Introduction

There are very few Moors in Siam. The Siamese do not like them. There are, however, Arabs, Persians, Bengalees [sic], many Kling, Chinese and other nationalities. And all the Siamese trade is on the China side, and in Pase, Pedir and Bengal. The Moors are in the seaports. (Pires Reference Cortesao1944: 104)

This article reconstructs the geopolitical and commercial developments connected to the arrival of Indian Muslim merchants (Kling in the Malay World and Khaek in Siam) in Ayutthaya at the beginning of the sixteenth century. This study introduces, analyses, and aggregates fragments written in—and about—the Coromandel Coast, Melaka, and Ayutthaya. The Kling's contribution to Ayutthaya's ethnic and religious diversity spans many periods and places and includes many actors—most of which have been overlooked in extant treatments of Thailand's Muslim minorities (see Dalrymple and Joll Reference Dalrymple and Joll2021; Joll and Srawut Aree Reference Joll and Aree2020; Joll Reference Joll, Grabowsky and Ooi2017). This research's initial interest in Indian Muslims in sixteenth-century Ayutthaya is connected to an exploration of Ayutthaya's oldest shrine (Ar. Maqam) to Tok Takia, a Sufi saint.Footnote 1 Whilst this comprises the subject of a separate study, local traditions are emphatic that Tok Takia travelled to Ayutthaya, the former Siamese capital, from the Indian subcontinent, sometime between the reigns of King Ramathibodi II (r. 1491–1529) and King Chakkraphat (r. 1548–1569). This current study resulted from the growing confidence that more could—and should—be written about the local Muslim presence during this period; indeed, both sixteenth-century primary sources and the relevant secondary literature.

John Villiers argues that there is a problematic lack of detailed Spanish and Portuguese accounts of Siam during the sixteenth century, despite the influential presence of Iberian mercenaries, merchants, and missionaries during this period. Of the accounts that do exist, many may be replete with both “prejudices, intolerance and ignorance” and tendencies to “distort, exaggerate and even invent” statistics, but none of these deficiencies preclude historians from offering “many valuable insights” (Villiers Reference Villiers1998: 119). In fact, Geoff Wade regards Tomé Pires's Suma Oriental (Pires Reference Cortesao1944) as “unparalleled” (Wade Reference Wade and Schottenhammer2019: 118), although Sanjay Subrahmanyam refers to Pires as being frequently “cryptic” (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam2011: 141). Pires also argues that there were few Muslims (or “Moors”) in Ayutthaya, and that the Siamese disliked them. Moreover, along with “Chinese and other nationalities,” there were also “Arabs, Persians, Bengalees” in Ayutthaya. Not only does Pires mention the presence of the Kling, but also that these Indian Muslim traders were numerically significant (Pires Reference Cortesao1944: 104).

Siamese attitudes towards Muslim merchants in subsequent decades might explain Duarte Barbosa's observation that local Muslims were not permitted to bear arms (Barbosa and Stanley Reference Barbosa and John Stanley2010: 188). Michael Pearson’s study of religious change during the sixteenth century contends that, in the 1550s, the notoriously unreliable Fernao Mendes Pinto—whom Pearson describes as “adventurer-turned-religious”— asserted that Turkish and Arab missionaries were active in Siam and, furthermore, that they were “doing very well.” Pinto documents “seven mosques,” served thirty thousand local Muslims, which were led by foreign Muslim leaders.Footnote 2 Local Muslim proselytisation had “proceeded apace,” which Pinto attributed to the more detached governing style of King Chairacha (r. 1534–1547), who permitted everyone to “do what they want[ed]”, as he was a king of “nothing more than their bodies” (Pearson Reference Pearson1990: 59, 68–69; da Silva Rego Reference da Silva Rego1947: Vol. V 372). Another anecdote recorded by Pires was that, in the local markets, Kling cloth “in the fashion of Siam” could be bought (Pires Reference Cortesao1944: 108). Further substantiating Pires's claim, Wade notes that Indian textiles were mentioned in fifteenth-century accounts of Siam (Wade Reference Wade2000: 273); Baker and Phongpaichit Baker, however, point out that Indian clothing had “already . . . [been] made in southern India for export to Siam” (Baker and Phongpaichit Reference Baker, Phongpaichit and Nunsuk2017: 88; Baker et al. Reference Baker, Pombejra, van der Kraan and Wyatt2005: 221).

In sum, the local accounts of Tok Takia having come to Ayutthaya from the Indian subcontinent, mention in Portuguese sources of Kling and textiles from South Indian in local markets, suggest that fragmentary sources were no impediment to undertaking this study's ambitious task. This research overcomes these potential obstacles (i.e., both the small number of primary sources and the fragmentary nature of references in the relevant secondary literature), in a threefold manner. First, this study pays particular attention to the sixteenth-century geopolitical and commercial context in Melaka, the Coromandel Coast, and Siam—the most important context being the Portuguese defeat of Melaka in 1511. Second, this research explores the synergy between Thai and Malay Studies specialists.Footnote 3 Other scholarly silos that this study connects are South Asian and Southeast Asia Studies across the Bay of Bengal.Footnote 4 Third, this research takes into account Joll's anthropological background (Joll Reference Joll, Marranci and Turner2011, Reference Joll, Jory and Bustamam-Ahmad2013) by contending that the paucity of primary sources can be compensated by homing in on the exonyms Kling and Khaek.Footnote 5 While some Kling may have been Hindus, attention to how certain exonyms were employed do indeed fill some important empirical gaps about how Kling Muslims contributed to Ayutthaya's ethnic and religious cosmopolitanism.

Additionally, this study focuses solely on sixteenth-century Ayutthaya for the following reasons. First, based on Persian (Muhammad Rabi ibn Muhammad Ibrahim Reference O'Kane1979) and European sources (Gervaise Reference Gervaise and Villiers1989; Tachard Reference Tachard1688; La Loubère Reference La Loubère1691; Baker et al. Reference Baker, Pombejra, van der Kraan and Wyatt2005), much has already been written about Islam's growth in the seventeenth century.Footnote 6 Subrahmanyam notes that early-sixteenth-century Portuguese accounts of the eastern Bay of Bengal littoral mention Iranian merchants (Bouchon and Thomaz Reference Bouchon and Thomaz1988: 18), describing that they remained “relatively small” in number until a “rapid florescence” during Narai's reign (r. 1656–88) (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam1992: 348). Secondly, there are few fragments referring to Muslims in Siam during the fifteenth century. Wade's encyclopaedic analysis of the Ming Shi-lu (Veritable records of the Ming Dynasty) (Wade Reference Wade1994, Reference Wade2005) cites evidence linking Siam and the Indian Ocean, the first being a reference from 1403, which states that a Ha-zhi (Haji) from the “Western Ocean” travelled to China—a place he had heard about while in Siam” (Wade Reference Wade2000: 273). Baker notes that the “Timurid chronicler,” Abd-er-Razzak (Abd-er-Razzak Reference Major1857), mentions that the “Persian Gulf port of Hormuz traded with Ayutthaya in the 1440s” (Baker and Phongpaichit Reference Baker, Phongpaichit and Nunsuk2017: 127), while Andrew Peacock bases his analysis on Arabic and Persian sources appearing in Ottoman geographical treatises that use the toponym Shahr-i Naw for Ayutthaya (Peacock Reference Peacock and Kadi2017). Shihāb al-Dīn Ahmad ibn Mājid, an Arab navigator, includes a description of the western coast of the Malay peninsula in his Hawiyat al-lkhtisar ’ilm al-Bihar (1462) (See Tibbetts Reference Tibbetts1979: 187–189). This is followed about fifty years later by a more “detailed and accurate” navigational manual by Sulaimān bin Ahmad al-Mahrī (1511). In both navigational works, especially in comparison to east coast of the Thai-Malay Peninsula, its western littoral is described in great detail. The importance of al-Mahrī’'s work is twofold: first, its “growing awareness” of Ayutthaya, and the territories it controlled” and, second, that trading with Ayutthaya did not require making the “long trip round the peninsula” along the eastern littoral (Peacock Reference Peacock and Kadi2017: 7–8).

Within this context, this article builds on other scholars’ analyses of key geopolitical ruptures and re-routing trade away from the Straits of Melaka. Chris Baker, for example, argues that it was well-known that Ayutthaya was both a predominantly urban polity (rather than agrarian) and was heavily involved in commerce and manufacturing, arising from the geographical fact of its proximity to the sea (Baker Reference Baker2003, Reference Baker2011). Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit's History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World (Reference Baker, Phongpaichit and Nunsuk2017) documents that the local “gradual accretion of peoples” over the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had “intensified” during the seventeenth century, arguing that the intensification impacted Ayutthaya's cosmopolitan characteristics (Baker and Phongpaichit Reference Baker, Phongpaichit and Nunsuk2017,: 203). In fact, Much has already been written extensively on the ways in which Aceh, Johor, Banten, Makassar benefitted from the vacuum created after Melaka's demise (Lieberman Reference Lieberman2009: 845–853). Whilst Kenneth Hall's research documents the gains also made by. Ayutthaya, somewhat surprisingly Hall considers contributions by Persians and Indo-Persians in the seventeenth century (Hall Reference Hall2014: 241–251), which may have been due to the fragmentary nature of the sources he used and which this current study introduces, analyses, and aggregates below. Another seminal contribution this study builds on is Michael Feener's argument that a range of unintended consequences followed in the wake of Iberia's 1511 interventions. In the fifteenth century, Melaka is widely regarded as Southeast Asia's “preeminent entrepôt,” which was central to “expanding maritime Muslim networks.” Nevertheless, the Portuguese not only failed to achieve a “monopoly on regional trade,” but also they inadvertently catalysed diasporas, which in turn led to the emergence of “new Muslim communities across the region.” As this study explores in more depth below, this included Kling Muslims in Ayutthaya (Feener Reference Feener2019: 5).

This article's structure reflects its methodological approach. First, the essay begins by describing the wider geopolitical and commercial context between Melaka and Ayutthaya (before 1511), diplomacy between the Portuguese and Siamese (before 1511), and commercial and military allies in the decades that followed. This study then analyses Siam's incremental acquisition of a series of ports and portages through which Kling merchants traded in early modern Siam. Next, the Malay exonym Kling and the Siamese exonym Khaek become this article's focus, offering compelling reasons for why most Kling in Ayutthaya would have been Muslims. The third and final section reconstructs the Kling's involvement in trade among the Coromandel Coast, Melaka, and Ayutthaya throughout the sixteenth century. Furthermore, this study's careful aggregation of written fragments both establishes a context and reconstructs vital connections about key events and actors that have been overlooked in extant treatments of Thailand's Muslim minorities—many of which begin with Persians’ and Indo-Persians’ seventeenth-century contributions to Ayutthaya’s confessional and cultural cosmopolitanism. For example, the presence of many Kling Muslims in Siam, which Tomé Pires documents, pre-dates the Persian and Indo-Persian writing by a century. In fact, Kling were involved in the growth of Ayutthaya's Muslim community commented upon by the fellow-Portuguese Fernao Mendes Pinto.

Competitions, Conquest, and Cooperation, before and after 1511

Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit's history of early-modern Ayutthaya establishes that the competition between Melaka and Ayutthaya began in the late thirteenth century when Siamese ships sought to subjugate local rulers and demanded a share of the coastal trade after Srivijaya’s demise (Baker and Phongpaichit Reference Baker, Phongpaichit and Nunsuk2017: 48, 50). After Ayutthaya attempted to install rulers in the 1390s, Siamese troops returned to Ayutthaya with Chinese seals and patents. These interventions sought to disrupt Melaka’s trade with China's Ming Dynasty, who responded by constructing a stone tablet clarifying Melaka’s status. In 1419, the Chinese again warned Ayutthaya, which led the Siamese paying tribute to China—in part to atone for attacking Melaka. In 1431, Melaka appealed to the Chinese court, which likely explains why reports documenting rogue operations by Ayutthaya along the Siamese/Malay Peninsula faded from Chinese records. In the mid-1440s, the rulers of Ayutthaya again demanded tribute, which might be connected to a failed attack on Melaka, as referenced in the Malay Annals. In the mid-1450s, the Ayutthaya Chronicle mentions another mission to Melaka, which was followed by both a “tribute mission to China,” and a Melakan “mission of peace to Ayutthaya” (Baker Reference Baker2003: 47–48).

Siamese attacks on Melaka may have ceased by the mid-1400s, but by 1490 Ayutthaya’s campaigns against the Burmese led to them gaining control of Burma's ports and portage routes connecting Ayutthaya with the Bay of Bengal (Baker Reference Baker2003: 48; Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit Reference Baker and Phongpaichit2017: 117; Baker and Phongpaichit Reference Baker, Phongpaichit and Nunsuk2017: 87–88). These attacks began with capturing Thaithong (north of Tavoy), but by the 1460s both Tenasserim and Mergui were also under Siamese control; Tavoy followed in the late 1480s. Notably, both Tenasserim, and Mergui were the “best natural harbour[s]” at the western ends of portages (Baker and Phongpaichit Reference Baker, Phongpaichit and Nunsuk2017: 87), and the value of these routes to Ayutthaya—particularly as Asian traders sought routes that avoided Melaka—increased after the Portuguese captured Melaka because Siam could be reached in ten and twenty days. Ayutthaya’s control of coastal ports and portages increased its westward trade and, importantly, during the reign of Ramathibodi II (r.1491–1529), Ayutthaya also expanded its trade to southern India. The value conferred by Jacq-Hergoualc'h’s reconstruction of the transpeninsular routes (Figure 1) is that they were some of the oldest portages closest to Ayutthaya and were used to conduct trade between Srivijaya and China.

Figure 1. “Relief and possible transpeninsular routes of the Malay Peninsula” (Jacq-Hergoualc'h Reference Jacq-Hergoualc'h and Hobson2002: 684)

In light of these events, the following question emerges: What form did Portuguese diplomacy with Ayutthaya—and its military and commercial collaboration—take, both prior to the Iberian invasion and in the decades that followed? Edward van Roy’s reconstruction of Portugal's attempts to establish a presence in Southeast Asia begins with Portugal building an operational base in Goa, India, in 1510. Before Alfonso d'Albuquerque’s began his military campaign on Melaka, a Portuguese envoy was sent to Ayutthaya—a “distant vassal” of Siam; he had been instructed to inform Ayutthaya's ruler of Portugal’s intentions and was delighted at the Siamese raising “no objections.” Notably, Portuguese accounts claim that Ayutthaya possessed “few guns,” but did have the skills to manufacture them. Alfonso d'Albuquerque returned to Portugal via the overland route, which afforded him the opportunity to survey and then offer an appraisal of the “Siamese vassal ports of Tenasserim and Martaban” and their “friendly intentions” to the new Portuguese presence. In 1512, another Portuguese mission commenced—one that included Tomé Pires—leaving Goa for Ayutthaya. The convoy then remained in Ayutthaya for two years, during which time they explored trade opportunities before returning (via Melaka) (van Roy Reference Van Roy2017: 42). Tomé Pires noted that there were “three ports in the kingdom of Siam on the Pegu Kingdom side,” and he referred to Siam as “large and very plenteous” possessing “many people and cities” with many “lords” and foreign merchants.” (Most of the merchants were Chinese because “Siam does a great deal of trade with China.”) According to Pires, the “land of Malacca is called a land of Siam,” and the whole of “Siam, Champa and thereabouts,” is called China (Pires Reference Cortesao1944: 103). Pires also asserted that the Siamese had not traded in Malacca for twenty-two years because Melaka's Malay monarchs refused to give allegiance to the kings of Siam, who claimed that Malacca “belongs to the land of Siam” (Pires Reference Cortesao1944: 103).

In 1516, the Portuguese in Melaka dispatched another ambassador to negotiate a treaty of “friendship and commerce,” which van Roy argues was the first Siamese treaty with a European power (van Roy Reference Van Roy2017: 42). Trading posts in both Ayutthaya and other Siamese ports were then established, through which the Portuguese supplied guns and gun powder. From 1515 on, Ayutthaya’s Portuguese settlement was led by a series of captains-major who were appointed in consultation with Siamese authorities from the Estado Portugues da India in Goa. Nevertheless, the hands-off policy pursued by the Portuguese meant that Ayutthaya was largely left to its own devices, which suited the Siamese for many reasons, including that, in 1518, the Iberians supplied “guns, munitions, and some Portuguese soldiers” as part of the third Portuguese mission. Baker and Phongpaichit note that these were co-opted in Ayutthaya’s campaign against Lanna (one of its northern rivals) (Baker and Phongpaichit Reference Baker, Phongpaichit and Nunsuk2017: 203). The Iberians involved may have been rewarded with permission to trade, but because the Portuguese had failed to source valuable spices, they instead concentrated on supplying “military expertise.” For instance, 120 Portuguese had joined King Chairacha's personal guard and, later, in the 1550s, João de Barros included “the west-coast ports of Tavoy, Mergui, Tenasserim, Rey Tagala (near Martaban), and Cholom (possibly modern Phuket) among Ayutthaya’s dependencies” (Baker and Phongpaichit Reference Baker, Phongpaichit and Nunsuk2017: 48, 88, 92, 93). Van Linschoten’s Exacta & accurata delineatio cùm orarum maritimdrum (1596) (Figure 2) is one of many portolan maps that European cartographers produced at the end of the sixteenth century; these maps identify important port-cities through a combination of adding port-cities and exaggerating harbour size—the largest being Mergui.

Figure 2. The profiling of prominent ports in Van Linschoten’s Exacta & accurata delineatio cùm orarum maritimdrum Footnote 7 (1596)

To summarise, although Ayutthaya played second fiddle to Melaka during the long fifteenth century, the Siamese began incrementally acquiring ports and portages to connect Ayutthaya to the Bay of Bengal. This is a likely explanation accounting for the speed with which Siam benefited by Melaka’s demise. However, but this study also documents the deft combination of diplomacy, military, and commercial cooperation between the Iberians and the Siamese, both before and after 1511. Before reconstructing how Kling traders from both the Coromandel Coast and Portuguese-controlled Melaka expanded their operations into Ayutthaya, this study next explores the range of exonyms employed in Malay, Thai, and European sources. Finally, this article presents compelling arguments for most Kling in Ayutthaya being Muslims.

Contexualising the Exonyms Kling and Khaek

Christoph Marcinkowski laments historians having no option but to work with fragments and surviving sources that use the exonym Khaek when referring to “non-Siamese individuals of Middle Eastern or Indian ethnic origin.”Footnote 8 These Khaek were a mixture of Siamese subjects, foreign residents, and visitors and, moreover, not all Khaek were Muslims (Marcinkowski Reference Marcinkowski, Formichi and Feener2015: 38). Expressing similar sentiments, Thongchai Winichakul refers to Khaek and Farang as the best-known examples of Siamese concerns with “ill-defined” national and ethnic otherness, which he refers to as “negative identification.” In other words: anyone who was either a Khaek or a Farang was emphatically not Siamese. The latter term refers to Westerners, while the former denotes those from the “Malay peninsula, the East Indies, South Asia, and the Middle East without any distinction” and, more generally, Muslims (Winichakul Reference Winichakul1994: 5).

In his 2019 doctoral dissertation, John Smith argues that the growth of foreign merchants involved in commerce in the sixteenth century increased Ayutthaya’s ethnic diversity. He cites a Siamese edict from 1599 listing foreign ethnic groups recognised by the court, which resembled an “expanded list” from the Palace Law (a Thai source from the fifteenth century) that specifically mentions the following as being prohibited from the rear palace: “Lao, Burmese, Cham, Javanese, Mon, Khmer and Chinese,” including the notoriously imprecise exonym Khaek (Pasuk Phongpaichit and Baker Reference Phongpaichit and Baker2016: 86). The 1599 edict relisted those included in the Palace Law, but in addition to there being no mention of the Javanese, the ethnonym Khula (Tamils) is added (Smith Reference Smith2019: 114).Footnote 9 This term, Khula, is not to be confused with the later English exonym, “Chulia.” According to Baker and Phongpaichit, Khula (or Kula) is an archaic generic Thai term for ‘strangers’; along with Khaek and Malayu, Khula was a term for people of the archipelago (Baker and Phongpaichit Reference Baker, Phongpaichit and Nunsuk2017, 208–209). In his empirically rich, recently completed doctoral dissertation, Matthew Reeder cites a Thai source from the late-seventeenth century referring to both Khula and Thamin. The latter is a Thai ethnonym of Pali origins denoting Tamils and that Thamin refers to Hindu or Muslim Khaek is clear by its reference to these people being the “enemies of the religion.” As Reeder notes, according to the Thai records, the Khaek Khula had “small bodies and dark skin,” similar to “people [who were] sailors” (Reeder Reference Reeder2019: 189).Footnote 10

Pivoting now from Ayutthaya to the Malay World, in his doctoral dissertation, “The Impact of being Tamil on Religious Life among Tamil Muslims in Singapore” (2007), Torsten Tschacher explains his concerns over historians employing the term Kling when referring to Tamil Muslims. Additionally, Subrahmanyam suggests that, at least etymologically, this term is derived from the toponym “Kalinga” (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam2011: 141). In Portuguese and, later, Dutch sources, South Indian Muslims are referred to either as Kling (or Keling), or the generic exonym “Moor,” which specifically denoted a mixture of Arab, Persian, or Indo-Persian Muslims. Tschacher argues that the exonyms used in European “travelogues, letters, and other documents,” are highly problematic for a number of reasons. First, there is a widespread lack of scholarly attention to the socio-historical and political context from which the primary sources emerge. Specifically, although the word Kling may appear in sixteenth-century Portuguese and nineteenth-century British sources, Tschacher cautions against making the assumption that these terms refer to the same ethno-religious and ethno-linguistic community (Tschacher Reference Tschacher2007: 24). Indeed, Tschacher’s concerns echo Leonard Andaya’s arguments against reading bounded ethnoreligious identities into pre-colonial Southeast Asia sources (Andaya Reference Andaya and Owen2014: 2008).

Tschacher contends that the term Kling must be appreciated as a Malay exonym (Tschacher Reference Tschacher2007: 25). In many contexts, Kling refers to Tamils, yet in many others, Kling also refers to people from the Telugu-speaking parts of South India. Although Kling appears in a number of Tomé Pires's accounts, Subrahmanyam argues that Pires employs Kling “far too loosely,” and possibly even confuses “merchants based in Melaka and those based in Coromandel” (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam1990: 97). Abdur-Rahman Mohamed Amin and Ahmad Murad Merican note that Malay dictionaries define Kling as merchants from the South Indian subcontinent, including Kalinga. They further point out that William Shellabear's Malay dictionary (published in the early twentieth century) defines Kling as people from the eastern coast of British India, especially the Telugus and Tamils. Notably, Shellabear does not specify whether the Kling were Muslims or Hindus. This led him to use the phrase “Kling Islam [Muslims],” most of whom were Tamils (Abdur-Rahman Mohamed Amin and Ahmad Murad Merican Reference Amin and Merican2014: 178).

Abdur-Rahman Mohamed Amin and Ahmad Murad Merican's second contribution is their analysis of the sixty-six references to Kling in Sulalat al-Salatin (also known as Sejarah Melayu or Malay Annals),Footnote 11 an important Malay epic that documents the genealogy and history of the Malacca Kingdom between the early fifteenth century and its defeat by the Portuguese in 1511. During the reign of the Sultan Muhammad Shah, Mani Purindan, a Muslim Indian prince from Pahili, arrived in Melaka with soldiers and a fleet of seven ships. The Sultan Muhammad Shah was so impressed that he appointed the prince as one of his ministers. Eventually, the prince married Seri Nara Diraja's daughter. Mani Purindan, a Muslim Indian prince, was the first Kling to win an appointment as a minister of the Malacca court and, furthermore, to marry a Sultan and have a son whose name was Raja Kassim (Abdur-Rahman Mohamed Amin and Ahmad Murad Merican Reference Amin and Merican2014: 180).

Such developments indeed confirm the arguments made by Subrahmanyam that Kling mercantile networks had already been active and influential in Melaka since fifteenth century. Leonard Andaya notes that, even before the Sulalat al-Salatin was composed in Melaka, the term Kling appears in the Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai (The Story of the Kings of Pasai), which was written between approximately 1383 and 1390. Whilst attributing the initial Islamisation of Pasai to dignitaries from Mecca, the Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai tells of the arrival of traders from the “Land of the Keling.” According to Andaya, these were “Tamil Muslim traders” from southern India who, at the time, represented “major economic force in Southeast Asian trade.” Moreover, Indian Muslim connections enabled this Sumatran polity to develop into a leading Malayu centre throughout the fourteenth and early-fifteenth centuries (Andaya Reference Andaya2008: 113).

According to Tschacher, whilst some surmise that Kling specifically denotes Hindus in Portuguese sources from Melaka, scholars should not interpret this usage as a sort of “a priori distinction” between local Muslim and Hindu traders (Tschacher Reference Tschacher2007: 16). Given all this, what, therefore, is the basis of arguing that more Muslims than Hindus from the Coromandel Coast were active in Melaka and Ayutthaya before 1511? Furthermore, upon what evidence could academics analyse the reason for the Hindu demographic expanding via the network of ports and portages after 1511? In his Lendas da Índia, the sixteenth-century Portuguese historian Gaspar Correia notes that the lower-caste Hindu Malabaris were unable to move freely, whilst those who had converted to Islam could travel “freely where[ever] they wished” because they were “outside the law of the Malabaris.”Footnote 12 With regard to Tamil and Telegu-speaking Hindus representing an “interesting anomaly,” James Tracy argues that more Muslims than Hindus settled abroad due to Hindu taboos against “ocean-sailing.” Tracy further contends that prior to 1511, the largest Indian Muslim community in Melaka was comprised of the Kling and Gujaratis and that, notably, the Portuguese regarded the Gujaratis as a potential ally while considering an attack on Melaka that would “push the Gujaratis aside” (Tracey Reference Tracey, Bentley, Subrahmanyam and Wiesner-Hanks2015: 252). Leonard Andaya notes that the size and importance of the Gujaratis population in Melaka is demonstrated by the fact that one of the four official appointed harbour masters liaising with foreign merchants was “assigned solely to the Gujaratis,” who were the “most numerous” (Andaya Reference Andaya2008: 70).Footnote 13 Also, in “The Impact of being Tamal on Religious Life,” Tschacher argues that references to Kling are “too numerous to assume that the term ever referred exclusively to Hindus” (Tschacher Reference Tschacher2007: 25). On this point, Subrahmanyam adds that Portuguese sources sometimes apply both Kling and the generic exonym “Moor” to the same individual (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam, Prakash and Lombard1999: 64), which suggests that these terms may have been synonymous references to groups from the Coromandel Coast. Elsewhere, Subrahmanyam contends that whilst many Gujaratis may have been Muslims, some were not; similarly, the Tamils were a mixture of Hindus and Muslims (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam2011: 146).

Subrahmanyam explains that the term Kling was employed in the Malay world when referring to “Tamil speakers from the Coromandel coast of southeastern India” (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam2011:141). Additionally, the Malay toponym Benua Keling is etymologically related to the term Kalinga. In sixteenth-century Melaka, the term “Kampung Kling” referred to those located in the kampong of Upeh to the right bank of the Kampung River—where these settlers were concentrated. From the seventeenth century onwards, the exonym Chulia was used to denote “Tamil Muslim merchants on the Malay,” which was “possibly derived from Cholamandalam.” After reminding his readers that Suma Oriental is the “standard source” for understanding the place of the Kling in early-sixteenth-century Melaka, Subrahmanyam advises that Suma Oriental should be read alongside both the letters of Rui de Brito Patalim (Melaka's first Portuguese captain) and Portuguese captains of the 1520s (e.g., Jorge Cabral and Pêro Barriga) and Meilink-Roelofsz’ analysis (Meilink-Roelofsz Reference Meilink-Roelofsz1962). References to Klings are indeed scattered throughout Suma Oriental, including the names of ports and polities that traded with Melaka and the local traders who “originate from there” (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam2019: 90).

Reconstructing Indian Muslim Trade among South India, Melaka, and Ayutthaya

The preceding section analysed the exonyms Kling and Khaek in a select body of sources; the previous section also cited reasons why Ayutthaya benefited from Melaka's demise. The Siamese had not only had acquired the ports and portages connecting Ayutthaya to the Bay of Bengal but also had also formed alliances with the Portuguese. Next, this study reconstructs the history of the Kling's commercial activity with the Siamese capital after re-routing trade from the Straits of Melaka.

In his treatment of southeastern India, Pires writes: “These Malabares make up their company in Bonua Quelim which is Choromamdell and Paleacate, and they come [to Melaka] in companies.” However, these people were referred to as Quelins, not Malabares. According to Pires, “Choromamdell and Paleacate and Naõr” were the most important ports, and he provides the following account of Choromamdell:

The first is Caile [Kayal] and Calicate [Kilakkarai], Adarampatanam [Atiramapattinam], Naor [Naguru], Turjmalapatam [Tirumalapattinam], Carecall [Karaikkal], Teregampari [Tarangambadi], Tirjmalacha [Tirumullaivasal], Calaparaoo [?], Conimiri [Kunjimedu], Paleacate.” (Pires Reference Cortesao1944, 103)

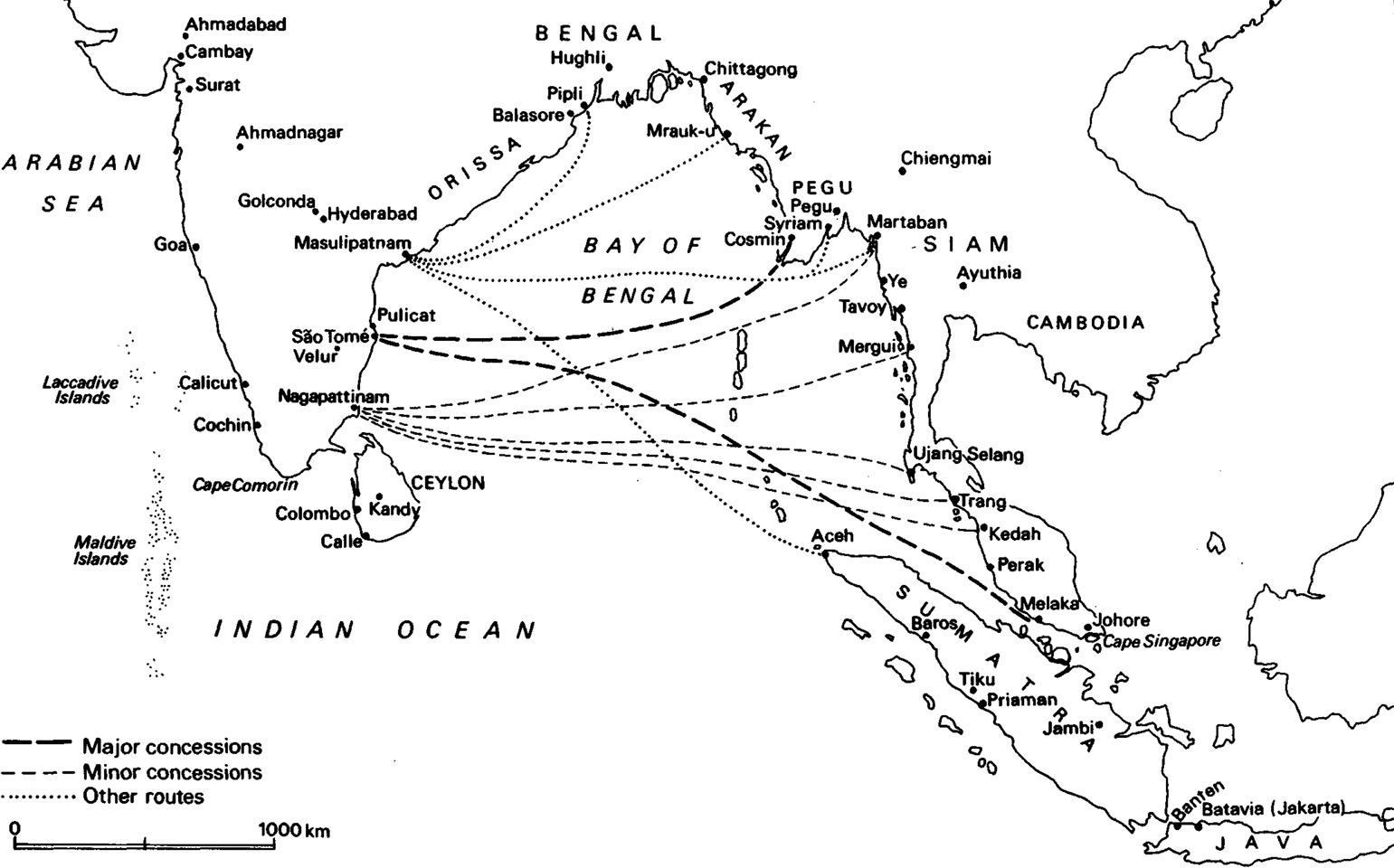

Subrahmanyam notes that most of these routes are “identifiable” and that trade between the Tamil regions and Melaka “centred on the port of Pulicat” (“Paleacate” or Palaverkadu, north of Madras) (see Figure 3). Nonetheless, Subrahmanyam's reference to “Choromamdell” is more ambiguous (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam2011: 142); yet he also writes that it is “fairly clear” that the trade between ports in southeastern India and Melaka functioned as some sort of “funnel”. However, the sixteenth-century details of long-distance trading networks are “obscure” on account of the “paucity of data” (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam1990: 95–96). Coromandel ports were directly linked to the southern parts of the Siamese-Malay Peninsula and northern Sumatra, which received a significant number of imported Coromandel textiles. While the principal port may have been Melaka, Subrahmanyam does not rule out other connections among ports in Coromandel Coast, Perak, and Kedah. Pires also refers to Pase (Pasai) as a “rich kingdom,” possessing “many inhabitants and much trade.” After the Portuguese punished Malacca and given that Portugal is at war with Pedir, Pasai had become “Prosperous, [and] rich, with many merchants from different Moorish and Kling nations” who did a “great deal of trade.” The most important of these trading partners were the Bengalees, which are mentioned in Pires's brief description of Siam, but Pasai also identifies “Rumes, Turks, Arabs, Persians, Gujaratees Kling, Malays, Javanese and Siamese” (Pires Reference Cortesao1944: 103). This anecdote suggests that Northern Sumatra was one of the corners of the Bay of Bengal in which the Kling may have formed commercial alliances with Siamese traders.

Figure 3. Concessionary routes across the Bay of Bengal (Source: Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam1990: 150)

Again, the ethno-religious and ethno-linguist identity of some of the actors involve in trade among South India, Sumatra, and the Thai-Malay Peninsula is “something of a puzzle.” For example, mercantile communities in sixteenth-century Pulicat were “mixed’ and “cosmopolitan”; local communities lived in “separate and demarcated quarters in the port town in a manner typical of the period, and reminiscent of the well-known layout of such mercantile towns as pre-Portuguese Melaka.” This study argues that the major traders in Pulicat in the period were Muslims (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam1990: 96). The ideal way to reconstruct trade routes across the Bay of Bengal during this period is to consider specific case studies from secondary literature.

Consider, for instance, an Italian man named Niccolo Da Conti whose travels in the 1420s included the Bay of Bengal and who recorded the great wealth of South Indian traders. Per his writing, the traders’ wealth was demonstrated in that they conducted their own business with a fleet of “forty of their own ships,” each of which was valued at “fifty thousand gold pieces” (Hall Reference Hall2009: 128). In “The Chulia Muslim Merchants in Southeast Asia, 1650–1800” (1996), Sinnappah Arasaratnam notes that over and above the “direct import-export trade between Siam and Coromandel in textiles, sappan wood, hides, elephants, tin, ivory and gold,” Ayutthaya functioned as a “meeting point for the China and Japan trade [network].” Accordingly, Coromandel merchants may have acquired Chinese and Japanese goods, such as “copper, zinc, lead, alum and radix-china,” but they also sought entry into Cochin-Chinese and Japanese markets through contacts with “Chinese Muslim merchants coming to Ayutthaya.” Additionally, Arasrartnam recounts Dutch reports of “Moors” on Chinese and Japanese ships in the South China Sea, sailing from Ayutthaya to unknown destinations. In fact, one ship was wrecked in Tonkin and ten survivors who were Coromandel “Moors” were “repatriated to Coromandel”; furthermore, Arasrartnam raises the possibility that some may have been Chulias (Arasaratnam Reference Arasaratnam, Subrahmanyam and Aldershot1996: 131, 165).

Portuguese accounts of “Keling/Chulia trading networks post-1511” make it possible for scholars to “reconstruct good parts” of the local picture of trade during this period. For one, Subrahmanyam considers the fascinating case study of the commercial activities of a certain man named “Setu Nayinar” between 1513 and 1514. The detail that this study is interested in is that the man sent two ships to Siam through his “partnership with the Portuguese Crown”—specifically via a certain Rui de Araújo (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam2011: 142, 143, 146). Moreover, Setu Nayinar “concentrated largely (albeit not exclusively) on the textile and rice trade of the littoral ports and regions of the Bay of Bengal.” In addition the Coromandel Coast, this route also included “both Bengal and Pegu” (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam2011: 143). What is more, before the Iberian invasion “Tamils and Gujarats” dominated both “numerically and in terms of economic and political power.” Furthermore, the Portuguese narrative claims that, upon their conquest of Melaka, “Gujarati merchants fled the port in large numbers.” In contrast, the Tamils “largely remained” (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam2011: 146). He adds that some Tamil merchants—including the aforementioned Setu Nayinar—may have also supported the Iberian invasion. Either way, they had been “well-placed to take advantage of the situation” (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam2011: 146).

Nevertheless, “If the great Keling merchants such as Setu Nayinar had imagined in late 1511 that the new regime would share power in a reasonable arrangement with them, they were soon disabused of this idea”:

Initially, the Kelings had much to offer the Portuguese and they did so, notably in the form of sharing crucial commercial information by way of the “joint-venture” voyages they undertook with the Portuguese Crown to ports such as Martaban and Pulicat. But this was clearly an affair with diminishing returns, and once the Portuguese factors had grasped some of the tricks of the trade, it was clear that such ventures would cease, at least in their initial form. Further, the Portuguese power structure itself was deeply fragmented, and Setu Nayinar’s close alliance with Rui de Araújo, for example, meant that he was not necessarily well-placed after the latter’s death with regard to other Portuguese actors. (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam2019: 96)

This poses an important question: Had all Muslim traders actively avoided the Straits of Melaka after the Portuguese arrived and piracy increased? Indeed, the secondary literature suggests that some tweaks are necessary. Some Indian merchants trading among the Coromandel Coast, Melaka, and Siam worked with—as well as benefited from—the Portuguese in Melaka. Moreover, the mercantile communities from the Coromandel Coast were the winners and the Gujaratis were the losers. As Andaya notes, the Coromandel Coast communities had the advantage because of their large population and their involvement in defending Melaka. Arun Dasgupta refers to Gujaratis as being “bitterly opposed [to] Portuguese penetration” because they wished to preserve the “freedom of high-seas navigation” so they could control trade in the middle Indian Ocean.” Finally, having been marginalised by the Portuguese, the Gujaratis moved their operational base to Aceh (Dasgupta Reference Dasgupta, Raychaudhuri and Habib1982: 426).

What, therefore, could one rightly conclude from Subrahmanyam’s case studies of the Kling who engaged in these trading networks, including Ayutthaya? In Cross-cultural trade in world history (1984) Philip Curtin rejects claims that the Portuguese destroyed existing trade networks; rather, Curtin contends that Iberian naval power “reinforced certain trade opportunities,” and either “suppressed or distorted others (147).” Further, Curtin suggests that the Portuguese's anti-Muslim bias is what led them to attempt to regulate trade across the Bay of Bengal. While continuing to trade with Muslim Gujaratis in some places, they in fact wanted “Muslims out of the trade between India and Southeast Asia.” One way to accomplish this was to encourage Kling merchants from the Coromandel coast to “take their place” (Curtin Reference Curtin1984: 147). This explains why Kling traders came in greater numbers to Ayutthaya, although eventually the Portuguese's need for additional local business allies led them to revisit this policy, which in turn led some Kling relocating to Melaka (See Hall Reference Hall2009: 129). From the 1530s, the spice trade from local ports controlled by the Portuguese to the Red Sea revived significantly, forcing the Portuguese to revisit its “anti-Islamic posture” in favour of a policy that would lure “Muslim shipping back to that port.”

Conclusion

Muslim communities in Ayutthaya had already grown in population before the Persians and Indo-Persians arrived in the seventeenth century. While there may have been relatively few Muslims in Ayutthaya at the beginning of the sixteenth century (who were disliked by the Siamese), Tomé Pires (in addition to Arabs, Persians, and Bengalese) comments that the Kling—who were locally referred to as Khaek—were numerous. Such mentions of the Kling in sixteenth-century Ayutthaya are reminders that, when it comes to the Islam's spread locally, there were more than Arabs or Persians involved.Footnote 14 During the reigns of King Ramathibodi II (r. 1491–1529) and King Chakkraphat (r. 1548–1569), local disciples of the Indian Tok Takia established Ayutthaya's earliest shrine (Ar. Maqam) to their Sufi Sheikh approximately a century before the Tok Panyae shrine was established in Patani during Rajah Biru's eight-year reign, which ended in 1624.

In the mid-sixteenth century, Mendes Pinto described Ayutthaya’s cosmopolitan cohort of Muslim missionaries as having established at least seven mosques, which served thirty thousand Muslims. Notably, one of the mosques was associated with the Tok Takia Shrine and, perhaps, benefitted from Chairacha’s hands-off attitude towards Ayutthaya’s growing religious cosmopolitanism. The focus of recent work by scholars, such as Matthew Reeder and John Smith, has been the ethnic elements of Siamese cosmopolitanism. For example, they argue that some of the Khaek appearing in late-sixteenth-century Siamese sources that mandated the management of Ayutthaya’s increasingly diverse mixture of sojourners and subjects were Khula, which may have referred to Tamils.

This study has argued that the growth of Ayutthaya’s ethnically diverse Muslim communities during the sixteenth century can rightly be explained by the range of diplomatic manoeuvrings, geopolitical ruptures, and trade re-routing after the Iberian invasion of Melaka in 1511. These factors confirm the veracity Feener's argument that the Portuguese had contributed unintentionally to creating new Muslim communities in Southeast Asia. They also confirm Chris Baker's insistence that Ayutthaya's strength arose from maritime trade via the Bay of Bengal, not via agriculture. In other words: Ayutthaya's prominence as polity is deeply connected to Melaka's fall. After Ayutthaya gained control of the most important ports connecting it to the Bay of Bengal; although a mixture of Tamil- and Telugu-speaking Indians (who were mainly Muslim) may have traded with Ayutthaya, it was in fact Kling merchants (e.g., Setu Nayinar) who comprised the greater number of traders after 1511. Furthermore, greater awareness of commercial opportunities in Ayutthaya (including textiles) facilitated by military, diplomatic, and commercial alliances between the Siamese and Portuguese increased contact between the Kling and Siamese across the Bay of Bengal—including North Sumatra. Reasons behind the increasing interest in trading with Ayutthaya amongst Muslim Kling range from their desire to avoid Melaka, using a more direct trading from the Coromandel Coast, and exploiting the cooperative relationship between the Siamese and Portuguese.

In addition to these empirical findings, this study also demonstrates the utility of both exploring the synergy among South Asian, Southeast Asian, Thai, and Malay Studies and analysing the exonyms employed in primary and secondary sources. Feener’s approach to Southeast Asian Islam in tandem with Baker’s wide-angle and longue durée lens to Thai Studies led this research to trawl for, introduce, aggregate, and analyse a mixture of the few primary sources that exist and the extensive array of secondary sources. The lack of extensive primary sources should not stymie religious historians in researching and publishing on overlooked periods, places, and actors. In fact, by homing in on such frequently imprecise exonyms, scholars can highlight the contributions of Indian Muslim in ways that profile the Khaek as overlooked pioneers in establishing a Muslim presence in sixteenth-century Ayutthaya. This study, by seeking greater synergy among diverse scholarly silos, has brought into greater focus the presence and impact of Kling Muslims in early-modern Siam before the Persians and Indo-Persians arrived from across the Bay of Bengal. Although the Persians that Pires mentions, along with Bengalis and Arabs, were present in Ayutthaya at the beginning of the sixteenth century, this study contends that other actors, specifically Muslim Kling, had a significant impact on the ethnic and religious characteristics of Siamese cosmopolitanism during the early 1550s.