No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 October 2009

1 Victoria Kahn and Neil Saccamano, ‘Introduction’, in Victoria Kahn, Neil Saccamano and Daniela Coli (eds), Politics and The Passions, 1500–1850 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006) p. 4.

2 For the Kantian sublime, see The Critique of Judgment, trans. J. H. Bernard (Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 2000). On the deployment of the sublime in international studies, see especially the Special Issue of Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 34:3 (2006): Between Fear and Wonder: International Politics, Representation, and ‘the Sublime’.

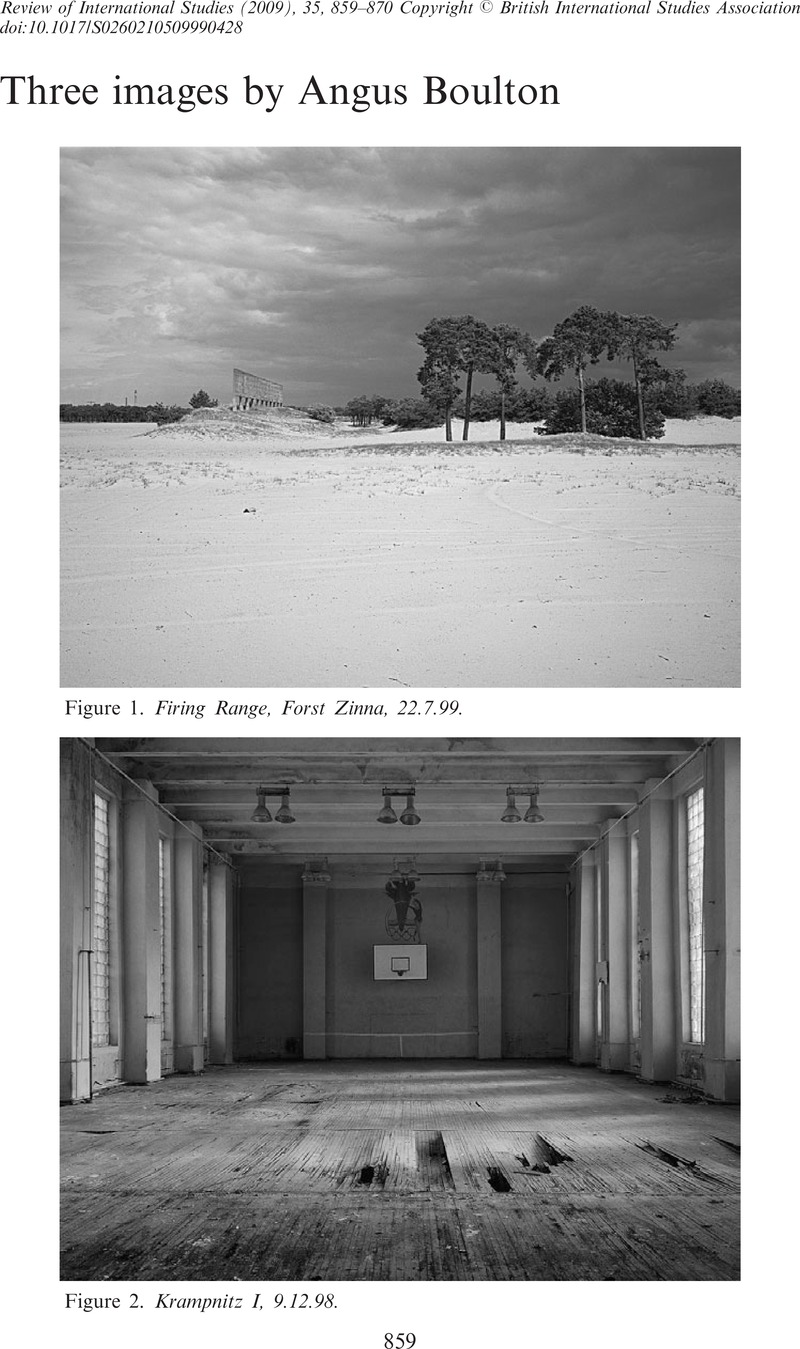

3 {http://www.angusboulton.net} accessed 17 February 2008.

4 The image of the lamp-post curiously planted in the woods, and happened upon by the inquisitive and brave little girl, Lucy, is from The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis. It is, as Jacques Derrida argues, temporal ‘out of joint-ness’ that makes it possible for spectres to emerge. See, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International, trans. Peggy Kamuf (New York: Routledge, 1994).

5 Rather than thinking about the ways in which the sublime, the tragic and the epic are opposed to the everyday, the mundane and the banal, I am interested in figuring out the ways in which one is composed of, or inhabited by, the other. On this, see Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005), especially on ‘stuplimity’: ‘while the Kantian sublime stages a competition between opposing affects, in which one [‘tranquility’] eventually supersedes and replaces the other [for example, fear] … stuplimity is a tension that holds opposing affects together,’ p. 271. The micro-physics of power imagery here is obviously indebted to Michel Foucault.

6 Roland Bleiker and Martin Leet, ‘From the Sublime to the Subliminal: Fear, Awe and Wonder in International Politics’, in, Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 34:3 (2006), pp. 713–37, p. 714. I would argue that affective ambivalence can be pushed much further that suggested here.

7 In my interpretation, that is, Boulton, like Walter Benjamin, refuses both progress and regression in the interpretation of the present, ‘post-cold-war’ moment; the cold war prehistory has been neither rejected nor recuperated, but still needs careful analysis.

8 Margaret Atwood, Cat's Eyes (London: Virago, 1990), p. 3.

9 The possibilities as well as the dangers come from the ways in which the emergent exceeds the categories by which geopolitics is conventionally understood: inside/outside, self/other, native/alien. Securitization, a global war for hegemony, as a response to ‘sublime’ terror is a recuperative moment that tries to assert mastery over the incomprehensibly other. What happens if one tries to think counter/terror without recourse to answers that can only be inadequate and violent? We have to learn to respond to ghosts.

10 Walter Benjamin, ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History,’ in, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, Edited by Hannah Arendt. Translated by Harry Zohn (London: Fontana, 1992). Thesis VI continues: ‘even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.’ The second quotation is from Raoul Vanegeim, The Revolution of Everyday Life, translated by Donald Nicolson Smith (London: Rebel, 1983), p. 233. But see also Derrida's Specters of Marx: ghosts are not always the subversive ones; spectrality is more complicated than Vanegeim allows for. Finally, of course the texture and complexity of all historical moments shapes crisis points such as ours, averts or intensifies them.

11 Ernst Bloch, The Principle of Hope Vol. 1, translated by Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice, and Paul Knight (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986), p. 9.