Introduction

An image of the Belarusian Nobel Prize-winning author and key opposition figure Svetlana Alexievich surrounded by European diplomats at her home in Minsk went viral in September 2020.Footnote 1 This gathering was a way for these diplomats to manifest their solidarity against the crackdown on protesters following a disputed election. However, the gathering can also be read as an example of diplomats displaying care, here most literally providing Alexievich with physical protection from police harassment. Diplomats responded to a demand from Alexievich for protection. Subsequently, they appeared at her apartment to demonstrate to the Belarussian authorities and the international virtual audience that they would not allow anyone to hurt Alexievich and that she was in their care. As this article will show, paternalism is a concept often used to make sense of various relations in contexts of international power inequalities. While a fruitful concept, I argue that the notion of paternalism does not suffice to make sense of the many types of diplomatic engagement with individuals and civil society organisations (CSOs) abroad. Thus, inspired by feminist theorising on care work and maternal labour, this article examines the practice of diplomatic engagement with civil society actors abroad through the concept of maternalism.

The work of frontline diplomats, i.e. envoys placed abroad, is multifaceted and often entails interactions with civil society actors. Representing a sending state, negotiating, reporting about a receiving state, and promoting friendly relations are all fundamental elements of diplomatic work listed in the 1961 ‘Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations’.Footnote 2 In all of these elements, relations with civil society actors in the host state are crucial. Indeed, diplomats have long engaged with civil society actors, albeit this engagement has taken very different forms depending on the context. For instance, in an undemocratic setting, connecting with oppositional civil society may be part of a state’s strategy to promote democracy abroad. Contacts with civil society in a likeminded state might also be a cultural activity, or local civil society might be a crucial partner for diplomats in peace negotiations. The realisation that civil society is a key actor in cooperation for foreign service is visible in foreign policy action plans,Footnote 3 where different forms of interactions with civil society actors appear.

Given that diplomacy–civil society relations are central to diplomatic work, these relations must be closely examined and properly theorised. Being largely neglected in mainstream realist theorising, even many diplomacy scholars have not paid sufficient attention to how diplomats interact with civil society actors. This article thus has two sets of aims, one theoretical and the other empirical. Theoretically, it introduces a new concept – maternalism – into the analytical toolbox of diplomacy studies. While the Bourdieu-inspired ‘practice turn’ has entailed a recalibration of the study of diplomacy towards the mundane and the everyday work of diplomats, I claim that we need more notions that will help us understand these everyday practices in light of structural power inequalities. In this endeavour, building on the established term of paternalism, I follow feminist theories of motherhood and the ethics of care to reflect on unequal relations that are not marked by financial dependency or military power. For diplomacy–civil society relations beyond the context of military intervention and/or democracy promotion though foreign aid, I introduce the notion of maternalism as a distinct set of practices towards civil society actors abroad. When diplomats nurture as well as listen and respond to the demands of local CSOs, they act as archetypical mothers.

The second set of aims is empirical. The article elucidates diplomacy–civil society interactions that have been largely ignored in the literature on diplomacy. I analyse how diplomats abroad, i.e. those who implement and shape foreign policy on site,Footnote 4 engage with civil society actors in the host country. More specifically, this article studies how diplomats from liberal Western states interact with civil society actors in the semi-peripheral countries of Poland and Hungary, whose governments represent the vanguard of illiberalism in post-Cold War Europe.Footnote 5 Geoffrey WisemanFootnote 6 has argued that diplomacy–civil society relations are especially important in adversarial contexts in which traditional state-to-state contacts might be less effective. Hence, the sample for this study captures both international power inequalities and ideological adversity.

The data come from interviews with 15 ambassadors representing seven states (Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands) stationed in Warsaw and Budapest in 2019–2020. In such illiberal contexts, a nuanced approach to civil society is needed from both scholars and diplomats. In the process of de-democratisation, due to various government actions,Footnote 7 the civil societies within these states tend to split into two polarised camps – one supporting and one opposing the changes, with a vanishing neutral ground.Footnote 8 One important finding in this article is that engagement by diplomats representing liberal states differs considerably depending on whether CSOs support illiberal changes or oppose the regime. While maternal care is exhibited toward liberal CSOs, engagement with CSOs supporting illiberal governments in Poland and Hungary is nearly non-existent, showcasing maternal control. The concrete research question guiding the analysis reads: what forms does diplomatic engagement with civil society adopt?

The rest of this article is organised into five sections. The first section examines various strands of the diplomacy literature for research concerned with civil society. It concludes that while a systematic theorisation of diplomacy–civil society relations is lacking in the extant literature, civil society has been acknowledged as an important actor by diplomacy scholars. The subsequent theory section engages with the notion of paternalism as well as feminist theorisation of motherhood and the ethics of care to establish a basis for the introduction and use of the concept of maternalism in the study of diplomatic engagement with civil society and in International Relations more broadly. Maternalism is proposed as a complementary heuristic to paternalism, which is helpful in capturing different modes of engagement between unequal actors in international politics, centring around distinct practices of care and control. Next, the case selection and methods applied in this article are discussed. Subsequently, the analysis section empirically illustrates the utility of the notion of maternalism in the study of diplomacy–civil society relations. It explores how diplomats engage with civil society. Finally, conclusions present the implications for the study of diplomacy and specify avenues for future research.

Prior literature on diplomacy and civil society

A focus on civil society is not very common in academic scholarship on diplomacy. Diplomacy research has traditionally studied peaceful interactions among state actors, leaving civil society outside the scope of interest.Footnote 9 The literature has struggled to keep up with the changing practices of diplomacy, which are no longer restricted to a closed circle of diplomats. As diplomacy increasingly has come to involve other actors and other types of interactions, scholarship has invented a plethora of labels to capture these interactions (e.g. new ‘tracks’ of diplomacy,Footnote 10 ‘NGO diplomacy’,Footnote 11 ‘polylateral diplomacy’,Footnote 12 or ‘network diplomacy’Footnote 13). Civil society organisations have also been studied as active parts of intergovernmental negotiations and international orders in various specific issue areas, such as environmental policy,Footnote 14 land mine regulations,Footnote 15 human rights, and international security.Footnote 16 By stressing that the actors and venues engaged in diplomacy multiply, these contributions highlight that civil society actors occasionally perform diplomatic functions. They thus expand the definitional borders of diplomacy and introduce a juxtaposition between the diplomatic and civil society spheres.

There is also ample literature on the tasks that have been added to the diplomatic repertoire. One such task is ‘the projection of the diplomat’s country into the host nation’.Footnote 17 Although there is an underlying assumption that public diplomacy, i.e. ‘the conduct of foreign policy by engagement with foreign publics’,Footnote 18 is directed towards (and occasionally executed by) civil society actors,Footnote 19 the theorisation of diplomacy–civil society relations that public diplomacy actualises has been generally neglected.Footnote 20 Interactions with civil society as an important dimension of diplomatic work have been highlighted by Wiseman,Footnote 21 who dubbed them ‘polylateral’ diplomacy. Such interactions are, for instance, rather common in the United Nations (UN) system.Footnote 22 WisemanFootnote 23 has observed that diplomatic contacts with civil society are particularly important in adversarial contexts because such contexts implicate obstacles, such as unreliable sources of official information, in traditional state-to-state contacts. This realisation corroborates observations from what might be termed the dissident diplomacy literature. This literature mainly consists of (auto)biographical accounts of individual ambassadors’ engagement with oppositional groups in undemocratic contexts during the Cold War.Footnote 24 While more analytical approaches distinguishing various forms of engagement are needed to create a systematic understanding of patterns of diplomatic interactions with CSOs, the literature on dissident diplomacy clearly shows that diplomatic engagement with civil society is not a new phenomenon.

An influential theoretical development in diplomacy studies originates in the practice turn.Footnote 25 One of the contributions of this development is the focus on various micro-practices that constitute diplomacy – ‘examining what diplomatic practitioners do and how they do it’.Footnote 26 The practice turn also entails increased interest in the work of frontline diplomats, i.e. those placed at embassies.Footnote 27 Andrew Cooper and Jérémie Cornut claim that ‘diplomatic practices at the frontlines epitomise international politics’ and that ‘studying the frontlines should thus be an obvious starting point for those interested in international politics’.Footnote 28 One key dimension of frontline diplomacy is ‘publicity and connection with non-state actors’.Footnote 29 With their focus on revealing the links between the everyday work of diplomats and a perspective on world politics, not much attention is awarded to the actual practice of connecting with non-state actors or a theorisation of these connections. In this regard, Cornut’s earlier studyFootnote 30 provides more guidance. It is centred around diplomatic knowledge production at embassies, for which information gathering from various non-state actors is crucial. Therefore, in his analysis, civil society actors are viewed as local knowledgeable actors who contribute to the knowledge production of diplomats. A recent article by Maren HofiusFootnote 31 further develops this line of thought, concurring with Cornut’s claim that informal networks and contacts with CSOs are crucial to the making of evaluative judgements by frontline diplomats. With an interest in knowledge production and standards of competence in times of crisis, Hofius concludes that the diplomats in her analysis relied on an ethics of care for the host state’s citizens; she defined this approach as a practical judgement in context sparked by the recognition of the ‘needs of those suffering’.Footnote 32

In sum, these studies acknowledge the importance of diplomatic contacts with civil society and advance the appreciation of the work diplomats do to establish and uphold those contacts. Building on these observations, I attempt in this article to provide a systematic theorisation of that engagement. It is apparent that the diplomacy literature already to some extent recognises the role of CSOs in diplomacy, often as part of the discussion of the changing character of contemporary diplomacy. However, we still know little about how these relations are shaped and how diplomats interact with actors in civil society, especially in bilateral contexts. Acknowledging that resident missions abroad in foreign capitals remain vital cogs in diplomatic machinery,Footnote 33 this article analyses how frontline diplomats interact with CSOs of the host country. In the theoretical discussion below, I draw inspiration from the practice turn in diplomacy scholarship and its focus on the everyday work of diplomats. I expand this attention to frontline diplomacy, with a focus on the structural power inequalities in the international setting that shape diplomatic interactions with other actors.

Because of its limited focus on relations with civil society, previous scholarship on diplomacy has rendered a relatively unnuanced picture of civil society. First, civil society is often left undefined. In this paper, civil society is understood as the sphere of associational life, operationalised as a set of organisations engaged in collective activities in various ways detached from and/or interconnected with the domains of the state, family, and market.Footnote 34 Following a distinction common in the civil society literature, I refer to civil society organisations (CSOs) as encompassing both formal organisations (usually dubbed NGOs) and less formal organisations (such as social movements and other non-registered civil society groups).Footnote 35 Acknowledging that there is enormous variation among CSOs, in this article, focusing on diplomatic engagement with civil society, I will only distinguish the types of CSOs that diplomats highlight in the interviews.Footnote 36 Second, in diplomacy studies, a dissident or liberal orientation of civil society is often assumed, sometimes excluding ‘bad non-state actors’ a priori from its scope of interest.Footnote 37 Drawing on debates in civil society scholarship, I argue that this normative move is highly problematic. While some CSOs support liberal democratic values, others profess illiberalism. In civil society research, the multifaceted nature of civil society is captured by discussions of ‘bad’ or ‘uncivil’ civil society.Footnote 38 A study of diplomatic engagement with civil society needs to inquire about contacts with various kinds of CSOs, leaving behind the normative assumptions about the liberal character of civil society writ large.

Setting the theoretical foundation: Maternalism and diplomacy

Inspired by an emerging scholarly interest in what frontline diplomats do and seeking to close apparent gaps in the scholarship on diplomacy and civil society, this article introduces an initial theorisation of diplomacy–civil society relations in bilateral contexts. I posit that to fully grasp these relations, especially in contexts that are characterised by power/status inequalities between the sending and receiving states, the notion of paternalism is insufficient and should be complemented by the notion of maternalism. Adding the notion of maternalism and establishing what practices constitute both maternalism and paternalism, I expand the types of relationships with unequal others that are in the purview of diplomacy studies. The various concrete actions and engagements that diplomats undertake on the ground with respect to civil society actors can then be placed on a continuum from paternalistic to maternalistic. These conceptual lenses give us a deeper understanding of diplomatic work. Below, I discuss the tension between care and control in unequal relations and how this tension is expressed in paternalism and in maternalism.

Many unequal relations in the international domain and beyond are marked not only by control, i.e. the ability to influence or direct another party’s behaviour but also by care, i.e. the provision of what is needed for that other party’s welfare and protection.Footnote 39 Hence, both control and care highlight the hierarchy between one controlling and caring party and one that is cared for/about and controlled. As will become clear below, control and care can take many different forms. While control is a given topic in the study of international relations, care is much less prevalent. Feminist theories of care ethics introduce the idea that relations and responsibilities for care are central to human life and that care is a public value that must be negotiated at various levels, from the household to the international community.

Paternalistic control and care

In International Relations, the notion most commonly used to describe unequal relations combining control and care is paternalism.Footnote 40 Building on this combination, Michael Barnett defines paternalism as ‘the substitution of one person’s judgment for another’s on the grounds that it is in the latter’s best interest’.Footnote 41 Barnett refers to ‘moral intuitions’Footnote 42 in his discussion of paternalism, even though it is clear that this notion is based on sex-role stereotypes and binary ideas about men’s and women’s unequal conditions – ideas about how fathers (and mothers) control and take care of their children in the specific context of the West in the 20th century.Footnote 43 Barnett’s influential theorisation is modelled on the stereotypical role of a father who treats other social actors as children, disrespecting their competence and autonomy.Footnote 44 Barnett himself mentions the concern that paternalism ‘might contain various unhidden biases … an obvious worry is that the concept is gendered, and should be substituted with a more gender-neutral concept’.Footnote 45 While linguistically queering relations of care and control might indeed be fruitful, my contribution in this article is rather to make the gendered origins and language of paternalism explicit by introducing a distinction between paternalism and maternalism. This approach does not mean that the notion of paternalism (and maternalism) is based on essentialising assumptions about the differences between men and women. Paternalism includes practices stereotypically associated with men, and maternalism includes those associated with women;Footnote 46 however, it does not suggest that only (and all) men act paternalistically and only (and all) women act maternalistically. Hence, I follow critical feminist theorists by dissociating paternalism from men and maternalism from women.Footnote 47 Paternalistic and maternalistic practices can be embodied to differing degrees by various individuals and institutions, and the specific gender pattern of this embodiment is an empirical question.

Building on the important contribution of Barnett, I introduce the distinction between paternalism and maternalism, constructing extreme forms of paternalism and maternalism as two opposites on a continuum of unequal relations in the international domain. In this sense, I am inspired by Barnett’s conceptualisation of paternalism as composed of a tension between care and control, but I introduce a distinction between paternalism and maternalism and place them on a continuum. On one end of the spectrum, I put extreme forms of coercive paternalism, expressed through physical strength, economic resources, and emotional detachment. According to this imaginary, control in paternalism consists of the imminent threat of coercion, for instance, when one party threatens to launch military intervention or when it exercises economic power, e.g. through sanctions or (threat of) withdrawal of foreign aid. Such paternalistic relations entail dependency, with one party being physically and economically stronger. Barnett arguesFootnote 48 that expressions of paternalism have shifted over time, based on the type of power exercised – from more directly coercive means of control to control based on epistemic means of manipulation of information. This ‘paternalism lite’Footnote 49 will be found further from the edge of the paternalism–maternalism spectrum and, as long as the relation is based on the paternalist imposing their judgement about what is the best interest of the other party, it is found on the paternalism side of the continuum. By adding maternalism, discussed below, with its distinctive sets of practices, I extend the continuum of relations characterised by care and control, with neglectful maternalism occupying the other end of the spectrum.

The element of care in paternalism takes the form of acting in the presumed best interest of others. In this sense, paternalism is self-centred, limiting the other’s self-determination by ignoring their ability to define what they need and want.Footnote 50 It is ‘an usurpation of someone else’s right to decide for himself’.Footnote 51 Thus, this form of care is unresponsive, since the powerful party defines the needs of the other. By default, such care is not attuned to the distinctive demands of different others. Like that of stereotypical fathers, paternalistic care is distant, as it provides physical and economic security but does not showcase emotional attachment. While Barnett is careful to discuss the normative wrongs that can be part of paternalism, he posits the care component in paternalism as benevolent: ‘a necessary condition [for paternalism] is that the subject be motivated, in whole or in part, by compassion, care, and benevolence’.Footnote 52 I follow Uma Narayan’sFootnote 53 observation that ‘relations [of care] can, and often do, become relations of domination, oppression, injustice, inequality, or paternalism’.Footnote 54

While built on the tension between control and care, the study of paternalism in the international domain gives epistemological priority to the element of control. For instance, Barnett introduces the volume on Paternalism beyond Borders by stating that ‘we [authors of the chapters] are all interested in the relationship between care and control. Although what counts as care is largely left unexplored, what truly distinguishes the chapters is how they understand the workings of power, both conceptually and historically.’Footnote 55 The various conceptualisations and expressions of power and control lead scholars to multiply the use of adjectives to describe paternalisms with some more benign variants, such as paternalism lite, soft paternalism, means paternalism, or weak paternalism.Footnote 56 In this article, instead of multiplying new declinations of paternalism and risking overstretching the concept, I introduce the related concept of maternalism. While indebted to Barnett for his rich and in many empirical contexts very useful notion of paternalism, the intention behind this article is to remain focused on relations marked by the tension between care and control while putting analytical effort into the element that has not been developed sufficiently in the literature on paternalism, i.e. care. This approach will hopefully help identify other types of international practice that could easily be overlooked if we only used the notion of paternalism.

Maternalistic care and control

I argue that the above-described notion of paternalism does not capture the whole spectrum of unequal relations marked by the tension between care and control. The move of differentiating maternalism from paternalism by linguistically gendering the discussion is consequential. We live by the metaphors we use. There is no reason for a father figure to occupy the entire spectrum of ‘parenting’. Here, I share Amanda D. Watson’sFootnote 57 contention that there is value in keeping the language of motherhood for feminist theorisations of the international.Footnote 58 Apart from semantics, I argue that the two concepts direct the analysis to different practices. Barnett, in his short comment about the risk of gender biases in paternalism,Footnote 59 mentions maternalism as a possible substitute for paternalism. He refutes such a solution, arguing that maternalism, more closely associated with the notion of ethics of care, loses sight of the tension between care and power, or, if it does include such a tension, becomes equivalent to paternalism. I disagree. Making explicit use of gender stereotypical references and building on feminist theories of motherhood and the ethics of care, I associate maternalism with distinct practices of care and control in international relations.

‘Maternalism’, to the best of my knowledge, has not been used in the study of international relations but can be found in other disciplines. For instance, maternalism in the analysis of domestic politics was first applied by feminist historians to explain the development of the welfare state,Footnote 60 referring to the social mobilisation of women as mothers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. More recently, maternalism has been discussed as an alternative to paternalism in medical ethics,Footnote 61 where maternalism captures a different kind of medical worker–patient relationship associated with intimate knowledge and emotional attachment. I build on this latter intervention to elaborate on the notion of maternalism as a specific form of engagement with others in the international domain, one that is distinct from paternalism. Unlike medical workers, diplomats do not have a professional mandate or obligation to provide care, even if consular diplomacy is sometimes understood through the lens of ‘duty of care’.Footnote 62

To develop the element of care in maternalism, I rely on feminist thought. Carol Gilligan’s early workFootnote 63 sparked ample feminist scholarship on the ethics of care, and in related research, Sara RuddickFootnote 64 initiated a strand of feminist thinking on motherhood. Care highlights ‘the compelling moral salience of attending to and meeting the needs of particular others for whom we take responsibility’.Footnote 65 Similarly, mothering is theorised as a response to children’s needs, one that shapes and is shaped by practices of global politics.Footnote 66 ‘Mothers are people who see children as “demanding” protection, nurturance, and training; they attempt to respond to children’s demands with care and respect rather than indifference or assault.’Footnote 67 Responsiveness is central to maternalistic care and absent from paternalistic care.

Hence, rather than assuming to know what is best for the other, maternalism relies on listening, i.e. respect for the self-determination of the other and sensitivity to their specific needs. This sometimes entails acceptance of the choices and decisions of the other, even if they do not align with the preference of the caregiver. In an extreme form, responsiveness can border on negligence, for instance when the caregiver chooses not to interfere in the other’s self-harming actions. Just as with coercive paternalism, such neglectful maternalism is situated on the outer edge of the paternalism–maternalism continuum. Otherwise, listening is a sign of attentiveness to ‘the distinctiveness of others in their concrete circumstances and the difficulties they face’.Footnote 68 Thus, maternalistic care will be adapted to the concrete other. Building on the various ethical elements, sometimes called ‘caring values’, which are specified in the literature,Footnote 69 I identify maternal care as giving and nurturing life, i.e. ‘enabling a child to survive and thrive’,Footnote 70 which entails nurturing and nourishing the other. Just as fathers have, mothers have specific resources at their disposal that mark the inequality of their relationship with children. Instead of economic resources and physical strength that stereotypical fathers possess, mothers stereotypically rely on emotional resources.Footnote 71 In the study of international politics, the domain of emotions is not always easy to capture, however. Ruddick provides guidance here: ‘Although maternal work is often entrenched in passion and … is provoked and tested by emotion, the idea of work puts the emphasis on what mothers attempt to do, not on what they feel.’Footnote 72 Thus, the investigation should not be focused on what feelings consist of in the maternalistic relation but on emotional labour as such.Footnote 73 Maternalism is often a long-term commitment in which trust can develop. At times, this long-term commitment leads to interdependency, for instance, in the form of emotional attachment, where the distinction between caregiver and care receiver becomes porous.Footnote 74 Interdependency highlights ‘the fact that caregivers too are vulnerable, needy and sometimes incompetent’.Footnote 75

Maternalism is also expressed through particular practices of control. Theorists of motherhood stress that there is nothing inherently peaceful in being a motherFootnote 76 and that mothers ‘are not always patient, kind or nurturing; mothers can be violent toward their children’.Footnote 77 The long-term commitment of maternalism can entail emotional dependency of children, who can be abused. Maternal control will be visible in the threat of abandonment and in (emotional) freezing out, which, given the close, attentive, and responsive relation, can be very hurtful. When mothers choose not to engage with their children, withholding expressions of care, they exercise control.Footnote 78 Selective distribution of care, i.e. favouring some children over others,Footnote 79 is also an expression of maternal control. Moreover, while in principle other-centred, it is still at the will of the mother to respond to the needs of her children. Hence, mothers define the conditions of the engagement and can withdraw from it.

Analytical framework: Practices of paternalism and maternalism

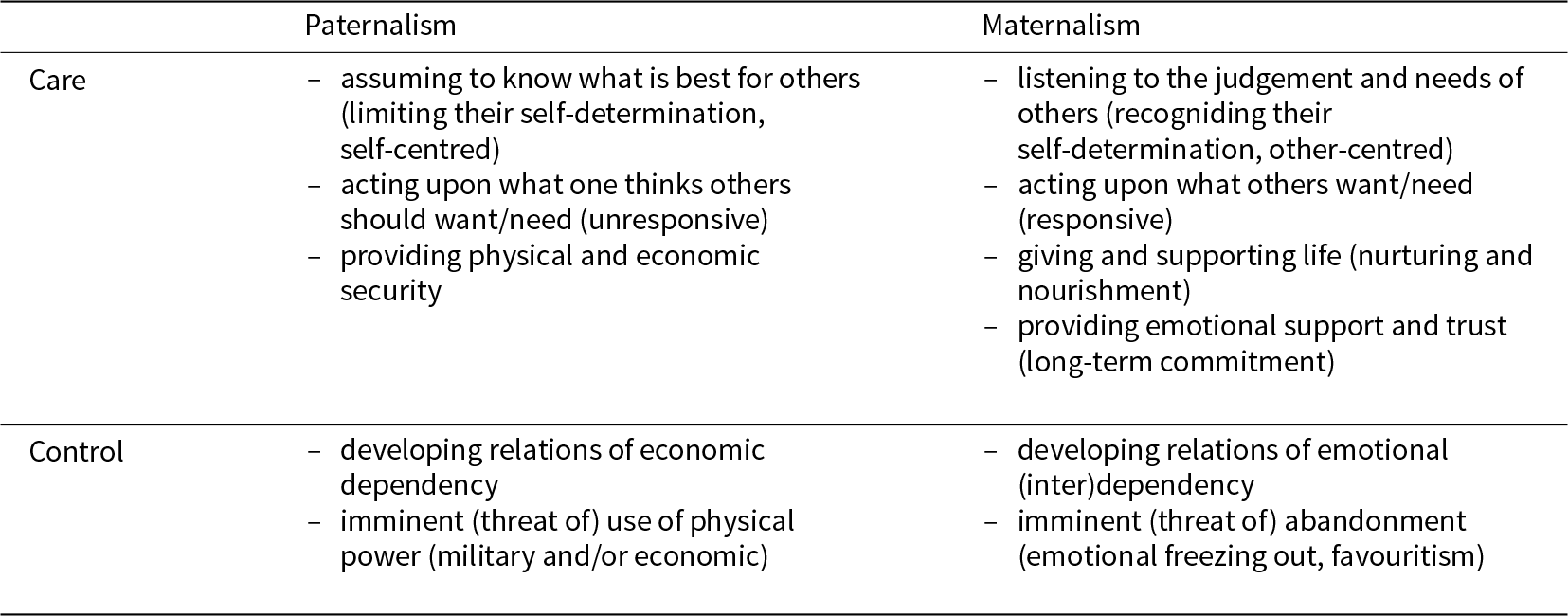

‘Care ethics is constituted not by rules or principles, but through practices’,Footnote 80 and feminist thinkers conceptualise mothering as a practice or work.Footnote 81 This perspective aligns with the practice turn in diplomacy and helps identify diplomats’ relationship with civil society ‘by the work they set out to do’Footnote 82 with respect to these actors. Below, Table 1 summarises the distinctive practices through which extreme forms of paternalism and maternalism are expressed. Between coercive paternalism and neglectful maternalism, alternative and softer expressions of paternalism and maternalism will be found.

Table 1. Practices of paternalism and maternalism.

Maternalism and paternalism capture distinct ethics of engagement and types of relationships. As argued above, both maternalism and paternalism include elements of care and control that can emerge in imbalanced relationships. The analytical focus of paternalism studies has traditionally been on the element of control.Footnote 83 By engaging with feminist scholarship, I develop the element of care and introduce the notion of maternalism, which is characterised by a different set of caring and controlling practices. In effect, leaning on underlying assumptions and constructions of self and other, we can distinguish different types of relations. The fundamental distinction between paternalism and maternalism hinges on how those in the position of power engage with the weaker parties. The distinct practices spring from the fact that those in one’s care and control are perceived differently. Since paternalism is based on the belief that those in need of protection have neither competence nor capability, the relationship with them is built on a lack of trust that they will act in their (externally defined) best interest. Maternalism, for its part, is based on the assumption that those in need of care and protection are competent and capable of defining their own needs and interests, and thus, the relationship with them builds on trust in their self-determination.

Diplomatic brokerage through the lens of maternalism

In the remaining parts of this section, I discuss diplomatic brokerage, a common activity for diplomats, to present how maternalism and paternalism translate into different forms of brokerage. There is wide recognition in the literature on diplomacy that diplomats act as intermediaries or mediators of estrangement.Footnote 84 Both when they negotiate and when they collect information, activities that are primary devices in the diplomacy toolbox,Footnote 85 diplomats build networksFootnote 86 around critical policy issues pertinent to the mission, connecting with various actors and placing them in contact with one another. In these endeavours, diplomats act as brokers, sometimes also creating connections between actors who would otherwise not meet.Footnote 87 Brokerage has empowering effects, as it expands the capacity of the actors that are being connected, but it also benefits the broker.Footnote 88 Brokerage, or the ability to connect and become connected to other actors, enhances the broker’s ability to control the entire network.Footnote 89 The privileged position of the broker is shown in their potential to redesign the playing field (be it a specific network or an agenda in a policy field). The broker can strengthen some actors by providing them with new ties (and thus, e.g., access to new knowledge), but they can also weaken other actors by upholding the segregation between groups or actors (acting as a gatekeeper).

How can we distinguish between maternalistic and paternalistic diplomatic brokerage? All diplomats engage in connecting various groups, including those groups that would otherwise remain unconnected, and introduce them to various networks that could benefit them. This brokerage is maternalistic when it is done in response to demands from other actors, even in extreme situations when the requested connections are not the ones that the diplomat imagines are in the other actor’s best interest. For instance, a CSO might ask a diplomat to arrange meetings with foreign funders in contexts where there is a foreign agent law in place.Footnote 90 A (possibly neglectful) maternalistic broker would arrange such meetings, respecting the judgement and self-determination of the CSO in question. Maternalistic brokerage is responsive. It follows that maternalistic brokerage is adapted and tailored to the particular needs of specific actors, instead of a generalist approach to CSOs as such. Additionally, when diplomats develop connections with certain CSOs on a long-term basis, which fosters trust and attachment, they showcase the element of maternal care. Paternalistic care would be apparent in unresponsive diplomatic brokerage, as it is not tuned into specific demands of CSOs and instead would be based on what diplomats think CSOs (in general) need. Hence, a paternalistically disposed diplomat would rather organise general conferences with CSOs, even if these are not asked for by the CSOs and, for instance, would decline requests for meetings with foreign funders if the diplomat deemed that such meetings would hurt the interests of CSOs, thus imposing their own judgement and ignoring the self-determination of the other in their presumed best interest. Nevertheless, even maternalistically dispositioned diplomats are in charge of the networks, and it is up to them to design and terminate these contacts. Maternalistic brokerage can also be selective, resorting to gatekeeping and favouring some CSOs over others. These practices indicate the element of maternal control. When diplomats push their own agenda through selective networking, and especially when they resort to economic dependency, the element of paternalistic control is visible.

There is obviously no clear-cut switch point between maternalism and paternalism, which are both part of the same metaphor of parenting. In both maternalism and paternalism, relationships between those who are unequal, such as parents and children, large and small states, or diplomats and local CSOs, are at stake. The literature on paternalism is divided between ‘those who think that the motives of the “paternalist” and the absence of consent of the “paternalized” are core features of paternalism, and those who argue for a more structural approach that focuses on asymmetrical power relations rather than motives and consent’.Footnote 91 I agree with BarnettFootnote 92 that the structural approach is much better suited for the study of international relations and expand this perspective to the notion of maternalism, leaving aside the extent to which intentionality and consent are involved in paternalism and maternalism. Crucially, both maternalism and paternalism entail a tension between the elements of care and control, albeit expressed through different practices. As exemplified above, the central practice of networking and brokerage through which diplomats engage with civil society in host states can be enacted in a maternalistic or a paternalistic manner.

Case selection and methods

The study is based on interviews with ambassadors from Western countries that profess adherence to liberal values (Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands) placed in two countries – Poland and Hungary – whose governments, at the time of interviewing, had declared an illiberal orientation in politics. Hence, the sample does not include the diplomatic corps as a wholeFootnote 93 in Warsaw and Budapest, which at the time of data gathering, in 2019 – 2020 amounted to 90 embassies in Warsaw and 72 in Budapest. Instead, the focus is on strategically selected members of a distinctive, if informal, subgroup of the diplomatic corps in those capitals. This choice was guided by two principles. The first selection requirement was active engagement of the embassy with Polish and/or Hungarian CSOs, information about which was solicited from interviews with ambassadors (snowballing) as well as from interviews with CSOs (material from CSO interviews was otherwise not used in this article). On this ground, the US and UK embassies were excluded as candidates for the sample since, during the time of data gathering, both these embassies were deemed rather inactive by local CSOs and fellow ambassadors. The UK was preoccupied with Brexit, withdrawing from previous civil society engagements in the region, and the United States under President Trump also became rather passive in the region. The second selection principle was these embassies’ self-declared shared identity as like-minded liberal states. Obviously, ‘liberal’ and ‘illiberal’ are not fixed categories. Even with well-regarded liberal democracies, democratic reputation and identity might shift with a change in government. This was most obvious in the United States under President Trump. Similarly, Poland’s illiberal orientation is likely to subside after the 2023 parliamentary elections. Hence, changes in governing parties in sending and receiving states might impact to what extent and how diplomats abroad will interact with CSOs.

The choice to focus on adversarial contexts, i.e. where the declared value orientation of the sending government clashes with the value orientation of the receiving government, is motivated by the expectation that diplomatic engagement with local civil society actors in such contexts will be prioritised by the relevant embassies.Footnote 94 In recent years, as illiberalism has taken hold around the globe,Footnote 95 such adversarial diplomatic sites have become more common. The chosen bilateral settings represent a power disparity, as all selected sending states prevail over the Central European countries in the international hierarchy of states, measured by the relative military and economic weight of states.Footnote 96

In 2004, both Poland and Hungary became members of the European Union (EU), defined as ‘liberal power Europe’,Footnote 97 but since the radical right-wing party Fidesz came to power in Hungary (in 2010) and Law and Justice did so in Poland (2015–23), these countries have taken an illiberal path. In effect, they have gradually de-democratised,Footnote 98 with Hungary no longer qualifying as a democracy.Footnote 99 Both countries hold relatively free elections, while the rule of law and civil liberties are limited. Governments have curtailed freedom of the press and politicised the judiciary, thus openly targeting independent institutions.Footnote 100 Aiming to instil illiberalism, governments have also sought to reconfigure civil society. While liberally oriented CSOs, such as women’s and minority rights organisations, have experienced a decrease in state funding and in their access to public media and policy influence, paired with various forms of legal harassment and public smearing, the same governments have orchestrated a rapid expansion in the number of CSOs that support the government.Footnote 101 This process is more visible in Hungary, which has been under illiberal rule since 2010. The cases of Poland and Hungary are best understood as situated between closed authoritarian systems with barely existent or heavily persecuted civil societies, thus prompting diplomats to cautiously manoeuvre contacts with dissidents, and liberal democracies with flourishing civil societies in which diplomats openly engage with CSOs as experts or partners in specific issues. In the illiberal context of Hungary and Poland, contacts with civil society actors become very desirable both among diplomats, as the information from official representatives and the state-controlled media cannot be fully trusted, and local CSOs, many of which have experienced a shrinking national space of actionFootnote 102 and thus seek alternative fora.

In total, 15 qualitative semi-structured interviews with ambassadors (including one counsellor chargée d’affaires a.i.) have been conducted (see Appendix). Seven of the interviewees were ambassadors in Hungary, eight were ambassadors in Poland, and only four of the interviewed ambassadors were women. The interviews lasted an average of 54 minutes, and all of them were recorded, transcribed, and coded with the help of NVivo. The interviews centred around civil society–diplomacy relations. According to the informed consent agreement, all direct quotes were anonymised in the article. The ambassadors were assigned a random number, which hopefully contributes to greater transparency in the interpretation of quotes, as it allows the reader to see the distribution of quotes among different interviewees. While this article applies a qualitative approach and there is no ambition to quantify the findings, I believe it matters if a standpoint is often recurring or rather idiosyncratic. For this reason, references to other ambassadors are added after quotes that mirror similar formulations.

The methodological approach in this article follows an abductive logic,Footnote 103 sometimes described as ‘inference of the best explanation’.Footnote 104 In practice, this logic is based on the researcher’s engagement in a back-and-forth movement between theory and data in a bid to develop new or modify existing theory. Abductive inferencing is more than a method; it is also an attitude towards data and towards one’s own knowledge: data are to be taken seriously, and the validity of previously developed knowledge is queried.Footnote 105 In this sense, the abductive process aligns with feminist sensibility, which, according to Cynthia Enloe, amounts to maintaining the capacity to be surprised.Footnote 106 Abduction proceeds from an observation to its most plausible explanation.Footnote 107 The process starts with the researcher’s observations pertaining to a certain phenomenon. In the interest of understanding and explaining this phenomenon, the researcher develops a proposition based on this observation while also drawing on relevant theories and theoretical concepts. In the next step, data are used to validate the proposition, possibly suggesting new knowledge. Hence, abductive logic combines inductive and deductive evidence. In the process of coding interviews, I was surprised by the language diplomats used when speaking about civil society. The striking parallels to the language of parenting led me to seek adequate explanations in the theoretical literature. Going back and forth between data and theory, I found the notion of paternalism insufficient and developed the complementary notion of maternalism.

Diplomatic maternal engagements with civil society

Like stereotypical mothers, the embassies of liberal states at the centre of this study do not have economic resources to offer civil societies in Poland and Hungary. A few of these embassies provide only moderate financial support to local CSOs, and most offer no financial support at all. After Hungary and Poland joined the EU, international financial aid for their civil societies was withdrawn based on the assumption that EU membership signified that these countries would join the liberal club of consolidated democracies. As the ambassadors highlighted, lacking direct funding possibilities, their embassies resorted to other ways of aiding civil society actors in Poland and Hungary (Amb_PL_1, Amb_PL_8, Amb_HU_1, Amb_HU_3, Amb_HU_5, Amb_HU_7). A typical explanation reads, ‘We don’t have any money to support civil society, so we engage with them’ (Amb_HU_3). This section will tease out the various forms of diplomatic engagement with civil society.

Not surprisingly, the ambassadors, many of whom had previous experience from other postings around the world, pointed out that the context is crucial for how engagement with civil society is shaped. Warsaw and Budapest are both relatively busy diplomatic sites, each hosting a significant number of foreign states. Regular interactions with CSOs are included in the busy schedules of diplomats, among meetings with various actors such as other diplomats, politicians, business representatives, and media. The civil society landscape in Poland can be described as vibrant, with approximately 140,000 formally registered CSOs in 2021Footnote 108 and many informal initiatives. Hungary’s civil society is significantly smaller, less active, and largely centralised in the capital. Both civil societies are marked by the illiberal shift in politics. One ambassador in Warsaw explained:

I think civil society is now much more … the critical part, it’s much more interested in having contacts with us, because they see us as a source of … yeah, defence, maybe? … […] and of being somehow part of the game, not pushed to the sidelines. Yes, that has been a very … That has changed … The relationship after 2015 [when Law and Justice came to power in Poland] has changed. (Amb_PL_6)

The ambassador alluded to the fact that civil society in Poland is deeply divided, with some ‘critical’ organisations being marginalised in the public sphere and thus more inclined to reach out to embassies of liberal states. The deep division between the liberal and leftist (anti-government) and the illiberal and conservative (pro-government) sides of civil society, as we will see, has implications for the types of engagement ambassadors commit to.

Diplomats as caring and controlling mothers

The interviewed ambassadors repeatedly stressed that the effort to attend to the demands and meet the needs of local CSOs guides their engagement: ‘learning more about their challenges, seeing what kind of supports that they need’ (Amb_HU_1). The ambassadors highlighted listening to and communicating with CSOs to become aware of what these CSOs are doing and to learn about their challenges as their most important tasks with respect to civil society. Listening, which is so central to the ethics of care,Footnote 109 is often neglected in analyses of diplomatic practice.Footnote 110 In the interviews, it was emphasised as a key form of engagement with CSOs (Amb_HU_7, Amb_PL_8). One ambassador even indicated emotional labour – showing empathy – as crucial to the relationship with civil society: ‘Well, first of all, for many of these organisations, it’s very important, too, that someone is listening to them. And you know, the empathy, the sympathetic ear’ (Amb_PL_1).

The ambassadors reported the ambition to respond to specific needs of CSOs. Like mothers, they literally feed them, inviting them for coffee, organising ‘dinners, we have lunches, we can meet them, we can talk to them’ (Amb_PL_1). This type of engagement is often rather low-key; ‘it doesn’t have to be anything remarkable – a cup of coffee, showing interest’ (Amb_HU_5, also Amb_PL_8). Diplomats engage in nurturing CSOs, providing them with food; this practice becomes an opportunity to talk and show interest, similar to ‘enabling a child to survive and thrive’.Footnote 111 In their engagement, the ambassadors both metaphorically and literally ‘set the table’ (Amb_HU_5); they nurture CSOs both by nourishing them and by helping them grow, ‘supporting [them] with arguments and inspiration’ (Amb_HU_2).

Diplomats also highlighted that their engagement with civil society is long-term: ‘Meetings are the most important, that you regularly meet’ (Amb_HU_5). They deliberately engage in building lasting relationships with CSOs. ‘Maybe the most important part is to be present’ (Amb_HU_6, also Amb_PL_4). Being present implies a long-standing commitment and reliability, both of which are a prerequisite for trust. Again, like caring mothers, liberal diplomats signal support for CSOs even if these are in trouble with their own governments. Especially for liberal CSOs, ‘being present’, publicly standing by and ‘show[ing] support to certain NGOs, which are subject to open hate speech or something’ (Amb_PL_3) is a recognition of the vulnerability of CSOs and a response to their fundamental needs. As in the case of Svetlana Alexievich in Minsk, the ambassadors use their special status to manifest solidarity with harassed CSOs.

The ambassadors described their engagement with the liberal part of civil society in Poland and Hungary as securing the survival of that civil society:

Most of all, this is about giving them space, if it [civil society] is being limited, if it is being suffocated, then we have to pump the oxygen, to give them more space … lifting them in all circumstances. (Amb_HU_5)

Diplomatic engagement with civil society is here portrayed as providing life support (‘pump[ing] the oxygen’), just as mothers give and nurture life. It indicates the element of maternal care through creating space for the expression and enhancement of the self-determination of CSOs.

Responsively tending to the needs of CSOs is an example of the care component of maternalism. The other component – control – is also present, even though it was less readily discussed by the ambassadors. The latter seemed quite aware that they are the ones setting the conditions of engagement with CSOs. For instance, several interviewees remarked that the requests and initiatives from civil society actors exceed the embassies’ ability to meet all these expectations (Amb_HU_2, Amb_HU_4, Amb_PL_5). As a result, some demands were left unanswered, and some CSOs did not receive the assistance and support they required. It is up to diplomats to make those decisions. What the interviews with ambassadors representing liberal states in Poland and Hungary exhibit is a maternalistic disposition, that of a caring and emotionally engaged mother, with certain elements of control.

The interviews also manifested the continuum between maternalism and paternalism. One ambassador quite openly claimed to better know what is good for CSOs.

And that’s why sometimes you have to protect civil society. Not to be in … Not to exaggerate with close contacts with us, because it may be used against them. […] Yeah. So no, we’re very aware of that, to protect them from themselves, so to say. But of course, we think it’s good to be in [laughter] contact with us, so … again, calibration. (Amb_PL_6)

The careful calibration the ambassador highlighted points to the balancing on the porous line between maternalistic (responsive) and paternalistic (unresponsive) care. When catering to the needs of CSOs turns into defining these needs for them and even ‘protecting them from themselves’, allegedly in their best interest, maternalism turns into paternalism. The diplomats analysed in this study lack the coercive tools of money and weapons (paternalistic forms of control), but they can still exhibit paternalistic care through all-knowing, unresponsive practices that limit the self-determination of CSOs.Footnote 112

Maternalistic brokerage

The ambassadors’ broad connections across various sectors seem to be a major asset that they put to use in their engagement with civil society. They act as maternalistic brokers, utilising their nodal position in various networks to meet the demands of CSOs.

In the most material way, diplomats respond to the demand for ‘venue’ from CSOs. The organisations are offered access to the premises of the embassy and the residence for conferences and meetings (Amb_PL_1, Amb_PL_2). Needless to say, a conference at the embassy automatically gains gravitas. Moreover, acting upon the expressed needs of Polish and Hungarian CSOs, ambassadors connect various actors with each other, thus expanding the social capital of CSOs ‘to help build their [CSOs’] networks, their capacity as well’ (Amb_HU_1). Diplomats utilise their unique positioning and access to various groups in society to ‘raise their [CSOs’] voice, or you know, expose it a bit to the broader networks’ (Amb_PL_1). In this way, they help them ‘thrive’.Footnote 113 For instance, they connect local CSOs with state officials and CSOs from their home country; Polish and Hungarian CSOs with their respective government officials; oppositional and pro-government CSOs with each other; and CSOs with various business representatives (potential donors). ‘In this, I think we can be of help, to identify each other’ (Amb_PL_8, also Amb_PL_1). Often, as the literature on brokerage describes,Footnote 114 these are connections that would not have taken place were it not for the intervention of the broker. Indeed, one ambassador was visibly proud of having brokered a meeting between Polish pro- and anti-government CSOs at the embassy: ‘Inviting both sides of civil society, which almost never happens otherwise … and the biggest value of that was that they were sitting next to each other and actually discussing, which is quite magical’ (Amb_PL_1). This satisfaction shows emotional engagement and resembles the maternal practice of creating a nurturing atmosphere for CSOs.

The ambassadors stressed that the initiative for engagement most often comes from CSOs, and in this sense, brokerage is responsive – like mothers, diplomats react to the demands expressed by CSOs.

I mean, there are so many contacts from the organisations, and they have a lot of good ideas, so I would say that we didn’t … And they are … Well, in that way they are employing us quite a lot, so we did … I don’t recall many cases where we have been, or we needed to have been proactive. […] we are quite nicely employed by those NGOs. (Amb_HU_4, also Amb_PL_4, Amb_PL_5)

The CSOs are so active with respect to diplomats that additional outreach activities are often left out. CSOs in both countries contact the embassies of liberal states and are explicit about what they expect from them. The responsive character of diplomatic engagement with civil society (the embassies being ‘employed’ by CSOs) manifests a maternalistic type of brokering, which is driven by attention given to the demands of CSOs. By letting themselves be employed, diplomats also acknowledge and trust the agency and self-determination of CSOs, which, in these instances, represent the proactive part that initiates and suggests concrete engagements.

Importantly, as discussed in the literature on brokerage,Footnote 115 brokering is seldom disinterested or purely other-centred; it brings clear advantages to those positioned as brokers. Indeed, the ambassadors underlined that it is not just a service they provide to CSOs in response to their demands; they see the various meetings they arrange or facilitate as absolutely crucial to their work. Through contacts with civil society actors, ambassadors gain access to unique information. As one interviewee stated: ‘We try and use in our political work some of their analyses, which is, let’s be honest, a great help, without which we would have … we would not be able to do what we do’ (Amb_HU_3). The information gathering that is so central to frontline diplomats’ workFootnote 116 is made possible because they act as brokers. This statement underscores the interdependency between diplomats and CSOs, underlined by the ethics of care literature.Footnote 117 CSOs are in need of the brokering and caring support of diplomats, and diplomats need the knowledge that CSOs can provide them. Hence, maternalistic brokering helps uncover ‘the fact that caregivers too are vulnerable, needy and sometimes incompetent’,Footnote 118 at least to some extent transgressing the dichotomy between powerful caregivers and powerless care receivers.

While the nurturing and responsive stance resembles the element of care present in maternalism, maternalistic brokerage also includes control. The ambassadors were quite explicit that it is their discretionary, convening power to plan and execute meetings, for instance, by suggesting which local CSOs to include when ministerial delegations from the home country are scheduled (Amb_PL_2, Amb_PL_6, Amb_PL_8, Amb_HU_5, Amb_HU_6). Hence, ambassadors exert maternal control by selectively choosing which CSOs to include in their networks. According to the interviews, the ambassadors almost exclusively interact with anti-government CSOs that share the liberal values of the embassy (Amb_HU_1, Amb_HU_2, Amb_HU_4, Amb_HU_5, Amb_HU_6).

It’s mainly organisations active in politically sensitive issues: energy policy, equality issues, rule of law issues, refugee issues, these types of issues. Maybe this is also natural, because these are sensitive issues where opposing voices, or at least divergent views need to be more actively nurtured. (Amb_HU_6, emphasis added)

Maternalistic brokering and nurturing are only present with respect to some CSOs. On the rare occasions that pro-government organisations contact the embassy, they are reportedly not dismissed in advance, but they cannot count on the care – listening, nourishing, and emotional support – that liberal, anti-government CSOs are granted. There is apparent hesitation to engage with CSOs that

clash with our liberal values. […] of course, the relationship between the critical civil society organisations is more important than the other ones. But they’re there and it would be a grave mistake, in my view, not to take them somehow into consideration. (Amb_PL_6, also Amb_PL_4)

A few ambassadors pointed out that, keeping in mind the polarisation in Polish and Hungarian civil societies, embassies of the liberal states make a more or less wholehearted attempt to keep in touch with conservative organisations as well (‘take them somehow into consideration’). The ambassadors recognised that they privilege some CSOs and that this might come across as problematic. They realised that it might be construed as unequal treatment, that is, as strategically choosing some CSOs over others.

There’s also very much the kind of pro-government civil society. I have to admit that we haven’t really been liaising with them so much. This is perhaps something we should be doing. Also more to listen to the far-right, for instance, because this is also our job to … the pro-government far-right media also. We have done that a little bit. But that’s another thing, that it’s important that we actually talk to all parties. (Amb_PL_3, also Amb_PL_1, Amb_PL_6)

The ambassadors seemed aware that maintaining the appearance of having contacts with different types of CSO, of distributing care fairly, is something they ‘ought to do’ (Amb_PL_5). This awareness echoes the feminist literature on motherhood, in which scholars have recognised that care can also be selectiveFootnote 119 and that favouritism might occur, which I interpret as an expression of maternalistic control. One interviewee put it frankly:

- We recognise that there are civil sector organisations that are not in opposition to the government. Some of them are GONGOs [government-organised non-governmental organisations]. But they are part of the picture, and sometimes, it’s psychologically correct also to meet them.

- What do you mean by ‘psychologically correct’?

- So that we present at least the image of being impartial, in a way. (Amb_HU_6)

It is apparent that the ambassadors are reluctant to connect with CSOs not aligned with the values of the embassy. Because the embassies predominantly engage with liberal CSOs, these organisations benefit from maternal care and the new connections enabled by maternalistic brokering. Only some CSOs are empowered. As Rebecca Adler-Nissen observed, diplomats ‘inevitably take sides, even when they pretend not to do so’.Footnote 120 As brokers, the ambassadors I interviewed indeed make sure to boost the capacity of liberal CSOs while mostly keeping conservative organisations at arm’s length, acting as gatekeepers. The latter are abandoned or frozen out. I would argue that such selective brokerage highlights the tension between the components of maternalistic care and control in diplomats’ engagement with civil society.

Concluding reflections

The article aimed to theorise and empirically examine diplomatic engagements with civil society actors in bilateral relations. Based on observations from a previous studyFootnote 121 that adversarial contexts make diplomatic contacts with civil society especially important, the investigation is centred around diplomats representing liberal states in the illiberal contexts of Poland and Hungary.

The research question, which addresses the forms of diplomatic engagement with local CSOs, aimed to capture the everyday work of frontline diplomats to help theorise their engagement with civil society. To this end, and building on the theoretical work by Michael Barnett, I introduced the concept of maternalism as a complement to paternalism in unequal power relations. The litmus test for the value of any concept is that it allows the perception of things that would not otherwise be seen. Hence, I constructed a continuum from coercive paternalism to neglectful maternalism, distinguishing practices of maternalistic care and control from paternalistic care and control. Using the notion of maternalism, I sided with recent scholarship, which pushes for ‘a research agenda on love and care in remaking a world’.Footnote 122 Roxani Krystalli and Philipp Schulz argue that harm and care exist side by side and that we should study both. They argue that in their field – Conflict Studies – and in International Relations more broadly, suffering, harm, and violence have had a privileged position. By introducing the notion of maternalism, I wish to direct analytical attention to care in diplomatic engagements with civil society. While paternalism already includes the element of care, it gives epistemological priority to practices of control. The notion of maternalism, still based on the realisation that care and control ‘sit alongside’,Footnote 123 shifts the analytical focus to practices of care. Maternalism centres care (without losing sight of transpiring practices of control) and thus makes visible engagements that would otherwise be sidelined or mentioned only in passing as those merely softening the control element of paternalism.

The empirical analysis revealed that the ambassadors expressed maternal care by listening, by being responsive to the demands of CSOs, and by nurturing and brokering contacts requested by these organisations. For this type of engagement, found in interactions between ambassadors of liberal states and liberal CSOs in host states, maternalism rather than paternalism seems to be a suitable heuristic tool. A different disposition is found with respect to CSOs supporting the illiberal regimes in Hungary and Poland. These CSOs are, for the most part, excluded from the benefits of maternalistic care and from maternalistic brokering exercised by liberally oriented embassies. Such favouritism showcases the element of maternalistic control. The limited empirical sample makes firm conclusions about what general conditions would prompt maternalistic or paternalistic dispositions towards CSOs unjustified. However, the conceptual distinction between paternalism and maternalism allows future studies to explore which underlying social relations are more likely to generate paternalism or maternalism; whether those more ideologically similar to diplomats are more likely to be constructed as competent and autonomous, capable of informed choices; and concretely, whether we can expect embassies representing illiberal governments, such as those of Russia under Putin or Brazil under Bolsonaro, situated in liberal contexts, to engage with local right-wing CSOs in a maternalistic way, prioritising them in their brokerage and care. In any case, the differentiated engagement of diplomats according to the value orientation of local CSOs makes it clear that a nuanced view of civil society is necessary to understand the relations between diplomacy and civil society, including its ‘dark side’.

This article, which is among the first to systematically approach diplomacy–civil society relations, will hopefully spark a debate about this element of frontline diplomats’ work. It goes without saying that to fully explore these relations, the vantage point of CSOs must be included. The choice in this article to focus exclusively on the perspective of diplomats, giving them the interpretive privilege, was pragmatic, as it provided space for conceptual reflection, but it also highlighted the point that maternalism, just as paternalism, is marked by power asymmetry. Regarding the article’s wider implications for the study of diplomacy, the notion of maternalism introduced here expands our understanding of the work of diplomats, putting emphasis on practices otherwise often ignored, such as listening. While the practice turn brought attention to the everyday of a diplomat, the concept of maternalism highlights that even in ostensibly harmless interactions, we should be attentive to (structural) power dynamics. Through a close investigation of diplomatic practice in relation to civil society and with the help of the notion of maternalism, we can better grasp the complexity of and changes in diplomacy.

Acknowledgements

I want to express my gratitude to Michael Barnett, who urged me to refine my argument. Colleagues from GenDip - Ann Towns, Birgitta Niklasson, Haley McEwen, and Monika de Silva - have provided invaluable insights and support. Additionally, Rebecca Adler-Nissen, Kristin Eggeling, Constance Duncombe, Laurence Piper, and Tuba Inal have generously shared their thoughts on earlier versions. The anonymous reviewers and editors of this journal have proven exceptionally helpful and constructive. I also acknowledge the generous finacial support of The Swedish Research Council’s project grant 2017-01426.

Appendix. List of interviewees

Daphne Bergsma – Ambassador of the Netherlands to Poland 2020–present; interview 16 January 2020

Olav Berstad – Ambassador of Norway to Hungary 2016–20, interview 11 November 2019

Ole Egberg Mikkelsen – Ambassador of Denmark to Poland 2016–20, interview 15 January 2020

Inga Eriksson Fogh – Ambassador of Sweden to Poland 2015–17, interview 8 January 2020

Charlotte Garay – Counsellor Chargée d’Affaires a.i. of Canada in Hungary 2019, interview 21 November 2019

Kirsten Geelan – Ambassador of Denmark to Hungary 2016–20, interview 12 November 2019

Stefan Gullgren – Ambassador of Sweden to Poland 2017–23, interview 13 January 2020

Dag Hartelius – Ambassador of Sweden to Hungary 2019–23, interview 12 November 2019

Staffan Herrström – Ambassador of Sweden to Poland 2011–15, interview 8 October 2019

Olav Myklebust – Ambassador of Norway to Poland 2018–20, interview 16 January 2020

Rolf Nikel – Ambassador of Germany to Poland 2014–20, interview 15 January 2020

Juha Ottman – Ambassador of Finland to Poland 2018–22, interview 14 January 2020

Niclas Trouvé – Ambassador of Sweden to Hungary 2014–19, interview 4 October 2019

René van Hell – Ambassador of the Netherlands to Hungary 2017–21, interview 14 October 2019

Markku Virri – Ambassador of Finland to Hungary 2018–22, interview 14 October 2019