Introduction

Autism is clinically defined as a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by social communication differences, sensory sensitivities, and difficulties with behavioral and cognitive flexibility (APA, 2013). It is also conceptualized as a form of neurodivergence, representing natural differences in human minds (Chapman & Botha, Reference Chapman and Botha2023). About 1 in 100 children globally is estimated to receive an autism diagnosis (Zeidan et al., Reference Zeidan, Fombonne, Scorah, Ibrahim, Durkin, Saxena and Elsabbagh2022) and reported prevalence can differ across studies (Roman-Urrestarazu et al., Reference Roman-Urrestarazu, van Kessel, Allison, Matthews, Brayne and Baron-Cohen2021). Complex referral pathways and lengthy waits for diagnostic assessment often translate into untimely or incorrect diagnosis (NHSE, 2023), probably impacting the accuracy of prevalence estimates.

Autistic children and young people (CYP) experience high rates of co-occurring mental health difficulties (Simonoff et al., Reference Simonoff, Pickles, Charman, Chandler, Loucas and Baird2008), contributing to considerable long-term negative effects on health and quality of life (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Kassee, Besney, Bonato, Hull, Mandy and Ameis2019). An increasing body of research is highlighting the impact mental health difficulties can have on various aspects of life, including education, quality of life, behavior, family, work, and independence beyond what is linked to autism (Adams, Clark, & Keen, Reference Adams, Clark and Keen2019a; Adams & Emerson, Reference Adams and Emerson2020, Reference Adams and Emerson2021; Adams, Young, Simpson, & Keen, Reference Adams, Young, Simpson and Keen2019b; Den Houting, Adams, Roberts, & Keen, Reference Den Houting, Adams, Roberts and Keen2020; Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Stanfield, Watt, Barry, Day, Cormack and Melville2018). Disentangling mental health difficulties from autistic traits can be difficult due to poor clinician knowledge of autism, diagnostic overshadowing, and a lack of validated measures, resulting in challenges and delays to diagnosis and, subsequently, a lack of or ineffective mental health support (Adams & Young, Reference Adams and Young2021; Brede et al., Reference Brede, Cage, Trott, Palmer, Smith, Serpell and Russell2022; Hus & Segal, Reference Hus and Segal2021; Maddox et al., Reference Maddox, Crabbe, Beidas, Brookman-Frazee, Cannuscio, Miller and Mandell2020). There is preliminary evidence for the feasibility and effectiveness of standard and adapted psychological interventions for anxiety and mood-related outcomes for autistic CYP (Linden et al., Reference Linden, Best, Elise, Roberts, Branagan, Tay and Gurusamy2023). Meanwhile, pharmacological interventions trialed in this population have obtained mixed results when prescribed for mental health symptoms (Deb et al., Reference Deb, Roy, Lee, Majid, Limbu, Santambrogio and Bertelli2021), and clinical guidelines have recommended caution when prescribing them for CYP, especially without concurrent psychological interventions (NICE, 2021).

Mental health care requires tailoring for autistic CYP, as standard care can fail to meet their preferences and needs (Dickson et al., Reference Dickson, Lind, Jobin, Kinnear, Lok and Brookman-Frazee2021; Lickel, MacLean, Blakeley-Smith, & Hepburn, Reference Lickel, MacLean, Blakeley-Smith and Hepburn2012; NICE, 2021). Mental health services may attempt to address autistic people's needs through implementing bespoke interventions specifically developed for this population, adapted standard interventions, and/or changes to service delivery overall. Adaptations are needed to make the overall experience of contact with services more accessible and acceptable, as well as to ensure that the structure, delivery, and content of interventions are appropriate for autistic young people. These adaptations should also be in line with the person's developmental age and stage (NICE, 2021). Adaptations that have been recommended include offering shorter or longer appointments, incorporating visual means to facilitate discussion, and changing the physical environment to accommodate sensory preferences (National Autistic Society, 2021). However, parents often report lack of clinician knowledge/expertise regarding autism and an inability of mental health services and clinicians to tailor their support to autistic CYP (Adams & Young, Reference Adams and Young2021). Failure to embed adaptations can result in distress, disengagement from services, and reduced help-seeking (Benevides et al., Reference Benevides, Shore, Palmer, Duncan, Plank, Andresen and Coughlin2020; Brede et al., Reference Brede, Cage, Trott, Palmer, Smith, Serpell and Russell2022; Crane, Adams, Harper, Welch, & Pellicano, Reference Crane, Adams, Harper, Welch and Pellicano2018). This can negatively impact the wellbeing of families as well as of CYP, increasing carer stress (Read & Schofield, Reference Read and Schofield2010).

More research is needed to explore strategies used in mental health care settings for autistic CYP to guide clinical practice and future research in this area so that needs for effective mental health care can be better met. Thus, this systematic review aimed to identify and examine strategies used to improve mental health care for autistic CYP and, if possible, conduct a meta-analysis, addressing the following research questions:

1) What strategies, including service adaptations, initiatives to detect autism, and bespoke and adapted interventions, have been used to improve mental health care for autistic CYP?

2) What is the acceptability and feasibility of strategies to improve mental health care for autistic CYP?

3) What is the effectiveness of strategies to improve mental health care for autistic CYP?

Methods

This systematic review was conducted by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Mental Health Policy Research Unit, as part of their research program aimed at building evidence to inform policy (MHPRU, n.d.). The protocol, developed in collaboration with a working group, comprising lived experience researchers, academics, clinicians, and policy experts with personal/professional expertise of autism and/or review methodology, was pre-registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022347690). We followed the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow and Moher2021). See online Supplementary Table S1 for a PRISMA checklist.

This systematic review reports the findings regarding autistic CYP and mixed samples of adults and CYP when only combined outcomes were available. A separate systematic review was conducted regarding autistic adults (Loizou et al., Reference Loizou, Pemovska, Stefanidou, Foye, Cooper, Kular and Johnson2023).

Search strategy

A systematic literature search using keywords and subject headings relating to autism and mental health problems and services/treatments was conducted in three electronic databases (Medline, PsycINFO, CINHAL) and two pre-print servers (medRxiv and PsyArXiv) for papers published between 1994 and July 2022. The date range was chosen to cover the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fourth (DSM-IV) and fifth (DSM-5) edition periods, in line with International Classification of Diseases 10th and 11th edition (ICD-10/11). We searched for additional eligible papers through checking the reference lists of identified relevant systematic reviews and a call for evidence from experts including academics and lived experience networks. Online Supplementary Tables S2–S4 present the full search strategy.

Screening

The selection strategy was piloted, and reviewers conducted the title and abstract screening, using Rayyan (Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz, & Elmagarmid, Reference Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz and Elmagarmid2016), with a random 10% of records independently reviewed in duplicate (97.98% agreement). Full texts were screened independently in duplicate in line with Cochrane guidance (Higgins & Thomas, Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2023). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer and the working group.

Eligibility criteria

Population

Papers eligible for inclusion included CYP or mixed samples of CYP and adults (aged 18+ years) where data from autistic CYP could not be disentangled. Participants with an autism diagnosis or who suspected they were autistic or were identified by clinicians as potentially autistic were eligible. Views of carers and clinicians about mental health interventions for autistic CYP were also eligible. Papers with samples including both autistic and non-autistic people were excluded, unless data from autistic people could be isolated, or papers explored detection of autism. There was no minimum sample size required for inclusion.

Strategies

We included papers that assessed any strategies/adaptations to improve mental health care for autistic CYP, including: (1) bespoke mental health interventions originally developed for autistic people, (2) adaptations to existing mental health interventions, and (3) service-level strategies (e.g. strategies to detect autism) within mental health services and/or in mental health care delivered in primary care. Authors were contacted if the setting or the intervention's eligibility and classification as adapted/bespoke were unclear. Papers were eligible regardless of the presence and type of comparison group.

Outcomes

Eligible outcomes were any quantitative or qualitative measure of feasibility (e.g. recruitment adherence, retention rates), service use (e.g. engagement), acceptability of care, experience of and satisfaction with care, and/or quantitative measure of mental health, detection of autism, quality of life, service use, and social outcomes (e.g. social functioning) at end of treatment or follow-up. Papers measuring only physical health outcomes were excluded.

Study types

All study designs and service evaluations were eligible for the first and second research question, and only empirical quantitative studies were eligible for the third research question. Reviews, case studies without group analysis, commentaries, book chapters, editorials, letters, and conference abstracts were excluded.

Data extraction

Reviewers extracted data including study design and aims, setting, sample size, participant characteristics (e.g. age, ethnicity, diagnosis), outcome measures, strategies and adaptations (e.g. type, brief description, parent/carer involvement), and relevant findings (feasibility, acceptability, effectiveness). The data extraction form was first piloted on 10% of the eligible papers, discussed with the working group and updated accordingly. The extracted data were checked by at least one other reviewer, thus at least two reviewers reached consensus of the extracted information. Two researchers independently double-extracted raw end-of-treatment (EOT) outcome data (mean, standard deviation, sample size per group) for the meta-analyses.

Autism-inclusive research assessment

Lived experience researchers in the working group observed that relevant studies might not have been sufficiently inclusive of autistic experiences (e.g. allowing non-verbal communication, using straightforward language, using measures valid for autistic people). Therefore, a lived experience researcher (RRO) developed criteria derived from existing literature and personal experience, labeled the Autism-Inclusive Research Assessment (AIRA), to measure the extent of autism-inclusive practices in research. The criteria were first used in our systematic review regarding autistic adults (Loizou et al., Reference Loizou, Pemovska, Stefanidou, Foye, Cooper, Kular and Johnson2023) but were also piloted on papers with CYP in the present review to determine applicability. The five assessment criteria for the AIRA are: (1) reported lived experience involvement in the design, conduct, or write-up of the paper; (2) reported adjustments made to data collection process for papers with qualitative elements (Benford & Standen, Reference Benford and Standen2011); (3) reported adjustments made to data collection tools for papers with quantitative elements (Nicolaidis et al., Reference Nicolaidis, Raymaker, McDonald, Lund, Leotti, Kapp and Zhen2020); (4) reported adaptations or validity of relevant outcome measures for autistic people for papers with quantitative elements; (5) if the evaluated intervention/strategy in papers with quantitative elements was perceived to contain some focus on masking/changing people's autistic traits, which might have not inherently caused distress or worsened quality of life (Chapman & Botha, Reference Chapman and Botha2023), rather than solely focusing on improving mental health. Two researchers extracted all relevant data, and a lived experience researcher was involved as second assessor of the final criterion.

Quality and certainty of available evidence

Reviewers assessed study quality using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Fàbregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo, Dagenais and Pluye2018). All scores were checked by a second reviewer and consensus was reached. Reviewers independently double-evaluated the strength of evidence about effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxiety synthesized via meta-analyses using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system (Guyatt et al., Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Vist, Kunz, Falck-Ytter, Alonso-Coello and Schünemann2008). Additionally, the strength of the narratively synthesized effectiveness evidence of all interventions/strategies was double-evaluated using GRADE adapted for narrative synthesis (Murad, Mustafa, Schünemann, Sultan, & Santesso, Reference Murad, Mustafa, Schünemann, Sultan and Santesso2017).

Evidence synthesis

We conducted a narrative synthesis following Economic and Social Research Council guidelines (Popay et al., Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai, Rodgers and Duffy2006). With the input of lived experience researchers, the identified intervention-level and service-level adaptations were grouped into categories and sub-categories according to shared commonalities. This was informed by our previous review relating to autistic adults (Loizou et al., Reference Loizou, Pemovska, Stefanidou, Foye, Cooper, Kular and Johnson2023) and refined based on the current included studies.

The included papers were grouped into service-level strategies or interventions to synthesize the extracted outcome data. Service-level strategies were categorized based on their focus. Different interventions were characterized based on type, format, bespoke/adapted therapy, and focus. To distinguish between bespoke and adapted interventions, we relied on authors' descriptions in the papers or their responses when more clarification was needed. We considered interventions to be bespoke (e.g. Facing Your Fears – FYF) if authors reported they were originally designed for autistic people. Authors themselves were primarily involved in developing these interventions/manuals for their study and they were used unmodified. These were considered bespoke interventions regardless of whether they had been based on mainstream CBT or mindfulness principles. We considered the interventions as adapted if authors reported testing adapted existing interventions not originally designed specifically for autistic people. The same approach was used to classify modified versions of interventions originally designed for autistic people, e.g. changed original mode of delivery for FYF to telehealth delivery or developmentally modified version of FYF for use with adolescents.

The extracted data for the AIRA were synthesized descriptively. The feasibility/acceptability findings were synthesized from all contributing study types. We synthesized the effectiveness findings, placing greater importance on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized controlled trials making contemporaneous comparisons rather than before-and-after comparisons. Upon inspection of the included papers, a meta-analysis was deemed appropriate, as a large subset of pilot RCTs and RCTs appeared to be sufficiently homogenous in outcome, intervention, and population. Three meta-analyses were conducted for ratings respectively by children/care recipients, parents/carers, and clinicians to examine whether bespoke/adapted CBT for anxiety is superior to any control condition (active and non-active) in reducing anxiety symptoms at EOT. Separate analyses were performed, as previous meta-analyses have found differences across raters (Sharma, Hucker, Matthews, Grohmann, & Laws, Reference Sharma, Hucker, Matthews, Grohmann and Laws2021; Sukhodolsky, Bloch, Panza, & Reichow, Reference Sukhodolsky, Bloch, Panza and Reichow2013).

The R-package ‘metafor’ (Viechtbauer, Reference Viechtbauer2010) was used to calculate the standardized mean difference (SMD), correcting for small sample sizes (Hedges' g) between groups at EOT. Effect sizes were significant if p < 0.05, and were tentatively interpreted as small (0.2), medium (0.5), and large (0.8) (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988). Random-effects models were used to account for variability in the average effect size across papers (Hedges, Reference Hedges1992). Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran's Q (significant if p < 0.05) (Cochran, Reference Cochran1954) and Higgins' I (25% = low, 50% = moderate, 75% = high) (Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003).

Sensitivity analysis was performed by removing outliers from the models. Where there were sufficient studies (k > 10), meta-regression analyses were conducted to examine the moderating effects of type (adapted, bespoke) and format (individual, group, combined) of CBT on effectiveness. Funnel plots were visually inspected, and Egger's test (significant if p < 0.05) (Egger, Smith, Schneider, & Minder, Reference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder1997) was conducted to test for publication bias.

Results

Study selection

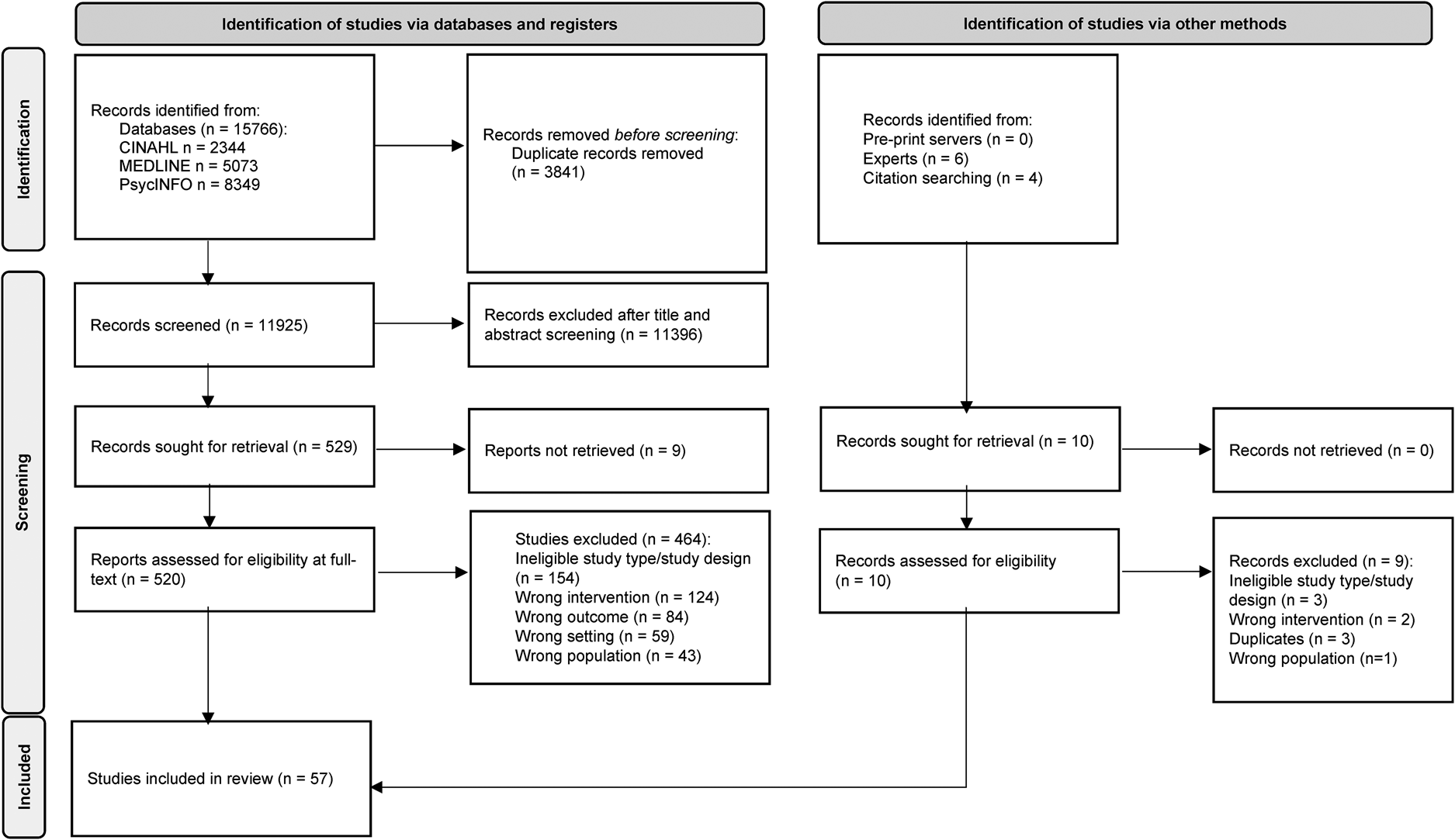

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram. In total, 57 papers were eligible for inclusion and a full list of studies excluded at full-text screening with reasons is presented in online Supplementary Table S5.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart.

Study characteristics

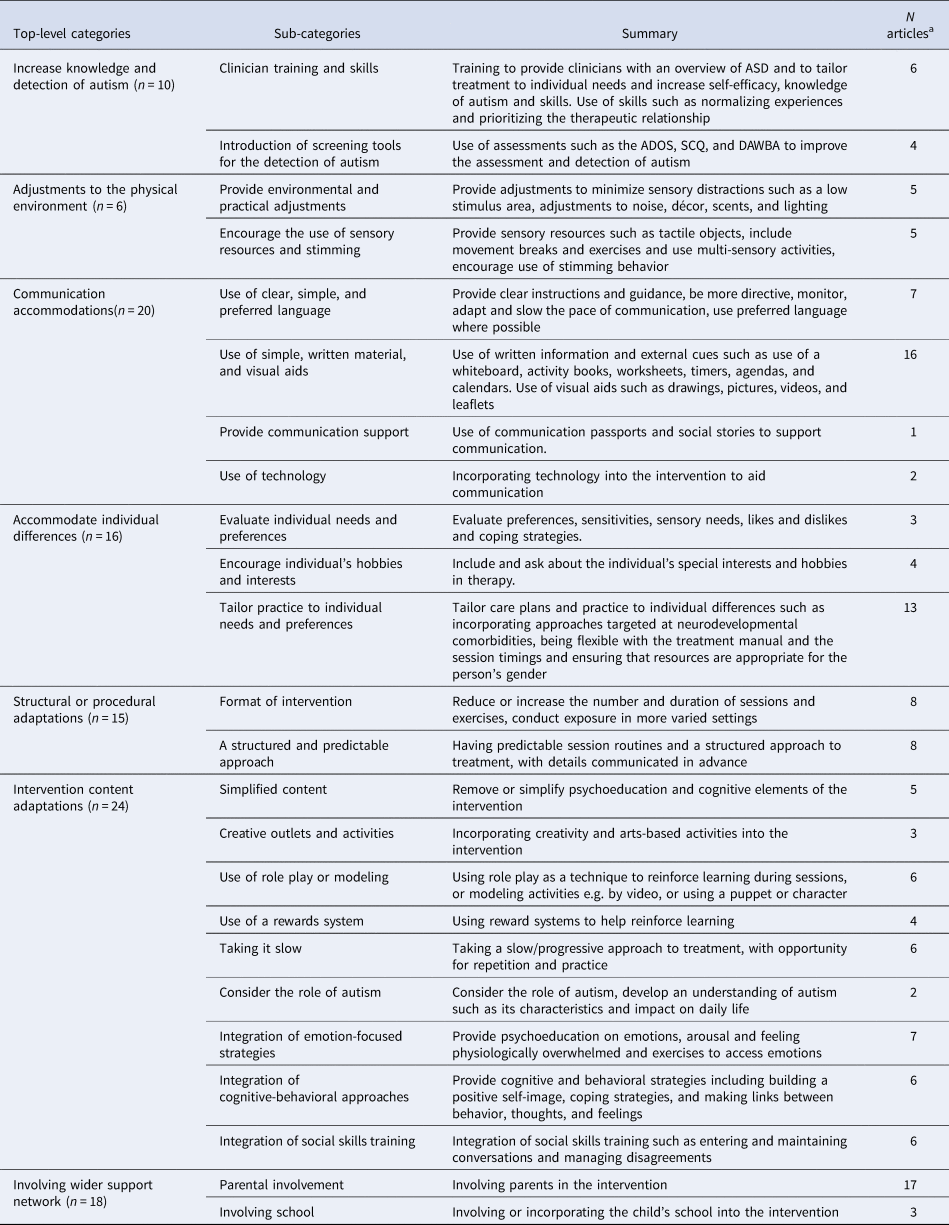

Of the 57 papers, 23 were RCTs (Chalfant, Rapee, & Carroll, Reference Chalfant, Rapee and Carroll2007; Cook, Donovan, & Garnett, Reference Cook, Donovan and Garnett2017; Factor et al., Reference Factor, Swain, Antezana, Muskett, Gatto, Radtke and Scarpa2019; Fujii et al., Reference Fujii, Renno, McLeod, Lin, Decker, Zielinski and Wood2013; Kilburn et al., Reference Kilburn, Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Arendt and Thomsen2020; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016; Maskey et al., Reference Maskey, Rodgers, Grahame, Glod, Honey, Kinnear and Parr2019b; McConachie et al., Reference McConachie, McLaughlin, Grahame, Taylor, Honey, Tavernor and Le Couteur2014; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Chowdhury, White, Reynolds, Donald, Gahan and Press2017; Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Culhane-Shelburne, & Hepburn, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Culhane-Shelburne and Hepburn2012a; Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Moody, Grofer Klinger, Keefer, Duncan, O'Kelley and Blakeley-Smith2018; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Jassi, Fullana, Mack, Johnston, Heyman and Mataix-Cols2013; Santomauro, Sheffield, & Sofronoff, Reference Santomauro, Sheffield and Sofronoff2016; Scarpa & Reyes, Reference Scarpa and Reyes2011; Sofronoff, Attwood, & Hinton, Reference Sofronoff, Attwood and Hinton2005; Storch et al., Reference Storch, Arnold, Lewin, Nadeau, Jones, De Nadai and Murphy2013, Reference Storch, Lewin, Collier, Arnold, De Nadai, Dane and Murphy2015, Reference Storch, Schneider, De Nadai, Selles, McBride, Grebe and Lewin2020; Sung et al., Reference Sung, Ooi, Goh, Pathy, Fung, Ang and Lam2011; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Moody, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Hepburn, Keefer and Reaven2018; White et al., Reference White, Ollendick, Albano, Oswald, Johnson, Southam-Gerow and Scahill2013; White, Schry, Miyazaki, Ollendick, & Scahill, Reference White, Schry, Miyazaki, Ollendick and Scahill2015; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Ehrenreich-May, Alessandri, Fujii, Renno, Laugeson and Storch2015), of which 11 were pilot RCTs (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Donovan and Garnett2017; Fujii et al., Reference Fujii, Renno, McLeod, Lin, Decker, Zielinski and Wood2013; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016; Maskey et al., Reference Maskey, Rodgers, Grahame, Glod, Honey, Kinnear and Parr2019b; McConachie et al., Reference McConachie, McLaughlin, Grahame, Taylor, Honey, Tavernor and Le Couteur2014; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Chowdhury, White, Reynolds, Donald, Gahan and Press2017; Santomauro et al., Reference Santomauro, Sheffield and Sofronoff2016; Scarpa & Reyes, Reference Scarpa and Reyes2011; Storch et al., Reference Storch, Schneider, De Nadai, Selles, McBride, Grebe and Lewin2020; White et al., Reference White, Ollendick, Albano, Oswald, Johnson, Southam-Gerow and Scahill2013, Reference White, Schry, Miyazaki, Ollendick and Scahill2015) and two were also mixed-method studies including and RCT (Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016; McConachie et al., Reference McConachie, McLaughlin, Grahame, Taylor, Honey, Tavernor and Le Couteur2014), three were non-randomized controlled trials (Hepburn, Blakeley-Smith, Wolff, & Reaven, Reference Hepburn, Blakeley-Smith, Wolff and Reaven2016; McGillivray & Evert, Reference McGillivray and Evert2014; Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Nichols, Dasari, Flanigan and Hepburn2009), 20 were before-after comparisons (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021; Burke, Prendeville, & Veale, Reference Burke, Prendeville and Veale2017; Dreiling, Cook, Lamarche, & Klinger, Reference Dreiling, Cook, Lamarche and Klinger2022; Driscoll, Schonberg, Stark, Carter, & Hirshfeld-Becker, Reference Driscoll, Schonberg, Stark, Carter and Hirshfeld-Becker2020; Drüsedau et al., Reference Drüsedau, Schoba, Conzelmann, Sokolov, Hautzinger, Renner and Barth2022; Ehrenreich-May et al., Reference Ehrenreich-May, Storch, Queen, Hernandez Rodriguez, Ghilain, Alessandri and Wood2014; Ekman, Hiltunen, Ekman, & Hiltunen, Reference Ekman, Hiltunen, Ekman and Hiltunen2015; Helverschou et al., Reference Helverschou, Bakken, Berge, Bjørgen, Botheim, Hellerud and Howlin2021; Higgins, Slattery, Perry, & O'Shea, Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019; Keefer et al., Reference Keefer, Kreiser, Singh, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Johnson and Vasa2017; Kilburn et al., Reference Kilburn, Juul Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Bech Arendt and Thomsen2019; Maskey et al., Reference Maskey, McConachie, Rodgers, Grahame, Maxwell, Tavernor and Parr2019a; Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood, & Bjaastad, Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021; Ollendick, Muskett, Radtke, & Smith, Reference Ollendick, Muskett, Radtke and Smith2021; Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Beattie, Sullivan, Moody, Stern and Smith2015; Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Leuthe, Moody, & Hepburn, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Leuthe, Moody and Hepburn2012b; Sofronoff, Silva, & Beaumont, Reference Sofronoff, Silva and Beaumont2017; Solish et al., Reference Solish, Klemencic, Ritzema, Nolan, Pilkington, Anagnostou and Brian2020; Swain, Murphy, Hassenfeldt, Lorenzi, & Scarpa, Reference Swain, Murphy, Hassenfeldt, Lorenzi and Scarpa2019; Wise et al., Reference Wise, Cepeda, Ordaz, McBride, Cavitt, Howie and Storch2019), of which two were also mixed-method studies (Burke et al., Reference Burke, Prendeville and Veale2017; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019), two papers compared different samples before and after implementation of a new care pathway (Cervantes et al., Reference Cervantes, Kuriakose, Donnelly, Filton, Marr, Okparaeke and Horwitz2019; Kuriakose et al., Reference Kuriakose, Filton, Marr, Okparaeke, Cervantes, Siegel and Havens2018), seven were surveys (Cooper, Loades, & Russell, Reference Cooper, Loades and Russell2018; Fisher, van Diest, Leoni, & Spain, Reference Fisher, van Diest, Leoni and Spain2023; Ford et al., Reference Ford, Kenchington, Norman, Hancock, Smalley, Henley and Logan2019; Hollocks et al., Reference Hollocks, Casson, White, Dobson, Beazley and Humphrey2019; Jones, Gangadharan, Brigham, Smith, & Shankar Background, Reference Jones, Gangadharan, Brigham, Smith and Shankar Background2021; Pickard et al., Reference Pickard, Blakeley-Smith, Boles, Duncan, Keefer, O'Kelley and Reaven2020; Stadnick, Brookman-Frazee, Nguyen Williams, Cerda, & Akshoomoff, Reference Stadnick, Brookman-Frazee, Nguyen Williams, Cerda and Akshoomoff2015), of which two were also mixed-method studies (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, van Diest, Leoni and Spain2023; Pickard et al., Reference Pickard, Blakeley-Smith, Boles, Duncan, Keefer, O'Kelley and Reaven2020), and two were qualitative only (Petty, Bergenheim, Mahoney, & Chamberlain, Reference Petty, Bergenheim, Mahoney and Chamberlain2021; Spain et al., Reference Spain, Rumball, O'Neill, Sin, Prunty and Happé2017). There were multiple papers that were from the same trials (Cervantes et al., Reference Cervantes, Kuriakose, Donnelly, Filton, Marr, Okparaeke and Horwitz2019; Keefer et al., Reference Keefer, Kreiser, Singh, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Johnson and Vasa2017; Kuriakose et al., Reference Kuriakose, Filton, Marr, Okparaeke, Cervantes, Siegel and Havens2018; Pickard et al., Reference Pickard, Blakeley-Smith, Boles, Duncan, Keefer, O'Kelley and Reaven2020; Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Moody, Grofer Klinger, Keefer, Duncan, O'Kelley and Blakeley-Smith2018; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Moody, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Hepburn, Keefer and Reaven2018; White et al., Reference White, Ollendick, Albano, Oswald, Johnson, Southam-Gerow and Scahill2013, Reference White, Schry, Miyazaki, Ollendick and Scahill2015), thus 57 papers reported on 52 studies. All studies were conducted in high-income countries, mainly in the United Kingdom and United States. Study characteristics are reported in Table 1 and online Supplementary Table S6.

Table 1. Study characteristics

Note: Where age characteristics are not listed in the table this means that they were not reported in the paper. ADHD, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; ASC, Autism Spectrum Conditions; ASD-CP, Autism Spectrum Disorder Care; AUP, Pathway Autism Intellectual Disability and Psychiatric Disorder; BIACA, Behavioral Interventions for Anxiety in Children with Autism; CBT, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; CYP, Children and Young People; DAWBA, Development and Well-Being Assessment; ECHO, Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes; EMDR, Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing; FET, Family-based exposure-focused treatment; FYF, Facing Your Fears; IAPT, Improving Access to Psychological Therapies; ID, Intellectual Disability; MASSI, Multimodal Anxiety and Social Skills Intervention; OCD, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; OST, One-Session Treatment; PTSD, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; RCT, Randomized Controlled Trial; SAS, Secret Agent Society; SCQ, Social Communication Questionnaire; STAMP, Stress and Anger Management Programme; TAU, Treatment as Usual; TüTASS, Tübinger Training for Autism Spectrum Disorders.

a Three parents had two children in the study.

Quality appraisal and publication bias

According to appraisal using the MMAT, for RCTs, 13 papers were of high (≥4 criteria met), 5 papers were of moderate (3 criteria met), and 3 papers were of low quality (≤2 criteria met). Appropriate randomization and blind outcome assessors were the main areas of concern for RCTs. For non-randomized studies, 6 were of high, 15 of moderate, and 2 of low quality. These studies often did not meet the criteria for representativeness and confounder adjustment. For quantitative descriptive studies, three were of high, one of moderate, and one of low quality. Nonresponse bias was the main area of concern for these studies. For mixed-method studies, five were of high (of which two combined RCT with qualitative methods), and one of low quality. The two qualitative studies were of high quality. All MMAT ratings are shown in online Supplementary Table S7. Visual inspection of the funnel plots showed outliers (online Supplementary Fig. S1). Egger's test was significant (child/self z = 2.13, p = 0.033; parent z = 4.70, p < 0.001; clinician z = 3.99, p < 0.001), suggesting the presence of publication bias.

Autism-inclusive research assessment

Four out of 57 papers (7%) reported involvement of autistic people in study design or delivery. One of the 10 papers (10%) with a qualitative element reported adjustments to the data collection process (e.g. allowing non-verbal communication). Five out of 55 papers (9%) with a quantitative element reported making some adjustments to the data collection tools (e.g. defining key terms, using straightforward language, adapting Likert scales for greater precision, using visual tools). Thirteen out of 55 papers (24%) with a quantitative element reported using at least one valid or adapted measure for autistic individuals relevant to the review. For 12 of the 50 papers (24%) with a quantitative element that measured outcomes in autistic mental health service users, the intervention/strategy was identified to involve some focus on masking people's autistic traits. However, 36 of the 50 papers (72%) did not include any evidence to suggest such a focus, and this was unclear for 2 of the 50 papers (4%). All extracted data from the AIRA are shown in online Supplementary Table S8.

Sample characteristics

Sample sizes at baseline in the papers ranged from 7 to 132 autistic participants (median 32, n = 43 studies), 62–302 participants (median 77, n = 3 studies) for studies of strategies to improve the detection of autism, 11–105 parents (median 33, n = 18 studies), and 15–103 clinicians (median 42, n = 8 studies). Fifty papers included CYP, all of whom were given an autism diagnosis, except for three papers regarding initiatives to improve the detection of autism. Two papers included participants with co-occurring intellectual disability (ID). Forty-seven papers described co-occurring mental health difficulties at baseline. Forty-three papers included CYP with an age range of 3–18 years, and seven papers reported on combined outcomes of CYP and adults with an age range of 13–66 years. Ten papers included clinicians as participants. Detailed sample characteristics are in online Supplementary Table S6.

Data synthesis

Strategies used to improve mental health care in autism

Identified strategies included service-level strategies (n = 10) and adapted/bespoke mental health interventions (n = 47). From the identified intervention-level and service-level adaptations, those regarding communication and intervention content were most frequently reported, and adjustment to the environment were least included. Most papers focused on CBT-based mental health interventions for anxiety. Additionally, 37 papers described caregiver involvement in therapy, such as being offered separate/combined sessions. Table 1 and online Supplementary Table S6 contain descriptions of the included strategies and caregiver involvement.

Service-level strategies and adapted interventions

Ten papers explored service-level strategies applied to improve mental health care for autistic people across a service. These papers explored initiatives to improve the detection of autism (Ford et al., Reference Ford, Kenchington, Norman, Hancock, Smalley, Henley and Logan2019; Hollocks et al., Reference Hollocks, Casson, White, Dobson, Beazley and Humphrey2019; Stadnick et al., Reference Stadnick, Brookman-Frazee, Nguyen Williams, Cerda and Akshoomoff2015), strategies for improving clinicians' skills and knowledge of autism (Cervantes et al., Reference Cervantes, Kuriakose, Donnelly, Filton, Marr, Okparaeke and Horwitz2019; Dreiling et al., Reference Dreiling, Cook, Lamarche and Klinger2022; Helverschou et al., Reference Helverschou, Bakken, Berge, Bjørgen, Botheim, Hellerud and Howlin2021; Kuriakose et al., Reference Kuriakose, Filton, Marr, Okparaeke, Cervantes, Siegel and Havens2018), and general adaptations to standard practice concerning the way mental health services are organized for autistic people (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Gangadharan, Brigham, Smith and Shankar Background2021; Petty et al., Reference Petty, Bergenheim, Mahoney and Chamberlain2021; Spain et al., Reference Spain, Rumball, O'Neill, Sin, Prunty and Happé2017).

Twenty-eight papers described studies of adapted mental health interventions to meet the needs of autistic people. These included adaptations of group or individual CBT for anxiety (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021; Burke et al., Reference Burke, Prendeville and Veale2017; Chalfant et al., Reference Chalfant, Rapee and Carroll2007; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Donovan and Garnett2017; Driscoll et al., Reference Driscoll, Schonberg, Stark, Carter and Hirshfeld-Becker2020; Ehrenreich-May et al., Reference Ehrenreich-May, Storch, Queen, Hernandez Rodriguez, Ghilain, Alessandri and Wood2014; Ekman et al., Reference Ekman, Hiltunen, Ekman and Hiltunen2015; Fujii et al., Reference Fujii, Renno, McLeod, Lin, Decker, Zielinski and Wood2013; Hepburn et al., Reference Hepburn, Blakeley-Smith, Wolff and Reaven2016; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019; Kilburn et al., Reference Kilburn, Juul Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Bech Arendt and Thomsen2019, Reference Kilburn, Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Arendt and Thomsen2020; Oerbeck et al., Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021; Ollendick et al., Reference Ollendick, Muskett, Radtke and Smith2021; Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Leuthe, Moody and Hepburn2012b; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Jassi, Fullana, Mack, Johnston, Heyman and Mataix-Cols2013; Storch et al., Reference Storch, Arnold, Lewin, Nadeau, Jones, De Nadai and Murphy2013, Reference Storch, Lewin, Collier, Arnold, De Nadai, Dane and Murphy2015, Reference Storch, Schneider, De Nadai, Selles, McBride, Grebe and Lewin2020; Sung et al., Reference Sung, Ooi, Goh, Pathy, Fung, Ang and Lam2011; Wise et al., Reference Wise, Cepeda, Ordaz, McBride, Cavitt, Howie and Storch2019; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Ehrenreich-May, Alessandri, Fujii, Renno, Laugeson and Storch2015), group CBT targeting emotion regulation (Factor et al., Reference Factor, Swain, Antezana, Muskett, Gatto, Radtke and Scarpa2019; Scarpa & Reyes, Reference Scarpa and Reyes2011; Sofronoff et al., Reference Sofronoff, Silva and Beaumont2017; Swain et al., Reference Swain, Murphy, Hassenfeldt, Lorenzi and Scarpa2019), individual CBT for various mental health needs (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Loades and Russell2018), and Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, van Diest, Leoni and Spain2023). Studies with a comparison group most often compared the adapted interventions to non-active controls, and none compared it to a non-adapted version of the same intervention.

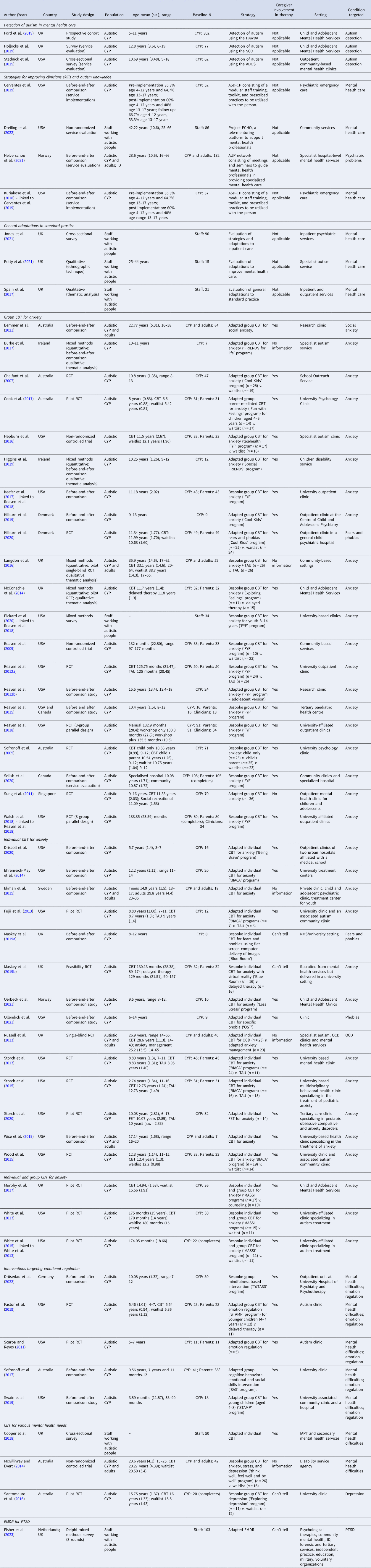

Seven top-level adaptation categories were identified from these papers exploring service- and intervention-level adaptations:

• Increasing knowledge and detection of autism (n = 10, e.g. use of screening tools, clinician training).

• Adjustments to the physical environment (n = 6, e.g. minimizing sensory distractions, providing ear defenders, weighted blankets, fidget toys, and movement breaks).

• Communication accommodations (n = 20, e.g. being directive, adjusting the communication pace, using preferred language, using written information on whiteboard, activity books, agendas, and visual aids like drawings, videos, using social stories, and using a computer to reduce face-to-face contact).

• Accommodating individual differences (n = 16, e.g. evaluating preferences and needs, encouraging special interests and hobbies, and tailoring treatment to these by being flexible with the treatment manual).

• Structural or procedural adaptations (n = 15, e.g. changing the format, duration, or number of sessions, having predictable session routines and structured approach to treatment with details communicated in advance).

• Intervention content adaptations (n = 24, e.g. removing or simplifying psychoeducation and cognitive elements of the intervention, incorporating arts-based activities, using role-play, rewards, taking a progressive approach to treatment with opportunity for repetition and practice)

• Involving the wider support network (n = 18, e.g. involving parents and child's school to support active transfer of skills/therapy goals from clinic to home and school)

More than one adaptation was identified in 31 out of 38 of these papers exploring service- and intervention-level adaptations, meaning papers crossed several categories. Most papers provided a general rationale for these adaptations as addressing barriers to mental health care. There were limited descriptions of specific adaptations and their rationale. Table 2 shows a breakdown of sub-categories which map to these top-level categories. Online Supplementary Table S9 includes details of the individual adaptations used by each paper.

Table 2. All service-level and intervention-level adaptations (simplified version) (N = 38)

Note: ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; SCQ, Social Communication Questionnaire; DAWBA, Development and Well-Being Assessment.

a Several adaptations were often reported by the same article, meaning papers crossed several categories so the number of papers in this column does not add up to the total 38 contributing papers.

Bespoke interventions

Nineteen papers described bespoke mental health interventions originally developed for autistic CYP, often in part by the authors themselves, and tested in their unmodified version. These included a novel combined group and individual intervention for anxiety (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Chowdhury, White, Reynolds, Donald, Gahan and Press2017; White et al., Reference White, Ollendick, Albano, Oswald, Johnson, Southam-Gerow and Scahill2013, Reference White, Schry, Miyazaki, Ollendick and Scahill2015), individual interventions for anxiety in a virtual reality environment (Maskey et al., Reference Maskey, McConachie, Rodgers, Grahame, Maxwell, Tavernor and Parr2019a, Reference Maskey, Rodgers, Grahame, Glod, Honey, Kinnear and Parr2019b), group interventions for anxiety (Keefer et al., Reference Keefer, Kreiser, Singh, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Johnson and Vasa2017; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016; McConachie et al., Reference McConachie, McLaughlin, Grahame, Taylor, Honey, Tavernor and Le Couteur2014; Pickard et al., Reference Pickard, Blakeley-Smith, Boles, Duncan, Keefer, O'Kelley and Reaven2020; Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Nichols, Dasari, Flanigan and Hepburn2009, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Culhane-Shelburne and Hepburn2012a, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Beattie, Sullivan, Moody, Stern and Smith2015, Reference Reaven, Moody, Grofer Klinger, Keefer, Duncan, O'Kelley and Blakeley-Smith2018; Solish et al., Reference Solish, Klemencic, Ritzema, Nolan, Pilkington, Anagnostou and Brian2020; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Moody, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Hepburn, Keefer and Reaven2018), group interventions for anxiety, stress, and depression (McGillivray & Evert, Reference McGillivray and Evert2014) and for depression only (Santomauro et al., Reference Santomauro, Sheffield and Sofronoff2016), all utilizing CBT techniques. Additionally, they included a new group intervention for emotion regulation designed for autistic CYP based on mindfulness principles (Drüsedau et al., Reference Drüsedau, Schoba, Conzelmann, Sokolov, Hautzinger, Renner and Barth2022).

Acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness of strategies used to improve mental health care for autistic CYP

Evaluation of service-level strategies

Ten papers evaluated service-level strategies, grouped into three categories depending on their focus. The main findings of service-level strategies are presented in Table 3, with detailed results of individual studies in online Supplementary Table S12. Online Supplementary Table S10 shows the GRADE assessment for effectiveness outcomes.

1. Detection of autism (n = 3).

Table 3. Main findings of individual/group and adapted/bespoke mental health interventions/strategies and service adaptations

Note: ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; ASC, Autism spectrum condition; AM, anxiety management; CAMHS, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services; CBT, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; CYP, Children and young people; DAWBA, Development and Well-Being Assessment; EMDR, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing; IAPT, Improving Access to Psychological Therapies; ID, Intellectual Disability; OCD, Obsessive-compulsive disorder; PTSD, Post traumatic stress disorder; Ref., References; SCQ, Social Communication Questionnaire; SR, Social recreational program.

a Two papers were from the same service implementation.

b Four papers were from the same randomized controlled trial.

c Two papers were from the same pilot randomized controlled trial.

Overall, moderate certainty evidence suggested that some screening tools may be helpful in detection of autism in mental health services (online Supplementary Table S10). The Development and Well-being Assessment (DAWBA) was found to have moderate agreement with practitioner diagnosis of autism in child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS), suggesting it may be useful to aid the diagnostic process (Ford et al., Reference Ford, Kenchington, Norman, Hancock, Smalley, Henley and Logan2019). Conversely, the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) was found to not be an effective autism screening tool in CAMHS (Hollocks et al., Reference Hollocks, Casson, White, Dobson, Beazley and Humphrey2019). The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) administered in community mental health services was found to identify autistic CYP referred for an autism assessment (Stadnick et al., Reference Stadnick, Brookman-Frazee, Nguyen Williams, Cerda and Akshoomoff2015).

2. Strategies for improving clinicians' skills and autism knowledge (n = 4).

Strategies, involving training and guiding clinicians to provide better care across the lifespan to autistic people with co-occurring mental health needs, included the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes autism model in community services (Dreiling et al., Reference Dreiling, Cook, Lamarche and Klinger2022), the Autism Intellectual Disability and Psychiatric Disorder network in specialist mental health services (Helverschou et al., Reference Helverschou, Bakken, Berge, Bjørgen, Botheim, Hellerud and Howlin2021) and the Autism Spectrum Disorder Care Pathway in psychiatric emergency care (Cervantes et al., Reference Cervantes, Kuriakose, Donnelly, Filton, Marr, Okparaeke and Horwitz2019; Kuriakose et al., Reference Kuriakose, Filton, Marr, Okparaeke, Cervantes, Siegel and Havens2018).

The Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes autism model was found feasible and acceptable to clinicians (Dreiling et al., Reference Dreiling, Cook, Lamarche and Klinger2022). All strategies were associated with significant improvements over time; however, causality cannot be concluded since there were no comparison groups. Overall, low-certainty evidence suggested that some strategies for improving clinicians' skills and knowledge of autism (Cervantes et al., Reference Cervantes, Kuriakose, Donnelly, Filton, Marr, Okparaeke and Horwitz2019; Dreiling et al., Reference Dreiling, Cook, Lamarche and Klinger2022; Helverschou et al., Reference Helverschou, Bakken, Berge, Bjørgen, Botheim, Hellerud and Howlin2021; Kuriakose et al., Reference Kuriakose, Filton, Marr, Okparaeke, Cervantes, Siegel and Havens2018) may be helpful in improving mental health of autistic individuals (online Supplementary Table S10).

3. General adaptations to services (n = 3).

Clinicians reported using a range of adaptations in inpatient units (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Gangadharan, Brigham, Smith and Shankar Background2021), a specialist autism service (Petty et al., Reference Petty, Bergenheim, Mahoney and Chamberlain2021), and inpatient and outpatient services (Spain et al., Reference Spain, Rumball, O'Neill, Sin, Prunty and Happé2017). All papers described clinicians modifying the environment and communication and reported clinicians evaluating and adapting practice based on individual needs. Only one reported on clinicians providing structure to reduce uncertainty (Petty et al., Reference Petty, Bergenheim, Mahoney and Chamberlain2021). None of the papers evaluated the impact of these general adaptations.

Evaluation of interventions

Forty-seven of the included papers, broadly grouped based on similarities in type and focus in four intervention categories, evaluated the effectiveness of interventions in improving autistic individuals' mental health and/or their acceptability/feasibility. The main findings of evaluated interventions are presented in Table 3, with detailed results of individual studies in online Supplementary Table S12. Online Supplementary Tables S10 and S11 show the GRADE assessment for effectiveness outcomes.

1. CBT for anxiety (n = 38).

Thirty-five out of the 38 papers that tested adapted or bespoke individual, group, or combined individual and group CBT for anxiety, reported feasibility outcomes. All 35 papers reported the interventions were feasible largely based on low drop-out rates, high attendance rates, and treatment fidelity (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021; Chalfant et al., Reference Chalfant, Rapee and Carroll2007; Driscoll et al., Reference Driscoll, Schonberg, Stark, Carter and Hirshfeld-Becker2020; Ehrenreich-May et al., Reference Ehrenreich-May, Storch, Queen, Hernandez Rodriguez, Ghilain, Alessandri and Wood2014; Fujii et al., Reference Fujii, Renno, McLeod, Lin, Decker, Zielinski and Wood2013; Hepburn et al., Reference Hepburn, Blakeley-Smith, Wolff and Reaven2016; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019; Keefer et al., Reference Keefer, Kreiser, Singh, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Johnson and Vasa2017; Kilburn et al., Reference Kilburn, Juul Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Bech Arendt and Thomsen2019, Reference Kilburn, Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Arendt and Thomsen2020; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016; Maskey et al., Reference Maskey, McConachie, Rodgers, Grahame, Maxwell, Tavernor and Parr2019a, Reference Maskey, Rodgers, Grahame, Glod, Honey, Kinnear and Parr2019b; McConachie et al., Reference McConachie, McLaughlin, Grahame, Taylor, Honey, Tavernor and Le Couteur2014; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Chowdhury, White, Reynolds, Donald, Gahan and Press2017; Oerbeck et al., Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021; Ollendick et al., Reference Ollendick, Muskett, Radtke and Smith2021; Pickard et al., Reference Pickard, Blakeley-Smith, Boles, Duncan, Keefer, O'Kelley and Reaven2020; Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Nichols, Dasari, Flanigan and Hepburn2009, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Culhane-Shelburne and Hepburn2012a, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Leuthe, Moody and Hepburn2012b, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Beattie, Sullivan, Moody, Stern and Smith2015, Reference Reaven, Moody, Grofer Klinger, Keefer, Duncan, O'Kelley and Blakeley-Smith2018; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Jassi, Fullana, Mack, Johnston, Heyman and Mataix-Cols2013; Sofronoff et al., Reference Sofronoff, Attwood and Hinton2005; Solish et al., Reference Solish, Klemencic, Ritzema, Nolan, Pilkington, Anagnostou and Brian2020; Storch et al., Reference Storch, Arnold, Lewin, Nadeau, Jones, De Nadai and Murphy2013, Reference Storch, Lewin, Collier, Arnold, De Nadai, Dane and Murphy2015, Reference Storch, Schneider, De Nadai, Selles, McBride, Grebe and Lewin2020; Sung et al., Reference Sung, Ooi, Goh, Pathy, Fung, Ang and Lam2011; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Moody, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Hepburn, Keefer and Reaven2018; White et al., Reference White, Ollendick, Albano, Oswald, Johnson, Southam-Gerow and Scahill2013, Reference White, Schry, Miyazaki, Ollendick and Scahill2015; Wise et al., Reference Wise, Cepeda, Ordaz, McBride, Cavitt, Howie and Storch2019; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Ehrenreich-May, Alessandri, Fujii, Renno, Laugeson and Storch2015). Twenty-three out of 38 papers reported acceptability outcomes of adapted/bespoke individual, group, or combined CBT for anxiety for either CYP, parents, or clinicians. All 23 papers reported the interventions were acceptable based on participant-reported positive experiences and intervention satisfaction (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021; Burke et al., Reference Burke, Prendeville and Veale2017; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Donovan and Garnett2017; Ekman et al., Reference Ekman, Hiltunen, Ekman and Hiltunen2015; Hepburn et al., Reference Hepburn, Blakeley-Smith, Wolff and Reaven2016; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019; Kilburn et al., Reference Kilburn, Juul Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Bech Arendt and Thomsen2019, Reference Kilburn, Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Arendt and Thomsen2020; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016; McConachie et al., Reference McConachie, McLaughlin, Grahame, Taylor, Honey, Tavernor and Le Couteur2014; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Chowdhury, White, Reynolds, Donald, Gahan and Press2017; Oerbeck et al., Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021; Ollendick et al., Reference Ollendick, Muskett, Radtke and Smith2021; Pickard et al., Reference Pickard, Blakeley-Smith, Boles, Duncan, Keefer, O'Kelley and Reaven2020; Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Culhane-Shelburne and Hepburn2012a, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Leuthe, Moody and Hepburn2012b, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Beattie, Sullivan, Moody, Stern and Smith2015; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Jassi, Fullana, Mack, Johnston, Heyman and Mataix-Cols2013; Sofronoff et al., Reference Sofronoff, Attwood and Hinton2005; Solish et al., Reference Solish, Klemencic, Ritzema, Nolan, Pilkington, Anagnostou and Brian2020; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Moody, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Hepburn, Keefer and Reaven2018; White et al., Reference White, Ollendick, Albano, Oswald, Johnson, Southam-Gerow and Scahill2013; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Ehrenreich-May, Alessandri, Fujii, Renno, Laugeson and Storch2015).

Facilitators to acceptability reported by participants included perceived positive intervention impact (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019; Kilburn et al., Reference Kilburn, Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Arendt and Thomsen2020; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016; McConachie et al., Reference McConachie, McLaughlin, Grahame, Taylor, Honey, Tavernor and Le Couteur2014; Oerbeck et al., Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021; Ollendick et al., Reference Ollendick, Muskett, Radtke and Smith2021; Sofronoff et al., Reference Sofronoff, Attwood and Hinton2005; Solish et al., Reference Solish, Klemencic, Ritzema, Nolan, Pilkington, Anagnostou and Brian2020) and perceived usefulness of intervention's information/activities/techniques (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016; McConachie et al., Reference McConachie, McLaughlin, Grahame, Taylor, Honey, Tavernor and Le Couteur2014; Oerbeck et al., Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021; Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Culhane-Shelburne and Hepburn2012a, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Leuthe, Moody and Hepburn2012b, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Beattie, Sullivan, Moody, Stern and Smith2015; Solish et al., Reference Solish, Klemencic, Ritzema, Nolan, Pilkington, Anagnostou and Brian2020; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Moody, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Hepburn, Keefer and Reaven2018). Feeling accepted/supported by the group (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016; McConachie et al., Reference McConachie, McLaughlin, Grahame, Taylor, Honey, Tavernor and Le Couteur2014), interaction with others (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016; McConachie et al., Reference McConachie, McLaughlin, Grahame, Taylor, Honey, Tavernor and Le Couteur2014; Sofronoff et al., Reference Sofronoff, Attwood and Hinton2005), and individual preparatory sessions prior to group sessions (Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016) also appeared important. Additionally, receiving preparatory handout for upcoming sessions (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019), perceived parental confidence with the intervention content and thus being able to support their child (Sofronoff et al., Reference Sofronoff, Attwood and Hinton2005; Solish et al., Reference Solish, Klemencic, Ritzema, Nolan, Pilkington, Anagnostou and Brian2020), understanding assignments (Oerbeck et al., Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021), and getting rewards (Oerbeck et al., Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021) were seen as facilitators. Using visualization was viewed as helpful (Ekman et al., Reference Ekman, Hiltunen, Ekman and Hiltunen2015). Clinicians' participation in a short training workshop appeared to facilitate higher acceptability, as opposed to receiving additional ongoing feedback or only a manual (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Moody, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Hepburn, Keefer and Reaven2018).

Participants also reported barriers to acceptability, including perceiving the sessions to be too long/short (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016), difficulties with group dynamics (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016), feeling anxiety limited their learning (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021), feeling the individual sessions involved too much talking (Oerbeck et al., Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021), perceived lack of learning (McConachie et al., Reference McConachie, McLaughlin, Grahame, Taylor, Honey, Tavernor and Le Couteur2014), dissatisfaction with visuals (Oerbeck et al., Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021), children‘s reluctance to talk to parents about content beyond the sessions (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019), difficulties with homework assignments (Oerbeck et al., Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021), and difficulties with making phone calls (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021). Practical issues related to transport, parking, heating in session rooms, and timings also appeared to hinder acceptability (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016). The addition of bi-weekly feedback and consultation next to training workshops might have put clinicians under pressure (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Moody, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Hepburn, Keefer and Reaven2018).

Furthermore, clinicians who continued to implement group version of CBT for anxiety for at least four years following training reported tailoring, lengthening, removing, shortening, and supplementing the intervention's components to enhance and adapt it to the learning needs of CYP and carers (Pickard et al., Reference Pickard, Blakeley-Smith, Boles, Duncan, Keefer, O'Kelley and Reaven2020). Positive clinicians' views of the intervention's effectiveness, ease of use, and fit with existing service were perceived as facilitators for sustained use of this intervention. Reported barriers included the intervention no longer being relevant to the service, services being unable to support delivery, clinicians no longer working clinically, inability to obtain funding for intervention, and difficulties with group format of the intervention due to insufficient staffing and challenges with recruiting a group of CYP of the same age and level of support needs (Pickard et al., Reference Pickard, Blakeley-Smith, Boles, Duncan, Keefer, O'Kelley and Reaven2020).

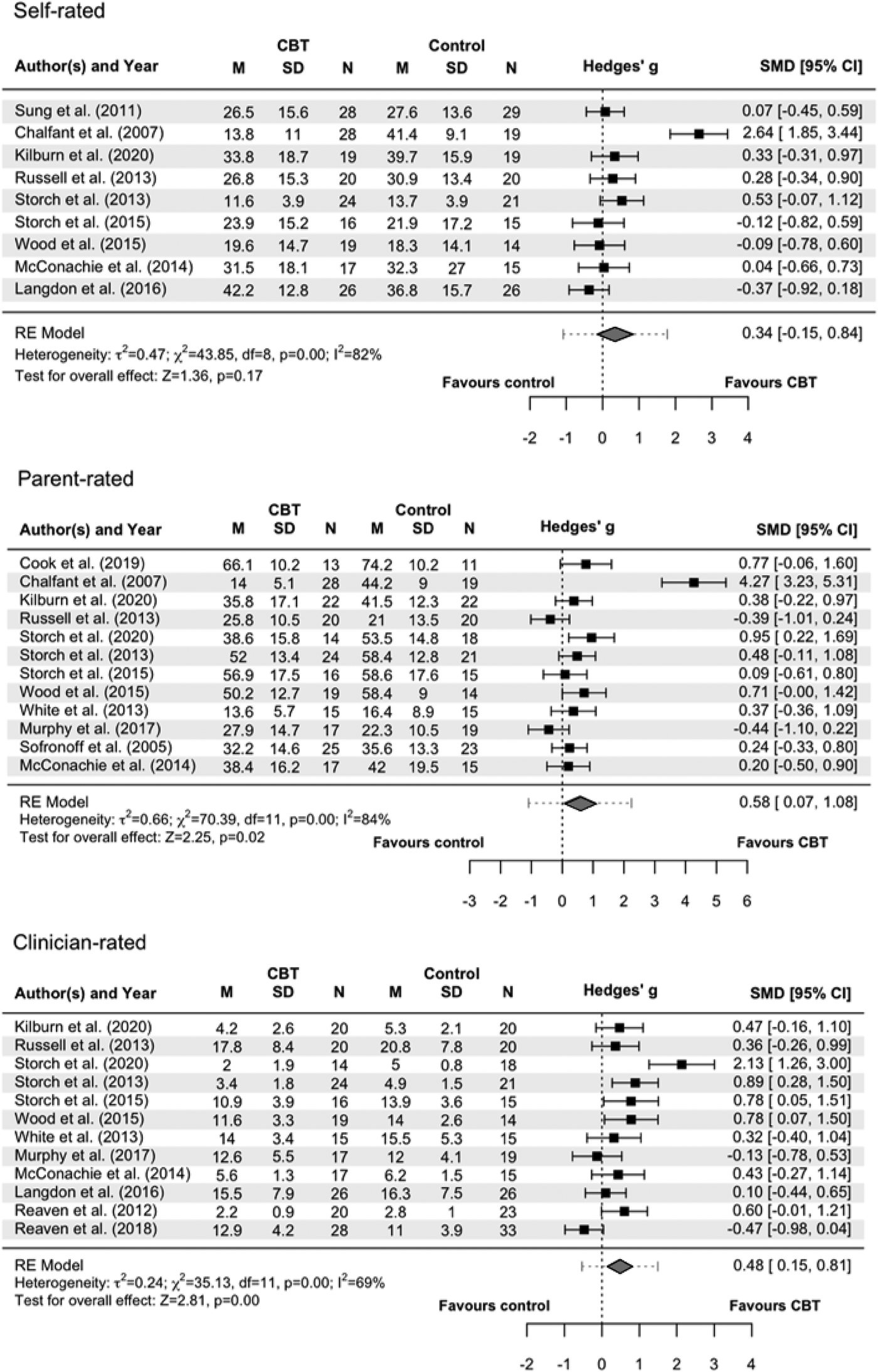

Effectiveness of CBT for anxiety. Thirty-six out of 38 papers evaluating CBT for anxiety reported effectiveness outcomes. Sixteen RCTs/pilot RCTs testing effectiveness of adapted/bespoke individual, group, and combined CBT for anxiety compared to any control group were included in three meta-analyses depending on the rater of the autistic person's anxiety measure.

Child/self-rater meta-analysis: CBT was not significantly different from control, including treatment as usual (TAU), waitlist, adapted anxiety management (AM) and social recreation (SR), in reducing child/self-rated anxiety symptoms at EOT (k = 9, g = 0.34 [95% CI −0.15 to 0.84], p = 0.173) (Fig. 2) (moderate-certainty evidence, online Supplementary Table S11). There was significant heterogeneity among studies, Q(8) = 43.85, p < 0.001, I 2 = 81.75%. On removal of outliers (Chalfant et al., Reference Chalfant, Rapee and Carroll2007; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016), there were no significant differences between groups at EOT (k = 7, g = 0.17 [95% CI −0.07 to 0.40], p = 0.169), but heterogeneity reduced, Q(6) = 3.21, p = 0.782, I 2 = 0%.

Figure 2. Forest plots of meta-analyses comparing cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxiety with any control group in reducing anxiety symptom severity in autistic individuals.

Note: Continuous rather than dichotomous data were used, as this was the most frequent type of data across studies. Intention-to-treat was favored over completer analysis. In cases of trials with more than two arms (Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Moody, Grofer Klinger, Keefer, Duncan, O'Kelley and Blakeley-Smith2018; Sofronoff et al., Reference Sofronoff, Attwood and Hinton2005), we compared the most intensive arm (treatment) to the least intensive (control). The following clinician-rated outcome measures were acceptable and included in the meta-analysis: the Anxiety Diagnostic Interview Schedule (ADIS), the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS), the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A) and the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS). Four studies (Storch et al., Reference Storch, Arnold, Lewin, Nadeau, Jones, De Nadai and Murphy2013, Reference Storch, Lewin, Collier, Arnold, De Nadai, Dane and Murphy2015, Reference Storch, Schneider, De Nadai, Selles, McBride, Grebe and Lewin2020; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Ehrenreich-May, Alessandri, Fujii, Renno, Laugeson and Storch2015) used multiple clinician-rated outcomes. Given this, we favored primary outcome measures first (if reported in article or in protocol), followed by the most frequently used measure across studies (i.e. ADIS) to ensure consistency. Reaven et al. (Reference Reaven, Moody, Grofer Klinger, Keefer, Duncan, O'Kelley and Blakeley-Smith2018) and Murphy et al. (Reference Murphy, Chowdhury, White, Reynolds, Donald, Gahan and Press2017) reported on individual symptoms on the ADIS, rather than the total, hence scores were combined. Acceptable parent/carer-rated outcome measures were the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (SCAS), the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC), the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4 ASD Anxiety Scale (CASI-anx), the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) and the Children's Obsessive Compulsive Inventory (CHOCI). Child/self-rated outcome measures included the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (SCAS), the Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS), the Revised Children's Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS), the Obsessive Compulsive Inventory – Revised (OCI-R) and the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS). One trial (Chalfant et al. Reference Chalfant, Rapee and Carroll2007), used both the RCMAS and the SCAS, but the latter was favored, as it was the most commonly used outcome measure. Storch et al. (Reference Storch, Arnold, Lewin, Nadeau, Jones, De Nadai and Murphy2013) reported only subscales of the RCMAS, so the total mean was calculated.

Parent/carer-rater meta-analysis: There was a significant medium effect of CBT compared to control, including TAU, waitlist, counseling, adapted AM, and bespoke CBT (manual training only), in reducing parent/carer-ratings for anxiety symptoms at EOT (k = 12, g = 0.58 [95% CI 0.07 to 1.08], p = 0.0246) (moderate-certainty evidence, online Supplementary Table S11), and significant heterogeneity, Q(11) = 70.39, p < 0.001, I 2 = 84.37%. After removal of outliers (Chalfant et al., Reference Chalfant, Rapee and Carroll2007; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Chowdhury, White, Reynolds, Donald, Gahan and Press2017; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Jassi, Fullana, Mack, Johnston, Heyman and Mataix-Cols2013), the effect size was still significant (k = 9, g = 0.44 [95% CI 0.21–0.66], p < 0.001). Heterogeneity reduced, Q(8) = 4.99, p = 0.76, I 2 = 0%.

Clinician-rater meta-analysis: CBT had a significant small-to-medium effect on reducing clinician ratings for anxiety symptoms compared to control, including TAU, waitlist, counseling, and adapted AM (k = 12, g = 0.48 [95% CI 0.14–0.81], p = 0.005) (moderate-certainty evidence, online Supplementary Table S11). There was significant heterogeneity, Q(11) = 35.13, p < 0.001, I 2 = 68.69%. On removal of outliers (Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Moody, Grofer Klinger, Keefer, Duncan, O'Kelley and Blakeley-Smith2018; Storch et al., Reference Storch, Schneider, De Nadai, Selles, McBride, Grebe and Lewin2020), the effect size remained significant (k = 10, g = 0.44 [95% CI 0.24–0.65], p < 0.001) and heterogeneity reduced, Q(9) = 8.58, p = 0.477, I 2 = 0%.

Meta-regression analyses: Bespoke CBT showed significantly worse clinician-rated anxiety at EOT compared to adapted CBT (b = −0.72 [95% CI −1.27 to −0.18], p = 0.009), based on six bespoke against six adapted trials. There were no other significant moderators (online Supplementary Table S13).

Seven of the RCTs/pilot RCTs included in the meta-analyses evaluating CBT for anxiety reported non-anxiety outcomes (Kilburn et al., Reference Kilburn, Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Arendt and Thomsen2020; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Jassi, Fullana, Mack, Johnston, Heyman and Mataix-Cols2013; Storch et al., Reference Storch, Arnold, Lewin, Nadeau, Jones, De Nadai and Murphy2013, Reference Storch, Lewin, Collier, Arnold, De Nadai, Dane and Murphy2015, Reference Storch, Schneider, De Nadai, Selles, McBride, Grebe and Lewin2020; White et al., Reference White, Ollendick, Albano, Oswald, Johnson, Southam-Gerow and Scahill2013). Four indicated significant group differences in social functioning at EOT in favor of adapted/bespoke individual or combined individual and group CBT compared to non-active control (Storch et al., Reference Storch, Arnold, Lewin, Nadeau, Jones, De Nadai and Murphy2013, Reference Storch, Lewin, Collier, Arnold, De Nadai, Dane and Murphy2015, Reference Storch, Schneider, De Nadai, Selles, McBride, Grebe and Lewin2020; White et al., Reference White, Ollendick, Albano, Oswald, Johnson, Southam-Gerow and Scahill2013). The remaining three, evaluating bespoke and adapted group CBT compared to non-active controls (Kilburn et al., Reference Kilburn, Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Arendt and Thomsen2020; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016), and adapted individual CBT for OCD compared to adapted AM (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Jassi, Fullana, Mack, Johnston, Heyman and Mataix-Cols2013) at EOT and follow-up, found no such effect. Two trials also showed no effect on depression (Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Jassi, Fullana, Mack, Johnston, Heyman and Mataix-Cols2013).

Studies not included in meta-analyses: Three pilot RCTs/RCTs that reported effectiveness outcomes for CBT for anxiety were not included in the meta-analysis due to having <10 participants per group (Fujii et al., Reference Fujii, Renno, McLeod, Lin, Decker, Zielinski and Wood2013) or no EOT data (only follow-up) (Maskey et al., Reference Maskey, McConachie, Rodgers, Grahame, Maxwell, Tavernor and Parr2019a; White et al., Reference White, Schry, Miyazaki, Ollendick and Scahill2015). They reported significant group differences in anxiety at EOT between adapted individual CBT and non-active control (Fujii et al., Reference Fujii, Renno, McLeod, Lin, Decker, Zielinski and Wood2013), but no significant group differences in anxiety and social functioning at 6-months post-treatment between bespoke individual CBT and non-active control (Maskey et al., Reference Maskey, McConachie, Rodgers, Grahame, Maxwell, Tavernor and Parr2019a). While anxiety worsened over 1-year follow-up after treatment with bespoke individual and group CBT ended, it did not revert to pre-treatment severity 1-year post-treatment (White et al., Reference White, Schry, Miyazaki, Ollendick and Scahill2015).

Two of the 36 papers reporting effectiveness outcomes were non-randomized controlled trials and reported an adapted/bespoke group CBT was effective for parent-reported CYP anxiety at EOT compared to non-active conditions (Hepburn et al., Reference Hepburn, Blakeley-Smith, Wolff and Reaven2016; Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Nichols, Dasari, Flanigan and Hepburn2009), but not for CYP-rated anxiety (Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Nichols, Dasari, Flanigan and Hepburn2009).

Fifteen before-and-after comparisons examined the effectiveness of adapted/bespoke individual/group CBT for anxiety (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021; Burke et al., Reference Burke, Prendeville and Veale2017; Driscoll et al., Reference Driscoll, Schonberg, Stark, Carter and Hirshfeld-Becker2020; Ehrenreich-May et al., Reference Ehrenreich-May, Storch, Queen, Hernandez Rodriguez, Ghilain, Alessandri and Wood2014; Ekman et al., Reference Ekman, Hiltunen, Ekman and Hiltunen2015; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019; Keefer et al., Reference Keefer, Kreiser, Singh, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Johnson and Vasa2017; Kilburn et al., Reference Kilburn, Juul Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Bech Arendt and Thomsen2019; Maskey et al., Reference Maskey, McConachie, Rodgers, Grahame, Maxwell, Tavernor and Parr2019a; Oerbeck et al., Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021; Ollendick et al., Reference Ollendick, Muskett, Radtke and Smith2021; Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Leuthe, Moody and Hepburn2012, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Beattie, Sullivan, Moody, Stern and Smith2015; Solish et al., Reference Solish, Klemencic, Ritzema, Nolan, Pilkington, Anagnostou and Brian2020; Wise et al., Reference Wise, Cepeda, Ordaz, McBride, Cavitt, Howie and Storch2019). Statistically significant improvements in outcomes over time were reported in 14 of these 15 studies (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021; Driscoll et al., Reference Driscoll, Schonberg, Stark, Carter and Hirshfeld-Becker2020; Ehrenreich-May et al., Reference Ehrenreich-May, Storch, Queen, Hernandez Rodriguez, Ghilain, Alessandri and Wood2014; Ekman et al., Reference Ekman, Hiltunen, Ekman and Hiltunen2015; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019; Keefer et al., Reference Keefer, Kreiser, Singh, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Johnson and Vasa2017; Kilburn et al., Reference Kilburn, Juul Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Bech Arendt and Thomsen2019; Maskey et al., Reference Maskey, McConachie, Rodgers, Grahame, Maxwell, Tavernor and Parr2019a; Oerbeck et al., Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021; Ollendick et al., Reference Ollendick, Muskett, Radtke and Smith2021; Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Leuthe, Moody and Hepburn2012, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Beattie, Sullivan, Moody, Stern and Smith2015; Solish et al., Reference Solish, Klemencic, Ritzema, Nolan, Pilkington, Anagnostou and Brian2020; Wise et al., Reference Wise, Cepeda, Ordaz, McBride, Cavitt, Howie and Storch2019). However, causality cannot be inferred since there were no comparison groups.

Considering all 36 papers that reported effectiveness outcomes of individual (Driscoll et al., Reference Driscoll, Schonberg, Stark, Carter and Hirshfeld-Becker2020; Ehrenreich-May et al., Reference Ehrenreich-May, Storch, Queen, Hernandez Rodriguez, Ghilain, Alessandri and Wood2014; Ekman et al., Reference Ekman, Hiltunen, Ekman and Hiltunen2015; Fujii et al., Reference Fujii, Renno, McLeod, Lin, Decker, Zielinski and Wood2013; Maskey et al., Reference Maskey, McConachie, Rodgers, Grahame, Maxwell, Tavernor and Parr2019a, Reference Maskey, Rodgers, Grahame, Glod, Honey, Kinnear and Parr2019b; Oerbeck et al., Reference Oerbeck, Overgaard, Attwood and Bjaastad2021; Ollendick et al., Reference Ollendick, Muskett, Radtke and Smith2021; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Jassi, Fullana, Mack, Johnston, Heyman and Mataix-Cols2013; Storch et al., Reference Storch, Arnold, Lewin, Nadeau, Jones, De Nadai and Murphy2013, Reference Storch, Lewin, Collier, Arnold, De Nadai, Dane and Murphy2015, Reference Storch, Schneider, De Nadai, Selles, McBride, Grebe and Lewin2020; Wise et al., Reference Wise, Cepeda, Ordaz, McBride, Cavitt, Howie and Storch2019; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Ehrenreich-May, Alessandri, Fujii, Renno, Laugeson and Storch2015), group (Bemmer et al., Reference Bemmer, Boulton, Thomas, Larke, Lah, Hickie and Guastella2021; Burke et al., Reference Burke, Prendeville and Veale2017; Chalfant et al., Reference Chalfant, Rapee and Carroll2007; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Donovan and Garnett2017; Hepburn et al., Reference Hepburn, Blakeley-Smith, Wolff and Reaven2016; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Slattery, Perry and O'Shea2019; Keefer et al., Reference Keefer, Kreiser, Singh, Blakeley-Smith, Duncan, Johnson and Vasa2017; Kilburn et al., Reference Kilburn, Juul Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Bech Arendt and Thomsen2019, Reference Kilburn, Sørensen, Thastum, Rapee, Rask, Arendt and Thomsen2020; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Murphy, Shepstone, Wilson, Fowler, Heavens and Mullineaux2016; McConachie et al., Reference McConachie, McLaughlin, Grahame, Taylor, Honey, Tavernor and Le Couteur2014; Reaven et al., Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Nichols, Dasari, Flanigan and Hepburn2009, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Culhane-Shelburne and Hepburn2012a, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Leuthe, Moody and Hepburn2012b, Reference Reaven, Blakeley-Smith, Beattie, Sullivan, Moody, Stern and Smith2015, Reference Reaven, Moody, Grofer Klinger, Keefer, Duncan, O'Kelley and Blakeley-Smith2018; Sofronoff et al., Reference Sofronoff, Attwood and Hinton2005; Solish et al., Reference Solish, Klemencic, Ritzema, Nolan, Pilkington, Anagnostou and Brian2020; Sung et al., Reference Sung, Ooi, Goh, Pathy, Fung, Ang and Lam2011) and combined (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Chowdhury, White, Reynolds, Donald, Gahan and Press2017; White et al., Reference White, Ollendick, Albano, Oswald, Johnson, Southam-Gerow and Scahill2013, Reference White, Schry, Miyazaki, Ollendick and Scahill2015) CBT for anxiety, which were synthesized narratively, moderate-certainty evidence suggested mixed results that these interventions may be helpful in reducing anxiety among autistic individuals (online Supplementary Table S10).

2. Interventions targeting emotion regulation (n = 5).

Three out of five papers evaluating adapted/bespoke group interventions targeting emotion regulation reported feasibility outcomes. Two papers separately reported that an adapted group CBT for autistic children aged 4–7 years with mental health difficulties (Factor et al., Reference Factor, Swain, Antezana, Muskett, Gatto, Radtke and Scarpa2019) and a bespoke group mindfulness-based intervention for autistic children aged 7–12 years with mental health difficulties (Drüsedau et al., Reference Drüsedau, Schoba, Conzelmann, Sokolov, Hautzinger, Renner and Barth2022) were feasible, based on low drop-out rates and high attendance. However, one paper found limited feasibility for a parent-delivered cognitive behavioral emotional and social skills intervention for autistic children as some parents reported difficulties with engaging their child to complete the program, time constraints, and interference with life events (Sofronoff et al., Reference Sofronoff, Silva and Beaumont2017). Two out of five papers reported on treatment satisfaction and showed the interventions were acceptable (Drüsedau et al., Reference Drüsedau, Schoba, Conzelmann, Sokolov, Hautzinger, Renner and Barth2022; Swain et al., Reference Swain, Murphy, Hassenfeldt, Lorenzi and Scarpa2019). Children and parents reported they enjoyed and benefited from the group mindfulness-based intervention, although homework and having sessions on a weekly basis contributed to some dissatisfaction (Drüsedau et al., Reference Drüsedau, Schoba, Conzelmann, Sokolov, Hautzinger, Renner and Barth2022). Parents noted that psychoeducation, support, and skills training components were helpful and reported high satisfaction with the adapted group CBT-based intervention for autistic children aged 4–8 years, with some parents reporting wanting more time for discussion and others noting some difficulties with generalization of skills provided by the intervention (Swain et al., Reference Swain, Murphy, Hassenfeldt, Lorenzi and Scarpa2019).

Two out of five papers were RCTs. One did not statistically compare the two groups (Factor et al., Reference Factor, Swain, Antezana, Muskett, Gatto, Radtke and Scarpa2019). The other was a pilot RCT, which preliminarily showed an adapted group CBT for children aged 5–7 years was not effective for emotion regulation but was effective for frequency of anger/anxiety episodes, use of emotion regulation strategies, and parent-reported perceived confidence in their child's ability to manage their own anxiety and anger, all post-treatment compared to waitlist control (Scarpa & Reyes, Reference Scarpa and Reyes2011). The remaining three papers were before-and-after comparisons reporting on intervention effects over time (Drüsedau et al., Reference Drüsedau, Schoba, Conzelmann, Sokolov, Hautzinger, Renner and Barth2022; Sofronoff et al., Reference Sofronoff, Silva and Beaumont2017; Swain et al., Reference Swain, Murphy, Hassenfeldt, Lorenzi and Scarpa2019), however, causality cannot be inferred since there were no comparison groups. Overall, low certainty evidence suggested mixed results regarding the effectiveness of some group interventions targeting emotion regulation to improve mental health of autistic CYP ((Drüsedau et al., Reference Drüsedau, Schoba, Conzelmann, Sokolov, Hautzinger, Renner and Barth2022; Factor et al., Reference Factor, Swain, Antezana, Muskett, Gatto, Radtke and Scarpa2019; Scarpa & Reyes, Reference Scarpa and Reyes2011; Sofronoff et al., Reference Sofronoff, Silva and Beaumont2017; Swain et al., Reference Swain, Murphy, Hassenfeldt, Lorenzi and Scarpa2019); Online Supplementary Table S10).

3. CBT for various mental health needs (n = 3)

One paper examined therapists' experiences of using CBT with autistic people and adaptations incorporated into their routine practice (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Loades and Russell2018). A range of adaptations were endorsed, including accommodating individual differences, changing the structure and content of interventions, and establishing communication preferences. Adaptations reported as being used less consistently included shorter/longer sessions, avoidance of metaphors, and use of cognitive strategies. Most participants reported using CBT and favored this approach over others.