Background: dementia as the problem

For over two decades it has been argued that dementia is not a disease, nor even a condition (Derouesné, Reference Derouesné2003). Instead, dementia is a syndrome – a variable collection of symptoms. It is a diachronic phenomenon, in that the language and concepts used to describe it evolve over time. One reason that dementia cannot be defined precisely is that it has been subject to subtly changing psychiatric, biomedical and socio-cultural stories (Zeilig, Reference Zeilig2013). Its shifting nature and complexity have unpicked any consensus about what the syndrome is, in neurological terms. Dementia is now conceptually ‘slippery’ (Zeilig, Reference Zeilig2013), although a view of it as a long-term disability is gaining hold (Zeilig, Reference Zeilig2015). As Hillman and Latimer (Reference Hillman and Latimer2017) put it, dementia represents ‘an increasingly wide compendium descriptor for many different effects’. Put another way, our expanded understandings of dementia are destabilising it as a taken-for-granted category (Kontos and Martin, Reference Kontos and Martin2013).

The lack of clarity about what dementia is can prompt feelings of dread that are typical of a medical problem that is unclear in its causality and for which treatments are ineffective (Sontag, Reference Sontag1978). Discourse about dementia reinforces the dread (Zeilig, Reference Zeilig2015); dementia is an ‘epidemic’, a ‘crisis’ or a ‘plague’ that is a ‘burden’ on families, carers and wider society and that exacts a high price from those who experience it. In terms of prognosis dementia can be a ‘primeval monster’ or a ‘time bomb’. There is a paradox here, in that dementia is perceived as an active, progressive and lethal disease that renders its ‘victims’ passive and inert, in a kind of living death. Dementia as a term conveys an insidious destructive power associated with loss of control and dignity. It strikes at the core precepts of contemporary culture, including identity, value, autonomy, freedom and meaning (Chapman, Phillip and Komesaroff, Reference Chapman, Phillip and Komesaroff2019).

Peel (Reference Peel2014) argues that there are two dominant discursive representations of dementia. One is the catastrophising discourse referred to above that frames dementia as social death and people with dementia as liminal beings – in transition from life to death. Underpinning this is a biomedical ideology that asserts the difference between dementia and normal ageing. The second is an individualistic discourse that includes a focus on ‘living well’ with dementia and growing scientific and policy interest in (potentially preventable) vascular disease as a contributor to dementia. Peel notes a potentially victim-blaming turn in this individualistic discourse.

Fletcher (Reference Fletcher2020) argues that it is necessary to understand the institutional representations of dementia that stem primarily from the biomedical research community. He characterises these representations as ‘mythical dementia’, a broad array of neuropathological processes, distinct from ageing, that cause cognitive decline. Mythical dementia is principally the domain of biomedical research, although it also permeates the activities of dementia-related charities, government policy and media portrayals of dementia. He terms this representation ‘mythical dementia’ because, while there is likely some foundational element of truth in the biomedical model, the powerful story built upon that foundation is largely conjectural and metaphorical (for now at least). While scientific efforts to solidify an externally valid dementia have so far proved unsuccessful, this has not prevented the proliferation of mythical dementia.

Growing interest in dementia among politicians, scientists, practitioners and the ageing public has promoted a cultural pre-occupation with loss of memory (Hillman and Latimer, Reference Hillman and Latimer2017) and for a ‘crusade’ to counter dementia (Zeilig, Reference Zeilig2015), and, in England more recently, a ‘mission’ (Office of the Prime Minister, 2022). It is not clear how such a crusade or mission can capture the complexity of the problem of dementia. After all, meanings of dementia are interpreted, embodied or resisted by people in their social contexts and these processes are shaped according to their social location (gender, social class and ethnicity) and individual biography (Hillman and Latimer, Reference Hillman and Latimer2017). As Parker et al. (Reference Parker, Cutler and Heaslip2021) have also argued, dementia as Zeitgeist has captured imaginations, mainly in the Global North, but is culturally contingent and possibly temporary. Its recent inclusion in England’s Major Conditions Strategy (Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), 2023) may be illustrative of this shift with its policy departure from the previous specific National Dementia Strategy (DH, 2009).

Until recently people with dementia were subaltern figures in nursing and medical discourses, but a focus on personhood and citizenship has created possibilities for developing transformative models of care and dementia voice. Personhood centralises the person with dementia in social networks, whilst citizenship challenges discrimination and stigma. Emerging novel responses to dementia allow a theoretical rejoinder to the limitations of scientific discourses (Chapman, et al., Reference Chapman, Phillip and Komesaroff2019). Dementia has become an historically burdened term and the medical use of the term dementia may have had its time (Gilmour and Brannelly, Reference Gilmour and Brannelly2010) as seen in moves to referring to it as a Neurocognitive Disorder (NCD) in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5, Regier et al., Reference Regier, Kuhl and Kupfer2013). A new paradigm may be needed to enfold the biomedical model into a broader social perspective continuing but also critiquing the seminal work of Kitwood on personhood (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Philip and Komesaroff2022).

One particular question remains un-answered; how do different meanings of dementia gain traction over others? This paper considers the claims being made for dementia as a medical problem that is open to medical and scientific interventions. It explores these interventions through an analysis based on Carol Bacchi’s ‘representation of problems’ framework, often referred to as What is the Problem Represented to be? (WPR) (Bacchi, Reference Bacchi2009, Reference Bacchi2012).

What is the problem represented to be?

The WPR approach is a resource, or tool, grounded in a Foucauldian understanding of governmentality (Foucault, Reference Foucault, Burchel, Gordon and Miller1991) intended to facilitate critical interrogation of public policies (Bacchi, Reference Bacchi2012). Bacchi’s approach has been used internationally to explore policy through considerations of power, social change and governance (Bacchi, Reference Bacchi2021). It starts from the premise that what we propose to do about something reveals what we think is problematic and should be changed. Following this thinking, policies contain implicit representations of what is considered the problem (‘problem representations’). The task in a WPR analysis is to subject this problem representation to critical scrutiny by working through a set of six questions, shown in Box 1 (Bacchi, Reference Bacchi2021).

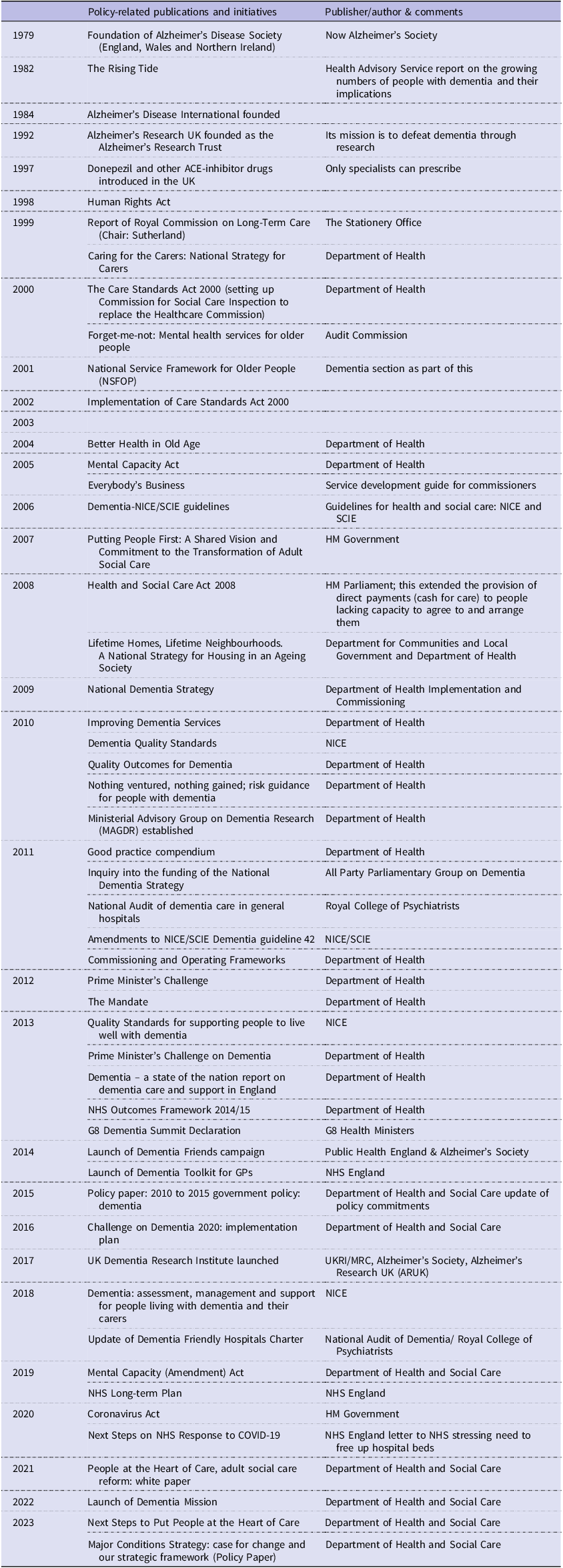

We have drawn on our own engagement with dementia research and policy developments with the Alzheimer’s Society, the UK Dementia Research Network (DENDRoN), the Dementia Research Institute, and with England’s National Dementia Strategy, its Dementia Mission and Major Conditions Strategy to answer these questions. Box 2 summarises the main policies and publications related to the emergence of dementia as a problem in England that informed our analysis. Systematic interrogation of policy documents was not attempted but could be the next step in applying Bacchi’s methods to the definition of dementia.

Box 1. Bacchi’s questions

-

1) What is the problem represented to be?

-

2) What presuppositions or assumptions underlie this representation of the problem?

-

3) How has this representation of the problem come about?

-

4) What is left unproblematic in this problem representation? Where are the silences? Can the ‘problem’ be thought about differently?

-

5) What effects are produced by this representation of the problem?

-

6) How/where is this representation of the ‘problem’ produced, disseminated and defended? How could it be questioned, disrupted and replaced?

Box 2. Dementia policy timeline in England

Sources: (1) Broad overview of government policy guidance with regards to dementia care in England; 2001–2013, Dementia Action Alliance, Greater Manchester West NHS 2013; (2) Policy paper 2010 to 2015 government policy: dementia May 2015 (Department of Health and Social Care, 2015); (3) Briefing 14/5/21 paper 07007 Dementia: Policy, Services and Statistics. House of Commons Library.

Note: England’s Department of Health became Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) in 2018.

The WPR approach is intended to be used as a mode of critical engagement, rather than as a formula. Question 1 assists in clarifying the implicit problem representation within a specific policy. Subsequent questions encourage reflection on the assumptions underlying this representation of the ‘problem’ (Question 2) and the practices and processes through which this understanding of the ‘problem’ has emerged (Question 3). Careful scrutiny of possible gaps or limitations in this problem representation allows imagining of potential alternatives (Question 4). Question 5 asks how identified problem representations frame what can be talked about legitimately (that is, what is relevant), shape people’s understandings of themselves and their problems, and impact materially on people’s lives. Question 6 sharpens awareness of the contested environment surrounding the representation of problems.

Essentially this approach suggests that policies are not best efforts to solve problems, but instead produce ‘problems’ with particular meanings that affect what gets done or not, and how people live their lives. The aim is to understand policy options better than many policy makers do, by probing the unexamined assumptions and deep-seated conceptual logic within implicit problem representations (Bacchi, Reference Bacchi2012). In an era when problem-solving is a near-hegemonic solution, expressed in evidence-based policy and contemporary promotion of researchers and students as ‘problem solvers’, the WPR approach challenges the assumption that ‘problems’ are uncontroversial starting points for policy development (Bacchi, Reference Bacchi2012). This approach may be particularly relevant to the present when increasing amounts of public and charitable funds are being allocated to ‘tackling’ the problem of dementia. This timeliness is also important as the risk of not defining the problem at the outset can lead to a Type III error (Kaur and Stoltzfus, Reference Kaur and Stoltzfus2017): the probability of solving the wrong problem. Archibald (Reference Archibald2020) advocates the WPR approach as a useful tool to focus evaluative thinking on the frequently tacit step of problem definition in programme planning. In Archibald’s view, “WPR can help evaluators apply a critical lens in their work, one that is both culturally responsive and more generally sensitive to the power/knowledge nexus in problem definition and solution evaluation” (Ibid. page 16).

Analyses

The knowledge base necessary for WPR analysis can come from experts in the field or from wider data sources. For example, De Kock (Reference De Kock2020) used a systematic literature review to identify a body of knowledge about a specific problem (cultural competence related to substance misuse). For this discussion paper we separately addressed Bacchi’s six questions taking dementia policy as the problem and discussed our answers to achieve consensus. Both of us have been involved in debates around dementia policy and practice in England at national as well as local levels since 1997 and were able to draw on our experiences of dementia policy making and service developments including those contained in Box 2 as researchers, professional educators and contributors to their consultations and implementation.

-

1. What is the problem represented to be? – policy and practice

With global ageing more people will develop dementia and some will require expensive and extensive support. Much policy has evolved in response to the projected scale of the problem. The ambitions of the first English National Dementia Strategy (Department of Health (DH), 2009) were to raise awareness of dementia; facilitate early investigation, diagnosis, and treatment; and improve services for people with dementia and their families. In England, investigation, diagnosis and some elements of post-diagnostic support are carried out by publicly funded NHS Memory Clinics. However, the political drive to screen for early-stage dementia was not evidence based and overlooked the possible harms of diagnosis (Le Couture et al., Reference Le Couture, Doust, Creasy and Brayne2013). The word ‘early’ was later replaced by ‘timely’ in acknowledgement of this (Burns and Buckman, Reference Burns and Buckman2013).

Such policy developments reflect the framing of dementia as a population catastrophe and an individual tragedy (Reed et al., Reference Reed, Carson and Gibb2017). The tragedy discourse has become increasingly incompatible with person-centredness and individual experience so provoking an opposite emphasis on ‘living well with dementia’ – the sub-title of England’s National Dementia Strategy (DH, 2009). Resolving this contradiction – tragedy or living well – requires a nuanced understanding of a paradoxical condition (McParland et al., Reference McParland, Kelly and Innes2017).

Much emphasis is placed on the wearing effects of caring on carers, but the experience of caring is more complex than words like ‘burden’ or ‘tragedy’ might suggest. The benefits of caring are more muted but can be expressed as job or role satisfaction, continued reciprocity and mutual affection, companionship and fulfilment of duty (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Schneider, Banerjee and Mann1999) underpinned by beliefs that families are the right and proper providers of care for their kin (Sanders, Reference Sanders2005). Indeed, the need for dedicated support for carers is emphasised in policies such as national carers’ strategies (Steenfelt et al., 2021).

-

2. What presuppositions or assumptions underlie this representation of the problem?

The primary assumption is that dementia is a medical problem like any other, and that earlier recognition will allow use of medication to at least ameliorate symptoms. The secondary assumption is that existing primary healthcare services, especially general practice (family medicine), are incapable of recognising and responding adequately to dementia syndrome, and that specialist expertise is essential if timely recognition is to be achieved. These assumptions rest on understandings of ‘the problem’.

Primary assumption: a medical problem like any other. Underlying this first assumption are problems with scientific knowledge and policy making.

The first knowledge problem is that basic science’s focus on pathological processes in dementia. For over twenty years the dominant hypothesis could be summed up as ‘one protein, one drug, one disease’ (Mangialasche et al., Reference Mangialasche, Solomon, Winblad, Mecocci and Kivipelto2010). Taking this understanding, dementia is caused by deposition of toxic proteins (beta-amyloid) that spill out in the brain in an ‘amyloid cascade’. Subsequent research aimed at ‘clearing’ beta-amyloid from the brain has failed to yield benefits (Karran and De Strooper, Reference Karran and De Strooper2016, Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Ashoor, Soobiah, Rios, Veroniki, Hamid, Ivory, Khan, Yazdi, Ghassemi, Blondal, Ho, Ng, Hemmelgarn, Majumdar, Perrier and Straus2018, Huang et al., Reference Huang, Shen and Zhao2019).

Representing the problem in this way explains both the focus on pharmacological treatment and policy investment in this area of research and commitments to substantial further funding, such as the Dementia Mission (Samarasekera, Reference Samarasekera2022). Policy making can point to the multiple initiatives in this area, often described as promising. For example, the pharmaceutical company Roche (2022) that had been running clinical trials of a new drug Gantenerumab on Alzheimer’s variant of dementia but was not able to show that it had slowed clinical decline. Another earlier trial aimed to find a medicine (Donanemab) that could slow the Alzheimer’s variant’s progression (Mintun et al., Reference Mintun, Lo, Evans, Wessels, Ardayfio, Andersen, Shcherbinin and Skovronsky2021). In 2021 the drug aducanumab was approved by the US drug regulatory body, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), for use in treating early Alzheimer’s variant (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Merrick, Milne and Brayne2021). However, it was later refused approval by the European Medicines Agency on the basis that the main clinical studies were conflicting and did not show overall effectiveness (Wilson, Reference Wilson2022).

What we call dementia is also framed as a far more heterogenous state determined by multiple factors and mechanisms that interact and intervene throughout life (Van der Linden and Van der Linden, Reference Van der Linden and Van der Linden2018). Or, put differently, it is made up of several different, slowly evolving disorders sharing a final common endpoint – the amyloid cascade (Sigurdsson, Reference Sigurdsson2010). Galvin (Reference Galvin2017), for example, maintains that among the many modifiable risk factors for dementia many do not seem to exert effects through amyloid. There appear to be multiple pathways to developing dementia, and there are likely multiple pathways to preventing it, and therefore a range of policy choices.

Secondly there is a wider crisis in biomedicine, which has assumed that a:

…combination of ever-deeper knowledge of subcellular biology, coupled with information technology, will lead to transformative improvements in health care and human health . . . this approach has largely failed (Joyner et al., Reference Joyner, Paneth and Ioannidis2016).

From a clinical perspective, such promissory medicine proposes:

…that all diseases [are] things to be conquered … that medical advances are essentially unlimited … that none of the major lethal diseases is in theory incurable; and that progress is economically affordable if well managed. (Callahan and Nuland, Reference Callahan and Nuland2011)

Healthcare systems built to deliver promissory medicine have become, by necessity, more complex, more impersonal, and more technology focused (Chochinov, Reference Chochinov2013).

The problem facing policymakers is how to make judgments on investing in ‘cure’ or ‘care’ when the electorate strongly favours cure research, often encouraged by media promotion of promising drug developments (Manthorpe and Iliffe, Reference Manthorpe and Iliffe2016). In the COVID-19 context, clinical and scientific researchers maintained their call for more funding: ‘The pandemic will pass. Dementia will remain. This is not a problem we can wait to solve’ (Lalli et al., Reference Lalli, Rossor, Rowe and De Strooper2021).

The secondary assumption; specialist expertise is essential. Early in the twenty-first century the National Health Service (NHS) in England was deemed unable (from the medical perspective) to identify dementia early enough. To correct this problem a network of NHS Memory Clinics was established to confirm dementia diagnoses and organise support and follow-up. However, Greaves and Jolley (Reference Greaves and Jolley2010) argue that England’s initial National Dementia Strategy (DH, 2009) was overly critical of existing services yet overly confident about the benefits of specialist attention. Although there were specialist community services for older people with mental health problems, including dementia (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Prince, Albanese, Banerjee, Dhanasiri, Fernandez, Ferri, McCrone, Snell and Stewart2007), England’s National Dementia Strategy declared that awareness of, and services for, dementia were among the poorest in the developed world. As Greaves and Jolley observe, this assertion rested on a limited survey sponsored by the pharmaceutical company Pfizer (Bond et al., Reference Bond, Stave, Sganga, O'Connell and Stanley2005), a manufacturer of symptom-modifying anti-dementia drugs (the cholinesterase inhibitors), and a European study drawing on marketing data of cholinesterase inhibitors’ sales (Waldemar et al., Reference Waldemar, Phung, Burns, Georges, Ronholt Hansen, Iliffe, Marking, Rikkert, Selmes, Stoppe and Sartorius2007).

There is much more to dementia care than the prescription of cholinesterase inhibitor medication (Audit Commission, 2000; Manthorpe and Moniz-Cook, Reference Manthorpe and Moniz-Cook2020), yet their prescription rate was used as the sole evidence of existing services’ inadequacy. Indeed when this treatment was offered, 50 per cent of patients stopped using cholinesterase inhibitors within six months (Lyle et al., Reference Lyle, Grizzell, Willmott, Benbow, Clark and Jolley2008, Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Willis, Matthews, Contell, Chan and Murray2007). Cholinesterase inhibitors and the related drug Memantine may seem effective for some individuals, but their overall health benefits appear negligible at a population level (Lin et al., Reference Lin, O’Connor, Rossom, Perdue and Eckstrom2013). There is evidence of no effect of these medications in early stages of dementia (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Ashoor, Soobiah, Rios, Veroniki, Hamid, Ivory, Khan, Yazdi, Ghassemi, Blondal, Ho, Ng, Hemmelgarn, Majumdar, Perrier and Straus2018). Attempts to find clinically meaningful effects have found so little evidence to reassure prescribers and funders that cholinesterase inhibitors really do much for most people with Alzheimer’s variant of dementia that they were de-prescribed by the French government (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Merrick, Milne and Brayne2021).

England’s National Dementia Strategy (DH, 2009) also argued that better information for the general population would promote an appreciation of the benefits of early diagnosis and reduce the societal problems of stigma, social exclusion and discrimination. These conclusions were not based on empirical evidence or even theories of change, and some expressed concern that the pursuit of early diagnosis risked increasing the misidentification of cases, potentially causing undue alarm and unnecessary interventions (Forlenza et al., Reference Forlenza, Diniz and Gattaz2010).

People living with dementia develop needs for care and support generally provided by family and later from carers or care workers. However, the affirmation ‘diagnosis is the gateway for care’ (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Prince, Albanese, Banerjee, Dhanasiri, Fernandez, Ferri, McCrone, Snell and Stewart2007) is misleading. Much support has always been given naturally in response to functional needs, by family, friends and community services (Eagles et al., Reference Eagles, Beattie, Blackwood, Restall and Ashcroft1987). Families or individuals may feel something is gained when the condition is named; but what will it mean for their future? The natural history of dementia differs widely (Holmes and Lovestone, Reference Holmes and Lovestone2003). Professional psychosocial interventions can be valuable, but if given too early may exacerbate support needs or increase carer anxiety (Manthorpe and Moniz-Cook, Reference Manthorpe and Moniz-Cook2020). For many people, for much of the time, there will be little advantage in altering the main elements of care they were receiving pre-diagnosis (Greaves and Jolley, Reference Greaves and Jolley2010).

Given the uncertainties about the medical model of dementia it may be more useful, therefore, to frame the problem of dementia as a disorder that unfolds over the life course, shaped by accumulative exposures to harmful (but also to protective) factors. We return to this later in this paper.

-

3. How has this representation of the problem come about?

Our analysis suggests that dementia is framed by lobbying of politicians by charitable organisations and advocacy groups working in a coalition with scientists and clinicians. Such a coalition may reduce the slipperiness of dementia as a concept, without fully embracing the representation of dementia as a mythical or homogeneous entity largely based on a broad array of discrete conditions (Fletcher, Reference Fletcher2020). Those affected by dementia can, under certain circumstances, also become individuals who live well with dementia, and others who can think about and practice prevention of dementia, within supportive environments. The dynamics of dementia representation need clarification by a more systematic interrogation of how policy is developed and applied, probably on a case-by-case basis.

-

4. What is left unproblematic in this problem representation? Where are the silences? Can the ‘problem’ be thought about differently?

Dementia is a syndrome whose underlying pathologies are poorly understood. However, the limitations of neurology-based dementia research are glossed over whilst there is too little social science research (Academy of Social Science Research, 2016). For example, in randomised controlled trials of treatments for Alzheimer’s disease conducted over a decade up to 2017, behavioural and psychological symptoms, widely recognised as the most stressful and distressing manifestations of dementia, were the primary outcome measures of choice in only one in five studies (Canevelli et al., Reference Canevelli, Cesari, Lucchini, Valletta, Sabino, Lacorte, Vanacore and Bruno2017). While there are growing numbers of active communities of people living with dementia in the UK, such as DEEP (the UK network of dementia voices – https://www.dementiavoices.org.uk/), the voices of those with lived experience especially in relation to behavioural and psychological symptoms and living in care homes, and those who are more widely socially excluded, are relatively silent. Chapman et al. (Reference Chapman, Philip and Komesaroff2022) further suggest that attempts at repair work (the efforts to adapt to their present) by people with dementia ‘may not reliably conform to expectations and these attempts are at risk of remaining unheard and unacknowledged’.

Alternative perspectives may frame dementia syndrome as a disability (the gap between environmental demand and personal capability) (Manthorpe and Iliffe, Reference Manthorpe and Iliffe2016), understand the epidemiology of cognitive impairment and the clustering of dementia with other conditions, and appreciate the conceptualisation of brain protection in terms of a ‘cognitive footprint’ of risks (Rossor and Knapp, Reference Rossor and Knapp2015).

Epidemiological evidence about the origins of dementia syndrome gives other clues about what to do with the ‘problem’, since preventive activities against heart disease appear to protect the brain (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Huntley, Sommerlad, Ames, Ballard, Banerjee, Brayne, Burns, Cohen-Mansfield, Cooper, Costafreda, Dias, Fox, Gitlin, Howard, Kales, Kivimaki, Larson, Ogunniyi, Ortega, Ritchie, Rockwood, Sampson, Samus, Schenider, Selbaek, Teri and Mukadam2020). Dementia syndrome and its sub-types seem to arise through the accumulation of harms over the life course, and cluster with other endemic conditions that exacerbate each other synergistically, making ‘syndemic’ disorders (Singer et al., Reference Singer, Bulled, Ostrach and Mendenhall2017).

Although the public health evidence may still not be strong enough to support a public health campaign (Sohn, Reference Sohn2018) to encourage people to make lifestyle changes for the benefit of brain health, protective factors are becoming more salient. The mechanisms that link lifestyle change to neuronal protection are emerging. A research agenda based on a life-cycle model of chronic stress that integrates genetic, brain chemistry and personality factors could potentially enhance our understanding of dementia and open up possible prevention strategies and targeted interventions (Moniz-Cook et al., Reference Moniz-Cook, Vernooij-Dassen, Woods, Orrell and Network2011). Exploratory longitudinal studies are needed to lay the basis for such biopsychosocial research; a problem for policymakers is that they could need funding on a scale comparable to that of the drug trials conducted over the last two decades.

-

5. What effects are produced by this representation of the problem?

Too much emphasis on biomedical research and too little on social science research could be hampering efforts to enhance the health of an ageing population. An over-reliance on common-sense thinking (for example, that early recognition is intrinsically good) can undermine improvements in the prevention of illness and in service delivery (Campaign for Social Science, 2017). For example, there can be resistance to promoting multi-disciplinary rehabilitation for people with dementia because ‘recovery’ – once the rationale for rehabilitation – is deemed an impossible goal for people with dementia, even though optimising independence or autonomy is also an aim of rehabilitation (Cations et al., Reference Cations, Laver, Crotty and Cameron2018).

-

6. How/where is this representation of the ‘problem’ produced, disseminated and defended? How could it be questioned, disrupted and replaced?

The representation of the problem is produced, disseminated and defended by a coalition of interests.

Such a coalition can create the problems of overuse and fragmentation of services, overemphasis on technology, and ‘cream-skimming’, and it may also exercise undue influence on national health policy. Skeptical observers (such as George and Whitehouse, Reference George and Whitehouse2014) add to this list the failure of massive scientific investment to do more than expose the syndromal, age-related aspects of dementia, and propel cognitively impaired older people into ‘a rhetorical battlefield where medical triumphalism promotes exaggerated hope’.

This means that large-scale changes in research efforts – for example, developing a new paradigm that enfolds the biomedical model into a broader social perspective – would need concerted pressure from inside and outside the coalition.

New and existing representations of dementia could be examined in scientific and civil society forums, and their mechanisms be made explicit. This public scrutiny and debate could help clarify why some dementia representations gain traction over others.

In the medium term, since prevention is likely to be more valuable than treatment (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Fratiglioni, Matthews, Lobo, Breteler, Skoog and Brayne2015), public health approaches to dementia involving long-term, low-level activities are in our view likely to yield more benefit than much of the current clinic-based activity. Practical, public health examples of secondary and tertiary prevention now include dementia support workers, who reduce environmental demands at individual level (for individual and families), and dementia-friendly communities, which reduce environmental demand at a social level (see Hebert and Scales, Reference Hebert and Scales2019).

Conclusions

In our view, the six WPR questions help elucidate the representation of dementia within medical and social care. The dominant perception of the problem of dementia in the Global North is that it is a biomedical threat that must be averted, and a tragedy for the individual that must be mitigated. Dementia is framed as a disease with at least a partly known pathology, to be managed systematically, even though there is little evidence that disease status is appropriate to most people living with dementia and that clinic-based management is effective. The biomedical model is a poor fit with the condition. Limitations of dementia research are glossed over, and resources are diverted from the needs of people with troublesome dementia symptoms towards memory clinics and drug testing. This perspective may not be transferable to other cultures where civil society differs in the influence of its charitable sector.

The WPR analysis outlined in this paper drew upon our long experience in dementia research and services and is necessarily English focussed and constructed. Adapting De Kock’s (Reference De Kock2020) systematic review of literature that reflects the WPR approach might well yield different answers from our selective review, but we doubt that this matters because the WPR approach is not meant to be formulaic or definitive, and different answers enrich policy debates. The WPR analytic approach helps see why prevention gets overlooked and reminds us that not all ‘stakeholders’ are the same or have the same motivations. It explains the enduring focus on the label of dementia rather than on dementia’s disabilities, accounts for why the focus is on cure not care, offers insight into power relationships within medicine and science, and enlarges the frame of the policy problem. If we could explain why different dementia models gain traction over others, the WPR approach could potentially be used to construct an agenda for change in dementia research and care.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a presentation prepared for the Karlstad University International Symposium on Critical Policy Studies – Exploring the Premises and Politics of Carol Bacchi’s WPR Approach, August 2022. The views expressed in this paper are the authors’ alone and should not be interpreted as those of the National Institute for Health and Care Research, the NHS, or the Department of Health and Social Care and its Arm’s Length Bodies.