Introduction

In 1986, Argentina found itself in the early stages of democratization after a seven-year dictatorship and decades of profound institutional instability.Footnote 1 In this context, President Alfonsín launched a bold proposal with re-foundational purposes: moving the federal capital to the south of the country. Via nationwide television and a radio address on 15 April 1986, a proposed plan was announced to move the federal capital to Viedma, a small town with fewer than 30,000 people. During the announcement, the president presented a package of ambitious measures that went far beyond the relocation of the capital: ‘This plan is not only about establishing a new capital, creating a new province, reforming public administration, improving the administration of justice, or adopting a new political system. It is about creating the conditions for a new Republic that will offer expanded horizons in the minds of all Argentines.’Footnote 2

Among the administration’s initiatives, the relocation of the capital was to become the springboard for a series of processes to build the Second Republic. Despite initial enthusiasm, the plan fell short and was abandoned within two years. Later readings of this period conclude that the plan was untimely and extravagant, and it has been given little attention both in the history of the Alfonsín administration and in studies on urban plans, projects and policies in the past few decades.

The article discusses perspectives that, on the one hand, attempt to overlook the initiative or cast it as irrelevant, and on the other, portray it as out of place, untimely and absurd. In doing so, we aim to demonstrate how this plan – with all its ambitions and contradictions – serves as a key to making this complex period in Argentine history, marked by multiple shifts and transitions, more intelligible.

In technical terms, from its very conception the proposal was hybrid in nature, encompassing concerns, modes of intervention, diagnoses and solutions that aligned with developmentalist planning principles, articulating them with objectives that were innovative for the time, such as decentralization, state modernization, participation, environmental concern and the role of private actors in the construction of the new city. It is precisely in this eclectic combination of perspectives that the plan reveals a significant juncture, a moment of transformation in technical sensibilities regarding the role of the state, modes of intervention and conceptions of what was desirable and feasible in territorial and urban planning.

In political terms, the proposal also embodies the contradictions and tensions of the period, as the new administration’s re-foundational aspirations collided with severe political, economic and social constraints. The fervour of the foundational moment in which anything seemed possible gave way to a sense of surrender and resignation. This moment, then, marked a shift in expectations surrounding democracy and its possibilities. The plan’s ultimate failure stood in stark contrast to its ambitious objectives and the efforts put into the detailed studies carried out at the time.

Taking into account both its technical and political dimensions, the relocation plan reflects the faith that the Alfonsín administration placed in intellectuals, technicians and scientists to solve the complex problems that it faced. It also reveals the underlying rationales of technicians as well as their use of political arguments in certain contexts.

The case of the capital relocation shows how these technical and political shifts and reformulations intersect with the notion of ‘democratic transition’. This concept was central to this period in Latin American history, as it served not only as an explanatory key, but also functioned as a normative discourse, a horizon of expectations, a model of reality and a political slogan.Footnote 3 The uses of the notion of democratic transition in many cases eclipsed other transitions that were also taking place: changes in the views on the role of the state, the ways in which it intervenes in the economy and other aspects of social life, and disciplinary and intellectual shifts. These multiple transitions did not follow a single rhythm, but rather unfolded through varying dynamics and tempos, interacting in a number of ways – sometimes legitimizing one another, and at other times delaying, blocking or disrupting each other’s effects.

In this article, we reconstruct several dimensions of this process through the analysis of documentary sources, speeches, memoirs, news articles, legislative debates, plans and interviews with former government officials. The remainder of the text is divided into five sections. The next section considers previous studies that have analysed the project in order to demonstrate a noteworthy absence of the relocation plan in two fields of inquiry, namely research on the Alfonsín administration and on the urban plans, projects and interventions of the past few decades. The three subsequent sections explore different dimensions of the relocation plan. First, we consider the political dimension, examining the arguments put forward to justify the initiative in the context of emerging democracy. Second, we consider the technical dimension, in which we analyse the eclectic nature of the measure, which drew on various traditions of urban and territorial intervention. Lastly, a third dimension considers how these technical and political considerations intertwine. The final section offers some reflections on the case and the themes that emerged from our analysis.

A noteworthy absence

The notions of ‘crisis’ and ‘democratic transition’ have been central to interpretations of the 1980s in Latin America – functioning as critical concepts, descriptive categories and political slogansFootnote 4 – and have resulted in comprehensive interpretative frameworks that have emphasized certain periodizations, events and research topics, while obscuring others.Footnote 5

In Argentina, studies on the Alfonsín presidency have mainly focused on economic policy, political challenges of the democratic transition and the difficulties and frustrations faced by the Radical Civic Union’s (UCR) administration.Footnote 6 Some analyses tend to stress the confrontational nature of the former president as well as his failure to meet the public’s expectations. Others highlight power struggles that stifled the government’s efforts, portraying the administration as besieged and weakened. Although the plan to relocate the capital city has been given little to no attention in these assessments, it reveals another facet of Alfonsín: his strong propositional and re-foundational will, not only during his presidential campaign coloured by the ‘optimism of the foundational moment’,Footnote 7 but halfway into his term in office, when many studies focus on his defeats at the hands of powerful pressure groups.

This topic has been similarly absent from historical analyses of policies, plans and projects for the city, which have mainly focused on urban crises and novel perspectives that came to dominate urbanism and planning.Footnote 8 Later mentions of the plan typically dismiss it as absurd and untimely.Footnote 9 However, many of the most prominent architects, urbanists and planners of the time were actively engaged in this initiative, despite having previously criticized such plans, largely subscribing to the new intervention strategies of the 1980s. The ‘exceptional employment supply and professional expression’Footnote 10 that the project represented, as well as the commitment to the first democratic government in office after a long-standing dictatorship, served as incentives in a context of economic crisis. Therefore, the plan provides an alternative vantage point from which to assess the role of technicians and professionals as well as the state of debates within fields related to the production of the city.

The exclusion of this initiative from research agendas in these fields is telling. It raises questions about what the case of the capital relocation reveals that does not fit prevailing narratives in these fields, and what interpretative tools the plan provides in order to understand the transitions taking place during this period.

While there are some studies that emerged alongside the initiative, they usually took a stance on the relocation through the lens of different disciplines, assessing the alternative locations to the city of Buenos Aires and the potential for success of such an endeavour, as well as the historical precedents and motives behind it.Footnote 11 In other words, at the time, these works contributed to arguments both in favour of and against the relocation.Footnote 12

There are also later works that analyse the proposal based on specific issues, including views on Patagonia, the challenges faced by the proposal and the political significance of the Second Republic under the Alfonsín administration.Footnote 13

In this article, we take the relocation project as a lens to interpret the period in several ways. On one hand, it is a reflection of broader changes taking place at the time, regarding technical sensibilities concerning the ways of thinking about and intervening in the city, the role of the state and understandings of the country’s main problems (and potential solutions). It also offers insight into a time characterized by the co-existence of ‘excessive optimism’Footnote 14 about the possibilities of democracy and disillusionment over the strength displayed by pressure groups. This contradiction is evidenced through the failed relocation project, where re-foundational ambition gave way to non-implementation. On the other hand, the initiative sheds light on another issue prominent in the decade: the relations between technicians and politics. The UCR administration was frequently cast as being excessively technocratic, elitist or managerial in its exercise of power, with a top-down policy approach that placed technicians in a privileged position. These critiques are particularly salient in relation to the relocation plan, with its ambitious reach, the dominant role given to technical committees and the closed, centralized decision-making processes that characterized it.

Other case-studies of projects in other countries to relocate national capitals and create cities from the ground up provide useful tools and insights for analysing the case of Viedma.Footnote 15 It is telling that the 1986 relocation project does not neatly fit into a single category with any of these other cases; not the relocation or city-building projects that sought to reinforce the nation-state in the post-colonial era, nor the creation of cities from the ground up in order to have them operate as regional growth hubs, nor the more recent modelling of cities with an ‘entrepreneurial’ focus based on collaboration between public and private actors.Footnote 16 Although it bore some resemblance to the first two models, as we will discuss below, this was a more eclectic project that combined heterogeneous objectives and methodologies.

The time for politics: political will and excessive optimism

The start of the Alfonsín administration ushered in the return of democracy after seven years of dictatorship. Alfonsín’s discursive strategy aimed at establishing a clear counterpoint with the outgoing authoritarian regime and raising expectations for democracy. One of his most well-known electoral slogans reflects this mood: ‘In a democracy you can eat, cure and educate’. In this regard, a sense of ‘excessive optimism’ imbued with re-foundational spirit was constructed. As political and cultural repression diminished, a democratic spring took root, along with a feeling that anything was possible. By late 1985, Alfonsín was halfway through his term in office, and expectations were still running high despite some initial defeats. However, it was not until December of that year that he began emphasizing the need for constitutional reform and a deep transformation of the Republic.

At this juncture, in April 1986, Alfonsín announced the plan to relocate the federal capital to Viedma in a nationwide television and radio address.Footnote 17 The address took on an epic tone, calling on the people to ‘reinvent our very being’, conquer the south and re-found the nation. This was meant to catalyse a series of profound changes in Argentina’s developmental framework, emphasizing political will as a key for change. But above all, it aimed to rekindle public enthusiasm over the possibilities offered by an emerging democracy.

As shown in Figure 1, the chosen site lies at the gateway to the Patagonia region. The location initially proposed by Alfonsín encompassed only the city of Viedma in the Province of Río Negro, on the southern banks of the river of the same name. However, technicians suggested expanding the site to include the smaller city of Carmen de Patagones just across the river, belonging to the Province of Buenos Aires. The president accepted this suggestion, and so the new capital was to be located at the point of transition between the Pampas and Patagonia regions.

Figure 1. Map of South America. Argentina, Buenos Aires, Viedma and Patagonia are highlighted.

The speech announcing the project also addressed a series of ‘big problems’ rooted in Argentina’s history, interweaving them with multiple diagnoses, solutions and objectives. For analytical purposes, we have identified three main points, which in turn have multiple aspects and a great deal of overlap between them.

The first of these problems was the uncontrolled growth of the Buenos Aires metropolitan area.Footnote 18 This alluded to the long-standing image of a ravenous metropolis consuming the resources of the entire nation and creating an imbalance between the different regions of the country. In this view, the hypertrophy of Buenos Aires was inversely proportional to the underdevelopment of the rest of the country. Therefore, the proposal to relocate the capital sought to reduce the concentration of functions in Buenos Aires while promoting the development of the south in pursuit of greater geographical and economic balance. The new capital was to be a medium-sized city with largely administrative functions, in contrast to the megalopolis that Buenos Aires had become.

These economic, developmental and resource imbalances also translated into politics. According to Alfonsín, geographical centralism was consistent with the political centralism typical of authoritarianism. To combat this, Alfonsín advocated for federal decentralization, considering it to be more democratic.

A second group of arguments and objectives focused on Patagonia. This region was portrayed as abandoned, filled with unexploited wealth, an unfulfilled destiny. It was also depicted as a vulnerable region, exposed to the greed of neighbouring countries and major powers, evidenced by international conflicts Argentina had endured just a few years earlier, such as the Malvinas (Falklands) war with Great Britain in 1982 and the Beagle conflict with Chile. Alfonsín’s proposal – again, marking a departure from the country’s authoritarian past – involved carrying out a civilian conquest of Patagonia, leading to the expansion and growth of the region.

Combining these first two lines of argument to justify the location chosen by the president, numerous maps and charts were presented to illustrate the levels of economic, population and transport concentration around Buenos Aires, in contrast to the ‘emptiness’ of Patagonia, as shown in Figure 2.Footnote 19

Figure 2. Maps plotting economic concentration (on the right) and population concentration (on the left). They were intended to serve as an argumentative support to justify relocation.

Source: ENTECAP, ‘Los condicionantes que avalan el traslado de la capital federal’, Summa magazine, 253 (September 1988), 56.

A third group of arguments was related to state reform. The state was conceived as hyper-centralized, detached from citizens, vertical, bureaucratic and inefficient. The relocation of the capital would help solve this problem through decentralization, which in turn would drive public engagement by bringing the centres of power closer to citizens, and would also prove to be more effective thanks to the modernization of the capital through new technologies. The new location also meant escaping from the economic and social pressures of the big city, finding a neutral space.

All of these arguments must be taken into account in order to understand the plan for relocation. The plan was portrayed as the solution to long-standing national problems, driven by the expectations raised by an emerging democracy.

However, this ambitious proposal co-existed with discourses emphasizing austerity and feasibility. The relocation plan could not eschew such ambiguity. Even while proclaiming the conquest of ‘the south, the sea, and the cold’, the administration reassured the people of the austerity of their proposal: ‘We do not intend to promote the construction of a new Brasília. Our intention is to be austere, but let us recall that our country spent significantly more on the war in Malvinas.’Footnote 20 Again, a counterpoint to the dictatorship had to be established, not only through the notion of a peaceful conquest through development – rather than a military one – but also through austere policies, in contrast to the expensive initiatives carried out by the military government.

Brasília also functioned as a counterpoint because it was a lavish city, built from the ground up at great cost. The international model mentioned by the government was Bonn, a pre-existing, medium-sized city that austerely absorbed the functions of a national capital. Emphasis on austerity was key in a context where the country was facing an economic crisis and high external debt.

The early stages of the project – what we think of as a ‘time of politics’ – was thus characterized by a grand vision and ambitious goals. The starting point was an assessment of the country’s main problems, which relied heavily on old common-sense myths:Footnote 21 the idea of an excessively centralized country, a metropolis growing out of control and an empty Patagonia coveted by foreign powers.

We argue that in this early political stage, the discursive construction of the initiative was based on a series of boundaries and counterpoints. First, by providing a counterpoint to the dictatorship, through the notion of a ‘civilian conquest’ of the south, rather than a military strategy. The administration sought to build a more federal, democratic country – departing from the centralist tradition – all while emphasizing austerity, in contrast to the expensive, non-transparent endeavours of the previous administration. Counterpoints were also provided with respect to Faustian relocation initiatives carried out by other countries and Buenos Aires as a megalopolis that was out of control. These issues will be addressed in the following section.

Surveys carried out at the time indicated initial public support.Footnote 22 The political opposition pointed to the untimeliness of the decision, the lack of debate and its high cost in the midst of an economic crisis. Their main criticisms were that the proposal did not address the country’s most urgent problems and that it was a manoeuvre designed to divert the public’s attention. Later, when the initiative was debated in the Senate, technical arguments were brought up against the location, financing and closed, top-down decision-making process.

The tale of the relocation project illustrates the aforementioned transition from excessive optimism in the early years of the UCR administration – where anything seemed possible under democracy – to the disillusionment over its broken promises and battles lost against entrenched interest groups that hindered change.

The time for technical knowledge: technicians in power and co-existing perspectives

Political negotiations over the law that would need to be passed in order to implement the plan dragged on in the Argentine House of Representatives and the Senate for over a year after its initial announcement. During this time, the plan lost its place on the front pages of the press, but it was becoming increasingly refined by the technical committee entrusted with its development. Initially called the Technical Advisory Committee (CTA, from its Spanish acronym), it would later be known as the Agency for the Construction of a New Capital (ENTECAP, from its Spanish acronym).Footnote 23

Following the president’s guidelines, the CTA carried out countless studies and plans for what was to become the new capital, solidifying the initial proposals. However, the CTA was accused of operating in a secretive and discretionary fashion, a criticism later levied at the ENTECAP. Few formal announcements were made throughout 1986. Although a few roundtables were held at professional architectural associations and research centres for urban and territorial studies, it was not until mid-1987 (a year after the initiative was announced) that the ENTECAP began to publish studies and give updates to the public on progress made. Even then, this was mainly done in the technical sphere, often in specialized publications.Footnote 24

As these studies progressed and the design of the new city took shape, the co-existence of diverse traditions became evident in the specific ways the project articulated diagnoses, modes of intervention, objectives and aspirations. Furthermore, initial ideas began to shift as they materialized in maps, plans and projections.

First of all, this initiative represented a return to the central role of the state, playing an epic role in, among other things, addressing regional imbalances and promoting the development of disadvantaged regions through physical interventions and long-term plans. The state was seen as the central actor tasked with fixing the country’s major problems, even though it often relied on outdated assessments of them.Footnote 25 The search for social and spatial balance constituted a ‘long-standing utopian vision’.Footnote 26 The portrayal of Patagonia as a vulnerable region with untapped energy potential in need of state-led development was also a widely held view throughout the twentieth century.Footnote 27 Furthermore, the creation of an interdisciplinary committee of experts with public funding that was tasked with rigorously planning the intervention also followed a method of intervention typical of previous periods. Based on the idea that it would create a new epicentre of urban development that could lead regional development, the outlined ‘solution’ of relocating the capital was closely related to the theory of growth hubs, a popular approach in regional planning in earlier decades.Footnote 28

The central role of the state, the diagnoses used as premises, the methods of intervention and the proposed ‘solution’ all clearly aligned with modern planning precepts under a developmentalist framework. However, other features of the initiative hinted at its more eclectic nature.Footnote 29

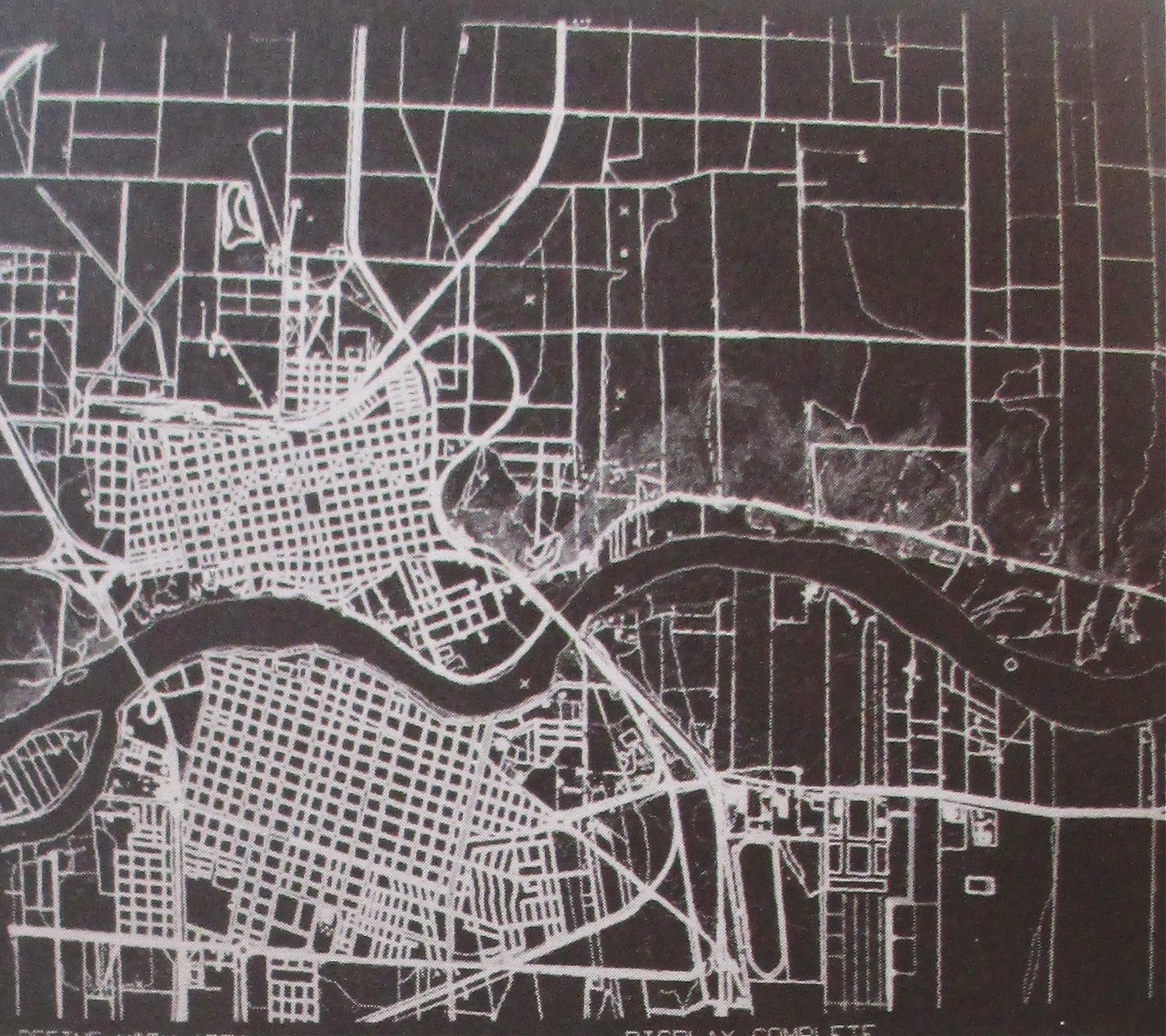

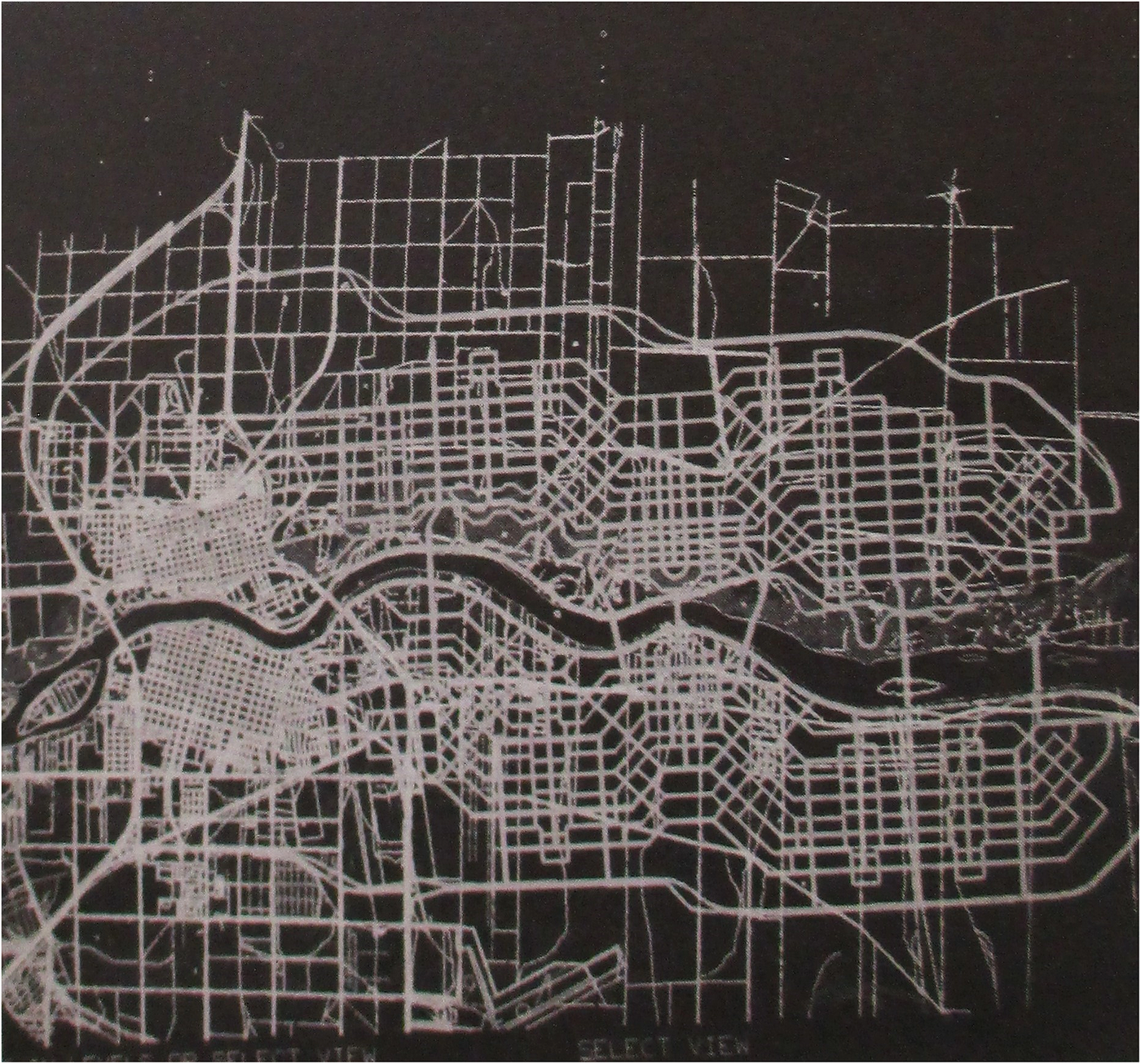

Following the principle of austerity, the new capital was initially conceived of as the development of new functions for a small, existing city. Later, the location was changed to a site farther from the urban core, a rural area adjacent to the towns of Viedma and Carmen de Patagones. Thus, the new development would have to be created from the ground up, mainly consisting of government buildings and international hotels. The urban grid, bridges and buildings would be new constructions whose design would be more focused on following presidential directives and reinforcing the symbolic dimension of the new city than on building on what was already there. The design strongly emphasized the need to incorporate the existing landscape, with the Río Negro playing a prominent role. This would be accomplished through the construction of nine bridges and a ‘wavy’ grid system intended to mitigate strong Patagonian winds. This design, however, was at odds with the existing city and its classic checkerboard design.

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate these issues. The first map displays the cities of Viedma and Carmen de Patagones in 1986, and the second shows the projected capital. The plans clearly show that the chosen location differed from the existing urban centre. Also, the layout of the new capital differed greatly from the previous layout, featuring larger blocks with a ‘wavy’ design following the course of the Río Negro. The Río Negro became the centrepiece of the design, causing an undulating layout enhanced by the new bridges that were to cross it.

Figure 3. Map of Viedma and Carmen de Patagones.

Source: ENTECAP, ‘Desarrollo del Sistema DAC Urbana II para el diseño de la nueva Capital Federal’, Summa magazine, 245/6 (January–February 1988), 105.

Figure 4. Projection of the new capital.

Source: ENTECAP, ‘Desarrollo del Sistema DAC Urbana II para el diseño de la nueva Capital Federal’, Summa magazine, 245/6 (January–February 1988), 105.

As shown in Figure 5, the central area of the new capital was designed to concentrate government buildings: the executive and judicial branches on one bank of the river, and the parliament on the other. These areas would be directly connected by a pedestrian bridge, aligned with the city’s central axis. On both sides, there would also be vehicular bridges, outlining a government district.

Figure 5. Map of the new capital. References that appear on the plan: 1. Executive and judicial area; 2. Legislative power; 3. Cathedral centre; 4. Railway terminal; 5. Port embarcadero; 6. University city; 7. New hospital; 8. International airport.

Source: G. Àlvarez Guerrero, Viedma (Buenos Aires, 2015).

This design reflected several key elements. As mentioned, the new capital was to be built from the ground up, with an urban grid system completely independent from the pre-existing layout in the neighbouring cities of Viedma and Carmen de Patagones. Both the size of the blocks and the ‘wavy’ street grid did not align with the existing city. The area designated for government buildings would be concentrated in the central area, flanked by bridges carrying strong symbolic meaning, with buildings representing the different branches of government facing each other on both banks of the Río Negro. While these features appear to reflect modernist precepts, other elements align more closely with postmodernism. First and foremost, the emphasis on integrating the existing landscape as a central part of the design. Specifically, the decision to organize the urban layout around the Río Negro reflects this concern. The intended mid-sized scale of the city was designed to create a more human-centred environment, rather than a monumental one. This approach was also evident in the inclusion of a pedestrian bridge that would serve as a connection between the two government buildings. Furthermore, although the plan indicated which functions would be permitted in each sector of the city, a co-ordinated mix of functions was sought rather than an emphasis on strict zoning.

The case of Palmas, planned in 1989, is particularly interesting to reflect on the Argentinian capital relocation project.Footnote 30 Contextual factors such as the return to democracy, economic crisis and the rise of postmodernist critiques of modernist planning are strikingly similar in both cases. Although, as Renato Leão Rego points out, the design of Palmas incorporated some modern elements alongside postmodern concerns, and therefore remains more strongly rooted in modernist principles than the design of Viedma, which favoured a smaller-scale approach, a flexible layout and an emphasis on austerity over monumentalism. The goal was ‘a return to peaceful, bucolic cities’.Footnote 31 While Brasília continued to provide inspiration for the design of Palmas, in the Argentinian context it came to symbolize excess, monumentalism, extravagance and dehumanized design.

The reference to Bonn was political, relating to the city’s scale and administrative function, rather than its design. It also kept focus on the transfer of functions rather than the construction of a new city. The ENTECAP technicians did not point to any specific model in terms of city design, but instead emphasized the desire to implement a harmonious intervention in line with the existing landscape.Footnote 32

Although the relocation proposal took elements from developmentalist views, its detractors would describe it as ‘factory-free developmentalism’.Footnote 33 The new city was envisioned as a medium-sized administrative town. Technicians were particularly concerned with avoiding the issues that, in their view, had degraded Buenos Aires: pollution, manufacturing and uncontrolled growth. As in other cases, establishing points of contrast with existing cities was a key argument supporting the design.Footnote 34

Plans for the new capital showed a strong concern for environmental issues. Proposals included tramways as means of transportation, as well as a green belt around the urban centre and tourism infrastructure in the areas surrounding the capital that would protect rivers and coastal areas while preserving the region’s original landscape. The ENTECAP technicians suggested creating an industrial hub, provided it were located outside of the city. According to Aldo Neri, who led the committee to develop Patagonia, ‘the new federal capital will not be an industrial city but an administrative one. We will attempt to avoid a manufacturing belt like the one currently surrounding Buenos Aires. Industrialization will be left for the rest of Patagonia.’Footnote 35

Technicians also discussed the need for a value capture law, enabling the ENTECAP to capture increases in land prices (initially classified as rural land) resulting from the relocation announcement. There was repeated mention of involving the private sector, as technicians and politicians sought to move away from the image of a purely public, costly and state-centred intervention.Footnote 36

Concerns about environmental issues, tourism, private sector involvement, architectural and historical heritage and the proposal of a mid-sized administrative city all reflect emerging topics of the 1980s. Some of these concerns were also associated with certain fears, particularly that of uncontrolled growth – the image of a massive settlement populated by low-income sectors in the city – a problem technicians observed in Buenos Aires, but also in other relocation experiences such as Brasília.

The contrast with Brasília was stressed at many levels, especially regarding the project’s intended austerity, crucial in a context of economic crisis and foreign debt squeeze.Footnote 37 Nonetheless, there were similarities, such as the fantasy of a ‘neutral’ land far away from economic and political pressure and powerful interest groups (in the Argentine case, the port of Buenos Aires above all, and in the Brazilian case, the economic power concentrated in Sao Paulo).Footnote 38

The emphasis placed on creating a medium-sized city was also linked to an anti-metropolis bent present in the plans for the new capital. Alfonsín envisioned a city where people would ‘know the colour of their neighbour’s eyes’.Footnote 39 Echoing this, technicians from the ENTECAP highlighted the importance of a medium-sized city in order to preserve human values: ‘Large-scale urban concentration around the city of Buenos Aires has gradually distorted the nature of social co-existence. It has increased crime rates and has blurred family organization. Districts featuring a more adequate human scale will restore lost values and achieve more harmonic ways of living.’Footnote 40 Thus, a mid-sized city was thought to ensure economic austerity and social harmony, as well as a more suitable environment to perform government duties. There was an idealization of the project’s potential ‘for shaping a new social order through urbanism and architecture’.Footnote 41

As noted in classic studies on the creation of capital cities, in environments built to harbour government buildings and capital cities, certain values espoused by the government may be noted.Footnote 42 In this case, the core values of the Alfonsín administration were austerity, medium scale (intended to represent engagement and decentralization) and the creation of a harmonic, face-to-face environment that would stand in contrast to state bureaucratization.

In sum, certain objectives and concerns that had started to take shape as the project moved forward could be regarded as ‘innovative’ in terms of territorial and urban interventions, such as the intent to develop a mid-sized, austere capital in an already existing city, taking into account environmental issues and heritage concerns, all while fostering sustainable industries such as tourism.Footnote 43 Nevertheless, other features of the initiative seem to have taken inspiration from previous traditions: state-centred decision-making, an assessment of territorial imbalances and the need to remedy them, views on Patagonia and the fact that the ‘solution’ to these problems was the creation of a new city as a starting point for development in the south.

The co-existence of several paradigms of intervention, as well as the diverse views on the role of the state, leads us to characterize this period as an ‘epistemological transition’.Footnote 44 This co-existence of perspectives, diagnoses and modes of intervention in the same project was not an anomaly, but rather indicative of the state of debates both in technical circles and within the Alfonsín administration itself, where all of these perspectives coalesced.

As evidenced by research on different Latin American and Spanish cities, far from straightforward transitions from one paradigm to another, combination, overlapping and co-existence of different perspectives are common in plans, projects and instruments of urban intervention.Footnote 45 Due to their long time frames, as well as the need to overcome obstacles, secure funding and build political consensus, plans and projects often bring several traditions together, and as such ‘pure’ plans drawing on a single tradition are rare, whereas mixed and overlapping perspectives are more common.

Lastly, this co-existence of views reinforces the image of democratic transition as a context that was ‘open and changing, filled with a plurality of voices disputing meanings and uses’.Footnote 46 Far from being a streamlined, orderly transition between political regimes, the context gave way to multiple debates that enabled discussions about relocation.

Between technical and political matters

Upon the announcement of the plan, Alfonsín created the CTA and appointed three architects with extensive planning experience: Jose Bacigalupo, Jorge Riopedre and Francisco García Vázquez.Footnote 47 They quickly assembled a large technical team that included architects, engineers, lawyers, accountants and other professionals. The CTA was to provide technical and urban planning advice on all matters related to the relocation, such as site selection, preparation of an urban plan and the repurposing of Buenos Aires. These tasks were later inherited by the ENTECAP. The CTA/ENTECAP was given full power to plan and execute projects, grant concessions and land use permits, propose expropriations, request loans, manage financial operations and conduct studies.Footnote 48

Paradoxically, the CTA’s first task was to justify the chosen location. From a technical standpoint, although the choice of location was to result from several assessments based on a variety of indicators, in this case the technical grounds were an afterthought, providing a scientific framework to the president’s ‘hunch’.

The CTA/ENTECAP carried out a number of studies on the chosen location and environmental analyses that assessed wind, sunlight, rainfall, vegetation and other factors relevant to the city’s design. The most cutting-edge urban and architectural design software were utilized, along with databases enabling complex population and demographic projections. The use of new technologies in this process was widely publicized, serving as an example of what the reformed public administration would look like once the relocation took place.

At least three interesting features of the ENTECAP experience can be highlighted, which have also been noted in other urban planning processes.

First, there is an emphasis on providing a scientific, quantifiable and measurable approach to a complex social problem, at times ignoring its inherently political nature.Footnote 49 While the decisions to move the capital and the choice of location were discretionary decisions made by Alfonsín, they were supported by scientific evidence based on interdisciplinary studies and a vast array of indicators. Population projections and the use of new technologies to generate numerical data were intended to add certainty and legitimacy to what were, in reality, political decisions.

Second, it is telling that there was a nearly inverse relationship between the large number of studies and projections carried out on one hand, and the lack of implementation on the other. The few public works that were actually carried out were limited to small infrastructure projects, largely driven by the demands and pressures from local mayors, along with some housing developments for those who would build the new capital, driven by fears of a potential influx of low-income residents.Footnote 50 None of these projects resulted from the work of the ENTECAP, which instead focused on producing thorough interdisciplinary studies involving top-level architects. The few projects that were actually implemented were thus the result of political needs ‘pulling’ the technical logic of study production.

Third, it is important to take into account the timing of technical and political processes. This proliferation of studies, projections and plans – as well as the prevalence of a technical discourse – expended at the exact moment when the necessary political conditions to carry out the relocation were dissolving, as the Alfonsín administration had lost the political sway it needed to push the initiative forward.

While goals of ‘state reform’ seemed to be the most ‘innovative’ and in line with new views on the role of the state and its modes of intervention, they also exerted the most pressure on the way in which the relocation plan was managed. The point was to decentralize, drive engagement and make public administration more efficient. These three issues were considered to be related: decentralization was connected with the democratic process, as opposed to authoritarian centralism.

However, critics at the time pointed out several issues concerning not only government practices, but also the way in which the CTA/ENTECAP was run. Despite the objectives of decentralizing and driving engagement, the decision-making process was completely centralized and hierarchical. As in other experiences, decentralization discourses co-existed with hyper-centralized practices.Footnote 51 The CTA/ENTECAP was harshly criticized both for the discretionary mechanisms through which its members were selected and the secrecy surrounding the relocation itself. Any progress made was rarely publicized and forums for public dialogue were scarce. It was not until very far along in the process – May 1987, when the initiative was losing strength and the Alfonsín administration had been weakened by the economic crisis and a number of other conflicts – that the ENTECAP systematically started sharing information in some architecture journals. Planners presented studies intending to cover the project from all angles, but they did so without the input from residents of either the future or former capital, or from most architectural professionals. While the architects responsible for the project emphasized the need for flexible planning that would facilitate more widespread, pluralistic and democratic participation, in reality the CTA acted in an insular fashion, and a range of professionals from architecture, planning, geography and related fields decried the absence of forums for participation.Footnote 52

The few public works actually carried out were awarded directly, without competitive bidding processes. Blueprints and designs were prepared by members of the CTA/ENTECAP with no prior debate. This way of doing things was harshly criticized by the Central Society of Architects, which in different public statements equated direct project awards with the practices carried out by authoritarian regimes.Footnote 53 This accusation was particularly significant given the efforts of both the president and CTA technicians to associate the relocation with democratization in direct contrast to the dictatorship.

The link between capital relocation and state reform featured another relevant dimension: the idea of ‘spatial discontinuity’ as a key to solve many of the state’s problems. The most qualified employees would be selected to be relocated to the new capital, creating a distance between the bureaucracy and elite public officials and politicians, separating politics from administration. The idea was to isolate the government from the bureaucracy, economic pressures and the hustle of the big city.Footnote 54 It was thought that this spatial discontinuity would carry over directly into a disruption of bad practices, and the use of state-of-the-art technology in the new capital would automatically increase effectiveness.

This viewpoint was criticized for being naive and spatially deterministic, as complex political and social problems were being addressed with spatial arrangement and new technologies. As one journalist at the time ironically quipped, ‘architects are going to have the final say in state reform’.Footnote 55

Although the involvement of technicians is a constant in this type of project – as in all major urban interventions in Argentina – some interesting particularities emerge from this case.

The search for technical solutions to political issues seems to be rather salient under the Alfonsín administration, primarily because of the strong confidence the president placed in intellectuals, technicians and professionals. In the case of the relocation, after a first political stage where the president set an epic tone for the initiative, far-reaching powers were given to the CTA to move forward with the plan. While the project was extensively discussed in the House of Representatives and Senate, the development and materialization of images and ideas that could engage the population were left in the hands of the ENTECAP, as these were considered technical issues.

The UCR administration gave great importance to the technical, scientific and rational basis of the relocation, in contrast to other periods when technicians were not given a such a prominent role. This more prominent role also resulted in an ‘overconfidence’ on the part of some technicians in their ability to solve complex, long-standing problems. The CTA/ENTECAP was harshly criticized for its closed-minded and technocratic approach. Although its technicians were considered qualified by the majority of professionals working on the issue, the selection process, secrecy and lack of public participation jeopardized the success of the initiative from the perspective of many professionals who were concerned about the problems that could result from a city built quickly by just a few hands. Some professionals pointed to the naivety of planning the relocation and the new capital behind closed doors, ignoring both the reality of the social and economic dynamics that form cities, and the fact that idealistic plans are often shelved.

This also relates to another aspect of this period that is often criticized: the search for broader rights and a stronger democracy ‘from the top down’ instead of being rooted in social demands. As one analyst put it: ‘Alfonsín…has always had a tendency to consider rights “from the top down”. That is, he has always enshrined those rights on the basis of teams of experts with sophisticated educations and progressive inclinations.’ Thus, Alfonsín has been portrayed as being ‘at the forefront’ of a society that was ‘falling behind’.Footnote 56 In the specific case of the relocation, the president proposed the initiative and chose the location without allowing for challenges or criticisms. Later on, the ENTECAP developed a closed-door working dynamic, as a sort of enlightened vanguard detached from both the city where the new capital would be located and the public in general. The goal was to ‘offer the future residents of the new capital the best city that Argentine technicians are capable of making’.Footnote 57 However, the lack of an open forum where the public at large and other professionals could participate considerably restricted any possible consensus on what the new capital should be like.

Both technical and political expectations were invested in the new capital. For technicians, the new capital was meant to be a show of what they could accomplish as a discipline, both in the use of new technologies and the creation of symbolically charged space through emblematic architectural interventions. For the president, the new capital was meant to demonstrate his ability to transform the nation’s destiny through sheer political will. In both cases, it was a transformation from the top down.

After launching the initiative and ensuring its progress on both the legislative and technical fronts, the administration found itself heavily burdened by other issues that it considered more pressing. Military uprisings, the failure of its economic plan, the 1987 legislative defeat and the acceleration of inflation to the point of hyperinflation in 1989 completely displaced the relocation project from the public agenda and from the government’s programme. Although it got off to a relatively promising start, the project did not manage to generate sustained enthusiasm in the population or to engage the political sphere. After initial interest, as months passed, the initiative began to be seen as unrealistic and disconnected from problems considered more pressing. The few images of the plan for the new capital that circulated also failed to take root in the social imaginary. The project faded away without much fanfare, alongside the decline of the government itself.

Conclusion

The capital relocation plan was central to the re-foundational ambitions of the Alfonsín administration. However, this centrality has not been evident in later analyses, which have often disregarded or underestimated the initiative. Our analysis of this project has sought to reconstruct pathways that were considered possible, desirable or even inevitable at the time, even though they never materialized. Far from representing a weakened, besieged government, halfway through Alfonsín’s term in office this initiative projected the image of an ambitious president with re-foundational aspirations. Contrary to the views that have criticized the project considering it irrelevant, untimely or absurd, we posit that the project – with all its ambitions and contradictions – helps us understand a period marked by multiple technical and political transitions.

This case sheds light on the period of emerging democracy as an open, contingent and conflictual context, and on the transition juncture as a process of political and intellectual debate.Footnote 58 The return of democracy brought with it a strong sense of optimism and the feeling, held by a large portion of the population, that anything was possible. As notions of participation and decentralization became more strongly associated with democratization, certain views linked to developmentalism and expectations over the central role of the state lingered on, all in the midst of an economic crisis. The project, therefore, condenses this mix of re-foundational aspirations, expectations regarding decentralization and participation and austerity discourses. In its brief existence, the initiative also symbolized the passage from unrestricted optimism and endless possibilities under an emerging democracy to disappointment and resignation over a sense of impossibility to transform Argentina’s situation.

In technical terms, the project reveals the co-existence of different perspectives on how to think about and intervene in the city, combining diagnoses, modes of intervention and objectives from several traditions. Rather than representing a linear progression from one intervention paradigm to another, the project highlights the persistence of certain ideas co-existing with innovative purposes, seemingly without tensions, according to the technician’s perspective. Our findings are consistent with studies on other cities and intervention instruments where co-existence, overlapping and ‘mixtures’ of several paradigms can be observed, rather than automatic and orderly transitions between paradigms.

It is also interesting to note the different social imaginaries regarding the city that co-existed under the same project, and how they articulated with technical discourses following diverse political logics. On one hand, there was an anti-metropolis bias that blamed the city of Buenos Aires and its metropolitan area for many of the country’s ills, as well as the degradation of values, pollution, out-of-control growth, lower quality of life, and the prevalence of speculation over regulation. The idea of urban crisis informs this discourse. Narratives that supported the relocation of the capital were based on the widely held view that Buenos Aires was an unplanned, polluting city with uncontrolled growth, hypertrophic in relation to the rest of the country, and disconnected from its natural environment (e.g. it ‘turned its back on the river’).Footnote 59

The proposed solution to these problems was to build a medium-sized city that would be pleasant, sustainable, administrative and non-polluting, where neighbours would know one another. Some critics argued that the initiative’s true motive was to get far away from the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires and its manufacturing belt, historically associated with low-income sectors, Peronism and political demonstrations in Plaza de Mayo. A mid-sized, pleasant city would thus be a neutral territory where administrators could work in peace, away from the pressures of the big city. In this regard, the initiative was defined and built upon counterpoints with the dictatorship, the city of Buenos Aires, pressure groups and certain forms of political mobilization by low-income sectors.

On the other hand, some of the innovative objectives and approaches were modified over the course of the designing and planning of the new capital, representing a return to work processes typical of previous periods, such as flexible planning or notions of intervening in the existing city. As the process progressed, the CTA (and later the ENTECAP) ended up selecting an area and design that had little to do with the existing town, working in a closed-off manner as an expert committee detached from the population and other professionals.

Returning to some of the issues mentioned at the beginning of this article, this initiative emerged in a context of concurrent technical and political transitions that overlapped with the transition to democracy, which in turn acted as a defining category and political beacon of the time. Our analysis of the capital relocation project has also allowed us to challenge predominant narratives about Alfonsín’s presidency and its different stages, illustrating an ambitious and forthcoming nature, even halfway through his term in office. We have also intended to provide a different image about the state of debates in the sphere of technicians, experts and professionals related to the city. Far from being fully aligned with new perspectives, these debates were much more hybrid in nature. In this regard, by studying this case, our intent was to demonstrate that these processes were much less straightforward than believed, filled with uncertainty, complexity and debate.