1. Introduction

It is a question that appears to announce its own political stakes: “Did you know that a black, openly gay man organized the 1963 March on Washington?” Repeated over and again, in one formulation or another, for at least three decades—the question poses the identity of Bayard Rustin, the figure to which it alludes, as a revelation that promises to transform the very idea of civil rights. This and other such calls to remember Rustin bind his name to the terms “black and gay,” as his sexuality is made into an object of truth, an indispensable fact of his total composition that necessitates disclosure.Footnote 1 Famously little-known, widely recognized as under-recognized, Rustin’s “hidden” legacy is reputed to perform a certain critical labor, when brought to light.

Consider, for example, “Remembering Bayard Rustin,” a short 2006 essay by historian John D’Emilio. In it, D’Emilio details the purported stakes of observing Rustin’s life-history, after lamenting his absence from standard narratives of the Civil Rights Movement. “How could he have figured so prominently at the time [of the Movement] and yet be so peripheral to historical memory today?” D’Emilio asks. “Why have we forgotten Bayard Rustin? And what do we suppress when we forget him?”Footnote 2 Author of the 2003 biography Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin—which established Rustin as an exemplary figure in the history of gay life and the American Left and today stands as the single most cited account of Rustin’s political trajectory—D’Emilio goes on to contemplate the upshot of turning Bayard Rustin into a “household name”:

What would happen if we inserted Rustin fully into the popular narrative of the Civil Rights Movement? We might have to acknowledge that the vision and the energy and the skills of radicals were essential to its success, that agitation for racial justice was often most likely to come from those who stood far outside mainstream assumptions in the United States …. We might also have to acknowledge that the distinction Americans like to draw between the private sphere and the public, between matters like sex and matters like politics, is a fragile one. We might have to acknowledge the complicated intersections between race and sexuality and recognize how love and intimacy become excuses for oppression that crush human lives no less than other forms of injustice. We might, in short, find ourselves with a more truthful version of a vital part of America’s past.Footnote 3

Despite his concluding suggestion that memory of Rustin merely yields “truer” accounts of the Civil Rights Movement, D’Emilio insists that exposure to such “truth” can, itself, compel communities to reimagine basic political categories: public/private, (in)justice, world-historical agency, etc. His attention to the politics of remembering Rustin is important and instructive.

What concerns me and motivates the current study, however, is not whether Rustin is remembered, neither the tendency to forget him nor the degree of his renown, but rather how he is memorialized. In my view, the political purchase of remembering Bayard Rustin as “black and gay” has waned. That is, I am doubtful that framing Rustin in such terms still yields anything of critical significance, much less the sort of conceptual-political insight that D’Emilio outlines. Laboring at the turn of the century—amid skepticism toward gay/lesbian appeals for civil rights—historians, activists, and filmmakers presented the “truth” of Rustin’s life-history as evidence of an identity-in-waiting, grounds for sexual minorities to claim the warrant of the past.Footnote 4 The notion that Rustin was “black and gay” served, in other words, not as a mere descriptive observation, but as a strategic proposition.

Today, however, anti-gay discourse shares terrain with “elite capture” of identity politics, including the conscription of black gay/lesbian life narratives into liberal governing rationalities and corporate managerial practices.Footnote 5 Given, for instance, the ongoing deployment of Rustin as the subject of “intersectional diversity” curricula adopted by multinational investment banks, tech companies, DEI administrators, and the U.S. Department of State—repeated portrayals of Rustin as “black and gay” appear normalized and trite, not so much wrong as irrelevant.Footnote 6 The insistence on the “truth” of his identity, moreover, threatens to be empirically flattening, as all subjects that are not straight, not white (to use historian Kevin Mumford’s titular framing device) are lumped together as a single, homogenized mass and consigned to Rustin’s shadow.Footnote 7 Thus, fundamental differences in political thought and practice are occluded: Bayard Rustin becomes Audre Lorde, who becomes Simon Nkoli and Sylvia Rivera, who become Colman Domingo and (as The Rustin Times, a West African LGBT news outlet, puts it) “all LGBT+ Africans living in Africa and worldwide.”Footnote 8 Rather than continued reclamation of Rustin as a “black and gay” figure, the current moment calls for a reappraisal of his life-history and its enduring significance.

This study excavates a formative (though largely submerged) debate over the life of Bayard Rustin and the meaning of civil rights. Its aim is to submit historical representations of Rustin to renewed empirical—and ultimately political—consideration, by unsettling the framing devices with which he is readily memorialized. My wager is that Bayard Rustin’s designation as a “black and gay” figure is not merely truth-based, nor is such biographical representation ineluctable. Instead, this construal is better understood as one of the many viable renderings of his political profile, formulated at a specific historical juncture. The staying power of this framing is less a function of its sheer veracity than the perceived critical salience of its claims on the Civil Rights Movement.

Note, for example, that although D’Emilio’s 2003 Lost Prophet is often spotlit as the only book-length biography of Rustin, it actually marked the fourth.Footnote 9 The first, which framed Rustin in very different terms, made the New York Times best-seller list in 1997.Footnote 10 An acclaimed stage-play about Rustin also preceded D’Emilio’s account, and an award-winning documentary about him, which began production in the mid-1990s, premiered on PBS the same year Lost Prophet was published.Footnote 11 Just before Rustin’s death, moreover, the Ford Foundation partnered with the Oral History Research Office at Columbia University to commission a multi-year, fourteen-part interview series with him, which resulted in 30-hours of archived audio recordings and a 675-page “oral history memoir” documenting Rustin’s life.Footnote 12 And, just after he died, Amsterdam News, Dissent, Chicago Defender, The New Republic, Black/Out and other magazines and newspapers published multi-page tributes, grappling with his complicated political trajectory.Footnote 13

This series of biographies, memorials, and documentary projects begs a question that highlights the perspectival (that is, political) character of D’Emilio’s account: To whom was Bayard Rustin “lost”?Footnote 14 And, for that matter, which historical developments confirm that he was a “prophet”—rather than, say, an “unreconstructed Cold Warrior,” visionary-turned-proceduralist, or just “some civil rights guy”?Footnote 15 Less defined by the discovery of inescapable “truth” about a long-forgotten figure, Lost Prophet constituted one biography in an already existing field of competing biographical narratives, rival accounts of Rustin’s life and enduring significance. Each biographical rendering of Rustin, each of the necessarily partial efforts to make sense of his political trajectory, advanced a distinct appraisal of civil rights discourse and inter-group conflict.

To counter the reification of any single depiction of him, my analysis historicizes the full range of life-history projects on Rustin and parses their varied political implications. Specifically, I trace the production and uptake of rival biographical accounts of Bayard Rustin, from 1987 (the year of his death) to 2013 (the year in which he posthumously received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from then-President Barack Obama).Footnote 16 The following questions orient this study: If, as all biographical accounts of him imply, Bayard Rustin is an exemplary historical figure, of what developments are his life and political career illustrative? In relation to which public debates and political conundrums are biographical representations of him made to appear as signs of truth or critique?Footnote 17 How does Rustin’s sexuality gather meaning in accounts of his life-history? And, finally, how—and to what ends—have depictions of him changed over time?

By contextualizing and comparing different representations of the same figure over a 26-year period, my research illuminates the ideational currents and historical contingencies that have produced varying biographical accounts. The objective of this study, in other words, is not to assess the veracity of extant writings on Bayard Rustin but to chart the shifting “context of argument” that has informed the telling of his life-history: Which forms of political conduct catalyze social change? How should the boundary between private passions and public life be articulated? Who ought to be the subject of civil rights?Footnote 18 In strategically ordering cause-and-effect relations, valorizing select historical details, and narrating continuity as well as decline, biographies of Bayard Rustin address debates regarding these and other such questions—but not uniformly. In fact, accounts of his life-history have advanced conflicting responses to these debates over time, even as they draw on similar evidentiary sources to recount the same developments. Thus, Bayard Rustin’s career as a biographical subject—what I am calling the “Search for Our Bayard”—is not reducible to empirical discovery and falsification; nor is the political import of remembering him self-evident. Rather, the disputes that animate this “search” reflect and delimit a broader field of political contestation: the ongoing struggle to define the pursuit and proper locus of civil rights.

2. Methodology

Extant accounts of Bayard Rustin’s life-history include a variety of genres: book-length biographies, edited volumes, stage-plays, documentaries, historical fiction, children’s books, and young adult nonfiction. Others have also written about him in accounts of discrete historical events (e.g. the March on Washington) and in biographical depictions of his contemporaries (e.g. writings on A. Philip Randolph). While I consider this entire universe of cases important, my analysis centers five key portrayals of Rustin produced between 1987 and 2013.Footnote 19 These include Bayard Rustin: Troubles I’ve Seen by Jervis Anderson; Bayard Rustin and the Civil Rights Movement by Daniel Levine; the stage-play “Civil Sex” by Brian Freeman; the documentary Brother Outsider by Bennett Singer and Nancy Kates; and Lost Prophet by John D’Emilio.Footnote 20 Each of these accounts marshals original research to chronicle Rustin’s life-history. Subsequent writings on Rustin largely recapitulate the findings and themes of these earlier works.Footnote 21

To contextualize the cases I have selected, I also examine the memorial service held for Rustin; the several obituaries published just after his death; the research notes and archival collections of those who have written about him; as well as other unpublished and published materials that offer insight into the wide range of claims regarding his standing in history. Crucially, the John D’Emilio Papers at Swarthmore College, Daniel Levine Papers at Bowdoin College, “In The Life” Archive at the Schomburg Library, and private records held by the Bayard Rustin Estate include unedited oral history interviews and other collected source materials. These repositories provide rare opportunities to observe shifting methodological assumptions and political investments between biographical accounts. Where archives are unavailable, I rely on interviews with important figures, including Bennett Singer, Nancy Kates, Brian Freeman, and Rustin’s surviving partner, Walter Naegle.Footnote 22

Following the growing research in American Political Development and Historical Sociology regarding the politics of narrative, I interpret biographies of Bayard Rustin as “ethically constitutive stories.”Footnote 23 Specifically, I read each portrayal of Rustin for what it indicates about the meaning of civil rights, including how and by whom they were—and ought to be—pursued. Like other “stories” that have shaped debates over the Civil Rights Movement and its legacy, biographies of Rustin do not entail aimless description. Rather, they offer purposive accounts of his life-history, reflecting certain value judgments and tendering normative conclusions.Footnote 24 My analysis distills the fundamental narrative that structures each biography of Rustin, contextualizes their respective political implications, and compares across cases. I attend closely to what each portrayal of Rustin foregrounds, repeats, and omits, as well as thematic patterns among biographies and divergent representational practices between them. In this way, I draw methodological cues from works by Michel-Rolph Trouillot and David Scott on the production of history and the conceptual-political labor of historical narration.Footnote 25 At stake in rival “stories” about Rustin are not just public memories of him but public debates over political conduct, issue definition, and the very idea of civil rights.

My analysis unfolds over three sections. The first sketches the debates about Rustin’s life-history that emerged in 1987—just after Rustin’s death and years before the publication of any full-length biographical account. As historian Alan Brinkley put it in an essay regarding such debates: “One Was a Multitude.” That is, Rustin wore so many hats over his half-century of political engagement that “even his admirers had some difficulty articulating exactly what had made him a significant figure in the nation’s recent history.”Footnote 26 There was, in other words, no ready script or consensus regarding how he ought to be remembered, only disparate and competing claims about his trajectory. Those concerned with memorializing Rustin, then, were not left with a pre-given or self-evident “story.” Rather, they inherited cacophonous reflections on his political positions and other “noisy data.” Coherently narrating his life-history would require select valorization, political judgment, and, in some cases, speculation.Footnote 27

Section two (1988–2000) examines the earliest biographical depictions of Rustin. Published in the aftermath of the 1992 Los Angeles Riots—amid debates over black nationalism and “post–civil rights” racial violence—the first two book-length biographies of Rustin cast him as an exponent of non-violent “self-discipline.” Such discipline, the authors lament, tragically lost its appeal in the late twentieth century, as the “irrational” and “self-immolating” habits of “identity politics” and “multiculturalism” displaced nonviolent reconciliation. A longing for a return to the purported fundamentals of civil rights struggle—namely, “controlled demonstration” and discretion—animates these accounts of Rustin’s life-history. Thus, early biographies of Rustin advance the notion that the pursuit of civil rights (and political movement, in general) requires “self-discipline.” Any project lacking such discipline, they suggest, is out of step with the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement and wrongheaded. Where readers today might expect portrayals of Rustin as a “black and gay” figure, he is construed as one who would have found such inter-subjectification parochial and anathema to progressive politics.

The third section (1997–2013) examines the production and reception of the now-conventionalized notion that Rustin was “black and gay.” Shifting the focus to debates over whether gay/lesbian communities could legitimately claim civil rights—historians and artists at the turn of the century paired revised imagery with newly valorized historical details to endow Rustin’s sexuality with increased significance. The upshot is more than empirical revision. With the politics of sexual difference held in view, Rustin’s life-history, their accounts insist, points to the “unfinished” work of the Civil Rights Movement, not the conciliatory techniques of its classical phase. This narrative became crucial for black gay/lesbian activists, as they drew on depictions of Rustin to articulate lines of historical continuity between “cross-cutting” political issues (e.g. HIV/AIDS prevention, gay/lesbian outreach programs, and anti-discrimination ordinances) and the Civil Rights Movement.Footnote 28 In 2013, then-President Barack Obama ceremonially reified such continuities, by affirming Rustin’s pursuit of equality “from his first Freedom Ride to the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Rights Movement.”Footnote 29 Finally, I end this article with a few notes toward an alternate rendering of Rustin. Instead of recovering his singular authority vis-à-vis the Civil Rights Movement, the concluding “story” illuminates the manifold history of black politics by reappraising the specificity of “black and gay” peoplehood.

To some readers, my central claim—that shifting narratives about Bayard Rustin reflect and delimit debates over civil rights—may seem a bit odd, given his relatively marginal status as a civil rights figure. If few people are familiar with Rustin, one might ask, are changes in the telling of his life-history appreciably consequential? In other words, is anyone really paying attention? Perhaps an investigation of figures whose names have become synecdoches of the Civil Rights Movement (e.g. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and Malcolm X) would be more telling.Footnote 30 However, given the Oscar-nominated Netflix film on his life-history produced by the Obamas, Bayard Rustin is no longer characterizable as “marginal.”Footnote 31 And, in any case, I argue that it is precisely because Rustin is perceived as an outlier that representations of him are politically significant. Largely intended for audiences that are either unfamiliar with his work or skeptical of his importance, biographies of Rustin are often recuperative, never just informational. That is, they do not entail mere observations about his trajectory but pointed reflections on why, given some set of political debates, he must be “restored” to public memory. Because of his reputation as a “forgotten” figure, moreover, claims about Rustin’s life-history often go undisputed.Footnote 32 Reports tend to celebrate the promise of his recovery—e.g. an “unsung hero finally gets his due”—without scrutinizing its assumptions.Footnote 33 Hence, once articulated, the political import of remembering Rustin is taken for granted. In keeping with insights from Queer Theory and Transgender Studies, then, I argue that Bayard Rustin’s apparent marginality has long been constitutive of his signifying power: he is “little-known” and therefore made to emblematize the edges of prevailing ideals and universal categories.Footnote 34

Finally, it is worth reiterating here that my objective is not to recover the “original” Bayard Rustin or reveal the “real truth” about him. (The reader will find that Rustin was a moving target whose life-history does not lend itself to such essentialist notions.) Nor is my aim to study his political thought as such.Footnote 35 What concern me are the narratives produced about him and their political uses. I strive to offer enough textual evidence and historical detail to provide the reader with a clear sense of how—and to what ends—the biographies under review portray Rustin, without becoming mired in archival minutiae. This requires moving between key moments of each to concisely reconstruct its basic narrative. In every case, my focus is on the interplay between the telling of Bayard Rustin’s life-history and public debates over civil rights.

3. One man, many “stories” (1912–1987)

On October 1, 1987, 1 month after Bayard Rustin’s death, Rustin’s friends, family, and comrades gathered in New York City to hold a memorial service in his honor. The funerary program included remarks by guests ranging from U.S. House Representative John Lewis to South African trade unionist Phiroshaw Camay and Norwegian actress and humanitarian Liv Ullmann. This array of speakers reflected the variety of projects Rustin engaged over his near half-century of political work: international pacifism and racial integration, anti-nuclear protests in the Sahara Desert and teacher strikes in Newark.Footnote 36 Their remarks, moreover, offered varying propositions regarding Rustin’s enduring significance.

For example, AFL-CIO President Lane Kirkland insisted that Rustin would, “no doubt and quite properly, be remembered as the master strategist, and one of three or four most inspiring leaders of the black civil rights revolution.”Footnote 37 Foregrounding, instead, Rustin’s pioneering support for the struggle against Apartheid, Phiroshaw Camay likened Rustin to Steve Biko, founder of the South African Black Consciousness Movement. Both, he contended, would be recognized across the black world for their “revolutionary leadership” and “genuine and deep concern for civil liberties and economic participation.”Footnote 38 Still others highlighted neither Rustin’s U.S. civil rights organizing nor his participation in transnational black liberation movements, but rather his work with refugees. To Rabbi Marc Tanenbaum, Director of International Relations of the American Jewish Committee, it was Rustin’s humanitarianism that would secure his “immortality,” or eternal renown. Alluding to active refugee crises, Tanenbaum insisted that Rustin’s life “was a testament, out of the particularity and uniqueness of black suffering and the Black Exodus … to Jewish suffering and the Jewish Exodus, and the suffering of people in Thailand, in Vietnam, Southeast Asia, and Africa, and Latin America, and elsewhere.”Footnote 39

Figure 1. Cover of the program for Bayard Rustin’s memorial service.a

This insistence on remembrance and esteem for the deceased might seem banal in the context of a memorial service, especially one for a political figure. However, in this case, the wide-ranging funerary remarks evinced a certain anxiety.Footnote 40 In the immediate aftermath of Rustin’s death, there was little clarity around how he ought to figure into public memory. Whereas the speakers at the memorial service framed Rustin in relation to exemplary political leaders and ongoing issues, obituaries struggled to make sense of his issue positions or trace the through-line of his political trajectory. “Although he spent nearly half a century in the forefront of the civil rights struggle,” the Washington Post noted, “[Rustin] held many views that were unpopular with some influential blacks.” The obituary continued by observing that Rustin broke rank with other black leaders by opposing “quotas in employment and education, which he thought were destructive to members of all groups.”Footnote 41 Others noted that he curiously disparaged Black Studies programs and compared the Palestine Liberation Organization to the Ku Klux Klan.Footnote 42 The New York Times printed laudatory remarks by Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) chairman Roy Innis, each of whom insisted on Rustin’s general importance to racial politics. It also, though, recirculated a damning appraisal given by CORE co-founder James Farmer: “Bayard has no credibility in the black community … [his] commitment is to labor, not to the black man.”Footnote 43

As these multi-vocal death notices raised questions about how to remember Rustin, public-facing civil rights memorials threatened to sweep him into the dustbin of history. Consider the 1987 Emmy-award winning docuseries Eyes on the Prize, which PBS branded the “definitive story of the civil rights era.” In its 6 hours of total screen time, Rustin is mentioned and shown only once, for about 4 seconds, during a brief discussion regarding the logistics of the March on Washington.Footnote 44 Rustin, then, had no inevitable place in history, and the larger meaning of his life appeared neither self-evident nor easily articulable. Having traversed multiple categories throughout his career—Race Man and Marxist, humanitarian and Zionist, national strategist and “globe-girdling” lecturer—he left both the through-line and upshot of his record open for debate. Subsequent efforts to narrate Rustin’s life-history would not resolve this debate; they served only to raise its stakes, as biographers linked rival claims about him to broader fields of political contestation.

4. Snow on the roof, fire in the furnace: Nonviolent conduct of the “Obligatory Homosexual” (1988–2000)

The first two book-length biographies of Rustin—Bayard Rustin: Troubles I’ve Seen by Jervis Anderson and Bayard Rustin and the Civil Rights Movement by Daniel Levine—address debates over political conduct and protest strategy in the “post–civil rights” era. At the outset of his account, Levine, an historian of American Liberalism at Bowdoin College, charts this “context of argument” and figures Rustin in relation to it using a pointed vignette. “Bayard Rustin was an inmate at the Ashland, Kentucky, Federal Correctional Institution from March 9, 1944, to July 1945,” the opening line of the biography reads.Footnote 45 Convicted of violating the Selective Service Act, Rustin advocated for cell block desegregation throughout his sentence—much to the chagrin of some white inmates. During one of Rustin’s unauthorized trips to a whites-only cell block, a disgruntled white inmate grabbed a mop from a utility closet, rushed toward Rustin, and beat him with its handle. A few of Rustin’s comrades came to his defense, Levine notes, but Rustin told them to stop. The white inmate beat Rustin, without interruption, until the mop handle broke. Rustin “did not resist; he simply endured the beating.” The white inmate, reportedly “unnerved by Rustin’s nonresistance,” eventually stopped beating him, was apprehended by guards, and sent to solitary confinement. Rustin, though left with a broken wrist, emerged victorious—Levine insists—because he won favor with the prison warden and could amplify his fight for cell block desegregation.

Levine presents this introductory vignette as a reflection of Rustin’s signature commitment, the through-line of his political work. That is, in his view, Rustin modeled the “moral jiu-jitsu” of nonviolence, wherein the “unexpected nonviolent response to violence clearly unnerves the aggressor.”Footnote 46 Intent on highlighting this ideal, Levine poses nonviolence, its inner-workings and transformative potential, as the point of departure for his biographical account. (In fact, Levine was so invested in emphasizing Rustin’s nonviolence that he originally planned to title the biography Mr. NVDA, i.e. Nonviolent Direct Action. His publisher, however, found the proposed title too niche and encouraged him to use the more general framing, Bayard Rustin and the Civil Rights Movement.Footnote 47)

As he foregrounds nonviolence, Levine makes clear that his biographical account is more than an antiquarian exercise. Rather, he is explicitly motivated by discontent toward what he describes as “self-immolating” and “self-destructive” rhetoric among minority groups. In particular, Levine denounces the rise of black nationalism, separatism, and “loud anti-Jewish shouts” in the “post–civil rights” era; such rhetoric had, in his view, tragically supplanted the conciliatory strategies that Rustin pioneered.Footnote 48 Having embarked on the project just after the spectacle of the 1992 Los Angeles Riots—amid calls for Leftists to emulate the “good ‘60s,” not the “bad ‘60s”—Levine took his biography of Rustin as an occasion to reclaim the promise of nonviolence, the “high ground” of the Civil Rights Movement.Footnote 49 He lays bare this investment toward the end of his introduction, as he articulates why Rustin is worth remembering:

[Rustin] teaches us much about the shape of the Civil Rights Movement: its coalescing, its near falling apart, its continued survival. Looking back at the years up to the middle sixties, one marvels at the pace of change. Looking back at the years after the middle sixties, one thinks of the alternatives Bayard Rustin presented, and is tempted to repeat over and over again “if only.”Footnote 50

Thus, animating Levine’s account is not some neutral interest in documenting Rustin’s life, but a longing to recover the political alternatives for which Rustin stood; given his appraisal of the “post–civil rights” era, Levine affirms nonviolence as the most pertinent.

If Levine takes the promise of nonviolence as his point of departure, Jervis Anderson—a staff writer for The New Yorker, A. Philip Randolph biographer, and speechwriter for Rustin—structures his biographical account around the “psychological requisites” of pacifist techniques.Footnote 51 Anderson follows Rustin’s own narrativizing:

To hold a philosophy of nonviolence in a time of crisis depends to a large extent on an inner discipline, and one may think he has it when he has not. It is very easy for us to make, in a calm intellectual atmosphere, a judgment as to how we would behave, only to discover that in a time of emotional crisis we have not enough emotional strength to carry through.Footnote 52

More than nonresistance or mere passivity, nonviolence—Rustin instructs—fundamentally requires self-discipline and equanimity. Accordingly, Anderson’s account tracks Rustin’s cultivation of what the author variously describes as “spiritual discipline,” an “ascetic Gandhian sensibility,” a passion for sacrifice and “self-effacing” work. With an eye toward the public debates over nihilism and urban rebellion shaping “post–civil rights” discourse, Anderson underscores Rustin’s insistence that nonviolence demands the sort of “rigid self-discipline that prevent[s] emotionalism from displacing cool and creative thinking.”Footnote 53

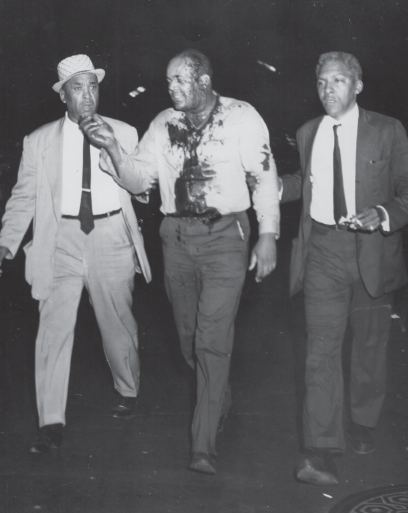

Figure 2. Bayard Rustin escorting John Cannon during the 1964 Harlem Riots. Levine notes that Rustin sought to demonstrate the “distance between his brand of controlled demonstrations and a growing anger in the black community that could lead to what he regarded as irrational and self-defeating demonstrations.”a

Levine and Anderson’s overlapping concerns impel them to spotlight similar historical developments in their respective biographical accounts. For example, concerned with urban rebellion and the enduring appeal of black nationalism, both mine Rustin’s efforts to “cool” riots (e.g. the 1964 Harlem Riots) and teach activists “nonviolent discipline.”Footnote 54 Troubled by expressions of violence and nihilism, both underscore Rustin’s criticism of what he called “frustration stupidity” or “frustration-politics”—that is, “self-defeating” and “irrational” political behavior within black communities (e.g. Rustin’s 1968 address to the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, The Anatomy of Frustration).Footnote 55 In narrating Rustin’s life-history, then, each account tells a “story” about the importance of discipline in the pursuit of civil rights.

Crucially, however, as they narrate Rustin’s calls for “nonviolent discipline,” both biographers clarify that it did not spring from some innate capacity for personal restraint. Rather, Levine and Anderson insist that Rustin struggled with “inner discipline,” often acting on impulse and falling into patterns of impropriety. In this way, Rustin’s sexuality becomes an important dimension of each account: he is portrayed as a figure whose lack of sexual discretion ran counter to pleas for “disciplined” self-fashioning. Consider, for example, Levine’s discussion of Rustin’s sexual behavior during his sentence at the Ashland, Kentucky Federal Correctional Institution. If Levine celebrates Rustin’s use of nonviolence (as he does in the introductory vignette of his account), he is critical of Rustin’s “flagrant, almost defiant” homosexual activity in prison. Levine spares explicit detail, noting only that Rustin’s sexual practices were unusually “extreme and almost open.” The “moral jiu-jitsu” deployed in his fight to desegregate the penitentiary was partially undermined, Levine explains, by his “indiscreet, almost defiant” sexual proclivities. That is, Rustin’s “blatant homosexuality allowed [prison] authorities, as well as some of the inmates, to see him as simply a troublemaker, as a ‘psychopath,’ as ‘depraved.’”Footnote 56 Diagnosed with “psychopathic personality, homosexuality”—and later deemed an “obligatory homosexual,” or one whose sexual desires were hopelessly incontrovertible—Rustin was reprimanded for his indiscretions on multiple occasions and placed into “administrative segregation.” Notably, Levine holds that Rustin, “too, felt that his actions deserved condemnation and even self-denigration,” adding that he longed to “control his aberrant sexual impulses.”Footnote 57

Anderson likewise portrays Rustin as a deeply tortured man whose sexual indiscretions betrayed his stated commitments to “rigid self-discipline.” He explains that Rustin’s comrades—many of whom found the “bold flaunting of his sexuality” troubling—urged him to “restrain his sexual behavior whenever or wherever he appeared as a representative” advocating for some political issue; “surely that wasn’t an unreasonable demand,” Anderson adds.Footnote 58 Still, many of Anderson’s interviewees insisted that Rustin buckled under temptation. While some reported admiring Rustin’s seeming lack of shame, others (those whom Anderson foregrounds and quotes at length) decried his apparent lack of self-control. For example, Anderson spotlights the following anecdote recounted by pacifist activist Rascha Hughes:

During the late 1940s, a married couple in our movement weren’t getting along so well. Bayard saw that opening and couldn’t resist exploiting it. In a short time, the marriage was completely destroyed. The husband, a lovely man who played the viola, said to me after he got involved with Bayard, ‘You know, I’ve never been so happy.’ He was like a child who had suddenly discovered something new about himself. But Bayard wasn’t discovering anything new about himself. He was like a predator.Footnote 59

Where Hughes regarded the unnamed man’s newfound same-sex desire as an indication of self-actualization, she framed Rustin’s ‘predatory’ behavior as a reflection of depravity and inner turmoil.

To Anderson, this and other such reports of Rustin’s “blatant homosexuality” clarify an indispensable facet of his “story”: Just as he urged nihilistic, riotous black nationalists to “cool” their frustration, Rustin needed to (in Anderson’s words) “control his gay lifestyle.”Footnote 60 Once again, Anderson hones closely to Rustin’s own writings. In particular, the suggestion that Rustin’s sexual indiscretions violated his commitment to “nonviolent discipline” is informed by an excerpt of a letter Rustin authored in 1953. Written just after his infamous arrest for “lewd vagrancy” in Pasadena, California, the letter entails Rustin’s contrite reflections on nonviolence and sexual desire:

No matter where I work in the future, where I live and with whom I am, I have pledged before God that I will live more nonviolently in the small ways that support the big ones, if they are to be real. While sex is a very real problem, and while it has colored my personality, I now see that it has never been my basic problem. I know now that for me sex must be sublimated, if I am to live with myself and in this world longer. For it would be better to be dead than to do worse than those I have denounced from the platform as murderers. Violence is not so bad as violence and hypocrisy …Footnote 61

According to Anderson, Rustin’s letter suggests that sexual indiscretion is as politically imprudent as the “frustration stupidity” of riots. Together, through their complimentary claims about Rustin, Anderson and Levine affirm “coolness” and sexual discretion as equally necessary conditions of “disciplined”—and therefore effective—political action.

Figure 3. Bayard Rustin with A. Philip Randolph (Undated). Jervis Anderson includes this photograph in his account of Rustin with the caption, “Father and Son.” “Bayard had a high respect for those people in his political life who counterbalanced his tendencies toward the dramatic and the flamboyant.”a

What emerges through these accounts, then, is an analogy between nihilism and frustration, on one hand, and sexual indiscretion, on the other. Both reportedly threaten to displace the “cool and creative thinking” progressive politics requires. Put differently, if the “self-immolating” character of riots pointed to the dead-ends of “frustration-politics,” Rustin’s “blatant homosexuality” revealed the pitfalls of sexual indiscretion; “emotionalism” supplanted rational decision-making in the former case, while “aberrant” impulses distorted capacities for ethical judgment in the latter. The upshot of this analogy is the notion that the pursuit of civil rights (and political movement, in general) necessitates “self-discipline,” both emotional and sexual. Anderson draws this analogy directly, as he speculates that Rustin’s calls for “inner discipline” may have been “not only about the tests of [one’s] political commitment but also about a difficult side of his personal history.”Footnote 62 Alluding to Rustin’s sexuality, Anderson suggests that Rustin’s pleas for equanimity among activists reflected a personal yearning for sexual discretion and self-control.

Levine figures this analogy differently. Take, for example, his account of the following confrontation between Rustin and an “anguished” black student during a 1964 lecture at Bowdoin College. (Levine reports having been in attendance during the lecture and cites it as part of what first inspired his interest in Rustin’s life-history.Footnote 63) The confrontation began when the “anguished” student challenged Rustin’s calls for “nonviolent discipline”:

You … you are so rational. How can you tell me, a 20 year old Negro, to act rationally in the face of an irrational situation? Why do you tell me this? Why can’t there be stall-ins, garbage on bridges? Why? Why should you tell me to be moderate? How can you ask me to believe in non-violence?

When the student finished speaking, “silence echoed the total desperation of his posture.” Rustin withdrew temporarily “as he worked with his heart to control the closeness of his tears.” Then, gesturing toward the student as if they were the “same person,” he replied:

You must not push a man so far into a corner that he becomes desperate … you and I must do more than simply react …

And of course you say, But why should Negroes be treated this way and still have to be super nice people? I say, because we are a chosen people … chosen to help free everybody, black and white, from the curse of hate. This is my cause. This is my belief. This is my non-violence.

But you are young and I am old, and I have talked too long. But do not think that just because there is snow on the roof there is no fire in the furnace.Footnote 64

Though not explicitly distilled in Levine’s recounting, the double meaning of Rustin’s concluding metaphor, “snow on the roof … fire in the furnace,” is no simple coincidence. Rather, it gives expression to Levine’s account of Rustin’s calls for “nonviolent discipline.” On one hand, the metaphor suggests that an outer display of rationality and “coolness” (or “snow on the roof”) may strategically conceal inner anguish (or “fire in the furnace”): one can be tactically equanimous, yet deeply frustrated with unjust conditions. In popular parlance, however, the same metaphor carries sexual innuendo: it is typically used to describe an older person whose advanced age (signified by gray hair, or “snow on the roof”) belies enduring sexual virility (or “fire in the furnace”).Footnote 65 In each case, it is the privacy of passions—whether emotional or sexual, concealed rage or discreet desire—that is underscored.

Keeping with this analogy, Levine goes on to note that Rustin’s investments in “discipline” and concealed passions prompted a certain ambivalence toward the emergence of gay politics. That is, if Rustin was critical of the “frustrated” tactics shaping black nationalism, he was also wary of the “indiscreet” aims animating gay liberation. Levine briefly cites one striking example: in 1969, Rustin reportedly insisted that a pacifist organization expel one of its members for publicly “coming out” and thereby risking the group’s reputation.Footnote 66 Levine notes the irony of this, writing that “a person who had gone through what Rustin had gone through [in prison, for example] might have been more understanding of [a comrade’s choice to ‘come out’].” Still, Levine’s point here is that Rustin’s sexuality did not render him instinctively supportive of gay politics, nor did his own subjection to anti-gay stigma leave him readily empathetic toward such collective ambitions. Instead, his investments in “coolness” and discretion purportedly made him suspicious toward “blatant” disclosures of same-sex desire.Footnote 67 (Levine’s archived research notes indicate that he discussed this issue directly with his interview subjects. For example, in an unpublished exchange, one of Levine’s interlocutors explained how puzzling he found attempts to cast Rustin as “one of the heroes of black gay liberation,” given Rustin’s own ambivalence toward sexual indiscretion. Levine, too, objected to such framing and suggested that it could hardly be taken seriously.Footnote 68)

Ultimately, Levine and Anderson advance more than a set of idiographic descriptions. Through their complimentary accounts of Rustin, these biographers insist on the strategic value of “self-discipline.” Hardly framed as a “black and gay” figure, Rustin is cast as one who would have found such political formations troubling and out of step with the Civil Rights Movement, had he lived long enough to witness them unfold through the end of the twentieth century. Levine moves beyond historical analogy and metaphor to articulate this point explicitly. In a section that extols the 1963 March on Washington, Levine frames the success of the event as the greatest reflection of Rustin’s political aims. “Any sort of ‘identity politics’ or ‘multiculturalism,’” he goes on to add “was for [Rustin] anathema.”Footnote 69 Wittingly defying the mandates of History, Levine draws anachronistically from “post–civil rights” political vocabularies to tender a normative conclusion. By setting the March on Washington against calls for “identity politics” and “multiculturalism,” he observes a sharp contrast between mid-century liberal-labor-civil rights coalitions and late-twentieth century multiracial-feminist-gay/lesbian groups. If Rustin found purpose in the successes of the former, Levine suggests, he would have taken issue with the strategies of the latter. Thus, the telling of Rustin’s life-history is configured to stir skepticism toward “black and gay” political formations. To the extent that Levine and Anderson spotlight race and sexuality in their respective biographies, they do so to call into question—not underscore—the enduring political salience of such categories.

Given Bayard Rustin’s standing as a “black and gay” icon today, it might be tempting to dismiss Bayard Rustin: Troubles I’ve Seen and Bayard Rustin and the Civil Rights Movement as mere “respectable” narratives developed by “conservative” biographers. However, while the personal biases of each author undoubtedly shaped their respective accounts, I submit that it is more productive to consider the discursive limits imposed by the “context of argument” within which these biographies were written. Animating these texts is not just what the authors longed to say, but also what remained yet unsaid or difficult to imagine in the “post–civil rights” era. In his unpublished notes, for example, Levine writes about his attempts to interview Rustin’s former lovers—men who may have given him different perspective on Rustin’s calls for “discipline”—only to find that some had gone on to marry women and therefore refused to be interviewed or identified with Rustin in any way.Footnote 70 Anderson writes about others who were reticent to discuss their relationships with Rustin, cut interviews short, or did not want their names printed in the final manuscript.Footnote 71

But perhaps it is Rustin’s memorial service that most tellingly reflects such discursive limits. Of the many ways speakers described Rustin during the service (e.g. tactician, socialist, transnational leader, humanitarian), none figured him as a “black and gay” political actor. Most did not mention his sexuality at all, while others referred to it euphemistically.Footnote 72 Though certainly indicative of at least some degree of homophobia among attendees, this “silence” was not reducible to discrete prejudice. In fact, given the entrenched animus toward homosexuals in 1987—the same year that U.S. Senator Jesse Helms described gay men as “perverted human being[s]” while introducing an amendment to curtail HIV/AIDS funding, and just 1 year after the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of sodomy law in Bowers v. Hardwick—the speakers at the memorial service likely thought they were safeguarding Rustin (as well as his surviving partner) by disclosing little about his sexuality.Footnote 73 In other words, the now-conventionalized notion that Rustin was “black and gay” did not merely go unsaid in the immediate aftermath of his death. Rather, given the state of “post–civil rights” discourse on homosexuality, such biographical representation appeared utterly degrading, if not unthinkable.

5. The man and the “mask”: Civil rights, unfinished (1997–2013)

Between 1993 and 1997, gay/lesbian organizations across the United States increasingly re-articulated their demands for legal protection and political visibility as “civil rights” claims. This strategic shift prompted a national debate over issue definition: What counts as a “civil rights” issue? Who ought to be the subject of civil rights? Gay/lesbian advocates argued that homosexuals faced forms of political subordination that were analogous—and in some cases linked—to racism.Footnote 74 Many, for example, likened the ban on homosexuals in the military (and later “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”) to racial segregation. Others drew comparisons between Bowers v. Hardwick (1986) and Dred Scott v. Sanford (1856): the former affirmed the constitutionality of sodomy law, as previously mentioned, while the latter held that black people were not entitled to the rights of American citizenship.

Opponents, however, insisted that gay/lesbian communities could not legitimately claim civil rights, because their political grievances were not at all analogous to those that shaped the Civil Rights Movement. In a 1993 letter to the New York Times, for instance, Unitarian pastor Dennis Kuby denounced the “misappropriation” of civil rights by gay/lesbian organizations, writing: “Gays are not subject to water hoses or police dogs, denied access to lunch counters or prevented from voting.”Footnote 75 There was, in his view, no comparison between homophobia and Jim Crow. Likewise, while protesting a 1997 Washington state ballot measure concerning sex-based discrimination, Alveda King, niece of Martin Luther King, Jr., declared that the very notion of gay/lesbian civil rights threatened to tarnish the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement: “To equate homosexuality with race is to give a death sentence to civil rights …. No one is enslaving homosexuals or making them sit at the back of the bus.”Footnote 76 Such opposition framed blackness and homosexuality as distinct and unrelated social formations; the resulting suggestion was that gay men and lesbians were neither a part of the Civil Rights Movement nor members of black communities at all.

Figure 4. Gay Men of African Descent (GMAD) members Colin Robinson and Charles Angel at the scene of a protest, following the 1986 Bowers v. Hardwick ruling. Robinson went on to help found the Audre Lorde Project. Its first fundraiser included a discussion of “Civil Sex,” Brian Freeman’s 1997 play about Bayard Rustin.a

If the earliest biographies of Bayard Rustin address debates regarding protest strategy and political conduct in the “post–civil rights” era, the second wave of accounts addresses disputes over political membership and issue definition. Historians and artists turned to Rustin to make sense of the relationships between gay/lesbian communities and the history of civil rights.Footnote 77 Not only did this require a different look at Rustin; it also required reappraisal of the very methods and sources used to narrate his life-history. Consider, as a point of departure, the following unpublished exchange between John D’Emilio and Doris Grotewohl Baker—one of the many people D’Emilio interviewed while completing research for his biographical account. D’Emilio began the interview with Baker, a former colleague of Rustin’s, with a general question: “From your experience of Bayard … how do you think he should be remembered?” She responded:

Baker: If you ask me how I remember him, I remember him as The Voice.

D’Emilio: What do you mean by that? The voice.

Baker: He had a beautiful speaking voice, as well as a singing voice …. He came from Barbados. And the British overlay in his speech was evident in ordinary conversation. So, his voice was distinctive … when I think of Bayard and the voice, it’s a total thing.

D’Emilio: Did he tell you he came from Barbados?

Baker: Yes. Isn’t that true?

D’Emilio: No. [Bayard] was born and raised in West Chester, Pennsylvania.Footnote 78

Baker’s responses throughout the remainder of the interview were marked by uncertainty, perhaps even embarrassment. Levine and Anderson cite letters between she and Rustin as key archival findings in their respective biographical accounts—but how could Baker be considered a reliable witness to Rustin’s life-history, if she quite literally did not know the first thing about him, his country of origin? Searching for answers, Baker wondered if Rustin had traveled to the West Indies frequently (he had not), or if there was some other detail she was missing about his background.

In D’Emilio’s view, however, Baker’s error was not unusual; it reflected a larger empirical pattern within his interview data. That is, many of his respondents appeared to be unclear on several details regarding Rustin’s life-history—including his birthplace (some thought he was from Jamaica, others assumed London) as well as his familial background, educational history, etc.Footnote 79 Whereas earlier biographies regarded this sort of “noise” in the data as a result of Rustin’s undisciplined self-fashioning, D’Emilio, an historian of twentieth century gay life and politics, submits that this pattern points to a dimension of Rustin’s subjectivity that others failed to detect: “Rustin … affected a pose—his own version of the mask that gay men of the era wore—and his dissembling fooled contemporary observers and historians alike.”Footnote 80 Put differently, Rustin was not a transparent or predictable figure, D’Emilio suggests, but rather one who dealt in strategic affectations, often masking his “true” intentions and withholding personal details. Those who took Rustin’s words and habits at face-value had, in D’Emilio’s estimation, misjudged him and the ideals for which he stood.

D’Emilio thus advances a different interpretive practice. Take, for example, his re-narrativization of Rustin’s sentence at the Ashland, Kentucky Federal Correctional Institution. As previously discussed, earlier biographers (Levine and Anderson) insist that Rustin harbored contrition and self-denigration as he faced the realities of his “aberrant sexual impulses” in the penitentiary. But D’Emilio highlights an alternate dimension of this period in Rustin’s life. During his sentence, Rustin exchanged letters with his lover, Davis Platt. To ensure that Platt received the letters (and that they were not flagged or intercepted by prison authorities), Rustin referred to Platt as a woman in his writing, alternating between the pseudonyms “Marie” and “M.” According to D’Emilio, the coded letters do not indicate an investment in “discretion.” Rather, they reflect the great lengths Rustin and other gay men had to go to conceal their longings amid the criminalization of same-sex desire in the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 81 What appeared to be Rustin’s “self-effacement was, all along, an adaptation to the stigma of homosexuality, a concession to the dangers to which it made him, and the causes with which he was associated, susceptible,” D’Emilio argues.Footnote 82 In this way, he calls into dispute accounts of Rustin’s life-history that center on his stated commitments to “discipline” and “discretion.” Like Doris Baker, Levine and Anderson were apparently “fooled” by Rustin’s affectations. The coded letters and other such examples of dissemblance opened questions about how homophobia impacted Rustin’s life—and how it continues to impact the causes for which he stood.

The second wave of biographical accounts, then, considers the man and the “mask.” D’Emilio and his contemporaries set out to narrate the extent of Rustin’s sexual consciousness as well as his navigation of homophobia across his writings, habits, and issue positions. Note the shift in titular framing devices. Whereas the titles of the first two biographies reference an African American spiritual (Bayard Rustin: Troubles I’ve Seen) and the Civil Rights Movement (Bayard Rustin and the Civil Rights Movement), the second wave of accounts advances a series of titles that link Rustin to prominent figures and themes of gay/lesbian life. The stage-play “Civil Sex” by Brian Freeman “infers the collision between issues of sexuality and Civil Rights.”Footnote 83 The documentary Brother Outsider by Bennett Singer and Nancy Kates alludes to black lesbian poet Audre Lorde’s renowned 1984 essay collection Sister Outsider.Footnote 84 And Lost Prophet by D’Emilio calls to mind the landmark 1989 edited volume, Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past. Footnote 85 In this way, each declares at its outset that nothing “that went into [Rustin’s] total composition was unaffected by his sexuality.”Footnote 86

Figure 5. Photograph of a scene from “Civil Sex.” The scene depicts Bayard Rustin’s relationship with Davis Platt. The San Francisco Chronicle printed this photograph along with a review of the stage-play, titled “Unfinished Portrait of a Complicated Man/Rustin a Puzzle in ‘Civil Sex.’”a

D’Emilio, Freeman, Kates, and Singer shore up the significance of same-sex desire and homophobia in their respective projects by way of three shared representational strategies.Footnote 87 First, each considers Rustin’s romantic longings in detail. Whereas previous biographies only either allude to Rustin’s “personal” interests or discuss his desires in euphemistic, stigmatizing terms, these attend closely to Rustin’s pursuit of intimacy. For example, each account spotlights Rustin’s relationship with Davis Platt, noting Platt’s memory of how the two met and the closeness of their bond. Partially animating the choice to foreground Platt is the notion that his memory yields more insight into Rustin’s inner life than other historical data. That is, if Rustin “fooled” Doris Baker and others with his affectations—and if he occasionally coded his own writings to avoid scrutiny—perhaps it was in his romantic relationship with Platt that he removed the “mask” and revealed his truer intentions. Platt was hardly unaware of the importance of his recollection, in this regard. In fact, in an unpublished exchange with D’Emilio, Platt expressed his own longing to recover Rustin’s sexuality, and the two shared suspicions toward earlier biographical projects:

D’Emilio: [P]art of what draws me to [Rustin’s] life, aside from that fact that he was interested in all of the issues that I really care about, is that I suspect he was much more influential in making things happen than so far history has given him credit for. He hardly appears in the books about the [Civil Rights Movement]. And I may change my mind as I do more research, but I’m convinced that there’s a way in which his being gay shaped that …. [H]e had to devise a role for himself that kept him in the background, even as he was influential, so that other people didn’t see him … and then there were other people who saw him, but didn’t want to acknowledge what they were seeing precisely because he was gay.

Platt: I think you’re onto something terribly important, and this is something that Jervis [Anderson] can’t deal with.

D’Emilio: That’s what I suspect too, but I don’t know.Footnote 88

More than a “neutral” respondent, Platt was skeptical of how other historians would frame Rustin’s sexuality and affirmed D’Emilio’s intent to shore up its importance. Notably, as they draw attention to Platt, D’Emilio and his contemporaries dispense with the idea that Rustin was deeply tortured and self-denigrating. Such claims are subordinated to Platt’s insistence that Rustin was remarkably audacious: “I never had any sense at all that Bayard felt any shame or guilt about his homosexuality. And that was rare in those days [that is, the 1940’s]. Rare.”Footnote 89 Not undisciplined or “depraved,” Rustin is cast as a figure who displayed enviable sexual freedom—and perhaps even an inchoate, yet politically formative sense of sexual consciousness.

Figure 6. Bayard Rustin at the scene of a 1971 teachers’ union strike in Newark, New Jersey.a

Alongside portrayals of Rustin’s romantic longings in each account are depictions of the homophobic vitriol he faced. If previous biographies emphasize Rustin’s stated desire for self-discipline, these highlight the extent to which others sought to discipline Rustin—by way of publicizing his sexuality, questioning his capacity for moral judgment, and threatening the organizations with which he was associated. For example, Freeman’s “Civil Sex” opens with a reading from Strom Thurmond’s infamous 1963 Senate floor speech denigrating Rustin. The speech entails Thurmond’s use of Rustin’s arrest record to call into question the moral legitimacy of the March on Washington:

Distinguished gentlemen and gentle lady, I rise to call the attention of my colleagues to the presence of one article in the Washington Post on Sunday, August 11, 1963, by Susanna McBeen which attempts to whitewash the deplorable and disturbing record of the man tabbed as “Mr. March-on-Washington himself.”

…

The article states that he was convicted in 1953 in Pasadena, California, of a morals charge. The words “morals charge” are true. But this is a clear-cut case of toning down the charge. The conviction was sex perversion!Footnote 90

Thurmond goes on to say: “It is terrible for a man with such a record to be conducting the demonstration and in such close cooperation with officials of the Kennedy administration. If Rustin is ‘Mr. March-on-Washington himself,’ they ought to call the whole thing off.”Footnote 91 It is Rustin’s navigation of this quandary—pursuing political change and meaningful intimate relationships, under threat of public degradation and scrutiny—that serves as the plot line of Freeman’s account.

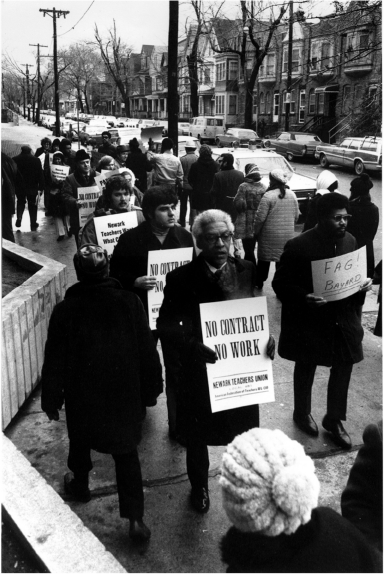

Brother Outsider by Kates and Singer offers what is perhaps the most striking depiction of the homophobia Rustin faced. Consider Figure 6, included in a segment of the film concerning Rustin’s relationship to black nationalism. The image features Rustin at the scene of a 1971 teachers’ union strike in Newark, New Jersey. As Rustin marched in support of the Newark Teachers’ Union, black nationalists advocating for “community control” staged a counter-protest, holding signs that read “Fag! Bayard” and “Rustin, Fag Go Home!”Footnote 92

Two years following this protest, moreover, Black New Ark, a local periodical, deemed Rustin its “Uncle Tom of the Month” for his continued attempts to broker relationships between labor unions and black communities:

This month’s dishonor goes to perhaps the most vulgar Tom of all times, “Madame Socrates,” [or] as “his” myriad white friends call “him,” Bayard Rustin. Rustin is organized labor’s black whore, who sings anything big labor wants “him” to, for “his” supper …. [T]his Kahaba [i.e., “prostitute” in Swahili], this puta [i.e., “whore” in Spanish], has shown “his” willingness to “break down like a shotgun” for the pigs of organized big capitalist labor …. So the Tom of the Month disgrace in matching Unisex models [goes] to whore-Bayard, the lowest thing we know of.Footnote 93

The unnamed editorialist draws on stigmatizing discourses of “sexual inversion” to degrade Rustin and criticize his support for labor unions. Maligned as a “sell out,” Rustin is accused of holding economic issue positions that reflect gender undecidability and sexual subordination, not sound political judgment. Expressions of homophobia like these are underscored to demonstrate more than the harshness of Rustin’s critics. As D’Emilio puts it, the attacks Rustin faced indicate how porous the “boundary between public and private” proved to be in his life and throughout mid-century social movements. Hardly a case of concealed passion, neatly “tucked into the corner marked ‘private life’”—Rustin’s sexuality was made violently public time and again, shaping debates over issue definition and political membership.Footnote 94

The third (and arguably most formative) representational strategy these biographical accounts share is a concluding reflection on the rise of gay/lesbian rights. Note the sharp difference here: the first biography of Rustin depicts the end of his life as the period in which he finally made a “firm decision about controlling his gay lifestyle”; the second emphasizes how limited Rustin’s involvement in gay politics was, insisting that there is “abundant evidence … that he [remained] ambivalent and conflicted about his own homosexuality.”Footnote 95 By contrast, D’Emilio, Freeman, Kates, and Singer highlight Rustin’s burgeoning interests in gay/lesbian political demands. For example, Brother Outsider ends with footage from the 1987 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. Appended to this footage is a video clip of Rustin diagnosing a shift in the horizon of rights discourse: “Twenty-five [or] thirty years ago, the barometer of human rights in the United States were black people. That is no longer true. The barometer for judging the character of people [with] regard to human rights is now those who consider themselves gay, homosexual, lesbian.”Footnote 96 Rustin’s claim (which reflected themes from his 1986 speech, “The New ‘Niggers’ are Gays”) suggested that gay men and lesbians had begun to replace African Americans at the bottom of the American political order.Footnote 97

Similarly, gesturing toward the potential impingement of gay/lesbian issues on Rustin personally, D’Emilio ends his account with a brief reflection on the legal vulnerability of Rustin’s relationship with Walter Naegle, his partner during the final decade of his life:

Settling into a committed relationship in his older age, [Rustin] had to confront the lack of formal recognition for his connection to Naegle. Same-sex marriage and domestic partnership had not yet become contested public issues, and the question of how to secure Naegle’s standing as his next of kin was a vexing one. Rustin’s death could leave Naegle homeless, since New York’s rent control laws did not recognize same-sex partners as family; it would also leave matters of inheritance open to challenge from family members of West Chester.Footnote 98

Though Rustin never commented on the issue directly, D’Emilio insists that the lack of formal recognition for same-sex relationships loomed over him in his final years. In this way, he frames Rustin’s limited options for legal protection as a pre-history of marriage equality.

The upshot of these three shared representational strategies—foregrounded details of Rustin’s romantic relationship with Platt; thick description of the homophobic vitriol he faced; and concluding reflections on gay/lesbian rights—is not just empirical revision but a revised “story” of civil rights. These accounts of Rustin disrupt the notion that gay men and lesbians had no relationship to the Civil Rights Movement. More than that, though, they articulate lines of historical continuity between the Movement and the emergence of gay/lesbian political demands. If gay/lesbian communities were, like African Americans, at the bottom of the American political order, the struggle for civil rights did not end. Rather, its locus shifted toward issues of sexuality. Unlike previous biographers, whose nostalgic reflections portray the Civil Rights Movement as an object of the past, D’Emilio, Freeman, Kates, and Singer depict the struggle for civil rights as ongoing and unfinished.Footnote 99

Gay/lesbian advocates took up (and in some cases anticipated) this “story” at the turn of the century, as they mobilized narratives about Rustin to contextualize their political ambitions. For example, in 1996, then-black lesbian activist Charlene Cothran partnered with the Human Rights Campaign to organize the annual “Bayard Rustin Rally,” an assembly of black gay men and lesbians in Atlanta, Georgia.Footnote 100 Discussing the significance of the rally during an interview, Cothran explained how historical representations of Rustin figured into ongoing debates over civil rights:

It’s very important, particularly here in the South … that the gay and lesbian movement be a part of the Civil Rights Movement. And, more specifically [it is important that] the African American gay and lesbian community take homage of [sic] Bayard Rustin—being an out, black gay man, back in the ‘40s. We need that as a positive role model to help break up the silence.Footnote 101

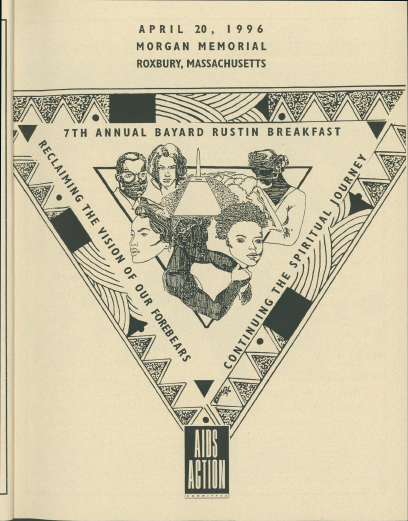

Shaped by Davis Platt’s insistence that Rustin displayed enviable sexual freedom, even in the 1940’s, Cothran’s account of Rustin’s identity is framed as a rallying cry for gay/lesbian advocates. Several years prior to Cothran founding the “Bayard Rustin Rally,” moreover, the AIDS Action Committee of Massachusetts established its annual “Bayard Rustin Breakfast.” During the event (which, like the rally Cothran founded, is still ongoing) community activists tie civil rights imagery to HIV/AIDS activism, as they reflect on Rustin’s enduring significance. For example, the following graphic, drawn from the program booklet of the 7th annual Rustin Breakfast, links the term “AIDS Action” to an image of the National Mall, the site of the 1963 March on Washington. The graphic thus suggests that the fight against HIV/AIDS extends the struggle for civil rights.Footnote 102

Figure 7. Graphic printed in the program booklet of the 7th Annual Bayard Rustin Breakfast, organized by the AIDS Action Committee of Massachusetts.a

If describing Rustin as “black and gay” was unthinkable in the immediate aftermath of his death, it became difficult to imagine him in any other terms amid the increased circulation of this revised “story.” From 1997 to 2013, political analysts and policy groups recurrently deployed representations of Rustin to scramble the boundaries of an ever-expanding array of issues—all framed in relation to the Civil Rights Movement. Some, for example, used narratives about Rustin in HIV/AIDS prevention projects, to link condom use to racial pride.Footnote 103 Others cited selections from his writings to illuminate ties between ostensibly unrelated policy areas, such as welfare reform and anti-bullying laws.Footnote 104 Still others mobilized portrayals of Rustin to criticize patterns of homophobia in African American politics and across the African continent.Footnote 105 Even the National Council of Black Political Scientists named its prize for the best paper on LGBT politics the “Bayard Rustin” award.Footnote 106

In the meantime, Jervis Anderson, the first person to author an account of Rustin’s life-history, died. His biography (Bayard Rustin: Troubles I’ve Seen) and Daniel Levine’s (Bayard Rustin and the Civil Rights Movement) both went out of print, rendering their depictions of Rustin less accessible. The “story” advanced through these accounts appeared increasingly antiquated—or, more pointedly, “conservative”—as public discourse on homosexuality shifted. For instance, in its 2003 Lawrence v. Texas decision, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the “right to privacy” and thus ruled sodomy laws unconstitutional. In 2012, Barack Obama became the first sitting president to express support for marriage equality. Amid these and other such developments, portraits of Rustin that foreground same-sex intimacy and homophobia supplanted accounts of his investment in “discipline”: the strategic value of the former grew, alongside the development of gay/lesbian rights, while the latter fell out of circulation.

6. Conclusion: In the shadow of Rustin

In August 2013—amid celebration of the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, and just 1 year after he expressed support for marriage equality—then-President Barack Obama named Bayard Rustin a posthumous recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the United States. During the award ceremony, Obama credited Rustin with helping to pioneer a movement that remains unfinished:

For decades, this great leader, often at Dr. King’s side, was denied his rightful place in history, because he was openly gay. No medal can change that. But today we honor Bayard Rustin’s memory by taking our place in his march towards true equality, no matter who we are or whom we love.Footnote 107

While raising Rustin’s biographical profile, Obama reified the notion that his life-history represents historical continuity between the Civil Rights Movement and contemporary gay/lesbian politics; the “ethically constitutive story” of his “march towards true equality” puportedly binds the former to the latter. The award ceremony spurred international interest in Rustin: U.S. Embassies in Iceland and Guyana, for example, held public screenings of Brother Outsider, followed by community discussions on race, “pride,” and LGBT rights.Footnote 108

Biographies of Bayard Rustin advance more than facts about him. Rather, as I have argued throughout this article, accounts of his life-history entail strategic choices and often yield normative conclusions. Biographical representations of Rustin have changed over time, in response to debates over the pursuit and proper locus of civil rights. If the first set of biographies addresses questions regarding “post–civil rights” protest strategy and political conduct, the second takes up disputes over issue definition and political membership. Shifting portrayals of Rustin thus illuminate the evolution of civil rights discourse between 1987 and 2013. In examining the production and reception of extant accounts of Rustin’s life-history, my aim has not been to expose historical inaccuracies or to prove any of them “wrong.” (On the contrary, I find each of the biographies discussed above revelatory, in one way or another.) What I have instead shown is how each portrayal of Rustin addresses a specific “context of argument.” Additionally, I have attempted to underscore the (often underappreciated) conceptual-political labor of narrative construction, while showcasing the incredible work that goes into the making of political categories that social scientists take for granted. To recognize Bayard Rustin as “black and gay” required years of purposive storytelling, not just “correct” empirical description.

Today, prevailing representations of Rustin obscure shifts in the construction of his iconography; animated by an insistence on “truth,” such representations suggest that there is one correct way to remember him. This has long been a part of the strategy behind framing Rustin as “black and gay”: if this narrative contains the “truth,” any other “story” about Rustin appears false—or, worse, whitewashed. However, as I have shown, the notion that Rustin was “black and gay” is not merely true; and, as I noted at the outset of this article, I am concerned that the political purchase of representing him in these terms has waned. Where depicting Rustin as “black and gay” once powerfully reshaped debates over issue definition and political membership, such depictions now serve only to de-specify political difference, while substituting symbolic representation for democratic engagement. For example, during her 2022 remarks to the Human Rights Campaign, Vice President Kamala Harris cited Bayard Rustin, Harvey Milk, and Sylvia Rivera as important models of patriotism.Footnote 109 The symbolic value of this comparison belies the fact that these figures—though all regarded as important actors in the history of LGBT politics—had widely varying political outlooks and precious little in common.Footnote 110

Notwithstanding the “wrongness” of Harris’s remarks, my concluding ambition is not to identify the absolute truth about Bayard Rustin. Countering hackneyed representations of him instead requires renewed attention to the conceptual-political stakes of how he is memorialized: What truth about Bayard Rustin is the “best truth for our time”? How might his life-history be retold to open new “conceptual space” and “enable a critical rethinking of the present”?Footnote 111 Specifically, how ought Bayard Rustin be “inherited” in a context defined by “elite capture” of identity politics?Footnote 112 I submit that reinvigorated accounts of his life must resist empirical flattening by reckoning with the “manifold history” of black politics, including the “scheme-exceeding complexity and specificity” of “black and gay” peoplehood.Footnote 113

As a final point of interpretive insight, then, consider the following exchange between Bayard Rustin and his would-be political heir Joseph Beam. A black gay activist based in Philadelphia in the late-twentieth century, Beam took great interest in Rustin’s life-history and the stakes of its telling. Drawing on Rustin’s “prestige and authority to promote his own cause,”Footnote 114 Beam authored the following “story” about Rustin in a 1986 article for Philadelphia Gay News:

At another time, on another continent, I might have gone to his hut to bask in the warmth of his fire and to listen to his words of wisdom as the elder in the village. [While] it is another day, and this is certainly another continent …. Bayard Rustin is no less than the wise man of the village of many centuries ago. Rustin was a Black Gay civil rights activist long before it was lucrative and legitimate, long before the rebellion at the Stonewall Inn in 1969, long before the tumultuous Black liberation struggles of the Sixties, long before the Brown v. Board Supreme Court decision in 1954. Bayard Rustin was a Black Gay civil rights activist when Blacks were forced to ride in the rear of the bus, when “colored” bathrooms and water fountains were commonplace. Bayard Rustin was a Black Gay civil rights activist at a time when the bodies of Black men hung from the trees and were found at the roadside.Footnote 115

Not only does Beam suggest that Rustin’s life prefigures his own; he mythologizes his relationship with Rustin and poses it as a reflection of a long, undifferentiated history of “black and gay” people involved in the struggle for civil rights. Thus, Rustin is made to represent continuity between issues and events that may, to some, appear unrelated—like, for example, lynching and the Stonewall Riots.

Beam sent the magazine feature to Rustin and later invited him to be a part of In the Life, the first published anthology of black gay writings.Footnote 116 However, after reading the feature, Rustin declined Beam’s invitation:

Dear Mr. Beam:

…

After much thought I have decided that I must decline your invitation to contribute to your collection of oral histories of black gay men. I feel it only fair, however, to give you my reasons for doing so.

My activism did not spring from my being gay, or for that matter, from my being black. Rather it is rooted, fundamentally, in my Quaker upbringing and the values that were instilled in me by my grandparents who reared me. Those values are based on the concept of a single human family and the belief that all members of that family are equal. Adhering to those values has meant taking a stand against injustice, to the best of my ability, whenever and wherever it occurs.

The racial injustice that was present in this country during my youth was a challenge to my belief in the oneness of the human family. It demanded my involvement in the struggle to achieve interracial democracy, but it is very likely that I would have been involved had I been a white person with the same philosophy.

I was not involved in the struggle for gay rights as a youth. To the best of my knowledge there was no organized gay liberation movement. I did not ‘come out of the closet’ voluntarily – circumstances forced me out. While I have no problem with being publicly identified as homosexual, it would be dishonest of me to present myself as one who was in the forefront of the struggle for gay rights. The credit for that belongs to others. They are the ones who should be in your book.Footnote 117

The declined invitation—a rare moment in which a pioneering figure is still alive to scrutinize the naming of his legacy—is doubly instructive. First, it signals disjuncture between Beam and Rustin. Whereas Beam portrays Rustin as “black and gay” avant la lettre, Rustin insists that Beam’s political projects are different from his own, despite their apparent descriptive similarities. Importantly, Rustin does not merely dismiss Beam, nor does he denounce Beam’s interests. Rather, he presciently suggests that his establishment as the forefather of “black and gay” peoplehood would serve only to occlude Beam’s pursuits. Analysts of black political history ought to take cues from this declined invitation. Instead of working to recover Bayard Rustin’s singular authority from the shadow of the Civil Rights Movement, one might investigate the collective ambitions and political disputes that unfold in the shadow of Bayard Rustin.