Background

Suicide is a critical public health concern and one of the leading causes of death in the UK and across the world.1,2 Epidemiological studies have reported that more than 700 000 people lose their lives by suicide each year globally,1 with 5583 suicides recorded in 2021 in England and Wales.2 Moreover, the risk of suicide is higher in people with history of self-harm compared with those without such history.Reference Chan, Bhatti, Meader, Stockton, Evans and O'Connor3 Therefore, the associations between self-harm and suicide have been widely studied.Reference Grandclerc, De Labrouhe, Spodenkiewicz, Lachal and Moro4

Clinical record studies have shown that suicide rates and risk factors for suicidal behaviours vary considerably in ethnic minority groups in England and Wales.Reference Hunt, Robinson, Bickley, Meehan, Parsons and McCann5–Reference McKenzie, Bhui, Nanchahal and Blizard7 Similarly, self-harm rates differ across the ethnic groups in the UK.Reference Bhui, McKenzie and Rasul8 The self-harm rate was higher among South Asian women than White women aged 16–24 years, but was lower in South Asian men than in White men in all age groups.Reference Cooper, Husain, Webb, Waheed, Kapur and Guthrie9 Further, older South Asian people were found to be a high-risk group for suicideReference McKenzie, Bhui, Nanchahal and Blizard7 and depression.Reference Chaudhry, Husain, Tomenson and Creed10 An observational cohort study indicated that the rate of hospital presentation of self-harm was lower in ethnic minority children and adolescents compared with their White counterparts.Reference Farooq, Clements, Hawton, Geulayov, Casey and Waters11 However, rates of self-harm increased more in the ethnic groups than in the White group across the 16-year study period.Reference Farooq, Clements, Hawton, Geulayov, Casey and Waters11 Further, ethnic minority groups were less likely to receive a specialist psychosocial assessment by psychiatry liaison staff.Reference Farooq, Clements, Hawton, Geulayov, Casey and Waters11 This evidence is reflected in the National Suicide Prevention Strategy for England, which highlights high-risk groups, such as Black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups and people with a history of self-harm. More research is needed to understand the mechanism of self-harm, and more actions to deliver tailored suicide prevention approaches for high-risk group are encouraged.12

Previous literature reviews have evaluated the clinical characteristics of, and risk factors for self-harm among ethnic communities in the UK.Reference Bhui, McKenzie and Rasul8,Reference Al-Sharifi, Krynicki and Upthegrove13,Reference Husain, Waheed and Husain14 The review of self-harm in British South Asian women has illustrated that cultural conflict and marital and interpersonal problems could have major influences on self-harm.Reference Husain, Waheed and Husain14 However, these reviews are outdated, focusing mostly on quantitative studies and often including heterogeneous ethnic minority samples, thereby precluding inferences focused on South Asian people.Reference Bhui, McKenzie and Rasul8,Reference Al-Sharifi, Krynicki and Upthegrove13 Therefore, synthesis of in-depth and methodologically strong evidence examining the experiences of self-harm among South Asian people is lacking. This study is the first systematic review of qualitative studies to employ a meta-ethnographic synthesis to examine how self-harm and suicide are viewed or experienced by South Asian people in the UK, including perceptions about risk factors, the recovery process and mental health service responses.

Method

This systematic review was guided by and presented according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA).Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow15 The systematic review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number: CRD42020187435). Meta-synthesis was conducted based on the meta-ethnographic approach.Reference Noblit and Hare16 The data management software NVivo 12 for Windows and macOS (Lumivero Operating Systems, Denver, CO; see https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/) was used to assist in coding.

Systematic search strategy

A systematic search was first conducted from the inception of this research study until April 2020, and was updated on 6 May 2022, on six online databases: Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Open Dissertations and British Library Ethos. Multiple pilot searches were applied to, and adapted for, each database before running the final systematic searches. These final systematic searches included a combination of ‘Medical Subject Headings’ (MeSH) and text words. Three different clusters of keywords, around ‘self-harm’, ‘South Asian’ and ‘United Kingdom’, were used. The reference lists of the included articles and relevant reviews were also hand-searched to identify further studies. The entire search strategy is reported in Supplementary Appendix 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.63.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included in the systematic review if they met the following criteria: (a) they employed qualitative or mixed-method designs and presented qualitative findings written in English; (b) they included South Asian people who are UK residents (South Asian countries are Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka; studies with multi-ethnic sample groups were included if they presented findings from South Asian people separately); (c) they examined the views and experiences of South Asian people relating to self-harm, suicidal behaviour or suicidal ideation, regardless of age and gender, although as the current review aims to explore participants’ perceptions of self-harm, personal history of self-harm was not required and participants might have shared their own self-harm history or opinions about how self-harm and suicidal behaviour are experienced in their community; and (d) they reported participants’ views or experiences relating to self-harm or suicide, even if the primary focus of the study was not on self-harm or suicide.

Studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (a) they did not present original and qualitative data; (b) they were conducted outside the UK; (c) they did not include South Asian participants or did not present findings from South Asian participants separately from other ethnicities and (d) they did not specifically discuss self-harm, or suicidal behaviour or ideation.

Study selection

A two-stage screening process was applied. Initially, two reviewers (B.O.-D., S.K.K.) read the titles and abstracts of the studies and then the full texts independently. At both stages, the reviewers discussed the suitability of the selected studies according to the selection criteria. When there was disagreement over an article, the supervision team (N.H., M.P., S.G.) was consulted. The first reviewer contacted the authors of the papers for further clarification if needed.

Data extraction

Essential information was extracted from the included studies by the two reviewers (B.O.-D., S.K.K.) independently. Descriptive data from the studies, including the authors, publication year, study type, the study aims, sample size, data collection methods and analysis methods, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Details of the included studies

IPA, interpretative phenomenological analysis.

Risk-of-bias assessment

Two reviewers (B.O.-D., S.K.K.) assessed the quality of the selected studies independently. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist was used for this assessment.17

Meta-ethnographic synthesis

Meta-ethnography is an interpretative approach for synthesising qualitative studies that was first proposed by Noblit and Hare.Reference Noblit and Hare16 Unlike the traditional aggregative method that summarises the findings of original studies, meta-ethnography helps to produce new understandings and reconceptualisations of phenomena.Reference Noblit and Hare16

Meta-ethnography includes three different syntheses: (a) reciprocal translations of analogous studies, i.e. comparing the similarities between studies; (b) reputational translations of contradictions between studies and (c) a line of argument that interprets any similarities and dissimilarities as new inferences.Reference Noblit and Hare16 In this review, the included studies have sufficient commonalities, rather than disagreements, to enable the application of reciprocal translations.

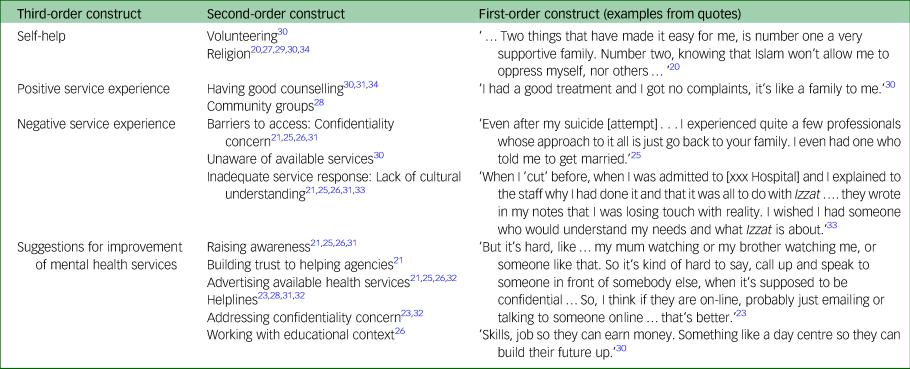

Reciprocal translations are applied and presented via the notion of first-, second- and third-order constructs.Reference Schutz18 The first-order constructs are the participants’ quotes in the included studies, the second-order constructs are the authors’ interpretations of these quotes and the third-order constructs are the overarching themes produced from the previous constructs by the research team.Reference Britten, Campbell, Pope, Donovan, Morgan and Pill19 The themes and the constructions produced are presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Table 2 The reciprocal translations for ‘Behind self-harm’

Table 3 The reciprocal translations for ‘Functions of self-harm’

Table 4 The reciprocal translations for ‘Recovery from self-harm’

Result

A total of 614 articles were identified by the searches. After removing duplicates, 437 studies remained. Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of these studies, of which 49 studies underwent full-text screening. Finally, ten articles and five doctoral theses were included in the meta-synthesis. The literature search flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Descriptive characteristics of the selected studies

Table 1 presents the key descriptive characteristics of the included studies. Twelve studies recruited participants with lived experience, whereas three studies presented the experiences and perceptions of self-harm and suicide of people with and without lived experience.Reference Gunasinghe, Hatch and Lawrence20–Reference Hicks and Bhugra22 Of the 15 articles, 14 had female participants, and only one studyReference Klineberg, Kelly, Stansfeld and Bhui23 included both female and male participants. Although mean age was not recorded in all of the included studies, the research population in most studies included young adults, with the overall age range being 14–55 years.

Risk-of-bias assessment

The results of applying the CASP Qualitative Checklist showed that most studies had clear aims and rigorous methods for data collection and analysis. However, five studies did not discuss ethical considerations and seven studies did not report the researchers’ reflections. In all of the doctoral theses, ethical approval was obtained and the data collection process and results were clearly presented. Results of the entire quality assessment are available in Supplementary Appendix 2.

Main findings of meta-synthesis

The meta-synthesis of the included studies was generated based on three reciprocal translations, which are behind self-harm, functions of self-harm and recovery from self-harm. The reciprocal translation of ‘behind self-harm’ explores the associations between risk and precipitating factors, and self-harm. ‘Functions of self-harm’ represents the descriptions and meanings of self-harm for the participants. ‘Recovery from self-harm’ discovers self-help, professional help received and suggestions for the improvement of mental health services.

Behind self-harm

Behind self-harm uncovers what might have led people to harm themselves. Several factors were directly linked to self-harm, in addition to the factors indirectly leading to self-harm by causing chronic stress and difficulties in an individual's life. These direct and indirect risk factors spanned personal, interpersonal and societal matters. Table 2 shows the reciprocal translations of ‘behind self-harm’, which include five third-order constructs: negative perceptions of self, isolation, exposure to violence, cultural risk factors and economic problems.

Negative perceptions of self were discussed in seven studies. Self-harm was directly linked to self-hate,Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21,Reference Aktar24–Reference Sambath26 self-worth and low self-esteem.Reference Aktar24,Reference Bhardwaj25,Reference Ahmed, Mohan and Bhugra27–Reference Wood31 Those who reported self-hate saw self-harm as self-punishment.Reference Sambath26

Isolation and its impact on mental health were mentioned in almost all studies. Some studies explored how conceptual factors led to increased isolation in South Asian women.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21 The lack of trusted companions was a commonly reported theme. Therefore, South Asian women were unable to share their difficulties, which led to ongoing distress. Also, interpersonal losses and rejections were linked to suicidal ideation and behaviours.Reference Hicks and Bhugra22,Reference Sambath26,Reference Sayal-Bennett30,Reference Marshall and Yazdani32 The lack of English proficiency was another factor that was associated with a lack of knowledge of health services. This prevented individuals from accessing mental health services and from knowing about available resources and their rights.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21,Reference Hicks and Bhugra22,Reference Ahmed, Mohan and Bhugra27,Reference Hussain and Cochrane29–Reference Wood31

Exposure to violence represented all kinds of experiences of racist, sexist and abusive behaviours exacerbating mental well-being, which were reported in the studies. Racism was reported as an external pressure by South Asian women.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21,Reference Aktar24,Reference Sambath26,Reference Chantler28,Reference Sayal-Bennett30,Reference Wood31 Abusive relationships and domestic violence were linked in most studies to self-harm or suicide attempts when women could not receive any assistance to deal with their domestic situations.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21,Reference Hicks and Bhugra22,Reference Aktar24–Reference Sambath26,Reference Chantler28,Reference Sayal-Bennett30–Reference Mafura and Charura33 Discrimination owing to gender and ethnicity also increased isolation among South Asian women.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21 South Asian women have spoken about this double jeopardy they have faced:

‘We're different; we're treated differently by our own because we're women, we're treated differently outside because we're Asian’.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21

Economic and political inequalities were reported in relation to housing issues, poverty and limited access to benefits/welfare rights.Reference Ahmed, Mohan and Bhugra27,Reference Chantler28,Reference Sayal-Bennett30 These issues were discussed in relation to systemic and political aspects such as the 2-year rule. The 2-year rule was a former law that mandated the deportation of foreign spouses who ended their marriage within 2 years of coming to the UK through marriage. This policy had negative outcomes of leaving some immigrant women in abusive marriages with limited options to leave or receive financial help.Reference Chantler28 For example, South Asian women who do not have welfare rights become economically dependent on their relatives, which perpetuates their distress when they experience domestic violence.Reference Chantler28 ‘State and familial oppression’ causes such distress, and has resulted in self-harm and suicide.Reference Chantler28 In one woman's account, the distress caused by the issue of obtaining a visa was presented as follows:

‘I think about it [suicide] a lot; the last two weeks have been awful – will I get my visa or not?’.Reference Chantler28

Further, the failure to provide housing to women who have escaped abusive relationships was also reported as a risk factor for suicide. Women could be easily tracked by their abusers in small communities, which makes providing safe housing to domestic survivors more crucial.Reference Chantler28

Cultural risk factors were discussed in most of the studies, including gender inequality, unrealistic expectations set for women, the community grapevine, family honour, forced marriage and being controlled by family members. There are some cultural risk factors for mental health that are not specific to South Asian culture, such as gender inequality. However, personal and social resources for dealing with such external pressures might differ among ethnic minority women.

Gender inequality is reported as feeling oppressed by ‘gender-based roles and expectations’,Reference Sambath26 and discrimination toward women might cause distress and self-harm.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21,Reference Aktar24,Reference Mafura and Charura33 South Asian women are subjected to the community grapevine as their community tends to monitor and blame women.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21 Unrealistic expectations were reported as another external pressure on women; these included academic expectations in families and traditional South Asian expectations of family members and the community.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21,Reference Aktar24–Reference Sambath26,Reference Wood31–Reference Thabusom34 Traditional expectations set high standards for women to follow. For example, women should protect their family's prestige with their academic achievements and ‘correct’ behaviours.Reference Gunasinghe, Hatch and Lawrence20,Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21,Reference Aktar24–Reference Sambath26,Reference Wood31–Reference Thabusom34 This interacts with another theme, family honour. Family honour is called izzat in South Asian culture, and is defined as ‘family or personal honour/respect, or as status and prestige in the eyes of the community’.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21 Giving much importance to family honour might cause people to ignore women's struggles and to hide the abuse within the family, all of which leave women alone with their distress.Reference Gunasinghe, Hatch and Lawrence20,Reference Mafura and Charura33 Being controlled was another cultural risk factor for distress mentioned in many studies.Reference Gunasinghe, Hatch and Lawrence20,Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21,Reference Aktar24–Reference Sambath26,Reference Chantler28,Reference Sayal-Bennett30–Reference Thabusom34 Forced marriage, being prevented from having an education and lack of autonomy were some examples of controlling behaviours. All unequal behaviours toward women listed above set barriers to sharing difficulties with others and seeking help from outside of the community.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21 Consequently, women had limited space and resources to discuss their difficulties and solve their problems, which caused further isolation, depression and self-harm.Reference Gunasinghe, Hatch and Lawrence20

Functions of self-harm

In the literature, functions of self-harm and reasons for self-harm were used interchangeably.Reference Nock35 In the current review, we define ‘functions of self-harm’ as how self-harm was perceived and what meanings and motivations were attributed to it. The theme of functions of self-harm was elaborated from the participants’ comments of what had happened just before, during or after self-harm. Table 3 shows the five third-order constructs that were generated from the findings of the studies: emotion regulation, communication and expression, taking or losing control, provoking change and negative experience.

Emotion regulation refers to the temporary positive effects of self-harm in easing the burden of a situation. In most studies, this situation was synthesised as a coping mechanism. Specifically, self-harm was viewed as relief from emotional pain.Reference Aktar24–Reference Sambath26,Reference Sayal-Bennett30–Reference Thabusom34 Self-harm functions to convert emotional pain into physical pain and, consequently, to produce a sense of relief just afterward.Reference Wood31,Reference Marshall and Yazdani32 Among women with depression, self-harm was seen as a way of releasing anxiety.Reference Hussain and Cochrane29

Communication and expression associated with self-harm was seen as the expression of anger, emotional pain and distress.Reference Gunasinghe, Hatch and Lawrence20,Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21,Reference Klineberg, Kelly, Stansfeld and Bhui23,Reference Aktar24,Reference Sambath26,Reference Wood31–Reference Mafura and Charura33 Self-harm was also described as a way of communicating when there is a lack of words to describe emotions.Reference Sambath26 Also, the intention to be noticed by others was reported.Reference Klineberg, Kelly, Stansfeld and Bhui23,Reference Wood31 This is beyond attention-seeking and is a sign of unspoken struggles.Reference Wood31

‘The thoughts I used to have … after cutting myself and before cutting myself, were, like, just show somebody … I wasn't a good talker, like, back then, so … that's why I knew that they would kind of help me in some way’.Reference Klineberg, Kelly, Stansfeld and Bhui23

Control was mentioned when describing self-harm in different ways. Self-harm was seen as taking control when participants felt that they had no control or power over their lives.Reference Bhardwaj25,Reference Sambath26,Reference Wood31–Reference Thabusom34 However, self-harm might mean losing control when it becomes a daily practice or only an option for temporary positive side-effects, such as feeling relief. Some participants reported that they could not stop self-harming even if they wanted to, and that they lost control of the frequency of self-harm.Reference Aktar24,Reference Wood31,Reference Marshall and Yazdani32

Provoking change represents the theme of self-harm being used to change situations or others’ behaviour. For some, self-harm was a way of obtaining care from others,Reference Klineberg, Kelly, Stansfeld and Bhui23,Reference Wood31 including external professional support.Reference Bhardwaj25,Reference Sambath26

In terms of negative experience, self-harm was described as having negative features and consequences. Self-harm was attached to feelings of shame and guilt afterward,Reference Aktar24,Reference Sambath26,Reference Wood31,Reference Mafura and Charura33 rather than bringing real change.Reference Sayal-Bennett30,Reference Marshall and Yazdani32 It was also described as unhelpful and sinful.Reference Aktar24,Reference Sambath26

Recovery from self-harm

Recovery from self-harm included self-help, positive and negative mental health service experiences, and suggestions for improving mental health services, which are presented in Table 4.

Self-help represents the second-order constructs of religion and volunteering. Religion was mentioned as a positive aspect of managing unbearable circumstances. Believing in Islam, which does not permit any harm to the self, praying to Allah and accepting the faith helped the participants to deal with their problems.Reference Gunasinghe, Hatch and Lawrence20,Reference Ahmed, Mohan and Bhugra27,Reference Hussain and Cochrane29,Reference Sayal-Bennett30,Reference Thabusom34 Doing voluntary work provided the participants with some social gain, such as helping others, spending their time well and getting away from difficult home situations.Reference Sayal-Bennett30

Positive health service experiences included receiving good counselling and community services support. The features of good counselling were described as ‘being listened to and understood’ with empathy by professionals who encourage women to express themselves.Reference Thabusom34 Cognitive–behaviour therapy was helpful because it provided ‘practical solutions’.Reference Wood31 Some participants explicitly stated that having counselling prevented them from attempting suicideReference Sayal-Bennett30 and self-harm.Reference Wood31 Community services were valued because they provided mental health support, offered housing and benefits support, and made effective referrals to the appropriate agencies.Reference Chantler28

Negative health service experiences were presented in terms of barriers to accessing services and inadequate service responses. Mistrust of health services was one of the barriers to seeking help. Participants reported that they would mistrust professionals from outside their community as these professionals might not understand them because of limited knowledge of South Asian culture.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21,Reference Bhardwaj25,Reference Sambath26,Reference Wood31 Similarly, they mistrusted professionals from within their community, who might break confidentiality or judge them according to traditional views.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21,Reference Bhardwaj25,Reference Sambath26,Reference Wood31 Further, lack of knowledge about available services was another barrier to obtaining help.Reference Bhardwaj25,Reference Chantler28 Some studies evaluated service responses to self-harm and suicide. Primary care workers provided limited support because of their lack of understanding of self-harmReference Marshall and Yazdani32 and non-referral of patients to mental health services.Reference Chantler28 Some respondents had experienced health workers not listening with empathy and understanding.Reference Chantler28

Suggestions for improving access to support services and service responses were synthesised. To improve mental health access, South Asian women recommended that trust in healthcare services and professionals should be built to enable South Asian women to discuss their personal concerns.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21 Also, the stigma around help-seeking and self-harm should be reduced.Reference Sambath26,Reference Wood31,Reference Marshall and Yazdani32 This could be achieved by increasing awareness about psychology and mental health,Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21,Reference Bhardwaj25,Reference Sambath26,Reference Wood31 along with promoting knowledge of self-harm and of the services available in the community and in educational institutions.Reference Chew-Graham, Bashir, Chantler, Burman and Batsleer21,Reference Bhardwaj25,Reference Sambath26,Reference Marshall and Yazdani32 For instance, support groups in schools could create a space to talk about self-harm and mental health openly.Reference Sambath26 The availability of services should be increased by providing telephone or online helplines.Reference Klineberg, Kelly, Stansfeld and Bhui23,Reference Chantler28,Reference Wood31,Reference Marshall and Yazdani32

For the improvement of service responses, the participants suggested that health professionals should have a greater understanding of the socioeconomic and cultural aspects of mental health among ethnic minority communities.Reference Sambath26,Reference Mafura and Charura33 Moreover, mental health services should address privacy and confidentiality concerns among patients.Reference Klineberg, Kelly, Stansfeld and Bhui23,Reference Marshall and Yazdani32 Ethnic minority patients’ preferences about health professionals’ ethnicity and gender should also be taken into account.Reference Marshall and Yazdani32

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-synthesis to explore South Asian people's experience and understanding of self-harm and suicidal behaviour in the UK. There are three main findings from our analysis. First, socioeconomic, political and cultural factors are found to be major stressors for South Asian women who have faced a double jeopardy of discrimination owing to their gender and ethnicity, from both within and outside their communities. Second, our findings on functions of self-harm are in line with the most studied function models in the self-harm literature, such as affect regulation and self-punishment. There are remarkable similarities regarding functions of self-harm by South Asian people with the wider literature on White majority self-harm samples. Therefore, it is important not to place too much emphasis on stereotypical assumptions about the cultural components of self-harm in South Asian people. Third, recovery from self-harm involves self-care activities, protective factors and professional help. Suggestions for improvement in engagement with mental health services are also generated.

Our analysis has identified several personal and interpersonal reasons and risk factors for self-harm, such as negative perceptions of self and relationship problems. This theme is consistent with recent research findings, which have shown lower self-esteem and interpersonal conflict to be linked to self-harm.Reference Forrester, Slater, Jomar, Mitzman and Taylor36,Reference Turner, Cobb, Gratz and Chapman37

The impact of socioeconomic and cultural factors on self-harm among South Asian people should be seriously taken into the account, which also aligns with the previous research.Reference Bhui, Stansfeld, McKenzie, Karlsen, Nazroo and Weich38,Reference Wallace, Nazroo and Bécares39 South Asian women have been subjected to multilevel stressors by the misuse of South Asian cultural values, such as setting high social expectations for women and controlling women through family honour.Reference Gilbert, Gilbert and Sanghera40 Further, racism has been associated with common mental health difficulties in ethnic minority groups in the UK.Reference Bhui, Stansfeld, McKenzie, Karlsen, Nazroo and Weich38,Reference Wallace, Nazroo and Bécares39,Reference Stoll, Yalipende, Byrom, Hatch and Lempp41 Our findings also reveal that financial problems have a considerable influence on the mental health of South Asian people in the UK.Reference Bowl42 Although the impact of economic difficulty on mental health has been acknowledged nationally, ethnic minorities seem to be more disadvantaged because of uncertain residency status or language barriers.12,Reference Bowl42 Longstanding economic and health inequalities also appeared during the COVID-19 pandemic.Reference Mahmood, Acharya, Kumar and Paudyal43 The rates of abuse, self-harm and suicidal thoughts were greater in women and Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups, along with some other socioeconomically disadvantaged groups.Reference Iob, Steptoe and Fancourt44

Further, limited immigration policies to protect South Asian women against domestic violence cause further isolation and mental health difficulties.Reference Gill45,Reference Mirza46 A recent systematic review of South Asian women who have experienced domestic violence in high-income countries states that multilayer barriers to seeking help include insecure immigration status, limited governmental and third-sector support, and lack of financial support.Reference Sultana, Ozen-Dursun, Femi-Ajao, Husain, Varese and Taylor47

Our analysis has captured functions of self-harm that are aligned with previous systematic reviews.Reference Edmondson, Brennan and House48,Reference Klonsky49 Empirical literature on the functions of self-harm were reviewed by Klonsky,Reference Klonsky49 and seven common function models were proposed. Our analysis captures four of these seven function models: affect regulation, self-punishment, interpersonal influence and interpersonal boundaries.Reference Klonsky49 Affect regulation is the most common function of self-harm in the literature, and means that self-harm works to manage negative emotions.Reference Edmondson, Brennan and House48,Reference Klonsky49 Moreover, self-harm as a means of communication or expression was a notable function in our findings.Reference Edmondson, Brennan and House48 This may be explained by our findings about increased isolation owing to socioeconomic and cultural contexts that are discussed under reasons for self-harm. Limited personal or professional resources in terms of talking about emotional struggles could be associated with self-harm being a way of expressing emotions.

The self-harm recovery process includes multiple personal and social qualities such as volunteering, believing in a religion, support from family and friends and having access to good counselling and community services, all of which are in line with a recent review on cessation of self-harm.Reference Brennan, Crosby, Sass, Farley, Bryant and Rodriquez-Lopez50 On the other hand, barriers to accessing and benefitting from professional help include a lack of awareness of available services, the stigma against seeking psychological help, confidentiality concerns and a lack of trust in health professionals.Reference Prajapati and Liebling51,Reference Watson, Harrop, Walton, Young and Soltani52

Strengths and limitations

This is the first meta-synthesis using on the meta-ethnography approach to explore the views and experiences of self-harm among South Asian people in the UK. We have included both grey and published literature in our review. Another strength of this study is that an explicit definition of the ethnic group being focused on was applied as an inclusion criterion. This allowed us to acquire an in-depth understanding of the experiences of self-harm among South Asian people. On the other hand, considering all South Asian people as one ethnic group could cause nuanced variations among South Asian communities to be missed. Therefore, we acknowledge the uniqueness of mental health experiences among South Asian people according to their personal differences, nationalities, migration stories and faith. Further, because of the subjective nature of qualitative synthesis, the researchers’ interpretations of the data could be influenced by their own cultural and professional backgrounds. To challenge this, we provided references from the selected studies in relation to each theme, which increases the credibility of the meta-synthesis.Reference Mohammed, Moles and Chen53

One of the limitations of the included studies is that very little attention has been paid to the perceptions of South Asian men about self-harm and suicide. Only one study included male participants. Additionally, the included studies are limited to the young adult research population, so there is also a need to explore self-harm among older South Asian adults. Finally, only five of the 15 studies were conducted during the past decade. Therefore, up-to-date research should be undertaken to explore self-harm among South Asian people, including all gender groups and older adults.

Clinical and research implications

This study provides important implications for researchers, mental health professionals and commissioners in improving treatments for, and the prevention of, self-harm and suicide in South Asian communities in the UK. We offer four critical recommendations: (a) training for care providers in culturally sensitive practice, (b) implementing of culturally adapted psychosocial interventions, (c) raising of mental health awareness among South Asian communities and (d) increasing access to mental health services.

Cultural understanding and sensitivity among mental health workers should be improved through training and supervision specific to working with ethnic minority groups.Reference Burr54,Reference Baldwin and Griffiths55 Our research highlights socioeconomic and cultural aspects of self-harm among South Asian people. These findings can inform care provider training on culturally sensitive practice when working with South Asian people. Moreover, culturally adapted psychological interventions were found to be effective treatments in recent meta-analyses.Reference Rathod, Gega, Degnan, Pikard, Khan and Husain56,Reference Anik, West, Cardno and Mir57 Our findings strongly encourage the development and evaluation of culturally sensitive self-harm interventions for South Asian people by using evidence that identifies the unmet needs of South Asian people in mental health services.

Further, mental health awareness should be raised among South Asian people through community-based programmes and conversations on confidentiality concerns. This is especially needed in relation to seeking help for self-harm, as shame and secrecy are commonly associated with experiences of self-harm and suicidal behaviours.Reference Curtis, Thorn, McRoberts, Hetrick, Rice and Robinson58,Reference Sheehy, Noureen, Khaliq, Dhingra, Husain and Pontin59 In addition, community organisations can be enhanced to provide long-term and practical support, such as life coaching, safety from abusive environments and financial assistance.

Increasing accessibility to mental health services might involve promoting these services, extending the availability of helplines and offering flexible timings and childcare to parents or caregivers. Online interventions or recorded psychoeducation would be helpful to those who cannot physically access health services.Reference Webb, Burns and Collin60,Reference Arshad, Farhat-Ul-Ain, Gauntlett, Husain, Chaudhry and Taylor61

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.63

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

B.O.-D., N.H. and M.P. formulated the research questions and designed the study. B.O.-D. and S.K.K. conducted the systematic search, screening, data extraction and quality assessment. Meta-synthesis was performed by B.O.-D. and revised by N.H., M.P. and S.G. All authors contributed to generating findings and writing the manuscripts.

Funding

B.O.-D. received a postgraduate scholarship from the Republic of Türkiye Ministry of National Education. The National Institute for Health Research Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre funded the time contributed by S.G. to this project and part of the time contributed by M.P. The study funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.