Introduction

Cognitive therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder (CT-PTSD) is an internationally recommended treatment (International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies, 2019; National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence, 2018) based on the cognitive model of PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). Identifying and updating the personal meanings of traumatic experiences is central in successful CT-PTSD. Therefore, when traumatic experiences involve racism, it is key that therapists delivering CT-PTSD feel confident in discussing, unpacking and addressing patients’ individual meanings. Note that racism can be experienced in varying forms and this paper cannot address all the various types of racism including structural, institutional, interpersonal and internalised, nor the cumulative impact of these. Interpersonal traumas involving racism, however, are not unusual. A recent UK study (Ellingworth et al., Reference Ellingworth, Bécares, Šťastná and Nazroo2023) found that over a third of respondents from a minoritised ethnicityFootnote 1 had experienced a racist assault (insults, property damage or physical attack), with this rising to over 60% for some ethnicities; 15.5% of respondents reported having experienced a racist physical assault. Racism has also been linked to higher maternal mortality rates for Black and Asian women during labour (Ayorinde et al., Reference Ayorinde, Esan, Buabeng, Taylor and Salway2023; Kapadia et al., Reference Kapadia, Zhang, Salway, Nazroo, Booth, Villarroel-Williams, Becares and Esmail2022; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Bunch, Felker, Patel, Kotnis, Kenyon and Kurinczuk2023). However, in our experience some therapists can often avoid asking about racism for a range of reasons, including lack of understanding of racism and its impact, low confidence in talking about ethnicity or racism, or being unsure how to integrate this into the formulation and treatment. The aim of this paper is to provide clinical guidance through case illustrations to support therapists’ sensitive delivery of CT-PTSD where racism has been involved. We hope to help therapists feel more confident in identifying and working with common appraisals related to racism. This may be of particular relevance if the experiences and identities of the therapist and patient are different. We will first present three case examples used to illustrate key interventions and then delineate key considerations regarding:

-

(1) The Ehlers and Clark model of PTSD;

-

(2) The delivery of CT-PTSD;

-

(3) Supervisory implications.

This guidance is based on our experiences delivering CT-PTSD where racism has been part of an index trauma event(s) with reference to diagnostic Criterion A in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). This currently requires exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence via directly experiencing the event, witnessing the event occurring to others or learning that the event occurred to close family or friend. It can also involve repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of a traumatic event (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). There is, however, significant and growing evidence for cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in wider presentations where experiences of racism are part of ongoing traumatic stress and the symptoms would not meet the narrower definition of PTSD (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Holmes, Zare, Haeny and Faber2023). There have also been debates around the narrowness of Criterion A (Marx et al., Reference Marx, Hall-Clark, Friedman, Holtzheimer and Schnurr2024) with some calls to widen this to account for more insidious forms of traumatic experiences, such as societal oppression and regular microaggressions (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Facemire and DaFonseca2016). This clinical guidance paper does not attempt to address these important debates around the social construction (and changing criterion) of Criterion A. However, it is likely that elements of this guidance could be potentially useful even if the current definitions of Criterion A and PTSD are not met. Current evidence suggests that there is not always a direct link between whether an event met Criterion A and the prevalence and severity of PTSD symptoms (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Osman, Gallo, Pereira, Gran-Ruaz, Strauss, Lester, George, Edelman and Litman2022). There is also a degree of subjectivity to Criterion A which is influenced by both the previous experiences of the patient but also aspects of their identity. If Criterion A appears not to be met, Murray (Reference Murray2023) has suggested considering differential diagnosis but also potential reasons why the event may have been experienced as highly threatening (e.g. earlier experiences, core beliefs).

An essential point is that we are not minimising the impact of experiences of racism when the current diagnostic criteria for PTSD are not met. In fact, quite the opposite, we would suggest that therapists need to find ways to integrate experiences of racism into disorder-specific formulations and treatments for all disorders when relevant to the patient. For a further example of this, see Chapman’s work on integrating experiences of racism into CBT for social phobia (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, DeLapp and Williams2013a; Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, DeLapp and Williams2013b).

It is important to highlight that due to the nature of the topic, the article will include discussion around experiences of racism and as such certain examples may have an emotional impact; we would encourage appropriate caution and self-care associated with reading this material.

Author positionality

Part of being able to talk comfortably about racism involves reflecting on our own ethnicity and associated experiences. We hope this article may encourage this reflection and hope to model this by being transparent around our own ethnicities at this point.

The first author is a Ugandan British Black female who grew up on the Kent/London borders, an area with a population that has become progressively more ethnically diverse in the last 30 years. She currently works in a borough with a demographic of nearly 50% of people from racially minoritised ethnicities. She has extensive experience in working with patients who have experienced racism and discrimination, which is unequivocally matched by her own experience of racism in various contexts over her life trajectory.

The second author is a white British male who grew up in an area of the UK with a population that was majority white ethnicity and only learned to significantly reflect on (and discuss) his own ethnicity and the impact on clinical and supervisory interactions much later in his career than would be ideal. Having not received any training on this during his clinical psychology training and CBT training, this paper provides an example of the information he might have found useful 20 years ago.

The third author is a white British female who grew up in an area that was majority white ethnicity. Racism was not extensively addressed at the time of her clinical psychology or CBT training and her ongoing learning has developed from working within specialist trauma services based in diverse communities.

Case examples

Throughout this paper we will use three composite case examples to illustrate the various potential presentations we might work with where racism was part of the event that caused the PTSD. These are illustrative examples and not based on real patients. They are briefly described below:

-

(1) Kezia is a 25-year-old female from the Gypsy Roma community; she was racially assaulted by two white males. The men stabbed her while she was on the bus with other members of her community whilst shouting ‘You dirty [specific ethnic slur]’. This took place during a fight that had ensued following racial slurs made towards Kezia and her friends. Kezia has routinely experienced vilification, marginalisation, and social exclusion from white British people in her community.

-

(2) Hassan is a 42-year-old male British Bangladeshi male. He witnessed his son being racially assaulted by the police. At the time, Hassan was commuting home from work and his son had been on the way home from college, when he was chased and restrained on the ground by armed police officers. As a family they had experienced increased incidents of both Islamophobic hate crime from their local communities and ‘stop-and-search’ by the police. This dated back to the 2012 terrorist attacks, which correlated with high rates of Islamophobic incidents.

-

(3) Taliah is a 30-year-old Black, British, Jamaican female, who experienced life threatening racial discrimination during childbirth. Taliah was denied pain medication during labour, despite this being documented on her birth plan and her numerous requests. Taliah overheard white staff stating ‘You know them Black people, leave her, they don’t feel pain like us. She’ll be fine, we need to attend to the others’. Additionally, routine checks on the baby’s heart rate were omitted during labour. This contributed to further complications, including her baby’s deprivation of oxygen. Previously Taliah’s family members had been victims of the Windrush scandal: exposed to prolific trauma including deportation of close relatives by the Home Office.

1. Considerations regarding the Ehlers and Clark model of PTSD

This section summarises key aspects of the Ehlers and Clark model of PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) and how these can be applied when racism has been experienced as part of the traumatic event(s).

Personal meanings

The personal meanings people apply during traumatic experiences and the aftermath drive the sense of external or internal current threat that patients with PTSD experience. The cognitive model also includes prior experiences and beliefs that impact on the individual meanings of trauma. When working with experiences of racism during traumatic events, therapists should be mindful of prior experiences of racism (either personal or witnessed in the wider community) that may have impacted on appraisals during current trauma.

Perceived external threat can result from appraisals about impending danger or unfairness of the trauma or its aftermath. For example, when Hassan witnessed his son’s arrest by the police, he recalled during the incident the traumatic death of a Black man in similar circumstances he saw on the news. This understandably impacted on his appraisal ‘My son will be killed’. When the incident was not fully investigated, his appraisals about the unfairness in the aftermath (‘Nothing is changing, my son will live with this threat his whole life’) understandably led to an increase in his generalised sense of danger and anger.

Perceived internal threat arises from negative appraisals about the self during and/or after traumatic experiences. Appraisals of racist experiences can lead to guilt (e.g. Hassan’s thought that ‘I should be protecting my son’), or shame and low self-worth (e.g. ‘I’m a bad dad for not protecting my son’; of Kezia’s appraisal of their assault that ‘I am helpless to change this, I am weak’, ‘I failed’, ‘I’m inadequate’). In our experience mental defeat (e.g. ‘I am being treated like I am not even human, like an object’), often experienced during prolonged trauma (Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Maercker and Boos2000), is a common theme. Research suggests that traumatic experiences of racism can also lead to experiences of moral injury (Elbasheir et al., Reference Elbasheir, Fulton, Choucair, Lathan, Spivey, Guelfo, Carter, Powers and Fani2024). We do not discuss interventions for moral injury in detail in this paper but further guidance on addressing moral injury in CT-PTSD is provided in Murray and Ehlers (Reference Murray and Ehlers2021).

Poorly elaborated and disjointed memories

Traumatic memories are often recalled in a disjointed way because the worst moments are poorly elaborated in memory. For example, when Hassan recalled the moment he feared his son would be killed, he was unable to access the information he later knew (i.e. that he survived). As memories are poorly elaborated and integrated, they are re-experienced with a quality of ‘nowness’, so feel presently threatening rather than like a memory. This also means that trauma memories are triggered easily by stimuli with similarities to the time of the trauma; for example, hearing similar racially abusive words, or seeing racist mistreatment on the news or in day-to-day life.

Maintaining cognitive and behavioural strategies

It is understandable that when people experience internal or external perceived threats, they will use different cognitive strategies and safety behaviours to manage these (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers, Maercker and Boos2000). The strategies used will depend on the individual’s specific appraisals. For example, people who have appraisals linked to anger, guilt and shame often ruminate about what happened. Those who have an over-generalised sense of danger may scan for danger or avoid leaving the house. Some strategies and behaviours have the unintended consequence of increasing symptoms of PTSD. For example, scanning for danger increases a sense of threat and trying to push memories away can lead to increased intrusions.

The safety behaviours that individuals with PTSD use are idiosyncratic and it is essential for therapists to take time to explore what these might be. These might be strategies that therapists are less familiar with identifying in PTSD. For example, since Kezia’s racial assault she had developed various interpersonal safety behaviours to try to avoid putting herself in a position again of experiencing racism. For example, she tended to keep quiet in groups of people she was less familiar with, held back from sharing her opinions, and avoided being the centre of attention.

It is essential that therapists do not make any assumptions from their own frame of reference around the adaptiveness of any specific behaviours intended to reduce threat. Some behaviours could have their origins in adaptive responses or be an extension of a normative and adaptive response for a specific community relating to common experiences of racial inequity. For example, it would be unwise to jump to any conclusions around the behaviour of avoiding police confrontation or even running away from the police when we consider the context of disproportionate usage of stop-and-search and Taser use on minoritised ethnicity communities and the associated lower level of confidence in the police system (Independent Office for Police Conduct, 2023). There are a whole range of examples where individuals from minoritised ethnicities face higher threats from societal systems. Heightened hypervigilance may be adaptive within societal contexts where racist ideologies are normalised (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Holmes, Zare, Haeny and Faber2023) with over 50 years of data evidencing inequities in access, experiences, and outcomes of mental, physical, and societal health care for ethnically minoritised communities (Bansal et al., Reference Bansal, Karlsen, Sashidharan, Cohen, Chew-Graham and Malpass2022, Raleigh and Holmes, Reference Raleigh and Holmes2021).

Therapist exploration of the impact of living with higher threat requires curious, skilful, reflective, and validating questions from the therapist to understand the function and context. A similar point has been made elsewhere relating to the LGBTQ community where therapists have been advised to consider the impact of chronic victimisation experiences and daily identity threats when trying to understand the function of specific behaviours (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Berke, Scholl, Ruben and Shipherd2020).

2. Considerations for cognitive therapy for PTSD

Developing a trusting therapeutic relationship to ensure racism can be discussed

For CT-PTSD to be successful it is essential that the therapist creates a trusting and safe therapeutic environment for the patient to talk about their traumatic experiences. This is particularly important when the patient reports feeling ashamed about their traumatic experiences, when they are not sure if the therapist will validate (rather than dismiss) racist experiences or when they are worried about upsetting or making the therapist feel uncomfortable. There is also evidence that there can be social costs to sharing personal experiences of racism, including being perceived as less likeable, a complainer or someone who is avoiding personal responsibility (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Endlsey, Motley, Shawahin and Williams2018). Combining this with the fact that asking or talking about discrimination can at times feel uncomfortable for many therapists (see Beck, Reference Beck2019) and they may fear making a mistake or saying something offensive (Naz et al., Reference Naz, Gregory and Bahu2019), it is obvious why direct discussion of racism can be avoided. As therapists, we have a duty to take responsibility and create an environment where such discussions are permissible and actively invited. If therapists do not ask directly about key personal meanings of the traumatic experiences, these can be missed. During Kezia’s CT-PTSD assessment she felt ashamed to disclose her experience of racism and so described only being stabbed. It was only when her therapist explored this more directly that Kezia felt able to share the details of the racism she experienced. Example questions could include:

‘I always ask everybody I see if there are personal characteristics or whether there is something about their background or identity that they think might be relevant in the traumatic event they experienced such as their ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or faith. Do you think any of these factors may have been relevant in the way you were treated?’

‘Often people who experience racism feel like they aren’t believed or have to prove that it was definitely racist. This isn’t the case here and my job is to understand what happened and the impact it has had on you.’

There may be specific value for white therapists in acknowledging their ethnicity and making it clear that they are able to hear racism identified and discussed. For example, stating unambiguously:

‘I’m a white person who hasn’t been on the receiving end of racism, but it is important for our work that you feel able to discuss any elements of your incident that you think may have been related to racism. My role here is to hear that and help you explore the meaning and impact for you.’

As we have discussed earlier, our own identities, experiences and life experiences influence how our knowledge and skills are implemented. In addition, characteristics of the therapist can at times be matching triggers for the patient and their specific index trauma event(s). For example, if Hassan was working with a therapist who looked similar to, or reminded him of, the armed policeman involved in the traumatic incident, it may be that this matching trigger could evoke the memory of what happened to his son. It is important that these can be helpfully reflected on, raised by the therapist, and ideally made explicit within treatment (e.g. naming the possibility of the therapist reminding the patient of the incident or a potential fear of discussing the incident with someone with a specific ethnic identity). Being willing to invite discussion on this aspect of the relationship allows it to be addressed early in therapy. This might involve using ‘Then versus Now’ memory discrimination (discussed in detail later). It might also help to normalise difficulties in trusting the therapist, obtain ratings or indicators of trust and explore what the therapist could do to build trust going forward.

In a small number of cases, it might be that this is insurmountable for the patient, and the therapist may need to arrange for the patient to be allocated to another therapist.

Validate experiences of racism

As is always the case when using CT-PTSD, it is essential we validate the patient’s experiences. Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Holmes, Zare, Haeny and Faber2023) describe how experiences of racism can lead to guilt and shame, and how essential it is that clinicians provide a validating response that makes clear how unacceptable the experienced racism was. Williams and colleagues provide some helpful examples of how this can be done by saying things such as: ‘I am so sorry you had to experience that’ or ‘Nobody should ever have to put up with those behaviours’ (William et al., Reference Williams, Holmes, Zare, Haeny and Faber2023; p. 569).

It is common for racism to be masked or subtle. However, even when it is explicit, it can remain unprovable and denied by the individual perpetrating it. People who have experienced racism may often doubt themselves or be encouraged to not recognise it as racism or to question the meaning of the experience. It is therefore particularly important that the therapist validates their experience, and in the majority of cases it is unhelpful to engage in a debate around whether a particular experience was racism-related or not. This requires particular consideration when there are differences in the racialised identities of the patient and therapist.

Reflecting on and being aware of your own identity and how this might impact on processes

It is important for CBT therapists to develop an awareness and understanding of both the historical and societal context of oppression, racism, and discrimination for service users (Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, McRae and Gordon2021). As a therapist, minimising, ignoring, and failing to affirm the impact of any person’s experience of oppression would be in conflict with our purpose. There are a range of tools to aid self-reflection on therapist identities such as Social GRACES (Burnham, Reference Burnham and Krause2012), the ADDRESSING framework (Hays, Reference Hays2013) or the Social Identity Map (Jacobson and Mustafa, Reference Jacobson and Mustafa2019).

Throughout assessment and therapy, it is essential that therapists consider the personal meanings of trauma and perceptions of current threat based on the individual patient and their characteristics, rather than purely through the lens of their own experience. For example, for a white therapist the future possibility of being pulled over by the police could be viewed as completely non-threatening but could contain significantly higher, recurring threat for a Black male (and the perception of threat could be further exacerbated depending on recent media stories about racist stop-and-search incidents). This task requires the therapist to both be able to step outside of their own experiences of the world (understanding that the world around them does not treat everyone the same) but to also have empathic but honest and detailed discussions around levels of threat linked to matching triggers. For example, it is not the role of a white therapist to convince a Black man that being stopped and searched is different from the original trauma memory and therefore no threat whatsoever. However, nor would it be helpful to make unexamined assumptions about the likelihood of threat for a Black male in this situation. It might be useful to bring in information from outside the therapy dyad, from people from a similar demographic background (e.g. other young Black males) who may have not experienced the same traumatic event, for example using a survey (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Kerr, Warnock-Parkes, Wild, Grey, Clark and Ehlers2022) but ensuring that a credible survey participant population can be agreed with the patient. Contrasting the patient’s appraisals and coping strategies with someone who shares relevant identities such as their ethnicity and gender but who has not experienced the same traumatic event and does not have PTSD, can be a helpful way to identify helpful aims and targets for change within therapy. As discussed earlier, the key is to understand what is a normative and adaptive behaviour that may be required and accepted for a specific community and what is a new or extended behaviour that has developed after the trauma (and that may be less helpful and actually unhelpful). The survey allows this contrast to be made for both patient and therapist.

Identifying appropriate treatment targets and considering ongoing threat

CT-PTSD is a focused therapy and as such aims to process and reduce the impact of specific trauma memories that are being re-experienced. Similar to CT-PTSD for other types of traumatic incident, the patient may describe more than one incident and when considering traumatic experiences related to racism, it is even more likely that the patient has experienced other racism-related experiences, even if these have not led to PTSD. The focus should be on the specific incidents that are re-experienced, but other related ones can (and should) be included in the formulation when relevant, under ‘prior experiences’ (Murray and El-Leithy, Reference Murray and El-Leithy2022).

Clinicians often debate whether proceeding with CT-PTSD in the face of potential threat is appropriate. It would certainly be wrong to delay treatment until a patient was unlikely to experience further racism, and data suggests they may be waiting a long time (Ellingworth et al., Reference Ellingworth, Bécares, Šťastná and Nazroo2023). A recent systematic review has suggested that standard PTSD interventions with adaptations can still be effective for populations under ongoing threat (Yim et al., Reference Yim, Lorenz and Salkovskis2024). The role of the therapist is to work with the patient to understand the extent of ongoing threat, potentially using a range of methods to establish this. There is a careful balance in not invalidating the beliefs and experience of the individual (especially for therapists who do not have their own experiences of racism) but also not allowing the PTSD-related threat beliefs to overly dominate the perceptions of current and future risk. Surveys of individuals from within the patient’s own community who share similar identifies (e.g. ethnicity, gender) may provide wider information to help the patient to discriminate between objective levels of threat and a possible elevated perception of threat driven by their memory re-experiencing. Helping the patient to recognise and utilise different responses to these will be important, for example not completely dropping adaptive hypervigilance or escape in objectively threatening situations. The same encouragement not to delay CT-PTSD also applies with respect to not routinely undertaking lengthy stabilisation phases of treatment before moving onto the focus on the index trauma.

Whilst the scope of CT-PTSD is much more specific than wider interventions focused on managing stress and trauma due to racism, it is likely that many of the core interventions in CT-PTSD can support patients in developing more adaptive coping in terms of finding a way to survive (not to tolerate) likely future experiences of racism. For example, within work on reclaiming/rebuilding life, therapist and patient could consider integrating specific elements of evidence-based protocols for addressing racial trauma (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Holmes, Zare, Haeny and Faber2023). Within a course of CT-PTSD we have also had some experiences of successfully using role-play techniques and imagery exercises to help patients feel more empowered and resilient.

Psychoeducation around PTSD and racism, normalising and case formulation

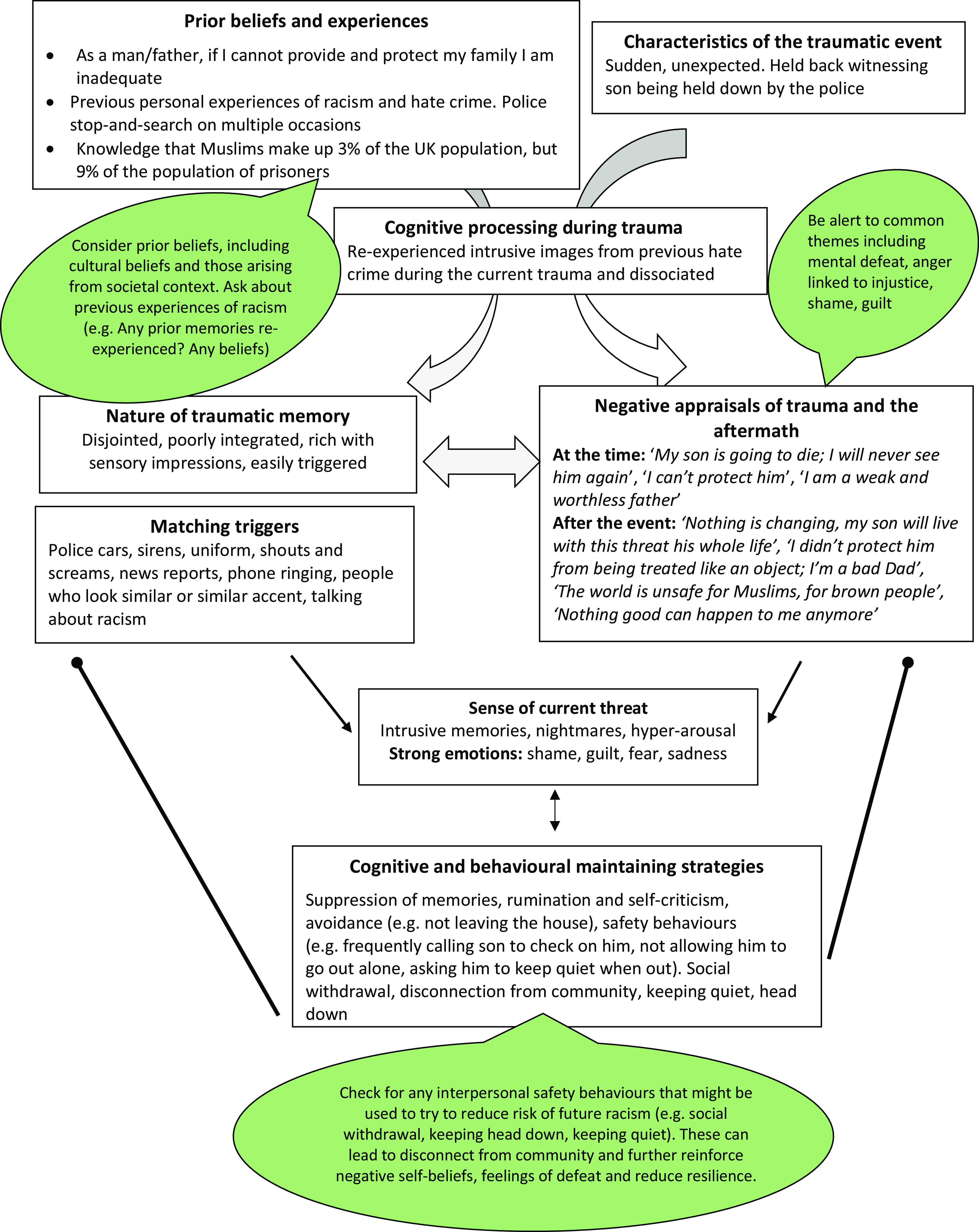

The provision of psychoeducation on the socio-historical context of racism can be incredibly affirming for people from ethnically minoritised communities, identifying the potential systemic, structural, and individual influence of race-related stressors on the problem development and maintenance (Kirkbride et al., Reference Kirkbride, Anglin, Colman, Dykxhoorn, Jones, Patalay, Pitman, Soneson, Steare, Wright and Griffiths2024). It also provides another opportunity to acknowledge the challenges relating to societal, systemic context (e.g. concepts of ‘weathering’ (Geronimus, Reference Geronimus1992) and ‘racial battle fatigue’ (Smith, Reference Smith, Lomotey and Smith2023). The provision of information on culturally relevant community organisations, legislation on discrimination at work and stop-and-search can be relevant. It can serve to further anchor patients, empowering them as they progress through therapy, and can be integrated into reclaiming their life activities. Figure 1 illustrates how a CT-PTSD formulation can be adapted to include the experience of racism (in the example of Hassan).

Figure 1. Example of a CT-PTSD formulation for Hassan (includes his experiences of a traumatic event linked to racism and wider societal experiences).

Reclaiming and rebuilding life activities

Many patients stop engaging in meaningful and enjoyable activities after trauma. This can then further maintain the personal meanings of the trauma and its aftermath. For example, after Kezia experienced a racially motivated physical assault, she felt ashamed, defeated, and angry. She thought of herself as ‘weak’ and ‘inadequate’ and was pre-occupied by the injustice of being treated as if she was ‘less than human’. She stopped leaving the house and doing the things she enjoyed such as going to the gym and socialising as she feared being assaulted again. This fuelled her negative view of herself. It also gave more time for her to ruminate on the injustice of her assault, which maintained her anger. Supporting patients to reclaim or rebuild their lives is a key intervention used from the first session and throughout CT-PTSD. A role-play demonstration is available on www.oxcadatresources.com. Reclaiming or rebuilding their life can help address negative personal meanings about the self that can be common after traumatic experiences involving racism. It is also a way to help patients integrate activities that can help them feel more resilient when feeling defeated after trauma and in the face of repeated incidents of racism.

In Kezia’s case, during early sessions she and her therapist discussed reclaiming activities that she felt safe to do, such as cooking more at home and doing some exercise videos. These were also key in shifting her sense of herself as ‘weak’ and ‘inadequate’, in addition to having a positive impact on her mood. As treatment progressed and they worked on her perception of risk and addressing trauma triggers using stimulus discrimination, she felt more able to experiment with reclaiming life activities outside the home. Kezia was also ashamed about her experience and did not want to disclose to others that she had experienced a racist attack which impacted on reclaiming her life. Carrying out a survey and experimenting with disclosing about the traumatic event to a close friend was key in overcoming this block to reclaiming and reconnecting to her community (see section on working with shame).

It is not unusual for there to be blocks to reclaiming/rebuilding life in PTSD that need to be carefully identified and addressed. For example, we have found that some patients experience feelings of mental defeat during traumatic experiences where racism is involved, and this can often come in the context of the fatigue of previous experiences of racism and racial trauma (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Osman, Gallo, Pereira, Gran-Ruaz, Strauss, Lester, George, Edelman and Litman2022). For example, when Hassan witnessed his son’s restraint, he thought that his son was treated ‘like an object’ and felt totally powerless to do anything. After the trauma he found himself ruminating not only on the index event but also on previous microaggressions and experiences of discrimination. He developed a belief that ‘Nothing good can happen to me anymore’. In turn, these cognitions impacted on Hassan’s behaviour as he had stopped doing things he enjoyed and that were important to him, which reinforced his feelings of low mood, defeat and powerlessness, which in turn made engaging in meaningful activity a struggle. For Hassan it was key that his therapist validated and normalised his sense of defeat in the context of his previous experience and the index trauma. They put Hassan’s belief that ‘I’m too exhausted to do anything’ to the test by experimenting with gradually building up activities he used to enjoy (e.g. exercise, attending the mosque) and helping him to learn that by re-engaging with small activities he started to regain his energy and feel less defeated.

Some people who have experienced racism as part of a traumatic event may choose to reclaim their life by engaging in specific activities that strengthen their racialised identity (see the Healing Racial Trauma protocol for a full discussion of this: Williams et al., Reference Williams, Holmes, Zare, Haeny and Faber2023). Patients may also choose to engage in social action or activism to try and address racism on a systemic level (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Holmes, Zare, Haeny and Faber2023), as part of reclaiming their life. However, this is clearly the choice of the patient, and no individual should be expected to do this based on their racialised identity. However, if the patient feels that this would be helpful in reclaiming their life or sense of self-efficacy, the therapist can help the patient explore options and possible impacts.

Memory-focused techniques

Training videos on all the memory-focused techniques described below are available at www.oxcadatresources.com.

Updating trauma memories

The threat of racism is an ongoing reality for those from minoritised backgrounds and this should be acknowledged. In circumstances where patients are experiencing ongoing racial abuse, provision of relevant legal information and advice, and/or support to access local activist and cultural community groups, will be key as a first step. When memories are re-experienced with a sense of nowness, with embedded appraisals that drive an elevated current sense of threat to the person’s safety (e.g. ‘I am about to be killed’) or view of themselves (‘This means I am inadequate’, ‘I am to blame’), updating these meanings in key hotspots of the trauma memories is a core intervention in reducing PTSD symptoms. Even for those who live in environments where ongoing racism is a more frequent risk, reducing the impact of distressing memories will be key to building ongoing resilience. Below we describe the key steps Ehlers and Clark (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) recommend in updating trauma hotspots and their associated personal meanings. Video demonstrations of each of these stages are available at www.oxcadatresources.com.

Stage 1: Identify the most threatening personal meanings

To help elaboration of the trauma memories and identification of the most threatening personal meanings of trauma, CT-PTSD starts with getting a full account of the trauma using either imaginal reliving (Foa and Rothbaum, Reference Foa and Rothbaum1998) and/or narrative writing (Resick and Schnicke, Reference Resick and Schnicke1993). There are various clinical indications as to why one approach might be used over the other (see oxcadatresources.com for videos on when to use narrative writing vs imaginal reliving). For example, narrative writing is sometimes recommended for those who dissociate or have longer traumatic events, such as Taliah whose traumatic birth experience spanned several days.

Patients may find it hard to disclose experiences or meanings linked to racism if they feel ashamed or have fears about how the therapist might respond. This may also link to previous experiences of being dismissed or not believed. Developing a trusting therapeutic relationship where both the therapist and patient feel able to ask and talk about experiences of racism is key here. Where the person has multiple events that are re-experienced or previous experiences of racism that could have impacted on their appraisals, it might be helpful to add these onto a timeline. When working with experiences of racism, as with any hotspot, it is important that therapists continue to gently explore the worst meanings for patients. There can be multiple meanings attached to one hotspot and different layers of meaning. For example, at one of Kezia’s hotspots during her assault she first reported the thought ‘I will be killed’ as her worst meaning. It was only after careful unpacking that she also expressed: ‘I will be killed because they do not value my life’, ‘I am treated as if I’m not human’, ‘This means I’m totally weak and inadequate’.

Using questionnaires such as the Post-Traumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI; see Foa et al., Reference Foa, Ehlers, Clark, Tolin and Orsillo1999 for the long version and oxcadatresources.com for a short version) can be helpful in identifying relevant personal cognitive themes. Although the measure was developed to cover a range of traumatic experiences and not specifically around racism, many items are relevant for those who have experienced racism as part of their trauma (e.g. ‘I am inadequate’, ‘My life has been destroyed by the event’, ‘I have to be on guard all of the time’). The measure can be useful in identifying cognitions linked to trauma hotspots.

Stage 2: Identify updating information that makes the worst moments less threatening

In CT-PTSD, there are sometimes simple updates that can be identified and brought into memory updating (see Stage 3 below) shortly after the initial reliving or trauma narrative is given. This is also the case with experiences involving racism when there might be frozen meanings. For example, Hassan, who thought his son would be killed by the police, found it helpful to update his story with the knowledge that ‘My son survived’. However, some appraisals take some time to collaboratively address using a range of CT-PTSD interventions (e.g. Socratic questioning, surveys, pie charts, behavioural experiments, imagery techniques, positive data logs).

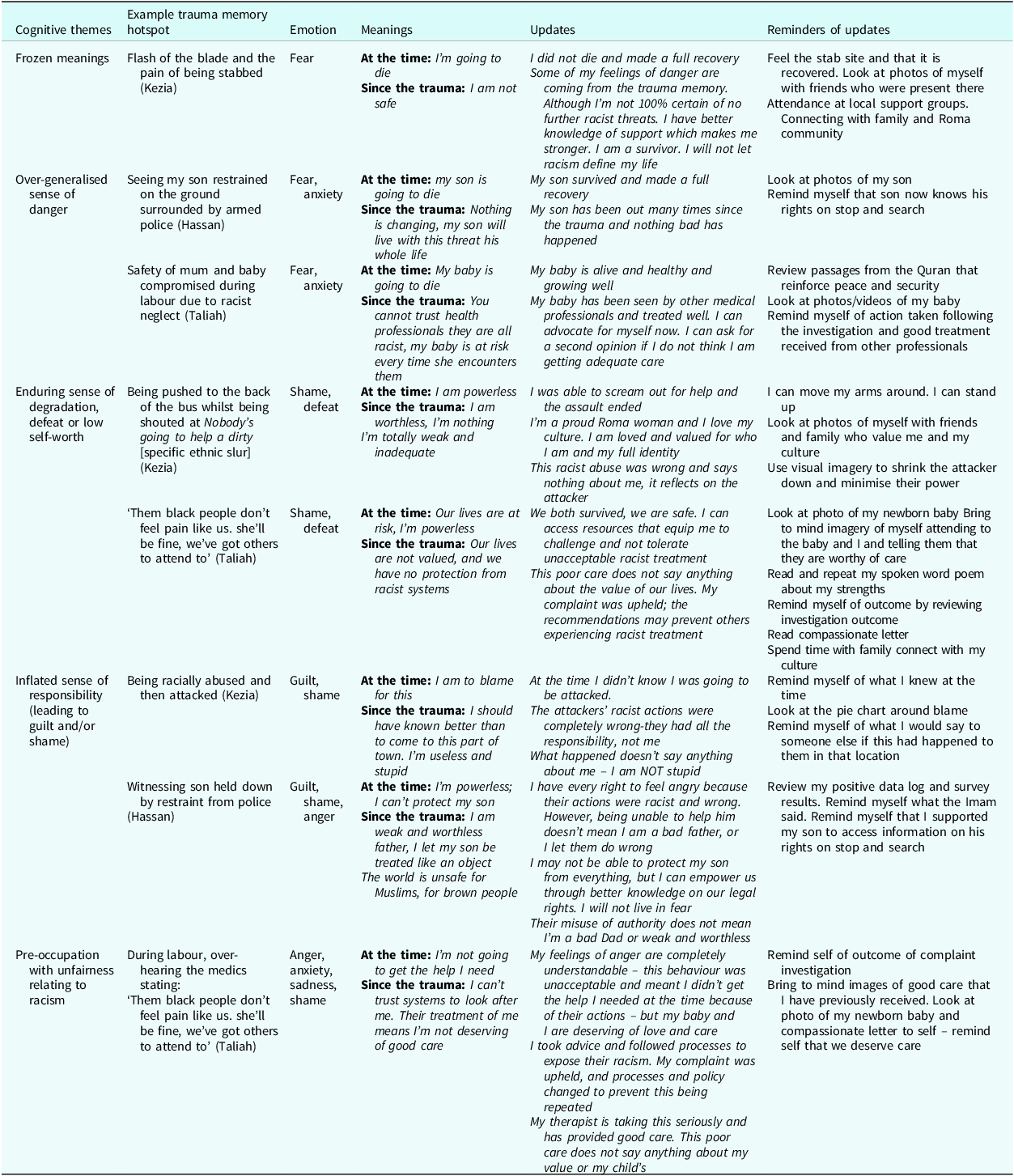

What is important throughout this process is to not invalidate the person’s experience of racism, or experiences within society. Some appraisals and associated distress (e.g. anger, feelings of betrayal and moral injury) are justified, understandable and not excessive. Empathy, validation and affirming perceptions of racism experienced will be essential. The therapeutic focus of updating is to identify any personal meanings that maintain excessive distress about the experience, rather than invalidate or minimise the actual racism experienced. Validation for a patient’s understandable reactions might also be included in the updating. For example, Hassan experienced anger, guilt and shame in relation to witnessing his son being restrained by police. Taking time to first let him express his angry feelings in therapy, providing empathy and validation, was important before working on updating his guilt and shame appraisals. When updating his memories, his feelings of anger were acknowledged in addition to his updating information, e.g. ‘I have every right to feel angry because their actions were racist and wrong. BUT I KNOW NOW being unable to help him doesn’t mean I am a bad father, or I let them do wrong’. Readers can find other examples of how this was done in Table 1 by looking at Taliah and Kezia’s updates.

Table 1. Illustrative case examples of common cognitive themes addressed during memory updating in CT-PTSD where racism has been part of the index event; as the personal meanings attached to trauma hotspots are central to the Ehlers and Clark model, unpacking these is integral to the success of treatment

Stage 3: Link the updating information to the relevant moment in memory

Once updated information is identified, each hotspot is taken one at a time to help connect the updated information discovered in therapy to the worst moments/meanings in the trauma story. This is done by asking the patient to read or hold in mind the worst moment whilst emotionally engaging with the hotspots to bring online the updated information. This might involve saying (or reading if the story was done in narrative writing) the updates aloud (e.g. ‘I know now my son survived’). To help the updates feel true and sink in, it helps to draw on different senses when updating. For example, if patients were unable to escape or move at the time of the trauma, they can now move in a way that was incompatible with their experience. For example, Kezia who felt weak and inadequate during her racist assault was encouraged to stand tall (rather than curled up on the ground as she was at the time) and look at photos of herself since the assault doing things that help her feel adequate and strong. Again, as described in Stage 2, the updates can include an acknowledgement of the racism within the updates if this would be useful for the patient.

Imagery techniques are often helpful when updating trauma memories. These can be particularly helpful in cases when people experience shame or when some of the worst things did happen during the traumatic event. For example, Kezia re-experienced an image from her trauma when she was curled up on the floor. At this moment she believed she was totally weak; she felt she was treated like she wasn’t a human and was ashamed. After addressing these cognitive themes (see sections on shame appraisals below), her therapist asked her if she could think of an image that would help her show herself what she had discovered in treatment – that it was the perpetrators who were the weak and inhumane ones and that she could start to regain power over her life again. She decided to picture the perpetrators shrinking down to the size of a bug and then her growing taller and squishing them with her foot. For Kezia this helped her updated meaning feel true – that they were the weak ones who were in the wrong, and that she could start to regain control over her life – they no longer had all the power. Table 1 includes an example of imagery used to update hotpots for Hassan. If several traumas involving racism are re-experienced with similar meanings the patient might be asked to hold their updated information in mind and then to bring to mind other related hotspots and connect the new information discovered in therapy with those; we sometimes refer to this as ‘the domino effect’.

Stimulus discrimination (‘Then versus Now’)

A key part of CT-PTSD is stimulus (trigger) discrimination where the patient is helped to identify current or potential triggers matching the trauma memory with the aim of helping the patient to break the link between present-day triggers and the trauma memory by discriminating between the two. The first stage of this is to work together to identify these triggers and enable the patient to become aware of these in the session, and then ideally as they occur in day-to-day life. There can be obvious triggers such as seeing someone who looks like the person who enacted the racist traumatic event (e.g. for Hassan this was white men, dark haired, wearing a police uniform). There can also be much more subtle memory triggers where the therapist and patient have to work harder as a team to try and identify them. In Hassan’s example a less obvious trigger was hearing voices shouting (which reminded him of the armed police leader shouting instructions to his son), an even less obvious one was seeing his son lying down on the floor at home. Once the triggers have been identified, the second task is to work together to be able to discriminate between the triggers and the traumatic memory, recognising what is similar and then importantly looking out for, and focusing on, what is different. This allows patients to break the link between the trigger and the trauma memory, which can help reduce memories from being re-experienced by present-day triggers. Video illustrations are available on the oxcadatresources.com site.

Shame or fear of offending the therapist might prevent a patient from disclosing if their trauma memories are triggered by descriptive characteristics of a person, particularly if this matches those of the therapist. Normalising this can help; for example: ‘many people after experiencing racial traumas like this understandably find that their memories are triggered when they see people who have similar characteristics to the perpetrators, whether that be a similar ethnicity, appearance or accent, has that been the case for you?’.

Therapists often tell us they are unsure about using memory-focused interventions such as stimulus discrimination in the presence of ongoing threat. This is important because, as we have acknowledged, for somebody who is ethnically minoritised, the risk of facing future racism remains. In addition, the perception of threat may also be further exacerbated by previous repeated experiences, and recurrent media stories. It is important to clarify here that the aim of Then versus Now is not to present the present-day situation/trigger as totally without threat. The aim is to help reduce memory re-experiencing. This means that patients will be able to appraise and manage present-day situations as they are, rather than through the lens of past traumatic memories and the heightened distress that will bring. This helps build the necessary resilience key in managing any future experiences. For example, if Hassan is stopped and searched by the police again in future, it would not be helpful for him if he is overwhelmed by flashbacks of his son on the floor and all the strong feelings from the past come tumbling out of his memory cupboard. For Hassan when he saw a police van in everyday life rather than reminding himself ‘I am safe now’, instead it was helpful to focus on ‘This is a different situation’, ‘My son is not here now, not being assaulted now’.

Site visits

An important memory-focused intervention in CT-PTSD is returning to the site of the trauma. Video illustrations of in-person and virtual site visits are available at oxcadatresources.com. Site visits can help the patient to focus on what is different between the traumatic event (e.g. for Hassan: ‘My son was being restrained by the police and bleeding’) and the present situation (e.g. ‘I am walking down the street, my son is not here now, there is no blood, he is not being restrained now, he is safe’). Additional benefits of site visits (as outlined in detail by Murray et al., Reference Murray, Merritt and Grey2016) are that new information can sometimes be found at the site that can be helpful in updating personal trauma meanings.

For example, Hassan had been angry that people in the nearby houses had not come to offer help. However, standing at the site he was able to see that most of the nearby homes did not have a clear view of what was happening as there were tall trees blocking the site of his son’s restraint. Furthermore, negative beliefs about returning to the site can be put to the test, such as ‘I will have a panic attack and will not cope’. Site visits can facilitate the realisation that the traumatic event is in the past. This is important even in the context of ongoing racism as it can help reduce the re-experiencing of the specific traumatic memories that drive a patient’s distress. There are occasions when the objective risk might lead to the decision to carry out a virtual site visit instead of an in-person visit. For example, because Kezia’s racial assault took place near the home of the perpetrators it was agreed to be unsafe to return to the site and a virtual site visit using Google Street View was used. Here they were still able to locate the street where the assault happened and help Kezia to focus on the key differences (e.g. that she was no longer laying on the floor in pain, that the attack was not happening now and was in the past). Whenever possible we encourage patients to actively do things to show themselves what they know now. For example, Kezia was also able to show herself what was different now by moving in a way she had been unable to at the time and to bring to mind the key updating information she discovered in therapy. For example, telling herself ‘I now know this says something about them and does not mean anything about me, it means they are the weak and inhumane ones, I am a good, strong woman’ and bringing to mind the visual image she developed of her perpetrators shrinking to show that they were the weak ones.

Working with meanings: common cognitive themes

To our knowledge, no empirical research has been done to date on identifying common cognitive themes held by patients who have experienced racism as part of their trauma(s). We encourage further research on this in future. Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Osman, Gallo, Pereira, Gran-Ruaz, Strauss, Lester, George, Edelman and Litman2022) anecdotally report shame and guilt being common. In our experience this rings true, and patients can also describe mental defeat and understandable anger. Some case examples of personal meanings linked to racism are given in Table 1.

Addressing cognitive themes

The negative personal meanings of a traumatic event are a key component of the cognitive model and drive the current sense of threat. Identifying the different negative thoughts that patients had at the time and after their trauma(s) is essential to treatment. We recommend therapists take time to unpack the meanings of different trauma hotspots and use questionnaires such as the PTCI (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Ehlers, Clark, Tolin and Orsillo1999). Therapists should keep in mind that when working with racism, patients may avoid talking about some of the worst moments and meanings, particularly when shame is evoked.

The personal meanings of trauma will also be maintained by behaviours and cognitive strategies that need to be identified and dropped in treatment. Therapists will be familiar with many of the common strategies that patients with PTSD may use such as thought suppression, emotional avoidance, excessive scanning and checking for signs of danger, rumination and self-criticism. Questionnaires such as the Safety Behaviours Questionnaire (Dunmore et al., Reference Dunmore, Clark and Ehlers2001) or Response to Intrusions Questionnaire (Clohessy and Ehlers, Reference Clohessy and Ehlers1999) can help identify and track these processes over the course of therapy. However, therapists may be less familiar with some of the interpersonal safety behaviours that in our experience can develop after traumas involving racism; indeed further research is required here. Taking time to be curious when unpacking what people do related to their negative thoughts is useful. For example, Kezia found that after her trauma she started to keep quiet around others for fear of further racist attacks, particularly people of similar ethnicity to her attackers. She found herself holding back more, keeping her head down to avoid eye contact, sharing less of her cultural identity and avoiding talking about her community. These strategies unintentionally maintained her view of herself as ‘weak and inadequate’. Below we give some examples of both cognitive and behavioural strategies used in CT-PTSD to address a range of common appraisals we have found people with PTSD have after racist experiences. Video illustrations on addressing these cognitive themes are available at oxcadatresources.com.

Over-generalised sense of danger

After traumatic experiences involving racism, it is common for people to develop an over-generalised sense of danger. As racism is a reality that many people will have experienced previously and may face in future, it can help to discuss the continuum of risk. Considering a specific situation, where did the person put themselves on the continuum of zero to high risk before the trauma? Where do they put others with the same ethnicity and gender? Exploring what precautions others take and would advise (which may involve doing a short survey or speaking to friends/family) can be useful to figure out what are necessary strategies versus excessive safety behaviours. A risk calculation (calculating the number of times Kezia had left her house and been physically assaulted) helped Kezia to realise that because of the trauma memories her perception of risk was elevated. Using ‘Then versus Now’ discrimination in interactions with people who triggered her memories was helpful and Kezia was then able to experiment with speaking to two strangers during a session, sharing more about herself and Roma culture. An over-generalised sense of danger can be a block to reclaiming elements of a patient’s life and this can be addressed via behavioural experiments later in treatment. Here, the aim is not to eliminate or rule out any potential threat; rather the aim is to come to a balanced understanding of the level of risk.

Trust in organisations and systems can be eroded by repeated race-based stressors leading to low expectations of fair treatment, safety and accountability. This can lead to avoidance of necessary services (such as not seeking help from the police or medical services as needed). For Taliah this meant that she avoided taking her baby for routine check-ups with the GP. When considering what is a safety behaviour and what is self-protective, cost–benefit analysis helped to review the pros and cons of accessing health appointments. This helped Taliah distinguish between behaviours that might be precautionary (e.g. seeking a second opinion if her medical concerns are quickly dismissed) and safety behaviours that could be detrimental (e.g. avoiding a health appointment). This work, alongside other interventions such as risk continuums/calculations (see above), facilitated Taliah carrying out a behavioural experiment to attend her baby’s health visitor appointment. When she received attentive care, she discovered not all health professionals were racist/negligent.

Enduring sense of degradation, defeat or low self-worth

In our experience many patients describe feelings of shame after traumas involving racism. This is driven by negative appraisals about the self and fears about how others might react, such as ‘This means I am worthless’, ‘I am bad’, ‘Others will think I’m weak’. Mental defeat can also be commonly driven by appraisals that the person was treated ‘less than human’, ‘like I didn’t exist’, ‘like an object’.

Accumulated past racist experiences may have led to the development of pre-traumatic beliefs that are strengthened during the index trauma. It might be helpful to consider if the concept of racial battle fatigue might be relevant for the patient (i.e. cumulative impact of repeated racism; for a description, see Lawton and Abraham, Reference Lawton and Abraham2023). For example, it was helpful for Taliah to understand that her sense of mental defeat and appraisals of the racist abuse she received during childbirth (‘I’m treated like I’m less than human, not deserving of good care’) was in the context of previous life experiences including the deportation of family members by the British government operationalising the ‘hostile environment’ policy as part of the Windrush scandal (Gower, Reference Gower2020; Yan, Reference Yan2023).

Therapists should consider that pre-existing stereotypical, cultural beliefs and assumptions can also contribute to shame appraisals linked to racism. For example, Taliah described an expectation that she must be ‘a strong Black woman’ which contributed to feelings of shame about her symptoms of PTSD (e.g. ‘I should be over this by now, they will think I’m weak’) and was a block to her engaging in self-care which further fuelled her negative beliefs. This stemmed from an internalised societal stereotype about black women having super-human strength, which has dire consequences (Melson-Silimon et al., Reference Melson-Silimon, Spivey and Skinner-Dorkenoo2024), for example acting as a barrier to self-care and self-compassion (Donovan and West, Reference Donovan and West2015; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Wei and Yin2020). Historically the dehumanisation of black communities has been used to justify oppressive, systemically racist practices (Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, McRae and Gordon2021).

In the weeks that followed Taliah’s trauma, her expectations of herself clashed with her struggles to manage her PTSD symptoms. She withdrew from family and friends due to shame-based appraisals like ‘they will think I’m weak for not coping’. Hassan also described how he had grown up with strong expectations of himself as a Bangladeshi male to protect his family and how this impacted on a deep sense of shame that he had not been able to protect his son and a fear of how others in the community would look down on him because of this.

A range of cognitive therapy interventions can help address shame linked to racism. Pie charts can help when patients who feel overly responsible for the event, such as in the case of Hassan. Surveys (see Murray et al., Reference Murray, Kerr, Warnock-Parkes, Wild, Grey, Clark and Ehlers2022) can be a powerful way to address shame. For example, Taliah and her therapist put together a survey asking others whether they believed she was weak for experiencing PTSD symptoms. Hassan found it particularly helpful for a survey exploring whether others thought he was a bad father for not protecting his son to be sent to people from the Bangladeshi community. Behavioural experiments to test out fears in action are also key. For example, after reading the survey Hassan experimented with returning to his mosque to test his fear that he would be shamed friends because he could not protect his son. Sharing his concerns with his Imam was also a powerful experiment.

Exploring what the patient would say to another person of a similar ethnicity can also be helpful, e.g. Taliah was asked ‘Imagine your daughter grew up and was treated in this way, would you tell her that she was undeserving of care? Why not?’. Taliah found it helpful to think about her daughter in identifying that all people, including her, have core value, and are deserving of respectful care:

Therapist: ‘Why is your daughter deserving of good care?’

Taliah: ‘My daughter is precious, beautiful, she is loved, and her life is valuable.’

Therapist: ‘Are all babies born deserving of good care like your daughter?’

Taliah: ‘Absolutely’

Therapist: ‘You were a tiny baby just like your daughter, so why is it that you are not deserving of the same care and respect?’

Reclaiming life and activities can also play a role in addressing shame-related beliefs. Patients can be encouraged to plan activities that would demonstrate to them an alternative way of thinking. For example, Taliah was encouraged to plan activities connecting with friends and loved ones who show her care. Hassan was encouraged to plan activities that demonstrate to him he is a good a loving father (such as looking through family photos with his wife, hosting a lunch with his family, etc.).

When patients have underlying negative beliefs about themselves linked to previous experiences of racism, positive data logs (see Padesky, Reference Padesky1994) can help. Addressing any rumination or self-criticism maintaining shame is key. Taliah found it helpful to write herself a compassionate letter in the same kind tone she would use when speaking to her own daughter. In our experience written or spoken word/poetry can, when appropriate, establish and strengthen narratives of self which amplify patient strengths. The use of guided discovery to elicit patient strengths can also be supported by timelines highlighting achievements in spite of racist experiences.

Imagery can be a powerful way to update shame hotspots with new information discovered in therapy. For example, Taliah held the moment she overheard the midwife’s racist comment and pictured herself coming in and telling her and her baby that they were worthy of care and giving them the care they needed in that moment.

Inflated sense of responsibility (leading to guilt or shame)

People with PTSD will experience feelings of guilt when they have an inflated sense of responsibility for the trauma(s) (e.g. ‘This is my fault, I could have prevented this’). For example, Kezia blamed herself for her assault because she visited a part of town where she had known others had experienced racist attacks in the past. Therapists will want to look out for and address cognitive biases that can drive and maintain guilt appraisals. Common biases include hindsight bias (judging one’s actions based on knowledge one has now, rather than what you knew at the time), discounting other factors (e.g. not giving the perpetrators enough responsibility) and superhuman standards (e.g. ‘I should have foreseen this would happen’). When working with guilt appraisals linked to racism all the usual cognitive therapy interventions can be utilised. Key interventions we have found helpful include drawing out a responsibility pie chart to help the person consider the role of other factors that take some responsibility; looking at a timeline of events to help address hindsight bias (e.g. for Kezia it was helpful to recognise that when she made the decision to go to the site of the trauma, she had no idea that she was about to be attacked). Supporting the person to consider more what they would say to somebody else can often be helpful in developing a more compassionate perspective:

Therapist: ‘Kezia, if you were speaking to another woman from the Gypsy Roma community who had been attacked in that part of town, would you be telling her that the attack was 100% her fault and she should keep beating herself up about it?’

Kezia: ‘No way. Of course I wouldn’t!’

Therapist: ‘OK, can we think of another woman you like and respect from your community … if she was sitting in the room with us now, what would you be saying to her?’

Kezia: ‘Yeah, I can think of my friend Fenix. If this was her and she was here I would give her a hug – I would tell her I’m so sorry this happened to her. That she shouldn’t blame herself – that the people who attacked her are the ones to blame.’

Table 1 illustrates how this information was brought back into the trauma memory through updating key hotspots when Kezia had guilty thoughts. Therapists should ensure that any behaviours or strategies that are maintaining guilt-related thoughts are also addressed and dropped. Rumination and self-criticism are common strategies here that need addressing.

Pre-occupation with unfairness relating to racism

Anger linked to the unfairness of racism is an understandable reaction and it is first important that therapists give the person space to talk about their anger and to provide validation and empathy for this reaction. The interventions sometimes involve supporting the person to take necessary action, for example in the case of Taliah her therapist helped her to write a letter of complaint to the hospital. A reality for some is that despite taking necessary action, systemic racism may mean that they do not get the justice they deserve. Here writing an anger letter (usually not sent) to the perpetrators can sometimes help the person to express their thoughts and feelings. For some getting involved in local activism can help (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Osman, Gallo, Pereira, Gran-Ruaz, Strauss, Lester, George, Edelman and Litman2022). For example, Hassan went to speak to a local organisation promoting fair and accountable policing of people from marginalised communities.

Rumination often maintains pre-occupation with unfairness and will need to be addressed by helping the person identify when they are dwelling, recognising the unhelpful consequences of doing so, and helping the person to engage in other activity. If sensitively done, after first allowing space to talk about and express angry feelings, a cost–benefit analysis of holding onto anger might be helpful. This involves exploring how much time dwelling on anger takes up in the person’s life and the impact on them, who does the anger hurt more, etc. For example, Taliah’s complaint took many months to be investigated and she found herself often dwelling on the injustice. With her therapist she weighed up the pros and cons of holding onto this anger. They agreed that holding onto a little anger was helpful for Taliah to pursue the complaint, but that being pre-occupied 24/7 with this was exhausting for Taliah, hurt only her (not the perpetrators) and prevented her reclaiming her life and spending quality time with her baby. However, engaging in CT-PTSD and working towards achieving justice related to traumatic racist incidents, are not mutually exclusive.

If the patient is religious, therapists can exploratively learn with their patient about relevant empowering tenets of their faith or at times can involve religious or community figures within session. For example, through guided questioning, elicitation of Islam’s teachings on suffering, justice, peace and security was key in addressing Hassan’s ruminative anger. Hassan’s therapist’s demonstration of cultural sensitivity, including validating his racist experiences and providing information on local community activist organisations, empowered Hassan and promoted trust between them.

Consideration of racism within the therapy blueprint

Towards the end of CT-PTSD we encourage patients to complete a therapy blueprint (see oxcadatresources.com for an example) covering key learning from therapy and how to cope with any setbacks in future (e.g. anniversary of the trauma, etc.). This might include a discussion of how to cope with future incidence of racism in future. The plan would include how to discriminate between these experiences and the trauma incident (Then versus Now) but without minimising the impact and wrongness of these current experiences. For example, for Taliah she wrote out a plan of what she would do if she received poor care from medics in future. Taliah’s plan included reminding herself of the differences between Then and Now, reminding herself of updated meanings developed during the CT-PTSD (e.g. ‘I know NOW that I deserve good quality care’, ‘Poor care does not say anything about my worth’) and then key things she could do differently to advocate for herself. In the months that followed her treatment she found this helpful when a GP dismissed abdominal pain she was experiencing. Drawing on these strategies rather than being overwhelmed by distress and trauma memories she was able to ask for a second opinion which led to the underlying cause being correctly identified. She then also felt able to write a complaint letter to the surgery about this experience rather than dwelling excessively.

Reminder around therapist self-care

We have already touched on the role of the self of the therapist at various points and how this work can add a layer of further complexity to PTSD work given that all of us are racialised beings with our own differing levels of understanding of this.

For white therapists, discussion of racism can bring up complicated feelings, particularly if the therapist has not previously considered their own racialised identity and experiences of being white. For some therapists this could lead to defensiveness, feelings of shame and guilt, avoidance or rumination (Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Kanter, Villatte, Skinta, Loudon, Williams, Rosen and Kanter2019). It is essential that therapists receive training and supervision around working with cultural sensitivity and can reflect on their own identities, power, privilege and gaps in knowledge and experience (British Association for Behavioural & Cognitive Psychotherapies, 2023; Haarhoff and Thwaites, Reference Haarhoff, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Thwaites2016)

Working with racism presents specific challenges for therapists from a minoritised ethnicity who are likely to have had their own history of experiencing racism, and this can be particularly difficult if this is ongoing and frequent. A recent pilot study has illustrated the impact of discussing racism within therapy for Black therapists (Brooks-Ucheaga, Reference Brooks-Ucheaga2023) and identified the powerlessness this can engender. Support to discuss the impact of this work in supervision will be key. A therapist should also be given the option not to take on a patient if the trauma is particularly triggering for them. Using Then versus Now ourselves when working with traumas that are personally triggering can help. When working with many cases with a particular trauma therapists and supervisors should also look out for any increased sense of danger on the part of the clinician. For example, Hassan’s therapist found herself feeling increasingly anxious when she saw police cars and brought this to supervision to discuss.

3. Supervisory considerations

Clinical supervision fulfils a range of roles including ongoing management and support with ongoing cases but also skill development and supporting therapist wellbeing (Milne, Reference Milne2007). All of these need to be considered when the therapist is working with patients who have experienced racism as part of a traumatic event.

Supporting the wellbeing of therapists working with individuals who have experienced racism is clearly important, especially so if the therapist is from a minoritised ethnicity and may have their own experiences of racism (past and/or ongoing) which makes this work even more emotionally challenging. Ideally when supervision was set up and contracts agreed, aspects of supervisor and supervisee identities would have been included in the discussion and both parties would be willing and able to discuss their own ethnicities and those of patients. However, recent UK data tells us that supervisees from minoritised ethnicities working with white supervisors report experiencing much less safety in supervision and much less culturally responsive supervision (than white supervisees) (Vekaria et al., Reference Vekaria, Thomas, Phiri and Ononaiye2023). Clearly supervisors (especially white supervisors working with supervisees from minoritised ethnicities) need to do more to ensure that supervision is culturally responsive, and supervisees can feel supported in discussing ethnicity and experiences of racism (both their own when relevant, and that of patients) and how these may need to be included in problem formulations.

For therapist and patient dyads with shared identities (e.g. matching minoritised ethnicity) or backgrounds, there may be times where this can help in identifying and validating the patient’s specific experiences of racism using the CT-PTSD model. However, shared intersectional identities may also create the potential for blind spots due to the possibility of unhelpful assumptions (Anders et al., Reference Anders, Kivlighan III, Porter, Lee and Owen2021). Supervision plays a key role in facilitating the unpacking of potential interactions between the therapist characteristics and their current/historical contexts and those of the patient in working with the CT-PTSD model. Adherence to cultural humility requires a commitment to therapist and supervisor ongoing learning on the realities of racism, power and oppression (Samuel, Reference Samuel2023).

For all therapists/supervisors there is the issue of how to remain informed and aware of potential societal events and how these can act as triggers for individuals linked to their specific trauma memories and formulation. If these are related to racism, the onus is on the therapist to create an environment where the patient feels comfortable sharing these, but the therapist will need to take responsibility for broaching this and checking this out with the patient. This should be mirrored in supervision with the supervisor cultivating cultural safety for supervisees. We would encourage therapists to use supervision as a space to ensure self-care in addition to as a place for knowledge and skill development as we discuss below.

In terms of the case management aspects of clinical supervision which are aimed to support safe and high-quality care for patients, supervision needs to include discussion of the various identities of the patient including ethnicity. Whilst both parties have some responsibilities for this, the onus is on the supervisor to ask and ensure that this becomes routine. A supervisory environment needs to be created where ethnicity and potential experiences of racism can be discussed and explored without any sense that these will be minimised or dismissed due to the attitudes or lack of knowledge of the supervisor. Both parties need to be open and curious to unpack the personal meanings of an event for a patient and how these might differ depending on prior experiences and identity. For example, the personal meaning of being pulled over by two white policemen on a quiet road in the early hours and asked to leave your vehicle is likely to be very different for a white therapist than it is for a Black patient. Supervisors also need to be cognisant of ongoing events in society that may impact on supervisees and patients from a minoritised ethnicity that could change the salience or emotional impact of discussions.

With respect to the skill development role of clinical supervision, supervision needs to be a place where supervisee and supervisor feel comfortable acknowledging skill gaps and role-playing skills that either need developing or where a supervisee belief may need testing out. As we have already discussed, both therapists and supervisors can lack skill and confidence in discussing ethnic identity or racism. Practising questions and discussions around this give the supervisee a chance to try out and evaluate the impact of different ways of discussing this.

Finally, the impact on the supervisors themselves (especially if from a minoritised ethnicity) when discussing racism within PTSD (and wider) needs to be acknowledged and supported in their own supervision of supervision. For a wider exploration of the discussion of racism and racial trauma within supervision, please see Pieterse (Reference Pieterse2018) and the suggestions for supervisors to work through the series of reflective questions provided.

Conclusion

This paper has provided practical clinical guidance and case illustrations to demonstrate how CT-PTSD can be adapted to ensure that it is an effective treatment for the re-experiencing of traumatic events where racism is part of the experience.

We suggest that specific knowledge around racism is needed (and a related willingness to have potentially uncomfortable conversations around racism), plus an element of reflection and understanding of one’s own racialised ethnicity. However, most of the skills required are similar to those required for other traumatic incidents. Therapists need to ask in detail about individual meanings, avoid making assumptions and be alert to the possibility that our own discomfort around certain topics does not cause us to avoid discussing elements of the trauma in sufficient detail, discussing in supervision, or ensuring experiences of racism are considered in the formulation and addressed using the core CT-PTSD interventions as needed.

Further research is clearly required to ensure that a clear understanding of racism is embedded within our models of PTSD and associated questionnaires and therapist training.

Key practice points

-

(1) PTSD where racism has been part of the index event can be addressed using standard CT-PTSD with adaptations, if appropriate care is taken to ensure specific considerations are addressed.

-

(2) The therapist has a responsibility to ensure that personal meanings (especially those linked to shame or anger) are identified and addressed. This may be complicated by various processes which act as barriers to detailed discussion around racism, but therapists can facilitate this by avoiding making assumptions and by asking directly in a sensitive manner.

-

(3) Therapists will need to avoid making assumptions around the experience and meanings of events for those with a differing ethnicity (considering also other intersecting identities).

-

(4) Clinical supervision is especially important in this work, particularly for therapists from a minoritised ethnicity who may need support (given the impact these discussions may have on them), plus also for white therapists who may need support in practising talking about racism and including it within formulations.

-

(5) Clinical supervisors need to regularly engage in appropriate training and reflective practice on their own identities (considering cultural humility and curiosity) to ensure their provision of safe and effective supervision.

Data availability statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the patients and colleagues who have shared their experiences (even when painful) and helped our understanding of how to ensure we improve how we work with PTSD when there has been a racist component to the index trauma.

Author contributions

Leila Lawton: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Resources (equal), Supervision (equal), Validation (equal), Visualization (equal), Writing - original draft (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal); Richard Thwaites: Conceptualization (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Resources (equal), Supervision (equal), Validation (equal), Visualization (equal), Writing - original draft (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal); Emma Warnock-Parkes: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Resources (equal), Supervision (equal), Validation (equal), Visualization (equal), Writing - original draft (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal).

Financial support

Emma Warnock-Parkes was funded by the Wellcome Trust grant 200796 (awarded to A.E. and D.M.C.) and the Oxford Health NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests

Emma Warnock-Parkes and Richard Thwaites are both Editors of the Cognitive Behaviour Therapist. They were not involved in the review or editorial process for this paper, on which they are listed as authors. Leila Lawton is a visiting lecturer and trainer who receives payment for providing training around cultural adaptations in CBT. Her work also includes providing CBT within NHS settings.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.