CBT in acute care

If we are to extend the impact of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) across service settings, we need to adapt our psychological formulation and intervention skills to meet people’s needs in these different contexts.

UK acute mental health services aim to reduce risk, facilitate recovery and discharge people promptly (British Psychological Society, 2021; Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2016). Anyone who has worked on acute wards knows that it is often hard to facilitate safe and timely recovery and discharge, for a range of reasons including bed pressures, problems with clinical flow, and workforce shortages (British Psychological Society, 2021; Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2016).

People with psychosis tend to have prolonged hospital admissions (Crossley and Sweeney, Reference Crossley and Sweeney2020; Lay et al., Reference Lay, Lauber and Rössler2006), despite the now 20-year-old NHS Implementation Plan and target of 32-day maximum average stays (Department of Health, 1999; NHS England, 2019). In a recent retrospective cohort study of a large inner-city mental health NHS Trust, a psychosis diagnosis was associated with longer admissions, with an average length of stay of over two months (Crossley and Sweeney, Reference Crossley and Sweeney2020). Admissions can come at high personal (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Ford, Jellicoe-Jones and Haddock2013; Berry et al., Reference Berry, Ford, Jellicoe-Jones and Haddock2015; Loft and Lavender, Reference Loft and Lavender2016), and economic costs (Ride et al., Reference Ride, Kasteridis, Gutacker, Aragon Aragon and Jacobs2020), and are often experienced as unsafe and untherapeutic (Care Quality Commission, 2017; Care Quality Commission 2019).

We need to improve the quality of in-patient care in the UK (Care Quality Commission, 2019). In addition to addressing systemic problems of resource and clinical flow (British Psychological Society, 2021; Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2016), relationships with ward staff are likely to be key to effecting such change (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Haddock, Kellett, Roberts, Drake and Barrowclough2016; British Psychological Society, 2021). People with a diagnosis of schizophrenia in a forensic setting identified relationships with staff and family as central to their recovery (Laithwaite and Gumley, Reference Laithwaite and Gumley2007).

The purpose of psychological formulation is to articulate the intra- and interpersonal processes that maintain distress – that keep people ‘stuck’ in problematic cycles of thoughts, feelings and behaviours – as a basis for change if the person so chooses. In acute care, formulations can be developed with the ward team to make sense of the individual’s experience, facilitate therapeutic staff–patient interactions, and improve recovery outcomes (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Haddock, Kellett, Roberts, Drake and Barrowclough2016; British Psychological Society, 2021). This is particularly important given that in-patient staff often report being unsure how best to support people who struggle to seek and accept help (Boniwell et al., Reference Boniwell, Etheridge, Bagshaw, Sullivan and Watt2015).

The limited evidence to date suggests that psychological approaches can improve psychosis, anxiety and depression, and reduce readmissions (Paterson et al., Reference Paterson, Karatzias, Dickson, Harper, Dougall and Hutton2018), but that significant challenges to embedding interventions in routine clinical practice seriously limit impact (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Haddock, Kellett, Roberts, Drake and Barrowclough2016; Paterson et al., Reference Paterson, Karatzias, Harper, Dougall, Dickson and Hutton2019). Novel interventions or forms of service delivery designed for acute care therefore need to consider issues of implementation as a priority.

Attachment style affects cognitive, affective and behavioural patterns in psychosis

Bucci et al. (Reference Bucci, Roberts, Danquah and Berry2014) argue that we can improve mental health care by taking account of people’s attachment styles. As infants, we are pre-disposed to form emotional bonds with caregivers, which increase likelihood of survival and capacity to explore the world (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1969). Broadly responsive and consistent caregiving is associated with a secure attachment style, characterised by beliefs that one is safe, others are helpful, and emotions are manageable (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978). Inconsistent caregiving is associated with an insecure-anxious attachment style, characterised by beliefs about being unsafe and unloved, others being unreliable, and emotions being overwhelming. Where caregivers have often been physically or emotionally absent, infants may develop an insecure-avoidant style, with beliefs about the need to cope alone, that others are rejecting (sometimes harmful), and that emotions are overwhelming. At times of distress, people who are securely attached are able to manage difficult feelings and seek help when needed (Kobak and Sceery, Reference Kobak and Sceery1988). People who are anxiously attached have learnt to escalate emotional expression (e.g. by ruminating or catastrophising) as a means of seeking the help they need, and those who are avoidantly attached suppress their emotions and are self-reliant even when needing help (Mikulincer and Shaver, Reference Mikulincer, Shaver, Mikulincer and Shaver2016). Our attachment styles endure into adulthood, although may be shaped by later relationships (Fraley and Duggan, Reference Fraley, Dugan, Thompson, Simpson and Berlin2021).

Psychosis is associated with insecure attachment in cross-sectional (Korver-Nieberg et al., Reference Korver-Nieberg, Berry, Meijer, de Haan and Ponizovsky2015; Wickham et al., Reference Wickham, Sitko and Bentall2015) and longitudinal studies (Gumley et al., Reference Gumley, Schwannauer, Macbeth, Fisher, Clark, Rattrie and Birchwood2014a). People with psychosis who also have an insecure attachment style are likely to have more severe symptoms (Ponizovsky et al., Reference Ponizovsky, Nechamkin and Rosca2007), struggle to engage in recommended treatments (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Barrowclough and Wearden2007; Dozier, Reference Dozier1990; Gumley et al., Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannaeur and MacBeth2014b; Tait et al., Reference Tait, Birchwood and Trower2004), and have longer hospital admissions (Ponizovsky et al., Reference Ponizovsky, Nechamkin and Rosca2007). Given the need to improve the quality of in-patient care, it would seem sensible to target the needs of people with psychosis and insecure attachment, who are typically more unwell, less well engaged, and admitted for longer periods.

Acute wards are usually busy and can be unpredictable. Staff often experience competing and conflicting demands which can result in high levels of stress and uncertainty regarding their role and how best to offer support (Wyder et al., Reference Wyder, Ehrlich, Crompton, McArthur, Delaforce, Dziopa and Powell2017). In these environments, staff responses may inadvertently compound the impact of insecure attachment on people’s recovery. However, when nursing staff are able to be available and responsive, this has a considerable impact on the person’s sense of safety and wellbeing (Cutler et al., Reference Cutler, Sim, Halcomb, Moxham and Stephens2020).

What does CBT have to offer?

If we are to utilise the principles of CBT to improve the quality of in-patient care for people with psychosis, we need models that incorporate the cognitive, affective and interpersonal behaviours characteristic of insecure attachment patterns. Ideally, we would also want to anticipate staff responses where these unwittingly contribute to the maintenance of distress and delay recovery.

We can use cognitive behavioural models to map out these processes, but such formulations do not typically capture key interpersonal processes, and may be too complex for people to hold in mind in busy acute settings. Safran (Safran, Reference Safran1990a, Reference Safran1990b; Safran and Segal, Reference Safran and Segal1996) criticised traditional CBT for paying insufficient attention to interpersonal processes when seeking to account for mental health problems, given the innately interpersonal nature of human beings. Safran sought to integrate these processes in cognitive theory and practice, highlighting the role of ‘interpersonal schemas’ – generalised representations of self-other relationships based on formative experiences that guide information processing and behaviours in social interactions. These interpersonal schemas drive self-perpetuating cycles of thoughts, feelings and behaviours that will be familiar to CBT therapists. For example, the belief ‘others judge me negatively’ is likely to elicit anxiety and behaviours such as wariness or avoidance of others. This in turn may evoke reciprocal responses in other people such as withdrawing (possibly having judged the person to be socially uncomfortable) and giving up on attempts to be friendly, thereby maintaining the schema either directly or indirectly (in the absence of disconfirmatory evidence).

These ‘cognitive interpersonal cycles’ may be particularly useful in formulating psychosis, which is often experienced as inherently interpersonal – paranoia constitutes interpersonal threat beliefs, and hallucinations are by definition experienced as other. Additionally, the explicit mapping of others’ responses is likely to be valuable in ward settings where staff–patient interactions can become problematic (cf. Berry et al., Reference Berry, Haddock, Kellett, Roberts, Drake and Barrowclough2016; British Psychological Society, 2021). Finally, the simplicity of the cycles is well suited to demanding environments where we can easily lose sight of more complex formulations. The model of interpersonal process has proved theoretically valuable but (perhaps surprisingly) has had limited impact on routine clinical practice to date.

Currently, there are no established psychologically informed approaches to working with people with psychosis and insecure attachment in acute care (Bucci et al., Reference Bucci, Roberts, Danquah and Berry2014). The cognitive interpersonal cycles provide a means of delivering CBT in these settings by clarifying the cognitive, affective and interpersonal behaviours associated with anxious and avoidant attachment, and means of addressing these both directly (with people with psychosis) and indirectly (with ward staff).

Attachment-based CBT models for psychosis in acute care

We developed the attachment-based CBT models drawing on the intra- and interpersonal responses to distress predicted by attachment theory (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1969; Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1973; Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1988), means of engendering a sense of interpersonal safety (Arriaga et al., Reference Arriaga, Kumashiro, Simpson and Overall2017), and the cognitive interpersonal cycles proposed by Safran (Safran, Reference Safran1990a, Reference Safran1990b; Safran and Segal, Reference Safran and Segal1996). Importantly, Safran (Reference Safran1990b) described interpersonal schema as cognitively oriented elaborations of the ‘internal working models’ of attachment theory (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1969). We have elaborated these further by making explicit the emotion regulation strategies used in anxious and avoidant insecure attachment (clarifying likely behaviours used ‘on the inside’ as well as ‘on the outside’), and how these might be enacted by people with psychosis in acute care.

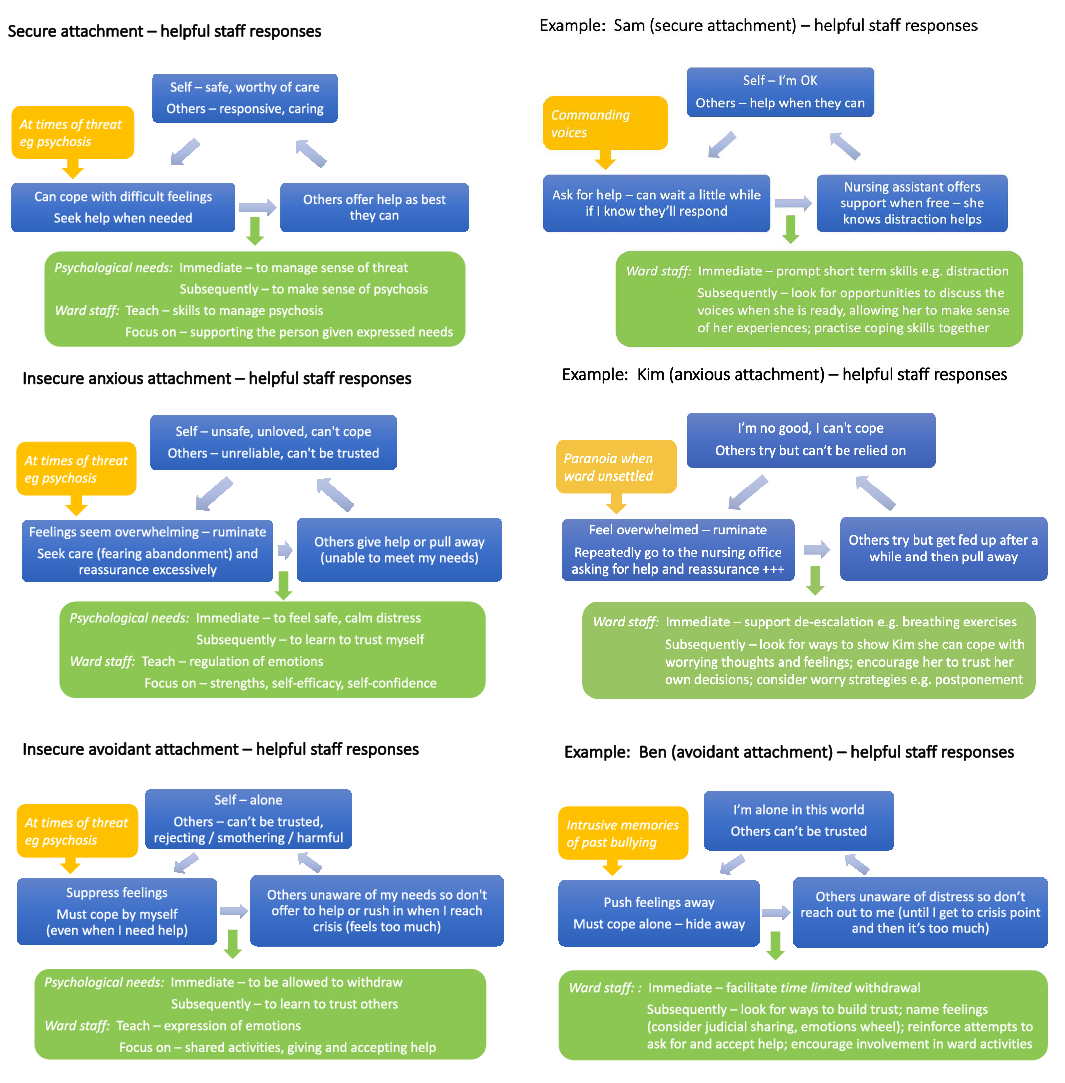

Figure 1 demonstrates attachment-based CBT formulation models. The cognitive interpersonal cycles are represented in blue. The top blue box names self and other beliefs (each inherently interpersonal but kept separate for simplicity). When triggered by distress (such as hallucinatory experience, paranoid thoughts, or threatening ward environments – in orange), these beliefs are activated along with attachment-congruent emotional regulation and behavioural responses. These in turn elicit reciprocal responses (or ‘pulls’) from others which are likely to reinforce the person’s beliefs about self and others, either directly or through the absence of disconfirmatory evidence. In green, we have outlined the person’s immediate and subsequent psychological needs, and how ward staff might respond most effectively to facilitate these.

Figure 1. Attachment-based CBT formulation models

The models highlight the importance of supporting people with insecure-anxious attachment to learn to (1) trust themselves, (2) regulate emotions, and (3) make use of help more effectively. People with insecure-avoidant attachment can be supported to learn to (1) trust others, (2) express emotions, and (3) request and accept help when needed.

The models can be used to develop a shared understanding of the person’s intra- and interpersonal needs, developed jointly with the person themselves wherever possible, as the basis for shaping more effective emotion regulation and relational responses to support recovery and appropriate discharge (cf. Arriaga et al., Reference Arriaga, Kumashiro, Simpson and Overall2017).

Patient and Public Involvement

The UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) recommend collaboration with key stakeholders to inform the development of complex interventions (Skivington et al., Reference Skivington, Matthews, Simpson, Craig, Baird and Blazeby2021). The introduction of psychological approaches in acute care settings constitutes a complex intervention, involving staff knowledge and skill development, embedding behaviour change in routine practice, and addressing significant implementation barriers (cf. Bucci et al., Reference Bucci, Roberts, Danquah and Berry2014; Paterson et al., Reference Paterson, Karatzias, Dickson, Harper, Dougall and Hutton2018). Novel service models and psychological interventions designed for acute services need to consider implementation with key stakeholders as a priority.

We ran a series of four stakeholder Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) consultations to consider an attachment-based approach to acute care using the proposed models. These were attended by people with psychosis, family members and ward staff, and included (1) an open session run with the local NHS Trust lead for service-user involvement, (2) a session with the Trust service-user involvement group,Footnote 2 and (3) two sessions with ward staff likely to be using or supporting the models with wider staff teams – psychologists, psychology assistants and a ward manager. Six people with lived experience of psychosis, two family members, and five ward staff took part in the four PPI sessions.

With participants’ consent, two people kept detailed notes for each PPI session. As usual for PPI meetings, the sessions were not recorded to encourage people to talk openly about their experiences and opinions. The two note keepers compared records immediately following the sessions to produce a final agreed meeting record.

We drew on qualitative methods to identify key points across PPI sessions. The agreed meeting records were analysed in NVivo version 12 using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). An inductive, open coding approach was used to generate codes, which were then grouped into themes. Codes and themes were revised repeatedly in an iterative process using frequent comparison with meeting records to ensure they reflected the data. Codes and themes were discussed in the research team to aid reflexivity and agree the final themes.

Participants expressed often strong feelings about psychological care on acute wards and reflected on implementation issues for the adapted models. We identified three over-arching themes: (1) need to improve staff–patient interactions on wards; (2) continuity in staff–patient relationships is key to recovery; and (3) advantages and barriers to an attachment-based CBT approach. Table 1 outlines the main areas of discussion, key points made, and implications for practice.

Table 1. Key themes highlighted in PPI sessions

The ward environment was identified by people with psychosis, family members and ward staff as a key barrier to implementation. Suggestions for addressing this focused on means of integrating the models into established ward review systems, practical forms of implementation, and shifting the responsibility for recovery more towards the person with psychosis – a more collaborative approach which may also strengthen staff–patient interactions and continuity of care.

Summary and conclusion

Acute mental health care remains unsafe and untherapeutic across much of the UK (Care Quality Commission, 2017; Care Quality Commission, 2019). Psychological interventions are a key component of plans to address these problems (British Psychological Society, 2021), and a focus on staff–patient relationships as a means of facilitating recovery is likely to be most effective (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Haddock, Kellett, Roberts, Drake and Barrowclough2016; British Psychological Society, 2021; Bucci et al., Reference Bucci, Roberts, Danquah and Berry2014; Laithwaite and Gumley, Reference Laithwaite and Gumley2007).

Many people with psychosis struggle both with their psychotic experiences, and with attachment-congruent thoughts, feelings and behaviours that exacerbate distress, elicit unhelpful responses from others, and delay recovery. In ward settings, the intra- and interpersonal patterns associated with the activation of the attachment system are intensified as people are typically at their most unwell, and ward environments can be unpredictable and experienced as threatening (Stenhouse, Reference Stenhouse2013; Wood and Pistrang, Reference Wood and Pistrang2004).

Attachment-based CBT models articulate these interpersonal processes simply and identify targets for intervention. However, the challenges of ward environments can jeopardise effective and sustained implementation of psychological approaches (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Haddock, Kellett, Roberts, Drake and Barrowclough2016; Paterson et al., Reference Paterson, Karatzias, Harper, Dougall, Dickson and Hutton2019). For this reason, we strongly recommend engagement with local stakeholders prior to implementation – depending on resources, this might involve formal PPI consultation, review with Trust service user groups, or discussion with ward managers and teams regarding potential benefits and means of addressing local barriers.Footnote 3 Once the ward team is engaged, any change to service provision is more likely to be maintained if woven into established governance systems such as ward reviews, psychology consultation sessions and reflective practice.

It should be noted that we ran PPI consultation sessions with a small number of people linked to just two NHS services. Wider consultation and qualitative research would be a useful next step, and might determine if this approach could be used in other settings, such as forensic and rehabilitation services, where interpersonal cognitive and behavioural processes can contribute to inconsistent provision of care, and so delay people’s recovery.

As psychological therapists, we need to adapt CBT models and skills to work effectively in different contexts. By naming the cognitive, behavioural and affective processes associated with insecure attachment, unhelpful interpersonal patterns can be recognised and reflected upon. All are then in a stronger position to adopt alternative responses in line with the attachment-congruent needs of the person. This is undoubtedly easier said than done, and we hope the formulation models described here will be of use to others seeking to effect similar changes in these settings.

Key practice points

-

(1) We can adapt CBT models to incorporate anxious and avoidant attachment styles, common to people with psychosis.

-

(2) We can use these models to identify intra- and interpersonal processes that delay recovery and discharge from acute mental health wards.

-

(3) Attachment-based CBT formulations may be helpful to guide more effective staff–patient interactions and thereby facilitate recovery in psychosis.

Data availability statement

Not applicable for this Service Model/Form of Delivery paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all who participated in the consultation groups described here.

Author Contributions

Katherine Newman-Taylor: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (equal); Sean Harper: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Tess Maguire: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Katy Sivyer: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Christina Sapachlari: Formal analysis (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Katherine Carnelley: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

Katherine Newman-Taylor is an Associate Editor of the Cognitive Behaviour Therapist. She was not involved in the review or editorial process for this paper, on which she is listed as an author. The other authors have no declarations.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS, and the INVOLVE guidelines for PPI.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.