Introduction

In March 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s report found that unless carbon emissions peaked by 2025 and reduced by 43 per cent by 2030, it would be impossible to avoid the human, social, financial and environmental catastrophe caused by global temperature rises of more than one point five degrees (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2022). In the UK, the transition to a ‘net zero economy’ – meaning an economy that has reduced its net carbon emissions to zero – is regarded as an essential contribution to addressing climate change (Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, 2021a). The term ‘Net Zero’ (NZ) has become shorthand for the policies associated with this transition.

Visions of life under NZ in the United Kingdom (UK) have been produced by policy, grassroots and academic actors (BEIS, 2021a; Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions et al., Reference Pye, Betts-Davies, Eyre, Broad, Price, Norman, Anable, Bennett, Brand, Carr-Whitworth, Marsden, Oreszczyn, Giesekam, Garvey, Ruyssevelt and Scott2021; Climate Assembly UK, 2020; Climate Change Committee, 2021, 2020a, 2020b). These visions are largely consistent in their evocation of a NZ world: foreseeing changes across many aspects of everyday life, over a relatively short but shifting time period. From the household or community perspective, this will likely be experienced as an enormous, challenging and transformative endeavour. Politically, a transition to NZ will lead to trade-offs between social, economic and environmental objectives, which will be difficult to meet concurrently (Gillard et al., Reference Gillard, Snell and Bevan2017; Hussein et al., Reference Hussein, Hertel and Golub2013; Robinson and Shine, Reference Robinson and Shine2018). As a result, substantial concerns have been raised about the potential for the transition to NZ to disproportionately impact those already experiencing disadvantages (Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR), 2018; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), 2020; United Nations Research Institute for Social Development and University of London Institute in Paris (UNRISD and ULIP), 2018). The concept of a ‘just transition’ is used to articulate which factors might shape households and communities’ capacity for change, and to explore the potential for mitigating the risk of unequal outcomes from the NZ transition. Users of the concept recognise the importance of balancing environmental, economic, and social objectives to ensure that policy changes do not harm the most vulnerable in society (Evans and Phelan, Reference Evans and Phelan2016; International Labour Organisation, 2015; IPPR, 2019; Snell, Reference Snell2022; UNFCCC, 2020).

Despite the urgent need for action, and the emphasis on a ‘just transition’ in the international climate agreements, there remain significant gaps in knowledge and thinking. The relatively atomised nature of both research and policy, and limited efforts to understand the effects of the transition on everyday life as a whole, is the first significant gap in knowledge that we seek to address here. For instance, the just transition is sometimes framed narrowly around employment and the impacts on communities reliant on carbon intensive industries (e.g. UNFCCC 2020). There is a growing literature that broadens this focus, addressing injustices associated with other areas of NZ policy. This includes work on energy poverty, inequalities in mobility, and food and leisure under NZ. Critically, most of this work deals with just one aspect of everyday life at a time (e.g. housing, transport), with the exception of recent work looking across energy and transport poverty (Simcock et al., Reference Simcock, Jenkins, Lacey-Barnacle, Martiskainen, Mattioli and Hopkins2021; Sovacool et al., Reference Sovacool, Kester, Noel and de Rubens2019). We argue that this gap runs the risk of knock-on effects and unintended consequences coming into play: with negative impacts produced by the sequencing of change, or the effect of changes in one area of life on another.

The second key gap in thinking that concerns us is the associated failure to integrate justice concerns into policy processes associated with NZ. It is likely that people, households and communities differ in their abilities to engage with policies and interventions based on their gender, social class, housing tenure, family structure, ethnicity/migration background, and disability, among others. Yet much of the policy and academic discussion around NZ fails to address differences in people’s ability to take part in a just transition. Visions of NZ tend to be concerned with painting a universal picture of future life, without taking present day diversity of experience into account. While issues such as energy poverty are recognised in visions of NZ they remain narrow in scope. The new fields of Eco-Social Policy and Sustainable Welfare in social policy have begun to correct these flaws. However, these fields are often theoretical in nature and would benefit from greater empirical exploration (Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022).

In this article we address these gaps in knowledge, reframing the just transition debate to put people and their everyday lives at its centre. In doing so we understand how NZ will affect people’s lives as a whole, as well as recognising that existing social arrangements, inequalities, and injustices will shape how people will experience these complex, multi-layered policy changes. We propose an analytical framework to identify the risks of exclusion under envisaged transitions to NZ. We hope that researchers and policy makers can use this framework to identify who is most at risk of exclusion during the transition, and design policy to reduce exclusion.

This article is part of a bigger research project that considered the risks of widening inequalities associated with the transition to NZ. We report here on conceptual thinking that we have engaged in as part of the project, in response to the gaps in knowledge enumerated above. This thinking was informed by a substantial literature review, in which we first engaged with the policy literature on NZ, characterising the changes on the horizon under this policy agenda (detailed under ‘key policy changes’ below). As a team of researchers we then read deeply and widely into the various literatures that deal with inequality, vulnerability, injustice and key NZ policy areas, collecting over 550 sources that address these issues, in order to better understand the current and future risks of this transition (summarised in ‘background’ below). Our conceptual thinking, structured using the Bristol Social Exclusion Matrix (B-SEM), was intended to close the research gaps above, by providing a means of identifying the people and places at risk of exclusion under NZ, using the concept of participation to propose a focus on people’s ability to participate in society under NZ. This focus helps us to articulate the ‘risks of social exclusion under NZ’ (our section heading), and who these are likely to affect. We identified these risks by revisiting the extensive literature on the inequalities, vulnerabilities and injustices associated with key NZ policy areas from our review, looking for the current challenges facing people, and the concerns that they expressed in relation to NZ futures.

We finish by presenting our conceptual framework ‘towards an inclusive net zero’, and using it to make recommendations for future policy. We hope that this way of thinking will allow practitioners and policy-makers to integrate inclusive thinking into their planning on NZ. While this framework is principally relevant for the UK, we think it may also be useful in other nations, which face similar challenges in reducing carbon emissions, and share similar visions for a NZ future.

Background

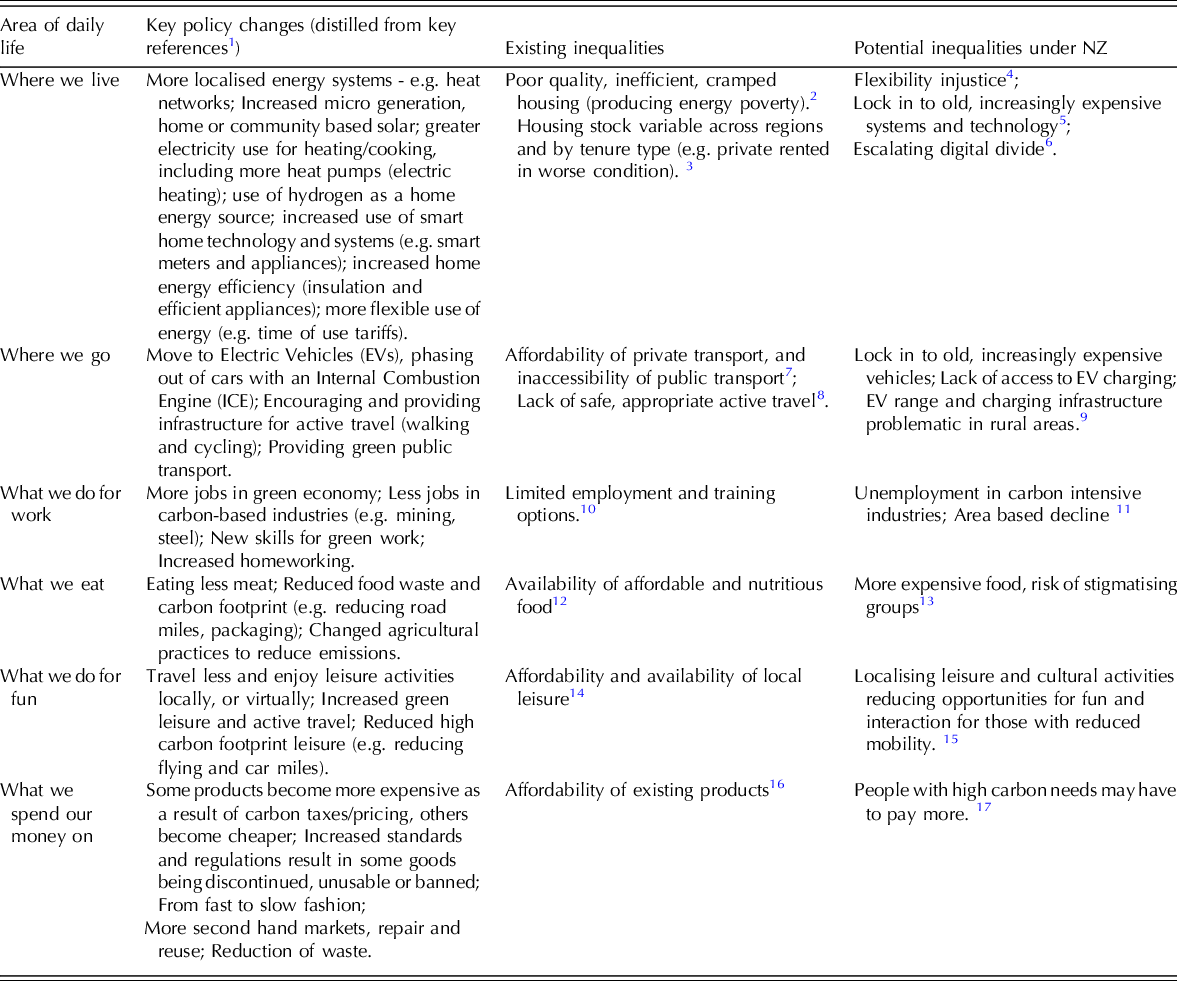

Table 1 provides a synthesis of our literature review drawing together policy and scholarly work relating to NZ related changes, how they relate to existing inequalities, and where they may create new ones. The table is explained in detail in the rest of this section

Table 1 Key policy changes identified associated with the Net Zero transition and associated inequalities

Key policy changes

There is a growing knowledge base that considers which policies are necessary (and likely) to achieve NZ. For example within the policy sphere the Climate Change Committee (CCC) and Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy provide regular, thorough analysis. Citizen-led policy work via the Climate Assembly, and academics from the Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions (CREDS), have also presented visions of future NZ life (see BEIS, 2021a; CREDS et al., Reference Pye, Betts-Davies, Eyre, Broad, Price, Norman, Anable, Bennett, Brand, Carr-Whitworth, Marsden, Oreszczyn, Giesekam, Garvey, Ruyssevelt and Scott2021; Climate Assembly UK, 2020; CCC 2021, 2020a, 2020b).

The first two columns of Table 1 summarise the climate policy changes likely to come about under NZ taken from these visions of life in the future. Summarised from the government, citizen and academic sources above, they present a largely unified vision of life under NZ with little contestation or variation. The vision offered is often technical in nature, with changes to policy areas and their systems highlighted. Taking transport for example: there is detailed discussion within the CCC work regarding how to reduce the climate impact of transport systems through a shift from petrol and diesel vehicles to electric vehicles (EVs), a ban on the sale of new internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles in the early 2030s, and the electrification of public transport systems. It is notable, however, that these visions represent a radical social transformation, which will cut across many aspects of people’s lives. The magnitude and breadth of change in the way we live our lives is rarely mentioned in these visions (see our first identified research gap above).

Rather than replicate a technical sectoral approach here, and given our interest in understanding how people’s everyday lives will be affected by NZ changes, we categorise the expected changes associated with NZ in this table (column one) using a deliberately accessible approach. For example, our ‘Where we go’ is something that can be understood by everyone; ‘mobility’ or ‘transport’ is less accessible. There is evidence that people conceptualise their own lives in this way – thinking about home (‘where we live’) and leisure (‘how we have fun’) as being associated with different times, having different resources or monetary costs associated with them, and having different priorities in decision-making and budgeting (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bookbinder, Middlemiss, Hall, Davis and Owen2023; Middlemiss et al., Reference Middlemiss, Ambrosio-Albalá, Emmel, Gillard, Gilbertson, Hargreaves, Mullen, Ryan, Snell and Tod2019; Middlemiss and Gillard, Reference Middlemiss and Gillard2015). Further, this approach highlights the relationship between different areas of change (e.g. the increased use of EVs will also affect how people use energy in the home). Indeed, changes in one area will affect the ability of individuals, households and communities to participate in change in other areas.

Recognising existing and identifying new inequalities relating to NZ

Literature on the topic is clear that climate policy changes associated with NZ that fail to consider existing inequalities risk exacerbating these and harming some of the most vulnerable in society (Gillard et al., Reference Gillard, Snell and Bevan2017; Robinson and Shine, Reference Robinson and Shine2018). Concerns regarding the negative consequences of pursuing an environmental agenda without due consideration of social needs have become a central feature of global climate policy (ILO, 2015; Just Transition Centre, 2017; UNRISD and ULIP, 2018), and also feature within the Social Policy literature on eco-social policy and sustainable welfare (Bohnenberger, Reference Bohnenberger2020; Büchs, Reference Büchs2021; Büchs and Koch, Reference Büchs and Koch2017; Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick2014; Gough, Reference Gough2022, Reference Gough2015; Hirvilammi, Reference Hirvilammi2020; Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022; Zimmermann and Graziano, Reference Zimmermann and Graziano2020). These concerns are largely absent from the policy visions on NZ that we introduced above and in column two. Yet we know that factors relating to income, place, and other socio-demographic characteristics will shape the ways in which households will be able to engage with the NZ agenda (Gillard et al., Reference Gillard, Snell and Bevan2017; Groves et al., Reference Groves, Kenwood, Shirani, Thomas and Pidgeon2017; IPPR, 2017; Johnson, Reference Johnson2020; JTC, 2020; Scott and Powells, Reference Scott and Powells2020; Waitt and Harada, Reference Waitt and Harada2019). One of the reasons that we know this is that the discipline of social policy has a long tradition of documenting how different people are affected by inequality. Indeed, changes in each of the areas of life above will be shaped by the unique characteristics of the household, and the features of their community, and the inequalities that people face in relation to each area (Bouzarovski and Simcock, Reference Bouzarovski and Simcock2017; Calver and Simcock, Reference Calver and Simcock2021; Markkanen and Anger-Kraavi, Reference Markkanen and Anger-Kraavi2019). The existing and potential new inequalities arising under NZ are explored in the remaining two columns of Table 1.

Taking ‘where we live’, for example, there is a well-established literature that considers existing housing inequalities, energy poverty, and associated impacts, including poor physical and mental health, and reduced educational attainment (Ballesteros-Arjona et al., Reference Ballesteros-Arjona, Oliveras, Bolivar Munoz, Olry de Labry Lima, Carrere, Martin Ruiz, Peralta, Cabrera Leon, Mateo Rodriguez, Daponte-Codina and Mari-Dell’Olmo2022; Marmot Review Team, 2011; Middlemiss, Reference Middlemiss2022). These inequalities are produced and reproduced by multiple factors including: low income, disability, employment status, poor housing infrastructure, and challenges associated with the private rented sector. Existing literature tells us that these inequalities will only be alleviated with significant, multifaceted interventions (including improvements to infrastructure alongside financial measures – Bartiaux et al., Reference Bartiaux, Day and Lahaye2021; Middlemiss, Reference Middlemiss2020). The changes required by the NZ agenda (substantial changes to energy systems and a fundamental shift in the way in which people use their homes and engage with energy) will result in significant challenges given these existing inequalities (Calver et al., Reference Calver, Mander and Abi Ghanem2022; Calver and Simcock, Reference Calver and Simcock2021; Gillard et al., Reference Gillard, Snell and Bevan2017; Martiskainen et al., Reference Martiskainen, Sovacool and Hook2021; Powells and Fell, Reference Powells and Fell2019; Sovacool et al., Reference Sovacool, Hess and Cantoni2021).

The NZ agenda may also introduce new inequalities. For example, the increased use of flexible energy tariffs to allow the electricity grid to manage an increased dependence on electricity may disproportionately harm people with inflexible needs (e.g. people with disabilities – Calver and Simcock, Reference Calver and Simcock2021; Powells and Fell, Reference Powells and Fell2019) or may cause household conflict in terms of who uses energy, when, and for what (Adams et a l., Reference Adams, Kuch, Diamond, Fröhlich, Henriksen, Katzeff, Ryghaug and Yilmaz2021; Johnson, Reference Johnson2020). Equally, the increased emphasis on smart technology has significant implications for older people, those with visual impairments, or with limited literacy (Martiskainen et al., Reference Martiskainen, Sovacool and Hook2021; Sovacool et al., Reference Sovacool, Hess and Cantoni2021).

However, there are also opportunities in the NZ agenda for a more equal society, leading to a transformative rather than a replicative effect. For example, investment in accessible green public transport or in more localised services can both address existing inequalities and reduce carbon emissions. Once again, the Eco Social Policy and Sustainable Welfare literatures are notable here as they provide a positive vision of successfully integrated, transformative social and environmental policies (Gough, Reference Gough2022; Hirvilammi, Reference Hirvilammi2020; Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022). Exactly how we integrate these more progressive visions into NZ policy planning, taking account of existing inequalities, anticipating emerging inequalities associated with NZ, and planning for both a socially inclusive and less environmentally impactful future is the focus of the rest of the article.

Conceptual approach

In our introduction we identified two key research gaps, which we further elaborated in the ‘background’ above. We saw that 1. Research and policy is rather atomised and puts limited efforts into understanding the effects of the transition on everyday life as a whole, and that 2. As a result, justice concerns are not integrated into planning for NZ. We do see some calls for rectifying current inequalities (e.g. energy poverty), and some wider visions of more progressive futures (in the Eco Social Policy and Sustainable Welfare literatures), but there is little consideration of how current planning should address them.

To address these research gaps, we introduce the concept of social exclusion, which offers a useful lens for understanding inequalities in the NZ transition. While most definitions of poverty in the UK focus on insufficient resources – notably, income – social exclusion broadens the scope to include relativity, agency and dynamics (Atkinson, Reference Atkinson1998). Social exclusion is relative because an individual or a community can only be excluded in relation to circumstances of the society around them, and involves agency or a lack of it through the act of exclusion or even self-exclusion. It is a dynamic process because it focuses not only on the current state but also on expectations for the future.

In their landmark work on social exclusion, Levitas et al. (Reference Levitas, Pantazis, Fahmy, Gordon, Lloyd-Reichling and Patsios2007) define the term as: “a complex and multidimensional process [that] involves the lack or denial of resources, rights, goods and services, and the inability to participate in the normal relationships and activities, available to the majority of people in a society, whether in economic, social, cultural or political arenas” (ibid.: 25). This definition includes three domains: 1) resources, 2) participation and 3) quality of life, which constitute the Bristol Social Exclusion Matrix (B-SEM). Here we adapt Levitas et al.’s articulation of four forms of participation in B-SEM to articulate what a socially inclusive NZ looks like.

We focus on participation in particular, because we found this the most useful way into thinking about what people will need to do, and be able to do under NZ. It also closes the specific gap that we identified above: between the social policy literature which very effectively maps inequality in access to resources (as Levitas et al. would frame it), and the NZ policy visions, combined with the eco-social policy and sustainable welfare literature which has begun to articulate a desired end point of social inclusion. The concept of participation connects these two states, and allows us to understand the barriers and opportunities that exist in the present to addressing the inequalities in access to resources in future.

While we draw on B-SEM definitions of participation, these do need some work to enable us to use them in the context of the NZ transition. Here we take each form of participation in turn, explaining how they need to be reshaped in this context.

B-SEM indicators of economic participation primarily concern paid employment (Levitas et al., Reference Levitas, Pantazis, Fahmy, Gordon, Lloyd-Reichling and Patsios2007, p.90). This is also significant under NZ although we discuss employment elsewhere. Instead, economic inclusion within NZ captures the extent to which people are able to make economic decisions that allow them to change the way that they live their lives, reducing their carbon footprint, and keeping up with NZ related changes. Economic participation in NZ is therefore focused on whether households are able to keep up financially, shifting the definition of economic participation to centre consumption instead of production.

B-SEM defines social participation as taking part in common social activities and having meaningful social roles (Levitas et al., Reference Levitas, Pantazis, Fahmy, Gordon, Lloyd-Reichling and Patsios2007, p.90). We take a very similar approach in defining social participation in NZ, with the exception that we also include cultural and leisure activities in this category. We do this because we find that impacts on cultural and leisure activities and social life under NZ are shaped by similar forces: especially the need to reduce the energy used in mobility, and by extension to reduce the amount that people travel in everyday life.

In the B-SEM framework, the domain of cultural participation refers to basic skills and educational attainment, access to education and lifelong learning, cultural leisure activities and internet access (Levitas et al., Reference Levitas, Pantazis, Fahmy, Gordon, Lloyd-Reichling and Patsios2007, p.91-92). In the context of NZ, we refocus this form of participation to encompass employment, education and skills, given the extensive transformation that will need to occur in this space. We included participation in cultural and leisure activities under ‘social participation’ above.

In the B-SEM categorisation, political participation includes citizenship status, enfranchisement, political participation, civic efficacy and civic participation (Levitas et al., Reference Levitas, Pantazis, Fahmy, Gordon, Lloyd-Reichling and Patsios2007, p. 92). As is typical in environmental politics, scenarios for NZ put a huge amount of emphasis on engaging the public in decision-making processes and in community action and activism (Climate Change Committee, 2021). There is a sense that a successful transition to NZ requires public support and engagement, which can be expressed via product choice, voting and protest (Perlaviciute et al., Reference Perlaviciute, Steg and Sovacool2021). Here we mainly focus on political and civic action on NZ, as opposed to political consumerism.

We could have used other frameworks to structure this thinking. We have also, for instance, been influenced by the capabilities approach, which has a similar emphasis on understanding the potential that people have to act (their capability or their ability to participate) and that has been used effectively in related fields (Middlemiss et al., Reference Middlemiss, Ambrosio-Albalá, Emmel, Gillard, Gilbertson, Hargreaves, Mullen, Ryan, Snell and Tod2019). Our choice of the B-SEM framework was made because of its relative simplicity, and its enumeration of four forms of participation which (when revised) can be helpfully applied in the context of NZ. A focus on participation allows us to centre the question ‘what can people do’, and in doing so to understand better the current barriers and opportunities to action. It also allows us to cut across the more customary presentation of NZ through distinctive policy areas (e.g. housing, transport etc.), and consider the more rounded impact on people across the board (e.g. with regards their ability to participate in social life).

Risks of social exclusion under net zero

Here we articulate the risk of exclusion for each type of participation, as well as identifying who is at risk of exclusion.

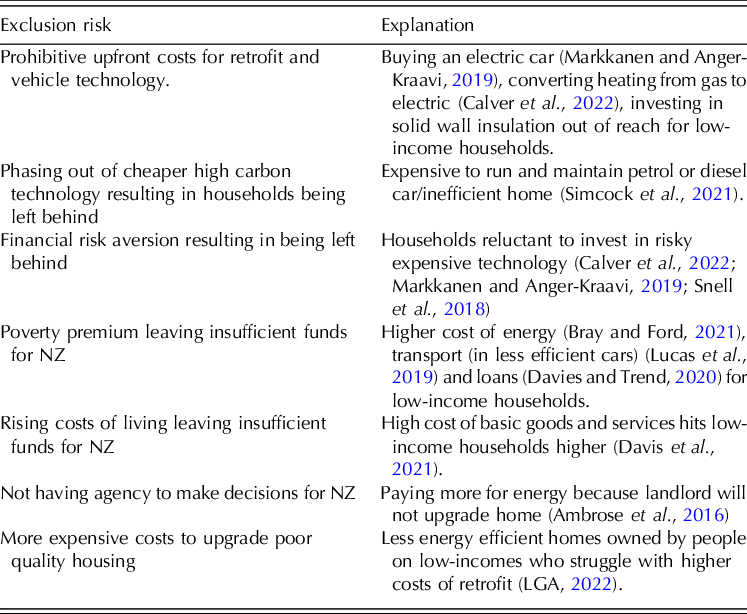

Economic participation

To afford the high upfront costs of new low carbon technology without government support, especially with respect to ‘where we live’ and ‘where we go’, households will need capital or affordable credit, flexibility of spending power, and the ability to take financial risks. There are also financial implications associated with households being unable to keep up with NZ related changes. Table 2 summarises the risks of economic exclusion under NZ.

Table 2 Risks of economic exclusion under NZ

The key population of concern here is low-income households, due to income levels, and availability of savings (Gillard et al., Reference Gillard, Snell and Bevan2017). This affects those in relative income poverty (i.e. below 60 per cent of the national median income), and some higher earning households due to rising costs of living. Low-income households are unevenly distributed, both socially and spatially. For instance, higher wages are concentrated in a handful of cities (notably, London) and the South, while the North and some coastal and rural areas have lower average wages (Overman and Xu, Reference Overman and Xu2022). The bottom 10 per cent of earners make a similar amount everywhere (£eight-nine per hour), placing low-income households in high-income regions at a greater disadvantage, as they frequently have a higher cost of living (ibid.).

There are also particular intersections that are ill-served by policy. Tenants, who are frequently on lower incomes, are particularly vulnerable to changes associated with NZ home upgrades. Those in private-rented accommodation in particular have limited agency to upgrade to new low-carbon home heating and insulation technologies due to the so-called ‘split incentive’ – landlords seeing no gains from energy efficiency improvements in the home (Ambrose et al., Reference Ambrose, McCarthy and Pinder2016; Miu and Hawkes, Reference Miu and Hawkes2020). Tenants in social housing have sometimes been well supported with retrofit, but recent cuts in local authority funding and budgets have created more barriers (Snell et al., Reference Snell, Bevan and Gillard2018). Low-income owner-occupiers in expensive or hard to treat housing (e.g. Victorian properties) may also require additional support.

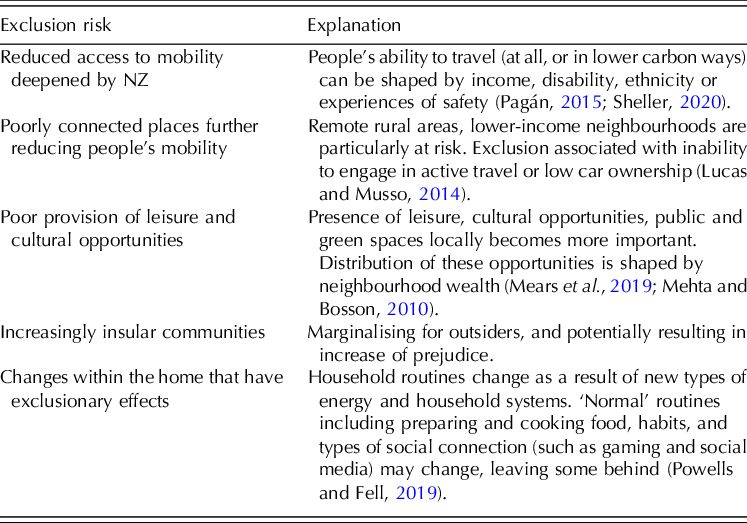

Social participation

The impacts of NZ on social participation are very rarely discussed in the literature, but hugely important. The distribution of leisure and cultural opportunities is highly unequal, with some neighbourhoods offering very limited opportunities for entertainment. Further, some neighbourhoods are unsafe or felt as unsafe by residents. There is a risk of society becoming more parochial as people are less able to travel (Quilley, Reference Quilley2013).

Reducing mobility is likely to have localising effects on very many aspects of everyday life, including working life, leisure and cultural opportunities, and social contact with friends and family. Travel by air, and international travel more generally, will become less available and more expensive. Social participation in local neighbourhoods is also likely to be shaped by the increase in active travel (walking and cycling). This may have positive life impacts, as increased active travel is associated with reduced crime and more social cohesion (Aldred and Goodman, Reference Aldred and Goodman2021). Being able to operate comfortably within the home is also likely to affect social participation as living environments are transformed. Table 3 summarises the risks of social exclusion under NZ.

Table 3 Risks of social exclusion under NZ

Those most affected by these changes will be:

-

1. People who cannot afford to travel: low-income households, and people experiencing other intersectional inequalities are excluded (Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Stokes, Bastiaanssen and Burkinshaw2019; Sheller, Reference Sheller2020; Simcock et al., Reference Simcock, Jenkins, Lacey-Barnacle, Martiskainen, Mattioli and Hopkins2021);

-

2. People who live at a distance from their loved ones: people who live far away from in-country family, and migrants are likely to experience severance in relationships (Mattioli et al., Reference Mattioli, Morton and Scheiner2021);

-

3. People who live in poorly served communities: those served poorly by transport – in rural and peripheral areas; and those served poorly by leisure and cultural opportunities (Lucas and Musso, Reference Lucas and Musso2014);

-

4. People with lower capacity for mobility: including disabled people, face more substantial cost and psychological barriers to active transport in areas with limited infrastructure (Mullen, Reference Mullen2021; Schreuer et al., Reference Schreuer, Plaut, Golan and Sachs2019).

-

5. Women and LGBT+ people who are less likely to walk, cycle or take public transport in potentially unsafe conditions (Doran et al., Reference Doran, El-Geneidy and Manaugh2021; Koskela and Pain, Reference Koskela and Pain2000; Lubitow et al., Reference Lubitow, Abelson and Carpenter2020; Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Stokes, Bastiaanssen and Burkinshaw2019).

-

6. People with disabilities, older people, younger people, and women who may need more support with household level changes (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Kuch, Diamond, Fröhlich, Henriksen, Katzeff, Ryghaug and Yilmaz2021; Johnson, Reference Johnson2020; Snell et al., Reference Snell, Bevan and Gillard2018; Sovacool et al., Reference Sovacool, Hess and Cantoni2021)

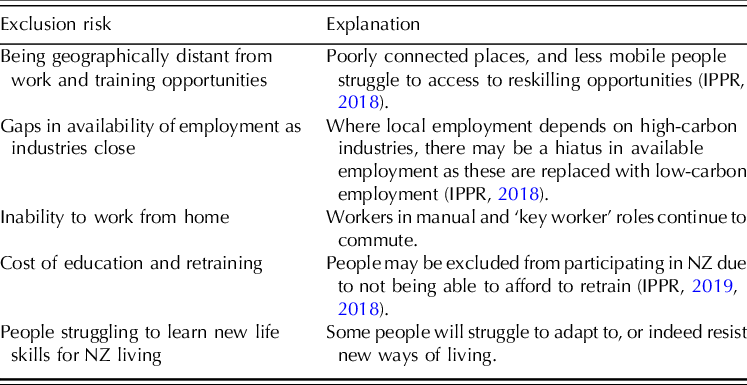

Employment, education and skills

Under NZ we expect a substantial reshaping of the economy, with high-impact products and services giving way to lower-impact alternatives. This will result in the transformation of industrial processes, which in itself will require different skills from workers. Some jobs will cease to exist, and people will need to retrain, building new skills for new low-carbon industries (BEIS, 2021b; Kapetaniou and McIvor, Reference Kapetaniou and McIvor2020). Where we work is also likely to change, with an increased emphasis on working from home for those that can (Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Gray, Kyle, Song and Davies2022). There will also be broader skills and knowledge building needed to allow people to adopt low-carbon behaviours (e.g. plant based diets; use of energy efficient appliances). The risks associated with these changes are summarised in table 4.

Table 4 Risks of employment, education and skills exclusion under NZ

Many of the risks in this category are associated with proximity to opportunities to work and retrain, and increased barriers to access work under NZ (IPPR, 2019, 2018; Silveira and Pritchard, Reference Silveira and Pritchard2016; Sudmant et al., Reference Sudmant, Robins and Gouldson2021). Specifically, people in rural areas, areas dependent on high-carbon industries, and areas where unemployment is high will likely have less employment and reskilling opportunities within travelling distance. People in areas dependent on high-carbon industries will have to make a bigger investment in change, which suggests a need for national planning around reskilling (IPPR, 2018; Silveira and Pritchard, Reference Silveira and Pritchard2016; UKERC, 2018). Similarly, disabled people and older people may find it hard to access different opportunities in places where transport is inaccessible. Further, access to lifelong learning opportunities to ‘upskill’ for the NZ economy is socially patterned, with those from lower income households less likely to take part. In addition, people in low-income households are more likely to be concerned about spending on education and reskilling.

Political participation

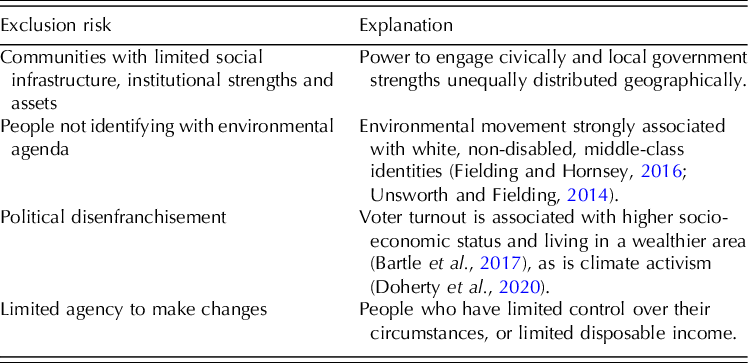

There is an existing tradition of experimentation with democratic and civic structures in the environmental movement, so we have some evidence of the challenges and risks associated with these. For instance, numerous fora already attempt to shape environmental policy towards social priorities, such as formal inclusion of minority groups in governance processes, and citizens’ juries (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Van Alstine, Cotton and Middlemiss2021; Thew et al., Reference Thew, Middlemiss and Paavola2020). Policies for NZ anticipate a shift from centralised policies and approaches to local decision-making and community-focused policymaking (BEIS, 2021c; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Qureshi, Frost and Massey-Chase2022). In addition, there is a strong perceived role for civic participation through grassroots activity, including community energy and transport projects. This includes local people coming together to create their own local assets, across housing, food cultivation and energy (Anantharaman et al., Reference Anantharaman, Kennedy, Middlemiss and Bradbury2019; Colding et al., Reference Colding, Barthel, Ljung, Eriksson and Sjoberg2022; Taylor Aiken et al., Reference Taylor Aiken, Middlemiss, Sallu and Hauxwell-Baldwin2017; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Qureshi, Frost and Massey-Chase2022). The risks associated with political exclusion are summarised in table 5.

Table 5 Risks of political exclusion under NZ

Exclusion from political process is therefore likely to affect people from particular backgrounds. Literature in the environmental sphere notes that participatory processes typically favour white, middle-class non-disabled people, and often have insufficient resourcing to engage more excluded people (Fielding and Hornsey, Reference Fielding and Hornsey2016; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Van Alstine, Cotton and Middlemiss2021; Unsworth and Fielding, Reference Unsworth and Fielding2014). Practices associated with civic engagement on environment are also highly classed, and linked to white and non-disabled identities (Fenney Salkeld, Reference Fenney Salkeld2017; Grossmann and Creamer, Reference Grossmann and Creamer2016).

Given the emphasis on transforming everyday life under NZ, people’s agency in making decisions around everyday life and being able to engage in political consumerism are important in their ability to participate politically. This includes constraints associated with access to enabling infrastructure, as well as constraints associated with particular roles (e.g. being a tenant).

Living in a part of the country where there are opportunities to participate in both civic and political action is important (King et al., Reference King, Padmanabhan and Rose2021). Evidence suggests that there is unequal distribution of shared community resources geographically (Tauschinski et al., Reference Tauschinski, Sogomonian and Boelman2019). Urban areas possess significantly fewer community resources than rural areas, lagging in shared resources such as energy projects or community-owned assets (ibid.).

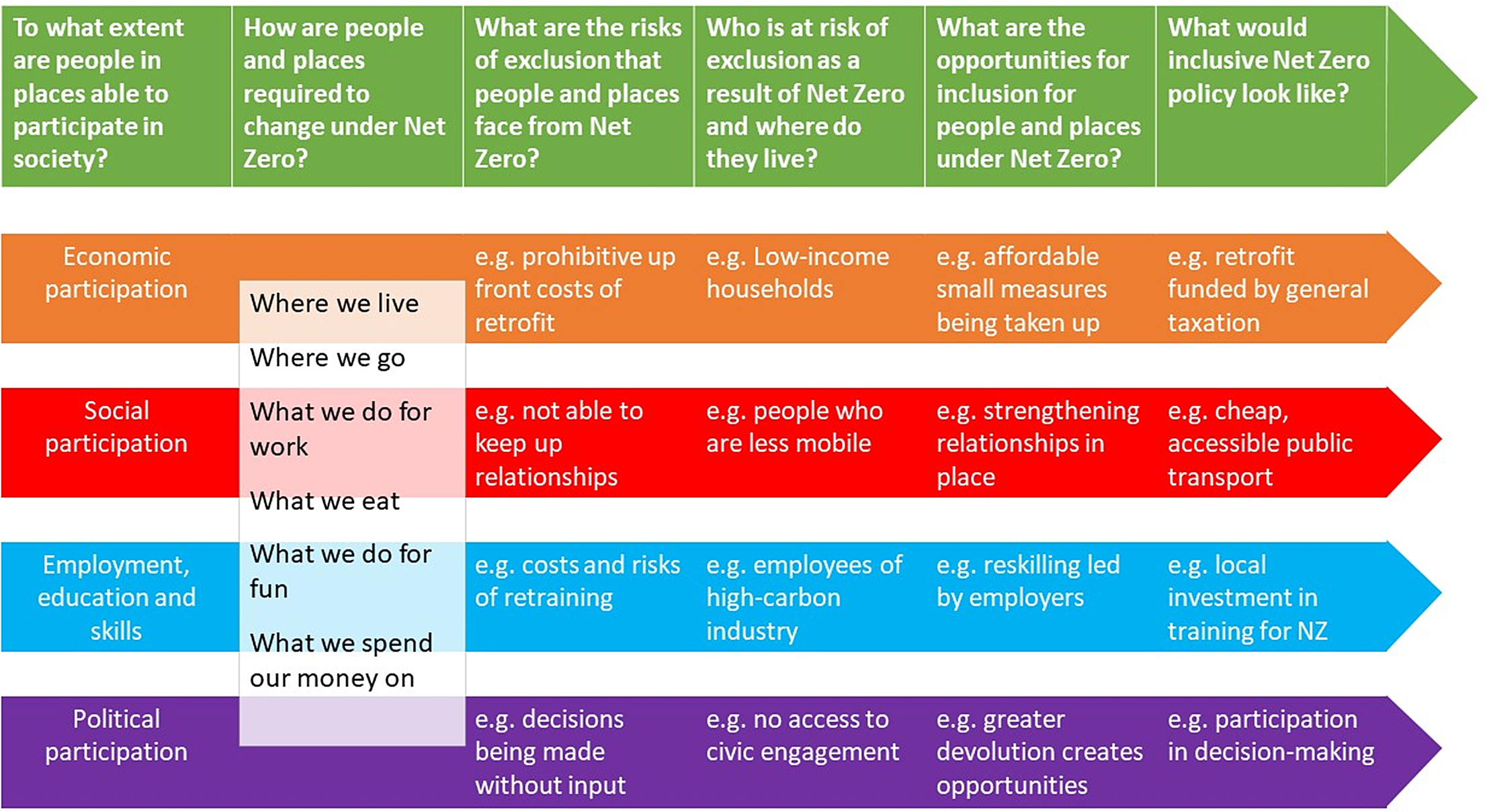

Conclusion and implications for policy

Our conceptual framework in figure 1 summarises the key ideas we have raised here, structured by an overarching set of questions (in the green arrow at the top of the figure), and broken down into the different types of participation inspired by B-SEM (in each of the coloured arrows below). We use the framework to show what a socially inclusive pathway to NZ would look like: articulating the inequalities that people currently face, summarising the changes NZ will bring, the risks of exclusion in NZ and who these affect; and the opportunities for better inclusion and policy.

Figure 1. Towards an inclusive Net Zero: a conceptual framework

Our thinking raises a number of implications in terms of how policy and practice should respond to these issues. First, there is a need to integrate social inclusion concerns systematically into NZ policy and planning. This means recognising people’s different abilities to participate in NZ due to social and geographical differences, and taking this into account in policymaking. Examples of policies that take better account of social inclusion in the transition to NZ could include:

-

Economic participation: providing low-income households with additional capital funding to pay for expensive measures to reduce carbon emissions (e.g. for mobility and for energy efficiency at home – HM Treasury, 2021).

-

Political participation: placing the locus of control closer to people by empowering local authorities to decide on specific NZ policy pathways.

-

Employment, education and skills: Anticipating job losses in particular geographical locations, and planning for continuity of employment (Rosemberg, Reference Rosemberg2010)

Second, given the risks of exclusion associated with being on a low-income, and for other people with social characteristics that are commonly excluded (disabled, LGBT+, women etc.) there is a need to strengthen infrastructures of all types to enable people’s participation in NZ. Good infrastructure raises prospects for all, and resourcing people’s participation in this way is hugely important to ensure both that targets are met, and that people continue to support this agenda. Note also that such investment is likely to result in multiple social, health and economic benefits in the short term (Ballesteros-Arjona et al., Reference Ballesteros-Arjona, Oliveras, Bolivar Munoz, Olry de Labry Lima, Carrere, Martin Ruiz, Peralta, Cabrera Leon, Mateo Rodriguez, Daponte-Codina and Mari-Dell’Olmo2022). Some examples of policy that strengthens infrastructure include:

-

Social participation: Invest in excellent, environmentally-sound and cheap public transport: allowing poorer households to maintain social and cultural participation (Lucas and Pangbourne, Reference Lucas and Pangbourne2014; Markkanen and Anger-Kraavi, Reference Markkanen and Anger-Kraavi2019).

-

Social participation: improve care infrastructure (for older people and children) to accommodate reduced mobility.

-

Employment, education and skills: Narrow the digital divide to allow people to work remotely, including improving digital literacy and providing quality internet connection.

-

Economic participation: Prioritise hard to treat properties (these often house those on lowest incomes – Snell et al., Reference Snell, Bevan and Gillard2018)

Third, we can see some clear sticking points that need to be addressed in the near future. These are areas of policy that currently exacerbate people’s ability to participate in NZ. Some examples of this include:

-

Political participation: Make additional efforts to include people from minorities that do not frequently engage in political processes.

-

Economic and political participation: Address the split incentive for rented properties by supporting landlords (Ambrose et al., Reference Ambrose, McCarthy and Pinder2016)

-

Employment, education and skills: Offer retraining opportunities for those in carbon intensive industries; offering incentives for new industries to locate in areas where carbon intensive industries are closing.

The NZ agenda presents a clear opportunity for progressive, inclusive change. Academic study in this field is only emerging, and whilst there is evidence within different sectors about the social inclusion effects of decarbonisation and policy change (especially within the transport, housing, and labour market fields), little has been done to look across these policy areas, placing people and everyday life at the centre of analysis. We think the engagement of social policy researchers in this field offers an opportunity to produce more people-centred evidence. We hope that our framework will encourage researchers to consider how the evolving NZ landscape is likely to shape, create, and reshape people’s ability to participate in NZ, and in turn, to identify the best policy approaches to rebalance these.

Financial Support

This research was funded by the Nuffield Foundation, full project title: Understanding family and community vulnerabilities in transition to net zero.