Health care-acquired infections (HCAIs) are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality among hospitalized patients worldwide, including the pediatric population.Reference El-Sahrigy, Shouman and Ibrahim 1 HCAI can affect patients in any type of setting where they receive care and can also appear after discharge. Resource-rich and resource-poor countries have different stated prevalence. As little as 4% is said to be prevalent in the US and 5.7% in the UK.Reference Abulhasan, Rachel and Châtillon-Angle 2 In developing countries, the highest frequency is found in the new born intensive care unit (10.7%) and pediatric critical care unit (15.5%).Reference Mohamed, Haftu and Hadgu 3 Because pediatric and new born critical care units differ in terms of architectural layout and patient severity, comparing infection rates between these units would be challenging and prone to errors. Blood stream infections and ventilator-associated pneumonia are the most prevalent health care-associated infections (HCAIs) on pediatric intensive care units, but catheter-related urinary tract infections and ventilator-associated infections are more common on adult neuro-intensive care units.Reference Abulhasan, Rachel and Châtillon-Angle 4 Patients and the health care team are susceptible to catching infections inside their hospitals for several reasons.Reference Wagh and Sinha 5 , Reference Feldman, Gornick and Huff 6 Health care-associated infections (HAIs) pose a significant threat to patient well-being, emphasizing the crucial role of health care professionals in preventing their occurrence.Reference Gilsdorf, Spearman and Englund 7 Studies reported that the incidence of antimicrobial resistance, which represents a major cause of health care-associated and community-acquired infections, is currently rising worldwide.Reference Folgori and Bielicki 8 , Reference Legese, Asrat and Swedberg 9 Pediatric nurses are at the forefront of providing care to children and, thus, play a vital role in protecting this vulnerable group from the risks associated with HCAIs.Reference Amatt, Marufu and Boardman 10 On the other hand, regarding the level of knowledge and awareness of nurses about hospital-acquired infections in pediatric care,Reference Kim, Kim and Bae 11 few data are available from a developing country because most studies have been conducted in adults in developed countries. This study aims to assess the current state of pediatric nurses’ competence in HCAI prevention at Al-Mezan Hospitals, Palestine, and to evaluate the effectiveness of educational interventions designed to enhance their knowledge, attitudes, and practices. As the incidence of HCAIs continues to be a pressing issue in health care facilities, the evaluation of pediatric nurses’ competence in infection prevention becomes essential.Reference Park, Bliss and Chi 12 Competence encompasses not only the knowledge and understanding of infection control principles but also the practical application and adherence to these principles in daily nursing practice.Reference Ahsan, Dewi and Suharsono 13 The importance of this research lies in its potential to inform and improve infection control policies, training programs, and, ultimately, patient care practices within the pediatric units of Al-Mezan Hospitals. By identifying gaps in knowledge and practice, the study seeks to provide a basis for developing targeted educational workshops and interventions that can significantly reduce the occurrence of HCAIs. The overarching goal is to ensure that pediatric nurses are equipped with the necessary tools and understanding to implement stringent infection prevention measures, thereby fostering a safer health care environment for pediatric patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study utilized a quasi-experimental design for before-and-after comparisons within the same group of participants, which was conducted in 2022. The study was conducted with 48 nurses working in various pediatric departments including the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), general Pediatric ward, and Nursery department. By using purposive sampling, all nurses who meet the study’s eligibility requirements were chosen.

Inclusion criteria

The samples were chosen based on the inclusion criteria listed below: 1) having a bachelor’s degree in nursing; 2) having at least 3 months of work experience in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), general Pediatric wards, and Nursery departments; and 3) willingness to participate in research.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria consisted of 1) refusal to participate in the study for any reason, 2) transfer from the study units, and 3) nurses on leave.

Sample size determination

The sample size was determined based on the findings of study (14) and the formula for comparing means, with a significance level (α) of 0.05 and a statistical power of 80%. Accordingly, the required sample size was calculated to be 57 participants. A total of 50 individuals agreed to participate in the study; however, 6 participants did not complete the study. Therefore, the final sample consisted of 44 individuals who completed all study requirements (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart for sample.

Ethical considerations

The project code that was adopted and the Council of Ethics’ code of ethics by the Palestine Polytechnic University (PPU) Ethics Review Board (approval number KA/41/2022) have been incorporated into this work. The study was conducted in compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.Reference Declaration 15 Moreover, 1) after gaining consent (signed written consent), the participants were informed of the research’s goals, 2), the project units received guarantees that the data are private and won’t have unfavorable effects, 3) it was assured to the project units that doing this has no negative effects, 4) the goals and benefits of the initiative were presented to the authorities, who will also have access to the results upon request, and 5) every participant gave written agreement as a volunteer and acknowledged that they were free to leave the study at any moment; the written consents to participate in the project were received.

Study tools

The questionnaire, consisting of 5 parts, was used to collect data.

Part 1. A questionnaire for collecting demographic data: the student’s demographic information survey.

Part 2. This section looks into pediatric nurses’ knowledge of HCAI. This section has 14 questions.

Part 3. Nurses’ perspectives on HCAI. These 12 questions probed the views of the nurse.

Part 4. Nurses’ practices regarding HCAI. This section of the test consisted of 12 questions that looked at nurses’ practices.

Part 5. Institutional measurement using 14 questions that evaluate the institutional infrastructure, condition, and readiness to support health care personnel in collaborating with infection prevention and control.

Scoring system. Knowledge, attitude, practice, and institutional measures to control were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree, 1 = disagree, 2 = natural, 3 = agree, 4 = strongly agree). The following are the cumulative scores for each domain: knowledge (14-70), attitude (12-60), and practice (12-60), divided into 3 levels: unfavorable (1-20), average (21-41), and favorable (42-60); and institutional measures to control (14-70), divided into 3 levels: unfavorable (scores between 0-23), average (scores between 24-47), and favorable (48-70 score).

Tools validity and reliability. To determine the validity of the tool, we made use of the Content Validity technique. The questionnaire was created by considering reliable websites, publications, and other field-validated surveys. Thereafter, it was reviewed by several academics from Palestine Polytechnic University, and any necessary modifications were made in response to their feedback. Test-re-test was used to evaluate the reliability of the tools. Nurses (15 per nurse) who are not participating in the study filled out the questionnaire; after a week, the same people received the questionnaire back and the issues was handled. Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.90) was determined.

Educational intervention and materials used

The intervention phase of the study involved the implementation of 4 structured educational workshops aimed at enhancing nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding HCAIs. These workshops were organized in small cohorts of up to 20 nurses to promote interactive learning and individualized engagement. The scheduling of sessions was coordinated with the hospital’s educational supervisor and head nurses and tailored to the nurses’ work schedules to minimize disruption to clinical responsibilities.

Each workshop session lasted 45 minutes and was conducted by a researcher holding a master’s degree in nursing, with a background in infection control and research on HCAIs. A combination of didactic lectures, interactive discussions, and question-and-answer sessions was employed to promote engagement, reflection, and practical knowledge application.

Importantly, the content of the educational program was developed in consultation with subject matter experts in infection prevention and control. The materials were reviewed for accuracy, relevance, and clinical applicability. Furthermore, the content was validated based on the guidelines provided by reputable international bodies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO). This validation ensured that the training adhered to evidence-based best practices and current global standards in infection prevention.

The educational content was structured into 4 sessions as follows:

-

• Session 1: Introduction and Importance of HCAIs Management This session introduced the study objectives and emphasized the significance of health care-acquired infections in clinical outcomes. It covered definitions, types of HCAIs, and a basic overview of infection pathophysiology.

-

• Session 2: Risk Assessment and Surveillance This session reviewed the previously discussed material and introduced assessment tools, methods to measure infection risk and prevalence, and identification of transmission routes and infection sources in clinical environments.

-

• Session 3: Infection Control Practices and Documentation Participants were trained on infection prevention techniques, the critical role of proper documentation, and protocols for recording and reporting infections. The session emphasized the health care provider’s responsibility in infection control and compliance with institutional policies.

-

• Session 4: Case-Based Simulation and Practical Application Simulation scenarios were used to reinforce knowledge and allow nurses to apply infection control techniques in practice. Participants were guided in the use of infection assessment forms and trained on appropriate documentation standards. This session concluded with a summary and distribution of printed educational materials aligned with CDC and WHO infection control recommendations.

The design and delivery of the workshops were based on adult learning principles, emphasizing active participation, critical thinking, and practical relevance. The structured format ensured comprehensive coverage of key competencies in HCAI prevention and management.

By grounding the educational content in validated international guidelines and expert review, the study ensured a high degree of credibility, consistency, and clinical applicability. This robust foundation is essential for effective behavior change among health care professionals and the successful implementation of infection prevention practices.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS v.23. Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, were employed to summarize the participants’ characteristics and scores. Paired t tests were conducted to compare pre- and post-intervention scores. The significance level for all analyses was set at P < 0.05.

Results

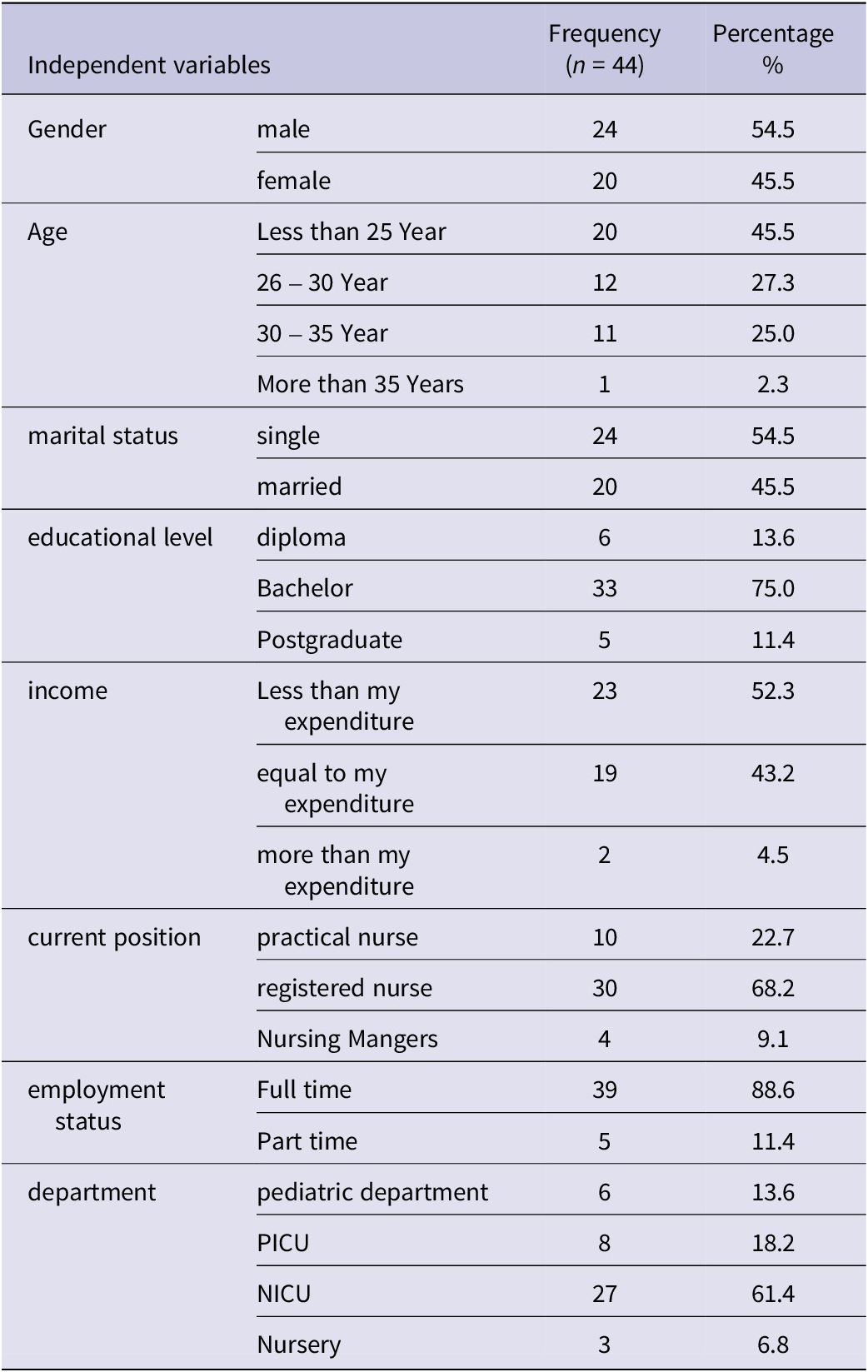

All 44 of the nurses who were still involved in this study followed the rules and were accounted for in the analysis. The findings indicate that in this research, 54.5% of the participants were male and 45.5% were female. Most nurses were under the age of 25 (45.5%). Most (54.5%) were single, compared to 45.5% who were married. Most nurses (68.2%) were registered nurses and held full-time jobs (88.6%). Most nurses (75%) had a bachelor’s degree. (Table 1).

Table 1. Participants’ socio demographic details

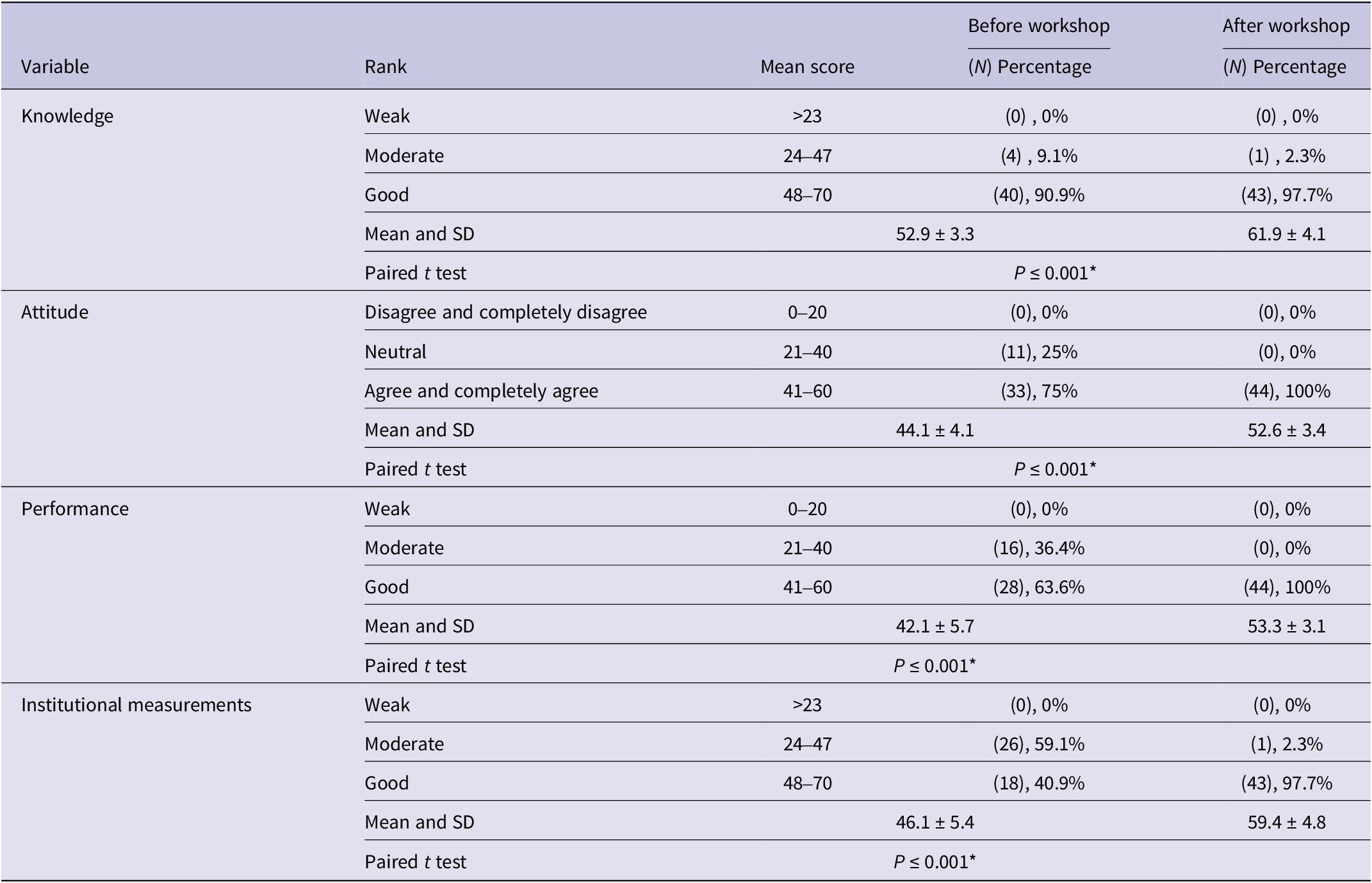

The results showed that the average score of knowledge before the workshop was 52.9 ± 3.3, and after the workshop, it was 61.9 ± 4.1. Also, the average attitude score before the workshop was 44.1 ± 4.1, and after the workshop, it was 52.6 ± 3.4. Before the workshop, most nurses (75%) had a “completely agree” or “agree attitude” toward HCAIs, and after the workshop, 100% had an “agree” or “completely agree” attitude. The results of this research indicate that the average performance score regarding questioning the nurses before the workshop was 42.1 ± 5.7, and after the workshop, it was 53.3 ± 3.1. The results also show that the average score of institutional measures to control regarding HCAIs before the workshop was 46.1 ± 5.4, and after the workshop, it was 59.4 ± 4.8. The paired t test results showed a significant difference between the mean scores of attitude, knowledge, performance and institutional measures to control by nurses before and after the workshop (P ≤ 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Levels of knowledge, attitude, and performance of nurses before and after hospital-acquired infection control

The Pearson correlation test demonstrated a significant relationship between the rank of awareness and the rank of nurses’ attitudes after the intervention in the field of HCAIs (P = 0.044, r = 0.305). Additionally, it revealed a meaningful association between the rank of awareness and the performance of nurses regarding HCAIs after the intervention (P = 0.017, r = 0.358). Furthermore, a significant correlation was found between the rank of attitude and the rank of nurses’ performance after the intervention (P = 0.024, r = 0.340). This indicates that conducting the educational workshop on HCAIs has been effective both individually and collectively on the factors of knowledge, attitude, and performance of nurses after the intervention.

Discussion

The results of this study show statistically significant improvements in nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, performance, and institutional measures regarding the prevention of HAIs after an educational workshop. These findings underscore the potential of structured training interventions to strengthen infection prevention and control (IPC) practices among nursing professionals, aligning with growing evidence in the literature.

Several studies have highlighted the effectiveness of educational interventions in enhancing the knowledge and behaviors of health care workers toward antimicrobial resistance and infection control.Reference Declaration 15 –Reference Abuhammad, Daood and Hijazi 19 These studies demonstrate that targeted educational programs can significantly improve awareness and clinical behaviors across different health care settings and populations. The increase in knowledge scores from 52.9 to 61.9, attitude scores from 44.1 to 52.6, and performance scores from 42.1 to 53.3 in the present study reflects a similar trend reported in earlier controlled interventions.Reference Abuhammad, Hamaideh and Al-Qasem 16 , Reference Abuhammad, Alwedyan and Hamaideh 18 This reinforces the centrality of continuing education as a strategic component in efforts to reduce HAIs.

Despite these improvements, the present study, like many others, has limitations in fully addressing how organizational infrastructure and institutional policies influence these outcomes. While institutional measures were assessed, there was minimal exploration of how factors such as leadership support, staffing levels, policy enforcement, and availability of resources may have interacted with the intervention. Previous research emphasizes that while knowledge and attitude improvements are necessary, they are insufficient without institutional support mechanisms that enable sustainable change.Reference Declaration 15 , Reference Abuhammad, Daood and Hijazi 19 , Reference Qtait 20

For example, health systems that invest in infection prevention infrastructure—such as surveillance systems, dedicated IPC personnel, and clear standard operating procedures—tend to report more durable and measurable reductions in HAIs. This implies that while educational workshops can produce short-term improvements, long-term success often depends on embedding these practices within an organizational culture of safety and compliance.Reference Alhawatmeh, Aljarrah and Hweidi 17 , Reference Qtait 20 Moreover, team-based support, ongoing supervision, and feedback mechanisms have been identified as mediators of behavior change, facilitating the translation of knowledge into routine clinical practices.Reference Abuhammad, Daood and Hijazi 19 , Reference Qtait 21 , 22

The omission of effect sizes and detailed test statistics in the current study is another limitation. While statistical significance was achieved, practical significance remains less clear. Reporting values such as Cohen’s d would enable a deeper understanding of the strength of the intervention. Effect size is especially relevant in applied health care research, as it translates numeric findings into actionable insights for policy and practice.

Additionally, the exclusive focus on pre- and post-intervention assessment, without a follow-up period, limits the ability to determine whether the changes in knowledge, attitude, and performance were sustained over time. Literature suggests that knowledge and behavior often decline without reinforcement. For instance, previous controlled studies showed that improvements in nurses’ infection control practices diminished after 3 months without continuous education or policy reinforcement.Reference Qtait 20 , Reference Qtait 21 , 23 Therefore, future studies should consider longitudinal designs to assess the persistence of intervention effects and explore strategies such as booster sessions or integration into routine training schedules.

The institutional dimension is especially crucial when considering that 59.1% of nurses initially scored in the moderate category for institutional measures, which improved significantly to 97.7% post-intervention. Although this increase is statistically significant, it may also reflect a temporary rise due to the immediate influence of the workshop. As shown in studies focusing on behavior change theory, institutional support structures, including mentoring, monitoring systems, and managerial involvement, are vital to maintaining such improvements.Reference Abuhammad, Alwedyan and Hamaideh 18 , 22 , Reference Sax, Allegranzi and Uçkay 24

It is also important to recognize the interrelation among knowledge, attitude, and performance, supported by the Pearson correlation results in the current study. A statistically significant relationship was observed between the knowledge and attitude ranks (r = 0.305), knowledge and performance (r = 0.358), and attitude and performance (r = 0.340). These correlations confirm that increasing awareness and shaping positive attitudes contribute meaningfully to clinical behavior. This finding is in line with prior models of health behavior change, which emphasize the importance of cognitive, affective, and contextual dimensions in shaping health professionals’ actions.Reference Qtait 21 , 22 , Reference Erasmus, Daha and Brug 25

Despite the improvements achieved, broader systemic and contextual factors must be acknowledged. Nurses often operate under high workloads, limited staffing, and resource constraints, which can affect their ability to apply knowledge consistently.Reference Ayed, Eqtait, Fashafsheh and Ali 26 Therefore, while educational workshops are effective, their integration within a wider framework of institutional accountability, leadership engagement, and structural reform is essential to ensure sustainability.

The present study adds to a growing body of evidence supporting the implementation of capacity-building programs in infection prevention. However, it also highlights that isolated training efforts, though beneficial, are not a substitute for comprehensive institutional change. Combining such interventions with policy development, leadership training, and structural investment in infection control infrastructure may provide a more holistic and enduring approach to reducing HAIs.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that a structured educational workshop significantly improved nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, performance, and awareness of institutional measures related to HAI control. The positive correlations among these variables highlight the interconnected nature of learning and behavior change. While the intervention was effective, sustaining such improvements requires ongoing education, supportive organizational policies, and robust institutional infrastructure. These findings emphasize the importance of integrating educational initiatives within broader institutional strategies to promote patient safety and infection prevention. Future research should explore long-term impacts and the role of leadership and policy in reinforcing infection control practices.

Data availability statement

The data from this study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns and legislative requirements.

Acknowledgements

We extend our deepest appreciation to the nurses who participated in the study. We are immensely thankful to the Palestine Polytechnic University Ethics Review Board for providing the necessary approvals and ethical oversight for this research.

Author contribution

Lo’ai Aburayyan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration. Candan Ozturk: Supervision, Methodology, Data analysis, Writing - Review & Editing Mohammad Qtait: Methodology, Data analysis, Writing - Review & Editing.

Funding statement

Specific funding was disclosed.

Competing interests

The authors of this article have stated that they have no potential conflicts of interest regarding the research, writing, and/or publishing of this work.

Ethical standard

The project code that was adopted and the Council of Ethics’ code of ethics by the Palestine Polytechnic University (PPU) Ethics Review Board (approval number KA/41/2022) have been incorporated into this work. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki’s principles.