Introduction

This research project explores the role of nature connection practices in making visible the interconnectedness of humans, place and the more-than-human world at an outdoor place-responsive programme for children called Earth Kids. Such programmes are significant due to the ecological crisis we are facing as a result of human consumption and extraction of the Earth’s resources. The root of this crisis is Western understandings that see humans as separate to the natural world (Plumwood, Reference Plumwood, Adams and Mulligan2003). In response, educational approaches are required that respond to these escalating challenges in new ways that recognise human entanglement with the rest of nature (Somerville and Green, Reference Somerville and Green2015). To contribute towards addressing these challenges, posthuman educational theory and practice is drawn upon. In particular, common worlds research, including some which has a focus on place, is explored. The significance of this research is that it: challenges the human/nature binary; pays attention to the ways in which humans affect and are affected by more-than-human others with whom we are entangled and interdependent; recognises more-than-human agency; explores how humans can think with and learn with the more-than-human world; recognises place as pedagogical; and acknowledges the legacies and implications of ongoing colonialism (Gannon, Reference Gannon2017; Taylor & Pacini-Ketchabaw, Reference Taylor, Pacini-Ketchabaw, Pacini-Ketchabaw and Taylor2015a, Reference Taylor and Pacini-Ketchabaw2015b; Taylor, Reference Taylor2017).

The Earth Kids programme is run at Northey Street City Farm (NSCF), a 6-acre permaculture and sustainability educational centre in the inner-north of Brisbane, on the unceded land of the Yuggera and Turrbal peoples. While significant areas of land have been returned to First Nations people in Australia in recent years, very little of that land is in urban areas (Blatman-Thomas and Porter, Reference Blatman-Thomas and Porter2019), inhibiting First Nations people from land sovereignty in Brisbane and other urban Australian areas. Adjacent to the city farm is a narrow bushland area along Enoggera Creek, maintained by a local bushcare group and where a range of Earth Kids activities are held. Earth Kids is a programme for primary school-aged children, run as both a school holiday and homeschool programme. The author of this article is an outdoor educator of settler descent who developed Earth Kids with the intention of creating a programme for children that fosters a love and care of place and relationships with the more-than-human world. The programme takes a place-responsive approach, which emphasises the embodied experiences of learners themselves, located in the learners’ local environment and involving reciprocity between people and place (Mannion & Lynch, Reference Mannion, Lynch, Humberstone and Henderson2016; Somerville, Reference Somerville2010; Wattchow & Brown, Reference Wattchow and Brown2011). This article focuses on some of the nature connection practices used in the programme, which are conducted alongside other activities including gardening, bushcraft skills, games and learning from guest presenters including First Nations people.

This research aimed to provide insights to inform programmes using a nature connection model (Young, Haas & McGown Reference Young, Haas and McGown2010), nonformal educational programmes such as forest schools and classroom teachers who engage in outdoor learning. Practical advice to support practitioners to enact pedagogies is uncommon in posthuman educational research (Stevenson, Mannion & Evans Reference Stevenson, Mannion, Evans, Cutter-Mackenzie, Malone and Hacking2020), and this is a gap that this article addresses. While common worlds approaches sometimes suggest ways for educators to actualise pedagogies (eg. Nxumalo, Reference Nxumalo, Pacini-Ketchabaw and Taylor2015; Pacini-Ketchabaw, Reference Pacini-Ketchabaw2013), this research is generally focused on research in early education centres. The exploration of nature connection practices in this paper may provide educators with concrete approaches to incorporate into place-responsive programmes that enable an awareness of the interconnections and interdependence of humans, place and the more-than-human. Additionally, in recognition that there is a paucity of empirical research ‘that includes data from children’ (Somerville & Green, Reference Somerville and Green2015, p. 17) in educational research, this study includes perspectives of the children themselves. Children’s representations of solo experiences in place through story, writing, drawing and the collection of items from nature were analysed to create narrative summaries, which are reflected on and presented with some of the children’s journal entries. In the discussion and findings, nature connection practices are explored in terms of: embodied and generative place encounters; emergent relationships with place and the more-than-human world; the ways they foster learning with place; and (re)storying place relations. Firstly, research relating to the significance of place in education and nature connection practices is explored.

Place and Education

There are a range of approaches to educational research and practice that use place as a central organising framework. Three types of place-based education approaches are distinguished by Seawright (Reference Seawright2014): ‘liberal place-based education’; ‘critical place-consciousness’; and ‘indigenous epistemologies and models of education’. He argues that while liberal place-based education challenges the dominance of humans over nature, it fails to take into account the political dimensions of place (p. 561). In contrast, Greenwood’s theory of critical place-conscious education emphasises place as ‘profoundly pedagogical’ (Reference Greenwood, Stevenson, Brody, Dillon and Wals2013, p. 93), bringing together cultural and ecological considerations to ensure care for both land and people. From Indigenous perspectives, Land Education is an emerging field of scholarship which aims to centre Indigenous understandings and critique ongoing settler colonialism (Bang et al. Reference Bang, Curley, Kessel, Marin, Suzukovich and Strack2014; Calderon, Reference Calderon2014; Tuck, McKenzie & McCoy Reference Tuck, McKenzie and McCoy2014). These scholars call on place-based education practitioners and scholars to do more to acknowledge that land continues to be Indigenous, to reconsider settler identities in relation to place, to privilege Indigenous realities and support Indigenous sovereignty of land.

Closely aligned with critical place-conscious education is place-responsive education (Tooth & Renshaw, Reference Tooth, Renshaw, Cutter-Mackenzie, Malone and Hacking2020; Wattchow & Brown, Reference Wattchow and Brown2011), which is the approach taken at Earth Kids. Place-responsive approaches recognise that ‘people and place are always entangled in ongoing events that are reciprocal in nature’ (Mannion et al., Reference Mannion, Lynch, Humberstone and Henderson2016, p. 92). Dawson and Beattie (Reference Dawson and Beattie2018) argue that what distinguishes place-responsive education is that place is considered to have agency and therefore be an active participant in teaching, learning and knowing. That place has agency and can therefore be a co-shaper and co-teacher of the curriculum (Dawson & Beattie, Reference Dawson and Beattie2018) is a significant consideration in my research. Somerville proposed ‘an enabling pedagogy of place’ (Reference Somerville2010, p. 338) which has most influenced my thinking on place-responsiveness. The elements of this pedagogy are: ‘our relationship to place is constituted in stories (and other representations); the body is at the centre of our experience of place; and place is a contact zone of cultural contact’ (p. 335). While this article relates particularly to the first two of these elements, it is important to recognise the significance of the contact zone, particularly in the context of the programme being held on land on which settler colonialism is ongoing (Tuck et al., Reference Tuck, McKenzie and McCoy2014). NSCF is an organisation which acknowledges this reality and is committed to working in solidarity with First Nations people, Footnote 1 though I acknowledge there is considerable work required to respond to the calls of Land Education scholars as previously discussed.

Place-responsive pedagogies are aligned with posthuman thinking and theorising (Stevenson et al., Reference Stevenson, Mannion, Evans, Cutter-Mackenzie, Malone and Hacking2020) which also aim to decentre humanity and disrupt the binary of nature/culture that is present in Western thinking (Somerville & Green, Reference Somerville and Green2015). There are many forms of posthumanism (Ulmer, Reference Ulmer2017); one area that has relevance to this project is common worlds theory and practice. Common worlds researchers have adopted Latour’s ‘common worlds’ term to inspire openness to discovering ‘more about where we are, and who and what is there with us’ (Taylor & Giugni, Reference Taylor and Giugni2012, p. 110) in the entangled and interdependent common worlds we share with others, both human and more-than-human (Taylor & Pacini-Ketchabaw, Reference Taylor and Pacini-Ketchabaw2015b). Place is considered important here, in recognition that common worlds are located in places which are dynamic, relational (Taylor & Giugni, Reference Taylor and Giugni2012) and have agency (Pacini-Ketchabaw, Reference Pacini-Ketchabaw2013). Rather than occurring between unchanging subjects, relations are considered ‘generative encounters’ which enable a process of ‘becoming with’ the world (Pacini-Ketchabaw, Reference Pacini-Ketchabaw2013, p. 112). Underlying this work is a recognition of the importance of an ethics of living with more-than-humans that allows for all species to flourish, requiring us to pay ‘attention to the mutual affects of human-nonhuman relations’ (Taylor, Reference Taylor2017, p. 1455). Affect in this sense describes changes in intensities and resonances that occur between bodies that are both human and more-than-human (Nxumalo & Villanueva, Reference Nxumalo and Villanueva2019). Pacini-Ketchabaw, Taylor, and Blaise (Reference Pacini-Ketchabaw, Taylor, Blaise, Taylor and Hughes2016) argue that ‘we cannot decentre the human without learning to be affected by the world that we also affect’ (p. 158). They propose that this requires us to use our senses to attune to our own and more-than-human bodies. In this way we may explore the possibilities of thinking with, learning with and feeling with the more-than-human world (Gannon, Reference Gannon2017; Taylor, Reference Taylor2017). Within common worlds, human and more-than-human others are all recognised as having agency, enacted ‘in asymmetrical and uneven ways’ (Pacini-Ketchabaw & Taylor, Reference Pacini-Ketchabaw, Taylor, Pacini-Ketchabaw and Taylor2015, p. 59).

Nature Connection Practices

The nature connection practices used at Earth Kids were inspired by Coyote’s Guide to Connecting with Nature (Young et al., Reference Young, Haas and McGown2010). This handbook provides outdoor educators with a place-based model for learning (Grimwood, Gordon & Stevens Reference Grimwood, Gordon and Stevens2018) and has inspired many outdoor education initiatives throughout Australia, North America and Europe. The nature connection practices explored in this research project and which are core practices at Earth Kids are: magic spot; solo wandering; story-sharing; journalling; gathering and nature names. However, it must be acknowledged that the term nature connection can be viewed as problematic in that it may imply that humans and nature are separate. Ironically, these practices can highlight the very opposite — that humans are nature and are entirely entangled with the more-than-human world (Rautio, Reference Rautio2013a). The exploration of these practices in this study aims to highlight the ways in which they could reveal this interconnectedness.

The core routines of nature connection, as outlined in Coyote’s Guide, are foundational learning habits ‘to be continually practised over time’ (Young et al., Reference Young, Haas and McGown2010, p. 291). Of these routines, the sit spot, a solo experience in nature, is seen as the keystone routine. The sit spot, called a magic spot (Van Matre, Reference Van Matre1990) at Earth Kids, involves finding an outdoor place to sit in and return to, in order to discover an intimate knowledge of a place (Young et al., Reference Young, Haas and McGown2010). Sitting alongside the sit spot is the story of the day (or story-sharing), which involves exchanging stories about each other’s experiences. Wandering involves moving ‘through the landscape without time, destination, agenda or future purpose’ (p. 53). While in the Coyote’s Guide wandering is suggested as a practice to do with other people, at Earth Kids we have been including short solo wanders. Journalling, using drawing and /or words to reflect on nature experiences, is another routine which Young et al. (Reference Young, Haas and McGown2010), view as training ‘the mind to pay attention’ (p. 64). These four routines — of thirteen described in the Coyote’s Guide — are explored in this paper due to their value in making visible human, place and more-than-human entanglement. Over time, the way in which these practices are integrated at Earth Kids has evolved into a unique approach which involves either a magic spot or solo wander (ie. a solo immersive experience), followed by representing these experiences through nature journalling and then story-sharing. The solo experience also includes an invitation for children to collect items that interest them, a practice I term as gathering. Items collected as part of this practice are often shown and discussed in the story-sharing time.

The importance of embodied learning is emphasised by researchers taking place-responsive approaches (Somerville, Reference Somerville2010; Tooth et al., Reference Tooth, Renshaw, Cutter-Mackenzie, Malone and Hacking2020). Research into the experience of children experiencing solo nature connection practices is limited. A study of instructors in nonformal outdoor nature connection programmes for children in Toronto based on the Coyote’s Guide found that instructors working there valued the immersive experiences which fostered ‘embodied, affective, and emplaced experiences’ (Grimwood et al., Reference Grimwood, Gordon and Stevens2018, p. 212). The instructors saw sit spots as enabling children to ‘still minds and bodies’ and to understand ‘how nature works’ (p. 212). Significantly, the authors of the study point out that some of the instructors’ narratives conveyed the problematic idea that humans are separate to nature. Magic spots are part of a ‘slow pedagogy’ approach at an Outdoor Environmental Education Centre in Brisbane, where school children visit for excursions (Rowntree & Gambino, Reference Rowntree, Gambino, Renshaw and Tooth2018). The practitioners propose that magic spots enable their students to be present in the forest, to process their experience and bring together their learning. Notably, solo wandering as a practice is not apparent in the literature relating to outdoor learning, which instead has tended to focus on sedentary solo practices like magic spots.

Researchers taking place-responsive approaches also emphasise the significance of stories and other place representations in forming relationships to place (Somerville, Reference Somerville2010; Tooth et al., Reference Tooth, Renshaw, Cutter-Mackenzie, Malone and Hacking2020). In terms of stories, Rowntree et al. (Reference Rowntree, Gambino, Renshaw and Tooth2018) emphasised the importance of ‘the sharing circle’ with the students after the magic spot experience, which they say ‘creates a systems sense of the forest’ (p. 82) for the children. This approach of bringing the magic spot together with story-sharing is similar to the approach taken at Earth Kids, without the journalling aspect in between. Journalling is a practice used in many place-based or place-responsive educational programmes as a means of reflection following immersive experiences in nature. Two are reflected on here which are significant due to their insights into how place representations can enable embodied knowing and foster more-than-human and human relations. Somerville (Reference Somerville, Somerville and Green2015) analysed ‘place learning maps’ — including images and text similar to the Earth Kids journal content — which were created by primary school students after spending a day at a wetland site. She concluded that these ‘maps’ enabled students to express a new and embodied knowing ‘where the materiality of place and the bodies of the children are integrated into symbolic forms of representation’ (p. 83). Nxumalo and Villanueva (Reference Nxumalo and Villanueva2019) used journalling for kindergarten children to reflect on their place learning encounters by a creek. They argue that drawing helped the children to slow down, attune to place with their senses and reflect on their encounters. They see it as part of enacting ‘affective pedagogies’ to support relations with the more-than-human world and ‘think with water’.

An additional practice used at Earth Kids is nature names. This involves each participant choosing a nature name (Young et al., Reference Young, Haas and McGown2010, p. 348) from a selection of native plants or animals that live in the local area and that fall under a central theme like ‘trees’, ‘birds’, or ‘animals’. Given that the nature names are local and found at the site, children are likely to encounter their nature name over the course of the programme. At the beginning of each programme the children choose their nature name from a group of wooden badges that have a plant or animal written on the underside (see Figure 1). Several activities are incorporated into each programme that encourage the children to learn more about these more-than-human others and build an embodied relationship with them. In the programme the study was based on, the children chose tree names native to south-east Queensland, all of which grow at the site. Nature names are used in many nature connection programmes, in particular those inspired by the Coyote’s Guide; however, they rarely feature in educational academic literature. While nature names are not given great emphasis in the Coyote’s Guide, they have become a central component of the Earth Kids programme.

Figure 1. An Earth Kids nature name badge.

Informed by this background on nature connection routines, as well as place and education, this project aimed to explore the role of nature connection practices in making visible the interconnectedness of humans, place and the more-than-human in a place-responsive outdoor education programme. One aspect of this is exploring how these practices can support the children to recognise themselves not as separate to place and more-than-human others, but as entangled with them. Furthermore, in recognition ‘that educators, students, and place are all agentic components of the system, all causing change and being changed simultaneously’ (Dawson & Beattie, Reference Dawson and Beattie2018, p. 130), this paper explores how all of us, including humans, more-than-human others and place itself affect and are affected by enacting these nature connection practices, and how the practices can play a role in decentring humans.

Earth Kids Case Study

A qualitative case study approach was used, taking inspiration from posthuman approaches that think with the more-than-human and place (Nxumalo, Reference Nxumalo, Pacini-Ketchabaw and Taylor2015; Pacini-Ketchabaw, Reference Pacini-Ketchabaw2013; Somerville, Reference Somerville, Somerville and Green2015). I wanted to explore what might result when I attempted to think with place, as well as learn with place, and invited the Earth Kids participants to also do so by using the practices. Following ethical approval, consent was sought from both parents and the children themselves to participate in the study. The human participants were eight children aged six to eleven years enrolled in the Earth Kids homeschool programme, as well as myself as a practitioner researcher, entangled with the children, place and more-than-human others. Alongside us, other participants included Enoggera creek, trees, snails, crabs, fairy wrens, seeds and sticks, amongst many other more-than-human others.

Two research sessions were held in the bushland area adjacent to NSCF, focussing on the nature connection routines. Each of these sessions involved: a brief meditation to engage the senses; a 15-minute solo experience, entailing a wander in the first session and magic spot in the second session a fortnight later; 15 minutes of writing and drawing time; and a 15–20 minute ‘circle-time’ focus group in which the children shared their experiences. This excerpt from the first narrative summary created as part of the data analysis process describes the first circle time session:

On the bank of Enoggera Creek, under a large fig tree, a group of children, parents and Earth Kids staff sit together for circle time sharing. The children have just gone on solo wanders, through the trees and along the creek, their bodies, their curiosity and encounters with more-than-humans drawing them along. After the wander, the children spent time capturing their experience in their nature journals. Now, as we sit together I ask the children questions about their solo experiences, which they share with the group, and invite them to share what they wrote and drew in their journals and show any items they gathered.

The two data collection methods — focus groups and analysis of artefacts produced or collected by the children — are aligned with the nature connection practices of story-sharing and journalling, which are usually done after a solo experience at Earth Kids. Both the stories shared in the ‘circle time’ focus groups and other artefacts are different means of representing relationships to place (Somerville, Reference Somerville2010). In this way they are both pedagogical and methodological tools. Additionally, analysis of the children’s journal entries or items that they gathered provided a way of communicating the children’s relationships with place in nonrational ways of knowing (Wattchow & Brown, Reference Wattchow and Brown2011) and communicated an ‘embodied knowing’ of place (Somerville, Reference Somerville, Somerville and Green2015, p. 83).

While the methodological approach was relatively conventional, it also drew on posthuman approaches in that: flexibility and openness to emergence in the process was allowed for (Ulmer, Reference Ulmer2017); the richness of the data rather than reducing it through coding was preserved (MacLure, Reference MacLure2013); and thinking with place was incorporated through the process. After the sessions in which the data was collected, analysis questions about the artefacts (audio transcriptions, journal entries, images of gathered items and worksheets) were developed. Some of these analysis questions included: ‘what did the child choose to share in the initial sharing and what stands out from this?’; and ‘how is the interconnectedness of human, place, and the more-than-human visible here?’. Responses to these questions were made, bringing together each child’s story-sharing with their journal entry and gathered artefacts, enabling me to form a mental picture of the children’s experiences. Based on this data, a ‘chapter’ in the form of a narrative summary was constructed for each session, excerpts of which are included above and in the findings. An emergent aspect of the approach was walking in the area the programme was held at various points through the data analysis and writing process, fostering thinking with place. This practice of walking provided me with an embodied experience of place, encountering many of the more-than-humans the children had included in their representations. Not only did this support my thinking with the data, but brought forth the children’s representations of place which glowed or evoked wonder (MacLure, Reference MacLure2013), provoking reflection, insight and questions.

Findings and Discussion

Through the children’s representations of place — story-sharing, drawing, writing and gathered items — and the narrative summaries created by the author, the interconnectedness of humans, place and the more-than-human are made visible. The solo experiences make this possible through enabling: embodied and generative encounters; emergent relationships with place and the more-than-human; and learning with place. The role of nature connection practices in relation to (re)storying place relations is also discussed. This section contains excerpts from the narrative summaries, with ‘solo wander’ or ‘magic spot’ included initially to indicate which chapter the excerpt is taken from where it is unclear. More-than-human others are deliberately used as subjects in many sentences, in an attempt to shift focus from the centrality of the human. In saying this, I recognise that as Rautio argues, ‘environmental education is, by definition, anthropocentric’ (Reference Rautio2013a, p. 451). Rather than aiming to avoid anthropocentrism, I attempt to decentre the human in such a way as to also recognise that we are but one of many more-than-humans with whom we are entangled (Rautio, Reference Rautio2013a). Decentring of the human is a challenging task (Pacini-Ketchabaw et al., Reference Pacini-Ketchabaw, Taylor, Blaise, Taylor and Hughes2016), but one I attempt in order to foster new understandings of place that describe entanglement rather than separation of humans from the rest of nature.

Embodied and generative place encounters

The practices of both the magic spot and the solo wander enabled the children to have an embodied experience of place. I discuss how both attentiveness and responsiveness to place are aspects of this learning that enable generative encounters to occur. Children’s experiences are described in the narrative summary generated from the solo wander representations:

The mangrove-lined creek drew some of the children to it, enabling encounters with place. The crab holes in amongst the breathing roots of the mangroves intrigued Mason Footnote 2 : ‘I put something in one hole and then a crab popped out of the other one’. Footnote 3 One of the many mangrove seeds littering the ground was buried by Paul who tells the group he ‘wanted to plant one’. The trees also called to the children. Anna was drawn to climbing some, including ‘a perfect blue quandong tree to sit in’. Rosie found a ‘walking stick’, which she used and afterwards drew a picture of herself with.

This narrative demonstrates that ‘the body is at the centre of our experience of place’ (Somerville, Reference Somerville2010, p. 335). In Paul’s action of planting the mangrove seed, we can see an embodied responsiveness to place (Dawson & Beattie, Reference Dawson and Beattie2018) and that this encounter is generative, the boy and the seed mutually affecting each other. The seed is now in a new place and may become a tree. The boy is changed in ways we can only guess at, but the moment of planting appeared to make an impression as he mentioned it several times in the story-sharing. Embodied responsiveness is also apparent in Mason’s action of putting something in the crabhole, in Anna’s tree-climbing and in Rosie’s use of the walking stick she found. Rosie’s striking drawing of herself with the stick (Figure 2) represents a generative encounter. In the story-sharing Rosie said ‘I found this walking stick… that I’ve been using’. Rosie sometimes uses a walking stick as a mobility aid in her daily life, and here we can see that this stick and the girl have mutually affected each other. The ‘walking stick’ supported Rosie’s movement through this place and perhaps changed her experience as a result. While comparing the magic spot and the solo wander was not an intention of the project, the children’s full-bodied responsiveness with place was generally more apparent in the data from the solo wander than from the magic spot. This difference may have been due to a mutiplicity of factors, although the children having the agency to explore freely and use the whole of their bodies more easily enabled this full-bodied engagement, as evidenced from the excerpts above. They also demonstrate how learning from place arises from ‘a deep, embodied intimacy’ that involves ‘attentiveness to place from the whole body’ (Somerville, Reference Somerville2010, p. 338).

Figure 2. Rosie’s journal entry (solo wander).

The children’s attentiveness and the ways they engaged sensorily with the materiality of place were also evident in the magic spot:

Items which piqued children’s curiosity have been brought back to show the group. Anna has collected some bark which ‘feels like foam when you squish it’, clearly enjoying the sensory engagement with it. Rosie enjoyed playing with some ‘crunchy’ leaves which fell apart when she ‘tried to… fold them’.

Here we can see that the children have ‘intimate, immediate and embodied impulses to touch and become with others in their more-than-human common worlds’ (Taylor, Reference Taylor2017, p. 1456). It is an ‘embodied and relational learning’ (p. 1457), vastly different to rational ways of knowing characterised by traditional western education. Through these embodied and generative encounters occurring in both the wander and magic spot, we have seen the ways in which human and more-than-humans affect and are affected by each other; I now further consider how this builds reciprocal relationships in and with place.

Relationships with place and the more-than-human

The practices of journalling and story-sharing reveal the entangled relationships with place and the more-than-human that have emerged in this particular common world. As we have already seen, the solo time created opportunities for generative place encounters to occur. Encounters with the children’s nature names also reveal relationships that emerged:

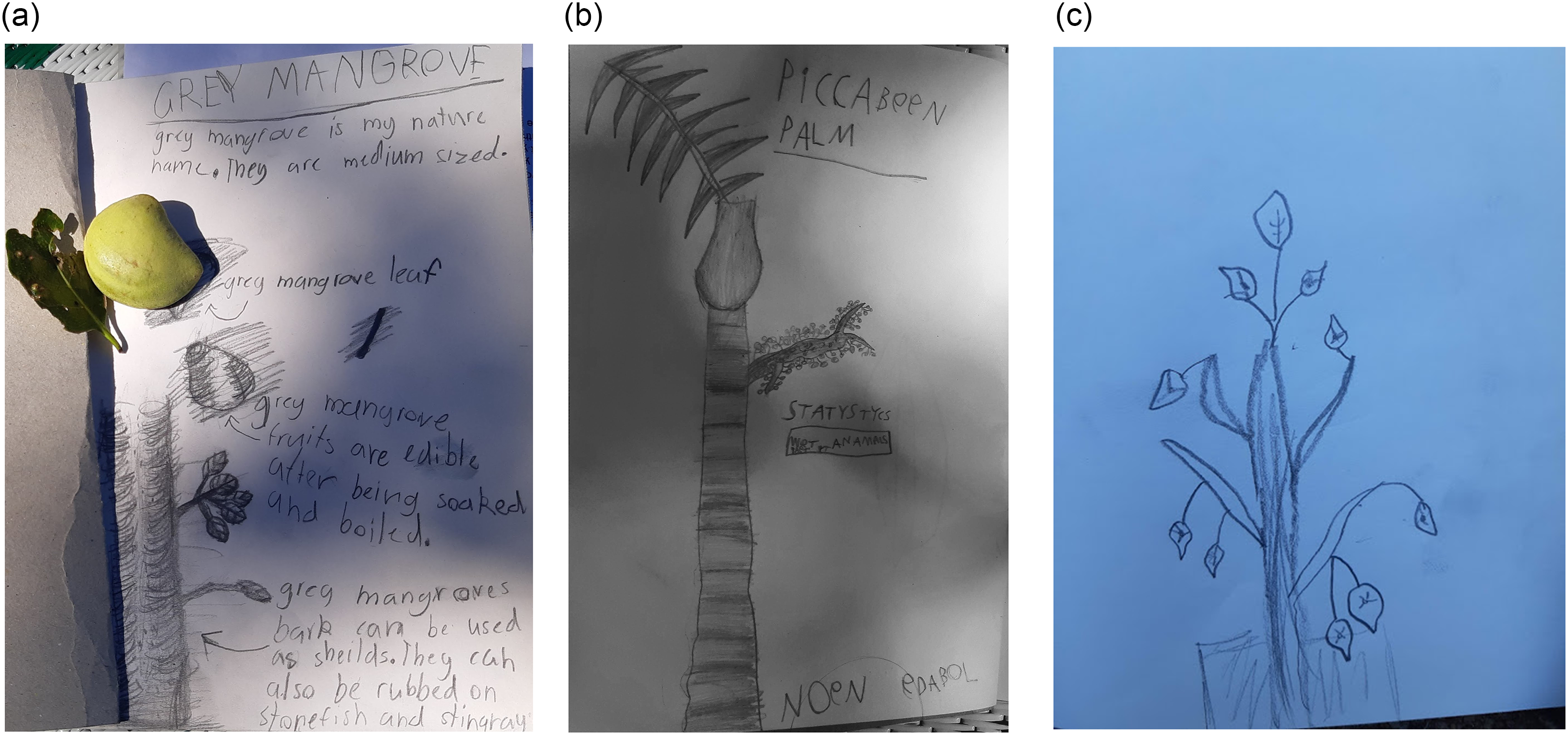

Solo Wander: The picabeen palm and the mangrove are captured in detailed drawings that Louis and Paul have drawn. Louis tells of finding a seed and leaves of the mangrove, his nature name tree. He has drawn these items, the tree itself and has accompanied these sketches with facts he has learnt about the mangroves. He tells the group: ‘I like the grey mangrove’.

Magic spot: Sarah has drawn a picture of the macaranga with its distinctive large leaves, telling the group she likes these leaves and says ‘it looks really beautiful when you go close up to it’. She also says that if the tree could speak it would say ‘Come sit next to me… and give me a hug’.

Through these narratives we can see that the encounters between the children and the trees have also been generative. Rather than learning about their nature names, the children are learning with them. After the solo wander, Louis, Sarah and Paul’s nature name trees featured prominently in their sharings and journal entries (see Figure 3a–c), even though there was not an intentional focus on nature names that day. As a place-responsive educator, I have repeatedly seen relationships emerge between children and their nature names. I vividly recall the palpable excitement of children spotting their nature name animals for the first time, and returning programme participants have often proudly listed off their nature names from previous programmes.

Figure 3. (a) Louis’s journal entry (solo wander). (b) Paul’s journal entry (solo wander). (c) Sarah’s journal entry (magic spot).

Louis’s representations of place through journalling (Figure 4) and story-sharing after the magic spot reveal entangled relationships of more-than-human others:

Figure 4. Louis’s journal entry (magic spot).

Louis has written that fairy wrens ‘like hanging around the grey mangrove’. He also talks of the spiders he observed ‘curled up into a ball’ in the mangrove. The importance of water for the grey mangrove is revealed through his sharing that if the mangrove would talk it would say ‘why don't you go in the water?’.

Louis has learnt that the fairy wrens ‘like hanging around the grey mangrove’ because he has observed them in this common world that he is entangled with. The excerpt and Louis’s journal entry show that he is aware of the interconnectedness of the mangroves, the creek, the fairy wrens and the spiders and we can see his relationship with these more-than-human others emerging. His awareness of these entanglements has occurred through attuning to this place, and again we can see there is a learning with place occurring here.

In the story-sharing after the solo wander, the children’s answers to questions about what they thought the place may be saying also reveal emergent relationships, as well as the complexity of human relationships with place and the more-than-human world:

‘The birds are talking to us’ comments Mason. Sarah says that if the place could talk it would say ‘talk to me because… I feel by myself’ and Kiera says it would say ‘please don't litter, just relax, be calm and… plant trees’. Anna tells the group that the trees would say ‘come touch me, come touch my bark… so we learn’. Paul says they would say ‘don't cut me down or I’ll slap you with my… branches’.

The children’s responses recognise some of the different ways that humans interact with and relate to place, revealing place as a ‘contact zone of contestation’ (Somerville, Reference Somerville2010, p. 342). Following Paul’s comment about the trees saying ‘don't cut me down’, I asked if he thought any of our group would cut them down and he responded by saying no but that ‘any other people would’. This may indicate a perception he holds of many humans as having extractive and exploitative relationships with place and not recognising the trees for their intrinsic value. This is in line with views held by the dominant culture that nature has meaning only when it serves human desires (Plumwood, Reference Plumwood, Adams and Mulligan2003). My sense from the way Paul spoke of planting the mangrove seed is that the action may have demonstrated a desire to respond to place in a different way to how he perceives many people act in the world. I see this as a response that is counter to the ethics of the dominant anthropocentric culture (Plumwood, Reference Plumwood, Adams and Mulligan2003); a response that also seems to reveal Paul’s recognition of the intrinsic value of trees. Comments from other children about not littering and planting trees also indicate an awareness of ways humans can act with responsibility in their relationships with place. Further comments reveal a perception of the place wanting to be engaged with in different ways, talking to it, touching it; a recognition of humans’ entanglement with place. Anna’s comment about the tree saying ‘touch my bark… so we learn’ again invites us to consider how the children are learning with place and the more-than-human, and this idea is explored in the next section.

Learning with place

As already evidenced through the children’s story-sharings and journal entries, we can see how the children are learning with place through their encounters. The nature connection practices inform us about who lives in this place and the different ways that we are entangled with these more-than-human others. Together the children and I know that the grey mangroves produce abundant seeds here, that crabs, fairy wrens and spiders live amongst the mangroves. We know they are part of this particular common world we are part of. We know we are active participants entangled in this place — that sticks might invite us to pick them up and use them as walking sticks, that trees may draw us to climb them and seeds to plant them (Rautio, Reference Rautio2013b). The place and more-than-humans can hence be seen to have agency here; with the ‘ability to act, to affect change’, ‘to teach, to learn, and to know’ (Dawson & Beattie, Reference Dawson and Beattie2018, p. 133).

The practice of ‘gathering’ that took place during the solo wander also reveals who is here, supporting learning with place:

Items gathered by the children tell us about this place. There are different coloured fruits, seeds, snail shells, a twig, the ‘walking stick’, and a range of leaves which the children describe, noting their shapes, sizes and textures. Rosie has collected a leaf she liked ‘the look’ and ‘feel of’, while Anna has collected leaves from one of the trees she climbed. Three children have brought back mangrove seeds, reflecting the prominence of the mangroves here.

Interestingly, the presence of snails was apparent in both sessions through several children collecting snail shells and /or drawing snails (see Figure 5a and b). Their presence intrigued me as outside of Earth Kids programmes I have spent significant time at the site, but had not noticed any snails. The child-snail assemblages therefore invite me to see anew, to wonder about the place of snails and the ways in which they are entangled with our common worlds. This illustrates that as we sit together and listen to the children’s stories, collective understandings of place grow as the adults, children and more-than-human learn together (Young et al., Reference Young, Haas and McGown2010). Through the nature connection practices we are learning with this place, and yet, there is still much more to learn here. I have a sense, and perhaps the children do too, that there is always a multiplicity of entanglements occurring that we are unaware of, and that each time we come here, there are new generative encounters that may occur and further reveal our interconnectedness with this place. We can recognise that this place is affecting us and we are affecting it; we are all being ‘co-shaped’ (Pacini-Ketchabaw, Reference Pacini-Ketchabaw2013) by these place encounters.

Figure 5. (a) Keira’s journal entry and gathered items (solo wander). (b) Mason’s journal entry and gathered items (solo wander).

(Re)storying place relations

I now turn to reflecting on the ways in which the nature connection practices have contributed to (re)storying place relations. Through the embodied and generative place encounters and the emergent relationships, stories and understandings of this place have surfaced (Somerville, Reference Somerville2010), as evidenced through the children’s place representations and the narrative summaries. In the storying of this place, ‘humans, more-than-human things, plants, as well as practices and multiple knowledges, are all participants’ (Nxumalo & Villanueva, Reference Nxumalo and Villanueva2019, p. 50). The stories and other place representations which emerged can be seen to be counter to dominant and colonised understandings of nature as separate, other, homogeneous and lacking in value or agency (Plumwood, Reference Plumwood, Adams and Mulligan2003). The solo experiences enabled an embodied knowing of place, fostering new relationships to place and the more-than-human. The journalling provided an avenue for the children to reflect on their encounters and express this embodied knowing of place (Nxumalo & Villanueva, Reference Nxumalo and Villanueva2019; Somerville, Reference Somerville2010). In turn, the circle time sharing enabled the children’s relationships to place and the more-than-human to be communicated in stories (Somerville, Reference Somerville2010). Through these stories, new collective understandings of place emerged — of place as diverse, interdependent, agentic, having inherent value and interconnected with the children.

Notably, the children’s place representations are devoid of First Nations histories and knowledges (Nxumalo & Villanueva, Reference Nxumalo and Villanueva2019), pointing to the ways in which settler colonial narratives of urban lands as no longer Indigenous and uninhabited can easily be reinforced if practitioners do not prioritise ways in which to presence First Nations people (Bang et al., Reference Bang, Curley, Kessel, Marin, Suzukovich and Strack2014). Pacini-Ketchabaw (Reference Pacini-Ketchabaw2013) invites me to consider that this place knows these histories and challenges me to ask questions to presence them in the circle time following the solo experiences. Incorporating place stories directly from Yuggera or Turrbal people has been a feature of some Earth Kids programmes, and making this a more regular feature could further contribute to presencing First Nations histories and cultures, as well as to recognising ongoing colonisation and supporting conversations about First Nations sovereignty. These are considerations I will take forward as I continue to evolve the nature connection practices within the Earth Kids programme.

Conclusion

Visible through the children’s words and drawings is a diverse ecosystem of interconnected life. Moments of encounter have occurred and dynamic relationships have emerged between children and the more-than-human. We humans and more-than-humans are learning with this place and we are all changed by the encounters here.

As evidenced through this study, the embodied practices of the magic spot and solo wander, together with the reflective practices of journalling and sharing stories supported by gathering, can make a contribution to the practice of a place-responsive pedagogy that enables the interconnectedness of humans, more-than-human others and place to become visible. The use of solo experiences, together with journalling and story-sharing is encouraged as an important practice to be incorporated into outdoor programmes. This study indicates that the solo wander enables a more full-bodied responsiveness, while the magic spot cultivates attentiveness, both important aspects of embodied learning, which foster generative and affective place encounters to occur. The representations of place through journalling, gathering and story-sharing are demonstrated as valuable pedagogical as well as methodological tools, suggesting human, place and more-than-human entanglement. These practices integrated together have potential to be further developed and used in different ways with learners of all ages. The incorporation of nature names into outdoor programmes has also been shown to foster relationships with more-than-human others, cultivate learning with place, and to grow children’s awareness of human entanglements with the common worlds they are a part of. Research into the use of nature names warrants further exploration, particularly in relation to children’s connection with them through the whole experience of a programme and not only to solo experiences, as in this study. Collectively these practices can enable encounters that generate new understandings and stories of place that are counter to dominant anthropocentric understandings of the human/nature binary. It is however important to recognise that the place stories generated in this study did not presence First Nations histories and knowledges. With this limitation in mind, educators wanting to take a place-responsive approach and support understandings of the interdependence and interconnectedness of humans with more-than-human others and place, can benefit from incorporating these nature connection approaches into their practice. In doing so they can experiment with a thinking with and learning with place that may contribute to decentring humans in outdoor learning.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to Professor Susanne Gannon for her guidance throughout the project, and whose insights contributed to the development of this article. Gratitude to Jon Young for his inspirational nature connection work and to my Social Ecology cohort, tutors and mentors at the University of Western Sydney for their support. I acknowledge the many people at Northey Street City Farm who make Earth Kids possible and in particular the children who participated in this project. Deepest thanks to the place itself and the more-than-humans there, who make place-responsive learning possible for children and adults alike.

Competing interest

Emma Brindal is a permanent employee of Northey Street City Farm (NSCF) and previously led the Earth Kids programme, as well as being the lead investigator/researcher in this project. These interests and potential conflicts were managed by:

-

Gaining approval by the Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee, Approval No: H14308

-

Gaining approval from NSCF for conducting the research project

-

Disclosing the researcher’s dual role to Earth Kids parents and participants

-

Following all NSCF policies and procedures while conducting the research

-

The lead investigator/researcher Emma Brindal being provided with overview by supervisor Professor Susanne Gannon.

This manuscript is an original work that has not been submitted to nor published anywhere else.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical standard

The procedures undertaken in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from both the parents and the children themselves to participate in the study.

Emma Brindal recently graduated from a Master of Education (Social Ecology) course at the University of Western Sydney. She lives and works on Yuggera and Turrbal country in Brisbane. She has been working in the field of environmental education for the last decade and currently works at NSCF. Emma is passionate about place-responsive education and works with other educators to support them in integrating outdoor learning into the curriculum.