The start of high school poses a challenging developmental and structural transition, even at the best of times. Increasing academic demands often prompt declines in adolescents’ academic performance and engagement (Benner, Reference Benner2011; Benner & Graham, Reference Benner and Graham2009; Roderick, Reference Roderick2003), and the many unknowns of an unfamiliar school environment can elicit considerable psychological distress among adolescents (Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt1993). Indeed, adolescence is a high-risk period for the onset of mental health disorders (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Amminger, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Lee and Ustün2007), and adolescents experience increases in anxiety, depression, and loneliness at the beginning of high school (Barber & Olsen, Reference Barber and Olsen2004; Benner & Graham, Reference Benner and Graham2009). School transitions can also prompt escalations in peer aggression and bullying as students establish status hierarchies in a new environment (Juvonen & Schacter, Reference Juvonen, Schacter, Rutland, Nesdale and Brown2017; Savin-Williams, Reference Savin-Williams1977), and peer victimization is a robust predictor of poor mental health among adolescents, particularly those who recently experienced a high school transition (Krygsman & Vaillancourt, Reference Krygsman and Vaillancourt2019).

For adolescents starting ninth grade during the 2020–2021 school year, the already stressful high school transition was further disrupted by a global crisis: the COVID-19 pandemic. In the Fall of 2020, as the United States reached record high levels of coronavirus cases (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020), many school districts across the country adopted hybrid learning models or completely shifted to online (i.e., remote) instruction. Additionally, ebbs and flows in COVID-19 severity prompted further changes in adolescents’ daily schooling contexts throughout the Fall and Spring semesters, with some students experiencing months of online, hybrid, and in-person learning all within one academic year (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Although we are only just beginning to understand the far-reaching consequences of the pandemic and instructional shifts on adolescents’ social experiences and emotional well-being, emerging evidence indicates escalations in adolescent mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic (Hawes et al., Reference Hawes, Szenczy, Klein, Hajcak and Nelson2021; Racine et al., Reference Racine, Cooke, Eirich, Korczak, McArthur and Madigan2020), with particularly negative consequences for students who attended school remotely, as opposed to in-person (Duckworth et al., Reference Duckworth, Kautz, Defnet, Satlof-Bedrick, Talamas, Lira and Steinberg2021). Although some initial findings suggest that the pandemic prompted stability (Lessard & Puhl, Reference Lessard and Puhl2021) or even declines (Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, Krygsman, Farrell, Landon and Pepler2021) in the prevalence of bullying, it remains unclear whether those adolescents who do experience peer victimization during the pandemic are particularly vulnerable to psychological distress. Additionally, despite evidence for generally adverse effects of remote instruction on adolescent well-being (Duckworth et al., Reference Duckworth, Kautz, Defnet, Satlof-Bedrick, Talamas, Lira and Steinberg2021), it is unknown whether online schooling environments serve a unique function for peer victimized adolescents, who may find relief in peer distance (i.e., physical escape from bullies) or, alternatively, suffer from intensified isolation (i.e., less accessible social support). To address these gaps, the current study employed a three-wave longitudinal design to examine between-person (BP) and within-person (WP) associations between peer victimization and internalizing pathology (i.e., depressive, somatic, and anxiety symptoms) across adolescents’ first year of high school during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also examined whether fluctuations in adolescents’ schooling formats across the school year tempered – or exacerbated – the effects of peer victimization on adolescent internalizing symptoms and whether peer victimization varied in prevalence across in-person versus remote learning contexts.

Peer victimization and internalizing symptoms: BP and WP links

Interpersonal theories of adolescent mental health emphasize that psychological disorders emerge within an interpersonal context (Sullivan, Reference Sullivan1953) and recognize the role of normative developmental transitions in further shaping the emotional effects of social experiences (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Flynn, Abaied, Abela and Hankin2008). Given the salience and developmental significance of peer relationships during adolescence, it is perhaps then unsurprising that peers play a critical role in influencing adolescents’ emotional outcomes (Brown, Reference Brown, Lerner and Steinberg2004). Whereas positive peer relationships can promote adolescents’ sense of self and psychological well-being (Sullivan, Reference Sullivan1953), negative peer experiences threaten adolescents’ social belongingness and contribute to a host of mental health problems (Juvonen, Reference Juvonen, Alexander and Winne2006; Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Zimmer-Gembeck2016). In particular, peer victimization is a common and emotionally impactful form of peer stress during adolescence (Troop-Gordon, Reference Troop-Gordon2017). Population-based studies indicate that approximately one in every three youth experience at least occasional peer victimization (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2016), which can take several different forms, including overt physical and verbal harassment, reputational harm (e.g., rumor-spreading), and relational aggression (e.g., exclusion; Casper & Card, Reference Casper and Card2017). During a developmental period when adolescents are already experiencing heightened vulnerability for the emergence of various psychopathologies (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2005), peer victimization functions as a salient social stressor that elevates adolescents’ risk for concurrent and long-term mental health problems (Juvonen & Graham, Reference Juvonen and Graham2014; Troop-Gordon, Reference Troop-Gordon2017). Indeed, compared to their non-victimized peers, peer victimized adolescents are more likely to exhibit a host of internalizing symptoms, including depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints (Christina et al., Reference Christina, Magson, Kakar and Rapee2021; Gini & Pozzoli, Reference Gini and Pozzoli2013; Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010). Not only do internalizing symptoms contribute to heightened individual suffering during adolescence, but they also elevate the risk for more severe psychopathology and functional impairment later in life (Frye et al., Reference Frye, Perfect and Graham2018).

Although the effects of peer victimization on internalizing symptoms have been well-documented, such research has predominantly been guided by a nomothetic approach, which focuses on how individual (i.e., BP) differences in stress affect health (Abela & Hankin, Reference Abela, Hankin, Nolen-Hoeksema and Hilt2009). For example, adolescents who experience chronic (i.e., repeated) peer victimization over multiple years, compared to adolescents who experience declining or consistently infrequent victimization, are more likely to exhibit depressive and anxiety symptoms (Sheppard et al., Reference Sheppard, Giletta and Prinstein2019). Additionally, adolescents who experience more frequent peer victimization across middle school, compared to those who experience less frequent or no victimization during middle school, report more somatic symptoms (e.g., headaches; nausea; Schacter & Juvonen, Reference Schacter and Juvonen2019). Thus, research guided by a nomothetic framework (i.e., BP approach) provides valuable comparisons between the (mal)adjustment of adolescents who are more versus less victimized by peers, and such studies demonstrate that adolescents who are victimized by peers experience greater risk for internalizing symptoms compared to their non-victimized counterparts.

Notably, however, peer victimization is quite unstable, and only a small proportion of youth experience chronic victimization across multiple years (Pouwels et al., Reference Pouwels, Souren, Lansu and Cillessen2016; Sheppard et al., Reference Sheppard, Giletta and Prinstein2019). Past meta-analytic evidence indicates only moderate stability in peer victimization, even within a single school year, suggesting that negative peer experiences tend to wax and wane over time for many adolescents (Pouwels et al., Reference Pouwels, Souren, Lansu and Cillessen2016). In turn, it is also valuable to examine adolescents’ peer victimization experiences through an idiographic framework, which emphasizes that relative increases or decreases in adolescents’ own peer victimization experiences over time (i.e., WP changes) also meaningfully affect emotional outcomes (Abela & Hankin, Reference Abela, Hankin, Nolen-Hoeksema and Hilt2009; Schacter & Juvonen, Reference Schacter and Juvonen2019). From this perspective, an adolescent is considered to be experiencing a high level of peer victimization when they are victimized more than their typical (i.e., average) level of victimization, regardless of how that level of victimization compares to peers. For example, one five-wave study spanning 8 years found that adolescents experienced greater depressive and anxiety symptoms during years when they were more victimized by peers, compared to years when they were less victimized by peers (Leadbeater et al., Reference Leadbeater, Thompson and Sukhawathanakul2014). Another study found similar evidence for WP links between peer victimization and emotional distress, as well as somatic symptoms, across adolescents’ 3 years in middle school (Schacter & Juvonen, Reference Schacter and Juvonen2019); that is, adolescents exhibited increases in internalizing symptoms during school years when they reported relative increases in peer victimization (i.e., greater than their typical level across middle school). Daily diary research further demonstrates that adolescents experience greater distress on school days when they are victimized by peers, compared to days that they are not victimized by peers (Nishina & Juvonen, Reference Nishina and Juvonen2005). In sum, relative fluctuations in adolescents’ victimization experiences appear to be linked with corresponding changes in emotional well-being, at least over multiple years or on a day-to-day basis. However, less is known about how time-varying associations may unfold within a single school year – particularly following a disruptive school transition – or against the backdrop of a global stressor that poses independent risks to adolescent mental health difficulties. Thus, in the current study, we bridge nomothetic and idiographic perspectives to disentangle BP (time-invariant) and WP (time-varying) effects of peer victimization on adolescents’ internalizing symptoms across the first year of high school during the COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so, we aim to shed light on how both individual differences in peer victimization and WP fluctuations in victimization relate to adolescents’ mental health outcomes across the ninth grade.

The role of schooling context during COVID-19

Although it is well-established that peer victimization heightens the risk for internalizing symptoms, not all peer victimized adolescents experience emotional distress. Developmental psychopathology theories provide a useful framework for understanding such variability, insofar as they emphasize that youth experiencing the same developmental input (e.g., stressor) can exhibit a diverse array of developmental outcomes (e.g., varying levels of psychopathology; Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch1996; Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch2002). Moreover, this theoretical framework emphasizes how ongoing transactions between adolescents and their environments shape subsequent mental health (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1993). Further, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory specifically implicate peer relationships and schools as critical contexts that influence adolescent socioemotional outcomes, both independently and interactively (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner1979). Specifically, Bronfenbrenner proposed that peers and schools represent aspects of the child’s microsystem, exerting proximal influences on developmental outcomes. In addition to independently affecting the child, peers and schools can also interactively shape youth development at the level of the mesosystem. For example, the nature of a student’s peer experiences (e.g., victimization) may vary as a function of their schooling environment, as documented in recent research comparing peer victimization prevalence from before versus during the pandemic (Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, Krygsman, Farrell, Landon and Pepler2021). In turn, drawing from developmental psychopathology and ecological theoretical frameworks, the current study also investigated whether WP associations between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms vary as a function of adolescents’ changing school formats during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing school closures, concerns have been raised about the potentially negative impact of online schooling on adolescents’ peer relationships (e.g., social isolation; cyberbullying) and mental health (e.g., depression, anxiety) (Orben et al., Reference Orben, Tomova and Blakemore2020). In typical times, adolescents spend most of their waking hours in school settings. Not only do schools serve to promote education and learning, but they offer an essential context for peer socialization and emotional development (Eccles & Roeser, Reference Eccles and Roeser2011). Thus, theoretically speaking, the physical distancing and school closures necessitated by the pandemic are likely to interfere with adolescents’ socioemotional adjustment (Lee, Reference Lee2020). Some initial evidence supports this notion. For example, a recent longitudinal study by Duckworth and colleagues (2021) found that high school students in the United States (U.S.) who attended school remotely in the Fall of 2020 experienced greater decreases in social and emotional well-being (i.e., compared to pre-pandemic) than students who remained in in-person school. In a cross-sectional study with Italian middle and high school students, the majority of participants reported feeling sad and missing friends because of school closures (Esposito et al., Reference Esposito, Giannitto, Squarcia, Neglia, Argentiero, Minichetti and Principi2021). Reflecting similar patterns via qualitative analysis, a recent study among U.S. high school students identified mental health, physical health, and missing/not seeing friends as common challenges faced by adolescents during the pandemic (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Rivera, Rushing, Manczak, Rozek and Doom2021).

In contrast to the studies outlined above, some evidence paints a more positive picture of adolescents’ adjustment to hybrid or online instructional formats. In a two-wave study of U.S.-based adolescents attending online school at the beginning of the pandemic, there were no documented changes in adolescents’ life satisfaction from before to during the pandemic (Cockerham et al., Reference Cockerham, Lin, Ndolo and Schwartz2021). One cross-sectional study conducted with 11-to-17-year-olds in the United States found that approximately one-quarter of students perceived that bullying and victimization decreased since the COVID-19 pandemic began (Lessard & Puhl, Reference Lessard and Puhl2021). Additionally, although the Duckworth et al. (Reference Duckworth, Kautz, Defnet, Satlof-Bedrick, Talamas, Lira and Steinberg2021) study documented overall worse well-being among high schoolers attending online school compared to in-person school, these findings only applied to 10th–12th graders; for ninth graders, socioemotional well-being did not significantly differ by school format. Thus, there appears to be heterogeneity in the effects of online schooling environments on adolescent well-being. However, we are not aware of any studies that have tracked the effects of schooling format on adolescents’ mental health over time or considered how other risk factors (e.g., peer victimization) may interact with schooling format to predict distress. The former is important insofar as many students shifted between online and in-person settings across the 2020–2021 school year as COVID-19 restrictions evolved, and the latter can offer insights into for whom remote school settings may be most (or least) detrimental for mental health.

Given inconsistent findings from studies examining the effects of schooling format on adolescent adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is crucial to take a multilevel approach and consider how adolescents’ social vulnerabilities may interact with the broader school context to predict mental health outcomes (Cicchetti & Natsuaki, Reference Cicchetti and Natsuaki2014; Hymel & Swearer, Reference Hymel and Swearer2015). In particular, it is unclear how changes in schooling format affect the well-being of adolescents experiencing developmentally harmful peer difficulties, namely peer victimization. On the one hand, adolescents who are victimized by their peers may find solace and safety in online school environments (referred to herein as the safe haven hypothesis), insofar as they escape the immediate threat of peer attacks and situations that highlight their ostracism (e.g., sitting alone at lunch). Indeed, peer victimized adolescents often feel unsafe at school (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Bellmore and Mize2006; Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, Bennett, Arnocky, McDougall, Hymel and Cunningham2010; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall, Krygsman, Smith and Hymel2014), with bullying frequently occurring in informal public spaces unique to in-person school settings, such as hallways and cafeterias (Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, Bennett, Arnocky, McDougall, Hymel and Cunningham2010). Additionally, past evidence suggests that peer victimized youth show better adjustment in classrooms with fewer students (Cappella & Neal, Reference Cappella and Neal2012), a structure that may be more readily achieved in remote classrooms (Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, Krygsman, Farrell, Landon and Pepler2021). Moreover, newly emerging research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic indicates that students perceive bullying to have remained stable or even decreased since the start of the pandemic and school closures (Lessard & Puhl, Reference Lessard and Puhl2021; Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, Krygsman, Farrell, Landon and Pepler2021). For example, Vaillancourt et al. (Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, Krygsman, Farrell, Landon and Pepler2021) found that whereas approximately 60% of students said they were bullied before the COVID-19 pandemic, only about 40% reported being bullied during the pandemic. These initial findings suggest that remote learning may also alleviate peer victimized adolescents’ fears of re-victimization at school.

On the other hand, peer victimized adolescents may experience amplified distress in online schooling contexts (referred to herein as the hazard hypothesis). Preliminary evidence from studies conducted during the pandemic indicates that many youth receive poorer quality education at home (Thorell et al., Reference Thorell, Skoglund, de la Peña, Baeyens, Fuermaier, Groom, Mammarella, van der Oord, van den Hoofdakker, Luman, de Miranda, Siu, Steinmayr, Idrees, Soares, Sörlin, Luque, Moscardino, Roch, Crisci and Christiansen2021), feel concerned or disoriented by the lack of structure at home (Silk et al., Reference Silk, Scott, Hutchinson, Lu, Sequeira, McKone, Do and Ladouceur2021), and experience school closures as upsetting and socially isolating (Duckworth et al., Reference Duckworth, Kautz, Defnet, Satlof-Bedrick, Talamas, Lira and Steinberg2021; Esposito et al., Reference Esposito, Giannitto, Squarcia, Neglia, Argentiero, Minichetti and Principi2021). Such distress may be all the more amplified among adolescents who feel mistreated or harassed by their peers. Indeed, according to cumulative risk perspectives, youth experiencing an accumulation of risk factors are more likely to experience subsequent adjustment difficulties (Appleyard et al., Reference Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen and Sroufe2005; Morales & Guerra, Reference Morales and Guerra2006), and research conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that the psychological consequences of peer victimization are worse for youth who experience other co-occurring risk factors (e.g., poor teacher-child relationship quality, Troop-Gordon & Kuntz, Reference Troop-Gordon and Kuntz2013; low parent support, Stadler et al., Reference Stadler, Feifel, Rohrmann, Vermeiren and Poustka2010). Additionally, studies examining other types of psychosocial risk factors during the pandemic indicate that greater parental conflict (Magson et al., Reference Magson, Freeman, Rapee, Richardson, Oar and Fardouly2021) and family stress (Green et al., Reference Green, van de Groep, Sweijen, Becht, Buijzen, de Leeuw and Crone2021) exacerbate the mental health symptoms of adolescents attending online school. Although family-related stressors and peer victimization are distinct from one another in many ways, these recent findings minimally suggest a phenomenon of compounding risk as a function of interpersonal vulnerabilities during the pandemic. Online schooling may also exacerbate the distress of victims insofar as these learning environments provide less immediate access to peer and teacher support. For example, recent research suggests that isolation from peers/friends is a major concern among adolescents attending remote school (Esposito et al., Reference Esposito, Giannitto, Squarcia, Neglia, Argentiero, Minichetti and Principi2021; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Rivera, Rushing, Manczak, Rozek and Doom2021), and other work indicates that in-person, compared to online, positive peer interactions are more emotionally rewarding for adolescents (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Do, Choukas-Bradley, Ladouceur and Silk2021). Given that peer connectedness has been shown to buffer the negative effect of peer victimization on internalizing problems (Morin et al., Reference Morin, Bradshaw and Berg2015), remote classrooms could exacerbate peer victimized adolescents’ sense of social isolation and result in greater silent suffering. Additionally, although positive teacher-student relationships can protect adolescents from peer victimization (Sulkowski & Simmons, Reference Sulkowski and Simmons2018) and its negative socioemotional consequences (Cappella & Neal, Reference Cappella and Neal2012), many students perceive decreased support and communication from their teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic (Lessard & Puhl, Reference Lessard and Puhl2021). Thus, peer victimized adolescents could evidence heightened distress when attending online, compared to in-person, school during the pandemic. However, we are not aware of any studies that have directly tested these two competing hypotheses. Therefore, capitalizing on multi-wave data collected as students fluctuated between online, hybrid, and in-person school settings across one school year, another aim of the current study was to investigate whether schooling format modified the effects of peer victimization on adolescent mental health during the pandemic.

Current Study

The goals of the current study were to a) examine BP (time-invariant) and WP (time-varying) associations between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms across the ninth-grade school year during the COVID-19 pandemic; b) test whether WP associations between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms varied as a function of adolescents’ changing schooling format (e.g., online vs. in-person) across the school year; and c) evaluate whether risk for peer victimization varied as a function of adolescents’ changing schooling formats. These research aims were investigated among a sample of ninth graders, given that students’ experiences during the first year of high school can be formative in shaping their subsequent social–emotional adjustment (Benner, Reference Benner2011). For our first aim, drawing upon interpersonal theories of mental health and conceptual frameworks underscoring the importance of both nomothetic (BP) and idiographic (WP) effects of stress on health, we hypothesized that both individual differences in and temporal fluctuations in peer victimization across the ninth-grade school year would be associated with adolescents’ increased depressive, somatic, and anxiety symptoms. Specifically, we hypothesized that adolescents would experience increased internalizing symptoms during study waves when they experienced relative increases in victimization (WP effects) and that adolescents who experienced more victimization across the school year, compared to those who experienced less victimization, would report greater internalizing symptoms (BP effects). For our second aim, which was rooted in developmental psychopathology and ecological theories highlighting transactions between adolescent socioemotional experiences and broader environmental contexts, we examined whether WP associations between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms varied depending on fluctuations in adolescents’ school formats. Specifically, two competing hypotheses were tested. Based on research implying potentially protective effects of remote instruction for socially vulnerable youth, the online school as safe haven hypothesis predicted that relative increases in peer victimization would be more strongly associated with internalizing symptoms when adolescents attended in-person, compared to online, school. Based on research suggesting emotional costs of online peer interactions for victimized adolescents (e.g., less immediate access to peer support), the online school as hazard hypothesis predicted that relative increases in peer victimization would be more strongly associated with internalizing symptoms when adolescents were attending online school. For our third aim, we examined differences in peer victimization frequency depending on schooling format; however, given mixed initial evidence concerning the prevalence of bullying during the pandemic (e.g., Lessard & Puhl, Reference Lessard and Puhl2021; Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, Krygsman, Farrell, Landon and Pepler2021), this aim was exploratory. Given possible differences in internalizing symptoms as a function of participant demographic and contextual factors, all hypotheses were tested while controlling for several potentially confounding participant demographic factors (gender; sexual orientation; ethnicity/race; socioeconomic status) and COVID-19 severity (i.e., local positivity rates) at each data collection wave, allowing us to isolate the unique effects of peer victimization and school format over and above other potentially relevant individual and contextual factors. Given the potential overlap among the three internalizing symptoms, we also control for baseline somatic and anxiety symptoms when predicting depressive symptoms, and vice versa.

Method

Participants and procedure

Data for the current study were drawn from the Promoting Relationships and Identity Development in Education (PRIDE) project, a five-wave longitudinal study evaluating the effectiveness of a brief online identity-based self-affirmation intervention and tracking adolescent adjustment following the transition to high school. Study participants, all of whom had recently started ninth grade, were recruited in the Fall of 2020 via communication with local school administrators, counselors, and teachers. School personnel shared information about the study with students (e.g., via e-flyer or posts on learning management systems), and interested students enrolled online. Participants were eligible for the study if they were in the ninth grade at a high school in Michigan. A waiver of parental consent was obtained, and all participants provided written consent before completing the online surveys. Participants received a $10 e-gift card after completing each survey as compensation. The study was approved by the Wayne State University Institutional Review Board.

In the current study, we examined data collected during the first three waves of the study: November 2020 (W1), February 2021 (W2), and May 2021 (W3). During the W1 survey, participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions for the purposes of the larger intervention: identity affirmation (writing about a social identity that is important to them), values affirmation (writing about a value that is important to them), or control condition (writing about what they did when they woke up). Although intervention effects were not the present study’s focus, we controlled for intervention conditions in all analyses (see Analytic Plan).

At baseline (W1), the sample included 388 adolescents (61% female; 36% male; 3% non-binary, trans, or identifying with another gender; M age = 14.05) recruited from 38 high schools in the state of Michigan, the majority (76%) of which were located in the city of Detroit or Metro Detroit area. The sample was ethnically/racially and socioeconomically diverse, with 46% White, 19% Black, 17% Asian, 6% Arab, Middle Eastern, North African (AMENA), 6% Biracial/Multiethnic, 3% Latinx/Hispanic, 1% American Indian/Native American (AI/NA) and 1% identifying with another race/ethnicity (1% did not report), and schools ranged from 5.94% to 100% in the proportion of economically disadvantaged students (i.e., qualifying for free or reduced priced lunch; data for three schools of the 38 schools were not publicly available). In the majority (60%) of schools, at least half of the student body qualified for free or reduced priced lunch.

Attrition analyses

Of the original 388 participants, 336 (86.6%) completed the T2 survey at 3-month follow-up, and 306 (78.9%) completed the T3 survey at 6-month follow-up; 301 (77.6%) completed surveys at all three time points. Results from a series of chi-square tests and independent samples t-tests indicated that there were no significant differences between participants who participated at all three waves versus those who participated at only one or two waves in terms of baseline (W1) schooling format, county-level COVID-19 positivity rates, peer victimization, depressive symptoms, somatic symptoms, anxiety symptoms, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity/race, or socioeconomic status.

Measures

Participants’ peer victimization experiences and schooling format were assessed at all three waves and examined as both WP (i.e., time-varying; Level 1) and BP (i.e., time-invariant; Level 2) predictors. Three indicators of internalizing symptoms, which were assessed at all three waves, were examined as outcomes: depressive symptoms, somatic symptoms, and anxiety symptoms. Participants’ county-level COVID-19 positivity rates at each survey completion date (W1-W3) were included as a time-varying control variable. Participants’ self-reported gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity/race, socioeconomic status, and intervention condition were taken from the W1 surveys and included as time-invariant control variables.

Peer victimization

Adolescents’ peer victimization experiences were measured at each time point using the Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, Reference De Los Reyes and Prinstein2004). Participants were instructed to think about their experiences over the past 2 months and respond to nine items assessing different forms of peer victimization. The instructions did not specify a particular victimization context (e.g., school vs. online). Three items captured overt victimization (e.g., “A peer threatened to hurt or beat me up.”), three captured reputational victimization (e.g., “Another peer gossiped about me so that others would not like me.”), and three captured relational victimization (e.g., “Some peers left me out of an activity or conversation that I really wanted to be included in.”). Participants responded to each item on a 5-point scale (1 = “Never,” 5 = “A few times a week”). If the participant responded to at least 75% of the scale items within a wave, all nine items were averaged to create an overall peer victimization indicator (αW1 = .85; αW2 = .82; αW3 = .85), where higher scores indicated more frequent peer victimization experiences. Across the three waves of data collection, only one student skipped peer victimization items (two items on the Wave 2 survey). The measure has demonstrated good reliability and convergent validity in prior work with similar age groups (e.g., La Greca & Harrison, Reference La Greca and Harrison2005; Siegel et al., Reference Siegel, La Greca and Harrison2009).

Schooling format

Given that data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, participants indicated their current schooling format (online; hybrid; in-person) at each survey wave. Specifically, participants were asked, “Which of the following best describes your current school situation? Please select all that apply.” The response options included “I physically go to school every day” (in-person school); “I go to school some days and take classes online some days” (hybrid school); “I take all my school classes online” (online school). We also provided one response option concerning in-school regulations, which was not used for the current study: “My school has new social distancing rules (e.g., smaller classes; wearing masks).” Students’ school format at each wave was determined based on their response. Although most students selected only one response, some checked multiple boxes. If students selected that they both “physically go to school every day” and that they “go to school some days and take classes online some days,” they were categorized as “hybrid”; given that some schools incorporated split learning days during the pandemic (e.g., online in the morning; in-person in the afternoon), this combination of responses was considered plausible. If students selected any other combination of multiple responses, all of which yielded implausible scenarios (e.g., taking all classes online and physically going to school every day), their data were considered inconclusive and coded as missing (<5% of participants at each wave). To allow for examination of BP differences in schooling format across the school year, a BP (i.e., time-invariant) variable was also created to indicate the proportion of time points, out of three, that participants spent in completely online school. This variable could range from 0 (i.e., never participated in fully online school) to 1 (i.e., participated in fully online school at all three waves).

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-Revised (CESD-R-10) (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Bagnell and Brannen2010; Radloff, Reference Radloff1977). Participants responded to 10 items based on how they felt over the past week using a 4-point scale (0 = “Rarely or none of the time,” 3 = “Most of the time”). Sample items include “I felt everything I did was an effort” and “I was bothered by things that don’t usually bother me.” The scale has shown strong reliability and validity among adolescent samples (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Bagnell and Brannen2010). Two positively worded items were reverse coded, and if all items were completed then they were summed to create an overall depressive symptoms indicator ranging from 0 to 30 (αW1 = .86; αW2 = .86; αW3 = .85), where higher scores indicated a greater frequency of depressive symptoms. Across the three waves of data collection, only two students skipped depressive symptoms items (one item on Wave 2 and Wave 3 survey, respectively). Based on the recommended cutoff score (>10), 52% of the current sample was considered at risk for clinical depression at baseline (Wave 1).

Somatic symptoms

Somatic symptoms were assessed using the abbreviated version of the Children’s Somatic Symptoms Inventory (CSSI-8; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Beck, Garber and Lambert2009; Walker & Garber, Reference Walker and Garber2018). Participants were asked to report how much they were bothered by eight different somatic symptoms over the past 2 weeks (e.g., “headaches”; “nausea or upset stomach”) using a 5-point scale (0 = “Not at all,” 4 = “A whole lot”). The instrument is highly correlated with the original validated CSSI-24 from which it was adapted (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Garber and Greene1991). If all items were completed, then they were summed into a total score representing participants' overall somatic symptoms (αW1 = .81; αW2 = .82; αW3 = .87), where higher scores indicated greater severity of somatic symptoms. Across the three waves of data collection, there were no item-level missing data for somatic symptoms.

Anxiety symptoms

Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006). Participants responded to seven items based on how they felt over the past 2 weeks using a 4-point scale (0 = “Not at all,” 3 = “Nearly every day”). Sample items included “Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge” and “Worrying too much about different things.” The scale has been widely validated among adolescents, such that GAD-7 scores are strongly associated with clinician-rated youth anxiety symptoms and moderately correlated with depressive symptoms (Mossman et al., Reference Mossman, Luft, Schroeder, Varney, Fleck, Barzman and Strawn2017; Tiirikainen et al., Reference Tiirikainen, Haravuori, Ranta, Kaltiala-Heino and Marttunen2019). If all items were completed, then they were summed to create an overall anxiety symptoms indicator that could range from 0 to 21, where higher scores indicated a greater frequency of anxiety symptoms (αW1 = .91; αW2 = .91; αW3 = .92). Across the three waves of data collection, there were no item-level missing data for anxiety symptoms. Based on established sensitivity and specificity metrics (scores >10 reflect moderate anxiety and >16 reflect severe anxiety; Mossman et al., Reference Mossman, Luft, Schroeder, Varney, Fleck, Barzman and Strawn2017), 24% of the sample had moderate anxiety, and 14% had severe anxiety at baseline (Wave 1).

Control variables

Participants’ county-level COVID-19 positivity rates were recorded at each wave and included as a time-varying (i.e., WP) control variable. Specifically, we used participants’ self-reported zip codes to determine their county of residence. We then searched the COVID Act Now database (U.S. COVID Risk & Vaccine Tracker, 2021) to identify each participant’s county-level COVID-19 positivity rate on their specific survey completion date for each of the three survey waves. All other control variables were collected at the W1 survey and included as time-invariant covariates: gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity/race, socioeconomic status (local median household income based on participants’ self-reported zip codes), and intervention condition.

Analytic plan

Data were analyzed using two-level multilevel modeling in Mplus, where the three repeated measures (Level 1) were nested within participants (Level 2). This approach accounts for correlated residual errors within individuals over time and allows for parsing apart of WP and BP effects (Curran & Bauer, Reference Curran and Bauer2011). The current analyses used full information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors to account for missing data and correct for any normality violations in outcomes, thus allowing all 388 participants who participated at W1 to contribute to analysis estimates.

First, we estimated two-level unconditional means models without any predictors to determine intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the internalizing outcomes. Next, main effects models were estimated to assess whether WP fluctuations and BP differences in peer victimization and schooling format were related to changes in internalizing symptoms (depressive, somatic, and anxiety symptoms) across the participants’ first year of high school. To evaluate whether time-varying associations between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms varied as a function of changes in schooling format, another set of models included interactions between WP peer victimization and WP schooling format at Level 1. Finally, to explore whether the prevalence of peer victimization varied depending on schooling format, a multilevel model estimated the WP and BP effects of schooling format on peer victimization.

To isolate WP effects, peer victimization at Level 1 was person-mean (i.e., group-mean) centered. The Level 1 categorical schooling format variable was represented as two dichotomous dummy-coded variables (hybrid; in-person), where students in completely online school served as the reference group. We also accounted for BP differences in peer victimization (i.e., each participant’s cross-time average; grand-mean centered) and schooling format (i.e., the proportion of waves during which participants attended completely online school) at Level 2. Using these centering methods, a significant WP effect of peer victimization would suggest that when an individual experienced an increase in peer victimization during a study wave (compared to that individual’s average level of peer victimization across the school year), they would also report an increase in the internalizing outcome (i.e., the dependent variable) at the same time point. A significant WP effect of in-person schooling would suggest that when an individual was attending in-person school during a study wave (compared to when that individual was attending online school), they also reported an increase in the internalizing outcome (i.e., the dependent variable) at the same time point.

In all models, time was included as a Level 1 covariate and represented as the number of waves since the beginning of the study (i.e., W1 = 0). Participants’ county-level COVID-19 positivity rates at each wave were also included as a Level 1 (i.e., time-varying) covariate and person-mean centered to facilitate interpretation. At Level 2, we controlled for participants’ gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity/race, socioeconomic status (median household income), intervention condition, and baseline internalizing symptoms (e.g., depressive and somatic symptoms when anxiety was the outcome; anxiety and somatic symptoms when depressive symptoms was the outcome). Gender was represented as two dichotomous dummy-coded variables (male; trans/non-binary/other), where female participants served as the reference group. Sexual orientation as represented as one dichotomous variable where 1 = Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Questioning, or Other (LGBQ+), and straight participants, as the largest group in the sample, served as the reference group. Ethnicity/race was represented as seven dichotomous dummy-coded variables (AMENA; AI/NA; Asian; Black; Latinx/Hispanic; Biracial/Multiethnic; Other), where White participants, as the largest group in the sample, served as the reference group. Median household income, our indicator of socioeconomic status, was scaled (i.e., divided) by 1,000 to facilitate model convergence, and both median household income and baseline internalizing symptoms were grand-mean centered. Participants’ intervention condition was represented as two dichotomous dummy-coded variables (Identity Affirmation, Values Affirmation), where the control condition served as the reference group.

Results

Descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations, and intraclass correlations

Descriptive statistics and frequencies for all demographic (e.g., gender; ethnicity) and contextual (e.g., school format; COVID-19 positivity rates) variables are presented in Table 1. As seen in the table, although the majority (86%) of participants began the school year in online school formats (i.e., when COVID-19 positivity rates were also at their highest), less than half of participants were in online school by the end of the school year. The majority of participants switched school formats at some point during the school year, with only 30% of participants remaining in the same school format across all three waves of data collection.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and frequencies for study variables

Note. LGBQ+ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer+; AMENA = Arab, Middle Eastern, North African; AI/NA = American Indian/Native American.

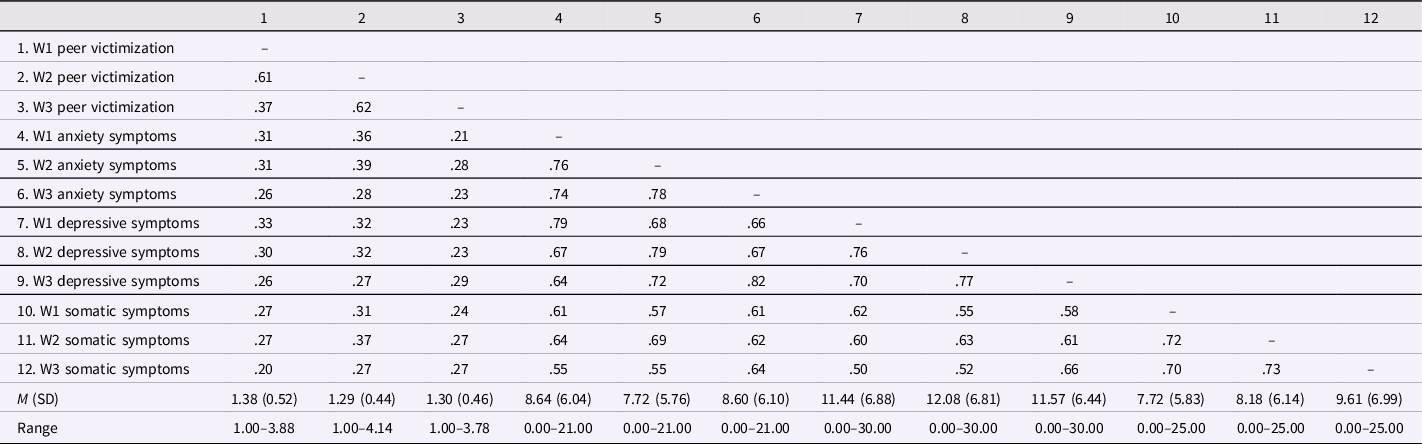

Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics for the main continuous study variables (i.e., W1–W3 peer victimization and internalizing symptoms) are presented in Table 2. Peer victimization exhibited moderate stability across the three study waves (rs = .37–.62), and internalizing symptoms exhibited strong stability across the three study waves (rs = .70–.78). Depressive, somatic, and anxiety symptoms were significantly positively associated within (rs = .61–.82) and across time (rs = .50–.68). Mean levels of peer victimization and internalizing symptoms were relatively low across the three study waves.

Table 2. Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics for W1-W3 peer victimization and internalizing symptoms

Note. All bivariate correlations significant at p < .001.

Unconditional means models were used to estimate the ICC of each internalizing outcome. The ICC statistics, which indicate the ratio of BP variance to the total variance (i.e., BP + WP) were .74 for depressive symptoms, .68 for somatic symptoms, and .75 for anxiety symptoms. That is, approximately 25–30% of the variance in internalizing symptoms was attributable to within-adolescent fluctuations, as opposed to between-adolescent differences, across the school year.

WP and BP associations among peer victimization and internalizing symptoms

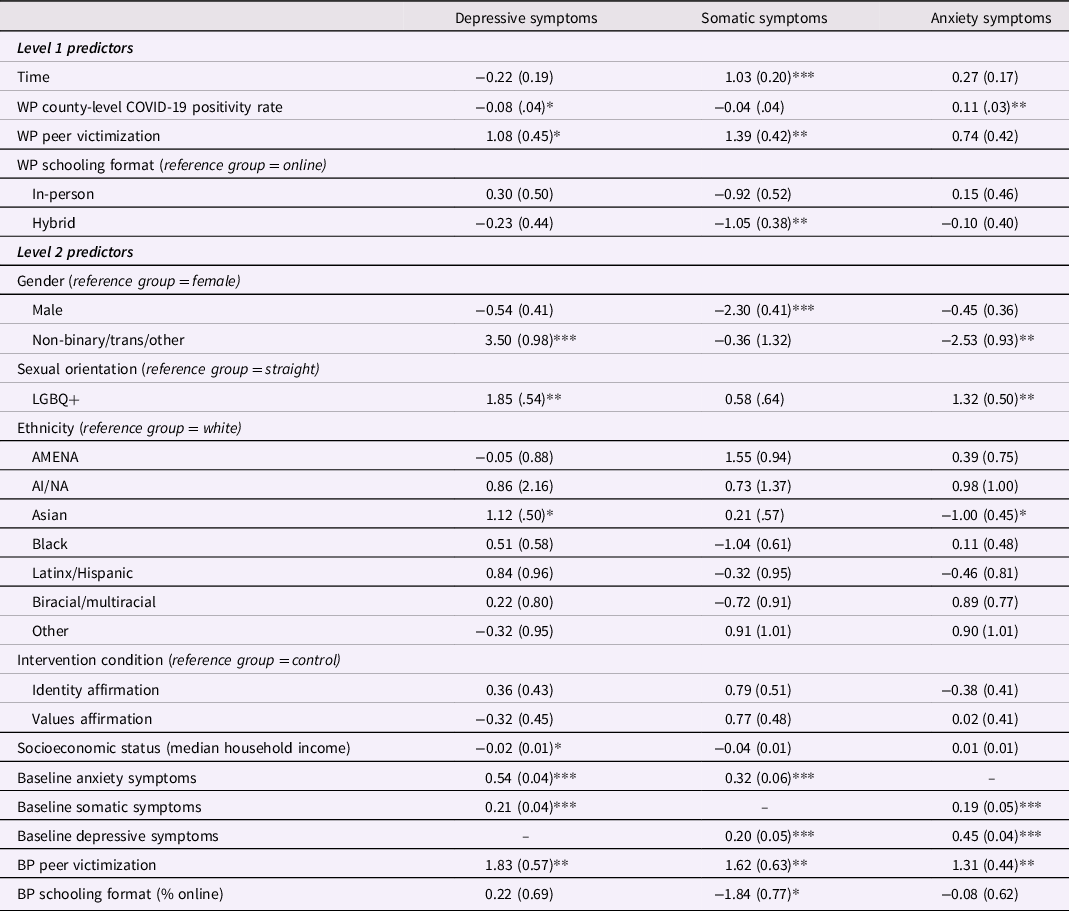

Two-level multilevel models were estimated to test Hypothesis 1 – that both WP fluctuations and BP differences in peer victimization would be linked with adolescent internalizing symptoms. Supporting our first hypothesis, as seen in Table 3, there were significant WP and BP associations between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms, with one exception. At the BP level (i.e., Level 2), adolescents experiencing more frequent peer victimization across the school year, compared adolescents experiencing less frequent peer victimization across the school year, experienced higher overall depressive, somatic, and anxiety symptoms across the school year. At the WP level (i.e., Level 1), when adolescents experienced increases in peer victimization relative to their typical level of victimization, they also reported corresponding elevations in depressive and somatic symptoms. Unexpectedly, WP increases in peer victimization were not significantly associated with anxiety symptoms.

Table 3. Within- and between-person main effects of peer victimization and schooling format on internalizing symptoms

Note. LGBQ+ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer+; AMENA = Arab, Middle Eastern, North African; AI/NA = American Indian/Native American. Unstandardized estimates with standard errors listed in parentheses. WP = within-person; BP = between-person.

* p < .05;

** p < .01;

*** p < .001.

In terms of other predictors, there were no significant WP or BP effects of schooling format on depressive or anxiety symptoms. However, adolescents experienced greater somatic symptoms during study waves when they attended school online compared to when they attended school in a hybrid setting. Additionally, WP increases in county-level COVID-19 positivity rates (i.e., when participants’ local COVID-19 rates were higher than usual) were positively associated with anxiety symptoms but negatively associated with depressive symptoms. Adolescents’ somatic – but not depressive or anxiety – symptoms significantly increased across the school year. Regarding demographic covariates, adolescents identifying as non-binary/trans/other or LGBQ + reported more depressive symptoms than those identifying as female or straight. There were no consistent differences in internalizing symptoms by adolescents’ ethnicity/race or intervention condition, and only depressive symptoms varied as a function of socioeconomic status, such that higher median household income was associated with fewer depressive symptoms.

Moderation by schooling format

For our second research aim, we developed competing hypotheses – that online schooling formats may mitigate (safe haven hypothesis) or exacerbate (hazard hypothesis) the emotional “sting” of peer victimization. To test these hypotheses, moderation analyses were conducted. Specifically, to evaluate whether WP associations between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms varied as a function of adolescents’ schooling format at each wave, two interactions were added to the multilevel models: WP peer victimization X WP in-person school (i.e., contrasted with online school) and WP peer victimization X WP hybrid school (i.e., contrasted with online school). A significant WP interaction would indicate that relative increases in peer victimization are differentially related to relative increases in the internalizing outcome depending on the student’s schooling format at a given wave. That is, the WP analyses use each participant as their own control to assess whether their peer victimization-related distress varied across their different experienced school formats.

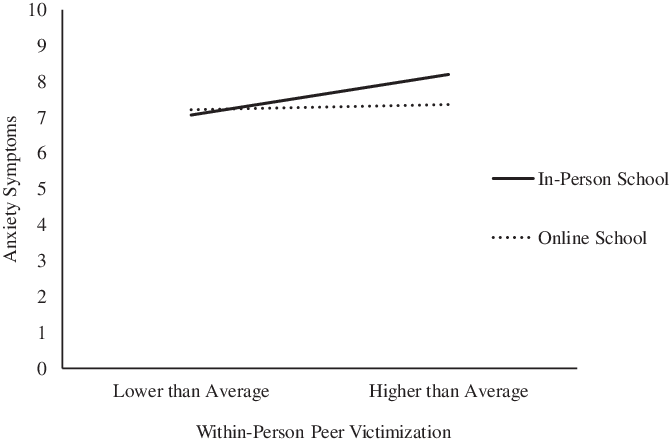

As seen in Table 4, there were no significant WP interactions between peer victimization and schooling format in the models predicting depressive and somatic symptoms. In other words, WP increases in peer victimization were associated with increases in depressive and somatic symptoms regardless of whether adolescents were attending in-person, hybrid, or online school. However, there was a significant WP peer victimization X WP in-person school interaction in the model predicting anxiety symptoms (b = 1.83, p = .020). As seen in Figure 1, probing of simple slopes indicated that the WP effect of peer victimization on anxiety symptoms was significant at study waves when adolescents were attending in-person school (b = 2.16, p < .001), but not at waves when adolescents were attending online school (b = .33, p = .528). That is, consistent with the online school as safe haven hypothesis, WP increases in peer victimization predicted elevations in anxiety symptoms when adolescents were physically attending “traditional” school every day, but not when adolescents were attending school in an online context.

Figure 1. Within-person changes in schooling format moderates the within-person association between peer victimization and anxiety symptoms.

Table 4. Within-person interactions between peer victimization and schooling format predicting internalizing symptoms

Note. Level 2 (between-person) predictors are not displayed in the interest of space. All models controlled for gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, intervention condition, socioeconomic status, baseline internalizing symptoms, average peer victimization, and schooling format (percentage of year online) at Level 2. Unstandardized estimates with standard errors listed in parentheses. WP = within-person.

* p < .05;

** p < .01;

*** p < .001.

Associations between schooling format and peer victimization

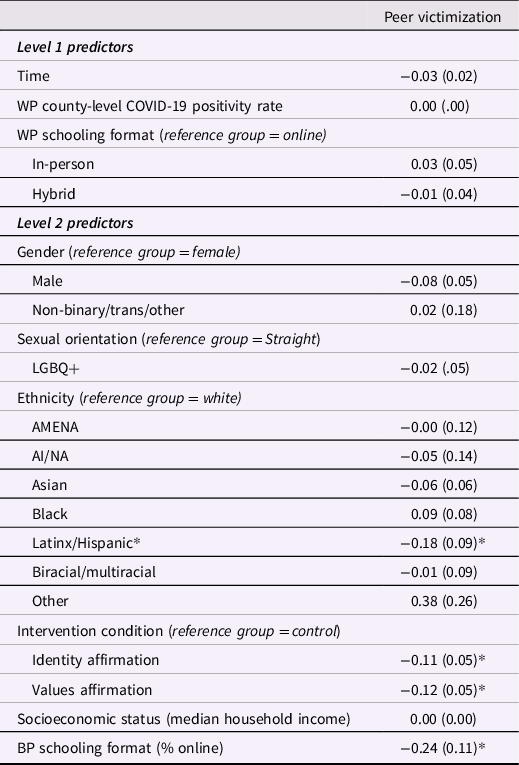

We estimated another multilevel model to investigate our third research question – whether there were WP or BP effects of schooling format on peer victimization frequency. WP schooling format was included as a time-varying predictor of peer victimization at Level 1. BP schooling format (i.e., the proportion of waves spent in online school) was included as a time-invariant predictor of peer victimization at Level 2. These analyses included the same demographic and contextual control variables as the prior multilevel models. As seen in Table 5, there was a significant BP effect of schooling format on peer victimization. Specifically, adolescents who spent less time in online schooling formats across the school year, compared to adolescents who spent more time in online schooling formats across the school year, were more likely to experience peer victimization.

Table 5. Within- and between-person main effects of schooling format on peer victimization

Note. LGBQ+ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer+; AMENA = Arab, Middle Eastern, North African; AI/NA = American Indian/Native American. Unstandardized estimates with standard errors listed in parentheses. WP = within-person; BP = between-person.

**p < .01;

***p < .001.

* p < .05;

Discussion

Although adolescents may be less susceptible than adults to the physical consequences of the COVID-19 virus, the pandemic has been theorized to pose a major threat to adolescents’ healthy social and emotional development (Benner & Mistry, Reference Benner and Mistry2020). Initial evidence from cross-sectional studies indicates high levels of psychological distress among adolescents during the pandemic (Hawes et al., Reference Hawes, Szenczy, Klein, Hajcak and Nelson2021; Racine et al., Reference Racine, Cooke, Eirich, Korczak, McArthur and Madigan2020), and there has been speculation about how moving schooling online affects the well-being of bullied youth in particular (Hurley, Reference Hurley2021). However, to date, there have been no longitudinal studies examining how peer victimization and schooling format may interactively contribute to adolescent mental health vulnerabilities during the pandemic. Further, to our knowledge, no studies have considered how both individual differences and WP fluctuations in social stress or school context dynamically predict adolescents’ psychological adjustment against the backdrop of COVID-19 disruptions. Employing a longitudinal design, the current study addressed these gaps by examining fluctuations in adolescents’ peer victimization experiences, schooling format, and internalizing symptoms across the first year of high school during the pandemic.

Given heightened concerns about youth mental health struggles during the pandemic, it is critical to identify developmentally relevant risk factors that may increase vulnerability to emotional distress. The current study examined the effects of peer victimization, a common and emotionally taxing social stressor that typically peaks following school transitions (Juvonen & Schacter, Reference Juvonen, Schacter, Rutland, Nesdale and Brown2017; Williford et al., Reference Williford, Brisson, Bender, Jenson and Forrest-Bank2011). Consistent with our first set of hypotheses, we found evidence for BP and WP associations between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms across the ninth-grade school year. In terms of BP differences, adolescents who experienced higher average levels of peer victimization across the school year, compared to those who experienced lower average peer victimization, reported more severe depressive, somatic, and anxiety symptoms across the school year. In terms of WP differences, at times when adolescents were victimized by peers more than usual, they also reported greater depressive and somatic symptoms than usual. In other words, adolescents were at risk of internalizing distress when they experienced high average levels of victimization across the ninth grade and when they experienced relative increases in peer victimization – compared to their typical level – during a given study wave. Insofar as both BP and WP effects of peer stress on internalizing symptoms were observed, the results provide support for interpersonal theories of mental health and conceptual frameworks underscoring the importance of both nomothetic and idiographic effects of stress on health (Abela & Hankin, Reference Abela, Hankin, Nolen-Hoeksema and Hilt2009; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Flynn, Abaied, Abela and Hankin2008; Sullivan, Reference Sullivan1953).

Further, our findings are in accord with and extend prior work that has highlighted individual differences in peer victimization and corresponding mental and physical health symptoms (see Christina et al., Reference Christina, Magson, Kakar and Rapee2021; Gini & Pozzoli, Reference Gini and Pozzoli2013; Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010 for meta-analyses), as well as a smaller literature documenting time-varying associations between peer victimization and psychological adjustment on a day-to-day basis (Nishina & Juvonen, Reference Nishina and Juvonen2005) or across multiple years (Leadbeater et al., Reference Leadbeater, Thompson and Sukhawathanakul2014; Schacter & Juvonen, Reference Schacter and Juvonen2019). The current findings are novel insofar as they demonstrate that even relative increases in peer victimization within a single school year are associated with elevated feelings of depression and experiences of physical distress (e.g., headaches, nausea). For students who recently transitioned to high school while navigating a global pandemic, even temporary increases in peer harassment appear to contribute to feelings of significant distress. Such associations were documented over and above the effects of potentially confounding demographic factors and after accounting for adolescents’ proximal COVID-19 landscapes (i.e., local positivity rates). This suggests that peer victimization poses a unique psychosocial risk for elevated mental health during the pandemic, over and above a number of other proximal and contextual influences.

In general, schooling format was not independently related to adolescent internalizing symptoms, with one exception: adolescents experienced greater somatic symptoms during study waves when they attended online, compared to hybrid, school. One possibility is that remote learning requirements reduced opportunities for health-promoting habits (e.g., exercise during P.E. class; high-quality sleep; Cerutti et al., Reference Cerutti, Spensieri, Amendola, Presaghi, Fontana, Faedda and Guidetti2019) and prompted symptoms associated with excessive screen time (e.g., Zoom fatigue), ultimately placing students at greater risk for physical symptoms (Saunders & Vallance, Reference Saunders and Vallance2017). There were no other WP effects of schooling format on internalizing symptoms, suggesting that adolescents’ mental health status did not significantly vary as a function of their changing schooling contexts alone. It is interesting to compare these results with the findings of Duckworth et al. (Reference Duckworth, Kautz, Defnet, Satlof-Bedrick, Talamas, Lira and Steinberg2021), which is the only study to our knowledge that has considered the effect of schooling format on adolescents’ emotional well-being during the pandemic. Controlling for adolescents’ pre-pandemic mental health, Duckworth and colleagues’ findings indicated that high school students attending online school during the pandemic experienced worse social and emotional well-being compared to high school students attending in-person school. Notably, however, follow-up analyses by grade level indicated that these well-being gaps were evident among all but the ninth graders in their study, suggesting that students who transitioned to high school during the pandemic may exhibit unique adjustment patterns.

We also tested competing hypotheses concerning the moderating role of schooling context, evaluating whether the online school setting functioned as a hazard versus safe haven when youth experienced increases in peer victimization. The results provided partial support for the safe haven hypothesis, such that schooling context moderated the WP association between peer victimization and anxiety symptoms, but not depressive or somatic symptoms. Specifically, relative increases in peer victimization were accompanied by relative increases in anxiety symptoms when adolescents attended school in-person but not online. One possibility for the unique protective effects of online school on anxiety, but not the other two internalizing indicators, is that online schooling environments mitigate victims’ self-consciousness around peers. Specifically, insofar as online communication offers greater control over self-presentation, bullied youth may feel more confident in their ability to conceal nerves or other aspects of their appearance that they perceive to be negatively evaluated while hidden behind their computer screen (Lee & Stapinski, Reference Lee and Stapinski2012). Additionally, being bullied while attending online school, where victims are protected from informal or unintended school-based run-ins with bullies (e.g., in hallways; cafeterias), may alleviate peer victimized adolescents’ fears about re-victimization. This explanation was initially supported by the results of our third research aim, which examined WP and BP differences in peer victimization frequency across the school year as a function of schooling format. We found that adolescents who spent more of their school year in online school, compared to adolescents who spent more of their school year in hybrid or in-person school, experienced lower levels of peer victimization. Other recent research further corroborates this pattern, demonstrating that peer victimization decreased in schools utilizing remote learning during the pandemic, whereas schools that returned to in-person learning saw an uptick in peer victimization (Bacher-Hicks et al., Reference Bacher-Hicks, Goodman, Green and Holt2021). Thus, despite the many merits of in-person education for promoting student engagement, connectedness, and emotional well-being (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Dumas and Forbes2020; McCluskey et al., Reference McCluskey, Fry, Hamilton, King, Laurie, McAra and Stewart2021), our finding suggests that online school formats may also provide unique affordances, such as decreased victimization or victimization-related anxiety, for socially vulnerable youth. Thus, supporting developmental psychopathology and ecological theories that highlight heterogeneity in the emotional effects of stress on youth, the current study demonstrated that peer victimization and its relation to internalizing symptoms were partially contingent on adolescents’ broader social environments.

Limitations and future directions

The current study had several strengths as well as limitations. First, this study expands on the predominantly cross-sectional research on adolescent adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic by using a longitudinal design to examine fluctuations in adolescents’ peer victimization, mental health, and schooling format following a developmentally significant school transition. Although the multi-wave design is a strength, we did not have any data from participants before the pandemic or before the ninth-grade school year; therefore, we cannot characterize whether the current patterns represent changes or continuations from adolescents’ previous peer experiences and mental health. Notably, however, average levels of peer victimization in our sample were comparable to those typically observed in pre-pandemic studies using the same measure in similar age groups (e.g., Landoll et al., Reference Landoll, La Greca, Lai, Chan and Herge2015; Tarlow & La Greca, Reference Tarlow and La Greca2021). Because most participants in our sample moved from online to hybrid or in-person formats across the school year (i.e., rather than from in-person to hybrid or online), we also did not examine whether certain types of format transitions were more distressing than others. Future studies could address these limitations by capitalizing on previously collected data (i.e., pre-pandemic) to track whether links between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms vary in strength before and during COVID-19 and across different types of format transitions (i.e., in-person to online vs. online to in-person). Additionally, the data were all self-report. Peer nominations were not tenable given the restrictions of conducting school-based research during the pandemic but would provide an important opportunity to cross-validate the current results across informants. It should also be noted that our measure of peer victimization generally asked about adolescents’ experiences of victimization (e.g., verbal abuse, physical threats, exclusion, rumor-spreading) and did not include specific items about cyberbullying. Although our victimization items were framed broadly and thus could plausibly occur across multiple contexts (e.g., school, neighborhood, online), different patterns could possibly emerge had we included questions that specifically referred to cyber harassment (e.g., sharing embarrassing photos on social media). Lastly, students generally reported quite low levels of peer victimization, and the internalizing symptoms variables were positively skewed; thus, although the use of robust estimation methods (MLR) should have mitigated estimation concerns, it is possible that the variable distributions limited our ability to detect certain significant effects (e.g., interactions).

Conclusions and implications

The first year of high school can pose a stressful disruption to adolescents’ social relationships and well-being under even the best of circumstances. Such challenges were likely further amplified for adolescents who started high school against the unpredictable and ever-evolving backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although there is strong theoretical precedence for anticipating significant mental health ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent development, corresponding empirical evidence is only just beginning to emerge, the majority of which stems from cross-sectional studies that provide a snapshot of youth’s social–emotional adjustment at a single point during the COVID-19 pandemic. The current study employed a longitudinal design to capture the dynamic and changing nature of adolescents’ social experiences, school contexts, and mental health as they navigated the first year of high school during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings highlight the mental health toll of peer victimization throughout this challenging time and indicate that peer victimization-related anxiety was assuaged when adolescents attended online, but not in-person, school. Peer victimization was also less common among adolescents who spent a greater proportion of their ninth-grade school year attending school online, compared to those attending school partially or completely in-person.

In turn, although returns to in-person school will likely be a welcome change for many students who did not excel in online learning environments, schools should also recognize the unique challenges of this transition for adolescents who may have experienced online school as a safe zone rather than risky learning environment. As many schools shift back to in-person learning, it will be essential to focus on building strong teacher and peer support networks for adolescents who may be vulnerable to continued peer victimization and its adverse health effects, recognizing that such students likely felt less anxious in online school environments. School personnel and practitioners may find it useful to conduct routine social–emotional check-ins with students, providing them with a venue to voice any concerns or challenges they have experienced in readjusting to in-person learning. Additionally, teachers are well-positioned to closely monitor the social dynamics of their classroom and identify students who may need extra support (e.g., targets of bullying). Finally, schools can play a central role in connecting adolescents to mental health services by normalizing and destigmatizing students’ experiences of psychological distress, making them aware of internal resources (e.g., school-based mental health centers), and providing resources to low-cost counseling services in their local community. Interdisciplinary partnerships between educators, researchers, and practitioners could offer fruitful opportunities for optimizing adolescents’ well-being as they navigate a continually changing social and educational landscape.

Funding statement

This work was supported by a Society for Research in Child Development Small Grant for Early Career Scholars (HLS; AJH) and a Wayne State University Research Grant (HLS).

Conflicts of interest

None.