Introduction

Among the efforts to reform and complement representative democratic institutions we find the emergence and increasing adoption of deliberative mini-publics (DMPs) by governments and public authorities (OECD, 2020). These procedures fall within the broad spectrum of democratic innovations (Smith, Reference Smith2009) and are characterized by bringing together a randomly selected group of citizens – usually through ‘sortition’ – to carefully deliberate on political issues (Reuchamps et al., Reference Reuchamps, Vrydagh and Welp2023). Given the key position of political representatives in the process of adoption of democratic innovations (Thompson, Reference Thompson, Elstub and Escobar2019), existing research has attempted to enhance our understanding of their views and attitudes towards them. This literature has revealed an interest in broadening current forms of citizen participation in public decision-making (e.g. Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2006; Caluwaerts et al., Reference Caluwaerts2020; Radzik-Maruszak et al., Reference Radzik-Maruszak, Haveri and Pawłowska2020), although the stances of political elites tend to be much more cautious than those of the general population (Koskimaa and Rapeli, Reference Koskimaa and Rapeli2020; Garry et al., Reference Garry2022; Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Niessen and Reuchamps2022). Political representatives also seem to be not equally enthusiastic about all types of democratic innovations. Interestingly, DMPs seem to garner more support among them than other procedures such as referendums (Núñez et al., Reference Núñez, Close and Bedock2016; Close, Reference Close2020; Gherghina et al., Reference Gherghina, Close and Carman2023; Wauters et al., Reference Wauters2025).

Despite the previous evidence on the apparent greater predisposition of political representatives towards DMPs, we have very limited understanding of how this favourability is affected by the institutional design of these procedures. More importantly, we likewise do not know how these preferences influence political representatives’ willingness to adopt a mini-public. Previous research has focused on the binding/non-binding character of such procedures, pointing out a preference for the latter and underscoring politicians’ reluctance to share the decision-making power with citizens (Rangoni et al., Reference Rangoni, Bedock and Talukder2021; Garry et al., Reference Garry2022; Reuchamps and Sautter, Reference Reuchamps and Sautter2022; Goutry et al., Reference Goutry2024; Koskimaa et al., Reference Koskimaa, Rapeli and Himmelroos2024). However, other studies have emphasized the relevance of considering additional dimensions of participation in analysing this topic (Hendriks and Lees-Marshment, Reference Hendriks and Lees-Marshment2019; Klausen et al., Reference Klausen, Vabo and Winsvold2023), suggesting that politicians’ favourability is a more nuanced and multifaceted issue. Due to the high institutional diversity of DMPs (Smith and Setälä, Reference Smith, Setälä and Bächtiger2018), it seems relevant to dig into the different effects that these design decisions may have on politicians’ attitudes. This paper aims at bridging this literature gap by addressing the following research question: how the institutional design of DMPs affects the willingness of political representatives to adopt these procedures? The novelty of this paper lies in the inclusion in our analysis of several design features still unexplored by this literature strand, providing a complex scenario under which to further examine political elites’ attitudes towards DMPs. Enhancing our knowledge of this aspect is key for a better understanding of the process of adoption of the ‘deliberative wave’ (OECD, 2020), its characteristics and the part played by political representatives in it.

For this purpose, we analyse the results of a conjoint experiment devised to assess the influence of different design features of a potential DMP on the decision of political representatives whether to fund its adoption both at local and EU levels. This experimental approach is quite novel to the study of the attitudes towards democratic innovations, as it has only been used previously in the strand of research on citizens’ preferences (e.g. Christensen, Reference Christensen2019; Goldberg and Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2022; Pow, Reference Pow2023), but not yet for analysing those of political elites. Our conjoint experiment involved 716 representatives from different administrative levels in five European countries: France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Poland. The results show that the binding/non-binding character of DMPs is not the most central element to politicians’ decisions; they prefer to be part of the assembly and to deliberate both with ordinary citizens and the organized civil society. Some interesting nuances emerge between procedures chosen at the local and European levels, suggesting that politicians are aware of the challenges associated with the scaling up of DMPs.

The paper is structured as follows: first, we review the previous literature on politicians’ attitudes towards mini-publics and articulate the hypotheses under examination. Then, we present the methods used, providing details on data collection and the experimental set-up of the conjoint analysis. The following section presents the results of the experiment and scrutinizes the hypotheses. Finally, our key findings are highlighted and discussed, as well as their broader implications for both the literature on political elites and the literature on democratic innovations – specifically for mini-publics’ scholarship.

Theoretical framework

Politicians’ attitudes towards mini-publics

Deliberative procedures are in the spotlight of scholarship on democratic innovations (Curato et al., Reference Curato, Vrydagh and Bächtiger2020), which has shown interest in attitudes and perceptions towards these procedures in recent years. Work on politicians’ attitudes has revealed a favourable disposition towards the use of DMPs (Rangoni et al., Reference Rangoni, Bedock and Talukder2021; Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Niessen and Reuchamps2022), which would help to explain its growing diffusion. When preferences for these procedures have been compared to preferences for other democratic innovations, the greater receptiveness of politicians to mini-publics has been evident (Núñez et al., Reference Núñez, Close and Bedock2016; Close, Reference Close2020; Gherghina et al., Reference Gherghina, Close and Carman2023; Wauters et al., Reference Wauters2025). But we know little more about politicians’ preferences for these procedures. In much of the research on the subject, when political elites are asked about DMPs – or, more broadly, democratic innovations – these are presented to them in a narrowly defined way. Aware of the diversity in terms of institutional design of DMPs (Smith and Setälä, Reference Smith, Setälä and Bächtiger2018), it seems reasonable to wonder whether political representatives would have the same attitude towards deliberative procedures with different design features.

In fact, we already have some evidence pointing to different attitudes towards mini-publics with different characteristics. Most of this evidence comes from the literature on citizens’ attitudes and shows the relevance of some design features such as the presence of politicians in the assembly or its face-to-face nature, among others (e.g. Christensen, Reference Christensen2019; Goldberg and Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2022; Pow, Reference Pow2023). While supporting our argument, such evidence does not allow for a direct translation to the case of political representatives – because of differences in the perceptions of politicians and citizens towards democratic innovations (Koskimaa and Rapeli, Reference Koskimaa and Rapeli2020; Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Niessen and Reuchamps2022). Only a few studies have focused on elite perceptions regarding DMPs with different design features; these have exclusively addressed their binding/non-binding character, showing politicians’ greater support for the latter (Rangoni et al., Reference Rangoni, Bedock and Talukder2021; Garry et al., Reference Garry2022; Reuchamps and Sautter, Reference Reuchamps and Sautter2022; Goutry et al., Reference Goutry2024; Koskimaa et al., Reference Koskimaa, Rapeli and Himmelroos2024). These results, coupled with their greater preference for DMPs compared to referendums, have been read along the lines of politicians’ aversion to sharing decision-making power with citizens. But we know that the diversity of DMPs is not limited to their binding or non-binding capacity; other design features such as the presence or not of politicians in the deliberations (e.g. Farrell et al., Reference Farrell2020) or the role of citizens in agenda setting (e.g. Bua, Reference Bua2012) are part of their institutional ‘menu’ and are also at the core of the academic discussion in this regard (see Böker and Elstub, Reference Böker and Elstub2015). As in the case of citizens, mini-publics with different characteristics might be perceived differently by political representatives, although we do not yet know how.

Which features do they prefer and why?

As a way of examining the different features of democratic innovations, Archon Fung (Reference Fung2006) proposed the ‘Democracy Cube’, identifying three relevant dimensions we address here: who participates, how debates are linked to political decision-making, and how participants communicate to each other. This scheme is particularly useful for analysing the design features to be considered in this paper, as well as for elaborating on their likely influence in the willingness of political representatives to adopt a deliberative procedure.

The first dimension relates to a central concern in the debate on mini-publics: who participates – or ‘inclusiveness’ using Smith’s (Reference Smith2009) terms. Research on politicians’ attitudes gives us few clues about how they relate to this dimension. However, the literature strand on citizens’ preferences provides some useful hints to start with. These studies have shown disparate results regarding the relevance of ‘inclusiveness’ using different variables to measure it: a negligible weight on attitudes if we consider the selection method to generate the body of members of the assembly (sortition vs. election) (Pow, Reference Pow2023)Footnote 1 or the degree of openness of the membership itself (open to all/selected group/only key stakeholders) (Christensen, Reference Christensen2019); instead, if the number of participants is considered, a strong preference for bigger procedures is found among citizens (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2021; Goldberg and Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2022).

Given the complexity of this dimension, we consider it important to explore it further for the case of political representatives. There are good reasons to think that politicians – like citizens – will prefer larger procedures, even if their adoption is financially costlier than that of smaller ones (cf. Beswick and Elstub, Reference Beswick and Elstub2019). Deliberative procedures aim to enrich the democratic and deliberative credentials of policy proposals, but often at the cost of replacing the mass institutions of representative democracy – that is, parties, elections, and legislatures – by small-scale publics (Chambers, Reference Chambers2012), something that has been critically debated in terms of the democratic legitimacy of their outputs (e.g. Lafont, Reference Lafont2015). Larger procedures would help to build their external political legitimacy – by enhancing the media and political salience of the events (Goodin and Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006) – and to increase citizens’ trust on governance institutions and processes (LeDuc, Reference LeDuc2015). Hence, we posit that:

Hypothesis 1a: Political representatives will prefer larger deliberative procedures over smaller ones.

Moving further into this dimension, Hendriks and Lees-Marshment (Reference Hendriks and Lees-Marshment2019) have pointed out that, for political representatives, one of the values of democratic innovations lies precisely in their capacity to provide them with knowledge of citizens’ personal experiences and opinions of which they are unaware – approaching them to the ‘silent majority’ (see also Junius et al., Reference Junius2020). This, of course, not only incentivizes their preference for larger – where more voices can be included – but also more representative procedures (see also Beswick and Elstub, Reference Beswick and Elstub2019; Niessen, Reference Niessen2019); a deliberating group that is unrepresentative of society may not be desirable from the point of view of the political elite (Pálsdóttir et al., Reference Pálsdóttir, Gherghina and Tap2023) and, at the same time, it may not be desirable for building the external political legitimacy of the procedure (Bekkers and Edwards, Reference Bekkers, Edwards, Bekkers, Dijkstra and Fenger2007; cf. Jacobs and Kaufmann, Reference Jacobs and Kaufmann2021). Additionally, these events would allow representatives to get closer to ordinary citizens, who can contribute with arguments, ideas, and problems that complement those raised by civil society in other spaces designed for this purpose (Hirst, Reference Hirst2002), transcending the classic dynamics of associative democracy (Cohen and Rogers, Reference Cohen and Rogers1992). We therefore propose:

Hypothesis 1b: Political representatives will prefer those deliberative procedures whose participants are representative of the broad public opinion.

Hypothesis 1c: Political representatives will prefer those deliberative procedures where only citizens take part.

Beyond these aspects, there is an additional tension linked to the composition of deliberative procedures: whether politicians should be involved as members of the assembly (i.e. Irish Constitutional Convention in 2012). This element not only appeals to ‘inclusiveness’ but is also connected to the second dimension referred to above – how debates are connected to decision-making, or ‘popular control’ (Smith, Reference Smith2009). Previous work has argued theoretically for the inclusion of representatives as a way of overcoming their rejection to these procedures and to connect the conclusions and recommendations of deliberation to political decision-making (e.g. Setälä, Reference Setälä2017). Some deliberative procedures have already used this formula, reporting some benefits for their functioning and the general acceptance of the use of these procedures by representatives involved (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell2020; Grönlund et al., Reference Grönlund2022; see also Niessen, Reference Niessen2019). Furthermore, substantial evidence suggests that citizens prefer deliberative procedures that include politicians (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2021; Goldberg and Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2022; Pow, Reference Pow2023). Citizens do not seek to replace politicians’ representative role with empowered and autonomous DMPs, but rather to establish them as a complementary institution (Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Lindell and Bächtiger2025). This also suggests that perhaps politicians’ presence might help the perceived external legitimacy of the mini-public – which, in turn, might be of interest for politicians, in line with our previous hypotheses. Thus, it seems reasonable to suggest that:

Hypothesis 2: Political representatives will prefer those deliberative procedures where they can take part as members.

Concerning those features that appeal most directly to ‘popular control’, we consider here two important features that have prompted debate on mini-publics’ scholarship. The first of these, who makes the decision on the issue to be addressed by the assembly. Previous work has shown that decisions over the specificities of the deliberation topic tend to be top-down (OECD, 2020), with very little room for manoeuvre for participants. It might be thought that, for politicians, retaining control over the issue to be discussed is relevant, reinforcing the idea of their aversion to sharing decision-making with citizens (Bua, Reference Bua2012; Koskimaa et al., Reference Koskimaa, Rapeli and Himmelroos2024). The highly complex nature of the agenda-setting process itself (Pfeffer, Reference Pfeffer2024) and the potential consequences for the deliberative process of decisions made at this point (Barisione, Reference Barisione2012) may encourage their interest in retaining control over this element of the design. Furthermore, previous qualitative work has highlighted that politicians think that mini-publics would only be suitable for some topics (Beswick and Elstub, Reference Beswick and Elstub2019; see also Koskimaa and Rapeli, Reference Koskimaa and Rapeli2020), which increases incentives to retain control over this aspect. However, some authors have warned that mini-publics run the risk of becoming ‘market-tests’, since political elites can also use them to check whether their pre-decided ideas/proposals are well received among citizens or how best to ‘sell’ them afterwards (Goodin and Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006; see also Courant, Reference Courant2022). This interest in ‘testing’ ideas with citizens – which has been revealed by some previous qualitative research (Beswick and Elstub, Reference Beswick and Elstub2019; Hendriks and Lees-Marshment, Reference Hendriks and Lees-Marshment2019) – might incentivize political representatives to prefer procedures that deal with issues that are central to their political agenda. Along these lines, we argue that:

Hypothesis 3a: Political representatives will prefer those deliberative procedures where they can decide the issue to be deliberated.

Hypothesis 3b: Political representatives will prefer those deliberative procedures that tackle issues central to their political programme.

The second feature related to the ‘popular control’ refers to the binding or non-binding nature of the conclusions and recommendations reached through deliberation. This idea is at the heart of those explanations that suggest that mini-publics are attractive to political elites because they (usually) have less decisive power than other democratic innovations. As indicated above, the few previous studies on the relevance of the institutional design of these procedures focus on their binding character, showing the strongest support among politicians for those of a non-binding nature (Rangoni et al., Reference Rangoni, Bedock and Talukder2021; Garry et al., Reference Garry2022; Reuchamps and Sautter, Reference Reuchamps and Sautter2022; Goutry et al., Reference Goutry2024; Koskimaa et al., Reference Koskimaa, Rapeli and Himmelroos2024). That is, however, surprisingly in line with the preferences of citizens (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2021; Goldberg and Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2022) or assembly participants (Fernández-Martínez and Bates, Reference Fernández-Martínez and Bates2023), who also prefer consultative rather than binding procedures. Hence, we posit that:

Hypothesis 3c : Political representatives will prefer consultative deliberative procedures rather than binding ones.

The last dimension we address in this paper concerns the way in which participants communicate during the process. In addressing here the specific case of DMPs, we consider this dimension to be intrinsic to the procedure at hand: deliberation (Fung, Reference Fung2006; Reuchamps et al., Reference Reuchamps, Vrydagh and Welp2023). However, we have considered the way in which deliberation takes place. An online deliberative procedure, or even a mixed one, could foster the inclusion of some individuals due to the removal of physical and psychological barriers (Itten and Mouter, Reference Itten and Mouter2022). At the same time, digital divides remain (Norris, Reference Norris2001), reinforcing other participation biases. In fact, previous work with citizens has shown a clear preference for in-person procedures (Christensen, Reference Christensen2019; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2021; Goldberg and Bächtiger, Reference Goldberg and Bächtiger2022). Thus, we propose that:

Hypothesis 4: Political representatives will prefer in-person deliberative procedures compared to online ones.

To this conceptual approach we must add a further layer: that of the scaling up of these procedures. The ‘transferability’ of a democratic innovation is crucially affected by the administrative level at which it is implemented, meaning that the same procedure implemented at different levels has different magnitude, complexity, and requirements (Smith, Reference Smith2009). In this paper we consider DMPs at two different administrative levels: local and transnational (EU level). Despite the extensive debate on the scaling up of democratic innovations (e.g. Pogrebinschi, Reference Pogrebinschi2013; Bua, Reference Bua2017; see also Rountree et al., Reference Rountree2022), which points to the necessity of attending to the challenges associated to their institutional design, there is not as much empirical evidence available to compare politicians’ perceptions of procedures implemented at different administrative levels. Most of the literature referenced here has dealt with elite perception regarding local procedures or, as in many cases, democratic innovations abstractly. Our paper thus provides the first insights on this issue by drawing on an experimental design specifically designed to capture attitudinal differences between administrative levels among representatives.

Data, variables, and methods

To test these hypotheses, we have used a conjoint experiment that was embedded in a web survey targeting elected representatives at the local, regional, and national levels in five European Union (EU) countries, namely France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Poland (Font et al., Reference Font2024). The survey was part of a broader EU funded project, EUComMeet.

The countries selected for the survey and the territorial levels included in the design of the experiment (local and European) align with the project’s practical goal.Footnote 2 The cases were selected based on two main criteria. Firstly, the selection ensures in-depth involvement in a diverse set of countries characterized by varying political and social conditions and differing levels of experience in deliberative practices. This diversity includes countries with extensive experience in DMPs, such as Ireland, and those where such practices are emerging, like Poland and Italy. Secondly, the project aims to scale up participatory experiences, beginning at the local level and extending to the EU level. These administrative levels also provide two contrasting cases in terms of the proximity of politics to citizens. This approach recognizes the different stages of development in deliberative practices across these countries, facilitating a comprehensive understanding of how participatory procedures can be effectively implemented and scaled within the European context.

The survey was carried out between January and April 2023 using IdSurvey software. Postal letters and formal emails officially presenting both the EUComMeet project, and the survey were sent in advance to the top political authorities of the chambers, as well as to the political group leaders. After that initial contact, invitations to participate in the survey and four additional reminders were sent in February and March. A total of 1,346 out of 13,882 contacts started the interview. Of these, 712 completed the questionnaire entirely and 286 did so partially. The overall response rate including partial interviews (AAPOR RR2) is of 7% and 5% when we count complete interviews exclusively (AAPOR RR1).

Due to variations in response patterns, the sample distribution deviates from the population across several characteristics. France is underrepresented, while Germany is overrepresented, with minor deviations in the remaining countries (Ireland, Italy, and Poland). The sample also overrepresents local council representatives and underrepresents both national and regional representatives. Additionally, female representatives and left-leaning parties are overrepresented. To assess the impact of these deviations, we conducted conditional McFadden’s logit choice models, including these characteristics as control variables (StataCorp, 2023). Our analysis revealed that none of these factors significantly predicted choice, suggesting that the deviations in the sample do not systematically bias the observed preferences.Footnote 3 Given this fact as well as the small deviations in political party representation, all analyses were carried out without weighting. A thorough analysis of sampling issues, including a detailed breakdown of sample characteristics and the results of the conditional logit choice models, is provided in Section 2 of the online Supplementary Materials.

The experimental design drew inspiration from prior conjoint experiments that investigated the impact of various design features on citizens’ assessments of democratic innovations (particularly from Christensen, Reference Christensen2019). The construction of both the list of attributes and their corresponding levels was guided by this previous evidence and qualified with the available knowledge about political representatives’ attitudes towards DMPs. We used a choice-based conjoint design in which respondents were presented with three tables, each displaying two distinct deliberative event designs based on various attribute combinations. Consequently, for every pair of events, participants were tasked with selecting their preferred design for adoption at both local and EU levels (see Section 1 in the Supplementary Materials for the exact question wording used in the experiment).

The experiment followed a full randomization design of attribute levels, ensuring equal probabilities without any restrictions on attribute combinations (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Druckman and Green2019). The presentation order of attributes was randomized at the respondent level, maintaining this randomly generated sequence consistently across the three tasks. This order consistency aimed to streamline the experimental process and reduce cognitive load for participants (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014; Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Druckman and Green2019).Footnote 4 Table 1 details the comprehensive list of attributes and levels employed in the experiment.Footnote 5

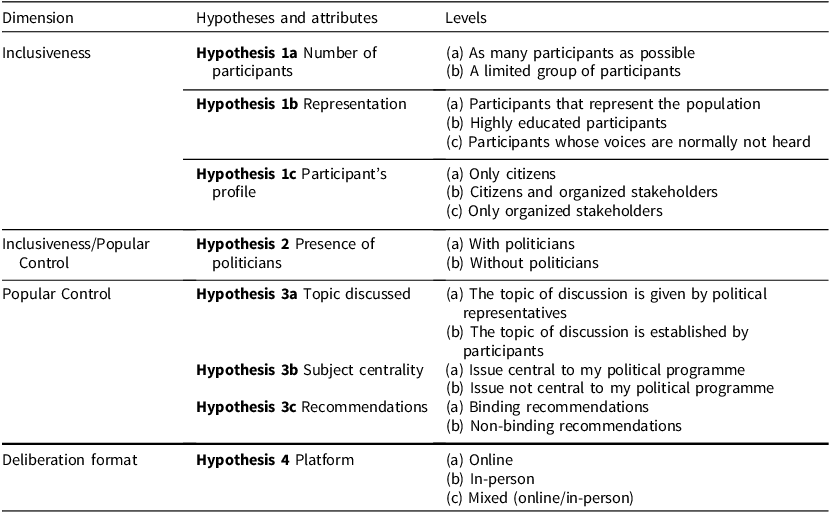

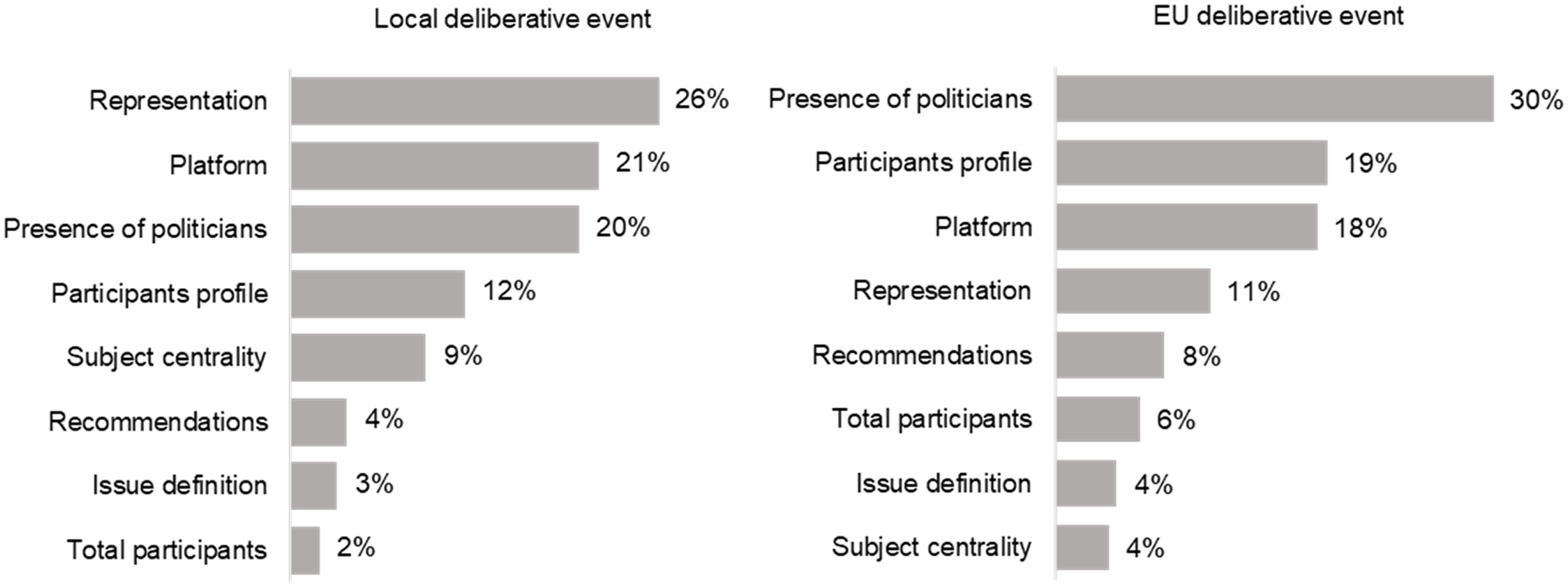

Table 1. Attributes and levels used in the conjoint experiment

A total of 716 respondents took part in the experiment, making three choices among pairs of events. Consequently, the cases considered in the analysis – the evaluated event designs – amount to a potential 4,296 choices. After accounting for non-responses, there remained 4,058 choices at the municipal level and 4,052 at the EU level for analysis. We used STATA’s Conjoint module (Frith, Reference Frith2021) to analyse our experiment’s outcomes. This module facilitates the computation of estimators proposed by Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014), namely the Average Marginal Component Effect (AMCE), and the more recent Marginal Means (MM) suggested by Leeper et al. (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020). AMCEs are calculated using one attribute level as a reference point, which can make it challenging to directly discern its effect, especially for attributes with more than two levels. Conversely, Marginal Means (MM), as recommended by Leeper et al. (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020), provide the average outcome value for all attribute levels. We have computed and visually represented both estimators, AMCEs and MMs, but find the latter to be more easily interpretable. We present the outcomes of our experiment using MM in the next section and include the AMCEs in the Supplementary Materials for reference (see Section 3).

We also used STATA to model the discrete choice data from our conjoint experiment in two ways. Firstly, to assess the influence of specific sample characteristics on the experimental outcome – as explained above (see Tables A2.4 and A2.5 in the Supplementary Materials). Additionally, we computed conditional choice models to determine the relative importance of each attribute in influencing the probability of choosing one scenario over another. The Relative Attribute Importance, derived from the beta coefficients obtained through conditional regression, is defined as the difference between the most and least preferred attribute levels relative to the sum of ranges across all attributes (Eggers et al., Reference Eggers, Homburg, Klarmann and Vomberg2022; Hauber et al., Reference Hauber2016). This measure allows us to rank the experimental attributes based on their influence on choice preferences and to compare the differences between choices made for local and EU events (see Section 3 in the Supplementary Materials for further details on its calculation).

Results

Here, we present our findings of the influence of different design features on the likelihood of DMPs events being chosen by political representatives for adoption at both the local and EU levels. The MMs presented in Figure 1 below describe politicians’ preferences towards procedures that have a particular attribute level, ignoring all other attributes (Leeper et al., Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020).

Figure 1. Probability of selection of a DMP to be conducted at the local and EU levels conditional on different design features (Marginal Means).

Our experiment focused on three key aspects concerning the ‘inclusiveness’ of mini-publics: the total number of participants – as many as possible vs. a limited number – and the diverse profiles these participants embody. We assessed participant characteristics through two distinct lenses: their representativeness, either reflective of the broader population or leaning towards groups with specific attributes, such as a higher education level or minority representation, and their classification as citizens alone or encompassing civil society stakeholders. Contrary to our expectations (Hypothesis 1a), the number of participants does not significantly affect elected representatives’ choice between mini-publics’ designs. However, participant characteristics significantly impact the selection of DMPs, both at the local and EU levels. Politicians prefer designs where participants represent the general population, followed by those focusing on minority groups often excluded from political decision-making – although both are only significant at the local level. The participation of individuals with a higher level of education reduces the likelihood of the event being carried out at the local level by more than ten percentage points and by four percentage points at the European level.

These results partially support our hypothesis that they would prefer procedures whose participants are representative of the broad public opinion (Hypothesis 1b). Representatives refrain from taking sides and exhibit a preference for events that include both individual citizens and civil society organizations, which goes against Hypothesis 1c. This model is favoured in DMPs to be held at both local and European levels. It is worth noting that events exclusively targeting civil society organizations significantly diminish the likelihood of being selected, particularly in local deliberative procedures where the probability of selection drops by eight percentage points.

Our data strongly support our hypothesis that politicians prefer DMPs in which they are involved as members of the assembly (Hypothesis 2). The likelihood of a political representative opting for a mini-public design that incorporates politicians in the process is more than ten percentage points higher compared to designs where politicians are not involved. Furthermore, this effect’s magnitude remains consistent for events adopted at both local and EU levels.

A third set of attributes includes those related to the degree of citizen control over the procedure. In the experiment, we included three attributes to address this dimension. Two of them relate to the topic of deliberation: whether it is determined by the promoting administration or the participants themselves and the degree of centrality of this issue on the politician’s agenda. The third attribute relates to the level of influence over the outcomes of the deliberation, distinguishing between recommendations being either binding or non-binding. The results do not align entirely with our hypotheses in this dimension. Only the prominence of the discussed topic on the political agenda of the representative (Hypothesis 3b) does significantly raise the probability – by over four percentage points – of the DMP taking place at the local level, which goes along with our expectation. However, whether the topic is selected by them (Hypothesis 3a), and the level of influence over the outcomes (Hypothesis 3c) have not proved significant in explaining representatives’ choices.

The last attribute evaluated in the experiment pertains to the format in which deliberation occurs – whether in-person, online, or mixed. The results support our hypothesis that politicians would prefer face-to-face interaction (Hypothesis 4).

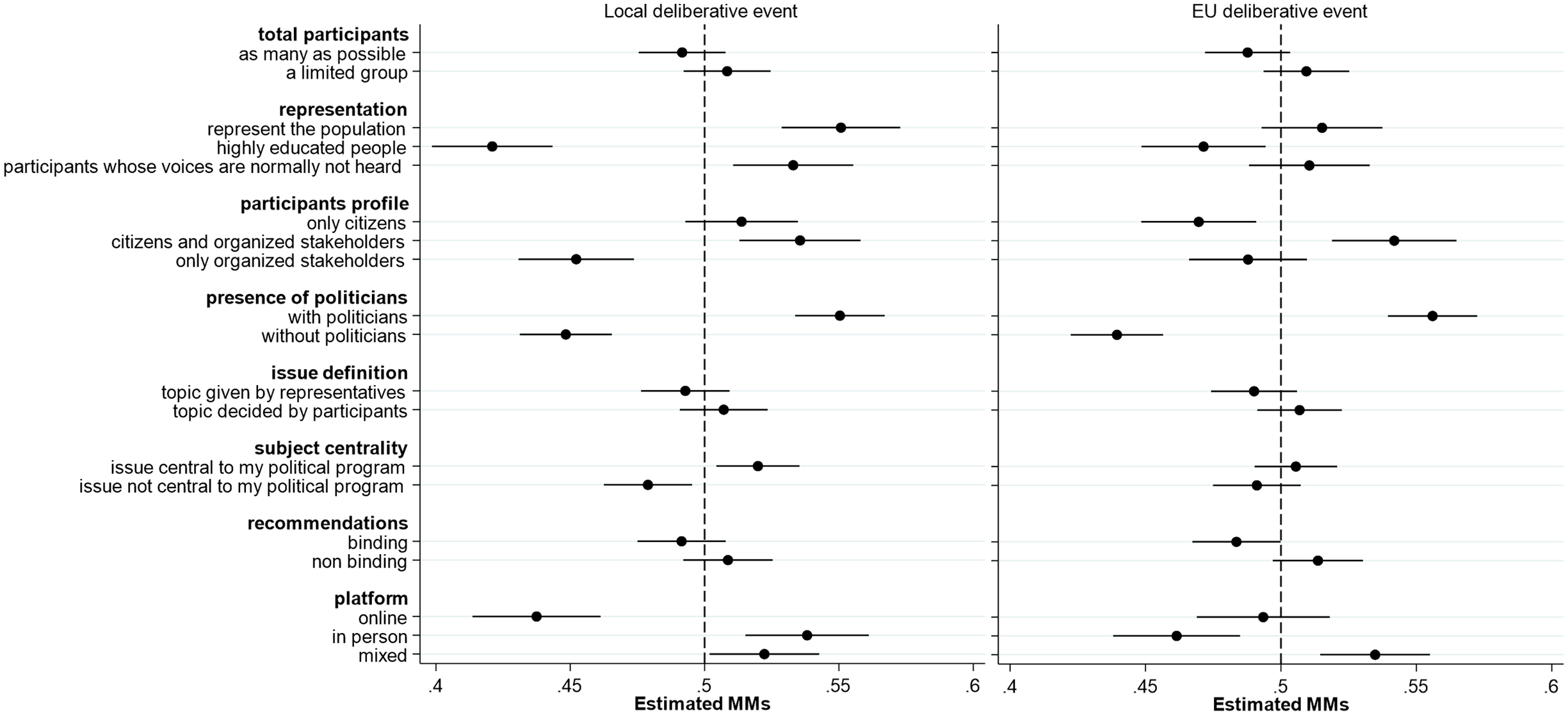

We complement this evidence with results on the relative importance of these different attributes in the choice politicians make among deliberative events. Figure 2 shows how each attribute influences the probability of choosing one scenario over another – regardless of attribute levels (Eggers et al., Reference Eggers, Homburg, Klarmann and Vomberg2022: 25). The results highlight the relevance of the representativeness of the participants and their profile at both local and European levels. Likewise, the presence of politicians as members of the assembly is important to their choice. Elements linked to ‘inclusiveness’ thus show a significant weight at both levels, making a key contribution to the choice that politicians make of some events over others. In contrast, the elements linked to ‘popular control’ appear at the bottom of the table, making a much smaller contribution.

Figure 2. Relative attribute importance in the selection of a DMP to be conducted at the local and EU levels.

Up to this point we have not referred to the differences in politicians’ preferences according to the administrative level, but in Figure 1 we appreciate them. Regarding ‘inclusiveness’, the variable in which we observed the greatest changes is the profile of the participants: holding the mini-public exclusively with citizens – excluding relevant associations and other interest groups – reduces the probability of it being held at the EU level, a trend not seen in local events. Particularly noteworthy is the shift observed in representatives’ preferences regarding deliberative procedures where only organized stakeholders participate; this factor incurs significant penalties in local but not in EU events. As for the variable regarding the representativeness of participants, only the participants’ high level of education affects the likelihood of DMP selection, though its effect is less pronounced at the EU level compared to local events.

Concerning the ‘popular control’ dimension, the influence of the centrality of deliberation topics on politicians’ agenda diminishes significantly for events organized at European scale. Conversely, the fact that recommendations from the procedure are binding significantly reduces the likelihood of the event being chosen at the EU level, while this doesn’t affect the probability of selection for local events. Lastly, we note that in local level events in-person deliberation is preferred, and the online option significantly reduces the likelihood of mini-public selection – by slightly over ten percentage points. On the contrary, for procedures conducted at the European level, the in-person option penalizes the likelihood of selection for adoption, being mixed deliberation, the format preferred by politicians.

This picture is completed and reinforced by the differences between administrative levels observed in Figure 2. Although the two variables related to ‘inclusiveness’ are still among the top four at both levels, we see that the profile of the participants has much more weight in the choice of the European event than the local one; the reverse is true for representativeness. The presence of politicians is shown to be the most relevant at the European level, increasing its relevance with respect to the local level. Finally, the variables related to ‘popular control’ appear at both administrative levels as the least relevant, but we see that the relevance of the binding nature of decisions increases slightly at the European level.

While our analysis has focused on the overall preferences of political representatives, it is important to recognize that this group is not homogeneous. To explore potential heterogeneity in preferences, we further analysed whether key factors – such as previous experience with DMPs, political role (government/opposition), seniority, ideological self-placement, and trust in people – influenced DMP design choices. We incorporated these variables as controls in our McFadden models, and we also produced subgroup difference graphs to visualize potential variations (see Tables A2.4 and A2.5 and Figures A5.1 to A5.4 in the Supplementary Materials). The results indicate that only ideological self-placement significantly affects preferences. Subgroup analysis suggests that while left- and right-wing politicians tend to agree on most design features, significant differences emerge in the preferred size and composition of mini-publics (Figure A5.4 in the Supplementary Materials). Specifically, left-wing representatives prefer procedures with more participants that integrate traditionally unrepresented voices, whereas right-wing representatives prefer fewer participants with a higher level of education. Further examination of this influence requires a detailed, tailored theoretical framework and analysis, which is not possible here due to space limitations, but has been fleshed out at length in a separate piece (Pasadas-del-Amo et al., Reference Pasadas-del-Amo, Font and Ramis-Moyano2024).

Discussion and conclusions

This paper has addressed the attitudes of political representatives towards DMPs, focusing into the specificities of their preferences towards deliberative procedures with different design features. So far, we had some evidence pointing to the attractiveness of these procedures compared to other democratic innovations (mainly referendums) (Núñez et al., Reference Núñez, Close and Bedock2016; Close, Reference Close2020; Gherghina et al., Reference Gherghina, Close and Carman2023; Wauters et al., Reference Wauters2025) and to politicians’ preferences for non-binding mini-publics over binding ones (Rangoni et al., Reference Rangoni, Bedock and Talukder2021; Garry et al., Reference Garry2022; Reuchamps and Sautter, Reference Reuchamps and Sautter2022; Goutry et al., Reference Goutry2024; Koskimaa et al., Reference Koskimaa, Rapeli and Himmelroos2024); politicians’ aversion to sharing decision-making power with citizens has been the convergence point in the interpretation of all these results. Despite being one key argument to understand and interpret political elites’ attitudes towards DMPs, the way in which other design features influence their attitudes towards these procedures has been overlooked by this strand of research. The relevance of this paper lies in addressing this research gap by drawing on an innovative methodological approach that allows us, specifically, to assess the influence of various attributes of a potential DMP on the willingness of political representatives to adopt these procedures both at local and EU levels.

To this end, we conducted a conjoint experiment in five European countries. Our methodological and conceptual approach is innovative for several reasons. First, the use of an experimental design allowed us to ask politicians about DMPs in a more detailed way than previous surveys have done; these have typically presented a generic definition of those procedures, without going into the details of their institutional design (see Jacquet et al., Reference Jacquet, Niessen and Reuchamps2022: 307). Second, this strategy enables us to know not only the design preferences of representatives, but also what these preferences look like in a multi-decision context (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Druckman and Green2019); this allows us to explore how these preferences affect their willingness to adopt a DMP. Third, the comparison between mini-publics at the local and European level allowed a first approach to how these perceptions diverge between mini-publics adopted at different administrative levels; this provides very relevant information for the debate on the scaling up of these procedures, confirming that politicians are aware of the need to adapt the design features when scaling up democratic innovations (Pogrebinschi, Reference Pogrebinschi2013).

The results of the experiment also resonate with debates in the literature on deliberative procedures and help us expand the picture of representatives’ political attitudes. The attributes presented to politicians in the experiment cover three key dimensions of mini-publics design (Fung, Reference Fung2006): (1) who participates (or ‘inclusiveness’); (2) how debates are linked to political decision-making (or ‘popular control’); and (3) how participants communicate with each other. Design features related to the composition of the assembly have proven to be the most relevant in explaining representatives’ willingness to adopt a DMP, both at local and European levels. The representativeness of the participants and their profile, as well as the presence of politicians as members of the assembly have a decisive influence on their choice of one mini-public design over another. Previous qualitative research (Beswick and Elstub, Reference Beswick and Elstub2019; Hendriks and Lees-Marshment, Reference Hendriks and Lees-Marshment2019; Niessen, Reference Niessen2019) had already shown the relevance of the ‘inclusiveness’ of democratic innovations for political representatives, and our results provide further evidence of this while highlighting which design features matter most to them.

In contrast, attributes linked to participants’ control over decision-making – such as the binding character of the recommendation or who defines the issue to be deliberated – or the deliberation mode, show a much smaller contribution to the explanation of representatives’ choices. This is not to say that politicians are not interested in retaining power and control over the decision-making process (see Koskimaa et al., Reference Koskimaa, Rapeli and Himmelroos2024; Wauters et al., Reference Wauters2025), but rather that there are other design characteristics that weigh more heavily in their willingness to adopt a DMP when facing them with a more complex situation than up to now. This is a striking finding, which underscores the need to account for the multidimensionality of politicians’ attitudes and challenges the growing perception that DMPs are attractive to them because of their typically reduced binding capacity.

Considering that politicians’ attitudes towards the ‘inclusiveness’ of democratic innovations is more governance-oriented than they are towards other dimensions of design – that is, politicians are more concerned with the problem-solving capacity than with the enhancement of democratic procedures (Klausen et al., Reference Klausen, Vabo and Winsvold2023) – it is worth reflecting on these findings and suggesting some explanations for these results. Regarding the representativeness of participants, politicians’ aversion to groups composed exclusively of highly educated citizens is notable, although they do not seem unambiguously in favour of full representativeness – providing only partial support for our hypothesis in this respect. With the socio-demographic bias of participants being one of the main criticisms to democratic innovations (Smith, Reference Smith2009), one potential reason for this result could be that representatives want the group of people deliberating to be different from the ‘typical’ one. Previous qualitative work has shown that they are concerned about the lack of representativeness of participants (Pálsdóttir et al., Reference Pálsdóttir, Gherghina and Tap2023) and the systematic absence of certain social groups and minorities in these procedures (Beswick and Elstub, Reference Beswick and Elstub2019). Broadening participation beyond the ‘usual suspects’ would help them to listen to new ideas and arguments, bringing them closer to the ‘silent majority’ which they are rarely able to hear (Hendriks and Lees-Marshment, Reference Hendriks and Lees-Marshment2019; see also Junius et al., Reference Junius2020). However, as the only attribute level that clearly influences their choices is the most educated participants, an alternative interpretation suggests that political elites may prefer groups of participants with lesser presence of the ‘critical citizen’ profile, who are more attentive to political issues and better informed than the average citizen (Geissel, Reference Geissel2008). While our results provide relevant information to the debate on how politicians relate to the representativeness of the assembly, future research should deepen our understanding of the reasons why this dimension of mini-public design influences their attitudes.

Contrary to what we hypothesized in the theoretical framework about the preference for participants’ profile, representatives are more willing to adopt procedures involving both citizens and civil society stakeholders. This apparently goes against the logic seen for representativeness: apart from the fact that these organizations are already listened to in other spaces (Hirst, Reference Hirst2002), the socio-demographic characteristics of those who compose them tend to be biased towards a higher level of education (García-Espín and Lancha-Hernández, Reference García-Espín and Lancha-Hernández2025). Here, however, there seems to be a governance-oriented balance (Klausen et al., Reference Klausen, Vabo and Winsvold2023) between improving what they believe does not work in ‘conventional participation’ (Hendriks and Lees-Marshment, Reference Hendriks and Lees-Marshment2019), while keeping what they think it does. Civil society representatives are fundamental agents in most procedures of ‘conventional’ participation, helping to channel societal demands, prioritize issues and work in the field (Papadopoulos, Reference Papadopoulos, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012). Their inclusion could help lay citizens in formulating their demands and/or recommendations, especially at the EU level where connecting necessities with policies or demands might be harder for citizens. Moreover, some studies have shown that, from the point of view of external legitimacy, participatory procedures that include organized civil society are perceived as equally legitimate as procedures that only include citizens by lottery (Jacobs and Kaufmann, Reference Jacobs and Kaufmann2021).

Our results also show that the size of the participant group does not influence representatives’ willingness to adopt one mini-public design over another, suggesting that what matters most to them is who participates rather than how many participate.Footnote 6 Indeed, politicians’ presence seems to be another key factor for them in the composition of the assemblies. Nothing in the literature that has analysed their participation in DMPs suggests that this interest is motivated by influencing or manipulating by themselves the functioning or outcomes of the mini-public (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell2020; Grönlund et al., Reference Grönlund2022). Rather, this might be connected to the different implications of their participation. First, their presence might enhance the external political legitimacy of the procedure. Second, by participating, they are aware in advance of the main outcomes of the deliberative process, enabling them to anticipate any political consequences derived from it. Finally, they may be moved by a potential willingness to listen to – and understand – these ‘new’ voices included in the procedure; DMPs are procedures oriented towards the exchange of ideas and arguments, appearing as a good opportunity for politicians to get in touch with them and to fill those knowledge gaps that they cannot fill through ‘conventional’ participation (Beswick and Elstub, Reference Beswick and Elstub2019; Hendriks and Lees-Marshment, Reference Hendriks and Lees-Marshment2019). The influence of their preference for this design feature has proved to be highly relevant at both administrative levels, underlining the need to better understand how politicians conceive their role when participating in a DMP.

Beyond these attributes that have appeared as significant at both administrative levels, we also found interesting differences between the design features of events chosen at each level. Faced with the same procedure, the administrative level seems to influence the balance that representatives make of their preferences. In terms of ‘inclusiveness’, the main difference between administrative levels relates to the profile of those who participate: at the local level, procedures composed exclusively of civil society representatives are less likely to be adopted, while at the European level, mini-publics that include only civil society, although not preferred, do not significantly reduce this likelihood. As mentioned above, politicians seem to prefer a balance between citizens and organized civil society in deliberative procedures. But how to achieve this balance is clearly affected by the administrative level. They value the intermediary role of associations and their capacity to summarize, organize, and transmit social demands, and seem to value it more at the European level. Indeed, at the European level we also observe that procedures composed only of citizens reduce the likelihood that the mini-public will be chosen for adoption. In a multilateral context, where there are many interests at stake and different ‘publics’ to be served, this role is central, allowing to grease the demands, find common ground (Papadopoulos, Reference Papadopoulos, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012) and help generate a sense of representativeness of the main interests, fostering the external legitimacy of the procedure (Bekkers and Edwards, Reference Bekkers, Edwards, Bekkers, Dijkstra and Fenger2007). Disparities between levels regarding the participation of organized interests may also be grounded on the differentiated functioning of associations at each administrative level (Rek, Reference Rek and Adam2007), leading to the perception that stakeholders at the EU level are more solvent, whereas local associations might be regarded with less trust.

This interest in the role of organized civil society at the European level seems to anticipate an interest in process efficiency (Bartelson, Reference Bartelson2006; see also Rountree et al., Reference Rountree2022). In this sense, the differences observed regarding the platform used for deliberation also point in this direction. At the local level, politicians show a preference for face-to-face – or mixed – procedures, with online events reducing the likelihood of adoption; however, at the European level, face-to-face procedures reduce the likelihood of these DMPs taking place, while online events do not. Efficiency and cost concerns might be behind these results: it is easier to organize an event with citizens at the local level, but the complexity grows as the territory and administrative level scales. At the European level, politicians consider the online tools as needed, but they do not want to give up the possibility of bringing together stakeholders and citizens in the same room.

Finally, there are also differences in terms of ‘popular control’. These differences are expressed, for each administrative level, in different attributes. At the local level, elected politicians prefer those procedures whose subject matter is central to their political agenda; this is not the case at the European level. The results at the local level are in line with what other work has pointed to: DMPs appear as procedures adopted to resolve some specific issues that are important to the government at the time (Kübler et al., Reference Kübler2020). Here a central element of the debate on DMPs emerges: whether these are procedures set in motion to resolve pressing or complex issues, or whether they are nothing more than ’market-tests’ (Goodin and Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006). The fact that the attribute relating to who makes the decision on the issue to be deliberated does not appear to be influential in their choice of one mini-public design over another suggests that their interest is driven more by their perceived importance of the issues than by an interest in instrumentalizing the procedure, as some previous work has already suggested (Beswick and Elstub, Reference Beswick and Elstub2019; Koskimaa and Rapeli, Reference Koskimaa and Rapeli2020). At the European level, the centrality of the issue to their agenda is not significant. In line with what has been noted above, politicians seem to be more aware of the multilateral character of this political arena. This does not mean that at the European level this dimension is not important to them. In fact, we observe that binding procedures reduce the likelihood of adoption at the European level, which is not the case at the local level. Although the results of this work point to a lower interest than expected in the direct control of the process, this does not mean that politicians are not aware of the stakes.

This study makes a significant contribution to addressing a fundamental question in both the scholarship on DMPs and political elites. However, it is not without its limitations. Our analysis provides an overview of politicians’ attitudes. We have also assessed the influence of variables such as ideological self-placement or whether they are part of the government or the opposition on the overall picture presented here and have made available all robustness checks conducted. Still, future research must examine these elements in greater detail and in the necessary depth to achieve a comprehensive understanding. Also, while our analysis revealed no significant cross-country differences, future research with larger, country-specific samples could explore potential nuances in preferences that might be masked by the current sample size. It may also be of interest to analyse what politicians’ design preferences look like when considering other administrative levels, particularly the regional or national levels. Including in the analysis attributes that measure additional design features (or other ways of measuring those we have used) will also help strengthen the validity of our results.

Furthermore, the use of an experimental context allows examining the relationship between representatives’ preferences and willingness to adopt DMPs, providing a sound basis for further comparative work, but this needs to be confronted with the actual behaviour of politicians. The use of real-life experiments (see Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2018; Már and Gastil, Reference Már and Gastil2023) or analysis of the adoption of real-life DMPs (e.g. Ramis-Moyano et al., Reference Ramis-Moyano2025) seem more appropriate for this endeavour. Mixed-methods approaches could also be very helpful in deepening our understanding of politicians’ preferences and their underlying rationales (e.g. Niessen, Reference Niessen2019; Koskimaa et al., Reference Koskimaa, Rapeli and Himmelroos2024). That being said, the consistency of our results with previous work analysing representatives’ preferences – mostly qualitative approaches (see Beswick and Elstub, Reference Beswick and Elstub2019; Hendriks and Lees-Marshment, Reference Hendriks and Lees-Marshment2019; but see also Klausen et al., Reference Klausen, Vabo and Winsvold2023) – reinforces their relevance and the need to further expand this line of work.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773925100167.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study, along with the codebook and the code used to generate the results, will be openly available in a public repository upon acceptance of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the members of the research team for their contributions to this project. In particular, we acknowledge the Siena team for their coordination efforts, which were crucial to the execution of this research. We also appreciate the reviewers for their valuable feedback and constructive comments, which have helped improve the quality of this paper. We acknowledge the use of AI tools (Grammarly and ChatGPT) for language editing and proofreading of this manuscript. The authors are entirely responsible for the scientific content of the paper, which adheres to the journal’s authorship policy.

Previous versions of this article have been presented at ‘PSA Annual International Conference 2024’ (University of Stathclyde, Glasgow, 25–27 March), the workshop ‘Deliberation, Politics and Culture: Understanding Developments and Challenges’ (Leiden University, The Hague, 30–31 May, 2024) and the XV Congreso Español de Sociología (Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Sevilla, 26–29 June, 2024).

Funding statement

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No 959234. During the elaboration of this manuscript, Rodrigo Ramis-Moyano has been beneficiary of the University Teacher Training Program (FPU2019), funded by the Spanish Ministry of Universities. The funding bodies played no role in the design, execution, analysis, and interpretation of data, or writing of the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethics statement

The questionnaire and protocols for this survey were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) with reference number 155/2021. The experiment was pre-registered in As Predicted under the name ‘EUCOMMEET CONJOINT EXPERIMENT – Elite preferred deliberative events, January 2023’ and with reference code #120365.