Introduction

Argelia is a small municipality in southwestern Colombia, in the department of Cauca. For the last three decades it has been an important producer of cocaine and a stronghold of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, People’s Army (FARC-EP) (Gutiérrez Reference Gutiérrez2020). In mid-2015 the rebels went into a unilateral ceasefire while in peace talks with the government. Following that agreement, three key events occurred in Argelia which not only revealed the deep distrust between the community and the state, but also strained the relationships with the rebels. The first, in November that year, the Colombian army carried an anti-narcotics’ operation in Argelia that resulted in the death of a 20-year-old man, while 15 others were wounded. Later, in December, another altercation took place as people claimed that soldiers had tried to rape a girl.Footnote 1 The third event occurred on May 19, 2016, when two military helicopters arrived at the village of Sinaí, raiding homes. Community members recorded a video in which soldiers took money and crack cocaine from houses, which protesters recovered by force.

On that occasion, the crowd caught the man presumed to have given information to the military. They took him to the FARC-EP camp, but the rebels declined to act as the ceasefire was in place. Some weeks before, an alleged rapist had been brought to them and they declined to take action on that case too—he was handed to the authorities, and, to everyone’s dismay, the suspect was immediately released. Now the community had to decide on their own what to do about the informer. Despite finally agreeing to hand him over to the government after tense negotiations, the suspect was shot dead before the whole village by an unidentified man in a balaclava, who was thought to work for the cocaine laboratories.Footnote 2

Still in shock, a community commission went to the FARC-EP camp to complain about the breakdown of order, about their lack of reaction to the army’s aggressions, and for leaving the “problem” (informer) in the hands of community leaders. One incensed person reprimanded the guerrilla commander, “Who’s your peace process with? The government or the informers and rapists?” The guerrillas, however, refused to leave the camp until their demobilization once the peace agreement between the rebels and the government was signed up in late 2016.

While rebels in a period of transition face themselves several challenges (Ugarriza et al. Reference Ugarriza, Quishpe, Acuña and Salazar2023), so do communities in the territories where they once operated. The above incident reflects not only the challenges of the FARC-EP’s demobilization, but also sets out the puzzle for this article. Wartime governance literature notes that the community’s previous experience with the state (cf. Mampilly Reference Mampilly2011), the interactions between states and armed groups (cf. Staniland Reference Staniland2012, Reference Staniland2021), rebel-community compatibility and their perception of the state (Florea and Malejacq Reference Florea and Malejacq2024), or the strength of community governance institutions before the arrival of rebel groups (Arjona Reference Arjona2016) shapes rebel and/or local order. Yet how do long-term experiences of living with rebel rule shape a community’s engagement with new actors attempting to fill the authority vacuum post-demobilization?

We argue that these long-term experiences not only set community norms and expectations, in line with Voyvodic’s (Reference Voyvodic2021) work on the aftermath of the FARC-EP’s demobilization, but also shape their support or opposition to new attempts by the state and/or armed groups establishing order in the territory. In post-demobilization settings, where peacebuilding is fragile and the risk of relapse into conflict is high (Bara et al. Reference Bara, Deglow and van Baalen2021), the mismatch between expectations and realities on the ground can create a favorable context for the (re)emergence of armed actors that can feed into a new cycle of violence (Gutiérrez-Sanín Reference Gutiérrez-Sanín2020). Civilians themselves make demands for governance that new actors in the territory may find difficult to ignore (Florea and Malecjaq 2024). We argue that the governance expectations of the communities, and the actions they take in response to new governance actors are based on their previous experience with rebel governance, even as they are limited by constraining factors in the post-demobilization landscape, including the degree of community organization and the capacity and ideology of the new actor. Understanding this iterative relational dynamic between community, governance expectations, and new armed groups is therefore key to peacebuilding efforts after protracted conflicts.

As the story from Argelia shows, the civilians’ experiences with rebel governance shape their expectations for local order post-demobilization and what demands they make.Footnote 3 Through three case-studies in Colombia—rural communities in San Vicente del Caguán (Caquetá), Valle del Guamuez (Putumayo), and Suárez (Cauca)—we show how the FARC-EP’s presence prior to demobilization shaped the community’s expectations for what governance looked like: these areas were all strongholds of FARC-EP support and the rebels enjoyed significant legitimacy. In turn, these expectations structured how communities engaged with new actors in the territory post-demobilization, establishing a blueprint they used to try and rebuild order in the territory alongside new armed actors.

However, although the starting point of the three case-studies is similar (a strong relationship with rebel governance pre-demobilization), the varying landscape after the 2016 peace agreement constrained how communities were able to actively engage in rebuilding order, limiting their ability to make demands, or take actions themselves when the new armed actor could not or would not. In the fragmented conflict landscape after the FARC-EP’s demobilization, not all new or reconstituted armed actors in the territory had the same capacity or interest in governing like the FARC-EP. Therefore, depending on the capacity and ideology of the new armed actor in the territory, communities could struggle with having their expectations for a FARC-EP-like governance met. We also find that where communities had a degree of coherence and organization, they were not only able to influence the configuration of local order (Kasfir Reference Kasfir, A, N and Mampilly2015; Arjona Reference Arjona2016; Podder Reference Podder2017) but actively play a role in filling the governance gap left by the previous rebel rulers.

Despite those factors constraining the agency of local communities, we observe that new attempts at establishing order were done in dialogue with the community’s past experiences of rebel governance. We first explore the governance expectations of these communities through the lens of relational security (Voyvodic Reference Voyvodic2021) which examines how the FARC-EP’s governance shaped community priorities for order post-demobilization, including shielding from external threats, social regulation, and evidence of accountability and attribution by the governance actor themselves. We then show how communities translated these expectations in their engagement with new actors in the territory, assessing their legitimacy based on comparisons to the FARC-EP, and then making demands and even taking direct action to try to ensure these standards of governance are met. By taking this approach, our argument builds on the logic of “security markets,” which has been discussed in the past to understand the relation between bottom-up demands for security and top-down offers (Branović and Chojnacki Reference Branović and Chojnacki2011) and the tension between supply and demand in rebel governance (Florea and Malejacq Reference Florea and Malejacq2024).

In this article we will first discuss the existing literature on rebel governance, its legacy, and community agency as we highlight the importance of these dynamics post-demobilization. We then explore the specific co-constituted nature of FARC-EP governance pre-demobilization with civilian communities to provide critical historical context before outlining our case selection and methodology. We then examine how the FARC-EP’s legacy shaped community expectations for governance post-demobilization, and then how this legacy influenced the community’s more active involvement in rebuilding order with new or reconstituted armed actors in the three key case-studies: Cauca, Putumayo, and Caquetá. All three of these former FARC-EP strongholds face uncertain conflict landscapes post-demobilization and new co-constituted forms of order between communities and new or reconstituted armed actors. Yet even after demobilization, legacies of rebel rule remain crucial for understanding these dynamics and the role of the community in reproducing rebel governance. Factoring in these legacies of rebel governance is paramount to understand both popular expectations and challenges that affect dynamics in peacebuilding settings where rebels had for protracted periods a foothold (Voyvodic Reference Voyvodic2021; Gutiérrez Reference Gutiérrez2021). Pressure may well emerge from below against future peace accords that do not address decisively these expectations and demands, where splinter groups and dissidents proliferate, and communities may seek a predictable insurgent order to an unpredictable “peace.”

The Legacy of Rebel Governance and Community Expectations

The question of the legacies of rebel governance has begun to take the center stage in conflict studies. Wartime governance developed during conflict can continue beyond the cessation of formal hostilities, affecting the efficacy and authority exercised by new governments and opposition groups in the post-conflict period (Huang Reference Huang2016; Dirkx Reference Dirkx2020) and their level of support from local populations (Verwimp et al. Reference Verwimp, Justino and Brück2009; Kubota Reference Kubota2017; Terpstra and Frerks Reference Terpstra and Frerks2017; Martin et al. Reference Martin, Piccolino and Speight2022).

Simultaneously, there is a growing body of work that shifts the focus on rebel governance away from “supply-side” (i.e. the perspective of rebel rulers) to “demand-side” (the preferences of civilians) (Florea and Malejacq Reference Florea and Malejacq2024; Kubota Reference Kubota2017). Florea and Malejacq (Reference Florea and Malejacq2024) argue that negative perceptions of the state can drive civilians to make demands on armed groups. We draw on the rebel governance legacy to build on that approach by layering the previous experience with rebel actors in shaping expectations post-demobilization. These expectations, in turn, can influence demands and actions taken by the communities vis-à-vis new or old armed actors. In doing so we also address Voyvodic’s (Reference Voyvodic2021, 190) observation that positive experiences with rebel rule requires further study to understand acceptance or support for other non-state actors post-demobilization.

We structure this approach by examining the expectations, which are the baseline preferences of these three local communities in what local order should look like, and what authorities should do, in the aftermath of the FARC-EP’s demobilization (and where governance actors fall short). We then examine their agency, first looking at their demands, or the proactive choices that members of the communities make to elicit specific actions from an armed actor as conditions for a legitimate governance relationship. Finally, we examine where communities chose to act themselves to address these preferences when other actors are insufficient or incapable. We argue that their prior experience with FARC-EP governance is a key factor shaping their expectations, but the conditions of the new conflict landscape and their own organizational capacity structure their demands and actions.

Armed groups may impose their norms, but civilians are often not passive spectators, and they play a role in shaping, evolving, and reinforcing at times the governance by non-state armed actors (Arjona Reference Arjona2016). As Kasfir (Reference Kasfir, A, N and Mampilly2015) argues, where civilians are united with clear shared expectations, they are able to influence the behavior of armed group governance. In turn, the ideology and capacity of armed groups structure their choices in how to govern, with a desire to reach their revolutionary objectives (Stewart Reference Stewart2021) or “putting their ideology in practice” (Arjona Reference Arjona2014, 1362) incentivizing them to have a closer relationship with marginalized communities. Rebel governance is, therefore, co-produced between segments of the local communities and rebels, many of them local too (Espinosa Reference Espinosa2003; Podder Reference Podder2017), with various degrees of legitimacy depending on several variables (Daly Reference Daly2016). This was well documented in various regions of Colombia, where rebels engaged with communities in the co-production of community rules and in enforcing the decisions of the local community-based bodies, which fostered their legitimacy in places where rebels were regarded as responsive to local demands (Gutiérrez Reference Gutiérrez2019).

Therefore, we argue that, after the 2016 peace agreement, civilians remain active participants in governance by other armed actors in ways that draw on their specific experience and expectations rather than make top-down and prescriptive assumptions about what security may “look like” for any community. This approach not only builds on relational concepts of security, but also on the notion of legitimacy between governor and governed as a constant dynamic readjustment of behavior and expectation (de Bruijn and Both Reference de Bruijn and Both2017; Podder Reference Podder2017; Schmelzle and Stollenwerk Reference Schmelzle and Stollenwerk2018).

In this article we examine how communities in regions with extensive support for insurgents prior to the 2016 peace agreement and subsequent mass demobilization, draw on this legacy of rebel order to structure their expectations, make demands, and even take actions around security provision and governance in the face of new emerging or reconstituted actors. In the next section we highlight the particular governance practices of the FARC-EP and how these structured the way communities respond to new governance actors after their mass (but not universal) demobilization. By focusing on how civilians and armed actors invoke previous relationships, we deepen our understanding on the reconfiguration of armed groups and the role of civilian agency in the co-production of order post-demobilization in Colombia.

The FARC-EP, The Community, and The Co-production of Order

After the Colombian government and the FARC-EP signed up the peace agreement in 2016, although large numbers of seasoned combatants demobilized, peace has proved elusive. Massive problems in implementing the agreement, the persistence of agrarian inequalities, the lack of clear incentives to peace and the legacies of violent conflict, have led some to claim Colombia is entering into a new cycle of conflict (Gutiérrez-Sanín Reference Gutiérrez-Sanín2020; Gutiérrez Reference Gutiérrez2021). This is why we refer to this period after the 2016 peace agreement as post-demobilization (as opposed to post-conflict).

However, before their mass demobilization in 2016, the FARC-EP had not only waged a long-standing guerrilla campaign against the state but also established many pockets of rebel order in rural territories. While these orders were at times very coercive, FARC-EP rule was practiced, generally speaking, under clear guidelines, with an established hierarchy, and a great deal of discipline. The rebels, indeed, were fond of procedures: this illegal guerrilla organization was, paradoxically, intimately permeated by a certain legalistic spirit prevalent among Colombian bureaucracies (Gutiérrez-Sanín Reference Gutiérrez-Sanín2001; Cubides Reference Cubides2005). This ideology led to—often—close cooperation between the FARC-EP with the local Community Action Boards, or JACs, to demonstrate their commitment to responding to community needs (Gutiérrez Reference Gutiérrez2021; Voyvodic Reference Voyvodic2023), where interactions were often carefully regulated by a series of manuals and laws. There was structure and predictability to these expressions of rebel governance, which are the landmark of a particular social order (Arjona Reference Arjona2016). The coercive capacity, in sum, depended on more than the rebels’ undeniable capacity for organized violence: it also rested on shared values and normative conceptions (Espinosa Reference Espinosa2003; see on this point Tyler Reference Tyler1990).

These shared values and normative conceptions often emerged in the production of so-called manuals of coexistence (manuales de convivencia), which represented the basic “law of the village.” Often, the FARC-EP had manuals’ templates containing regulations on a wide range of activities such as transactions, the slaughter of animals, religious cult, civic participation (in the local Community Action Boards, or JACs), public order, security (from the army’s infiltration), and environmental regulations. These acted as a guide and input for communities writing their own manuals (Gutiérrez Reference Gutiérrez2019).

Regulatory mechanisms were standardized at JAC level, based on these manuals. Community-based processes for adjudicating transgressions in regions like San Vicente del Caguán (Caquetá), Valle del Guamuez (Putumayo) and Suárez (Cauca) were free, accessible, and much faster than ordinary tribunals, remaining the preferred method to solve disputes (Espinosa Reference Espinosa2003; Aguilera Reference Aguilera2014). Until the late 1990s, it was typical for the FARC-EP to be routinely involved directly in adjudication procedures. But this situation started to change in the mid-2000s, and the JAC’s conciliation committee became the normal route to adjudicate, with the FARC-EP intervening “only if the problem was beyond the capacity of the [JAC] leaders (Germán interview 2017),” in cases such as rape, murder, informants, and people usurping the name of the organization (often for extortive purposes). The main role of the FARC-EP was that of enforcers of decisions reached by the JAC’s adjudication bodies: “The authority of the JAC is respected because of this [FARC-EP backing]” (Si-m-Ca-05 2017). This shifted more of the decision-making towards community representatives, even if the FARC-EP’s power of enforcement still gave teeth to their rulings.

The dismantling of this order in the period immediately after the mass demobilization of FARC-EP combatants (2016–2017) created a situation that has been described as a power vacuum (Krause et al. Reference Krause, Nicola Clerici, Paula Sánchez, Esguerra-Rezk and Van Dexter2022) in which the predictability of the old order was gone without being suitably replaced. Despite the agreement with the FARC-EP, other armed actors remained an important presence in many regions, including groups of non-demobilized FARC-EP, the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the much smaller People’s Liberation Army (EPL), together with a number of paramilitary groups, including the largest of these, the Colombian Gaitanista Self-Defence Forces (AGC) (Gutiérrez Reference Gutiérrez2021; Ramírez Reference Ramírez2022). As this fragmented security landscape emerged, situations like that described in Argelia led to a pervasive sense of disorder and insecurity in many places previously under FARC-EP control (see also Voyvodic Reference Voyvodic2021).

This led to new groups emerging post-demobilization that included former members of the FARC-EP. Some of them claimed a link to the original FARC-EP, such as the Segunda Marquetalia group, who argued that they had been forced to re-arm because of the “dishonesty” of the Colombian government who had not fulfilled its part of the agreement and had actively opposed it in many ways (Gutiérrez Reference Gutiérrez2021). Other groups featuring prominently demobilized guerrillas, such as the Comandos de la Frontera (Frontier Commandos, CDF) in Putumayo or the Pocillos in Argelia, abandoned their former revolutionary intentions and dedicated themselves to illegal activities for private profit—sometimes linked to elements of the armed forces, and often in violent opposition to the presence of the non-demobilized FARC-EP in their regions.Footnote 4 In this miasma of disorder, understood as lack of structure and predictability (Arjona Reference Arjona2016, 26–29), the communities’ expectations for security came into focus, leading to demands across the three cases (and even actions being taken in one) to re-establish a sense of order they felt was gone with the mass demobilization of the FARC-EP.

Methodology

Data was collected between October and November 2022 in the municipalities of Suárez (Cauca), San Vicente del Caguán (Caquetá), and Valle del Guamuez (Putumayo) (Figure 1). Although we anonymized personal information and the identities of participants, the communities where we have conducted our research are named for two main reasons. First, because of transparency and verifiability. Second, and more importantly, because the very organizations we worked with felt they wanted their side of the story told. As such, we felt that anonymizing the communities—which in any case have been subject to very negative press over the years in the media—did not contribute to their security, and instead it smothered their voices and the stories they shared with us.

Figure 1. Location of the Case-studies.

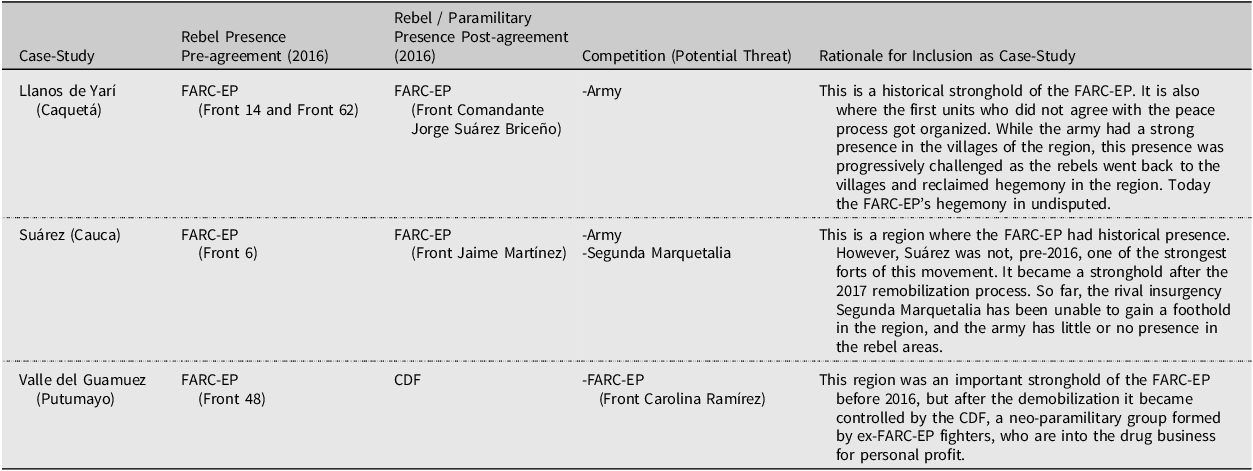

These communities were selected because they represent three diverse cases on the fortunes of rural communities in areas traditionally controlled by the FARC-EP in the aftermath of the 2016 peace agreement. Another important consideration is that in all these three cases we had very good access before and after the peace agreement of 2016 and the subsequent demobilization process—this allowed us to access rich empirical data for this article. In all three the FARC-EP had a long-standing governance presence prior to demobilization, but they had different interactions with armed groups after demobilization in 2017. In the municipality of Suárez, research was conducted in the villages of Betulia and Playa Rica. This area had been in the heart of operations by the 6th Front of the FARC-EP. Post-demobilization, part of the FARC-EP reconstituted themselves in the region after some bloody fights with other rival factions, in particular the EPL and the Segunda Marquetalia.Footnote 5 In San Vicente del Caguán, research was conducted in Llanos del Yarí, a region where the FARC-EP had been traditionally hegemonic. This, and the neighboring Guaviare, were the strongholds of the non-demobilized FARC-EP faction that rejected the peace agreement. During the peace negotiations the 14th Front of the FARC-EP in this area retreated from areas like Ciudad Yarí for a short while, only to come back from the surrounding jungles after a few years. Finally, the area of El Tigre in Valle del Guamuez was an important bulwark of the FARC-EP, but since the demobilization, a number of former guerrillas started to collaborate with right-wing paramilitaries and common criminals, eventually forming what local communities perceive as a new paramilitary group controlling the region, the CDF (Table 1). As such, our results concern mostly regions where the FARC-EP used to have strong support and legitimacy, and do not necessarily reflect other territories where this support was more open to contestation from other (armed or unarmed) actors.

Table 1. The Case-studies in this Article

Post-demobilization, we see three different types of reconfigurations of armed actor presence in the territories. There is a successful reconstitution of the FARC-EP in Suárez (mostly driven by new recruits, although the core were people with previous experience in the FARC-EP), a continuation of the FARC-EP in San Vicente del Caguán, and in Valle del Guamuez a rival armed organization is dominant, although there are currently ongoing attempts by the FARC-EP to re-assert itself in the municipality (see Table 1). Despite these differences, all three cases possess a legacy of FARC-EP governance and persistent distrust in state authority. Across all three, the expectations and demands by local communities in this insecure new landscape draw on experiences with previous FARC-EP governance, but they played out differently depending on the level of organization of the community and the hostility of the dominant post-demobilization armed actor against their organizational activity. We also note that accessibility and security concerns played a role in selecting these cases, where long-term relationships with local gatekeepers enabled the collection of detailed first-hand data in areas under rebel or armed control.

We used participant observations methods (Bulmer Reference Bulmer1984; Hammersley and Atkinson Reference Hammersley and Atkinson2007) and key informant interviews with well-known community representatives (Table 2) to conduct research. We prioritized a select number of in-depth interviews, which typically lasted 2–3 hours, with trusted sources. Particularly in Putumayo, the conditions of the interviews were difficult, and all precautions were taken not to risk the participants or the researcher, as the region where the interviews were conducted is currently held by the paramilitary CDF who are particularly hostile to the old leadership of the agrarian unions and the community-based organizations. Key informant interviews were ideal in this case because we needed to prioritize extensive, in-depth interviews over sensitive topics with people with a significant amount of insiders’ knowledge and whom we could trust as sources. Key informant interviews are also particularly useful to complement participant observation (Blee and Taylor Reference Blee, Taylor, Bert and Suzanne2002) and informal conversations held in prolonged interaction with research participants (Hammersley and Atkinson Reference Hammersley and Atkinson2007). The research design was subject to the ethical approval of the Université Libre de Bruxelles, and a thorough ethical consent protocol was developed to guarantee the security, appropriate representation, and dignity of all participants.

Table 2. Key Informant Interviews Conducted in October–November 2022

After the data collection, we conducted thematic analysis to help identify the key factors of rebel governance that communities prioritize in relation to their own security and how they respond to their absence. This approach was inspired in part on the relational security framework used by Voyvodic (Reference Voyvodic2021) to examine the specific features of rebel order communities invoked to make sense of their own insecurity after the FARC-EP’s demobilization. After coding these interviews, our results were triangulated with notes and observations from the field, both from this current fieldtrip, but also of previous fieldwork from the period 2014–2018, which included Argelia (Cauca), and Chaparral (Tolima), which are used to showcase particular dilemmas of the post-demobilization period. We use these secondary cases to help flesh out the consistency in the challenges faced by communities in a post-demobilization and/or transitional environment. The study highlighted the desire for social regulation, shielding from external threats, and accountability and transparency (termed attribution by Voyvodic Reference Voyvodic2021) by the authority. These helped guide the analysis in the three case-studies examined in this article, and the building blocks to better understand how communities drew on past experience with the FARC-EP to make sense of their relationship with new or reconstituted actors in the territory.

We used these indicators to identify how the community actively sought to reproduce the governance standards by the FARC-EP with post-demobilization actors in San Vicente del Caguán (Caquetá), Valle del Guamuez (Putumayo), and Suárez (Cauca). Once we identified the communities’ expectation of order, we could determine what members of these communities chose to or could do to (re)-establish it, especially in the face of a new security landscape and the re-emergence of armed actors in their area. As a result, we determined that members of communities not only expressed their expectations for governance (and where actors fell short) but also actively made demands to new armed actors (including a reconstituted FARC-EP) to meet these expectations developed under previous FARC-EP rule, and even took a more autonomous role in monitoring and enforcing the security-producing features inherited from previous rebel order in one case.

Legacies of Rebel Governance and Community Expectations

The vacuum left by the FARC-EP in the aftermath of their demobilization was forecasted by members of these communities, who feared “that we would be left alone, unprotected, for they were no longer going to keep an eye on robberies and rape” (Ca-01-f 2022). In this section we examine how communities in former FARC-EP strongholds viewed the efforts of new armed actors to fill the gap left by the FARC-EP. The legacy of the FARC-EP’s governance and the involvement of the community in the past resulted in their expectations of governance, which then translated into demands of governance and actions of governance, explored in the next section.

In this section we explore how across the three cases the community drew on their experience with the FARC-EP to frame their expectations of new armed actors, including the state, attempting to assert their presence in the territory. This section builds on Voyvodic’s (2021) relational framework, exploring how communities used the FARC-EP’s governance legacy to assess the new actors’ ability to shield them from external threat, regulate social behavior, communicate their norms and structure (attribution), and demonstrate a degree of accountability.

Failures to Fill the Governance Gap

After the demobilization of the FARC-EP, many communities’ expectations for social regulation were not met by the substitute authority of the state. At best, the army were accused of not intervening in the face of what locals considered to be delinquent behavior, such as in Llanos del Yarí, Caquetá: “there was no regulation, music was loud [ed. in bars] at any time, there were robberies, delinquency, and the army didn’t do anything about this” (C-01-m 2022). At worst, the army was accused of being proactively involved in delinquent behavior: “wherever those bastards arrive, there is vice. They consume crack, marijuana also arrives” (C-02-m 2022). The presence of the army was regarded by participants as not contributing to the local order, and they were suspected to be behind threats and violence against community organizers. Their presence was also associated with a number of unsavory situations, like drug consumption and theft (C-02-m 2022). As such, “with the renaissance of the revolutionary movement, the FARC, the army started to abandon the villages” (C-01-m 2022), a situation which left the reconstituted FARC-EP as the preferred authority in the area.

To many in these communities, the FARC-EP had an authority that the state did not possess. According to community leaders in Suárez, Cauca, “the peasants don’t listen to the army, but they do listen to the guerrillas” (Ca-02-f 2022). Participants mentioned that “when the FARC speak and order, everybody complies” (Ca-02-f 2022). The reconstitution of the FARC-EP in some crucial ways was regarded as re-establishing a lost pre-2016 order: “When the movement [ed. FARC-EP] re-appeared, the meetings started again […] and they started to put order in the region, stop thieves and delinquents” (C-01-m 2022). Even if some people were not enthusiastic about the FARC-EP in some respects, it was claimed, they appreciate the order they brought, for “there is much more order now. To some, the FARC is like a necessary evil” (C-02-m 2022).

In other cases, the presence of so-called paramilitary groups, such as the CDF in Putumayo were regarded as a poor substitute, although there was an attempt to impose regulation by these in ways which, allegedly,

resembled the 48th [ed. Front of the FARC-EP], because at the parties they […] prevented fights. That works alright. They put high fines, a lot of labor, building roads. A lad started a fight, and he paid that dearly, he had to build 100 meters of road, and he had to pay for both materials and labor. […] This happened near the border [ed. with Ecuador]. (P-01-m 2022)

This resemblance to the FARC-EP can be partly attributed to the fact that some CDF commanders were demobilized FARC-EP militants under the 2016 peace agreement. However, the same interviewee was quick to point that the CDF’s regulations were reduced to imposing fines without any pedagogy behind, while “the difference with the FARC is that the latter were political […] so people are waiting for these folk [ed. FARC-EP] to come back so they put a little bit of order” (P-01-m 2022).

Shielding against External Threats

Also, the post-demobilization actors’ ability to address potential threats coming from outside the territory (shielding) could reinforce their connection to the FARC-EP’s legacy. In Cauca, the presence of a rival guerrilla organization, the EPL, was regarded by participants as problematic from a social order point of view, as their presence coincided with a wave of murders—one per week in Suárez (Ca-03-f 2022)—and with threats to social leaders who were accused by the EPL of being in organizations linked to the reconstituted FARC-EP (Ca-02-f 2022). Rival actors, like the EPL or Segunda Marquetalia have been confronted by the latter. As explained by a leader in Suárez, the fear was that “some of the EPL were working with the army […]” (Ca-02-f 2022). The FARC-EP however “finished with the [EPL]” in the area (Ca-01-f 2022). A similar argument about shielding from external threats emerged when discussing another attempted incursion:

When Segunda Marquetalia showed up in Buenos Aires [ed. a neighboring municipality to Suárez], in the village of La Esperanza, they fought them. We were afraid here, for, if these guys [ed. FARC-EP] were not alert, those other guys [ed. Segunda Marquetalia] could come here and kill our leaders. But they did not leave La Esperanza. Fighters died in both groups, but they did not leave. But the Segunda is still a danger, although these guys here are stronger. (Ca-03-f 2022)

However, although this shielding prevented undesirable actors from entering the territory, the community was not without criticism of the reconstituted FARC-EP. According to participants, the agrarian union “tried to mediate in Betulia, to avoid confrontations […] but on December 8, 2017, they [ed., FARC-EP and EPL] fought each other. Seven or so were killed in Aguabonita and La Cabaña […] in such a terrible shoot-out they put the village at risk” (Ca-02-f 2022). Therefore, while the reconstituted FARC-EP was seen as addressing an external threat to the community, the participants were aware of how this also jeopardized security by putting the villagers at risk in the crossfire.

Participants in Cauca saw this protection from the reconstituted FARC-EP as a natural extension of both the group’s own interest in their territorial control and their obligation to address insecurity for the community. One participant explains that “security is a two-pronged problem. On the one hand, it is about theft, extorsion, and on the other, it is their [ed. FARC-EP] security, because they cannot allow other groups to enter the territory” (Ca-02-f 2022). Among all case-studies, there was widespread agreement that as soon as the FARC-EP demobilized in 2016 “criminal gangs started to wreak havoc in the community (P-01-m 2022. Similar opinions were expressed by C-01-f 2022, and Ca-01-m 2022).” Shielding the community from perceived external threats (including the army in this case) is an important element of any form of governance. In Putumayo, when the army appeared in the context of anti-narcotics operations, the CDF told communities to oppose them, but people were reluctant to follow their orders: “Why do we have to go out and defend their business? Because they do not fight with the eradicators at all […] they don’t even show up, and we were all gassed […] I didn’t like that. They are useless, they are no army because they don’t fight” (P-01-m 2022). Expectations by the community for protection against the army were not met by this new group compared to the previous FARC-EP, and the unstable security conditions further diminished any faith in their ability to govern. Participants in Putumayo also expressed their desire for the reconstituted FARC-EP to expel the CDF (P-02-m 2022).

Fear of paramilitarism was explicitly mentioned as a reason for the reconstituted FARC-EP support in Cauca:

We are afraid that [a transnational company in the region] will hire paramilitaries. For this reason, the FARC are a support […] in the defence of the territory. The FARC will not allow the paramilitaries here. Their military work gives them security as FARC, but it also provides security for the social leaders, they have looked after them. They [ed. army, paramilitaries] have tried to kill leaders, but they look after their security. We experienced what paramilitarism is like in 2000 and we do not want to go through that again. (Ca-02-f 2022)

The legacy of the FARC-EP as an actor that was perceived—on balance—to be more on the side of communities in these territories and that supported its social leaders and strengthened the claims of authority by the reconstituted FARC-EP. This fear of infiltration by potentially dangerous groups, either criminal or rival, has been mitigated by further measures taken by the FARC-EP including tightening traditional forms of control, like ensuring that those who enter the territory carry a letter of recommendation from the JAC in their place of origin, and checkpoints (see Figure 5). This, according to participants, had stopped the entry of “people with bad intentions, for the social leaders are vulnerable to the state and their informers, and these checkpoints have been useful” (Ca-03-f 2022). In Caquetá, although checkpoints are rare, we observed the widespread presence of campaneros, or guerrilla watchmen, in every village, taking note of the movement of people in public or private transport.

Social Regulation and Public Order

The reconstituted FARC-EP also appeared to meet community expectations of replicating their old order that went beyond a narrow understanding of safety against a violent threat, but also through environmental regulations and public order around bars. In relation to the former, we were told by community leaders in Suárez, Cauca, that the rebels “are aware that coca improves the economy, but it also causes damage, so they have helped” (Ca-02-f 2022) to regulate environmental damage caused by the processing of coca (cf. Gutiérrez and Thomson Reference Gutiérrez and Thomson2021). “It is they who can put limits to the areas where coca is planted, not the community, because the FARC has more consciousness on this issue,” highlighting how the reconstituted FARC-EP was able to show continuity with the standards of the old FARC-EP, including establishing norms that the leaders, in this case, justified by claiming the lack of awareness of the broader community (Ca-01-f 2022). These leaders recalled the FARC-EP pre-demobilization as the standard by which the reconstituted FARC-EP was expected to provide ideological guidance where the community fell short.

In Llanos del Yarí, Caquetá, the reconstituted FARC-EP also put regulations back in place given poor state investment in infrastructure: for instance, they started to compel people to participate in collective works (mingas) to improve vital infrastructure, such as aqueducts or road maintenance. There, they also played a role “stopping the logging, deforestation, and hunting” (C-02-m 2022). The same was mentioned about controlling noise levels from bars and licensing hours. The fact that this reconstituted FARC-EP could enforce regulations emanating from local governance bodies was perceived as improving public order. While one individual noted that compliance was largely driven by fear of their weaponry (Ca-01-f 2022), their exercise in social regulation was identified across the cases as something beneficial by the majority. Even the CDF in Putumayo, although organizationally very different, were said to have had to behave similarly in relation to the mingas: “they bring the people out through the JAC, because they have relations there […] so they organize mingas to fix the road, that is something they are doing” (P-02-m 2022).

Attribution and Accountability

Communities across the three cases also placed a premium on attribution, or the ability of the group to communicate their structures, policies, chain of command, and so on to the civilian population (Voyvodic Reference Voyvodic2021). This transparency goes beyond knowing the people in the group; it is knowing their position, responsibilities, and their intentions. In the case of Putumayo, for instance, people knew personally many of the fighters in the paramilitary group CDF. However, according to a key informant:

you really don’t know who’s who, for when the peace process started, Manuel [ed. former commander of the FARC-EP 48th Front turned into a drug and paramilitary boss] started up three cocaine crystalizing facilities with 300 men in his camp […] some of them I recognized from the time of the 48th Front […] but I don’t have much knowledge about the command structure. Because you never see any other than the dominionistic [ed. drug dealers]. You never see the big fish […] and those I’ve seen, are all in civilian clothes, only carrying a gun. (P-01-m 2022)

Not knowing who’s who in the structure means, according to this participant, that it is unclear what the channels of communication are, what to expect from the armed group members, and so on, particularly when the previous group has done this successfully, therefore setting a precedent.

In Caquetá, the army also added to the confusion of attribution: “sometimes they presented themselves as dissident guerrillas, those who did not demobilize, but they were the army […] what we have witnessed of late, is the army pretending to be Sinaloas [ed. paramilitaries]. This is how they introduced themselves in Berlín [ed. a village in Caquetá]” (C-01-m 2022). Interestingly, the reconstituted FARC-EP in Caquetá (and elsewhere) appeared to no longer wear their uniform, but by observing interactions with the communities, everybody knew who’s who in the structure. This could be partly helped by the fact that most of the rank-and-file and commanders were local, and the chain of command was considered clear and simple, and included norms around the behavior of their own combatants: their disciplinary regime is defined in the Statutes of the FARC-EP, which the current organization follows, and has mechanisms to address meticulously defined transgressions.Footnote 6 This was a structure with which the local population had decades of familiarization. As we discuss in the next section, this expectation of accountability was also met by when the reconstituted FARC-EP in Cauca acquiesced to community demands by correcting the poor behavior of some of their own cadres.

Therefore, attribution is not necessarily merely about wearing a uniform but about transparency and communication of their position, what in turn can foster accountability. In Cauca, the EPL arrived shortly after the FARC-EP 6th Front demobilized and left the region. Their approach was at odds with the governance characteristics the community had experienced with the FARC-EP. “We were told that some arrived […] and that generated fear. They did not identify themselves, who they were, nothing” (Ca-01-f 2022). According to a community leader in Cauca,

Around 2017, 2018, we started to see another armed group. They arrived with neat uniforms, and settled in La Chorrera, Playa Rica … they were not the same crowd, it was rumoured they were the EPL […] although they were uniformed, they never introduced themselves, so, at first, we thought they were the same. Only when they were exterminated, we learned they were the EPL. (Ca-02-f 2022)

In contrast, when the reconstituted FARC-EP arrived, “they introduced themselves” (Ca-01-f 2022); “we started to see them more and more in civilian clothes, whereas before they wore more often the uniform, however, we knew it was them” (Ca-02-f 2022). While this FARC-EP no longer wore uniforms, save for special occasions (see Figure 2), they still behaved in ways that allowed communities to identify them, therefore minimizing fear at their arrival and meeting expectations of transparency and visibility. The reconstitution of the FARC-EP had the advantage over groups such as the EPL in presenting group structures and goals that the locals were already familiar with because of their previous experience in those same communities. While there was dissatisfaction with this new order from time to time, at least there was a familiar structure and accountable people to be approached.

Figure 2. FARC-EP Guerrillas in Full Uniform, for the Funeral of a Fallen Commander, Suárez, Cauca, November 4, 2022 (Image by José A. Gutiérrez).

Legacies of Rebel Governance and Community Agency

While these expectations reflect a clear throughline of the FARC-EP’s legacy, the communities across all three cases also took more active roles in shaping the co-constituted nature of rebel order by making demands and even taking action where post-demobilization actors failed to live up to expectations. In this section we examine how communities drew on the FARC-EP’s legacy in making demands and in taking action to address gaps in governance after such a major demobilization and reorganization of the rebel group. However, we observe that while the communities were engaged in reshaping this order, their responses depended in part on degree of organization in the community and on the hostility and capacity of armed actors towards them.

The JAC and Rebuilding Relations

The group also had to account for communities making demands of governance based on previous rebel rule. This often meant a return to the relationship between the JAC and the FARC-EP, where the armed group appeared to acknowledge and respect the demands of the community put forward through the JAC. In Suárez, Cauca, one participant explained that: “when they controlled the region, the FARC-EP said they respected the JAC, and they got rid of the EPL […] that made us trust them” (Ca-03-f 2022).

In Caquetá, the participants accused the army of threats violence against the JACs, so the association “became inactive […] in El Triunfo […] they even killed the president of the JAC.” According to the same participant, while the JACs were still functioning on paper at the time the army was in control of the region, “some of the committees within the JAC ceased to exist, like the health, environmental, and conciliation committees” (C-02-m 2022). According to participants, all very active in the JAC, the arrival of the reconstituted FARC-EP to Caquetá also meant that the authority of the JAC was again respected, particularly on attendance to JAC meetings that started happening again (in many of these villages mandatory), on participation in collective works, and in terms of respect of the decisions of its conflict-resolution mechanisms (C-01-m 2022; C-02-m 2022; C-01-f 2022). After this, the JAC established regulations and fines regarding speed limits on the precarious roads, which the reconstituted FARC-EP also started to enforce (Figure 3). Although the reconstituted FARC-EP was still involved in influencing these decisions, it was ultimately the community organizations that set out the policies that were seen as beneficial while the former primarily played the role of enforcer.

Figure 3. JAC Banner Setting a Speed Limit and the Corresponding Fine in Campo Hermoso, Caquetá. Beneath, a FARC-EP Banner (Image by José A. Gutiérrez).

Peasant communities in places like Suárez, Cauca, had plenty of experience to draw from in re-establishing these dynamics of norms and enforcement with the reconstituted FARC-EP. As explained by a JAC leader in Argelia after the 2016 demobilization: “The JAC and its norms were respected by the broader community because of this [FARC-EP backing]” (Si-m-Ca-05 2017). Punishment would often include tasks such as working on the road, cleaning up the village, or gathering construction materials. Therefore, the reconstituted FARC-EP appears to take a similar approach in enforcing norms set by the community leaders through the manuals of coexistence in Cauca and Caquetá.

In Putumayo, the relationship to the local JACs and the CDF could be quite complex. In some parts near the border with Ecuador, the CDF had built a strong relationship with the JACs and drew from previous interactions between individual commanders who once were in the FARC-EP and their own personal networks in those communities and with the leaders of some JACS (P-02-m 2022). However, in Valle de Guamez, the relationship between the JAC and CDF was strained, as the CDF had murdered a number of social leaders they believed were related to the reconstituted FARC-EP. Still, according to one participant, “although people are no longer going to the meetings of the JAC, those who go, tell them a few truths and scold them. They are selecting their own stooges for the leadership of the JACs, but they can’t control everybody” (P-01-m 2022). He complained that in this region, the JAC meetings had been turned mostly into spaces for them to control the coca business and to prevent farmers from selling their base paste to anybody else other than the CDF. Withdrawal and confrontation were used by the local peasantry, however, to challenge the authority of the CDF in this region as they felt it did not meet their expectations.

Navigating Conflicting Grassroots’ Pressures

That does not mean that demands were always met satisfactorily. In July 2022, the president of the agrarian union Asocordillera, was captured in the corregimiento Footnote 7 of Los Robles in Suárez by armed men in a pickup truck. A few days later, his lifeless body was found nearby, in Betulia.Footnote 8 He had been shot dead by the FARC-EP on charges of rape. According to people close to the case, he had been having “an affair” for a few weeks with an underage girl until she denounced him to the insurgents for sexual abuse (the word “affair” was used by participants to refer to this case of statutory rape). This sent shockwaves through the union, who appeared to have had a sympathetic relationship with the rebels. Members of the Asocordillera directive tried to save his life and told him that he should admit the fault, even go to jail, but he denied any wrongdoing. The interviewees complained that, in these cases, the prosecutor’s office always let the culprit go scot-free, so people looked to the rebels to administer justice (Ca-01-f; Ca-01-m; Ca-02-f; Ca-03-f 2022). Members of the union who were interviewed thought that there should be other alternative punishments rather than execution in the case of rape: “Some people said he messed up, because the [FARC-EP] have their rules, but we do not want this to happen again. Death is no solution. We need to instead prevent sexual violence” (Ca-02-f 2022). After this, the reconstituted FARC-EP in Suárez stepped up efforts against widespread violence against women, as was clear in their banners declaring “no tolerance of any form of violence against women” (Figure 4).

Figure 4. FARC-EP Banner Denouncing Violence against Women in the Village of Floresta (Suárez, Cauca) (Image by José A. Gutiérrez).

Figure 5. Instructions to Drivers on the Road to Betulia, Cuárez (Cauca). Keep your Windows Down, Don’t Wear a Helmet, Bring your Letter of Recommendation and Vehicle Documents. Peddlers from Outside the Area Prohibited. Note the Fighter Depicted is an Afro-Colombian Woman (Image by José A. Gutiérrez).

However, the contention around the case was heightened by the apparent disparity in enforcement, as there had been, after this, two other cases of sexual violence involving underage girls, “but the same thing didn’t happen, and one wonders why” (Ca-02-f 2022). In the two other cases, the suspected culprits were members of the local indigenous cabildo, a legally sanctioned indigenous community organization. Shortly after the shock execution of the president of Asocordillera, another suspected abuser was caught by the reconstituted FARC-EP. Because of the recent execution, the community intervened so they didn’t kill him, to which the rebels replied by saying that then the JAC should decide about the case.

The unwillingness by the reconstituted FARC-EP to take full authority over the situation left space for the community to take a more autonomous role. Yet this revealed the disagreements within the community itself. The community leaders were themselves divided about the proper course of action. “What do you do? His family were opposed to his execution, the victim demanded death penalty, and what about us? […] we need regulations to avoid this kind of problems, because the JAC cannot decide over the life of people,” vented one frustrated leader (Ca-02-f 2022). While this debate raged, the indigenous authority came to claim the suspect as member of the cabildo,Footnote 9 and therefore subject to the indigenous jurisdiction. This was unsatisfactory to the JAC, whose members viewed the cabildo as being too lenient with rapists: “they said they would do a traditional trial […] and in the end, they only gave him a traditional medicine. They didn’t do anything!” (Ca-02-f 2022). The disparity in treatment between a member of their own community—the president of Asocordillera—and a member of the indigenous community, led members of the peasant community to denounce the reconstituted FARC-EP as inconsistent, with one of them saying “maybe not the death penalty, but they should have the same standards for us and for them” (Ca-01-m 2022). Otherwise, they feared, people may start joining the cabildo and not the agrarian union, because there “[molesters] are unperturbed, and then how many girls will be raped? This needs to be righted because that person is out there so he can keep abusing others” (Ca-02-f 2022).

Confronted with cases like this, communities are rarely homogenous. In this case, the reconstituted FARC-EP was facing conflicting demands and pressure by the peasant and the indigenous leaders. Constant pressure from groups such as EPL and Segunda Marquetalia meant the reconstituted FARC-EP had to be careful not to alienate local communities. In the end, despite the peasant community’s dissatisfaction, the reconstituted FARC-EP appeared to agree to the demands made by the indigenous leaders to respect their jurisdiction. The rebels had to negotiate their application of social regulation between their own ideas of justice and the different demands made by the communities, as well as the security pressures on their newly acquired control of the territory.

Yet despite the dissatisfaction with some rulings, the reconstituted FARC-EP still offered a stark comparison to the official justice system which was perceived as ineffectual at meeting community demands. Talking about the Suárez case involving sexual abuse, participants vented their frustration during the interview: “The thing is, the attorney office doesn’t do a thing. You denounce […] but the State doesn’t do anything. There was a crime, and we are asked for ever more evidence, otherwise, they suspect us of libel” (Ca-01-m 2022).

One Law for All: The Rebel Complaint Box

Community demands for accountability also pushed the reconstituted FARC-EP to submit their own combatants to justice by the JAC in case of transgressions. While in Llanos del Yarí, Caquetá, there was consensus that there had been a significant improvement on disorderly behavior in the community,Footnote 10 in Suárez, Cauca, participants agreed that while the reconstituted FARC-EP had put much needed control over issues such as disorderly behavior and gun control in bars, their own militias had been involved at first in cases of disorderly behavior, where “sometimes [ed. the FARC-EP], of all people, leave the bars open beyond licensing hours and turn up the music volume in the bars” (Ca-01-f 2022). The rebels ended up paying the corresponding fine to the JACs and since appeared to take measures to avoid the situation happening again (Ca-01-f 2022).

One important element that distinguished the FARC-EP from other armed factions is the sense of discipline within its ranks. This is an important aspect that the reconstituted FARC-EP had tried hard to reproduce. This had not been easy, especially in places like Cauca compared to Caquetá, where “they were starting again from scratch, with many who were not well trained” (Ca-03-f 2022). These inexperienced young recruits had led to issues in Suárez, according to a community leader:

There were problems with the [ed. FARC-EP] because there are too many young guys […] so at parties, they started shooting in the air, and the youth were out of control. We put the complaint, and they said this was not acceptable. It was specifically the JAC in Playa Rica that requested control over this disorder. (Ca-02-f 2022)

However, “they put a stop to that. Each shot into the air is fines of COP$1 million, COP$2 million after that. Half goes to the JAC, half goes to them […] they have always paid when their guys have shot volleys into the air” (Ca-01-f 2022).

In Caquetá there was notably more experience in the group, where the average rank-and-file combatant seemed better prepared and with a longer trajectory as an insurgent than the comparatively younger and less experienced guerrillas in Cauca. Indeed, the late Jhonier, the main commander in Cauca between 2018–2022, was sent explicitly from Caquetá to command the guerrillas in Cauca and improve their discipline.

However, the accountability structures of the reconstituted FARC-EP in Cauca appeared responsive to the demands by community members. Participants in Cauca mentioned that “they respect internal rules, community processes” (Ca-01-f 2022), “there has been respect, and a two-way dialogue” (Ca-01-m 2022); “they started to […] grow, and they organized meetings with the JAC. In Aguabonita [Suárez], Wilson [ed. Mayimbú, FARC-EP commander] said that their idea was to work with the JACs […] and decisions to be more participatory. They respect a lot the JACs” (Ca-02-f 2022).

In comparison to Caquetá and Cauca, the community in Putumayo found itself much more restricted in the demands they could make. With the CDF in Putumayo, the dynamic was different, because “they changed the coexistence norms […] when the [FARC-EP] organized a meeting, people had a chance to talk, there was dialogue. With these guys there is never any agreement […] they fine the communities on meetings as if they were the authority” (P-01-m 2022). Still, there is a chance to hold some of their commanders accountable. After an incident where a combatant from the CDF was found to be taking ID numbers in the registers of coca production and causing widespread discomfort, “that guy was demoted from his post, because he should not have done that” (P-01-m 2022). The CDF, though notably different than the FARC-EP, echoed elements of its legalistic approach to coexistence and internal norms, showing itself, although in a limited fashion, responsive to the community’s demands.

Community members in Cauca also put forward demands on the regulation of prostitution, but participants complained that the changes of commanders affected the agreements between the insurgents and the community. For example, one participant expressed her disagreement with the fact that the reconstituted FARC-EP had allowed prostitution in one bar in the village of Playa Rica in Suárez. According to her, before 2016, the FARC-EP had banned prostitution: “we tried to reach the same agreement with one commander, but then there was a change in command, and the new one allowed prostitution” (Ca-02-f 2022). To further emphasize her point, the same participant mentioned that when there is a fundraiser in one village, the shops in all the region should close; this was respected by the previous commander, but not by the current one.

The legacy of previous FARC-EP norms bolstered this individual’s sense of outrage in comparing current approaches to establishing order. It also indicates the limitations on demands for regulation by the community, as the rebels’ internal processes and structure in this case. The reconstituted FARC-EP had to operate, after the fragmentation caused by demobilization, in a more decentralized way than the previous iteration of the FARC-EP. Therefore, while demands could be made and sometimes met, the communities would still face barriers in the operational exigencies and personal preferences of rebel leadership of the post-demobilization reconfiguration.

Filling the Governance Gap

The interregnum between the FARC-EP demobilization and its reconstitution, however, did not only lead to a demand for the FARC-EP’s return. In many territories, communities took initiative themselves to fill in the gap that the rebels had left behind, as the community in Argelia had to do when the FARC-EP handed back the informer to the community to decide. However, autonomous action by the community was only taken at the time of fieldwork in the area where the FARC-EP successfully reconstituted in Suárez,Footnote 11 indicating how community agency is not only shaped by the responsiveness and capability of armed groups, but more importantly, by the local social-political configurations.

Peasant guards (guardias campesinas) in Suárez were created by initiative of agrarian unions to provide a community-led alternative to the public force in the absence of insurgents: “the guards are the backbone of the peasants’ union. It was created out of need […] for security and the environment” (Ca-02-f 2022). Given the sudden absence of FARC-EP enforcement and the lack of satisfactory alternatives provided by the state, members of the community took action to establish protection mechanisms of their own. The model for these peasant guards were already existing indigenous and Afro-Colombian guards (Chaves et al. Reference Chaves, Aarts and van Bommel2020) but they, instead, had a close relation to the JACs and agrarian unions.

Yet, even as a reconstituted FARC-EP group emerged in Suárez, these peasant guards did not disappear. Instead, they appeared to keep a relatively autonomous role, while reflecting the growing insecurity of the post-demobilization landscape. In Suárez, for example, local leaders somehow participate in the shielding mechanism established by the FARC-EP Jaime Martínez Front in vetting entry for non-recommended outsiders. The JACs in the region provide letters of recommendation for people moving across the territory and the FARC-EP then enforce this form of control, participating thus in the co-construction of shielding (Figure 5). As one member explained “one way or another we have to have some relationship with the FARC because we are in the same territory, we face the same threats coming from other groups threatening our leaders” (Ca-02-f 2022).

This relationship was explicitly seen as co-constituted: “our goals are very similar, if not the same, and if they give us some help, we reply in kind with the peasant guards, because we help with territorial control. If either see anything strange, we cover each other’s backs” (Ca-01-f 2022). The peasant guards, for instance, also mobilized against anti-narcotics operations by police and army. “Here we have had no eradication nor fumigations,” say participants in Cauca, “the indigenous, the black, the peasant, all come together to defend each other” (Ca-03-f 2022). This demonstrates a contrast to the community’s engagement with the CDF in Putumayo, where—as previously discussed—the CDF’s order that the communities oppose anti-narcotics operations was met with discontent because the CDF were unwilling to provide backing.

The peasant guards would also be involved in enforcing accountability from the rebels. In the example previously discussed of combatants in Suárez becoming disorderly and using their weapons, the peasant guard played a role in ensuring the reconstituted FARC-EP took appropriate action in disciplining their own young and inexperienced troops. According to a community leader and herself a member of the peasant guard, the FARC-EP:

in their regulations, they cannot attend a bar with guns, but some do not comply sometimes. If there’s an event, the peasant guard checks them, and if they are armed, they can’t go in, so they walk away, leave the gun behind and then come back. […] When we have had to tell them a few truths, we have done so, and there has been respect […] they have punished according to the nature of the trespass, and they had corrected this, for they listen to the communities. (Ca-03-f 2022)

The reconstituted FARC-EP therefore not only had to listen and respond to the demands by the community on what order and adjudication should look like based on previous experiences of rebel rule: the communities themselves used that blueprint to become more active in enforcing these governance priorities.

The legacy of rebel governance, especially in the face of the post-demobilization disorder, could also mobilize community opposition against new peace talks. In Cauca, a local leader expressed anxiety at the possibility of a new demobilization based on his experience with the last one:

with the new talks we have uncertainty coming […] what they do is a sacrifice, and we have to appreciate the effort they do to defend our territory. I am very grateful to them, because who knows what groups would have arrived here, and we have support as leaders […] I survived paramilitarism, and I don’t wish that on anybody. But we don’t know what’s going to happen with these talks […] if it wasn’t for them, maybe many of us wouldn’t even be here. (Ca-01-m 2022)

Therefore, rural communities feel they have as much reason to be concerned with another wave of demobilization as members of an armed group. In Caquetá, participants insisted that they will not allow the FARC-EP to be demobilized again in the way they did before without an alternative for public order being explicitly discussed in the context of the latest peace agreement (C-01-f 2022). This hints at potential future actions being taken by the communities themselves in preserving the existing order against the uncertainty of future disorder.

Nevertheless, even in Cauca the peasant guards had limitations. They sometimes struggled with issues of social regulation, in distinguishing serious crime as opposed to just disorderly behavior. The FARC-EP’s demobilization and the slow and inconsistent return of rebel order has left communities to reflect on what is their role in participating and actively enforcing the order they had come to expect and demand from the FARC-EP. Community leaders were reluctant to take full responsibility on matters of rape and serious crimes, instead expecting the reconstituted FARC-EP to take action, as mentioned by leaders in Suárez:

Who has finally the responsibility? The union? The FARC? The families? The JAC? […] it is preferable to prevent sexual violence […] I do not want people being punished with death, but I do not want others pandering to this behavior either. We need to regulate to avoid these conflicts. But, in any case, a JAC should not be deciding the lives of people. (Ca-02-f 2022)

This incident is representative of the dilemmas and challenges faced by organized communities in the post-demobilization scenario.Footnote 12 State institutions are rarely trusted or considered to be inefficient. Communities may be organized and have clear rules, and some degree of enforcement, but some may also struggle to accept all the characteristics of previous FARC-EP justice—at times bloody—in new order configurations, while for others it may not be harsh enough.

Conclusion

No one takes advantage of one another. They do not take us for granted, and we aren’t idiots. If we need them, they will be there. We have learned to live with them, and they with us.

(Ca-01-m 2022)

Rebel governance leaves deep marks in territories under protracted rebel rule, which are felt even after demobilization and after active attempts to dismantle this “conflict order,” because its very construction is often dependent on the involvement of the community who remains. By analyzing community responses to post-demobilization insecurity through a relational framework—that identifies how communities structure their expectations in relation to their past experiences of rebel governance—we can better understand how order post-demobilization is not solely driven by the choices of reconstituted rebel groups, but co-constructed with the communities, even if this happens with various degrees of asymmetry between both actors. Yet, in the aftermath of demobilization, communities are not passive to new armed groups attempting to impose order in the territory. Instead, their experiences set their expectations for what order is meant to look like and what steps they take to build it.

However, while communities across all three cases were active in making demands of new and reconstituted armed actors, we observe that communities only took direct action in addressing governance gaps, at the time when fieldwork was conducted, in Suárez. This appears partly as a response of the peasantry to the actions of neighboring communities in the region (Afro-Colombians and indigenous), to the higher level of grassroots organization in this region compared to the other regions, but also to the relative inexperience of the re-established FARC-EP compared to the FARC-EP in Caquetá. The group, attempting to recapture the legitimacy and position of the FARC-EP prior to demobilization, and facing a highly organized community with significant previous experience with the FARC-EP, was willing to allow the community to take a more active role where they were unable to meet all the expectations for security provision. However, community expectations and demands based on previous experience with the FARC-EP were apparent in all three cases, even where the post-demobilization armed group departed more drastically from the pre-2016 FARC-EP form of governance, as was the case of the CDF in Putumayo.

The capacity of communities to put pressure on armed actors depends on a number of factors that are beyond the scope of this article, although it is apparent that the volatility of the post-demobilization landscape means that even armed groups operate in very uncertain settings and ties with local communities can provide a degree of stability. We believe this is a starting point to further explore shifts in rebel governance in periods of transition, such as post-demobilization and the rise of new armed orders. These new configurations of order are shaped by the strength of local organizations and the degree of consolidation of rebel groups pre- and post-demobilization, the ideology of the post-demobilization armed groups towards governance, and socio-political characteristics of each region.

Additionally, these expectations and actions also operate in complex social settings. We know from previous research (e.g., Masullo Reference Masullo2021) that normative and ideological factors affect responses to conflict and armed actors among community leaderships, but this is also affected by cultural and class differences. All the case-studies here are of relatively homogenous communities of peasant smallholders. We also do not examine the post-demobilization dynamics of conflict of indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities. Although in Suárez, Cauca, there are strong Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities, our research was limited to the peasant communities. Yet the complexity of how the FARC-EP adjudicated the case of the alleged rapists indicates that different ethnic authorities may have different relational priorities with rebel governance. How are expectations and demands shaped in indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities as compared to peasant communities? Understanding the dynamics in these ethnic communities is paramount to have a more complete picture of the contradicting pressures and demands shaping post-demobilization security in multi-cultural settings. Likewise, we show that even these peasant communities are not all homogenous. Exploring differences between the leadership and the broader community or understanding class differences, for instance, between landless peasants, smallholders, traders, and business owners, and how their positionality affects experiences and therefore expectations, as well as demands and actions, is another gap to be addressed in future research. Finally, although we had a fair representation of women among participants, an in-depth gender analysis will be required when future data is collected.

As scholars interested in the effects of rebel governance, we argue that we are remiss to ignore the role communities play in constructing new forms of orders: communities have their own expectations for governance, regardless of the rebels’ own goals, and their demands and actions will reflect these. As the epigraph of this section implies, members of the community are aware of the delicate relation between the armed group and the community in maintaining order; it is not necessarily one of unconditional support, but part of a learned, at times pragmatic, relationship (see Sagherian-Dickey and Voyvodic Reference Sagherian-Dickey and Voyvodicforthcoming). Past experiences of rebel governance provide communities a blueprint for what resembles order: not necessarily identical to what came before, but built on its foundations by other armed groups and the community themselves.

The signing of a peace accord and subsequent demobilization may prove more disruptive than constructive to this order, leading to demands for remobilization and providing a base of support to new or remobilized rebels. This research highlights the importance of factoring in the legacy of rebel governance and the agency of heterogenous local communities into peacebuilding strategies. What is to be done in post-demobilization scenarios to make sure that these security demands are met or re-channeled in ways which are both appropriate to the communities and to the wider efforts for peacebuilding remains at the heart of future research efforts.

Acknowledgments

This work has been partly funded by the Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles through the Université Libre de Bruxelles and the ESRC project “Getting on with it” at the University of Bristol. We would like to thank Silvana Toska, Cyanne Loyle, and participants in the Rebel Governance and Criminal Governance workshop (March 24, 2023) for their constructive feedback. Finally, we are indebted to the research participants for their frankness and openness to discuss with us these issues, and for their generosity with their time.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.