Introduction

This article reflects on the knowledge and experience of North Korean music and dance among North Koreans who now reside in Britain. In particular, we explore their memories from before they escaped the isolated so-called socialist paradise. North Koreans mostly arrived in Britain between 2004 and 2008; they arrived as refugees and applied for asylum. Although the last four decades has seen much ethnomusicological research on music and migration, we remain mindful of Reyes Schramm’s argument about the importance of studying refugee music to better understand music traditions (1986, 1999). As with other parts of the world, though, today there are a multitude of online and published materials on North Korea, including on music and dance, most emanating from the country. Given that there are few if any opportunities to conduct fieldwork inside the country, researchers typically use the available materials to construct accounts. But to what extent do the memories of North Koreans who are resident in Britain contrast and challenge the online and published materials?

Setting the Scene

The Korean peninsula, for many centuries home to a unified state, was divided into two at the end of the Pacific War. The Soviet Union only declared war on Japan on 9 August 1945, and at that point Washington officials hurriedly proposed a demarcation line at the 38th parallel that would allow the Soviets to accept the Japanese surrender to the north of the peninsula and the Americans to the south. At a meeting in Moscow in December 1945, the Allies agreed to a multilateral trusteeship for Korea, with a provisional government staffed by Koreans. But the idea stalled as the two occupying forces attempted to set up administrations that would mirror their own political ideology. The result was that two rival states were established in 1948, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and the Republic of Korea (South Korea). Both states claimed sole legitimacy for governing the peninsula. Conflict soon became inevitable, and when northern troops poured across the demarcation line on 25 June 1950, the Korean War erupted. The war claimed some four million lives and displaced millions of Koreans; South Koreans refer to “ch’ŏnman” (literally, 10,000,000) displaced families (Foley Reference Foley2002).Footnote 1 People migrated to the North and South: Christians, landowners, and those who had worked for the Japanese moved south; activists, workers’ leaders, and leftists (including many writers and artists) moved north. Although an armistice was agreed in 1953, no peace treaty was ever signed; rather, the 38th parallel became the heavily fortified Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), enshrining the continuing division.

Kim Il Sung (1912–94) outmaneuvred rivals to become leader of the new northern state. Following Stalin’s death, the split between China and the Soviet Union and a challenge to Kim’s power unleashed internal purges and turned North Korea inward. North Korea developed a nationalism based on isolationism. This featured a cult of personality around Kim, which was bolstered by a new ideology, juche [chuch’e], cast as three pillars—independence, self-reliance, and principleFootnote 2—and by a mass movement, the Ch’ŏllima undong (Flying Horse Movement), that made the everyday extraordinary, with Kim the arbiter of all. Kim’s autocratic power was made absolute in his May 22 Instructions (5.25 kyoshi) of 1967, and although in death Kim Il Sung remains the “Eternal President,” in time his power passed to his son, Kim Jong Il (1942–2011) and grandson, Kim Jong Un (b. 1984).Footnote 3

North Korea sealed it borders. It allowed no dissent. Arbitrary detention was coupled to a punitive penal code, making violence an everyday control mechanism.Footnote 4 Artists, including musicians and dancers, were reined in through a literary art theory (the munye iron) that framed artistic work not in terms of technical expertise, aesthetics, or creativity, but in reference to model forms and appropriate incorporation of ideological “seeds” (chongja). Some chose to escape North Korea, and although the total number of people who have done so is unknown—not least because many live out of sight in China, Russia, and beyondFootnote 5—33,882 “defectors” (talbukcha) or “new settlers” (saet’onin) had entered South Korea by 2022.Footnote 6 In South Korea, they were required to go through a residential reeducation and settlement programme, but the challenges they faced in acquiring social capital (Lankov Reference Lankov, Haggard and Noland2006; Kang Reference Kang2013; Bell Reference Bell2013a; Song and Bell Reference Song and Bell2019)Footnote 7 led many to move to third countries, including Britain, as “secondary migrants.”Footnote 8

Writing about North Korean Music and Dance

A common refrain about North Korea is that “we do not know enough!” Academic fieldwork in any standard sense is not possible: even when access is allowed, itineraries are heavily restricted and free movement is not permitted. Those permitted to visit must be accompanied by “guides” and their interactions are monitored. Access to materials is controlled and, although North Korea is a highly literate and centralised state with extensive state-controlled publishing, only materials consistent with current ideology are available in state libraries. Do, then, the materials that exist represent the reality? The North Korean state is adept at showing what it wants foreigners to see (Fahy Reference Fahy2019, 229–60), hence the validity of accounts based on state-sanctioned materials accessed from abroad (or reflecting short, tourist-oriented visits to the country) must be critiqued. During a research trip in 1992, Howard recognised that much was being hidden from him as he walked the corridors of the Pyongyang Music and Dance College (P’yŏngyang ŭmak muyong chong taehak).Footnote 9 He heard p’ansori (epic storytelling through song) being practiced by students, although all state-sanctioned publications state the genre was abandoned in 1964, after Kim Il Sung remarked it was old-fashioned and useless for youth or for soldiers marching into battle.Footnote 10 A musician played folksong melodies, quietly, and then muttered to Howard, “We don’t sing those songs anymore.” And, although the six-stringed literati zither, kŏmun’go, was officially discarded in the late 1960s, scholars and musicians intimated that it was still taught to some students.Footnote 11

This article complements Howard’s (Reference Howard2020) monograph, the first comprehensive English-language account of music and dance in North Korea, and Sung’s (Reference Sung2021) doctoral dissertation, the sole study of music among the North and South Korean diaspora in Britain.Footnote 12 Several researchers have worked with North Korean musicians living in South Korea (e.g., Yu Reference Yu2007; Koo Reference Koo2016, Reference Koo and Defrance2019; Sands Reference Sands2021), and there are a rapidly multiplying number of accounts by South Korean scholars.Footnote 13 However, in respect to South Korean research, three comments are in order. First, North Koreans in the South tend to assimilate in their new homeland, and in their efforts to disguise their northern roots rarely attempt to maintain their social and cultural practices (Yun Reference Injin2011, 8; Bell Reference Bell2013b). Second, the South Korean national security law limits free discussion and debate and proscribes watching or listening to northern broadcasts or accessing Internet uploads. As a result, scholars are primarily reliant on southern archives that store materials from the North but control access and prohibit copying, although a small body of northern literature has been reprinted in Seoul at times when the security law was not strictly imposed. Third, the desire for (re)unification and a belief that the peninsula has for millennia been inhabited by a homogeneous ethnic group can colour commentary, favouring explorations of ties that bind rather than analyses of ideology and difference.

North Koreans Resident in Britain

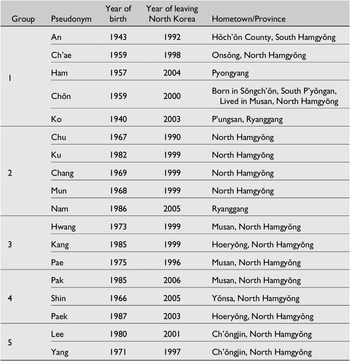

From 2004, North Koreans entered Britain as refugees and applied for asylum. In Britain, they are not subject to the prohibitions on listening to and watching North Korean materials that are in place in South Korea and, as Sung’s research (2021) shows, some maintain their identity partly by actively accessing contemporary North Korean media. In 2021–22, we interviewed eighteen North Korean residents in Britain ranging in age from thirty-six (born in 1987) to eighty-three (born in 1940) who escaped North Korea between 1990 and 2006 (Table 1). They left in various ways and for various reasons, although the famine during the 1990s that North Korea refers to as its “arduous march” (or “march of suffering,” konan ŭi haenggun) was often mentioned. Prior to leaving, most had lived in North Hamgyŏng or Ryanggang provinces, which border China, separated by the often narrow and shallow Tumen River. As long as border guards were bribed or otherwise occupied, the river facilitated their escape. Additionally, one interviewee came from South Hamgyŏng, one from the capital, Pyongyang, and one had grown up in South P’yŏngan province to the country’s west. Most, before coming to Britain, had reached and settled in South Korea. A common refrain used to justify their secondary migration was the prejudice they suffered in South Korea due to economic marginality, low skill levels, and poor education. Also, as An told us, “We tried to use the South Korean dialect, because we stood out too much if we spoke in a North Korean way. It was really awkward for us.”

Table 1. North Korean residents in Britain, as interviewed

Insecurity means that North Koreans resident in Britain are cautious and defensive. They are reluctant to meet and be interviewed (Song and Denney Reference Song and Denney2019). However, Sung has developed trust within the community since 2016, when she began to teach the Korean twelve-stringed kayagŭm zither to elderly community members (Sung Reference Sung2022, 98–100) and regularly attend and participate in community events. We held interviews between November 2021 and May 2022, but because the community reserves weekends for family and church activities, and because most members work multiple poorly paid jobs, interviews were held at restaurants or cafes near workplaces, before starting the workday or during lunch breaks. Interviewees preferred group sessions, feeling that the presence of others helped to correct and clarify their individual memories. Two, Ham and Nam, agreed to individual interviews, to allow us to dig more deeply into their experiences as a professional musician and a schoolteacher, respectively. We recruited five groups. Two of the first group had learnt the zither from Sung, and they introduced three additional members to the group. The second group was assembled with the help of a community member who had helped Sung’s doctoral research; this group consisted of five members active in promoting community identity through the North Korean Residents’ Society (Chaeyŏng t’albungmin yŏnhaphoe).Footnote 14 A snowballing methodology, where one member of each of the first two groups introduced us to others, recruited the three additional groups.

Here we pseudonymise all research participants, our method being to substitute common Korean family names and remove given names. We omit comments that might lead to censure from other members of the community or that could facilitate reprisals in North Korea—where the law of association deems that when somebody “illegally” leaves the country, three generations of their family should be punished. Indeed, Kang told us that because she had escaped North Korea, her sister had been unable to marry. Nam countered that only important families are punished these days when a family member escapes, but also noted her parents couldn’t talk openly about her after she left, and that their home was bugged in case she tried to make contact. However, Nam also told us she talked with her family on regular video calls. To do so, she had to pay large amounts to Chinese middlemen prepared to smuggle mobile phones into North Korea because state bodies closely controlled phone lines and blocked Internet access. To minimise the risks, she and her family members called each other by nicknames, never their real names.

In 2004, the British government announced that North Koreans would be admitted as refugees, and all those we interviewed arrived in Britain between 2005 and 2008 except for one who arrived in 2015. Accepted as refugees, they were given permission to remain in Britain for five years. They were sent to live in social housing in places far from London, but gradually gravitated to the Kingston/New Malden area to London’s southwest, where most of the South Korean diaspora lived. There, North Koreans were able to take advantage of a shared language, eat familiar foods, and access work. Typically, they took low-paid jobs, often multiple part-time jobs. Sung (Reference Sung2021) details how they increasingly live as a single diaspora alongside their southern brethren.Footnote 15 They maintain a subcultural identity through the North Korean Residents’ Society and hold cultural events such as end-of-year parties and an annual gathering at Ch’usŏk (the lunar harvest festival, which usually falls in September). They moderate their identity within the Korean diaspora by avoiding ideological lyrics and themes with respect to singing and performing music and dance.

Those who arrived prior to 2008 were, after five years of continuous residency, entitled to “indefinite leave to remain” in Britain (i.e., settlement),Footnote 16 allowing them to apply for citizenship. A number of factors discouraged this happening. Applying for citizenship involved passing two tests that proved too much of a challenge for many, one about life in Britain and one for English language fluency. However, the major concern was that Britain might repatriate them to South Korea. Stories circulated of friends and acquaintances being ordered to leave, and they were well aware that South Korea’s constitutional claims over all the peninsula and all its people meant that North Koreans entering the South were recognised as South Korean citizens. As secondary migrants, then, North Koreans knew their asylum claims in Britain could be rendered null and void if they admitted to previously entering South Korea. Thus, they “often change[d] their names and further obfuscate[d] the details of their life prior to arrival” (Song and Bell Reference Song and Bell2019, 5, 23).Footnote 17 Also, South Korea remains a place to settle, should it be needed, but South Korea bans dual citizenship and requires any Korean who takes another citizenship to surrender their South Korean passport. And, not surprisingly, secondary migration is embarrassing for South Korean authorities (ibid., 8). Our anecdotal evidence suggests that during the COVID-19 pandemic at least one hundred left Britain for South Korea, as government lockdowns in Britain created work volatility and as South Korea proved better able to control the virus spread.Footnote 18 To an extent, then, North Korean residents in Britain are, per Ögüt’s (Reference Ögüt2015) formulation, transit migrants who are ambivalent about returning and who, even if they long for their hometowns in the North (as reported by Kim Reference Sŏkhyang2018, 215–18), recognise that the South may at some later date become their homeland.

A further concern among residents was the North Korea diplomatic presence in Britain. Some believed that this allowed state agents to operate clandestinely. State violence was familiar to those we interviewed. Ham, a former cellist, recalled her mother coming one day to her ensemble’s studio to tell her that her brother had been taken. “His family was taken to a detention camp: him, his wife, and his children. When somebody is taken, you cannot find them, and you don’t know the reason. You can’t tell anybody, or you will be accused of the same unknown thing.” Ko recalled: “My aunt was taken to a detention camp with all her sons. Her daughters were left because they had married.” An, an elderly former musician, lost his job in an art troupe when it was discovered his father had been a church elder before 1945. “My parents were beaten and whipped. They took everything from the house, even spoons and bedding. I had to sleep on rice straw, just like a pig.” An was sent to a mine, where he worked as an electrician for thirty years before escaping. He had not, though, been sent to a camp because, as Ham told it, “He was safe because he was so quiet, and he let people look down on him.”

A Daily Diet of Songs

Regardless of age, those we talked with knew the same songs, but commented that now that they were in Britain, “there are no songs we can sing, because all our songs are about the Kim family or the Korean Workers Party” (An). This, of course, is an overstatement, and Nam voiced the consensus view that, even back in North Korea, “People like songs when they do not praise the leadership.” The songs we discussed all predated 2006 (i.e., before interviewees left North Korea), before the state began to upload songs to YouTube and Youku, and before the regime of Kim Jong Un ushered in new styles of pop. Several admitted to listening to more recent songs. However, sensitivities—in particular, the potential for a resident to be accused by others in the Korean diaspora of harbouring sympathies for current or recent state ideology, rhetoric, or action—meant that we refrained from exploring their knowledge of recent events and new music.Footnote 19

In North Korea, they recalled, days started and ended with songs. Street speakers and speakers fitted in apartment walls crackled to life at 5AM, broadcasting songs. They did so regardless of the frequent power cuts: “When there was no electricity and nothing seemed to be working, I still heard the broadcasts” (Yang); “[it was as if] the speakers were on a different circuit to everybody’s electricity supply” (Lee). Known as “morning exercise,” such broadcasts descend from 1930s Japanese colonial practice; even in South Korea public speakers burst into life early each morning until the mid-1980s, spawning a genre of “healthy songs” (kŏnjŏn kayo; Maliangkay Reference Maliangkay and Howard2006), similar to ideological repertoires in the North. Ham and Chŏn disagreed about whether listening was compulsory, agreeing that only the military and students living in dormitories and hostels had to do exercises to the broadcasts. But apartment speakers had no volume controls and no “off” button, and interviewees recalled checks being made to ensure they functioned and nobody had tampered with them.Footnote 20 Radios and televisions, likewise, were preset to receive only North Korean channels. However, Pak and Nam told us that while in North Korea they listened to South Korean pop and watched television dramas using VCDs, and Nam reported learning that it is currently easier to access South Korean materials because of the availability of easily smuggled USB sticks.

Among songs, “Kim Ilsŏng changgun ŭi norae/Song of General Kim Il Sung” was the song heard most when living in North Korea. It was unquestionably, Chu told us, the most important song:

As soon as you are born you must learn it. It functions like other countries use national anthems, even though North Korea also has a national anthem.… We didn’t sing the national anthem much, and after the famine began, we didn’t sing it at all. At special events, we would sing it at the beginning and end, rather than “General Kim,” but everywhere else we sang “General Kim” much more often.Footnote 21

By way of commentary, the music for “General Kim,” composed by Kim Wŏn’gyun (1917–2002), treads a path familiar from Soviet or Chinese mass songs (massovaya persnya/geming guqu), combining musical simplicity with ideological lyrics. Written in June 1946, it bolstered the revisionist cult of personality surrounding Kim Il Sung, rendering him as the supreme guerrilla leader. It quickly became the de facto anthem, so much so that Seoul residents who endured occupation by North Korean forces in 1950 at the beginning of the Korean War remember invading soldiers singing it: “That damn song, I still can’t get it out of my head,” was how Hong Samyŏng, an eighty-five-year-old Seoul resident and former director of the Korean Research Foundation, reacted when we asked him about the song in December 2022. Even Polish and Bulgarian villagers who hosted North Korean children sent to them for safety in 1950 still remember it.Footnote 22

Television broadcasts used to begin at 5PM and end at 10PM. Chu recalled: “Broadcasts began with the national anthem [also with music by Kim Wŏn’gyun], and everybody sat in front of the TV waiting for programmes to start.… All three verses were again sung to images of the North Korean flag when broadcasts ended.” According to Kang, “Tongjiae ŭi norae/Song of Comradeship” was broadcast on apartment speakers and used to signal bedtime. The ever-present songs spread ideology, so, as Pak remarked, “If you have your eyes open, you can’t help but listen.… You don’t have to be able to sing, but as you keep listening, you learn all the songs.” Nam told us she wrote down song lyrics: “We were given notebooks. I remember using them in secondary school, particularly so I could memorise popular songs. We would write down cool titles alongside the lyrics. Sometimes we secretly wrote down the lyrics to South Korean songs.” Listening to recordings, along with watching TV, though, required electricity, and memories of regular power cuts were vivid. We were told—although this may have reflected life in the provinces—that the unreliability of mains electricity resulted in a slow take-up of VCD players, and a lingering preference for battery-powered cassette players. While new songs took time to penetrate the countryside, lyrics typically arrived before the new melodies were heard because they were printed in newspapers.

Folksongs were generally regarded as boring. In contrast, the two state-authorised pop ensembles founded in the 1980s, Wangjaesan and Pochonbo, appealed to many of our interviewees who had been youths at the time. Initially, Wangjaesan, named after a 1933 meeting of guerrillas in Mount Wangjae presided over by Kim Il Sung, was the more acoustic, based on 1930s popular styles (now known in North Korea as taejung kayo, lit. “mass song”). Pochonbo, named after the site of a 1937 battle that Kim led against Japanese police, was more electronic and “modern.” The appeal was not just the music but also the costumes: “blouses with fluffy arms” (Pae),Footnote 23 “trousers almost like skirts, and big butt trousers” (Kang). Somewhat counterintuitively, Wangjaesan was remembered as the more exciting, primarily because in the late 1990s the band reinvigorated its sagging appeal by shifting toward risqué disco routines. Elsewhere it has been reported that these routines proved too much for North Korea’s censors, and the group disappeared in 2013 amid rumours that key members had been executed by firing squad.

Our research participants discussed South Korean K-pop circulation among today’s youth in North Korea, laughing together at the mention of coded comments such as “Don’t you have songs from that side?” (asking if friends had K-pop recordings) and, in recent years, “Have you ever worn a backpack?” (asking whether somebody had listened to the boy-band BTS).Footnote 24 Several interviewees recalled illicitly listening to K-pop in the North. One, a mother, crawled under the bed covers with her daughter to listen. Some initially thought K-pop came from the Korean community in northeastern China rather than from South Korea. Paek remarked: “Listening to or watching South Korean pop and TV dramas was only for those who could afford machines to play them on. People like me who worked hard at the market all day long could never afford a machine.” Everyone knew that it was dangerous to listen to or watch South Korean cultural products. Pak was caught:

I had a South Korean movie [on VCD] at home. One day, they searched my house and found it. My aunt blamed me because I was still a child so would only be punished a little. I was taken away and interrogated all day, until I was able to call my uncle, who bribed them to release me.

Several interviewees were disappointed when, after leaving the country, they discovered many apparently North Korean songs were in reality Russian or Chinese; Korean lyrics that fit state ideology had simply been substituted. And, once she escaped North Korea, Kang reported her surprise that songs need not be a constant soundtrack to daily life. She was suddenly free to choose what to listen to:Footnote 25

When I arrived in China, the best thing I discovered was earphones. I could listen to songs I wanted to when I wanted to. In North Korea, even if you don’t want to listen to music, you can’t help but do so because it is played everywhere all the time, at schools and on the street.

Music in Schools, Music Training

When we arrived at school in the morning we gathered in the playground. Instead of going straight into the classroom, we all marched to music. I remember the song “Soyŏn ppalchisan ŭi norae/Song of the Youth Partisan,” which we sang a lot as members of the Youth Corps (Kang).

Originating in a film and composed by Kim Hagyŏn in 1951, “Youth Partisan” has strikingly violent lyrics for children: “Let’s destroy all the bloodthirsty invaders!” “I went out with a gun on my shoulder for revenge.” Such lyrics illustrate how patriotism was—and today continues to be—fostered by the manufactured image of a nation permanently at war.Footnote 26 Although interviewees discussed other militaristic children’s songs (e.g., “Much’irŭja!/Let us Defeat!”) along with plenty of songs about the Kim family leaders (e.g., “Sonyŏn changsu/The Young Commander”), not all songs were thought of as ideological. Kang told us about the first song she learnt in nursery school, the much celebrated “Kohyang ŭi pom/Hometown Spring,” a song written around 1920 by Hong Nanp’a (1897–1941). Pak added, in the same group interview, that “Hometown Spring” was a fundamental song for all Koreans of her generation. Shin recalled a song written specifically for children, “Kkotpongori p’iŏnanŭn/Blooming Flower Buds,” initiating a discussion of how children’s songs existed as a separate genre, although the memory of these had faded for many of the older interviewees. Paek, though, who was born in 1987 and who attended school only intermittently during the famine years, knew little apart from children’s songs, some of which she had memorised from cartoons broadcast on television. Only older interviewees recalled folksongs, although by the time most of them were at school their importance was said to be waning; still, folksongs give the structural foundation for the national song style (Howard Reference Howard2020, 35–42, citing Ri Ch’anggu Reference Ch’anggu1990).

Music lessons formed a core part of school life for all interviewees. Songs predominated, but two other elements were taught. One was notation; rhythmic notation was taught at junior school (to allow the eponymous nongak/p’ungmul percussion bands of rural Korea to be workshopped) and melodic notation was taught in middle school, along with a simple dance notation referred to as chamo p’yogibŏp (“alphabet notation”; Howard Reference Howard2020, 195–203). The third component was a particular vocalisation, mixing lyricism and projection, and described in North Korean literature in relation to juche ideology as chuch’e ch’angbŏp (“self-reliance singing method”); our interviewees referred to this using the more generic term, palsŏngbŏp (vocalisation). Teachers used solfege, and typically accompanied class singing with a harmonium (palp’unggŭm) within classrooms or an accordion (sonp’unggŭm) outside. Nam remembered that keyboards began to be distributed around the turn of the millennium. Pianos were rare in schools, and were remembered as status symbols found only in the homes of officials.Footnote 27 Textbooks were, we were told, distributed to students until the 1990s, but supplies then dried up when the famine began. As the situation worsened, Paek told us, classes were only held in the mornings, so that teams of children could be sent out each afternoon to work in fields and on construction sites, or to clean public spaces.

Although North Korean literature indicates that the state supplies instruments for schools, only plastic melodicas were remembered as being distributed and taught in class. There were other instruments, but these were reserved for selected students. Nam recalled:

In my school, there was a separate room where, when classes finished, music group members went to practice (ŭmak sojo). It housed instruments belonging to the school, and stored private instruments bought by the families of individual group members.

Students selected for music training studied one of three specialties: choral/vocal,Footnote 28 ensembles/instruments, and narration. Narration related to vocalisation, the chuch’e ch’angbŏp, and taught the heightened speech style familiar from broadcasts and public announcements. Our interviewees agreed that the number of music groups declined during the famine (as reported by Hyun and Ahn Reference Hyun and Ahn2018). Post-2000, and still today, Hwang reinforced anecdotal evidence that indicates stocks of instruments are less than before, not least because “It’s hard to make ends meet in North Korea, so even teachers try to steal the instruments.” Students selected for training rehearsed in the afternoons. Choirs were particularly common (as discussed by Ko Reference Ko, Howard and Kim2019, 87); Chu, reflecting on the famine years but with one eye on today, told us that “If you were good at singing, you should train in a choir, even if you didn’t want to.” Explaining the reason why, Shin confirmed that she had joined a music group at school because students needed to do less or no farming, construction, or cleaning work. Thus, she remembered fierce competition to participate, and that it was common to bribe teachers. But there were also considerable costs because parents needed to buy instruments and pay for private lessons. Hence, music training was thought of as the preserve of wealthy families, and it was thought to be normal that priority was given to those with good family backgrounds.Footnote 29 Indeed, music training was, and is, seen as a way to improve a family’s standing, the preeminent example today being Ri Sŏlju, who trained as a singer from elementary school through to college and briefly performed professionally before being chosen as wife to the current leader, Kim Jong Un. In the past, advantage also accrued because musicians were technically members of the military, as Ch’ae and Chŏn discussed:

Ch’ae: North Korea has created a world where it’s harder to get into the Party than get military stars.

Chon: When you finish military service you have a chance to be considered for membership of the Party, but if you work in music propaganda, it is very easy to be selected for membership.

We were told how a few students from school music groups were selected by officials early each April, that is, before Kim Il Sung’s birthday on 15 April, an important annual celebration. The selection criteria, though, were not just musical skill, but height, appearance, and deportment. Those selected would be enrolled in “children’s palaces” (two operated in Pyongyang and one in each province) for specialist training. On graduation those chosen to become professional musicians or dancers entered the Pyongyang Music and Dance College. Ham confirmed the route progression. She studied cello as a secondary school student. She was able to use a school instrument, but to advance, her family knew they had to buy a better instrument and pay for private lessons; each lesson, she recalled, cost the equivalent of a kilo of rice, a considerable sum. She practiced every night until late, and was duly selected for various regional events and competitions. Her school rarely had funds to support her, so her family had to pay any costs associated with participating. She was then admitted to the college, and after graduation joined the Korean People’s Army Troupe (Chosŏn inmin’gun hyŏpchudan). Her troupe regularly played for state events, and was ranked just below the North’s most prestigious group, the Mansudae Art Troupe (Mansudae yesuldan).Footnote 30 Nam, by contrast, played the accordion as a hobby and her school ran an accordion group. However, she wanted to learn the guitar, but her parents could not afford an instrument, and she also lived far from the capital, in the mountainous Ryangyang. She was not selected for training as a professional musician but, rather, was chosen to become an elementary school teacher. At college she learnt the harmonium; the college, she told us, had three, all in bad condition.Footnote 31

Chŏn studied narration that, she explained, was “like acting.” She began when she was seven years old and was chosen to go to Pyongyang many times to narrate solo, narrate alongside others, and sing. She worked with “the best professionals from each province. You rehearsed by constantly repeating, and if you made a mistake you were in serious trouble. We learnt because we were hit by our teachers.” Although she wasn’t selected to continue training at college, her mother, Ham, wanted Chŏn to become an actor and pushed for her to study narration at school. Eventually, her daughter gained admission to study acting at the Pyongyang University of Dramatic and Cinematic Arts (Pyŏngyang yŏn’guk yŏnghwa taehak), but only after Ham became something of a tiger mother: “I made her learn guitar, accordion and singing. To be an actor, she needed to know the basics of musical instruments. I also got her to sing ‘Nae kohyang ŭi chip/My Beloved Hometown Home.’” The song featured in the first North Korean film, Nae kohyang/My Beloved Hometown (1949), which committed to celluloid what then became Kim Il Sung’s official childhood biography.

Several interviewees mentioned a different selection event at school, for what they referred to as okwa Footnote 32 —that is, girls chosen to serve the leadership. They recognised the discrepancy between what they had been taught—that the courtesan tradition was an aspect of feudal life that socialism had obliterated—and what was rumoured to be expected of okwa. They associated okwa particularly with Kim Jong Il, the second family leader. His penchant for okwa and boozy parties was revealed in recordings secretly made by the South Korean film director Shin Sangok after he escaped following his abduction to the North on Kim’s orders.Footnote 33 Here, though, is one exchange from our interviews:

Nam: When I was a student, I thought being selected for the okwa was a great honour. When we were young teenagers, Party officials came into the schools to choose us. They stood the students up and checked their appearance and their personal family background.

Chu: You need a physical examination first!

Nam: You shouldn’t have any scars. I have a scar on my face, and I remember I cried a lot because I wasn’t selected. My friends and I thought it would be such an honour, because we thought the chosen girls became escorts for the leaders.

Chu: It’s like being selected as a gift for the king in the past. These days, though, some of the girls end up working in North Korean restaurants overseas.

There are rumours that profits from overseas restaurant operations go to the leader. Hence the implication of Chu’s comment is that the service given by okwa has changed under the current leader, Kim Jong Un.

Music at Work, and Music at Gatherings

I come from a city with the largest mine in the country. When I was a student, I was forced to go play the French horn every morning. I had to arrive outside the railway station by 7AM, because people walk from there to work around 7.20AM. I played with other musicians for an hour as a line of students waved flags (Pak).

Public transport was poor. As a result, “people queued and queued to go to work, [and] music was played during the rush hours” (Lee). Bands of children and students were often tasked with the job, “so workers would enjoy commuting … and to cheer them up” (Nam). Workplaces had their own propaganda troupes, and Nam told us about a construction site in front of the university she attended: “They were building a theatre to be named after Kim Il Sung’s first wife,Footnote 34 and a task force (kidongdae) would stand at the entrance every morning, playing guitars and singing songs about socialism as the workers clocked in for work.” Public places also had permanent speakers set up, which broadcast songs during the working day.

Special days, foundation days, and the birthdays of leaders demanded group performances to demonstrate the unity of the people in building socialism. For these, each workplace assembled a dance team of workers in their twenties and thirties (workers collectively known as the ch’ŏngsonyŏn, lit., unmarried young adults). Schools also put teams together for some events. Each team rehearsed before and after work or classes, accompanied by an accordion or using recordings piped in through portable speakers. For the celebration proper, all the teams came together, most famously on Kim Il Sung’s birthday, when a central celebration held in Kim Il Sung Square in Pyongyang was broadcast nationwide. In Pyongyang, everyone got a new costume—a traditional chosŏnbok flowing dress and short top for women,Footnote 35 a plain suit for men. Outside the capital, celebrations were less lavish, and our interviewees recalled wearing less formal attire—usually long black skirts and white blouses for the women. In Pyongyang, the television cameras focused on professional dancers, acrobats, and musicians, around which the multiple workplace teams—perhaps 50,000 or more people—fanned out to each corner of the square. In the countryside, broadcast and prerecorded music sufficed, and one interviewee remembered a van with speakers, while another thought that a single team of technicians arrived in town, setting up and controlling lighting for the statues and buildings as well as banks of speakers.

The teams danced to songs, each team forming its own circle. They ran through a sequence of movements: forward-step-step-step, back-step-step-step, spot-step-step-clap, turn-step-step-clap, and so on. We suggest that team dances indicate one reason why dance notation was taught in schools. There was a standard preparation routine, which Pae remembered from her school days:

Each school picked two students for training. My friend and I went to Ch’ŏngjin, the provincial capital. Over three days we learnt the dances from specialists, then came back to our school and taught all the other students. There were many songs, but the dance moves were not hard, and only a few different steps were used, repeated for different songs.

Pak recalled how her work colleagues prepared:

All the dances were similar. We learnt by forming a circle and following a couple of people who stood in the middle. They had learnt the moves from the propaganda team. The moves weren’t hard, so you just quickly picked up how to move your feet properly. Our dancing created a good atmosphere on special days such as Kim Il Sung’s birthday, and, probably, dancing was fun for everybody.Footnote 36

Some events featured competitions, such as “Ch’ungsŏng ŭi norae moim/Singalong of Loyalty,” for which schools and workplaces rehearsed in secret. Coming together, they competed for prizes that might include a whole pig, or sacks of rice and sugar. The prospect of prizes, Shin recalled, made people highly competitive:

No group revealed what they were preparing. They would keep it secret from each other. Even a mother wouldn’t tell her child, or the child her mother, if they studied and worked in different places.

Music for the People: Classical Music and Opera

Among the North Korean residents we interviewed, two had worked as professional musicians and were familiar with how Western art music had once been performed in North Korea. All our interviewees had seen Western instruments and heard ensembles play pieces based on well-known songs while in North Korea, but several commented that they only encountered the term “classical music” after escaping the country. Western art music arrived in Korea in the late nineteenth century, and many of its early Korean exponents were taught at a particular mission school in Pyongyang (Chang Reference Chang2014).Footnote 37 Immediately after 1945, Western art music was heavily promoted, and its expert musicians lauded; a book by Ri Hirim and others (Reference Hirim, Hwail, Yŏngsŏp, Ŭngman, Pyŏnggak and Chongsang1956) lists the local performances of orchestral music by Ashrafi, Beethoven, Glinka, Ivanov, Kabalevsky, Liszt, Lyadov, Mussorgsky, Radishchev, Rimsky-Korsakov, Shostakovich, and Tchaikovsky. However, Ri’s book has long since disappeared from North Korean shelves, as has a 1957 volume of arias, Segye kagok sŏnjip, which reveals that singers and composers were studying Bizet, Glinka, Gounod, Rimsky-Korsakov, Smetana, Tchaikovsky, and Verdi. No Western opera was staged in Korea prior to the 1945 division, but in 1958 the Pyongyang Music and Dance College staged Tchaikovsky’s heavyweight Eugene Onegin (1879). Soviet cultural advisors were active, and a 1949 cultural exchange signed with the Soviets sent promising North Korean musicians to Moscow for training (Armstrong Reference Armstrong2003, 82–3). The exchange, though, proved short-lived, and those with international connections began to be purged in the mid-1950s. By the mid-1960s, all but locally produced music was banned. Ham, who trained at the college, took us through what happened:

I heard that Kim Il Sung had visited the Pyongyang Music and Dance College. It was before I studied there. He announced that we must bring Western instruments closer to Korean music, so that they played minjok ŭmak (national music). This was his order, so the college removed all foreign textbooks and teaching methods, and exiled musicians who had studied abroad to the countryside. New textbooks were introduced, and from then on students were taught to play Korean songs like “Arirang” on Western instruments. Everything was based on songs, that is, national music, although good arrangements for instruments were created. Over time, the skill levels of students deteriorated, so the college called back the teachers who had been sent into exile. Some had already died. And most of those who returned were suffering from poor health so could no longer teach properly.

We were allowed to play Beethoven’s works until 1963 or perhaps 1964. Later, when I graduated from the college and joined an art troupe, we were still able to practice such works, but not to play them in public. I wasn’t even allowed to listen to recordings of such works, although this restriction began to be eased some years later. At the time, I felt like my musical identity was being suppressed. I cried when I left North Korea and could suddenly listen to Western art music on the radio. It made me feel as if I was in my homeland before the authorities imposed so many restrictions.

Ham also remarked that the reason for banning Western art music was because it was not “cheerful” or “popular,” echoing Lenin and the Soviet (and Maoist) notion that art should not be written by out-of-touch intellectual artists but should come from the people. Lenin had riled against selfish artists who made use of “deliberate vagueness” (Lunacharsky Reference Lunacharsky1967, 259–60), and Kim Jong Il, the second leader of the family dynasty, regarded “music without politics” as “like a flower without scent” (cited in Yi Reference Hyŏnju2006, 167). Ham, however, saw hypocrisy in the ban, because she knew a friend who played Western art music for the almost daily private parties of Kim Jong Il: “The parties were all hidden from view. Kim liked Western art music, but he just didn’t allow us to perform it to the public.”

We note, though, that the ban was never total. Twice a year, Western art music continued to be performed. Once was during the April Spring Festival when, as part of the celebrations around Kim Il Sung’s birthday, foreign musicians were invited to Pyongyang. Some of their performances were broadcast because, as propaganda, they had utility. Howard observed a guest Italian conductor wielding his baton over the National Symphony Orchestra at the 2000 festival. After he left the stage, a North Korean conductor walked out, and led the orchestra in one of the same pieces. The subsequent broadcast was edited to juxtapose the lethargic performance under the Italian conductor with the vibrancy achieved by the domestic conductor. Festivals have also been organised each autumn by the Isang Yun Music Research Institute (Yun Isang Ŭmak Yŏn’guso), an institute set up under the Ministry of Culture in 1979 in honour of the most celebrated twentieth-century Korean composer, Yun Isang (1917–95). Yun lived for much of his life in Berlin but became a regular visitor to Pyongyang following his 1967 kidnap, repatriation, and imprisonment in South Korea during the dictatorship of Park Chung Hee. However, his compositions were avant-garde and serial, and although visiting German musicians have given performances of his and other European composers’ music at the festival,Footnote 38 only carefully selected audiences hear them: the performances are never broadcast. We note that a series of four feature films made in 1992 and 1993 about Yun’s life as a composer within the Minjokkwa unmyŏng (Nation and Destiny) series include much music but no single note by Yun; his avant-garde style is neither cheerful nor popular.

None of those we talked with had attended a National Symphony Orchestra concert. Some received free tickets to attend concerts by provincial orchestras; the tickets were distributed to workplaces and schools. Pak saw Wangjaesan when the pop group toured, but she had to buy her own ticket. Most only saw orchestras and pop groups on television. Much the same applied to revolutionary operas (hyŏngmyŏng kagŭk), where only Nam had seen an opera in a theatre. Partly, this was because the dedicated opera theatre was in Pyongyang, and the capital was (and is) off-limits to nonresidents. To visit, people from out of town required written permission countersigned by an official, but Nam was allowed to visit family relatives living in the capital. Five core revolutionary operas were created between 1971 and 1973. North Korean accounts state these had been performed 4,430 times by 1986 (e.g., Chosŏn ŭmak ryŏn’gam Reference Anon1987, 165), and two, P’i pada/Sea of Blood and Kkot panŭn ch’ŏnyŏ/The Flower Girl, toured the socialist and nonaligned world. Opera development was overseen by Kim Jong Il (as detailed in his 1974 treatise On the Art of Opera and in myriad other accounts),Footnote 39 and the five functioned as ideological compendia, intended to reinforce compliance among citizens. Hence, all but one of our interviewees had seen the operas as films or on television. Screenings in workplaces or local communities would end with group discussion sessions designed to check that ideological messages had been properly assimilated. Those we interviewed knew the plots, knew song titles, and could sing some songs, in particular “Haemada pomi onda/Spring Comes Every Year” from The Flower Girl. This opera memorialised strife during the Japanese colonial occupation of Korea and looked forward to liberation, embracing a subtext lacking subtlety: freedom and prosperity came to North Korea because of the benevolence and guidance of its only possible leader, Kim Il Sung:

To those who now live in Britain and have been robbed of their homeland, freedom and prosperity was never more than a mirage in North Korea.

Concluding Remarks

Music and migration is a common theme for ethnomusicological research, albeit one with blurred boundaries because of the multiplicity of reasons behind migration (Baily and Collyer Reference Baily and Collyer2006, 170; see also Toynbee and Dueck Reference Toynbee, Byron, Toynbee and Dueck2011). Writing has often linked to exile (Scheding and Levi Reference Scheding and Levi2010) or diasporic practices (Ramnarine Reference Ramnarine2007; Solomon Reference Solomon and Solomon2014), although recent scholarship points to how writing about migration is at a crossroads. In respect to this, the structural-functionalist language of continuity and adaptation associated with nation-states, identity, and tradition has been largely abandoned (Stokes Reference Stokes2020, 1, 7–8); academic discourse and the language of development agencies are increasingly at odds with each other (Impey, in Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Impey, Willson, Aksoy, Gill and Frishkopf2019, 287–9); and “system world” language is increasingly removed from “lifeworld” language (Frishkopf, after Habermas, in ibid., 304–5), limiting the scope for collaborative writing that addresses social needs (Aksoy Reference Aksoy2019; Shao Reference Shao, Diamond and Castelo-Branco2021).

Still, Reyes’s characterisation of the “disruption and loss of control, the traumas of escape, and the trying circumstances surrounding survival in a new and possibly hostile environment” (1986, 91) would be recognised by North Korean residents in Britain: as secondary migrants, their precarity involves negotiating relationships with a homeland as well as with a broader Korean diaspora. This article, however, is not intended as a discussion of music and migration. Nor is it a comprehensive account of music and dance in North Korea. Rather, we set out to supplement our recent accounts (Howard Reference Howard2020; Sung Reference Sung2021) by exploring the memories, knowledge, and experiences of the homeland among North Koreans resident in Britain.

When the British government announced in 2004 that it would allow North Koreans to enter the country as refugees, there was concern that this would encourage “economic migrants” from the Chinese Korean community, and so immigration authorities devised a series of questions to ask about ideology, politics, and recent events in North Korea. The aim was to unmask asylum seekers attempting to disguise their real identity, but the test often failed.Footnote 40 Why? Because most North Korean asylum seekers came from border regions distant to the capital, where the centralised distribution of information had largely ceased and where, during the famine years of the 1990s, central control temporarily evaporated. The test also failed because most were secondary migrants who arrived from South Korea, where they had gone through a settlement and reeducation programme. They were unaware of or unwilling to talk to the public image portrayed by North Korea in state-sanctioned materials. That image was always partial. That image was, largely, of the capital, Pyongyang. It is the image that gets infused into many accounts by Western journalists, although sensationalism is frequently added to what journalists and other visitors to the isolated state have been permitted to see.Footnote 41 We are, then, familiar with music and dance at kindergartens and schools, as portrayed in videos, where the reality is that these are filmed in kindergartens and schools reserved for the children of the elite living in Pyongyang. Again, images of mass performance spectacles also come from the capital. The impression we are given is that everybody “musics” and that everybody dances in what Kim refers to as the “theatrical state” (2010, 14–16).

The North Koreans we interviewed for this article told us less about the vital part that music and dance plays in life in their homeland than the official images promote. They revealed just how narrow their musical options, and how limited their experiences of music, had been. They knew the same music, regardless of their age. They woke up, went to school and work, and danced to the same songs. They witnessed a decline in music and dance taught, performed, and promoted during the 1990s. In daily life they knew not to ask too many questions, and not to step out of line, because they had friends and relatives who had vanished into the penal system or had been punished for infringing written and unwritten laws. It is true that the two former professional musicians had greater experience and knowledge but they, like others, recognised that in North Korea musical skill had less relevance than personal looks and deportment, family background, and status. And their lives as musicians were not easy: An, a violinist, was forced to leave his profession because of his father’s background and spent thirty years working in a mine before escaping; Ham, the cellist, witnessed her brother disappear and struggled to ensure her daughter could study acting.

Accounts of North Korean arts and culture are rapidly multiplying. However, with little prospect of conducting fieldwork in North Korea, communities of North Koreans abroad—whether refugees, defectors, asylum seekers, new citizens, or secondary migrants—encourage us to be wary. The images projected by the state require careful assessment, and one way to ensure we do this is to listen to the memories, knowledge, and experience of those who grew up and once lived there.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The author(s) declare none.