Introduction

Corruption today is a crucial concern for Latin America, and many nations have relatively clear definitions of the crime on the books. Yet corruption in the Spanish empire from roughly 1492 to the early 1800s differed. Theologians, legal experts, and laypeople debated the meaning and boundaries of corruption, and the limits of gift giving and bribery were malleable to some degree. Jurists weighed various judicial sources to assess the crime, as the crown was not the only authority producing rules. Instead, Spaniards appreciated the Roman and the canon (Church) law and their manifold interpreters. Their doctrines had to conform to natural law, which was essentially reason, as past generations understood that notion. In addition, the maxims revealed in the Bible coexisted with the royal mandates, such as the Law of the Indies (law for Spanish America), and the local customs, including the indigenous traditions.

Latin American historians have always paid attention to canon and royal law and local customs, though English-speaking Latin Americanists have preferred focusing on social practices. Scholars, largely outside the United States, have also analyzed the actions of social networks composed of patrons and clients. Their contributions have greatly advanced our knowledge about justice in New Spain (colonial Mexico), although they have often overlooked the working of the law. Meanwhile, legal scholars have skillfully traced changing judicial concepts but often neglected their application in trials “on the ground.”Footnote 1 This chapter focuses on the shifting meaning of the law between 1650 and 1755 by drawing on the scholarship, published discourse, and archival sources. Legal concepts from a variety of sources mattered deeply for novohispanos (those from New Spain), especially when assessing corruption. Judges of various standing ruled on conflicts, while the crown sent visitas (judicial investigations) to enforce rules, uncover malfeasance, and gather information about the realms. At the same time, social networks glued together the colonial society, supported or defied the crown, and shaped the visitas. In addition, social bodies with their own jurisdictions, such the Jesuit order, determined the lives of novohispanos. These social bodies often had great autonomy, lived by their own norms, and mediated royal rule. This chapter sets the stage for this book by sketching the importance of the six key sources of the law (there were more) which defined the view of corruption. Moreover, the chapter outlines the influence of social networks and social bodies on judges and visitas, while casting an eye on the changing nature of the empire as a whole.

1.1 The Six Pillars of Justice

Justice in the Spanish empire drew on a multitude of norms among them the Roman law. The classical lawyers, for example, had defined justice as “the continuous and unimpaired will of giving to each their due.” Spaniards generally agreed with this dictum, yet the multitude of early modern norms made it difficult to ascertain what each person was actually due. Judges therefore ideally balanced the various legal and theological sources against one another, heard all involved parties in the conflicts, and applied the accepted ways of litigation. They also decided on a case-by-case basis and therefore every sentence differed from another. By adhering to this process, the judges resolved conflicts in a just manner. In the late seventeenth century, however, the judicial plurality began to dissolve. The Roman and canon laws lost influence, while the importance of the royal law and its interpreters rose. Later, some jurists even demanded to cast out the entire plurality and write an entirely new and systematic code.Footnote 2

Yet before these changes began, Roman law permeated legal thinking. Emperor Justinian (527–565) had cast an important foundation when he ordered his jurists to compile the vast judicial knowledge of the time. Between 533 and 534, the jurists produced four books, including the Institutes that were designed as a teaching tool and contained the phrase “giving to each their due.” The jurists also devised the Digest, which assembled the interpretations of the important lawyers, while the Code comprised the emperors’ orders. Finally, the Novels added Justinian’s most recent mandates. Publishing the four books was an enormous achievement. Yet while Rome straddled Asia and Africa at that time, its rule in Europe had diminished. Many schools that taught the requisite skills to understand the four books had shut their doors. As a result, only some isolated pockets on the Italian peninsula adopted Justinian’s collection.Footnote 3

A revival blossomed in eleventh-century Bologna (Italy), deeply influencing Iberia and most of Europe. The scholars in that city were among the first to gather Justinian’s scattered texts and revere them as sacred. They richly interspersed notes or glosses at the margins of the laws to explain the concepts, and they became known as the glossators for their style. In the later medieval period, the school of the commentators penned separate and longer treatises and superseded the glossators. Both schools set themselves apart from lay judges by studying in Latin at colleges and universities. They used the dialectical method of scholasticism to flesh out the principles and harmonize the apparent contradictions in Justinian’s collection. This revival rubbed off on Spain’s juridical culture. For example, the words for consultation of a Council, a decree, an edict to the public, or a legal opinion descended directly from the Roman model. Spanish literati also extolled Roman law and its interpreters as bulwarks of virtue and liberty. For the poet Francisco de Quevedo (1580–1645), the Roman norms “did not allow passion, anger, or bribery, and with sure method and due and universal process” they punished sins.Footnote 4

Canon (Church) law joined Iberian judicial culture as the second pillar in the medieval period. Following the example set by the glossators, clergymen collected important Church decisions in the first half of the twelfth century. The popes later recognized the collection as the official Church Decree, and other priests gathered additional council resolutions, papal decisions (decretals), and the writings of the Church fathers. This body of norms evolved into its own discipline over time and separated from theology. Yet canon law also remained deeply intertwined with Roman law as jurists of the two fields continually conversed with one another. These two combined sources and their interpretations eventually became known as the ius commune (or the general law).Footnote 5

Some interpreters of the ius commune rose to great renown, and their doctrines became law themselves. The Italian commentator Bartolus de Sassoferrato (1313/14–1357), for example, left a mark on the universities of the early Spanish empire, although his influence declined much in the seventeenth century. Many attorneys originally claimed that they “were not jurists unless they were Bartolists.”Footnote 6 The sixteenth-century jurist Jerónimo Castillo de Bobadilla, for instance, cited Bartolus amply. Castillo de Bobadilla argued that the good corregidor (a district judge akin to an alcalde mayor), who usually had no academic training, should rule according to the law and the common opinion of the recognized jurists. Castillo de Bobadilla continued that it would be better in any case for the judge to consult his legal adviser, who fully understood the interplay of scholarly arguments, including Bartolus’s view, with the Roman, canon, and royal laws.Footnote 7

Legal practitioners often also called on the Bible, the Church fathers, or other theological principles, and the divine law became the third pillar of legality. “Christ is justice himself,” one early modern jurist held, and the faith commanded the king to safeguard that sacred underpinning of society. Many therefore cited the divine law in their arguments.Footnote 8 When the visitador general (investigative judge) Francisco Garzarón inspected the audiencia (high court) of Mexico City between 1716 and 1727, for instance, he insisted that a corrupt judge report to jail. Yet the delinquent ran off and pleaded with the king for mercy. He declared that his escape was “a natural defense, because Christ himself as a child escaped from Herod’s slaughter and taught his disciples to flee elsewhere when persecuted by a city … and Saint Paul practiced the same by descending from the Roman walls in a basket … while Saint Peter fled from most heinous chains and prison when an angel saved him.” The judge used that theological narrative for his defense, which the crown prosecutor in Madrid accepted without any astonishment. The prosecutor even suggested absolving the defendant from the charge of disobeying Garzarón’s orders.Footnote 9

While theological arguments ran strong, sixteenth-century secular ideas increasingly challenged the late medieval consensus. Humanists favored logic over ancient authority to explain natural phenomena. Especially French jurists began attacking the prevailing interpretations. They perceived Justinian’s collection as a historical source that had developed over centuries with often opposing aims. Their insight vitiated the medieval enterprise of harmonizing the inherent contradictions of the collection. As a result, the sacred and immutable status of the Roman law took a blow. The humanist jurists derided their Bartolist colleagues as “ignorant donkeys” for ruminating profusely on each separate law. Instead, these modern jurists favored elegant treatises on a subject matter for which they assembled all applicable rules to assist the practicing attorneys.Footnote 10

André Tiraqueau (1488–1558), for example, marked a milestone by proposing to avert crime rather than punishing ruthlessly. He opposed defining a cruel penalty for each offense as had been the norm, and instead “sought to prevent others from sinning.”Footnote 11 Tiraqueau suggested taking into account the seriousness of the committed crime and the personal qualities of the offenders including their age, sex, and mental condition. To this end, the jurist expanded the judge’s arbitrio (judgment) to tailor the sentence to the circumstances of the crime. Tiraqueau and the humanists made an impression on the Spanish empire. The arbitrio unfolded and buttressed court rulings that even most commoners in Mexico City found appropriate well into the eighteenth century.Footnote 12

Jurists reconciled these developing interpretations with natural law, the fourth pillar of justice. Natural law virtually meant reason as the cosmic order revealed it. The idea that the law had to be reasonable went back to the Romans, who compared human life to nature when ascertaining the principles that shaped the law. Cicero, for instance, espoused “the true reason that correlates with nature.”Footnote 13 Justinian’s collection also recognized that humans and animals showed similarities in matrimony and child rearing. Later, reason breathed new life into Spanish scholasticism at Salamanca.Footnote 14 During Garzarón’s investigation, officials used natural law to ward off unwanted royal limitations on their fees, for example. An audiencia usher, who guarded the doors and carried documents among the offices, held that “natural law … allowed demanding more than what is assigned, because there is much work to do and no salary.” It was therefore reasonable that he charged Indians higher fees for his services so that he could make a living.Footnote 15 Novohispano judges stated a similar point. In their view, reason justified accepting gifts because of the considerable costs of living in Mexico City.Footnote 16

When such practices became ingrained, they joined the customs, the fifth pillar of justice. In the early modern societies, many customs had the force of law and shaped judicial sentencing. Customs arranged much of the indigenous land ownership, for instance. Indian alcaldes (magistrates) usually observed the communal traditions in this regard, alleging that they had done so since immemorial times. The Law of the Indies explicitly recognized those “norms and customs that the Indians have had since old times for their good government and order, and those customs and usages, which they have obeyed and practiced since becoming Christians.”Footnote 17 In addition, for example, no explicit written code governed the conduct of people who moved to other places in the Spanish empire. The king occasionally intervened to award new citizenship to migrants, but in most cases, newcomers to towns performed along unwritten guidelines. When they showed their commitment to the faith, the community tacitly included them in the citizenry. At the same time, the towns usually denied the same rights to Romany (gypsies), Jews, or blacks and frowned upon them as rule breakers.Footnote 18

Finally, the royal law of the land issued by kings and queens formed the sixth pillar of justice. In the 1260s, the king of Castile set an important milestone in this regard by publishing the Siete Partidas (Seven Parts). This collection comprised ample royal communications and Spanish translations of the Roman law. King Philip II (1556–1598) later ordered his jurists to draft a new compilation, incorporating the Siete Partidas and other Castilian collections. These jurists also selected suitable reales cédulas (royal provisions) from an immensity of the king’s communications. When they completed the process, the king published the Law of Castile in 1567.Footnote 19 In a similar move, the crown assembled the Law of the Indies. By the middle of the sixteenth century, the crown had issued about 10,000 provisions for the Americas, filling 200 books. Legal experts began compiling them, but reales cédulas kept pouring out until 500 books could not hold them anymore. Finally, the American-born jurist Antonio de León Pinelo and his colleague, Juan de Solórzano y Pereyra, concluded the work in 1636. They arranged the rules according to subject matter, creating an authoritative guideline for the Indies.Footnote 20

The Law of the Indies gave the Americas their own legal collection akin to the special fueros (rules) of the peninsular kingdoms. The collection described the Indies as “great kingdoms and seignories” in the empire instead of lesser provinces.Footnote 21 The aim of this phrase was to appease the American elites and increase their loyalty to Madrid. This mattered, because King Charles II (reigned 1665–1700) of Spain remained childless. The other European powers at that time discussed partitioning the Spanish empire among themselves. As a response, Madrid sought to tie the Americans firmly to the crown by publishing the new collection in 1680 and enshrining the status of the overseas kingdoms.Footnote 22

The Law of the Indies generally superseded older collections and reales cédulas in the Americas. Its rules and its interpreters increasingly served as guidepost for judges and the Council of the Indies (the appeals court for American affairs), and reform-minded jurists tended to draw on other sources less frequently.Footnote 23 For instance, in 1719, Garzarón suspended a judge for buying a house in Mexico City, among other charges. The crown opposed such acquisitions, because they indicated that the ministers joined society and became corruptible. The judge showed in his defense a real cédula from 1663 allowing such a purchase. Yet the prosecutor of the Council of the Indies rebutted this argument in 1724 by maintaining that the Law of the Indies nullified the older reales cédulas. The prosecutor convinced the king and the Council, who convicted the judge.Footnote 24

At the same time, locals on occasion suspended those newly arriving orders that they found undesirable. Novohispano judges and officials returned the provisions to Spain when they collided with local experience or breached other rules. They requested additional instructions addressing these concerns. The functionaries also maintained that the “unjust law does not oblige the conscience” to act and preferred to “obey but not to execute” the royal mandate. In this way, colonials vowed loyalty to the crown while stalling the particular measure. Such maneuvering pervaded the Atlantic world. In the Austrian-Hungarian empire, for example, the ministers on occasion respectfully tabled the orders and sent them back to Vienna. They and their Spanish colleagues ultimately built on Roman traditions of forging a consensus to implement change.Footnote 25

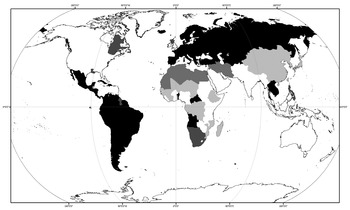

These evolving ideas circulated in the Atlantic world. The Spanish empire acknowledged the ius commune, and so did the Holy Roman Empire (Germany), France, and Italy. Even the English common law, which struck a different course than continental European law, conversed with canon and Roman law. Jurists advanced new legal solutions in response to the expanding economies and vibrant intellectual life. They avidly read their colleagues’ works beyond any political or linguistic boundaries. For example, legal experts in the Holy Roman Empire cited the Spanish attorney Diego Covarrubias. Novohispano teachers and students alike read Italian, French, Dutch, or German scholars writing in Latin or as synthesized by others. The eighteenth-century rector of the University of Guatemala prepared his lectures by studying the Bavarian canonist Johann Georg Reiffenstuel. Another striking example are the eighteenth-century Recitations, a Latin comment on the Roman laws written by a lawyer from Saxony (Holy Roman Empire). The text was later translated into Spanish and freely adapted to the Americas. The Atlantic legal culture fused the ius commune with its own traditions.Footnote 26

Map 2 The Global Ius Commune. Today’s legal systems that build directly on the ius commune are marked in black, while the regions colored in gray have mixed legal systems with heavy infusions of ius commune concepts.

In New Spain, many scholars were familiar with the legal culture. Theologians wrote manuals to prepare priests for administering the sacraments, especially for the confession. The clergymen drew on the ius commune and widely disseminated its concepts in relatable ways. In addition, professors at the University of Mexico City owned parts of Justinian’s collection and its interpreters. The first professor of rhetoric in the sixteenth century, for instance, owned eleven books written by Bartolus, while early eighteenth-century booksellers sold humanists such as André Tiraqueau. The university professors in Mexico City cited these legal scholars when discussing the Roman and royal law.Footnote 27

When law students graduated from the university, they often joined the colegio de abogados (college of attorneys) to practice, or they became salaried relatores. The relatores worked for the audiencia and assessed whether litigation had the standing to go to trial. They also summarized the documents submitted to court and greatly simplified the work for the judges. Most other lawyers spent four years in residence with an experienced attorney. When they completed that phase, they took an exam at the audiencia, at least in theory. The audiencia then admitted them to represent clients. Many, if not all, of these lawyers became lesser nobles or confirmed their status upon graduating from the university.Footnote 28 Most of them also joined the college of attorneys. This must have been some kind of a social body, perhaps a confraternity associated with a church. In 1724, the Council of the Indies chided the “college of attorneys for having charged excessive fees and gifts.” Subsequently, the college became more formalized in 1760 as an independent social body.Footnote 29

In addition, the legal agents without university training played much larger roles than historians have thought before. Procuradores (procurators) especially represented Natives and other commoners in matters of process. They submitted briefs, moved paperwork through the legal machinery, and contracted attorneys when necessary. Procurators often acquired substantial knowledge and successfully acted akin to lawyers. They even crafted their own judicial arguments for the courts, although the crown forbade them to do so. This is why I refer to both academically trained jurists and procurators as legal practitioners or experts in this book. In addition, notaries investigated crimes, questioned suspects, and copied or summarized papers. That may seem like a straightforward task, but the slant of their summaries and the aim of their interrogations deeply influenced the judicial verdicts.Footnote 30

When legal experts went to work, they continuously weighed the royal law and local custom against Roman, canon, and biblical principles, and no clear boundary separated the law from social practices. Historians describe that complexity as “judicial pluralism,” which differed markedly from modern ideas of a (relatively) unequivocal, systematic, and hierarchical legality.Footnote 31 The indigenous community of Meztitlan (Hgo.), for instance, complained in 1724 that a local resident had bought the appointment as alcalde mayor. The viceroy and the audiencia heard the case and agreed that a real cédula from 1691 permitted purchasing the appointment.Footnote 32 The viceroy’s adviser then cited the contrary opinion of Roman emperor Severus Alexander (222–235) and noted that several theologians condemned selling offices as tantamount to selling justice. He balanced these points against the Law of Castile and the “Law of the Indies which did not hold that offices with jurisdiction were unsellable.” The adviser finally emphasized that Charles de Borromeo, a sixteenth-century saint, had also sold his principality with his judicial duties, which was “licit and honest because his pious aim was giving alms to the poor.” The adviser pondered the mandates of these different normative sources and concurred with the viceroy and the audiencia that the alcalde mayor could serve his post.Footnote 33

The precise relationship among the six pillars of justice was often contested, although Spaniards generally preferred the specific over the general rule. Typically, the Law of the Indies reigned supreme in the Americas, followed by the Law of Castile and the Siete Partidas. Meanwhile, the Roman law and its interpreters did not have direct validity in the Spanish empire, but their concepts deeply infused jurisprudence.Footnote 34 Yet jurists and procurators did not always strictly observe that hierarchy. Juan de Hevia Bolaños, a brilliant legal agent working in Lima, exemplified this uncertainty in his discussion of Church protections for offenders. “Although imperial civil law,” he explained, referring to the Roman collection, and the “royal law of the Siete Partidas order that adulterers, rapists of virgins, murderers, and debtors … cannot seek asylum in the church … Church law corrects this case, which is applicable since this is an ecclesiastical issue … according to the common opinion of the doctors … and the customs which have affirmed Church law.” For Hevia Bolaños, the important jurists and customs concurred that canon law displaced both royal and Roman rules in this matter.Footnote 35

Moreover, at least some novohispano ministers held that customs and process were more specific than royal law, especially when justifying their own actions. A civil judge claimed, for example, that a “particular custom is a law that nullifies other written ones,” including the royal and Roman law.Footnote 36 One attorney added that “just and reasonable custom predominates and is preferable to the official fee in those locales” where the schedule did not adequately provide for the attorneys.Footnote 37 Another lawyer maintained in 1722 that the “municipal law is no other thing than the fee schedule,” meaning that the customs of a town allowed him to ignore the official fee schedule imposed by a crown minister.Footnote 38 For many, the word estilo also referred to judicial process at a court of justice and resembled custom. An attorney argued that his client “never demanded or took more than estilo allows … and if others gave him one peso then because this was estilo, and … ruling against estilo is legally void … it should remain in force because of its tradition and age.”Footnote 39

Many legal experts agreed with these officials that customs remained valid as long as the courts applied or the king tacitly approved them. Lawyers often cited a judicial precedent to demonstrate that a particular custom was still in use. When such direct evidence was lacking, implicit tolerance often sufficed. In this line of thinking, a novohispano attorney insisted in 1724, that “the custom that the agents receive some amounts … is in force and vigor” and existed within plain “view, knowledge, and sufferance of that Senate and therefore the Prince … and with their tacit consent.” The lawyer compared here the audiencia of Mexico City to the Roman legislature and showed that no “prohibitive law, statute, constitution … and law of the Indies” indicated that the king had withdrawn his tolerance of this particular custom.Footnote 40

The defense of custom was no mere self-serving and cynical strategy because even the councilors of the Indies accepted the importance of customs to a point. For example, the Council meted out fairly lenient punishments to those officials charged with overcharging their clients. The officials stated in their defense that these excessive fees were customary to remedy their low income. The Council ordered these lower functionaries to pay their share of visita (special investigation) costs and perhaps minor penalties, and the officials then returned to their posts. Nonetheless, the doctrine on the tacit consent also slowly dissolved in the eighteenth century. This explains, in part, why Francisco Garzarón had tacked a harder line in suspending these officials.Footnote 41

Next to the doctrine on tacit consent, the full legal plurality and perhaps many aspects of diversity declined when strands of the Enlightenment dawned on the empire in the late seventeenth century. As a consequence, the royal law gained strength over other normative sources in the courts and the colleges. Many professors shifted their focus to the royal law and their interpreters, and even academic chairs were renamed. They dropped references to Justinian’s Institutes, for example, replacing them with sections of the royal law.Footnote 42 In part for these reasons, judges who based their defense on the Law of the Indies during Garzarón’s visita usually fared better. A criminal judge, for instance, acknowledged that he and his colleagues had to sign off jointly on prisoner release. Nevertheless, the criminal judge admitted that he had single-handedly set free a handful of inmates who owed small amounts of money, because the Law of the Indies forbade litigation under twenty pesos. Therefore he did not have to seek his colleagues’ consent in these cases. It is likely that the judge’s defense held, because Garzarón charged three other criminal judges with the same offense and acquitted them.Footnote 43

Royal agents often legitimized this shift toward the royal law as a return to the good old order, because innovation was harder to justify. An exchange from 1721 illustrates this matter. The king deplored the general disregard for the royal law, and the civil judge José Joaquín Uribe seconded this point. He emphasized that the “due observance of the law” would restore the audiencia “to its ancient luster and dignity.”Footnote 44 Rather than returning to the splendor of the past, however, the crown demanded from the ministers “the exact compliance with the law and ordinances” as a way of asserting royal control. The crown increasingly demanded obedience from its ministers.Footnote 45

As the royal law grew in stature, jurists called for a new systematic code encapsulating all doctrines. A growing number of legal practitioners discarded the vast multitude of rules from the past. Instead, they distilled general principles of justice and derived from them subordinate clauses. Jurists also envisioned a precise language that lay people could understand without falling prey to pettifoggers. Consequently, they demanded curbing the arbitrio of judges to obtain more predictable rulings determined by the new code. The judge was to be no other than “the mouth that pronounced the words of the law.”Footnote 46 Despite these innovations, many still recognized that the judge had an important role to play in unforeseen conflicts. Legal experts also appreciated the wisdom of existing doctrines, which they incorporated into the developing codes. As a result, ministers in Prussia (Germany) began drafting a Civil Code in 1746. The French Civil Code followed soon, pioneering a lasting foundation for the emerging bourgeois society, which also influenced many other regions in a lasting way. A revised form of that code remains in force today in the state of Louisiana, for instance.Footnote 47

The reformers in the early eighteenth-century Spanish empire jumped on the bandwagon. They began to distance themselves from the ancient compilations and lambasted wily and obfuscating jurists. The jurist Melchor de Macanaz stated in 1722 that “the multitude of our laws confound more than they guide equity and justice.” For him, the Roman law “twists the process of justice, stupefying the understanding of the judges, who perhaps choose among the infinity of legal opinions the one that is least reconcilable with reason.” Macanaz instead suggested one “code as pattern and rule for judges and lawyers.”Footnote 48 About twenty-five years later, another jurist labeled even the Law of Castile as a bewildering source of litigation and derided the “compilation of laws and vague conclusions.”Footnote 49

Not everyone agreed. In New Spain, many stood by the Law of the Indies that guaranteed the autonomies of the kingdom. In addition, a late seventeenth-century Spanish judge maintained that “changing old process of government upsets the vassals, and one should always avoid innovations.”Footnote 50 In 1700, the aristocrat Pedro de Portocarrero y Guzmán thundered against the “multiplicity of laws which is evident proof of the corruption of customs.” Portocarrero y Guzmán directed his ire not against the ius commune, but against the pragmatics, the broad legal innovations of kings that undermined justice of the past. From his perspective, he had a point. As the privileges of the old order crumbled, new types of judges ascended to the courts. They downplayed the old judicial plurality and concentrated on royal compilations, their interpreters, and recent mandates from above. For Portocarrero y Guzmán, these innovations violated justice as he knew it. For others, they heralded a new epoch of justice.Footnote 51

1.2 Judges, Visitas, and Social Networks

Commoners and nobles had relatively easy access to legal representation and the courts in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Civil and criminal trials were on the rise in most Atlantic empires, and this “popular legalism” marked New Spain too.Footnote 52 In addition, social networks pervaded the empire and local intermediaries played a crucial role in exchanging resources and making decisions. Yet when networks skewed the judicial and political deliberations excessively or when a revolt threatened the established order, the king appointed visitadores. These investigative judges sidestepped the cumbersome course of justice, suggested remedies, and often punished malefactors more quickly and harshly.

Judges assured that accusers, defendants, and witnesses had their say in lawsuits. For this reason, Natives, slaves, widows, and the elderly frequently turned to the courts for redress. The judges sometimes bemoaned litigious Indians who caused heavy workloads but often ruled in favor of the Natives and against the alcaldes mayores or other social superiors. The king or the queen upheld this system. They heard the appeals coming from the Americas, acted as the supreme arbiters, and showed good care for their vassals by listening to their concerns. In fact, the words for audiencia and oidor (civil judge) were both derived from hearing. Consequently, most novohispanos stated their viewpoint in the courts of justice when called upon, and most believed that the justice system of the Spanish empire sentenced appropriately.Footnote 53

Even some “miserable widowed Indias [Native women]” successfully appealed to the courts for help against their alcalde mayor. In the early eighteenth century, the Indias sued Pedro Hernández, the Native governor of Santa María Nativitas Atlacomulco (state of Mexico). They alleged that Hernández had charged them three pesos tribute every year to release them from the labor draft for the silver mines of Tlalpujahua (Michoacan), although only men went to work there. When they took the case to the special Indian court, Hernández “attempted to cheat the widows with soft words offering compensation.” He also asked a public notary to certify that the widows had paid three pesos in tribute every ten years instead of every year.Footnote 54 The Indias, however, complained to the audiencia in 1712 that the governor set a bad example. He had allegedly lived with a woman, “pretending that he would marry her … and then the governor deceived and left her and married another.” In addition, the “pregnant widows went to the mountains to give birth and leave their offspring to the cruelty of the animals that eat them, and they die without baptism,” because Hernández threatened to imprison the widows.Footnote 55 The audiencia also noted that Hernández had hidden over 500 Indians from the tribute rolls and the labor draft. On August 14, 1713, the audiencia prosecutor recommended arresting the governor for holding the Indian widows “in notable slavery.”Footnote 56 The audiencia imprisoned Hernández until the special Indian court released him on August 9, 1715. The widows obtained relief from the courts of justice in this case.Footnote 57

Various judges offered redress to commoners such as the Indias. The indigenous pueblos (polities) elected alcaldes (magistrates) for one-year terms to resolve conflicts within their communities. The alcaldes meted out six to eight lashes or a day in jail for missing mass, public drunkenness, or other minor offenses. They could not mutilate or execute culprits, however. The alcaldes ordinarios (magistrates) of the Spanish-speaking towns were also selected annually by the municipal council. Most of these magistrates had little formal education in the law and ruled by drawing on local customs. Separate from them were the district judges, usually called alcaldes mayores in New Spain. They heard trials of the first instance and the appeals against the sentences of the lower magistrates. Natives could also sue their alcaldes mayores and other Spaniards in the special Indian court in Mexico City, while all others turned for relief to the audiencia, composed of civil and criminal judges and prosecutors.Footnote 58

Litigants could also request the Council of the Indies in Madrid to reexamine rulings. The Council usually read up on a petition or an appeal and then issued a consulta (consultation). The king, queen, or their senior ministers saw the consulta and agreed or ordered changes. Their notaries scribbled a royal decree on the margins of the consulta and passed them back to the Council. The Council then issued a real cédula (royal provision) to the litigants, communicating the decree and attaching the king’s name and seal. Sometimes the Council or the king confirmed the request of one party, and the notaries merely copied the original petition into the real cédula. The Native city of Tlaxcala, for example, complained about two lackadaisical attorneys at the Indian court and asked for a greater role for its procurators. The real cédula from 1685 cited the complaint and settled the issue.Footnote 59

Novohispanos generally expected to a point that these councilors and judges acted as impartial public persons. They should maintain their independence in court and ideally behave “without personal interests and zealous in the service of God, king, and the public.”Footnote 60 For this reason, the crown prohibited audiencia judges from marrying local women or owning property in their districts. At the same time, the boundaries of good conduct depended on the perspective, and most people knew that royal ministers also served their own interests and those of their powerful social networks.Footnote 61

The networks composed of intermediaries negotiated power and stitched together the empire. They also often skewed trials and shaped the information flowing to Madrid.Footnote 62 Analyzing these actors in Oaxaca, Yanna Yannakakis maintains that “the Bourbons harbored significant antagonism toward Native intermediary figures (and intermediary figures of all sorts) whom they perceived as corrupt and inimical to the efficient functioning of Empire.”Footnote 63 This may well be the case in the largely Native region of Oaxaca, yet such a claim will be more difficult to prove for the whole empire. The first Bourbon king arrived in Spain in 1701 and his descendants ruled New Spain until its independence in 1821. The dynasty and their changing ministers seldom pursued a consistent policy toward any social group during this long century, and instead altered their aims according to expediency and convictions.Footnote 64

In fact, the royal governments usually leaned heavily on local and regional power brokers. Loyal service usually mattered more than ethnic identity, although some minorities often faced harsher treatment. In fact, the Bourbons frequently preferred Basque and Navarrese intermediaries over Castilians from central Spain. In the eighteenth century, the crown also needed indigenous partners to wrest away parishes from the regular orders or relied on elites in provincial cities to bypass the powerful social bodies in Mexico City.Footnote 65 For these reasons, ministers forged alliances with suitable patrons, brokers, and clients to advance or to stall reforms. Historians have chiseled out the importance of these go-betweens during the historiographical turn toward social networks starting in the early 1970s. The local connections played a key role in achieving political goals, and both reformers and the opposition used them.Footnote 66

Audiencia judges frequently belonged to differing networks, and their varied interests and perspectives often defied a direct translation of a social desire into a sentence. Tamar Herzog maintains in this regard that any “distinction between institution and society was virtually inexistent” in Quito.Footnote 67 Some audiencia judges undeniably married or befriended locals and carried the conflicts riddling the communities into the courts. Yet the law, opposing allegiances, the need to forge compromises, and the threat of informants mattered too in New Spain. The crown knew of the antagonisms among ministers and packed the audiencia with several judges and prosecutors. These ministers could well belong to opposing camps and happily reported the failings of their adversaries to Madrid. In addition, the audiencia judges distinguished themselves from the rest of society. Their legal knowledge gave them great prestige, and they insisted on their elevated role at public events. In addition, men of “cloak and sword,” that is, people of non-judicial training, often governed the courts, assisted by a slew of notaries and other officials. They frequently brought differing perspectives to the table. Madrid acted as an arbiter among the competing interests, reducing the ability of small groups to hijack the courts.Footnote 68

As conflicts unfolded, notaries, judges, and other vassals readily gave the crown important information about the far-flung realms. For example, court notaries occasionally wrote down the prosecutor’s legal opinions, the majority vote of the judges, and the dissenting viewpoints in lawsuits. Vassals also sent streams of petitions to Madrid. By doing so, they provided the kings with the best available information about local circumstances. “Knowledge is power,” the English jurist Francis Bacon (1561–1626) argued earlier, and the Spanish queens and kings relied on competing stories rising up from below to discern loyal from disloyal servants. Far from having absolute control, the kings and queens used their knowledge to curb powerful elites, rein in abuse, advance their clients, and implement reforms that slowly transformed the empire.Footnote 69

In addition, “soft steering” promoted a sense of duty among the ministers. This cultural manipulation consisted of discursive methods, symbols, and rational arguments. The crown exhorted ministers to comply with the norms of good conduct, and these exhortations reverberated among the public. Over time, social values changed and the talk about the ministers’ usefulness to the public good sank in. This does not mean that all functionaries followed suit right away or that the crown expected them to do so. Yet soft steering incrementally altered the behavior of ministers, because a broad audience in New Spain agreed with these changes.Footnote 70

The kings claimed absolute power to pursue such policies. Absolute power, in this sense, meant that the kings could change or ignore the law of the kingdom when necessary, which was not the same as controlling the minutiae of everyday lives. The cities of the empire, for example, continued to issue their own statutes and live by their own customs. Nonetheless, the Roman Digest posited that any decision of the emperor became law. The Siete Partidas incorporated this rule, assigning absolute power to the kings of Castile who served akin to the emperor in their realm.Footnote 71 The cities of Castile agreed, at least sometimes. A representative of the Cortes (parliament of estates) of 1523 held that “laws and customs are subject to the kings who can make and unmake them at their will.”Footnote 72 In practice, the kings issued edicts without the consent of the Cortes, and for this reason, an attorney in Mexico City agreed that the king was “prince and legislator” of the empire.Footnote 73

In addition, the idea of jurisprudence differed from today and included royal governance. The Spanish kings were the senior judges of the empire. They issued laws, levied taxes, defended the realm, and wielded “the force of the sword to punish evil-doing people.”Footnote 74 Other kings claimed similar authority. The Portuguese jurist Antonio Sousa de Macedo ably summed up this point in 1651. For him, jurisprudence consisted not only of adjudicating complaints “as the incompetent believe,” but referred to the entire political organization of the empire.Footnote 75

The expanding royal authority, meanwhile, often encountered robust resistance from the great Councils, power elites, or popular groups. In 1693, during a period of bitter feuding, the Council of the Indies reminded King Charles II that “absolute power does not reside in the Catholic character, only ordinary justice governed by reason.”Footnote 76 The Council at that point attempted to protect its own prerogatives by demanding that the king end the sale of office appointments. Earlier, the theologian Francisco Suárez (1548–1617) had devised a contract theory according to which the kings depended on the will of the people. Other scholars praised the mixed sovereignty shared among the people, the nobility, and the crown, which also countered the idea of absolute royal power.Footnote 77

Trust among ministers buttressed resistance against undesirable reforms or punishments, but it could also be betrayed. Judges and notaries, for example, had rehearsed passing on bribes and other favors for generations. They confided that all participating parties continued the profitable practices. Trust ran deep and it glued together the ministers, often encumbering meaningful prosecutions of malfeasance. Nonetheless, Francisco Garzarón obtained valuable testimony by threatening effective punishments for recalcitrant ministers. When the suspects saw that Garzarón succeeded, at least some changed their tune to save their skin. Garzarón, for example, charged a criminal judge with seizing confiscated assets from jailed suspects. The criminal judge blamed his notary for the malpractice, giving Garzarón’s visita the necessary testimony to discipline the wayward official.Footnote 78

In many cases, the crown tried to compromise with groups that disregarded royal rules or expressed their dissatisfaction, instead of penalizing them. When the moral economy of communities was violated and the channels of communications with the authorities blocked, for example, anger could boil over into revolts. Natives on these occasions threatened, evicted, or even killed their alcaldes mayores and their assistants. The state typically sought to appease the involved parties during these conflicts. The crown sent ministers to hear the Native complaints, and they pardoned most participants. They also sternly warned the Indians to return to peace and harmony or face the rigor of justice.Footnote 79

Yet the crown could also call on visitadores to hand down harsh punishments, and these visitadores often drew on significant political support for their aims. The early modern state relied on collaboration to some extent, and the visitadores succeeded mostly when they counted on imperial and local acquiescence or agreement.Footnote 80 A visitador adjudicated the Indians of Tehuantepec who rebelled in 1660, for instance. The visitador denied the appeals and executed five death sentences. The scholarship has decried this process as a “mockery of justice.”Footnote 81 Similarly, culprits later impugned the verdicts of Garzarón’s visita, because his “rigor and harshness,” was “exorbitant and opposed to the dispositions of the law.”Footnote 82 Yet many early modern Spaniards saw these visitas as the king’s duty to correct wrongs. An entire genre of literature affirmed that the king served as the spouse of the republic and “shepherd and father” of his vassals. These works described the republic as a body and the king as its head who closely observed any disorder. According to the Jesuit Andrés Mendo, for instance, the “most noble sense of the head are the eyes, and the prince has to be all eyes, vigilantly watching the appropriate behavior of his subjects. Nothing can flee from his gaze.” The king named visitadores – whose title referred to seeing – to “defend the law and the flock.” Many novohispanos agreed.Footnote 83

The king wielded the economic power to appoint the visitadores who bypassed the courts of justice. In the early modern view, the term economic frequently referred to matters of the home. The king had the duty to keep his house in order, and this task extended to the entire kingdom. The visitadores served this end. A real cédula from 1750, for example, underlined the necessity of the “economic and political power … for the public tranquility of my vassals.”Footnote 84 This authority was separate from the ordinary course of justice, and the visitadores usually operated on their own to mend disorders. They resembled the king’s favorite ministers and the juntas (committees) that convened for special purposes. They resolved challenges quickly, because they did not wait out the lengthy deliberations of the courts or Councils. For this reason, historians have traditionally interpreted the visitas as tools of reforming the nascent states.Footnote 85

Next to the economic power and justice, the king’s grace was the third domain of power. The king assuaged harsh judicial rulings and modified human fate by his acts of grace. He awarded vassals for loyal conduct and elevated commoners into the nobility. The king also voided the illegitimacy of birth of others and pardoned culprits. Early modern people mostly considered grace a necessary complement to justice and not as an arbitrary abuse of royal power. Andrés Mendo, for instance, praised the king of Portugal for commuting death sentences into banishments to overseas realms. The king, in this way, combined the utility of settlers in the territories with the grace of easing tough punishments.Footnote 86

1.3 Empire in Transition

The Spanish empire comprised a string of kingdoms, principalities, and provinces. While the court in Madrid was the ultimate arbiter of conflicts, the empire did not merely consist of one great center from where political and social importance cascaded toward the fringes. In fact, several core kingdoms, among them New Spain and Peru, rivaled Castile in economics, population, and patronage in varying degrees. These core kingdoms also mattered, because other realms or territories attached to them in different ways. These realms or territories tended to be less densely settled and they often depended economically or politically on the core kingdom. Nevertheless, even these realms cherished their own rights and customs and preserved their local governance.

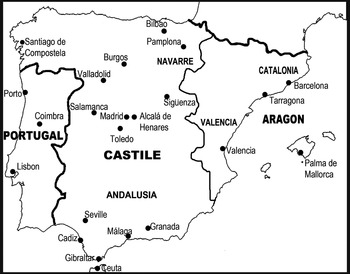

In the period 1650–1755, the crown tightened supervision over these kingdoms and territories with varying degrees of success. This process advanced in part, because Spain had to fend off the other great powers, including England, France, Habsburg Austria, and the Netherlands. These rivals tried to seize territories, fortresses, or trade from the empire. The crown mobilized ever larger resources to counter the threat. Madrid attempted to increase tax revenue from privileged groups or social bodies and channel more funds to the military. The queens and kings intensified their rule by incrementally curbing the autonomies of the kingdoms and limiting the jurisdictions of the social bodies. By and large, the process defined the boundaries of the provinces more clearly and advanced universal principles that applied to all individuals. These changes did not occur on a linear trajectory and many reforms remained piecemeal. Rulers rarely followed a master plan, and, instead, they usually responded to particular challenges with specific solutions.

Map 3 The Iberian Peninsula in 1700.

New Spain traveled on a similar pathway. Colonial Mexico originally integrated into the polycentric Spanish empire after the conquest of the Aztec (Mexica) empire in 1521. Agriculture and silver mining expanded, and New Spain grew into an economic power house. The regions north of the old Aztec empire gravitated into the novohispano orbit. The viceroys in Mexico City, for example, monitored the military and the finances in New Galicia and its capital Guadalajara, located north of the Mexico City audiencia limits. In addition, the viceroys sent funds to the Caribbean isles and the Philippines to sustain fortresses and the missions of the religious orders. These regions did not formally belong to the viceroyalty – despite what textbook maps show – because the viceroy, the audiencia, or the tax collectors had no formal say there. Yet social networks, personal communications, and trade thrived. By sending money, merchants, mercenaries, and mendicants, New Spain gained informal leverage in these regions.Footnote 87

In addition, New Spain consisted of social bodies that enjoyed great autonomy, lived by their own rules, and mediated royal power. These social bodies comprised the guilds of shoemakers and goldsmiths, African confraternities associated with churches, or municipal councils, for instance. These social bodies shaped the lives of their members, who were usually born into a hierarchical group and rarely left their community without severing most ties to other members. The social bodies frequently had jurisdiction over their members, who tended to have a “porous” identity, because they usually made decisions in conjunction with their social bodies.Footnote 88

The social bodies competed to some degree with the ordinary justice system represented by alcaldes mayores and audiencias. The judges of the various social bodies applied norms of different provenance and therefore a “jurisdictional pluralism” reigned at that time. Ecclesiastical courts, for instance, offered conflict resolution on a broad swath of issues to clergy and even non-clergy, while soldiers, postal clerks, and merchants often litigated in their own separate courts. Similarly, the indigenous pueblo (polity) exemplified a social body. The pueblo largely lived by its own unwritten customs, and the indigenous alcaldes settled the conflicts of their community according to their values. Most social bodies had also forged their own explicit or implicit contracts with the king, and these agreements safeguarded privileges and internal organization. The central government in Madrid had limited say in their affairs and often cared less about the details.Footnote 89

The variety of arrangements and competing jurisdictions declined, as the cycles of reforms accelerated in the seventeenth century. Some royal governments attempted to intensify – not necessarily centralize – authority. They often viewed the autonomy of the social bodies with some suspicion and preferred ruling individuals instead of negotiating with the social bodies. In addition, the kings and their reformist ministers aimed at undercutting the role of the core kingdoms and integrating them more fully into the state. While this was not a predictable process, the crown took a step into that direction between 1707 and 1716. The crown removed four viceroys from the Spanish peninsula, abolished most provincial institutions, and introduced Castilian public law in the kingdoms of the crown of Aragon.Footnote 90

These changes could encourage economic initiatives, create wealth, and provide for greater individual self-determination. For this reason, the kingdoms even favored reform under circumstances. New Spain, Peru, and Catalonia, for example, had long called for opening up the sclerotic Atlantic trade system. The trade fleets left Seville in southern Spain every year and traveled to New Spain and Panama/Peru to deliver European merchandise. The commercial oligopoly allowed merchants in Seville to charge excessive mark ups from the Americans. In the early eighteenth century, several governing coalitions in Madrid confronted the commercial oligopoly and successively eased up trade restrictions. The fleets declined in importance, while nimble registered ships sailed from various peninsular ports directly to the Americas.Footnote 91

Yet much remained a “stubbornly incomplete process” during which imperial patterns prevailed. Conservative governments and their alliances backtracked on reforms. For example, the king’s first minister fell in 1754, and the commercial oligopoly flexed its muscles once more. In the following year, the new government suppressed the registered ships going to New Spain and restored the fleet on this route.Footnote 92 This shows that a king or his dynasty rarely pursued grand designs leading “inexorably from empire to nation-state” and the process was far from a smooth and steady process.Footnote 93 The king’s ministers and their local allies considered their options when challenges arose, and they chose specific solutions rather than crafting a consistent policy. Sometimes, the kings even curbed the autonomy of one entrenched social body by creating competing institutions. In 1717, for example, the crown established a new viceroyalty in New Granada (modern Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador) to heighten control and dampen the influence of the powerful viceroy, audiencia, and oligarchy of Lima (Peru). In the second half of the eighteenth century, Manila in the Philippines, Guadalajara, and Veracruz also obtained consulados (merchant guilds) to rival the guild of Mexico City. Privileges and immunities of social bodies dissolved slowly and unevenly. Lasting change came only by enlisting local and imperial support, or at least acquiescence.Footnote 94

At other times, the goals were oppressive, striking at indigenous self-administration, eradicating linguistic diversity, or raising taxation to new levels. Many historians of indigenous communities consider these changes as destructive to Native culture. Nancy Farriss, for example, argues that the Bourbon dynasty assaulted the traditional social order of Yucatan, and some scholars emphasize the exploitation of New Spain as a whole.Footnote 95 These are all excellent contributions, but these changes also had a different meaning.

Dismantling social bodies and curbing the privileges of old noble families could well benefit other groups that vied for community influence. For example, the elections for Native alcaldes and governors continued from pre-contact times, although they became incrementally more competitive. Tenochtitlan, the leading indigenous parcialidad (neighborhood) in Mexico City, demonstrates this shift. Its governors traditionally grew up in the parcialidad and descended from the Aztec royal lineage. In 1573, however, a well-educated non-noble from out of town won the election for governor. Social origin as selection criteria weakened further and direct appeals to the constituency mattered more. Candidates offered “entertainments, banquets, gifts, and extravagant election promises” to gain the vote by the 1650s. By this time, commoners began serving the indigenous municipal offices in greater numbers.Footnote 96 Competitive elections could well be popular among some middling and popular sectors.

In addition, the Enlightenment increasingly frowned upon treating social groups differently. Consequently, the separate laws for Natives were more and more seen as discriminatory and withered in the eighteenth century. The position of the protector of Indians disappeared in 1735, for example, and the incumbent joined the audiencia as a criminal judge. The Indian court also dissolved in the 1790s. Defense lawyers for Indians obtained better salaries to improve judicial standards and moved their trials into the audiencia.Footnote 97

Indigenous peoples did not necessarily resent these changes if they did not conflict with their own interests. They often assimilated elements of the prestigious Hispanic culture – just as Hispanic urban culture borrowed heavily from Indians. Even the state’s aim of spreading the Spanish language and mores among all inhabitants of the empire could be attractive for many when also offering full citizenship. Although this change strikes us now as innocuous to cultural diversity, a similar process was at play throughout Europe. For these reasons, the assessment of eighteenth-century empire should not be too somber. While not denying that groups suffered, reforms also came about with prodding from below. The analysis of corruption in this book bears this out.Footnote 98

Conclusion

The law and social practices both mattered and evolved in the Spanish empire. Six pillars of law contributed to the legal pluralism in broad strokes. These were the combined Roman and canon law and their evolving interpretations, known as the ius commune. Spanish legal practitioners directly or indirectly drew on the ius commune for many years until the eighteenth century. Notaries or attorneys, for example, sometimes cited ius commune doctrines such as the tacit consent to defend the excessive fees they had charged from litigants. Judges reconciled these concepts with biblical tenets and natural law, understood as the reasonable principles of ordering justice. The local customs and the royal law also played major roles. In addition, the judicial plurality engendered legal populism. Novohispano commoners and elites had relatively easy access to the courts and representation. The courts heard the involved parties in conflicts and ideally meted out sentences following general principles of justice. The king reviewed the process as the supreme arbiter, and the justice system was generally believed to be legitimate.

In the sixteenth century, humanist lawyers began challenging that matrix. They critically assessed the history of the Roman collection and furthered the judges’ arbitrio to adjudicate criminal trials. In the late seventeenth century, inklings of enlightened thinking appeared on the intellectual horizon and the royal law gained further influence in the courts. Proponents of natural law suggested abandoning the legal pluralism in favor of an entirely new code built on systematic and unequivocal principles. Some experts even proposed discarding the ius commune and the royal law collections. Yet writing a full-fledged code for the entire empire failed, and the royal Law of Castile and the Law of the Indies continued to enshrine justice until the independence of New Spain in 1821.

When the social networks excessively skewed decisions, the king sent visitas to restore the proper working of justice. The networks consisted of patron–client relationships that tied together the social and ethnic groups of the empire, and local intermediaries played a crucial role in exchanging resources. The kings and queens relied on power brokers to gain information and advance reforms. Sometimes, these networks became too influential and clogged communication. Visitas then reviewed the institutions, penalized miscreants, and helped reward meritorious vassals. The visitas usually handed down swifter verdicts, because they avoided the slow grind of the ordinary courts. The suspects in these investigations often deplored the harsh and extra-judicial rulings against them, and the visitadores could well abuse their vast powers for personal vendettas. Nonetheless, many novohispanos supported Francisco Garzarón’s investigation, and he and other visitadores relied on local agreement or acquiescence for their advances.

In the period under consideration, the empire slowly segued toward a state organized around territorial principles and a stronger role for individuals rivaling the semi-autonomous social bodies. These social bodies, such as the indigenous pueblo and the municipal councils, had sustained society and adjudicated the conflicts among their members. The social bodies fiercely defended their privileges and traditions, yet the crown sought to undermine their great autonomy and that of the realms as a whole. This process advanced piecemeal and was marked by ad hoc responses to specific challenges. Sometimes the social bodies or conservative elites imposed competing solutions or forced a return to old practices. Many facets of empire survived and change came only when significant sections of society agreed on reforms.