Introduction

Guaranteeing urban food supply was one of the most fundamental duties of municipalities in the early modern period. Fear of scarcity and famine led councils to regulate supply and establish appropriate processes and distribution networks. Supply systems in Europe ranged from private monopoly models, fragmented supply involving small producers, direct supply by organizations to a variety of more liberalized systems. Regardless of type, these supply systems were, in general, quite ineffective and led to frequent food shortages. The lack of infrastructure is cited as one of the major reasons for this. Another potential weakness was unfettered speculation, at a period in history when prices could fluctuate wildly.Footnote 1

The intervention of states and municipalities fits into the context of a moral economy based on a defence of the common good and ‘equality’. Equality here does not mean that everyone received an equal share, but rather that their share was dictated by their social status. Supply, and particularly meat supply, reveals the differences among various social groups, with consumption patterns specific to each stratum.Footnote 2 While animal products in general – from dairy products for human consumption to leather for such varied activities as shoemaking or bookbinding – were crucial to the urban economy, meat held a special status.Footnote 3 It could be considered either an essential commodity or a luxury, depending on the type of meat concerned. Access to this form of nutrition could be difficult for the poorer segments of the population and some cuts of meat were allocated to the more privileged social groups.Footnote 4

The policy of the common good aimed at providing products at a fair price. In the case of meat, contradictions often arose within this policy, as prices were fixed to prevent increases, while simultaneously taxes might be imposed to generate more revenue. Ultimately, this inconsistent approach distorted the market and led to higher prices. The most disadvantaged levels of society were the most affected by these fiscal policies.Footnote 5 However, at the same time, this policy also created tensions with producers, because the fixed price might not necessarily reflect the operational costs of supply and thus limited potential profits.Footnote 6

This article aims to contribute to the discussion on urban and municipal supply by examining the systems developed to provide meat to the city of Coimbra from the seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries. The main focus will be on the roles played in the process by municipal councils and private suppliers. Because this period was characterized by economic self-sufficiency and there were significant barriers to market integration, primarily due to limited communication and transportation, municipal councils played a crucial role in feeding the urban population. Their goal was to ensure a steady supply of meat at a ‘fair price’, typically determined by local authorities, with a focus on protecting consumers from scarcity and the social instability this could cause.Footnote 7 Typically, municipalities engaged private entrepreneurs who did not hold municipal office and who were specifically contracted to supply certain products.Footnote 8 For essential foodstuffs, including bread and meat, it was common for authorities to exercise control and to intervene to ensure supply and maintain public order, particularly during times of crisis.Footnote 9 This in turn could create pressure for reduced state intervention and lead to tension between authorities and independent merchants,Footnote 10 as well as between authorities and merchants seeking greater operational freedom.Footnote 11

The municipal supply of Coimbra in the early modern period has been studied previously.Footnote 12 In the city of Coimbra, meat consumption by the general population has been documented from the Middle Ages; there was considerable social inequality when it came to access and consumption, and this continued throughout the early modern period.Footnote 13 The consumption of meat was important not only in Coimbra, but throughout the whole kingdom. A hypothetical Portuguese consumer basket, as proposed by Jaime Reis, included bread (maize or wheat), meat, wine, olive oil, eggs, chicken, charcoal, linen, cloth, soap and lamp oil.Footnote 14 Historians have also noted the existence of a supplier selection process based on auctions, but have established relatively few details as to how it operated. In this article, theoretical models from New Institutional Economics, including contract theory, agency theory and auction theory, will be applied to the issue of urban food supply in the early modern period. This analysis will also consider the evolution of real prices, as most historians do not deflate their series, which can undermine the validity of such studies.

For the purposes of this article, Coimbra provides a very illuminating example. Located inland, Coimbra faced different supply challenges to those of the more frequently researched coastal cities, which had access to maritime supply routes. The city is also more representative of the majority of municipalities across the country at this time, since it was smaller, with less strategic significance than Porto and Lisbon.Footnote 15 Larger cities, especially those with royal courts, had higher meat consumption and became central to supply policies, subsequently attracting significant attention from historians. However, it is also important to examine medium-sized cities, which better encapsulate the reality faced by most urban centres.Footnote 16 The focus in this article will be on a chronological period not explored in other works on the topic in Portugal, yet which can be supported by archival material such as contracts and price records. While some crucial sources are lacking, such as data on quantities sold and consumption, the extant material is still very varied, with the core comprising auction records, auction deeds and obligation contracts, all of which are held at the Municipal Historical Archive of Coimbra.Footnote 17

The central question posed by this article is: what was the impact of risk and transaction costs on the delegation of municipal supply responsibility to private contractors? Yet asking this question immediately opens other lines of enquiry: what impact did auctioning have on the selection process and on prices? How did meat prices evolve over time? Can this evolution be considered a ‘success’ in terms of the existing model preventing any great increase in the price of meat? To address these questions the article is divided into four sections. The first provides a brief context and literature review on the topic, with a greater focus on municipal supply mechanisms in Spain and Portugal, more specifically in Coimbra. The second section analyses the obligation contracts, particularly their clauses. The third focuses on the impact of auctions on the selection of contractors and contract prices. The fourth and final section examines meat supply, price and consumption evolution.

Municipal supply strategies in the Iberian Peninsula: regulation, monopolies and contracts

This section aims to provide an overview of the broader context of meat supply in Iberian towns, outlining the various strategies employed to ensure adequate provisioning, their evolution over time and the extent to which Coimbra followed or diverged from these patterns. By examining municipal interventions, contractual arrangements and market regulations across different regions, this discussion establishes a comparative framework that highlights both commonalities and local specificities. Understanding these mechanisms not only contextualizes Coimbra’s supply system but also sheds light on the wider economic and political dynamics that influenced provisioning practices in the early modern period.

Supply was a central concern for local authorities and was considered one of their primary duties. Consequently, they made significant efforts to organize and regulate supply, particularly when it came to prices.Footnote 18 The intervention of local authorities in this process was common throughout early modern Europe.Footnote 19 City councils continued to play a crucial role in provisioning urban communities until the emergence of liberal states in the nineteenth century and the consolidation of national markets, which not only reduced the powers of local authorities but also eliminated constraints on the circulation of products.Footnote 20 Fear of social unrest due to scarcity or famine led to strict controls over the supply of food, both by seeking to ensure adequate provision and the regulation of prices. However, many municipalities also viewed supply management as a means to generate additional revenue. In Spanish municipalities, as in other European kingdoms, local authorities pursued self-sufficiency and consumer protection. Municipal intervention encompassed provisioning, quality control, hygiene standards, inspection of weights and measures, price fixing and efforts to combat fraud.Footnote 21

The demographic and economic growth of the sixteenth century prompted municipalities to re-evaluate and restructure supply systems. In Coimbra, between 1580 and 1640, meat supply contracts were auctioned and awarded to those offering the best price and conditions under a monopoly arrangement. Contractors, the sole authorized sellers, often borrowed interest-free municipal funds to purchase cattle, repaying these at the contract’s end. Butchers typically paid transaction taxes (sisa) and a sixteenth-century consumption tax (imposição), although exemptions were sometimes negotiated. Privileges included grazing rights in city olive groves.Footnote 22 Meat supply contracts in Coimbra during this period typically lasted one year and required contractors to fulfil weekly quotas. Non-compliance led to fines, imprisonment or contract termination. Cattle were mainly sourced from Beira and Entre Douro e Minho, while sheep came from areas near Coimbra and Serra da Estrela. Municipal incentives, such as tax exemptions, loans and monopoly rights, aimed to ensure affordable meat prices. However, price controls and limited profits deterred competition, with some years lacking bidders and forcing the City Council to supply meat directly. This article analyses these dynamics through auction theory.Footnote 23

Observing other regions of Portugal, we can see some similarities and differences. Joaquim Romero Magalhães has studied the supply to cities in the Algarve (South Portugal) during the early modern period. He highlights the concern to keep the population abundantly supplied at a fair price to avoid famines and possible revolt. The availability of foodstuffs depended on suppliers who were motivated by the selling price, which could not be too low.Footnote 24 The meat was supplied by private contractors, with whom municipalities signed binding agreements that imposed maximum prices, so they could not sell freely.Footnote 25 Arrangements could differ between municipalities depending on how difficult it was to procure produce. For example, the city of Mirandela (northeast Portugal) was close to areas with abundant cattle production. Therefore, significant intervention was not necessary to ensure an acceptable meat supply. The cutting and selling of meat in butcher shops were also regulated by the municipality, which generally prevented butchers from operating outside the city.Footnote 26

In Porto from 1580–1640,Footnote 27 municipal policies balanced attracting suppliers through incentives (e.g. reduced taxes) with restrictive measures like price fixing and supply quotas, which prioritized consumer protection. Strategies included coercing intermediaries to accept lower prices while acknowledging producers’ ‘fair gain’. Public butcher shops, supplied via mandatory contracts, ensured affordable meat. Contracts, often lasting three to four years, included negotiations if the bidding base was unsatisfactory. Contractors received loans (e.g. 400,000 réis) and tax exemptions, but were bound to provide quality meat at fixed prices and in set quantities, and sell only at designated locations. They also reported staff details and complied with the city’s judge.Footnote 28 In the late eighteenth century (1780–1800), the supply of meat (beef, veal and mutton) was based on the same system, using private contractors, which attests to its longevity. There were three public butcher shops that ensured the sale of meat at fixed prices to the public. The contractor was chosen through an auction process, with the winner being the one who offered the meat at the lowest price. They were then tasked with supplying the city (usually for one year) with all the necessary meat.Footnote 29

In Spain, during the early modern period, municipalities often relied on private contractors, sometimes with monopolies, to supply essential goods through public auctions. This model was also adopted in Spanish American colonies. Contracts were signed with individuals, local or external, who agreed to provide specific products at fixed prices. The goal was to ensure abundant, high-quality supply at fair prices for both the population and contractors.Footnote 30 In the late eighteenth century in Alicante, the municipality employed private contractors, who monopolized meat supply through public auctions. Prices were fixed and contracts were competitive, reflecting the business’s profitability. Contractors, backed by guarantors, agreed to terms regulating both parties’ rights and obligations, including meat quality and sales restrictions, particularly on price increases. The contractor bore the risks and costs, such as staff employment and animal transportation.Footnote 31

In the municipality of Vitoria in Spain, in the first half of the eighteenth century, the supply of beef and mutton for the city’s butcher shops was a priority for the municipality. It was common practice to lend money to the contracted individuals to facilitate the purchase of meat. This had to be repaid at the end of the contract, without interest. Generally, the municipality preferred to use private contractors because they assumed responsibility for the expense of transporting and maintaining the animals until their slaughter date, as well as any mishaps and accidents that occurred.Footnote 32

Ramón Lanza Carda explores livestock farming in the Cantabrian Mountains (sixteenth–nineteenth centuries), noting how growth was constrained by technological stagnation and competition for land. Maize improved peasant self-sufficiency, reducing hardship, while smaller livestock facilitated crop rotation. Tensions arose as agricultural expansion threatened pastures. By the late eighteenth century, livestock farming had declined due to pasture scarcity and subsistence crises, exacerbated by natural disasters and military demands. Recovery began in response to rising demand for meat and cattle, spurred by population growth, urbanization and regional needs during the Carlist Wars. Access to public pasture and local support facilitated this revival.Footnote 33

Máximo Diago-Hernando emphasizes the role of privileges in livestock supply and the inequality between large and small producers. From the thirteenth to nineteenth centuries, transhumant cattle farming in Castile was supported by privileges from the Honrado Concejo de la Mesta, which granted preferential access to pasture and freedom of movement for livestock. However, these privileges benefited large landowners disproportionately, offering them social and political advantages, such as tax exemptions, that were unavailable to smaller herders. Large landowners secured the best lands, while small and medium herders faced higher costs and less favourable access to pasture.Footnote 34

Bernardos Sanz’s study of Madrid’s meat supply highlights a system managed by obligados through annual contracts that were designed to lower prices. However, control was monopolized by a small cadre of merchants, whose influence shaped policies that often disadvantaged poorer consumers, despite claims of affordability. Merchants’ dominance led to strict price controls and municipal interventions during supply crises, causing bankruptcies among the city’s butchers. Unlike bread, which was regulated directly by authorities, meat supply was managed privately, with authorities stepping in during shortages. Meat consumption reflected social disparity, with mutton reserved for the wealthy and cheaper meats for poorer classes. Urban demand prioritized cereal and wine cultivation, pushing livestock farming to distant regions. Improved transportation and commercial networks reduced reliance on nearby territories.Footnote 35

From 1630, Madrid’s municipal intervention in meat supply increased as the obligados system struggled amid a livestock crisis and fixed prices. Carnicerías (butcher shops) managed supply but faced challenges from unbalanced agricultural practices, fiscal pressures and reduced livestock due to the conversion of pastureland and peasant impoverishment. By the seventeenth century, declining supply and rising prices strained markets. Recovery in the eighteenth century, particularly in Extremadura, saw the expansion of cattle farming. Despite increased consumption in the 1670s, a subsistence crisis in the 1730s reversed these gains, prompting the Junta de Abastos to stabilize prices, though it dissolved after the 1766 riots.Footnote 36

By the early nineteenth century the inadequacies of the system in the face of population growth and weak supply mechanisms were becoming impossible to ignore. The 1802–04 crisis clearly demonstrated the need for modernized strategies to address market disintegration and rising demand.Footnote 37 These events also highlighted the failures of Madrid’s meat supply system, which had become strained by population growth and inadequate commercial infrastructure. The resulting food shortages, affecting meat and bread, exposed internal market disintegration and the inability to meet rising demand. The 1805 liberalization, a response to these challenges, marked the end of the ancien régime’s ponderous approach and underscored the need for modern supply management strategies to address the evolving economic and social landscape.Footnote 38

These various examples reveal that the development of supply systems showed more diversity in Spain, with cases of greater or lesser intervention, variations in the duration of contracts and the use of private entities (with and without monopolies). In Portugal, the supply was more uniform, although the evidence is less comprehensive. Coimbra’s model, based on auctioned monopoly contracts with municipal oversight, aligns with broader Iberian patterns but also reflects local adaptations to economic and logistical constraints, such as reliance on interest-free municipal loans to contractors and the provision of grazing rights.

Obligation contracts: structure and clauses

The corpus of sources under analysis includes the records of bids, awards and contracts of obligation. The first of these detail the registration of bids (prices) submitted at the auction – a competitive selection of suppliers (known as obrigados) where the lowest bidder secured the contract. The records of awards consist of the registration of the auction results and basic information about the contractor, the price and the duration of the service. Contracts of obligation were subsequently drawn up, containing information from the preceding documents, along with the obligations being undertaken by both parties and the details of guarantors and collateral. Because the contract of obligation contains the bulk of the pertinent information, along with the conditions of the agreement, it is usually the most valuable as a historical resource. In this section, three such contracts for the supply of beef will be analysed. Three samples are sufficient because, as will be seen, these contracts did not change significantly over time.

The first contract is dated 7 December 1631. It begins by recording the date and place of signing (the City Council clerk’s house) and the name of the contractor (Gaspar Francisco, resident in Coimbra). The period of supply is stipulated (one year until the Carnival of the following year) and the minimum quantity to be supplied (10 bulls or cows per week, males and females, more males than females, until St John’s Day and from this day onwards, 12 animals per week until Carnival). The price is also mentioned (13 réis per arrátel – equivalent to a pound or 0.459 kg – not including the value of the real de água tax on the consumption of meat and wine, with the final price being14 réis).Footnote 39 The contract also refers to a special clause (specifying that sirloin should be provided for the municipal officials every Saturday) and the amount loaned to the contractors (200,000 réis in total), underlining that this same amount should be returned at the end of the contract. In the event of non-repayment, the contractors were to be arrested and only released after the total amount was returned. If they failed to comply with the price or quantity of cattle to be supplied, they would be liable to pay a fine of 6,000 réis for each infringement.Footnote 40

The contractors were required to indicate the collateral (‘present and future assets’, usually properties) and guarantors to ‘secure’ the contract, specifically the repayment of the loan. In this case, the contractor presented his son, Francisco Marques, as a guarantor, stating that he would repay the money lent by the municipality to his father in the event of default. The guarantor also presented his own properties as collateral.Footnote 41 The assets listed had to be ‘free’, meaning they could not be pledged as collateral in other contracts. The document also states that the contractor waived all laws, privileges or exemptions in his favour, meaning any justifications he could present to exempt himself from complying with the contract’s terms. He agreed to be accountable to the authority of the judge or, in the absence of the former, any other municipal official as sources of authority for conflict resolution.Footnote 42

The second and third contracts, which were dated 16 May 1731 and 19 April 1789 respectively, were also signed at the Town Hall and follow the same structure. Therefore only the differences need be highlighted. The second contract stipulated that the meat should come from Minho or Caramulo (northwest Portugal) and should be supplied in abundance ‘every day from sunrise to sunset’, except on Thursdays. The loan totalled 500,000 réis (lent from the real de água tax vault, as the City Council lacked sufficient funds), so that the contractor could purchase cattle as soon as possible. The remaining clauses are identical to the previous contract.Footnote 43 The differences in the third contract compared to the previous two are relatively minor. It is noted that the contractor agreed to submit to inspections by the municipal senate (or an appointed commission) to examine the quality of the meat and reject any they deemed ‘unfit for sale’. Moreover, in the event of a shortage of meat, the council could revoke the contract at any time.Footnote 44

In general, the format of these contracts remained stable over time. An important aspect of analysing the contracts is that they are based on a principal-agent model. There is a principal (the municipality) that delegates to an agent (the contractor) the responsibility to provide a service (supply) for a certain period and within a specified geographical area. This process involves the delegation of responsibilities and privileges.Footnote 45 This particular principal-agent model has some characteristics that should be emphasized: the principal (the municipality) is risk-averse, while the agent (the contractor) is risk-neutral (an idea that will be considered further below); the agent’s effort is observable and reasonably easy to monitor (because the products were sold in specific places, i.e. the butchers’ shops); the principal could not avoid its obligations (i.e. the municipality could not avoid supplying the meat); the principal could perform the service, but chose not to; the supply of the product was variable, depending on the agent’s effort, but also on external forces, such as unforeseen crises.

The clauses of the contract reveal that the principal’s two main concerns were transaction costs and risk, the latter in balance with the incentive given to the agent. By delegating the responsibility for supply to private contractors, the municipality gave up responsibility for a service that required the creation of supply systems staffed by salaried officials. These individuals would buy the animals, then transport them live to Coimbra for later slaughter and sale. By delegating this service to the contractors, the municipality saved on administrative costs (salaries), transport and the expense of monitoring its employees – in other words, the private procurement system allowed for a significant reduction in transaction costs.Footnote 46 Risk was a major obstacle to the municipality fulfilling this task, particularly due to unpredictable events (crises such as adverse weather or climate conditions, epidemics or wars). When drawing up these contracts, the municipalities delegated responsibility to the agents, emphasizing that there was no justification for the latter not fulfilling the contract.Footnote 47 In this way, the contractor was compelled to comply, pressured by the possibility of being fined or, ultimately, imprisoned.

The contractor thus assumed the costs and risk that the municipality avoided. In order to induce them to accept the contract, the municipality offered various benefits and privileges, such as a monopoly regime, exemptions from consumption taxes, exemptions from taxes on the movement and grazing of animals, along with financial support in the form of loans. The agents accepted the contracts with the aim of making a profit, so all their actions were geared towards minimizing costs (transport, administration, etc.).Footnote 48 In other words, the service provided by the agents was more efficient than the municipality could arrange itself, and the same logic applied to contracts for collecting indirect taxes, for example.Footnote 49 The most important incentive, however, was the fact that the contractors were not subject to a limit on the quantity of meat they could supply, meaning they could maximize their profits by supplying more. Naturally this increased their commitment to the task and proved to be of benefit to the community, since in this particular situation their interests aligned: the more meat the agents supplied, the more money they earned and the more satisfied the people and the City Council became.Footnote 50

In order to reinforce the fulfilment of contracts, it was also common for the principal to use guarantee costs. These consisted of guarantees and guarantors who ensured payment (in this case, they guaranteed the loan given by the City Council) in the event of the contractor’s default or insolvency. The collateral pledged by the contractors and guarantors was real estate, registered and detailed in the contract. A well-executed insolvency meant that the result of the seizure and sale of assets would be the same as if the contract had been fulfilled.Footnote 51 In other words, the proceeds from the sale of the assets pledged as collateral was supposed to be equal to or greater than the amount lent by the municipality.

The municipality delegated the responsibility of supply to agents, avoiding transaction costs and the risk associated with the service, while the agent accepted the costs and risk, in hopes of securing a profit. For this reason, the municipality can be considered to be risk-averse and the agent to be risk-neutral.

The auction and the selection of contractors

Historians have agreed that the selection of contractors took place via public auction. In practice, anyone who wanted to compete for a contract had to submit one or more bids (i.e. the price at which they were willing to supply the meat) during the auction period (the period when the town hall doorkeeper announced that the city council was looking for bidders for supply contracts). There could be several bidders and whoever offered the lowest bid secured the right to supply the city with meat, with the formalization of the contract dependent on the presentation of valid guarantees and collateral. The process of selecting the contractor corresponds to a descending auction, in which the price starts at a certain bidding base price and decreases until none of the bidders agrees to go any lower, with the lowest bidder winning.

An auction is a market institution with an explicit set of rules that determine the allocation of resources and prices based on bids from market participants. In some cases, auctions are used to maximize price, in others to evaluate products that do not have a defined value or that the auction organizer has difficulty evaluating.Footnote 52 Auctions for municipal supply also aimed at arriving at a ‘fair’ price that could be maintained until the end of the contract, thus rewarding stability. The auction allowed several agents to submit bids for the provision of a service, which created competition and a higher probability that the winner would be the most capable of fulfilling the contract. Ideally, the competitor who was the most efficient in supplying the product would be able to bid a lower price. Auctions could allow bidders to present pertinent information such as their capabilities, performance history, available resources, associated risks and proposed strategies.Footnote 53 This information could be important for the city council in a number of ways, for example, to establish the basis for bidding on the next contract.

Auctions played an important role in maximizing the value of a product or service. In this particular case, it was to reduce the price of a service. The municipality did not have as much information about the market, so by acting in a position of information asymmetry in relation to the bidders, the auction could result in a price for the service closer to its real value. Given that the agents worked to make a profit, they were incentivized for efficiency, since the contracts stipulated that the more they sold, the more they earned.Footnote 54 The impact of auctions on supply prices can be understood by considering several bidding records for the Coimbra City Council supply contract. The tables contain the records of the bids submitted, with the variation between the initial value and the final winning bid.Footnote 55

An auction with a minimum of two bidders could have a significant impact on prices. According to Table 1, for beef, auctions decreased prices on average by 11 per cent. As a rule, the more bidders, the greater the decrease in the value of the contract. In the case of veal, the decrease in prices on average was 12 per cent. For lamb, the average drop was 5 per cent, because some auctions did not lead to any change in price.

Table 1. Bids: dates, prices and variation from the first to the last bid

Sources: MHAC, Notas; MHAC, Arrematações e Arrendamentos.

The literature has emphasized that information asymmetry (i.e. different levels of knowledge that the players have about a deal, which would generate advantages for one of the parties) is fundamental to auction theory. More specifically, there are significant differences between auctions in which bidders know how many rivals they have and the value of their bids (the case of the English-style public auction) and auctions in which the number of competitors and the amounts of their bids are unknown (closed bidding auctions by envelope, for example). Information asymmetry also occurs in other respects, such as market conditions, the intrinsic value of the goods or services being auctioned or personal preferences.Footnote 56 In this particular case it can be assumed that asymmetry of information about market conditions could exist, but with regard to bidding, this would not be the case. The bidding records were public and the auction records show that, before the end of the auction, the doorman would publicly ask if anyone wanted to submit a bid lower than the last offer.Footnote 57 Bidders were therefore well informed about the number of rivals and the value of their bids.

If the bidders made an offer without knowing the bids of the competitors and then went on to win the auction, the price they paid for the contract would have been the same as their own ‘ideal bid’ – in other words, they would pay exactly what they were willing to pay. However, in this case, the bidders knew what their competitors were bidding. Having this information and assuming that the bidders were risk-neutral, the bidders could be offering lower bids than they originally wanted (due to incomplete information or the influence of subjective factors such as emotions). In the event of winning the auction, they would end up charging less for the meat than they had originally intended.Footnote 58 Such a result would be an advantage for the municipality, since in its notion of a ‘fair price’ the interests of the population were more important than the interests of the contractor. Even so, it seems that the absence of asymmetry of information regarding the bids was an important mechanism in the operation of this auction and could lead agents to offer bids that were not so financially advantageous for them. When bidders pay more (or, in the case of the contracts analysed here, less) for the value of the object than they originally intended, it is known as the ‘winner’s curse’. This occurs when the winning bid in an auction is not aligned with the intrinsic value or real value of the product.Footnote 59

Asymmetry of information seems to have been more relevant between the agents and the municipality. The municipality delegated supply for the reasons given above, which were reflected in the contract. If the municipality had perfect information about market conditions, it would not have incurred any risks or monitoring costs, and would therefore have been able to supply the city with meat itself at a reasonable selling price. The fact that the municipality did not know the market forced it to resort to auctions so as to establish a price that it would not have been able to determine on its own.Footnote 60

The evolution of meat prices and consumption

The choice of the supply system and the type of contracts to be used entailed decisions that resulted in various consequences, such as price and the quantity of meat available for consumption. Due to the scarcity of sources, it is challenging to determine the consequences with any certainty. However, by drawing on numerous scattered references, it is possible to gain at least a partial picture. The evolution of prices presented below and municipal intervention in supply, more generally, must be understood within a specific context. During this period, the contracts required the agents to supply all the meat required by the city’s population. Only between 1627 and 1665 was a minimum amount to be supplied per week stipulated, due to the economic difficulties and shortage of livestock at the time, which increased transaction costs.Footnote 61

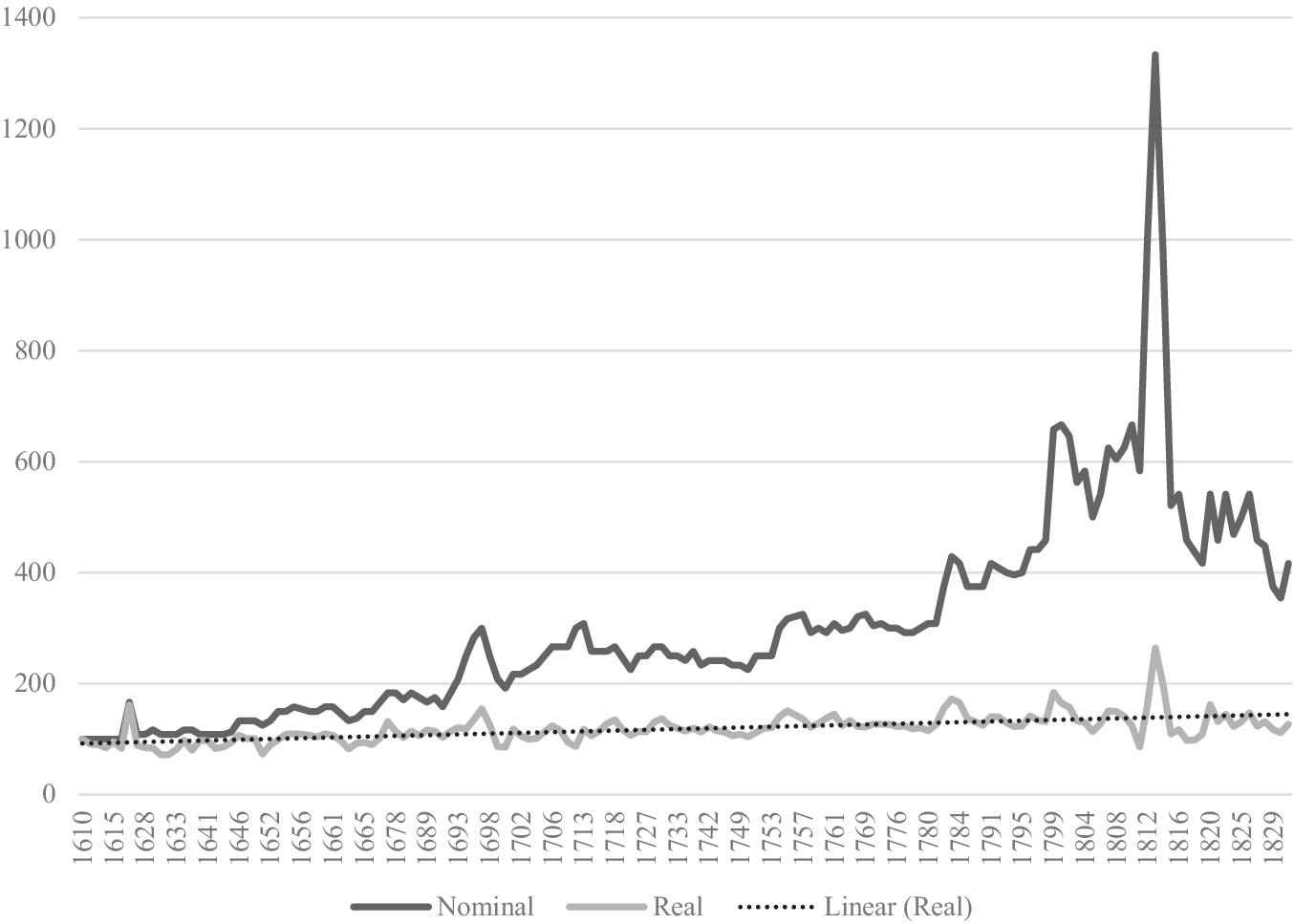

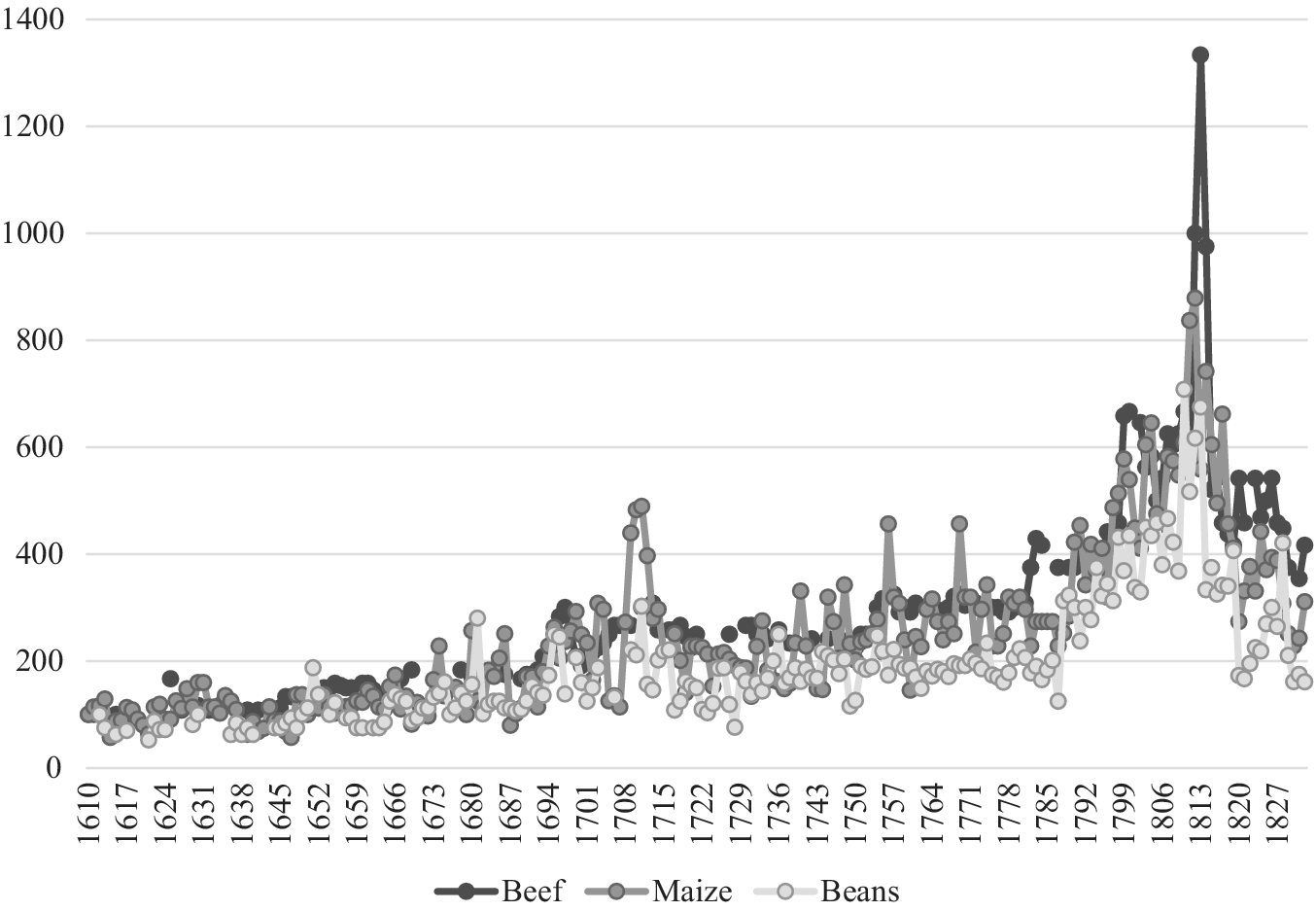

From Figure 1 it can be seen that the nominal price of beef grew significantly over two centuries, from an index of 100 in 1613 to 416.67 in 1832, with a very high peak in 1813, reaching 1333.33. At real prices, the increase was smaller, going from an index of 100 in 1613 to 126.95 in 1832, with the index reaching 264.15 in 1813.

Figure 1. Indices of the price per pound of beef, 1610–1832 (deflated, index 100=1610).Footnote 62

Sources: AHMC, Notas; AHMC, Arrematações e Arrendamentos.

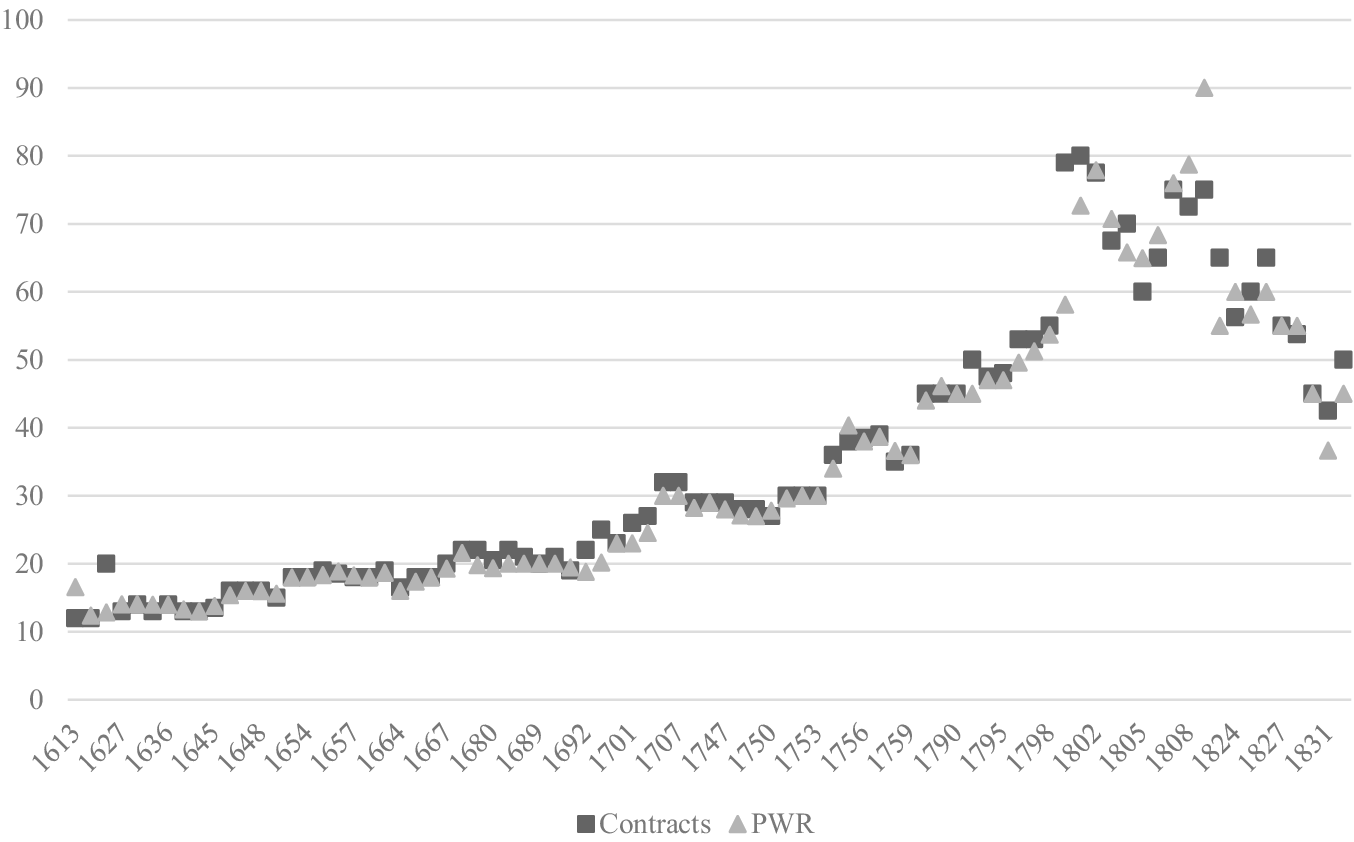

A comparison of the prices listed in the contracts with actual sales pricesFootnote 63 reveals whether or not the municipal price list was actually complied with. Eighty-three samples were collected, i.e. 83 years in which the prices from the contracts (tabulated) and from the PWR database (retail prices) can be confirmed. Figure 2 shows that the coefficient of determination between the two variables is extremely high (0.962). Of the 83 samples, in 29 years (c. 35 per cent) the sales prices (PWR) were higher than the maximum value set by the contracts; in 44 years (c. 53 per cent), they were lower; and in 10 years (c. 12 per cent) they coincided. It is important to note that the tabulated prices represented maximum prices, allowing meat to be sold below these levels. As a result, a higher percentage of sales were recorded at prices lower than the tabulated ones. In most years, the municipality successfully prevented meat from being sold above the contracted price through contracts and inspections, demonstrating its ability to enforce the established price limits for beef.

Figure 2. Linear regression between beef contract prices (tabulated) and prices from the Prices, Wages and Rents (PWR) database (sales prices), 1613–1832.

Sources: MHAC, Notas; MHAC, Arrematações e Arrendamentos; PWR database.

As far as veal is concerned (Figure 3), the prices increased very slightly, which demonstrates the municipality’s ability to prevent a significant rise due to increased inflation during the period. However, it should be emphasized that the municipal senate only intervened in the supply of this meat between 1750 and 1798. The (deflated) price of veal rose to an index of 119.73 during this period.

Figure 3. Index of the price per pound of veal, 1750–98 (deflated, index 100=1750).

Sources: MHAC, Notas; MHAC, Arrematações e Arrendamentos.

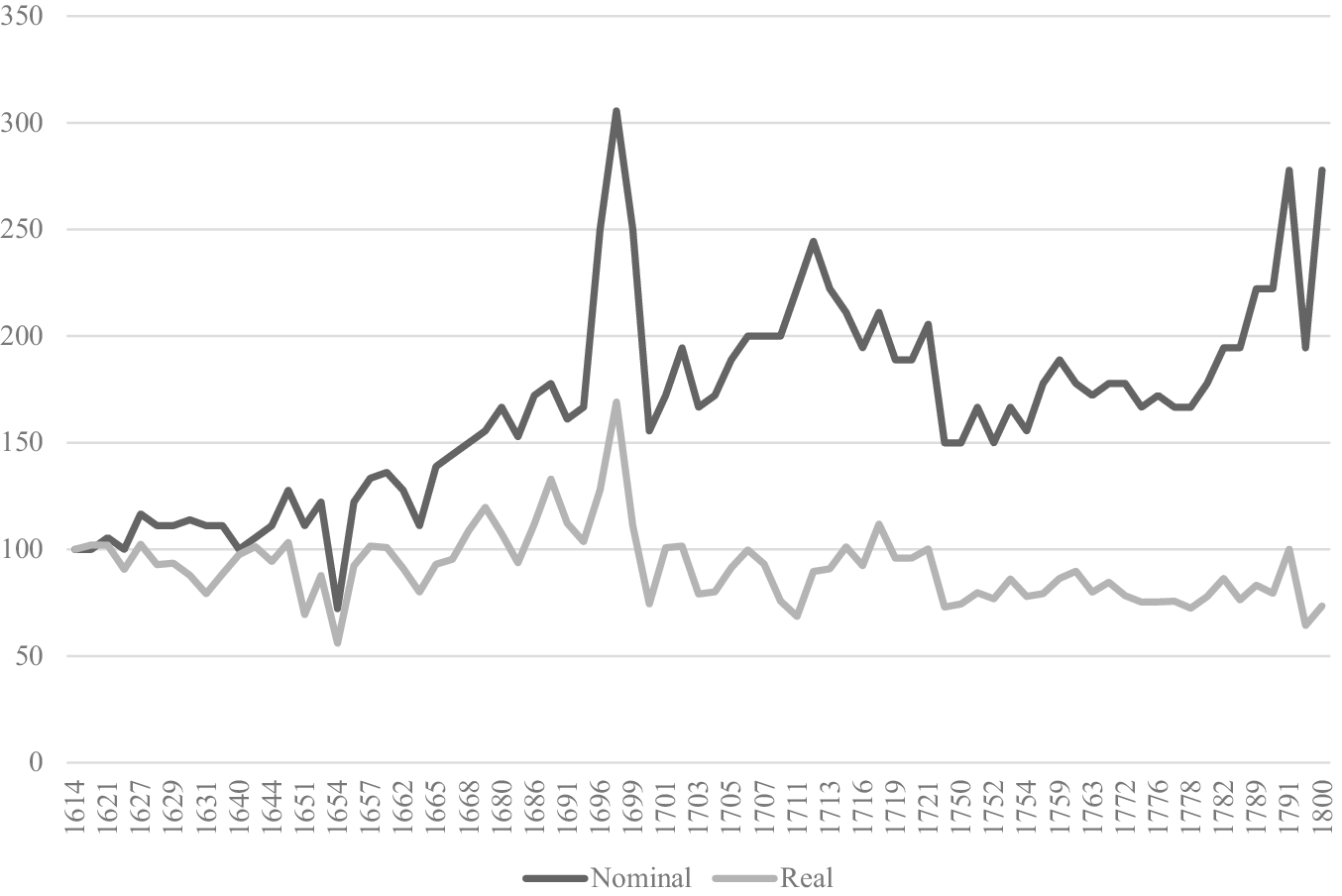

In the case of mutton (Figure 4), it can be seen that there was a decrease in its real price over the period studied. In nominal prices, there was an increase between 1614 and 1800 to 277.78. In real terms, there was a decrease to 73.44. As noted above, the auctions for the supply contract for mutton were less competitive and had a less significant impact on the final price. The fall in price is therefore linked to other factors, such as an increase in supply, a reduction in transaction costs, a fall in demand or an increase in the supply of other types of meat.

Figure 4. Index of the price per pound of mutton, 1614–1800 (deflated, index 100=1614).

Sources: MHAC, Notas; MHAC, Arrematações e Arrendamentos.

In comparison, in Porto the real price of beef rose from an index of 100 in 1787 to 120 in 1797 – as shown here for the case of Coimbra, the intervention of the municipality was fundamental in preventing an uncontrolled rise in prices.Footnote 64 The municipality’s ability to intervene in preventing prices from rising was also felt in Vitoria, Spain, in the first half of the eighteenth century, where the price of mutton showed a slight decrease, while the price of beef stagnated.Footnote 65 Of course, the situation was not identical in all municipalities. In Zaragoza, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the economic decline that took place in Aragon and the growing municipal indebtedness led to a reduction in public interventionism in the meat market.Footnote 66 However, the municipality of Coimbra was not heavily indebted,Footnote 67 as it borrowed money from the real de água tax to finance the contractors, which took the pressure off. While loans given by the municipality of Coimbra to the contractors were interest-free, some loans from the Spanish municipalities included interest,Footnote 68 which was less of an incentive for the contractors, but may be an indicator of greater profits. Even so, the free credit for contractors in the municipality of Coimbra may have been another factor behind the system’s longevity.

In a few Spanish municipalities contracts had a duration of three years, meaning that prices could not be renegotiated.Footnote 69 It was common for there to be large discrepancies between the value of the meat supplied and the real value of the animal, which discouraged contractors.Footnote 70 In Coimbra, the contracts were for one year or less (these were the exception), which gave the system more flexibility to adjust prices at the new auction the following year, although it did not give the municipality the stability that longer-term contracts provided.

Another major difference between some Spanish municipalities and Coimbra is that some municipalities had to divert money from meat supply income to other municipal expenses. The transfer of resources from the supply system for other purposes led to difficulties in its operation.Footnote 71 In Coimbra loans for supply came from a tax on meat and wine consumption. The sharp variation in prices could lead to a restructuring of the supply system, as happened in Zaragoza between 1651 and 1700. A decrease in meat consumption led to a very large drop in prices.Footnote 72 This article shows that the supply system used by Coimbra City Council was remarkably stable, having adjusted to periods of very high inflation followed by sharp deflation, as well as surviving military conflicts such as the Portuguese Restoration War (1640–68) and the Peninsular War (1807–14). Since the majority of contractors signed only one contract, as well as evidence pointing to poorly contested auctions, we conclude that the system was not very appealing to merchants. The system functioned sufficiently well, however, to ensure its continuity.

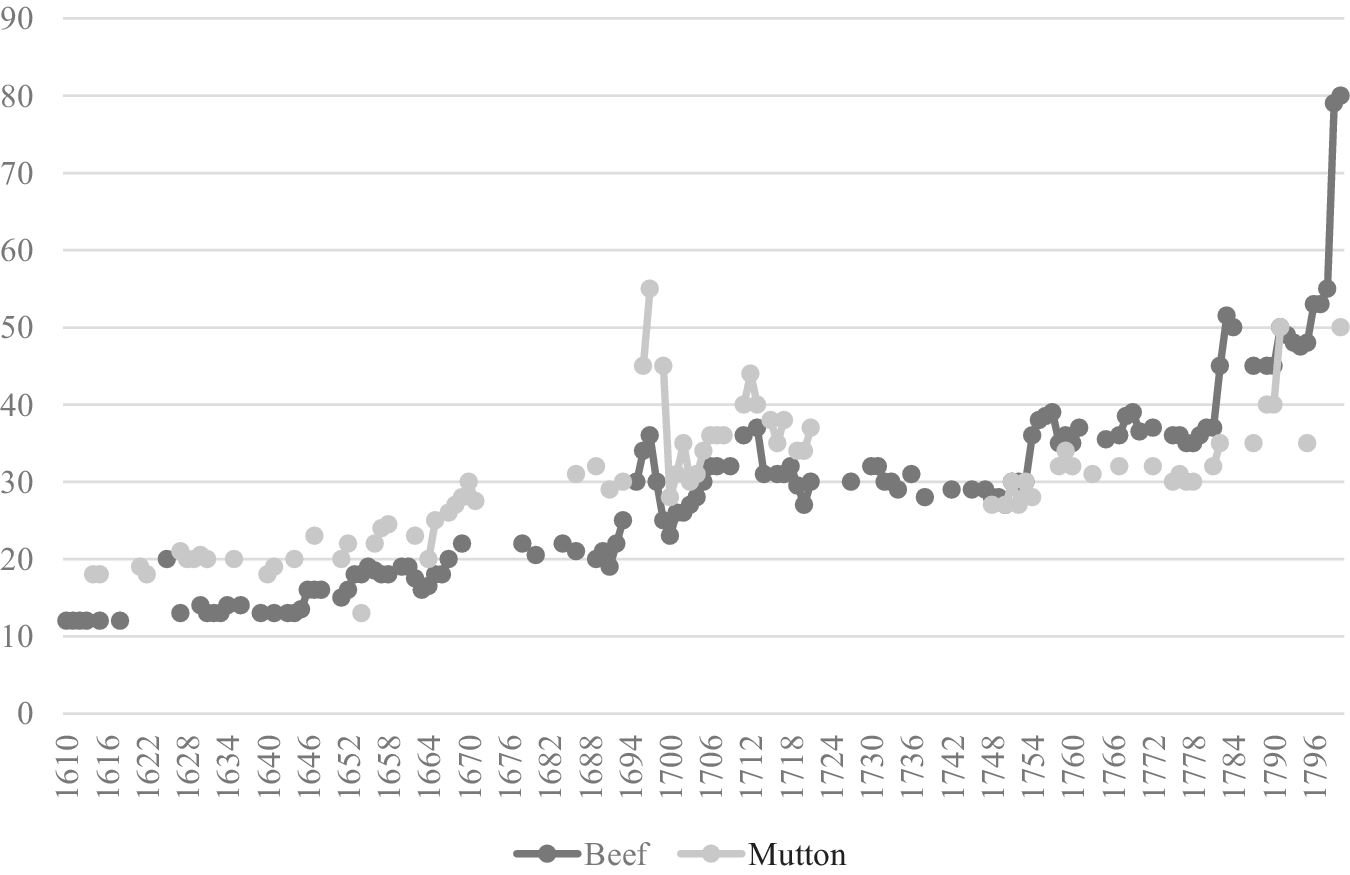

A comparison of the price of beef with that of mutton (Figure 5) demonstrates that, until the mid-eighteenth century, beef was cheaper, but afterwards, it became more expensive. It is not clear whether this issue was related to supply or increased demand, but it is the inverse to what occurred in Spain.Footnote 73

Figure 5. Beef and mutton nominal price (1610–1800).

Sources: MHAC, Notas; MHAC, Arrematações e Arrendamentos.

Comparing beef with other widely consumed products in Coimbra (Figure 6), such as corn and beans (based on Jaime Reis’ consumption basket),Footnote 74 it can be seen that the price of meat experienced the greatest increase over the period analysed here. Table 2 shows that the variation in the price of meat was very high, second only to the price of wine. This demonstrates that even with municipal regulation and control over prices, it was not possible to prevent significant increases or variation in the price of beef.

Figure 6. Beef, maize and beans nominal prices index comparison (100=1610).

Sources: MHAC, Notas; MHAC, Arrematações e Arrendamentos; PWR database.

Table 2. Standard deviation of nominal prices index (1610–1832)

Sources: MHAC, Notas; MHAC, Arrematações e Arrendamentos; PWR database.

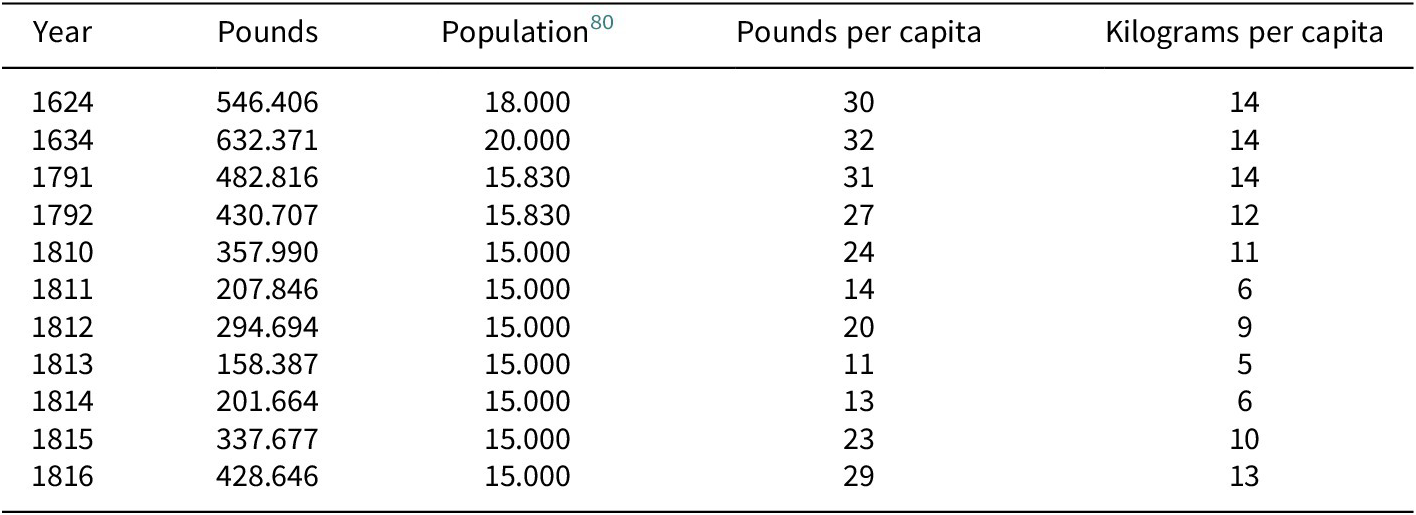

Although sources for per capita meat consumption in Coimbra are quite incomplete, they can nevertheless support some initial conclusions. Available records, such as books listing cattle for slaughter, provide relevant data. Sources from 1624 and 1634 indicate that, on average, a cow yielded 9.2 arrobas of meat, with one arroba equating to 32 arráteis (roughly one pound).Footnote 75 These data will be used to estimate consumption during specific periods. However, before doing so, it is first necessary to analyse population growth as a proxy for demand.

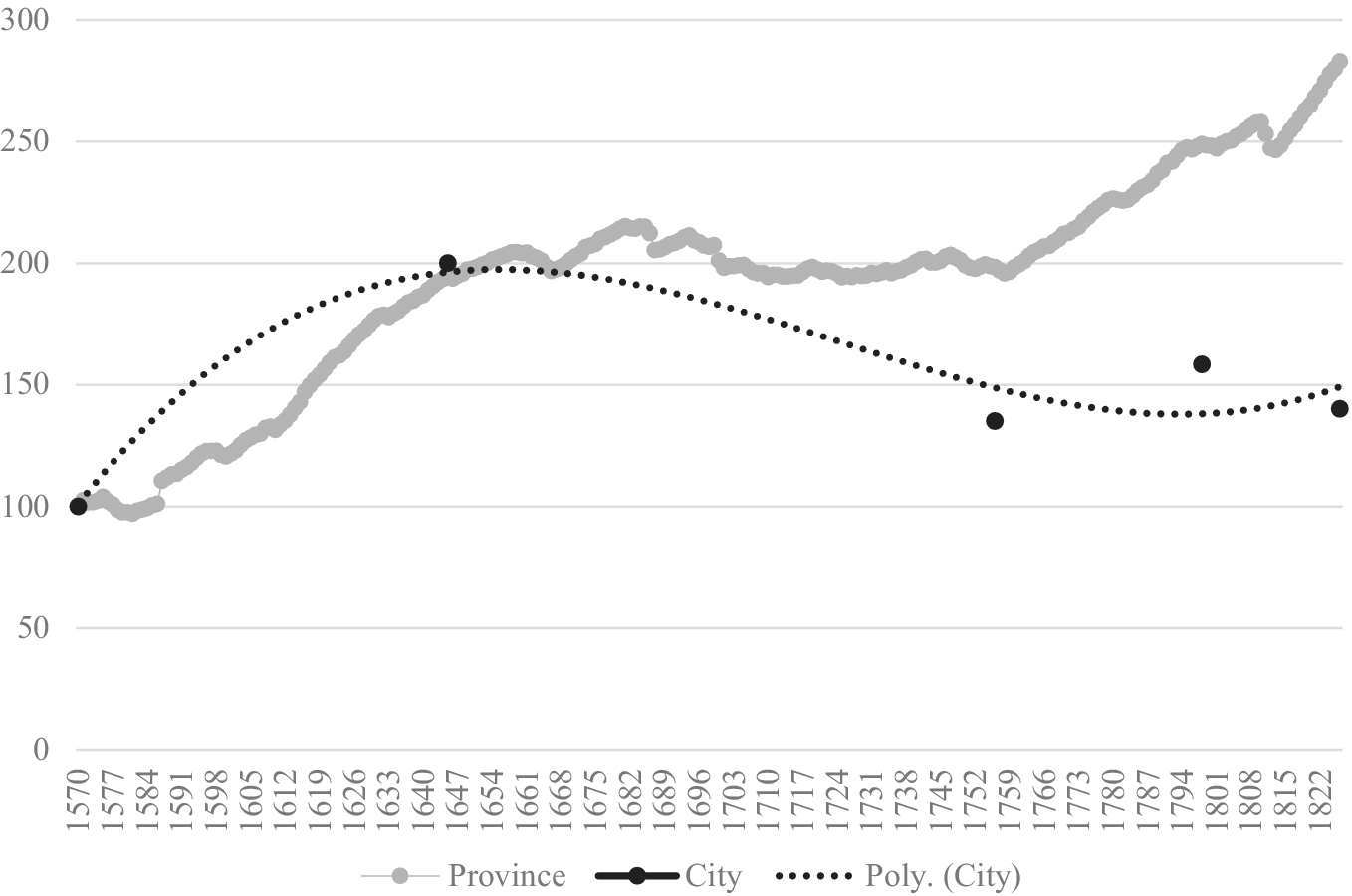

During the early modern period the Portuguese population more than tripled. In particular, Beira province (in which Coimbra is situated) was one of the areas that experienced the highest growth (Figure 7). But sources for the population of the city show a different pattern of decline: 20,000 inhabitants in 1645, 13,500 inhabitants in 1756, 15,830 by 1798 and 14,000 inhabitants recorded in 1826.Footnote 76

Figure 7. Population in the Beira province and in the city of Coimbra, 1570–1826 (Index 100=1570).

Source: See Footnote footnote 76.

The early modern period was also one of high inflation, particularly during the second half of the eighteenth century and the early decades of the nineteenth century. In terms of real prices, there was an increase in the consumer index from 100 in 1600, to 405 in 1800, 679 in 1811 and 328 in 1832.Footnote 77 The rise in prices put severe pressure on people’s purchasing power. As Carlos Faísca has pointed out, purchasing power fell in Coimbra during the seventeenth century,Footnote 78 a trend that continued in other parts of the kingdom in the eighteenth century due to rising prices and stagnating wages.Footnote 79

Table 3 shows that per capita consumption declined significantly from the seventeenth century through to the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Closer examination reveals that between 1810 and 1816, the Napoleonic Wars had an extremely detrimental impact on the Portuguese economy. In particular, during the years 1810 and 1811, supplies to the city were interrupted. The data for 1791 and 1792 are not very different from those for 1624 and 1634, but in 1816 a possible improvement can be seen. Although the information on consumption is partial, it suggests that municipal intervention did not ensure the growth of per capita beef consumption, despite the city’s population decreasing throughout the period. Future research may clarify this issue, but one potential cause could be the reduction in grazing land for livestock, as it was replaced by agricultural land.

Table 3. Yearly consumption of beef in Coimbra

Source: MHAC, Real de água – manifestos.

The supply system with municipal intervention continued in subsequent years. The recorded contracts become increasingly rare until the 1860s.Footnote 81 From that point onwards, municipal supply contracts disappear until the First Republic (1910), except in specific cases, such as the supply of beef and mutton to an asylum for people with disabilities in 1909.Footnote 82 In summary, after centuries of municipal involvement, the transition to a meat supply market without the intervention of the Coimbra City Council occurred gradually during the nineteenth century.

Conclusion

Risk and transaction costs were fundamental in delegating responsibility for meat supply to private contractors and are clearly evident in the drafting of the contracts. As was common in other Portuguese and Spanish municipalities, Coimbra City Council gave up responsibility for the direct supply of meat, opting for a service that was considered cheaper, less risky and more efficient. For the contractors, this was a business in which the more they sold, the more they could profit, which incentivized them to increase their efforts. Despite the constraints of the contract clauses and the penalties for non-compliance, the incentives were sufficient for these entrepreneurs to accept the inherent risks and costs. Significantly, this choice also highlights the municipality’s inability (or unwillingness) to carry out one of its most important functions and to establish its own supply structure, based on an organized bureaucratic system and efficient monitoring mechanisms. However, the municipal supply system failed to increase per capita beef consumption, despite the demographic decline.

The selection of agents was based on a descending auction, where the lowest bidder won. Bidders knew the number of competitors and the value of their bids, which encouraged competition to lower prices. Empirical evidence suggests that even limited competition could significantly reduce prices. While the absence of bidders indicates concerns about lower profits, this also harmed the municipality, as prices did not decrease as much as they could have done. The auctions provided Coimbra City Council with a mechanism to more accurately assess the real value of the service it intended to lease. This system allowed the council to achieve a ‘fair price’, balancing the need to satisfy suppliers to ensure contract acceptance, while also considering the subsistence needs of the population.

It is difficult to determine whether the municipality’s objective of ensuring a fair price and sufficient supply was fully achieved. Price trends indicate that some meats became more expensive, while others became cheaper. This suggests that the supply system had mixed success, depending on the type of meat. In some instances, the City Council managed to keep prices below the general inflation rate, but for meat, this was not the case. The evidence shows that the price of beef increased more and fluctuated significantly compared to most basic products. While per capita consumption remained stable in the late eighteenth century, it was notably impacted by the Napoleonic Wars. Despite a declining city population throughout the early modern era, supply challenges persisted. The system faced many difficulties: although it met the municipality’s needs, it could not prevent the rising cost of beef. However, it succeeded in lowering the real price of mutton. Unlike some Spanish cities, the challenges of supplying the city did not lead to the liberalization or modification of the system in the early nineteenth century, and it remained unchanged until the second half of the century.

Funding statement

This research was funded by Portuguese national funds via the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), I.P., under project reference SFRH/BD/143897/2019. The author also gratefully acknowledges the financial support provided by the Center for the History of Society and Culture for the revision of this text, under the project reference UIDB/00311/2020 (CHSC – FCT).