It is likely that the Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA) will be subject to a major review by Parliament in the near future. We recently completed a systematic review for the Department of Health (Reference Wall, Buchanan and FahyWall et al, 1999a ) and now wish to bring some of the main findings to a professional audience.

Part of the review was concerned with changes in the use of the Act since its introduction, discovered using routine statistics. So far these statistics have not been widely disseminated. We have reported previously an overall increase in the use of the Act to admit patients to psychiatric hospitals (Reference Wall, Hotopf and WesselyWall et al, 1999b ). This paper explores changes in the use of the Act in more detail.

METHOD

All formal admissions received by any hospital in England are routinely notified to the Department of Health (Department of Health, 1998). These data allow an analysis of the use of the MHA to be made in terms of the following variables:

-

(a) the section of the Act used (see Table 1);

-

(b) whether the Act was used to admit a patient or was applied to a patient already in hospital;

-

(c) whether it was a new admission or an admission under one section being converted into an admission under another (e.g. an admission under section 5(2) being converted into an admission under section 2);

-

(d) where the admission under the Act was applied; and

-

(e) the year in which the admission under the Act was applied.

Table 1 Sections of the Mental Health Act 1983

| Section | Duration of admission allowed |

|---|---|

| Part II: General sections | |

| Section 2: Admission for assessment | 28 days |

| Section 3: Admission for treatment | 6 months |

| Section 4: Emergency admission for assessment | 72 hours |

| Section 5(2): Doctor's holding power | 72 hours |

| Section 5(4): Nurse's holding power | 6 hours |

| Part III: Forensic sections | |

| Section 35: Remand to hospital for report on mental condition | — |

| Section 36: Remand to hospital for treatment | 28 days |

| Section 37: Hospital order | 6 months |

| Section 38: Interim hospital order | 12 weeks |

| Section 47: Transfer to hospital of prisoners | — |

| Section 48: Removal to hospital of other prisoners (unsentenced prisoners) | — |

| Section 135: Warrant to search for and remove patients | — |

| Section 136: Mentally disordered persons found in public places | — |

We limited our analyses to data for England; Scotland and Northern Ireland have different laws, and data were only available in Wales from 1991 to 1997. The Department of Health data did not separate admissions under sections 47 and 48, so these data were obtained from the Home Office.

In order to determine the proportion of detained patients admitted to hospital, denominator data for psychiatric hospital admissions were obtained from the Department of Health's mental health division. From 1984 to 1986 data were available via the Mental Health Enquiry (1990), a national survey of all psychiatric hospital admissions. Data from 1989-96 were obtained from the Hospital Episodes Statistics system. For three years (1986-89) information was not available; this was a period of transition between the two types of data collection and the data obtained at this time were thought to be of poor quality. In order to gain denominator data for admissions under the forensic sections of the Act, which are used to transfer prisoners from prison to hospitals, we used Home Office statistics on the average prison populations for each year.

Data are presented as the total number of admissions under each section of the Act in each year, and the proportion of admissions which were under the MHA.

RESULTS

All admissions

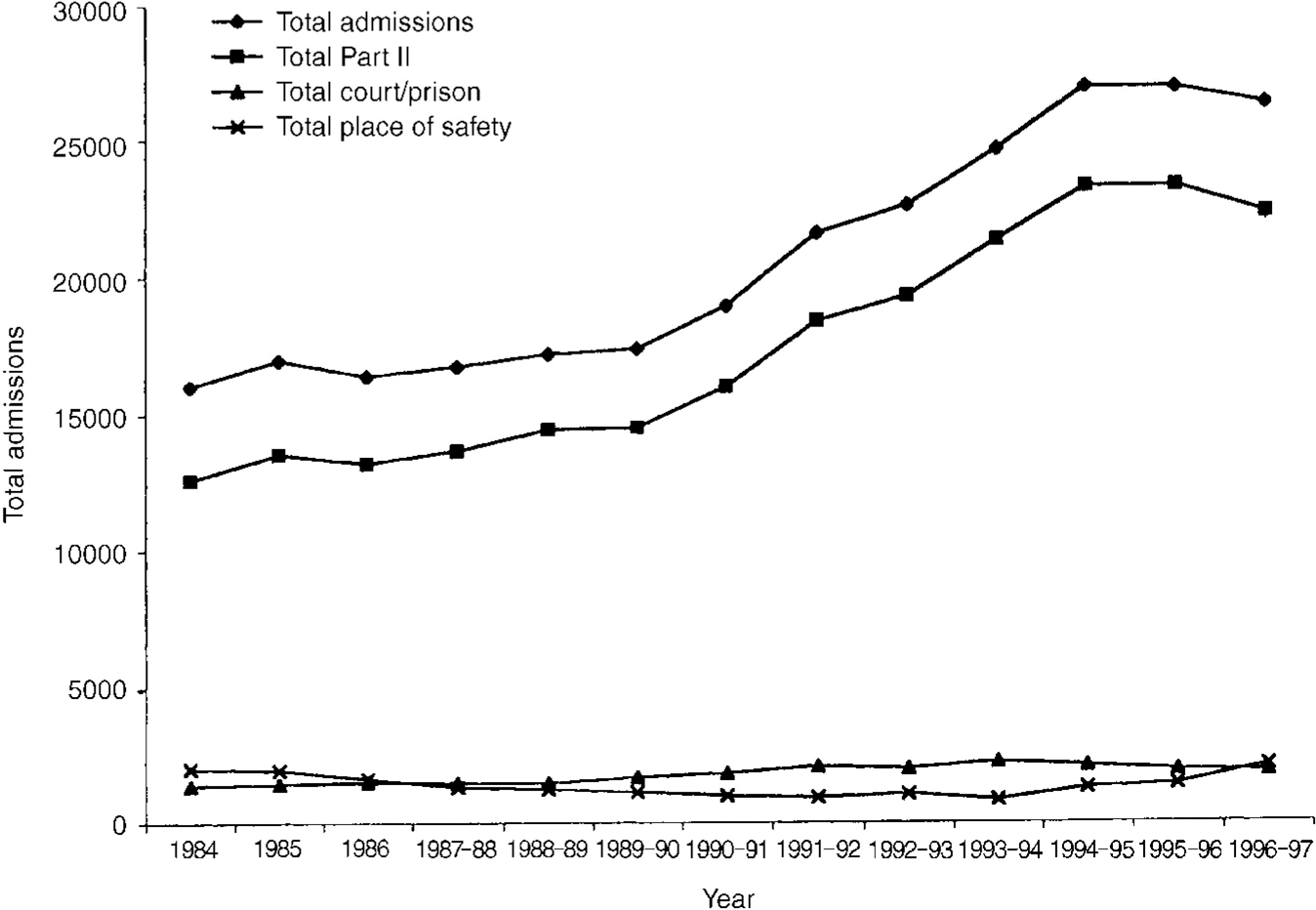

Figure 1 gives an overview of all formal admissions to National Health Service (NHS) facilities, private mental nursing homes and special hospitals. The total number of formal admissions increased gradually between 1984 and 1991 by an average of 500 new admissions per year. From 1992 to 1996, the admission rate accelerated to 1500 new admissions per year. Part II admissions form the largest proportion of all formal admissions, and appear to have had the strongest influence on the overall trend. Court and prison admissions (Part III of the Act) also showed an overall increase over the period. The use of the miscellaneous powers under Part X of the Act (sections 135 and 136) declined gradually from 2000 per year in 1984 to 1000 in 1990/91, rising again to 2000 in 1995/96. During the same period there was an increase in the number of psychiatric hospital admissions each year, from 190 389 in 1984 to 213 240 in 1996.

Fig. 1 Admissions under the Mental Health Act 1983.

Use of Part II of the Act

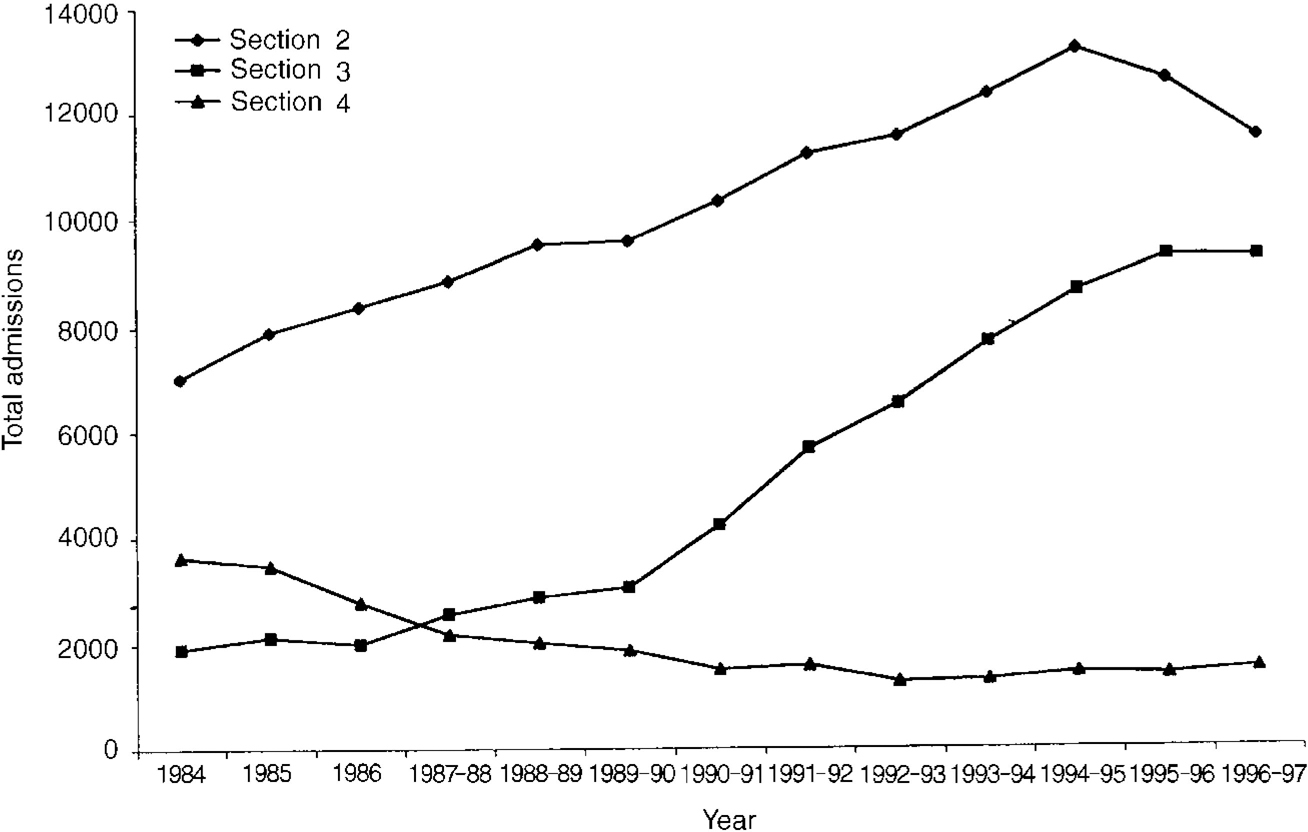

Figure 2 shows the changes in absolute numbers of people admitted under different sections of Part II of the Act. The main findings are that the absolute numbers of patients admitted under sections 2 and 3 have increased, while numbers admitted under section 4 have fallen. As a proportion of all admissions, section 2 admissions rose from 3.7% to 5.4% between 1984 and 1996, and section 3 admissions rose from 1.0% to 4.3% over the same period. Meanwhile, admissions under section 4 fell from 1.9% to 0.7% of all psychiatric hospital admissions.

Fig. 2 Changes in the use of Part II sections of the Mental Health Act 1983.

Use of Part III of the Act

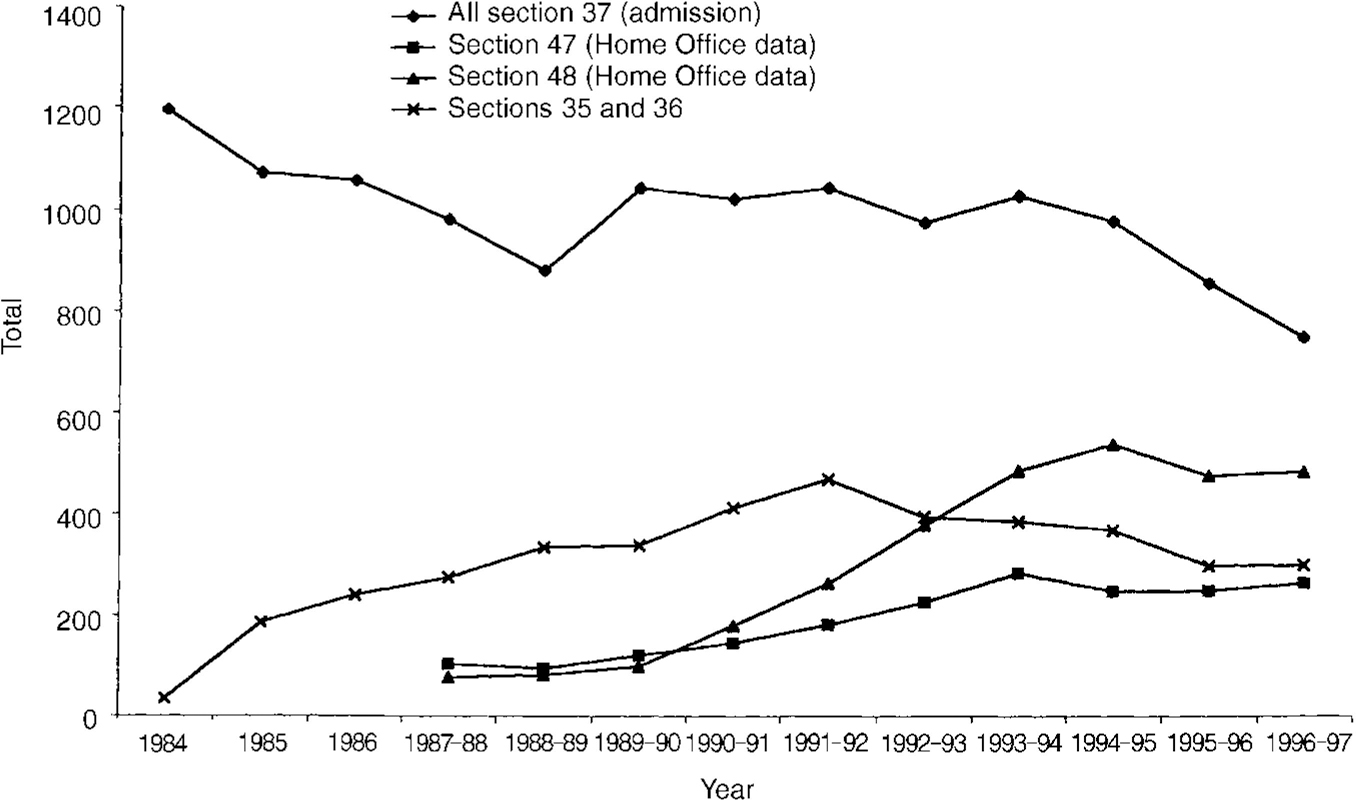

There was an overall increase in the use of Part III of the MHA, which covers forensic admissions. Court and prison admissions account for less than 10% of all formal admissions. Between 1989 and 1992 admissions rose from under 1500 per year to over 2000. Figure 3 shows the use of individual sections in Part III. There are a number of striking changes over this period. Use of section 47 (transfer of sentenced prisoners to hospital) more than doubled from 103 instances in 1987 to 264 in 1996. Use of section 48 (transfer of untried or unsentenced prisoners to hospital) rose from 77 per year to 481 over the same period - a more than six-fold increase. Use of section 37 (hospital orders) decreased from 1194 instances in 1984 to 749 in 1996.

Fig. 3 Changes in use of the forensic sections of the Mental Health Act 1983.

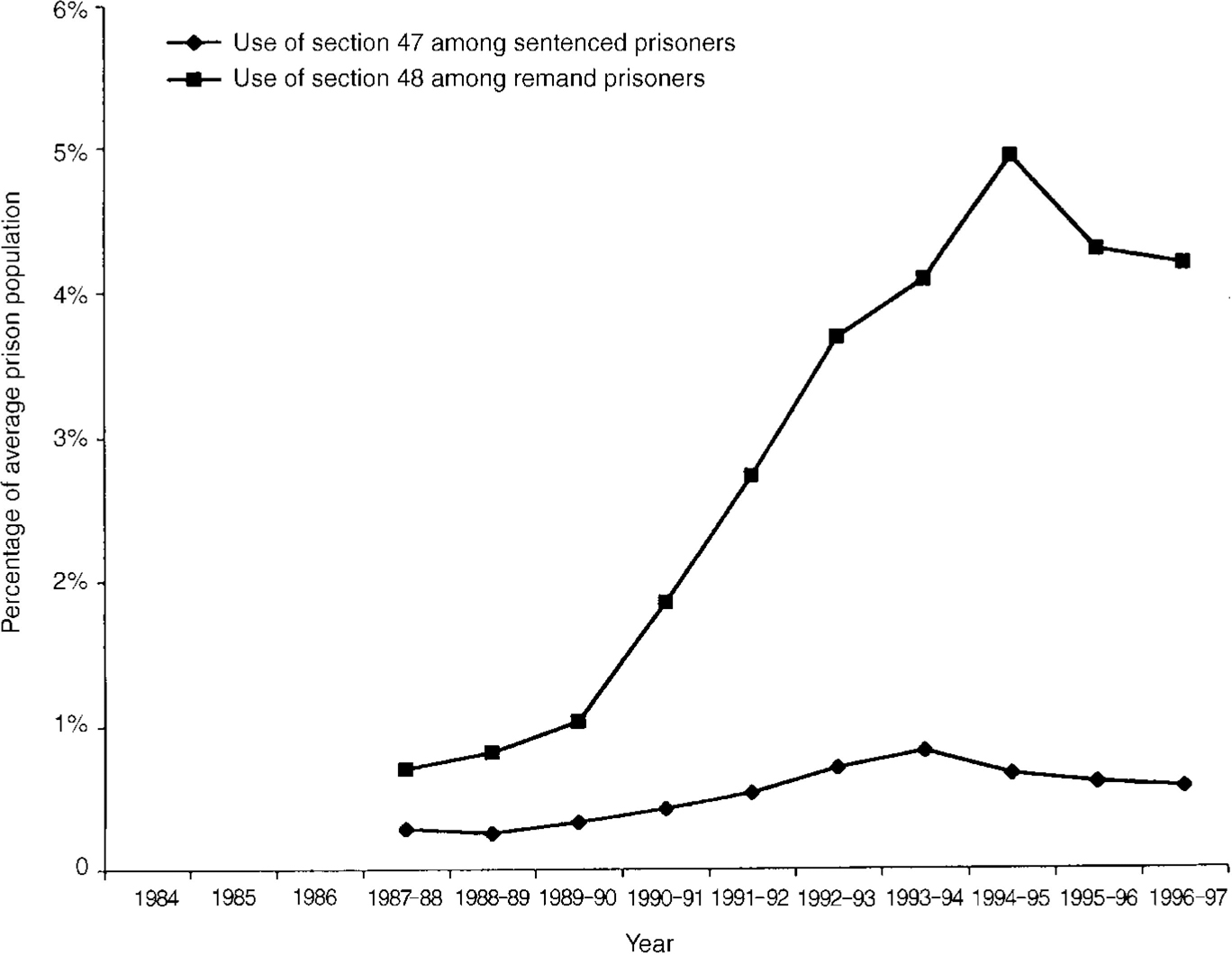

Using Home Office data we used the average annual population of sentenced prisoners as the denominator for uses of section 47, and the average annual population of unsentenced prisoners as the denominator for uses of section 48. The results are shown in Fig. 4. Despite an increase in the prison population during this period, the proportion of prisoners transferred under each section rose, with a particularly marked increase in the use of section 48.

Fig. 4 Changes in proportions of prison population subject to sections 47 and 48 of the Mental Health Act 1983.

Changes from informal to formal status

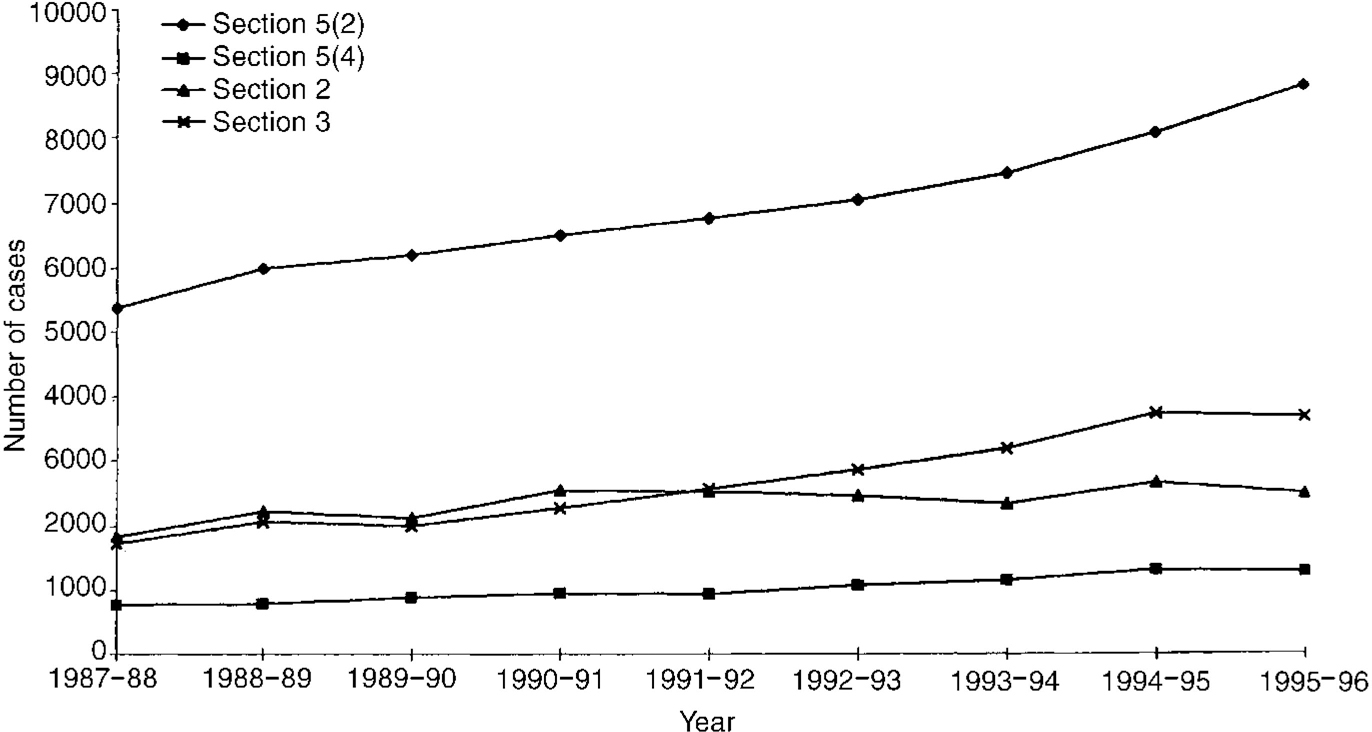

Figure 5 shows trends in the use of the Act for informal in-patients. The most widely used section for informal patients in section 5(2) (doctor's holding power), the use of which nearly doubled from over 5000 per year in 1987 to just under 9000 in 1996. By contrast, section 5(4) (nurse's holding power) has always been used infrequently, and there was little change in its use over the period of the study.

Fig. 5 Number of cases changed from informal admission to admission under Part II of the Mental Health Act 1983.

There was a change in the pattern of use of sections 2 and 3 for previously informal patients. These two sections were applied equally to informal patients until 1992, when section 3 increasingly became the preferred option. This change appears to mirror the rise in the use of section 3 to admit patients to hospital.

Changes from admission under section 5(2) to informal status or admission under other sections

Figure 6 demonstrates the changes experienced by those patients admitted under section 5(2) once the admission had lapsed or been altered. The majority of such admissions were allowed to lapse to informal status, but there was a sharp increase in the number of patients whose admission basis changed from section 5(2) to section 3.

Fig. 6 Total number of changes from admission under section 5(2) of the Mental Health Act 1983 to informal or Part II status.

Changes from admission under section 4 to informal status on admission under other sections

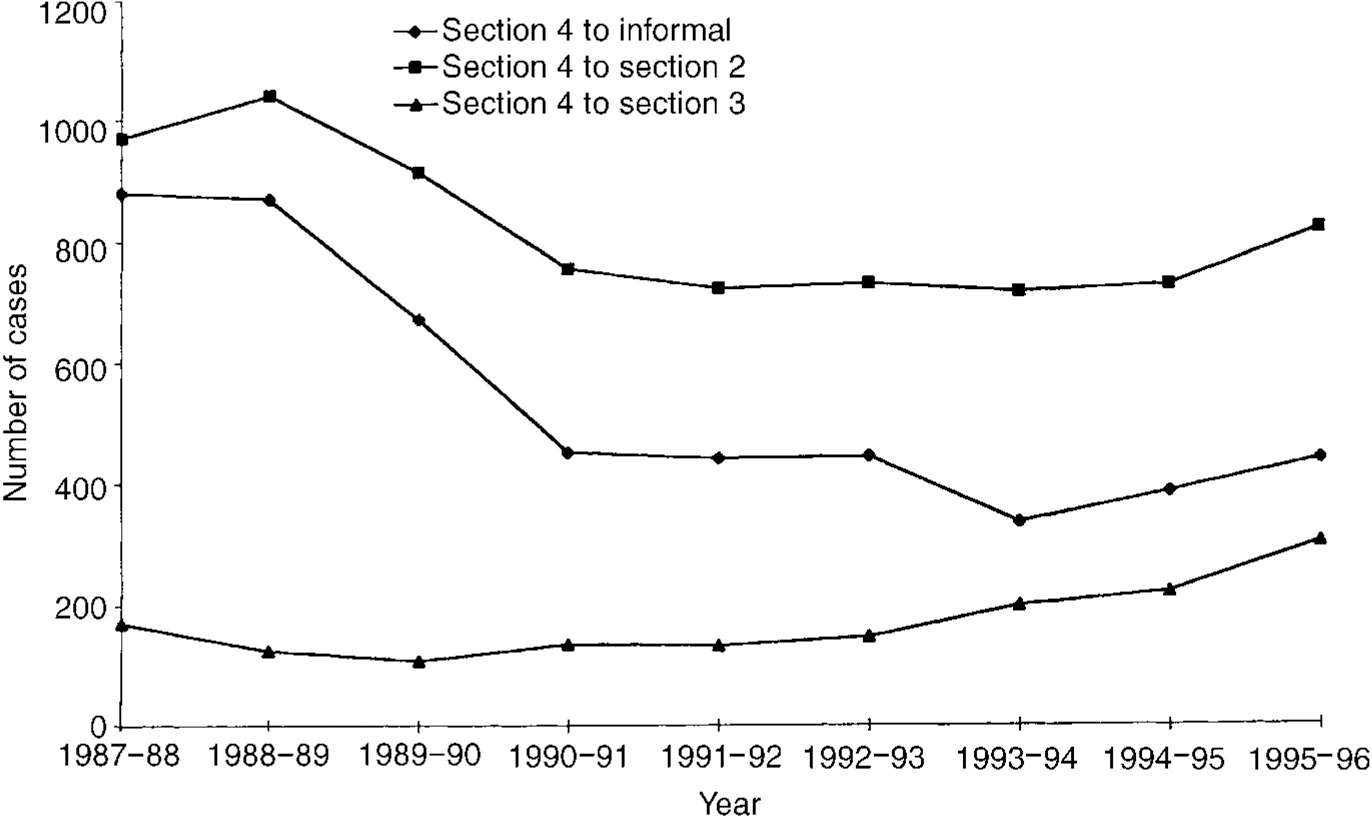

Figure 7 shows what happened to patients admitted under section 4. Over time, many more patients admitted under this section were transferred to a section 3 admission, while the proportion of section 4 patients whose admissions were allowed to lapse to informal status decreased.

Fig. 7 Total number of changes from admissions under section 4 of the Mental Health Act 1983.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

There are seven main findings of this study.

First, there was a dramatic rise in the absolute number of formal admissions, and in the proportion of all psychiatric admissions which are formal, over the study period.

Second, this increase was largely accounted for by an increase in the use of Part II of the Act. While the proportion of Part III admissions has increased, the rise in terms of absolute numbers is modest by comparison.

Third, within Part II there was a steady increase in admissions under section 2, a massive increase in the use of section 3, and both an absolute and a relative decrease in admissions under section 4.

Fourth, within Part III there was a fall in the use of section 37 and a rise in the use of section 47 and particularly section 48.

Fifth, for Part X, there was a drop in the total number of admissions under section 136 until 1990, followed by an increase.

Sixth, there was a steady rise in the use of section 5(2) over the study period. Most admissions under section 5(2) were rescinded or left to lapse, but there was an increase in conversions from section 5(2) to section 3.

Seventh, for section 4, there was a reduction in conversions to informal status, and an increase in conversions to section 3, over the study period.

Methodological weaknesses

These data are potentially unreliable (Reference Nemitz and BeanNemitz & Bean, 1995), as they depend on NHS trusts reporting the use of the Act when Department of Health admissions under the Act occur. It is therefore possible that changes in the efficiency with which admissions under the Act are reported could account for the increase in the number of formal admissions. Furthermore, the data refer to the total number of admissions under sections of the Act, not the total numbers of patients admitted. It is therefore possible that in the same year the same individual could have been admitted several times, and each admission would have been counted as a separate admission. However, there are a number of reasons why this explanation is unlikely to account for these results.

First, the total number of formal admissions rose year on year, while it seems likely that increases in the proportion of admissions under the Act being accurately reported would increase more suddenly as a result of a drive to improve data collection. Second, the period 1984-96 was one of great change in the organisation of health care. During this time NHS trusts were established, and many of them have since merged. It is likely that the disruption these changes involved would have reduced the proportion of admissions under the Act accurately reported during the middle years in which these data were collected. Finally, the changes in the use of individual sections of the Act have not all been upward. Sections 4 and 37 were used less over the study period, and reporting bias is unlikely to account for such decreases in the context of an overall increase in the use of the Act. We believe, therefore, that the fall in the use of sections 4 and 37 is the most reliable result of this study.

Interpretation

If our findings are not simply due to reporting artefacts, what should be made of them? It seems inherently unlikely that changes in population rates of mental illness could explain these findings (Reference Der, Gupta and MurrayDer et al, 1990; Reference Castle, Wessely and DerCastle et al, 1991). The prevalence of psychiatric disorder would have to have risen dramatically over the relatively short duration of this report; furthermore, we were able to use denominator data which suggested that the proportion of all admissions which were formal also increased.

The findings could be explained if the clinical picture of psychotic illness has changed. For example, there is a widely held, if inadequately explored, belief that patients with psychotic illnesses are more prone to use drugs of abuse now than they were 15 years ago (Reference CuffelCuffel, 1992). Substance misuse might act to worsen the clinical picture of psychotic illness and lead to associated disinhibition, increasing the likelihood that patients are admitted formally.

Most plausibly, the changes could be due to alterations in the delivery of psychiatric services, and changes in professional views regarding coercion and safety. The introduction of ‘care in the community’ has been accompanied by a massive fall in the number of psychiatric beds (Reference Davidge, Elias and JayesDavidge et al, 1994), which may have a number of consequences relevant to admissions under the MHA. It seems likely that psychiatrists now reserve admission for patients with the most severe illness, a high proportion of whom are likely to require formal admissions. With pressure on beds, admissions are also likely to be shorter. This means that the same patients may be readmitted later in the same year. At the same time, psychiatrists have been criticised for failing to detain patients who have subsequently committed crimes (Reference Ritchie, Dick and LinghamRitchie et al, 1994), and are becoming increasingly preoccupied with risk management (Reference HollowayHolloway, 1996). It is difficult to separate the competing influences of these factors, but we suspect that all are important.

Changes in the use of individual sections

The fall in the use of section 4 is probably due to desirable changes in practices. The Mental Health Act Commission and the codes of practice recommend that section 4 should be used only as a means of immediate admission (Reference JonesJones, 1996). Because of this advice, practitioners may have become more reluctant to use section 4. Similarly, the increase in the number of section 4 admissions which are converted to section 3 may indicate that section 4's use is being restricted to more severe cases, where there is greater clinical certainty that the patient will require a longer admission.

The rise in the use of section 3 may also reflect a desirable change in practice. When the Act was introduced, patients who had never been admitted under section 3 were likely to be admitted under section 2 first. Once a patient is better known to services and has been admitted at least once under a section 3, the professionals involved will be more likely to (appropriately) use section 3 for subsequent episodes of illness. The slower rise in the use of section 2 may reflect its unpopularity with professionals, which is due to the rapid access to review tribunals that section 2 allows and the additional workload that this can cause.

The fall in the use of section 37 is less readily explained, especially given the increasing emphasis on diversion of offenders with mental disorders away from the criminal justice system. It may reflect changes in the availability of hospital beds. The change in the use of section 48 has been dramatic and may be due to several factors. First, more psychiatrists visit prisons than they did 15 years ago and many more prisons now have sessions with local forensic psychiatrists. Second, court diversion schemes may not always divert, but they do lead to the identification of psychiatric disorder. As a result, more people with mental illness now arrive in prison with two things which were not available previously - a description of the offence and a psychiatric history. This in turn may make it easier for prisons to persuade hospitals to accept the transfer. Third, there is a perceived failure of sections 35, 36 and 38 to do what the Butler Committee (Home Office & Department of Health and Social Security, 1975) suggested to get offenders with mental disorders out of prison. Despite changes in the use of the MHA in this population, there remains substantial evidence of unmet need for psychiatric care in prisons (Reference Singleton, Meltzer and GatwardSingleton et al, 1998).

Risk management and the Mental Health Act

We believe that the steady increase in the use of the MHA is an indicator of some of the opposing pressures impacting on modern psychiatry. On the one hand, libertarian, ‘user’-driven pressures continue to demand less hospital-based care and more community services. On the other hand, increasing public concern about the ‘threat’ posed by the mentally ill, and the extraordinary impact made by, and resources devoted to, inquiries that follow undesirable incidents (Reference MuijenMuijen, 1997), lead to a ‘defensive’ practice of psychiatry. Such practice is increasingly dominated by risk management and increasing reluctance to accept risk-taking and uncertainty (Reference HollowayHolloway, 1996). The net result may be a steady increase in the use of coercion, but increasingly fewer resources for this purpose.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ There has been a major increase in the total number of admissions under the Mental Health Act 1983 over the past 15 years.

-

▪ It is likely that this increase has major workload implications for psychiatrists and approved social workers.

-

▪ Despite the general trend, the number of admissions under sections 4 and 37 has fallen.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ The data are based on hospital returns to the Department of Health and may therefore be inaccurate.

-

▪ Some patients may have been admitted more than once in a particular year.

-

▪ Many factors may be acting simultaneously to bring about these changes, and this study was unable to tease out such alternative explanations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by the Department of Health. We thank Sylvia Kingaby of the Department of Health for her assistance in collating the relevant data, and Dr Paul Bowden for his comments on an earlier draft of the paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.