population |

| Demand | Low | High |

| Quality | Low-quality goods | High-quality goods |

| Proximity to consumers | Close | Distant |

| Profit | Low | High |

| Medium of exchange | Cash | Cash and bank credit (e.g. credit card) |

| Market linkages | Poor distribution network, fragmented informational environment | Well-established distribution network |

| Flexibility | Adapts well to market conditions | Difficult to adapt |

| Efficiency | Efficiency through coordination among businesses | Efficiency through vertical integration |

| Risk attitude | Risk avoiders | Risk takers |

| Culture | Embedded in social relations | Relies on impersonal written rules of the firm |

Often, the IE produces for, trades with, distributes for and provides services to the formal economy. In some circumstances, the IE competes directly with the formal sector, at times with an unfair advantage, for example, because of tax or regulatory avoidance (Banerji and Jain Reference Banerji and Jain2007). In other circumstances, formal and informal actors and activities interact (Thomas Reference Thomas1995; United Nations 1996). Also, these informal firms often have direct backward or forward linkages with the formal sector.Footnote 4 Individuals switch between formal and informal work or, in many cases, engage in both types of activities. These linkages are important for understanding how firms “graduate” from an informal to a formal status (Charmes Reference Charmes, Jütting and de Laiglesia2009) – not least because the economic literature suggests that informal enterprises that have links to the formal sector are more profitable and dynamic than those that do not (Grimm et al. Reference Grimm, Knorringa and Lay2012).

This framework has been applied in the field research underlying this book.

The lessons generated are summarized in the following sections of this chapter. Importantly, the informal economy and its various sub-sectors and clusters are above all extremely diverse, as was noted in Chapter 1. The heterogeneity of the informal sector has been one of the most fundamental findings of research on this topic for decades (Mead and Morrisson Reference Mead and Morrisson1996).

Naturally, the diversity of the informal economy is also reflected in the innovation that goes on within it. Innovation activities are extremely diverse, as are the sources of knowledge, learning and innovation that shape and diffuse them. Broad generalizations about the entire informal sector must therefore be treated with caution. The incidence, characteristics, role and impact of innovation vary widely across the wide spectrum of varied informal economy clusters and sub-sectors. The findings presented in this book bear witness to the great heterogeneity that exists among informal firms within and across different sectors in terms of not only technological capabilities and capital endowment but also their interactions with the formal sector (see also Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae Reference Kraemer-Mbula, Wamae, Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae2010a).

This in itself is not necessarily surprising or a source of concern. Innovation in the formal sector also varies greatly across firms, sectors and regional clusters.

More generally, the findings in this book suggest that differences between formal sector and informal sector firms may be overstated. Empirical studies often conclude that informal firms behave much like a “normal firm” with formal skills but that they operate under various market imperfections. Furthermore, informal enterprises in developing countries are often as technologically innovative as their formal sector counterparts, or even more so. Clearly, both formal and informal enterprises are affected by the same “backdrop” that characterizes a developing-country economy – the institutional structures/constraints that may hinder access to financial resources, skills of the workforce, access to training, facilities, and other essential factors. In addition, however, mainstream producers in the formal economy actually often overlook many local needs, either because the market is not attractive enough to make a profit or because a certain product cannot reach the local market due to some technology, skill or environment-related constraint. Often, too, formal sector firms operate in rather uncompetitive markets with no incentive to innovate. Finally, they often lack absorptive and technical capacities and skills to innovate.

With these caveats in mind, the following insights into firms and innovation in the informal sector emerge from the fieldwork undertaken for this book and other recent research.

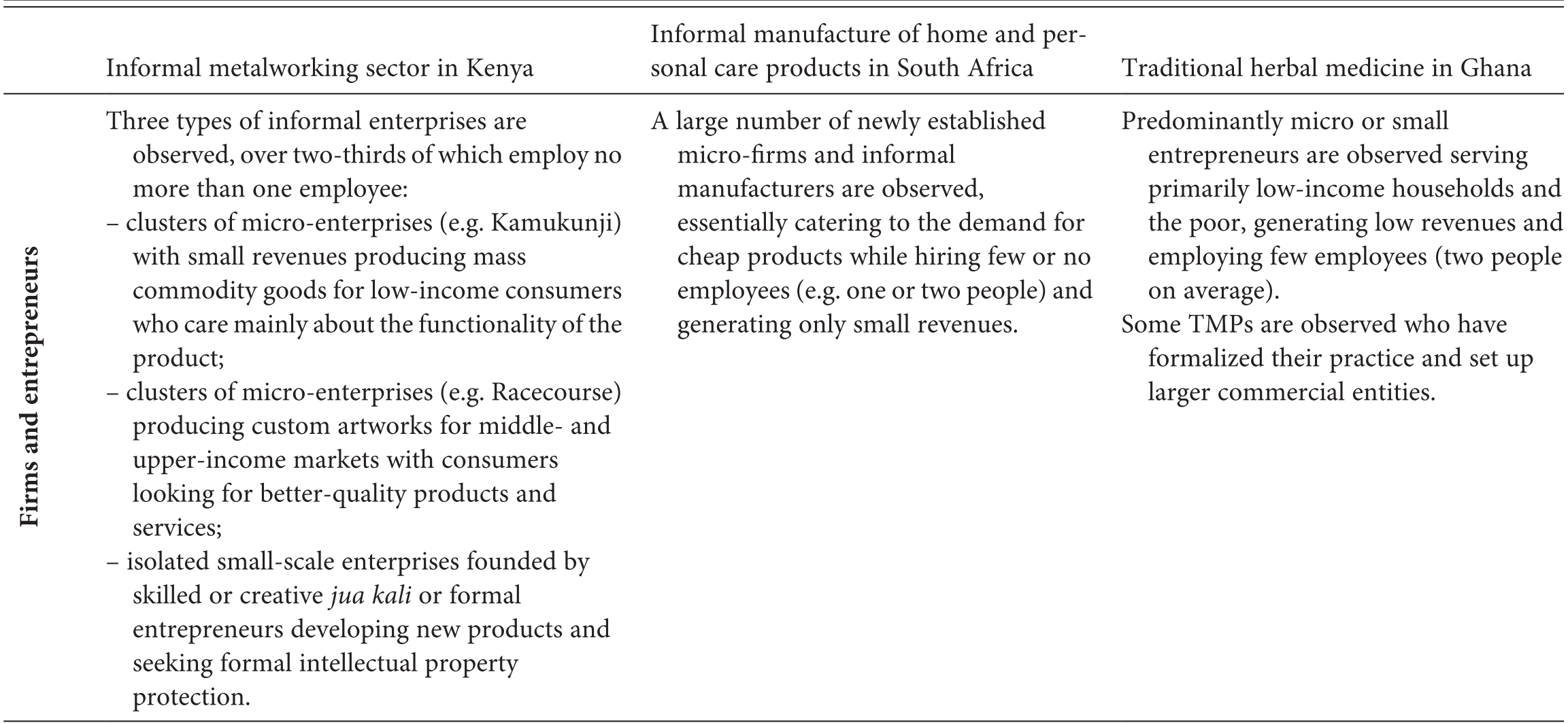

Firm Typology in the Informal Sector

Classifying entities in the informal sector into clearly distinguishable and markedly different groups has conceptual and practical appeal.

The literature often classifies the informal sector into two clearly distinct segments, the so-called lower tier and upper tier (House Reference House1984; Fields Reference Fields, Turnham, Salomé and Schwarz1990; Mead and Liedholm Reference Mead and Liedholm1998; Nichter and Goldmark Reference Nichter and Goldmark2009). The upper tier is characterized as having a growth orientation whereas lower-tier entrepreneurs are focused on survival (Grimm, Knorringa and Lay Reference Grimm, Knorringa and Lay2012). Evidently, informal sector actors of the lower tier have different characteristics from upper-tier actors with respect to firm demographics, profitability, growth prospects and linkages with the formal sector (Ouedraogo et al. Reference Ouedraogo, Koriko, Coulibaly, Fall, Ramilison and Lavallée2011). A bifurcation between a rather small group of successful entrepreneurs and a larger group of firms that struggle to survive is the evident result (Grimm, Knorringa and Lay Reference Grimm, Knorringa and Lay2012).

This binary classification is not perfect. Indeed, detailed empirical studies focusing on firm characteristics in the informal economy and our own fieldwork and survey results suggest that one can really distinguish three types of entities in the informal economy. In this updated framework, the so-called lower tier must be further subdivided between entrepreneurs who simply struggle to survive and those who have a more systematic approach to business organization and relevant profitability, but do not yet meet the criteria for membership of the small upper tier.

As noted by Grimm, Knorringa and Lay (Reference Grimm, Knorringa and Lay2012), who summarize the literature in this regard: “the typical informal entrepreneur, also in non-dynamic economies in Africa, should not too easily be labelled a survivalist waiting for a job opportunity, without entrepreneurial capacities or growth potential. We … show that among those entrepreneurs typically considered survivalists – mainly because they operate with very little capital and generate low profits in absolute terms – there is a substantial share of entrepreneurs with business skills and an entrepreneurial behavior that resembles [that] of upper tier entrepreneurs.” As Maloney (Reference Maloney2004) notes, self-employment instead often serves as the “unregulated developing country analogue of the voluntary entrepreneurial small firm sector in more developed countries.”

Following this three-tier approach, a study of the informal sector in West Africa covering Benin, Côte d’Ivoire and Togo by Grimm, Knorringa and Lay (Reference Grimm, Knorringa and Lay2012) identifies three sets of firms: (i) a limited number of high-growth firms referred to as “top performers”; (ii) a greater number of small structures with particularly high returns on investment but little capacity to expand, referred to as “constrained gazelles”; and (iii) a majority of firms termed “survivalists” that are essentially concerned with making a minimum of income for subsistence and are generally unable to consider making significant strides in more formal innovation (see Table 2.2). “Constrained gazelles” are mainly constrained by their business environment and thus external factors – lack of access to capital, insurance and productive infrastructure – rather than internal constraints such as education and specific business skills.

| Upper tier | Top performers | Better-off, growth-oriented entrepreneurs with high capital stock and medium to high return. |

| Middle tier | Constrained gazelles | Share many characteristics with top performers, including high capital returns, but face low capital stocks and constrained growth. |

| Lower tier | Survivalists | Share little or no characteristics with top performers; face low capital stock and low return. |

Concerning the upper tier, only a minority of firms in the informal sector can aspire to experience significant growth in revenue, to reinvest these proceeds and to have the luxury of thinking more systematically about various forms of product, process, organizational or marketing innovation. These firms are close to the formal end of the informal–formal spectrum, with significant scale, an established firm structure and organization, significant revenues and ability to invest, and overall rather formalized transactions and links to the formal economy. At the top of this scale, there are even dynamic, high-growth informal firms that operate in modern hi-tech industries (Günther and Launov Reference Günther and Launov2006).

The findings of the country fieldwork for this book show that the great majority of firms are micro and small enterprises, clearly different from those upper-tier firms with fast growth, profitability, capital and other investments, and an established and growing organizational structure.

Evidence from the home and personal care sector in South Africa – see Chapter 4 in this book – reveals that the majority of firms in the sector are micro-enterprises, with about 90 percent of the companies comprised of just the owner or only one or two employees. Most informal enterprises had been established recently (60 percent were between one and three years old) and reported low turnover. The fieldwork on Ghana’s herbal medicine sector described in Chapter 5 shows similar patterns. Traditional Medicine Practitioners (TMPs) are predominantly micro or small entrepreneurs; 70 percent of TMPs sampled in the study have no more than five employees.

The studies also show that only a minority can be regarded as upper tier. Few actors can be associated with highly innovative firms that increase their scale and scope. Indeed, only a handful of entrepreneurs in small businesses have formalized their practice and set up modern enterprises for the production and supply of herbal products. Undeniably, most micro-firms do not grow their business. Kabecha (Reference Kabecha1998) even argues that in the informal sector technology has often been used to maintain the market, not expand it.

Yet if one adopts a broad understanding of innovation as applied in this book, it is not necessarily reserved to the upper tiers of the economy. While categorizing some firms as upper tier is useful, the spectrum of informal economy firms is large and quite fluid, so any classification must be used with care.

The dominance of micro-firms and the lack of firms with significant revenue growth does not mean that innovation is not taking place in the informal economy. While individual firms in specific informal sectors may be small, they are part of a broader, highly dynamic cluster or network of entrepreneurial firms with overall medium- to large-scale operations. A number of entities harbor the potential for innovative activities, as a strong entrepreneurial dynamism is present despite low capital stocks.

Education, Training and Knowledge Spillover

Micro-entrepreneurs generally tend to acquire knowledge and skills on the job in the form of “learning-by-doing,” “learning-by-training” and through apprenticeships in formal or informal workshops. The customary view is that learning and innovation in the informal economy are often based on apprenticeships where senior artisans train younger ones. A significant, often anthropologic, literature has been devoted to the study of these apprenticeships and the passing of knowledge (King Reference King1974; Charmes Reference Charmes1980).

This model of learning and skills diffusion via apprenticeships is still operational today (Kinyanjui Reference Kinyanjui and Zeng2008). For example, a study of automotive artisans in Uganda as part of the Open AIR project shows that senior artisans help relatives or friends out of generosity; in return young artisans who are eager to learn provide cheap labor (Kawooya Reference Kawooya, de Beer, Armstrong, Oguamanam and Schonwetter2014). Once they master particular skills, the senior artisans assign them to specific tasks. When their training is completed, junior artisans often leave and perform similar tasks in close geographical proximity, raising important issues of how know-how and innovations are appropriated by the original inventor. Junior apprentices acquire know-how in the course of apprenticeship and then go on to improve processes. At times, an apprentice has been reported to “steal” the master’s secrets (Charmes Reference Charmes1980). When that is done, he or she is ready to go and establish his or her own enterprise.

But skills in the informal economy are not derived solely from such types of apprenticeship. First, the dense relationships in innovation clusters lead to an efficient diffusion of knowledge and know-how. The study of the creation of Kashmiri Pashmina Shawls in India shows how the passing on of skills in close-knit inter-organizational networks helps share knowledge and innovation (Sheikh Reference Sheikh2014).

Increasingly, informal sector firms show an openness to codified forms of knowledge. In addition to the approaches described above, skills are acquired through earlier formal education (Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae Reference Kraemer-Mbula, Wamae, Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae2010a). Trial and error, assisted by books, manuals and the Internet, and knowledge spillovers gained by importing and selling equipment are also sources of advanced skills (ILO 1992). At higher stages of development, a combination of some formal education, specific vocational training and work experience can be an important source of innovative capacity among micro-enterprises in the informal sector (Kabecha Reference Kabecha1998).

Moreover, supply-and-demand interactions play an important role shaping learning and innovation processes in informal enterprises. Studies suggest, for instance, that informal sector blacksmiths – who are often farmers as well – better understand demand preferences in the informal economy and are able to use local knowledge to produce high-quality customer-tailored tools (Akbulut Reference Akbulut2009). Customers prefer their products because they are able to adapt them swiftly to changes in farming conditions. Moreover, customers, suppliers and technology transfer agencies regularly suggest technical and commercial solutions to problems. Best practices are then transferred among manufacturers (see Chapters 4 and 5).

Empirical studies have also discovered rather unusual knowledge flows between the formal and informal sectors, where formally trained designers and academic researchers sometimes draw on the expertise of artisans in the informal sector to provide local society with innovative products or services. The collaboration between informal sector automotive artisans and mechanics and formal university researchers in Uganda is characterized by what is termed a “reverse knowledge flow,” that is, the designs and production techniques of informal economy actors are being introduced to the formal research centers and universities, not the other way around (Kawooya Reference Kawooya, de Beer, Armstrong, Oguamanam and Schonwetter2014).

As in the formal sector, imported products are an important source of learning for product innovators. Import competition constitutes a supply-side stimulus, giving scope to micro-enterprises to learn and imitate. However, the relative sophistication of imported technology in relation to the sophistication of the local formal industry and the skills of local entrepreneurs reduces the potential to adapt equipment. When there exists no local formal industry, and the technology gap between imports and local production is too high, no local innovation will occur on the basis of imports, a situation referred to as “technological dualism” in the literature (Kabecha Reference Kabecha1998). There is thus a link between the availability of skills and capital upgrading in the informal sector and the nature of the local formal industry. The existence of a local capital goods industry, involved in the production of machinery and tools, creates skills that are favorably used in the informal sector as well. Countries solely importing machines from abroad were found to have entrepreneurs with less ability to improve technological capability by demonstration and learning.

Sophistication of Inventive Activity: Innovation, Imitation and Adaptation

Most empirical studies stress that entities are – despite their low capital intensity and low use of technology – highly dynamic. Innovations take place in relation to inputs, processes and outputs, allowing informal firms to adapt to new circumstances and exploit market opportunities.

Early case study work focusing on “technological capabilities” already revealed the innovative strain of micro-entrepreneurs in the informal sector (Amin Reference Amin1989; Khundker Reference Khundker1989; Ranis and Stewart Reference Ranis and Stewart1999). The informal metal manufacturing and construction sectors of developing countries were studied as examples in the 1980s (Mlinga and Wells Reference Mlinga and Wells2002).Footnote 5 In particular, in the early 1990s the ILO led extensive case study work across different regions to assess technological capability in the manufacturing sector.

In this research, the concept of innovation was relatively limited. It was often understood as the purchase and use of new machines, that is, capital accumulation to improve production processes. It was found that informal actors introduce new products or improve existing ones, that processes are made more efficient and that new tools are tested.

This earlier sector-specific work has been revived more recently with new country- and sector-specific fieldwork such as the work conducted for this book that stresses the adaptive and innovative nature of the informal sector. These more recent dedicated surveys of micro-entrepreneurs or precise sectors are based on a broader understanding of innovation as discussed above.

The new studies share some conclusions with earlier contributions to the literature. Both earlier and current research suggests that there is more adaptation and imitation than original invention in the informal economy (ILO 1992; Chapters 3–6 of this book). Most of the studies cite examples of adaptation of equipment of industrial origin rather than of any intrinsic ability to create original technological components. This type of innovation has been characterized as “quick responses to market demand and supply” (Bryceson Reference Bryceson2002; Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae Reference Kraemer-Mbula, Wamae, Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae2010b), “innovation under conditions of scarcity” (Srinivas and Sutz Reference Srinivas and Sutz2008) or “tinkering on the margins,”Footnote 6 mostly problem-solving to overcome shortcomings that often but not exclusively originate from an underperforming formal economy, for example, lack of parts or other supplies in the formal sector, and/or to adapt foreign products to local conditions. Examples abound in the area of self-construction of tools, metal manufacturing and, more generally, repair and maintenance activities.

However, little consistent evidence emanates from these studies concerning the type of innovation taking place in the informal economy. It is unclear which type of innovation – product, process, organizational or marketing innovation – is most prevalent in the informal economy, and whether innovation aims to improve product variety or product quality.

On the one hand, technological change often comes from entrepreneurs’ imitation of existing models for their own use in workshops, rather than for sale on the market, for example, self-construction of tools to improve processes (ILO 1992). The aim in such cases is to increase production volume and reduce unit costs via process innovation and new tools. This is clearly an important aspect; prices, especially relative to the formal sector, are among the most important drivers of sales (Kabecha Reference Kabecha1997).

On the other hand, studies stress that informal economy firms are more concerned with producing new products than utilizing technology because the former can result in an immediate gain (de Beer, Fu and Wunsch-Vincent Reference De Beer, Fu and Wunsch-Vincent2013). Creating new products and product diversification are also a reaction to fierce competition among producers.

Among the few available studies, quality has been found to influence consumers in the informal sector; it is associated not only with durability (Kabecha Reference Kabecha1997) but also with product design and packaging.

Business owners of informal metal manufacture firms in Kenya have been found to focus on quality and style to differentiate their products (see Chapter 3). This indicates that informal firms see value in improving on and competing over the quality of the final product. The informal sofa-makers of Gikomba in Nairobi adopt new coordination modes, experimenting quickly and constantly to produce a large number of new designs and develop new models, about 1,500 sofa frames per week. Similarly, Chapter 4 reports that quite a few South African informal manufacturers of home and personal care products (40 percent of respondents) regard quality as an important feature of their products and perceive their goods to be of higher quality than those of their immediate competitors operating nearby. The case study of traditional medicine in the informal sector in Chapter 5 also finds quality driving innovation in the various components of the value chain. In the production process, adherence to quality assurance practices enables the traditional medicine products to pass regulatory tests. Even going to market, the quality of packaging differentiates products from competitors.

In general, issues relating to technology and capital affect the scale at which innovation-related production and trade occur in the informal economy. Even studies that tend to be optimistic about the level and scope of innovation in the informal sector, such as Daniels (Reference Daniels2010), see “scalability” as an important problem. As the Oslo Manual notes, “[T]he sometimes great creativity invested in solving problems in the informal economy does not lead to systematic application and thus tends to result in isolated actions which neither increase capabilities nor help establish an innovation-based development path” (OECD/Eurostat 2005, p. 137). The informal sector’s challenge, to be more precise, is not with innovation itself, but rather with its scalable application.

Technology, Capital and Capability

Many micro-firms in the informal economy demonstrate low capital intensity and limited skills, using simple technologies and facing limitations to technical upgrading. A central problem is the lack of access to techniques and technology and the lack of resources to develop processes and improve machinery. Because of irregular cash flow, time away from production to develop machinery, for instance, is in very short supply. While large producers often have a selection of technology packages to choose from, small entrepreneurs rarely have access to technology to meet their needs.

Instead, informal enterprises often innovate, crafting affordable versions of expensive equipment by reassembling surplus components and at the same time overcoming scarcity and other material constraints. For instance, as reported in Chapter 3, informal metalworkers in Nairobi produce commodity goods such as potato chip cutters using very basic tools and materials but, alas, often with inadequate protective equipment, for example, using cardboard face shields to protect workers. Informal enterprises in the home and personal care sector in South Africa reproduce electric mixers using a secondhand electrical drill and other material found in a scrap yard (see Chapter 4). By doing so, they considerably reduce the cost of machinery. While incremental in nature, these initiatives have significant implications for informal firms, which are able to enlarge their scale of business and change their business models. At the same time, access to more sophisticated techniques and technology remains elusive.

Furthermore, the skills acquired through traditional types of activities can impose a constraint on the acquisition of new techniques requiring education and training (Aftab and Rahim Reference Aftab and Rahim1986, Reference Aftab and Rahim1989; Aftab Reference Aftab2012).

Organization of Activities in Clusters and Linkages to the Formal Sector

Few studies are available on linkages between the formal and informal sectors, the clustering of informal sector activities and the impact of such arrangements.

Existing studies do, however, reveal that instead of individuals, communities can best be regarded as the main agents of innovation (see Chapter 6). Indeed, firms in the informal economy tend to operate in clusters or “agglomerations,” including in the process of creating or applying new knowledge or generating new products or processes (Livingstone Reference Livingstone1991). This clustering of operators and strong informal networks facilitates a rapid transfer of skills and knowledge within the sector with a view to solving problems (ILO 1992; Sheikh Reference Sheikh2014). Moreover, clusters of informal operators develop reputation over time that can effectively attract potential buyers and suppliers (Chapter 3; Bull et al. Reference Bull, Daniels, Kinyanjui and Hazeltine2014).

As shown by the country studies in this book, intermediary organizations within these clusters are said to play a strong role in improving production conditions and profitability in the informal sector.

Previously, and despite operation in clusters, collective initiatives or innovation-geared activities could be considered rare. Individual initiatives by informal sector entrepreneurs with limited support from the wider institutional framework were mostly responsible for improving production conditions and the profitability of commercial activities.

Some improvement has taken place in recent years, as initiatives have sought to organize workers in the informal economy to achieve economies of scale (Kawooya and Musungu Reference Kawooya and Musungu2010; Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae Reference Kraemer-Mbula, Wamae, Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae2010a). For example, the Kamukunji Jua Kali Association, the first informal manufacturing association in Kenya, discussed in Chapter 3, acts as a meaningful intermediary organization, promoting joint production and improvement of processes and also helping to gain recognition of the cluster and government support for the artisans. Informal TMPs in Ghana also make efforts to form associations to address issues of mutual interest relating to their practice. In their associations, they can socialize with peers, more experienced practitioners and experts in order to exchange ideas and information, obtain new knowledge, and advertise and promote their products (see Chapter 5 and Essegbey et al. Reference Essegbey, Awuni, Essegbey, Akuffobea and Micah2014).

Despite their evident positive impact, not enough is known about the forward and backward linkages between informal and formal sector actors and value chains (Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae Reference Kraemer-Mbula, Wamae, Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae2010a). Backward linkages show the extent to which informal sector enterprises obtain inputs from the formal economy in the form of raw materials, technologies, intermediate products or final goods. Forward linkages show the ability of informal enterprises to supply the formal sector with intermediary or final goods, for instance, through sub-contracting. In particular, the role of formal scientific or R&D institutions in innovation activities within the informal economy is under-researched. Yet these linkages can have an important positive influence on technology diffusion and knowledge acquisition (Bhaduri and Sheikh Reference Bhaduri and Sheikh2013; de Beer, Fu and Wunsch-Vincent Reference De Beer, Fu and Wunsch-Vincent2013). Connecting with formal organizations can facilitate links with other formal structures and related opportunities for informal actors. Sometimes, too, innovation in the informal sector occurs with the help of formal sector scientific institutions. In sum, the systematic collaboration of the informal economy with the formal sector for innovation, including with formal sector institutions such as universities or public research centers, appears to be the exception, not the norm. Promoting this collaboration is also not traditionally a declared objective of government policy. These issues are discussed in more detail in Chapter 8 of this book.

Where they do take place, however, formal–informal sector interactions are bearing fruit. Recent case studies show that the networking of TMPs in Ghana with local knowledge institutions and regulatory bodies has upgraded their knowledge and stimulated innovations. Informal manufacturers in the home and personal care industry in South Africa who are able to connect with the wider innovation system are also shown to be more likely to succeed in their innovation efforts. As Kraemer-Mbula and Tau note (Reference Kraemer-Mbula and Tau2014, p. 41), “88% of manufacturers that interacted with formal organizations reported a range of benefits as a result, whilst in 12% of the cases the services provided by formal organizations did not seem to suit their needs. The benefits reported ranged from using manufacturing facilities, products manufacturing training (mostly linked to those interacting with technology transfer organizations), support with book keeping, mentorship and networking with other entrepreneurs.”

In the traditional medicine sector in Ghana, for example, researchers from the Centre for Scientific Research into Plant Medicine have facilitated innovation of traditional medical practitioners by helping to develop product-testing methods and practices. A study of the agricultural subsistence sector in the United Republic of Tanzania and its interaction with the Engineering Department of the local university suggests that technological capabilities have been improved and newly acquired – though at a basic level (Szogs and Mwantima Reference Szogs and Mwantima2009). A study in Uganda shows the cross-fertilization and utilization of innovations between formal institutions, as in universities and research centers, and informal sector entities (Kawooya Reference Kawooya, de Beer, Armstrong, Oguamanam and Schonwetter2014).

As described earlier, the formal sector also receives fresh ideas and inspiration from skillful and resourceful actors in the informal sector. Innovative informal sector actors are found to inspire their formal sector counterparts with new products or processes. In this sense, copying and learning is not a one-way street between the formal and the informal sector, but rather a dynamic, bi-directional process. One example is the informal sector automotive artisans and mechanics providing knowledge and practical inputs to formal university researchers in the aforementioned study in Uganda, helping them with the novel design and production of cars (Kawooya Reference Kawooya, de Beer, Armstrong, Oguamanam and Schonwetter2014).

Recognizing this, some more recent policy schemes aim to increase linkages within the informal sector and also between the informal sector and formal institutions and firms.

Table 2.3 synthesizes our findings about the characteristics of innovation in the informal economy based on our three case studies.

| Informal metalworking sector in Kenya | Informal manufacture of home and personal care products in South Africa | Traditional herbal medicine in Ghana | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firms and entrepreneurs |

|

|

|

| Education and training |

|

|

|

| Imitation, adaptation, and innovation |

|

|

|

| Technology, capital, and capability |

|

|

|

| Knowledge flows and collaboration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Barriers to Innovation in the Informal Sector

Despite their heterogeneity, informal sector enterprises face a number of common obstacles to innovation and upgrading.

Evidently, constraints imposed by corruption, violence, threats to health and safety and other risks may be highly relevant, although generally beyond the scope of this book. Obstacles to technological progress in the informal economy are largely determined by infrastructure, financial, educational and skills, information and other constraints.Footnote 7

In terms of infrastructure, the most important constraints are a lack of space and infrastructure to expand operations coupled with inconsistent energy supply and other factors. In terms of financial constraints, informal sector actors face capital market imperfections as lenders are risk averse and uncertain about lending to them, meaning they face pressure to achieve immediate return. In terms of educational and skills constraints, informal sector operators often have insufficient education, skills and knowledge, and classic training organizations are geared to supplying their services to formal enterprises only. At times, informal sector operators lack the ambition and skills to successfully operate and grow their business, with the focus being mainly on ensuring subsistence. Also, informal entrepreneurs often face information constraints, in that information about new products and processes, new machinery or tools, or changes in market demand does not reach them.

Institutional constraints pose severe limitations on informal economy operators. For one thing, there is often a lack of government support and policy measures aimed at stimulating and facilitating innovation in the informal economy.

Social constraints also matter greatly. Informal entrepreneurs are often obliged to share their profits with a family or extended network or to invest in informal collective social insurance schemes, often discouraging them from developing their business in the first place. Many also find themselves obliged to employ family members, sometimes counteracting efforts to have the right skills levels in place, and further diverting time and pecuniary resources from investing in more appropriate infrastructure, machinery or innovation more broadly.

It is worth noting that these characteristics of, and barriers to, innovation are not unique to the informal economy in developing countries. Formal enterprises also often operate far from optimal efficiency and have few differentiated products. Important market failures relating to economies of scale and externalities present high barriers to innovation for formally established firms too.

Conclusion

Frequently, innovation in the informal economy takes place in clusters that facilitate the flow of knowledge and technology via simple exchanges of ideas. Depending on the sector in question and the appropriation methods applied, entrepreneurs imitate and copy products from each other, from local formal and informal industries and from imported products. Labor migrates from the formal to the informal sector, and vice versa, facilitating the transfer of knowledge.

Apprenticeships and on-the-job learning are common in the informal economy and facilitate the intergenerational transmission of knowledge and technology. Apprentices with sufficient skills or resources tend to open their own operations in close proximity to their “master,” and often copy the master directly. In sectors that rely on traditional knowledge, oral transmission helps to preserve and transmit knowledge from generation to generation and within family or other social groups. A few exceptions aside, there is less evidence to show that clusters rely directly on knowledge from formal public research centers or other educational institutions. This indicates that the linkages between informal and formal public actors are underdeveloped. However, where a connection is made and interaction takes place, the benefit for informal firms is substantial.

Innovation in the informal economy exhibits the following main characteristics:

Large amounts of constraint-based innovations take place under conditions of survival, scarcity and constraints to address mostly the needs of less-affluent customers. There are, however, cases of innovative products in the informal economy that are distributed to high-income customers and overseas markets.

Innovations are rarely driven by R&D but are often driven by knowledge gained through adopting, adapting and improving available good ideas, best practices and technologies in novel and economic ways to solve customer problems.

Incremental rather than radical innovations are the main source of innovative performance. Sophisticated technologies and machinery are rarely used. Adapting imported products or those from the formal mainstream market to simple tools and material available locally is a popular conduct of innovation in the informal economy.

Innovations in the informal economy have various connections with the formal sector. Knowledge, skill, capital, people and other types of resources can sometimes flow both ways.

Innovations in the informal economy often take place in geographically concentrated regions in a collaborative manner. This way of organizing production and innovation helps entrepreneurs in the informal economy build their collective identity and product brand.

Innovations in the informal economy are not only economically viable but also socially influential as they often affect a large share of population involved in the innovation system and value chain.

The copying of ideas is rapid. Partly this is due to a lack of effort or methods to appropriate techniques, designs and final outputs. Sharing knowledge within clusters/communities is also the social norm in many cases, encouraged and supported by the local culture.

Importantly, much of the evidence garnered in this chapter relies on studies covering mainly goods-producing sectors. The focus is largely on innovation in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors. This somewhat neglects the fact that innovation also occurs in the service sectors such as construction, wholesale and retail trade, transportation, food service and other service activities.Footnote 8 Technological capabilities, the type and sophistication of innovation and relevant horizontal lessons generated with respect to firm characteristics, learning, knowledge creation and diffusion are potentially different in the service sector.

Finally, traditional knowledge practices of indigenous peoples and local communities exist, which are often discussed separately from the informal economy (see Drahos and Frankel Reference Drahos and Frankel2012; Finger and Schuler Reference Finger and Schuler2004; and the treatment in Chapter 6). Studies of these practices and communities that aim at deciphering innovation activities and impacts and the subsequent development of traditional knowledge may also need to be undertaken as part of future innovation research.