BACKGROUND

By mapping movements of the eye in various clinical settings, eye tracking can be used as a tool to characterize the visual fixation of healthcare providers.Reference Blondon, Wipfli and Lovis1, Reference Goldberg and Kotval2 Characterization of visual fixation in various clinical environments helps build on our understanding of behaviours that promote best practices.Reference Blondon, Wipfli and Lovis1 Although eye tracking has been used in various clinical settings, it has not been applied to pediatric trauma resuscitation. In this study, we used simulation as a tool to study eye tracking behaviours in pediatric trauma resuscitation.

Each year, thousands of children are hospitalized due to trauma-related incidents.Reference Pike, Khalil and Yanchar3 The burden of pediatric trauma can be lessened with effective and efficient emergency care.Reference Pike, Khalil and Yanchar3 Effective management requires multiple healthcare providers working together with a shared understanding of goals for patient care. To achieve this, situational awareness is key.Reference Endsley4 Situational awareness is the ability of an individual to process information about her or his environment.Reference Endsley4 This concept consists of three levels: Level 1 – acquisition of relevant information; Level 2 – integration of information leading to understanding; and Level 3 – prediction of future states.Reference Endsley4 Eye-tracking technology permits the collection of data regarding Level 1 of situational awareness via a video analysis. Eye-tracking data collected during pediatric trauma may build our understanding of situational awareness amongst trauma team members, which can be used to guide the development of future educational interventions.Reference Endsley4–Reference Henneman, Marquard, Fisher and Gawlinski6

PURPOSE

We sought to determine the feasibility of using eye tracking in pediatric trauma simulation and to characterize the eye-tracking behaviours amongst physicians during the management of a simulated pediatric trauma patient. We hypothesized that eye-tracking technology is feasible and visual fixation would be focused on the patient.

DESCRIPTION OF INNOVATION

Methods

This study was an observational, non-blinded, simulation-based study. Research ethics board approval was obtained from The University of Calgary Behavioural Research Ethics Board. Nine pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) physicians (years in practice: 1 to 15 years) were recruited to participate as a trauma team leader (TTL) in a simulated pediatric trauma scenario (blunt trauma with hypovolemic shock) with nurses, respiratory therapists, paramedics, and a bedside doctor filling out the roles of the other trauma team members. TTLs were fitted with a head-mounted Mobile Eye XGTM eye-tracking device. All sessions were video recorded through the eye camera and scene camera. As means of standardization, the first 5 minutesReference White, Braund and Howes7 of each session were manually analysed by watching the video using Noldus Observe XTTM software. A coding matrix was used to identify and mark areas of interest (AOIs), or instances where the visual gaze remained fixated on a specific area for >0.2 seconds. For each fixation, the start time of fixation, duration, and end-time of fixation were documented. Pre-defined AOIs were identified a priori by consensus via discussion amongst research team, and included the patient, bedside doctor, paramedic, monitor, recording nurse, medication nurse, procedure nurse, fluids, oxygen, checklist, and respiratory therapist.

RESULTS

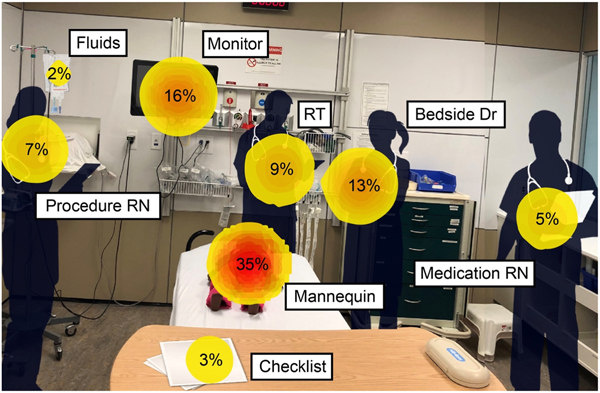

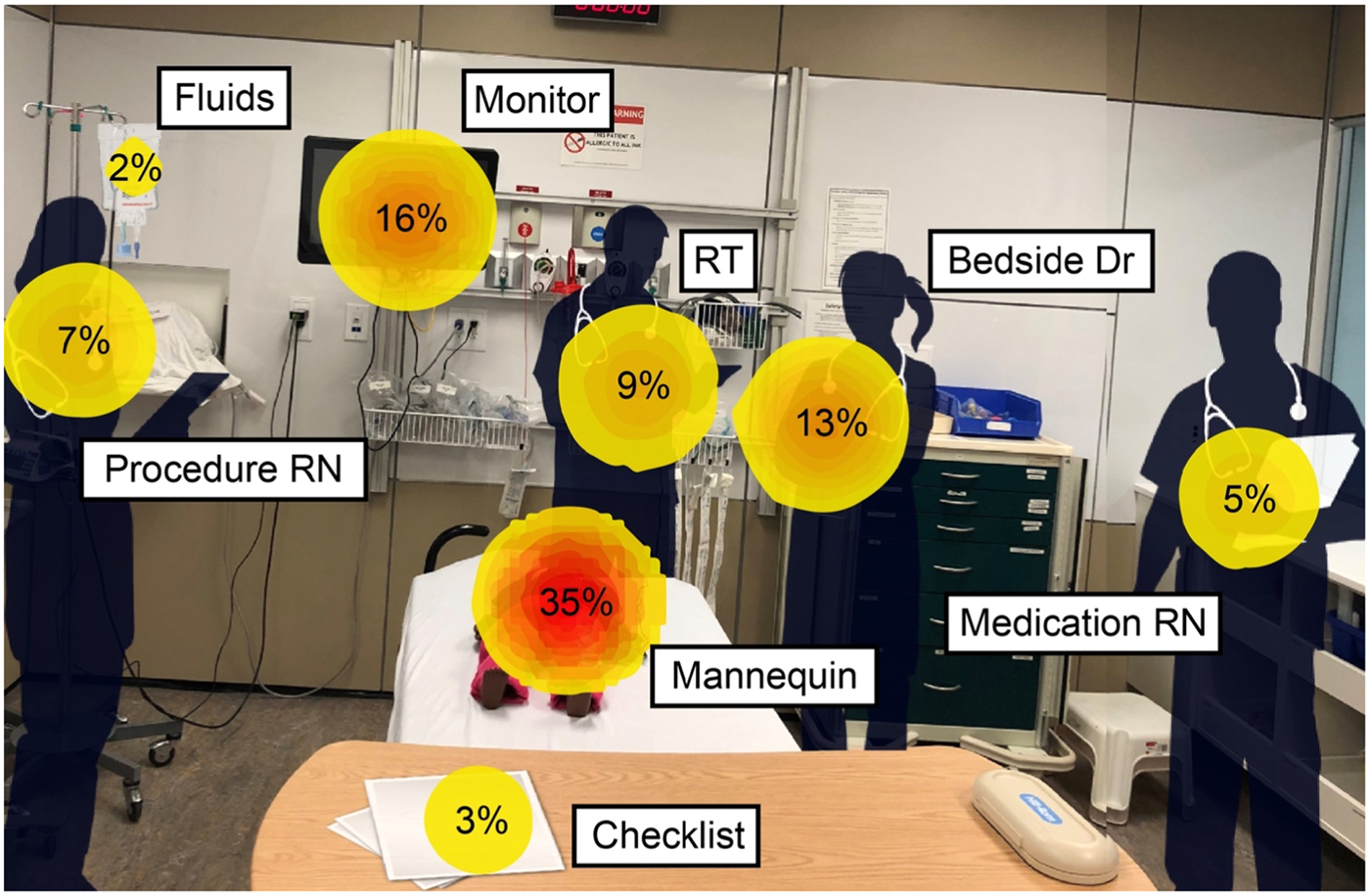

Nine video sessions were recorded, seven analysed, and two excluded due to loss of calibration mid-simulation. While cumbersome at times, eye-tracking devices were well tolerated by participants and did not impede their ability to make decisions or perform tasks as a TTL; 35% of eye fixations were directed towards the mannequin, 16% towards the monitor, and 13% towards the bedside doctor (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Figure 1. Heat map representing gaze preference towards pre-defined AOIs from most commonly viewed to least commonly viewed. This is depicted by the percentage, size of circle as well as colour. A darker core within the circle relates to an increased proportion of fixations during the simulation. RT=respiratory therapist; RN=registered nurse; Dr=doctor.

Table 1. Descriptive summary of average number of fixations, total time spent per fixation, average fixation time, and average proportion of fixations as a percentage across all AOIs

EMT=emergency medical technician; RT=respiratory therapist.

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests that use of eye tracking for simulated pediatric trauma is feasible, and that TTLs primarily fixate on the patient during resuscitation. Exploring patterns of visual fixation amongst TTLs shed light on one key element of situational awareness (i.e., Level 1), verifying that amongst PEM physicians, patient assessment serves as a key source of information during trauma. The AOIs that we studied include both “human” (i.e., including simulated patient) and non-human elements. Social norms dictate some degree of visual fixation when another human being is speaking compared to the observation of a piece of equipment. Likewise, a patient who is speaking may get even more fixation than one who is obtunded. These social norms are balanced against the importance of data/information offered by objects in the clinical environment – all variables that likely contributed to patterns of visual fixation amongst TTLs.

Our study adds to existing knowledge of the application of eye tracking in medical education, but is the first of its kind in pediatric trauma.Reference Ashraf, Sodergren and Merali5–Reference White, Braund and Howes7 In neonatal resuscitation, gaze preference amongst six expert consultants was focused primarily towards the monitor rather than the neonate.Reference Law, Cheung and Wagner8 In a simulated pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) environment, expert consultants focused their gaze predominantly on the chest and airway of the patient, whereas novice clinicians had visual preference directed towards the defibrillator.Reference McNaughten, Hart and Gallagher9 Both studies elucidate an important difference in visual fixation during resuscitation, with the PICU study indicating a role for eye tracking in characterizing expert behaviours.

The small size and descriptive nature of this study is a limitation. Because this was a simulation-based study, we cannot confirm whether our results are generalizable to the real clinical environment. Our study was not designed to determine whether focusing visual fixation on the patient leads to a more effective resuscitation. Mis-calibration (movement of the camera off of its pivot) of the eye-tracking unit was a challenge and resulted in two videos being removed from analysis. We don’t foresee this as a feasibility issue moving forward because new eye-tracking devices have improved calibration functionality. Apart from this, no other technical malfunctions were encountered with the eye-tracking units. Some participants reported the unit as being cumbersome at times, but all felt that this did not subjectively affect their ability to lead the resuscitation. In fact, most participants described not noticing the eye-tracking device after only a couple of minutes.

Our study provides data supporting the use and feasibility of eye tracking in pediatric trauma. In the future, we hope to compare and contrast eye-tracking behaviours in trainees versus attending physicians.Reference White, Braund and Howes7 Assuming that experts have a better sense of what is important to focus on, contrasting this to trainee’s visual fixation may identify opportunities for behaviour change.Reference Henneman, Cunningham and Fisher10 Secondly, we hope to study visual eye tracking in other high-stakes clinical contexts (e.g., cardiac arrest) and during technical skills (e.g., intubation). We believe that the use of eye technology can enhance our understanding of situational awareness in various clinical contexts, thus providing a source of data to inform positive change in clinical practice.

Competing interests

None declared.