After Enlightenment

A technological gap has opened in the interval of more than two centuries since the original publication of Kant’s text. Literary production has undergone radical changes that contest print’s predominance during the German Enlightenment. The socio-technological assemblage of print actors and technologies seems to have long given way to an apparatus, or apparatuses, of new literary actors, objects, and techniques that properly define the digital present.Footnote 1 Consider the fact that today’s authored manuscripts tend not to be handwritten, but instead are often typed on the computer with its installed word processor. The dominant writing technologies of professional authors are no longer pen and paper, but rather the keyboard and screen, and the latter’s virtual space is a computer graphic with its own medial-material conditions of possibility that differ from those of the paper page.Footnote 2. Alongside the making of manuscripts, the mass (re)production of books has technically departed from the procedures extending from Gutenberg’s system of movable type. Whereas the turning out of books used to rely on hand, steam and electric letterpresses, it now occurs mainly through offset lithographic and digital printing. In the case of electronic books, or e-books, no equivalent method for producing physical paper copies in bulk is required. Any digital device with a screen and the requisite software may access the e-book.Footnote 3 Where printed books are made searchable and viewable on the Internet via mass digitisation projects, the techniques of photographic scanning and data processing via optical character recognition software are relied upon for the remediation of print. In terms of skills and instruments, or technē and technology, the making of identical book commodities has long departed from the ‘first assembly-line’Footnote 4 of Gutenberg’s letterpress.

Though at present we may still be surrounded by print publications, such printed matter are often not products of the eighteenth-century print machinery that generated the Berlinische Monatsschrift, nor even the predominant literary medium in our media ecology. The ambiguity surrounding print’s place in the digital environment, its seeming endurance and extinction, was observed by Jay David Bolter at the turn of the new millennium: ‘Although print remains indispensable, it no longer seems indispensable: that is its curious condition in the late age of print. Electronic technology provides a range of new possibilities, whereas the possibilities of print seem to have played out.’Footnote 5 In line with Kittler, I would stress that the rise of digital media is so indebted to print technology and its crucial role in the history of engineering that it would be misleading to represent digital pathways as distinct from the possibilities of print.Footnote 6 Nonetheless, the uncertain status of the print medium in contemporary culture is haunted by the possibility that the medial-material conditions for literary (re)production worldwide have already mutated, and are probably continuing to diverge, from those of late eighteenth-century Germany.

Further work should be done to diagrammatise the digital machinery or network that presently defines literary and cultural production. The print machinery mapped out in this book is but a stimulus for future projects on the continuously evolving medial infrastructure in which information is generated, disseminated and experienced by humans with their technologies. It is perhaps only by taking the material dimension of literature and other cultural forms seriously, as opposed to neglecting or suppressing it, that authorship and copyright studies may redress the proprietary bias in the law’s present treatment of authors and works. To conclude this study of and alongside Kant, I perform a medial analysis of a digital text, namely the exemplary work of Wikipedia, likewise focusing on its paratextual materialities and implications on copyright’s proprietary account of authorship. This may serve as a starting point for research into the present – and future – of authorship and copyright.

Multitudinous Authorship of Wikipedia

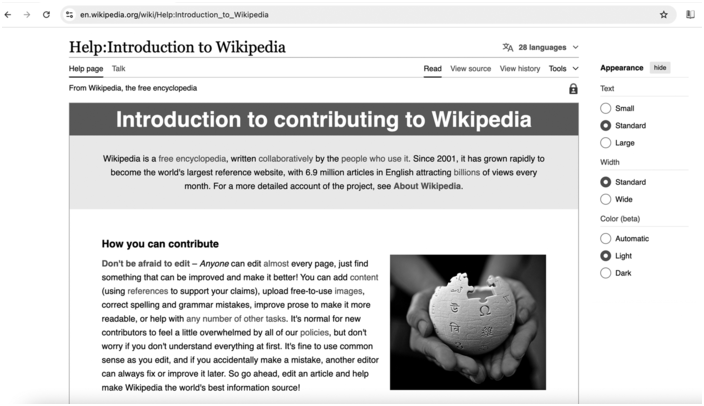

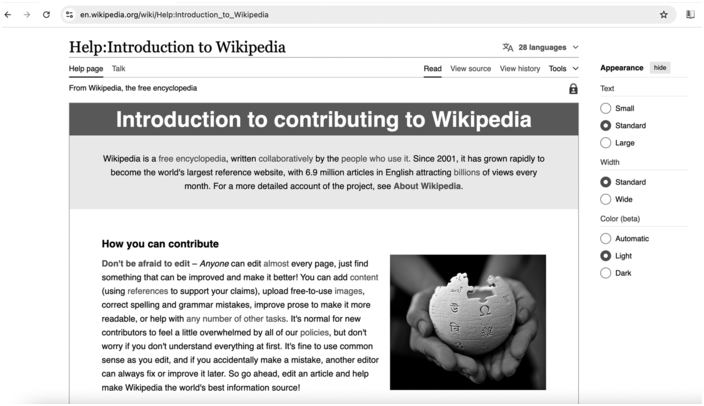

Visibly more so than a printed text bearing an author’s name, the digital encyclopaedia Wikipedia stands at odds with the Romantic conception of the author as creator of the unique literary work. The home page of the English website reads, ‘Welcome to Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia that anyone can edit.’Footnote 7 With ‘edit’ substituting for ‘write’, the putative origins of the literary work in the writer and their act of writing gives way to an always-already secondary, derivative act of revision without end. Clicking on the hyperlink attached to ‘anyone can edit’, we are led to one of its many ‘help pages’ introducing and encouraging the socially inclusive activity of ‘contributing to Wikipedia’ (see Figure C.1).Footnote 8 Viewers are assured ‘[not to] be ‘afraid to edit – Anyone can edit almost every page; just find something that can be improved and make it better!’Footnote 9 The exclusivity of the Romantic author qua genius, whether in the Wordsworthian construct of the exceptional artist or in the Fichtean guise of the giver of singular form, is displaced by an ethic of inclusion that defines the digital demos of Wikipedians. On the right of the passage is a photograph of an anonymous pair of hands carefully holding an unfinished jigsaw-sculpture of a globe comprised of written scripts from multiple languages, as if emblematising the ongoing work of the Wikimedia Foundation to build a world representative of its culturally diverse participants. Both the text and the image are effectively deployed to convey and reinforce the collaborative and collective authorship of the world’s largest encyclopaedia.

Figure C.1 Main page of Wikipedia.

Wikipedia registers in its name the technological basis of its public or multitudinous authorship. A wiki is a piece of software, first launched in 1995, whereby digital users may create and edit any page of a website using a browser.Footnote 10 The editorial speed and efficiency that the content management system grants to collaborative projects, too, is nominally registered: the Hawaiian phrase ‘wiki wiki’ means ‘superfast’.Footnote 11 Wikipedia adopts a wiki-based program, MediaWiki, for its articles, discussions and other collectively constituted pages.Footnote 12 Initially developed to expedite the creation of content for another online encyclopaedia authored by academic experts, Wikipedia quickly outgrew, outlived and displaced its host Nupedia.Footnote 13 As of August 2024, the English Wikipedia alone has 6,879,979 articles, averaging 533 new articles per day.Footnote 14 There are 47,927,179 registered users, with a minority of 115,260 having made edits within the last 30 days.Footnote 15 The Wikipedia community, whose members are known to one another as ‘Wikipedians’, is comprised of volunteers who, variously, edit and maintain the articles and contribute to community discussions.Footnote 16 In lieu of expertise, the world’s largest online encyclopaedia is continually made and remade by a multitude of persons operating with and alongside their digital devices and programs.Footnote 17

Wikipedia’s distinctively collective model of authorship has not escaped the attention of copyright and intellectual property scholars.Footnote 18 From a legal perspective, the Wikipedia project is of interest for its ambivalent relationship with the copyright system, at once resisting the law’s proprietary frame of understanding and reinforcing it through the very mechanisms adopted to overcome its limits. In spite of the perpetual revisability of its pages, Wikipedia presently affirms, as part of its legal policy, the extension of copyright protection to its articles by virtue of the international copyright regime. ‘The text of Wikipedia is copyrighted (automatically under the Berne Convention) by Wikipedia editors and contributors and is formally licensed under one or several liberal licences.’Footnote 19 For permissions to be granted for the public’s reuse of the articles, including their copying, distribution and modification, of the articles, the text itself is legally viewed as consisting of original literary works in which their editors, as author-creators, hold copyright. A dual-licencing regime, composed of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-SA) and the GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL), and enforced through the terms and conditions on which Wikipedians agree to have their pages published, ensures the public’s unmonetised access to these works. Creative Commons licences have evolved as a critical response to the recent encumbering of cultural forms, particularly online works, with increasingly restrictive private property rights that limit or obstruct the public’s access to those works.Footnote 20 And yet, the licenced works belonging to the ‘Creative Commons’, those freely circulating in the public domain, are subjected to certain conditions in the licences. In the instance of Wikipedia’s CC BY-SA, such conditions include the need to attribute the original authored work, and to similarly bind future uses of the ‘derivative’ work. Further, the Creative Commons regime not only presumes and legitimates copyright law but further bases its issuance of permissions upon the latter’s proprietary system of rights.Footnote 21 In so sustaining the derivative regime, Wikipedia and other users of such licences could be said to inhibit alternative imaginings of literary and cultural regulation that do not take the possessive-individualist author-owner as their fundament.

Notwithstanding Wikipedia’s embedment in the copyright regime, my claim is that the processes by which its pages are made and unmade fundamentally challenge the proprietary model of authorship, inviting, even necessitating, its rethinking. The principle and fact of collective participation in the digital-encyclopaedic production, which relies on a multitude of contributors interacting with the virtual platform, brings into focus the insufficiency of copyright’s fiction of the work’s origination in an independent, personal author. Rather than yielding piecemeal revisions to copyright law’s doctrines, tests, and threshold requirements,Footnote 22 the inherent sociality and multiplicity of literary production suggests the need to move beyond the proprietary matrix in which the literary work is presently imagined, that is, as a mere literary commodity governed by an economic logic of rewards and incentives. Despite the anonymity of their production, the digital works of Wikipedia bear the potential to be rethought as a contemporary information technology that, not unlike Kant’s printed mater, responds to the profoundly social problem of information overload.

A Digital Machinery behind ‘Author’

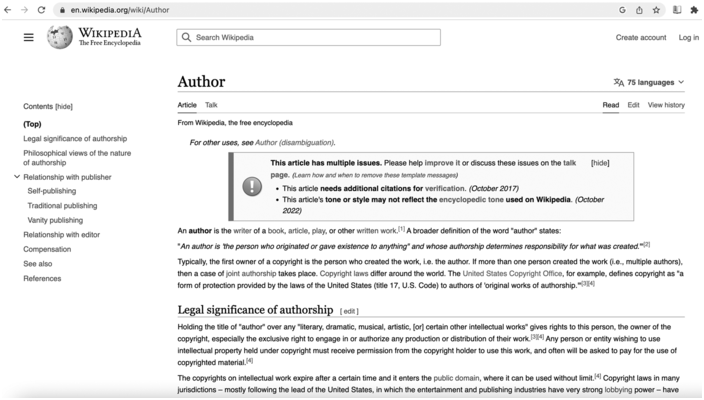

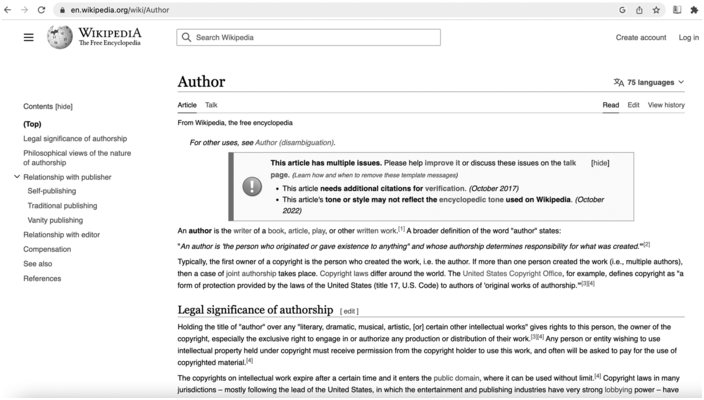

Let us return to the interface of Wikipedia and its constitutive text and paratexts. If we type ‘author’ or ‘authorship’ in the search bar at the top of any Wikipedia page, we shall find an article on the matter that discloses some of the socio-technological bases on which the authorship of Wikipedia proceeds (see Figure C.2).Footnote 23 Before one even begins to read the propositions on authorship therein gathered, a caveat in the form of a text box announces its presence with a white exclamation mark in an orange circle to the left of the text. Apparently, the article has ‘multiple issues’, including its lack of citations for ‘verification’ (that is, for users to check that the information therein presented derives from a ‘reliable source’Footnote 24) and its failure to adopt the mandated ‘encyclopedic’ or ‘formal tone’.Footnote 25 Instead of simply retrieving the information on the page, the reader is asked to ‘improve it’ or to discuss the issues on the ‘talk page’, both options facilitated with hyperlinks to the editing and discussion tabs of the article. Rather than present its content on authorship as stable, reliable knowledge, the article points to its state of incompletion and the means of resuming its production.

Figure C.2 Author page of Wikipedia.

The article discloses various facets of authorship that already exceed copyright law’s focus on authors as creators and first owners of intangible works. Though barely more than a hundred words, its opening paragraph offers four understandings of authorship whose corresponding citations doubly point to the multiple textual sources from which it is pieced, and to the bibliographic system that binds together Wikipedia and other publications, print or digital. Foregrounded, first, is a commonplace understanding of the author as a literary author, one authorised by the Cambridge Dictionary, a reference book that meets Wikipedia’s requirement of verification. ‘An author is the writer of a book, article, play, or other written work [Footnote 1: a hyperlink to the dictionary website].’Footnote 26 As if cognisant of the medial limits of this entry, the article provides a second definition that identifies the author as the personal point of origin of any work. It further ascribes to this creator responsibility for the work, thereby recognising an ethical understanding of authorship. ‘A broader definition of the word “author” states: “An author is ‘the person who originated or gave existence to anything’ and whose authorship determines responsibility for what was created” [Footnote 2: a reference to Frank N. Magill’s Cyclopedia of World Authors (1974)].’Footnote 27 Finally, the paragraph concludes by restating various aspects of the legal account of authorship, including the law’s recognition of authors as first owners of copyright in the work, the doctrine of joint authorship, the possibility of doctrinal variations across copyright regimes and the US account of copyright as protecting authors of ‘original works of authorship [Footnotes 3 and 4: two references to a digitised version of a print circular from the United States Copyright Office, and to Title 17 of the United States Code]’.Footnote 28 The footnotes attached to these four accounts of authorship – text-based, originalist, ethical and legal – evince the chain of relations between texts from which the paragraph emerges. Rather than reinforce the myth of proprietary authorship, these references give credence to Barthes’ view of the text as ‘a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture’.Footnote 29

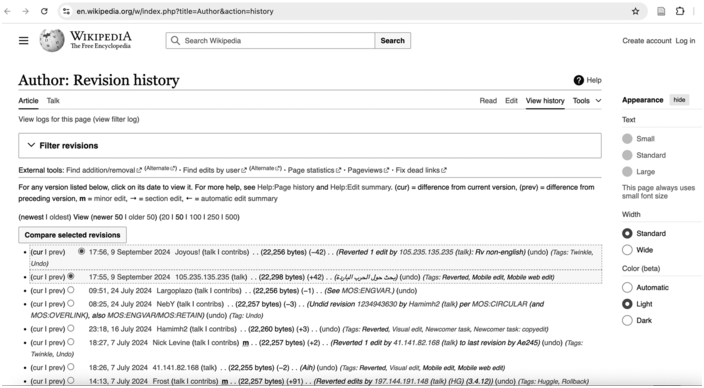

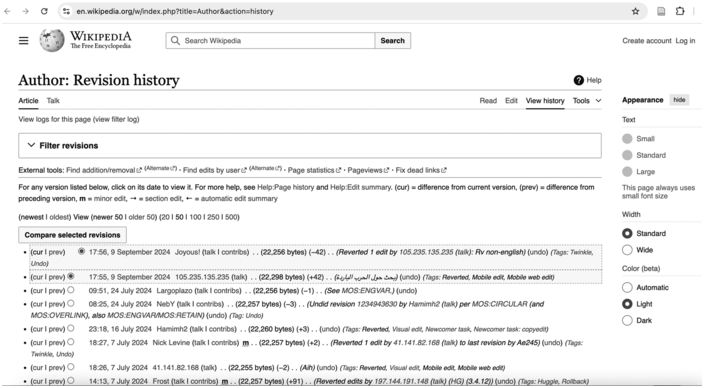

A digital machinery precedes, and is registered in, the Wikipedia article on authorship. Clicking on the ‘View history’ tab of the article allows us to glean that it has been edited more than 1,500 times since 30 August 2001 (see Figure C.3).Footnote 30 Known to Wikipedians as an authoritative record of all the page edits made and unmade, each timestamped and attributed to its user-contributor, this ‘Revision history’ sheds light on the history and process of its production. A quick scan of the page would reveal the absence of need for the contributors – including ‘HeyElliott’, Daask’, and ‘Largoplazo’ – to base their usernames on their legal or formal names. Wikipedia does not verify the legal identities of its users.Footnote 31 This policy (or lack thereof) has allowed Wikipedians not only to retain their anonymity as virtual users but also to use false credentials to buttress their contributions to articles and discussion pages.Footnote 32 Indeed, the contributors may not even be human. On 11 November 2022, ‘ClueBot NG’, an approved program that makes ‘repetitive automated or semi-automated edits that would be extremely tedious to do manually’,Footnote 33 undid an act of vandalism by one ‘Brian.Reinwald’, who had, gratuitously, added a version of his own name to the page. Wikipedia allows bots to assist and automate edits of its pages, provided that the bots’ users have sought the requisite approval to do so.Footnote 34 Instead of performing independent acts of creation, Wikipedia editors operate with and alongside machines to advance the project.

Figure C.3 Revision history of the author page of Wikipedia.

Scrolling down the page and clicking on each of the revised entries appearing in reverse chronology, we shall find that the four definitions of authorship were proposed by different users at different points in time. These definitions did not even appear in the same sequence or in the same form but had been inserted in a non-linear way and altered by multiple hands. When the page was first created on 30 August 2001 by ‘Rmhermen’, there was but a bare description of the author as ‘a person who writes some text’ and the generic examples of ‘poetry or prose, technical [text] or literature’.Footnote 35 The more substantial, and corroborated, definition based on the Cambridge dictionary entry only appeared recently: on 20 October 2022, input by one ‘Naomikrate’.Footnote 36 Even then, it was worded differently. Instead of concluding with the phrase ‘or other written work’, the sentence ended with ‘mostly written work’. Whereas the present phrase strictly restricts authorship to that of textual production, the initial phrase recognised that non-cultural productions could well fall within its semantic ambit. It was only on 28 December 2022, with a grammatical edit by ‘Quin Mas’, that the definition of authorship shifted from one that was merely textually centred to another that is, now, exclusively textual.Footnote 37

Before Naomikrate had made their edit, the ‘second’ and ‘third’ definitions affixed with the encyclopaedia reference were already present on the page. They appeared as early as more than a decade ago. On 16 June 2012, one ‘Wahrmund’ (German for ‘true mouth’) added the reference to Magill’s 1974 Cyclopedia of World Authors.Footnote 38 Because the same definition sans encyclopaedia reference had already been present on the page, it remains unclear how far the definition was, indeed, supported by Magill’s work. To clarify this it would be necessary to consult Magill’s work. But no other Wikipedian has questioned Wahrmund’s edit. As regards the fourth legal definition of authorship, a version of it had appeared less than two weeks before Naomikrate’s intervention. On 8 October 2022, ‘Tropicalkitty’ had furnished the definition as the opening paragraph of the first section entitled ‘Legal significance of authorship’. But this definition would be moved to the untitled introductory paragraph above by Naomikrate on the same day (20 October 2022) and at the same time (06:39 UTC) as when the latter had inserted the Cambridge dictionary definition.Footnote 39

As systematically registered on the history page, the article on authorship has undergone multiple revisions, involving both human users and non-human digital technologies, over two decades. The opening paragraph, alone, has entailed the contributions of no fewer than five Wikipedians, who had relied upon the pre-existing reference books, in digital and print forms, along with the citation system, to produce the definitions. Our retrieval of such a history is premised on our own embedment in the digital machinery that made the article. There could have been no ‘authoring’ of the page on ‘author’ without the digital machinery of Wikipedia. And it is this very same socio-technological apparatus that renders the work endlessly revisable. In contrast to copyright law’s fiction of a stable literary work with a determinable point of origins, the work of any Wikipedia article is, in principle, unfinished. Each article opens unto the future, inviting further contributions from any connected to its generative machinery.

Towards a Media History of the Digital Encyclopaedia

The ethics of authorship arises as an important yet unresolved question in the Wikipedia article and the paratextual indices of its making. In the third definition of authorship stemming from Magill’s Cyclopedia, responsibility for the work is tied to its origination in the author. Not simply a basis on which to grant proprietary rights, authorship is suggested to bear an ethical dimension that remains undetermined. As discussed in Chapter 4, Kant had attempted to (re)assert his presence ‘in’ the text through his printed authorial name as a technique for managing information overload during the German Enlightenment. For Kant, responsibility extended to accounting for the interventions made and published under one’s authorial name. Wikipedia departs from the printed work as understood by Kant in its absence of requirement to specify an editor’s legal name or to verify their credentials. Composed and endless subject to revision by a multitude of authors, human and non-human, the digital text does not lend itself to be ethically assessed from the standpoint of the personal author. On what other grounds, then, might the responsibility for Wikipedia’s making and its effects in the world be understood?

In step with the preceding analysis of Kant’s essay, I claim that the ethics of Wikipedia authorship should be understood in reference to its material form and historical conditions of possibility. Specifically, a media history of Wikipedia, as a digital text that extends from a literary-scientific tradition of the encyclopaedia, could clarify its ethical role in the digital public sphere. The genre of the encyclopaedia dates back to as early as the first century AD.Footnote 40 Often regarded as the first surviving encyclopaedia of Western civilisation (though this perception has also been contested for its anachronism),Footnote 41 Pliny the Elder’s Historia Naturalis is an illuminating precedent. Composed of thirty-seven books (ten published in Pliny’s time and the remainder by his namesake nephew), the ancient Roman inventory of details and facets of the natural world, ranging from cosmology to geography, humanity, zoology, botany, medicine, minerals, art and more, has been read in two principal ways that may inform our understanding of the present digital text.Footnote 42

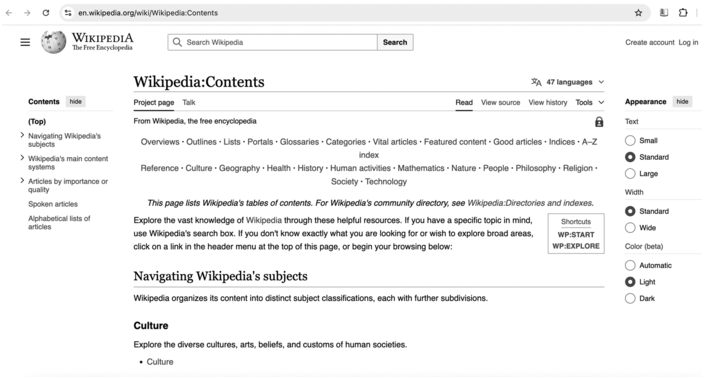

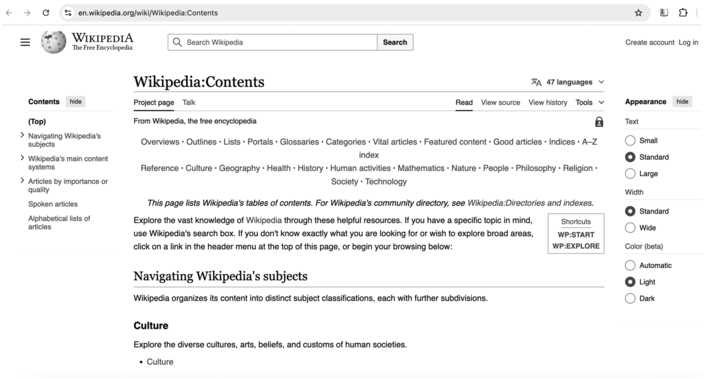

First, from an informational perspective, the Historia Naturalis functions as technology that exhaustively compiles in a single site the innumerable records of natural knowledge, sorting them into lists of structured items in its numbered volumes. In so doing, the ancient encyclopaedia anticipates by two millennia Wikipedia’s project of summarising knowledge, general and specialised alike, and presenting them in variously categorised articles. By virtue of differences in medial form, the paratexts facilitating information retrieval from the Historia Naturalis and Wikipedia differ. Originally appearing in the form of Roman scrolls and subsequently reproduced in codex forms leading up to modern print editions,Footnote 43 the Pliny text utilises a summarium, a list in the first volume outlining the contents of the remaining thirty-six volumes, to guide the reader.Footnote 44 For instance, a reader interested in learning about the making and use of papyrus and parchment in antiquity could be directed by the list to the thirteen volume, particularly to those passages pertaining to ‘Papyrus; employment of paper; when begun; how manufactured; 9 kinds; mode of testing papers; defects of papers; paper-glue’.Footnote 45 Unlike the Historia Naturalis and modern print encyclopaedias, Wikipedia does not have a static list or table of contents as part of its front matter. Instead, its online articles are presently grouped and divided, at the first level, into twenty-four categories that are not unified under an overarching principle of classification, as if recalling Borges’s monstrous animal taxonomy of the Chinese encyclopaedia (see Figure C.4).Footnote 46 Listed horizontally, and across two lines, the categories begin with some foregrounding content that are valued for meeting high editorial standards (‘Vital articles’, ‘Featured Content’, ‘Good articles’), which are abruptly followed by other indexical categories (‘Overviews’, ‘Outlines’, ‘Lists’, ‘Portals’, ‘Glossaries’, ‘Categories’, ‘Indices’, ‘A-Z index’, ‘Reference’), as if recognising the insufficiency of the present index. Only thereafter do we see some common subject categories (‘Culture’, ‘Geography’, ‘Health’, ‘History’, ‘Human activities’, ‘Mathematics’, ‘Nature’, ‘People’, ‘Philosophy’, ‘Religion’, ‘Society’, ‘Technology’). Clicking on any of these hyperlinked categories will lead us to other pertinent pages composed of more hyperlinked words and phrases that, in some way, relate to the initial term. From ‘Culture’, we could move to ‘literature’ as a subcategory including both ‘fiction’ and ‘non-fiction’; before turning, for instance, to the latter page that provides another monstrous list of genres, forms and formats, including the ‘encyclopedia’; the clicking of which could direct us back to ‘Wikipedia’ as one of the ‘digital and open-source versions in the 21st century … [that have] vastly expanded the accessibility, authorship, readership, and variety of encyclopedia entries’.Footnote 47

Figure C.4 Contents of Wikipedia.

Perhaps more so than the horizontal list of twenty-four categories, accessibility to Wikipedia’s articles is secured by the search bar at the top of every Wikipedia page. As demonstrated in our search for the article on ‘author’ and ‘authorship’, the search function allows the reader to find the pertinent page or pages relating to any given term. Indeed, external search engines such as Google Search act as one of the chief gateways to Wikipedia. Presently, a Google web search query on ‘author’ produces about 5,850,000,000 results. Out of these, the first result to appear immediately after the definition in Oxford Languages is a link to, and excerpt from, the Wikipedia page on authorship. Search engines and digital indices composed of, and building upon, hyperlinks – that is, cross-references that afford immediate access to relevant items of information – are now some of the key devices by which Wikipedia and other sites present themselves to their reader-users.

Before further clarifying the place of Wikipedia in the medial history of information, we should note, too, that Pliny’s text has been incisively critiqued to be a product, and an agent, of ancient Roman imperialism.Footnote 48 Approached not simply as a compulsive aggregation of facts but rather as a cultural artefact arising from within a place at a certain time, a reference book such as Pliny’s catalogue of natural knowledge could index the cultural tendencies and geopolitics in which it participated. As a classicist Trevor Murphy has demonstrated, the information recorded in Historia Naturalis reflect the values of its author and the Roman culture to which he belonged. Far from being dead, or rather in spite of his absence from the text à la Barthes, the author leaves behind in it a ghostly presence, in the form of material residues of the epitextual background in which he and his privileged contemporaries operated. Consider, for instance, Pliny’s account of the accomplishments of human race in the seventeenth book, in which the Roman statesman Cicero, amongst others of his glorious countrymen, received superlative praise:

But what excuse could I have for omitting mention of you, Marcus Tullius? or by what distinctive mark can I advertise your superlative excellence? by what in preference to the most honourable testimony of that whole nation’s decree, selecting out of your entire life only the achievements of your consulship? Your oratory induced the tribes to discard the agrarian law, that is, their own livelihood; your advice led them to forgive Roscius the proposer of the law as to the theatre, and to tolerate with equanimity the mark put upon them by a distinction of seating; your entreaty made the children of the men sentenced to proscription ashamed to stand for office; your genius drove Catiline to flight; you proscribed Mark Antony. Hail, first recipient of the title of Father of the Country, first winner of a civilian triumph and of a wreath of honour for oratory, and parent of eloquence and of Latin literature; and (as your former foe, the dictator Caesar, wrote of you) winner of a greater laurel wreath than that of any triumph, inasmuch as it is a greater thing to have advanced so far the frontiers of the Roman genius than the frontiers of Rome’s empire.Footnote 49

Pliny’s catalogue of the natural world, whilst beginning from the heavens and ending with a marvel at its minerals, had Rome as its evaluative centre. The achievements of the Roman empire, and those of its celebrated public figures, are selectively monumentalised in the reference book. As Murphy has sharply noted, Pliny’s text institutionalised the common knowledge of his fellow citizen-readers of ancient Rome, presupposing and perpetuating a community of readers with shared values and endorsements of their civilisational achievements.Footnote 50 A critical archaeology of the reference book could disclose the Roman imperialist bias that informs, and is supported by, its production and transmission of knowledge.Footnote 51

This second political perspective on the Pliny text is no less valuable to our present assessment of the digital encyclopaedia. Wikipedia purports to be a radically democratic project to which any user can contribute as editor. But do the actual composition of editors, and the contents of their articles, indeed reflect and align with the declared ethos? Despite our characterisation of the Wikipedia authorship as based in a collaborative multitude, for some time now critical literature on the encyclopaedia has disclosed its geographical, racial and gender bias.Footnote 52 According to recent surveys, less than a quarter of Wikipedians are women, and the article contents tend to be gendered, provoking the holding feminist ‘edit-a-thons’ to correct the bias in coverage.Footnote 53 In 2015, a New Statesman journalist compared the edit counts of two Wikipedia pages on pornographic actresses and female poets, which emblematises the encyclopaedia’s poor representation of topics of feminine interest: ‘The list of poets has been edited 600 times, by near 300 editors. The list of female porn stars is a newer page but over 1,000 editors have edited it more than 2,500 times.’Footnote 54 Let us add that the ‘author’ page of Wikipedia neither refers to any related work by a woman author nor recognises the struggles of women writers in literary production and regulation. Wikipedia’s problematic gendering has recently been traced to its infrastructure: its policies, logics and codes.Footnote 55 For instance, Wikipedia’s overlapping policies of ‘neutral point of view’, ‘no original research’ and ‘verifiability’ have tended to restrict the production of content to a mirroring of pre-existing sources and publications that, in themselves, reflect and contribute to male bias. Dependent on a gendered body of knowledge that remains to be fixed, Wikipedia is conditioned to perpetuate its bias and, particularly in the light of its popularity, to reinforce the marginalisation of women in knowledge production. In an unequal world, these policies act as the means by which the Wikipedia justifies its irresponsible contributions to gender inequality and other social problems. A fuller account of the ethical dimension of the encyclopaedia would have to address its necessary embroilment in emancipatory struggles of the present.

To conclude this analysis, Wikipedia may be further compared with some of its key eighteenth-century print predecessors to deepen our understanding of its informational function. As helpfully outlined by Wellmon, the European Enlightenment saw the purposeful making and conceptualisation of encyclopaedias to manage the surfeit in print, some key examples of which could be understood as evidencing three distinct generic models.Footnote 56 The first model is a cartographic understanding of the encyclopedia as a text that helped readers to navigate the surfeit of print. Denis Diderot’s and Jean d’Alembert’s co-edited Encyclopédie (1751–1772) was an organised abbreviation and collation of ‘all knowledge that now lies scattered over the face of the earth’.Footnote 57 The project aimed to produce not so much an exhaustive record of knowledge as a practical survey of it for learners. As understood by its co-editor d’Alembert, the Encyclopédie acted as ‘a kind of world map’Footnote 58 that oriented its readers to the terrain of the various existing knowledge systems and their potential points of intersection. Its other co-editor Diderot understood the value of their cartographic work in a future of ever-accruing print publications that would inhibit humanity’s learning:

As long as the centuries continue to unfold, the number of books will grow continually, and no one can predict that a time will come when it will be almost as difficult to learn anything from books as from the direct study of the universe. It will be almost as convenient to search for some bit of truth concealed in nature as it will be to find it hidden away in an immense multitude of volumes. When that comes, a project, until then neglected because the need for it was not felt, will have to be undertaken.Footnote 59

Diderot’s insistence on the difficult project of securing writers to contribute to the Encyclopédie over the two decades from 1751 evidenced his belief that the text was a solution to the escalating problem of print proliferation in his time.

The second model of the encyclopaedia is a systemic or formal understanding of the text as presenting the underlying logical structure that unified true claims to knowledge. Advanced in opposition to exhaustive projects of encyclopaedias (many of which collapsed by the early nineteenth century),Footnote 60 the systemic standpoint sought not to be comprehensive in its content and cross-references but to clarify the systemic unity of knowledge. Building upon Kant’s concept of the system as ‘the unity of the manifold cognitions under one idea’,Footnote 61 Wilhelm Traugott Krug advanced an encyclopaedic account of the sciences based on what he regarded as their basic structure.Footnote 62 ‘Krug organized sciences according to common elements that were preestablished as the basic characteristics of a science: their basic concepts, content, boundaries, relationships to other sciences, current states, and the methods and literary aids for engaging them.’Footnote 63 The encyclopaedic impulse was to uncover, or perhaps to project, a rational order of articulable categories to which knowledge belonged.

Whereas the first and second models of the encyclopaedia still revolved around the print medium as the principal means of knowledge dissemination, the third ethical model of the encyclopaedia was evidenced in teaching practices increasingly adopted in German universities during the 1780s and 1790s. From this perspective, the encyclopaedic drive towards uncovering the systemic unity of knowledge and sciences was understood as an ideal scientific disposition to be imparted to and embodied by persons. Recalling the emphasis in Pliny’s text on providing a ‘general education’ (enkyklios paideia) to its readers, ‘encyclopedic lecture courses’Footnote 64 introducing the ethos that purportedly motivated all the sciences were offered by the University of Jena and other German universities towards in the last two decades of the eighteenth century. These lectures stressed, and enacted, the university’s function of cultivating students as scholars interested in, and competent to, generate scientific knowledge.Footnote 65 ‘The study of the science of sciences excites, enlivens, and maintains the drive to infinite expansion, as well as perfected unity and the organic mutual determination of all knowledge. It gives all students a purposeful direction.’Footnote 66 August Wilhelm Schlegel stressed the importance of this scientific spirit within the wider medial and social context in which such encyclopaedic lectures were given.Footnote 67 Understood not simply as a curated repository of knowledge but rather as a subject’s propensity for the assimilation and production of knowledge, the encyclopaedia was similarly advanced as a solution to the problem of the expanding book trade and the superficial modes of reading and it encouraged. As Schlegel observed,

Twice a year the great book fair flood (not even counting the smaller, monthly floods with which the journals are washed up) casts on land the newly birthed books in great balls from out of the great ocean of writerly shallowness and banality. These are then ravenously devoured by the great mob of the reading world, but without affording any nourishment. And they are just as quickly forgotten and fade away into the filth of the reading libraries and with the next trade fair the whole cycle begins again.Footnote 68

To respond effectively to the surfeit of print, Schlegel argued that individuals had to possess and enact the encyclopaedic disposition, or what he understood to be the ‘method and spirit of the sciences’,Footnote 69 which would allow them to grasp the organic unity of the sciences while contributing to their development in time.

From the distance of the twenty-first century, the three models of the eighteenth-century encyclopaedia, particularly the second formal version, may seem quite removed from their present digital counterpart. No search for systemic unity is apparent in the multitudinous making of more than six million Wikipedia articles, each often the product of innumerable revisions that, instead, work on the less ambitious long-term collective task of improving its readability, coherence and cross-checkability. Wikipedia’s editing policy page presents a typical image of an article’s history:

[One] person may start an article with an overview of a subject or a few random facts. Another may help standardize the article’s formatting or have additional facts and figures or a graphic to add. Yet another may bring better balance to the views represented in the article and perform fact-checking and sourcing to existing content. At any point during the process, the article may become disorganized or contain substandard writing.Footnote 70

The human contributors are often not systems-oriented philosophers, but instead ‘amateur volunteers’Footnote 71 who edit pages in their spare time.

Likewise, in respect of the cartographic and ethical models, Wikipedia only subscribes to each in limited ways. The article on ‘author’, which includes references to Barthes’ and Foucault’s key works, may well act as a starting guide to the field on authorship and copyright. However, its utility as a map is presently restricted by its scope. As foregrounded in another orange-coloured ‘dispute tag’Footnote 72 dating back to August 2021, the section on ‘[p]hilosophical views on authorship’ restricts itself to what the editor has called ‘postmodern’Footnote 73 theories of authorship, and thus ‘needs expansion’.Footnote 74 Its omission of female and feminist perspectives on authorship and literary production, on the other hand, is not at all mentioned. Further, Wikipedia’s disconnection from the university, which tends to prefer instead its system of peer review, diminishes its role in the training of students to embody what Schlegel and the contemporaries celebrated to be the encyclopaedic spirit. Often dismissed by academic experts as lacking rigor in its production, Wikipedia may not seem to exemplify the sort of scientific ethos, the ‘method and spirit of the sciences’,Footnote 75 advanced by the late eighteenth-century German philosophers.

And yet, across the divide of more than two centuries, Wikipedia joins hands with the eighteenth-century encyclopaedic publications and teaching practices to address a familiar problem of information overload. In the present ‘information age’Footnote 76, it is not simply a glut of print that confronts the learner but also a supersaturation of information relayed through digital-communicative channels.Footnote 77 The staggering sum of six million Wikipedia articles may seem, of itself, to contribute to the problem of excess. But in perceptual terms, the on-screen appearance of the pertaining Wikipedia page with at least a basic understanding of the subject matter whose key word the user had input in Google Search (or Wikipedia’s search bar) does mitigate the issue of information superabundance. A working map, possibly even directing the reader-user to some of the peer-reviewed publications preferred by universities and scholarly experts, is available at the fingertips of the digital user.Footnote 78 In so connecting to, and selectively foregrounding, the bibliographic network of textual publications, the Wikipedia article helps to orient readers to the field of authorship. Such references, if followed through, could act as the means by which to disclose and displace the ideological and socio-political limits of the Wikipedia text.

If Wikipedia eschews the traditional markers of expertise such as credential controls and peer review, it is because the encyclopaedia prioritises the democratisation of knowledge production. In lieu of the truth-seeking ethos of eighteenth-century encyclopaedic practices, the Wikipedia community embodies, and advances, a mass-participatory ethos of authorship where anyone may contribute to the formation and development of its pages. Kantian critical debate is not absent from the project but rather informs both the continual revision of its articles and the disputes recorded in the discussion tabs. The evolution of the authorship page from one comprised of only two lines to a multi-sectioned piece with supporting references was accompanied by more than 1,500 edits made in response to the limits of prior versions. If we click on the ‘talk’ tab of the article, we shall find various suggestions, offered by other Wikipedians, on ways in which the article could be expanded. To cite three of these: ‘Another term, someone could elaborate on is “collective authorship”. Thanks.’ ‘It would be useful to further comment on authorship with regards to the use of pseudonyms. An important question in that field would be, how the adoption of a (non-narrator) persona by a writer affects the author of his/her text: Is a person writing once under his/her real name and once under an adopted name still the same author; or is it two different authors that are writing and just happen to spring from that same person?’ ‘The lead image was changed from a portrait of Mark Twain to an image of Toni Morrison, then reverted. I believe the original edit was constructive for a few reasons … I suggest that the change to Morrison be restored.’ All three suggestions identify certain limits of the article – namely, its focus on sole authorship, onymous authorship and male authorship – and call for their displacement. It is through such discursive contributions, and the accompanying editorial acts, that Wikipedia’s digital machinery is immanently steered to enhance the quality of its articles and exercise its function of organising knowledge amidst information overload. A democratic model of critical public debate, taking place within and documented by the digitally mediated pages of Wikipedia, reflects the mass-participatory ethos of the twenty-first-century encyclopaedia: ‘the free encyclopedia that anyone can edit’.Footnote 79

Following the guide of the recent feminist-technological literature, further assessments of Wikipedia’s function as a contemporary information technology that democratically inflects Kant’s project of enlightenment should look closely at its constitutive infrastructure. How far do the policies of allowing Wikipedians to make their contributions without verifying their legal identities or credentials, and of requiring instead that these contributions be traceable to existing publications, advance its function of assisting user-readers with the problem of information overload? Do the presentation of distinct usernames and, in the instance of users without accounts, the publishing of their IP addresses, fulfil the same function of ensuring authorial accountability as the printed authorial name in Kant’s account? Should the mass-participatory ethos of Wikipedia be allowed to override the concern for individual authorial responsibility? Or ought more controls be put in place to cultivate such responsibility? How far should Wikipedia’s existing policies, logics and codes be preserved in the light of feminist, racial and decolonial critiques? Could the digital encyclopaedia further evolve to accommodate alternative modalities of authorship? A media history of Wikipedia, one adequate to address these deeply ethical questions, remains to be written.

Contemporary euphoria and anxieties surrounding the evolution of the internet, its promise of disseminating knowledge to the masses and its threat of dispossessing readers of their rational faculties, are preceded by similar concerns with print technology expressed in the late eighteenth century. Kant and other contributors to the Berlinische Monatsschrift understood that the print machinery had to be strategically steered to advance practices of critical public debate essential to individual and collective emancipation. Their interventions in the name of enlightenment, a project that depended on the interaction between humans and print media, called for a renewed attention to those medial-material bases for recording and transmitting knowledge. The historical case of authorship in the German Enlightenment suggests that we should neither romanticise nor demonise technology, but rather critically cultivate our contact with it.Footnote 80 Such cultivation would require that we develop a medial-theoretical and -historical competence to situate contemporary knowledge forms such as Wikipedia, alongside and against their predecessors, so as to clarify their continuities and differences. More so than the proprietary idiom of copyright, it is this medial-material literacy that enables us to respond to the ethical stakes and demands of authorship in the digital present.