INTRODUCTION

Since the publication of the highly influential paper by KopytoffFootnote 1 and the further development of its central ideas by archaeologists,Footnote 2 the notion of object ‘biographies’ has become established in archaeological literature. To summarise briefly, Kopytoff suggested that it is important in studies of objects to consider not only the original purpose for which an artefact may have been made, but also the different ways that it may have been used through its lifetime, and the different meanings that may have been attached to it culturally during this period. This might include aspects such as origin, circulation, variability in use through time (including for instance recycling), and the process of becoming obsolete, etc.Footnote 3 As Joy argues,Footnote 4 Kopytoff's theory is still central to our understanding of the way in which artefacts are transformed by their context of use. An important aspect archaeologically, for instance, is curation, which could be defined as the retention of an artefact well beyond its production date, entailing in all likelihood some changes in the cultural perception and use of the artefact. In turn, grasping the changing uses and meanings of artefacts has the potential to add to our understanding of wider social and cultural transformations. This article seeks to document and provide an explanation for the adaptation and re-use, and subsequent deposition, of late Roman bracelets. It fully investigates these objects via an artefact biography approach to bring a new dimension to earlier studies based on their production and initial distribution.Footnote 5 In so doing, the paper engages with Joy's suggestion that our understanding of artefact biography would be enhanced through a detailed understanding of moments of object transformation.Footnote 6 Though the way in which an artefact functions in society can change without any physical alteration to the artefact itself,Footnote 7 the focus of this paper is on physical changes to artefacts, which can be studied productively in conjunction with their deposition contexts. Curation of artefacts is perhaps most obviously associated with a response to reduced availability of goods. Recent research has shown, however, that it may carry other meanings, in relation to psychological attachment and individual narratives or memories,Footnote 8 ancestor cults, collective memory, and status display.Footnote 9 These interpretations are not mutually exclusive and there is a need to relate the functional to the ideological meanings.Footnote 10 These recent observations are reflected in the analysis set out here.

IDENTIFYING RE-USE

Copper-alloy bracelets were in use throughout the Roman occupation of Britain, though they only seem to have become popular in the late Roman period. A wide variety of styles exists, some of which are not closely datable within the Roman period, for instance cable bracelets made from twisted wire. However, there are some characteristic early and late types: bracelets in the form of a snake rendered in a naturalistic style are early, for instance, as are strip bracelets with a wide band; those with a narrow band are late Roman, as are the distinctive crenellated bracelets that have been termed ‘cogwheel’ or ‘toothed cogwheel’ bracelets. Narrow band bracelets occur in very large numbers, especially at late Roman cemetery and votive sites, and are decorated with a wide range of motifs, often stamped into the outer surface.Footnote 11

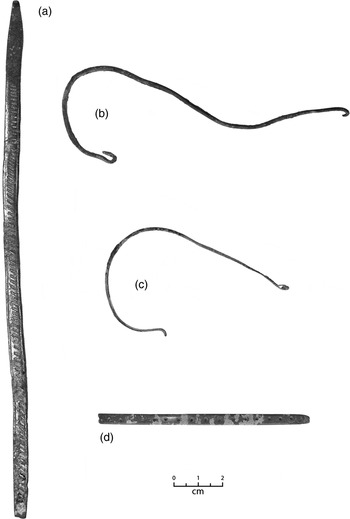

The most notable modification of Roman bracelets is through their adaptation into rings with a smaller diameter than the original items (179 were collected, listed in Appendix 1; some examples are shown in fig. 1). In this modification, the bracelet has often been visibly bent out of shape at one or more points on the circumference, and one or both original terminals have been cut off. These criteria can be used to identify a modified Roman bracelet. A good knowledge of the range of form and decoration extant in Roman bracelets is also necessary.Footnote 12 To avoid confusion with other miscellaneous ring-shaped fittings, undecorated objects were not included unless there was evidence of a bracelet terminal at one end.Footnote 13 The resulting rings vary in diameter (maximum inner diameter) from 8 to 45 mm.

FIG. 1. Some examples of Roman bracelets cut down into smaller rings: (a) Great Barton SF611A11; (b) Swindon WILT-026081; (c) Bradford Peverill 73E2D7; (d) Woodeaton (Ashmolean 1921.160); (e) Shakenoak (Ashmolean 1970.164); (f) Hitcham SF-B14062.

Although these rings made from re-used bracelets superficially resemble Roman finger-rings and, sometimes, earrings, it was seldom a problem distinguishing between them. Roman hoop earrings usually have one or more tapered terminals for insertion into pierced ears,Footnote 14 while earrings made from wires twisted together have tapered or hooked terminals.Footnote 15 Finger-rings without a central setting can have decoration similar to that on bracelets,Footnote 16 but the bracelets are often of a wider gauge than the finger-rings, allowing them to be distinguished (finger-rings are typically no wider than 2 mm, whereas most bracelets tend to be around 4 mm wide). Where they are similar in both decoration and width, evidence of modification, as described above, is needed to confirm the identification. Good evidence of re-use was required for the material to be included in this study, and examples where significant doubt remained about the exact identification have been omitted.Footnote 17 In a number of possible cut-down bracelets, re-use was not absolutely certain owing to incompleteness of the circumference or poor illustration, and so on, but these were judged from their overall appearance to have very probably been adapted and they are included in this study. Those examples that represent probable rather than definite re-use are indicated in Appendix 1. There are also a large number of bracelets that were modified to form other shapes, including bracelets that had been flattened, pulled open, twisted or otherwise bent out of shape (some examples are shown in fig. 2). These will also be discussed further below.

FIG. 2. Some examples of distorted and flattened bracelets: (a) Wroxeter (Bushe-Foxe 791242, English Heritage Archive, Atcham); (b–d) Shakenoak (Ashmolean 1973.717, 1973.746, 1973.725).

DATA COLLECTION

Data were mostly collected from published excavated sites and the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) database. Site archives for Wroxeter, London, Canterbury and Mucking were visited to increase the number of examples from securely dated contexts. Assemblages from Woodeaton and Shakenoak (held in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford), both with particularly significant collections of relevant material, were also examined. Other museums provided additional information on some published finds, confirming details that were ambiguous in published drawings, for instance, or supplying photographs of material not illustrated. Hilary Cool's unpublished thesis on Roman personal ornaments provided a number of further examples from museum collections.Footnote 18 A wide chronological range was deliberately included: both early and late Roman sites, and Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, in order to evaluate possible re-use across the late/post-Roman to early Anglo-Saxon transition period. Rings made from re-used bracelets have been variously categorised in site reports as bracelets, finger-rings, or other types of rings and fittings. Many catalogues correctly identified the artefacts as cut-down bracelets without further discussion. To address the biases associated with Portable Antiquities Scheme data (for instance, selective collection and reporting, and in detection activity according to land-use or known nature of site, etc.), the distribution of PAS artefacts was carefully evaluated against trends in wider multi-period PAS data.Footnote 19

DATING

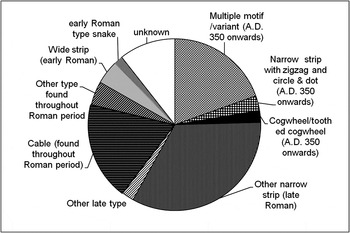

Dating can be approached in two ways; firstly, through the stylistic date associated with a particular type of artefact ( fig. 3), which gives a terminus post quem for the production of the modified object; and secondly through the site context. Stylistically, the majority of modified bracelets are late Roman; that is, broadly fourth-century in date. This is unsurprising, since late Roman bracelets are much more numerous in general than early types. There are a few examples from the early Roman period, and also a number that are of types not easily datable through style, though they are perhaps more likely to be third- or fourth-century in date, since this is when bracelets attain their greatest popularity. Of the late Roman styles, more precise dates have been suggested for three types: narrow strip bracelets with circle-and-dot motifs combined with a zig-zag pattern made from notches on alternate edges;Footnote 20 multiple motif bracelets, which have a design of various motifs symmetrical around a central point (together with the closely related form with alternating patterns, included here in the same category); and cogwheel bracelets, both toothed and non-toothed variants. Each type is found in contexts dating from a.d. 350 into the early fifth century.Footnote 21 Many other ‘late’ types of bracelet also show a profile of contexts that suggest dates of a.d. 350 onwards,Footnote 22 though investigation of a wider chronological range of sites than was used in this study would be needed to confirm this.

FIG. 3. Pie chart showing the stylistic dates of bracelets in the data sample.

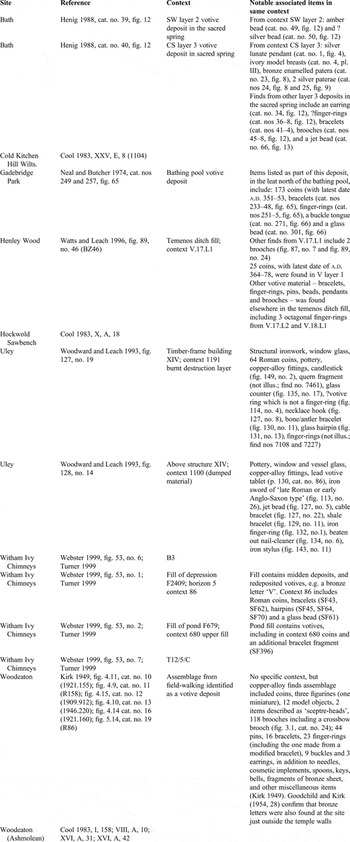

Date ranges for re-used objects are potentially elastic, since re-use can occur over long time-spans and instances of re-use may not be related to one another. However, in this instance, most of the dates of deposition for the re-used objects cluster together in a similar manner to the stylistic dates. There are no contexts definitely earlier than a.d. 370, and many date to the early fifth century (Table 1). Those examples from contexts with broad date ranges at Mucking and Colchester must also fall into the later part of the range since they contain re-used bracelets that stylistically are late Roman. Taking into account that many of the date ranges suggested will tend to be on the cautious side — with an unwillingness to ascribe dates beyond a.d. 410 in earlier site reportsFootnote 23 — a conservative view of the dating for the deposition of most of the re-used bracelets would be late fourth to early fifth centuries, while those who argue for a ‘long’ chronology would see the date possibly extending further into the fifth century.Footnote 24 Dates after a.d. 450 at Uley, and the sixth century or later at Wroxeter baths basilica, are derived from redeposited dumps of earlier material, suggesting that at these sites — and probably more widely at other post-Roman sites — re-used bracelets did not continue in use beyond the mid-fifth century. Unfortunately, there are no context dates for the few re-used bracelets that are stylistically early, so it is not possible to be sure whether these were reworked into smaller rings in the early or late Roman period. However, it would seem likely from the existence of early types among those modified that some re-use will have occurred in all periods.

TABLE 1. Context dates for roman bracelets made into smaller rings found on roman sites

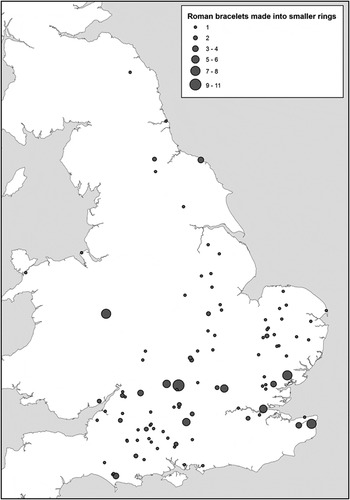

There are also a number of re-used bracelets from dated contexts in Anglo-Saxon cemeteries (Table 2). In some cases, only a broad date range for the cemetery as a whole is suggested in the site report, but a more restricted date range for the relevant grave could be found elsewhere (e.g. the graves at Worthy Park and Orpington have been more closely dated by other scholars) or proposed from the datable objects in the grave assemblage (e.g. at Empingham, Reading, Westgarth Gardens, and Blewburton Hill). All of the dates appear to fall in the fifth to mid-sixth centuries, though the date for Empingham could not be refined further than generally sixth century. The dating of the graves at Reading and Westgarth Gardens was also problematic (see Table 2). Anglo-Saxon contexts containing cut-down bracelets will be discussed further below, including consideration of the specific grave assemblages in which the re-used bracelets were found.

TABLE 2. Context dates for roman bracelets made into smaller rings found on anglo-saxon sites

DISTRIBUTION

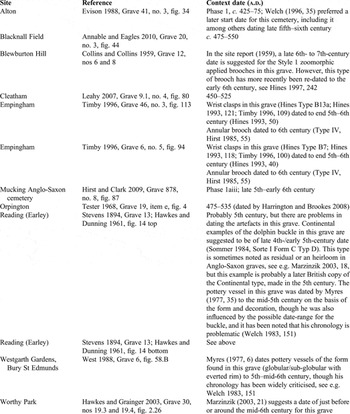

fig. 4 illustrates the distribution of sites from which material was catalogued. PAS sites (metal-detected material collected through the Portable Antiquities Scheme) can be compared with those plotted from excavated and other non-PAS finds; the distributions overlap for the most part, though there are absences of PAS material in the most westerly and northerly areas and a particular concentration in East Anglia. These trends are strongly evident in PAS distributions generally, and thus have no particular significance here.Footnote 25 The differential distributions of PAS and non-PAS material confirm the importance of using as wide a range of data sources as possible in order to overcome some of the biases inherent in any one type of source.

FIG. 4. Distribution map showing PAS data compared with data from excavation and other sources.

fig. 5 shows the general distribution of all the rings made from cut-down Roman bracelets and the numbers per site. The patterning is similar to that for late Roman bracelets more generally,Footnote 26 which suggests that this type of modification occurred wherever Roman bracelets were available. In both distributions, there is a notable absence of material in the West Midlands, which otherwise has produced a high density of Roman finds and rural sites.Footnote 27 Since late Roman bracelets seem mostly to be a phenomenon of the second half of the fourth century, the corresponding absence of late Roman coins in this areaFootnote 28 may suggest that chronological changes in site occupation or availability of material are the main causes. By contrast, an absence of finds in the area below the Wash, in the Weald of Kent, and on the East Sussex coast, is paralleled by many fewer instances in the general distribution of PAS Roman finds in these areas.Footnote 29 Notably less dense rural settlement in the Weald of Kent and on the coast of East Sussex is also well-documented by Taylor.Footnote 30 These gaps in the distribution are, therefore, not likely to be significant. Overall, the distribution confirms the widespread nature of the phenomenon and may support the late dating proposed, above.

FIG. 5. Distribution map of Roman bracelets that have been made into smaller rings.

PROFILE OF SITE-TYPES

Following the methodology applied to Romano-British small finds by Eckardt,Footnote 31 the site-type profile can be examined to see if there is any evidence of bias to a particular type of site. The Roman sites where cut-down bracelets have been found include large and small towns, military sites, rural settlements (including villas) and temple sites, with the largest category of site-types being rural settlements ( fig. 6a). As already noted, modified bracelets were also found at eleven Anglo-Saxon cemeteries (some of which were themselves on the sites of earlier Roman rural settlements) and in an Anglo-Saxon context as well as in Roman layers at Shakenoak Roman villa (see below). Many of the sites represented by Portable Antiquities data will also have been rural settlements, though a couple of exceptions whose character is known, such as Mildenhall and Hockwold-cum-Wilton, can be noted (a small town and temple respectively). Fewer than a third of the sites are large towns and military sites, where Roman material culture would have been much more prevalent.

FIG. 6. (a) Pie chart showing the proportions of different site-types represented among the data; (b) pie chart showing the numbers of Roman bracelets made into smaller rings at the different site-types.

The largest numbers of modified bracelets per site come from large towns (Colchester, Silchester, St Albans and Wroxeter), the military site of Richborough, the Roman and Anglo-Saxon rural settlement and cemetery of Mucking, and the Roman temple site at Woodeaton. In the case of the larger sites this will be the result of the correspondingly greater areas occupied, excavated, or published; the presence of very late occupation levels at these sites may also be significant. The relatively large numbers found at Mucking, Colchester and Woodeaton result from the deliberate nature of the deposits, namely cemetery and votive, rather than being the result of accidental loss. These special deposits will be discussed further below. Deliberate deposition is also evident at a number of the other temple sites.

Considering numbers per site-type ( fig. 6b), sites recorded by PAS collectively produced the most, followed by large towns, and then rural settlements. However, considering that most of those sites recorded by PAS will be rural settlements, and that some of the examples from Anglo-Saxon cemeteries will also have been derived from Roman rural settlements — either from the same site or near by (see below) — it is clear that in reality more of these objects come from rural settlements collectively than from any other site-type. Comparing these data with the distribution pattern of late Roman bracelets in general,Footnote 32 it is clear that late Roman bracelets were found frequently at rural sites too, though an exact comparison cannot be made since the earlier study did not include PAS data or Anglo-Saxon sites. It is currently also difficult to compare the profile for rings made from re-used bracelets with other late Roman artefacts, because of the difficulty in finding studies that use a comparable range of sources of evidence. One possible comparator, nail-cleaner strap-ends,Footnote 33 shows a greater proportion from small towns than from rural sites (taking their categories of rural and villa collectively), but the data collected were from published sources onlyFootnote 34 and did not include objects from museum collections or PAS data, which would probably increase the proportions from rural sites.

HOW WERE THE OBJECTS USED IN THE ROMAN TO EARLY POST-ROMAN PERIOD?

In order to consider this question, it is necessary to examine the decoration, form (including dimensions), and contexts in which the modified bracelets were found.

Approaching these items as decorated artefacts, we can consider the function of their decoration to constitute the items as bracelets; what might be termed the ontological function.Footnote 35 Late Roman bracelets in Britain have a distinctive range of styles which, although lying within wider contemporary trends, are, in their detail, typical of bracelets and/or dress accessories in particular. Along with the form and dimensions of the artefacts, the presence of this decoration would have assisted in constituting the objects as bracelets to their owners. Unless the cut-down bracelets were made very much later than the time period when the original bracelets were circulating — which is unlikely given the context dates, and explicitly disproved by cemetery evidence in some cases (see below) — initially at least their decoration would have linked them explicitly to the objects from which they had been made. This makes it likely that they themselves would also have been regarded as dress accessories of some kind.

The form and dimensions of many of the rings made from re-used bracelets give them the appearance of finger-rings. The overall profile of their inner diameters can be examined to see if they occur in the same range of sizes and frequency of sizes as Roman finger-rings ( fig. 7), but it must be pointed out that the diameters of the rings made from re-used bracelets are much more irregular than normal finger-rings, so an exact comparison is not possible. The maximum internal diameter is used in each case, but those examples where it is not known whether the measurement given related to the inner or outer diameter are excluded.

FIG. 7. Inner diameters of Roman finger-rings in the British Museum (those catalogued in Marshall Reference Marshall1907) compared with the inner diameters of cut-down bracelets in the data sample.

Data drawn from a catalogue of Roman finger-rings in the British MuseumFootnote 36 show a range from 12 to 25 mm in inner diameter, with the majority occurring between 14 and 19 mm (the numbers rise and drop significantly on either side of this range). The most frequently occurring diameter (the modal average) is 17 mm. Another set of finger-ring data, compiled by Furger from the Roman site of Augst in Switzerland,Footnote 37 gives similar results, with a range of 9–24 mm and a modal average of 17.5 mm. Furger differentiates between different types of finger-rings, and shows that some types have a preponderance of larger sizes, peaking around 19.1 mm. From comparison with modern finger-rings, he suggests that types with a modal average at this size are likely to have been men's rings,Footnote 38 and that finger-rings worn by men mostly have an inner diameter of 19–24 mm.

For rings made from re-used bracelets, there is a much wider span in the data, with the smallest being 8 mm, the largest 44 mm, and a modal average of 20 mm. Most of the rings occur in diameters between 14 and 21 mm, the numbers rising and dropping either side of this range, but with another spike at around 34 to 35 mm. This suggests two different types of object, each distributed normally around the most popular sizes. Most of the smaller examples, of 26 mm and below, exist in the correct range and frequency of sizes to have been used as finger-rings by both sexes. However, the comparison is not conclusive, especially for the very small examples of less than 12 mm. These smaller rings could have been used in other ways, for example as pendants. It should be noted that finger-rings with similar diameters to these are known, and are thought to have been made for children.Footnote 39 The larger examples, 27 mm and upwards, could possibly have continued to be used as bracelets, but worn by children. Child bracelets are known from the Roman period, for instance at Colchester.Footnote 40 Additional evidence for use can be sought from the particular Roman contexts in which the modified bracelets were found. The most useful of these are firstly grave contexts, and secondly votive deposits.

ROMAN GRAVE CONTEXTS

Examination of context confirms that the larger examples did indeed continue to be used as bracelets, and that they were worn by children. Eight examples were found in grave contexts.

At the Butt Road cemetery, Colchester, Grave 1 contained three cut-down bracelets among a pile of six other bracelets, all child-sized,Footnote 41 to the south side of the coffin. This grave also contained an earring to which a soldered strip had been added to convert it into a bracelet;Footnote 42 the other bracelets had originally been made in very small sizes. The grave was that of a ten-year-old child (age from physical anthropology). Another grave at the same site, Grave 24, again contained a cut-down bracelet among others, also child-sized, in a pile in the coffin.Footnote 43 In this instance the age of the occupant could not be ascertained from the physical remains, but it was suggested in the site report that a child was likely, since the size of the grave-cut was small.Footnote 44 Both of these graves were dated to Period 2, a.d. 320/40–400+.

At the Lankhills Romano-British cemetery, Winchester, Grave 327 contained a cut-down bracelet amongst a pile of other bracelets near the left chest. Three of these bracelets appear to have been newly-made in small sizes, which could only have been worn by children;Footnote 45 for the other two (bone) bracelets, the diameter could not be reconstructed.Footnote 46 Age and sex were not known in this case. The grave was dated a.d. 350–70.

Two examples were found in the Romano-British cemetery at Mucking,Footnote 47 in Grave 30 at the foot of the grave. In this instance the physical anthropology indicates that the grave was apparently that of an adult. If this is the case, it is unlikely that the cut-down bracelets, with diameters of 35 and 42 mm, could have been worn by the occupant. At the same site, Grave 15b — a disturbed burial — also contained a cut-down bracelet. Neither of these graves was closely dated.

The deposition patterns are normal for the late Roman period in Britain where bracelets are sometimes found in a pile in the grave, perhaps because they had been placed in a bag or box which no longer survives.Footnote 48 None of the smaller rings was found in a Roman grave context, so this cannot be used to confirm their function.Footnote 49 Their absence, however, does not preclude them being an item of jewellery. The frequency of sizes indicates that, if they were finger-rings, they were worn mostly by adults, and it is apparent that adult graves were furnished with jewellery less often than those of children. Hence, it is less likely that such items would have been placed in an adult grave, even though they may have been worn in life. In addition, if deposition occurred within the fifth century for many of the items, this was a time when unfurnished burial was becoming established.Footnote 50 So at cemeteries where an unfurnished rite had become the norm, it would not have been appropriate to place dress accessories in a grave.

VOTIVE SITES

Votive contexts also provide some useful evidence, illustrating how both the smaller and larger cut-down bracelets were regarded at the point of deposition. Twenty-one examples come from seven temple sites, with another two from a possible votive context at Gadebridge Park Roman villa. The evidence is summarised in Table 3. In the Roman period, it was common practice to deposit jewellery and dress accessories (along with other items such as coins) as a votive offering, and many Roman temple sites have extensive collections of these items.Footnote 51 The offering would have been made in the hope that the god would help with a particular problem, or as thanks for the assistance received. At sites where feminine dress accessories predominate, it is possible that the shrine had a particular reputation for addressing female health issues.Footnote 52 The specific deposition contexts in Table 3 strongly indicate votive use. The additional presence in these votive deposits of many other items of jewellery with the cut-down bracelets would suggest that the latter were also regarded as jewellery.

TABLE 3. Details of roman bracelets made into smaller rings found in votive contexts

WERE THE OBJECTS MADE AS RITUAL ITEMS?

In both of these cases of ritual deposition — in graves and as votive offerings — consideration can be given as to whether the objects were refashioned specifically for ritual use. Arguably, the rings might have been made from broken bracelets into objects resembling complete bracelets and finger-rings purely for the purposes of deposition in a grave or votive context.Footnote 53

The grave contexts above show apparently complete original bracelets being deposited along with cut-down examples, with larger numbers of the former in each case. It would appear that each category is being used in the same way and thus is apparently regarded in the same way. The cut-down examples could have been made at the point of deposition to supplement the others placed in the grave, or, if the grave-goods represent the personal possessions of the dead, they may have been worn in life with the others.

In considering the Roman bracelets from Woodeaton, it is notable that the assemblage contains very few complete, undamaged examples ( fig. 8 shows some of the modified bracelets found at the site). In Kirk's publication of the bronze finds, there are five cut-down bracelets which are now child-sized,Footnote 54 three complete Roman bracelets,Footnote 55 one broken and mended bracelet,Footnote 56 two bracelet fragments,Footnote 57 four bracelets with broken fastenings,Footnote 58 and one which is complete but broken into two pieces.Footnote 59 There are also some other examples of modified bracelets from the site not published by Kirk (see Appendix 1). The variety of different types of damage, repair and deliberate modification suggests that the nature of the assemblage is neither the product of post-deposition damage or of a type of ‘ritual killing’. As noted in the site report,Footnote 60 it could be the case that, at this site, bracelets were being reworked, or previously modified bracelets were being selected, specifically for the purposes of votive deposition. However, it could also be the case that only damaged or reworked examples were available in the period at which these deposits were made (see below). It is possible, then, but not certain, that some of these items were specially made for the purposes of ritual deposition, to resemble complete items. In this way, they could have become symbolic ‘representations’ of the original artefacts.Footnote 61

FIG. 8. Bracelets from Woodeaton: (a) Ashmolean 1946.220; (b) Ashmolean 1921.155; (c) Ashmolean 1921.167.

At the temple site of Uley, large numbers of cast ring-shaped objects were also found, mostly with internal diameters of 12–17 mm and external diameters of 20–30 mm. It is thought that they were made purely for votive deposition.Footnote 62 Although they are very different in appearance to the cut-down bracelets, with heavier and thicker rings that are much wider in relation to their internal diameter,Footnote 63 it raises the question as to whether some of the rings discussed in this article were refashioned merely as ring-shaped objects, without the connotations of jewellery, for the purposes of ritual deposition. It could even be the case that the smaller rings were used as ring-money, small change in a fifth-century period when the supply of copper-alloy coins had ceased, yet higher-denomination coinage was still available. Votive use would be consistent here too, since coins are often deposited at shrines. In order to evaluate this, the weights of the smaller rings were assessed,Footnote 64 since consistency in weight might imply a use as coinage. Although weights are not normally given in finds catalogues, the weights of many of the rings on the PAS database are, fortunately, specified. These proved to be very variable, with no consistent patterning of any kind, undermining, though not completely ruling out, the possibility of their use as currency. The presence of other types of jewellery in votive deposits along with rings made from cut-down bracelets (Table 3) also suggests that it is probably not the quality of being ring-shaped, nor the conceptualisation as money, but the categorisation as bracelets, which is important in the selection for votive use.

In addition, cut-down bracelets occur widely in occupation deposits across the full range of Roman settlement types (see fig. 6a), and many more occur in these types of contexts collectively than are found at temple sites. It appears, therefore, that many were made and used as part of daily life rather than as specifically ritual objects.

In summary, although a range of other uses can be considered, use of the rings made from cut-down bracelets as jewellery appears most likely, given the assembled evidence above.

EVIDENCE FOR THE PROCESS OF MAKING A RE-USED OBJECT

An examination of how, and in what circumstances, the artefacts were made also contributes to our understanding of their use and meaning. In considering excavated sites with cut-down bracelets — where there is good evidence of the general site assemblage (a total of 50 sites) — around 40 per cent of them have produced other distorted bracelets; sometimes complete or near-complete bracelets flattened into strips or pulled open, but more often fragments of bracelets that had been flattened, bent or twisted ( fig. 2). These distorted bracelets occurred more widely on other sites as well ( fig. 9). The distortion of bracelets is clearly a multi-period phenomenon, with some instances from the second century,Footnote 65 though most datable examples lie within the period of the mid-fourth to early fifth centuries. While a few examples may have resulted from accidental post-deposition damage, clearly this cannot account for most of the flattened material. The wide occurrence of the phenomenon in excavated contexts, as well as on metal-detected sites where post-deposition damage might be expected to be more of a problem (see Appendix 2), suggests a deliberate practice. Distorted bracelets occur across the full range of different site-types and this, together with their generally wide distribution, implies that these kinds of modification were carried out in many different places using locally available objects, rather than via the mass collection of objects and subsequent modification on a large scale at a few sites. While a basic child-sized bracelet could be produced from an adult-sized one by pulling in the ring at a particular point to reduce the circumference and then cutting off the end, more evenly circular bracelets and rings could be produced by firstly flattening the adult-sized bracelet and then reforming it into a new circle. In a likely example of this scenario, at Shakenoak, part of a bracelet decorated with a repeated ‘S’ motif,Footnote 66 found in a refuse deposit dating to c. a.d. 350, could be matched with a ring made from another section of it found in the fill of the enclosure ditch.Footnote 67 The decoration and dimensions (both the narrowness of the strip at c. 2 mm, and the way that it tapered towards the end) of the two finds were a close match. The discrepancy in dating suggests that the ring was made at a much earlier date than that of its deposition context.

FIG. 9. Distribution map of sites where flattened and distorted bracelets were recorded.

Although the evidence from sites where cut-down bracelets were found suggests that bracelets were sometimes distorted as part of the process of converting them into smaller rings (as at Shakenoak above), modification of bracelets is of course likely to have been carried out for a number of purposes. Bracelets could be re-shaped into other objects, for example the bracelet strips re-formed into hooks at Uley,Footnote 68 MarshfieldFootnote 69 and Thrussington.Footnote 70 Others may have been modified preparatory to melting them down for the casting of new objects (see below). While in other cases, the process may have been an attempt to destroy the object without intention to re-use, perhaps for ritual purposes.

There are examples among both the rings made from re-used bracelets and the flattened and distorted bracelets where the fastening has been broken and it is possible that it was at this point that the original artefact was set aside for recycling.Footnote 71 Yet there are also complete bracelets that appear to have been significantly distorted,Footnote 72 implying that at least in some cases these bracelets were being modified because they were no longer valued in the same way. Particularly large assemblages of bracelets and bracelet fragments that have been flattened or distorted occur at Piercebridge, St Albans, Canterbury and Uley; good contextual information was available at the latter two sites, which will be examined in more detail.

Canterbury

Virtually all of the bracelets from the Canterbury Marlowe site consist of fragments, with only two complete examples.Footnote 73 Most of the flattened and distorted examples came from residual contexts, although three were found in mid- to late fourth-century contexts (Period 4II), one in Room 6 of Building R26, and two in a lane by the same building (Canterbury Marlowe Site III). The excavated part of the building was a bath suite attached to a house,Footnote 74 which had been remodelled in Period 4II with the superposition of new floor layers and the construction of two furnaces.Footnote 75 A nearly complete crucible was found in an earlier Period 4I layer in this building (AM no. 815444), as well as a fragment of a crucible in a Period 4III layer. Copper-alloy waste from casting was also found in Period 4 contexts from the Marlowe site excavations.Footnote 76 It thus appears that the flattened and distorted bracelets were connected to metalworking, including perhaps their melting down.

One child-sized bracelet made from a cut-down bracelet was found at the site in a context dated a.d. 300/20 to early fifth century (Site III).Footnote 77 Two bracelets that had been cut down into rings were also found: one from a ‘dark earth’ layer (dated to a.d. 400/10–475/500) on Site IVFootnote 78 and another which was unstratified.Footnote 79 Although the former was described in the site report as being ‘residual’ (presumably because it was identified as a fourth-century-style bracelet), it may well not have been. It is perhaps significant that its deposition date is later than the context dates for the other distorted and flattened bracelets, that appear to have been in the process of modification, which suggests a period of use as a modified object in circulation.

Uley

Most of the bracelets found at this site were fragments.Footnote 80 Bayley analysed their composition and found 60 per cent to be brass.Footnote 81 Analysis also showed that the ring made from a re-used bracelet and the bracelet cut down into a child-sized bracelet were both of bronze;Footnote 82 while the flattened or otherwise distorted examples, comprise one that was listed merely as copper-alloy,Footnote 83 two of bronze,Footnote 84 two of leaded gunmetal or leaded gunmetal/bronze,Footnote 85 and four of brass.Footnote 86 Examples of flattened and distorted bracelets from stratified contexts only — excluding those from votive dumps made later — include two from Structure II (the main temple) which date to the end of the fourth and the early fifth centuries respectively. The bracelet cut down into a ring from the site was found in Structure XIV in a context dating to the mid-fourth to early fifth century,Footnote 87 while the bracelet cut down into a child-sized bracelet came from the same area,Footnote 88 but in a context dating from the mid-fifth century onwards (a re-deposited votive dump). It is, therefore, only in the latter instance that the deposition of the cut-down bracelet can be chronologically separated from its apparent phase of production.

There is much evidence from Uley for copper alloy working;Footnote 89 including fuel-ash slag and copper-alloy waste, and a fragmentary bracelet from Structure XIV itself.Footnote 90 There is also evidence for the production of plain, thick, cast or sheet metal lead-filled copper-alloy rings, which are thought to have been made at the site for ritual deposition.Footnote 91 These were mostly found in Phase 6 (end of fourth to early fifth century) onwards.Footnote 92 They are of very varied composition with relatively high lead content, and two-thirds were made from mixed alloys. Their composition is thought to suggest that they were made from randomly recycled metal objects,Footnote 93 which would themselves have been of varied composition, like the bracelets mentioned above. Once again, it is possible to link the existence of flattened and distorted bracelets with metalworking and perhaps the casting of new objects.

In the fourth century, recycling through melting down metals occurred widely. Dungworth studied the alloy composition of a number of types of Roman artefacts, including bracelets. He found that 64 per cent of the copper-alloy artefacts dating to the fourth century were composed of leaded bronze and leaded gunmetal, with smaller proportions of leaded brass and unleaded bronze and gunmetal alloys, and only 4 per cent of unleaded brass. The presence of a large proportion of mixed alloys with very varied compositions implies that recycling by melting down unwanted objects and other scrap was a regular part of the process of making fourth-century artefacts.Footnote 94

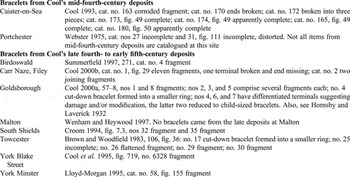

Some indications of the extent of recycling (through both melting, and modification of an extant object) from the very late fourth-century period onwards can be glimpsed by examining the completeness of artefacts in very late deposits. Cool usefully gathered together some material of the late to post-Roman transition period from military sites in northern Britain.Footnote 95 Although she did not examine the completeness of the metal artefacts, the lists of material provided enable easy access to the original site reports to make a closer examination of the copper-alloy bracelets from each of the late fourth- to early fifth-century deposits. This reveals that only damaged, modified and fragmentary bracelets are found in these contexts (Table 4). At Goldsborough and Towcester, it can be specified that these included cut-down bracelets. Crummy, who examined the late deposits at Silchester Insula IX, observed that here, too, only fragmentary bracelets were found. She also noted that the presence of fragments of bracelets could be an indicator of late deposits.Footnote 96 The fragmentary nature of the bracelets is possibly a general feature of material from occupation deposits and refuse dumps, some of which may have been deliberately discarded. In most site report catalogues, individual fragments of bracelets outnumber complete examples, and in Britain, large numbers of complete late Roman bracelets are only well-documented at cemetery sites, such as Lankhills,Footnote 97 Colchester Butt Road,Footnote 98 and Poundbury.Footnote 99 Yet the absence of complete unmodified bracelets does seem to be a characteristic of very late assemblages from occupation deposits. In contrast, slightly earlier assemblages of mid-fourth-century date do sometimes contain complete bracelets, for instance at Caister-on-Sea (see Table 4). In addition, at Reculver a complete bracelet was found in a context dating to c. a.d. 340–55.Footnote 100 Further complete examples from Reculver,Footnote 101 whose context dates could not be ascertained, also probably came from a similar period, given that the site is thought to have been virtually abandoned by the third quarter of the fourth century.Footnote 102 This comparison of mid-fourth- with late fourth- and early fifth-century evidence perhaps implies that bracelet recycling was intensifying in the latter period.

TABLE 4. Details of bracelets found in the late deposits of artefacts listed in cool 2000a

RECYCLING AS A PROBLEM OF SUPPLY

Re-use and recycling will always have been part of the object biographies of Roman material. Extending the use-life of artefacts through repairs and modifications might well be connected to particular types of site where Roman artefacts were less widely available; for instance, non-villa rural settlements,Footnote 103 where, individually, many rings made from bracelets occur. However, the evidence presented here suggests that bracelet recycling and re-use was particularly associated with the end of the Roman period in Britain, and was part of a wider phenomenon at that time. Pottery vessels repaired with rivets have been noted at Wroxeter's baths basilica complex in contexts of the fifth century and later,Footnote 104 a phenomenon also described by Cool.Footnote 105 Pottery spindle-whorls made from samian fragments, while not exclusive to the late period, are also sometimes found in very late deposits.Footnote 106 Coins clipped to remove silver fragments are a notable feature of late fourth- to fifth-century Britain — but not generally found in other provinces — and are one category of re-used object that has been examined in detail. It has been found that clipping only began when the supply of siliquae to Britain ceased and that the clippings seem to have been used to make contemporary imitations.Footnote 107 The degree of fragmentation of glass vessel sherds of fourth-century date also suggests glass recycling in the late Roman northern frontier area of Britain.Footnote 108 In an example more comparable to the bracelet evidence, White notes that those penannular brooches in very late contexts with the pin made from a different metal to that of the ring are repaired objects (for instance, a copper-alloy brooch with an iron pin), since the pin and ring of Roman penannulars were always made from the same metal.Footnote 109 Although White has not carried out a detailed study of this material, he does suggest that the curation of artefacts is very likely in the post-Roman period in Britain.Footnote 110

While Cool documents that copper alloy remained the most prevalent among the different materials from which bracelets were composed in the late fourth- to early fifth-century period — representing 59 per cent of her data sample — it has been shown above that the majority are only fragments which could well have been in the process of being recycled for a variety of reasons. The data, therefore, may not show a true picture of the relative popularity of the different kinds of materials used to make bracelets in this late period. It is evident that jewellery made of materials other than metals becomes more significant in the late Roman period. Bone bracelets, for example, increase proportionately in late fourth- to early fifth-century assemblages.Footnote 111 Cool's sample of finger-rings from site contexts of the same period, though small, suggested that black-coloured finger-rings, i.e. those made from jet, glass and shale, may have begun to supersede those extant in other materials.Footnote 112 Jet-working evidence has been found at some late sites, for instance GoldsboroughFootnote 113 and York Blake Street, listed by Cool.Footnote 114 (Both sites also produced cut-down bracelets, though the one at York is not from a datable context.Footnote 115 ) Indeed, of the excavated Roman sites that produced cut-down copper-alloy bracelets (and there are 50 sites where details of the site assemblage were available), 40 per cent also yielded bone bracelets and/or black finger-rings. At some sites, of course, bone artefacts will not have survived because of soil conditions, which would make this percentage more significant than it might appear. All this suggests that other materials were becoming more important at the time when the modified bracelets were being made or used. Cool suggests that preferences in material were related to an attraction for certain colours in this late period.Footnote 116 However, given the evidence assembled above, it might well represent instead a significant shift towards materials that were less technologically demanding, or more widely available, and indicate that even recycled copper alloy was becoming increasingly scarce or being set aside for particular uses.

The trends in recycling and re-use outlined above surely came about, at least in part, as a result of the collapse of craft industries and the breakdown of production and distribution systems at the end of the fourth century.Footnote 117 They also show a vigorous attempt to continue artefact production of a kind, and one that is very widespread, with much activity at this period. Yet the re-use of bracelets by cutting them down into smaller rings, or even through recycling by melting them down, may also have had symbolic aspects.Footnote 118 The re-used objects themselves will not have maintained the same range of meanings as the original artefacts.

INTERPRETING THE MEANINGS ATTACHED TO CUT-DOWN BRACELETS

Some of the instances of deposition of re-used items can be readily related to the continuation of Roman cultural practices, for instance their use as votives and as grave-goods. This is particularly apposite for the child-sized bracelets, which may have been made to conform to particular cultural requirements in the Roman West for children to be accompanied by jewellery at burial.Footnote 119 It is possible that the child-sized bracelets made from adult-sized originals represent a first phase of reworking, when complete examples were still known, but less common. Practices like these could be interpreted as a conscious attempt to perpetuate normal lifestyles and values in a period of turbulence; to overcome chronic insecurity through the attempt to maintain the usual social relationsFootnote 120 — though it is unlikely that the participants could have had any concept of how rapidly Roman culture would erode in subsequent years.

Yet even where context suggests the survival of Roman cultural practices, the development of new meanings can also be seen. If some of the child-sized bracelets were made especially for ritual deposition, there would be an attendant drift in meaning in that they would now be only symbolic ‘representations’ of the original artefacts. The possible finger-rings — which can be made from smaller sections than the child-sized bracelets — may represent for the most part a second phase of re-use when only fragments of bracelets were extant (although this cannot be distinguished in the imprecise date ranges available in Table 1, it is suggested by the very late deposits discussed above). They certainly show a greater divergence in meaning from the original artefacts, since in the Roman period bracelets were normally a feminine item, while finger-rings were worn by both sexes.Footnote 121 In the possible conversion of bracelets into finger-rings, therefore, the gendered connotations of the former category of object are apparently lost. The resulting rings could still be used in the perpetuation of Roman cultural practices, such as the wearing of finger-rings, and perhaps even for very specific cultural purposes, such as marriage rings. The reworked objects, however, diverge in appearance from Roman finger-rings and it seems likely that the artefact's potential to represent continuity would lessen.

In some periods and contexts, curated objects may have acquired high-status connotations through their scarcity value.Footnote 122 This could be a motivation for the modification of an extant artefact rather than recycling it through melting it down. In contexts in which the originals were no longer available, the objects might gain additional value as a result, making it undesirable to destroy them. However, this is unlikely as an explanation for the continued circulation of cut-down Roman bracelets, since many bracelets seem to have been recycled through melting down as well (see the evidence above for the increasing fragmentation of bracelets in late deposits, and that relating to late metalworking at Canterbury and Uley). Scarcity value might, however, have accrued for the rings made from re-used bracelets found on non-villa rural settlement sites, where Roman-style material culture assemblages would always have been limited,Footnote 123 and probably became virtually non-existent in the immediate post-Roman period.

RE-USE WITH PERSONAL, INDIVIDUALISED MEANINGS

Other effects of the ways in which the artefacts were modified might also produce new meanings. There are some notable differences from the original bracelets from which the modified objects were made, particularly in the treatment of decoration. There was apparently little attempt to achieve an overall symmetry in the design — a feature previously universal to bracelet decoration — through careful choice of which section to re-use (though it is possible that very carefully modified objects may have escaped identification as re-used). Rather than cutting off both ends to make a uniform strip, one terminal, usually the ‘eye’, is often left complete at the end of the strip. If the original bracelet had slightly tapering terminal sections, the use of one terminal would also mean that the modified object would narrow towards one end. In some cases, the object has been cut and the ends brought together carefully, but the appearance of others is much less regular. The strip may be bent round into one circuit or there might be overlapping sections creating a spiral effect. Each object is consequently unique and much more ‘personalised’ than the original bracelet — many of which occur in large numbers of virtually identical products — from which it had been made. Just as a surface patina may confer authenticity on valuable heirlooms,Footnote 124 the visible signs of re-use may reinforce coded, personalised meanings,Footnote 125 and it might even be suggested that the act of re-use itself was intentionally being displayed. The apparent disregard for aesthetics (compared with the norms evident for the original bracelets) possibly indicates that the conventional appearance of the object was now of lesser importance than its unique character and associations, perhaps with a previous owner or family. The conversion of adult-sized bracelets into child-sized bracelets is suggestive of the transfer of material between generations in some circumstances, for instance on the death of the adult wearer. The personal resonance of the objectFootnote 126 would perhaps have become more important in cases of this kind; though if the bracelet was given to a female child, its gender associations might be retained. Both the child-sized bracelets and the smaller rings were probably also circulating in different ways from the original artefacts from which they had been made. Roman bracelets were made in regional workshops, some of which appear to have had wide distribution systems.Footnote 127 In contrast to this, there is evidence of the re-used artefacts being made and used on the same site. Therefore, it would be much more likely that the previous, individualised life-history of the re-used artefact would be known and incorporated into its new identity,Footnote 128 and that its personal meanings would have superseded wider connotations.

HEIRLOOM OBJECTS?

To some users the cut-down bracelets may have had connotations of former times, recognisably part of an older suite of material culture. Artefacts can be ‘carriers of remembrance’, since their materiality in the present attests to the reality of the past or helps to establish a particular version of it.Footnote 129 Lillios proposes three criteria important in classifying an heirloom object, which may have been used as a locus of memory: (1) ‘portable’, (2) ‘inherited by kin’, and (3) ‘maintained in circulation for a number of generations’.Footnote 130 Over time, the artefact would become transformed into an heirloom, an uncommon and prized survivor of peoples and times past. Personal meanings would be superseded by the association of the artefacts with collective memory. Some of the child-sized bracelets suggest a context in which kin-inheritance could have occurred, fulfilling criterion (2); and the objects are obviously portable, meeting criterion (1); they could easily have been passed between individuals and been kept by them, and they are small and light enough to be easily carried on the person. Yet the inexactness of archaeological dating makes it difficult to establish whether the cut-down bracelets were in circulation for several generations. Some appear to have been used concurrently with surviving complete original copper-alloy bracelets and in one case the modified bracelet, in use alongside complete bracelets at Lankhills, had apparently entered the archaeological record by a.d. 370 (see Table 1). From the excavated data, many of the re-used items were apparently discarded, lost or otherwise deposited by the early fifth century (Table 1). Lillios reminds us that heirloom objects tend to enter the archaeological record when their meaning is lost,Footnote 131 and this could be the case here. It is possible that many of the objects were not in circulation for long enough beyond the period when they were (re)made to have been considered heirlooms and were not valued as such. Yet some examples of re-used bracelets do occur on fifth-century Anglo-Saxon sites, with later date ranges that could imply curation over several generations and hence an heirloom status for the objects in question. However, the evidence for the great majority of deposition dates suggests that their occurrence represents the redeposition of the already modified object in the Anglo-Saxon period, rather than the adaptation of the original bracelet at this time; see also specific evidence with regard to this from Shakenoak, below. Before addressing the question of ‘heirlooms’ with collective meaning, therefore, it will be useful to examine the Anglo-Saxon period material more closely.

CONTEXT ON ANGLO-SAXON SITES

As noted above, in addition to their occurrence on Roman sites, cut-down bracelets have also been identified at Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, in contexts of the fifth and early to mid-sixth centuries. Most of these sites were either on or in close proximity to Roman settlements (see Table 5) and are widely distributed ( fig. 10). The phenomenon of Roman artefacts occurring in Anglo-Saxon graves has been examined by White and more recently by Eckardt and Williams.Footnote 132 A wide range of different types of object are found. Many are coins, but dress accessories, such as brooches, are also well-represented. In both previous studies, it is noted that Roman artefacts of all periods can occur in graves throughout the Anglo-Saxon period and, indeed, Iron Age artefacts are not unknown. The conclusion drawn is that such Roman material culture is likely to have been rediscovered at Roman sites by later occupants or scavengers, rather than showing any direct continuity between the different communities.Footnote 133 Yet others have also noted that Roman artefacts, and bracelets specifically, do tend to occur in the earlier, fifth-century graves.Footnote 134 Examples of sites that display evidence of continuity throughout the transitional phase are also increasingly apparent, for instance Wasperton, Mucking, Orton Hall Farm,Footnote 135 though to what extent these show a continuity of population rather than of occupation is currently being debated. Generalisations about the wider presence of Roman artefacts in Anglo-Saxon graves may have obscured particular patterns in relation to very late to post-Roman objects in the earliest graves on Anglo-Saxon sites. Therefore, grave contexts and wider site assemblages need to be taken into account before drawing any conclusions as to whether — when considering cut-down bracelets in Anglo-Saxon cemeteries — there is evidence of artefacts continuing in circulation, with the possible implication that they may have been handed down as heirlooms, or conversely that they were objects re-entering the pool of circulation through rediscovery.

FIG. 10. Distribution map of Anglo-Saxon cemeteries with graves that contained cut-down Roman bracelets.

TABLE 5. Grave assemblages and other site details for anglo-saxon graves containing roman bracelets made into smaller rings

A summary of the grave contexts is provided in Table 5. While there is not complete uniformity in the positions in which the artefacts have been placed in the grave, a general trend can be suggested. Nine of the rings from seven graves were found grouped together with other objects at or near the waist. These groups of objects have been reconstructed by the excavators as ‘bag groups’, objects thought to have been placed in bags or suspended together at the waist (additional evidence of the ‘bag groups’ sometimes includes artefacts, such as ivory suspension rings, leather fragments, and the like).Footnote 136 The (reconstructed) bag groups commonly contain in addition the following types of objects: naturally occurring objects, for example, iron pyrites, a quartzite pebble, a fossil; Roman coins; and other ring-shaped objects. The Roman coins included both late and earlier issues. While one of the rings made from a cut-down bracelet from Empingham (Grave 6) was found on a finger-bone, the position of the other examples — from ?Eriswell, and one of the Mucking examples, a child-sized bracelet found in the fill of Grave 623 (unfortunately the age and sex of the occupant were uncertain), and Reading (Earley) — were not specifically noted.

Meaney's study of Anglo-Saxon amulets found that Roman objects sometimes appear to have been deposited in a bag at the waist along with other items that would have been regarded as lucky or protective, for instance, beaver teeth, fossils, etc.Footnote 137 Ring-shaped objects are also apparently common in these assemblages, suggesting that the shape was important in giving the object meaning.Footnote 138 Exactly the same trends are evident in Table 5. The presence of other ring-shaped objects in six out of the seven graves suggests, therefore, that the cut-down bracelets may have been selected primarily for their shape.

The juxtaposition of the cut-down bracelets with other found objects, including Roman coins, implies that they are likely to have been rediscovered at the site or near by. Nor were these the only graves at the respective sites to contain Roman artefacts. Apart from Eriswell, where the available data are fragmentary, and Westgarth Gardens, Roman artefacts were found in other graves as well as in those containing the modified bracelets. These artefacts were mostly third- and/or fourth-century coins, though they also included early Roman brooches, Roman pottery, and late fourth- to fifth-century belt fittings. Where the position was recorded, artefacts were generally found in bag groups, hanging on chatelaines or necklaces, but also elsewhere in the grave; belt fittings were apparently worn at burial. The variety of date ranges represented, including early Roman material, confirms that most of the artefacts are more likely to have been rediscovered rather than curated. The belt sets could form an exception to this, since they are of very late stylistic date — including types continuing into the fifth century — and placed in the grave in a position which was also the norm in the late Roman period.

Westgarth Gardens is an interesting exception to the usual pattern and is the one cemetery not in close proximity to a Roman site. The burial with a cut-down bracelet is also the only cremation among the sample. These differences may be connected in some way, but without further examples this is uncertain.

A more detailed examination of the three sites where cut-down bracelets were found in both Roman and Anglo-Saxon contexts is required. At Orpington, in addition to the grave-find noted in Table 5, a ring made from a re-used bracelet was found at the Bellefield Road Roman site (Trench 1, layer 2).Footnote 139 Unfortunately, it came from an undated context, but the excavators suggest that the Roman site was abandoned c. a.d. 370.Footnote 140 The Anglo-Saxon cemetery at the site includes graves with early objects, such as a Quoit-brooch-style buckle (first half of fifth century) in Grave 51Footnote 141 and a continental Roman glass bracelet of early to mid-fifth-century date found in Grave 2, while the grave assemblages overall suggest a starting date of the second half of the fifth century.Footnote 142 Roman objects, mostly third- and fourth-century coins, were found in several graves. The evidence suggests a gap in occupation between the Roman and Anglo-Saxon periods, though this may have been for a relatively short period, depending on how the dating evidence is interpreted. It is noted that many Roman objects were found in the Anglo-Saxon layers.Footnote 143

An example of a ring made from a cut-down bracelet at Shakenoak Roman villa,Footnote 144 which was threaded onto an Anglo-Saxon girdle-hanger ( fig. 11), is of particular note.Footnote 145 (Anglo-Saxon parallels for the girdle-hanger can be readily suggested.Footnote 146 ) It is a crucial piece of evidence for re-use, since the ring had apparently been made from a section of bracelet of which a remaining part was also found at the site.Footnote 147 The remaining piece of bracelet was found in a deposit dated to a.d. 350 (see above), confirming that the ring had been made much earlier than the period at which it was deposited. The association of this item as part of a linked collection of rings of various sizes suggests perhaps that it was found and selected primarily because it was ring-shaped, rather than being an heirloom object. There is evidence of continuity at the site from the late Roman phases into the fifth century and later, including late Roman belt fittings found both in the final phases of the villa site and in the post-Roman enclosure ditch fill (Period F3 deposits, which date from the mid-fifth or earlier to mid-sixth century). The girdle-hanger, however, comes from a later deposit in the ditch fill (Period F4), with a suggested date range of mid-sixth to seventh or early eighth century.Footnote 148

FIG. 11. Anglo-Saxon girdle-hanger from Shakenoak, including a ring made from a cut-down Roman bracelet (Ashmolean 1969.311).

At Mucking, the contexts of the two examples found in Anglo-Saxon gravesFootnote 149 exhibited clear differences from the cut-down bracelets found in Roman graves.Footnote 150 While the two Roman examples from a secure context (Grave 30) were at the foot of the grave, the examples from the Anglo-Saxon cemetery were, respectively, from the grave fill and part of a possible bag group. The Romano-British graves are not dated closely in the site report, but both the cut-down bracelet in Grave 15 and one of the cut-down bracelets in Grave 30 are multiple motif bracelets. These only occur in deposition contexts from a.d. 350 onwards, with many being deposited in the early fifth century (see above). Dates for these graves of c. a.d. 350 onwards can, therefore, be suggested. Turning to the Anglo-Saxon graves, Grave 623 — containing only a knife, and a cut-down bracelet in the fill — is described as ‘phase uncertain’, while Grave 878 — with a cut-down bracelet formed into a ring and deposited as part of a bag group — is dated to the late fifth to early sixth century (Phase 1aiii). Graves with bracelets (not cut-down ones) possibly from the intervening period Phase 1ai/aii (early to mid-fifth/mid- to late fifth century) show bracelets worn at burial.Footnote 151 The divergence in treatment, which is probably chronological, suggests an attendant drift in meaning.

Examination of the presence of other definitely Roman or Roman-derived artefacts in graves at MuckingFootnote 152 indicates that there are two principal groups and evidence from the other cemeteries (see above) suggests this may be a more widespread pattern.

1. Artefacts with a fifth-century stylistic date worn at burial.Footnote 153 These comprise a Quoit-brooch and continental-style bracelets, plus Quoit-brooch-style buckles (Cemetery I, Grave 117, no. 1 (to right of waist area) and Cemetery II, Grave 823, no. 4a); double-horsehead buckle (Cemetery II, Grave 987, no. 4); dolphin buckle with curled tail (Cemetery II, Grave 989, no. 8); and continental fixed-plate-type buckles (Cemetery I, Grave 91, no. 1 and Cemetery II, Grave 979, no. 7). According to the site report these all came from the earliest phase of the cemetery, 1ai/aii which dates to early to mid-fifth/mid-to late fifth century. Since the dating itself is heavily dependent on them, there is some risk of circularity here, though there were certainly no later artefacts found in these graves.

2. Artefacts of first- to fourth-century stylistic date found from Phase 1aiii (late fifth to early sixth century) onwards — predominantly melon beads, coins and brooches — continue to be deposited throughout the sixth century, and are mostly found as part of bag groups (see Table 6).

TABLE 6. Other roman artefacts of first- to fourth-century date found in graves at mucking anglo-saxon cemetery (all references are to Hirst and Clark Reference Hirst and Clark2009)

Grave 878, with the cut-down bracelet, falls into the latter rather than the former group. Indeed, it contained one of the other Roman artefacts found at the site, a pierced third-century Roman radiate coin possibly strung on a bead necklace (see above).

Given the context of re-use of Roman artefacts of varied date in later phases, rather than the earliest phase, it seems more likely that at Mucking the cut-down bracelets were rediscovered objects rather than heirlooms, especially when the cut-down Roman bracelets found in the fills of undatable graves are taken into account. These presumably represent the scatter of late Roman residual material on the site and near by in the Anglo-Saxon period.

SUMMARY OF TRENDS IN THE ANGLO-SAXON PERIOD EVIDENCE

The possibility of continued circulation and the deposition of cut-down bracelets as inherited heirloom items in Anglo-Saxon period graves cannot be excluded altogether. However, the balance of evidence — both from the bag groups in the graves and from more detailed examination of the material at Mucking, Orpington and Shakenoak — seems to suggest that there is indeed a gap, during which time most cut-down bracelets moved out of circulation, before their subsequent rediscovery and the attribution to them of new meanings. The evidence from Roman contexts also supports this, since the later fifth- or sixth-century deposits on Roman sites that contain cut-down bracelets are redeposited dumps of material (see Table 1), which suggests that the date when many of the artefacts were lost or discarded was not later than the early fifth century. From the presence of earlier Roman material at many of the relevant sites, it can be seen that scavenging of Roman sites is likely to have occurred.Footnote 154 Disturbance of the most recently deposited layers would naturally produce late Roman artefacts. From analysis of metal objects at West Heslerton, it has been suggested that many Anglo-Saxon period objects were made from recycled Roman artefacts,Footnote 155 which must have been sourced in a similar way. At Wasperton, an increase in the use of mixed alloys may also indicate that there is a greater degree of recycling (presumably including many Roman objects) in the early sixth century,Footnote 156 rather than in the earliest phase. This fits with the evidence, presented here, that the Roman objects discussed (in Group 2, above) became the focus of attention after the earliest Anglo-Saxon phase.

The most significant conclusion from consideration of Anglo-Saxon period sites, however, is that a wholly different set of cultural norms is in operation. From the deposition contexts of these modified bracelets, it can be seen that the general trend of use is now as amulets, rather than as jewellery. A break in use apparently contributed to a complete reinvention of meaning.Footnote 157 Cut-down bracelets occur in Anglo-Saxon period graves from the late fifth and sixth centuries with the possible connotations of exoticism and magic.Footnote 158 Gosden and Marshall have suggested that a disjunction in meaning can occur when artefacts are taken out of their original context,Footnote 159 and this is a good example.

CONCLUSIONS

This study has clearly illuminated the divergent life histories of Roman bracelets. Following its period of manufacture and initial use, a Roman bracelet could be used as a special deposit, for instance at a temple or in a grave as at Woodeaton or Colchester. It could be melted down (inevitably harder to document, but likely from the increasing fragmentation of bracelets and from contextual evidence at Canterbury and Uley). It might be lost or discarded or it could be cut-down into a child-sized bracelet or a finger-ring (179 examples are listed in Appendix 1). Exactly the same processes might then apply to the cut-down object. In each case, the decision to maintain, discard, deposit or transform the object would be made in relation to the perceived value and meaning of that particular object at that specific time, which might be different to those of another, similar object. With the problems inherent in archaeological evidence, it is unlikely that we could recover more than a fraction of this meaning, and we glimpse each individual artefact only at the particular life-stage where it has entered the archaeological record (see fig. 12). Yet from their deposition and wider intra- and inter-site contexts, some recurring trends can be seen in the treatment of the objects, which suggests the existence of wider cultural norms in the ways that many of these artefacts were regarded. Documentation of dating and wider contextual information gives an insight into how these norms lapse and are replaced by others in a longer process of transformation. These more generalised trends can be summarised as follows.

FIG. 12. Diagram showing the possible life histories of Roman bracelets.

It is probable that modification of Roman bracelets into smaller sized rings occurred throughout the Roman period. The few examples of early Roman-type bracelets in the data sample suggest as much and judging by the site-type profiles, this sort of re-use may have been particularly prevalent, regardless of date, on rural sites for various reasons, such as less access to Roman-style objects. Yet it is apparent that the vast majority of this sort of recycling activity took place in the late Roman period. To some extent this appears to have been a pragmatic attempt to extend the use-life of artefacts. In the initial phase, it is suggested that, through the connotations of their form and decoration, re-used objects would mostly have had similar uses and meanings to the original bracelets — as dress accessories worn as gender signifiers, and to construct other aspects of status and identity.Footnote 160 In support of this, it has been shown that similar to other Roman dress accessories, they were used in grave assemblages and as votive offerings and that some, at least, existed in use alongside unmodified Roman bracelets. In this way, the artefacts were used, consciously or not, to perpetuate a Roman way of living. Yet differences in appearance, in availability, and in patterns of production and circulation, as well as changing gender associations (each documented and discussed in detail above) will have meant that, although similar uses and meanings may have persisted to an extent, a range of divergent meanings will also have developed, in which the personalised and individual associations of the artefacts may have become paramount. Following the loss of these personal meanings, evidence from their deposition suggests that many of the artefacts became obsolete. More generally, it has been shown here that there is a lessening of significance of metal dress accessories in the construction of a Roman-style feminine gender identity in the late to post-Roman transition period. Such a display of feminine identity may have become less important in itself, or was perhaps perpetuated through other material, but whatever the case there is a drifting away from late Roman social norms. Following this, the evidence indicates that those rings made from cut-down bracelets as a result of rediscovery on Roman sites in the Anglo-Saxon period were primarily viewed as magical and protective objects.

WIDER CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE STUDY OF THE LATE TO POST-ROMAN TRANSITION PERIOD AND BEYOND

Studies of other late fourth-century object types have focused on production, distribution and related issues,Footnote 161 on military style artefacts,Footnote 162 and on the characteristic artefacts to be found in late assemblages.Footnote 163 A recent edited volume on material culture in the fourth- to fifth-century transition period contributes much that is valuable, but on similar themes, though also taking in the categories of pottery, glass vessels and coinage.Footnote 164 The study presented here, however, contributes detailed evidence of quite a different kind: besides illuminating some of the ways in which the meaning of artefacts may have been changing, it documents the extent and nature of the recycling of bracelets in the late fourth- to early fifth-century transition period. The distribution maps show that recycling of Roman bracelets occurred wherever these artefacts were available. Wider evidence from consideration of specific sites and assemblages suggests that this recycling included both the remodelling of extant artefacts, and their melting down and recasting into new objects. Together with glimpses of other recycled and repaired objects in the same period, and the increasing use of non-metal raw materials — based on Cool's work,Footnote 165 — a picture evolves of a transition period in which newly smelted metal was becoming much less widely available and metal artefacts much scarcer. As a result, artefacts may have been available in a much more restricted and localised way. If aspects such as completeness, repair, and modification (which have not been considered in any detail for most Roman artefact types) were documented and examined in more depth — especially in relation to the types and dates of contexts in which modified, repaired or fragmentary artefacts occur — this picture would become still clearer.

Evidence for continuity between the latest Roman period and the earliest Anglo-Saxon period deposition is bedevilled by problems, such as the widespread shift to unfurnished burial at the end of the Roman period and the difficulties in dating. Even taking this into account, however, the evidence has shown that there seems to be a disjunction between the uses and meanings of the objects from one period to another. This implies more of a loss than a perpetuation of cultural traditions, perhaps during a period in the earlier or mid- to late fifth century when the artefacts fell out of use. The importance can be seen here of considering detailed patterns of use and deposition of Roman artefacts in Anglo-Saxon graves, in which Roman-style artefacts that were still available in the fifth century must be distinguished from those that were apparently rediscovered.

Finally, in relation to the transition period, this study shows the importance of bringing together fifth-century material traditionally separated into the different period-specific disciplines of Roman and Anglo-Saxon archaeology. Collins and Gerrard call for an integrated approach,Footnote 166 and the current study has shown how important this is for artefacts which have a use-life phase in both periods. Without this, the sharp divergence in use and meaning from one period to another would be missed. Also, the lack of continuity could only be an assumption, rather than, as here, documented through detailed consideration of evidence across the fifth century and beyond.

APPENDIX 1. COMPLETE LIST OF ROMAN BRACELETS CUT DOWN INTO SMALLER RINGS BY SITE

Examples where the identification is probable rather than certain are marked (P). PAS = Portable Antiquities Scheme; LAARC = London Archaeological Archive and Research Centre.

APPENDIX 2. SITES WITH FLATTENED OR DISTORTED ROMAN BRACELETS

The sites where Roman bracelets that have been made into smaller rings are also present are starred *. PAS = Portable Antiquities Scheme; LAARC = London Archaeological Archive and Research Centre; AHDS = Arts and Humanities Data Service.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS