Potentially morally injurious experiences (PMIEs), including ‘perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply help moral beliefs and expectations’ (Litz et al.,Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash and Silva1 p. 700), can result in significant psychological distress or moral injury.Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash and Silva1 Certain occupational groups may be at risk of exposure to work-related morally injurious events, including first responders, journalists and armed forces personnel. Moral injury is often associated with strong moral emotions related to the event, including guilt, anger and disgust,Reference Farnsworth, Drescher, Nieuwsma, Walser and Currier2 and can lead to distress and psychological difficulties. For example, in combat veterans, PMIEs is significantly associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and suicidal ideation.Reference Farnsworth, Drescher, Nieuwsma, Walser and Currier2, Reference Frankfurt and Frazier3 However, the psychological effect of PMIEs on those in non-military employment remains unclear. Most studies have exclusively examined moral injury in US armed forces personnel.Reference Bryan, Bryan, Morrow, Etienne and Ray-Sannerud4–Reference Nash, Marino Carper, Mills, Au, Goldsmith and Litz7 The few studies that exist indicate that those in non-military professions, such as police, can also experience moral injury after a PMIE.Reference Backholm and Idås8, Reference Komarovskaya, Maguen, McCaslin, Metzler, Madan and Brown9 The aim of this review is to examine the mental health outcomes associated with occupational PMIEs. We also examined potential moderators of effects to determine whether these influenced the magnitude of the associations between PMIEs and mental health outcomes. Studies examining moral distress, which is similar to moral injury, in healthcare professionals have found that exposure can cause psychological distress and burnout.Reference Lamiani, Borghi and Argentero10, Reference Oh and Gastmans11 As this concept has been extensively reviewed in recent years (e.g. and Lamiani et al.Reference Lamiani, Borghi and Argentero10 and Oh and GastmansReference Oh and Gastmans11), it was not included in our study.

Method

Search strategy

We conducted a computer-based search in December 2016 of the following psychological and medical electronic literature databases: Embase, PsychNet, Medline, PsycInfo, PILOTS, Google Scholar and Web of Science. The search terms were related to moral injury, mental health and occupation (see Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.55). In addition, key authors were contacted to request details of any further studies and reference sections of relevant review articles (e.g. Litz et al.,Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash and Silva1 Frankfurt and Frazier,Reference Frankfurt and Frazier3 and Dombo et al.Reference Dombo, Gray and Early12), book chapters and issues of journals (e.g. Journal of Traumatic Stress) were manually searched to identify any additional studies.

Eligibility criteria

Studies had to meet the following criteria to be considered for inclusion: a direct measure of exposure to PMIE incurred as a result of the participant's occupation, a standardised measure of mental health and statistical testing of the association between PMIEs and mental health. Measures of exposure to PMIEs were included if they asked about exposure to occupation-related perceived transgressions committed by the respondent and/or other individuals, or perceived betrayal by others, such as colleagues.Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash and Silva1–Reference Frankfurt and Frazier3

Studies were excluded on the following grounds: (a) the article was a review that did not offer new data or only presented qualitative analysis, (b) single case studies, (c) studies not written in English or (d) studies examining moral distress in nursing and medical professionals.

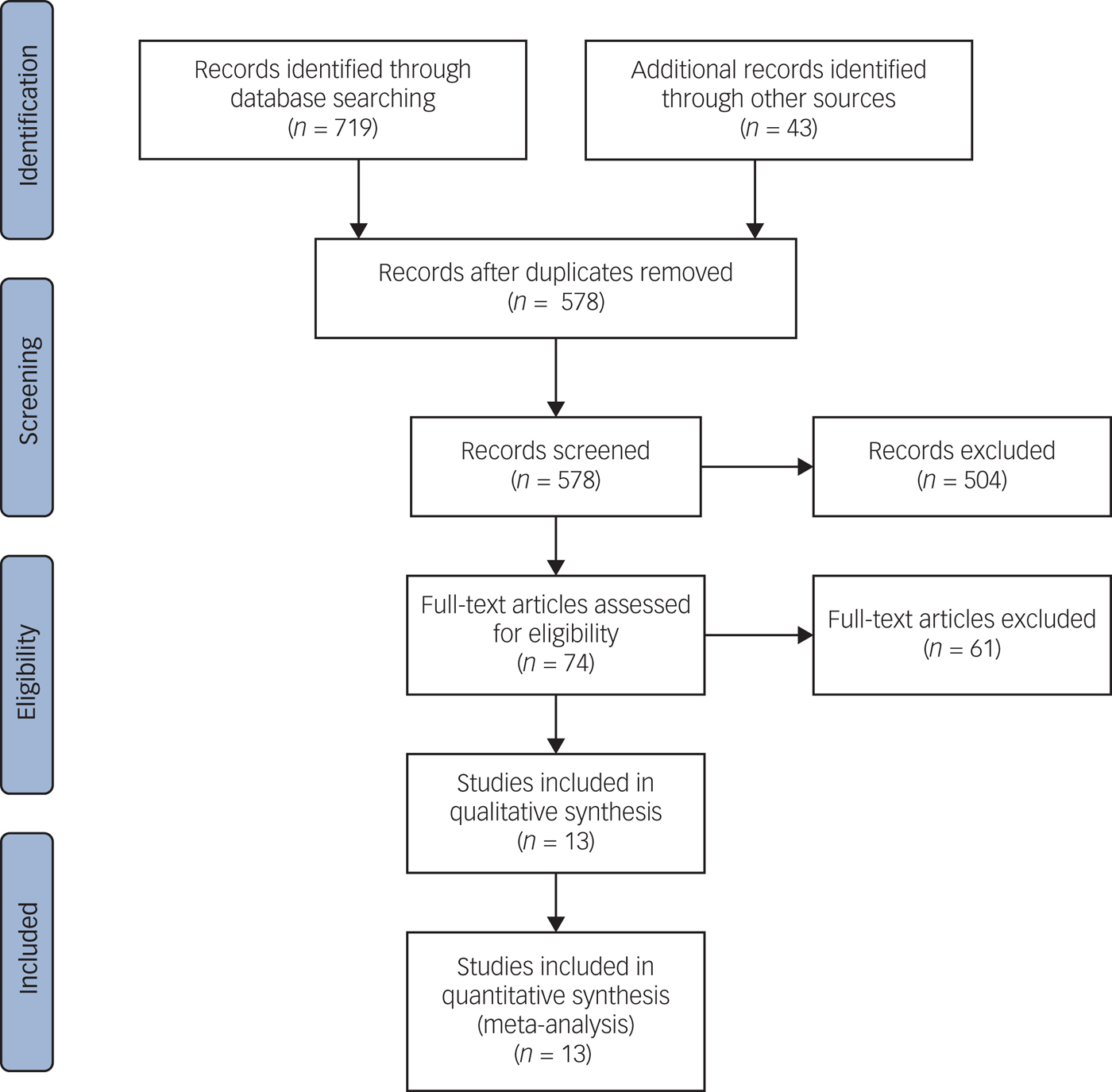

Two authors (V.W. and S.A.M.S.) independently screened articles and extracted data. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart (Fig. 1) delineates the review process.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Grp13 On two occasions, the same data were reported in more than one article. In such cases, results from the most comprehensive article were used.Reference Currier, Holland, Drescher and Foy14 The final sample consisted of 13 studies that met the inclusion criteria.

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each study, if available: (a) author name, (b) publication year, (c) study design, (d) study location, (e) type of PMIEs, (f) instrument used to assess the PMIE, (g) sample size, (h) gender distribution, (i) participant age, (j) assessment time points, (k) mental health disorder assessed, (l) mental health instruments/diagnostic criteria used, (m) time since PMIE, (n) findings and effect sizes and (o) any sources of bias or ethical issues. The data was extracted and assessed independently by two authors (V.W. and S.A.M.S.). Any discrepancies were checked and a consensus was successfully reached.

Quality rating

Two authors (V.W. and S.A.M.S.) independently assessed the methodological quality of all included studies by a seven-item checklist adapted from Ajetunmobi.Reference Ajetunmobi15 The highest possible quality score was seven, indicative of a better-quality study, with zero as the lowest possible score. Adapted items on the checklist include an evaluation of whether the study design was evident and appropriate, if random sampling of study participants was used to ensure all members of the examined population had an equal chance of being selected into the sample and if the analytic methods used were well described and appropriate. Studies were scored depending on the extent to which the specific criteria were met (with yes being one and no being zero) and we calculated a summary score for each study by summing the total score across all items of the scale (see Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). Agreement between authors was strong, with any disagreements resolved in a consensus meeting.

Table 1 Included studies sample characteristics, methods of assessment and quality ratings

aEffect size calculated by averaging across all moral injury (transgressions – self, transgressions – others, betrayal) and mental health comparisons for this study. Quality is the methodological quality score (range, 0–7). Three-item questionnaire refers to the three items used to measure potential moral injury event exposure relating to work tasks during the 2011 Norway terror attack informed by previous qualitative studies.

bDemographic information only provided for 131 participants.

BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory;Reference Beck and Steer23 BDI-II, The Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition; BEB, Battlefield ethical behaviours, a non-validated three-item questionnaire regarding unethical behaviour during deployment informed by previous research and expert opinion;Reference Wilk, Bliese, Thomas, Wood, McGurk and Castro22 BRS, The Brief Resilience Scale; BSI, The Brief Symptom Inventory; BSSI, Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation;Reference Dozois and Covin24 CAPS, The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale;Reference Blake, Weathers, Nagy, Kaloupek, Gusman and Charney25 CIHQ, The Critical Incident History QuestionnaireReference Weiss, Brunet, Best, Metzler, Liberman and Marmar26 with indices relating to killing/causing serious injury to others in the line of duty used to assess potentially morally injurious event exposure; CMHS, Cook–Medley Hostility Scale;Reference Han, Weed, Calhoun and Butcher27 DASS-21, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale;Reference Lovibond and Lovibond28 DDRI, Deployment Risk and Resilience InventoryReference King, King, Vogt, Knight and Samper29 with items relating to firing a weapon and killing an enemy used to measure potentially morally injurious event exposure; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Seven-Item Scale;Reference Spitzer, Kroenke and Williams30 IES-R, Impact of Event Scale Revised;Reference Horowitz, Wilner, Alvarez, Weiss, Marmar and Neal31 Interview, participants interviewed regarding morally injurious experiences with data coded when perpetration, witnessing or failing to prevent acts that transgressed veterans' moral beliefs was verbalised; ISEL, Interpersonal Support Evaluation List;Reference Cohen and Hoberman32 LASC, Los Angeles Symptoms Checklist;Reference King, King, Leskin and Foy33 MCS-CV, The Mississippi Combat Scale, Civilian Version;Reference Lauterbach, Vrana, King and King34 MIES, Moral Injury Event Scale, which measures potential moral injury event exposure related to three factors (transgressions – other, transgressions – self, betrayal); MIQ-M, Moral Injury Questionnaire Military Version, measure of potential moral injury event exposure during deployment based on previous theory and research of moral injury (an aim of this study was to validate the MIQ-M); MIQ-T, Moral Injury Questionnaire Teacher Version, non-validated, 12-item scale of potential moral injury event exposure to assess teacher's exposure to workplace violence (e.g. mistreatment of students; unable to prevent harm to students) and ethical dilemmas informed by theory and previous research of moral injury in other samples;Reference Currier, Holland, Rojas-Flores, Herrera and Foy17 Moral objection, non-validated questionnaire of potentially morally injurious event exposure informed by focus groups of combatants with experience of combat exposure in the West Bank and Gaza;Reference Ritov and Barnetz20 N/A, not available; PANAS, The Positive and Negative Affectivity;Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen35 PHQ-9, The Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PCL-M, PTSD Checklist, Military Version; PLC-C, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist, Civilian Version; PMIEs, potentially morally injurious experiences; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SAS-SR, The Social Adjustment Scale, Self-Report;Reference Gameroff, Wickramaratne and Weissman36 SBQ-R, Suicidal Behaviours Questionnaire;Reference Linehan and Clinics37 SSI, Scale for Suicide Ideation;Reference Beck, Kovacs and Weissman38 STAXI-2, State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory–2;Reference Spielberger39 Stressor checklist, checklist of morally significant stressor events identified via focus groups with veterinarians;Reference Crane, Phillips and Karin16 VESI, six items from the Vietnam Era Stress Inventory,Reference Wilson and Zigelbaum40 used to examine involvement in war-time atrocities (e.g. directly or indirectly involved in hurting, killing or mutilating the bodies of civilians and soldiers).

Data synthesis

The relationship between PMIEs and PTSD, depression and suicidal ideation was examined by meta-analytic methods. The relationship between PMIEs and anxiety and well-being (e.g. resilience, hostility, stress, positive affect and social adjustment) was examined descriptively, owing to insufficient data for meaningful statistical analysis (k < 4).

We conducted meta-analyses, using Rstudio (version 0.98.507) with the Metafor package.Reference Viechtbauer41 We used Pearson's product-moment correlation (r) as the effect size because r is more readily interpretable in comparison to other effect sizesReference Field42, Reference Rosenthal43 and is easily computed from t, F and d. We extracted effect size values for each association of interest within each study, with separate effect size values for each mental health disorder. Where necessary, correlation coefficients were calculated from other provided effect sizes (e.g. F) or obtained from study authors. Cohen'sReference Cohen44 guidelines were used to interpret the effect sizes (small effect r = 0.10, moderate effect r = 0.30 and large effect r = 0.50). Correlation coefficients were computed so that a positive coefficient reflected more severe mental health disorder symptoms, and a negative coefficient reflected less severe mental health disorder symptoms.

Where data regarding the relationship between particular PMIEs (e.g. transgressions – self, transgressions – others, betrayal) and mental health disorder symptoms was reported, one effect size was generated for each study by averaging across all of the PMIEs and mental health comparisons for the study.Reference Bryan, Bryan, Morrow, Etienne and Ray-Sannerud4, Reference Bryan, Bryan, Anestis, Anestis, Green and Etienne5 Study effect sizes by event type can be found in Supplementary Table 3. If studies recruited two samples but administered a more complete battery of mental health assessments to one particular sample, the data from this sample was used in the analyses (e.g. Bryan et al.Reference Bryan, Bryan, Anestis, Anestis, Green and Etienne5).

We applied the Hedges–Olkin approach,Reference Hedges and Vevea45 using the Fisher transformed correlation coefficients with the results reported in Pearson's r following a back conversion. We chose random-effects modelling with restricted maximum likelihood a priori, as this method allows the meta-analytic results to be generalised to a wider population of studies.Reference Hedges and Vevea45, Reference Huedo-Medina, Sánchez-Meca, Marín-Martínez and Botella46 To assess heterogeneity, or the presence of variation in the true effect sizes between studies, Cochran's Q and I 2 statistic were used. Heterogeneity can be clinical (e.g. differences between patients), methodological (e.g. differences in study design) or statistical (e.g. variation between studies in the underlying effects being evaluated).Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein47 To assess statistical heterogeneity, we examined the potential presence of moderator variables, with possible clinical and methodological heterogeneity examined descriptively. Heterogeneity was assessed to aid interpretation of the meta-analytic findings, as without knowing how consistent the results of studies are, it is not possible to determine the generalisability of the results.Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein47

We conducted moderator analyses on the PMIEs and PTSD, depression and suicide ideation analyses, including variables where there were at least three studies in each subcategory.Reference Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn and Juffer48 We individually examined the following variables as potential moderators of the association between PMIEs and mental health: participant age, whether the transgressive act was experienced in a military or non-military context, participant gender, study location (USA versus other) and whether or not the study utilised a measurement tool that solely examined exposure to PMIEs or if a tool was used which conflated PMIE exposure with the impact of effects (discussed in the following section). These moderators were chosen for the present analysis as sufficient data (k ≥ 3) was available to examine their impact on the effects. Meta-regression was used when a moderator was a continuous variable (e.g. participant age) to quantify the relationship between the magnitude of the moderator and the PMIEs (the mental health disorder effect).Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein47

Publication bias of the relationship between PMIEs and each mental health disorder analyses was examined by creating funnel plots to provide a visual representation of the data. Rank correlation testsReference Begg and Mazumdar49 and regression testsReference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder50 were conducted to determine if there was any evidence of publication bias. Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill procedure was also used to examine the presence of potential publication bias.Reference Duval and Tweedie51

Study sample

Twelve of the 13 studies identified were cross-sectional, with one notable exception.Reference Nash, Marino Carper, Mills, Au, Goldsmith and Litz7 Studies were published between 2011 and 2017 and involved a total of 6373 participants (range of 60–2095). Most participants were male, with an age range of 22.0–64.0 years. The majority of studies examined PMIEs in military samples in relation to military deployment (e.g. feeling troubled by having witnessed others' immoral acts while on deployment,Reference Nash, Marino Carper, Mills, Au, Goldsmith and Litz7 see Table 1). In non-military samples, exposure to moral and/or ethical dilemmas in the workplace were investigated. Studies in non-military samples examined exposure to PMIEs in journalists who covered the 2011 Norway terror attack (e.g. work description included tasks that went against personal values),Reference Backholm and Idås8 teachers exposed to community violence in El Salvador (e.g. witnessing actions by other school staff that led to the suffering of students),Reference Currier, Holland, Rojas-Flores, Herrera and Foy17 veterinarians who experienced morally significant events during veterinary practice (e.g. performed euthanasia for reasons they do not agree withReference Crane, Phillips and Karin16) and police officers who killed or caused serious injury in the line of duty.Reference Komarovskaya, Maguen, McCaslin, Metzler, Madan and Brown9 Non-validated assessments of workplace PMIEs were used by six studies (see Table 1), with many informed either by theory or previous research of moral injury,Reference Currier, Holland, Rojas-Flores, Herrera and Foy17, Reference Wilk, Bliese, Thomas, Wood, McGurk and Castro22 interviews with participantsReference Ferrajão and Oliveira19 or via focus groups.Reference Backholm and Idås8, Reference Crane, Phillips and Karin16, Reference Ritov and Barnetz20 Three included studies utilised validated measures of occupation-related trauma exposure as a proxy measure for PMIEs exposure.Reference Komarovskaya, Maguen, McCaslin, Metzler, Madan and Brown9, Reference Tripp, McDevitt-Murphy and Henschel21, Reference Dennis, Dennis, Van Voorhees, Calhoun, Dennis and Beckham18 Four studiesReference Bryan, Bryan, Morrow, Etienne and Ray-Sannerud4, Reference Bryan, Bryan, Anestis, Anestis, Green and Etienne5, Reference Nash, Marino Carper, Mills, Au, Goldsmith and Litz7, Reference Currier, Holland, Drescher and Foy14 used the Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES)Reference Nash, Marino Carper, Mills, Au, Goldsmith and Litz7 or the Moral Injury Questionnaire-Military Version,Reference Currier, Holland, Drescher and Foy14 which assess exposure to both PMIEs (e.g. ‘I saw things that were morally wrong’) as well as emotional outcomes (e.g. ‘I am troubled by having witnessed others' immoral acts’) on the same items. This may confound exposure to PMIEs with the effects of exposure and could affect the reported effect sizes.Reference Farnsworth, Drescher, Nieuwsma, Walser and Currier2 Time since PMIEs was often unreported, with a few studies either stating that the participants were still in active military/police service or with the PMIE related to service in the Vietnam War.Reference Dennis, Dennis, Van Voorhees, Calhoun, Dennis and Beckham18

Results

PTSD

Twelve studies assessed the relationship between PMIEs and PTSD with a variety of measures, of which ten reported significant findings (see Table 1). Most studies assessed PTSD symptoms with the Post-traumatic Stress Disorder ChecklistReference Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska and Keane52; however, no marked differences in the PMIEs–PTSD association by PTSD measurement tool were observed. For the PMIEs and PTSD association, the weighted mean effect size was 0.30 (P < 0.0001, 95% CI 0.20–0.39). This effect size is statistically significant and meets criteria for a moderate effect, suggesting that PMIEs account for approximately 9.4% of the variance in PTSD. The effect sizes of PMIEs and PTSD ranged between 0.02 and 0.65, with some of the largest effects found in military samples (see Table 2). A potential outlier was Ferrajão and Oliveira,Reference Ferrajão and Oliveira19 although a small positive relationship between PMIEs and PTSD was found, no significant differences in PTSD symptoms were found between those who did and those who did not report exposure to PMIEs. A non-significant positive association between PMIEs and PTSD was also observed by Bryan et al.,Reference Bryan, Bryan, Morrow, Etienne and Ray-Sannerud4 however this effect was small (effect size of 0.02).

Table 2 Relationship between mental health and PMIEs

PMIEs, potentially morally injurious experiences; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

* P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Heterogeneity analysis was significant (Q(11) = 90.4; P < 0.0001; I 2 = 92.01%), and potential moderating variables were examined to determine whether study characteristics accounted for differences in the results.Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein47 Between-group differences in effect size related to study-level moderators were examined by the between-group Q statistic within a random effects model. Results revealed no significant moderator effect on the association between PMIEs and PTSD of participant age (between-group Q(1) = 0.14; P = 0.71), percentage of male participants in the study (Q(1) = 0.23; P = 0.62), whether the PMIE was military versus non-military related (Q(1) = 0.003; P = 0.95), whether the measurement of PMIEs conflated event exposure with the emotional effects of exposure (Q(1) = 0.08; P = 0.78) or study location (USA versus other, Q(1) = 0.06; P = 0.80).

No evidence for publication bias was found for the PMIEs and PTSD analysis. Visual inspection, rank correlation (P = 0.84) and Egger's tests (P = 0.72) indicated non-asymmetric funnel plots. Furthermore, the trim and fill procedure did not suggest the imputation of any studies for this analysis, indicating a lack of publication bias.

Depression

Seven studies assessed the relationship between PMIEs and depression, four of which reported significant findings. Studies largely used the Beck Depression Inventory, Second EditionReference Beck, Steer and Brown53 or The Patient Health Questionnaire-9Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams54 to assess depression. Pearson's r effect sizes for the association between PMIEs and depression ranged between −0.05 and 0.40. No marked differences in the PMIEs–depression association were observed based on the depression measure used, although Ferrajão and OliveiraReference Ferrajão and Oliveira19 was the only study to examine depression with the depression subscale of the Brief Symptom InventoryReference Derogatis55 and found a particularly small association between PMIE and depression (effect size of 0.03). All studies examining the relationship between PMIEs and depression were conducted with military samples, with the majority conducted in the USA (k = 6). The mean effect size of the PMIEs and depression association was 0.23, meeting criteria for a small effect, and was statistically significant (P = 0.0002; 95% CI 0.11–0.37). This indicates that PMIEs accounted for 5.2% of the variance in depression. Notably, Bryan et al. Reference Bryan, Bryan, Morrow, Etienne and Ray-Sannerud4 found a negative association between PMIEs and depression (overall effect size of −0.05), meaning that PMIE was associated with fewer depression symptoms, although the strength and nature of the PMIEs–depression relationship varied by event type (see Supplementary Table 3).

The results of the heterogeneity analysis were significant (Q(6) = 39.56; P < 0.0001; I 2 = 88.93). No significant study moderators were found (participant age, Q(1) = 1.39, P = 0.23; percentage of male participants, Q(1) = 1.88, P = 0.17; whether the measurement of PMIE conflated event exposure with the emotional effect of exposure, Q(1) = 0.23; P = 0.63).

No evidence of publication bias was found. The rank correlation (P = 0.77) and Egger's (P = 0.18) tests were not significant and the trim and fill procedure did not recommend the imputation of any additional studies for this analysis, indicative of a lack of publication bias.

Suicidality

Four studies assessed the PMIEs–suicidality association, three of which reported significant findings. All studies were based in the USA and examined PMIEs in a military context. Meta-analysis examining PMIEs and suicidality identified a small, significant mean effect size of 0.14 (P < 0.0001; 95% CI 0.08–0.20). This mean effect size meets the criteria for a small effect, suggesting that PMIEs is associated with approximately 2.0% of the variance in suicidality. Studies reporting on the relationship between PMIEs and suicidality all utilised military samples, with effect sizes ranging from 0.13 to 0.27.

The results of the heterogeneity analysis were non-significant (Q(3) = 1.27; P = 0.74; I 2 = 0.00). Given the small number of included studies, a non-significant result cannot necessarily be interpreted as evidence of no statistical heterogeneity as the test may lack power to detect significant heterogeneity when present.Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein47 Thus, between-group differences in effect size related to study-level moderators were examined by a random effects model to ensure the PMIEs–suicidality association was thoroughly explored. No significant moderators of effect size were found (age, Q(1) = 0.18; P = 0.67; percentage of male participants, Q(1) = 0.01; P = 0.94). Other moderators, such as study location, whether the tool used to measure PMIE conflated PMIE exposure with the emotional effects of exposure, and PMIE type (e.g. military versus non-military) could not be examined owing to insufficient data for a meaningful contrast between subgroups. Only one study used a non-validated measure of PMIEs,Reference Currier, Holland, Drescher and Foy14 and it reported findings (effect size of 0.14) that were not inconsistent with other studies that utilised validated measures of PMIE (e.g. Bryan et al. Reference Bryan, Bryan, Morrow, Etienne and Ray-Sannerud4 and Dennis et al. Reference Dennis, Dennis, Van Voorhees, Calhoun, Dennis and Beckham18). No evidence for publication bias was found for the PMIEs and suicidality analysis. Visual inspection, rank correlation (P = 0.33) and Egger's tests (P = 0.38) suggest non-asymmetric funnel plots. The trim and fill procedure did not recommend the addition of any further studies for this analysis, suggesting a lack of publication bias.

Anxiety

Three studies examined the association between PMIEs and anxiety, thus it was not possible to utilise meta-analytic methods.Reference Bryan, Bryan, Anestis, Anestis, Green and Etienne5, Reference Nash, Marino Carper, Mills, Au, Goldsmith and Litz7, Reference Crane, Phillips and Karin16 One study examined the relationship between PMIEs and anxiety in veterinarians,Reference Crane, Phillips and Karin16 whereas Bryan et al. Reference Bryan, Bryan, Anestis, Anestis, Green and Etienne5 and Nash et al. Reference Nash, Marino Carper, Mills, Au, Goldsmith and Litz7 examined military-related exposure to PMIEs. PMIEs were significantly associated with anxiety symptoms across all three studies (range of 0.16–0.28, see Table 2). The relationship between PMIEs and anxiety was fairly small in the non-military sample,Reference Crane, Phillips and Karin16 which may reflect the nature and/or intensity of the PMIEs experienced. Bryan et al. Reference Bryan, Bryan, Anestis, Anestis, Green and Etienne5 found all event types (e.g. transgressions – other, transgressions – self, betrayal) to be significantly positively associated with anxiety, with the strongest relationship found between anxiety and perceived betrayal (effect size of 0.219; see Supplementary Table 3).

Hostility

Three studies examined the relationship between hostility and PMIEs, all in a military context.Reference Bryan, Bryan, Anestis, Anestis, Green and Etienne5, Reference Dennis, Dennis, Van Voorhees, Calhoun, Dennis and Beckham18, Reference Wilk, Bliese, Thomas, Wood, McGurk and Castro22 In all studies, PMIEs and exposure to wartime atrocities (e.g. acting in ways that violate one's moral code; hurting, killing or mutilating bodies of civilians and enemy combatants) was positively and significantly associated with hostile behaviour, although some effects were small (Bryan et al. Reference Bryan, Bryan, Anestis, Anestis, Green and Etienne5 effect size of 0.21; Dennis et al. Reference Dennis, Dennis, Van Voorhees, Calhoun, Dennis and Beckham18 effect size of 0.18).Reference Cohen44 The larger effect reported by Wilk and colleaguesReference Wilk, Bliese, Thomas, Wood, McGurk and Castro22 (effect size of 0.41) may reflect the fact that the sample participated in the study during deployment to Iraq in 2007, a non-validated measure of PMIEs was used and the non-validated measure of hostility largely focused on aggression towards other unit members (e.g. ‘In the past month, have you threatened a unit member with physical violence?’).

Resilience, social adjustment and positive affect

The relationship between PMIEs and psychological resilience, or the ability to recover from stressor events in the past 4 weeks, was examined by Crane et al. Reference Crane, Phillips and Karin16 with the Brief Resilience Scale,Reference Smith, Dalen, Wiggins, Tooley, Christopher and Bernard56 with a significant negative association found between PMIEs and resilience (effect size of −0.17; Table 3). Consistent with this, Crane et al. Reference Crane, Phillips and Karin16 also found a positive association between PMIEs and self-reported symptoms of stress (effect size of 0.24).

Table 3 Well-being and PMIEs

PMIEs, potentially morally injurious experiences; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

* P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Nash et al. Reference Nash, Marino Carper, Mills, Au, Goldsmith and Litz7 examined the relationship between military related PMIEs and positive affect and social adjustment. PMIEs were significantly negatively associated with positive affect (effect size of −0.15) and social adjustment (effect size of −0.29), indicating that higher levels of PMIEs were associated with less self-reported social support and less positive affect.Reference Nash, Marino Carper, Mills, Au, Goldsmith and Litz7 In keeping with these findings, Ferrajão and OliveiraReference Ferrajão and Oliveira19 also found a small, but not statistically significant negative relationship between perceived social support and PMIEs (effect size of −0.03). However, these findings should be interpreted cautiously as Nash et al. Reference Nash, Marino Carper, Mills, Au, Goldsmith and Litz7 used the MIES, which confounds PMIE exposure with outomes,Reference Frankfurt and Frazier3 whereas Ferrajão and OliveiraReference Ferrajão and Oliveira19 used a non-validated PMIE measure.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to examine the relationship between exposure to PMIEs incurred as a result of occupation and mental health outcomes. Although based on a relatively small number of articles, the results indicate that a small-to-moderate relationship between PMIEs and PTSD and depression is evident, although the associations with other mental health symptomology appears less certain.

The strongest relationship was found between PMIEs and PTSD, consistent with previous studies that report that the common symptoms of moral injury are intrusive thoughts, intense negative appraisals (e.g. shame, guilt, disgust, etc.) and reliance on cognitive avoidance as a (maladaptive) coping strategy.Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash and Silva1 The experience of such PTSD symptoms has also been found cross-culturally in qualitative studies of moral injury in war veterans in Zimbabwe,Reference Moyo57 where pastoral care was experienced as particularly efficacious in managing intrusive thoughts and negative affect. Although study location (USA versus Other) was not found to be a significant moderator in this analysis, included studies were largely conducted in Western environments. Additional investigation of the experiences and impact of occupation-related PMIEs in non-Western contexts would be useful to further the understanding of cross-cultural differences and similarities in mental health outcomes following PMIEs and how best to support morally injured individuals.

A statistically significant, although small relationship between depression and PMIEs was found in military personnel; however, civilian data on this association was lacking. Characteristic symptoms of depression include social withdrawal, self-depreciating emotions and a loss of meaning,58 all of which have been reported in qualitative studies following military-related moral injury.Reference Drescher, Foy, Kelly, Leshner, Schutz and Litz6 Similar symptoms of depression and psychological distress have also been reported in qualitative studies of humanitarian aid workers who experience work-related moral challenges (e.g. a lack of resources meaning they cannot provide adequate healthcare to all patientsReference Hunt59, Reference Schwartz, Sinding, Hunt, Elit, Redwood-Campbell and Adelson60).

Suicidality was significantly associated with PMIEs in military personnel with a small effect. However, this relationship may be less reliable as only three studies report significant findings. Alternatively, it is possible that the relationship between suicidality PMIEs may be an indirect effect caused by other associated risk factors or consequences of PMIEs, such as depression or PTSD,Reference Bryan, Bryan, Morrow, Etienne and Ray-Sannerud4, Reference Griffith61, Reference LeardMann, Powell, Smith, Bell, Smith and Boyko62 and warrants further research.

A modest relationship between PMIEs, anxiety, hostility, poor resilience and less social support was also examined in this review. The relationship between PMIEs and hostility is in keeping with recent research of military-related PMIEs causing anger or hostility that persists for several years post-deployment, even after controlling for PTSD symptoms.Reference Worthen and Ahern63 Nonetheless, additional investigation is required to explore the PMIEs–hostility relationship in non-military contexts.

Taken together, the results suggest a negative impact of PMIEs on psychological adjustment, in both a military and non-military occupational context. However, PMIEs only accounted for a modest proportion of the variance in PTSD, depression and suicidality. It may be valuable for future studies to consider other risk factors and instrumental moderator variables for such psychological adjustment difficulties. Given the lack of a widespread, substantial impact on mental health, it also may be of interest to consider whether exposure to PMIEs might be linked to other outcomes both in terms of practical (e.g. resigning from one's work) or positive change (e.g. post-traumatic growth).

Strengths and limitations

The results of this study must be considered in light of the limitations. First, most included studies examined PMIEs in a military context (k = 10). Other occupational groups, including firefighters, relief aid workers and social workers, are exposed to traumatic and PMIEs and additional research is needed to fully understand the impact of such stressors on their mental health and well-being. Second, all studies measured exposure to PMIEs by self-report measures, many of which were not validated.Reference Backholm and Idås8, Reference Crane, Phillips and Karin16, Reference Currier, Holland, Rojas-Flores, Herrera and Foy17, Reference Ferrajão and Oliveira19, Reference Ritov and Barnetz20 Several studies also used measures of PMIEs that have methodological issuesReference Farnsworth, Drescher, Nieuwsma, Walser and Currier2 (e.g. confounding exposure to transgressive events with exposure effectsReference Bryan, Bryan, Morrow, Etienne and Ray-Sannerud4, Reference Bryan, Bryan, Anestis, Anestis, Green and Etienne5, Reference Nash, Marino Carper, Mills, Au, Goldsmith and Litz7, Reference Currier, Holland, Drescher and Foy14), although this was not found to be a significant moderator for the PTSD and depression analyses. In some cases, a proxy measure of PMIEs, such as exposure to war-time atrocities,Reference Dennis, Dennis, Van Voorhees, Calhoun, Dennis and Beckham18 was used which highlights the lack of consistency in the literature of the types of events that can cause moral injury. Nonetheless, to further our understanding of the impact of PMIEs on mental health, a valid and reliable assessment of PMIEs and moral injury outcomes is required. Third, this review was not pre-registered on PROSPERO or a similar register. Finally, the majority of studies included in this review examined PMIEs in a US or Western context (e.g. Norway, Australia), with a few notable exceptions (e.g. Israel, El Salvador) and additional research in non-Western, low- or middle-income countries is needed.

Clinical implications

Our findings indicate that occupational PMIEs can potentially have an, albeit small, impact on the mental health of both military and civilian personnel. Importantly, this suggests that moral injury is not a concept that is only relevant within a military context and can potentially be experienced in other occupational settings, although additional research in non-military samples is recommended to more fully understand this experience. What evidence there is suggests that individuals who experience PMIE may be at risk of PTSD and depressive disorders. Previous reviews suggest that some treatment approaches for these disorders may be insufficient in cases of moral injury.Reference Drescher, Foy, Kelly, Leshner, Schutz and Litz6 Treatment for PTSD, for example, may not adequately address all negative sequelae present in those with moral injury. Future research exploring the impact of PMIEs on psychopathology over time, as well as randomised control trials directly evaluating treatment approaches following PMIEs would be beneficial.

Directions for future research

This review suggests a number of additional areas for exploration that may prove beneficial for our understanding of moral injury. Although the evidence regarding the mental health outcomes of PMIEs appears to be at most modest, what seems particularly clear is that there is a lack of high-quality evidence published on this topic. This, in part, may reflect the fact that moral injury is a relatively emerging conceptReference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash and Silva1, Reference Farnsworth, Drescher, Nieuwsma, Walser and Currier2 and there is a need for considerably more research, including the design and validation of assessments that measure the impact of PMIE exposure as well as the outcomes of moral injury. As it stands, some existing measures do not include exposure to a variety of PMIEs or confound PMIE exposure with the psychological effects of exposure.Reference Farnsworth, Drescher, Nieuwsma, Walser and Currier2, Reference Frankfurt and Frazier3 The development of high-quality measurement tools would allow for reliable investigations into the existence and prevalence of moral injury in both military and non-military environments and would further our theoretical understanding of whether moral injury is a distinct concept. This line of research could also aid in exploring whether there are particular experiences that are more likely to cause moral injury, as well as the precursors and the factors associated with vulnerability or resilience following moral injury. As not all individuals who experience trauma necessarily develop PTSD, exposure to PMIEs may similarly not always result in moral injury and additional research is needed to better understand PMIE outcomes. For example, the pernicious effects of moral injury may depend on one's appraisal of the transgressive act and the coping strategies used.

In the wider literature, previous studies in healthcare professionals have found years of occupation experience to be significantly positively associated with moral distress, contributing to staff burnout and resignation.Reference Lamiani, Borghi and Argentero10, Reference Oh and Gastmans11 Although moral distress differs from moral injury in that the conditions in which it can be experienced are often more limited (e.g. healthcare professionals are prevented from acting on their judgement of the right thing to do largely by institutional restraints, such as pressure to minimise costsReference Epstein and Delgado64); nonetheless, it is possible that factors contributing to poor mental health outcomes following moral distress may be applicable in cases of moral injury and should be pursued further.

Although only examined by two studies, exposure to specific PMIEs (e.g. transgressions – other, transgressions – self, betrayal) were differentially associated with mental healthReference Bryan, Bryan, Morrow, Etienne and Ray-Sannerud4, Reference Bryan, Bryan, Anestis, Anestis, Green and Etienne5 (Supplementary Table 3). One studyReference Bryan, Bryan, Anestis, Anestis, Green and Etienne5 found a particularly strong relationship between perceived betrayal and mental health difficulties. As this sample had very recently returned from deployment to Afghanistan, this type of PMIE could be more salient to participants when responding to study measures. This highlights the need for moral injury to be examined as a function of PMIE type and time since event to better understand moral injury.

Summary

This review presents a comprehensive review and meta-analysis of the relationship between exposure to occupational-related PMIEs and mental health in both military and non-military connected personnel. We found small yet significant associations between PMIEs and PTSD and depression. A less reliable relationship between PMIEs, anxiety, hostility and suicidality was also observed. Given the limited number of high-quality studies available, only tentative conclusions about the association between PMIEs and mental health disorders can be made at this stage. This study highlights that considerably more research is needed in the field of moral injury, including the development of valid assessments of the impact of PMIEs exposure and outcomes. We suggest that additional investigations, particularly in relevant non-military connected populations, and other influential moderators and outcomes are considered in future research into moral injury.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.55.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.