Introduction

As societies rebuild and recover from the Covid-19 global pandemic, this article aims to provide a better understanding of the role of cities and local social policy in addressing responses to and impacts of the pandemic, as well as in governing a place-based approach to pandemic recovery, human security, and inclusive and sustainable growth. The study focuses on the metropolitan cities of Seoul, Korea and London, England and draws on secondary data sources, workshops, and qualitative interviews with key city stakeholders in both cities to address the following questions: What have been the impacts of and policy responses to the recent global pandemic in the metropolitan cities of Seoul and London? How has the dynamic relationship between different tiers of government, institutions, and actors shaped local social policy responses and human security in the two cities? What are the urban and local social policy challenges emerging in the post-Covid cities of Seoul and London? What role can local social policy play in addressing these challenges and promoting human security and inclusive cities?

The article will begin by outlining the urban contexts of Seoul and London and drawing out key dimensions of inequalities and insecurities. It will then go on to explore the relationship between different tiers and institutions of governance and local social policy responsibilities, policies, and outcomes in Seoul and London through the lens of critical human security and a multi-scalar governance and territorial matrix. The final section will highlight urban and local social policy challenges for human security in the post-Covid cities of Seoul and London, and the importance of supporting and mobilising local governance, social policy, and infrastructure for human security.

There is a growing recognition of the importance of the study of local social policy brought about not only by the shift in responsibility for the development and implementation of many social policies and public services from national to local government (Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Javornik, Brummel and Yerkes2021; Kazepov et al., Reference Kazepov, Barberis, Cucca and Mocca2022) but also the translation and embedding of global policy initiatives into local policy making. The United Nations 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals include a standalone goal, SDG 11, ‘to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’ (UN, 2015), and there has been a growing emphasis on ‘localising’ the SDGs by contextualising and achieving them through city level actions (Fox and Macleod, Reference Fox and Macleod2021). Inclusive cities are considered by the United Nations to be critical to post-pandemic recovery with recent research having recognised the role that different tiers of government, cities, city stakeholders, and local social policy can play in contributing to this goal (OECD, 2020; UN-Habitat, 2021; Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez, Moghadam, Sharifi and Lombardi2023).

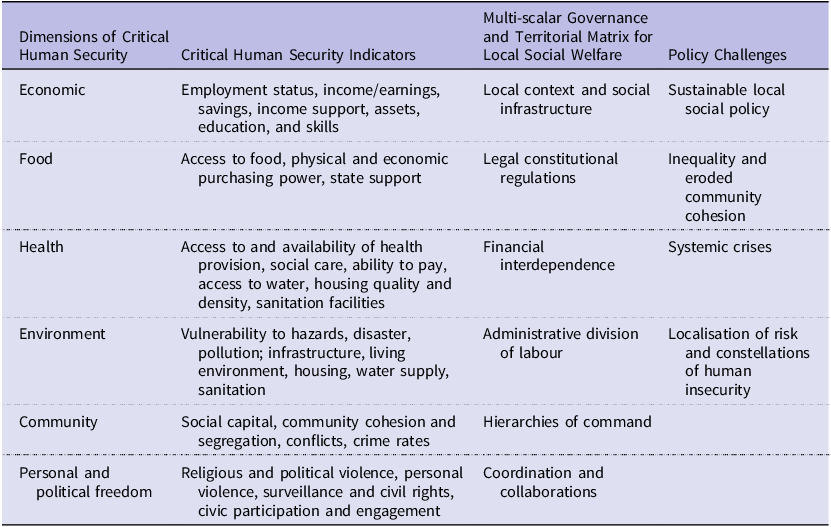

In this context localising, territorialising, and integrating a human security perspective and focus through a multi-scalar governance and territorial matrix (Table 1) (Brenner, Reference Brenner1998; Kazepov et al., Reference Kazepov, Barberis, Cucca and Mocca2022) has the potential to ‘provide a cognitive and practical framework… through which to identify gaps in protection infrastructure and ways to strengthen or correct it’ (Ogata and Cels, Reference Ogata and Cels2003: 274). Critical human security includes a range of integrated dimensions of social policy and everyday life including economic, health, food, housing, environmental, community, and personal security (see Column 1, Table 1) and their associated indicators (Column 2, Table 1) (UN, 2016; Newman, Reference Newman2021; Kennett et al., Reference Kennett, Lee and Kwon2024). These dimensions, their intersection, and the implications for communities and households at the local level can be highlighted through the multi-scalar governance and territorial matrix, the dimensions of which are outlined in Column 3, Table 1 (Brenner, Reference Brenner1998; Kazepov et al., Reference Kazepov, Barberis, Cucca and Mocca2022). Multi-scalar governance for local social welfare emphasises the importance of local context and social infrastructure with regard to health and social care, education, housing ‘and other services and facilities that enhance well-being and social cohesion’ (Renner et al., Reference Renner, Plank, Getzner, Renner, Plank and Getzner2024: 1). Urban social infrastructure is also a socio-political phenomenon that represents complex contestations over power and resources (Latham and Layton, Reference Latham and Layton2019; Reference Latham and Layton2022) and the racialised and gendered politics of security and insecurity (Pan, Reference Pan2021; Gabauer et al., Reference Gabauer, Knierbein, Cohen, Lebuhn, Trogal, Viderman, Gabauer, Knierbein, Cohen, Lebuhn, Trogal and Viderman2021; Hall, Reference Hall2020) which are in turn entangled with how contemporary urban socio-economic disparities are maintained and perpetuated (Willis, Reference Willis, Kim and Chung2023). The multi-scalar matrix also incorporates a recognition of the distribution of legal and administrative responsibilities between different tiers of government, as well as financial interdependence, coordination and collaboration and ‘tangled hierarchies’ of power and authority (Kazepov et al., Reference Kazepov, Barberis, Cucca and Mocca2022; Whitehead, Reference Whitehead2003; Jessop, Reference Jessop and Kennett2004).

Table 1. Critical human security, multi-scalar governance, and territorial matrix: dimensions, indicators, and policy challenges

Source: Authors own devised from Brenner (Reference Brenner1998); Human Security Unit (2016); Kazepov et al. (Reference Kazepov, Barberis, Cucca and Mocca2022).

Whilst comparative social policy has tended to focus at the national level, local social policy, local state capacity (Pill, Reference Pill2024), and social infrastructure (Renner et al., Reference Renner, Plank, Getzner, Renner, Plank and Getzner2024) have key and often neglected roles in the provision of public services and social policy and in promoting and maintaining human security and well-being particularly in turbulent times (The British Academy, 2021). As cities and households have emerged from the global pandemic, policy and everyday life have transitioned to ‘living with Covid-19’ and have been accompanied by changes in the nature of living, working, and managing urban spaces and the emergence of new forms of service provision. In this context, the integration of these approaches will highlight the complex and multisectoral social and public policy challenges facing both Seoul and London in the aftermath of the pandemic, as well as the overlapping, intersectional and multi-layered insecurities, how they have evolved and strategies to address them.

Research design and methodology

The research draws on fieldwork conducted in South Korea and the UK between January 2022 and March 2024 as part of a broader project on critical human security and post-Covid policy challenges in South Korea and the UK. It was approved by the Faculty of Social Sciences and Law Ethics Committee, University of Bristol. The analysis is informed by primary and secondary data from multiple sources including a range of existing international, national, and local secondary data, reports, and other grey literature relating to the cities of Seoul and London and three stakeholder workshops involving academics and researchers, policy makers, and representatives from the non-profit sector (Basedow et al., Reference Basedow, Westrope and Meaux2017: Ørngreen and Levinsen, Reference Ørngreen and Levinsen2017; Hu, Reference Hu, Borgen and Birkeland2024). The international collaborative workshops facilitated the clarification of research questions, multi-level matrix and analytical framework, and their cross-cultural relevance, as well as the identification of data sources and participants. The research also includes a total of 18 qualitative, semi-structured interviews with city and policy stakeholders conducted in Seoul and London with respondents from relevant local government and municipal departments, the voluntary and social enterprise sectors and policy think tanks (nine interviews in each city) (Bogner et al., Reference Bogner, Littig, Menz, Bogner, Littig and Menz2009). The interviewees were selected after a mapping of relevant stakeholders and their interaction with different dimensions of human security conducted during the collaborative workshops and outlined in Column 1, Table 1, and their connection to local economic development (economic security); environment, housing, and infrastructure (environmental security); social welfare, health, and social care (economic, food, and health security); and community development (community security and personal and political freedom). The interviews were carried out utilising a combination of remote video calls (Engward et al., Reference Engward, Goldspink, Iancu, Kersey and Wood2022) and face-to-face, in-person meetings and lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. Each interview was guided by a similar range of topics including (a) identifying and describing role of local social policy, (b) nature of local social infrastructure, (c) relations between different tiers of government and other urban stakeholders, (d) impact of and responses to the pandemic at the local level, (e) ongoing and future challenges for cities and human security, and were conducted in either English or Korean, depending on the preference of the participant. All interviews were translated into English and transcribed.

The research presented in this paper will primarily rely on paraphrasing and summarising information from sources under identified themes, rather than directly quoting large sections of text verbatim (Bissell, Reference Bissell2023). This enables us to draw together the different strands of data from both cities and in so doing embed and contextualise the participants’ views.

Whilst the various methods employed in this research facilitated the capturing of a diverse range of views, themes and a degree of co-production in the research process, the sample and number of participants is relatively small, which could have resulted in the omission of and failure to recognise important perspectives and topics. However, the methodological triangulation incorporated into the research is designed to enhance the robustness of the research findings, facilitate cross-cultural social policy research and to a better understanding of the role of cities and local social policy in promoting human security and inclusive and sustainable growth.

Embedded cities, local social infrastructure and insecurity

We live in an increasingly urbanised, interconnected, multi-scalar, complex, and individualised world in the context of multidimensional systemic risk (Schweizwer, Reference Schweizer2021), eroding social cohesion, and traditional sources of security and social protection, and fragmented labour markets (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1993; World Economic Forum, 2021, 2024). Cities can be conceptualised as ‘dynamically evolving, multi-tiered socio-spatial relations embedded with a broader, dynamically evolving whole’ (Brenner, Reference Brenner2019: 3) with subnational social welfare and social policy measures located within these broader multi-scalar and inter-scalar relationships and systems (Kazepov et al., Reference Kazepov, Barberis, Cucca and Mocca2022). This conceptualisation of cities and urban space lends itself to a relational understanding of local state capacity, social infrastructure, and the role of city governance in the governing of locality and local welfare policy (Pill, Reference Pill2024) and in ‘…producing and sustaining environments which afford opportunities for, and coordination among, multiple activities and flows’ (Healey, Reference Healey2018: 67).

Urban spaces weave these relationships together to form historically specific configurations, combinations of which vary between places. London and Seoul are characterised as global cities that are located within and mediate flows of global finance, international trade, and multi-national operations, technology, and climate change (Brenner, Reference Brenner1998; Sassen, Reference Sassen2005). For Brenner (Reference Brenner1998 6) they are indicative of ‘… changing modes of insertion of urban spaces into global circuits of capital, commodities and labor’. Shin and Timberlake (Reference Shin and Timberlake2006: 145) highlight Seoul’s rapid rise up the global hierarchy of cities with London and Seoul now sitting with a group of what they call the ‘most globally central cities in the world’ with leading positions in a range of internationally recognsed measures such as the Digital Cities Index (Seoul 5th and London 6th); Global Financial Centres and Fintech (London 2nd and Seoul 10th); and the Global Power City Index (London 1st and Seoul 7th). However, the strengthening of these modes of insertion also involves more deeply embedding global uncertainties and systemic risk in everyday life through ‘an architecture of insecurity’ (Wernli et al., Reference Wernli, Böttcher, Vanackere, Kaspiarovich, Masood and Levrat2023: 207) and contributing to pressing urban challenges highlighted by the Global Risk Report as social cohesion erosion, societal inequality, and environmental risks and climate change (World Economic Forum, 2021, 2024).

Local governments are themselves engaged within transnational partnerships and actively and strategically forging links beyond the state through strategies of ‘city diplomacy’, ‘urban entrepreneurialism’ (Harvey, Reference Harvey1989), and ‘place-making’ (Hae, Reference Hae, Doucette and Park2019). City mayors in London and Seoul are also collaborating on policies for addressing urban social policy challenges such as the climate emergency (C40 City Climate Leadership Group C40 Cities – a global network of mayors taking urgent climate action) and health (World Health Organisation Creating Healthy Cities Creating healthy cities (who.int)) (Shon, Reference Shon2021). During the early stages of the pandemic city governments engaged in international horizontal collaboration including the Covid-19 Video Conferencing in forty-five cities around the world (SMG, 2020a) and the Cities against Covid-19 (CAG) Global Summit (SMG, 2020b; Shon, Reference Shon2021), both carried out in 2020 and involving the previous mayor of Seoul, Park Won-soon and Sadiq Khan, current mayor of London. At the recent World Cities Summits Mayors Forum held in Seoul in 2023, Mayor Oh Se-hoon, the London mayor, and representatives from fifty cities and international organisations focused on policies and social infrastructure for ‘Liveable and sustainable cities: Forging an inclusive and resilient future’ (SMG, 2023a).

The very embeddedness of these urban spaces within these multi-scalar relations, as well as the perceived strengths of London and Seoul in terms of connectivity, populations density, proximity, resources, social infrastructure, and local state capacity, can also expose and generate local configurations of insecurity and vulnerability (Ranci and Maestripieri, Reference Ranci, Maestripieri, Kazepov, Barberis, Cucca and Mocca2023). These dynamics intersect with national welfare systems and local institutional and policy contexts, creating territorially and spatially specific landscapes of human security and insecurity which, in turn, are mediated by key risk factors such as gender, ethnicity, employment status, class position, and age.

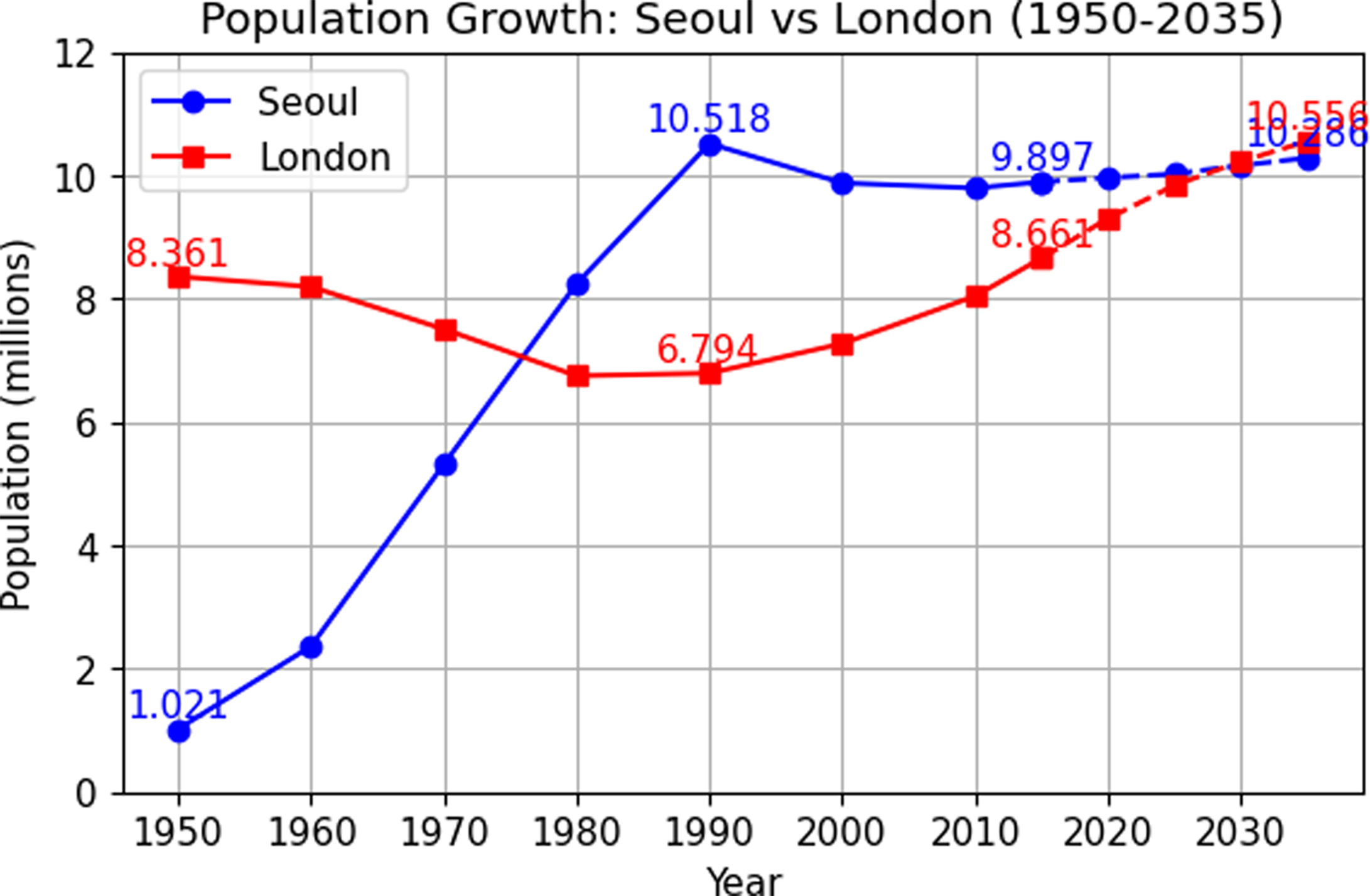

The two cities highlight similarities and differences in terms of context, localised risk, insecurity, and state capacity. Both cities are the political capitals of their respective countries and key financial economic hubs each accounting for nearly a quarter of their respective countries gross domestic product. Seoul and London have similar population sizes (see Fig. 1), and both are iconic, global tourist destinations. However, each of the cities is in turn embedded within very different welfare regimes and local institutional and social infrastructure contexts and responded to the pandemic in different ways as discussed later in this paper (also see Kennett et al., Reference Kennett, Lee and Kwon2024).

Figure 1. Population in London and Seoul 1950–2035 (mill).

Source: Authors own drawn from “https://luminocity3d.org/WorldCity/#3/53.23/39.90” World City Populations Interactive Map 1950–2035.

Both London and Seoul are unequal cities, and whilst the degree of spatial and social inequality is less prevalent in Seoul than in London, wide social and economic disparities are evident. Bae and Joo (Reference Bae and Joo2020: 729) highlight the example of Gangnam in Seoul as symbolic of ‘…socio-economic segregation and political conservatism’, and emblematic of land speculation, extravagance, and obsession with education, with its skyscrapers, luxury apartment living, high-quality amenities, and educational opportunities. In London, too, these alpha territories of the super-rich are clearly evident (Beaverstock and Hay, Reference Beaverstock, Hay, Hay and Beaverstock2016; Burrows et al., Reference Burrows, Webber and Atkinson2017; Atkinson, Reference Atkinson2020) as is the propinquity of wealth and poverty within specific localities, for example, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London one of the wealthiest boroughs in the city, juxtaposed with poorer neighbourhoods with 23 per cent of Kensington and Chelsea neighbourhoods among the most income deprived at the national level, and inadequate housing with 29.8 out of 1,000 households in temporary accommodation in the borough compared to 17 in London overall in 2021 (WPI Economics, 2021).

In London, whilst the proportion of people in poverty remains higher in inner London, there is concern that the gap between inner and outer London is narrowing with Hunter (Reference Hunter2019: 14) highlighting ‘… telling signs of poverty not only evident in central and inner city locations but also in outer districts’. London has a higher proportion of people on higher incomes than any other region of England, whilst also having the joint highest proportion of the lowest incomes. More than half of Londoners in poverty are in work, demonstrating both high levels of low pay and high costs of living in London (Trust for London, 2024). In addition, London is the most ethnically diverse region in England, 20.7 per cent of the population identifying as Asian, 13.5 per cent as Black, 5.7 per cent as mixed, 36.8 per cent as White British, 17 per cent as White Other, and 6.3 per cent as Other, and in 2021 had the largest number of migrants (people born outside the UK (3,346,000) or 37 per cent of the UK total foreign-born population (9.5 million in 2021) (ONS, 2022; The Migration Observatory, 2022), and is a reflection of the UKs colonial past and the settlement of post-colonial immigrant groups arriving after the Second World War, European Union membership, and more recent labour migration and conflict (Pardo, Reference Pardo2018).

In contrast, Seoul remains relatively culturally and ethnically homogenous with Korean history, one of occupation and relatively recent independence and democracy. However, a narrative of multiculturalism has been widely used both nationally and locally for at least the last decade with the aim of transforming Seoul into’“an advanced multicultural city’ (SMG, 2017). The city has growing foreign and migrant communities (SMG, 2023b) and as of 2023, the number of foreign residents in Seoul was approximately 400,000, around 4 per cent of the city’s total population. Most of the foreign population are Chinese citizens of Korean ancestry, followed by Chinese citizens not of Korean ethnicity.Footnote 1 The third largest group was made up of 10,000 US citizens, followed by Taiwanese citizens. Many non-Koreans come to Seoul for work, particularly in sectors like manufacturing, construction, and services. Whilst there is a patchwork of social infrastructure provided by the Korean central government, Seoul Metropolitan Government also provides various levels of support and services designed to help with legal, social, economic, and cultural integration (SMG & Seoul Institute, 2023). In London race and ethnicity have been crucial in shaping drivers of insecurity and access to and experiences of urban social infrastructure and public services, whilst in Seoul, and Korea more widely, it is the boundaries between ‘native-born’ citizens and migrants, including those of Korean descent (Yu, Reference Yu2023). It is these complex entanglements and the implications for human security, local social policy, and inclusive cities that we will explore and attempt to draw out in the context of London and Seoul.

Urban context, interdependencies, and hierarchies of control in Seoul and London

The historical and political legacies, institutional mix, and political economy of Korea and England, and between London and Seoul, vary considerably and shape the dynamics of multi-scalar governance and the territorial matrix (see Table 1), local policy and social infrastructure, and urban development trajectories. The unique historical trajectory in Korea has been shaped by decades of colonial rule, followed by the Second World War, the establishment of the First Republic in 1948 and the devastation of the Korean War between 1950 and 1953. The military dictatorship from 1961 was accompanied by rapid economic growth, with the first free presidential election in 1987 following the nationwide June democracy uprising, and the first civilian president elected in 1993. Cho Soon became the first directly elected mayor in July 1995, filling what has come to be considered the second most powerful elected official position after the president. The current mayor of the twenty-five autonomous Gu (districts) in Seoul (see Fig. 2), Oh Se-hoon, a right wing conservative political figure, was first elected in 2006–2010 (Grand National Party) and again in 2021 as a member of the People Power Party which, up until the impeachment of Yoon Suk Yeol in December 2024, controlled the South Korean presidency and is the second largest party in the National Assembly. It also dominates Seoul Metropolitan Council, which is composed of 112 members and is mainly involved with legislation and administration, budgeting, and auditing, whilst Seoul Metropolitan Government is responsible for health and social services, lifelong education, libraries, public transport, environmental management, public safety, strategies for city development, as well as utilities such as sanitation and water.

Figure 2. Districts (gu) of Seoul (25).

Rapid economic growth, the dominant roles of state bureaucracy and state led resource allocation in top-down urban planning and redevelopment, as well as the developmental welfare state model (Kwon, Reference Kwon2005; Kennett et al., Reference Kennett, Lee and Kwon2024) have significantly impacted on and shaped the economic and social infrastructure and built environment of Seoul (City Stakeholder S8). Rapid urbanisation and population migration to Seoul from the 1960s (see Fig. 1) was followed by large-scale suburban developments within the Seoul Metropolitan Area. Accompanying this in the late 1980s and 1990s, Korea began a process of decentralisation, partly as a response to growing demands for democratisation and local self-governance, with local elections reintroduced in 1991 and 1995, enabling citizens to elect local officials such as mayors and council members.

Following the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Seoul experienced significant changes in its governance and policy framework characterised by financialisation, deregulation, and marketisation. These shifts were aligned with the adoption of New Public Management and New Public Governance perspectives in reshaping local social policy and urban development. Under the previous mayor, Park Won-soon, the approach also included a greater commitment to national-local collaborative governance and a shift to what has been referred to as hierarchical, decentralised governance, representing what Nam and Lee (Reference Nam and Lee2023: 602) describe as ‘…a mixture of post-developmentalist features and the lingering impact of neoliberal rationalities’. While South Korea’s local governments historically functioned as agents of the central government, their role has expanded significantly in recent decades. They now play a crucial role in addressing social problems and implementing innovative policies, with a growing degree of autonomy and capability. The relationship between the central and local governments has shifted more recently towards more cooperation and collaboration when establishing policy priorities (City Stakeholder S5), though the central government still retains significant control, particularly in setting the overarching legal and regulatory framework.

In the UK central local relations are fragmented overlapping ‘…and incoherent… and a sclerotic, fragmented system of overlapping authorities at the sub-national levels’ after forty years of devolution (Richards et al., Reference Richards, Warner, Smith and Coyle2023: 31). The English context is characterised by Pill (Reference Pill2024: 2) as an ‘extremely centralised government system’, and within that demonstrates how local government has been characterised as lacking ‘constitutional protection and financial dependency’, and even with some shifts in power to the local revel, it remains ‘as a “creature” of the state’. A number of commentators have pointed to London’s role as a global financial centre and how this has been prioritised and promoted through neoliberal financialisaton since the 1980s (City Stakeholder L3) (Davis, Reference Davis2022; Martin and Sunley, Reference Martin and Sunley2023). The city region is by far the most prosperous in England and for Martin and Sunley (Reference Martin and Sunley2023: 381) almost represents ‘a city apart’. Since 1965 there have been thirty-two borough councils and City of London (see Fig. 3) mainly concerned with day-to-day services, local social policy, and infrastructure for local residents including social welfare and social services, education, housing, local planning, and environmental services. Local authorities provide a range of statutory services and discretionary welfare with funding coming from a combination of central government and local taxation, with London Council working across boroughs to promote, support, and lobby for collaboration and coordination across sectors, tiers of governance, and policy actors in areas such as public health, social care for children and adults, asylum and refugees, and health partnerships, for example (City Stakeholder L1). In 2000, Greater London Authority was created as another strategic tier of local government comprising the directly elected mayor of London and the London Assembly with an executive consisting of twenty-five assembly members who scrutinise the decisions of the mayor. The mayor has a range of strategic responsibilities including in areas of air quality, housing and economic development, policing, and transport. The mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, is a member of Labour Party and currently in his third term, taking office in 2016. During most of their time in office the country was governed by the national Conservative Government, but following the general election in July 2024 was replaced by the Labour Party.

Figure 3. London borough councils (32) and city of London.

In the UK, the 2008 financial crisis was followed by a period of austerity governance and a ‘recalibration of central/local relations’. Between 2010 and 2018 there was a reduction in government funding for local authorities of nearly 50 per cent (40 per cent in London) severely impacting local state capacity and social infrastructure (City stakeholder L3). This created a situation whereby prior to the pandemic local government had already been ‘hollowed out’ (City Stakeholder L3) and by 2023 London Councils cross-party group representing London’s 32 boroughs and the city of London argued that the capitals borough councils faced a collective shortfall of £400m in 2023, rising to £500m in 2024 (Rufo and Cook, Reference Rufo and Cook2023). The trilemma of rising inflation, increasing social policy responsibilities, and reduced budgets has created ‘an existential period of crisis’ across London as councils struggle to ‘keep the show on the road’ (City stakeholder L1; BBC, 2021). Local institutions’ responsibilities have been expanding (for example social care, housing, education, discretionary social fund) but with reduced capacity to deliver effectively (City stakeholder L3).

The Seoul city government is relatively well-financed with sources of revenue coming from transfers from central government as well as local taxation and an annual budget for 2024 of 45.74 trillion won (approx. $33.75 billion), although this represents a 3.1 percent reduction on the previous year’s budget of 47.19 trillion, with the decrease attributed mainly to the fall in tax revenue due to flowing corporate performance and falling house prices (The Korea Times, 2023).Footnote 2 The majority of the budget is allocated to welfare services (36.6 per cent) and education and district support (25 per cent).

As London and Seoul transition and move forward to ‘living with Covid’ local government has proved not to be just ‘an agent of the state’, but also policy innovators. Whilst its policy capacity and ‘the ability to marshal the necessary resources, to set strategic direction, for the allocation of scarce resources to public ends’ (Painter and Pierre, Reference Painter, Pierre, Painter and Pierre2005: 2) is often curtailed and constrained through the power, political, and constitutional dimensions of state-local relations local governments have started to innovate across social policy areas (SMG, 2022a, 2024), particularly as both cities confronted, responded to, and felt the impacts of the worldwide pandemic.

Localised pandemic policy responses and impacts on critical human security in London and Seoul

The ways in which national governments have responded to and been impacted by the pandemic has been fairly widely reported (An and Tang, Reference An and Tang2020; Béland et al., Reference Béland, Hick, Moreira, Whiteford and Cantillon2021; Cook and Ulriksen, Reference Cook and Ulriksen2021; Dorlach, Reference Dorlach2023; Ku and Yeh, Reference Ku and Yeh2022), and not least in this special-themed section. The focus of the next section of this article is to contextualise and localise the pandemic experience to better understand the role of different tiers of government and city stakeholders, and local social welfare and social infrastructure in shaping and mediating constellations of human security and insecurity in times of turbulence. The impacts of the global pandemic and the policy responses to it have been uneven and differentiated nationally and locally, but there has been widespread recognition that it has been cities that have been particularly at risk, given that they are centres of commerce and mobility, densely populated, and hyper-connected (UCONN, nd). The pandemic has challenged the policy capacities and social infrastructure of cities to cope with and mitigate against systemic crisis. This localisation and specificity of a global phenomenon is particularly marked in the cases of the UK and South Korea (and Seoul and London in particular) where the speed of response and capacities for detection and response to the viral transmission through, for example, contact tracing systems and containment, were markedly different (Majeed et al., Reference Majeed, Seo, Heo and Lee2020; Hong et al., Reference Hong, Lariviere and Ko2025). In both Seoul and London, the pandemic placed further pressure on the already-overstretched public services, and urban and subnational governments were at the forefront of managing the Covid-19 pandemic crisis and economic consequences (Machin, Reference Machin2023). They were placed in the position of having to address the gaps in provision and social infrastructure, and the impacts of strategies implemented at national level through local initiatives during the pandemic (City Stakeholders L6, S5) as well as now having to address the ongoing threats to well-being and livelihoods of its residents, and weaknesses in the delivery of social services and systems of social protection (UN, 2020).

London recorded the highest age-standardised mortality rate with 85.7 deaths per 100,000 person, higher than any other region, with the local authorities recording the highest age-standardized mortality deaths involving Covid-19, all located in London boroughs (ONS, 2021), and in those boroughs with the highest levels of deprivation (Newham, Tower Hamlets and Hackney). Whilst the rapid rollout of the Covid-19 vaccination programme was key to the central government’s response to the pandemic, London’s vaccination rates at 86 per cent by January 2022 remained lower than the national average in spite of the introduction of mass vaccination pop-up clinics, walk-in pharmacies, and 24-hour jab-a-thons sessions (Mayor of London, 2022).

The first national lockdown in the UK was in March 2020, with workforce jobs falling by 229,000 in London between March and September 2020, with the greatest fall registered in the arts and entertainment, accommodation and food, and construction sectors. The national furlough scheme introduced by the UK government was supporting some 431,000 jobs in London at the end of October 2020 (HMRC, 2021), with take up in the capital higher than the national average, and three in four of the top 5 per cent of areas in terms of take up rates were London boroughs (GLA Economics, 2024).

In Korea, according to the KDCA (2022) 68 per cent of total confirmed cases occurred in the densely populated SCA, with Seoul having the highest incident rate of Covid-19 at the end of 2021 (followed by Gyeonggi-do and Daegu) (Lim et al., Reference Lim, Lym, Kim and Kim2022) causing the mayor to claim that Seoul was now in a state of emergency (SMG, 2021a). The Seoul Metropolitan Government was pivotal in identifying, coordinating, and filling public service gaps by leveraging its autonomy, resources, and local knowledge. The SMG implemented various initiatives to address specific local and regional challenges, including a relaxation in the criteria for accessing emergency relief assistance for households affected by Covid-19 (SMG 2022b. In addition, Shon (Reference Shon2021) highlights key local strategies including the rapid introduction of social distancing, enhanced contact tracing, and widespread testing and early detection. Whilst concerns were raised regarding pressure on hospital beds as confirmed cases began to rise and as the four municipal hospitals designated exclusively for infectious diseases in Seoul began to reach near capacity, additional facilities from both public and private hospitals were made available. Community treatment centre hubs were established for elderly people or those with chronic diseases, along with at-home, face-to-face treatment made available (SMG, 2021).

Across London, non-governmental sector and civic groups played a key role in coordinating volunteers and community support, services, and food aid in their local areas (City Stakeholder L2; Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Fransman and Bulutoglu2020) and in 2020 the Strategic Coordination Group was established to set strategy, objectives, and priorities for responding to the Covid-19 pandemic, with a key aim of coordinating different stakeholders and sectors across the city. In Seoul, the social economy sector, which under Mayor Park Won-soon had been well-financed and encouraged to expand, in 2020/21 was also able to mobilise and play an important role in supporting social enterprises with increased fiscal support (Stakeholder S6). More recently, the priorities of the city mayor have changed, and funding for this sector has been drastically reduced by between 40 and 90 per cent from 2022 to 2023.

The London Community Response Fund sought to support local initiatives and to get finance out to key frontline community, religious, and volunteer organisations who were central in galvanising support and drawing on existing cross-sector borough and city networks to provide food and support to vulnerable residents (City stakeholder L5), along with the repurposing of facilities and leisure centres as food distribution points

While nationally a £20 uplift per week to Universal Credit went some way to reducing economic and food insecurity, the pandemic also highlighted the important role played by Local Welfare Assistance which with slightly relaxed eligibility rules played a key role across London boroughs (London Councils, 2024) in bolstering the economic and financial security of residents in times of crisis, particularly for vulnerable and low-income households. Prior to the pandemic twenty-two London councils had local welfare assistance in place, with eighteen of those increasing funding to these schemes in response to the pandemic (Sustain, 2020), accompanied by an increase of 368 per cent in demand for hardship payments during lockdown resulting in the distribution of £53.4 million in emergency payments to residents in financial crisis. In addition, in London, social care, alongside the National Health Service, formed a vital part of the frontline response to the Covid-19 pandemic, and councils stepped up as direct providers and commissioners of social care services and main supplier of personal protection equipment (PPE) for care sector workers, which was in very short supply, as well as supporting people outside the care home settings (City Stakeholder L8).

In both cities Covid-19 had a disproportionate impact on ethnic minority and migrant communities as a consequence of lack of economic security, more limited access to benefits and sick pay, particularly for undocumented residents who had no access at all, unequal vaccine coverage (Im, Reference Im2020: Oskrochi et al., Reference Oskrochi, Jeraj, Aldridge, Butt and Miller2023), and particularly in Seoul, access to accurate Covid-19 information. Whilst varying levels of economic support were provided by national and local governments in South Korea foreign residents were initially excluded altogether or subject to stricter eligibility requirements, although as Im (Reference Im2020) explains, Seoul’s municipal government reversed this decision following pressure for the National Human Rights Commission of Korea. In March 2020, the Seoul Metropolitan Government provided 542.3 billion won (US$ 457 million) in emergency disaster relief to 1.6 million households, including 95,000 foreign households living and working in Seoul (SMG, 2020c) as well as forty designated places to support offline applications and issue documents needed for the application. Similarly in the UK, immigrant and asylum status, undocumented residents, and those on visas are subject to No Recourse to Public Funds (NRPF) and restricted access to support and public and healthcare services (Racial Justice Network, 2021). Normal benefit rules were not waived, but they were able to access some of the temporary Covid-19 schemes in 2021, and receive support from London local government as well as the voluntary sector. However, it was London’s residents from Black and South Asian communities who experienced the disproportionate effects of the pandemic (UK Health Security Agency, 2021).

Local social policy challenges to human security in post-Covid: Multi-scalar dynamics of insecurity and their localised intersection

This final sections of the paper explore some of the key urban and local social policy challenges in the post-Covid cities of Seoul and London emerging from this research and the implication for human security across different aspects of daily life, particularly in relation to economic (employment state, income/earnings, income support, and social mobility), food (access to food, purchasing power, state support), as well as environmental dimensions focusing on access to adequate and affordable housing and community (cohesion, social capital) (see Table 1, Column 1). Both London and Seoul have become iconic world cities and national signifiers of affluence and opportunity. However, they are also contexts and communities in which the contradictions of national welfare systems, urban political economy, and local social infrastructure are juxtaposed and exposed through patterns of social stratification, discrimination, insecurity, and constrained mobility. Commenting on the Korean welfare system Cho (Reference Cho, Chung and Gilbert2024:npn) argues that it is ‘…fragmenting, with weak linkages between institutions, gaps in coverage and low benefits’, and retains an expectation of and requirement for familial responsibility for extended kin when accessing social assistance programmes, when the reality is that for many this cannot be sustained or is simply absent. In Britain the welfare state has become less generous, more punitive with increased conditionality, and ‘…some of the most punitive sanctions in the world…’ (House of Lords, 2020: 5), and provides little by way of a safety net, social protection, or longer-term security with the House of Lords (2020) report stating that Universal Credit wasn’t working (House of Lords, 2020). Local government in the UK and in major cities in Korea such as Busan and Seoul have introduced initiatives to enhance social infrastructure, local social policy and social welfare measures and the Seoul Safety Income policy, for example, aims to strengthen the social safety net and address some of the ‘blind spots’ in the welfare system (Stakeholder Interviews S4 and S5, SMG (2022a and 2024). However, these measures have been accompanied by increasing segmentation and high income inequality in labour markets in both cities, particularly marked in the Chaebol-centred Korean political economy (Cho, Reference Cho, Chung and Gilbert2024) and in the context of poverty and constrained mobility and access to affordable housing, and changing demographics.

Labour markets and social stratification

‘Fragmented labour markets’ (Bekker and Leschke (Reference Bekker and Leschke2021) highlight the large and growing diversity in employment relationships in both Seoul and London, indicating a shift beyond binary divisions to a more nuanced interpretation of the complexity of the labour market structure and the relationship between income, systems of social security and other social infrastructure, risk, and insecurity. It is increasingly evident that insecurity is inherently built into labour markets and as the ILO argues ‘insecure forms of work are often “traps” rather than “stepping stones”’ (ILO, 2016: 26). Around 6 per cent of workers in London are in insecure employment, with the figure rising between the financial crisis 2008 and the pandemic, but falling sharply during the pandemic. The proportion of workers in London on zero-hours contracts has risen dramatically over the last decade from one per cent to around 3 per cent of the total. In London, around one in sixteen of everyone in work is employed in a job with a temporary contract, working through an employment agency, or self-employed in occupations considered insecurity. Whilst it is clear that for some such insecure ‘flexible’ work can be seen as beneficial, with some workers (particularly well-qualified professional workers) compensated very well for this insecurity. However, there are groups for whom insecure employment is likely to be more prevalent limiting access to social rights and benefits. More than one in six people, aged —sixteen to twenty-four, were in insecure jobs in 2023 with Black, Pakistani, or Bangladeshi and Mixed ethnicity Londoners and Muslim Londoners in employment having higher rates of insecure work than other groups (London Datastore, 2025).

Whilst there has been a slight reduction in the number of irregular workers in Seoul and Korea more generally since the record high of 2022, nevertheless it still represents some 37 per cent of salaried workers. In Seoul, it is increasingly groups such as young people in their twenties and thirties, women, older people, and those with lower education levels who are likely to bear the prolonged impact on the economy and society of Covid-19 and more likely to be in insecure employment. Many of the ‘Covid-19 youth generation’ remained unemployed (job seekers, civil service exam candidates, discouraged young workers, for example) (City stakeholder S7), and in the transition phase from school to the labour market, finding themselves in a policy blind spot, unable to receive policy support from the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Employment and Labour immediately after graduation. The Seoul Metropolitan Government has been focusing on expanding support for young people, including the Seoul 2025 Comprehensive Youth Support Plan to be fully implemented by 2025 (SMG, 2022b).

It is widely recognised that gender constitutes an influential dimension of urban identity, social division, and every day life, and in the ways that men and women utilise urban space (Cho and Song, Reference Cho and Song2022; Cho, Reference Cho2022) and interact with social infrastructure and local social policy, particularly with regard to the division of labour (paid/unpaid employment) and reproduction (Peake, Reference Peake2020; Gabauer et al., Reference Gabauer, Knierbein, Cohen, Lebuhn, Trogal, Viderman, Gabauer, Knierbein, Cohen, Lebuhn, Trogal and Viderman2021). The gender employment gap in labour force participation in South Korea decreased from 22.9 per cent in 2014 to 16.6 per cent in 2024 but is still substantial (KOSIS, 2025). In Seoul, women’s labour force participation rate was 55.6 per cent, which was 15.2 per cent lower than that of men in 2023. In the UK, 72.1 per cent of women were employed in 2023, a slight decrease from 2019 (72.4 per cent), with the gender pay gap substantially less than in Korea and Seoul, although still significant with female employees earning on average 11.9 per cent per hour less than men. In Korea, women earn 68.4 per cent of the wages earned by men (World Economic Forum, 2023), as the percentage of women with non-regular jobs is 16.4 per cent higher than their male counterparts (47 per cent).

Poverty, social isolation and food insecurity

Whilst both Seoul and London have committed to the Global Network of Age-Friendly Cities and Communities (WHO Global Network For Age-Friendly Cities And Communities – Global Cities Hub) poverty, isolation, and insecurity amongst older people remain key policy challenges post-Covid-19, particularly in Seoul and Korea more generally (Stakeholder interviews S4 and S5). Elderly households aged 65 years and older made up 22 per cent of all households in Seoul, with 32.1 per cent composed of single households, of which the vast majority (70.2 per cent) are female single-person households, and 29.8 per cent men (SMG and The Seoul Institute, 2023). The temporary employment rate for those aged 65 and over in Korea is the highest of OECD countries at 69 per cent (compared to 38.1 per cent in Japan), with the poverty rate for people aged 65 or older reached 40.4 per cent in 2020 in Korea (OECD, 2021).The prevalence of food insecurity among low-income households in Seoul was evident prior to the pandemic but increased during the crisis, particularly amongst the elderly (Kang and Lee, Reference Kang and Lee2022).

In comparison, in the UK in 2020/21 15 per cent of those sixty-five and over lived in relative poverty (1.7 million people). However, London has the highest level of ‘pensioner poverty’ in England, and the use of foodbanks has become embedded in local communities (Sustain, 2020; London Assembly, 2023) highlighting the failure of both national and local social policy to adequately protect against economic and food insecurity and an overreliance on the voluntary sector to fill the gaps in the social safety net. A third of Asian older people, and just under a third of Black British older people in the UK, lived below the poverty line compared to 16 per cent of white pensioners (Age UK, Reference Age2021)

Whilst policies in both cities have sought to address poverty, insecurity andsocial isolation in later life in the context of ageing societies, particularly in South Korea (Kim and Kim,; Reference Kim and Kim2024), old age poverty remains high in South Korea relative to other OECD countries, and pensions the least universal (Byun, Reference Byun2024). This is occurring in a country that is experiencing one of the world’s lowest fertility rate. The birth rate in Seoul has decreased from 1.059 (1.297 nationally) in 2012 to 0.626 (0.808) in 2021. Whilst there was a slight increase recorded nationally in 2024 (KOSTAT, 2025), Seoul recorded a further decline the birth rate reinforcing its status as a potential ‘super-aged city’. In the UK the national figure for 2021 was 1.53 births per woman and 1.52 for London, with the city experiencing a further decrease to 1.35 in 2023 (ONS, 2021, 2024) contributing to London being the only major city in the UK that is getting older (McCurday, Reference McCurdy2025). Policies to address declining fertility rates in Korea have tended tofocus on financial incentives and ambitous policy reforms with the introduction of free childcare and early education subsidy (Lee, Reference Lee2021). Whilst these have clearly met with some success, there has been much less attention on cultural and local social infrastructure, and recognition of everyday practices in the city and their gender implications, particularly relating to the tradition of long working hours and lack of flexibility, and have remained unsuccessful in encouraging women into the labour market (Stansbury et al., Reference Stansbury, Kirkegaard and Dynan2023).

Housing (in)security and constrained mobility in Seoul and London

Housing is central to security and well-being, and lack of adequate housing can be a driver of inequality, poverty, ill-health, isolation, and insecurity (Lee and Han, Reference Lee and Han2024; Hochstenbach et al., Reference Hochstenbach, Kadi, Maalsen and Nethercote2025). In both Seoul and London obtaining affordable, good-quality housing is increasingly a struggle for many with escalating house prices, rents, and limited availability across tenures and a polarisation of housing conditions and was highlighted as a key challenge by almost all city stakeholders involved in this study across the two cities.

Housing, and particularly home ownership, is not only integrated within macroeconomic processes such as financialisation (Aalbers, Reference Aalbers2017), an investment vehicle and potential source of wealth accumulation, it is also located within national housing systems and shaped by policy regimes, interest rates and land use regulations. Housing is also physically embedded within neighbourhood and community contexts that are shaped by particular local social, policy, and economic contexts and infrastructure, as well as demography and spatial conditions. As Forrest (Reference Forrest2008: 180) explains ‘the housing market is thus unpredictable and uncertain but of enormous significance for individual households and for the global economy.’

In Seoul 43.5 per cent of households were owner occupiers and in London 53 per cent in 2020. In Korea, house price-to-income ratio was at a multi-decade high during the pandemic with a strong demand for real estate surpassing housing supply, particularly in Seoul where rises in property prices have far outpaced wages (KOSTAT, 2024). In London, average house prices now represents 12.5 years of average annual earnings, and to afford the average private rent London households need to spend 40 per cent of their income (Harding et al., Reference Harding, Cottell, Tabbush and Mahmud2023). The London Mayors London Housing Strategy published in May 2018 recognised and sought to tackle London’s housing crisis focusing on more and better quality affordable housing and inclusive neighbourhoods (Mayor of London, 2018). In Seoul too, the ‘housing crisis’ has been a critical and central issues in both the presidential election in 2022 and the Seoul mayoral election in 2021 with Oh Se-hoon recognising the constrained social mobility of young people and the constraints on buying a home due to high house prices and pledged to make Seoul a ‘city of hope’ through the ‘Seoul Vision 2030’ (SMG, 2021b) and the increase in supply of low-cost housing.

In the UK some 16 per cent of housing stock is social rental housing provided either by the non- or limited profit housing association sector or is directly owned and managed by local authorities. This compares to approximately 9 per cent in Korea (an increase of over 2.5 per cent since 2010) where 70 per cent is provided by national governments, 18 per cent by regional and/or municipal authorities and public agencies, and 12 per cent by for profit and other providers (IMF, 2022; OECD, 2024). The Seoul Metropolitan Government began providing public housing units from 1989. There are approximately 271,253 public rental units in Seoul, 140,000 of which were provided between 2012 and 2017 under Mayor Park Won-Soons leadership. Initially the housing was built on city-government-owned land and constructed by city contracted companies, and managed by Seoul Housing and Communities Corporation. From the late 1990s private sector development was encouraged and incentivised with new ‘affordable’ housing provided below market rent, a trend which continues today with the expansion of public housing involving outsourcing to private developers for mixed use development involving both public and (substantially more) private rentals and retail space (Kim and Park, Reference Kim and Park2020). New initiatives have included ‘Shift’ (Seoul Housing shift), a programme aimed at converting existing homes into public rental housing and supporting cooperative housing projects for young people and the elderly.

In London, local authorities and housing associations owned and controlled a total of 793,250 low-cost rented homes in 022, a very slight increase of 0.3 per cent on the previous year; 10,270 council homes were started by London boroughs in 2022/23 with Greater London Authority support representing the highest number of council housing starts in London since the 1970s. It has been argued by Beswick and Penny (Reference Beswick and Penny2018: 612) that in order to facilitate more homes, including affordable homes a process of financialised municipal entrepreneurialism has emerged in London whereby ‘the state is no longer merely the enabler – limited to providing strategic oversight of the private sector – but financialises its practices in a reimagined commercialised intervention, a property speculator’. In London, this involves establishing arm’s length housing companies, loss of democratic responsibility (Christopher, Reference Christophers2019) and the replacement of existing public housing stock with mixed tenure developments (City Stakeholder L4). However, Christopher (Reference Christophers2019: 581) points to the financial interdependence of local authorities, as well as their ever expanding statutory responsibilities and the ‘devolved austerity’ experienced by local authorities as they sought to maintain services. By 2020, London boroughs spending power per person had fallen by 37 per cent in real terms since 2011 in the context of increasing demands on their services and emerging financial crisis (City Stakeholder L3). So whilst there is potential for increasing local state capacity and interventions in the housing market the strategy is failing to address inequalities and is localising and embedding risk and insecurity in the social infrastructure of the city. It would also appear to be a strategy that has had limited success in promoting and supporting an inclusive city. In March 2023, there were 62,000 homeless households living in temporary accommodation (either bed and breakfast or private rentals) arranged by London boroughs, an increase from 56,430 to March 2022 (Trust for London, 2024), with 10,053 people seen sleeping rough in London in 2022/23 an increase of 21 per cent from 2021 to 2022.

Responses to housing need, as a critical social infrastructure and key to human security particularly in turbulent times, have barely scratched the surface. Housing policy in both Seoul and London faces several significant challenges that have severely impacted its effectiveness in providing affordable, accessible, and sustainable housing for residents.

Conclusion

The pandemic has highlighted the importance of recognising context and the role of local social policy, and supporting and mobilising local state capacity and social infrastructure for addressing systemic risk and striving for inclusive and sustainable cities. Cities, urban governance, and social infrastructure are increasingly entangled within the contradictions and tensions between urban boosterism, entrepreneurialism, and financialisation on the one hand and uneven development, access and inequality, equal opportunities, and constrained social mobility on the other. Utilising and integrating a critical human security, multi-scalar governance and territorial matrix enabled us to illuminate and contrast these webs of entanglement and consider the implications for well-being and everyday life in Seoul and London. In the context of systemic crises and a global pandemic, fragmentation and inequality, and the erosion of traditional sources of security, welfare architectures and local state capacity are poorly equipped to address contemporary urban and societal challenges.

Whilst the policy responses to the pandemic were different in Seoul and London, local governance in both cities was relatively slow to recognise and respond to the needs of diverse communities and the uneven impact of the pandemic and responses to it. The Covid-19 pandemic drew attention to the lack of mainstream welfare safety net for different groups of people, particularly migrant populations, as well as the inadequacies of existing national and local social policies and social protection measures and their racialised and gendered dimensions. However, we have also sought to demonstrate that local welfare and social infrastructure are important components of human security and social protection against systemic crisis and new social risks, and are particularly effective when local systems are financially sustainable and integrated into a well-coordinated vertical and horizontal multi-scalar frameworks (Constanzo and Maestripieri, Reference Constanzo, Maestripieri, Kazepov, Barberis, Cucca and Mocca2022). Recognising and supporting the important role that potentially agile and innovative urban stakeholders as front line responders can play to build and enhance local social infrastructure could be a driver for long-term human security and sustainable cities and key area for further investigation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of the Economic and Social Research Council Grant No. ES/W010739/1, and the Global Development Institute for Public Affairs, Seoul National University, South Korea. We would also like to thank those who gave up their valuable time to participate in and contribute to this project.