1. Introduction

The production, trade, and consumption of commodities and food products, and their movement around the planet, were essential to the development of global markets during the first global economy. Between the mid-nineteenth century and 1938, these products were the main part of world trade, representing between 55% and 65% of it (Federico and Tena, Reference Federico and Tena2019).

Within the agri-food trade, the importance of meat increased, especially when certain technical innovations facilitated its transport without the need to salt it or move live animals. From the beginning of the twentieth century until the 1929 crisis, its relative weight in this trade more than doubled, reaching 12% of world agri-food trade just before the crisis (Aparicio et al. 2009).

An international commodity supply chain of canned meat products emerged in the 1840s. From the 1880s, when it became possible to ship fresh meat globally, Argentina and Uruguay became integrated into the global market as international meat suppliers, although these countries were already important exporters of live animals and salted meat beforehand. A drastic change in the global beef trade occurred over the subsequent decades due to the adoption of new production and transportation technologies (Pinilla and Aparicio, Reference Pinilla and Aparicio2015). Chilling meat instead of freezing it further stimulated South American exports due to European and particularly British consumers’ preference for this type of meat (Marketing Board, 1932, 14).

Between 1909–1913 and 1924–1928, the global trade in meat doubled in volume. The expansion in trade volumes relocated the center of the meat trade activity, shifting it from Europe and North America to South America and Australasia (Jones, Reference Jones2005). Consequently, the Río de la Plata area of Argentina and Uruguay’s global meat export volume market share increased strongly from 1890 until the 1930s, rising by 25.1% points from an important 35.4% in 1890–1894 to an all-time high of 60.5% in 1926–1930 (Gebhardt, Reference Gebhardt2000, p. 62).

Argentina’s growth as a beef exporter was particularly explosive. Although the United States had dominated beef exports for many years, from 1908 onward its exports declined (Mcfall, Reference Mcfall1927), and Argentine exports began to soar around the same time (White, Reference White1945). By the end of World War I, the country had become the world’s leading meat exporter and South America had almost achieved a monopoly of world markets. However, it should be noted that the United Kingdom purchased about 90% of the total output, meaning that during this period, the sector had no alternative foreign market for high-grade meat.

Seeking to dominate this trade, British and American companies invested heavily in South America and established companies there, first in the Río de la Plata area of Argentina and Uruguay and later in other countries such as Brazil, Paraguay, and Venezuela, as well as in the Argentine and Chilean Patagonia. As Chandler (Reference Chandler1990) and other authors have explained (Gebhardt, Reference Gebhardt2000), to compete in such capital-intensive industries, large investments in plants and equipment were needed, especially if firms aimed to increase the scale and scope of their operations. However, it is important to stress that such growth was not achieved uniformly in all the productive regions of South America.

Although the literature on meat production in South America is extensive, it often fails to consider two aspects. On the one hand, it is frequently divided between works with a business-oriented focus that tends to overlook more quantitative variables (Crossley and Greenhill, Reference Crossley, Greenhill and Platt1977; Gravil, Reference Gravil1985; Yarrington, Reference Yarrington2003; Lluch, Reference Lluch2019),Footnote 1 and on the other hand, those with a more macroeconomic perspective (Rayes, Reference Rayes2015; Pinilla and Rayes, Reference Pinilla and Rayes2019; Llorca-Jaña et al., Reference Llorca-Jaña, RN, Morales-Campos and JN2020; Travieso, Reference Travieso2020; Delgado et al., Reference Delgado, Pinilla and Aparicio2022; Rey, Reference Rey2022; Vidal and Klein, Reference Vidal and Klein2023; among others). Furthermore, the second aspect that is often overlooked is having a broader perspective on South America.

In this article, we aim to fill a gap in the literature with two primary contributions. On the one hand, we provide a business perspective coupled with quantitative and macroeconomic data. In other words, we strive to substantiate the business history of beef production and trade in South America with macro-level data. By doing so, we endeavor to mitigate the bias that often leans toward Argentina and Uruguay in the literature. Therefore, this article adopts a comprehensive overview of the meat-producing regions of Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Paraguay, and Patagonia (both the Argentine and Chilean sides), as well as the failures experienced by Venezuela and the Colombian Caribbean. Although the attempt to construct a “new” global/transnational history draws on different approaches and areas of research (Clarence-Smith et al., Reference Clarence-Smith, Pomeranz and Vries2006; Saunier, Reference Saunier2013; Topik and Wells, Reference Topik and Wells1998; Clarence-Smith and Topik, Reference Clarence-Smith and Topik2003; Topik et al., Reference Topik, Marichal and Frank2006), one common denominator has been the explicit intention to break out of the nation-state or singular nation-state as the category of analysis or, as more recently proposed, to rediscover how history at the scales of the local, national, regional, and global has been entangled (Drayton and Motadel, Reference Drayton and Motadel2018). In this regard, this contribution takes into consideration a recent call for business historians to truly engage in the history of globalization since “concepts and methodologies from transnational history can be of use to business historians” (Boon, Reference Boon, Chandler and Mazlish2005). This approach, which here takes the South American meatpacking industry as a case study, has also been influenced by the debates around the role of multinationals as vectors of globalization and agents of global change (Wilkins, Reference Wilkins, Chandler and Mazlish2005, Reference Wilkins2010).

One purpose of this article is to reveal the interconnectedness of the export profiles of each meat-producing region, particularly by examining the activities of large foreign firms operating in this industry up to the Great Depression and how these activities impacted prices and exports. Although the article confirms that the South American meat industry was most active in the area around Río de la Plata (Argentina and Uruguay), particularly near the city of Buenos Aires, the port at La Plata, and along the banks of the Paraná, Campana, and Zárate rivers, it also demonstrates that the industry’s profile varied greatly from one productive area to the next. Likewise, it proposes that although there are notable differences within the region certain levels of complementarity (and cross-subsidizes) can be observed in international firms’ operations, helping us understand why the operations of multinational companies were clearly interrelated in such a way as to dominate the global meat markets.

Another aim of the article is to analyze the main changes in the ownership structure and profile of the beef industry in South America. This sector has traditionally been studied as a uniform whole (that is, “the packers”). The intention is to demonstrate the degree to which the beef industry structure was transformed over time, not just because of the increasing market share controlled by US firms from the 1910s onward, but also due to the role of other local and British investors and the strong impact of mergers, acquisitions, and failures. Indeed, the article proposes that although market concentration and further consolidation were an identifying feature of the industry—explained by the need to exploit economies of scale and scope, in line with Chandler (Reference Chandler1990), in South America, there was an almost total replacement of the business players involved in it. The meat industry, therefore, offers an illuminating example of changes over time, as well as connections and comparisons across different productive areas.Footnote 2 Following this introduction, the second section examines the early development of the meatpacking industry in South America, characterized by the dominance of British and local capital (1860–1906). The third section examines the entry and expansion of US firms. The fourth section explores the “meat wars” and the rise of international market agreements in the Río de la Plata region. The fifth section focuses on World War I, highlighting geographic expansion and diversification. The sixth section discusses postwar consolidation and the growing influence of major British and US firms. The article concludes with a summary of its key points.

2. Early developments: dominance of the industry by British and local capital (1860–1906)

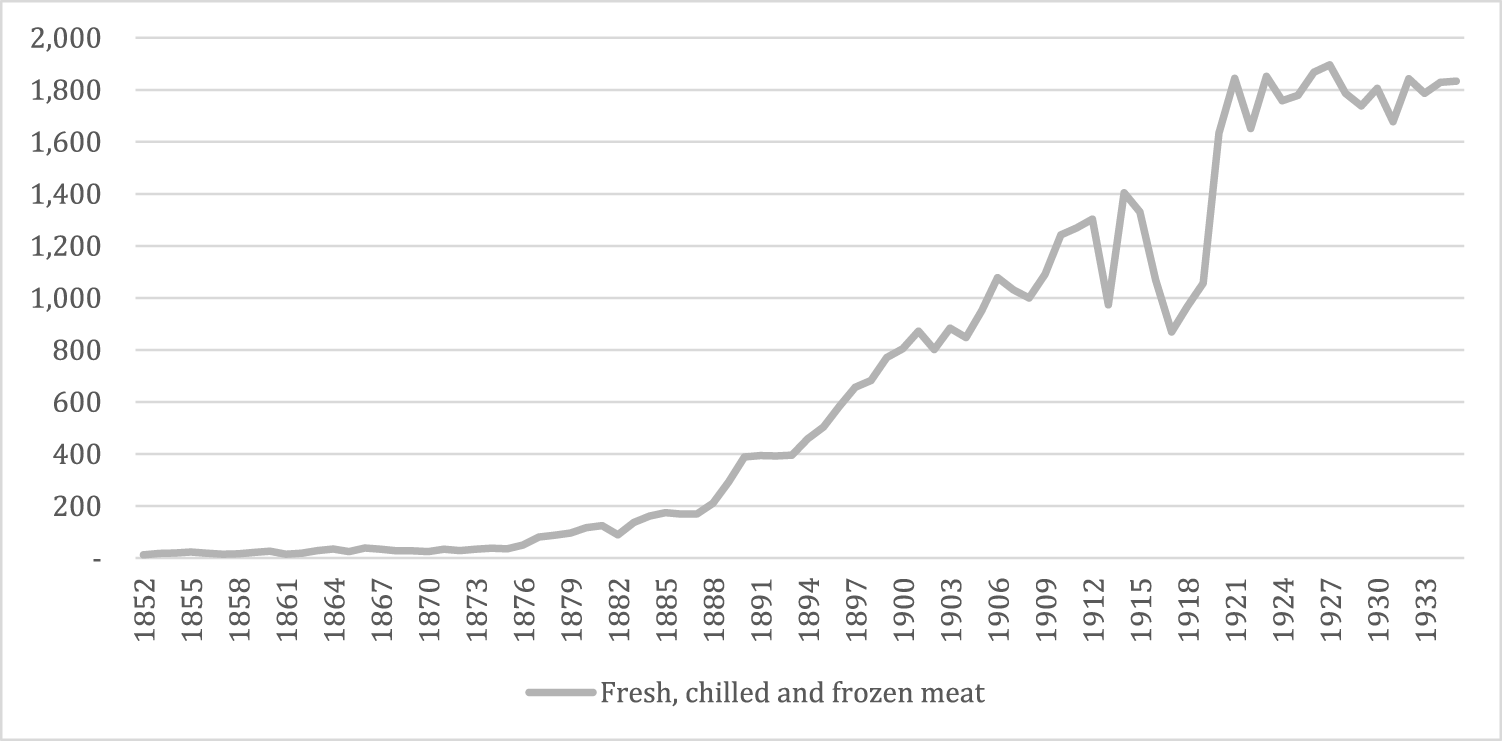

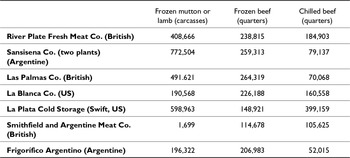

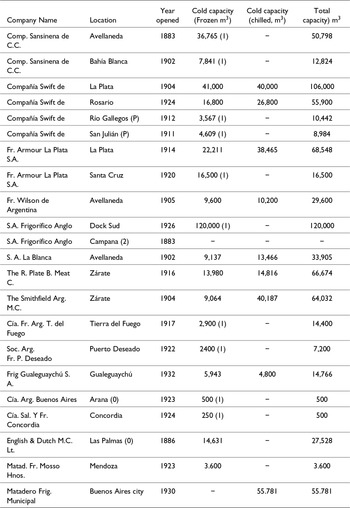

South American meat began to make its entry into the British market during the sixties, but from 1860 to 1880, its annual exports averaged less than one-half of one per cent of the total dead meat imported to the United Kingdom (Hanson, Reference Hanson1938). The increases in income in the England due to the Industrial Revolution led to the rise in the demand for meat that the national supply could not meet (Delgado et al., Reference Delgado, Pinilla and Aparicio2022). However, until the development of the frozen meat trade, the River PlateFootnote 3 was not an important source of supply. Experiments with refrigeration began in the 1860s, but it was not before the 1880s that the technology had stabilized enough to allow experiments with the long-distance exportation of frozen meat from New Zealand, Australia, and Argentina to Europe (Perren, Reference Perren2008; Henry, Reference Henry2017; May, Reference May and Dare1999). This is clearly evident from Figure 1. The import of fresh, chilled, and frozen meat into the United Kingdom, the primary global market for meat, did not take off until technology enabled it. During this early period, the United States dominated the British market, accounting for 93% of its fresh beef between 1875 and 1889.

Figure 1. Meat imports into the United Kingdom (thousands of hundredweight).

In South America, the early years of the beef industry were then a time of innovation and experimentation. Charles Tellier is known as the scientist and engineer who enabled the first meat cargo to be shipped through the tropics under refrigeration in 1877. He invented an ammonia-absorption refrigeration machine (patented in 1859) and, in 1867, produced an ammonia-compression refrigerating plant (Jones, Reference Jones1929). His first meat-shipping experiment, according to Bergés (Reference Bergés1915), was supported financially by Mr. Francisco Lecocq of Montevideo, Uruguay. Tellier patented his process across Europe and in Victoria, Australia, between 1874 and 1878 (Critchell and Raymond, Reference Critchell and Raymond1912).

However, the first modern meatpacking plant in South America was built in 1882 in Argentina with British capital, when George G. Drabble founded the River Plate Fresh Meat Co. (see Table A1 in the Appendix, which details the evolution of meatpacking plants in South America). The company began to export mutton and lamb the following year. In 1884, it started to freeze beef, and this trade soon exceeded that of mutton and lamb. The company intended to expand quickly into Uruguay and set up a plant at Colonia, but the venture did not pay off, and the company dismantled the establishment in 1888.

Two more plants were opened at the same time in the Argentine pampas. Eugenio Terrason constructed a plant at San Nicolás on the Paraná River, which dispatched its first mutton shipment in 1883. The same year, a firm called Sansinena de Carnes Congeladas was formed by Argentine capitalists, and its first shipments to Britain were made to James Nelson and Sons in 1887. Sansinena soon established an office in Liverpool and another in London in 1888, intending to market its own products. The Sansinena Distributing Syndicate Ltd. soon owned warehouses and stores and coordinated sales offices in London, Dublin, Glasgow, Cardiff, Liverpool, Birmingham, Manchester, Newcastle, Bristol, Leeds, Hull, Sheffield, Leicester, Burton, Wolverhampton, and Derby.Footnote 4

Las Palmas Produce Co. (a branch of the British firm James Nelson and Co.) entered the business in 1892. The company was registered in Britain to amalgamate Nelson’s (new) River Plate Meat Co. and James Nelson and Sons. It was registered in Argentina in 1893 (Jones, Reference Jones1929).Footnote 5 Some sources refer to the establishment of another meatpacking plant in 1884: La Congeladora Argentina, founded by the Argentine Rural Society to export frozen meat. The capital was $1,000,000 in Argentine paper pesos, and the company made its first shipment of cattle and sheep in 1885. However, the society shut down operations over the following years (Critchell and Raymond, Reference Critchell and Raymond1912).

This first stage, spanning almost two decades of the nineteenth century, was therefore one of experimentation and promotion for the industry throughout the subcontinent. The end of this cycle (1902–1903) in the Río de La Plata was considered a year of great prosperity for the meat export industry. It coincided with the strengthening of leadership in only three meatpacking firms, which saw sharp rises in production (and export) volumes. This process was linked to several global factors: a productive crisis in Australia; meatpacking strikes in Chicago; and, especially, the Anglo-Boer War, which triggered cattle exports to South Africa (Hanson, Reference Hanson1938, pp. 122–143; Liceaga, Reference Liceaga1952).

Regarding meat production and export, in addition to the growing production and export of mutton and frozen beef, beef extract was also produced. Still, this industry sector will not be analyzed in this article. Likewise, from its very beginning, the industry made the most of the by-products and exploited them commercially. Although this is another issue that cannot be explored here, it is one that went beyond matters of production volume (and value) in that it was crucial for companies to be able to maximize their competitive capacities (in terms of both production and distribution) and take advantage of economies of scale and scope.

Almost from its inception, the industry in the Río de La Plata was concentrated in the hands of a few companies. Within ten years, only three plants survived. Meat packers did not invest much in land and were neither breeders (criadores) nor fatteners (invernadores, who were generally estancieros, or ranchers) on their own account, although they did tend to form alliances with the largest estancieros.

An entirely new way of doing business emerged from the end of the nineteenth century that is described in this article as the “Río de la Plata way.” This operated as follows: in the Río de la Plata area, meatpacking plants bought their stock outright, thus minimizing competition in buying; they shipped using vessels which they chartered or owned; and they sold their meat abroad through their own representatives in Europe (Hanson, Reference Hanson1938, p. 57). This type of organization set this productive area apart from other meat-producing areas of the world (that is, the United States, Canada, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand).Footnote 6 As shown in Table 1, this type of organization already implied a clear export-oriented approach of the industry in the first decade of the twentieth century, especially in Argentina and, to a lesser extent, Uruguay, commanding over half of the global beef exports.

Table 1. Beef exports in different areas of the world, 1909–1913 (in thousands of quintals)

Source: Annuaire international de statistique agricole (1909–1939). One quintal = 100 kilograms.

Several changes took place in the structure of the Río de la Plata meat export business after 1900. In 1900, Britain suspended the importation of live animals for sanitary reasons, encouraging countries like Argentina to export beef. Second, between 1902 and 1905, several new firms entered the business in the Río de la Plata area: the Smithfield and Argentine Meat Co. (British capital), La Blanca and Frigorífico Argentino (local capital), and La Plata Cold Storage (British and South African capital), while Sansinena (a local company) opened a new plant (Cuatreros). Meanwhile, La Frigorífica Uruguaya was formed in Uruguay in 1903. The promoter was a Uruguayan financier and cattle-rancher, and its first shipment of frozen meat was dispatched to London in 1905 (Critchell and Raymond, Reference Critchell and Raymond1912).Footnote 7

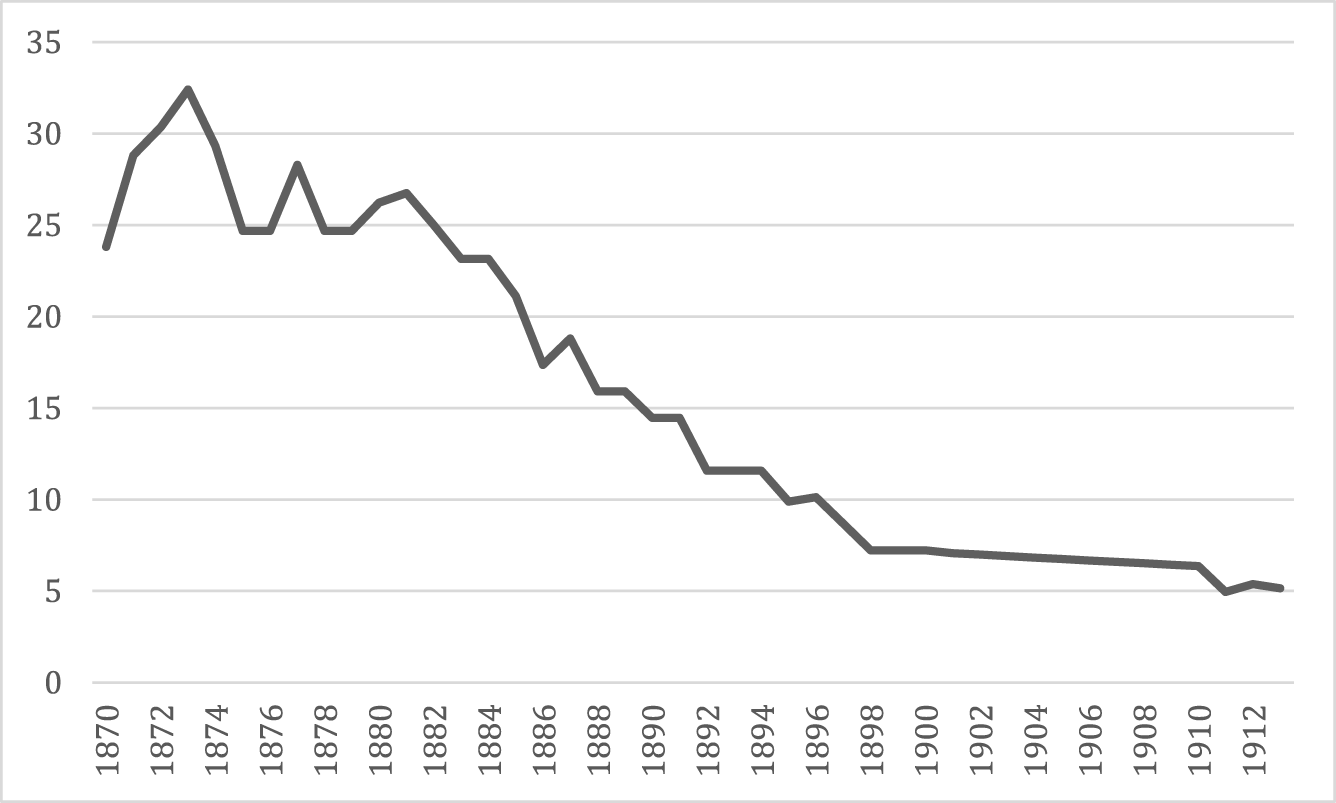

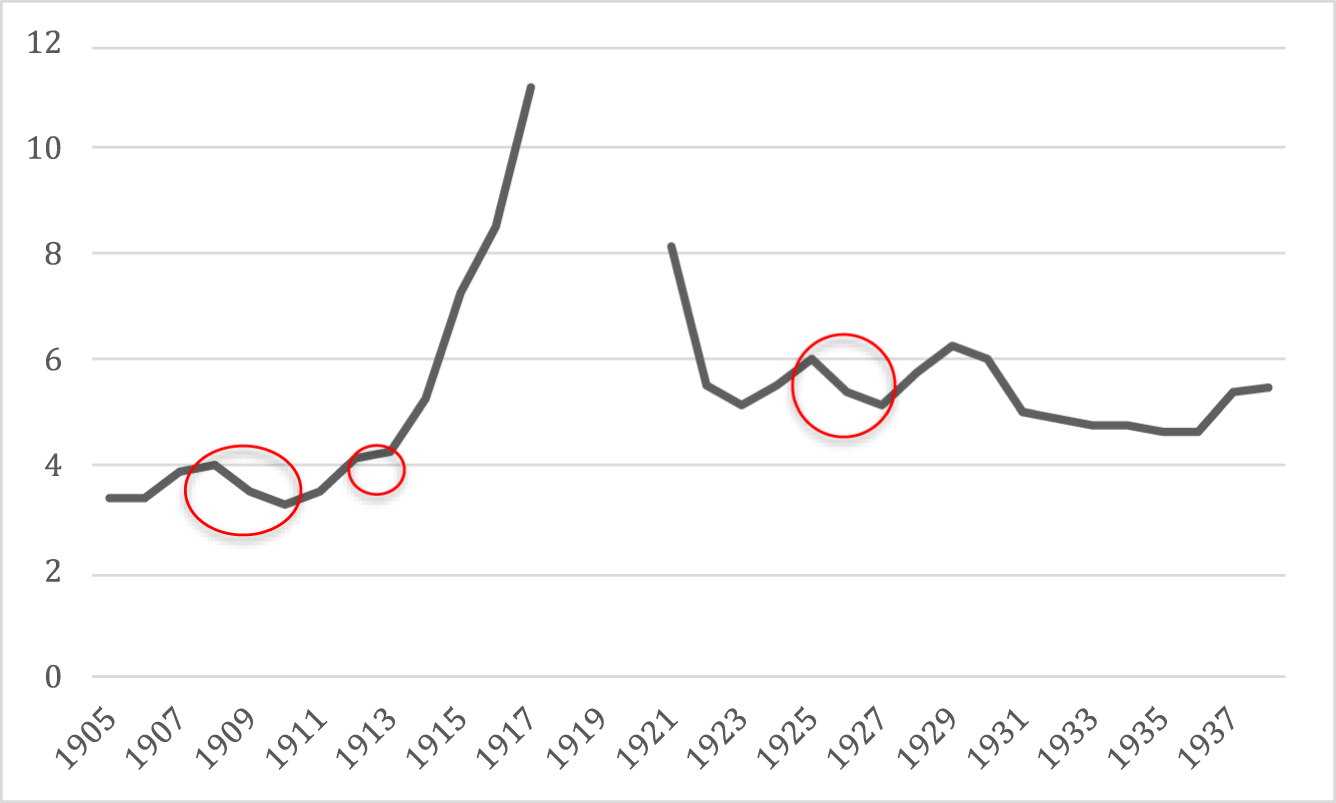

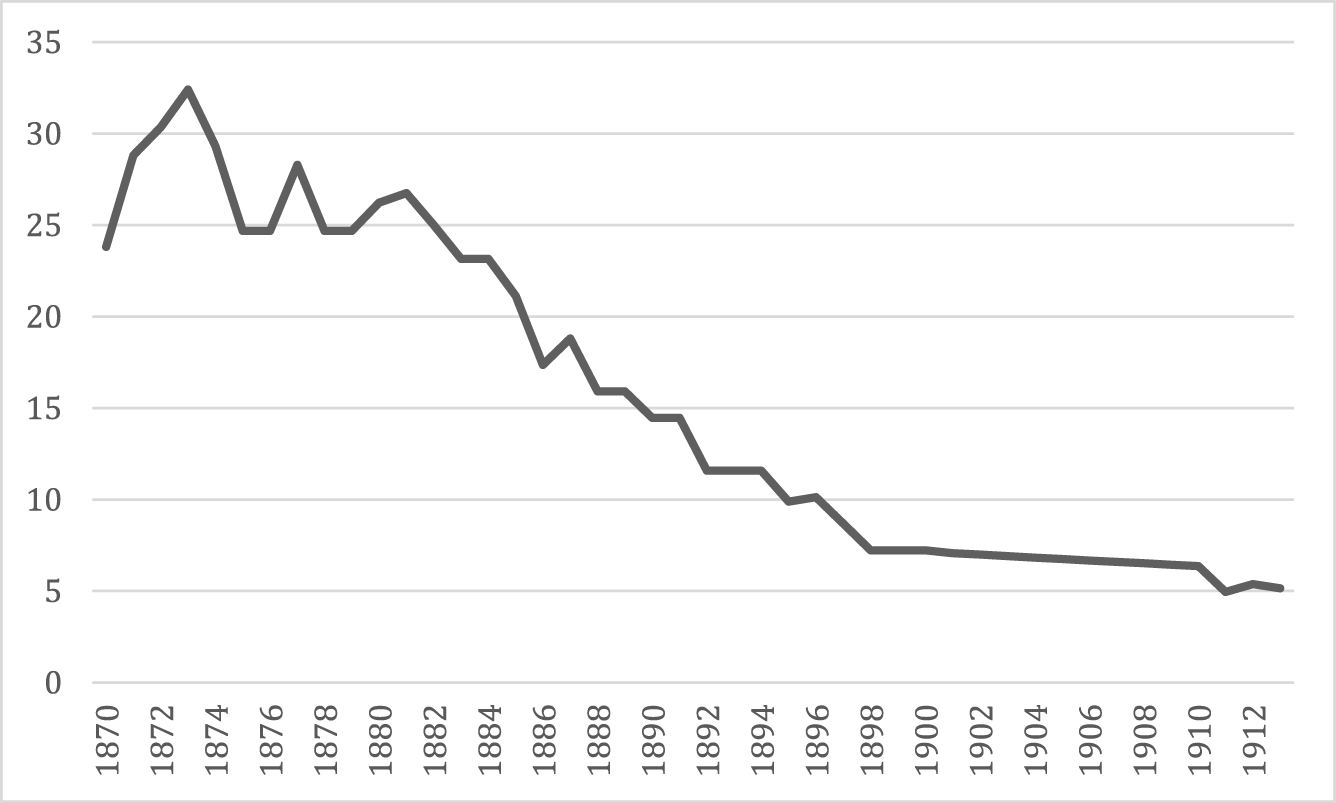

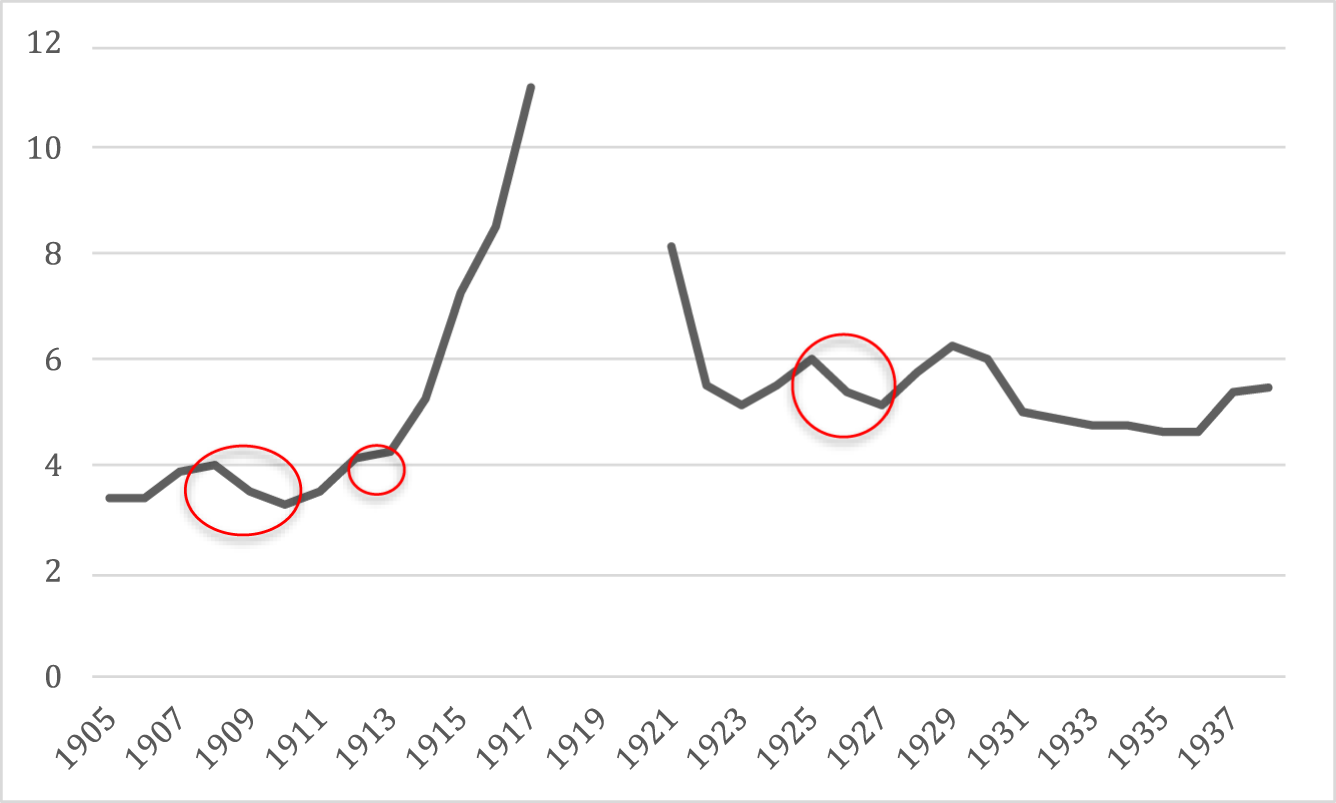

In the Argentine pampas, the arrival of new players promoted competition. The immediate reaction on the part of the managers of the oldest meatpacking plants was a desire to include the new enterprises in their “friendly chats” (Richelet, Reference Richelet1922). The main business of the packers was to buy cattle ready for the kill and sell the meat harvested from these animals, with the margin between these two prices being the key to profitability. In other words, the aim was to buy as low as possible and sell as high as possible. Another critical point in this business was transportation. Although somewhat later than in the cereal trade, transportation costs in the beef trade plummeted in the late nineteenth century with the widespread adoption of mechanical refrigeration (see Figure 2; Harley, Reference Harley2008). Transportation was directly associated with the availability of refrigerated hulls for shipments to Britain and led to a series of agreements to partition shipping facilities. According to Smith (Reference Smith1969), these agreements amounted to an apportionment of the British market, but the industry’s real power was exercised in the Río de la Plata area, where the packers enjoyed a buyer’s oligopoly.

Figure 2. Transatlantic freight rates of Argentina beef (£ per ton).

3. The rise of the American beef trust in the South American beef industry (1907–1920)

A new phase of development in the meatpacking industry began with the entry of US firms into South America. In 1907, Swift and Co., the largest US meatpacker, bought out the largest plant in Argentina, the meat lockers of La Plata Cold Storage Co. The second step in the US penetration was the purchase of the meatpacking plant, La Blanca, by the National Packing Company Co., later jointly controlled by Armour and Co. and Morris and Co. The locally owned Frigorífico Argentino closed down for several months in 1913, and when it resumed its operations in 1914, it did so under the name of Frigorífico Argentino Central, having been leased for three years to Sulzberger and Sons Co. This plant was later operated by Frigorífico Wilson de la Argentina, a subsidiary of Wilson and Co (Federal Trade Commission, 1919–1920).

The US companies entered South America by purchasing existing tidewater plants, which they improved and enlarged. These plants were served by a dense network of railroads radiating from the area (Crossley and Greenhill, Reference Crossley, Greenhill and Platt1977). Except for the Cudahy Packing Co., all the largest US meatpackers invested in South America, with Argentina as the main destination (Wilkins, Reference Wilkins1974).

Swift also moved quickly to the Argentine Patagonia, where it bought the New Patagonia Meat Preserving and Cold Storage Ltd. plant, founded in 1909 in Río Gallegos, for freezing mutton. It later built a new plant at San Julián, also in what was then Santa Cruz National Territory. These plants operated using different methods and functioned only between April and December (Federal Trade Commission, 1919–1920).

The US companies arrived in South America after the Bureau of Corporations’ investigation in 1904, the unsuccessful prosecution for violating antitrust laws in 1905–1906, and the 1906 scandals that followed the publication of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and the Neill-Reynolds Report (Hanson, Reference Hanson1938, p. 144). Indeed, at the macro level, the US meatpackers’ cartel’s manipulation resulted in a 23% decline in cattle prices and a 6% increase in beef prices between 1903 and 1917 (Huang, Reference Huang2023). But instead of certain overly simple images these circumstances often conjure up, the arrival of US meatpacking companies was part of a more global process that had begun in Argentina, and spread to Uruguay, Paraguay, and Brazil, reaching as far as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

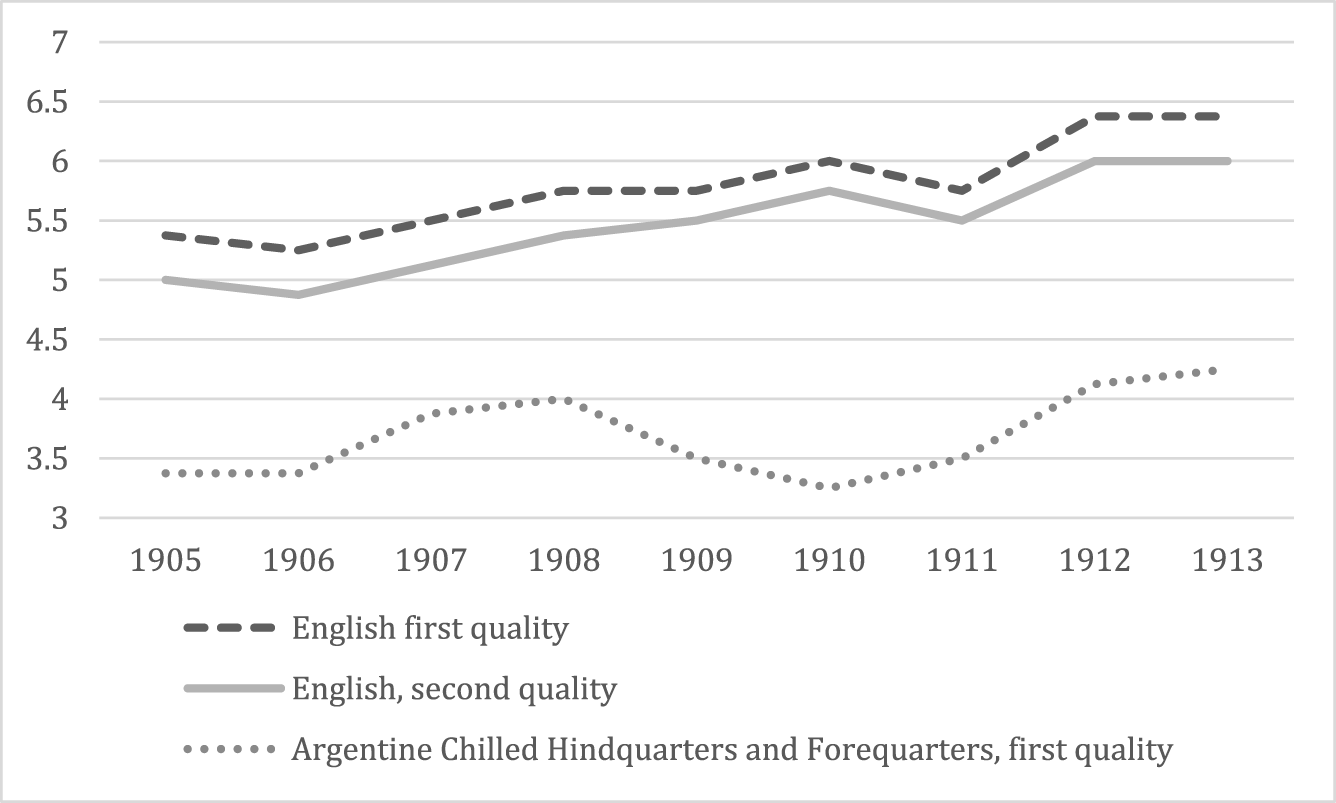

This international expansion enabled the US beef trust, under pressure from US antitrust investigations, to address two of its problems.Footnote 8 First, they could continue to dominate the chilled beef trade with the United Kingdom. This is significant because, at the time, the available domestic surplus for export was diminishing. Second, and more importantly, Argentine beef had become competitive on international markets because US production costs had risen (Wilkins, Reference Wilkins1974). By the beginning of the twentieth century, Argentina was able to produce good-quality beef cattle more cheaply than any other country due mainly to the country’s mild climate, the extensive farming system, low labor costs, and low taxes (White, Reference White1945). As shown in Figure 3, the wholesale price of first-quality Argentine beef in the London market was significantly lower than both the first and second-quality English beef. While part of this difference may be attributed to a higher preference for English beef among British consumers, it should be noted that the price of Argentine beef includes transportation and other trade costs.

Figure 3. Wholesale prices of Argentine and English beef in the London Market (pennies per pound).

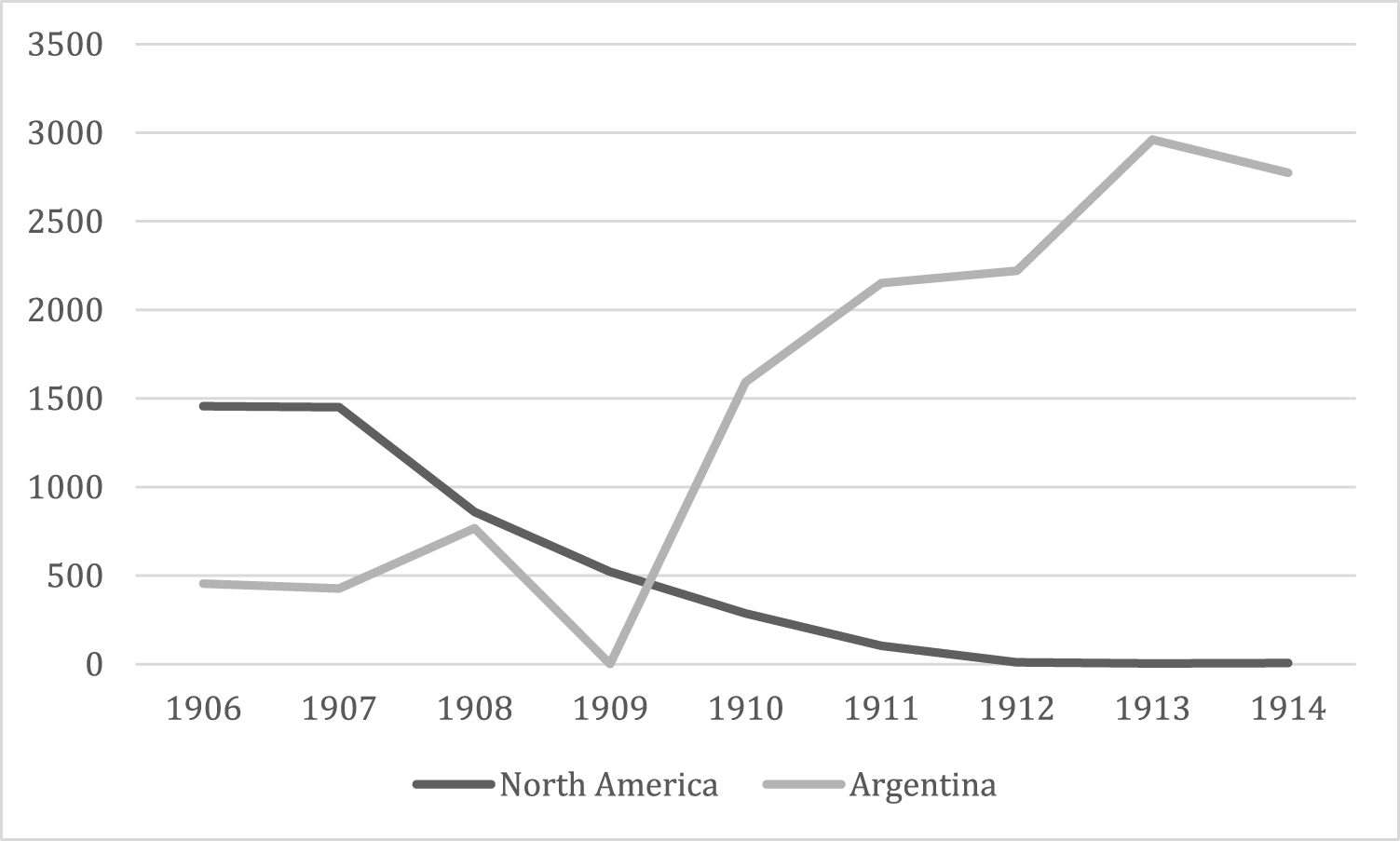

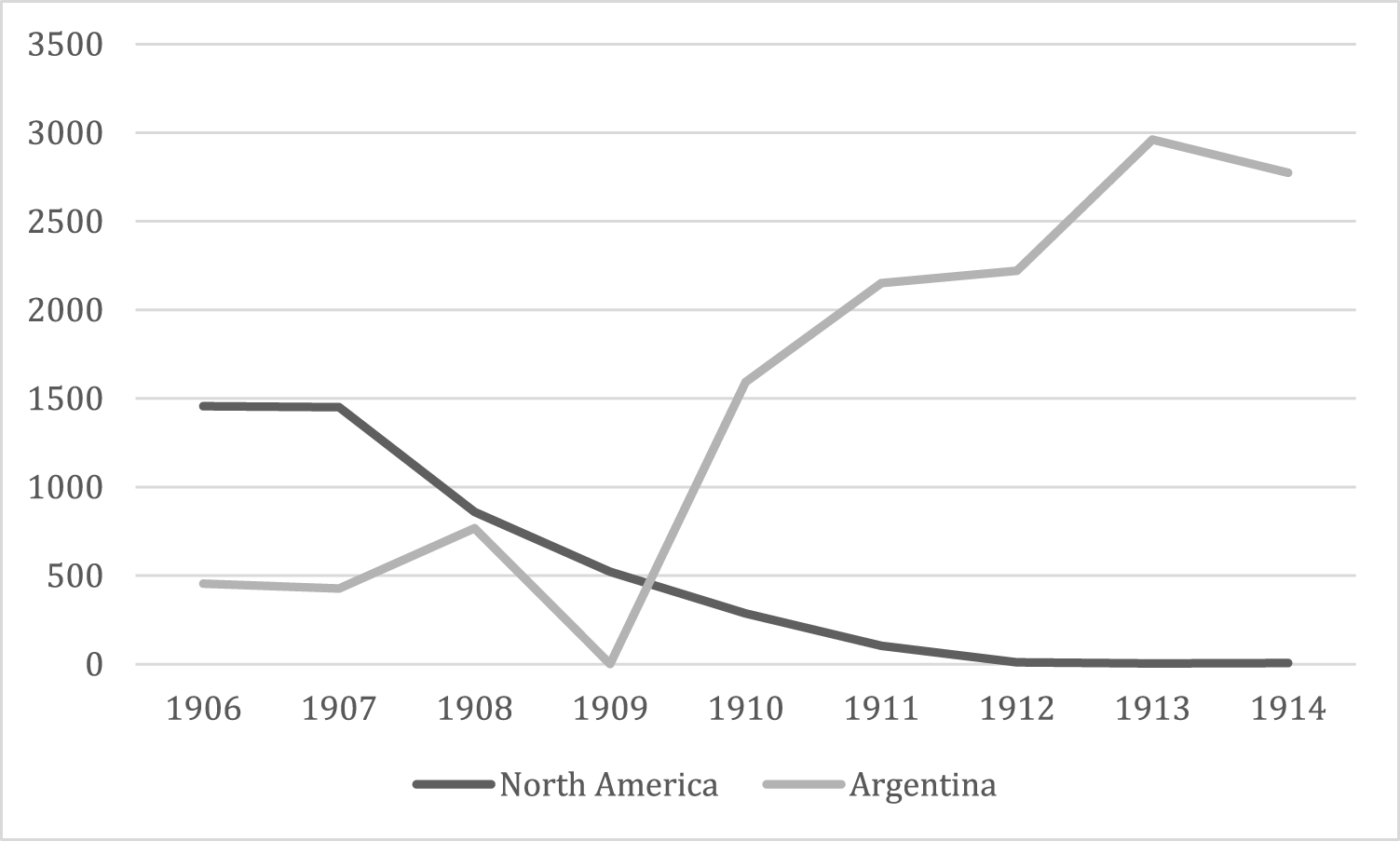

Therefore, the result of a macro-level market loss (see Figure 4) was the penetration of North American capital in South America.

Figure 4. Imports of chilled beef into the UK (number of quarters).

In 1905, the quantity of Argentine beef arriving in the United Kingdom exceeded that of US breeders for the first time. The migration of US firms to Argentina was a defensive strategy. US packers already faced competition in the British market over the industry’s most profitable product: chilled beef.

Indeed, from 1900 onward, the British-owned River Plate Fresh Meat Co. has perfected the technique of producing chilled meat and sent its first shipment to Great Britain in 1902 (Crossley and Greenhill, Reference Crossley, Greenhill and Platt1977).Footnote 9 It is not especially surprising that this was the firm that perfected chilling in Argentina as its strategy had been to pursue backward integration to control the business from the processing stage in the Río de la Plata area, transatlantic shipment and transportation, right up to wholesale and retail trade in Britain. In 1906 and 1907, imports of chilled beef from Argentina reached almost 500,000 “quarters” and already accounted for nearly 25% of the United Kingdom’s total meat imports (see Tables 1 and 2) (Weddel, Reference Weddel1917). As a result, Argentina became the first country to export both frozen and chilled meat, and some firms handled both products (Perren, Reference Perren1978).

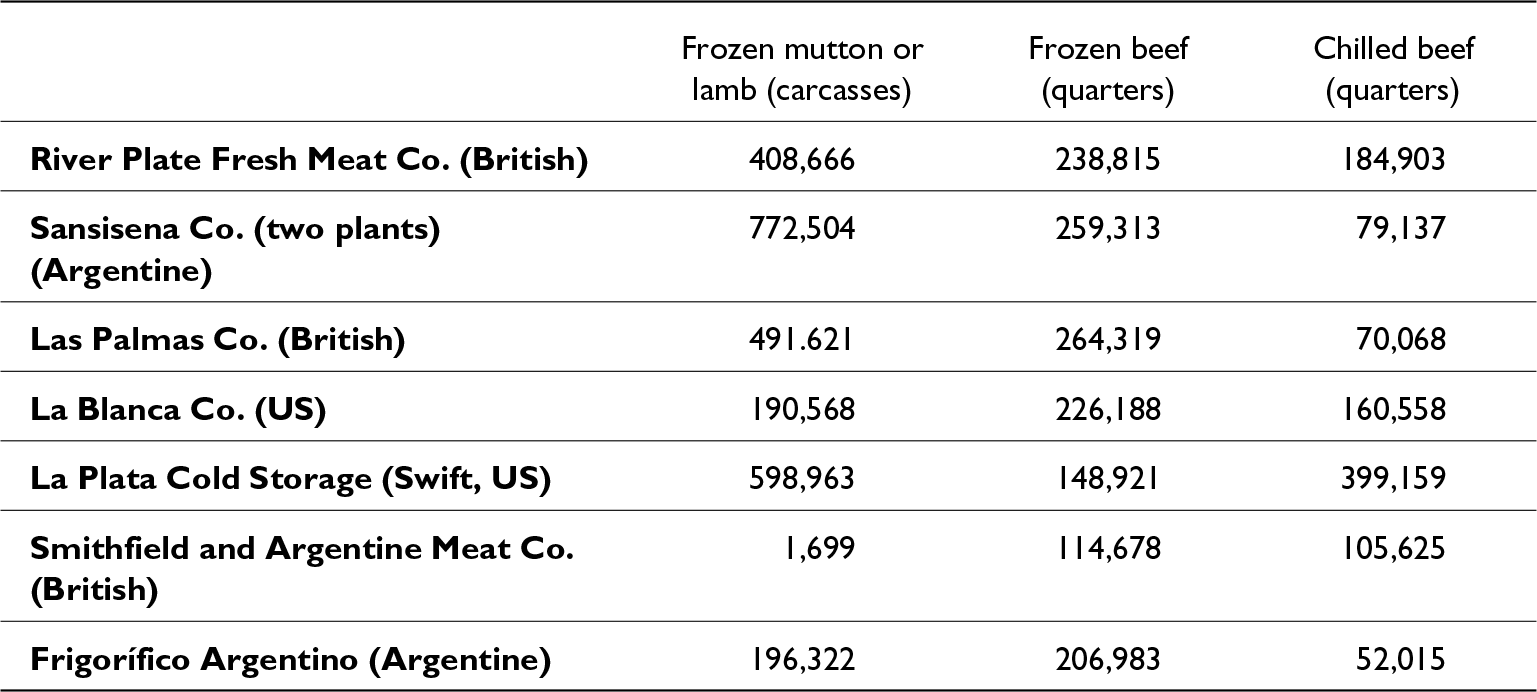

Table 2. Exports by firms in 1909, Argentine Pampas (number of carcasses and quarters)

Source: Own elaboration from the data provided by Whelpley (Reference Whelpley1911, p. 54). “Quarters” refers to quarters of beef carcasses.

To fully understand the dynamics behind the ongoing specialization in the production of chilled beef in Argentina, it is important to note that restructuring cattle-raising operations and fattening cattle on artificial pastures like alfalfa was necessary. This process occurred alongside new investments in meat processing and appropriate transportation. In this regard, by demanding higher-quality cattle, meatpackers encouraged these transformations but did not directly initiate them off. In contrast to what took place later in Brazil and Venezuela (and to a lesser degree in Uruguay), pampean ranchers invested in improving the genetics of their cattle: “the development of this chilled beef business has been a great factor in the development of the Argentine trade, and was rendered possible by the improvement in cattle stocks in Argentina, which enterprising estancieros have been carrying out for some years.”Footnote 10 The onset of chilled beef exports in the pampas brought about profound changes in the cattle-raising business in the region since it promoted two main kinds of cattle for slaughter: (a) the chillers, or top-grade calves, which had usually been fattened in special alfalfa pastures; and (b) the freezers, which were sometimes fattened and sometimes not. While the separation between breeders and fatteners was not rigid or absolute, it was contingent upon the trade in chilled beef, the most profitable part of the industry. In fact, from a broader perspective, refrigeration not only brought about significant changes in the sector but also played a pivotal role in Argentina’s industrialization (Bulmer-Thomas, Reference Bulmer-Thomas2003).

The US interests did not expand over the Chilean Patagonia. In this extensive productive area, local and British capital continued to predominate. The British capital was involved in the installation of a freezing plant in Río Seco, which opened in 1905 on the Magellan Strait, ten miles east of Punta Arenas. The owners were the South American Export Syndicate, in which the shipping companies Houlders Brothers and Co. and J. Gavin Birt and Co. were important investors. In addition, at the end of 1906, a number of ranch owners and merchants erected a freezing works at Puerto Sara (San Gregorio, 60 miles east of the Río Seco works), creating the Compañía Frigorífica de la Patagonia, the head office of which was in Punta Arenas (Pearse, Reference Pearse1920).

Similarly, it was capital from Britain, not from the United States, that made inroads into Venezuela before the First World War. The Venezuelan Meat & Products Syndicate Ltd. began operations at its freezing plant in Puerto Cabello in 1909. The factory did not perform consistently in its early years and faced difficulties selling Venezuelan meat in Britain due to its poor quality, though it eventually found markets in Italy and France (Valery, Reference Valery1992; Yarrington, Reference Yarrington2003). This British investment represented the initial effort to advance the meat export industry in the tropics.

4. Meat wars in Río de la Plata and the international meat pool

In Argentina, in 1909, the quantities exported (in quarters) by the main meatpacking plants are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 highlights a commonly overlooked issue in the sector’s analyses, related to the variety of export profiles for different types of products (and sub-products) offered by each meatpacking plant. It is worth, once again, noting that the tonnage of chilled beef exported by the British firms River Plate Fresh and Smithfield in 1909 was significant, even though Swift (La Plata Cold Storage) was the leading firm in the sector.

Market conditions remained tolerable in the Río de la Plata area for the packers until late 1910, when competition for cattle gave rise to heavy losses (Hanson, Reference Hanson1938, p. 159). Swift’s market presence and ambition to increase the export quota assigned to it led to a situation known in Argentina as the first “meat war” (1908–1911). The way out of the price conflict caused by Swift’s dumping came in the form of an agreement signed in 1911. Pressure from Anglo-Argentine interests played an important part in ending the confrontation as a result of their political clout and, particularly, Britain’s control of maritime transportation.Footnote 11 Figure 5 clearly illustrates the impact of the first meat war. Specifically, between 1908 and 1911, there was a notable decline in the prices of Argentine beef in the London market.

Figure 5. Wholesale prices of Argentine beef (first quality) in the London market (pennies per pound).

The volumes of global exports and weekly shipments were determined during meetings among the exporting companies. The packers admitted that this agreement regulated shipments from South America to Britain. In their view, the agreement was not only justifiable because it helped to make the reception of perishable meats in Britain more regular, but the arrangement itself, made necessary by the lack of adequate boat space, was not secret and was countenanced by British law (Hanson, Reference Hanson1938). Furthermore, the packers maintained that this arrangement was “similar to the form of cooperation specifically permitted by the Webb Bill, which is intended to encourage cooperation in exportation on the part of competing firms in the United States.”Footnote 12

The pool arrangements worked, in the sense that there were no reported abrupt oscillations in the prices for cattle or meat, and that packers made good profits. However, in 1913, Armour was completing the expansion of its new plant outside La Plata, relinquished its interests at La Blanca Co. (controlled by Armour and Morris), and asked for an increase in its market share (50% or 70% according to different sources).Footnote 13 The Times reflected how problematic these times were for British companies: “since the rupture of the conference, both the companies in American hands have so largely increased their shipments of chilled beef that a rapid and extensive rise in the price of fat cattle in the Argentine has resulted. The selling price of beef in this country has not been depressed, but, owing to the rise in Argentine costs, it has become impossible to ship chilled beef at a profit, and since chilled beef is the commodity with which the Anglo-Argentine Companies’ future is bound up, heavy losses are being incurred.”Footnote 14 US firms did not enter this second price war seeking self-preservation; rather, they sought for greater control of the Argentine beef export industry. By then, the US meatpackers’ largest foreign investments were located in Argentina (Wilkins, Reference Wilkins1974).

As a direct consequence of this second meat war, US firms now controlled 28% of the world’s output of frozen and chilled meat and could claim to have eliminated weak competitors.Footnote 15 Once again, during the Second Meat War (1912–1913), the wholesale price of Argentine beef in London experienced a more subdued increase, as illustrated in Figure 5. In this sense, US competitive pressures—and the need for economies of scale forced other companies to merge and to rationalize their production. In March 1914, Las Palmas Produce Co. Ltd. (controlled by James Nelson and Sons) merged with the River Plate Fresh Meat Co. Ltd. to form the British and Argentine Meat Company Ltd.,Footnote 16 years later acquired by the Vestey’s (Knightley, Reference Knightley1993, p. 22). Also involved in this operation was the British shipping company the Royal Mail Steamship Co. Ltd.Footnote 17 In this case, Chandler (Reference Chandler1990, p. 377) had argued that in the Río de la Plata area, “administrative centralization and rationalization did follow legal consolidation”. After the two firms consolidated their production facilities and sales forces and revamped their retail store, profits soon replaced losses despite continuing investments by American firms (Crossley and Greenhill, Reference Crossley, Greenhill and Platt1977).

This process also reduced the number of non-US companies from five to three: the British and Argentine Meat Co., Smithfield and Argentine Meat Co., and the Argentine-owned Sansinena Co. These surviving companies were efficient, so after this period of intense competition, US firms sought to collaborate in order to stabilize the market shares. Early in 1914, negotiations began for a new pool in the Río de la Plata area, which also included the new plant that Swift had been operating in Montevideo since 1912 (originally named Frigorífico Montevideo). The firms came to a new agreement in June 1914. For this last agreement, the South American Meat Importers’ Freight Committee (as it was called in the UK) reserved and allocated the tonnage for the transportation of refrigerated meat in the following terms: United States (58.50%), United Kingdom (29.64%), and Argentina (11.86%).

As Hanson (Reference Hanson1938, p. 236) observed, the strategies used in South America by the US packers to dominate the export market were not the same as in their home market (i.e., “interconnections with Banks and financial institutions, ownership or subsidizing of market publications, control of cattle loan companies, ownership of stockyards with control of packing-house sites and rendering business, and entry into unrelated lines of business”). Nor did the refrigeration car problem arise in Argentina because the main market was abroad and all packinghouses were built near or on the banks of navigable waterways to facilitate rapid shipments outside the country (for this reason, cold storage warehouses were not built either). As a consequence, the most vital factor in structuring this business was the “control of refrigerated ocean tonnage.”

Meatpacking operations in South America, especially in the Río de La Plata region, and their connections to foreign markets cannot be fully understood without first grasping the logic of marketing channels and recognizing the significance of managing shipments, coordinating available space for shipments, and executing the intricate distribution tasks at the final stage destination. As Forrester (Reference Forrester2014, 92) explains, “the chilled product (lamb and mutton were always carried frozen) was more expensive to carry, requiring refrigeration machinery capable of controlling and maintaining specific temperatures in the insulated hold spaces with air circulation around the carcasses, which were usually quartered and hung from the ceiling of the chambers rather than the solid stow used for frozen products.”

The coordination of shipments sets the Río de la Plata industry apart from other exporters, such as Australia and New Zealand. In these areas, rural producers had a more significant role in meat processing, and there were more meatpacking plants. As Critchell and Raymond (Critchell and Raymond, Reference Critchell and Raymond1912, p. 101) explained: “continuous supplies have enabled the Argentine companies to develop distribution pretty well on retail lines, and owing to regular and continuous imports into Great Britain, the Argentine houses have been able to avoid, to a great extent, the embarrassing accumulations and temporary scarcities which have so frequently caused disaster to those engaged in the necessarily more speculative Australasian trade, in which, unfortunately, there has always been a lack of continuity in supplies.” In this regard, the original “Río de la Plata way” was strengthened by the presence of US companies.

5. World War I: US expansion into Patagonia, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Brazil

World War I disrupted the meat trade globally (Albert, Reference Albert1988; Phillip, Reference Phillip2009; Aparicio et al., Reference Aparicio, Pinilla, Serrano, Lains and Pinilla2009). During the war years, trade with Britain was controlled and regulated by the British government, which favored some firms’ operations over others in the Río de la Plata area, particularly Las Palmas Co. As the British government arranged a special profit-sharing agreement with this recently reopened plant, it ensured a regular, though moderate, supply and provided measures for production costs and conditions in the River Plate (Hanson, Reference Hanson1938, p. 198).

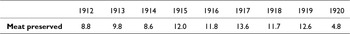

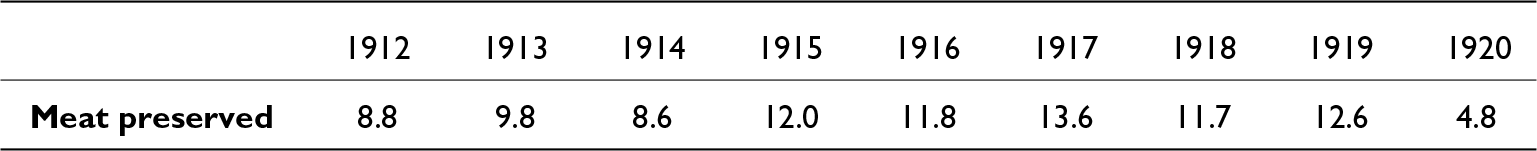

At the macro level, two related effects occurred. On the one hand, demand increased, leading to a temporary shift in the types of meat traded. Specifically, given its easier preservation, canned (and frozen) meat gained significance in British imports (see Table 3). On the other hand, the high demand, coupled with certain supply constraints, led to a surge in meat prices (see Figure 5). At the business level, this clarifies why the operations of US companies were impacted, though not severely. As the Review of the Frozen Meat Trade (Weddel and Co.) reported, in 1916, US companies operating in Río de la Plata handled 34% of the global production of frozen and chilled meat, up from 28% in 1913.Footnote 18 Furthermore, the dividends of US meatpackers like Swift, Armour, and La Blanca in 1915 were 28.3%, 22.4%, and 95.9%, respectively. That same year, the dividends of the British and Argentine Meat, and Smithfield Argentine – both British firms – were 44.5% and 43.7%, and that of Argentine meatpacker Sansinena, 25.6%.Footnote 19

Table 3. Preserved meat as a share of total meat imports in England, 1912–1920 (% of total import value)

Source: Imperial Economic Committee (1934). The annual average prices have been obtained from weekly prices. Meat preserved includes: Beef salted, tinned and canned and extracts, mutton and lamb tinned and canned.

In the Río de La Plata area, several readjustments occurred during this period. In 1914, the Frigorífico Argentino started operations; Armour opened a new plant in La Plata in 1914–15; and 1916 witnessed the establishment of the Anglo South American Meat Co., controlled by the Union Cold Storage Co., which had decided to come to South America. The war period was, therefore, a time of internal readjustments, shifts in meatpackers’ production profiles (regarding the predominant types of exports at the time), the influence of Vestey’s interests, and the strengthening of US firms in South America. The war period was, therefore, evidently a prosperous one for River Plate packing companies, despite transportation difficulties, labor troubles, and adverse conditions in international exchange. As stated in the Weddel Report in 1917: “the past year was apparently a very profitable one for most of the Argentine freezing companies, as much on account of their large Army contracts as on account of the high prices obtained in the British Market” (Weddel, Reference Weddel1917).

In Uruguay, Swift and Co. expanded its facilities, and Morris and Co. built a new plant in Montevideo named Frigorífico Artigas SA (Jacob, Reference Jacob1979; Bértola, Reference Bértola1991). In parallel, and seeking to broaden its interests in the region, Swift bought the Compañía Paraguaya de Frigorífico y Carnes Conservadas in 1917 (Parquet, Reference Parquet1987). This is a clear example of product diversification, as Swift exported canned meats, beef extracts, hides, skins, and blood from this location to the US and Europe.

The US interests in the meatpacking industry in Paraguay later expanded when the International Products Company (Compañía Internacional de Productos) merged with Central Products Co., which was involved in the meatpacking business in San Antonio (near Asunción), thus incorporating a new company under Paraguayan law (Winkler, Reference Winkler1929). The San Antonio factory opened its doors in 1911, when it began exporting preserved meat and hides. However, the company’s attempts to export frozen meat encountered opposition from the Argentinian authorities, who held up its boats at the port of Buenos Aires and prevented goods from being loaded onto refrigerated long-distance cargo ships, allegedly due to foot-and-mouth disease in Paraguay. From that point on, the plant focused on the production of corned beef, beef extracts, and other by-products (Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company, 1967, 87). Morris & Co. was also present in Paraguay controlling the Frigorífico San Salvador del Paraguay. In other words, although Paraguay may not have been a major player in global beef exports overall (see Table 4), this does not mean that it did not focus on meat by-products.Footnote 20

Table 4. Beef exports from different countries (thousands of quintals)

Source: Annuaire international de statistique agricole (1909–1939). One quintal = 100 kilograms.

The demand for lower-quality meat reduced barriers to entry, and new meat-exporting areas in South America (and by-products) were added to the industry. For example, two meatpacking plants opened in Argentine Patagonia (Frigorífico Río Grande and Frigorífico Armour de Santa Cruz). In Chile, meanwhile, three new meatpacking plants opened, strengthening the country’s export sector, which was linked exclusively to sheep farming and associated with vertically integrated “Magellanic” ranching capitals and British merchant houses (Miller, Reference Miller1993). In this respect, the largest ranching investment in the region was initiated by the Sociedad Explotadora de Tierra del Fuego, which began exploiting Frigorífico Bories in 1915. The company was organized with capital from Magellanic sources and the British trading house Duncan, Fox & Co., which aimed to diversify its interests in wool production, particularly in the production and export of frozen meat and other by-products. Two years later, La Compañía Frigorífica de Puerto Natales, owned by native Patagonian landowners such as Manuel Iglesias, Mayer Braun, and Rodolfo Stubenrauch (Martinic, Reference Martinic1985, p. 176), was formed in Punta Arenas to build a meat-freezing works at Última Esperanza, Magallanes Territory.

In Venezuela, as mentioned above, the Vestey’s took over the Puerto Cabello freezing plant, which they reopened in 1914 (it had been closed since June 1912) and increased imports by expanding its capacity to up to 500 head of cattle per day.Footnote 21 From 1919 onward, this company operated as the Venezuelan Meat Export Company Limited. It was a subsidiary of the Lancashire General Investment Trust Limited (which later became the Lancashire General Investment Limited Company). The company was registered in London on July 13, 1911, and purchased land in Venezuela from 1914 onward. It came to control approximately one million hectares, thus becoming the largest landowner in the region known as the Central and Western Venezuelan Llanos (Briceño, Reference Briceño1985).

These land purchases were part of a strategy to counterbalance the problem of low-quality Venezuelan beef. According to the existing literature, Vestey’s operations in Venezuela went through different stages. Although various tax benefits helped the company, it also experienced difficulties due to its changing (and corrupt) relationship with the Gómez administration (Yarrington, Reference Yarrington2003). Another factor that contributed to its failure was the plant’s unsuitable location, far from the areas where cattle were raised and from the docks from which the finished frozen products had to be shipped. This raised operating costs and, consequently, the firm only functioned as long as high beef prices made it viable.

An additional failure that shows how the growth of tropical ranching was mainly possible during World War I is the Packing House located in Coveñas, situated on Colombia’s Caribbean coast. Van Ausdal (Reference Van Ausdal, Winder and Dix2016) argued that integrating Colombia into North Atlantic beef markets (and, perhaps, global markets) was not self-evident, as tropical cattle were considered unsuitable for northern palates. However, as explained above, during World War I, British interests shifted to Venezuela, meanwhile US interests focused on Colombia. From 1909 onward, the Colombian government enacted a series of laws aimed at attracting the capital and expertise necessary to establish a meatpacking industry plant. However, it was not until 1918 that three groups submitted bids to do so. One of these was from the Colombian Products Company, a joint venture between four ranching operations on the Caribbean coast and the US-based International Products Co. This plant only started operations in 1924 and couldn’t sell its products abroad, showing that the window of opportunity for developing tropical beef exports from both Venezuela and Colombia was very short due to their lack of competitiveness.

The Colombian case also shows a more active role of the State in promoting the development of the meatpacking industry in South America, including passing a series of laws designed to attract the capital and expertise needed to build a meatpacking plant in Coveñas. As Van Ausdal (Reference Van Ausdal, Winder and Dix2016) analyzed, the failed attempts to promote Colombia’s tropical area as a global beef producer were based on an optimistic vision by government officials and industry boosters, who believed that it would be possible to transform the tropical environment by adopting modern management practices. Nonetheless, as the author argues, the failure of the Colombian meatpacking plant was rooted more in natural than social factors.

Finally, one of the most significant developments during World War I was the expansion of U. interests into Southern Brazil. The country made its first shipments to Europe in 1914 during World War I. However, since the second half of the nineteenth century, large areas like Rio have been well supplied with meat, initially in dry form and later refrigerated (Lopes, Reference Lopes2021). However, the low quality of Brazilian meat explains why it was used only by the Italian and French armies (Pearse, Reference Pearse1920). US companies were aware of the challenges and limitations of expanding the meat industry in Brazil, which stemmed from the poor quality of cattle, their high relative prices, and a series of official regulations governing exports and domestic market operations.

Nevertheless, both Swift and Co. and Armour and Co. constructed new factories in Brazil. The entry strategy was to buy existing plants, just as it had been in Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay (Pasavento, Reference Pasavento1980; Perinelli Neto, Reference Perinelli Neto2009; Wilson and Szmrecsányi, Reference Wilson, Szmrecsányi, Silva and Szmrecsányi1996). As highlighted earlier, this article suggests that the involvement of US companies in marginal areas enabled them to broaden their export profile, specifically targeting canned beef, jerky, and various meat products. In contrast to Paraguay, Brazil’s emphasis on lower-quality meat positioned it as a minor participant in the global beef market during the 1920s (see Table 4).

Therefore, a key difference between operations in Brazil (and other productive areas, such as Venezuela) and those in the Río de la Plata was that companies in Brazil needed to improve the quality of their cattle, leading to greater backward integration. Armour in Brazil, for example, had set up an area “to institute through this department an active campaign of education among breeders and to loan them stud animals, when necessary, as well as to sell breeding animals practically at cost prices.”Footnote 22 In Brazil, World War I prompted the enactment of more comprehensive laws impacting the domestic meat industry. The national government established a Superintendency of Provisions to regulate food prices and distribution until 1926. It also approved the construction of a federal retail warehouse in Rio for selling goods at prices determined by the Federal District’s prefect. Moreover, federal governments offered smaller incentives to attract investors, such as guaranteeing a 6% profit to a packing house in Rio Grande do Sul, which allowed it to receive nearly US$ 300,000 in payments annually. According to Topik (Reference Topik1980), the laissez-faire approach of this period should be better understood as relative rather than absolute, with state activity driven more by practical needs to adapt to Brazil’s economic and political conditions than by abstract principles.

It is worth pointing out that US companies were not the only ones investing in Brazil during the war years: the British group Vestey began operations there almost simultaneously with the one they established in Argentina and Venezuela. However, at first, these had a smaller scope. Despite these US and British investments, Brazil’s performance in the global meat market was erratic during this period, and meat was never a particularly significant product within Brazil’s export basket. As a result, although World War I marked Brazil’s entry into the global meat market, the Río de la Plata area consolidated itself as the leading global meat specialist during this period.

This, along with the antitrust investigation in the US and Argentina’s favorable conditions as a host country (Lluch, Reference Lluch and Lluch2015), could explain why, in 1918, Swift Co., then the world’s largest meat producer, established an incorporated Argentine company named Compañía Swift Internacional SAC to manage its nine plants in Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Paraguay, and Australia, which it accomplished through five subsidiaries. In 1918, the stockholders of Swift & Co. (US) were given the option to exchange 15% of their shareholdings at par for shares in Compañía Swift Internacional. The capitalization of the latter was 22,500,000 Argentinean gold pesos, the share having a par value of 15 gold pesos. By 1919 (and until 1950), Compañía Swift Internacional SAC owned the entire capital stock of the following companies: (1) Compañía Swift de La Plata SA, Buenos Aires, operating meat slaughtering and freezing works at the port of La Plata, Río Gallegos, and San Julián, and a selling and distribution agency in the city of Buenos Aires; (2) Compañía Swift de Montevideo SA, which operated a meat slaughtering and freezing works in Cerro and a selling and distributing agency in Montevideo; (3) Companhia Swift do Brazil SA, which operated a meat slaughtering and freezing works at the port of Rio Grande do Sul and a sales agency in Rio de Janeiro; (4) Compañía Paraguaya de Frigorífico de Carnes Conservadas, which ran a canning and dried beef plant on the Paraguay River near the city of Asunción; and (5) the Australian Meat Export Company Limited, which operated meat slaughtering and freezing works in Brisbane and Townsville, Queensland, Australia. Swift’s global operation is an issue that needs further investigation. This is a clear example of the interconnections formed by multinationals involved in food products during the first global economy. It illustrates explicitly how an MNE’s transboundary structure confronts changes in its home regulatory environment.

6. British and US capital in the consolidation of the South American beef industry (1921–1930)

The 1920s were a period of growth and increased consolidation in the South American meatpacking industry. It was also a time of growth in Argentine exports of chilled beef. Uruguay’s contribution of chilled beef was small, while Brazil’s and Venezuela’s were nonexistent. Despite several European countries initiating an increase in tariff barriers on the import of meat and live animals, Britain continued with a liberal trade policy. As a result, the share of its global meat imports increased from just over 60% in 1925 to over 80% in 1932. Additionally, the global weight of meat and live cattle in relation to the total agri-food trade, which was slightly over 5% in the years before World War I, solidified at around 8% in the 1920s (Delgado et al., Reference Delgado, Pinilla and Aparicio2022).

In the Río de la Plata area, the most notable feature of this period is the consolidation of three companies that made substantial investments up through the end of the 1920s, which explains the boom in chilled beef exports. The 1920s also saw significant adjustments to the corporate landscape. Meanwhile, the plants in Colombia and Venezuela closed, and new players entered the Río de la Plata. For example, Swift opened up in the city of Rosario (1924), and other firms expanded their facilities. However, the most significant aspect was a series of mergers and acquisitions linked to the expansion of the Vestey group in South America, which had arrived in the region during World War I but waited until this time to expand its operations. To this end, the company invested in a new plant in Argentina, the Frigorífico Anglo (1925). In parallel, it expanded into Uruguay, where no firms were owned by local capital; therefore, it acquired the former British-owned Liebig plant. Meanwhile, in Brazil, it purchased three locally owned meatpacking plants.

This situation indicates that in the 1920s, the British group Vestey emerged as the most active and competitive global player in the industry. By that time, it had become a fully vertically integrated firm, overseeing approximately 2,400 retail meat stores in Great Britain, as well as meatpacking plants in South America, Australia, New Zealand, China, and Madagascar. Additionally, it operated facilities in Russia before World War I. As described by Robert McFall in 1927: “Until recently, it also owned a fleet of refrigerated steamers over which it still has control. This combination has more branches of the industry under one management than do the packers, for it retails meat on a large scale, partially controls its shipping space and even has considerable ranching property” (Mcfall, Reference Mcfall1927, 566). The Union Cold Storage Company also had cold stores in London, Liverpool, Manchester, Hull, Glasgow, Leeds, Newcastle, Bristol, and Southampton (Bishop, Reference Bishop1923, p. 34) and it controlled W. Weddell & Co (Ltd.) which sold some of the meat wholesale on commission and published The Review of the Frozen Meat Trade.Footnote 23

In Venezuela, the Vestey’s faced such significant political and economic challenges that they temporarily shut down the Puerto Cabello plant, and later closed it permanently in 1926. During this time, they diversified their markets by entering live cattle sales in Colombia and shifted their focus from meatpacking to cattle farming. Meanwhile, in the Río de la Plata region, the meatpacking plants controlled by the “Anglo group” were expanded and modernized, and less competitive plants were either closed or sold off.

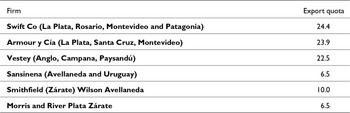

In the Río de la Plata area, a new (and third) meat war began due to the changing circumstances. In June 1925, Vestey informed the River Plate Freight Committee that it wanted to raise its quota to 8.5%, as it had increased its capacity by 75% and updated its sales methods system. In addition, Smithfield and Argentine Meat Co. also argued that they had modernized their plant and demanded a two-thirds increase in their quota. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, Swift established a new plant in Rosario in 1924 and requested an increase in quotas. The General Manager of the Smithfield and Argentine Co. expressed his concern for the situation clearly in the 1925 Annual Report: “[it is a] fight between the bigger concerns who ship whatever quantity of meat they like, with the result that prices are too high in the Argentine and too low here.” He also recognized that from the moment firms were established in Argentina (in 1904), their share of the trade was “whittled away as new companies entered and new circumstances arose.” However, he argued that since the company decided to “put our house in order” they now deserved “our undeniable right to our fair share of the trade.”Footnote 24

His words also indicate that the struggle in the 1920s in Río de la Plata was no longer a contest between US and British firms. Instead, from that point onward, it became a competition between large packers and small ones. Despite financial losses, the price war continued for over two years (see Figure 5). But as the Weddel Report commented, US firms encountered a critical difference in circumstances as compared with the previous decade: “this time they find themselves opposed not by comparatively small concerns which they found an easy prey in pre-war days, but by a British combination which, with several thousand retail shops, is more favorably placed to make a stand against being put in an inferior position to its principal competitors” (Weddel & Company Ltd., 1928, p. 5). In October 1927, a new agreement was reached on these terms, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Beef export quotas by firms established after the Third Meat War in the Río de la Plata (in volume, %)

Source: Own elaboration from the data provided by Liceaga (Reference Liceaga1952, p. 106).

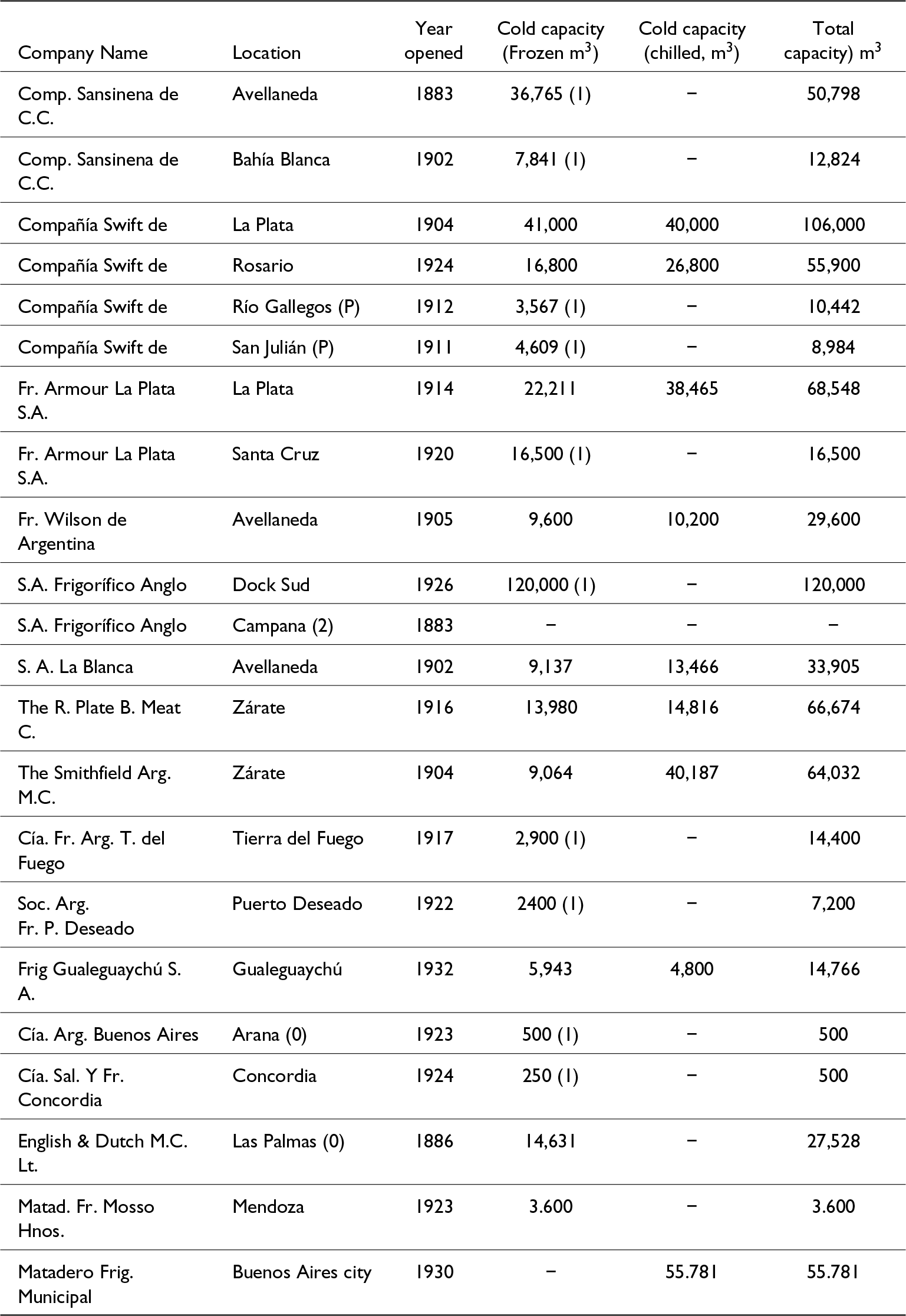

The pressure to limit competition following the new agreement led to ongoing mergers and acquisitions in Argentina (the readjustments in Uruguay and Brazil happened before the start of the third meat war). The reaction of the smaller surviving companies was to improve their positions by mergers, joint selling, or production agreements. As part of these changes, in 1927, the River Plate Freight Committee rented the Las Palmas frigorífico for four years at £90,000 per year and kept it closed. Another change occurred in July 1928 when the River Plate British and Continental Meat Co. signed an agreement with Armour and Co. As a result, Armour and Co. assumed all technical management. After this contract was signed, the River Plate Freight Committee allocated the arrangement by granting equal shares to the Vestey Brothers, Swift, and Armour. Profits and losses fluctuated significantly during the 1920s, and some British firms experienced negative performance (this was not true for US firms specializing in chilled beef). Similarly, the only remaining Argentine company, Sansinena, faced difficult times (even though it continued with its capitalization strategy). After the antitrust law was enacted in Argentina, it had to temporarily withdraw from the River Plate Freight Committee. As part of these adjustments, the surviving meatpacking plants all over South America deployed parallel strategies such as focusing more on the domestic market and deepening related productive diversification processes (Lluch, Reference Lluch and Lluch2015). By 1930, the number of meatpacking plants (excluding small mutton plants in Patagonia) in Argentina stood at less than a dozen, and their production capacities varied greatly. Table 6 shows their profiles.

Table 6. Meat packing plants operating in Argentina by 1930 (cold storage capacity in cubic meters, m3)

(0) Closed plants, (1) freezing and chilled, (2) destroyed by fire.

Source: Own elaboration from the data provided by VI Congreso Internacional del Frio (Vi Congreso Internacional del Frío, 1932, p. 15).

This consolidation level was not driven by state intervention. In fact, the Argentine governments believed that potential political interference in the packing industry would violate the principles of “good government.” It wasn’t until the 1920s that a coalition of ranchers—mainly breeders and some fatteners—rejected passive approaches of waiting for overseas markets to recover. Instead, they launched a determined effort to take the meatpacking industry under government regulation. Additionally, higher domestic prices led to a sharp decline in beef consumption in Buenos Aires, which helped form a consumer-rancher alliance for the first time in Argentina’s congressional history (Smith, Reference Smith1969, pp. 75–78). However, this initial attempt to regulate meatpacking plants in Argentina failed because they resisted regulation. It is clear that controlling beef sales channels—especially the meat export industry operated by meatpacking plants—was the main leverage used to pressure ranchers and the government. As a result, state regulation was only nominally enforced, and no legal action was taken against the beef trust. The only lasting achievement was the introduction of cattle sales by live weight in April 1924. Neither the meatpackers’ cooperation patterns were ever prosecuted under Argentina’s 1923 anti-trust laws. Even when official measures aimed to change the business practices of packinghouses, this sector managed to forge strategic alliances with the largest breeders and resisted any state intervention throughout the 1920s and into the 1930s. Of course, the strategies of packers evolved over time and required self-regulation, which was carried out through regular meetings, as described earlier, enforced by a private system of fines and penalties.

Argentina’s meatpacking companies’ ability to resist regulatory attempts was rooted in their high level of forward integration: each of the major packers combined freezing, shipping, and marketing. This trait initially distinguished, as mentioned earlier, the Río de la Plata industry within the UK market from other new exporters like Australia and New Zealand. Additionally, the failure of regulation should also be understood in the context where government interventions in rural policies were (until the 1930s) limited, gradual, and targeted, with little progress on issues such as land ownership reforms and the organization of agriculture credit.

The consolidation process also impacted Brazil, which, by the end of the 1920s, was seen as “a country of boundless opportunities but which has failed heretofore to realize its fullest opportunities.” The Weddel Report endorsed this perspective: “Brazilian chilled beef has still a long way to go to equal the Argentine standard of quality but meets with a fair market in Britain because of the demand for small quarters” (Weddel & Company Ltd., 1928, p. 15). Consequently, Brazil remained a minor player in the global meat market, and its production and marketing model diverged from that of the Río de la Plata, as it lacked agreements on shipping quotas. In other words, although it had a certain global significance in terms of quantity (see Table 4), this remained relatively low. In Paraguay, the crisis also affected the meatpacking plants, some of which were converted into plants for canned meats and other by-products. An example of this is the 1923 opening of the British company Liebig’s new processing plant, which was established in repurposed facilities that had previously belonged to the Compañía Paraguaya de Frigoríficos y Carnes at Zeballos-Cué.

In Patagonia, meanwhile, two different models emerged: on the Argentine side, operations were mainly controlled by US companies that had diversified their export profile, while on the Chilean side, five meatpacking plants with limited operational capacities and lower levels of technology continued to function by the end of the 1920s. These companies were forward vertically integrated as most represented ranching interests that operated on both sides of the Andes. This explains why only one of these plants—Río Seco, owned by the South American Export Syndicate Ltd.—processed animals solely from Chile. The other plants (Tres Puentes, founded in 1923, Puerto Sara, Natales, and Bories) handled some animals from ranches on the other side of the Andes, although in varying proportions. For example, 25%–30% of the animals processed at the Bories meatpacking plant (owned by the Sociedad Explotadora de Tierra del Fuego) and Puerto Sara (controlled by the Compañía Frigorífica de la Patagonia) were from Argentina. In comparison, this share grew to 40% or 45% at the Tres Puntas plant, and reached as high as 90% at Frigorífico Natales, which had been restructured in 1924 (Calderón, Reference Calderón1937). This demonstrates the porous geopolitical boundaries regarding the production and trade of commodities and food products (Machado, Reference Machado2013).

At the end of the period analyzed, all the meatpacking plants involved in the export business in South America were private, and nearly all were foreign-owned (Vi Congreso Internacional del Frío, 1932). During this period, the three biggest firms (Swift, Armour, and Vestey) took a large share of business away from their smaller surviving rivals. This implied increased concentration and consolidation within the industry.

7. Conclusions

This article re-examines the changes in ownership structure within the South American meatpacking industry up to 1930. It does so from a transnational perspective to emphasize connections and comparisons and to enhance understanding not only of the differences between the South American beef industry and that of the rest of the world but also within the region. This has been achieved by enhancing a narrative on the evolution of the meat industry with quantitative and macroeconomic data, thereby connecting the quantitative aspects of economic history with business history. In quantitative economic history, identifying a business approach is challenging, although companies play a crucial role in influencing macroeconomic variables. The reverse is also true: articles centered on business often lack a quantitative context for business behavior. In our work, we strive to combine both perspectives and analyze how these approaches develop over time. For instance, we have noted the impact of price wars on beef prices in the London market. In other words, disagreements among corporate collusions over how to divide market share have a real effect on international wholesale meat prices. Moreover, the varying success of meat companies, along with their expansion into different countries, was reflected in the exports of each region. The dynamics of this industry responded to the growing geographical specialization in the production and export of processed meat globally, which was in turn associated with the availability of new technology and the rise of large-scale companies within the sector. In this sense, Argentina (in both the Río de la Plata area and Patagonia) was one of the first places, although not the only one, where large US meatpacking firms expanded internationally after 1907. This was also true of Uruguay, Paraguay, and Brazil from World War I onward. The cases of Colombia and Venezuela have demonstrated that, during a short-lived period, a meat industry cluster even emerged in the tropical regions of South America.

The article has verified that the nationalities of the major meat-exporting companies were mixed. Although the proportion controlled by each nationality was subject to change, the industry was not entirely dominated by US companies (the so-called greatest trust in the world) from the early twentieth century onward, as some have asserted.Footnote 25 It has been demonstrated that British and local capital (Argentine, Uruguayan, Brazilian, Venezuelan, Chilean, and even Colombian) remained active participants in the industry. Regarding Britain, the article has emphasized the importance of free-standing companies, the role of merchant and shipping houses in Chile, and the growing significance of the Vestey group after World War I. Since then, this group had become an integrated multinational company that controls every part of the food processing and distribution chain and, until the mid-1920s, owned the Blue Star Line, the largest refrigerated fleet in the world (Perren, Reference Perren2008).

By 1930, Vestey, along with Swift and Armour, had captured a large portion of the market from smaller competitors. The industry had become increasingly concentrated. As proposed, from the mid-1920s, the scale, financial, and marketing capabilities of each firm became more important than its nationality. The above does not mean we should ignore US companies’ transformational impact on the meatpacking industry in South America. They vastly scaled up chilled meat exports from Río de La Plata and expanded into almost all productive zones in the region as they pursued economies of scope. Instead, it has been argued that it is crucial to make sure that an analysis includes the differences in the size and export product specialization of each MNE. In particular, it is essential to note the differences between chilled and frozen meat, as well as between mutton and lamb, since these southern areas continue to be significant, especially for meatpackers located in southern Argentina and, to a lesser extent, Chile. For example, the expansion of US capital toward Argentine Patagonia enabled firms to increase the volumes of the frozen mutton they exported. Likewise, the expansion into Brazil (and Paraguay and Venezuela) further diversified the export basket of companies such as Swift, Armour, and the Union Cold Storage Co. As a result, the multiproduct profile gradually expanded as large meatpacking companies leveraged economies of diversification into new products and areas, enabling the largest firms to cross-subsidize their operations (Gebhardt, Reference Gebhardt2000).

Finally, and although the article has shown that throughout the period, there was a continual predominance of foreign capital, higher levels of concentration, and cooperation agreements between packers in Río de la Plata, it has also demonstrated the major readjustments that took place within the sector over time. The industry as a whole underwent considerable structural change during these decades, a phenomenon that local historiographies have often overlooked. There were many retreats, mergers, exits and failures. Although deep-rooted historiographical traditions have resulted in the meatpacking sector being analyzed as a uniform bloc and using a national methodological approach, this article proposes that during this historical period, there was a geographic specialization among meatpacking plants (some of which were owned by the same companies in different productive areas), creating cross-border connections and networks of products, capital and know-how.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply indebted to the anonymous referees and the editor of the journal for their valuable comments and suggestions. Any remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the authors. This study has received financial support from the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain (project PID2022-138886NB-I00) and from the Department of Science, Innovation and Universities of the Government of Aragon (project S55_23R).

Sources and official publications

Annual Statement of the Trade of the United Kingdom with Foreign Countries and British Possessions (1854–1935) and Statistical Abstract for the United Kingdom, Parliamentary Papers. London

Imperial Economic Committee. (1934). A Summary of Production and Trade in British

Empire and Foreign Countries. London.

Marketing Board (1932): Meat. A Summary of Figures of Production and Trade Relating to Beef, Mutton and Lamb, Bacon and Hams, Pork, Cattle, Sheep, Pigs and Canned Meat. London.

The Economist (1917): 23 June, p. 1149.

The Scotsman, January 22, 1925, p. 9

The Times, Special Article, London, Tuesday, June 17, 1913.

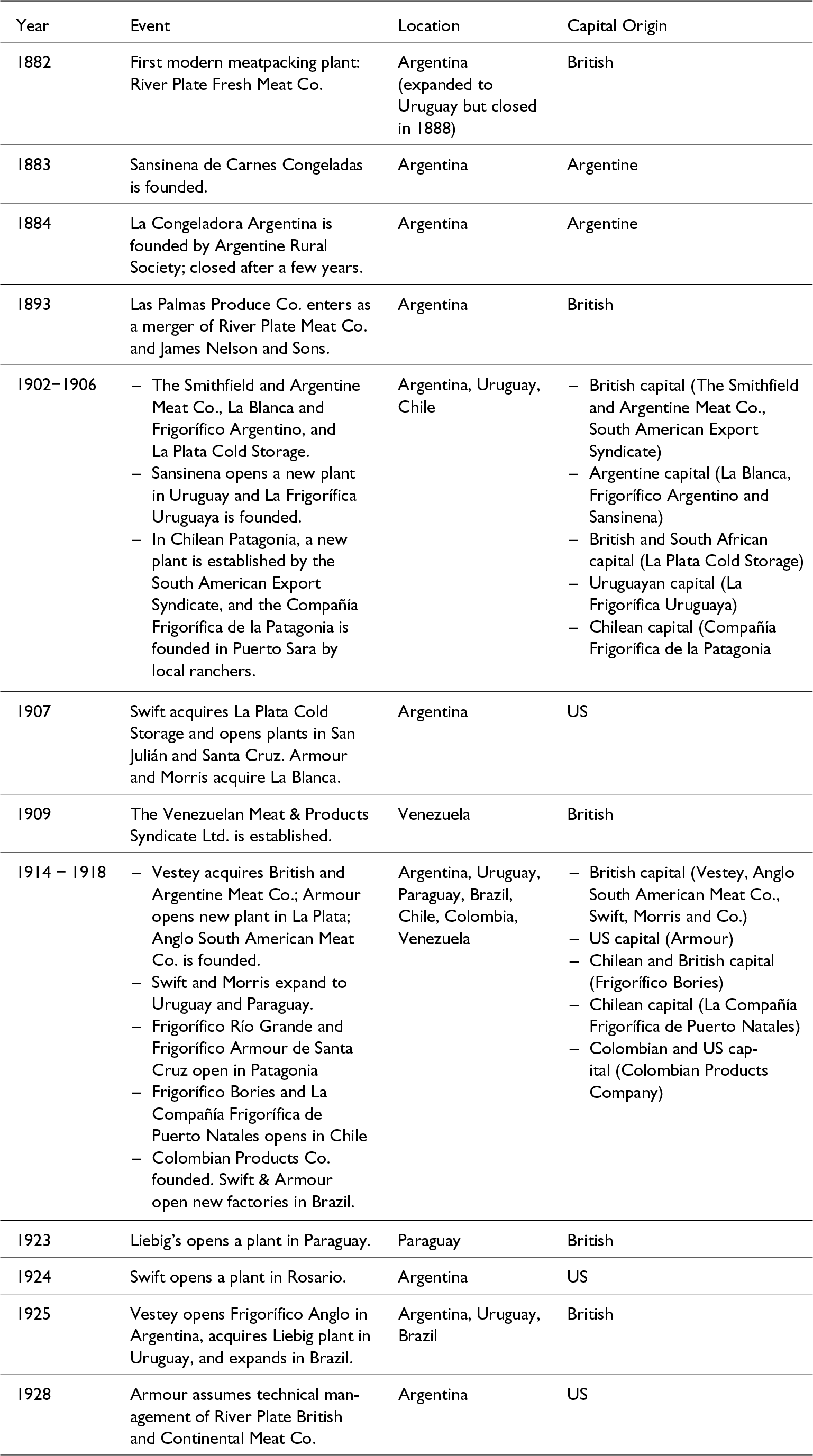

Appendix

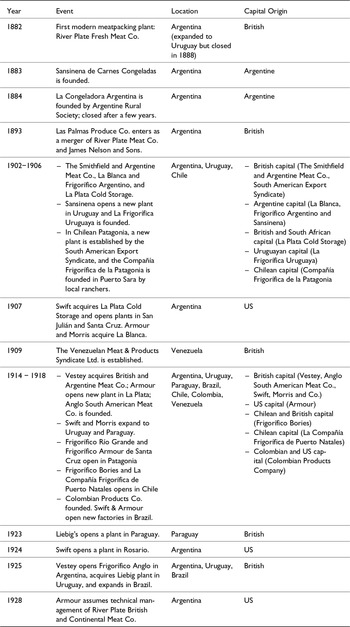

Table A1 Major openings and acquisitions of meatpacking plants in South America

Source: Own elaboration.