In 2018 I invited the indigenous leaders Ailton Krenak and Davi Kopenawa to collaborate and coauthor the scenic experiment Silence of the World. The idea for the performance came from an expanded artistic research project on how to make a connection between theatre and the indigenous world. It’s worth saying that Ailton Krenak is one of the most important intellectuals and emblematic leaders in Brazil; he expresses a profound reflection on the anthropocentric perspective as exclusivist, placing humans at the center of the world. His ideas cross several fields dealing with human existence, society, knowledge, and artistic practice. Equally important, Davi Kopenawa is considered one of the main Yanomami leaders and shamans; he was one of those responsible for the demarcation of the Yanomami Indigenous Land, and is known worldwide for his relentless fight for the survival of the Amazon forest. So, when I decided to invite two of the most important indigenous leaders in Brazil to enter the space of the performing arts, I did so based on principles established after expanded discussions about theatre and the indigenous world and through a deep relations of partnership and friendship with indigenous people that I have been building for over 20 years (see Duarte Reference Duarte2020).

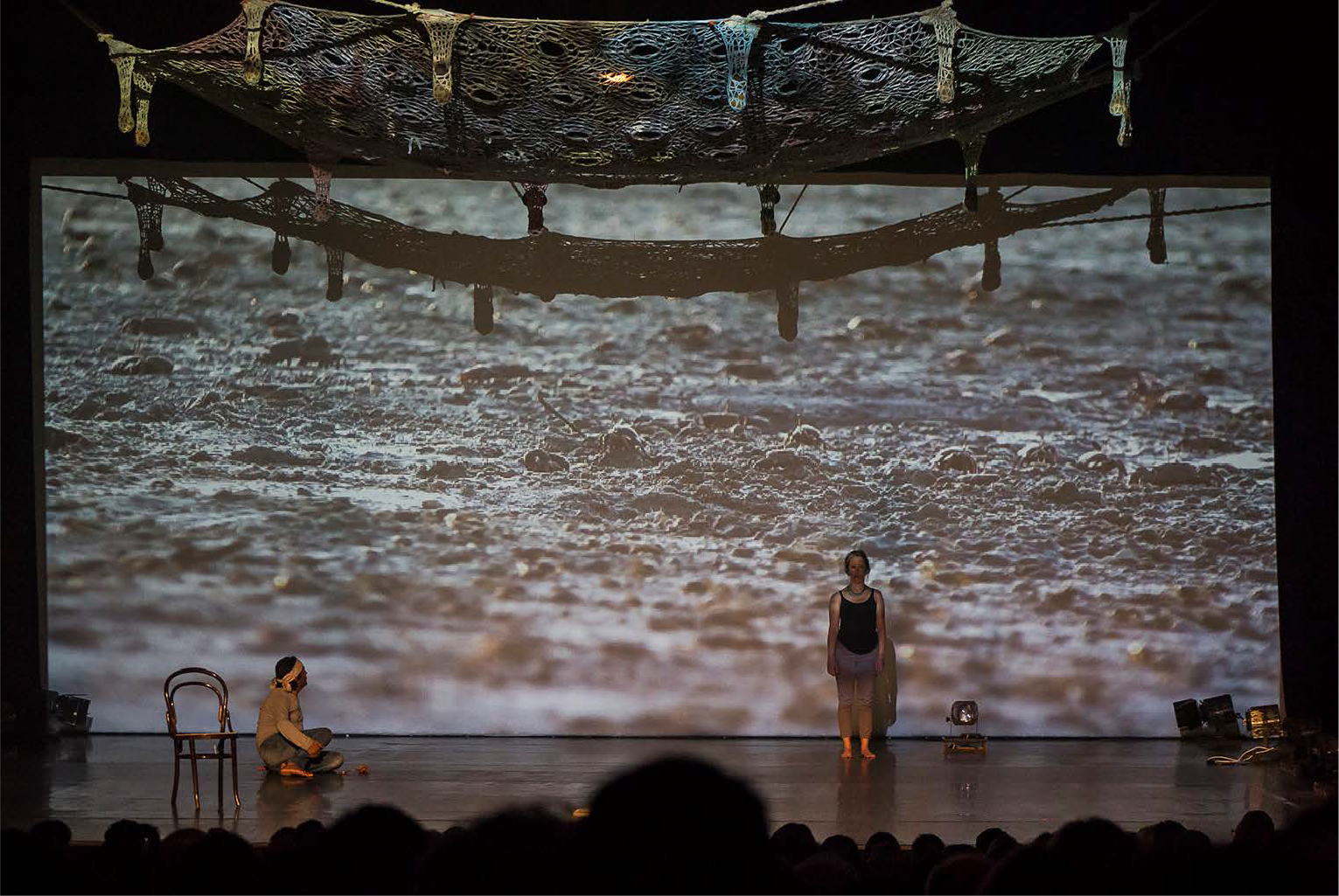

Figure 4. Scene 2: The Time of the Myth. Silence of the World at the 27th Porto Alegre em Cena, International Festival of Performing Arts. (Courtesy of Fernando Zugno)

Our meetings took place on the occasions when Krenak and Kopenawa came to São Paulo to attend events as guests of different institutions. I took the opportunity to listen to their speeches, reflect on and learn from their ideas, and make room for us to get to know each other better by creating opportunities for exchange. The truth is that it would be very difficult to achieve an ongoing dialogue if I were living somewhere other than São Paulo, which, being a large economic and cultural center of the Brazilian art market, frequently provides for indigenous representatives to come to the city. But the size of Brazil makes traveling difficult, as does the fact that each of these leaders lives on opposite sides of the Brazilian territory: Ailton Krenak lives in the Krenak Indigenous Land in the state of Minas Gerais in the Southeast Region; and Kopenawa lives in the Yanomami Indigenous Land, which occupies the states of Amazonas and Roraima in the North Region.

The experience of observing and listening to the lectures of these leaders heightened my perception of how they express their thoughts and understandings of their origin by bringing speech closer to other bodily expressions. In the middle of one speech, after talking about the whole colonial process that culminated in the death of the Rio Doce,Footnote 14 Krenak stopped, took out a maracá from inside his bag, and started to sing and dance. When he finished, he looked at the audience and said, “These things make me so upset, so shocked, that I have to stop and sing.” That simple unexpected act put me in a state of suspension. It was as if Krenak had forced everyone there to stop and breathe, while also teaching us to resist engaging in violent verbal exchanges and instead to accept that there are other ways to help us communicate and encourage our well-being in the midst of so many difficulties.

Something similar happened right at the beginning of a lecture given by Kopenawa: he sat down on his chair, looked at his audience, and began to speak in Yanomami for about 15 minutes. It was so interesting to be in that situation. It created discomfort in the audience that was there to hear his speech but could not understand anything he was saying. This choice showed the integrity of Kopenawa as a leader as he communicated with gestures and speech coming from his own language. Simultaneously, it created a tension that made me think about the imposition of coloniality on the value of the official Portuguese language.

It reinforced my awareness that we are in a country that was built on the diverse indigenous peoples who to this day speak their own languages; many of these living and unique cultures still suffer from a continuing process of erasure in the formation of Brazilian society. Kopenawa recreated in that space and for the public the feeling that he and the native peoples suffer when they are forced to speak another language in order to build relationships that can contribute to their lives outside of their villages.

Krenak’s and Kopenawa’s aesthetic and political attitudes disrupted the conventions of the lecture, which, the way I see it, resulted in an expanded presence. As I accompanied them, I realized both leaders acted as they did to express their thoughts, and that those actions embodied an aesthetic that originated in their cultures, and at the same time made political statements related to their social contexts. Krenak sang about the painful death of the Rio Doce that happened as a consequence of unbridled capitalist development. When Kopenawa gave the speech in his native language, he attested to the live presence of Yanomami people in the face of so many threats to their survival.

During the same period when I was meeting with these leaders, listening to their speeches, and observing their activist practices, Krenak and I initiated the art festival TePI (Theatre and Indigenous Peoples; Outra Margem Reference Margem2021). The inaugural event took place in 2018, and the second festival was programmed for 2020 but had to be canceled due to the Covid-19 global pandemic. TePI’s goal is to place center stage artistic productions by indigenous artists who express their work through their bodies. The festival also seeks to be in dialogue with productions that, on principle, understand that humans are not separated from nature. Instead, we are all integrated with nature, and the planet is a site for the collective survival of all that exists: humans and nonhuman entities such as animals, plants, mountains, bacteria, etc. It is about deepening the understanding that we are only one species and that we all have the common responsibility for the survival of the Earth. The way we see it, it is important that this concept permeates all fields of knowledge and manifests everywhere, including in works of art.

We used to say fazermos juntos porque decidimos fazer — doing it together because we decided to — which, in the context of our creative process, expressed the need to join indigenous and nonindigenous artists in a common movement. This is how we came up with the idea for Silence of the World as a scenic experiment to be performed on stage for a nonindigenous audience, where Davi Kopenawa, Ailton Krenak, and I could propose actions that would exemplify, aesthetically and politically, the perception of a life connected with everything in the world and that is nature.

For me, there was something very coherent about doing this experiment. I lived with the Kamayura people who speak Kamayura language and inhabit the Xingu Indigenous Park, located in the Central-West Region of Brazil in the state of Mato Grosso, from 2001 to 2005; since then, I have sought to relate my various practices as an artist to my experience of indigenous existence intersecting with my path and deepening that experience by creating actions collaboratively. I am not interested in temporary research, which often runs the risk of appropriating aspects of specific cultures for nonindigenous artistic creations. Mine is part of a larger purpose over a longer time period; I seek to create artistic works that value human diversity and encounters between alterities — artworks that are part of my activism against all kinds of violence generated by the colonial process. As part of this effort, it was an honor to create a show next to these indigenous leaders, Ailton Krenak and Davi Kopenawa, two people who have transformed my being.

Another project objective was to increase the visibility of indigenous people in the market of national and international festivals, as well as in cultural institutions, where only recently there has been a greater presence of contemporary indigenous art. There is still scarce recognition of indigenous theatre production in Brazil, and indigenous people are only occasionally invited to take part in works by nonindigenous artists. So, Silence of the World also intended to call attention to the relevance of indigenous people’s practices to the field of performing arts, such as devising a performance that sought horizontality in the creative process and the sharing of authorship.

Both Krenak and Kopenawa had already participated in other artistic projects — including films, music albums, festivals, radio programs, exhibitions — when they accepted my proposal to get together and create art actions. As they both have very full schedules, I proposed staging three experiments to be performed at different times, each one with a week of meetings followed by a presentation of the results. It was also important to take into consideration the economic aspects of producing a performance that involved two prominent indigenous leaders and complicated logistics. Even so, we believed in its realization.

During Krenak’s visit to São Paulo, we went to Pinacoteca, the oldest art museum in the city, to visit Ernesto Neto, a visual artist whose exhibition Sopro was installed there (Artequeacontece 2019). The three of us walked together to the park next to the museum, sat on the exposed roots of a tree, and talked about the making of Silence of the World. At Krenak’s invitation, Neto agreed to create an artwork to be installed over our heads onstage: his rendering of a sky that refers to the monumental book The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman by Davi Kopenawa and French anthropologist Bruce Albert. At this meeting, Krenak explained his thoughts about the work and later reinforced the same idea in writing:

The action would be to make the “white woman’s body” disappear on the scene, with the entrance of the WORLD element, which dilutes the stabilized division between human and nonhuman, extinguishing the notion of gender and race as a given term in interpersonal relationships. A deconstruction exercise of the anthropocentric discourse that stabilizes the human body as the measure of things and defines gender and race, savage and civilization, Indian and white. (Krenak Reference Krenak2021)

The idea of moving the human body out of the center of the world was foundational to our creative process. We deepened our conversation about the silencing of the planet as the lifeforms that inhabit it die. If even one species can die off, this means that humanity as a species can also be silenced. But, as Krenak explained during the creative process, “humanity may end, but nature will always have the potential to create other forms of continuity.” We decided to perform our scene as a way to invoke the presence of communities of nonhumans, provoking humanity to reconnect with the Earth as an organism and to get out of the mindset that presumptuously denies the plurality of life forms (Krenak Reference Krenak2020:82). We suggested building this path through the experience of our encounter, during the creative process, and, as it happens in indigenous education, through conversations, lived experience, repetition, and observation.

In 2019, we got approval for the first experiment to take place at the Festival Porto Alegre em Cena. We had already confirmed our participation, but at the last moment, unfortunately, Davi Kopenawa had to cancel because his father-in-law had just passed away and he had to undergo a long period of seclusion and attend to activities involved in the mourning of his people. Krenak and I decided to go to POA em Cena, but decided to invoke Kopenawa’s presence by bringing to the scene fragments from our time with him. This is why we began the performance by reading to the audience a paragraph from the book The Falling Sky, in which Kopenawa shows the importance of his father-in-law in his formation as a shaman (Kopenawa and Albert Reference Kopenawa, Albert, Elliott and Dundy2013:256).

On the first day of our immersion, we spent more than eight hours talking and elucidating the ideas that would be communicated to the audience. We decided to work with the notion of the time of the myth, as developed by Krenak (in Souza e Silva Reference Souza e Silva2018:4). This concept figures myth as an ancestral space, where all existences are aware that they are a part of the same community. It is a dimension that opens a gap where everything is possible, when life is created and transformed in each moment. This is how the relationship between humans and nonhumans begins, emerging in everyday life, in ritual; where we face dangers and form alliances. This happens, for example, when snakes start communicating with people, jaguars marry women, frogs pray inside villages that threaten all life within them, men turn into birds to court females, women fall in love with beautiful alligators that later turn into trees, rivers are created with their bends, mountains communicate with communities, storms get out of control, and the sky is supported by pillars, putting the planet at risk and in balance (see Kopenawa and Albert Reference Kopenawa, Albert, Elliott and Dundy2013; Krenak Reference Krenak2019; Kamayura and Kamayura Reference Kamayura, Kamayura and Duarte2013).

Figure 5. Scene 2: The Time of the Myth. Silence of the World at the 27th Porto Alegre em Cena, International Festival of Performing Arts. (Courtesy of Fernando Zugno)

I think it is relevant to say that Krenak does not put forth this concept as something that is complete; it is part of a living memory that constitutes an environment visited all the time as a reference point for identity, place, and indigenous knowledge. This shows how original peoples live their ancestrality, putting their collective knowledge in motion in the present and thus laying the foundation for the future. The point of view of this living movement, here and now, reveals that indigenous people remain integrated with nature and do not make a distinction between body-human and body-world.

From this understanding, we started creating the scene in which Ailton Krenak, the Krenak leader, presented the time of the myth to the audience, while my body was subsumed by the image of a community of crabs projected onto the screen behind me. For us this evoked a sense that there was no separation between the white person, the woman, the indigenous person, the man, and the crab, but that everything is combined as part of the singular movement that is life. Further, we integrated my memories from when I lived with the Kamayura people to show the reality of the time of myth in that community. It is unimportant if the myth is real or fictional; what is important is to realize that it is a space of uncertainty in which there is no expectation of a secure future or a programmed life that desperately tries to postpone death. As one can read in the performance script, Krenak tells the audience that there is no guarantee of duration, but a magical dimension opens a window for us to cross over and go out into the world, interact, and fulfill ourselves.

Working alongside Krenak, Silence of the World made me think about the connection between worlds that we can build through artistic creation. It was interesting to note that, at the same time that we were talking about myth opening to possibility and to the invention of the world, we were in the process of imagining a new place. The scene emerged as a space of suspension, as we began to cross thoughts of the indigenous world with images, sounds, and memories in a construction that presented the audience with other ways of being, other senses. This is how we entered into the gap between the time of the myth and our presence, at a moment when we were willing to sing and dance to suspend the sky, without concerning ourselves with any thought of an end. We pushed this movement forward when we showed the young environment activist Greta Thunberg as a call to action for those who believe in transformation, as someone who inspired demonstrations against climate change and helped organize a worldwide movement. And when we showed Krenak in the 1980s, personifying the mourning of the indigenous peoples by painting his face black in front of several members of parliament, a gesture that is now part of the history of the formation of the Brazilian Constitution.Footnote 15 And again when we paused…listening, seeing, touching; when we lay still under a diagonal light and listened to the rain falling; or stood still, just feeling.

The closing of the scenic experiment happened at the moment when we acknowledged that even after having gone through so much destruction of the world, and despite the arrogance of anthropocentrism, there are still people who mediate with the planet: those who are considered subhuman, people who cling to the Earth and, thus, are forgotten on the edges of the planet, on the banks of rivers, on the shores of oceans — caiçaras, indigenous, quilombolas, aborigines (Krenak Reference Krenak2020:82). This is how Krenak invoked Davi Kopenawa again, calling to the scene the thunder and the rain, as well as invoking the presence of the mountain that embraces the Rio Doce, the Takrukrak mountain, a sacred entity for his people:

I learned that the mountain has a name, Takrukrak, and a personality. In the morning, from the village yard, people look at her and know if the day is going to be good or if it is better to stay quiet. When she has an “I’m not up for a conversation today” face, people are attentive. When she dawns splendid, beautiful, with clear clouds over her head, all adorned, people say: “You can party, dance, fish, you can do whatever you want.” (Krenak Reference Krenak2019:18)

Doing it together because we wanted to, we were driven by a creative process that brought with it an attempt to free ourselves from traditionalist ties about what art is, presenting a result made in a few days in the format of a lecture-performance. This was also possible due to the strength of the people involved in the festival: the programmer Fernando Zugno, who knew how to listen and believed in the project. The performance took place on the stage of the city’s main theatre, the 100-year-old Theatro São Pedro, which had a capacity of 700 and sold out to an audience ranging from young people to elders, college students, professors from different fields, artists, journalists, representatives of the Kaikang and Guarani indigenous peoples, and a vast audience curious about what would happen on that traditional stage. After the performance, we received great affection from the audience and positive responses in different newspaper articles. In his column for the Jornal do Comércio newspaper, theatre critic Antônio Hohlfeldt wrote:

But how to explain a show as deeply moving and creative as Silence of the World, conceived by Andreia Duarte and Ailton Krenak? That Thursday night was the highlight of the festival this year. The handmade net stretched over the heads of the performers; Ailton’s simplicity and Andreia’s dedication touched all of us who were there. In fact, it was as if we were all gathered around the original fire that night, listening to the noise of the past that the silence of the present wants to destroy. (Hohlfeldt Reference Hohlfeldt2019)

Finally, we were aware that we were provoking a fusion between real and fictional references, as well as between different scenic languages, such as lecture, video, and performance. We also knew that there was an ephemerality in everything that was happening, even in the very uncertainty of creating a performance in one week. Silence of the World was a unique event. Due to technical problems, the festival was unable to make a video recording. The only records that remain of the process are the ones in my notebook, memories, newspaper articles, and scenic materials. More recently, Krenak and I attempted to reconstruct the script. In any case, it has been very interesting to see how the work has been coming back by itself. Every now and then there someone asks questions, seeks information — wants to know a little more. I think that in a certain way Silence of the World created a life of its own, a life that marked our bodies and continues to animate us. Will it happen again, in another place, at another time?