Introduction

Since the global financial crisis, governments across the western world have advanced a strategy of fiscal austerity to curtail public spending and investment across a diverse range of social, economic and political areas with highly uneven effects (Tyler, Reference Tyler2015). Austerity has brought a renewed fascination by governments with fast policy transfer, and disability is one place where this has actively occurred, becoming ‘a key economic policy area in most OECD countries’ (OECD, 2009: 1). Peck and Theodore (Reference Peck and Theodore2015) intimate that global policy trends and their enactment within local spaces and places entail an extensive process of political negotiation, navigating institutional histories and materialities; it is not a simple notion of interscale transfer between nation-states. Austerity has achieved global political traction yet its embedding at the local scale connotes a multiplicity of unique local processes, practices and outcomes (McCann, Reference McCann2008). States are actively learning from each other, mobilising a diverse set of policies, ideas and processes, to achieve the immanent aims of lower social spending (Grover and Soldatic, Reference Grover and Soldatic2013). While there is movement, there is also mutation when it lands.

This article adopts a methodological approach that emplaces Indigeneity within the space of disability social security law and policy, enabling a richer relational analysis of the global mobilities of austerity policy and the differentiated forms of disability–Indigenous embodiment that are brought to the fore under nascent processes of state classification. To begin this process, the article first works through Australian disability social security reform with a focus on income support payments. The following section provides an overview of disability within Indigenous Australia, examining the reproduction of Indigenous–disability inequality in regional areas. The final section of the article engages with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and their embodied experiences of disability social security retraction when residing in, on the fringes of or close to, regional locales. By drawing on interviews, documentary sources and parliamentary records, the article reveals the nuances in the social reproduction of Indigenous–disability structural inequality (Walters, Reference Walters2016). This analysis reaffirms Peck and Theodore's (Reference Peck and Theodore2015) arguments that, given the global mobility of neoliberal welfare retraction and its renewed intensity with austerity, we need to follow the global mobility of austerity policy, opening the analysis to capture its everyday impacts as it lands on the ground and the bodies-and-minds that are subject to its power.

Moving the policy boundaries: disability income reform in Australia

The Government does not view welfare reform as a cost cutting exercise; rather, as a structural change designed to reduce welfare dependency through greater economic and social participation. Full implementation of reform will require substantial upfront investment of budget funds. Unless we make this investment, significant sections of the population may be excluded from the benefits of social and economic participation. (Australian Government, 2000: 4)

Australia has instigated a highly contradictory path of disability reform. In real fiscal terms, Australia's investment in disability social provisioning is now greater than at any time since the emergence of national disability welfare structures. Since early 2013 successive Australian governments, with bipartisan support, have committed to a new individualised funding program, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). The scheme, centrally funded via general taxation revenue, is expected to cost more than A$22 billion by 2020 and is expected to stabilise at 1.3 per cent of GDP by 2045 (Porter, Reference Porter2017). The program will be directed towards more than 460,000 Australians with disabilities (Porter, Reference Porter2017). For the first time, disability social provisioning will recognise the unique relationship between the private lives and public participation of people with disabilities, through tailored personalised supports via individualised budget mechanisms.

Such national budgetary investment in response to the Australian disability movement's demands for personalised measures, that is, funding that disabled people can control and direct, is a critical component in the Australian Government meeting its responsibilities to disabled citizens in the years to come (Productivity Commission, 2011). Australia has been applauded for its efforts for the scheme as it reorients its national disability social service funding, policy and programming in line with its obligations as a ratifying state party of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)Footnote 1 (see Van Toorn and Soldatic, Reference van Toorn and Soldatic2015). There remains, however, a core tension within Australian disability social provisioning, this nascent national rhetoric of disability rights realisation and the redistributive system of cash transfers for its disabled citizens. A quiet revolution has taken place in the government's pursuit of retracting social spending in different parts of the disability system. Over a period of almost twenty years, there has been an advanced effort to redefine certain segments of the disability population so that they are no longer deemed as ‘disabled’; hereto, no longer eligible for disability social provisioning. This process of recategorisation has been focused on the disability social security system and the primary disability income payment for workless disabled people, the Disability Support Pension (DSP).

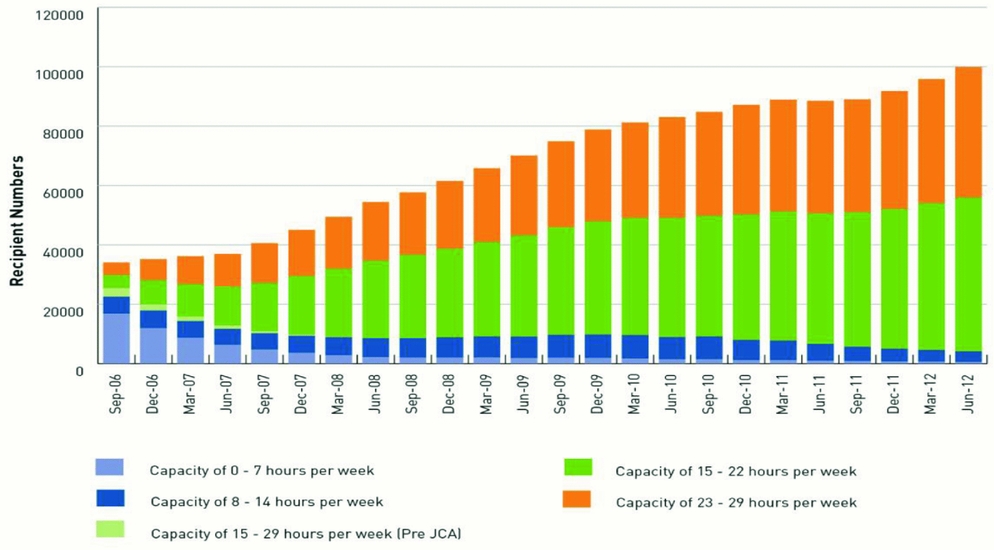

International analysis suggests that austerity policies converge around the restructuring of disability social security entitlements with the primary aim of steering disabled people off disability pensions and income support payments and into the open labour market. Australia has been both leader and follower in these global trends (see Grover and Soldatic, Reference Grover and Soldatic2013). Indeed, since the late 1990s a plethora of strategies has been mooted to reduce the number of people accessing the DSP (Galvin, Reference Galvin2004; Soldatic and Pini, Reference Soldatic and Pini2009, Reference Soldatic and Pini2012). Coupled with an affective political discourse of statistical panic, the infamous ‘welfare fraudster’ (Vanstone, Reference Vanstone2002) has become responsible for a national fiscal crisis because of growing welfare payment outlays (Soldatic and Meekosha, Reference Soldatic, Meekosha, Watson, Thomas and Roulstone2012). The early 2000s, under a Liberal–National Coalition government, saw earnest policy movement to create new boundaries around the disability category and curtail social spending (Soldatic, Reference Soldatic2010). Legislative efforts were marshalled, with projected savings of millions of dollars consistently cited as vital to sustaining a ‘fair and just’ system for the truly disabled (Bills Digest No. 157, 2001: p. 11). Cutting the disability temporal work test from thirty hours per week to fifteen hours per week (wherein those who are deemed capable of working fifteen hours a week are no longer eligible for the DSP) was the most publicly contentious aspect of the proposed reforms, as the proposals were aimed at both future claimants and existing recipients. As Figure 1 outlines, the slashing of the temporal work test fully realised the government's strategic intent, that is, recategorisation of a core group of disabled people as the general unemployed with no further entitlements to disability state social provisioning, leading to growing numbers of ‘partially disabled people’ filling the general unemployment rolls.

Figure 1. Newstart Allowance recipients with partial capacity to work (in other words, disability) since implementation of 2005 changes

The Labor government elected in 2007 advanced further reforms by undertaking a comprehensive review of the DSP medical impairment test, to ascertain disabled people's degree of disability, and implementing mutual obligation requirements and activity tests – participation plans – for those people on the DSP aged under thirty-five years (Macklin, Reference Macklin2011). While Labor was the architect of the new NDIS, encompassing access for over 460,000 Australians with disability, its continual containment of the DSP has denied many people with disabilities the right to social protection. The 2011 legislative tightening of the DSP eligibility criteria has seen a drop from 827,260 recipients in June 2012 (DSS, 2013) to 814,391 in June 2015 (DSS, 2015).

Despite the declining numbers of people on the DSP, a core component of the 2016 national budget was a deliberate strategy to redetermine DSP eligibility for existing recipients (up to 90,000 people). Moreover, a range of smaller but necessary disability benefits for DSP recipients are being tightened, removed or moved to the NDIS, removing broad-scale access by 2020 (Porter, Reference Porter2017). The justification for DSP retraction is now deeply attached to the projected fiscal allocations necessary to maintain the viability of the NDIS; in other words, to realise the full potential of the NDIS we must retract, contain and limit access to the DSP. How austerity has played out in Australia confirms Peck's (Reference Peck2011) argument that austerity is a renewed stage of global neoliberal re-regulation of the poor and the precariat, propelling them into the low end of unskilled, casualised labour markets. Or, as UK disability activist Disability Bitch (2010) has suggested, global austerity means that disabled people are ‘all going to have to mud wrestle to prove who is most disabled and therefore most deserving, and throw the losers into the gutter’.

In Australia, the austerity gutter is increasingly filled with people with disabilities who no longer qualify for the DSP and have been placed on the general unemployment benefit – Newstart Allowance (NSA). Once switched to Newstart, many people with disabilities will no longer qualify for additional disability assistance, such as mobility subsidies, education supplements or specialist mobility aids and equipment (Porter, Reference Porter2017). Table 1 highlights the differences between the NSA and the DSP. The Australian Council of Social Service has identified that relying on Newstart results in extreme poverty, with 55 per cent of NSA recipients living below the poverty line (ACOSS, 2016). Disability poverty is an extremely complex phenomenon; it combines the effects of income deprivation, inadequacy of service systems and supports, employment exploitation and discrimination, and, finally, inaccessible environments and infrastructure, such as public transport systems, inaccessible streetscapes, buildings and environments, with the consequence that disabled people are effectively locked in their homes (Alcock, Reference Alcock1993). Missing appointments and non-attendance at prescribed work activities results in the deduction of payments, even when such misdemeanours are associated with one's disability (Marston et al., Reference Marston, Cowling and Bielefeld2016). The moralising and stigmatising to which people with disabilities are subjected has real impacts on their health and wellbeing, diminishing their bodily capacities and sense of self-worth while denying dignity and respect. This may lead to the development of secondary impairments as people cannot afford basic medical care, decent housing and, in some instances, basic food items to maintain daily nutrition (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Wilson, Soldatic, Grover and Piggott2015; Spurway and Soldatic, Reference Spurway and Soldatic2015). Disability is henceforth ill considered within the general unemployment social security system, even though this is where disabled people are increasingly forced to go.

Table 1 Welfare streams for people with disabilities according to assessed work capacity

*There have been two attempts at legislative change to end the DSP education supplement (Social Services Legislation Amendment (Omnibus Savings and Child Care Reform) Bill 2017) and move the mobility allowance to the NDIS by 2020 (Social Services Legislation Amendment (Transition Mobility Allowance to the National Disability Insurance Scheme) Bill 2016).

Source: Adapted from Morris et al. (Reference Morris, Wilson, Soldatic, Grover and Piggott2015) and updated from Department of Human Services (2017a, b, c, d, e) to reflect the rules and payment rates at the time of writing (17 February 2017).

The assemblage of such contradictory measures raises numerous questions, not least the unreasonable economic insecurity generated for people whose disability no longer qualifies them for ‘disability’ status. What enables states to retract disability rights in one part of the system while expanding another section to the benefit of the few? A core right under the CRPD is the right to an adequate standard of living and social protection, with disability income measures explicitly mentioned as a state responsibility (Article 28). Roulstone and Morgan (Reference Roulstone, Morgan, Soldatic, Morgan and Roulstone2014: 67) further argue that austerity's stigmatised welfare economy impacts the right to personal mobility, articulated in Article 20 of the CRPD. New forms of disability demobilisation are generated as people with disabilities no longer navigate the urban streetscape at the risk of being seen as a ‘faux disabled person’ and enduring the psycho-social disablism that ensues. The moral corporeal economies generated through stigmatised disability income support payments impose new forms of personal containment on people with disabilities, containing oneself within oneself, in hope of containing the pain of new harms and socially generated distress.

Intertwined with the broad social, economic and cultural rights of the CRPD are the articles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Persons (UNDRIP)Footnote 2 and the International Labour Organization's Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (No. 169)Footnote 3 , which also support the right to adequate economic and social conditions. Articles 21 and 22 of the UNDRIP proclaim that particular attention be paid to ‘the rights and special needs of . . . persons with disabilities’ as well as Indigenous elders, women, youth and children. While this is an attempt to address intersectionality within international law, Australia's reluctance to enact the UNDRIP or support the ILO convention demonstrates the unique discriminatory processes, impacts and outcomes of its disability and Indigenous policy at the local scale.

Indigenous disability inequality in Australia

As Walter and Saggers (Reference Walter, Saggers, Carson, Dunbar, Chenall and Bailie2007) point out, the experience of absolute inequality is most prominent for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Across all indicators of social exclusion, deprivation and poverty, they are by far the most disadvantaged group in Australia (Australian Government, 2017). Inequality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians entails more than economic exclusion, encompassing broader indicators associated with familial connection, community participation and cultural wellbeing (Walters, Reference Walters2016). Understanding the impact of welfare retraction needs to capture these issues, beyond mere indicators of economic exclusion, engagement and productivity. As Walters (Reference Walters2016: 68) argues, it needs to encompass the gamut of structures, policies and activities that ‘create and reproduce Indigenous inequality’.

National population data suggests that almost 18.3 per cent of the Australian population has a disability, or approximately 2.1 million people (ABS, 2015). The labour-market participation of disabled people of workforce age currently stands at only 53.4 per cent, which is 30 per cent lower than for the general Australian population (ABS, 2015). The rate of disability for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians was 23.4 per cent in 2012 (ABS, 2012). For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians living with disability, participation within the labour-market was as low as 34.8 per cent, the widest participation gap in Australia (ABS, 2015). These national statistics point to the significance of disability social provisioning measures for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Despite the significantly higher rates of unemployment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians with disabilities, ‘reliance on government pensions and allowances as the principal source of income is similar to that for all Australians with a similar age and severity of disability’ (AIHW, 2011: 2). Colonial structures of power simultaneously generate high rates of impairments while perpetuating new forms of lateral violence, intensifying the production of impairment for Indigenous Australians (Gilroy and Donelly, Reference Gilroy, Donelly, Grech and Soldatic2017). As Hollinsworth (Reference Hollinsworth2013) argues, this enduring historical context means that the claiming of disability for Indigenous Australians living with disability intensifies their daily experiences of racism. They are, therefore, confronted with the very real dilemma of claiming disability to access the necessary entitlements and supports with the effect of increasing their exposure to unique forms of institutional stigmatisation and discrimination, or, living in extreme forms of poverty with inadequate and poor-quality services, ill equipped to support their disability needs (Hollinsworth, Reference Hollinsworth2013).

It is well documented that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have experienced some of the harshest effects of neoliberal intensification with austerity and its continuous pursuit of state welfare retraction (Bielefeld, Reference Bielefeld and Sanders2016; Marston et al., Reference Marston, Cowling and Bielefeld2016). Given the highly racialised nature of these measures, practitioners, activists and researchers concerned with the advancing of neoliberal principles in Australia have been mostly interested in Indigenous social policy. In the meantime, other fields of social provisioning that have become increasingly important to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander wellbeing have received little critical attention (Soldatic, Reference Soldatic, Howard-Wagner, Bargh and Altimarino-Jimenez2017). Yet, outside a few studies focusing on local models of Indigenous–disability care and support (Gilroy and Emerson, Reference Gilroy and Emerson2016; Gilroy et al., Reference Gilroy, Dew, Lincoln and Hines2016), there is almost no research examining changing disability income regimes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. As the data suggests, fewer Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians are the beneficiaries of disability income regimes.

Considerations of regional towns and centres are particularly critical in identifying the uneven and differentiated impacts of austerity (Milbourne, Reference Milbourne2010). Regional centres are often hubs of economic, social and cultural activities, alongside housing vital government institutions for citizens’ wellbeing, including hospital and health centres, welfare and social services, and educational centres (Tonts, Reference Tonts2004). In the Australian context, regional towns have permanent populations alongside transitory populations of rural visitors who regularly move in and out of the town for activities of a transactional nature, particularly around accessing necessary government institutions, banking and finance facilities, and cultural activities and festivities. Regional towns and centres are therefore not only important for their permanent residents, but also for those people who reside in outer rural farms and communities that heavily rely upon regional towns and centres to sustain their livelihoods.

In Australia, income support systems, including the DSP, have helped maintain regional centres in times of economic uncertainty, as has been well recognised in national income support legislation and policy for non-Indigenous Australians (Beer, Reference Beer2012: 274). The DSP, for those disabled people eligible, also entitles those who are residents of regional towns and centres to a range of localised subsidies, including household water consumption and energy use, vital resources in sustaining daily practices of self-care. DSP reform, while it may appear particular, insignificant and limited in its reach, has broader ramifications for local regional economies, as it contributes to sustaining community social cohesion and cultural wellbeing through enabling localised practices of support, inclusion and diverse economic activity. This work all suggests that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians with disabilities are uniquely affected by national disability income retraction.

Methodology

Balakrishnan and colleagues (Reference Balakrishnan, Heintz and Elson2016) suggest that the methodological significance of locating the normative assessment of economic policy and its impact on differing groups is rich intersectional analysis, capturing social, economic and cultural rights as they are embodied in everyday practices. Yet, while intersectionality has become a core framework through which economic and welfare retraction is analysed, a central concern is that intersectional analysis may in fact hide state classificatory regimes emerging with austerity and the socio-legal prioritisation of particular groups within the administrative apparatus. Tyler (Reference Tyler2015) confirms these arguments, stating that neoliberal state welfare retraction has resulted in a set of technologies of governance that intensify classificatory struggles, generating nascent structures of inequality, poverty and structural violence. Gaining access to state welfare supports increasingly requires a manoeuvring of one's body-and-mind in tightly regulated processes of legislated eligibility; individuals are faced with being forced to foreground a particular identity to advance redistributive claims upon the state, even though such identities may be marginal to their subjectivity. Edwards (Reference Edwards, Soldatic, Morgan and Roulstone2014: 32) strongly argues that these socio-legal administrative processes ‘form a site of inscription of particular values and creation of identities, and inescapably shapes how we experience our lives, including how we interact with different spaces’. To understand the embodied experience of these regimes, adopting a methodological approach that emplaces one's primary identity within another state classificatory logic may yield richer nuance in the analysis.

The injustice of state classificatory logic resonates strongly with Indigenous struggles for rights, justice and sovereignty. Shifting official classificatory regimes of ‘persons’ under Australian socio-legal regimes has been a core component of Australia's colonial history since European invasion in 1788. At the formation of the nation in 1901, the Australian Constitution denied Australia's First Peoples any form of recognition as a class of people, explicitly excluding them via the doctrine of terra nullius (Soldatic, Reference Soldatic2015). The 1967 national referendum removed section 51 from the Constitution, which had effectively excluded Indigenous Australians from national population census information. Indigenous Australians received ‘the right’ to be included within the national polity and, for the first time, to be counted as valid persons of the Australian state (Korff, Reference Korff2017). Yet, to this day, there is no formal recognition of Australia's First Peoples within the constitution, and Indigenous struggles for recognition continue to this day. Across the nation, Indigenous groups have mobilised for both constitutional recognition as the First Peoples and for a national treaty to advance and secure socio-legal structures and institutions of sovereignty, rights and self-determination (First Nations National Constitutional Convention, 2017).

Given this history of colonisation and Indigenous dispossession, this project foregrounded Indigenous research methodologies to examine the impacts of disability income payment retraction on the daily lives and family and kinship networks of the participants. Working with a local Indigenous disability worker from a small regional Aboriginal Land Council in the South Coast corridor of New South Wales, Australia the research was conducted across a period of almost four months. The practice of Indigenous ‘yarn ups’ was the primary method adopted. This involves working with either established locally based Indigenous meeting groups, such as Indigenous women's groups, or creating an opportunity for people to come together to ‘yarn’ in depth on a particular theme. This research project adopted both practices. A large women's circle active in the area invited the researcher to attend their discussion circles. This was in addition to a number of smaller discussion groups, specifically established for the research. In all, approximately twenty-four people participated in the research, comprising nineteen women and five men, which was not surprising given that one of the groups was a women's Indigenous health ‘yarn up’ group. Each of the research discussion groups directly involved Indigenous persons living with disability and, at times, their family members, kin and Indigenous disability support worker. Participants had had a diverse range of experiences with the disability income regime. Therefore, they are fairly representative of the lived experience of disability pension income reform including longstanding recipients of the DSP who had been moved onto Newstart Allowance and had to prove on a regular basis, via medical certificates and doctors’ reports, that their disability was severe enough to exempt them from work activity testing for a period of time (anything from two weeks up to three months); and those who had been shifted as new DSP claimants straight onto Newstart with no disability exemptions and were required to participate in a range of welfare-to-work activity tests (job interviews, fortnightly compliance reporting, etc.) to maintain access to this basic payment, and finally, those who had received a DSP prior to the first round of legislative changes in 2005 and therefore, remained untouched by the last ten years of disability pension austerity retraction.

Indigenous–disability circular mobilities of poverty management

The issue we have is that we are at the end of the train line, so after us there is really nowhere to go. We have one person who was living in the bush, but has now moved closer into town as they need to go to the hospital. (Local regional officer, 2017)

While the global intent of austerity has been to force bodies to move house and home to take up jobs in low-paid, precarious labour markets in urban centres, as Imrie (Reference Imrie, Soldatic, Morgan and Roulstone2014) has illustrated, it often keeps the poor, the precariat and the disabled locked in place. From a disability standpoint, scholars such as Reeve (Reference Reeve, Soldatic, Morgan and Roulstone2014) have documented well the ways in which disabled people, confronted with a retracted disability income support system, remain locked behind their doors, sitting in quiet anxiety, awaiting the arrival of departmental letters for eligibility reassessment, and, once completed, waiting further for the arrival of the envelope announcing their removal from the disability welfare rolls. Many disabled bodies-and-minds are on the move; however, these are disabled people who are no longer categorised in public policy as being really disabled. Mobility for this class of disabled people is perhaps most accurately described as internal migratory flows: disabled people who no longer qualify for a disability income payment who are moving to accessible and affordable regional landscapes. The ‘end of the train line’, in the opening quote with a local regional officer, affords places of hiding, where one can hide from the remoralising public gaze that defines people with disabilities as potential welfare fraudsters. This phenomenon of moving to rural and regional landscapes appears to be a growing feature of global disability income retraction.

This emergent research on disability austerity differs significantly from the previous accounts of disability mobilities which have mapped out issues of inaccessibility and exclusion through urban design and physical space, alongside the lack, or inadequacy, of mobility aids and equipment (Imrie, Reference Imrie, Soldatic, Morgan and Roulstone2014). Grech's (Reference Grech2015) research with Indigenous people with disabilities residing in rural and remote villages in Guatemala illustrates the extreme forms of immobility generated by the unique interstice of racism, disablism and non-urban landscapes in settler states. Grech (Reference Grech2015) argues that income poverty compounds the exclusion of Indigenous people with disabilities as they cannot afford to be mobile, despite needing critical assistance, medical intervention and disability aids and equipment. Australian scholars Grant and colleagues (Reference Grant, Zillante, Tually, Chong, Srivastava, Lester, Beilby and Beer2016) have noted the significance of mobility aids and equipment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians living with disability in rural and remote Australia, capturing the particular ways in which personal mobility aids and equipment are intimately tied to the making of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural identity through enabling their enduring involvement in cultural practices and ceremony, alongside taking up communal responsibilities. Mobility and physical movement for Indigenous people with disabilities is thus multifaceted; personal mobility is critical for the realisation of disabled people's individual autonomy, self-expression and care of the self (see Imrie, Reference Imrie, Soldatic, Morgan and Roulstone2014), and this is intimately intertwined with the individual's social expression of cultural integrity, participation and belonging (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Zillante, Tually, Chong, Srivastava, Lester, Beilby and Beer2016).

Issues of mobility with the onset of disability income retraction are qualitatively different for Aboriginal people with disabilities residing in regional towns than for non-Indigenous disabled people in the same areas, as suggested by the Aboriginal research participants of this study. The research participants had strong connections to family, kin and community and therefore strong cultural and spiritual attachments to place. They did not desire to leave their local communities and their entire support network, which they relied on for daily disability support, including travel to health-care appointments, primarily because this is what enabled them to be part of their Aboriginal culture, family and community.

Participants who were new claimants of the DSP and had been shifted onto Newstart with no disability exemptions discussed the consistent level of ‘breaching’, that is, being removed from Newstart because of non-compliance, and their consequent heavy reliance on family, kin and community to step in and fill the economic gap. The stopping of payments was often due to a confluence of factors: being unable to afford transport or unable to access transport in a small regional town; and difficulty reading and interpreting forms because of the nature of their impairment, in this case dyslexia, all often resulting in appointments with the welfare authorities being missed. As Peter, a young Aboriginal man residing in a small town on the South Coast, explained:

I have been breached quite a lot. Because I have dyslexia I find the forms and letters really hard. I ask [his partner] to help me, but all it does is just increase her anxiety and depression. I just can't get to all of those appointments all the time. I don't have any money and I don't have a car.

Required attendance at regular appointments to sustain the Newstart payment was not only confined to those people with disabilities such as Peter's, considered by the welfare agency to be in the mild category and therefore to have little impact on his work opportunities within the work criteria. The interview participants with severe impairments were also expected to be constantly on the move. Their mobility was highly regulated by the requirements attached to their payments, involving attendance at a raft of appointments and interviews, to show that they were somewhat disabled and therefore exempt from a range of welfare-to-work conditionality, such as those activities Peter was required to perform to maintain ongoing access. Travelling consisted of constant movement between home, medical appointments for part-disability certification, welfare offices, and back home again, in a never-ending cyclical motion. Movement was primarily focused on presenting in a plethora of spaces in order to have their not-so disabled status certified. Due to its constant repetition, this movement mobilised one's body-and-mind in a circular motion. Margaret, an Aboriginal woman with severe anxiety and depression, interviewed in March 2017 at a community in a small coastal town of the eastern seaboard of Australia, described this constant, repetitive cyclical movement she was required to perform to maintain her part-disability status and be relieved from welfare-to-work conditionality as a Newstart recipient:

I don't qualify for DSP. I am on Newstart Allowance. I don't have to apply for jobs all the time. But I have to go to the doctor's every three months to get a new assessment to say that I can't work. I need this certificate from the doctor otherwise [. . .] will cut me off from my payments. Once I get the certificate from the doctor, I then have to take this down to the . . . office so that they leave me on Newstart Allowance. I just can't do that. It's too stressful for me and just makes me more depressed and anxious.

This cycling from home to the medical surgery and the welfare office varied in frequency. Throughout the interviews, the research participants described the system as ‘arbitrary’ and ‘random’ in its administration, requiring some people to report every two weeks and others every three months. Charlie, a man in his fifties with early onset dementia and unable to read and write in English, was another Aboriginal person living with disability who did not qualify for the DSP and was placed upon the lower and more stringent general unemployment payment. Charlie's medical certification requirements were much more onerous. He was required to report to the doctor's office fortnightly to receive a new medical assessment along with medical certification to then take to the welfare office so that he would be exempt from the welfare-to-work conditionality of Newstart. His sister, Doreen, explained the impact on his personal wellbeing and the wellbeing of his family and community in managing this status of not being ‘disabled enough’:

So, I'm trying to . . . this . . . so the doctor didn't agree that he needed a DSP, but she wanted to see him every fortnight to get the forms signed off to take to Centrelink. . . . No it took like months and months. And the people just give up. You know, you know, you're going in and out of Centrelink.

Aboriginal people living with disability are thus mobile, but it is a circular mobility driven by the need to manage their payments as disabled people who are not considered ‘disabled enough’ or are living with a condition that fluctuates between short moments of wellness and more sustained moments of unwellness. This constant cyclical movement to verify part disability often generated high levels of stress and anxiety for the research participants, as the consequences of being cut off from any form of income payment would mean they had no money, resulting in extreme poverty. They would therefore have to rely on family and other community members who were often living in severe poverty themselves. Rebecca stated, from her experience supporting her sister, that this continual cyclical movement between numerous medical and welfare appointments only created suffering for the individual with a disability and their family, who were trying to get them onto the DSP so they no longer had to work hard at proving how disabled they were:

And you've got to jump through so many hoops to achieve what you need. That's the worst of it. People are suffering between these back and forward meetings they call all the time. And it's just . . . it's too long for people to wait.

As Rebecca outlines in relation to her experience in supporting her sister trying to access the DSP, mobility involved cycling their bodies-and-minds through a strict disability income regime so that they could maintain some level of economic security as a disabled person who no longer met the criteria for disability income support payments. This form of personal mobility relies heavily on the support of family, kin and community to meet the demands of welfare conditionality attached to non-disability income support payments (Newstart). While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with disability are on the move, disability austerity has resulted in a new form of Indigenous containment, fixing them in a cyclical motion of poverty management.

Concluding discussion: practices of mobility for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disabilities

Encountering practices of Indigenous mobility is filled with racialised tension and anxiety, particularly within the settler imaginary. In Australia, narratives of Aboriginal mobility are deeply enmeshed with the expansion of the colonial settler state. Colonial settlement, as Peterson (Reference Peterson, Taylor and Bell2004) and Prout (Reference Prout2009) have illustrated, was tied to the settler's illusion of the ‘wandering nomad’ ‘going on walkabout’, a people without economy, society or culture. This depiction of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mobility became a powerful legitimising discourse for the settlers’ expansion onto their lands, nations and territories, as settler narratives depended on a fixed, and often contradictory, idea of Aboriginal spatialities, while legitimising the forced containment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in missions, stations and camps (Prout, Reference Prout2009). The historical tendencies of white colonial settlement have thus created a barrage of difficulties in teasing out Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander narratives of mobilities, as the tensions of settler mythology, power and violence have short-circuited the rich complexity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges and practices of movement.

Personal mobility, as articulated in Article 20 of the CRPD, is qualitatively different for Indigenous people with disabilities. Mobility is ‘fundamental to an Aboriginal individual's social identity’ (Peterson, Reference Peterson, Taylor and Bell2004: 224). Indigenous mobility is ‘influenced by a mix of considerations that reflect the persistence of the customary alongside change’ (Taylor and Bell, Reference Taylor, Bell, Taylor and Bell2004: 17). Continuity in Indigenous customary mobility is often a circulatory practice of movement of sustaining cultural rituals and practices of ceremony embedded in thick social relations of kin and country. There is movement and also return to home (Smith, Reference Smith, Taylor and Bell2004: 241). Indigenous customary mobility is associated with the use and management of land, and broader intercultural relations of economies of exchange. For example, Hill and colleagues (Reference Hill, Grant, George, Robinson, Jackson and Abel2012) document Indigenous practices of mobility surrounding local ecological management through a web of knowledge networks and ecologies, which both sustains and transforms local Indigenous languages and customary practices.

Indigenous circulatory mobility is interconnected with sustaining and renewing Indigenous social identity, including the multiplicity of ‘multi-locale relationships’ across a range of landscapes (Taylor and Bell, Reference Taylor, Bell, Taylor and Bell2004: 17). Personal mobility for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians living with disability, particularly in regional centres and rural towns, is intimately tied to the self-expression of one's cultural identity, the production of Indigenous economies and the maintenance of a set of relational connections and ties (Smith, Reference Smith, Taylor and Bell2004). Yet, as shown by this study, cyclical mobility takes on new meaning for Aboriginal Australians living with disability; cyclical mobility is compelled for economic security and is linked to the identity of disability, rather than being mobile to undertake cultural and social responsibilities. In fact, cyclical mobility through spaces and places was critical to assure continued access to income support payments, moving from home to a range of medical and welfare offices to sustain access to the system.

As Prout (Reference Prout2009) and Habibis (Reference Habibis2013) suggest, given the settler's historical narrative, Australian policy narratives of Indigenous mobility have shown limited understanding of Indigenous movement, the flow of Indigenous bodies-and-minds across borders and boundaries, and the temporal rhythms and cycles of Indigenous lifeworlds. The settler desire to be ‘settled in place’ has instilled a national policy narrative that seeks to continually make explicit policy boundaries and borders, though rarely explores the edges of movement, mobility and transition. Too often, the policy has been one of containment: containing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within the outstation, the mission and the town camp. Disability income retraction is driving new forms of Indigenous mobility, one that is circular, yet cycles Indigenous persons living with disability through a range of highly specialised medical and welfare services to validate their status as a ‘semi’ disabled person par excellence of state classificatory power. This mobility, to sustain some basic level of economic insecurity, effectively negates the critical role of Indigenous mobility for the ongoing expression of Indigenous identity, self-determination and sovereignty. Thus, through emplacing the lived experience of disability for Indigenous persons within disability state classificatory regimes, this research begins to distil the significant impacts of state retraction in relation to those rights enshrined within the CRPD and, more significantly, for Indigenous Australians living with disability, the body of rights enshrined in the UNDRIP and ILO Convention 169. Most significantly, the methodological approach provides the opportunity to examine the significance of non-Indigenous specific social and economic rights, such as disability rights, and the role that these rights play in realising Indigenous claims for justice, rights and sovereignty under the white settler state of Australia.

Acknowledgements

The research reported on in this article has been funded by an Australian Research Council DECRA Fellowship (DE160100478). Thank you to Kelly Somers for copyediting the article.