Introduction

Socialisation programmes are recommended by pet professionals and veterinary experts to help promote normal kitten social and behavioural development (Crowell-Davis Reference Crowell-Davis2007; Seksel Reference Seksel2008; Seksel & Dale Reference Seksel, Dale and Little2012; Landsberg et al. Reference Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman, Seksel, Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman and Seksel2013; American Veterinary Medical Association [AVMA] 2015). Socialisation refers to a learning process in which an animal develops valanced associations with people, animals, environments, and other stimuli. Socialisation is often discussed in the context of the sensitive period of socialisation (Karsh & Turner Reference Karsh, Turner, Turner and Bateson1988; McCune Reference McCune1995; Landsberg et al. Reference Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman, Seksel, Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman and Seksel2013). A sensitive period refers to a specific time-frame in which the effect of experience on the brain is particularly strong. When experience during this time-frame is essential for normal development, the time-frame is described as a critical period (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2004). This period is often characterised by an increase in neural plasticity (Rohlfs Domínguez Reference Rohlfs Domínguez2014), with a gradual decline in plasticity into adulthood. Increased neural plasticity is characterised by an increase in the ability of the nervous system to be modified by experiences (von Bernhardi et al. Reference von Bernhardi, Bernhardi, Eugenín, von Bernhardi, Eugenín and Muller2017). When discussing the sensitive period of socialisation, most refer to a time-frame in which the effects of socialisation are particularly impactful. Some differences exist in the literature regarding whether the socialisation window is referred to as a sensitive (e.g. Foerder & Howard Reference Foerder and Howard2024; Graham et al. Reference Graham, Koralesky, Pearl and Niel2024a) or critical (e.g. Karsh & Turner Reference Karsh, Turner, Turner and Bateson1988; Ahola et al. Reference Ahola, Vapalahti and Lohi2017) period. For the current study, this time-frame will be referred to as a sensitive period.

The proposed sensitive period of kitten socialisation is between 2–7 weeks old (Karsh & Turner Reference Karsh, Turner, Turner and Bateson1988), or up to 9 weeks old (McCune Reference McCune1995; AVMA 2024) and is sometimes described as being lifelong (Petak Reference Petak and Petak2022; AVMA 2024), which implies the possibility of continuation past this window. Sensitive periods are characterised as functional descriptions of neurological mechanisms rather than specific age ranges and may be mediated via external environmental and biological factors (Hensch Reference Hensch and Hensch2018; Gabard-Durnam & McLaughlin Reference Gabard-Durnam and McLaughlin2020). Thus, the end of the socialisation sensitive period is likely not static and may vary across individuals. Much of a kitten’s proposed socialisation sensitive period occurs before they are adopted or enter their forever home. Thus, socialisation experiences prior to entering a forever home are very important (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Arnott, Graham, Niel, Ward and Ma2024), however new kitten owners may not receive information on these experiences. Kitten socialisation programmes are offered at eight weeks of age (Landsberg et al. Reference Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman, Seksel, Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman and Seksel2013) and some programmes may accept kittens up to eight months old (Vitale Reference Vitale and Stelow2022). Typically, classes like these are not offered for kittens younger than eight weeks old, likely due to the increased risk of disease (Landsberg et al. Reference Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman, Seksel, Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman and Seksel2013). Since kittens are enrolled in socialisation programmes after the sensitive period of socialisation, experiences after this period may have reduced effectiveness compared to experiences during the sensitive period; however, no research has assessed this. In addition, many shelters do not allow adoptions of kittens younger than eight weeks of age, and many US states have legislation that prohibit the sale of kittens younger than eight weeks of age (e.g. Illinois, 225 I.L.C.S. § 605/2.2; Michigan, M.C.L. 287.335a; Minnesota, M. S. A. § 347.59).

Socialisation programmes provide an opportunity for kittens to develop positive associations with new stimuli, such as unfamiliar people, conspecifics, environments, and objects. Although the content of kitten socialisation programmes varies, kittens and owners often engage in a multi-week programme where owners learn about cat (Felis catus) health and behavioural management, and kittens are exposed to various stimuli, including a carrier, travel, an unfamiliar environment, unfamiliar people, and unfamiliar conspecifics (Seksel Reference Seksel2008; Seksel & Dale Reference Seksel, Dale and Little2012; Landsberg et al. Reference Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman, Seksel, Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman and Seksel2013). There is a lack of research examining the impacts of socialisation programmes on future kitten health and behaviour, although some research has examined the impact of various aspects of socialisation programmes on kittens and adult cats of varying ages. For example, research suggests that carrier training in cats older than eight months may reduce future stress during exposure to carriers and travel (Pratsch et al. Reference Pratsch, Mohr, Palme, Rost, Troxler and Arhant2018); kittens exposed to unfamiliar people show reduced fear responses to unfamiliar people later in life (Collard Reference Collard1967); and kittens exposed to complex (versus barren) environments may show increased cognitive skills by greater success at a maze task (Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Warren and Abbott1965). Additionally, most behavioural research examining kitten socialisation has focused on exposures during the socialisation period, in particular, handling (Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Warren and Abbott1965; Karsh Reference Karsh, Katcher and Beck1983; Karsh & Turner Reference Karsh, Turner, Turner and Bateson1988; McCune Reference McCune1995; Casey & Bradshaw Reference Casey and Bradshaw2008). This handling research suggests that handling kittens for 5–15 min per day during early life is associated with a reduced latency to approach novel humans (Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Warren and Abbott1965; Karsh Reference Karsh, Katcher and Beck1983; Karsh & Turner Reference Karsh, Turner, Turner and Bateson1988; McCune Reference McCune1995).

Overall, socialisation programmes often prioritise owner education, which may be particularly beneficial for educating owners about cat behaviour, at-home management, and routine procedures (e.g. nail trims) needed throughout a cat’s life (Landsberg et al. Reference Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman, Seksel, Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman and Seksel2013; Blackwell Reference Blackwell2022). While many kitten socialisation programmes offer in-person classes, some organisations and behaviour professionals also conduct synchronous or asynchronous virtual classes. Virtual classes focus on owner education (i.e. litter-box maintenance, importance of vertical space, etc), provide guidance on socialisation activities to perform with kittens, and answer owner questions on kitten ownership and management. However, research is needed to elucidate the benefits and limitations of in-person versus virtual programmes on owner education and kitten socialisation experiences.

Although many socialisation programmes focus on kittenhood, some veterinary resources recommend continuing socialisation practices until at least 12 months of age (AVMA 2024). Limited research exists on the impacts of socialisation practices on neural plasticity into adulthood. One study in rats (Rattus norvegicus) suggests that housing with environmental enrichment versus standard laboratory caging in adulthood enabled an eye previously damaged due to sight deprivation during the sensitive period, to make a full recovery (Sale et al. Reference Sale, Maya Vetencourt, Medini, Cenni, Baroncelli, De Pasquale and Maffei2007). This finding suggests that exposure to environmental enrichment into adulthood, a practice often included in the curriculum of socialisation classes, may continue to impact animal development past sensitive periods. However, given the lack of information on the impact of socialisation practices past kittenhood, there is a need for further research.

Although kitten socialisation is often recommended by pet care professionals, to date there has yet to be any research exploring cat owner attitudes towards socialisation programmes for kittens and cats. Thus, here, we surveyed US cat owners using an online quantitative questionnaire to examine: (1) owner experiences with kitten and cat socialisation programmes; (2) where owners receive their socialisation information; (3) interest in enrolling in a future socialisation programme and factors impacting interest; and (4) attitudes regarding important components of socialisation programmes.

We predicted that participant demographic factors would be most predictive of interest regarding a future kitten socialisation programme. We predicted that women would be more likely than men to indicate interest, given previous research has found higher support for animal welfare by women compared to men, not to mention the formation of greater attachments to animals (Eldridge & Gluck Reference Eldridge and Gluck1996; Knight et al. Reference Knight, Vrij, Cherryman and Nunkoosing2004; Herzog Reference Herzog2007). We also predicted that those who participated in a socialisation class in the past would be interested in doing so again in the future. Furthermore, we predicted that those in a higher socio-economic status would be more likely to indicate interest in a kitten socialisation programme due to an increased amount of disposable income. Similarly, those willing to pay a higher amount to participate in a kitten socialisation programme would be more interested in enrolling. Finally, we predicted that individuals whose current cat is experiencing behaviour problems would be more interested in enrolling in a future socialisation class as they may be seeking help with their cat’s behaviour.

Materials and methods

This research was reviewed and deemed exempt (e.g. does not require registration) by the UC Davis Institutional Review Board Administration (IRB# 1883274). Participation was voluntary and respondents could withdraw at any time. Prior to completing the questionnaire, participants were presented with a consent form detailing the duration of the study and an overview of the types of questions they would be asked. Participants could only access the questionnaire if consent to participate was provided.

Questionnaire

A quantitative questionnaire was created using online survey software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA), and participants needed to be current cat owners living in the US who were 18 years of age or older. Questions (n = 45; see Supplementary material) included: participant demographics (n = 14); caregiver experiences with socialisation (n = 8); information about participant’s cats (n = 13); where caregivers receive socialisation information (n = 8); and ratings of various aspects of socialisation (n = 2). Participant demographic questions included age, gender identity, US state/territory of residence, past cat-related work experience, and self-rating of socioeconomic status. Given the broad range of income and cost of living throughout the US, the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (SSS; developed by Adler et al. Reference Adler, Epel, Castellazzo and Ickovics2000) was used to measure socioeconomic status. This scale asks participants to rate themselves out of ten rungs on a ladder, where they think they belong; ten indicates the most well off in their community and one indicates those who have the least. This scale is intended to assess where participants feel they stand financially in their community and been shown to be more predictive of a variety of measures of psychological well-being (Adler et al. Reference Adler, Epel, Castellazzo and Ickovics2000). Cat ownership questions included ownership of kittens and/or adult cats, the number of cats currently owned as the primary caregiver, and frequency (always, often, sometimes, rarely, never) of various cat behaviour issues.

The second section of the questionnaire asked if the participant had heard of kitten and adult cat socialisation programmes before, and whether they had attended a socialisation programme with a past pet. Questions asked where participants had received information on cat and/or kitten socialisation (e.g. internet, animal shelter, breeder, veterinarian, pet store), where past and current cats or kittens had been obtained (i.e. animal shelter, breeder, pet store, bred at home, gifted from friend/family, found on the street, other), and age of cat/kitten at the time of acquisition from each selection. Based on where they indicated they had obtained a past cat/kitten, they were asked to indicate socialisation information provided by various pet care professionals (i.e. shelter staff, breeders, pet store staff) and all respondents were asked to indicate socialisation information provided by their veterinarian. Types of socialisation information listed were: training to respond to commands; playtime with other kittens; interaction with animals other than cats; interaction with new people; education about common behavioural issues; getting kittens comfortable with nail trims; getting kittens comfortable with handling; carrier training; leash/harness training; and ‘other’ in which participants were able to input any additional aspect not mentioned above. Response options included: yes, no, not sure/cannot remember.

Participants were asked if they had taken part in a kitten socialisation programme in the past (yes, no). If participants selected yes, they were shown additional questions about the programme (n = 4) including: the approximate length of the programme (in hours); programme format (online asynchronous or synchronous, in-person, both in-person and online); and location (veterinary clinic, shelter facility, breeder’s house/facility, local university, private behaviour consulting business, other). Finally, participants were asked to indicate (yes, no, unsure/do not remember) aspects included in the programme (i.e. body language/behaviour, training cat to respond to commands, playtime with other kittens, kitten interaction with new people, etc).

Participants were asked if they would enroll in a future kitten, and adult cat socialisation programme (yes, no, unsure). If yes was selected, participants were shown a question asking to select reasons (e.g. improve cat/kitten’s co-operation at the veterinary clinic, improve cat/kitten’s health, getting help for existing cat/kitten behaviour problems, reducing future cat behaviour problems) they want to enroll. If no was selected, participants were shown a question asking to select reasons (e.g. price, transportation challenges, travel with cat/kitten is too stressful, no need for cat/kitten to be exposed to new animals) they would not want to enroll. If unsure was selected, participants were shown both questions asking to select reasons that they would and would not want to enroll.

Participants were then asked to rate the importance (not at all important, somewhat important, moderately important, very important, extremely important) of various aspects of a socialisation programme. Aspects mirrored those in the earlier question regarding information they have received from veterinarians about socialisation, with the addition of: education about cat body language; litter-box training; and homework (tasks for the owner to complete at home). Participants were also asked to rate the importance (5-point Likert scale) of socialisation during a cat’s various life stages: 2–9 weeks, 10 weeks–1 year old, over 1 year–6 years old, 7–10 years old, 11+ years old. These age ranges were chosen based on the AAHA/AAFP Feline Life Stages guidelines (Quimby et al. Reference Quimby, Gowland, Carney, DePorter, Plummer and Westropp2021), with the addition of the purported kitten socialisation period, 2–9 weeks (Karsh & Turner Reference Karsh, Turner, Turner and Bateson1988; McCune Reference McCune1995).

Finally, participants indicated using an open-ended text box numerical entry question, how much they would be willing to pay for a hypothetical kitten socialisation programme. This hypothetical programme (Landsberg et al. Reference Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman, Seksel, Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman and Seksel2013) included a 1-h in-person class each week for three weeks. During this programme kittens are introduced to unfamiliar kittens and people, and cat owners are given homework to complete in between classes.

The questionnaire was advertised through snowball sampling via postings on social media sites (i.e. Facebook and Twitter/X), as well as an article advertising recruitment in a US-based online news outlet. Data collection took place from July 6th to July 8th, 2022.

Data analysis

Analyses were conducted using jamovi (v 2.4) and Rstudio (v 4.3.1, R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) statistical software. All responses were retained for participants meeting the inclusion criteria and reaching the end of the survey, indicated by answering the final question regarding the price they were willing to pay for a hypothetical kitten socialisation class. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages) were generated for each question. For ease of analyses, state of residence was grouped based on geographic region as determined by the United States Census (Northeast, South, Midwest, and West). Gender was also grouped into three categories (man, woman, non-binary/third gender), with responses to the ‘other’ category being grouped with either ‘non-binary/third gender’ or omitted due to supplying an answer other than their gender identity. Additionally, the SSS scale responses were grouped into three categories, with 1–4 indicating lower SSS, 5–7 indicating middle SSS, and 8–10 indicating upper SSS. To create a binary variable depicting the presence or absence of behaviour problems in their current cat, the ‘never’ and ‘rarely’ responses were grouped as absent, while ‘sometimes’, ‘often’, and ‘always’ were grouped as present. Finally, responses on willingness to pay for a hypothetical kitten socialisation programme were grouped into quartiles: < $US45, $US45-74, $US75–99, and $US100+.

Logistic regression

A multinomial logistic regression model was used to assess the relationship between the outcome variable ‘willingness to enroll in a future kitten socialisation programme (yes, no, unsure)’ and explanatory variables including participant demographics (age, SSS, gender, geographic area, region of the United States, and work history), presence or absence of behaviour problems in current cat, and the monetary amount participants were willing to pay for a future kitten socialisation programme. Given the large number of explanatory variables, and the aim of creating a parsimonious model, bivariate analyses (outcome variable with each explanatory variable) were performed using a liberal P-value of P ≤ 0.20 to assess eligibility for inclusion into the multivariable model (Dohoo et al. Reference Dohoo, Martin and Stryhn2014). Model building used backwards elimination in which all eligible explanatory variables were included and those with the most non-significant (P > 0.05) contribution to the outcome were taken out one-by-one until only variables which were significant (P < 0.05) remained in the model. Plausible interactions based on prior predictions were also included in the model building process. To reduce the potential for Type 1 errors, a holm-bonferroni adjustment was used when multiple comparisons included four or more pairs. Model fit was assessed using AIC/BIC with a lower value preferred.

Results

Participants

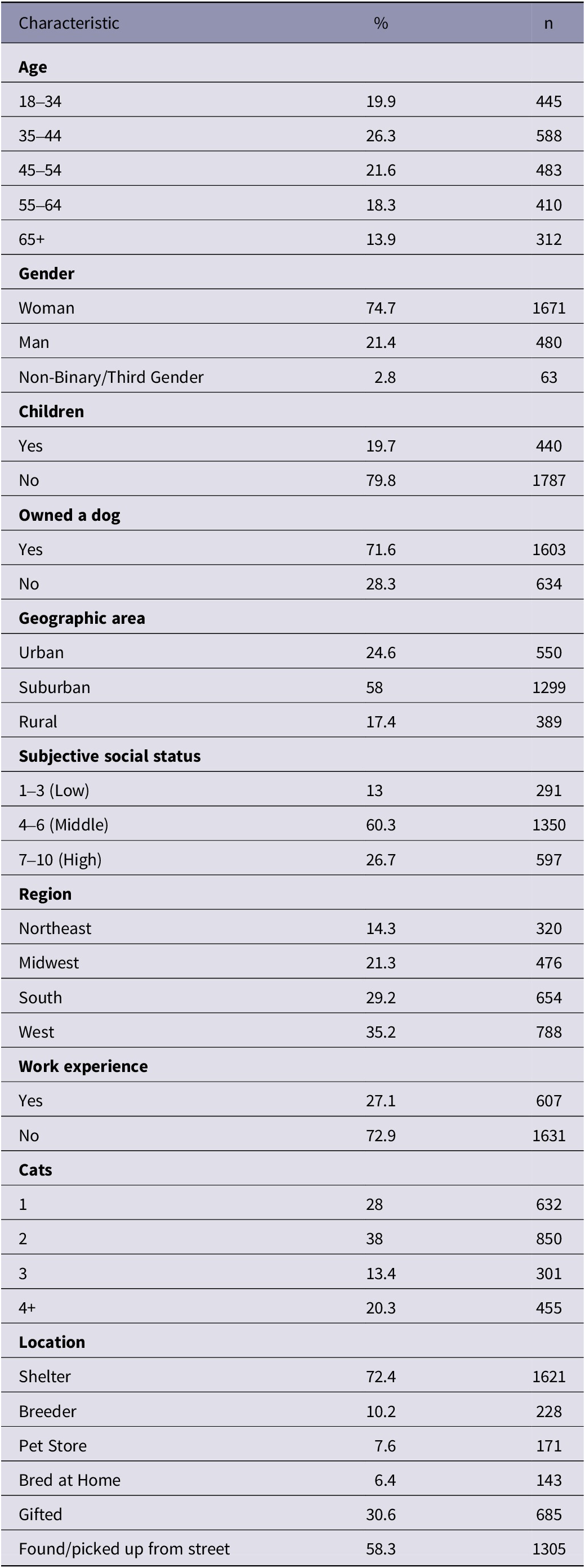

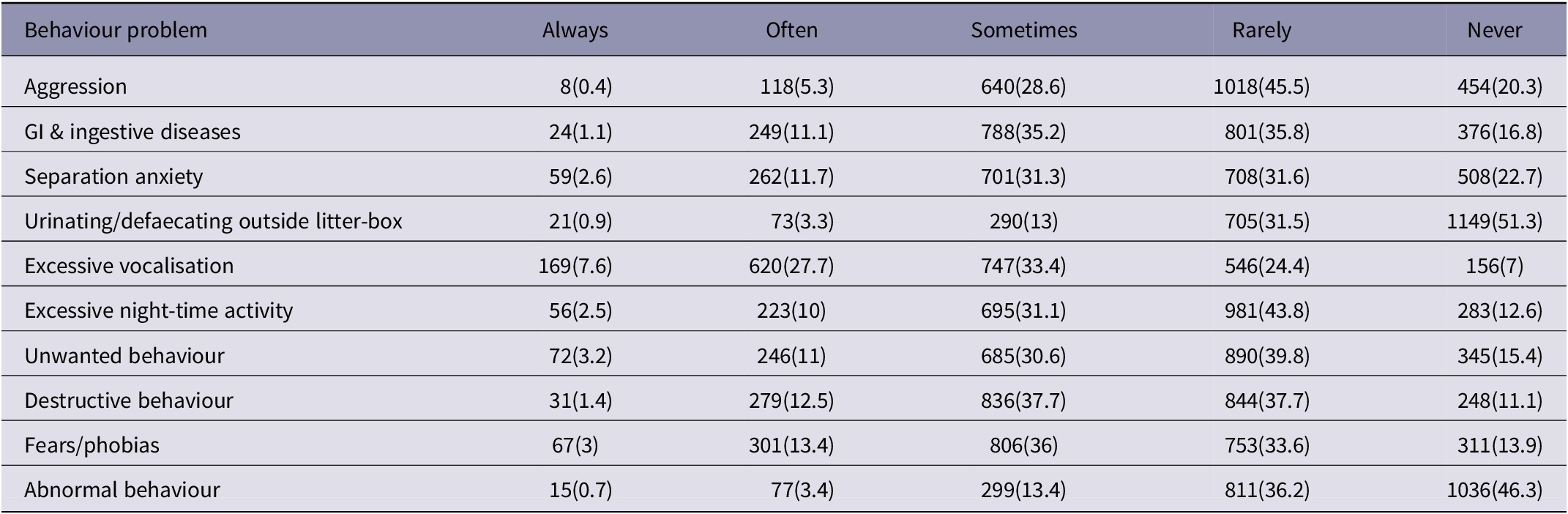

A total of 2,238 responses were analysed, and the number of responses varied among the questions. Participants frequently indicated they were 35–44 years old (26.3%; Table 1), women (74.7%), and did not have children (79.8%). Participants frequently reported living in the western (35.2%) or southern (29.2%) regions of the US, indicated being in the middle SSS category (60.3%), had owned a dog at some point in their life (71.6%), and had not worked with cats in a professional setting in the past (72.9%). The behaviour problem most frequently reported being present in their current cat was excessive vocalisation (68.7%; Table 2). Of those who indicated working with cats in a professional setting (n = 607), participants most frequently indicated working in a shelter (43.3%), as kennel staff (30.8%), in the veterinary field (30.3%), and/or as a cat sitter (28.0%). Those who worked with cats in a professional setting indicated working in the position(s) for 1–5 years (42.8%), 6–15 years (22.4%), less than 1 year (17.8%), or 16+ years (17.0%).

Table 1. Demographic descriptive information for US cat owner participants (n = 2,238) who completed an online questionnaire on their attitudes towards kitten and adult cat socialisation programmes

Table 2. Frequency of various behaviour problems reported to occur by cat owner participants’ current cat (n = 2,238), presented as frequency(%)

Participants frequently indicated owning one (28.2%) or two (38.0%) cats, and most indicated adopting a past or current cat from a shelter (72.4%) or finding their cat on the street (58.3%). Most participants who indicated adopting from a shelter (n = 1,622), reported adopting a cat/kitten between 10 weeks to < 1 year old (56.7%), 1–6 years old (42.1%), 0–9 weeks old (29.9%), and/or ≥ 7 years old (7.9%). Those who indicated purchasing a cat/kitten from a breeder (n = 249) and/or pet store (n = 188), most often indicated purchasing their kitten between 10 weeks–1 year old (breeder: 65.8%; pet store: 52.9%) followed by 0–9 weeks old (breeder: 32.9%; pet store: 36.5%), 1–6 years old (breeder: 10.5%; pet store: 20.0%) and/or ≥ 7 years old (breeder: 0.0%; pet store: 1.2%).

Participants’ interest in a future socialisation programme varied by age of cat; participants most frequently indicated interest in a future programme (kitten: 50.4%; adult: 38.6%), while some were unsure (kitten: 30.9%; adult: 36.8%), or indicated no interest (kitten: 18.8%; adult: 24.6%). Participants were willing to spend a mean (± SD) of $US92.73 (± 83.24; min: $US0, max: $US1,000) on a proposed hypothetical kitten socialisation programme.

Information about socialisation

Most participants indicated they had never heard of kitten or adult socialisation programmes (kitten: 69.3%; adult: 73.5%), while some had heard of these programmes (kitten: 26.6%; adult: 21.9%) or were unsure (kitten: 4.0%; adult: 4.5%).

Participants indicated getting their information about socialisation from the internet (52.3%), veterinarians (31.2%), books (20.6%), animal shelters (20.3%), professional behaviourists (6.3%), pet stores (4.3%), breeders (2.1%), and/or groomers (0.6%).

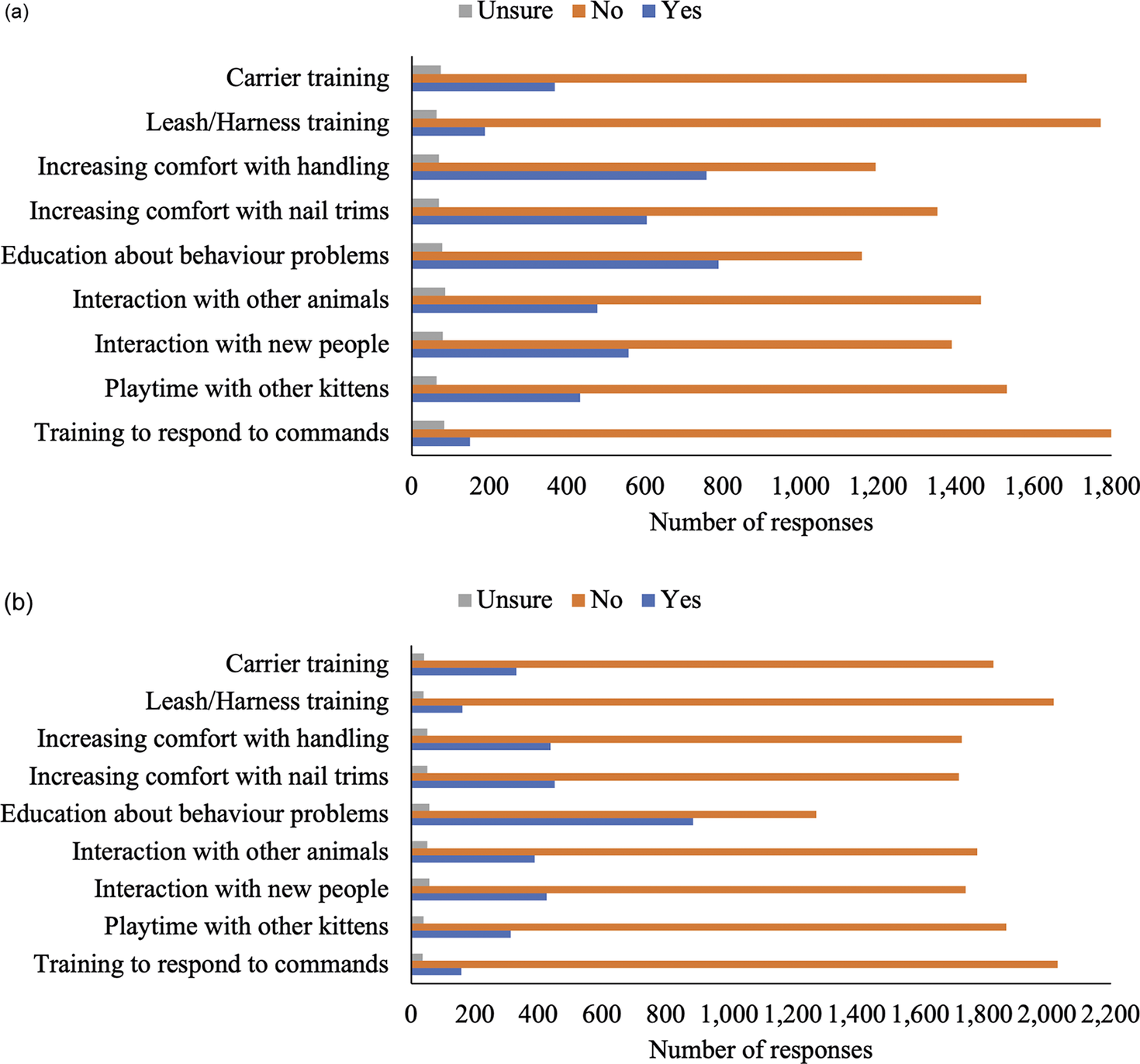

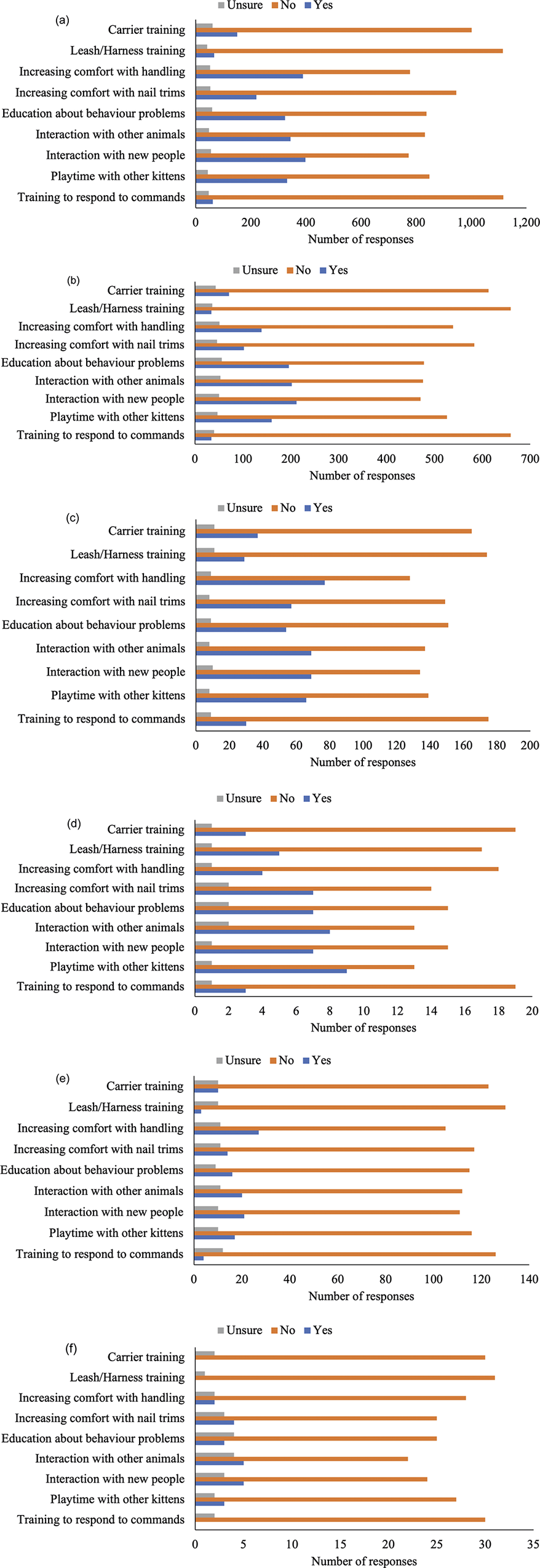

Next, questions asked about socialisation information received during kitten/adult cat adoption and during veterinary visits. Information participants (n = 2,238) received from veterinarians about various socialisation topics for kittens and adult cats are presented in Figures 1(a) and (b). Socialisation information participants received from shelter staff, breeders, and pet stores during a kitten and/or adult cat adoption are presented in Figures 2(a)–(f). In summary, most respondents (> 50%) indicated not receiving information on each aspect of socialisation from veterinarians, shelter staff, breeders, and/or pet stores.

Figure 1. Cat owner reports of information received regarding different aspects of (a) kitten (n = 2,021–2,033) and (b) adult cat (n = 2,200–2,225), socialisation information from their veterinarian. Total participant responses varied for each question.

Figure 2. Cat owner reports of information received regarding different aspects of socialisation upon adoption or purchase from an (a) shelter - kitten (n = 1,213–1,226), (b) shelter - adult cat (n = 727–733), (c) breeder - kitten (n = 213–214), (d) breeder - adult cat (n = 23–24), (e) pet store - kitten (n = 140–143) and (f) pet store - adult cat (n = 31–32). Total participant responses varied for each question.

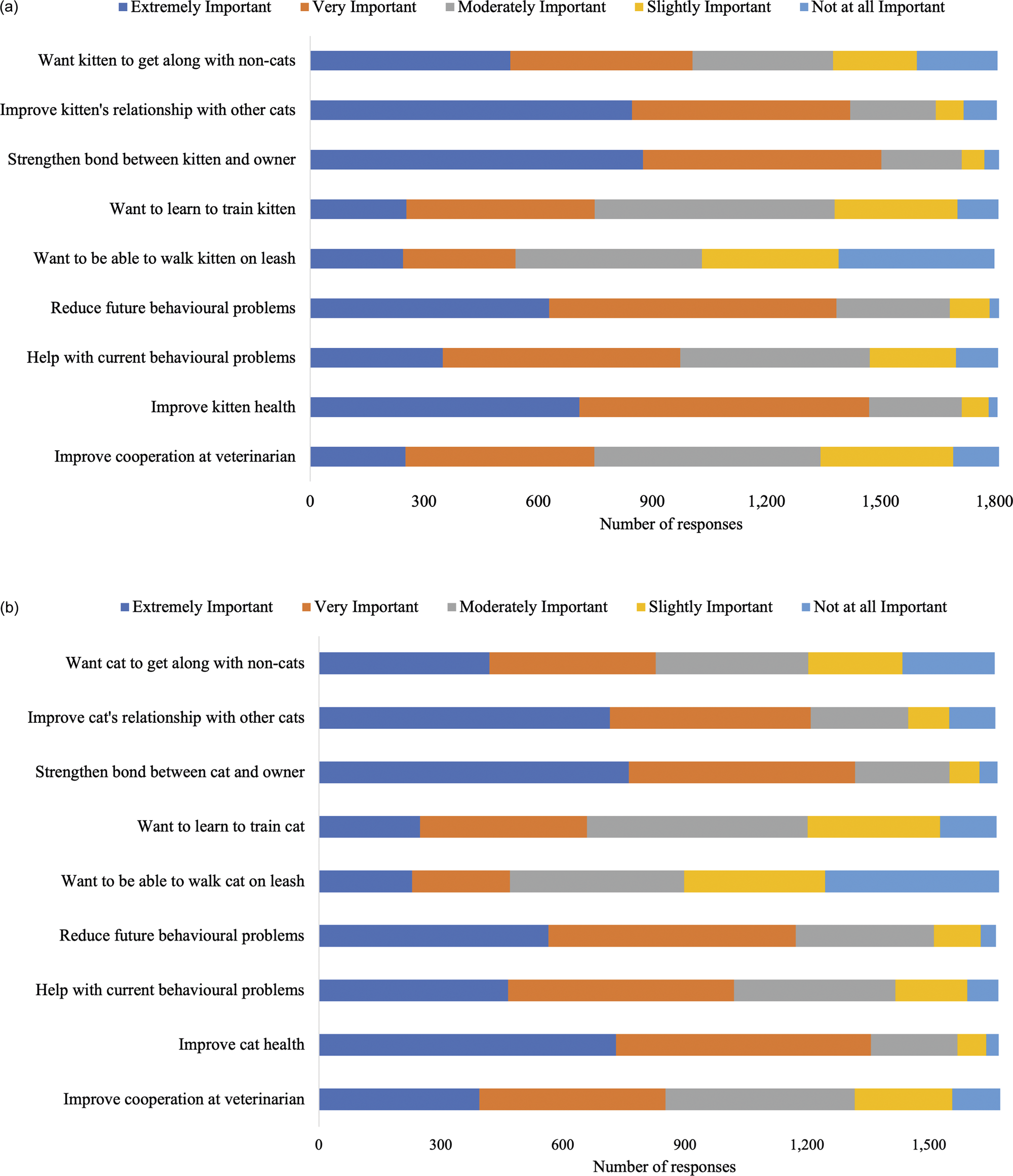

Figure 3. Cat owner ratings regarding the importance of various components of socialisation programmes for (a) kittens (n = 2,203–2,213) and (b) adult cats (n = 2,199–2,214). Total participant responses varied for each item.

Aspects of socialisation ranked by participants as being the most important (> 80% indicated very or extremely important) to include in a socialisation programme for kittens were: ways to reduce problem behaviours (87.0%; Figure 3[a]); education about body language (85.8%); and getting kittens comfortable with handling (83.1%). For adult cats, participants ranked the most important (> 80% indicated very or extremely important) aspects of socialisation programmes as education about body language (86.8%; Figure 3[b]), and ways to reduce behaviour problems (83.3%).

Enrolling in socialisation programmes for kittens and/or adult cats

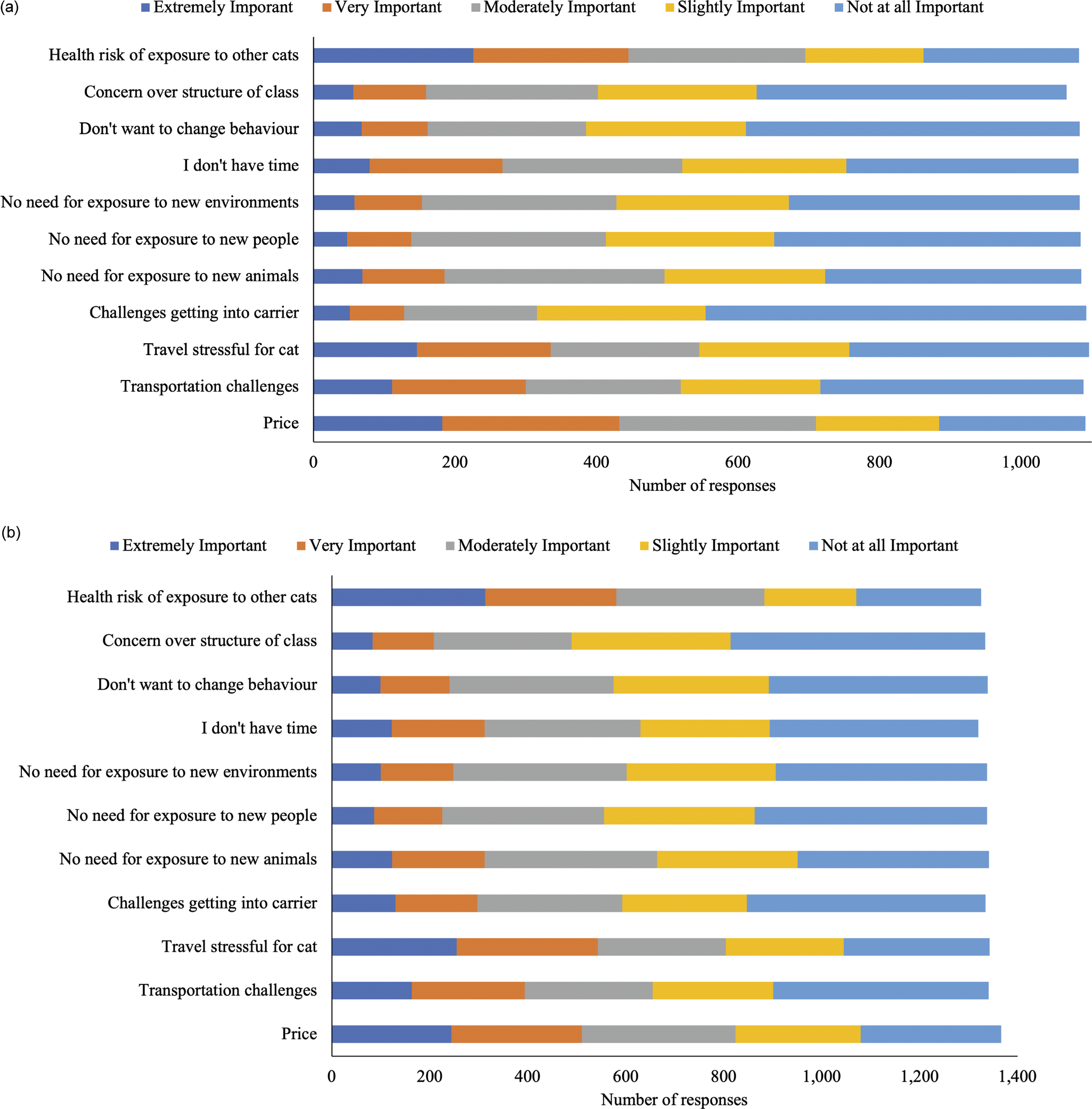

Aspects rated as the most important (> 75% indicated very or extremely important) reason for their decision to enroll in a future socialisation kitten and/or adult cat programme were strengthening the bond between the kitten/adult cat and the owner (kitten: 83.1%; Figure 4[a]; adult cat: 79.0%; Figure 4[b]) as well as improving kitten/adult cat health (kitten: 81.4%; adult cat: 81.2%).

The reason most frequently rated as very or extremely important for participants not wanting to enroll in a future kitten and/or adult cat socialisation programme was health risks related to exposure to other kittens/cats (kittens: 41.1%; Figure 5[a]; adult cats: 43.8%; Figure 5[b]). Price was also frequently listed as an important reason not to enroll in a future kitten socialisation programme (39.6%), and concerns about travel-related stress for adult cats (40.4%) was another reason given frequently.

Previous experience with kitten socialisation programmes

Thirty-two respondents indicated having participated in a kitten socialisation programme in the past, either in person (50.0%), online (synchronous: 6.3%; asynchronous: 25.0%) or both in-person and online (18.8%). These programmes were conducted in a shelter (43.8%), veterinary clinic (18.8%), private behaviour consulting business (12.5%), breeders house (6.3%), university (3.1%), or other (e.g. cat rescue, online conference, library; 15.6%) and took an average of 8 h 59 min (min: 1 h, max: 36 h) to complete.

Those who had participated in a previous kitten socialisation programme (n = 32) indicated that ‘getting kittens used to handling’ was included in every programme (100.0%). Common components of socialisation programmes included lessons on cat body language (yes: 81.3%; no: 15.6%; unsure: 3.1%), playtime with other kittens (yes: 90.6%; no: 9.4%), kitten interaction with new people (yes: 87.5%; no: 12.5%), interaction with animals other than cats (yes: 68.8%; no: 25%; unsure: 6.3%), education about common behavioural problems (yes: 78.1%; no: 21.9%), getting kittens comfortable with nail trims (yes: 62.5%; no: 34.4%; unsure: 3.1%), carrier training (yes: 59.4%; no: 31.3%; unsure: 9.4%), and homework (yes: 65.5%; no: 21.9%; unsure: 12.5%). Components not commonly included in socialisation programmes were leash/harness training (yes: 34.4%; no: 56.3%; unsure: 9.4%), and training to respond to commands (yes: 40.6%; no: 50.0%; unsure: 9.4%).

Interest level in future kitten socialisation programme

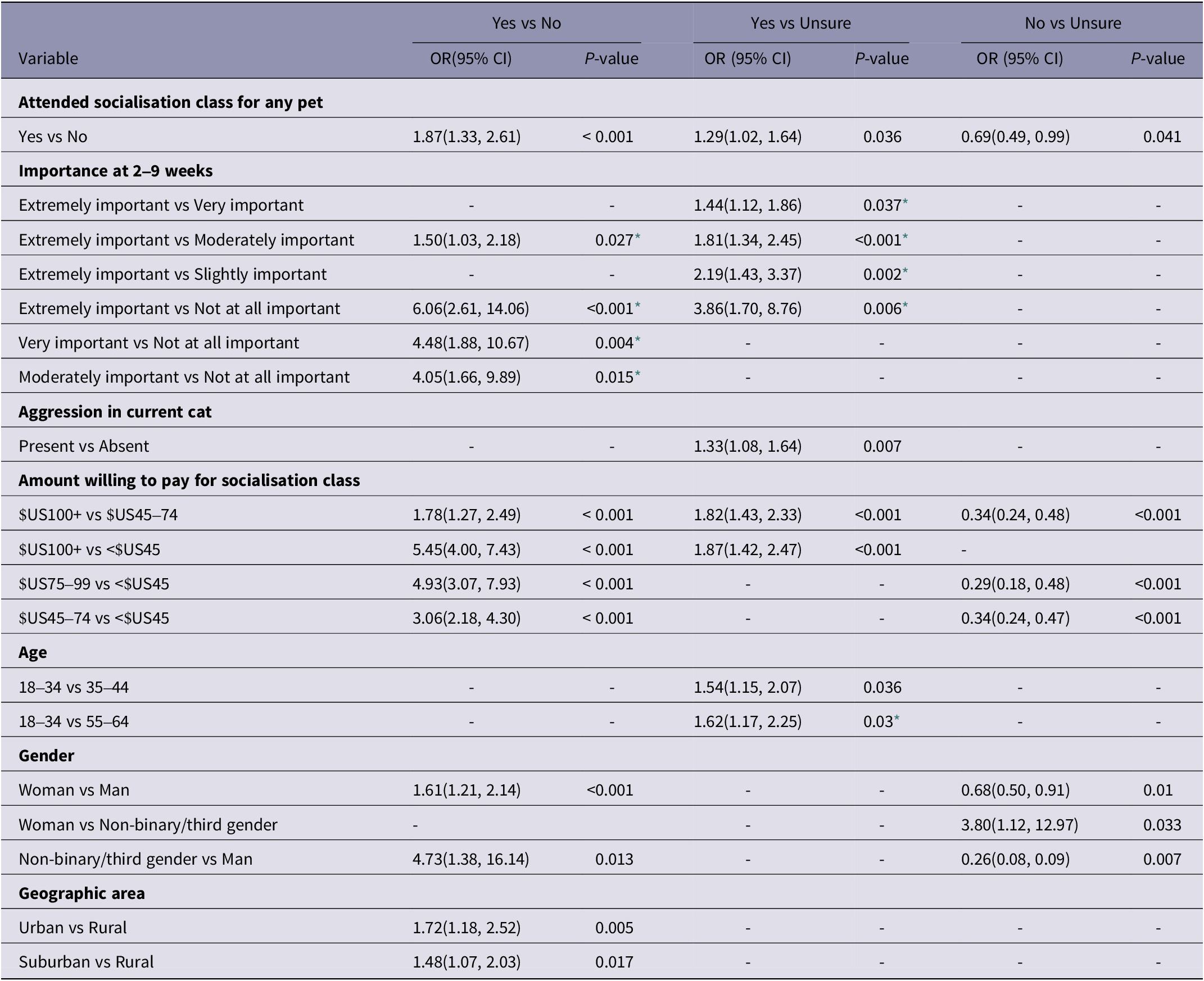

Factors influencing interest in participating in a future kitten socialisation programme were participant age, gender, and geographic area (rural, urban, suburban), whether participants had attended a socialisation programme in the past for any pet, the presence of aggression in current cat, ratings of importance of socialisation at different life stages, and the amount participants were willing to pay for a hypothetical socialisation programme. Table 3 reports regression model results with associated ORs, 95% CIs, and P-values.

Figure 4. Cat owner ratings of importance regarding potential reasons to enroll in a future (a) kitten (n = 1,799–1,811) or (b) adult cat (n = 1,661–1,675) socialisation programme. Total participant responses varied for each item.

Table 3. Multinomial logistic regression results showing significant predictors of cat owner participant interest (yes, no, unsure) in a future kitten socialisation programme (n = 2,214), presented with P-values, odds ratios, and 95% confidence intervals

* Adjusted P-value using holm-bonferroni

Figure 5. Cat owner ratings of the importance of reasons not to enroll in a future (a) kitten (n = 1,064–1,096) or (b) adult cat (n = 1,320–1,367) socialisation programme. Total participant responses varied for each item.

Discussion

Approximately half of the study participants indicated interest in a future kitten socialisation programme, however less than 2% indicated ever having participated in a past programme. It is likely that few participants have experience with kitten socialisation programmes due to a lack of knowledge, given that most indicated they had never heard of a socialisation programme for kittens. Nevertheless, participants indicated being willing to spend an average of $US92 on a standard three-week kitten socialisation programme, suggesting participants recognised the potential value of these programmes.

The most frequent reason participants gave for not wanting to enroll their kitten in a socialisation programme was health risks associated with exposure to other kittens. There is always a risk of pathogen exposure when pets are exposed to conspecifics or other species. To minimise risks, veterinary recommendations suggest kittens should receive their first set of core vaccinations at least 14 days before the first class and should not show evidence of illness or disease (Hetts et al. Reference Hetts, Heinke and Estep2004; Overall et al. Reference Overall, Rodan, Beaver, Carney, Crowell-Davis, Hird, Kudrak and Wexler-Mitchel2005; Crowell-Davis Reference Crowell-Davis2007; Landsberg et al. Reference Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman, Seksel, Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman and Seksel2013; AVMA 2024; Squires et al. Reference Squires, Crawford, Marcondes and Whitley2024). These guidelines also suggest that the benefits of socialisation programmes outweigh disease risks associated with enrolling pets into programmes prior to receiving their full set of core vaccines. Classes conducted in a controlled environment, such as a disinfected indoor space, may introduce fewer disease risks than a less-controlled environment such as an outdoor green space where there may be increased risks of pathogen exposure (Stull et al. Reference Stull, Kasten, Evason, Sherding, Hoet, O’Quin, Burkhard and Weese2016). In puppies, one study suggests that those vaccinated with the first round of parvovirus vaccine who had attended a socialisation programme, were at no greater risk of parvovirus infection than those who had not attended classes (Stepita et al. Reference Stepita, Bain and Kass2013), suggesting that these classes do not pose excess disease risks. However, the purported sensitive period of socialisation in kittens ends earlier than in puppies (2–7 or 9 weeks versus 3–12 or 14 weeks, respectively; Freedman et al. Reference Freedman, King and Elliot1961; Scott & Fuller Reference Scott and Fuller1965; Karsh & Turner Reference Karsh, Turner, Turner and Bateson1988; McCune Reference McCune1995). This means the sensitive period of socialisation has likely passed by the time kittens receive their first set of vaccines. Since many shelters do not adopt out kittens younger than eight weeks of age, kitten fosters and shelter staff should be targeted to implement various aspects of socialisation during the sensitive period of socialisation. Another potential reason participants indicated health risks as a top reason to not enroll a kitten in a socialisation programme, may be related to this research being conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, respondents may have been more cautious of disease risks at the time of data collection.

Accessing kitten socialisation programmes may be a significant barrier for owners who are interested in enrolling, as in-person programmes may be difficult to find. Offering virtual classes may help reduce barriers related to transportation and distance that may interfere with participants’ ability to access these programmes. Alternatives to in-person socialisation programmes include synchronous and asynchronous online classes. A virtual setting may allow a greater focus on education, for example, education on cat body language and behaviour. This is important, given that educating owners about normal cat behaviour may help reduce reports of misbehaviour in pets (Grigg & Kogan Reference Grigg and Kogan2019).

Notable factors that were predictive of interest in a future kitten socialisation class were participant gender, the presence of aggression in their current cat, participation in a past programme with any pet, and geographic area (urban, suburban, rural). Our results suggest women are more likely than men and non-binary individuals to enroll in a future kitten socialisation programme. Previous studies which have assessed cats in a veterinary clinic often report a majority of participating owners as women (Shaw et al. Reference Shaw, Bonnett, Roter, Adams and Larson2012; Boone et al. Reference Boone, Bain, Cutler and Moody2023), which may suggest that women are more active participants in their cat’s care compared to men. Women have a long history of close attachments to cats (Frasin Reference Frasin, Frasin, Bodi, Bulei and Dinu Vasiliu2022) and have been found to speak and interact with their cats more than men do (Mertens & Turner Reference Mertens and Turner1988; Mertens Reference Mertens1991). One study suggests that 79% of participants categorised pet cats as either ‘family’ or ‘children’ in the home (Bouma et al. Reference Bouma, Reijgwart and Dijkstra2021) and as women are typically expected to fulfill a more caregiving role in the family, it may be that they are more interested in participating in cat care activities such as socialisation classes.

Participants attending a past socialisation class with any animal were also more likely to indicate interest in enrolling in a socialisation programme compared to those that had not attended a class before. These results are encouraging and suggest that pet owners that have attended classes in the past recognise the benefits of such programmes. Additionally, those in current possession of a cat with an aggression-related behaviour problem were more interested in enrolling in a future socialisation programme. These participants were more likely to respond ‘yes’ as opposed to ‘unsure’, for enrolling in a future programme. This suggests that the presence of a serious cat behavioural issue, such as an aggression-related problem, may motivate cat owners to participate in a socialisation programme in an attempt to manage this problem. Aggression towards people or animals is often listed as a primary reason for relinquishment or return to shelters (Salman et al. Reference Salman, Hutchison, Ruch-Gallie, Kogan, New, Kass and Scarlett2000; Casey et al. Reference Casey, Vandenbussche, Bradshaw and Roberts2009) and is a primary concern for new adopters (O’Connor et al. Reference O’Connor, Coe, Niel and Jones-Bitton2017). Interestingly, three other cat behaviour problems were frequently reported by participants, although these were not associated with interest in enrollment in a future kitten socialisation programme: excessive vocalisation; destructive behaviour; and fears/phobias. Previous research suggests a high prevalence of these cat behaviours in the home (Morgan & Houpt Reference Morgan and Houpt1989; Heidenberger Reference Heidenberger1997; Grigg & Kogan Reference Grigg and Kogan2019), and reports that many cat owners (> 45%; n = 547) are not ‘bothered at all’ by their cat’s excessive vocalisation, destructive behaviours, or fear and anxiety (Grigg & Kogan Reference Grigg and Kogan2019). However, cat owners are recommended to take a proactive rather than a reactive approach to behaviour problems by enrolling in a socialisation programme soon after adoption.

Individuals who live in urban and suburban geographic areas were more likely to indicate interest in enrolling in a future kitten socialisation programme, compared to those living in rural environments. This may point to cultural differences that exist in rural regions of the US regarding the role of cats in society. It may be that barn cats (semi-feral cats who live and hunt on a farm) are more common in rural areas, with farmers specifically seeking out and adopting these animals with the aim of reducing the rodent population on their property (‘Barn & Garden Cat Adoptions’ undated; Overstreet Reference Overstreetundated; Kitts-Morgan et al. Reference Kitts-Morgan, Caires, Bohannon, Parsons and Hilburn2015). Thus, perceiving cats as working animals may reduce interest in a socialisation programme. However, research elucidating differences in attitudes towards cat ownership between rural, suburban, and urban areas is needed.

Despite most participanting cat owners indicating not being educated about kitten socialisation by pet care professionals (veterinarians, shelter staff, etc), many indicated that various aspects of socialisation were very or extremely important. Individuals emphasised the importance of education about body language and problem behaviours, as well as getting kittens comfortable with handling. These three aspects of socialisation are routinely recommended for inclusion in socialisation programmes for kittens (Overall et al. Reference Overall, Rodan, Beaver, Carney, Crowell-Davis, Hird, Kudrak and Wexler-Mitchel2005; Seksel & Dale Reference Seksel, Dale and Little2012; Landsberg et al. Reference Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman, Seksel, Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman and Seksel2013; Blackwell Reference Blackwell2022). Other routinely recommended practices had less owner interest, such as training to respond to commands and interaction with other cats. This may be related to commonly believed myths that cats are ‘asocial’ and/or ‘untrainable’ (Overall et al. Reference Overall, Rodan, Beaver, Carney, Crowell-Davis, Hird, Kudrak and Wexler-Mitchel2005; Seksel & Dale Reference Seksel, Dale and Little2012; Blackwell Reference Blackwell2022). However, domestic cats are well established as being social (Suchak et al. Reference Suchak, Piombino and Bracco2016; Vitale Reference Vitale and Stelow2022), and research suggests training programmes to be beneficial for cats in the shelter (Bollen Reference Bollen and Bollen2015; Kogan et al. Reference Kogan, Kolus and Schoenfeld-Tacher2017; Grant & Warrior Reference Grant and Warrior2019), although more research is needed regarding the appropriate age to begin training kittens to respond to commands (Graham et al. Reference Graham, Pearl and Niel2024b).

In lieu of information from pet care professionals, participants indicate receiving most of their information on socialisation for kittens from the internet, with some referencing internet/tv personalities such as Jackson Galaxy (n = 20). Although many reputable online socialisation resources exist (e.g. AVMA undated; Ellis Reference Ellisundated), caregivers may not know where to find reputable sources and their search may lead to misinformation. It is recommended that pet care professionals educate kitten and adult cat owners on socialisation and where to access reliable information on socialising their new pet. Veterinary recommendations surrounding socialisation are centered around addressing behaviour concerns of the cat owner (AAHA-AVMA 2011), although some veterinary resources offer explicit recommendations for when and how best to socialise kittens in early life and up to one year old (Overall et al. Reference Overall, Rodan, Beaver, Carney, Crowell-Davis, Hird, Kudrak and Wexler-Mitchel2005; AVMA 2015, undated). For example, a number of socialisation recommendations suggest encouraging owners to use positive reinforcement and allow the cat to progress at its own pace (AVMA undated). The American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) emphasises exposure to new environments and people, as well as training using positive reinforcement (Overall et al. Reference Overall, Rodan, Beaver, Carney, Crowell-Davis, Hird, Kudrak and Wexler-Mitchel2005). Research suggests that owners who were provided advice for preventing behaviour problems by a veterinary behaviourist at the first appointment were less likely to report behaviour problems ten months later than those who did not receive advice (Gazzano et al. Reference Gazzano, Bianchi, Campa and Mariti2015). This finding suggests that education provided by veterinarians at a kitten’s first veterinary appointment may benefit the human-animal bond as well as the cat’s success in the home. Although owner education on cat and kitten behaviour is important, reports suggest veterinarians receive little education on cat behaviour and welfare during veterinary school (Shivley et al. Reference Shivley, Garry, Kogan and Grandin2016). In a nationwide survey of over 1,000 veterinarians, more than 90% reported not feeling that they had received sufficient cat behaviour training at veterinary school (Kogan et al. Reference Kogan, Hellyer, Rishniw and Schoenfeld-Tacher2020), and another survey of graduating veterinary students showed that less than 30% of 366 students surveyed indicated feeling prepared by their clinical behaviour curriculum (Calder et al. Reference Calder, Albright and Koch2017). This reflects the need for veterinary school curricula to provide an increased emphasis on cat behaviour and welfare, as well as best practice at-home management information.

Although veterinary recommendations include kitten socialisation classes for preventing behaviour problems in adulthood (Hetts et al. Reference Hetts, Heinke and Estep2004; Crowell-Davis Reference Crowell-Davis2007; Seksel Reference Seksel2008; Landsberg et al. Reference Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman, Seksel, Landsberg, Hunthausen, Ackerman and Seksel2013), no research has examined the impact of these programmes on current and future behaviour and health outcomes, nor on owner knowledge and management of their cat in the home. Elsewhere, research has assessed the impact of socialisation programmes on puppy health and behaviour. Retrospective analyses suggest that dogs reported to have attended puppy socialisation classes in the past show a decrease in reactivity to unfamiliar humans and dogs outside the household (Blackwell et al. Reference Blackwell, Twells, Seawright and Casey2008; Casey et al. Reference Casey, Loftus, Bolster, Richards and Blackwell2014), as well as reduced fear-related responses to loud noises such as thunderstorms or vacuum cleaners (Cutler et al. Reference Cutler, Coe and Niel2017). Other research incorporating owner questionnaire pet assessments (C-BARQ: Hsu & Serpell Reference Hsu and Serpell2003; Puppy Walker Questionnaire: Asher et al. Reference Asher, Blythe, Roberts, Toothill, Craigon, Evans, Green and England2013), in which puppies either took or abstained from a socialisation class, has found that puppies who attended a socialisation class had lower levels of reported touch-sensitivity and non-social fear (González-Martínez et al. Reference González-Martínez, Martínez, Rosado, Luño, Santamarina, Suárez, Camino, de la Cruz and Diéguez2019), as well as reduced separation-related behaviours and general anxiety scores (Vaterlaws-Whiteside & Hartmann Reference Vaterlaws-Whiteside and Hartmann2017). Further, Vaterlaws-Whiteside and Hartmann (Reference Vaterlaws-Whiteside and Hartmann2017) suggest that puppies who had participated in additional socialisation experiences compared to puppies who had not, had more desirable behavioural responses when exposed to various types of stimuli, including unfamiliar people and objects. However, further research is needed to assess the impact of socialisation classes for kittens and elucidate the aspects of these programmes which carry the most benefit for the cat and the owner.

Aside from veterinary guidelines and best practice statements on kitten and puppy socialisation, to the authors’ knowledge, no other socialisation guidelines exist for non-veterinarians such as shelter staff or pet store staff. However, many shelter facilities may have staff with a special interest in behaviour and socialisation. For example, some shelter facilities have staff members who run socialisation classes or specialise in socialising fractious kittens and/or shy adult cats. These individuals may have access to reputable resources and may play a key role in educating other staff members and the public (i.e. new kitten adopters) on socialisation topics. Many animal shelter organisations collaborate with local pet stores and may house kitten/adult cats at pet stores to help increase adoption. Our survey did not differentiate between pet stores who collaborate with local shelters for increasing kitten/cat adoption and those that do not, which may be important for understanding how much socialisation information new kitten owners are provided. For example, some pet stores partner with local shelters to increase pet adoptions, providing information to new cat owners via their website which has a section dedicated to education on topics relevant to these individuals (i.e. tips on cat furniture, feeding, and helping a new cat adjust to its new home; Petco undated). Further research should assess how this information correlates with current recommendations. In addition, future work should attempt to compile socialisation information disseminated to new cat owners at adoption/purchase to better understand the information exchanged and how this aligns with current veterinary and behaviour expert socialisation recommendations.

Socialisation is often referred to as a life-long process (Hetts et al. Reference Hetts, Heinke and Estep2004; AVMA 2015, 2024; Petak Reference Petak and Petak2022), although little research has assessed the impact of continued socialisation on cat behaviour and health outcomes. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to ask cat owners their opinions on adult cat socialisation practices and programmes. Most participants indicated they were not interested in attending adult cat socialisation classes, with many reporting concern regarding health issues and indicating that travel would be stressful for their cat. Online socialisation classes aimed primarily at owner education may be a suitable alternative for owners who are particularly concerned with stress caused by travel. Caution should be noted for adult cat socialisation classes involving exposure to new environments and unfamiliar people, both of which have been associated with negative responses in adult cats (Carlstead et al. Reference Carlstead, Brown and Strawn1993; Slater et al. Reference Slater, Garrison, Miller, Weiss, Makolinski and Drain2013). Thus, it may be beneficial to structure adult cat versus kitten socialisation programmes differently. For example, virtual programmes may be more reasonable for adult cats, as well as focusing more on owner education and improving the human-cat bond. Whereas either virtual or in-person programmes may be effective for kittens, with a focus on exposure to novel stimuli (e.g. new animals, people, environments) as well as owner education. Research is needed to assess the most effective way to implement adult cat versus kitten socialisation programmes, as well as components of these programmes that would be beneficial for each life-stage. Further research is also needed to produce effective, evidence-based protocols for various components of a socialisation programme, such as handling cats for nail trims.

Study limitations

Some of the study questions relied upon participants remembering socialisation information provided to them during their cat’s adoption/purchase, and during their cat’s initial veterinary examination post-adoption. This information is vulnerable to recall bias as participants may only remember some or none of this information, rather than what they were told in entirety. In addition, most of our survey participants were women, those living in suburban environments, and those without children, which is not representative of all cat owners. However, a large percentage of woman respondents is common in online surveys (Sax et al. Reference Sax, Gilmartin and Bryant2003). This represents a clear limitation, although it is not unique to our survey nor to cat survey research. In addition, other cat survey research similarly shows a large percentage of respondents indicating not living with children (Grigg & Kogan Reference Grigg and Kogan2019; Khoddami et al. Reference Khoddami, Kiser and Moody2023). This may be due to this population of cat owners who have the time, or greater inclination, to complete questionnaires related to their cat(s). In addition, it is possible this questionnaire attracted a specific population of cat owners with particular interest in socialisation, and thus the data presented may not be representative all cat owners in general.

Animal welfare implications

Kitten and cat socialisation programmes aim to increase owner education and promote practices for optimising cat health, welfare, behavioural management, and a strong human-cat bond. The current study provides information on aspects of kitten and adult cat socialisation deemed important by cat owners, elucidates reasons cat owners would or would not want to enroll in kitten and adult cat socialisation programmes, and highlights areas for future work. It is important to note that travel and exposure to new environments, people, and animals are inherent to kitten socialisation classes, and may result in excess fear and stress for some kittens and adult cats. Thus, the mode of the socialisation programme (i.e. in-person, virtual) should be considered and selected on an individualised basis to promote animal welfare.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/awf.2025.10013.

Competing interest

None.