Introduction

Moral injury is defined as the profound psychological, biological, spiritual, behavioural, and social distress arising from events which perpetrate, fail to prevent, or bear witness to acts that transgress an individual’s deeply held moral beliefs (Litz et al., Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash, Silva and Maguen2009). Notably, moral injury is often associated with spiritual distress, such as moral concerns, loss of meaning, self-condemnation, difficulty forgiving, loss of faith and/or loss of hope (Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Boucher, Oliver, Youssef, Mooney, Currier and Pearce2017). Examples of events where an individual may feel they have perpetrated an act that violates their moral code may include accidentally injuring another person in a motor accident, soldiers involved in operations where civilians were killed, political prisoners who betrayed their friends under torture, medics who missed a serious illness, or people who did not help others whilst escaping a terrorist attack (Murray and Ehlers, Reference Murray and Ehlers2021).

Moral injury can also arise when an individual experiences a deep sense of betrayal of what they perceive to be right by someone who holds authority in the situation (Shay, Reference Shay2014). Examples of being subjected to morally injurious behaviour of others include healthcare workers or military personnel who feel let down by self-serving superiors during emergency events. This may involve leaders placing junior staff in positions of danger without sharing the risks, or betraying their staff through failing to provide adequate equipment and/or health care support (Peris et al., Reference Peris, Hanna and Perman2022). Due to the nature of the roles, moral injury reactions are frequently recognised within military personnel and veterans (Peris et al., Reference Peris, Hanna and Perman2022), healthcare workers as particularly highlighted during the COVID-9 pandemic (Williamson et al., Reference Williamson, Murphy and Greenberg2020), police officers (Komarovskaya et al., Reference Komarovskaya, Maguen, McCaslin, Metzler, Madan, Brown and Marmar2011), journalists (Browne et al., Reference Browne, Evangeli and Greenberg2012) and child protection professionals (Haight et al., Reference Haight, Sugrue and Calhoun2017). However, moral injury is not limited to any specific profession (Murray and Ehlers, Reference Murray and Ehlers2021).

Moral injury is not a mental health disorder. However, it is seen to frequently contribute towards the development of many mental health difficulties, particularly post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) where it is reported as a barrier to recovery (Shay, Reference Shay2014; Williamson et al., Reference Williamson, Stevelink and Greenberg2018). Cognitive therapy for PTSD (CT-PTSD; Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) is a trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) recommended in clinical guidelines for PTSD internationally (American Psychological Association, 2017; International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies, 2019; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2018; Phelps et al., Reference Phelps, Lethbridge, Brennan, Bryant, Burns, Cooper, Forbes, Gardiner, Gee, Jones, Kenardy, Kulkarni, McDermott, McFarlane, Newman, Varker, Worth and Silove2022). CT-PTSD is found to be a highly acceptable and effective treatment for adults with PTSD in randomised controlled trial studies (Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Clark, Hackmann, McManus and Fennell2005; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Hackmann, Grey, Wild, Liness, Albert and Clark2014) and in routine clinical practice (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Gillespie and Clark2007; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Grey, Wild, Stott, Liness, Deale and Clark2013).

According to the 2021 census, over half of the population of England and Wales identify as religious (56.9%), with Christianity (46.2%) and Islam (6.5%) being the most cited religious groups (Office for National Statistics, 2022). Additionally, active-duty soldiers and veterans report particularly high rates of religion (Barlas et al., Reference Barlas, Higgins, Pflieger and Diecker2013; Maxfield, Reference Maxfield2014), a profession associated with high rates of moral injury and PTSD prevalence (Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Boucher, Oliver, Youssef, Mooney, Currier and Pearce2017; Youssef et al., Reference Youssef, Boswell, Fiedler, Jump, Lee, Yassa and Koenig2018). However, religious followers report concerns that secular help may weaken their faith and/or that they may be judged by their communities for seeking secular support (Mayers et al., Reference Mayers, Leavey, Vallianatou and Barker2007). Furthermore, therapists frequently report discomfort and limited training in addressing and incorporating religious beliefs into therapeutic work (Rosmarin et al., Reference Rosmarin, Green, Pirutinsky and McKay2013). This places help-seeking people from religious backgrounds at risk of feeling socially isolated from their faith communities, whilst simultaneously struggling to access professional support that ‘fits’ with their beliefs. Consequently, it is important that therapists can tailor CT-PTSD treatments to the needs of people holding religious beliefs.

Spirituality, which encompasses religious beliefs and practices, is a complex phenomenon that has the potential to be both a positive resource and/or an exacerbating factor for PTSD (Pearce et al., Reference Pearce, Haynes, Rivera and Koenig2018). Evidence illustrates that baseline spirituality predicts significantly lower PTSD severity at end of therapy (Currier et al., Reference Currier, Holland and Drescher2015). This is unsurprising considering that therapy seeks to build on a patient’s strengths and resources, and spiritual beliefs and practices are often a significant source of strength for many patients (Van Wormer and Davis, Reference Van Wormer and Davis2013). Religion has the potential to increase positive emotions, offer a sense of purpose and give meaning to adversity (Koenig, Reference Koenig2012). However, patients’ religious struggles are also seen to predict worse PTSD outcomes (Currier et al., Reference Currier, Holland and Drescher2015). Therefore, careful consideration is needed in how religion is integrated into treatment.

Growing research illustrates that religion-adapted psychotherapy, including CBT, is at least as effective, if not more, than conventional psychotherapy for mental health difficulties (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Heywood-Everett, Siddiqi, Wright, Meredith and McMillan2015; de Abreu Costa and Moreira-Almeida, Reference de Abreu Costa and Moreira-Almeida2022; Gonçalves et al., Reference Gonçalves, Lucchetti, Menezes and Vallada2015; Munawar et al., Reference Munawar, Ravi, Jones and Choudhry2023). A therapist mentioning religion as a value to consider in CBT is associated with a significant increase in Muslim patients’ perception of therapy credibility (Hassan et al., Reference Hassan, Lack, Salkovskis and Thew2024). However, the only existing manualised therapeutic approach for treating moral injury specifically in the context of PTSD for religious or spiritual patients is spiritually integrated cognitive processing therapy (SICPT; Pearce et al., Reference Pearce, Haynes, Rivera and Koenig2018). Although SICPT has shown promising results (O’Garo and Koenig, Reference O’Garo and Koenig2023), delivery requires specially adapted protocols, materials and therapist training, which are not routinely available in many clinical settings, such as the NHS.

The aim of this article is to provide practical guidance in how CBT therapists can interweave patients’ religious beliefs when treating PTSD related to moral injury in routine clinical practice, without requiring new protocols or specialist training. Anonymised clinical examples are used throughout to illustrate adaptations. The clinical examples draw primarily on work on perpetrator moral injury with patients identifying as Christian or Muslim, based on the authors’ clinical experiences. Therefore, the remaining article focuses on and refers to religion as a subset of spirituality. This is because religion is a way in which some people express their spirituality, but not all spiritual individuals are religious. However, it is hoped that the principles and ideas discussed are transferable across different religions, spiritual beliefs, and moral injury experiences.

The religious teachings and principles referenced within the case examples used are accurate representations of views given by real-life religious experts to the authors in the context of CT-PTSD work. The article builds on Murray and Ehlers’ (Reference Murray and Ehlers2021) article outlining the conceptual and clinical issues in understanding and treating moral injury-related PTSD using CT-PTSD. Of note, evidence suggests that spiritually competent CBT can be effectively delivered regardless of a therapist’s personal faith involvement or spiritual beliefs (Rosmarin et al., Reference Rosmarin, Green, Pirutinsky and McKay2013).

A cognitive model of PTSD and moral injury

The key premise to Ehlers and Clark’s (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) cognitive model is that PTSD develops when a person processes traumatic experiences in a way that creates a severe sense of threat in the present, despite the events themselves being in the past. The model proposes that the sense of current threat develops, and is maintained, by excessively negative appraisals of the event, poorly elaborated and disjointed memories, and maladaptive cognitive and behavioural coping strategies. The first process relates to idiosyncratic negative meanings that arise from the way in which a person has appraised a traumatic event and/or its aftermath. Secondly, the nature of the trauma memories means the memories are fragmented, disjointed, poorly elaborated, and inadequately integrated into their context in time, and alongside other autobiographical memories and subsequent information learned. This explains the ‘here and now’ quality to traumatic memories, and how trauma memories are easily triggered by similar sensory cues. Thirdly, the cognitive and behavioural coping strategies a patient uses to manage their sense of current threat can inadvertently increase symptoms and prevent change in appraisals or the nature of the memory, such as avoidance, memory suppression, rumination or substance misuse.

In this respect, although appraisals linked to moral injury may be accurate (e.g. ‘I have taken an innocent life’, ‘Someone I trusted betrayed me’), when a person generalises these appraisals beyond the isolated event, they can negatively impact their view of themselves, others or the world more broadly, often in context of their religion (e.g. ‘I have lost my soul and am unlovable’) (Murray and Ehlers, Reference Murray and Ehlers2021). Perceived internal threat can link to negative appraisals of one’s own behaviour in the events (e.g. ‘I am a failure’, ‘I have let God down’) which can lead to feelings of guilt, shame, and degradation. Conversely, perceived external threat can arise from negative appraisals about impending danger (e.g. ‘I am going to be punished by God’, ‘I am going to hell’) which can link to strong feelings, such as fear or anger. Furthermore, peoples’ prior experiences and cultural background can influence the development of these appraisals. Patients affected by moral injury often report a strong and/or rigid ethical and moral code, developed earlier in life, that makes it harder to then assimilate and accommodate events that transgress their moral standards (Murray and Ehlers, Reference Murray and Ehlers2021). In our experience, this struggle is very relevant when working with patients with strongly held religious beliefs.

Cognitive therapy for PTSD

In line with Ehlers and Clark’s (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) cognitive model, CT-PTSD aims to:

-

(1) Modify threatening appraisals of the trauma and its sequalae that are disproportionate to the event.

-

(2) Reduce re-experiencing symptoms by elaborating and updating the trauma memories and increasing discrimination between daily triggering stimuli and trauma memories (stimulus discrimination).

-

(3) Reduce cognitive and behavioural strategies that maintain a person’s current sense of threat.

Typically, therapy is provided over 8–12 weekly 60–90 minute sessions, but more sessions are offered if clinically indicated, for example if the person has experienced multiple traumas (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2005; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2018). Detailed guidance on how to conduct CT-PTSD is freely available at: https://oxcadatresources.com/. The resources include role-play videos, questionnaires and therapy hand-outs, but assume previous training in CBT.

Incorporating religious beliefs and practices into CT-PTSD in context of moral injury

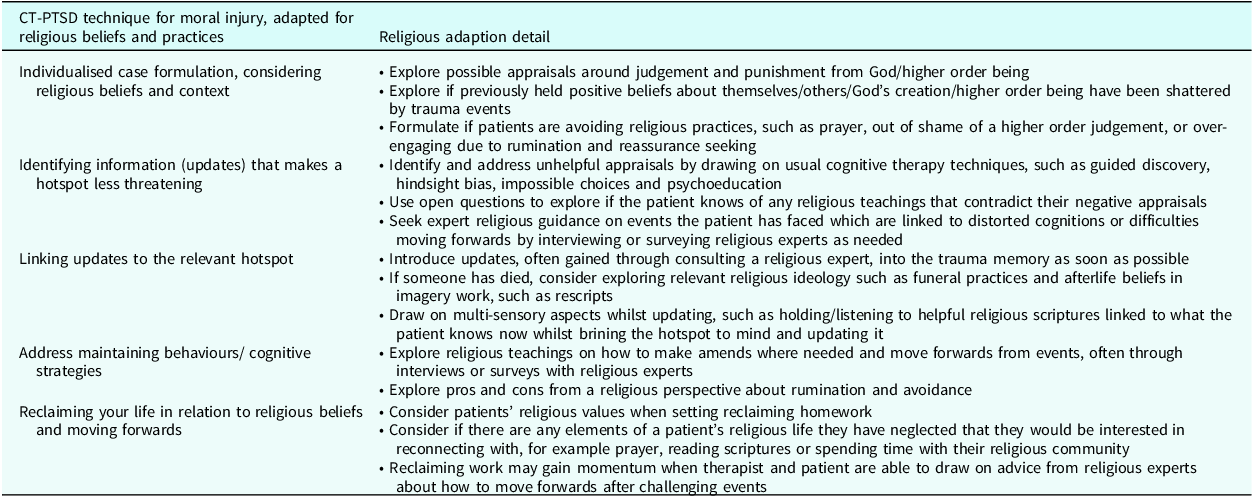

One of the strengths of CT-PTSD is that it is a case-conceptualisation approach, rather than protocol-driven. This means that formulations are individualised and treatment strategies can be flexibly applied to meet the unique needs of each person (Murray and El-Leithy, Reference Murray and El-Leithy2022). The following suggestions (Table 1) are examples of how core CT-PTSD techniques from Murray and Ehler’s (Reference Murray and Ehlers2021) moral injury guidance can be adapted to incorporate a patient’s religious context. However, these suggestions are by no means exhaustive. Furthermore, the order presented in this article may be adjusted depending on the needs of the patient and stage or focus of treatment tasks.

Table 1. CT-PTSD treatment strategies for patients with moral injury-related PTSD, adapted for religious beliefs and practices

Individualised case formulation

An early task in CT-PTSD is developing an individualised case formulation with the patient. This is not as detailed as Ehlers and Clark’s (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) formulation model. Instead, it provides a basic description of the main processes maintaining a patient’s PTSD and may be built on and added to as therapy progresses.

When working with PTSD in the context of moral injury, patients’ existing moral code, linked to family and cultural influences, often influence significant trauma appraisals (Murray and Ehlers, Reference Murray and Ehlers2021). Religious and spiritual beliefs can form an important part of a patients’ cultural context and influences. Therefore, time taken to explore them can help to build a culturally sensitive and meaningful formulation for the patient (Carlson and González-Prendes, Reference Carlson and González-Prendes2016).

Beck (Reference Beck2016) provides a comprehensive guide for when, and how, to explore issues of culture, spirituality and religion in CBT. Beck (Reference Beck2016) advises therapists to become comfortable opening initial discussions about these issues with all their patients in early sessions, after initial rapport has been established. However, these initial conversations may be brief at this stage. It is often the case that if religion is important to a patient, that they will refer to it early in therapy, and this can provide a natural opportunity to take their lead by asking a few additional questions about their beliefs and practices. Another way to open the discussion early in treatment might be when introducing ‘reclaiming your life’, by asking the patient if they would like to re-engage with any important spiritual or religious practices (Naz et al., Reference Naz, Gregory and Bahu2019). This can then be used as an opportunity to explore with patients the importance and meanings of these practices.

Appraisals associated with moral injury may emerge in the early parts of the therapy, for example when reviewing the results of the Post Traumatic Cognitions Inventory (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Ehlers, Clark, Tolin and Orsillo1999). However, they may emerge much later, for example after reliving a trauma memory and exploring the meanings associated with a ‘hotspot’. This affords the therapist the opportunity to explore in more detail how the patient’s appraisals of the trauma may be associated with their religious beliefs. Given the sensitive nature of this discussion, and especially when there are significant differences between the backgrounds of the therapist and patient, it can sometimes be preferable to make a mental note of the possible links, but perhaps wait to explore them in more detail once a stronger alliance has developed.

Some ideas of questions to open conversations about religion are listed below:

-

• We’ve talked about how moral injury is the extreme psychological distress humans experience when we act in a way/see others acting/are subjected to acts that go against our sense of what is right and wrong, often due to being forced or having no other options. For some, our sense of right and wrong can be influenced by religious beliefs. I’m wondering if this is the case for you at all?… How true is this for you?… Do you have any religious beliefs that we should consider in our formulation we are mapping out?

-

• As you’ve mentioned that you are religious, I’m wondering in what way this influenced your view of the world/other people/yourself whilst growing up?… Did these beliefs change at all after the trauma?… In what way?

-

• For some people, if they grew up believing in a divine creation or believing they were a good [insert religious follower], these beliefs can often feel threatened or shattered by traumatic events they later experience. How true is this for you? Is this something you relate to at all?…

It is important to note that a formulation is a work in progress. It is common that high levels of shame and guilt can prevent a patient from initially disclosing key appraisals. Therefore, it is important for therapists to continuously model a non-judgemental attitude to build trust with a patient. As therapy progresses, it is important that the therapist keeps building the formulation in collaboration with the patient. In our experience, appraisals linked to moral injury events and religious beliefs are often only fully disclosed once a patient feels able to trust that the therapist will hold unconditional positive regard. Therefore, the therapist must have realistic expectations for initial sessions, knowing that the formulation will evolve and be added to as the therapeutic rapport builds. To model a non-judgemental attitude, a neutral, curious stance is important, along with continuous validation of a patient’s distress and the impossibility of the situations they have found themselves in.

Religious patients who have historically believed in a loving God/higher order being, or seen themselves as a well-meaning religious follower, may be more susceptible to traumas shattering trust in themselves, the world and/or divinity (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Janoff-Bulman, Reference Janoff-Bulman1992). Alternatively, perhaps if they had a prior sense of never being good enough for God’s love, patients’ may see their trauma as confirmation of previously held negative beliefs about themselves (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). A therapist is encouraged to curiously explore how religious practices impact distress, using Socratic questioning (Padesky, Reference Padesky1993). If it is formulated that repetitive reassurance seeking through religious practices is maintaining a patient’s anxiety and rumination, it may be helpful for the patient to seek expert religious guidance on the moral dilemma (see later section on practical considerations for seeking advice from religious experts). However, for others, religious practices may be a positive way to cope and manage through adversity and can be mapped into the formulation as a protective factor.

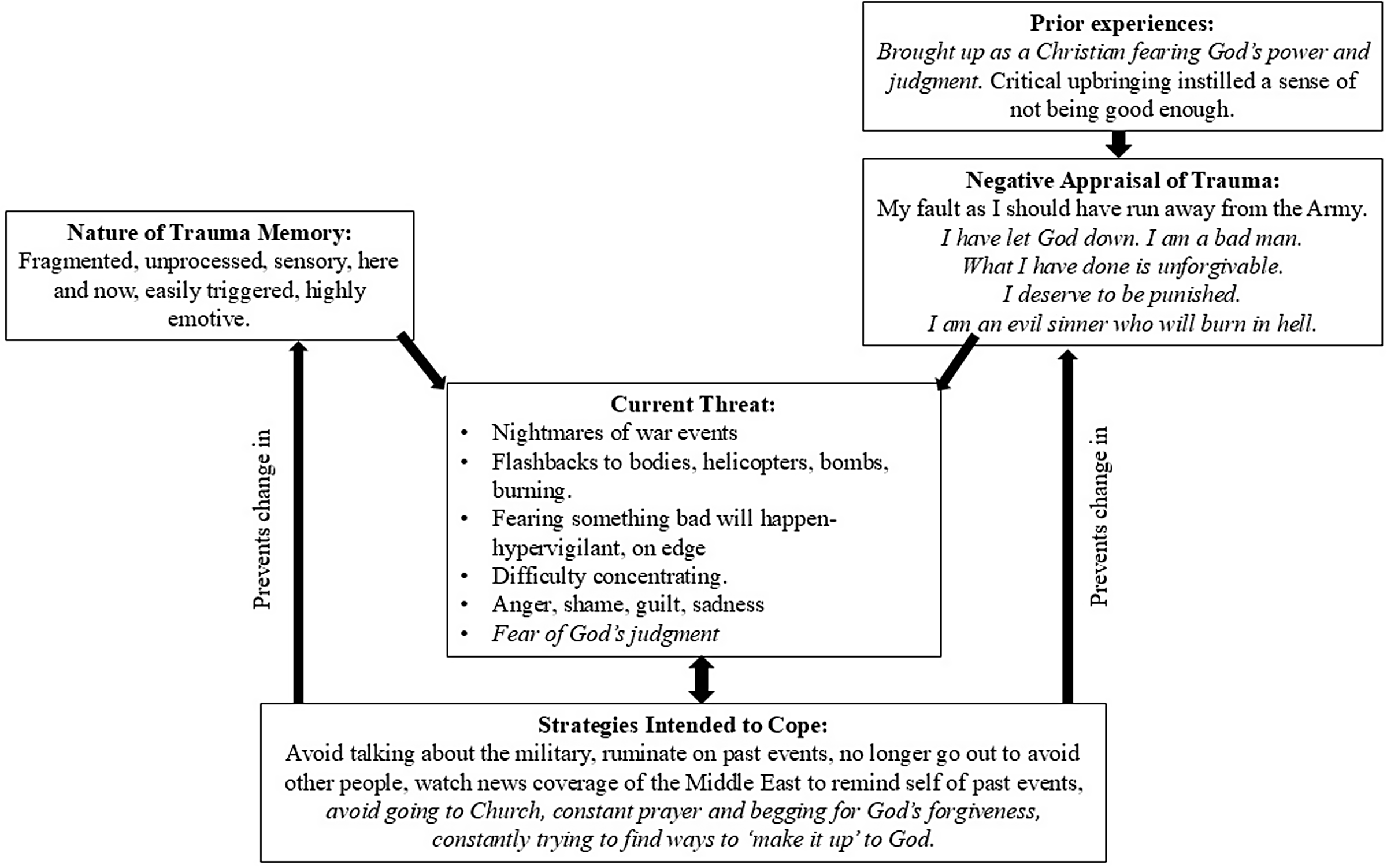

Figure 1 illustrates a PTSD formulation of ‘Ali’. Ali grew up in the Middle East in a Christian culture at a time of conflict and political unrest. His upbringing gave him a strong sense of God’s transcendence, instilling in him a sense of awe and fear of God’s power. He received a lot of criticism from his caregivers growing up, giving him a sense of never being good enough. As a young man he was conscripted and enrolled to fight in the Iraq–Iran conflict under compulsory military service, against his wishes. After a period of fighting on the front lines he managed to escape and travelled to the UK to seek asylum. After settling in the UK he began ruminating on his past actions in combat, which fed a sense of shame. Over time he became very fearful of God’s judgement, believing ‘I am an evil sinner who will burn in hell’. His fear of God’s judgement amplified his sense of current threat and drove further avoidance and reassurance seeking behaviours. He stopped going to Church. This meant he became disconnected from his spiritual life and Christian community, reconfirming the belief ‘I have let God down as I am a bad man’. He avoided reading his Bible but repetitively prayed for God’s forgiveness. His constant prayer fed a sense of doubt that he had been forgiven, fuelling further prayer and further anxiety. He continuously ruminated on what he could do to make it up to God and spent his time closely monitoring news coverage of the Middle East as self-punishment to remind himself of what he had been a part of, which maintained his distress and triggered more experiencing symptoms.

Figure 1. Example formulation of a Christian veteran ‘Ali’. Italics highlights the incorporation of religious beliefs.

Identifying information (updates) that makes a hotspot less threatening

A patient’s idiosyncratic meanings, associated with the worst moments of the trauma memory (‘hotspots’), are identified through imaginal reliving or written trauma narratives. Updates, which represent new perspectives and information that were not available to the patient at the time of the trauma, are then identified using cognitive therapy techniques and Socratic questioning. Examples of helpful cognitive techniques are: exploring thinking errors, creating responsibility pie charts, discussing psychoeducation about behaviours related to moral injury and seeking advice in imagery using adaptive disclosure (Murray and Ehlers, Reference Murray and Ehlers2021). Cognitive techniques are also used to identify and challenge disordered appraisals, and where cognitions of responsibility are accurate, to support a patient to accept responsibility and find ways of moving forwards.

However, when a patient’s key trauma appraisals relate to religious beliefs that are of significance to them, it is important that the corresponding updates are also linked to the patient’s religious point of reference. Without doing so, the updating work will lack salience as it will not be anchored in the patient’s context. This can be done through using open, Socratic questions to explore if the patient knows of any religious teachings, scripture references or theology that speak to or contradict some of their negative appraisals. The therapist can use this as an opportunity to model to the patient that they are not the expert, inviting the patient to share and teach the therapist about their religion. For example, ‘I am mindful that you know a lot more about your religion than I do, so I apologise in advance if I am asking a silly question, but I am wondering if you have ever heard of any teachings from [insert relevant religion] which might take a different view to your fears of judgement or teach of forgiveness? I only ask as I understand religious theology can be quite complex and nuanced to understand’.

If a patient reports uncertainty at this point, our experience has found it can be valuable to seek advice from respected religious experts through interviews or surveys (see later section on practical considerations for seeking advice from religious experts to set this up). People with PTSD, and particularly moral injury, often withdraw from their community, meaning they miss out on opportunities to hear others’ opinions on the events they are trying to make sense of. Particularly within religious communities, some people report feeling unable to discuss their mental health difficulties within their places of worship due to fears of stigma or judgement (Ciftci et al., Reference Ciftci, Jones and Corrigan2013; Wiffen, Reference Wiffen2014). Therefore, many patients will be grappling with moral and spiritual dilemmas in isolation, and this is something spiritually competent CT-PTSD can work to address.

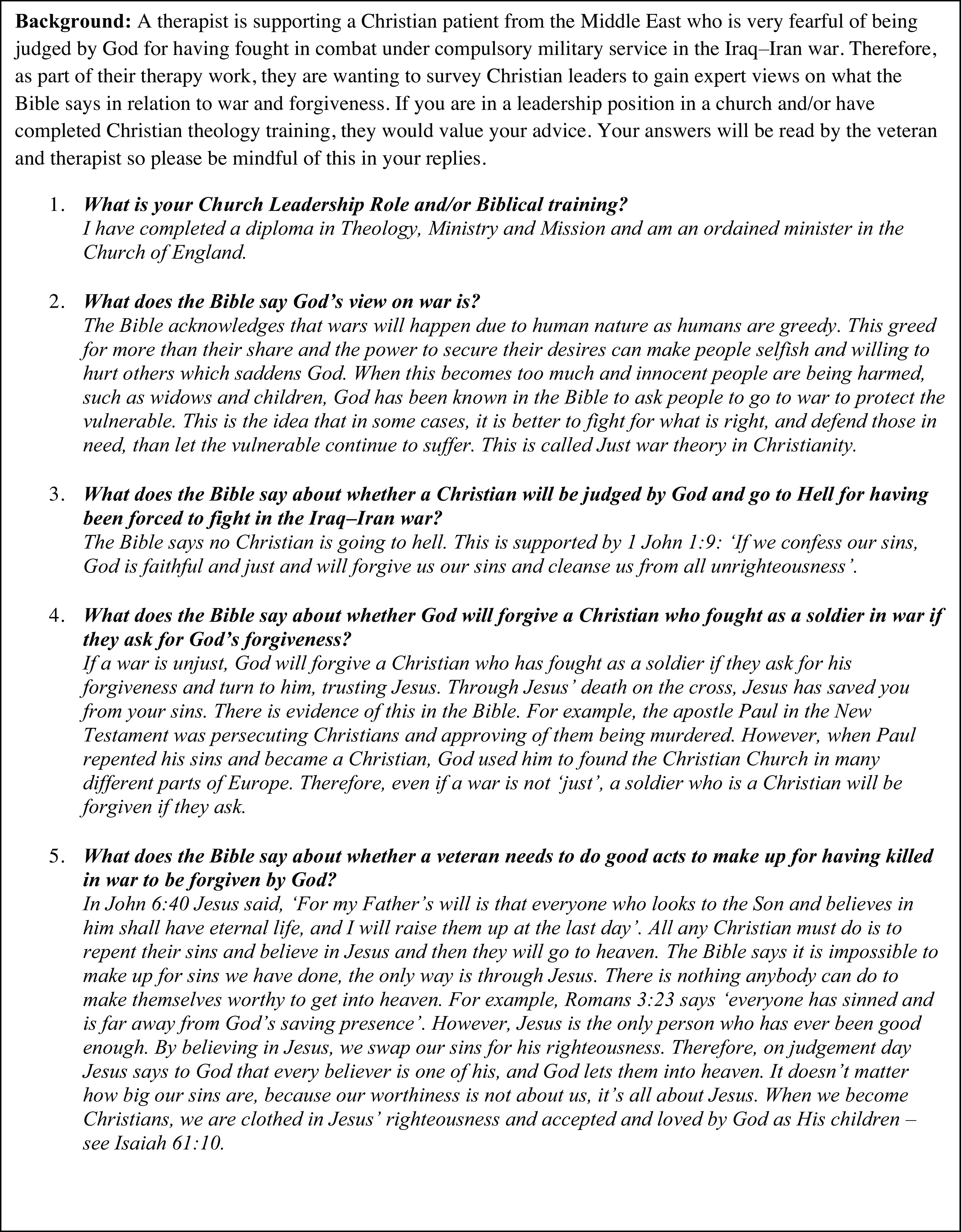

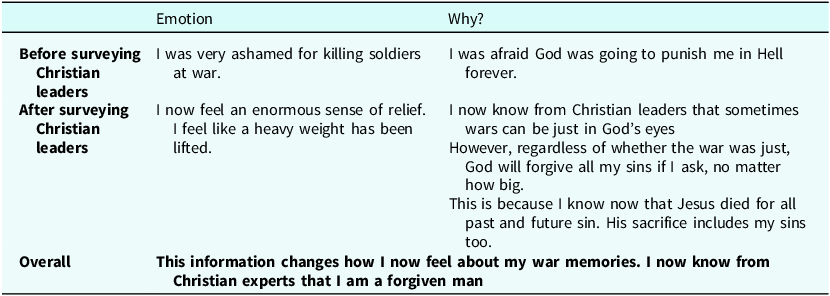

After agreeing that Ali wanted to seek expert advice on the topic of war and forgiveness, the therapist and Ali designed a survey for Christian experts, linking the questions to fears and beliefs from his formulation. This was because Ali felt too apprehensive to interview an expert directly, and so a survey was agreed as an alternative method which allowed him to ask questions but remain anonymous. Ali said he would define an expert as any Christian Church leader who had undergone theology training. It was agreed helpful to survey leaders across different denominations of Christianity, as Ali did not closely align to any denomination. Therefore, the survey was completed by a range of leaders including Catholic Priests, Church of England Vicars and Methodist and Baptist Ministers. An example survey response from one of the Christian leaders is shown in Fig. 2 to illustrate the questions asked and types of answers received. The service paid for the survey responses to be translated into Ali’s native language as Ali did not read English. Translation was used because responses were too detailed for an interpreter to read out in full during the session and for Ali be able to process and retain. The translated survey responses became a key relapse prevention resource at the end of therapy, that Ali could refer to if he was struggling with re-emerging PTSD symptoms. Although translation of the survey had a modest additional financial cost, it was agreed important in supporting his equity of access to all the treatment components.

Figure 2. Example survey response from a Christian leader advising Ali about God’s forgiveness and making amends.

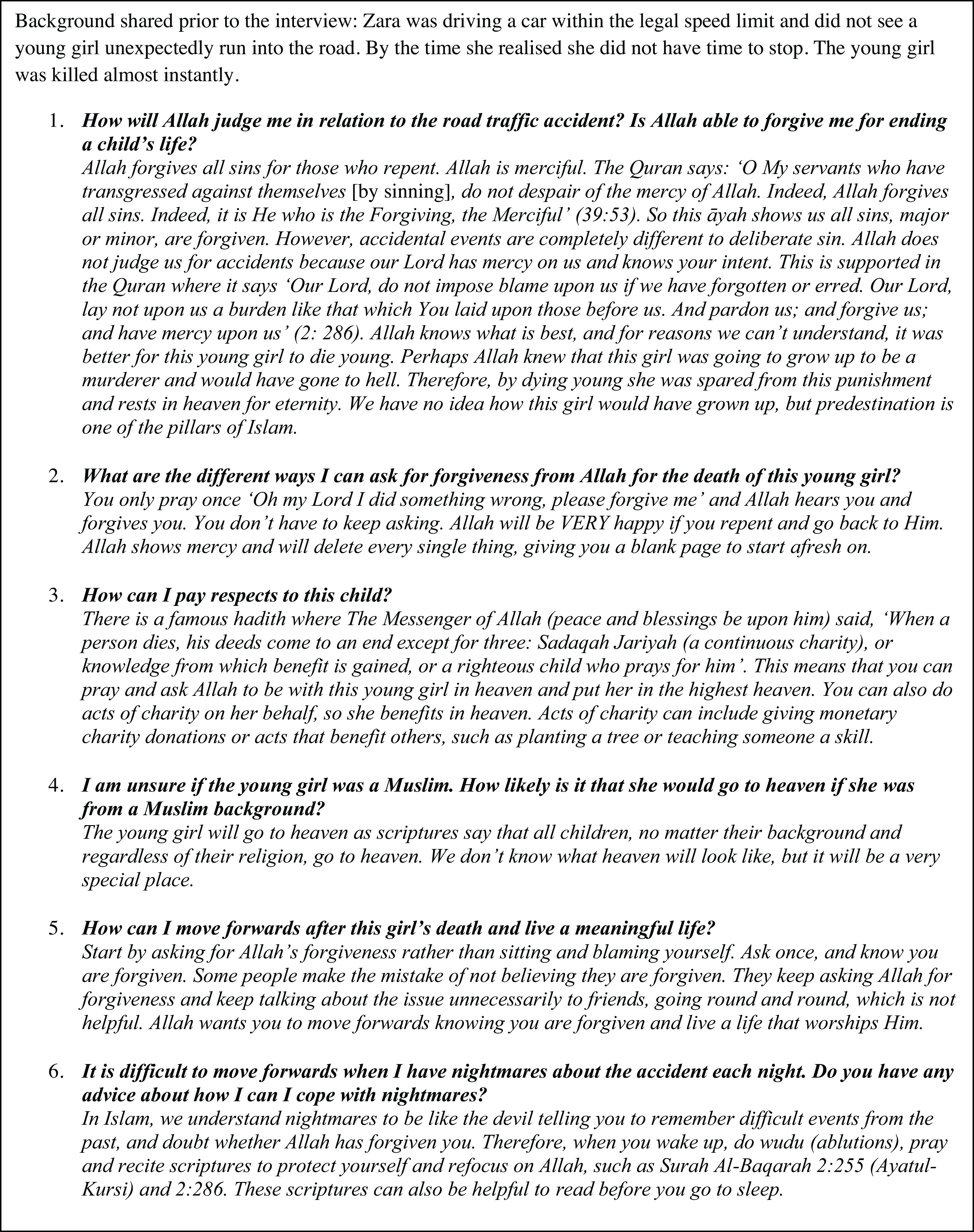

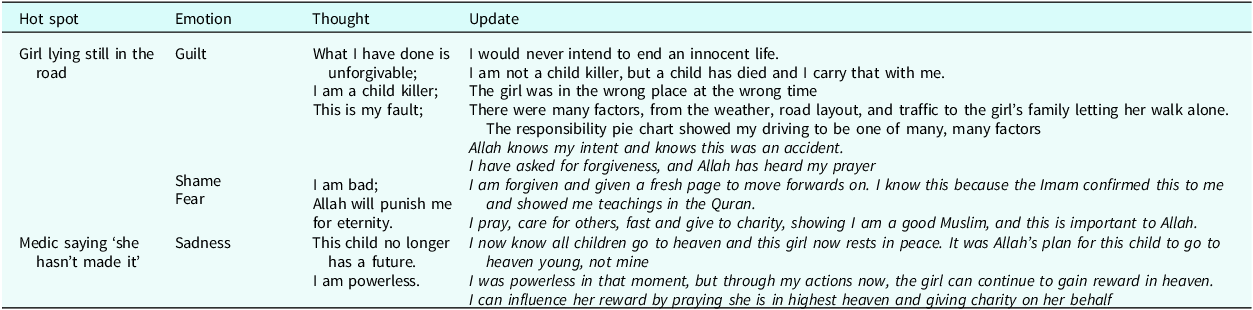

‘Zara’ grew up with a positive sense of herself and a strong sense of right and wrong linked to her faith as a Muslim. However, her self-view was shattered by a road traffic accident where the vehicle she was driving accidentally killed a young child pedestrian who ran out into the road unexpectedly. Consequently, she believed she would be punished by Allah, leading to a high level of shame and distress. During therapy, it was highlighted that Zara was uncertain whether Allah would take into consideration the accidental nature of her actions when judging them. As she knew little about the background of the girl who died, she was very anxious about the child’s life after death and unsure how to move forwards. Therefore, the therapist and Zara collaboratively created a set of questions to ask a Muslim expert, who they invited to join a subsequent therapy session for an interview. Zara defined a Muslim expert as a scholar, someone who studies the Quran, or an Imam, a leader in a Mosque. Figure 3 provides a summary of the questions asked and answers received from an Imam from Sunni Islam, who was also a Muslim scholar.

Figure 3. Summary of Zara’s interview with an Imam regarding questions about Allah’s forgiveness, afterlife and moving forwards from the road traffic accident.

Linking updates to the relevant hotspot

Once updating information has been identified for a hotspot, the updates are integrated back into the original trauma narrative. This can be done by the patient recalling and emotionally reliving the hotspot in their mind’s eye, whilst simultaneously reminding themselves of the updating information, or reading the hotspots aloud with the updates within the narrative. Updated hotspot charts are usually generated beforehand to guide this process. Rescripting is often used in addition to convey the cognitive updates and felt sense through imagery. Incorporating specific afterlife beliefs and religious practices into rescripts, can link updating work into a patient’s wider cultural beliefs, increasing the salience of the work. Therapists may often encourage patients to draw imagery rescripts out to consolidate them and create a resource they can refer to in blueprinting.

The session after Zara interviewed the Imam, she was guided by her therapist to generate updates in her own words for her original appraisals on her hotspot chart. The updates were based on Zara’s take-home points from the Imam which she summarised to the therapist (Table 2). The newly gained knowledge that Zara was forgiven was very significant at updating her original appraisals relating to shame and guilt. In addition, discovering that all children go to heaven, no matter their background, was a new revelation for Zara. This led to her rescripting the hotspot image of the child suffering to visualising the young girl now at peace. The majority of Islam is aniconic, which means followers are often opposed to the use of icons or visual images to depict religious figures or any living creatures more generally. Therefore, Zara did not draw her rescript but saw it in her mind’s eye. Zara was encouraged to bring the new rescripted image of the child to mind when she found herself ruminating on the death.

Table 2. Example hotspot chart with updates for Zara, a Muslim woman in a road traffic accident where a young girl was killed (italics indicate updates derived from interviewing the Imam)

Therapists are encouraged to incorporate different modalities into updating work, not just rely on verbal updates, to increase updating effectiveness (see PTSD training video ‘Examples of Updating Memories in CT-PTSD Using Different Modalities’ on https://oxcadatresources.com/). Patients may find playing back a recorded clip of a religious expert teaching a new, helpful perspective linked to an update, or playing a piece of religious music which reminds them of a specific teaching, such as God’s love, useful at this point in updating. These resources can be pre-arranged and set up with the therapist in advance, so they are on hand when bringing the updates to mind.

Zara held open a copy of the Quran on a passage the Imam taught her about forgiveness (39:53) whilst closing her eyes and bringing the hotspot to mind of the child lying in the road. She was then prompted by her therapist to open her eyes and looked down at the passage when she was bringing in the update that Allah is merciful in His judgements. This brought a multi-sensory aspect to the updating work, increasing its power.

Table 3 illustrates how the key learnings from surveying Christian leaders were summarised for Ali. This material was incorporated into his trauma memory updates. In particular, the belief of ‘I am a forgiven man because I accept Jesus’ salvation’ was a powerful antidote to his original belief ‘I am an evil sinner’. As Ali did not speak English, an interpreter was used in all therapy sessions. Therefore, when creating Table 3 together in face-to-face therapy, the interpreter wrote a translation underneath in Ali’s native language. However, when therapy sessions were delivered on video call, the therapist used Google Translate live in session to provide an instant, basic translation for key phrases and pasted this below written English text.

Table 3. Example update summary for Ali after he surveyed Christian leaders

Addressing maintaining behaviours/cognitive strategies

People with PTSD cope with the sense of current threat by adopting behavioural and cognitive strategies, such as avoidance, reassurance seeking, hypervigilance and safety behaviours. These strategies block the reappraisal of distressing beliefs and prevent the processing of memories (Murray and Ehlers, Reference Murray and Ehlers2021). Therefore, the importance of exploring and formulating the function of these strategies is crucial. If these strategies are linked to religious practices and beliefs, it is important the therapist is not questioning of patient beliefs themselves, but curious to understand and support the patient to access expert religious advice where needed. Religious experts can also be useful in advising patients on how to make amends if the patient has done something repairable, or how to move forwards from irreversible events.

Ali’s formulation highlighted how he was using repetitive prayer to seek reassurance from God, which continued to feed his sense of dread. He also described ruminating for hours about how he could make it up to God, which, because it provided no new insights, maintained his sense of himself as ‘beyond redemption’. Additionally, he described watching upsetting press coverage of ongoing conflict in the Middle East to ‘punish’ himself, linked to his self-hate. Instead, Ali learnt from surveying Christian leaders that God forgives anyone who turns to Him for forgiveness. He was surprised to learn that there was nothing he could do to make himself worthy of heaven, other than accepting Jesus (Fig. 2). The Christian leaders explained that Jesus died on the cross to save humanity from their sins, and so by accepting Jesus’ salvation, Ali was worthy of eternal life in heaven on Jesus’ merit. Ali created a series of flash cards to summarise these key messages with supporting Bible quotes he found helpful. Ali was encouraged to read these when he noticed the urge to pray repetitively for forgiveness, watch the news or noticed he was trying to make the past up to God.

Following her interview with the Imam, Zara set herself the homework task of privately praying and asking Allah for forgiveness for the death of the young girl. This was something she had deliberately avoided since the accident and had fed her sense of shame. She reported this to be a very significant act, providing an immense sense of relief and ability to move forwards. The Imam was able to provide confidence that Allah would hear her prayer and forgive her. Furthermore, by asking the Imam for advice on managing nightmares, Zara learnt that she could recite scriptures to protect herself from rumination and refocus on Allah upon awakening, such 2:255 (Ayatul-Kursi) and 2:286. This supported her to manage her distress and strengthened her spiritual life (Fig. 3).

Reclaiming and making amends

Reclaiming previously valued activities after a trauma is a central element to CT-PTSD and starts early in therapy. As therapy and religion work towards the same goals of increasing a person’s sense of identity and encouraging social support networks (Weisman De Mamani et al., Reference Weisman De Mamani, Tuchman and Duarte2009), it is likely to be important to consider someone’s religious life within reclaim work.

Early on in therapy Ali had started working towards leaving the house and going on walks to connect him with his values of nature. However, learning from the Christian leaders that the Bible calls him to rejoice in Jesus’ salvation and celebrate his identify as a forgiven man gave his reclaim work cultural momentum (Isaiah 61:10, ‘I delight greatly in the Lord; my soul rejoices in my God. For He has clothed me with garments of salvation and arrayed me in a robe of His righteousness’). The therapist was then able to explore with Ali how a forgiven man would express his gratitude to God and live day to day off the back of the survey responses. With advice from the Christian leaders, Ali began re-building connections with his Christian community again by gardening for his local church.

When patients hold genuine responsibility for traumatic events, conversations in therapy can focus on how the patient can come to a place of acceptance and move forwards with their lives through focused acts of reparation (Murray and Ehlers, Reference Murray and Ehlers2021). Different religions hold different practices that may be useful to draw on to inform this work. Therefore, consulting religious experts specifically around making amends or moving forwards may be an important part of spiritually competent CT-PTSD for moral injury.

For Zara, her faith as a Muslim gave her practical avenues for expressing her grief for the child and a sense of being able to make amends. After consulting the Imam, she began donating to a road safety charity on behalf of the young girl (Sadaqah) and praying to Allah for forgiveness and mercy for the child, as she believed this would move the child into the highest heaven. These actions helped Zara rebuild a sense of being a caring person with good intentions, despite being in the wrong place at the wrong time the day of the road accident. Zara was able to use these religious practices to care for the child in afterlife.

Practical considerations for seeking advice from religious experts

Introducing the idea

Conversations about religion can be aided by a therapist having a basic insight into a patient’s religion to build therapist confidence asking initial open questions. There are many accessible multi-faith resources for healthcare professionals freely available online, such as NHS Scotland’s (2021) guide (https://learn.nes.nhs.scot/50422/person-centred-care-zone/spiritual-care-and-healthcare-chaplaincy/resources/). However, therapists should be mindful that there are many nuances within religion, and so a position of curiosity, not expertise, must be assumed regardless of a therapist’s knowledge. Using the example of Ali, a therapist may suggest the initial idea of consulting a religious expert by saying: ‘I’m noticing that it plays on your mind a lot that God may judge you for the events that have happened. I’m mindful that I am not an expert in Christianity, and you’ve said there are many things you also don’t know about in your faith. Therefore, I am wondering if it might be helpful for us to get some expert advice here?… In therapy we often seek specialist advise from experts on specific situations. For example, if a Christian patient has questions that relate to their faith, we can organise for a Christian expert to talk to them in therapy, who knows much more than we do about the Bible. Do you think this would be helpful for us to explore some of your fears?… If so, who do you think would be best placed to support us… And how would you refer to this person (Pastor, Priest, Minister, Leader, Vicar, Elder, Parson, Deacon, etc)?’.

Supporting patient apprehensions

If a patient is anxious about seeking expert advice, but agrees it would be important to them, it may be helpful to map out the pros and cons of consulting an expert and explore if there are any ways this could feel more accessible for them. Patients may have blocking beliefs which can be identified and addressed in session. For example, they may have concerns about anonymity or negative responses which could interact with a therapist’s own apprehensions (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Kerr, Warnock-Parkes, Wild, Grey, Clark and Ehlers2022). However, many concerns can be addressed through collaborative agreement about who is approached and how the therapist and patient set this up.

If a patient does not already know a leader or expert within their community that they would feel comfortable approaching, the therapist can offer to use their own contacts to identify someone suitable. In our experience, consulting a religious expert the patient does not know is often more acceptable to patients. This is because the expert is less likely to have mutual connections to the patient, reducing the social risks for the patient. Alternatives could also be considered if the patient is too hesitant about revealing their identity to speak to an expert directly. Instead, sending experts a written survey to complete, or the therapist interviewing the expert with pre-agreed questions and recording it for the patient to watch back, could be considered. Alternatively, the ability to videocall an expert who lives in another geographical area can increase patient confidence, as the risk of bumping into the expert is reduced, or even eliminated.

However, facilitating the patient to speak directly with an expert is often our preferred option. This is because the process allows for the therapist and patient to clarify understanding with the expert in a live discussion, reducing the potential of misunderstanding or uncertainties remaining afterwards. We have also found that hearing a compassionate expert communicate religious teachings around forgiveness or God’s love directly, can bring a warmth to the information that may not be communicated through a written survey answer, helping a patient connect with the felt sense of an update.

Planning questions

Questions are developed collaboratively with the patient in a pre-meeting planning session. It is important that the questions link to the CT-PTSD formulation, and specifically target the idiosyncratic meanings, and associated religious beliefs, driving the sense of current threat. Surveys or interviews may purely consist of questions, or present a brief vignette based on the patient’s experience along with associated questions. Questions are best kept clear, brief and succinct; see the guidance of Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Kerr, Warnock-Parkes, Wild, Grey, Clark and Ehlers2022) on designing CBT surveys. However, interviewing an expert ‘live’ also gives opportunity to clarify the information and opinions as they are discussed, and ask ad hoc follow-up questions as the discussion grows.

Searching for a religious expert

NHS Trusts usually have a chaplaincy service where trained religious leaders from a range of faiths are available to support patients with spiritual struggles. Within NHS Trusts, chaplains are usually trained in pastoral care, giving them skills in supporting people with their emotional wellbeing, as well as spiritual. Alternatively, a therapist can ask colleagues or friends from the same religious background to the patient if they are able to recommend an expert, particularly one that would be sensitive and caring to a patient in distress. Minimal information needs to be disclosed when searching for an expert to protect patient confidentiality. For example, ‘I am working with a Christian patient who has some questions related to their mental health that they would like to ask a Christian leader. As I know you belong to a Christian community, I was wondering if you would be able to recommend anyone who might be willing to speak to my patient as a one-off? We’re looking for someone who would be sensitive to mental health difficulties’.

When searching for an expert, we recommend the therapist agrees in advance with the patient any criteria. For example, would the patient be open to hearing from any expert within their religion, or does the expert need to align with the same denomination or sect as the patient? In our experience of this, the importance is therapist curiosity. For example, when working with Zara: ‘I’m mindful you know a lot more than I do about Islam, so I’m going to need your guidance. Who do you think would be best placed to answer our questions?… If we found someone willing to talk to us, would you want them to be from a certain sect, as I know there are often different groups within religions that differ from one another?’.

Once a therapist has identified a willing expert to interview, we generally recommend the therapist meets with them individually in advance to talk through the rationale, session plan and address any concerns on their part. This helps establish that the expert feels confident answering the types of questions the patient has highlighted, and the therapist feels satisfied the expert will be sensitive to the confidential nature of the conversation and the emotive impact on the patient. To do this the therapist will need to gain consent from the patient to share the patient’s background with the expert to establish their suitability. In our experience, investing time to find and prepare suitable experts increases the likelihood of a helpful and successful encounter, albeit requiring some additional therapist time in the short term. Over time therapists can build up a ‘bank’ of experts they have worked alongside, reducing the preparation time needed in the long term. With the patient’s agreement, it may be useful for the therapist to share some basic psychoeducation with the expert about what PTSD is and what CT-PTSD entails (information sheets can be found at https://oxcadatresources.com under PTSD therapy materials). This enables the expert to appreciate the context of their involvement.

In addition, it is crucial the therapist is respectful when communicating with religious experts and tries to schedule meetings around spiritual practices, such as prayer times or religious services. It may also be useful to gain the expert’s prior consent to record the interview with the patient if the patient would like to refer to the recording afterwards as a resource. In our experience, a patient may not be able to take in all the information they are given in an interview. Therefore, being able to play the recording back afterwards allows them to maximise learnings from the conversation. Furthermore, we have found that patients often find great reassurance and comfort in the words of a religious expert. Therefore, having a recording the patient can play back often becomes a useful resource they are able to refer to, for example when updating hotspots and as a blueprint resource.

Reflections from working with religious patients

Difference and the therapeutic relationship

Everyone differs in a range of ways, from visible to invisible difference, from voiced to unvoiced differences (Burnham, Reference Burnham and Krause2012). However, the multiple parts of our identity (such as gender, ethnicity, sexuality and religion) intersect to create a substantially unique viewpoint and experience of the world for each of us (Butler, Reference Butler2017; Collins, Reference Collins2000). For example, two Christian patients, one white British man and one black African woman, will have different social and political experiences of living in the UK as a Christian. Therefore, although this article has focused solely on the dimension of religion, each patient and therapist will bring to therapy a unique positioning more nuanced than ‘religious’ or ‘non-religious’ with multiple, intersecting dimensions. Acknowledging these differences between a therapist and patient’s multiple identities, and giving each other permission to correct misunderstandings, can help foster a collaborative therapeutic relationship where religious beliefs can be respectfully explored.

Approaching these discussions can be understandably anxiety-provoking for therapists, and where there are constraints on time and sessions, they may feel the urge to rush or omit this process. Despite this, investing a little extra time to explore differences of viewpoint often enhances the collaborative alliance, and can make therapy more efficient and effective (Naz et al., Reference Naz, Gregory and Bahu2019). Below are some ideas for how therapists may open these conversations with a patient and invite their feedback:

-

• I have been holding in mind our work and I am mindful we are from different backgrounds and different in terms of gender/ethnicity/culture and religious experiences [insert relevant other differences]…

-

• Therefore, I know I will be likely to make incorrect assumptions, mistakes or mis-interpret things you might say at times. When I do, it’s important you feel you can correct me so we can work together. Although, I have knowledge about PTSD, only you have lived your experiences and so your knowledge is really important…

-

• I wonder have I got anything wrong already?… Have there been any times so far in our therapy work when I have misunderstood your cultural or religious views?…

-

• Do you think there have been any times when you have misunderstood me?…

-

• At times I may ask questions, not because I have a specific opinion, but because I am curious if there are any other perspectives we should consider that might be important. However, please do interrupt me if you think we aren’t going in a helpful direction…

Therapist personal beliefs

CBT therapists often report discomfort in incorporating religion into therapeutic work (Rosmarin et al., Reference Rosmarin, Green, Pirutinsky and McKay2013). This is understandable considering that they bring to their work a range of personal religious beliefs, assumptions and experiences, ranging from negative to positive, which may or may not agree with a patient’s. However, spiritually competent therapy can be increased through education and support (Rosmarin et al., Reference Rosmarin, Green, Pirutinsky and McKay2013). Therefore, the importance of supervision, where therapists can recognise and reflect on their own belief systems and intersecting identities, can enable a therapist to remain curious and patient-centred when discussing religion, regardless of therapist personal beliefs. Exercises such as cultural genograms (Shellenberger et al., Reference Shellenberger, Dent, Davis-Smith, Seale, Weintraut and Wright2007) or Salient Circles (Buchanan, Reference Buchanan2020) can be useful aids for this. Below are some suggested questions that a therapist may find useful to explore in supervision or private reflection to aid self-reflexivity, developed from Butler (Reference Butler2017):

-

• What are your intersecting identities, and how does religion feature in these?

-

• Which identities are often present in therapy? Which are more silent? And does this differ in supervision?

-

• What is unspoken? Why might this be? What shuts down our curiosity about our patient’s religious beliefs?

-

• What privileged positions do we hold that may silence our patients?

-

• What viewpoints do you hold that could be seen as unfavourable or threatening by your patients?

Consistent evidence suggests that religion-adapted psychotherapy protocols can be as effective (Lim et al., Reference Lim, Sim, Renjan, Sam and Quah2014), or even more effective than standard protocols (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Heywood-Everett, Siddiqi, Wright, Meredith and McMillan2015). Of note, this effect appears to be independent of the therapist’s own religious or spiritual beliefs (de Abreu Costa and Moreira-Almeida, Reference de Abreu Costa and Moreira-Almeida2022). This challenges the misconception that an atheist, agnostic or therapist of a different religion to a patient is unable to deliver spiritually competent CT-PTSD.

Final thoughts

Using ‘downward-arrowing’ and Socratic questioning skills can help therapists to identify and formulate when a patient’s religious beliefs and practices may interact with trauma-related negative appraisals and cognitive/behavioural coping strategies. Using a curious stance, therapists can support patients to learn and draw on religious information of importance to them and integrate this into their treatment. Services can also flourish through close collaboration with religious institutions (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Phiri and Naeem2019), which this article supports through consulting religious experts in the community when needed. In our experience, a therapist does not position themselves as a religious advisor, but a facilitator of discussion and learning, incorporating a patient’s religious beliefs and practices when relevant. When such information comes from respected figures within a patient’s religious framework, we have found the information holds greater weight for a patient than if it came from a therapist. This highlights the value in consulting religious experts, even if the therapist themselves know religious teachings to signpost the patient to.

Key practice points

-

(1) Moral injury is the psychological distress that arises following events that transgress a person’s moral and ethical code. If religion is an important part of a patient’s identity, their religion is likely to inform their moral code and be relevant to their distress.

-

(2) When moral injury arises with PTSD, it can be formulated using Ehlers and Clark’s (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) cognitive model of PTSD. A therapist can use Socratic questions to consider a patient’s religious beliefs and practices within this formulation.

-

(3) CT-PTSD techniques for memory and reclaiming life work can be adapted to incorporate a patient’s religious beliefs and practices. This can be done by a therapist using a curious stance and supporting a patient to seek expert religious guidance where needed. A therapist does not position themselves as a religious advisor, but a facilitator of discussion and learning.

-

(4) Therapists should use supervision to develop and draw on their self-reflexivity to enable a patient’s religious identity to be considered within therapy.

Data availability statement

There are no data in the article.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to the memory of Dr Hannah Murray, whose expert supervision, teaching and publications have informed this article. We are grateful to our colleagues at the Traumatic Stress Service, Op Courage South East and University of Surrey who have supported patient and therapist learning over the years. A particular mention is given to Reverend Ronald Day, Yasser Hamad Albasri and Ashley Williams for their religious expertise in reviewing this article. We are grateful to our patients for developing our insights of PTSD, moral injury and religion.

Author contributions

Katherine Wakelin: Conceptualization (equal), Project administration (lead), Resources (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing - review & editing (equal); Sharif El-Leithy: Conceptualization (equal), Project administration (supporting), Resources (supporting), Writing - original draft (supporting), Writing - review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This article received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

The authors abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Ethical approval was not required for this article. Advise from NHS Information Governance was followed. ‘Ali’ and ‘Zara’ gave permission for the use of their clinical information. Real names and identifying details have been removed and/or changed. Their clinical examples have been amalgamated with several different patients and fictional elements added to provide full anonymisation.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.