Neoclassicism is now largely eschewed within New Music (aka contemporary classical music). While there seems space in our pluralistic scene for modernist, postmodernist, minimalist, performative and conceptual music, the compositional values of neo-classicism seem out of step and anachronistic. An Australian might say that engaging with neo-classicism today is ‘daggy’, to suggest that such a pursuit is eccentric, unfashionable and uncool. I begin with a historical overview of neoclassicism, where I will respond to problematic political associations, before considering classical principles that I propose should be back on the New Music table.

Neo-classical art emerged in the 1750s, drawing on classical Greece and Rome, with an emphasis on order, balance, clarity, economy and emotional restraint.Footnote 1 It is commonly regarded as the artistic style and dominant culture of the Enlightenment.Footnote 2 While visual arts and architecture of this time are labelled ‘neo-classical’, Western music from the same period is simply termed ‘classical’. In music, neo-classicism refers to a body of music composed primarily between the 1920s and 1940s; the composer most associated with it is Igor Stravinsky, and the pieces he wrote during his long middle period. Other associated composers include Erik Satie, Nadia Boulanger, Darius Milhaud and Germaine Tailleferre. This music is called neo-classical because it reaffirmed the aesthetic attitude of classicism in contrast to the Romantic and modernist attitudes of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The Enlightenment is today critiqued from several perspectives, perhaps particularly because it provided the basis for the ‘aggressive global expansion of European colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade’.Footnote 3 For some, critiques of the Enlightenment can also be read as critiques of neo-classicism. Twentieth-century neo-classicism is also associated with fascism, through the architectural projects of Mussolini and Hitler and because of Stravinsky’s admiration of fascism, tolerance of Nazism until 1938, and explicit antisemitism. For the official culture of fascist regimes, neo-classicism was a call for a return to a better past. Today neo-classicism might be seen as problematic both because of its association with particularly egregious historical regimes – from colonialism to fascism – but also, more broadly, because harking back to the past seems to counter progressive thinking, which holds that critiques of the past will help us produce a better future.

I hope to avoid inadvertently aligning neo-classicism with imperialism because I am not arguing for a nostalgic, unqualified return to a historical neoclassicism, but rather for idiosyncratic and future forms of neoclassicism. While it is important to acknowledge the negative political associations of an artistic attitude, it also seems possible to investigate the usefulness of some aspects of the past without entirely endorsing them. An aesthetic value such as clarity may be associated with Enlightenment thinking, but it is unreasonable to assert that clarity is exclusive to the Enlightenment. I am using neo-classicism as an umbrella term to advocate for certain principles. I will first promote ‘entertainment’, a value not typically associated with neoclassicism, then ‘playfulness and humour’, ‘forms of tonality’ and ‘received form’, before turning to ‘unbalanced structures’, a principle that may lie in opposition to the aesthetics of historical neoclassicism. I end with ‘clarity’, as this principle inflects my thinking about the other categories.

Entertainment

Andy Hamilton argues against ‘the modernist assumption that art and entertainment are mutually exclusive’Footnote 4 and challenges the modernist stance that ‘an artist becomes entertaining only by ‘selling out’.Footnote 5 He argues that while the values of art and entertainment are distinct, they are not inherently oppositional. He proposes three broad categories: the hermetic artist, who produces art that is not entertaining; the pure entertainer, who produces entertainment that is not artistic; and the artist-entertainer, who produces work that is both artistic and entertaining.Footnote 6 He suggests that most great artists fall into the artist-entertainer category, citing William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday as examples.Footnote 7 ‘Entertainment’ is not typically considered an attribute of classicism, but I think it should be. For example, when pianist Paul Lewis characterises Joseph Haydn’s music as ‘sophisticated entertainment that resonates on multiple levels’,Footnote 8 he is effectively situating him as an artist-entertainer.

For over a century, a pressing question in contemporary classical music has been: why are our audiences so small? Some have argued, on aesthetic grounds, that excessive dissonance is a turn-off, or on cognitive grounds that understanding atonality requires training and a commitment that listeners are unwilling to make. David Huron suggests that, as the succession of notes and events in modernist music is often unpredictable, the music does not trigger chemical pleasures that result from successful predictions, or the delightful confusion that can result from unexpected choices.Footnote 9 Hamilton gives us another framework for answering this question: that the modernist view of ‘entertainment’ as the enemy must inevitably lead to diminished audiences. In the late twentieth century, there were many people in New Music who seemed to believe that the fewer fans a work had, the more value it must have; I may have been one of them. This article, however, advocates in favour of entertainment within art and some of the topics I will discuss below, starting with ‘playfulness and ‘humour’, are ways of creating entertaining art. I don’t think entertainment within art is a distinctly neo-classical value, but rather suggest that a return to neo-classical principles can also involve affirming the role of entertainment within art.

Playfulness and humour

Clear structures are a hallmark of classicism. Take, for example, a 16-bar melody with four 4-bar phrases, constructed from two phrase pairs:

This simple structure offers possibilities for playful manipulation. As one school music resource about humour in Joseph Haydn’s music puts it, ‘One of the advantages of the relative simplicity and predictability of the Classical style is that it gives composers the chance to play with audience expectations.’Footnote 10 As the structure of this melody is simple, and as listeners know the template from other pieces, a composer can manipulate the structure, even on it first appearance, by, for example, adding a two-bar extension to the final phrase that delays the closure:

In addition to phrase extensions, typical means for manipulating structures in the classical period included unexpected silences, surprising chord choices, dominant prolongations and hemiola. Such means could be used to fashion larger effects, such as a false ending. Composers could also be manipulative – a word I am using positively – by disrupting genre expectations. For example, Melanie Lowe shows how Haydn’s use of canonic writing in minuets generates ‘topical dissonance’, juxtaposing the ecclesiastical and learned connotations of canon with the secular and courtly expectations of the dance.Footnote 11

Twentieth-century musical neo-classicism is often described as sounding like eighteenth-century classical music ‘with a modern twist’.Footnote 12 For example, we can identify twentieth-century metric and harmonic features in the opening to Stravinsky’s Dumbarton Oaks: the sense of a reliable beat is strong, but the metre is unreliable, as it shifts between 4/4 and 3/4; the music has tonal function, but the chords are extended and full of dissonance. For example, without the horns, the sustained tones of bars 12 and 13 form an E♭ major chord in first inversion; the horns, however, add the notes F and A♭. This E♭ major chord with added 9th and 11th is not a chord one finds in eighteenth-century music and the non-resolution of the dissonant A♭ is particularly strident. The move to an F♯ diminished chord over a G pedal that the music makes in bar 14 is reasonable within an eighteenth-century context but, given the unresolved dissonances of the previous bars, it sounds rather peculiar and jarring.

We can go much further in the way we use contemporary techniques to create a modern twist by, for instance, incorporating microtonally inflected chords, or by utilising rhythmic tricks learnt from producer J Dilla or the metal band Tool. Or we can extend our formal thinking by seeming to abandon a schema that we then complete:

The insert has the potential to create a range of effects, depending on factors such as its material and how that relates to the melody, the emotional register of the work and how this moment is situated within the wider piece. The insert could induce sadness or propose an intellectual puzzle, or it might create a moment of playfulness and wit. Composer-comedian PDQ Bach might have used a technique like this to create a moment of incongruous humour or absurdity. Yet after 1945, lots of these great things that art can do were marginalised within progressive composition.

Forms of tonality

Is my call for neo-classicism also a call for tonality? Not exclusively, but I am enthusiastic about ways composers are engaging with tonality today and see it as a productive way of accessing other principles discussed in this article. I use the open-ended expression ‘forms of tonality’ because I am not arguing for a return to the Common Practice Tonality of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. I support an expansive and pluralistic view of tonality that includes dissonances that don’t resolve, ‘bad’ voice leading, extended chords, new cadences, superfast harmonic rhythm and ending up in a different key to the one you began. We can also incorporate non-tonal elements such as microtonality, sound-mass textures, irrational rhythms and indeterminacy within a tonal context, practices that Graham Hair has termed ‘post-atonal tonality’.Footnote 13

While Stravinsky has been central within New Music discourse, other neo-classical composers have been overlooked. I will make the case for revisiting such composers through looking at the opening section of Darius Milhaud’s ‘Copacabana’, one of 12 short dances in Saudades Do Brasil, a suite for piano written in 1920. ‘Copacabana’ is in ternary form and opens with a melody in B major, with an accompaniment that alternates between the tonic and dominant in G major. Other pieces in the suite feature polytonal passages where one key dominates,Footnote 14 but here the two keys feel evenly balanced. A bridge follows, beginning at bar 21, with a change to a gorgeous three-layer texture where the B-major layer is now surrounded on either side by the G-major layer. The section ends, in bar 29, with a chord progression that moves around the cycle of fifths, across the two tonal layers in parallel.

While the approach to form, texture and rhythm across the suite is conventional, these old-fashioned qualities are offset by the polytonality. The effect of the offset is subjective and hard to pin down. Drawing on Russian Formalist Victor Shlovksy’s concept of ostranenie, one could argue that the polytonality defamiliarises our perception of the old-fashioned qualities and their effects. This concept explains how I hear the cycle of fifths, where this hackneyed progression is revitalised. A meta-modernist might argue that the balancing of the two keys mirrors the balancing of naïve sincerity (old-fashioned qualities) and knowingness (polytonality), to achieve the desired state of ‘knowing sincerity’. More poetically, perhaps the polytonality functions like the crackles, pops and hisses of a vinyl record to enhance emotional response. I enjoy imagining an alternate twentieth-century musical landscape where the rich possibilities of Milhaud’s polytonality inspired as much compositional exploration as Schoenberg’s atonality. I end this section with a call for more melodies in New Music. I don’t have an argument. I simply love great melodies and think it is another aspect that has been sidelined.

Received form

Romantic music is noted for its freedom of form, composers adapting traditional models like the sonata principle in less standard ways and fashioning one-off forms like tone poems. This trend away from historical models was then consolidated in modernism and radical postmodernism.Footnote 15 I may be advocating for formal models, but I do not reject music that eschews them. I appreciate the distinctive structures of, for example, György Ligeti’s Atmosphères and Galina Ustvolskaya’s Piano Sonata No. 6, but I want to consider why so few New Music composers engage with received models.

I also want to argue for short pieces because they offer a specific kind of challenge offering specific types of experiences. For instance, a short piece can present a single spectacular moment of surprise, as in Meredith Monk’s two-and-a-half-minute piano piece, Paris. The opening establishes a tender pensiveness within a post-minimal and modal frame, and for 75 seconds it seems the work will be charming but straightforward. Then an outrageous deviation occurs, but it is short-lived; the work continues as if the deviation had never happened. At the end we are left to wonder what this interruption might mean in relation to the title. Short pieces can offer an action-packed, concentrated adventure or a brief glimpse into something larger. Short pieces are also well suited to the frameworks provided by received forms such as strophic song, rondo form, 12-bar blues, the round or, in the examples that follow, ternary form.

Tell someone in New Music that you are writing a ternary-form piece and you can expect one of two responses. If they want to exclude you, you are naïve, unaware of the past century of modern composition and so not a proper participant within New Music. Or, if they want to include you, you are ironic: your piece has a critical capacity to undermine what the form represents. But why has ternary form been out of circulation within ‘progressive’ composition for a century now? Perhaps the rejection of ternary form was a by-product of the rejection of tonality, which until recent decades was excluded from ‘progressive’ composition. In his 1952 polemic ‘Schoenberg Is Dead’, Boulez convincingly argued that Schoenberg had failed to see that dodecaphony is incompatible with classical forms.Footnote 16 Yet, when subsequent generations of composers returned to forms of tonality, they did not re-engage with tonal formal models. Perhaps composers feel that ternary form is exhausted, but tonality is not, or that new forms of tonality need new formal models. Or perhaps ternary form is uncool because it is too bourgeois.

Ternary form is a three-section form where the outer sections are related, and the middle section offers contrast. It registers the departure-return archetype found in music and storytelling around the world and is a form that poses lots of questions for composers:

OPENING SECTION. Is it singular or does it have multiple components? Does the end of the first section feel complete or open-ended?

MIDDLE SECTION. Does this part feel like an extension of the opening section, or something other? If ‘other’, what is the degree and nature of this otherness?

FINAL SECTION. Has the middle part created a tension that the moment of return releases or are other tensions yet to be negotiated? Is the music the same as the opening or altered? What is the effect of that ending?

We can approach these questions with today’s compositional techniques and aesthetics. Imagine, for instance, how just intonation, extended instrumental techniques, and field recordings could extend possibility. The use of clusters in Scott Walker’s song ‘It’s Raining Today’ offers a brilliant example. The melancholic outer sections feature a simple vocal melody with guitar accompaniment. The opening section presents two verses, with a third verse in the final section. The middle part contrasts strikingly, with a modulation, orchestral instrumentation, an expressive shift from the lacklustre to optimistic and a stylistic move from the folkish to the modern chanson world of Jacques Brel. Using Matthew E. Ferrandino’s terminology, the song can be classified as Embedded Ternary Form as it features an embedded formal model (strophic form) within the larger ternary framework.Footnote 17 The song is already interesting, but its use of cluster makes it exceptional. The strophic verses of the outer sections are unsettled by a continuous string cluster in the upper register, which Isobel Waller-Bridge describes as an ‘umbrella of dissonance’, creating a ‘strange and wonky atmosphere’.Footnote 18 The claustrophobic cluster disappears in the middle part, releasing tension and creating a sense of space that enhances the shift to an optimistic register. Its return at the onset of the final section is quietly devastating. This song’s use of cluster is an inspiring example of the way a post-tonal ingredient can expand the expressive possibilities of both tonality and received forms.

Unbalanced and irregular forms

Idiosyncratic forms of neo-classicism may involve principles, such as unbalanced structures, that lie in opposition to classical aesthetics. I will explore this through two hypothetical examples.

Hypothesis 1: Ternary form piece

Imagine a seven-minute ternary form piece where the opening section is one minute long and ends with a short coda. This is followed by a one-minute B section, and then a reprise of the opening section that is five minutes long because the coda is expanded to four minutes. It is a tonal work and the coda occurs after tonal closure has been established; the coda simply sits in the home key without friction. This four-minute coda is 4/7 of the duration of the entire work, which goes against expectations and makes the form unbalanced, with proportions of 1:1:5.

Hypothesis 2: Pop song

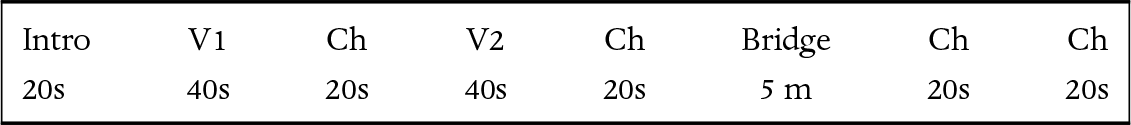

Imagine an eight-minute pop song with a form like this:

After the second chorus in the pop song an enculturated listener might reasonably expect that the song will be approximately 3’30” and that the bridge, if there is one, will last no longer than 30 seconds, 1/7 of the duration of the total song. The listener will be wrong: the song is more than twice the expected length and the bridge is 5/8 of the total duration.

Each hypothesis is potentially exciting because a moment of confusion is created. Confusion in music can have both positive and negative effects. Negative confusion may result from not hearing how the parts of a piece relate to one another, or from musical materials that seem ill-defined, or from music that does not seem to relate to its programme note. Positive confusion could result in the hypothetical forms I propose: for example, some listeners might experience, consciously or subconsciously, the extended bridge of the hypothetical pop song like this:

Then, as the song returns to the formal pattern, the reappearance of the chorus might spark another question: ‘was that a bridge or a digression?’ The extended coda in the ternary form piece does something different, initially prolonging the feeling of arrival and closure, but then, as it goes on, achieving a tranquil stasis.

The nature of formal freedom differs across movements such as classicism, Romanticism, modernism and postmodernism. I suggest that the emphasis on received forms in my examples reflects a classicist approach, where freedom emerges as disobedience within a very present formal model. While neo-classical gardens are often perfectly symmetrical, the irregular phrase structures of Haydn’s music are not; my examples are more extreme than Haydn’s, but they push their logic into a new idiosyncratic future.

Clarity

In his essay ‘Metaphor and Metonymy in Modern Fiction’, David Lodge identifies tendencies in modernist fiction, such as experimental form, ambiguous endings and non-chronological ordering.Footnote 19 Unlike conventional fiction, these tendencies require audiences to put greater effort into comprehension and meaning-making. Lodge’s conception of modernist fiction maps onto much composition of the past century. For example, Lisa Streich’s superb trumpet concerto Meduse is a disorientating experience. Each moment is vividly drawn and unfolds compellingly, but the work has a dreamlike quality that resists straightforward comprehension.

I love such music, but nonetheless want to advocate for work that can be easily understood, even if this involves rejecting my 1990s composition training. This was grounded in modernist techniques and values, such as the underlying belief that we should write music that resisted easy comprehension, only gradually revealing itself during several subsequent hearings. I encountered pieces that at first seemed unintelligible, but I became convinced they were intelligible (and good) after repeated listening. Hearing some of those pieces now, I think my first assessment was correct. There were many reasons why I liked such music, such as wanting to appear intellectual, but I think the main factor was the increased familiarity I gained from repeated listening. Reading David Huron’s book Sweet Anticipation helped me understand that I was mistaking the pleasure I derived from learning the succession of events for artistic value.Footnote 20

Some music is clear in its singularity. For example, in the stripped-down landscape of Eliane Radigue’s Naldjorlak, interference patterns create an experience that attunes the listener to both acoustic and psychoacoustic phenomenon, and Aldo Clementi’s Madrigale presents the simple process of a musical idea gradually slowing down. In each case formal simplicity is at the service of a complex-sounding result that affords a rich listening experience. Such works can become so absorbing that we forget that the music was constructed by a creator. I enjoy such experiences, but here I am advocating for music where we feel the presence of a manipulative composer, a presence that can be felt in different ways. It can be foregrounded abruptly when we are surprised or tricked, such as at the onset of the ‘unexpected and unrelated 29-bar insert’ between the third and fourth phrases in my earlier hypothetical example. A presence can also emerge, as in the hypothetical pop-song bridge whose length becomes puzzling. In each instance, the composer has raised the stakes. Without the deviations, we might conclude that each piece was successful but unambitious; with the deviations, the result may be ambitious and successful or ambitious but unsuccessful. Either way, I am excited by such risk-taking and the way such moments rouse us.

My final example is Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question. The orchestra divides into three distinct layers: the strings play a slowly rotating series of widely spaced chords in G major, over which a solo trumpet plays an atonal melody that serves as the question, receiving an incongruous response from a woodwind quartet. The trumpet repeats the question several times, each time louder, always receiving the same answer. The work ends with the question once more, this time unanswered. The strings inflect this sequence of questions and incongruous answers with a sense of timelessness and quiet profundity. This is not classicism. The work single-mindedly asserts its own rationale and builds its own world. It possesses, however, a key quality of classicism: clarity. It puts forward a clear scenario. One might hear it in other ways, but the title directs us towards the experience I have described. As in Meredith Monk’s piece, to be so utterly clear takes courage. It is a form of aesthetic nakedness that allows us to contemplate such works in their own terms (unanswered questions in Ives, bizarre interruptions that lead to nothing in Monk) and evaluate their execution.

Conclusion

I have used the label neo-classicism as an umbrella term for a set of principles that have fallen out of favour within New Music. I have tried diplomatically to make the positive case for principles I value, but it would be disingenuous of me not to acknowledge that there is also a critical dimension. I think Romantic-modernist aesthetics continue to exert a strong influence on our scene, producing much insufferably formless music under the misguided cult of ambiguity and the mistaken belief that genius transcends the need for structure. It has also led the composer into a strange relationship with the audience, regarding entertainment with suspicion. I challenge these attitudes, advocating instead for ways of thinking about form that engage with received models, archetypes and constraints on creativity. I hope my eccentric examples – unrelated inserts into melodic structures and pop-song bridges that are far too long – make it clear that I am not proposing a reactionary return to convention; these hypothetical examples may be too weird to be neo-classical, but demonstrate where neo-classicism can take us.

Acknowledgements

This paper was first given in the discourse series of the 2025 Impuls Academy in Graz, Austria. Thanks to Uri Agnon, Newton Armstrong, Marianna Ritchey and Vid Simoniti for their helpful comments and for pointing me toward ideas and texts, and to Christoper Fox for his editorial assistance.