1 Introduction

The key technologies of all high-power lasers are chirped pulse amplification (CPA) or optical parametric chirped pulse amplification (OPCPA). Pulse stretching, amplification and compression inevitably lead to temporal contrast degradation, that is, to the formation of a pre-pulse long before the main pulse and the post-pulse after the main pulse. Contrast degradation occurs in a wide time interval from 100 fs to nanoseconds. The pre-pulse is hazardous, as the target may be destroyed before the arrival of the main pulse, which restrains laser application, especially in experiments with solid targets. Many causes of contrast degradation are of a temporal nature, so they may be analysed, as a rule, in the time domain. These include the amplified spontaneous emission from a seed laser and amplifiers (both laser and parametric), amplitude and phase distortions of the temporal spectrum of the pulse and residual reflections and nonlinearity of the refractive index[ Reference Li, Leng and Li 1 ]. A special case is light scattering on optical elements, which leads to the appearance of a noise field with a wide spatial spectrum. The propagation of such a field in a compressor or a stretcher leads to space–time coupling (see Refs. [Reference Dorrer2,Reference Jeandet, Jolly, Borot, Bussière, Dumont, Gautier, Gobert, Goddet, Gonsalves, Irman, Leemans, Lopez-Martens, Mennerat, Nakamura, Ouillé, Pariente, Pittman, Püschel, Sanson, Sylla, Thaury, Zeil and Quéré3] and references therein).

The physical reason for contrast degradation due to space–time coupling is the overtaking/lagging of the scattered pulse behind the main pulse. Lagging is the most frequent case. However, if one pair of gratings is located between the scatterer and the target (‘half’ of the compressor or stretcher), part of the scattered radiation overtakes the main pulse, resulting in the appearance of a pre-pulse. Since the time of overtaking is proportional to the spatial frequency, only small-scale fluctuations in the field amplitude or phase are significant for the contrast.

There are several reasons for scattering. First of all, it is an imperfect surface quality of the optical elements. The influence of imperfection on contrast was first numerically revealed in Ref. [Reference Bagnoud and Salin4]. Most subsequent works were devoted to numerical[

Reference Webb, Dorrer, Bahk, Jeon, Roides and Bromage

5

–

Reference Kiriyama, Mashiba, Miyasaka and Asakawa

13

] and experimental[

Reference Webb, Dorrer, Bahk, Jeon, Roides and Bromage

5

,

Reference Schanz, Roth and Bagnoud

8

,

Reference Li, Tokita, Matsuo, Sueda, Kurita, Kawasima and Miyanaga

10

–

Reference Zhu, Xie, Ouyang and Zhu

12

,

Reference Ranc, Blanc, Lebas, Martin, Zou, Mathieu, Radier, Ricaud, Druon and Papadopoulos

14

–

Reference Roeder, Zobus, Brabetz and Bagnoud

19

] studies of this effect both in the stretcher[

Reference Webb, Dorrer, Bahk, Jeon, Roides and Bromage

5

-

Reference Schanz, Roth and Bagnoud

8

,

Reference Li, Tokita, Matsuo, Sueda, Kurita, Kawasima and Miyanaga

10

–

Reference Roeder, Zobus, Brabetz and Bagnoud

19

] and in the compressor[

Reference Xie, Zhu, Zhu, Sun, Yang, Zhu, Guo, Kang and Gao

6

,

Reference Schanz, Roth and Bagnoud

8

–

Reference Kiriyama, Mashiba, Miyasaka and Asakawa

13

]. A theory without allowance for the diffraction and dispersion of a spatial chirp was proposed in Ref. [Reference Dorrer and Bromage20], developed in Ref. [Reference Bromage, Dorrer and Jungquist21], and later supplemented in Ref. [Reference Roeder, Zobus, Brabetz and Bagnoud19]. It was shown that the contrast is determined by the power spectral density (PSD) of the surface profile of the second and third gratings of stretcher/compressor and stretcher mirrors. These works are mainly focused on the intensity contrast in the far field, which is extremely difficult to measure. As a rule, the power contrast ratio (PCR)

![]() $\mathbb{C}(t)$

is measured as follows:

$\mathbb{C}(t)$

is measured as follows:

where

![]() $<{P}_\mathrm{out}(t)>$

is the pulse power and

$<{P}_\mathrm{out}(t)>$

is the pulse power and

![]() ${P}_{0, \mathrm{out}}(t)$

is the power of the main pulse (neglecting the scattered field). Since the near and far fields are related by the spatial Fourier transform, then, according to Parseval’s theorem,

${P}_{0, \mathrm{out}}(t)$

is the power of the main pulse (neglecting the scattered field). Since the near and far fields are related by the spatial Fourier transform, then, according to Parseval’s theorem,

![]() $P(t)$

is the same in the near and far fields; consequently,

$P(t)$

is the same in the near and far fields; consequently,

![]() $\mathbb{C}(t)$

is also the same. Moreover, the analysis of Equation (13) from Ref. [Reference Bromage, Dorrer and Jungquist21] shows that in the near field the intensity contrast differs little from the power contrast. This means that the magnitude of

$\mathbb{C}(t)$

is also the same. Moreover, the analysis of Equation (13) from Ref. [Reference Bromage, Dorrer and Jungquist21] shows that in the near field the intensity contrast differs little from the power contrast. This means that the magnitude of

![]() $\mathbb{C}(t)$

is measured, even if the contrast meter covers only part of the aperture. Expressions for the PCR as a function of the PSD of the compressor/stretcher grating surface and the transport optics were obtained in Ref. [Reference Khazanov22] taking into account diffraction and all orders of dispersion.

$\mathbb{C}(t)$

is measured, even if the contrast meter covers only part of the aperture. Expressions for the PCR as a function of the PSD of the compressor/stretcher grating surface and the transport optics were obtained in Ref. [Reference Khazanov22] taking into account diffraction and all orders of dispersion.

At the same time, in addition to surface roughness, other optics imperfections whose influence has not been studied before also contribute to the PCR. First of all is the radiation scattering on dirt/damage/obscurations that inevitably appear both during the production of gratings and mirrors and in the course of their operation in high-power laser facilities[ Reference Spaeth, Manes, Widmayer, Williams, Whitman, Henesian, Stowers and Honig 23 ]. Following Ref. [Reference Spaeth, Manes, Widmayer, Williams, Whitman, Henesian, Stowers and Honig23], we will assume that the obscurations ‘absorb’ all incident laser light. Besides the roughness and obscurations of the beamline optics (gratings and mirrors), the roughness and obscurations of the mirrors used for writing holographic gratings also lead to degradation. They give rise to groove-shaped fluctuations leading to reflectivity fluctuations[ Reference Koch, Lehr and Glaser 24 ] as well as to non-equidistance and non-parallelism of the grooves, which in turn result in wave front fluctuations of diffracted radiation[ Reference Bienert, Röcker, Dietrich, Graf and Ahmed 25 – Reference Kochetkov, Shaykin, Yakovlev, Khazanov, Cheplakov, Wang, Jin, Liu and Shao 28 ]. In this work, we investigate in a general form the PCR caused by four reasons: roughness and obscurations of both beamline optics and writing optics. The only constraint that will be used is the spatial scale of obscurations and roughnesses and, hence, of the scattered radiation fluctuations much smaller than the beam diameter.

A general expression relating the PCR to the PSD of scattered field fluctuations is obtained in Section 2 without specifying the cause of scattering. Then, the PSD fields are found for obscurations of beamline optics (Section 3), for roughness of beamline optics (Section 4) and for obscurations and roughness of writing optics (Section 5). Section 6 provides an example of calculating the PCR using the obtained formulas and a discussion of the results.

2 General expression for the power contrast ratio

$\mathbb{C}\left(\boldsymbol{t}\right)$

$\mathbb{C}\left(\boldsymbol{t}\right)$

Most lasers use the Treacy compressor[

Reference Treacy

29

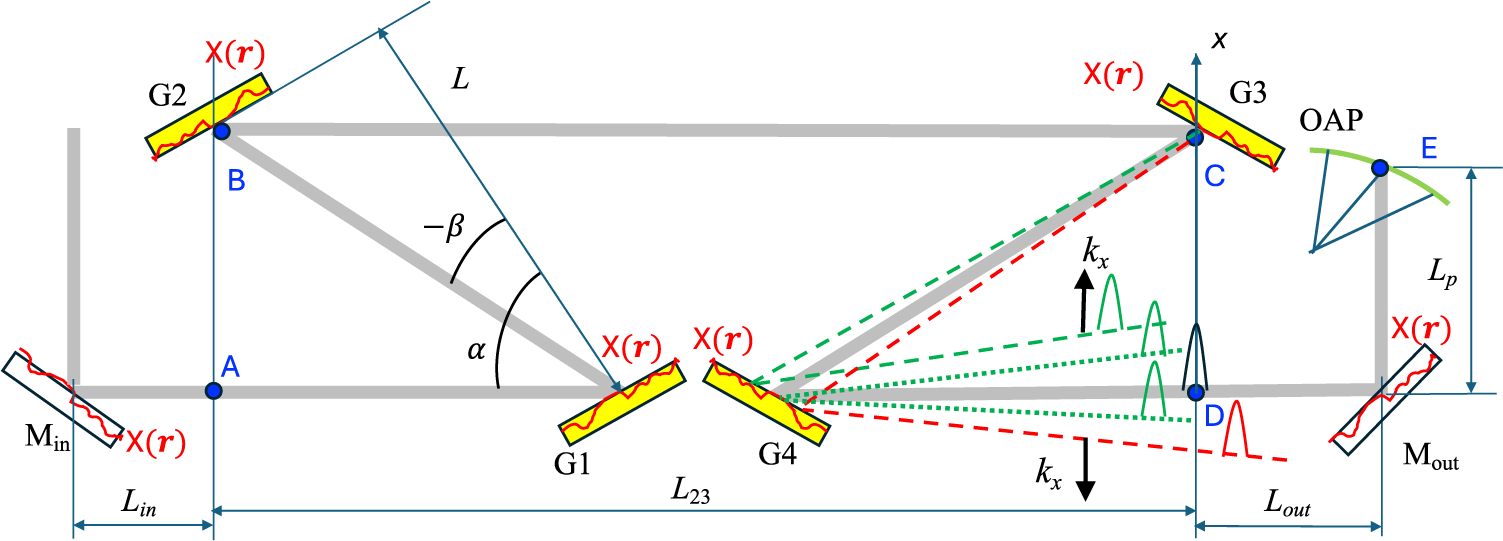

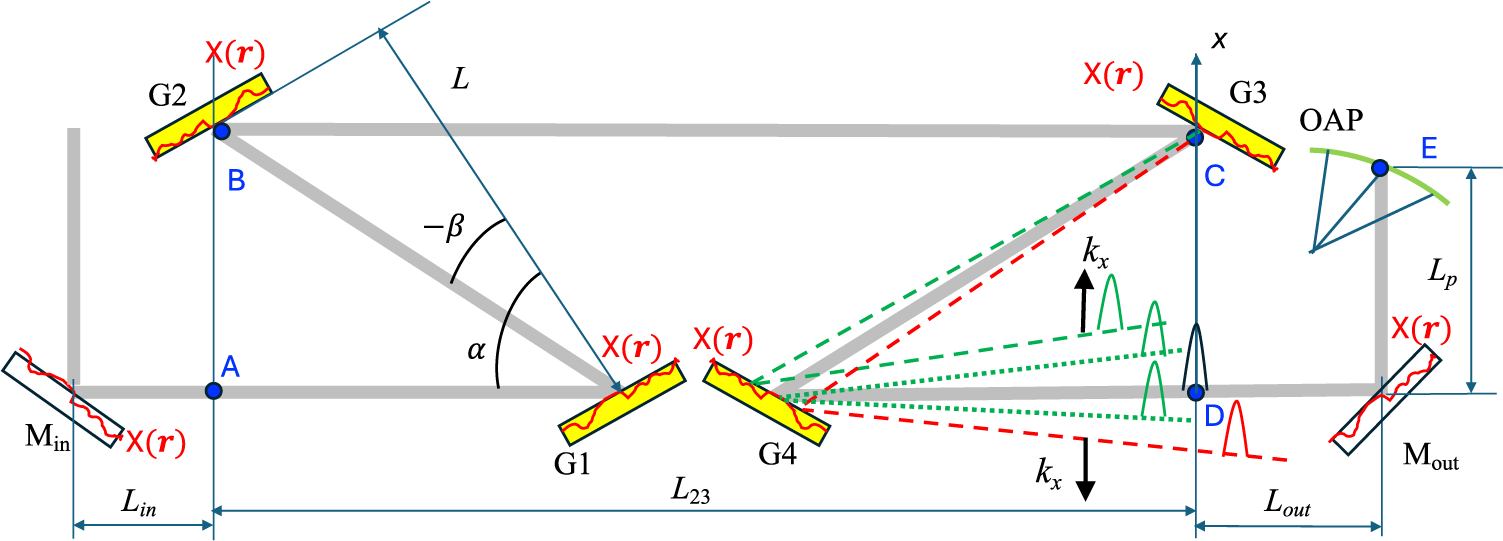

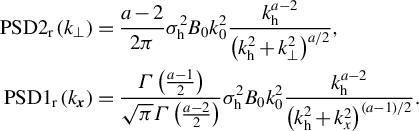

], shown in Figure 1, which has three parameters:

![]() $N$

is the groove density, L is the distance between the gratings along the normal and α is the angle of incidence on the first grating. In the general case of an out-of-plane compressor[

Reference Osvay and Ross

30

], there is one more parameter γ that is the angle of incidence on the first grating in the plane orthogonal to the diffraction plane. The angle of reflection

$N$

is the groove density, L is the distance between the gratings along the normal and α is the angle of incidence on the first grating. In the general case of an out-of-plane compressor[

Reference Osvay and Ross

30

], there is one more parameter γ that is the angle of incidence on the first grating in the plane orthogonal to the diffraction plane. The angle of reflection

![]() $\beta$

for the central frequency

$\beta$

for the central frequency

![]() ${\omega}_0=c{k}_0=2\pi c/{\lambda}_0$

is determined from the expression for the grating

${\omega}_0=c{k}_0=2\pi c/{\lambda}_0$

is determined from the expression for the grating

![]() $\sin\beta =-{\lambda}_0N/ \cos\gamma +\sin \alpha$

. An important special case of an out-of-plane compressor is the Littrow compressor[

Reference Khazanov

31

,

Reference Vyatkin and Khazanov

32

], in which

$\sin\beta =-{\lambda}_0N/ \cos\gamma +\sin \alpha$

. An important special case of an out-of-plane compressor is the Littrow compressor[

Reference Khazanov

31

,

Reference Vyatkin and Khazanov

32

], in which

![]() $\alpha ={\alpha}_\mathrm{L}$

, where

$\alpha ={\alpha}_\mathrm{L}$

, where

![]() ${\alpha}_\mathrm{L}$

is the Littrow angle. It is convenient to start the consideration with the field

${\alpha}_\mathrm{L}$

is the Littrow angle. It is convenient to start the consideration with the field

![]() ${E}_0\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{r}\right)$

(

${E}_0\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{r}\right)$

(

![]() $\Omega =\omega -{\omega}_0$

) incident on an imperfect optical element that may be any diffraction grating G1–G4 and input and output optics Min and Mout, as well as gratings and stretcher mirrors. We will search for the contrast

$\Omega =\omega -{\omega}_0$

) incident on an imperfect optical element that may be any diffraction grating G1–G4 and input and output optics Min and Mout, as well as gratings and stretcher mirrors. We will search for the contrast

![]() $\mathbb{C}(t)$

caused by each element separately, assuming that all other elements are perfect. After reflection, the field takes the following form:

$\mathbb{C}(t)$

caused by each element separately, assuming that all other elements are perfect. After reflection, the field takes the following form:

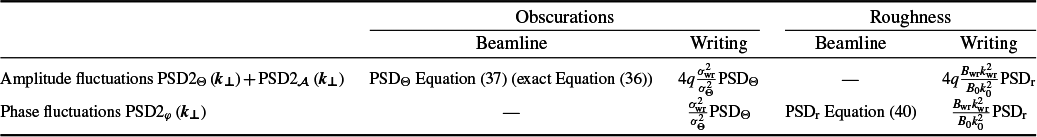

Figure 1 Compressor scheme. G1–G4, diffraction gratings; OAP, off-axis parabola; Min, input optics; Mout, output optics. Dotted lines represent radiation scattered by G4, where scattered pulses lag behind the main one. Dashed lines represent radiation scattered by G3, where scattered pulses lag behind (green) or overtake (red) the main pulse, depending on the sign of

![]() ${k}_x$

.

${k}_x$

.

where

![]() $\mathcal{A}\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)\ll 1$

,

$\mathcal{A}\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)\ll 1$

,

![]() $\varphi \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)\ll 1$

and

$\varphi \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)\ll 1$

and

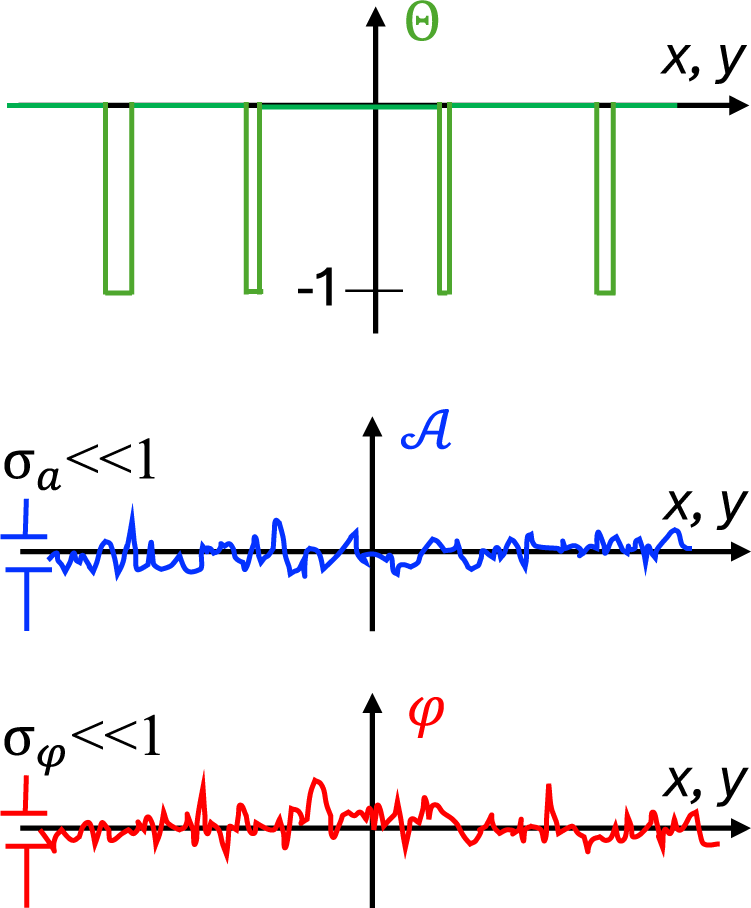

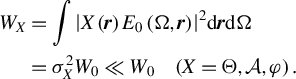

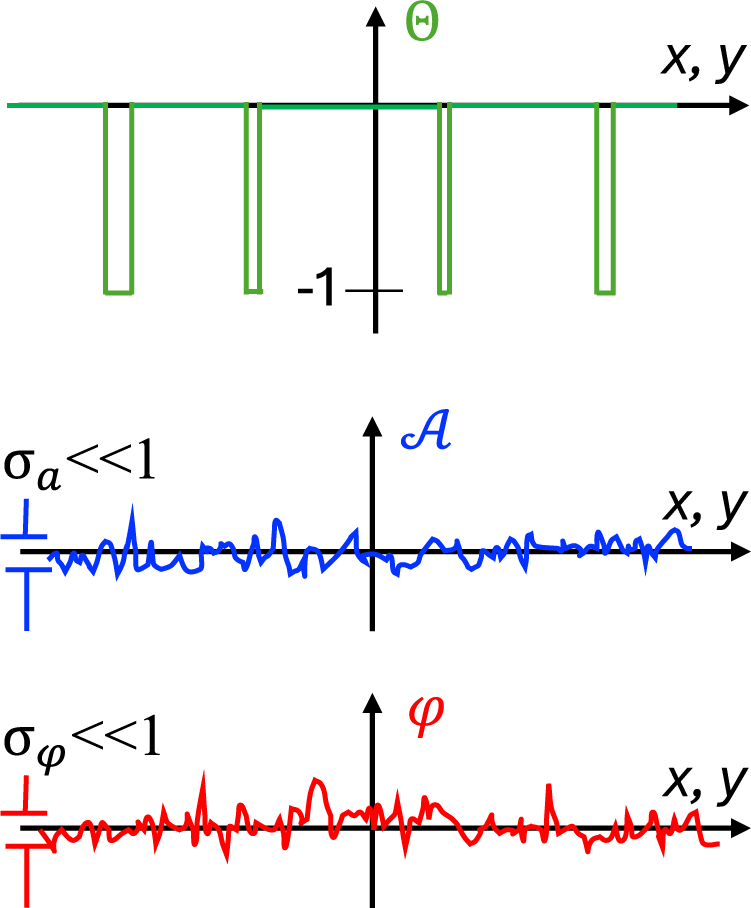

![]() $\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

are real, homogeneous, ergodic random functions (fields) characterizing the fluctuations of the field amplitude and phase, as well as the presence of obscurations:

$\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

are real, homogeneous, ergodic random functions (fields) characterizing the fluctuations of the field amplitude and phase, as well as the presence of obscurations:

![]() $\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)=1$

inside and

$\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)=1$

inside and

![]() $\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)=0$

outside the obscurations. Following Ref. [Reference Spaeth, Manes, Widmayer, Williams, Whitman, Henesian, Stowers and Honig23], we assume that the obscurations ‘absorb’ all incident laser light, and thus they affect only the amplitude of the incident beam and not its phase. The size and coordinates of the obscurations on the surface of the optical element are random variables. The second term in Equation (2) will be further called noise for brevity, and the noise energy will be taken to be much lower than the energy of the main pulse

$\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)=0$

outside the obscurations. Following Ref. [Reference Spaeth, Manes, Widmayer, Williams, Whitman, Henesian, Stowers and Honig23], we assume that the obscurations ‘absorb’ all incident laser light, and thus they affect only the amplitude of the incident beam and not its phase. The size and coordinates of the obscurations on the surface of the optical element are random variables. The second term in Equation (2) will be further called noise for brevity, and the noise energy will be taken to be much lower than the energy of the main pulse

![]() ${W}_0=\int {\left|{E}_0\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{r}\right)\right|}^2\mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{r}\mathrm{d}\Omega$

:

${W}_0=\int {\left|{E}_0\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{r}\right)\right|}^2\mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{r}\mathrm{d}\Omega$

:

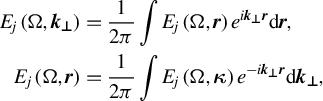

$$\begin{align}{W}_X&=\int {\left|X\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right){E}_0\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{r}\right)\right|}^2\mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{r}\mathrm{d}\Omega\nonumber\\&={\sigma}_X^2{W}_0\ll {W}_0\kern0.84em \left(X=\Theta, \mathcal{A},\varphi \right).\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{W}_X&=\int {\left|X\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right){E}_0\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{r}\right)\right|}^2\mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{r}\mathrm{d}\Omega\nonumber\\&={\sigma}_X^2{W}_0\ll {W}_0\kern0.84em \left(X=\Theta, \mathcal{A},\varphi \right).\end{align}$$

Since in this paper we are interested in small-scale intensity fluctuations, the characteristic spatial scale of

![]() ${E}_0\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

is much larger than the characteristic spatial scale of

${E}_0\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

is much larger than the characteristic spatial scale of

![]() $\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

,

$\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

,

![]() $\mathcal{A}\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

and

$\mathcal{A}\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

and

![]() $\varphi \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

, that is, the correlation length of these functions is much smaller than the beam size. In other words, the spatial spectrum of the noise is much wider than the spectrum of the main beam. From ergodicity it follows that

$\varphi \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

, that is, the correlation length of these functions is much smaller than the beam size. In other words, the spatial spectrum of the noise is much wider than the spectrum of the main beam. From ergodicity it follows that

with

![]() ${\sigma}_{\Theta}^2={S}_\mathrm{ob}/{S}_0$

, where

${\sigma}_{\Theta}^2={S}_\mathrm{ob}/{S}_0$

, where

![]() ${S}_\mathrm{ob}$

is the total area of all obscurations and

${S}_\mathrm{ob}$

is the total area of all obscurations and

![]() ${S}_0$

is the beam area. The angle brackets denote ensemble averaging. For clarity,

${S}_0$

is the beam area. The angle brackets denote ensemble averaging. For clarity,

![]() $\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

,

$\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

,

![]() $\mathcal{A}\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

and

$\mathcal{A}\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

and

![]() $\varphi \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

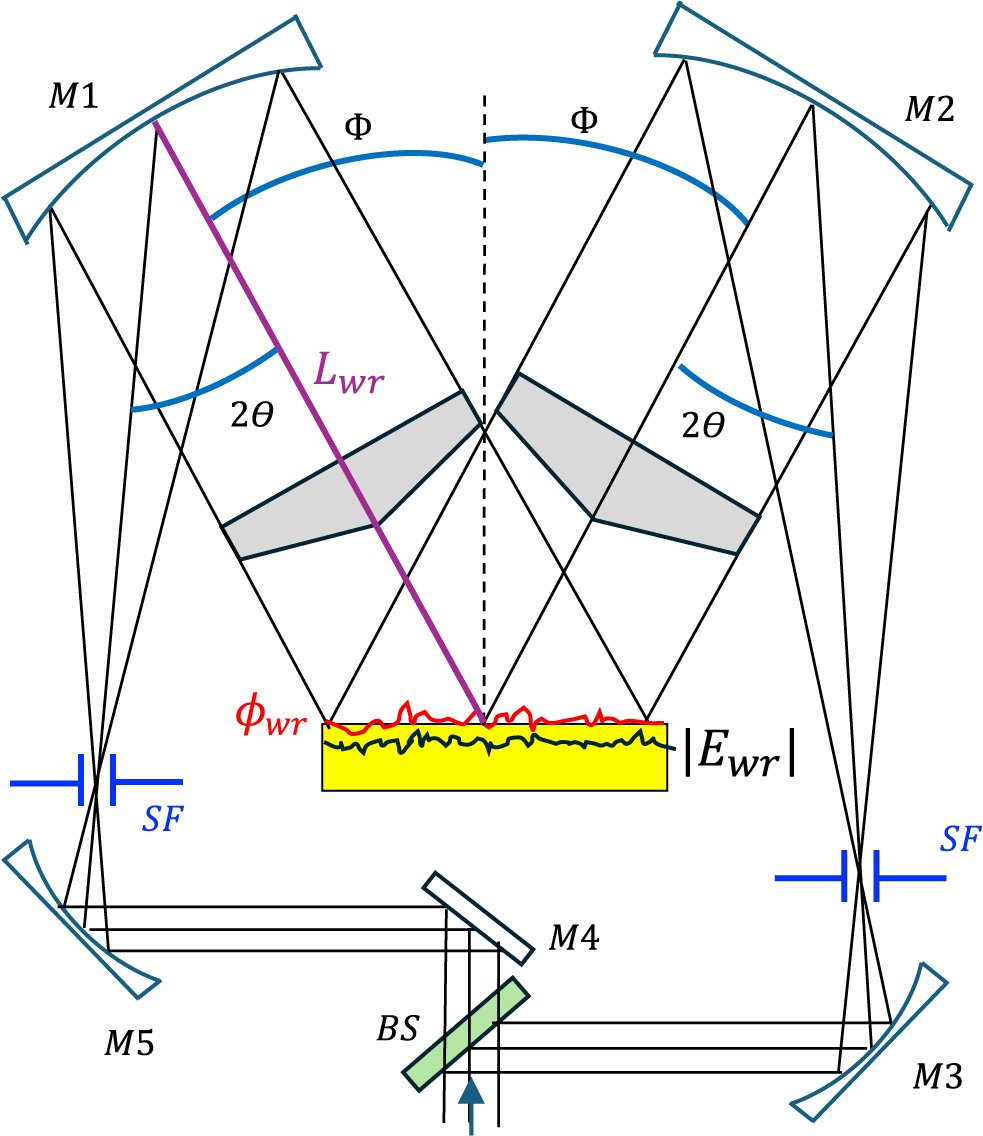

are shown in Figure 2. Equation (2) has the most general form and includes all possible imperfections of the optical element. Note that beam clipping, which also affects the contrast[

Reference Khazanov

33

], is not described by Equation (2) and is outside the scope of this paper. The functions and their Fourier transforms will be designated by the same letters, but with different arguments:

$\varphi \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

are shown in Figure 2. Equation (2) has the most general form and includes all possible imperfections of the optical element. Note that beam clipping, which also affects the contrast[

Reference Khazanov

33

], is not described by Equation (2) and is outside the scope of this paper. The functions and their Fourier transforms will be designated by the same letters, but with different arguments:

$$\begin{align}{E}_j\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{k}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}} \right)&=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int {E}_j\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{r}\right){e}^{i\boldsymbol{k}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}} \boldsymbol{r}}\mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{r},\nonumber\\{E}_j\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{r}\right) &=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int {E}_j\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{\kappa} \right){e}^{-i\boldsymbol{k}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}} \boldsymbol{r}}\mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{k}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}},\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{E}_j\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{k}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}} \right)&=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int {E}_j\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{r}\right){e}^{i\boldsymbol{k}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}} \boldsymbol{r}}\mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{r},\nonumber\\{E}_j\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{r}\right) &=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int {E}_j\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{\kappa} \right){e}^{-i\boldsymbol{k}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}} \boldsymbol{r}}\mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{k}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}},\end{align}$$

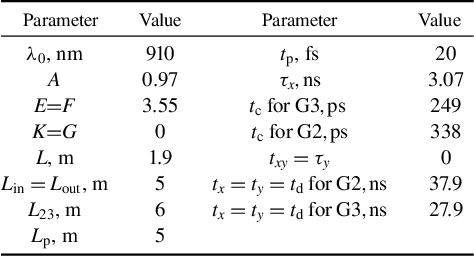

Figure 2 Schematic representation of random functions

![]() $\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right),\ \mathcal{A}\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)\mathrm{and}\;\varphi \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

.

$\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right),\ \mathcal{A}\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)\mathrm{and}\;\varphi \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

.

and analogously for the temporal Fourier transform. Hereinafter, the range of integration, if not otherwise specified, is

![]() $\pm \infty$

. From Equations (2) and (5) we obtain the following:

$\pm \infty$

. From Equations (2) and (5) we obtain the following:

The field on the focusing parabola (point E in Figure 1) up to which the field

![]() ${E}_1\left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

in Equation (6) passes through an optical system containing a pair(s) of parallel gratings and a section(s) of free space of total length

${E}_1\left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

in Equation (6) passes through an optical system containing a pair(s) of parallel gratings and a section(s) of free space of total length

![]() ${L}_\mathrm{f}$

is considered to be the output field

${L}_\mathrm{f}$

is considered to be the output field

![]() ${E}_\mathrm{out}\left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right).$

Regardless of the order in which these elements are passed, the field

${E}_\mathrm{out}\left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right).$

Regardless of the order in which these elements are passed, the field

![]() ${E}_\mathrm{out}\left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

has the following form:

${E}_\mathrm{out}\left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

has the following form:

where

![]() $\Psi \left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

is the sum of the phase

$\Psi \left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

is the sum of the phase

![]() ${\Psi}_\mathrm{f}={L}_\mathrm{f}\sqrt{k_0^2-{k}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}^2}$

introduced by the free space of length

${\Psi}_\mathrm{f}={L}_\mathrm{f}\sqrt{k_0^2-{k}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}^2}$

introduced by the free space of length

![]() ${L}_\mathrm{f}$

and (i) by two pairs of parallel diffraction gratings from point A to point B and from point C to point D for Min or G1; or (ii) by one pair from point C to point D for G2 or G3; or (iii) there are no other terms for G4 or Mout. It is convenient to present the function

${L}_\mathrm{f}$

and (i) by two pairs of parallel diffraction gratings from point A to point B and from point C to point D for Min or G1; or (ii) by one pair from point C to point D for G2 or G3; or (iii) there are no other terms for G4 or Mout. It is convenient to present the function

![]() $\Psi \left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

as a Taylor series at the point

$\Psi \left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

as a Taylor series at the point

![]() $\Omega =0$

,

$\Omega =0$

,

![]() ${k}_x={k}_y=0$

(

${k}_x={k}_y=0$

(

![]() ${k}_{x,y}$

are the components of the vector

${k}_{x,y}$

are the components of the vector

![]() ${\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}$

) by extracting the term of the first power in

${\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}$

) by extracting the term of the first power in

![]() $\Omega$

and designating all the other terms as

$\Omega$

and designating all the other terms as

![]() $\Phi \left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

:

$\Phi \left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

:

The expressions for the phase introduced by the pair of parallel diffraction gratings

![]() ${\Psi}_\mathrm{p}\left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

, as well as for

${\Psi}_\mathrm{p}\left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

, as well as for

![]() ${\psi}_\mathrm{a}^b$

derivatives of

${\psi}_\mathrm{a}^b$

derivatives of

![]() ${\Psi}_\mathrm{p}$

with respect to

${\Psi}_\mathrm{p}$

with respect to

![]() $\omega$

,

$\omega$

,

![]() ${k}_x$

,

${k}_x$

,

![]() ${k}_y$

at the point

${k}_y$

at the point

![]() $\Omega =0$

,

$\Omega =0$

,

![]() ${k}_x={k}_y=0$

, also needed for the Taylor series, can be found in Refs. [Reference Khazanov34,Reference Kocharovskaya, Martyanov and Khazanov35]. Using them, one can obtain the expression for

${k}_x={k}_y=0$

, also needed for the Taylor series, can be found in Refs. [Reference Khazanov34,Reference Kocharovskaya, Martyanov and Khazanov35]. Using them, one can obtain the expression for

![]() $\tau \left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

in the following form:

$\tau \left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

in the following form:

$$\begin{align}\tau \left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)&=2{\tau}_x\frac{k_x}{k_0}+2{\tau}_y\frac{k_y}{k_0}+{t}_x\frac{k_x^2}{k_0^2}+{t}_y\frac{k_y^2}{k_0^2}+2{t}_{xy}\frac{k_x{k}_y}{k_0^2},\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\tau \left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)&=2{\tau}_x\frac{k_x}{k_0}+2{\tau}_y\frac{k_y}{k_0}+{t}_x\frac{k_x^2}{k_0^2}+{t}_y\frac{k_y^2}{k_0^2}+2{t}_{xy}\frac{k_x{k}_y}{k_0^2},\end{align}$$

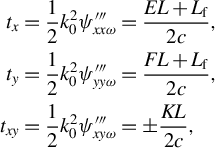

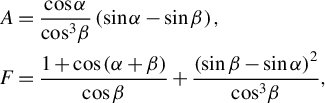

$$\begin{align}{t}_x&=\frac{1}{2}{k}_0^2{\psi}_{xx\omega}^{\prime \prime \prime }=\frac{EL+{L}_\mathrm{f}}{2c},\nonumber\\{t}_y&=\frac{1}{2}{k}_0^2{\psi}_{yy\omega}^{\prime \prime \prime }=\frac{FL+{L}_\mathrm{f}}{2c},\nonumber\\{t}_{xy}&=\frac{1}{2}{k}_0^2{\psi}_{xy\omega}^{\prime \prime \prime }=\pm \frac{KL}{2c},\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{t}_x&=\frac{1}{2}{k}_0^2{\psi}_{xx\omega}^{\prime \prime \prime }=\frac{EL+{L}_\mathrm{f}}{2c},\nonumber\\{t}_y&=\frac{1}{2}{k}_0^2{\psi}_{yy\omega}^{\prime \prime \prime }=\frac{FL+{L}_\mathrm{f}}{2c},\nonumber\\{t}_{xy}&=\frac{1}{2}{k}_0^2{\psi}_{xy\omega}^{\prime \prime \prime }=\pm \frac{KL}{2c},\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}A&=\frac{\cos\alpha}{{\mathit{\cos}}^3\beta}\left( \sin\alpha - \sin\beta \right),\kern0.72em\nonumber\\ F&=\frac{1+\cos \left(\alpha +\beta \right)}{\cos\beta}+\frac{{\left( \sin\beta - \sin\alpha \right)}^2}{{\mathit{\cos}}^3\beta },\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}A&=\frac{\cos\alpha}{{\mathit{\cos}}^3\beta}\left( \sin\alpha - \sin\beta \right),\kern0.72em\nonumber\\ F&=\frac{1+\cos \left(\alpha +\beta \right)}{\cos\beta}+\frac{{\left( \sin\beta - \sin\alpha \right)}^2}{{\mathit{\cos}}^3\beta },\end{align}$$

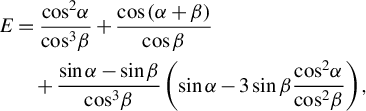

$$\begin{align}E&=\frac{{\mathit{\cos}}^2\alpha }{{\mathit{\cos}}^3\beta }+\frac{\cos \left(\alpha +\beta \right)}{\cos\beta}\nonumber\\&\quad+\frac{\sin\alpha - \sin\beta}{{\mathit{\cos}}^3\beta}\left( \sin\alpha -3 \sin\beta \frac{{\mathit{\cos}}^2\alpha }{{\mathit{\cos}}^2\beta}\right),\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}E&=\frac{{\mathit{\cos}}^2\alpha }{{\mathit{\cos}}^3\beta }+\frac{\cos \left(\alpha +\beta \right)}{\cos\beta}\nonumber\\&\quad+\frac{\sin\alpha - \sin\beta}{{\mathit{\cos}}^3\beta}\left( \sin\alpha -3 \sin\beta \frac{{\mathit{\cos}}^2\alpha }{{\mathit{\cos}}^2\beta}\right),\end{align}$$

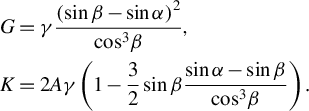

$$\begin{align}G&=\gamma \frac{{\left( \sin\beta - \sin\alpha \right)}^2}{{\mathit{\cos}}^3\beta},\nonumber\\K&=2 A\gamma \left(1-\frac{3}{2} \sin\beta \frac{\sin\alpha - \sin\beta}{{\mathit{\cos}}^3\beta}\right).\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}G&=\gamma \frac{{\left( \sin\beta - \sin\alpha \right)}^2}{{\mathit{\cos}}^3\beta},\nonumber\\K&=2 A\gamma \left(1-\frac{3}{2} \sin\beta \frac{\sin\alpha - \sin\beta}{{\mathit{\cos}}^3\beta}\right).\end{align}$$

As

![]() $\gamma \ll 1$

in the general case, terms of order

$\gamma \ll 1$

in the general case, terms of order

![]() ${\gamma}^2$

are omitted here. From here on we will restrict ourselves to the paraxial approximation, that is, we will consider

${\gamma}^2$

are omitted here. From here on we will restrict ourselves to the paraxial approximation, that is, we will consider

![]() ${k}_{x,y}$

of powers not higher than 2. Thus, we take into account diffraction in the paraxial approximation and all orders of dispersion, including the dispersion of the spatial chirp, since the term

${k}_{x,y}$

of powers not higher than 2. Thus, we take into account diffraction in the paraxial approximation and all orders of dispersion, including the dispersion of the spatial chirp, since the term

![]() $\Phi \left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

includes terms with

$\Phi \left(\Omega, {\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

includes terms with

![]() ${\Omega}^2$

,

${\Omega}^2$

,

![]() ${\Omega}^3$

, etc. Further, we assume that the grating pairs in the compressor are identical. This is not the case for an asymmetric compressor[

Reference Khazanov

34

,

Reference Huang and Kessler

36

–

Reference Liang, Du, Chen, Wang, Liu, Chen, Shena, Liu and Li

42

], but we restrict consideration to a symmetric one. The sign ∓ in Equations (10) and (11) corresponds to the first and second pairs of gratings; therefore, for two pairs of gratings, the total values of

${\Omega}^3$

, etc. Further, we assume that the grating pairs in the compressor are identical. This is not the case for an asymmetric compressor[

Reference Khazanov

34

,

Reference Huang and Kessler

36

–

Reference Liang, Du, Chen, Wang, Liu, Chen, Shena, Liu and Li

42

], but we restrict consideration to a symmetric one. The sign ∓ in Equations (10) and (11) corresponds to the first and second pairs of gratings; therefore, for two pairs of gratings, the total values of

![]() ${t}_{xx}$

,

${t}_{xx}$

,

![]() ${t}_{yy}$

are doubled, and

${t}_{yy}$

are doubled, and

![]() ${\tau}_x={\tau}_y={t}_{xy}=0.$

Note that, if α is equal to the Littrow angle, then

${\tau}_x={\tau}_y={t}_{xy}=0.$

Note that, if α is equal to the Littrow angle, then

![]() $F=E$

. This is not the case for the Treacy compressor, but usually α is chosen as close to the Littrow angle as the decoupling condition allows (the beam incident on grating G1 should not overlap with the second grating). Hence, for the compressor, the values of F and E are close, for example, in the XCELS project[

Reference Khazanov, Shaykin, Kostyukov, Ginzburg, Mukhin, Yakovlev, Soloviev, Kuznetsov, Mironov, Korzhimanov, Bulanov, Shaikin, Kochetkov, Kuzmin, Martyanov, Lozhkarev, Starodubtsev, Litvak and Sergeev

43

]

$F=E$

. This is not the case for the Treacy compressor, but usually α is chosen as close to the Littrow angle as the decoupling condition allows (the beam incident on grating G1 should not overlap with the second grating). Hence, for the compressor, the values of F and E are close, for example, in the XCELS project[

Reference Khazanov, Shaykin, Kostyukov, Ginzburg, Mukhin, Yakovlev, Soloviev, Kuznetsov, Mironov, Korzhimanov, Bulanov, Shaikin, Kochetkov, Kuzmin, Martyanov, Lozhkarev, Starodubtsev, Litvak and Sergeev

43

]

![]() $F=1.025E$

and we can assume that

$F=1.025E$

and we can assume that

![]() ${\tau}_y\approx {\tau}_x$

. This condition is fulfilled exactly for the Littrow compressor[

Reference Khazanov

31

,

Reference Vyatkin and Khazanov

32

].

${\tau}_y\approx {\tau}_x$

. This condition is fulfilled exactly for the Littrow compressor[

Reference Khazanov

31

,

Reference Vyatkin and Khazanov

32

].

The quantity

![]() $\tau \left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

has a simple physical meaning – it is the time delay of the noise component with wave vector

$\tau \left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

has a simple physical meaning – it is the time delay of the noise component with wave vector

![]() ${\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}$

relative to the wave with

${\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}$

relative to the wave with

![]() ${\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}=0$

. Since

${\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}=0$

. Since

![]() $E>0$

and

$E>0$

and

![]() $EF>{K}^2$

, the last three terms in Equation (9) are a positively defined quadratic form, that is, the only negative terms in Equation (9) are the terms with

$EF>{K}^2$

, the last three terms in Equation (9) are a positively defined quadratic form, that is, the only negative terms in Equation (9) are the terms with

![]() ${\tau}_x$

and

${\tau}_x$

and

![]() ${\tau}_y$

. If

${\tau}_y$

. If

![]() ${\tau}_x={\tau}_y=0$

, then all noise components lag behind the main wave, which means that at

${\tau}_x={\tau}_y=0$

, then all noise components lag behind the main wave, which means that at

![]() $t<0$

the contrast is zero (a perfect case). This is true for all optical elements in Figure 1, except for gratings G2 and G3.

$t<0$

the contrast is zero (a perfect case). This is true for all optical elements in Figure 1, except for gratings G2 and G3.

The power

![]() ${P}_\mathrm{out}(t)$

required for calculating

${P}_\mathrm{out}(t)$

required for calculating

![]() $\mathbb{C}(t)$

by the definition in Equation (1) is as follows:

$\mathbb{C}(t)$

by the definition in Equation (1) is as follows:

By substituting Equation (8) into Equation (7) and performing the inverse time Fourier transform we obtain

![]() ${E}_\mathrm{out}\left(t,{\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

. By substituting it into Equation (15) and the result into Equation (1) we find

${E}_\mathrm{out}\left(t,{\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

. By substituting it into Equation (15) and the result into Equation (1) we find

![]() $\mathbb{C}(t)$

. The transformations absolutely analogous to Ref. [Reference Khazanov22] yield the following:

$\mathbb{C}(t)$

. The transformations absolutely analogous to Ref. [Reference Khazanov22] yield the following:

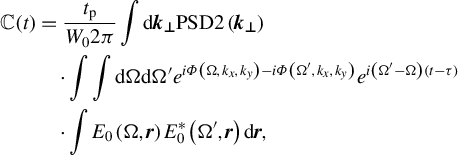

$$\begin{align}\mathbb{C}(t)&=\frac{t_\mathrm{p}}{W_02\pi}\int \mathrm{d}{\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}} \mathrm{PSD2}\left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)\nonumber\\&\quad\cdot\int \int \mathrm{d}\Omega \mathrm{d}\Omega^{\prime }{e}^{i\varPhi \left(\Omega, {k}_x,{k}_y\right)- i\varPhi \left({\Omega}^{\prime}, {k}_x,{k}_y\right)}{e}^{i\left({\Omega}^{\prime }-\Omega \right)\left(t-\tau \right)}\nonumber\\&\quad\cdot\int {E}_0\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{r}\right){E}_0^{\ast}\left(\Omega^{\prime },\boldsymbol{r}\right)\mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{r},\kern0.48em\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\mathbb{C}(t)&=\frac{t_\mathrm{p}}{W_02\pi}\int \mathrm{d}{\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}} \mathrm{PSD2}\left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)\nonumber\\&\quad\cdot\int \int \mathrm{d}\Omega \mathrm{d}\Omega^{\prime }{e}^{i\varPhi \left(\Omega, {k}_x,{k}_y\right)- i\varPhi \left({\Omega}^{\prime}, {k}_x,{k}_y\right)}{e}^{i\left({\Omega}^{\prime }-\Omega \right)\left(t-\tau \right)}\nonumber\\&\quad\cdot\int {E}_0\left(\Omega, \boldsymbol{r}\right){E}_0^{\ast}\left(\Omega^{\prime },\boldsymbol{r}\right)\mathrm{d}\boldsymbol{r},\kern0.48em\end{align}$$

where

![]() ${t}_\mathrm{p}={W}_0/{P}_{0, \mathrm{out}}(0)$

is the duration of the output pulse and

${t}_\mathrm{p}={W}_0/{P}_{0, \mathrm{out}}(0)$

is the duration of the output pulse and

where

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}{2}_X\left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

is the two-dimensional PSD of the function

$\mathrm{PSD}{2}_X\left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

is the two-dimensional PSD of the function

![]() $X$

$X$

![]() $\left(X=\Theta, \mathcal{A},\varphi \right)$

defined by the following:

$\left(X=\Theta, \mathcal{A},\varphi \right)$

defined by the following:

where

![]() $\mathrm{ACF}_X\left(\boldsymbol{\rho} \right)=<X\left(\boldsymbol{r}-\boldsymbol{\rho} \right)X\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)>$

. Here we took into account that

$\mathrm{ACF}_X\left(\boldsymbol{\rho} \right)=<X\left(\boldsymbol{r}-\boldsymbol{\rho} \right)X\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)>$

. Here we took into account that

![]() $\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

,

$\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

,

![]() $\mathcal{A}\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

and

$\mathcal{A}\left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

and

![]() $\varphi \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

are uncorrelated with each other. Note that the noise energy is, evidently,

$\varphi \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)$

are uncorrelated with each other. Note that the noise energy is, evidently,

![]() ${W}_{\mathrm{n}}={P}_{0, \mathrm{out}}(0)\int \mathbb{C}(t) \mathrm{d}t={W}_{\Theta}+{W}_{\mathcal{A}}+{W}_{\varphi }$

. The integration of Equation (16) with respect to

${W}_{\mathrm{n}}={P}_{0, \mathrm{out}}(0)\int \mathbb{C}(t) \mathrm{d}t={W}_{\Theta}+{W}_{\mathcal{A}}+{W}_{\varphi }$

. The integration of Equation (16) with respect to

![]() $t$

gives

$t$

gives

![]() $2\pi \delta \left({\Omega}^{\prime }-\Omega \right)$

, where

$2\pi \delta \left({\Omega}^{\prime }-\Omega \right)$

, where

![]() $\delta$

is the Dirac delta function. Next, taking into account Equation (3) we obtain an obvious relation:

$\delta$

is the Dirac delta function. Next, taking into account Equation (3) we obtain an obvious relation:

The

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}2$

definition in Equation (18) is known in the literature, but it is not the only one. It differs from the definition used, for example, in Refs. [Reference Bromage, Dorrer and Jungquist21,Reference Khazanov22,Reference Martyanov and Khazanov44], where there is no

$\mathrm{PSD}2$

definition in Equation (18) is known in the literature, but it is not the only one. It differs from the definition used, for example, in Refs. [Reference Bromage, Dorrer and Jungquist21,Reference Khazanov22,Reference Martyanov and Khazanov44], where there is no

![]() ${\left(2\pi \right)}^2$

multiplier. We chose that in Equation (18), since in this case Equation (19) for

${\left(2\pi \right)}^2$

multiplier. We chose that in Equation (18), since in this case Equation (19) for

![]() ${\sigma}_X^2$

has a simpler form. In the special case of pure phase distortions

${\sigma}_X^2$

has a simpler form. In the special case of pure phase distortions

![]() $\left(\mathcal{A}=\Theta =0\right),$

Equation (16) coincides with Equation (14) from Ref. [Reference Khazanov22].

$\left(\mathcal{A}=\Theta =0\right),$

Equation (16) coincides with Equation (14) from Ref. [Reference Khazanov22].

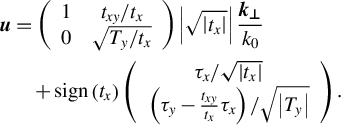

By substituting Equation (11) into Equation (16) we change the variables:

$$\begin{align}\boldsymbol{u}&=\left(\begin{array}{cc}1& {t}_{xy}/{t}_x\\ {}0& \sqrt{T_y/{t}_x}\end{array}\right)\left|\sqrt{\left|{t}_x\right|}\right|\frac{{\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}}{k_0}\nonumber\\&\quad+\mathit{\operatorname{sign}}\left({t}_x\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}{\tau}_x/\sqrt{\left|{t}_x\right|}\\ {}\left({\tau}_y-\frac{t_{xy}}{t_x}{\tau}_x\right)/\sqrt{\left|{T}_y\right|}\end{array}\right).\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\boldsymbol{u}&=\left(\begin{array}{cc}1& {t}_{xy}/{t}_x\\ {}0& \sqrt{T_y/{t}_x}\end{array}\right)\left|\sqrt{\left|{t}_x\right|}\right|\frac{{\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}}{k_0}\nonumber\\&\quad+\mathit{\operatorname{sign}}\left({t}_x\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}{\tau}_x/\sqrt{\left|{t}_x\right|}\\ {}\left({\tau}_y-\frac{t_{xy}}{t_x}{\tau}_x\right)/\sqrt{\left|{T}_y\right|}\end{array}\right).\end{align}$$

Further, supposing that

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}2$

is an isotropic function, that is,

$\mathrm{PSD}2$

is an isotropic function, that is,

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_x,{k}_y\right)= \mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_{\perp}\right)$

and passing from

$\mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_x,{k}_y\right)= \mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_{\perp}\right)$

and passing from

![]() $\left({u}_x,{u}_y\right)$

to the polar coordinates

$\left({u}_x,{u}_y\right)$

to the polar coordinates

![]() $\left(u,\theta \right)$

, we obtain

$\left(u,\theta \right)$

, we obtain

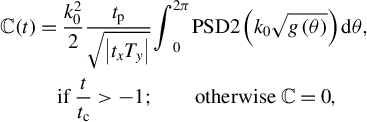

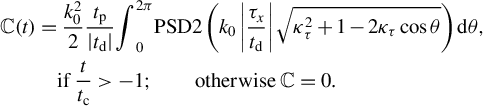

$$\begin{align}\mathbb{C}(t)&=\frac{k_0^2}{2}\frac{t_\mathrm{p}}{\sqrt{\left|{t}_x{T}_y\right|}}{\int}_0^{2\pi } \mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_0\sqrt{g\left(\theta \right)}\right) \mathrm{d}\theta, \nonumber\\&\quad \mathrm{if}\;\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{c}}>-1;\qquad\mathrm{otherwise}\;\mathbb{C}=0,\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\mathbb{C}(t)&=\frac{k_0^2}{2}\frac{t_\mathrm{p}}{\sqrt{\left|{t}_x{T}_y\right|}}{\int}_0^{2\pi } \mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_0\sqrt{g\left(\theta \right)}\right) \mathrm{d}\theta, \nonumber\\&\quad \mathrm{if}\;\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{c}}>-1;\qquad\mathrm{otherwise}\;\mathbb{C}=0,\end{align}$$

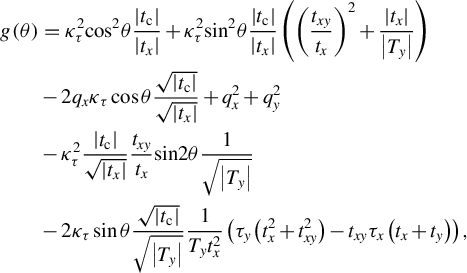

where

$$\begin{align}g\left(\theta \right)&={\kappa}_{\tau}^2{\mathit{\cos}}^2\theta \frac{\left|{t}_\mathrm{c}\right|}{\left|{t}_x\right|}+{\kappa}_{\tau}^2{\mathit{\sin}}^2\theta \frac{\left|{t}_\mathrm{c}\right|}{\left|{t}_x\right|}\left({\left(\frac{t_{xy}}{t_x}\right)}^2+\frac{\left|{t}_x\right|}{\left|{T}_y\right|}\right)\nonumber\\&-2{q}_x{\kappa}_{\tau } \cos\theta \frac{\sqrt{\left|{t}_\mathrm{c}\right|}}{\sqrt{\left|{t}_x\right|}}+{q}_x^2+{q}_y^2\nonumber\\&-{\kappa}_{\tau}^2\frac{\left|{t}_\mathrm{c}\right|}{\sqrt{\left|{t}_x\right|}}\frac{t_{xy}}{t_x}\mathit{\sin}2\theta \frac{1}{\sqrt{\left|{T}_y\right|}}\nonumber\\&-2{\kappa}_{\tau } \sin\theta \frac{\sqrt{\left|{t}_\mathrm{c}\right|}}{\sqrt{\left|{T}_y\right|}}\frac{1}{T_y{t}_x^2}\left({\tau}_y\left({t}_x^2+{t}_{xy}^2\right)-{t}_{xy}{\tau}_x\left({t}_x+{t}_y\right)\right),\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}g\left(\theta \right)&={\kappa}_{\tau}^2{\mathit{\cos}}^2\theta \frac{\left|{t}_\mathrm{c}\right|}{\left|{t}_x\right|}+{\kappa}_{\tau}^2{\mathit{\sin}}^2\theta \frac{\left|{t}_\mathrm{c}\right|}{\left|{t}_x\right|}\left({\left(\frac{t_{xy}}{t_x}\right)}^2+\frac{\left|{t}_x\right|}{\left|{T}_y\right|}\right)\nonumber\\&-2{q}_x{\kappa}_{\tau } \cos\theta \frac{\sqrt{\left|{t}_\mathrm{c}\right|}}{\sqrt{\left|{t}_x\right|}}+{q}_x^2+{q}_y^2\nonumber\\&-{\kappa}_{\tau}^2\frac{\left|{t}_\mathrm{c}\right|}{\sqrt{\left|{t}_x\right|}}\frac{t_{xy}}{t_x}\mathit{\sin}2\theta \frac{1}{\sqrt{\left|{T}_y\right|}}\nonumber\\&-2{\kappa}_{\tau } \sin\theta \frac{\sqrt{\left|{t}_\mathrm{c}\right|}}{\sqrt{\left|{T}_y\right|}}\frac{1}{T_y{t}_x^2}\left({\tau}_y\left({t}_x^2+{t}_{xy}^2\right)-{t}_{xy}{\tau}_x\left({t}_x+{t}_y\right)\right),\end{align}$$

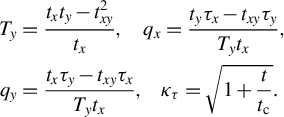

$$\begin{align}{T}_y&=\frac{t_x{t}_y-{t}_{xy}^2}{t_x},\kern0.96em {q}_x=\frac{t_y{\tau}_x-{t}_{xy}{\tau}_y}{T_y{t}_x},\nonumber\\{q}_y&=\frac{t_x{\tau}_y-{t}_{xy}{\tau}_x}{T_y{t}_x},\kern0.84em {\kappa}_{\tau }=\sqrt{1+\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{c}}}.\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{T}_y&=\frac{t_x{t}_y-{t}_{xy}^2}{t_x},\kern0.96em {q}_x=\frac{t_y{\tau}_x-{t}_{xy}{\tau}_y}{T_y{t}_x},\nonumber\\{q}_y&=\frac{t_x{\tau}_y-{t}_{xy}{\tau}_x}{T_y{t}_x},\kern0.84em {\kappa}_{\tau }=\sqrt{1+\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{c}}}.\end{align}$$

Here we restrict consideration to the case

![]() ${t}_x{t}_y>0$

(the diffraction has the same sign along х and у), which is always fulfilled for the compressor, but not always for the stretcher[

Reference Khazanov

22

], and take into account that

${t}_x{t}_y>0$

(the diffraction has the same sign along х and у), which is always fulfilled for the compressor, but not always for the stretcher[

Reference Khazanov

22

], and take into account that

![]() ${t}_x{t}_y-{t}_{xy}^2>0$

(i.e.,

${t}_x{t}_y-{t}_{xy}^2>0$

(i.e.,

![]() ${T}_y$

has the same sign as

${T}_y$

has the same sign as

![]() ${t}_x$

). Note that only

${t}_x$

). Note that only

![]() ${\kappa}_{\tau }$

is time dependent.

${\kappa}_{\tau }$

is time dependent.

Next, we take into account that

![]() $\gamma \ll 1$

and, consequently,

$\gamma \ll 1$

and, consequently,

![]() $\frac{t_{xy}}{t_x}\sim \gamma \ll 1$

and

$\frac{t_{xy}}{t_x}\sim \gamma \ll 1$

and

![]() $\frac{\tau_y}{t_x}\sim \gamma \ll 1$

. By expanding

$\frac{\tau_y}{t_x}\sim \gamma \ll 1$

. By expanding

![]() $\mathbb{C}\left(t,\gamma \right)$

in a Taylor series near the point

$\mathbb{C}\left(t,\gamma \right)$

in a Taylor series near the point

![]() $\gamma =0$

it is easy to show that the term proportional to

$\gamma =0$

it is easy to show that the term proportional to

![]() $\gamma$

vanishes. Consequently, the difference in the contrast

$\gamma$

vanishes. Consequently, the difference in the contrast

![]() $\mathbb{C}\left(t,\gamma \right)$

for an out-of-plane compressor from the contrast

$\mathbb{C}\left(t,\gamma \right)$

for an out-of-plane compressor from the contrast

![]() $\mathbb{C}\left(t,\gamma =0\right)$

for a plane compressor reduces to corrections of the order of

$\mathbb{C}\left(t,\gamma =0\right)$

for a plane compressor reduces to corrections of the order of

![]() ${\gamma}^2$

. For typical values of

${\gamma}^2$

. For typical values of

![]() $\gamma =10,\dots, 15$

degrees, the correction will be about 5%, which is negligibly small for contrast. Thus, PCR

$\gamma =10,\dots, 15$

degrees, the correction will be about 5%, which is negligibly small for contrast. Thus, PCR

![]() $\mathbb{C}(t)$

does not depend on γ and we can use the expressions for a plane compressor. In other words, the contrast of an out-of-plane compressor practically does not differ from the contrast of a plane one. At

$\mathbb{C}(t)$

does not depend on γ and we can use the expressions for a plane compressor. In other words, the contrast of an out-of-plane compressor practically does not differ from the contrast of a plane one. At

![]() $\gamma =0,$

Equation (21) strictly passes into Equation (19) from Ref. [Reference Khazanov22] (taking into consideration that the definition of

$\gamma =0,$

Equation (21) strictly passes into Equation (19) from Ref. [Reference Khazanov22] (taking into consideration that the definition of

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}2$

in Ref. [Reference Khazanov22] differs from Equation (18) by the multiplier

$\mathrm{PSD}2$

in Ref. [Reference Khazanov22] differs from Equation (18) by the multiplier

![]() ${\left(2\pi \right)}^2$

). Therefore, the results obtained in Ref. [Reference Khazanov22] for phase noise are valid in the general case if

${\left(2\pi \right)}^2$

). Therefore, the results obtained in Ref. [Reference Khazanov22] for phase noise are valid in the general case if

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\varphi}\left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

is replaced by

$\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\varphi}\left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

is replaced by

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}2\left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

in Equation (17). In particular, if we take into account that

$\mathrm{PSD}2\left({\boldsymbol{k}}_{\boldsymbol{\perp}}\right)$

in Equation (17). In particular, if we take into account that

![]() ${t}_x\approx {t}_y={t}_\mathrm{d}$

, then Equation (21) takes the following form:

${t}_x\approx {t}_y={t}_\mathrm{d}$

, then Equation (21) takes the following form:

$$\begin{align}\mathbb{C}(t)&=\frac{k_0^2}{2}\frac{t_\mathrm{p}}{\left|{t}_\mathrm{d}\right|}{\int}_0^{2\pi } \mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_0\left|\frac{\tau_x}{t_\mathrm{d}}\right|\sqrt{\kappa_{\tau}^2+1-2{\kappa}_{\tau } \cos\theta}\right) \mathrm{d}\theta,\nonumber\\&\quad \mathrm{if}\;\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{c}}>-1;\qquad\mathrm{otherwise}\;\mathbb{C}=0.\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\mathbb{C}(t)&=\frac{k_0^2}{2}\frac{t_\mathrm{p}}{\left|{t}_\mathrm{d}\right|}{\int}_0^{2\pi } \mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_0\left|\frac{\tau_x}{t_\mathrm{d}}\right|\sqrt{\kappa_{\tau}^2+1-2{\kappa}_{\tau } \cos\theta}\right) \mathrm{d}\theta,\nonumber\\&\quad \mathrm{if}\;\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{c}}>-1;\qquad\mathrm{otherwise}\;\mathbb{C}=0.\end{align}$$

This expression is significantly simplified in two important particular cases. Firstly, for G2 and G3 gratings, the allowance for diffraction

![]() $\left({t}_\mathrm{d}\ne 0\right)$

leads to the emergence of the cut-off time

$\left({t}_\mathrm{d}\ne 0\right)$

leads to the emergence of the cut-off time

![]() ${t}_\mathrm{c}$

and to a slight contrast asymmetry, which can be neglected, then

${t}_\mathrm{c}$

and to a slight contrast asymmetry, which can be neglected, then

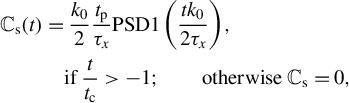

$$\begin{align}{\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{s}(t)&=\frac{k_0}{2}\frac{t_\mathrm{p}}{\tau_x} \mathrm{PSD}1\left(\frac{t{k}_0}{2{\tau}_x}\right),\nonumber\\& \quad \mathrm{if}\;\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{c}}>-1; \qquad \mathrm{otherwise}\;{\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{s}=0,\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{s}(t)&=\frac{k_0}{2}\frac{t_\mathrm{p}}{\tau_x} \mathrm{PSD}1\left(\frac{t{k}_0}{2{\tau}_x}\right),\nonumber\\& \quad \mathrm{if}\;\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{c}}>-1; \qquad \mathrm{otherwise}\;{\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{s}=0,\end{align}$$

where

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}1\left({k}_x\right)$

is a one-dimensional PSD function related to

$\mathrm{PSD}1\left({k}_x\right)$

is a one-dimensional PSD function related to

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_{\perp}\right)$

as follows[

Reference Khazanov, Kochetkov and Silin

45

]:

$\mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_{\perp}\right)$

as follows[

Reference Khazanov, Kochetkov and Silin

45

]:

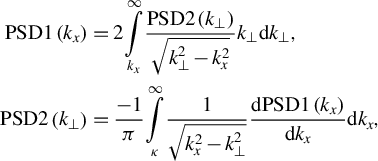

$$\begin{align}\mathrm{PSD}1\left({k}_x\right)&=2\underset{k_x}{\overset{\infty }{\int }}\frac{\mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_{\perp}\right)}{\sqrt{k_{\perp}^2-{k}_x^2}}{k}_{\perp }\mathrm{d}{k}_{\perp},\nonumber\\\mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_{\perp}\right)&=\frac{-1}{\pi}\underset{\kappa }{\overset{\infty }{\int }}\frac{1}{\sqrt{k_x^2-{k}_{\perp}^2}}\frac{\mathrm{d}\mathrm{PSD}1\left({k}_x\right)}{\mathrm{d}{k}_x}\mathrm{d}{k}_x,\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\mathrm{PSD}1\left({k}_x\right)&=2\underset{k_x}{\overset{\infty }{\int }}\frac{\mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_{\perp}\right)}{\sqrt{k_{\perp}^2-{k}_x^2}}{k}_{\perp }\mathrm{d}{k}_{\perp},\nonumber\\\mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_{\perp}\right)&=\frac{-1}{\pi}\underset{\kappa }{\overset{\infty }{\int }}\frac{1}{\sqrt{k_x^2-{k}_{\perp}^2}}\frac{\mathrm{d}\mathrm{PSD}1\left({k}_x\right)}{\mathrm{d}{k}_x}\mathrm{d}{k}_x,\end{align}$$

with

Secondly, there is no space chirp

![]() ${\tau}_x={\tau}_y=0$

for all optical elements in Figure 1, except for gratings G2 and G3; for them, the contrast

${\tau}_x={\tau}_y=0$

for all optical elements in Figure 1, except for gratings G2 and G3; for them, the contrast

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}(t)$

is determined only by the diffraction:

${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}(t)$

is determined only by the diffraction:

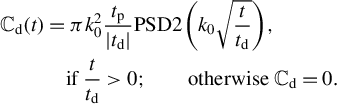

$$\begin{align}{\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}(t)&=\pi {k}_0^2\frac{t_\mathrm{p}}{\left|{t}_\mathrm{d}\right|} \mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_0\sqrt{\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{d}}}\right),\kern0.24em \nonumber\\& \quad \mathrm{if}\;\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{d}}>0;\qquad \mathrm{otherwise}\;{\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}=0.\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}(t)&=\pi {k}_0^2\frac{t_\mathrm{p}}{\left|{t}_\mathrm{d}\right|} \mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_0\sqrt{\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{d}}}\right),\kern0.24em \nonumber\\& \quad \mathrm{if}\;\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{d}}>0;\qquad \mathrm{otherwise}\;{\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}=0.\end{align}$$

If

![]() ${t}_\mathrm{d}>0$

, then

${t}_\mathrm{d}>0$

, then

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}\left(t<0\right)=0$

, which explains the frequently observed[

Reference Webb, Dorrer, Bahk, Jeon, Roides and Bromage

5

,

Reference Hooker, Tang, Chekhlov, Collier, Divall, Ertel, Hawkes, Parry and Rajeev

15

–

Reference Lu, Zhang, Li and Leng

18

,

Reference Wang, Liu, Lu, Chen, Long, Li, Chen, Chen, Bai, Li, Peng, Liu, Wu, Wang, Li, Xu, Liang, Leng and Li

46

,

Reference Khodakovskiy, Kalashnikov, Gontier, Falcoz and Paul

47

] experimental asymmetry of the contrast: at

${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}\left(t<0\right)=0$

, which explains the frequently observed[

Reference Webb, Dorrer, Bahk, Jeon, Roides and Bromage

5

,

Reference Hooker, Tang, Chekhlov, Collier, Divall, Ertel, Hawkes, Parry and Rajeev

15

–

Reference Lu, Zhang, Li and Leng

18

,

Reference Wang, Liu, Lu, Chen, Long, Li, Chen, Chen, Bai, Li, Peng, Liu, Wu, Wang, Li, Xu, Liang, Leng and Li

46

,

Reference Khodakovskiy, Kalashnikov, Gontier, Falcoz and Paul

47

] experimental asymmetry of the contrast: at

![]() $t<0$

(pre-pulse) it is always weaker (better) than at

$t<0$

(pre-pulse) it is always weaker (better) than at

![]() $t>0$

(post-pulse), since all optical elements contribute to the contrast at

$t>0$

(post-pulse), since all optical elements contribute to the contrast at

![]() $t>0$

, while only gratings G2 and G3 contribute to it at both

$t>0$

, while only gratings G2 and G3 contribute to it at both

![]() $t<0$

and

$t<0$

and

![]() $t>0$

. In Ref. [Reference Khodakovskiy, Kalashnikov, Gontier, Falcoz and Paul47] the authors experimentally proved that the contrast asymmetry cannot be explained by amplified spontaneous emission , the Raman effect, Kerr-lens mode-locking or Kerr nonlinearity in Ti:sapphire amplifiers. The hypothesis[

Reference Khodakovskiy, Kalashnikov, Gontier, Falcoz and Paul

47

] that phonons play a key role as Ti:sapphire lasers are vibronic contradicts recent experiments[

Reference Webb, Dorrer, Bahk, Jeon, Roides and Bromage

5

,

Reference Wang, Liu, Lu, Chen, Long, Li, Chen, Chen, Bai, Li, Peng, Liu, Wu, Wang, Li, Xu, Liang, Leng and Li

46

] with a fully OPCPA laser where the contrast asymmetry was measured. The measured post-pulse in Ref. [Reference Khodakovskiy, Kalashnikov, Gontier, Falcoz and Paul47] did not depend on the stretching factor or on the dispersive elements (gratings or prisms), and the authors concluded that scattering on the diffraction gratings also has no impact on asymmetry of the contrast. As seen from Refs. [Reference Bonod and Neauport26,Reference Treacy29], it is true only for the scattering on the second and third gratings, but not for the scattering on all other optics, including optics in the contrast measurement beamline. Thus, this scattering is the only way to explain the contrast asymmetry. Note that it cannot be explained by the earlier developed[

Reference Roeder, Zobus, Brabetz and Bagnoud

19

–

Reference Bromage, Dorrer and Jungquist

21

] diffraction-free approximation, in which

$t>0$

. In Ref. [Reference Khodakovskiy, Kalashnikov, Gontier, Falcoz and Paul47] the authors experimentally proved that the contrast asymmetry cannot be explained by amplified spontaneous emission , the Raman effect, Kerr-lens mode-locking or Kerr nonlinearity in Ti:sapphire amplifiers. The hypothesis[

Reference Khodakovskiy, Kalashnikov, Gontier, Falcoz and Paul

47

] that phonons play a key role as Ti:sapphire lasers are vibronic contradicts recent experiments[

Reference Webb, Dorrer, Bahk, Jeon, Roides and Bromage

5

,

Reference Wang, Liu, Lu, Chen, Long, Li, Chen, Chen, Bai, Li, Peng, Liu, Wu, Wang, Li, Xu, Liang, Leng and Li

46

] with a fully OPCPA laser where the contrast asymmetry was measured. The measured post-pulse in Ref. [Reference Khodakovskiy, Kalashnikov, Gontier, Falcoz and Paul47] did not depend on the stretching factor or on the dispersive elements (gratings or prisms), and the authors concluded that scattering on the diffraction gratings also has no impact on asymmetry of the contrast. As seen from Refs. [Reference Bonod and Neauport26,Reference Treacy29], it is true only for the scattering on the second and third gratings, but not for the scattering on all other optics, including optics in the contrast measurement beamline. Thus, this scattering is the only way to explain the contrast asymmetry. Note that it cannot be explained by the earlier developed[

Reference Roeder, Zobus, Brabetz and Bagnoud

19

–

Reference Bromage, Dorrer and Jungquist

21

] diffraction-free approximation, in which

![]() $\mathbb{C}(t)$

is an even function.

$\mathbb{C}(t)$

is an even function.

In the case of negative diffraction

![]() $({t}_\mathrm{d}<0)$

, the time t changes its sign to the opposite one and the contrast

$({t}_\mathrm{d}<0)$

, the time t changes its sign to the opposite one and the contrast

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}(t)$

is nonzero at negative times. This is possible if the scheme comprises a telescope transferring the image of the optical element beyond the focusing parabola. In addition, the contrast meter is usually located not directly in the powerful beam, but rather in its weakened replica. The meter also receives the radiation scattered throughout the optics located in the measuring path. Its contribution to the PCR is also described by Equation (29), where

${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}(t)$

is nonzero at negative times. This is possible if the scheme comprises a telescope transferring the image of the optical element beyond the focusing parabola. In addition, the contrast meter is usually located not directly in the powerful beam, but rather in its weakened replica. The meter also receives the radiation scattered throughout the optics located in the measuring path. Its contribution to the PCR is also described by Equation (29), where

![]() ${t}_\mathrm{d}={L}_\mathrm{m}/2c$

and

${t}_\mathrm{d}={L}_\mathrm{m}/2c$

and

![]() ${L}_\mathrm{m}$

is the distance from the optical element in the path to the meter. If

${L}_\mathrm{m}$

is the distance from the optical element in the path to the meter. If

![]() ${L}_\mathrm{m}>0$

, then the measured contrast will be higher than the real one at

${L}_\mathrm{m}>0$

, then the measured contrast will be higher than the real one at

![]() $t>0$

. However, if there is an image transfer in the path, then

$t>0$

. However, if there is an image transfer in the path, then

![]() ${L}_\mathrm{m}$

may be less than zero, and the contrast measured will be higher than the real one at less than

${L}_\mathrm{m}$

may be less than zero, and the contrast measured will be higher than the real one at less than

![]() $0$

; see Equation (29).

$0$

; see Equation (29).

Equations (26) and (29) clearly show the

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}1\left({k}_x\right)$

mapping on

$\mathrm{PSD}1\left({k}_x\right)$

mapping on

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{s}(t)$

and

${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{s}(t)$

and

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_{\perp}\right)$

on

$\mathrm{PSD}2\left({k}_{\perp}\right)$

on

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}(t)$

, with

${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}(t)$

, with

![]() ${k}_x=\frac{t{k}_0}{2{\tau}_x}$

in the first case and

${k}_x=\frac{t{k}_0}{2{\tau}_x}$

in the first case and

${k}_{\perp }={k}_0\sqrt{\left|\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{d}}\right|}$

in the second case. Correspondingly, the condition of paraxial approximation

${k}_{\perp }={k}_0\sqrt{\left|\frac{t}{t_\mathrm{d}}\right|}$

in the second case. Correspondingly, the condition of paraxial approximation

![]() ${k}_{x,\perp}\ll {k}_0$

constrains the obtained results to the conditions

${k}_{x,\perp}\ll {k}_0$

constrains the obtained results to the conditions

![]() $\left|t\right|\ll 2\left|{\tau}_x\right|$

for

$\left|t\right|\ll 2\left|{\tau}_x\right|$

for

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{s}(t)$

and

${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{s}(t)$

and

![]() $\sqrt{\left|t\right|}\ll \sqrt{\left|{t}_\mathrm{d}\right|}$

for

$\sqrt{\left|t\right|}\ll \sqrt{\left|{t}_\mathrm{d}\right|}$

for

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}(t)$

. Further investigation of

${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}(t)$

. Further investigation of

![]() $\mathbb{C}(t)$

, including quantitative comparison with

$\mathbb{C}(t)$

, including quantitative comparison with

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}(t)$

and

${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{d}(t)$

and

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{s}(t)$

, is possible only for the functional forms

${\mathbb{C}}_\mathrm{s}(t)$

, is possible only for the functional forms

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}, \mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\mathcal{A}}\kern0.36em \mathrm{and}\ \mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\varphi}$

.

$\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}, \mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\mathcal{A}}\kern0.36em \mathrm{and}\ \mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\varphi}$

.

3 Power spectral density functional form PSD2 for obscurations on the grating/mirror surface

To find

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)$

for the field reflected from a surface with obscuration, we assume that the obscurations do not overlap each other and are shaped as a circle with coordinates of the centre

$\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)$

for the field reflected from a surface with obscuration, we assume that the obscurations do not overlap each other and are shaped as a circle with coordinates of the centre

![]() ${\boldsymbol{R}}_{m}$

and radius

${\boldsymbol{R}}_{m}$

and radius

![]() ${w}_{m}$

:

${w}_{m}$

:

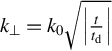

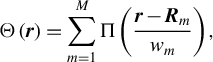

$$\begin{align}\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)=\sum \limits_{m=1}^M\Pi \left(\frac{\boldsymbol{r}-{\boldsymbol{R}}_{m}}{w_{m}}\right),\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\Theta \left(\boldsymbol{r}\right)=\sum \limits_{m=1}^M\Pi \left(\frac{\boldsymbol{r}-{\boldsymbol{R}}_{m}}{w_{m}}\right),\end{align}$$

where

![]() $\Pi (x)=1\;\mathrm{if}\;\left|x\right|<1,\mathrm{otherwise}\;\Pi =0$

, and

$\Pi (x)=1\;\mathrm{if}\;\left|x\right|<1,\mathrm{otherwise}\;\Pi =0$

, and

![]() $M\gg 1$

is the number of obscurations. Here,

$M\gg 1$

is the number of obscurations. Here,

![]() ${\boldsymbol{R}}_m$

and

${\boldsymbol{R}}_m$

and

![]() ${w}_m$

are random quantities, with

${w}_m$

are random quantities, with

![]() ${\boldsymbol{R}}_m$

being uniformly distributed over the beam aperture and

${\boldsymbol{R}}_m$

being uniformly distributed over the beam aperture and

![]() ${w}_m$

having a probability density

${w}_m$

having a probability density

![]() $f(w)$

. It is obvious that

$f(w)$

. It is obvious that

![]() ${S}_\mathrm{ob}=\pi \sum_{m=1}^M{R}_{m}^2$

. The squared modulus of the noise spectrum

${S}_\mathrm{ob}=\pi \sum_{m=1}^M{R}_{m}^2$

. The squared modulus of the noise spectrum

![]() ${S}_{\Theta}$

is an incoherent sum of the squared moduli of the spectra

${S}_{\Theta}$

is an incoherent sum of the squared moduli of the spectra

![]() ${S}_m$

of flat-top beams having radius

${S}_m$

of flat-top beams having radius

![]() ${w}_m$

(Airy functions):

${w}_m$

(Airy functions):

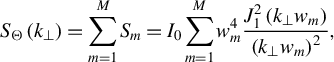

$$\begin{align}{S}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)=\sum \limits_{m=1}^M{S}_{m}={I}_0\sum \limits_{m=1}^M{w}_{m}^4\frac{J_1^2\left({k}_{\perp }{w}_{m}\right)}{{\left({k}_{\perp }{w}_{m}\right)}^2},\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{S}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)=\sum \limits_{m=1}^M{S}_{m}={I}_0\sum \limits_{m=1}^M{w}_{m}^4\frac{J_1^2\left({k}_{\perp }{w}_{m}\right)}{{\left({k}_{\perp }{w}_{m}\right)}^2},\end{align}$$

where

![]() ${J}_1$

is the Bessel function and

${J}_1$

is the Bessel function and

![]() ${I}_0={\left|{E}_0\right|}^2$

is the incident beam intensity assumed for simplicity to be equal for all obscurations. Here we sum the spectra incoherently, since the spectral phase of each obscuration is random and the sum of a large number of terms with random phase is zero. As a consequence,

${I}_0={\left|{E}_0\right|}^2$

is the incident beam intensity assumed for simplicity to be equal for all obscurations. Here we sum the spectra incoherently, since the spectral phase of each obscuration is random and the sum of a large number of terms with random phase is zero. As a consequence,

![]() ${S}_{\Theta}$

does not depend on

${S}_{\Theta}$

does not depend on

![]() ${\boldsymbol{R}}_{m}$

. From the definition of PSD2 in Equation (18) and of the Fourier spectrum in Equation (5), with allowance for ergodicity we obtain

${\boldsymbol{R}}_{m}$

. From the definition of PSD2 in Equation (18) and of the Fourier spectrum in Equation (5), with allowance for ergodicity we obtain

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)=\frac{<{S}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)>}{I_0{S}_0}$

. By averaging Equation (31) we find the following:

$\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)=\frac{<{S}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)>}{I_0{S}_0}$

. By averaging Equation (31) we find the following:

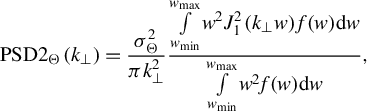

$$\begin{align}\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)=\frac{\sigma_{\Theta}^2}{\pi {k}_{\perp}^2}\frac{\underset{{w}_\mathrm{min}}{\overset{{w}_\mathrm{max}}{\int }}{w}^2{J}_1^2\left({k}_{\perp }w\right)f(w) \mathrm{d}w}{\underset{w_\mathrm{min}}{\overset{w_\mathrm{max}}{\int }}{w}^2f(w) \mathrm{d}w},\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)=\frac{\sigma_{\Theta}^2}{\pi {k}_{\perp}^2}\frac{\underset{{w}_\mathrm{min}}{\overset{{w}_\mathrm{max}}{\int }}{w}^2{J}_1^2\left({k}_{\perp }w\right)f(w) \mathrm{d}w}{\underset{w_\mathrm{min}}{\overset{w_\mathrm{max}}{\int }}{w}^2f(w) \mathrm{d}w},\end{align}$$

which, with Equation (27) taken into account, follows

$$\begin{align}\mathrm{PSD}{1}_{\Theta}\left({k}_x\right)=\frac{\sigma_{\Theta}^2}{\pi {k}_x^2}\frac{\underset{{w}_\mathrm{min}}{\overset{{w}_\mathrm{max}}{\int }} wf(w){\boldsymbol{H}}_{1}\left(2w{k}_x\right) \mathrm{d}w}{\underset{w_\mathrm{min}}{\overset{w_\mathrm{max}}{\int }}{w}^2f(w) \mathrm{d}w},\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\mathrm{PSD}{1}_{\Theta}\left({k}_x\right)=\frac{\sigma_{\Theta}^2}{\pi {k}_x^2}\frac{\underset{{w}_\mathrm{min}}{\overset{{w}_\mathrm{max}}{\int }} wf(w){\boldsymbol{H}}_{1}\left(2w{k}_x\right) \mathrm{d}w}{\underset{w_\mathrm{min}}{\overset{w_\mathrm{max}}{\int }}{w}^2f(w) \mathrm{d}w},\end{align}$$

where

![]() ${\boldsymbol{H}}_{1}$

is the Struve function and

${\boldsymbol{H}}_{1}$

is the Struve function and

![]() ${w}_{\mathit{\min},\mathit{\max}}$

are the minimum and maximum radii of the obscurations. Obviously,

${w}_{\mathit{\min},\mathit{\max}}$

are the minimum and maximum radii of the obscurations. Obviously,

![]() $2{w}_\mathrm{min}\gg {\lambda}_0$

, since the paraxial approximation does not hold otherwise. Similarly, the obscurations with radius

$2{w}_\mathrm{min}\gg {\lambda}_0$

, since the paraxial approximation does not hold otherwise. Similarly, the obscurations with radius

![]() $w$

commensurate with the beam radius

$w$

commensurate with the beam radius

![]() ${R}_0$

cannot exist, since in this case the condition

${R}_0$

cannot exist, since in this case the condition

![]() ${W}_{\Theta}\ll {W}_0$

is violated. This imposes the constraint

${W}_{\Theta}\ll {W}_0$

is violated. This imposes the constraint

![]() ${w}_\mathrm{max}\ll {R}_0$

. In practice, the quantities

${w}_\mathrm{max}\ll {R}_0$

. In practice, the quantities

![]() ${w}_{\mathit{\min},\mathit{\max}}$

may have even more stringent constraints. Note that Equations (32) and (33) satisfy Equations (19) and (28) regardless of the form of the function

${w}_{\mathit{\min},\mathit{\max}}$

may have even more stringent constraints. Note that Equations (32) and (33) satisfy Equations (19) and (28) regardless of the form of the function

![]() $f(w)$

.

$f(w)$

.

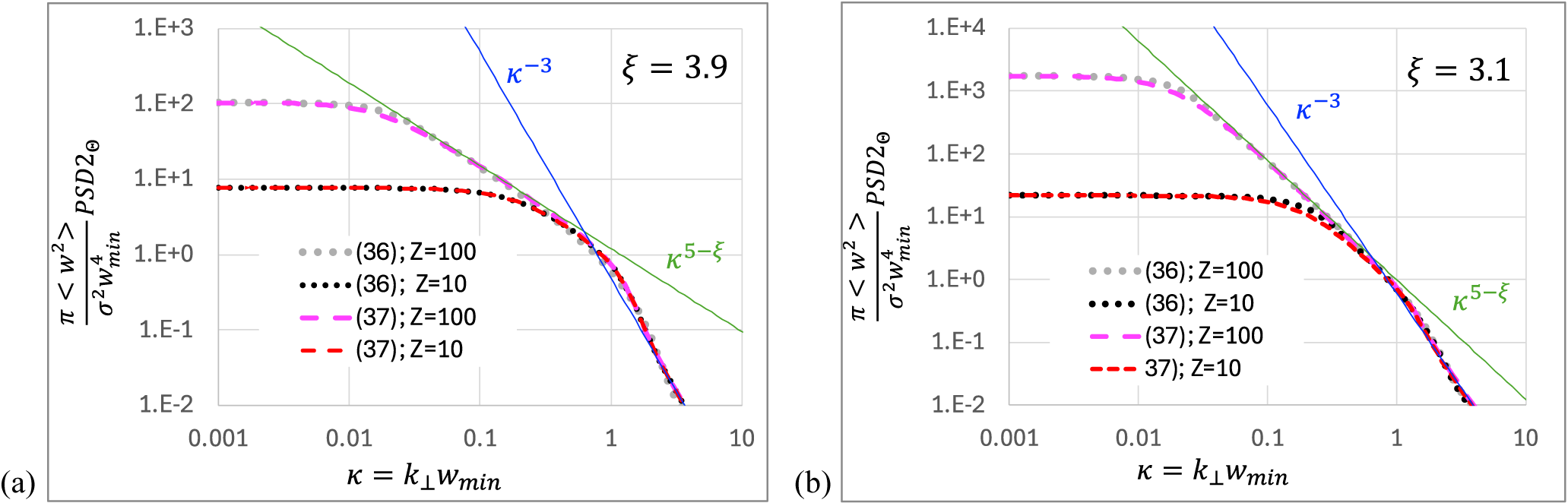

Figure 3

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}$

is normalized to

$\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}$

is normalized to

![]() $\frac{\sigma^2{w}_\mathrm{min}^4}{\pi <{w}^2>}$

as a function of

$\frac{\sigma^2{w}_\mathrm{min}^4}{\pi <{w}^2>}$

as a function of

![]() $\kappa ={k}_{\perp }{w}_\mathrm{min}$

for

$\kappa ={k}_{\perp }{w}_\mathrm{min}$

for

![]() $\xi =3.9$

(a) and

$\xi =3.9$

(a) and

![]() $\xi =3.1$

(b). Dotted curves represent exact Equation (36) values for Z = 100 (grey) and Z = 10 (black); dashed curves represent approximate Equation (37) values for Z = 100 (pink) and Z = 10 (red).

$\xi =3.1$

(b). Dotted curves represent exact Equation (36) values for Z = 100 (grey) and Z = 10 (black); dashed curves represent approximate Equation (37) values for Z = 100 (pink) and Z = 10 (red).

Next, it is necessary to substitute into Equations (32) and (33)

![]() $f(w)$

of a specific form, which may be quite complex. For example, for the optics of the standard indicated in Ref. [48],

$f(w)$

of a specific form, which may be quite complex. For example, for the optics of the standard indicated in Ref. [48],

![]() $f(w)$

has the form

$f(w)$

has the form

![]() $\log f(w)\sim {(\log w)}^2$

. We will restrict our consideration to the power form:

$\log f(w)\sim {(\log w)}^2$

. We will restrict our consideration to the power form:

given in Ref. [Reference Spaeth, Manes, Widmayer, Williams, Whitman, Henesian, Stowers and Honig23] for surface defects of optical elements after their use in a high-power laser facility. Under the almost always met condition

![]() ${w}_\mathrm{max}^{\xi -1}\gg {w}_\mathrm{min}^{\xi -1}$

, from

${w}_\mathrm{max}^{\xi -1}\gg {w}_\mathrm{min}^{\xi -1}$

, from

$\underset{w_\mathrm{min}}{\overset{w_\mathrm{max}}{\int }}f(w) \mathrm{d}w=1$

we obtain

$\underset{w_\mathrm{min}}{\overset{w_\mathrm{max}}{\int }}f(w) \mathrm{d}w=1$

we obtain

![]() ${A}_1=\left(\xi -1\right){w}_\mathrm{min}^{\xi -1}$

, that is,

${A}_1=\left(\xi -1\right){w}_\mathrm{min}^{\xi -1}$

, that is,

![]() $f(w)$

does not depend on

$f(w)$

does not depend on

![]() ${w}_\mathrm{max}$

. The data reported in Ref. [Reference Spaeth, Manes, Widmayer, Williams, Whitman, Henesian, Stowers and Honig23] correspond to

${w}_\mathrm{max}$

. The data reported in Ref. [Reference Spaeth, Manes, Widmayer, Williams, Whitman, Henesian, Stowers and Honig23] correspond to

![]() $\xi =3.9$

and

$\xi =3.9$

and

![]() ${w}_\mathrm{min}\approx 0.025\;\mathrm{mm}$

. Before using the optical elements in the high-power laser facility, the distribution function

${w}_\mathrm{min}\approx 0.025\;\mathrm{mm}$

. Before using the optical elements in the high-power laser facility, the distribution function

![]() $f(w)$

is also defined by Equation (34) with

$f(w)$

is also defined by Equation (34) with

![]() $\xi =3.9$

, but the laser damage was 7.8 times less[

Reference Spaeth, Manes, Widmayer, Williams, Whitman, Henesian, Stowers and Honig

23

,

Reference Stowers, Horvath, Menapace, Burnham and Letts

49

]. In what follows, we will assume

$\xi =3.9$

, but the laser damage was 7.8 times less[

Reference Spaeth, Manes, Widmayer, Williams, Whitman, Henesian, Stowers and Honig

23

,

Reference Stowers, Horvath, Menapace, Burnham and Letts

49

]. In what follows, we will assume

![]() $\xi$

and

$\xi$

and

![]() ${w}_\mathrm{min}$

to be arbitrary constants and use the above values only for constructing specific plots in Section 6. The moments

${w}_\mathrm{min}$

to be arbitrary constants and use the above values only for constructing specific plots in Section 6. The moments

![]() $<{w}^n>$

are readily calculated from Equation (34):

$<{w}^n>$

are readily calculated from Equation (34):

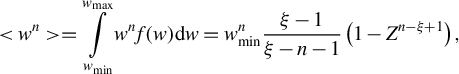

$$\begin{align}<{w}^n>=\underset{w_\mathrm{min}}{\overset{w_\mathrm{max}}{\int }}{w}^nf(w) \mathrm{d}w={w}_\mathrm{min}^n\frac{\xi -1}{\xi -n-1}\left(1-{Z}^{n-\xi +1}\right),\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}<{w}^n>=\underset{w_\mathrm{min}}{\overset{w_\mathrm{max}}{\int }}{w}^nf(w) \mathrm{d}w={w}_\mathrm{min}^n\frac{\xi -1}{\xi -n-1}\left(1-{Z}^{n-\xi +1}\right),\end{align}$$

where

![]() $Z={w}_\mathrm{max}/{w}_\mathrm{min}$

. For

$Z={w}_\mathrm{max}/{w}_\mathrm{min}$

. For

![]() $\xi =n+1$

, Equation (35) is valid within the limit

$\xi =n+1$

, Equation (35) is valid within the limit

![]() $\xi \to n+1$

. On substituting Equation (34) into Equations (32) and (33) and passing to dimensionless quantities

$\xi \to n+1$

. On substituting Equation (34) into Equations (32) and (33) and passing to dimensionless quantities

![]() $\kappa ={k}_{\perp }{w}_\mathrm{min}$

and

$\kappa ={k}_{\perp }{w}_\mathrm{min}$

and

![]() $K={k}_x{w}_\mathrm{min}$

, we obtain the following:

$K={k}_x{w}_\mathrm{min}$

, we obtain the following:

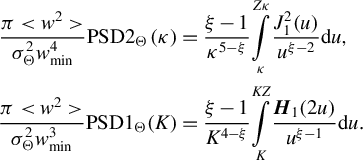

$$\begin{align}\frac{\pi <{w}^2>}{\sigma_{\Theta}^2{w}_\mathrm{min}^4} \mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left(\kappa \right)&=\frac{\xi -1}{\kappa^{5-\xi }}\underset{\kappa }{\overset{Z\kappa}{\int }}\frac{J_1^2(u)}{u^{\xi -2}} \mathrm{d}u,\nonumber\\\frac{\pi <{w}^2>}{\sigma_{\Theta}^2{w}_\mathrm{min}^3} \mathrm{PSD}{1}_{\Theta}(K)&=\frac{\xi -1}{K^{4-\xi }}\underset{K}{\overset{KZ}{\int }}\frac{{\boldsymbol{H}}_{1}(2u)}{u^{\xi -1}} \mathrm{d}u.\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\frac{\pi <{w}^2>}{\sigma_{\Theta}^2{w}_\mathrm{min}^4} \mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left(\kappa \right)&=\frac{\xi -1}{\kappa^{5-\xi }}\underset{\kappa }{\overset{Z\kappa}{\int }}\frac{J_1^2(u)}{u^{\xi -2}} \mathrm{d}u,\nonumber\\\frac{\pi <{w}^2>}{\sigma_{\Theta}^2{w}_\mathrm{min}^3} \mathrm{PSD}{1}_{\Theta}(K)&=\frac{\xi -1}{K^{4-\xi }}\underset{K}{\overset{KZ}{\int }}\frac{{\boldsymbol{H}}_{1}(2u)}{u^{\xi -1}} \mathrm{d}u.\end{align}$$

Both integrals in Equation (36) are expressed only through the generalized hypergeometric function

![]() $_2{F}_3$

, which complicates further analytical analysis. The expression in Equation (36) can be significantly simplified in three special cases: for

$_2{F}_3$

, which complicates further analytical analysis. The expression in Equation (36) can be significantly simplified in three special cases: for

![]() ${k}_{\perp }{w}_\mathrm{max}\ll 1$

and

${k}_{\perp }{w}_\mathrm{max}\ll 1$

and

![]() ${k}_{\perp }{w}_\mathrm{min}\gg 1$

, the functions

${k}_{\perp }{w}_\mathrm{min}\gg 1$

, the functions

![]() ${J}_1$

and

${J}_1$

and

![]() ${\boldsymbol{H}}_{1}$

may be replaced by their asymptotic forms, and for

${\boldsymbol{H}}_{1}$

may be replaced by their asymptotic forms, and for

![]() ${w}_\mathrm{max}^{-1}\ll {k}_{\perp, x}\ll {w}_\mathrm{min}^{-1}$

, the integration limits may be replaced by 0 and

${w}_\mathrm{max}^{-1}\ll {k}_{\perp, x}\ll {w}_\mathrm{min}^{-1}$

, the integration limits may be replaced by 0 and

![]() $\infty$

. In all special cases, a power-law dependence is obtained: in three sections of the spectrum

$\infty$

. In all special cases, a power-law dependence is obtained: in three sections of the spectrum

![]() ${k}_{\perp, x}{w}_\mathrm{max}\ll 1$

,

${k}_{\perp, x}{w}_\mathrm{max}\ll 1$

,

![]() ${w}_\mathrm{max}^{-1}\ll {k}_{\perp, x}\ll {w}_\mathrm{min}^{-1}$

and

${w}_\mathrm{max}^{-1}\ll {k}_{\perp, x}\ll {w}_\mathrm{min}^{-1}$

and

![]() ${k}_{\perp, x}{w}_\mathrm{min}\gg 1,$

${k}_{\perp, x}{w}_\mathrm{min}\gg 1,$

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}$

decreases in a power-law manner with powers

$\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}$

decreases in a power-law manner with powers

![]() $0,5-\xi\;\mathrm{and}\;3$

, and

$0,5-\xi\;\mathrm{and}\;3$

, and

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}{1}_{\Theta}$

with powers

$\mathrm{PSD}{1}_{\Theta}$

with powers

![]() $0,4-\xi\;\mathrm{and}\;2$

. This is demonstrated in Figure 3 where

$0,4-\xi\;\mathrm{and}\;2$

. This is demonstrated in Figure 3 where

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)$

in Equation (36) is plotted. The

$\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)$

in Equation (36) is plotted. The

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}1\left({k}_x\right)$

curves look similar. From Figure 3 it can be seen that

$\mathrm{PSD}1\left({k}_x\right)$

curves look similar. From Figure 3 it can be seen that

![]() $\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)$

is well approximated by the following expression:

$\mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left({k}_{\perp}\right)$

is well approximated by the following expression:

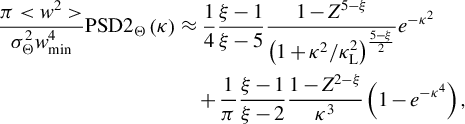

$$\begin{align}\frac{\pi <{w}^2>}{\sigma_{\Theta}^2{w}_\mathrm{min}^4} \mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left(\kappa \right)&\approx \frac{1}{4}\frac{\xi -1}{\xi -5}\frac{1-{Z}^{5-\xi }}{{\left(1+{\kappa}^2/{\kappa}_\mathrm{L}^2\right)}^{\frac{5-\xi }{2}}}{e}^{-{\kappa}^2}\nonumber\\&\quad+\frac{1}{\pi}\frac{\xi -1}{\xi -2}\frac{1-{Z}^{2-\xi }}{\kappa^3}\left(1-{e}^{-{\kappa}^4}\right),\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\frac{\pi <{w}^2>}{\sigma_{\Theta}^2{w}_\mathrm{min}^4} \mathrm{PSD}{2}_{\Theta}\left(\kappa \right)&\approx \frac{1}{4}\frac{\xi -1}{\xi -5}\frac{1-{Z}^{5-\xi }}{{\left(1+{\kappa}^2/{\kappa}_\mathrm{L}^2\right)}^{\frac{5-\xi }{2}}}{e}^{-{\kappa}^2}\nonumber\\&\quad+\frac{1}{\pi}\frac{\xi -1}{\xi -2}\frac{1-{Z}^{2-\xi }}{\kappa^3}\left(1-{e}^{-{\kappa}^4}\right),\end{align}$$

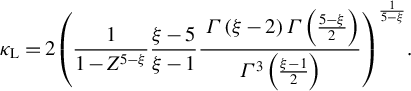

where

$$\begin{align}{\kappa}_\mathrm{L}=2{\left(\frac{1}{1-{Z}^{5-\xi }}\frac{\xi -5}{\xi -1}\frac{\;\varGamma \left(\xi -2\right)\varGamma \left(\frac{5-\xi }{2}\right)}{\varGamma^3\left(\frac{\xi -1}{2}\right)}\right)}^{\frac{1}{5-\xi }}.\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{\kappa}_\mathrm{L}=2{\left(\frac{1}{1-{Z}^{5-\xi }}\frac{\xi -5}{\xi -1}\frac{\;\varGamma \left(\xi -2\right)\varGamma \left(\frac{5-\xi }{2}\right)}{\varGamma^3\left(\frac{\xi -1}{2}\right)}\right)}^{\frac{1}{5-\xi }}.\end{align}$$

Compare the black and grey dotted curves with the red and pink dashed curves in the figure. If

![]() ${Z}^{5-\xi}\gg 1$

, which is true for

${Z}^{5-\xi}\gg 1$

, which is true for

![]() $\xi =3.9$

, then

$\xi =3.9$

, then

![]() ${\kappa}_\mathrm{L}$

is proportional to

${\kappa}_\mathrm{L}$

is proportional to

![]() ${Z}^{-1}$

, that is, to

${Z}^{-1}$

, that is, to

![]() ${w}_\mathrm{max}^{-1}$

(see Equation (38)). At the frequencies

${w}_\mathrm{max}^{-1}$

(see Equation (38)). At the frequencies

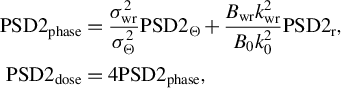

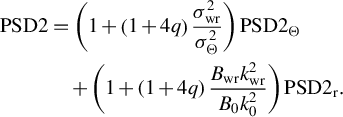

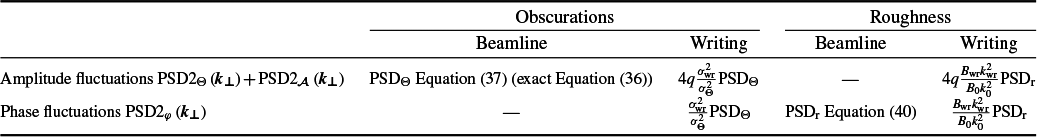

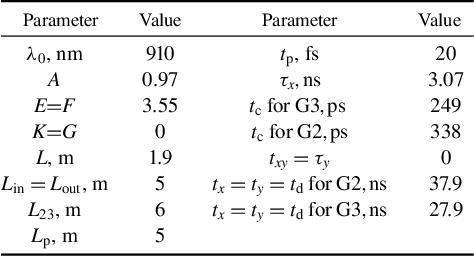

![]() ${k}_{\perp}\gg {w}_\mathrm{max}^{-1}$

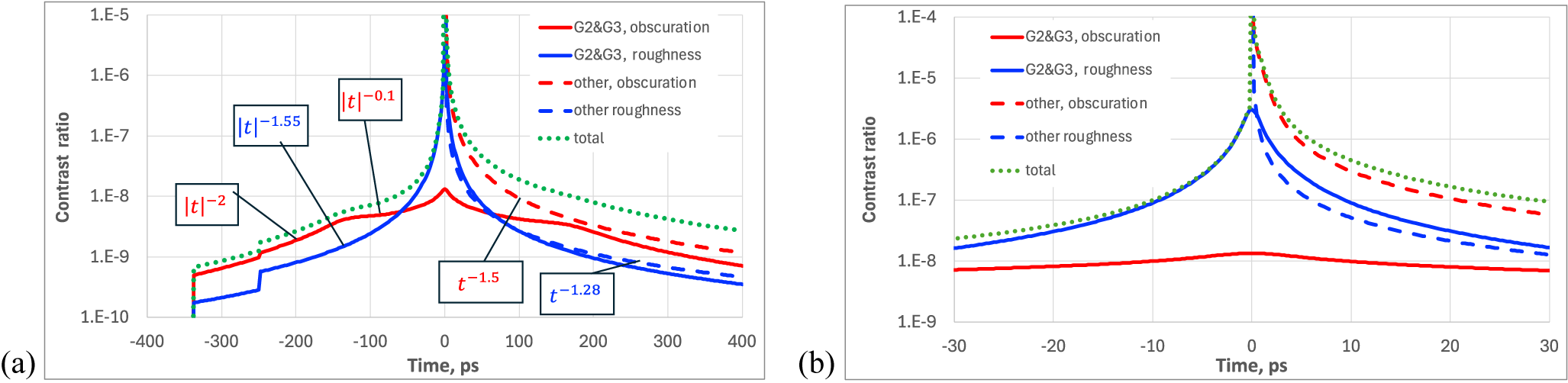

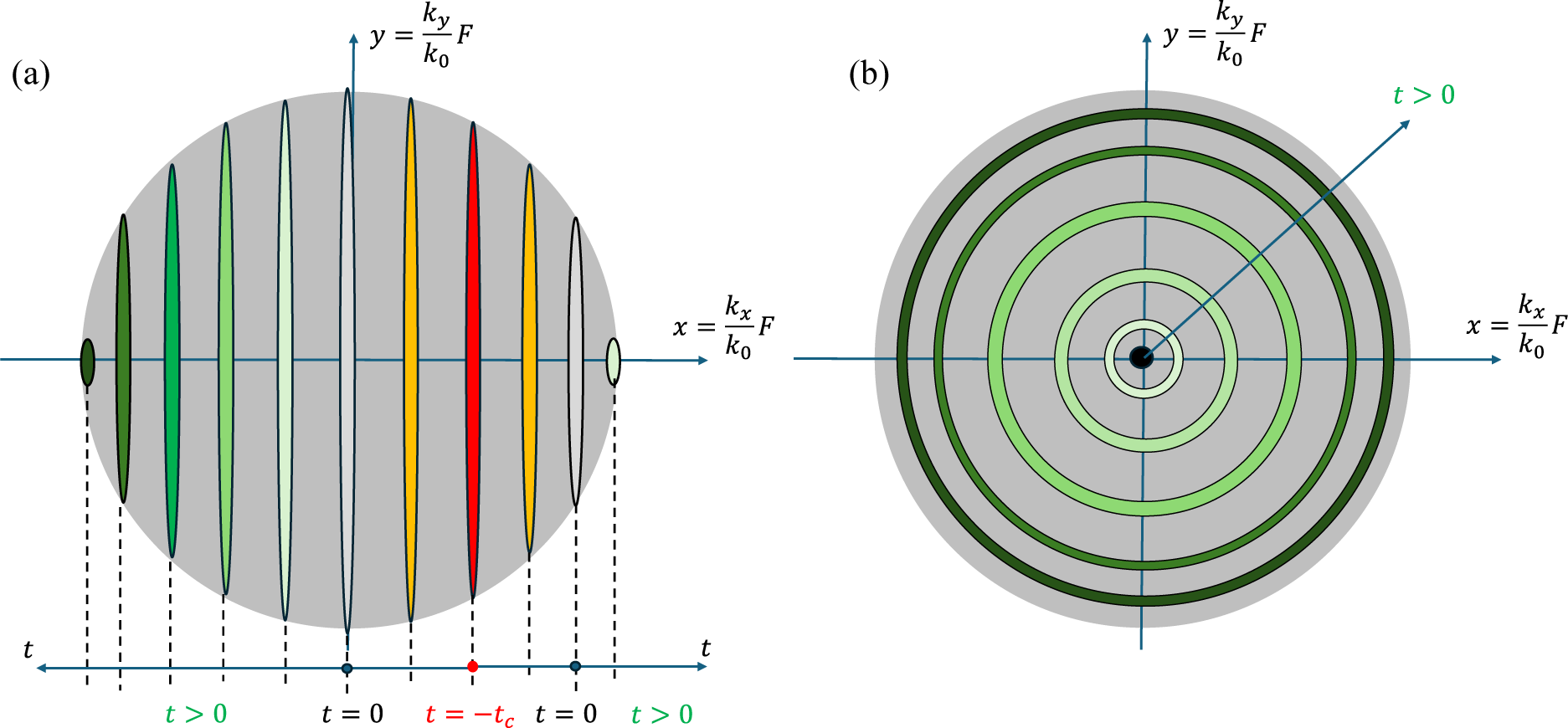

, the product