Formerly Medical Director, American Psychiatric Association

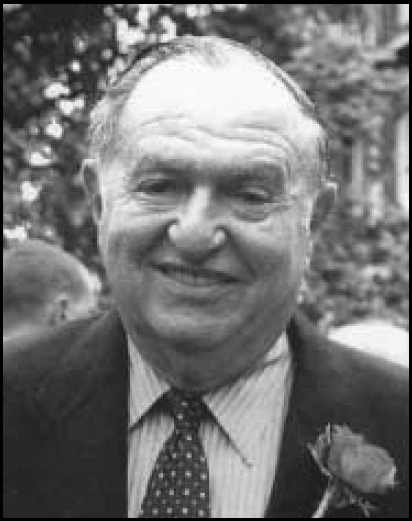

To capture Melvin Sabshin in a short obituary is almost a contradictio in terminis. Those who knew Melvin Sabshin invariably remember his imposing stature, his supreme intellect and his analytic and ever questioning mind, as well as the typical broad smile on his face and the big cigar stuck in the corner of his mouth.

Melvin Sabshin, former Medical Director of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and, among many honors, an Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, died on 5 June 2011. He had his roots in Russia, which may explain his keen interest in the issue of Soviet political abuse of psychiatry in the 1970s and 1980s. At the beginning of the 20th century, his parents, who remained socialist activists throughout their lives, emigrated from an area that is now in Belarus, fleeing from anti-Semitism under the Tsar. Born in 1925, Sabshin grew up in New York. Being a brilliant student, he graduated from high school in 1940 shortly after having turned 14. Then, after active lobbying by his mother, he was admitted to the University of Florida, from which he graduated in 1943 at the age of 17.

In 1944, Melvin Sabshin entered Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana, after having spent 1 year in the US Army as a volunteer. Here he became politically active in the civil rights movement, defending equal rights for Black people (for instance, by refusing to enforce separation between White and Black donors at the blood bank at Charity Hospital in New Orleans) and eventually even joining the American Communist Party, a fact he kept concealed until I interviewed him for the first time in February 2009. It was a typical Melvin Sabshin situation: when I deducted this from a sequence of hints he made in the course of the interview and asked whether he had been a member only in spirit or also factually, he was visibly pleased that I had caught his hints, and answered with the usual big grin on his face: ‘You could say: both’. His membership, which he ended in the early 1950s when he became disenchanted with the political course of the party, haunted him well into the 1970s when he was already at the APA. His file at the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is 400 pages’ thick and documents the intense scrutiny by the FBI, his dishonorable discharge from the US Air Force as being ‘politically unreliable’, the interrogations by the FBI in the late 1950s, and the fact that he was not allowed to join government commissions even when being medical director of the APA because of his political past. Even a planned visit to the White House in 1974 made the FBI carry out another investigation.

The FBI pressure made him move to Chicago where, in spite of FBI resistance, he became director of the Institute for Psychiatric and Psychosomatic Research and Training in Michael Reese Hospital and later also acting dean of the Medical School of the University of Illinois. Here he met his second wife, Edith Goldfarb, a trained psychoanalyst like himself, who became his constant and loving companion until her death in 1992. Edith’s death left him deeply depressed and disoriented, until he met and married Marion Bennathan in 2000, with whom he spent the rest of his life living mostly in London, and who cared for him with much love and affection until his death.

In 1974, Melvin Sabshin moved from Chicago to Washington DC, after having been appointed medical director of the APA. Under his 23 years of leadership, the APA would become the most powerful psychiatric empire in the world. Although the president rather than the medical director was formally the chief executive officer of the organisation, during his tenure as medical director Melvin Sabshin became, in fact, the intellectual leader of the psychiatric profession in the USA. During his tenure, Sabshin was instrumental in developing one of the largest psychiatric publishing houses (American Psychiatric Publishing) and in developing and promoting one of the leading classifications of mental disorders, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM); DSM-IV is dedicated to him as a sign of his involvement: ‘To Melvin Sabshin, a man for all seasons.’

During his time at the helm of the organisation, the APA became probably the most revered organisation in international psychiatry, with Ellen Mercer directing the Office of International Affairs and greatly expanding the APA’s international network, for instance developing links with China. Many older psychiatrists worldwide remember this period as the heyday of the APA, when its annual meetings were considered the most interesting international events in world psychiatry.

From 1983 to 1989 Melvin Sabshin also functioned as a member of the Executive Committee of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), the main psychiatric body that unites psychiatric associations around the globe. Here he showed his unique diplomatic skills, meandering through the minefield of, on one hand, supporting the fight against political abuse of psychiatry in the USSR (the reason why I met him for the first time in the early 1980s), on the other hand the realities of being on the board of a global organisation including those who did not support his position vis-à-vis the USSR, and the challenge to promote improved mental healthcare worldwide. Typically of him, he befriended both those who vehemently fought Soviet psychiatric abuse and, at the same time, the East German member on the same WPA executive, Professor Jochen Neumann, with whom he remained close friends until his death. He was instrumental in finding the final compromise in 1989, which led to the return of the Soviets to the WPA from which they had been forced to leave in 1983, without giving up his ethical stand and his support for human rights.

During the last years of his life, physical ailments increasingly impaired his ability to move around and participate in professional life as actively as he would have liked. However, his mind was unaffected, and when needed, he would gather all his strength and dominate the discussion. In 2008, he published his memoirs, Changing American Psychiatry, and during the subsequent 2 years we met frequently while working on my book, Cold War in Psychiatry, in which he figures as one of the two main characters (the other being his friend Jochen Neumann). He often left me wondering who determined the course of the long interviews. In fact, he quickly made the project to a large degree his own, all the time pushing me to dig deeper and to find better answers to difficult questions. It was an exhilarating period that unfortunately came to an end when the book was finished.

The last time we met was during the presentation of the book in October 2010. Frail, hardly able to walk, exhausted, he gathered all his strength during the presentation, quickly taking the lead and turning the discussion to his favourite subject - the DSM classification, in which he strongly believed and which, in his view, had been one of the important tools in curbing and finally ending the political abuse of psychiatry in the USSR.

Melvin Sabshin is survived by his wife, Marion; his son James Sabshin MD, a neurosurgeon; four granddaughters, two of whom are psychiatrists, and by many friends all over the globe. He truly was a unique personality.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.