Introduction

How do politicians in advanced democracies get away with violating political norms? This article contributes to our understanding of norm erosion processes in advanced democracies by zooming in on the political conflicts that norm violations set in motion. Although their formal institutions have remained stable over the last decades, many advanced democracies are currently characterized by a norm‐eroding politics (e.g., Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013). Political norms, like mutual tolerance between and respect for political opponents, acceptance of election outcomes or restraint in the exercise of formally granted political power, are a subcategory of political institutions. Gretchen Helmke and Steven Levitsky (Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004, p. 727) define political norms as ‘socially shared rules, usually unwritten, that are created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels [emphasis added]’. Scholars often cast political norms in functional terms, that is, they perceive them as problem‐solving devices of political systems (Helmke & Levitsky, Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004). Political norms contribute to smoothing the political process, managing fundamental democratic tensions and preventing gridlock (Azari & Smith, Reference Azari and Smith2012; Helmke & Levitsky, Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004; Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Lieberman et al., Reference Lieberman, Mettler, Pepinsky, Roberts and Valelly2018). Against this background, the erosion of norms is an important and potentially far‐reaching challenge for democracy.

Norm erosion in advanced democracies has led to a growing interest in incremental forms of democratic backsliding (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016; Carugati, Reference Carugati2020; Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Waldner & Lust, Reference Waldner and Lust2018; Weyland, Reference Weyland2020). While the literature has begun to identify the socio‐political changes that prompt certain politicians to engage in norm violations, less is known about the conflictual interactions between norm violators and defenders, especially in Western European countries. Studies that analyze norm erosion processes from an agency perspective overwhelmingly focus on scenarios where norm violators are already in government and can violate norms from a position of power (Cleary & Öztürk, Reference Cleary and Öztürk2020; Gamboa, Reference Gamboa2017; Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Miller, Reference Miller2020). We argue that this focus is too narrow given that norm erosion processes in advanced democracies begin earlier, that is, when norm violators are not (yet) in government and must confront a powerful political establishment that seeks to defend the democratic status quo.

This article studies this early stage of the norm erosion process in multiparty democracies. Political challengers start the process by violating a norm and subsequently engage in a conflict with the political establishment, which verbally sanctions them. We argue that whether norm defenders successfully stop norm violators early on or whether norm violators can avoid punishment largely depends on norm violators’ strategic approach. We show that verbal sanctions tend to be ineffective, if not counterproductive, in situations in which norm violators (i) make ambiguous provocations and (ii) can credibly portray themselves as democratically acceptable actors, thereby dispelling attempts to stigmatize them as undemocratic. Norm violators who employ this strategy turn the tables on norm defenders by portraying their sanctions as a form of ‘excessive retaliation’ that constitutes a norm violation in itself. Our findings contribute to the literature by revealing how norm violators can inflict damage on democratic norms already from a position of institutional weakness, that is, before they eventually gain power and challenge democratic practices ‘from within’. Moreover, we complement research that focuses on the structural conditions for democratic stability and backsliding by providing original insights into the conflictual interactions that connect structural conditions to a state of eroded norms.

The article proceeds as follows. The first section demonstrates that the growing literature on norm erosion in advanced democracies has not yet given sufficient attention to the crucial stage of norm erosion processes in which norm violators operate as political challengers. The second section conceptualizes the interactions between norm violators and defenders as a conflictual sequence whose outcome largely depends on norm violators’ strategic approach. The third, empirical, section tests the theoretical argument with the help of a comparative case study design. We perform diachronic comparisons of conflicts over norm violations in the typical case of Austria, and subsequently assess the theory's external validity by conducting a synchronic comparison with conflictual interactions in the least‐likely case of Germany (Gerring, Reference Gerring2004; Rohlfing, Reference Rohlfing2012). The fourth section embeds our findings within the wider debate on norm erosion and democratic backsliding and outlines avenues for future research. The last section reflects on the strategic dilemma faced by political actors who are determined to defend democratic norms.

Conflicts over norm erosion in advanced democracies

Like Waldner and Lust (Reference Waldner and Lust2018), we understand the erosion of democratic norms to be an important aspect of democratic backsliding – a process that often precedes more severe damage to formal democratic institutions. We define norm erosion as an incremental process that starts with a clearly visible norm violation. If the norm violation does not remain an isolated case but instead sets a precedent for further violations, the violated norm gradually loses its ability to influence the behaviour of political actors (Streeck & Thelen, Reference Streeck, Thelen, Streeck and Thelen2005, pp. 19−22).

The literature has long focused on democratic breakdowns in weakly institutionalized, new democracies (WINDS). Scholars have only recently also begun to study gradual forms of backsliding in advanced democracies, primarily in the United States (e.g., Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Mickey et al., Reference Mickey, Levitsky and Way2017). There are empirical reasons for these shifts. Classic coups d’état, executive coups (i.e., coups where elected leaders refuse to step down) or election‐day vote fraud, were long the most frequent forms of democratic breakdowns; however, they have declined in frequency in recent years (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016). On the contrary, incremental forms of backsliding, such as executive aggrandizement or the strategic manipulation of elections, remain unchanged or have become more frequent (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016). For many years, scholars primarily studied democratic breakdowns in WINDs, and they only analyzed breakdowns in the (now) consolidated group of (mostly Western) democracies as historical cases (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2014; see also Capoccia & Ziblatt, Reference Capoccia and Ziblatt2010).

The large majority of the growing literature on norm erosion in advanced democracies focuses on structural changes that explain why certain politicians or parties are increasingly eager to violate democratic norms – from the case of Donald Trump in the United States to Boris Johnson in the United Kingdom, to the many far‐right parties in Western Europe, such as the Alternative for Germany (AfD). A central finding of this literature is that under certain political circumstances, such as mass polarization, voters are less critical, if not appreciative, of norm‐eroding behaviour (Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Hahl et al., Reference Hahl, Kim and Zuckerman Sivan2018; Luo & Przeworski, Reference Luo and Przeworski2019; Miller, Reference Miller2020).

While the literature has increasingly illuminated the socio‐political developments that provide a favourable context for norm erosion to occur, including in advanced democracies, it strongly focuses on the United States and its heavily polarized two‐party system, while research on multiparty advanced democracies, especially in Western Europe, remains scarce. Moreover, while recent work has analyzed right‐wing populist discourses and the taboo‐breaking that they often entail (Wodak, Reference Wodak2015), the existing literature usually neglects the actual conflicts that norm violations set in motion. Studies that provide a detailed examination of conflicts over norm violations overwhelmingly examine situations in which norm violators are already in government, and are thus very powerful, while norm defenders are in the opposition (Cleary & Öztürk, Reference Cleary and Öztürk2020; Gamboa, Reference Gamboa2017; Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Miller, Reference Miller2020). An important exception is Capoccia (Reference Capoccia2001; Reference Capoccia2005), who studies the legal reactions of democratic rulers against extremist challengers. As we will argue in the theory section, the pro‐democratic establishment is usually not yet able to, or at least prefers not to, adopt legal strategies if challengers only violate informal norms.

We suggest that the norm‐violating practices of political challengers and their conflictual interactions with the establishment deserve attention for at least three reasons. First, while scholars have rightly cautioned against prematurely coding minor violations of democratic norms as cases of backsliding (Waldner & Lust, Reference Waldner and Lust2018), this recommendation should not lead us to limit the analysis of norm erosion processes to the stage where the norm violators already dispose of significant institutional power and begin to violate core democratic norms, or where democratic norms are already so severely damaged that breakdown is imminent. To do so would mean to ignore the actions of norm violators such as Germany's AfD, France's Front National, or the Netherlands’ Party for Freedom until they would form part of the government. Second, most norm violators do not creep into power but already engage in norm violations during their time as political challengers (Cinar et al., Reference Cinar, Stokes and Uribe2019). Third, the transformation of party systems that is currently taking place in many advanced democracies creates an adverse power distribution for norm violators (Przeworski, Reference Przeworski2019). A greater number of parties makes it more likely that norm violators will initially be confined to one or more challenger parties. Gaining an outright electoral majority by capturing a single party, like in the case of Donald Trump and the Republican Party in the United States, is the exception rather than the rule in advanced democracies. These reasons suggest that many norm violators therefore initially operate from a position of institutional weakness and confront a powerful political establishment that, together with a vigilant media, a vibrant public sphere and an effective judiciary, can identify and punish their norm violations.

In this scenario, overcoming the incipient pushback from established actors can be considered to be a bottleneck condition for the norm erosion process to start. Politicians eager to violate norms (for a variety of structural reasons) would ultimately be discouraged from continuing to do so if established actors’ sanctions would be effective. In order to gain a comprehensive understanding of norm erosion processes, it is crucial to examine how norm erosion can occur in situations where norm violators operate as political challengers and confront a powerful political establishment.

Then and now: Two conflictual scenarios

Our theory suggests that norm erosion has become possible in many multiparty democracies because of an altered conflict between political challengers as norm violators and established elites as norm defenders. We conceptualize this conflict as a sequence that leads from an initial act of norm violation (X) through various intermediate steps (conflictual interactions) to Y (norm protection or norm erosion). We expect that the strategy norm violators (manage to) employ crucially influences the outcome of the sequence. The remainder of the theory section specifies the activities (A) that constitute the conflictual sequence and details the impact norm violators’ strategy choice has on its outcome.

A1: A political challenger provokes established politicians and parties by violating a norm

Political challengers start the process of norm erosion by deviating from the behaviour that a norm prescribes either because they expect to gain votes from it or because they genuinely prefer non‐democratic governance. There have been numerous political norm violations in advanced democracies in recent years and, depending on the norm in question, these violations can take many forms. Most violations defy mutual tolerance between political opponents, shared understandings of political correctness and established political procedures. Crucially, most of the initial actions taken by norm‐violating challengers can be expected to be verbal provocations of the establishment rather than severe violations of democratic norms. This is simply because challengers do not have the institutional power to violate more vital norms, such as, the strategic manipulation of elections or the suppression of political opponents.

A2: Established politicians and parties defend the norm by sanctioning the violator

Norm defenders can only uphold informal norms if they sanction deviations from them (Helmke & Levitsky, Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004). Established politicians and parties react to norm violations because norms help to uphold their institutional power, they believe in them or because their voters request that they defend democratic norms. We thus expect that established actors meet norm violations with various kinds of sanctions, such as stigmatization, anti‐populist rhetoric or outright ostracism (Helmke & Levitsky, Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004). Concrete sanctions include the naming, shaming and blaming of the violator, calling for an apology or the violator's resignation from public office or the launching of (more) formal sanctions.

A3: The norm violator tries to endure sanctions

Norm violators are unlikely to simply ignore these sanctions because doing so could be dangerous for them. As Helmke and Levitsky (Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004, p. 733) put it, ‘informal sanctioning mechanisms are often subtle, hidden, and even illegal’. This injects uncertainty into the calculus of norm violators, as they cannot be sure of the type or extent of the sanctions that a particular violation will trigger. We therefore expect that norm violators will try to reframe their initial provocations and fend off accusations of anti‐democratic behaviour.

Ambiguity and leveraging democratic credentials

Whether defenders successfully stop violators (A2), or whether violators successfully fend off accusations of anti‐democratic behaviour (A3) depends on the public credibility of their respective statements. The conflictual interactions between norm violators and defenders constitute a ‘framing contest’ (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009) during which both parties compete over the interpretation of a norm violation. We argue that currently many norm violators in advanced democracies proceed strategically by combining ambiguous (and thus difficult‐to‐unmask) provocations (also known as ‘calculated ambivalence’, see Wodak, Reference Wodak2015) with the leveraging of previously acquired democratic credentials. This strategy benefits norm violators as it provides them with an opportunity to refute ‘claims of anti‐democratic or racist extremism’ (Mendes & Dennison, Reference Mendes and Dennison2020, p. 6).

In recent years, new political parties have emerged by campaigning on previously overlooked issues such as immigration, the environment or, more generally, the perception of a political system as dysfunctional (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005). As Ivarsflaten (Reference Ivarsflaten2006) shows, in the case of many far‐right parties – the primary norm violators in present‐day advanced democracies – this expansion of the issue space has provided them with the possibility of establishing a reputation as democratically acceptable actors by accumulating a legacy of democratically uncontroversial statements and policy positions (a ‘reputational shield’). Moreover, many far‐right parties have tried to become democratically legitimate by cutting off their links of origin in hard‐right, often neo‐fascist groups and milieus. Emblematic for this effort is Marine Le Pen's expulsion of her own father from the Front National, which he had founded and long led.

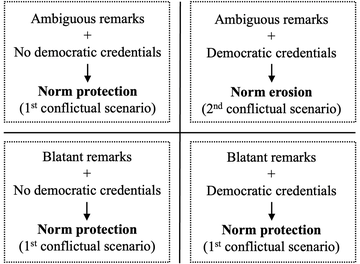

Provided that the anti‐democratic or extremist nature of their statements and actions is sufficiently ambiguous, norm violators can emphasize their democratic credentials and point to previous situations in which they acted in democratically acceptable ways to brace themselves against accusations of anti‐democratic extremism. In doing so, norm violators can turn the tables on norm defenders and portray their sanctions as norm violations in their own right, thereby prevailing in the framing contest over the initial norm violation. We therefore consider the combination of ‘ambiguity’ and ‘democratic credentials’ to facilitate norm erosion because ambiguity initially creates a ‘he‐said‐she‐said’ situation and democratic credentials subsequently make norm violators’ reframing attempts more credible. This implies that if one of these factors is absent, norm protection would be the more likely outcome (see Figure 1 for a graphical overview of the possible scenarios).

Figure 1. Possible conflictual scenarios.

We can thus formulate and contrast two conflictual scenarios:

When norm violators act blatantly and/or cannot leverage previously acquired credentials,

norm defenders can clearly identify norm violations ( A1) as such by sanctioning the violators ( A2). Verbal sanctions act as an effective marker of anti‐democratic behaviour and have no negative side effects for norm defenders. Therefore, norm violators’ attempts to relativize their norm violations appear implausible ( A3). The norm violators are likely to be ostracized or forced to apologize, and thus discouraged from committing further norm violations. The norm violation remains an isolated incident and the violated norm remains intact ( Outcome: norm protection).

When norm violators employ the strategy of ambiguity and democratic credentials,

the conflictual interactions between norm violators and norm defenders on the occasion of a norm violation ( A1) can be expected to take a different turn. Norm violators can more credibly fend off attempts to stigmatize and ostracize them by reframing the norm violation. Verbal sanctions ( A2) are now counterproductive because norm violators can portray them as norm violations in themselves ( A3). Norm violators are less likely to be ostracized or to apologize and are thus encouraged to engage in further norm violations. The norm violation sets a precedent that is followed by similar or even more severe norm violations that gradually weaken the norm ( Outcome: norm erosion).

We expect these conflictual scenarios to primarily apply to multiparty systems where there is a ‘general’ public (and media sphere) that supports democratic norms (thus considering them to be a valence issue; see Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020) but where there are also significant ‘reservoirs’ of democratic frustration and disaffection (Norris, Reference Norris2011). It is in these settings that norm violators are in a position to increase their electoral support by sending an ambiguous ‘double message’ to their core supporters and to the general public.Footnote 1 In the following, we illustrate and assess the validity of the two conflictual scenarios with the help of a comparative case study design.

Research design

The empirical analysis proceeds in two steps. The first step performs a within‐unit diachronic comparison of conflictual interactions to contrast and test the plausibility of the previously outlined scenarios. The second step uses a cross‐unit synchronic comparison of conflictual interactions where norm violators employ the strategy of ambiguity and democratic credentials to test the external validity of the second scenario, and thereby its explanatory potential regarding current norm erosion processes in advanced democracies (Gerring, Reference Gerring2004).

Case selection and cross‐case analysis

The population of interest are all conflictual interactions between norm violators and norm defenders in multiparty democracies that start with an act of norm violation. The population consists of units, that is, countries in which conflictual interactions occur over time. Each unit can be further subdivided into cases, or conflictual interactions, during particular time spans (Gerring, Reference Gerring2004). Comparing the two conflictual scenarios within the same unit over time has the advantage of ensuring that many factors that influence the conflict between violators and defenders remain constant, except the strategic behaviour of norm violators.

The unit to be analyzed in the first empirical step is the conflictual interactions between the far‐right Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) and the political establishment in Austria. This unit displays many characteristics that are typical of the conflicts between norm‐violating challengers and established elites in advanced democracies. First, Austria has strong democratic norms that have been in place for decades. Second, like many other advanced democracies, Austria gradually developed from an essentially two‐party system into a multiparty system, with formerly big parties having to accommodate and adjust to the ascent of new parties. Third, norm violators in Austria overwhelmingly originate from the far right, as is currently the case in almost all other advanced democracies. Finally, Austria has experienced widespread norm erosion in recent decades (see Wodak & Pelinka, Reference Wodak and Pelinka2002; Sully, Reference Sully1997). Austria allows us to illustrate and contrast the two conflictual scenarios due to the FPÖ’s political ‘normalization course’ in the early 1980s and its subsequent exploitation by Jörg Haider (1950–2008), the FPÖ party leader from 1986–1999 and a dominant national political figure until 2002. Haider engaged in norm violations to spur his ascent from an obscure regional politician to one of Austria's most influential political figures. Haider's provocations were usually very ambiguous, and he strategically leveraged the FPÖ’s previously acquired reputation as a more moderate party that had distanced itself from its neo‐fascist origins. By comparing the FPÖ’s conflicts over norm violations with the Austrian establishment before and during Haider's reign, we can assess how employing the strategy of ambiguity and democratic credentials affects the dynamics and outcome of the norm erosion process.

The second step compares the Haider‐FPÖ’s conflictual interactions with the Austrian establishment to conflicts over norm violations in contemporary Germany, which is comparable to Austria in many ways. Like Austria, Germany has gradually developed into a multi‐party system, has had democratic norms firmly in place since the postwar years, and is confronted with norm violators that are primarily from the far right. As in the case of the FPÖ under Haider, the Alternative for Germany (AfD), the prime norm violator in German politics, frequently attracts attention through ambiguous provocations and disposes of democratic credentials. After its foundation in 2013, many former Christian‐Democrats with democratically flawless political careers took leading roles in the AfD. Moreover, the AfD initially campaigned on an economic manifesto and positioned itself as an anti‐EU party – positions that made it difficult to portray the party as outright racist or extremist. As in Austria with the FPÖ, Germany has experienced unseen levels of norm erosion because of the ongoing actions of the AfD. Germany, however, provides a least‐likely setting for the second conflictual scenario due to the thorough confrontation of its National‐Socialist past. American‐led re‐education and denazification after WWII, the fixation of principles of militant democracy (‘Streitbare Demokratie’) in the Basic Law (Jaschke, Reference Jaschke1991), and conflicts with the ’68 generation, eventually institutionalized a strong political consensus against anti‐democratic and extremist tendencies in German political culture, especially at the national level. Unlike in Austria, where the common conviction of being ‘the Nazis’ first victim’ long inhibited such a confrontation (Knight, Reference Knight1992), widespread norm violations in national politics are a relatively recent phenomenon in Germany. Accordingly, finding evidence for the second scenario in the German setting, where the political establishment should be comparatively more successful in repressing anti‐democratic behaviour, increases the likelihood that our theoretical argument can more broadly account for norm erosion in advanced democracies.

As Lust and Waldner (Reference Lust and Waldner2015, p. 7) argue, identifying instances of norm erosion ‘is a tricky task. Backsliding occurs through a series of discrete changes in the rules and informal procedures [that] take place over time, separated by months or even years’. In order to tackle this difficulty, we define rough time spans of interest within the analyzed units (ca. 1955–ca. 1986 for Austria at t0 [pre Haider], ca. 1986–2002 for Austria at t1 [intra Haider], and ca. 2013–present for Germany at t1 [intra AfD])Footnote 2. For each time span, we draw together empirical observations from different episodes of conflict over norm violations. We identify and analyze conflictual episodes using public statements by norm violators and defenders as reported by the media. This approach is warranted given that conflicts over norm violations are inherently publi c conflicts that are duly covered by the media (Helmke & Levitsky, Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004). Because of their calculated, ‘borderline nature’, norm violations quickly receive an unambiguous label in the media. This makes it relatively easy to identify relevant articles and follow the ‘conflict trail’, that is, to reconstruct all public conflictual interactions and statements (A1–A3). We used the Factiva databaseFootnote 3 to identify relevant articles from outlets across the political spectrum in order to control for source bias. We drew on secondary literature to illuminate additional aspects of conflictual episodes and when newspaper articles were not available.

Measurement of key variables and within‐case analysis

A challenging aspect of empirically identifying democratic norms is that their existence largely rests on actors not violating them (Helmke & Levitsky, Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004). Put differently, norms are primarily held in place by non‐events and by sanctions in the case of events. Hence, when established actors frame an utterance or action as a norm violation, this can be taken as an indicator that the norm previously existed. However, this is an imperfect indicator because established actors may seek to inflate a minor transgression for tactical reasons. To tackle this challenge of identifying norms, we also draw on various historical arguments about why a particular norm had been in place before it had been violated and why an utterance or action can therefore be interpreted as a violation in a particular historical context.

We consider a norm violation to be ambiguous when it contains a ‘double message’, that is, when different audiences can interpret it in distinct ways. On the contrary, a violation is considered to be unambiguous when only one sensible interpretation can be made (for a similar approach, see Wodak, Reference Wodak2015).Footnote 4 Similarly, we assess the existence of democratic credentials by analyzing norm violators’ previous behaviour (Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2006). We look for both ‘positive’ acts (i.e., a trajectory of playing by the democratic rules) and ‘negative’ acts (i.e., the open, visible, often noisy rejection of a clearly undemocratic past). When violators visibly and repeatedly adopted unconventional policy positions and/or moderated their behaviour to signal their will to assume responsibility within the existing democratic order, we consider that they have democratic credentials during a conflictual episode.

Finally, we measure the outcome of the conflictual scenarios (norm damageFootnote 5 versus norm protection) by examining whether an act of norm violation remained an isolated incident or set a precedent for further norm violations. Given that electoral results are influenced by a host of factors, the electoral fate of political challengers after the norm violation is, at best, an indirect and incomplete indicator for norm damage. We thus try to more specifically assess whether a norm violator ‘got away’ with a norm violation and continued to exhibit an undemocratic style. Getting away with a norm violation includes resisting calls to voluntarily exit the political stage in response to sanctions (e.g., refusing to resign from one's seat in parliament), avoiding an unambiguous apology, and using the media attention created by the initial violation to incite further provocations and ambiguous remarks. We also examine whether political challengers committed additional violations after the initial provocation or whether they visibly and sustainably adopted more democratic behaviours. By comprehensively assessing these indicators, we can reliably determine whether a particular norm violation set a precedent and led to norm damage or remained an isolated incident.

To establish the effect of the strategy of ambiguity and democratic credentials on the outcome of the conflict, we primarily rely on cross‐case comparisons within and between units (i.e., countries). We also gather within‐case evidence of the strategy's effect by engaging in counterfactual reasoning, a process‐tracing technique that helps to isolate the causal sequence of conflictual interactions (Lyall, Reference Lyall, Bennett and Checkel2015). This means that we provide arguments for why a conflict should have played out differently in the absence/presence of the strategy of ambiguity and democratic credentials.

Further information on the data collection and all the conflictual episodes can be found in the Supporting Information. Direct quotes in the subsequent sections are also referenced in the Supporting Information.

Austria at t0: The FPÖ and the Austrian political establishment before Haider

From its foundation in 1956, the FPÖ was an openly far‐right party that lacked democratic credentials. The FPÖ of the 50s and 60s had many former Nazis in its ranks and its first two party leaders were the former NS‐undersecretary, Anton Reinthaller, (1956–1958) and the former SS‐Obersturmführer, Friedrich Peter (1958–1978). From the mid‐50s until the beginning of the 80s, Austria featured a ‘2,5 party system’, with two large parties (the conservative ÖVP and the social‐democratic SPÖ) dominating the political landscape and shunning the much smaller FPÖ (Luther, Reference Luther1992). However, due to various socio‐political and economic changes from the 70s onwards, the established parties increasingly struggled to gain absolute majorities (Decker, Reference Decker1997). This development created a realistic power opportunity for the FPÖ as the smaller party in a coalition government.

First under Friedrich Peter, and later under Norbert Steger (party leader from 1980–1986), the FPÖ adopted a more moderate stance, signalling to the public that it wanted to become a liberal‐conservative, pro‐democratic party. Both Peter and Steger excluded radical members from the FPÖ (democratic credentials). When in 1983 the FPÖ even entered into a governing coalition with the SPÖ, the more moderate course seemed to pay off. However, the FPÖ’s more moderate stance also came with diminished electoral results. The party's core supporters during that time still opposed the postwar Austrian Republic. Moreover, as the much smaller governing party, the FPÖ could not sway disgruntled voters through tangible policy achievements.

Our first conflictual scenario captures the conflicts between the FPÖ and the Austrian political establishment that emerged whenever the FPÖ’s nationalist base, frustrated by the party's position in the institutional arrangement, gained the upper hand and forced the party off its more moderate course. The norm violations committed by prominent FPÖ politicians during these periods predominantly went against two prominent norms that characterized the institutional status quo: the political culture of tolerance and respect between the main political players (Decker, Reference Decker1997) and the acknowledgement and condemnation of Austria's National‐Socialist past, which the political establishment converged on (partly due to international pressure) from the 1970s onwards (Knight, Reference Knight1992). Crucially, however, when the FPÖ chose to rebel against the political status quo by violating norms (A1), the established parties successfully ostracized it (A2 = effective). Three episodes illustrate this dynamic.

The ‘Papp ins Hirn’ controversy (1979). Alexander Götz, a former Nazi and the FPÖ’s party leader from 1978–1979, was an antidote to Peter and (later) Steger who came to power because opposition from the party base towards Peter's normalization course had become too strong (lack of democratic credentials). Götz wanted to lead the FPÖ back onto a strict ‘opposition course’ (Decker, Reference Decker1997, p. 651) and engaged in norm violations for this purpose. He made his most well‐known provocation in 1979, when he attacked the SPÖ chancellor, Bruno Kreisky, a very popular centrist politician, by stating that he had ‘glue in the brain’ (‘Papp ins Hirn’) (A1). While a trifle from today's standpoint, Götz's remark was a blatant and unheard‐of violation of the norm of mutual political respect, which characterized the relationship between the ÖVP and the SPÖ, and on which also the FPÖ had previously converged under Peter (lack of ambiguity). The SPÖ strongly sanctioned Götz for his norm violation (A2). It quickly adapted its national electoral campaign to attack Götz in person (‘Götz & Taus ‐ Nein Danke’) and to portray him as ‘unfit for democracy’ due to his Nazi‐past. Kreisky himself vowed to ostracize him, stating that as long as Götz stood by this statement, he would no longer talk to him. The events that followed suggest that established actors’ sanctioning brought the FPÖ off its (short‐lived) norm‐violating course (A3 = ineffective). For one, Götz had little opportunity to refute the (factually correct) allegations regarding his past, and he stepped down as party leader when Kreisky's SPÖ reached an absolute majority. Moreover, and even more telling, his successor, the much more moderate Norbert Steger, later publicly remarked that he and his supporters had realized that Götz's norm violation had significantly damaged the FPÖ’s relationship with the SPÖ: ‘We boys had learned the lesson from these events that we must not be pushed into such a corner in the future’.Footnote 6 This statement amounts to a clear renunciation of his predecessor's norm‐violating course and shows that the establishment's sanctions could stop violators in a situation where the violation was unambiguous and the violators lacked democratic credentials (lower left box in Figure 1, above).

The ‘Handshake’ controversy (1985). Another controversy, where the first conflictual scenario plays out, occurred in 1985. Two years earlier, the FPÖ under Steger had entered into a coalition government with the SPÖ, securing three minister posts, among them the defence ministry. In 1985, the FPÖ’s defence minister, Friedhelm Frischenschlager, officially received the Austrian former SS‐commander and outspoken Nazi, Walter Reder, with a handshake after his return from an Italian prison. Frischenschlager's official reception of Reder and his remarks, ‘Hello Mr. Reder, welcome home! I am happy for you’, constituted a very blatant norm violation in 1980s Austria, which had begun to more thoroughly confront its National‐Socialist past (A1). Established political actors, including, after some hesitation, those from the SPÖ (the FPÖ’s coalition partner), strongly condemned Frischenschlager's gesture and statement, taking it as evidence that the FPÖ was not ‘fit for government’ and called for its political isolation. Several politicians also called for Frischenschlager's resignation (A2). Frischenschlager only weakly tried to relativize his actions. He argued that his gesture and words had been misunderstood but simultaneously remarked that he understood why they had been misunderstood. Frischenschlager thus did not contest the framing of his actions that was put forward by established actors and upon pressure, made clear and repeated apologies (A3 = ineffective). Hence, although the FPÖ clearly possessed democratic credentials because of Steger's preceding normalization course and its position as a governing party during this controversy, Frischenschlager's unambiguous actions left him with little room to reframe them (lower right box in Figure 1, above). Accordingly, instead of relativizing or downplaying them, he emphasized the sincerity of his apology.

The controversy about Haider becoming party leader in 1986. A third controversy occurred shortly after the second when Jörg Haider, whose reputation as a hardliner at the state level preceded him, forced Steger to step down and vocally criticized Frischenschlager for retracting during the ‘Handshake’ affair. Haider's election as party leader at the FPÖ’s convention in 1986 was widely considered as an intolerable provocation by the FPÖ, not so much because of Haider's own statements but because the party's nationalist base supported Haider with unambiguous ‘Sieg Heil’ calls at the party convention (A1). The SPÖ immediately terminated the governing coalition with the FPÖ, sending the latter into the opposition. Other parties also announced that they would not enter into coalitions with the FPÖ as long as the party sheltered Nazis (A2). Even though Haider had already employed the strategy of complaining about democratic exclusion by the ‘old parties’, which he would later employ to considerable effect (A3), the unambiguous circumstances of his election allowed the established parties to justify their severe response (lower right box in Figure 1, above).

The three episodes exhibit a conflictual pattern that substantially matches our first conflictual scenario. Unambiguous norm violations by the FPÖ triggered strong sanctions by the political establishment that portrayed the FPÖ as unfit for democracy. At least until 1986 (when with Haider's ascent a new conflictual pattern can be observed), these sanctions prompted the FPÖ to visibly veer off its norm‐violating course. Through their sanctions, the established actors increased the FPÖ’s costs of engaging in norm violations and, at least in the first two controversies, elicited clear commitments by leading FPÖ politicians to play by democratic rules again (outcome: norm protection). During the first episode, the established actors used the unequivocal Nazi‐past of many prominent FPÖ members (i.e., the lack of democratic credentials) to mark the party as undemocratic and to thereby justify their strong sanctions. However, even after the party had embarked on a normalization course and distanced itself from its Nazi past, unambiguous provocations still allowed the political establishment to frame the FPÖ’s actions as undemocratic. This became significantly more difficult when Haider began to combine ambiguous provocations with the leveraging of democratic credentials.

Austria at t1: Haider's FPÖ and the Austrian political establishment

After the FPÖ found itself in the opposition in 1986, Haider, as the newly elected party leader, embarked on an anti‐establishment course characterized by frequent norm violations. Two controversies illustrate how Haider's new norm‐violating style, characterized by ambiguous provocations (A1) and the frequent emphasis of his party's democratic credentials acquired under the more moderate leadership of his predecessor (A3), made it exceedingly difficult for established parties to ostracize him (A2 = ineffective) (upper right box in Figure 1, above).

The ‘Ulrichsberg’ controversy (1995). Haider's public statements and the FPÖ’s election campaigns were often xenophobic, racist and they insulted its political opponents. Especially flagrant was Haider's ‘notoriety for ambiguous remarks on National Socialism’ (Sully, Reference Sully1997, p. 4). For example, in 1995, Haider spoke at the ‘Ulrichsberg’ meeting, a well‐known gathering of Nazis and SS‐veterans. He addressed the audience as ‘my dear friends’ and deprecated Austria's remembrance culture (‘a people that does not honor its ancestors is doomed to perdition’). Haider's remarks constituted an ambiguous provocation (A1) because it was not clear whom he was addressing and his remarks were more conservative truisms than openly fascist statements. Unlike in the case of the ‘Sieg Heil’ calls in the previous episode, it was thus possible to interpret this provocation in different ways. Nevertheless, established parties strongly sanctioned Haider. They expressed their indignation, called Haider a neofascist ‘beyond the realm of democracy’, and urged him to resign. Some politicians even employed formal sanctions by suing Haider (A2). Instead of apologizing for his actions, Haider confidently refuted the established parties’ accusations. He framed the established parties’ attacks as a tactical and unfair attempt to damage the FPÖ and ‘hunt’ him down; as a ‘cheap trick’ that had created ‘artificial uproar’ and as a deliberate misinterpretation of his statements. Haider launched a counterattack on established actors, accusing them of ‘insulting our parents and grandparents who simply love their home (‘Heimat’)’ (A3). Haider also reminded the established parties of their prior dealings with the FPÖ (democratic credentials) during a time when its party leaders were still former Nazis, thus pointing to the inconsistency in the established parties’ stance towards the FPÖ. Making this connection would have been impossible had the established parties not previously treated the FPÖ as a democratic partner.

The ‘Ariel’ controversy (2001). Established parties’ strong sanctions did not prevent Haider from committing further norm violations in subsequent years. In 2001, for example, he attacked the well‐known Austrian Jew, Ariel Muzicant, quipping that he would never have thought that someone called ‘Ariel’ could be such a dirty businessman (‘Ariel’ is both a Hebrew name and the name of a well‐known detergent) (A1). The opposition parties, the SPÖ and the Greens, quickly accused Haider of anti‐Semitism. Moreover, they appealed to the FPÖ’s coalition partner, the ÖVP, to position itself against Haider and criticized it for not reacting strongly and quickly enough.Footnote 7 After a couple of days, the ÖVP also unequivocally positioned itself against Haider (A2). The latter kept silent for several days but then refuted the anti‐Semitic allegations and “clarified” his statement as a form of criticism directed solely at Muzicant's business activities. In line with his reactions to the ‘Ulrichsberg’ controversy, he accused the established parties of being hypocritical, of treating the FPÖ unfairly and of overreacting in response to a ‘mere joke’. If anything, his statement was ‘unlucky’, and had, in any case, been overinflated by the ‘exclusive language police for the FPÖ’. Party colleagues concurred with Haider and portrayed him as the victim of the controversy (A3). Only much later in court did Haider apologize to Muzicant, who had sued him. During the controversy, Haider explicitly leveraged the FPÖ’s position in government and the ÖVP's initial more biding stance by claiming that if his statements had really been anti‐Semitic, ÖVP chancellor Wolfgang Schüssel ‘would have surely condemned them’ – a comment Haider could only make because of his party's democratic credentials as a governing party.

The two controversies reveal a pattern that significantly matches our second conflictual scenario. Haider's norm violations were followed by strong verbal sanctions, which apparently did not ostracize or discourage him from engaging in further norm violations (outcome: norm damage). Instead, he frequently used these sanctions to ‘clarify’ his provocative positions and launch a counterattack on the established parties. An important precondition for this different outcome of the conflictual process is that Haider's provocations were not explicit. Instead, they were rather ambiguous, which provided him with the opportunity to propose a different interpretation than the one presented by norm defenders, and to thus portray himself as the ‘real’ victim of the controversies that he had started. His party's recently acquired democratic credentials made these reframing attempts more credible. The FPÖ’s reformed image as a party that had largely cut off its roots from the National‐Socialist milieu provided Haider with a crucial opportunity to demand political respect from the political establishment; a demand that would have been utterly unrealistic had Haider's party not previously acquired a more moderate image. The next section seeks to validate these insights in the German context.

Germany at t1: The AfD and the German political establishment

The AfD's entrance into the German federal parliament in 2017, barely 4 years after its foundation in 2013, marked the first time in postwar history that a far‐right party could establish itself in the German party landscape. Initially an anti‐EU party that largely consisted of elderly male professors and disgruntled former CDU members, the AfD quickly acquired democratic credentials by criticizing the German government's policy decisions during the Eurozone crisis. Although this stance was controversial, it was firmly within the spectrum of democratically acceptable political positions and in line with other far‐right parties’ attempts to establish a ‘reputational shield’ by accumulating a legacy of democratically uncontroversial policy positions (Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2006). Despite its electoral successes, and similar to the case of the FPÖ in Austria from the 1950s until the 2000s, the AfD is currently isolated in the German multiparty system. All established parties share and support Germany's self‐perception as a worldly, open and welcoming country that has thoroughly confronted its National‐Socialist past and that honours its international commitments, particularly its leading role in the European Union (EU). Moreover, Germany exhibits a political culture of tolerance and respect where there is no space for extremism. The Christian Democrats’ (CDU/CSU) decade‐long strategy and commitment to not accepting a party ‘to its right’ is the clearest manifestation of this political norm. The conflicts that occurred between the AfD and established political parties when it violated this consensus resemble those in Austria under Haider in important respects, as the following two controversies demonstrate:

The ‘Mahnmal’ controversy (2017). In 2017, Björn Höcke, a well‐known AfD politician, provoked the political establishment by relativizing Germany's responsibility for the Holocaust and mocking the country's remembrance culture and ‘official historiography’. His provocation was ambiguous as it consisted in a clever word play that called the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin as a ‘memorial of shame’ (A1). All established parties strongly sanctioned Höcke for his norm violation and argued that he had ‘crossed a line’ with his comment. They pressured the AfD to expel Höcke, a decision which would determine whether the AfD ‘remained within the democratic spectrum’. Some established politicians went further by suing Höcke and by calling for the AfD to be observed by the Verfassungsschutz (the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution) (A2). Höcke and the AfD were largely unimpressed by the political outcry. Höcke clarified what he ‘really meant’ with his statement, namely, that he had not implied that the memorial was a shame for Germany, but that it simply reminded everybody of Germany's shameful past regarding the Holocaust. He announced legal steps against the ‘malignant interpretations’ of his words and claimed that he was ‘astounded’ by the reaction of the media and ‘concerned’ that the debate surrounding his statement had ‘left the objective realm’. Höcke only finally publicly regretted his ‘choice of words’ after a month. Leading AfD politicians also defended Höcke and called his statement ‘inept but nothing more’. They could not understand the ‘public uproar’ and argued that the media and their political opponents had pulled Höcke's statement out of context (A3). During the controversy, AfD politicians also claimed that the AfD needed to refocus its attention on Germany's asylum policy or its role in the EU. They framed established actors’ ‘obsession’ with Höcke's statement as a distraction from the AfD's substantive work and emphasized the party's more uncontroversial policy positions, thus clearly drawing on the AfD's democratic credentials.

The ‘Bundestagsvize’ controversy (2017). In the same year, the AfD politician, Albrecht Glaser, triggered a controversy exhibiting a similar pattern. Glaser called Islam a political ideology rather than a religion and claimed that, for ‘those who do not respect basic law’ (the German Grundgesetz), the latter should be revoked (A1). Given the fact that basic law applies to everyone and cannot be ‘revoked’ under any conditions, Glaser, a jurist, clearly made an ambiguous provocation meant to entrap established actors, given that it could be interpreted as both a juristic statement and a racist comment. Established actors, in fact, made the latter interpretation and condemned Glaser's statements as undemocratic and sanctioned the AfD by refusing to grant Glaser the post of AfD parliamentary vice speakerFootnote 8 (A2). Glaser reframed his statements by claiming that they had not been directed at ‘the individual human being’ but at ‘Islam’ and called himself an ‘exemplary democrat’ who ‘suffered’ from the other parties’ exclusion. He described his non‐election as a ‘political game whose only goal is to keep out the AfD’. Other AfD politicians described the accusations as absurd and claimed that ‘they were just looking for an excuse to deny us this post’ (A3). Glaser, who was a long‐time Christian Democrat before joining the AfD, used his democratic credentials to portray the established actors’ reaction as excessive and as a norm violation in itself. His party colleagues supported this line of argumentation by arguing that Glaser was ‘an irreproachable man with great merits’; a claim that could only be made because of Glaser's long history as an uncontroversial Christian Democrat.

The two conflictual episodes have important similarities, and they resemble those in Austria during the Haider years. The AfD used ambiguous provocations and leveraged its reputation as a democratically elected party committed to substantive policy work and the uncontroversial conservative origins of many of its members to portray established actors’ sanctions as excessive and as norm violations in their own right (upper right box in Figure 1, above). AfD politicians’ remarks after an initial norm violation and the overall sequence of events, suggest that established actors’ verbal sanctions did not discourage AfD politicians from engaging in further norm violations. The AfD's indifference only altered when the established parties threatened it with more formal sanctions, most notably an observation by the Verfassungsschutz.Footnote 9 This threat was apparently not without consequences as some AfD politicians subsequently criticized the respective norm violators for going too far. This suggests that conflicts over norm violations can take a different turn or may be stopped once established actors are able to follow through with the employment of formal sanctions.

Discussion

The analysis reveals that very similar conflictual processes led to norm erosion in the typical case of Austria (at t1) and in the least‐likely case of contemporary Germany. Norm defenders struggled to discourage norm violators from further engaging in norm violations when violators combined ambiguous provocations with the leveraging of democratic credentials. The replication of this finding in the German context is indicative of the external validity of the second conflictual scenario. This suggests that this finding also applies to other multiparty democracies where there is general agreement on democratic norms but also significant reservoirs of democratic disaffection (and hence goodwill towards norm violators). Three original insights can be derived from this agency‐centred analysis of norm erosion processes in advanced democracies. First, we show how norm violators can inflict damage on democratic norms from a position of institutional weakness, that is, before they eventually gain power and challenge democratic practices ‘from within’.

Second, the analysis suggests that in today's political environment, in which many norm‐violating challengers have accumulated a history of democratically acceptable actions and cut off their ties to extremist milieus, established actors’ verbal sanctions have become an increasingly ineffective identifier of anti‐democratic behaviour. As we have shown, norm violators that make ambiguous provocations and can leverage democratic credentials dispose of better opportunities for portraying strong sanctions as a democratically unfair form of ‘excessive retaliation’, thus giving (potential) supporters a reason to excuse or even appreciate norm‐eroding behaviour. This finding complements research that considers voters to be the decisive factor in the struggle against democratic backsliding (Przeworski, Reference Przeworski2019; Svolik, Reference Svolik2019). Our analysis suggests that it is not simply (exogenous) changes in voters’ opinions that make them less critical of norm‐eroding behaviour, but also that norm violators’ choice of strategy and established elites’ sanctioning practices facilitate certain interpretations of norm violations.

Third, and more broadly, our analysis also complements research that focuses on the structural conditions for democratic stability and backsliding (e.g., Weyland, Reference Weyland2020) by providing original insights into the conflictual interactions that connect structural conditions to a state of eroded norms. Research that links patterns of globalization to forms of populism (Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2018) or that explores the impact of party polarization on democratic norms (Mickey et al., Reference Mickey, Levitsky and Way2017) often employs a ‘tit‐for‐tat mutual escalation’ heuristic that quickly leads from individual norm violations to eroded norms (e.g., Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018, pp. 130−33; for criticism, see Fishkin & Pozen, Reference Fishkin and Pozen2018, p. 918). Our analysis suggests that this heuristic should be replaced with a more accurate description of the conflictual political process that connects norm violations to eroded norms. It is not wilful imitations but rather unsuccessful sanctioning attempts that pave the way for norm erosion.

Future research could help to address some of the limitations of our analysis. We are aware that ambiguous provocations and democratic credentials are two very fuzzy concepts as they are highly case‐specific and can be ‘created’ by norm violators through a wide variety of utterances and actions. While a comparative‐qualitative analysis drawing on in‐depth case knowledge, counterfactual reasoning, and controlled comparisons can handle this difficulty and isolate these conditions’ effects, additional research is needed before they can be employed in large‐N studies. One way could be to focus on voters to systematically assess which types of violations they are willing to let slide (i.e., consider to be ‘ambiguous’) and which prior actions cause them to see political outsiders as democratically acceptable actors.

Moreover, and related, additional research on the relative importance of both conditions is needed. Our theory and analysis suggest that it is the combination of ambiguous remarks with the leveraging of democratic credentials that ultimately leads to norm erosion. Accordingly, when one of these conditions is missing, it is easier for the establishment to protect democratic norms. However, within Austria at t0, we were only able to identify cases where both conditions were missing (i.e., blatant remarks in combination with lacking democratic credentials) and where ambiguity was missing (i.e., blatant remarks in combination with democratic credentials). On the contrary, we could not identify cases where violators without democratic credentials made ambiguous remarks. While this limitation does not weaken our finding that the second scenario (‘ambiguity’ in combination with ‘democratic credentials’) convincingly accounts for norm erosion in contemporary democracies, we cannot make definitive statements about the relative importance of both conditions.

A related complication is that while we measured ambiguity and democratic credentials dichotomously to contrast the importance of each condition's presence or absence, it is also possible to conceptualize them as continuous variables. Doing so would allow for a more explicit theorizing of the public's stance during conflicts over norm violations. For example, comparisons between the ‘magnitudes’ of a norm violation and the violator's democratic credentials may influence whether citizens cast their lot with the violator or with the defenders.

Finally, there are obviously factors beyond the employment of the strategy of ambiguity and democratic credentials that shape the conflictual interactions between norm violators and defenders in multiparty democracies. As the comparison between Austria (at t1) and contemporary Germany suggests, coalitional dynamics that determine the strategic importance of norm violators (Austria) and the ability of established actors to employ more formal sanctions (Germany) also influence the conflicts over norm violations. While not explored here, it could be potentially relevant to examine the radicalization processes within norm‐violating parties (which may gradually undermine democratic credentials) or the media's ‘fascination’ with norm violators’ provocations and subsequent relativizations (which influences how much attention norm violators get to reframe their initial violations). Considering these factors invites a more systematic look of long‐term equilibria in conflicts over norm violations. While our analysis suggests predictable conflict outcomes based on norm violators’ strategy choice, future research could factor in the learning effects of norm violators, norm defenders and the public (see, e.g., Heinze, Reference Heinze2022).

Conclusion

This article aims to contribute to our understanding of the erosion of democratic norms in advanced democracies by exploring the interactions between political challengers as norm violators and established actors as norm defenders in multiparty systems. We analyzed and compared conflicts over norm violations in Austria and Germany in order to highlight the process that connects an act of norm violation to a state of eroded norms. We found that when norm violators begin a conflict with an ambiguous provocation and can leverage democratic credentials that help them reframe this provocation, established actors’ verbal sanctions tend to be ineffective if not counterproductive. Verbal sanctions provide norm violators with an appropriate occasion to complain about ‘excessive retaliation’ and to present themselves as the actual victims of a political conflict they started. In this conflictual scenario, norm protection paradoxically facilitates norm erosion.

Besides adding an important explanatory piece to the discipline's cumulative research and theorizing on democratic backsliding, our article highlights the strategic dilemma that established actors face when they are called on to defend democratic norms. In socio‐political environments where many political actors develop incentives to present themselves as norm‐violating challengers or outsiders, norm‐defending actors are unlikely to put them in their place by condemning their actions at the first opportunity. Moreover, norm defenders bound by their own democratic commitments cannot swiftly employ more formal sanctions as these require fulfilling criteria that are usually not met by political challengers who only violate informal norms. A way out of this strategic dilemma could be by educating norm defenders and the public. Specifically, defenders could react more ‘symmetrically’ to norm violations: reacting to easy‐to‐see‐through provocations by employing moderate sanctions, or by completely ignoring them, and reacting to severe norm violations by employing strong verbal and formal sanctions. Norm defenders that save strong sanctions for severe norm violations preserve the public's attention associated with their use. This symmetrical reaction produces a climate in which norm defenders’ responses come across as more considerate and appropriate, as well as arguably, making it more difficult for violators to turn the tables on norm defenders.

Acknowledgements

Our thinking about conflicts over norm violations was initially inspired by the ‘rope‐a‐dope’ metaphor, which Muhammad Ali had used to describe his provocative strategy of attrition against George Foreman in the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’. However, since this metaphor would have equated today's norm violators with one of the greatest athletes of all time, it was out of the question to use it in the article. The authors want to thank James Dennison for seminal input, Deborah Fritzsche for excellent research assistance, and the anonymous reviewers and our colleagues at Harvard's Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies and Berkely's Institute of European Studies for their very helpful suggestions and comments.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary Online Appendix: Table A1: Conflictual episodes during Austria at t0

Table A2: Conflictual episodes during Austria at t1

Table A3: Conflictual episodes during Germany at t1