Introduction

Health technology assessment (HTA) is a multidisciplinary process that uses explicit methods to determine the value of a health technology at different points in its lifecycle (Reference O’Rourke, Oortwijn and Schuller1). It typically involves a critical review of the evidence related to the clinical effectiveness of a health technology and to the optimal standard of care. It may also involve an assessment of economic efficiency as well as social and ethical implications in the local healthcare system (Reference Hunter, Facey and Thomas2). Typically, HTA remains focused on identifying quantitative evidence of clinical and cost effectiveness, but there is an increasing interest in understanding patient experience and preferences (Reference Wale, Thomas, Hamerlijnck and Hollander3). This presents an opportunity for patients and caregivers to make their voices heard (Reference Liu, Wu, Ahn, Kamae, Xie and Yang4;Reference Sirinthip Petcharapiruch5).

Patients’ input is becoming a standard requirement for some HTA evaluations (Reference Danner, Hummel and Volz6–Reference Menon and Stafinski9). These include the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in England (10), the Scottish Medicines Consortium in Scotland (11), the Department of Health and Ageing in Australia (12), and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) (13). Patients may have problems in their daily lives, such as fear of side effects or having difficulty taking their medicine, which can lead to poor compliance or even discontinuation of treatment (Reference Jin, Sklar, Min Sen Oh and Chuen Li14–Reference Facey, Boivin and Gracia16). However, these issues might be downplayed by health professionals due to a perceived lack of clinical or economic significance. European Patients Forum (EPF) HTA survey found that patient involvement helps HTA agencies and decision-makers understand the real-life impact of technology and quality-of-life implications, aiding decisions that address patients’ needs (17).

Many have argued the importance of the patient voice in the HTA process. Patient involvement can improve the quality, relevance, and value of HTA (18), promote transparency and fairness in the process (Reference Daniels and Sabin19), and help more accurately assess the value of health technologies (Reference Gagnon, Desmartis and Lepage-Savary20). As the direct beneficiaries of health technology, patients are closely linked to the interests of HTA, and therefore, involving patients in the HTA process increases the acceptance of HTA and the feasibility of the resulting healthcare decisions (18). Besides, given the governmental requirement for patient-centered health care and informed patient choice, patients should undoubtedly be included in the “multidisciplinary” HTA process for political legitimacy (Reference Facey, Boivin and Gracia16;Reference Wortley, Wale, Grainger and Murphy21).

Patients are essential stakeholders in health technology assessment, but their involvement is quite limited (Reference Wale, Thomas, Hamerlijnck and Hollander3). An observational study was conducted in New Zealand, South Korea, and Taiwan in September 2020. Findings suggested that less than half of the participants had knowledge or experience with HTA (Reference Single, Cabrera, Fifer, Tsai, Paik and Hope22). The EPF also painted an extremely pessimistic picture in its report on the survey of patient involvement in HTA in Europe, indicating that patient involvement has had little or no impact on decision making regarding health technologies (17). In addition to financial resource constraints, the main challenge of HTA is identified as a lack of awareness and effective training and support (Reference Hunter, Facey and Thomas2;17;23). HTA is seen as a scientific method; it has traditionally excluded patients’ views because they were considered anecdotal or biased (Reference Facey and Hansen24). Patients are either not involved at all or just marginally involved (17;Reference Cook, Cave and Holtorf25;Reference Levitan, Getz and Eisenstein26).

Patient involvement in HTA is nascent globally especially in Asia (Reference Liu, Wu, Ahn, Kamae, Xie and Yang4;Reference Gauvin, Abelson, Giacomini, Eyles and Lavis27;Reference Whitty28). The expectation of patients being able to be involved in HTA has increased along with the demand for innovative and important medical treatments and services (Reference Sirinthip Petcharapiruch5), but there are few practices on this (Reference Liu, Wu, Ahn, Kamae, Xie and Yang4). A good case in point is in Taiwan, where patients can report their views on an online platform, and the HTA agency then summarizes these views and incorporates them into the HTA report. Additionally, patient representatives are invited to participate in relevant HTA meetings (Reference Chen, Huang and Gau29).

Global HTA development can be categorized into three phases: rising HTA, where systems are in early stages and impact on decision making remains unclear; advancing HTA, with evolving systems but limited impact, and mature HTA, where well-established systems significantly influence decisions (Reference Sirinthip Petcharapiruch5). Most Asian countries are in the rising or advancing phases, while European and high-income countries are in the mature phase (Reference Georgiev, Yanakieva and Priftis30–Reference Kristensen32). Evaluation HTA progress in Asia is key to its growth, but a one-size-fits-all approach is not feasible due to regional differences (Reference Liu, Wu, Ahn, Kamae, Xie and Yang4).

The primary objective of this study is to assess patient awareness, involvement, and learning needs of HTA and to provide insights for future HTA training. The secondary objective is to compare the differences between Asian and non-Asian regions. The hypothesis of this paper is that the level of patient awareness and involvement of HTA in Asia is low, but there is a learning need.

Methods

The study utilized an anonymous online survey designed by the SingHealth Duke-NUS Institute for Patient Safety & Quality (IPSQ) from 25 October 2021 to 24 April 2022, with an extension to 29 July 2022. The survey, consisting of 23 questions on patient awareness, involvement, and learning needs in HTA, targeted patients, caregivers, and patient advocates (see Supplementary Appendix A). It was disseminated by various patient organizations located around the world through email invites containing an online survey link and QR code (see Supplementary Appendix B). It was published in both Chinese and English versions.

The eligible participants were patients, caregivers, and patient advocates. Patients in this survey were defined as those who were recently experiencing some medical disease or condition; caregivers were defined as both informal caregivers (relatives and friends) and formal caregivers (paid caregivers); patient advocates were defined as people who help guide a patient through the healthcare system.

Responses were mandatory for most parts of the survey, ensuring data completeness among diverse participants, who consented electronically and could opt out anytime. Ethical approval was granted by Duke Kunshan University and SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB).

Demographics in the questionnaire were categorized by region, gender, age, education, and income level, with Asia differentiated from non-Asia based on United Nations Statistical Division (UNSD) classifications. Central Asia, Western Asia, Southern Asia, Eastern Asia, and South-eastern Asia were defined as the Asian region. Others were defined as non-Asian region (Reference Nations33).

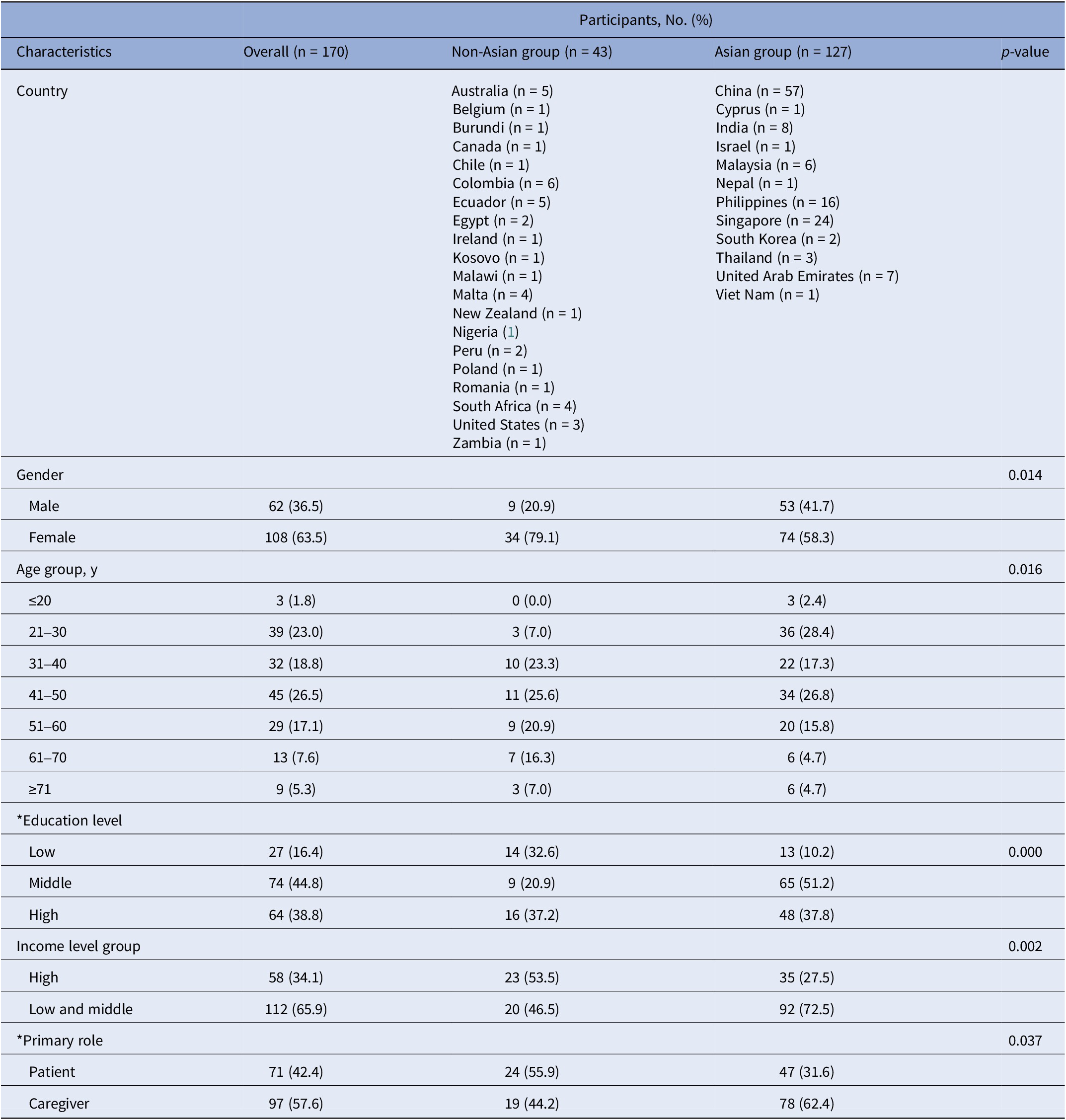

Age was categorized into seven groups: ≤20, 21–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, 61–70, and ≥ 71 years. Education levels were classified as low (primary, secondary/high school, diploma), medium (undergraduate), or high (postgraduate). Income levels were initially based on World Bank criteria (34) and then consolidated into two groups: high-income countries and low- and middle-income countries (combining upper-middle, lower-middle, and low-income categories) for analysis simplification (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of participants (non-Asian group vs. Asian group)

Note: p-values obtained from chi-squared test; *Education level: 5 missing data; *Primary role: 2 missing data.

Patient awareness was assessed using a familiarity scale covering 14 aspects of HTA (Q2: On a scale of 1–5, state how familiar you are in the following areas). Participation and learning needs were evaluated through two multipart questions (Q3: Have you been part of any HTA discussion or processes? Q4: Have you attended any HTA training?). All referenced questions are detailed in Supplementary Appendix A.

Descriptive statistics were used for demographic data. Patient awareness was measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not familiar at all, 5 = very familiar), with scores summed for total awareness. Two-sample t-tests compared mean awareness scores, while chi-squared tests compared patient involvement proportions. Analyses were conducted using Stata/SE version 16.0, with p < 0.05 considered significant. Microsoft Excel version 16.68 was used for data visualization. Responses marked “other” without description were treated as missing data.

Results

As of July 2022, 170 respondents from 33 countries across six continents participated in the survey. The majority (74.7 percent, 127 of 170) were from Asian regions. Respondents were predominantly from high-income (34.1 percent, 58 of 170) and upper-middle-income (47.6 percent, 81 of 170) countries.

Significant regional differences (p < 0.05) were observed in gender, age, education, income level, and primary role distributions (Table 1). Key findings include higher female participation in non-Asian (79.1 percent, 34 of 43) versus Asian (58.3 percent, 74 of 127) regions and differing age concentrations (Asian: 21–50 years, 72.4 percent (92 of 127); non-Asian: 31–60 years, 69.8 percent (30 of 43)). Education levels were generally higher in the Asian group, with 89.0 percent (113 of 127) having undergraduate or higher education, while non-Asian education levels were more evenly distributed. The Asian group primarily comprised from low- and middle-income countries and caregivers, while the non-Asian group consisted primarily of patients, with roughly equal representation from high-income and low- and middle-income countries. Detailed participant characteristics are provided in Table 1.

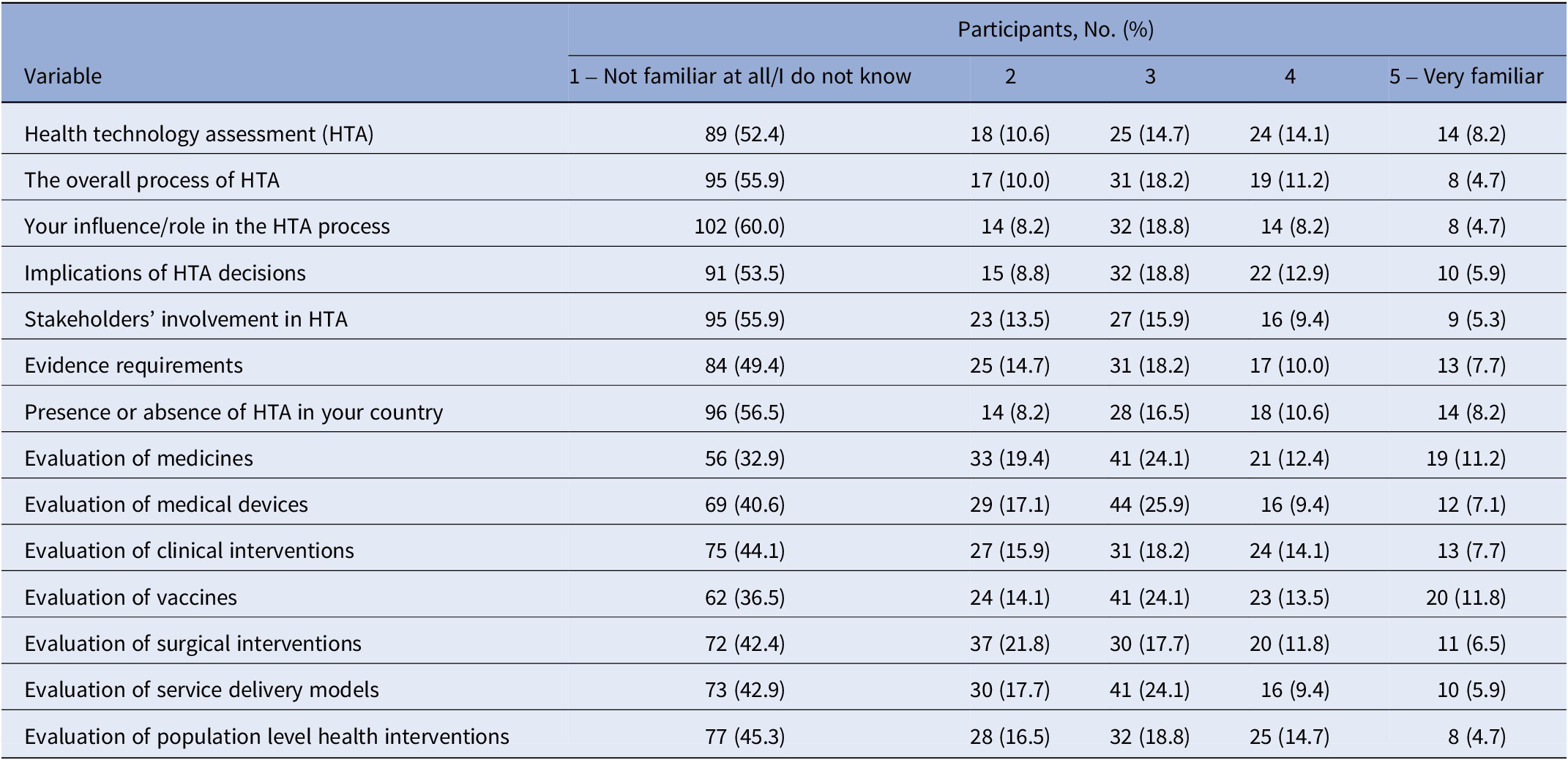

Patient awareness of health technology assessment (HTA) was generally low across all respondents. Over half of the participants (52.4 percent, 89 of 170) reported being “Not familiar at all/I don’t know” with HTA, and a similar proportion (55.9 percent, 95 of 170) were unfamiliar with the overall HTA process (Table 2).

Table 2. Global patient awareness

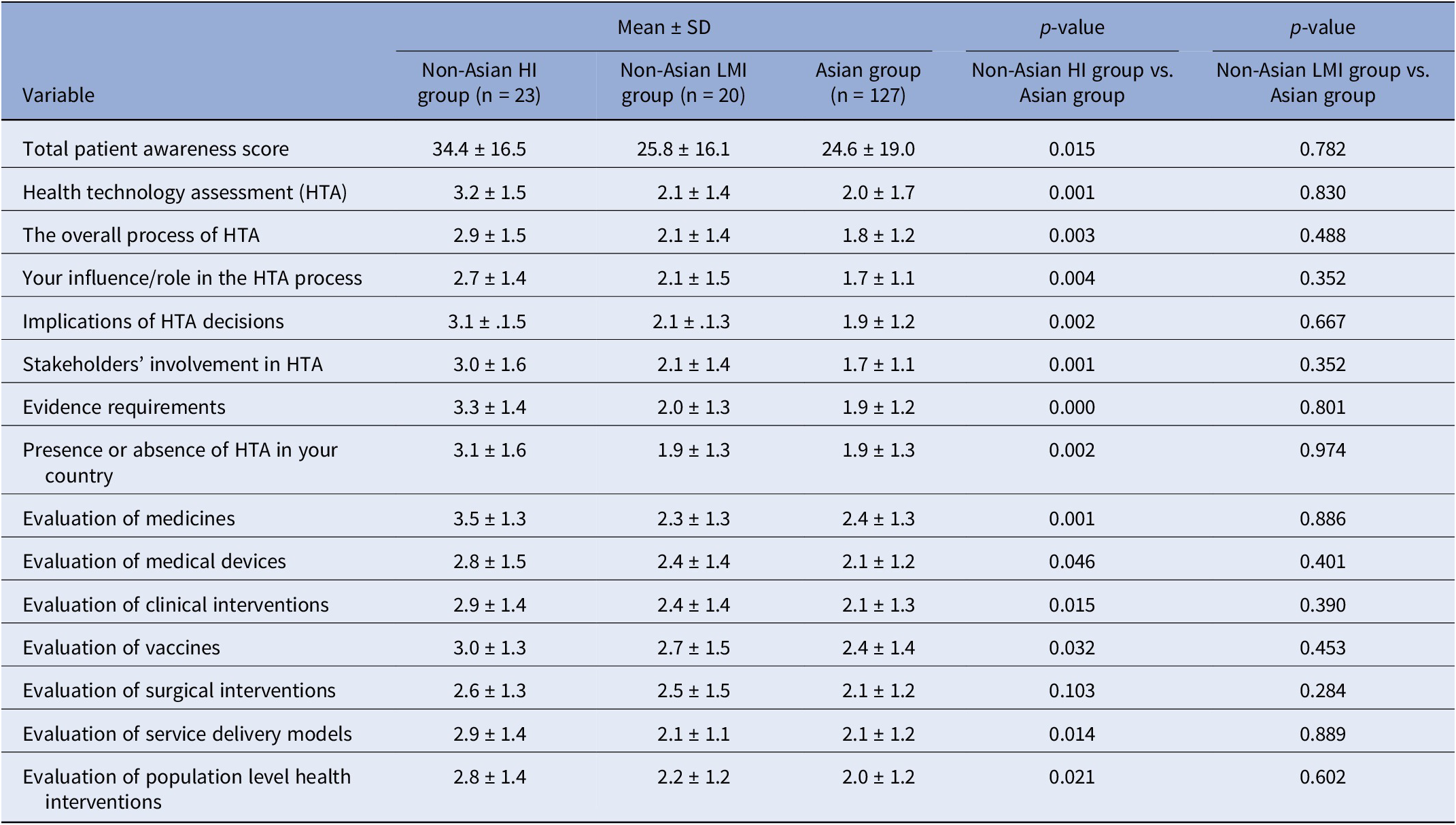

The Asian group consistently demonstrated lower mean patient awareness scores compared to the overall sample. Further analysis revealed that the Asian group’s awareness scores were significantly lower than those of the high-income non-Asian group across almost all aspects of HTA. However, when compared to the low- and middle-income non-Asian group, the Asian group showed no significant differences in awareness levels (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of patient awareness (non-Asian high-income group vs. Asian group vs. non-Asian low- and middle-income group)

Note: p-values obtained from two-sample t test; HI = high income; LMI = low and middle income.

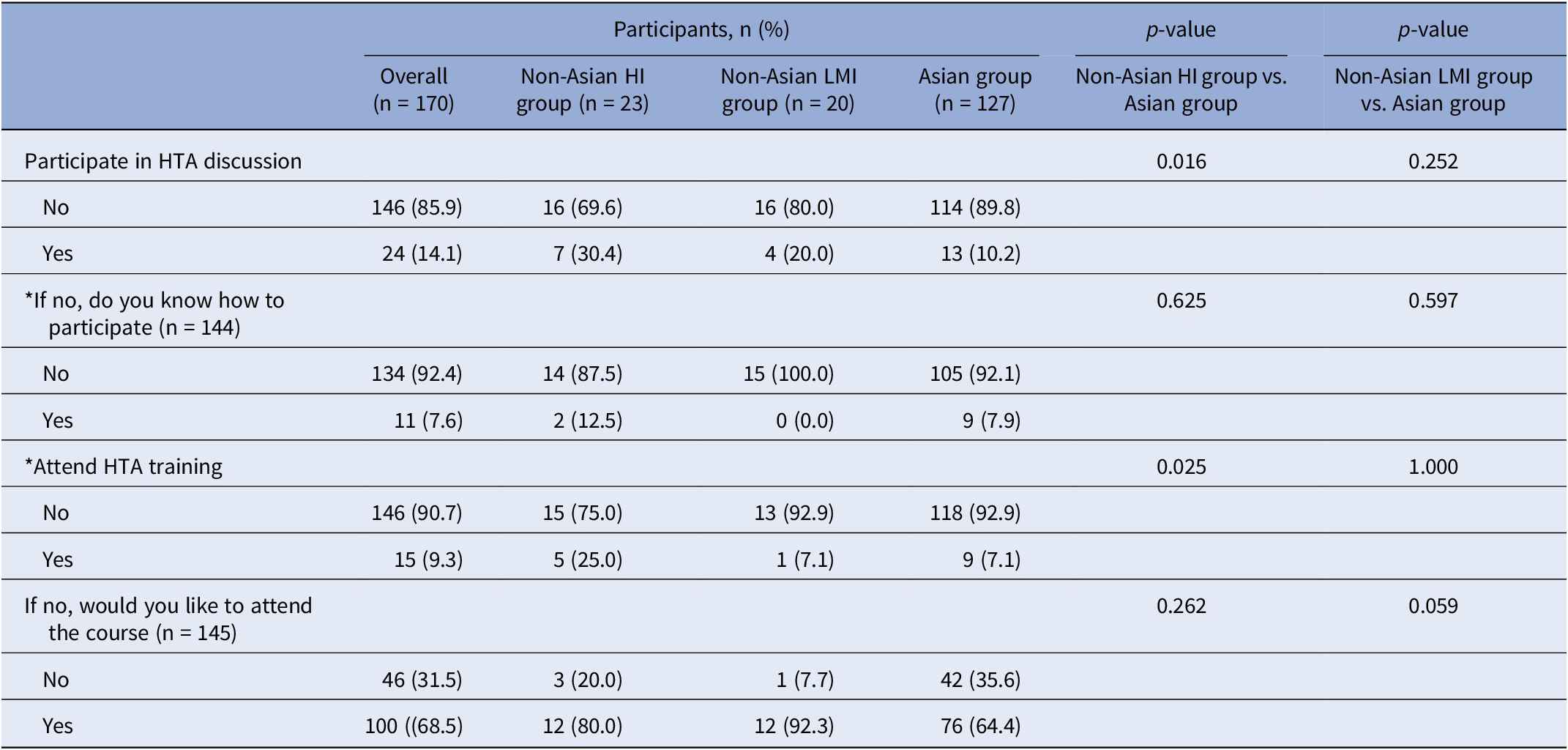

Patient involvement in HTA was notably low, but there was a strong interest in learning. Only 14.1 percent (24 of 170) of all respondents had participated in HTA discussions, and merely 9.3 percent (15 of 161) had attended HTA training. Among those who had not participated in HTA discussions, only 7.6 percent (11 of 145) knew how to get involved. However, of those who had not attended HTA training (90.7 percent, 146 of 170), a substantial 68.5 percent (100 of 146) expressed willingness to participate in relevant HTA courses.

Regional comparisons revealed that the Asian group had significantly lower participation rates in HTA discussions (10.2 percent, 13 of 127) compared to the non-Asian group (25.6 percent, n = 11 of 43). Despite this, a majority of Asian respondents who had not attended HTA training (64.4 percent, 76 of 118) expressed willingness to participate, although this was lower than the non-Asian group (85.7 percent, 24 of 28).

When comparing the Asian group with non-Asian subgroups, significant differences emerged. The Asian group was less likely to participate in HTA discussions (p = 0.016) and HTA training (p = 0.025) compared to the non-Asian high-income group. However, no significant differences were found between the Asian group and the non-Asian low- and middle-income group (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of patient involvement and learning needs (non-Asian high-income group vs. Asian group vs. non-Asian low- and middle-income group)

Note: p-values obtained from chi-squared test; *know how to participate = 1 missing data; *attend HTA training = 9 missing data; HI = high income; LMI = low and middle income.

Discussion

Our study confirmed that patient awareness of HTA was generally weak in Asia. This situation in Asia was similar to that of low- and middle-income countries in non-Asian regions, with most not knowing what HTA is or how to participate in it. Lack of knowledge about HTA is one of the main burdens preventing patients from participating in HTA (Reference Single, Cabrera, Fifer, Tsai, Paik and Hope22). The European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation (EUPATI) had recommended that education and training be provided to patients to improve their ability to participate in HTA in a meaningful way (Reference Hunter, Facey and Thomas2). Providing patients and patient organizations with the opportunity to participate in training is also one of Health Technology Assessment International (HTAi) quality standard (35). For patients, specific training should include five areas: the purpose of HTA, local HTA processes, collecting and reporting patient information that is most likely to impact HTAs, presenting at committee meeting, and communicating HTA recommendations (18). Considering the relatively low awareness of all aspects of HTA in the Asian group, as shown in our study, future patient education of HTA in Asia should focus more on the basic and be more widespread.

The results of our study indicated that patient involvement in HTA was lacking in Asia, which were consistent with previous country-based surveys (17;Reference Whitty28;Reference Hailey, Werkö and Bakri36). This was the same as in non-Asian low- and middle-income countries, with the majority neither participating in HTA discussions nor attending HTA trainings. This may be partly due to the lack of knowledge of HTA among patients who did not know how to participate, thus resulting in a low participation percentage. Another possible explanation for the low participation rate in HTA training among Chinese individuals, who comprised the largest Asian group (56 out of 127 or 44.1 percent), is their general reluctance to attend. This may be attributed to multilayered institutional, sociocultural, and individual determinants in China. Structurally, insufficient policy frameworks beyond perfunctory informed consent, coupled with significant urban–rural institutional disparities and eroded trust between doctors and patients under marketization, systematically constrain engagement. Culturally, reliance on state guidance and collective decision making suppresses autonomous initiative. Individually, variables such as age, health status, insurance type, and social capital further modulate participation behavior (Reference Zhu37;Reference Zhu and Sui38). Hopefully, among the Asian group who had not received HTA training, a majority of 64.4 percent (76 out of 118) expressed a willingness to participate, which is a positive development. Additionally, an even higher percentage of the non-Asian group (85.7 percent; 24 out of 28) was willing to participate, indicating a strong desire to learn and engage with HTA. These findings bode well for the future of HTA.

Considering the above factors and the strong learning needs, the intervention of an experienced patient advocacy or patient organization may be a good solution. There are some good practices. For instance, in Hong Kong, patient organizations collaborate with health professionals through participatory workshops and consensus meetings, enabling patients to contribute directly to the development of HTA evaluation criteria and priority setting within the public health system. In Australia, Rare Cancers Australia facilitates systematic patient input into bodies such as the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) by coordinating patient testimony sessions and submitting consolidated evidence on treatment impacts from the patient perspective (18). In these practices, patient involvement is embedded in an organization’s political system to ensure effective patient involvement in the HTA process.

Second, policy makers should recognize the critical role of patient advocates and patient organizations in promoting patient involvement in HTA. These groups are more likely to be familiar with HTA and have a greater ability to influence the process. Previous surveys have indicated that most patients are involved in the HTA process through patient organizations (Reference Single, Cabrera, Fifer, Tsai, Paik and Hope22;Reference Whitty28). A randomized controlled trial has also demonstrated the value of patient advocates and organizations as influential members of the public and professional organizations (Reference Boivin, Lehoux, Burgers and Grol39). Therefore, policy makers should integrate patient involvement into the political and educational system of the organization to ensure effective patient participation in the HTA process.

In the past, patient views were often excluded from HTA as they were deemed biased or anecdotal (Reference Facey and Hansen24). Fortunately, there is now recognition of the importance of involving patients in HTA for a comprehensive evaluation. HTA must, therefore, expand its research to encompass a wider range of patient-based evidence and acknowledge patients and patient advocates as “experience-based experts” with the right to participate in the HTA process. Given our study’s findings of low levels of patient awareness and participation in HTA, as well as the strong need for patient education on HTA, research on barriers to patient involvement in HTA and effective methods of patient engagement is imperative. Furthermore, it is crucial to conduct research on the effectiveness of HTA training after it has been implemented.

Limitations

This is the first global baseline survey to explore patient awareness, involvement, and learning needs in HTA, as well as the first to examine patient education preferences. Unlike previous studies that were limited to individual countries, our study provided a valuable opportunity to compare and contrast differences between regions. However, our study had some limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small for a global survey, and the composition of the Asian sample was mixed, with an uneven distribution across countries and a concentration of responses from East and Southeast Asia. The average number of responses from each country was relatively low, which may not be fully representative. This limitation confines the analysis to descriptive statistics and limits generalizable conclusions. Second, the questionnaire design may lead to anchoring bias and low-quality responses. It was observed that participants tended to choose the first option in ranking questions and there were inconsistent responses to the questions. Third, our study used convenience sampling – primarily conducted online and through patient organizations – which may have resulted in significant selection bias. This recruitment strategy likely attracted respondents who were more engaged and health literate, thereby failing to adequately represent the broader patient population. Therefore, our findings may underestimate the poor awareness and involvement of patients in HTA, particularly among the lay population. Furthermore, the questionnaire was only available in Chinese and English, which created a language barrier that limited participation from those who speak other languages. Future studies could use stratified sampling and multilingual instruments to ensure broader representation across Asian subregions.

Conclusion

In Asia, patient awareness and involvement in HTA were low. Comparatively, the awareness and involvement level were even lower in Asian region than in non-Asian high-income regions. Despite the lack of engagement in HTA, the majority of patients expressed a desire to participate, indicating a strong need for education and potential for increased involvement in the future. To promote patient involvement in HTA, it is crucial to leverage the role of patient advocacy or organization and design effective training programs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462325103346.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.