The cheeks are those round parts in the face which are also called apples.…The skin of this part is thinner than that in any other part of the face; it easily grows red and changes its natural color through affections of the mind. This color is commonly rosy in those of good complexion.

Jacopo Berengario da Carpi (ca. 1460–ca. 1530), A Short Introduction to Anatomy (1522)Footnote 1INTRODUCTION

In the culmination of Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), Charles Darwin (1809–82) anointed blushing as “the most peculiar and the most human of all expressions.” After surveying correspondents in China, Polynesia, Africa, South America, and other locales around the globe, the English naturalist reasoned that the blush must be “common to most, probably to all, of the races of man.”Footnote 2 Precisely three centuries earlier, in 1572, the Italian physician Girolamo Mercuriale (1530–1606) had published the first medical work dedicated solely to the human epidermis, De morbis cutaneis (On skin diseases), heralding a newfound fascination with skin just when much of Europe was negotiating a rapid growth in global commerce, migration, human trafficking, and enslavement. The late Cinquecento would also engender the first book-length treatise on shame, Annibale Pocaterra’s (1559–93) Due dialogi della vergogna (Two dialogues on shame, 1592), which established the emotion as inseparable from the visual act of blushing.Footnote 3 And among a slew of anatomies published in the Renaissance, many, such as Andrés de Laguna’s (1499–1559) Anatomica methodus (Anatomical method, 1535), sought to devise the cardiovascular mechanisms by which “the cheeks of those afflicted with shame are immediately suffused with an uncontrollable blush, as though the heart, like a most severe judge, were propelling those warm humors…as far as possible from itself and sending them into exile as punishment for their sins.”Footnote 4 These brief examples suggest that, long before a nineteenth-century fascination with blushing in literature and biological science, the Renaissance was pivotal in expanding, legislating, and transforming the meanings of turning red. Yet, in contrast to Darwin’s empirical, albeit qualified, conclusion that blushing was universal, early modern Europe and its transatlantic empires construed it as a subtle yet potent marker of difference—of gender, class, religion, nation, and race.Footnote 5

Tracking the blush across national and conceptual borders, I propose, offers new perspectives on race-making in the early modern world, where the cultural prestige of whiteness and presumptions about skin complexion could operate to dispossess people of color of the very ability to blush. This transnational approach reveals that blushing’s relationship to race was far more complex than has previously been acknowledged.Footnote 6 The micro-expression of turning red thus lends a comparative vantage from which to probe how nations racialized skin complexion, and how their treatment of blushing, in turn, worked to construct a given understanding of race. It also affords a view of how social and poetic idealizations of so-called fair skin—along with all manner of astrological, medicinal, and cosmetic methods of dermal whitening—confronted such realities as the presence of the African diaspora in Europe, an awareness of Native peoples in newly conquered American territories, and the opening of trade routes with the Far East. Though blushing has drawn the attention of scholars of early modern England, it has been understudied elsewhere in the period and all but ignored in Spain and its empire, an oversight all the more puzzling because of Southern Europe’s longstanding classification as a culture of honor and shame. Joining recent scholarship in premodern critical race studies, and critical whiteness studies in particular,Footnote 7 this essay recovers Iberian sources in order to address this geographical lacuna and its corresponding racial blind spot. Surveying a broad range of texts—including recipes, cosmetic treatises, fencing manuals, courtesy books, compendia, polemics, historical chronicles, and literary, dramatic, religious, philosophical, and proto-ethnographic works—this more global framework intends to capture the mobile, protean nature of the blush as it emerged across racial formations of varying scale.Footnote 8

Two facets of blushing positioned it axiomatically as an accomplice in race-making. The first, inherited from antiquity, was its association with moral virtue.Footnote 9 According to the Spanish friar Luis de León (1527/28–91), “the insignia of a shameful spirit is seen on the cheeks,” on which “tend to appear the indications of decency [pudor] and of goodness and of modesty and of a very innocent and well-mannered spirit…for which the face of Christ was modeled and colored.”Footnote 10 Of course, as Laguna’s digression above indicates, the blush could also signal, in almost antithetical fashion, a sinful transgression. To note that early modern physicians, philosophers, theologians, and lexicographers alike equated blushing with shame, by and large, is not to neglect that facial redness could also summon more fluid, and sometimes ambiguous, concepts of bashfulness, guilt, anger, vigor, prurience, sexual arousal, or even inebriation.Footnote 11 In incisive studies of the blush in early modern England, Sujata Iyengar asserts that it “marks not a fundamental bodily truth but its literary or hermeneutic breakdown,” and Derek Dunne brands it “the most ambivalent of signifiers.”Footnote 12 My reading, too, acknowledges how rosy cheeks can elicit competing interpretations that may belie the blusher’s own interiority. Yet to insist too forcefully on the blush as a site of polysemic ambiguity, inscrutability, and misinterpretation is to overlook how early moderns themselves regarded it as a fundamentally legible emblem of shame and modesty and, thus, as a veritable litmus test for virtue. It was precisely this perception of the blush’s semiotic stability that enabled it to conspire in broader projects of racialization, whereby its alleged absence on dark skin denoted a shameless depravity in keeping with the aims of white supremacy and colorism.

The other, related maxim of blushing that abetted its reliability in such projects is that its emergence was assumed to be purely involuntary. Unlike the many other emotional expressions, such as laughing, trembling, and even weeping, which could be readily feigned,Footnote 13 blushing was a spontaneous psychophysiological response that, in principle, escaped the will of the blusher. It therefore appeared exempt from the somatic, linguistic, and cultural modes of “passing” by which one could more or less freely impersonate another race, religion, or class. These include acts of “passing up”—adopting, as Barbara Fuchs has outlined, the dress of another gender or religious majority for strategic motives of advancement or survivalFootnote 14—as well as acts of “passing down,” or appropriating the trappings of a non-dominant group, usually for entertainment purposes, such as the use of blackface, blackspeak, or blackdance, which scholars like Noémie Ndiaye and Nicholas R. Jones have recently studied.Footnote 15 Blushing’s self-evident immunity to artifice empowered it to connote genuine modesty and to index an ostensible racial essence, reinforcing the historical associations between white skin and moral virtue.

On the one hand, the case studies I examine here disclose how the reflexive purity of blushing became denatured through an unstable and altogether unlikely dalliance with performance. Thus, rather than reasserting the phenomenological ambiguity of how the blush could be interpreted, I locate its vulnerability in an ontological potential for artifice, simulation, and reproduction. Untangling the tightly bound ways in which performative blushing mobilized race—including the widespread use of cosmetic rouge and the vocal representation of the blush in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century drama—I maintain that blushing could destabilize more rigid discourses of race-, religion-, and gender-based hierarchies. These performative scripts around rubescent cheeks worked to undo the very notion of a native blush and, by extension, that of a natural racial essence. On the other hand, one should be wary of circumscribing race as a culturally constructed phenomenon, a discursive chimera that would risk trivializing the very real trauma and bodily harm perpetrated by early modern racism in all its forms. Ania Loomba has cautioned against “positing a simple opposition between nature and culture or suggesting that a ‘cultural’ understanding of race is somehow benign or flexible” in comparison to the biological paradigm that has conventionally demarcated the advent of modern racism.Footnote 16 Confronting this persistent binary, in her study of race and torture on the early modern English stage Ayanna Thompson advances a synthesis by which “race ends up being constructed in the contradictory terms of ‘discursivity and corporeality’: it is a performance, a discourse, but a performance in which the body is privileged. The audience’s gaze upon the racialized characters’ bodies,” she explains, “licenses the materiality of those bodies, but the performance…simultaneously deconstructs that materiality.”Footnote 17 My analysis poses the blush as especially apt for spanning this dialectic: it is an innate, biological experience; it is mobilized by the symbolically laden fluid of blood; it is mediated by the racialized bodily surface of the face; and it is an act that in the early modern era was increasingly replicated by a set of social and theatrical performances. And even as these performances unsettled attempts to map racial prestige onto facial redness, the blush remains a material, albeit fleeting, trace of affliction, an embodied testament to the trauma of the humiliation, degradation, and shame punishments that routinely targeted ethnoreligious and raced others. All of this conceptual mobility suggests that there is more to the early modern act of turning red, as it were, than what appears at first blush.

PAINTING THE TOWN RED

Blush may well be the only popular cosmetic that simulates, in both name and appearance, a physiological function. Yet if modern scholars have only rarely remarked on this seemingly straightforward fact, much less studied jointly the (natural) blush and (cosmetic) blush, early modern writings reveal an uneasy awareness of their correspondence. In asking “why doe women which are not borne fayre attempte with artificiall Beauty to seeme fayre,” Tommaso Buoni (fl. early seventeenth century) reasons in I problemi della bellezza (The problems of beauty, 1605) that

perhaps because women are very subject to blushing, which usually comes from shame…and already knowing that beauty is the common adornment of all women, being for the moste parte subject unto that pleasing redness, which ariseth of shamefastnesse…and knowing that this Beautifull bashfullnesse, giveth splendour and ornament to all women, it seemeth to their understandings a great note of infamy to be deprived thereof; and therefore to avoyde so great a blotte, they feare not with a thousand artes and inventions to give the like Beauty to their faces.Footnote 18

Situating the cosmetic blush as a makeshift for modesty, Buoni’s conjecture instates a circular logic of applying the insignia of shame to avoid that which would result from its absence, only to come full circle by echoing an abundant corpus of early modern texts that shamed women for painting. In a sense, this paradox inverts a recursive tendency intrinsic to the natural blush, whereby one’s self-consciousness of flushing only exacerbates the feeling of embarrassment. Though this causality constituted an impossible bind for women, it also posed a hermeneutic dilemma for those (mainly men) concerned with ascribing a credible origin to rubicund cheeks. The character of Gianozzo in Leon Battista Alberti’s (1404–72) Della famiglia (On family, 1435–44) avows that only once, at a dinner party, did his wife flout his prohibition of makeup—a transgression for which she was sternly upbraided. But before crowing over the spousal obedience secured by his methods, he lets slip a telling admission: “It is true that at weddings, sometimes, whether because she was embarrassed at being among so many people or heated with dancing, she sometimes appeared to have more than her normal color.”Footnote 19 If Gianozzo’s puzzlement as to the cause of his wife’s blush “demonstrates the pragmatic and semiotic limitations of this masculine rule,”Footnote 20 then it also condenses social anxieties over the fragile distinction between natural and artificial—anxieties that grew as the hallowed mark of genuine modesty became besieged by ever more elaborate cosmetic regimes, themselves in part the fallout of patriarchal ideals of feminine beauty.

Channeling Petrarch and Ariosto, in his Gli ornamenti delle donne (The ornaments of women, 1562) Giovanni Marinello (d. ca. 1580) draws on the poetic precedents of these ideals when prescribing that “the cheeks will be white and red…the whiteness resembling milk, lilies, white roses, and snow, and the red color, a pair of ruddy roses and purple hyacinths.”Footnote 21 Marinello’s is one of several early modern recipe manuals that offered women practical advice for realizing the contrasting hues of such epidermal mimicry—a vogue whose appeal waxed and waned as it endured well into the eighteenth century (fig. 1). Among scores of instructions for cosmetic pigments, poultices, extracts, and elixirs for beautifying fellow noblewomen, Caterina Sforza’s (1463–1509) Gli experimenti (The experiments) gathers several recipes for dermal whitening, including a potion made from boiled nettles. Another entry plies red sandalwood and aqua vitae for a “very light and very excellent rouge,” which the Countess of Forlì promises will grant its bearer “a magical vivacity, elegance, and beauty.”Footnote 22 Substances far less benign commonly comprised treatments for reddening and whitening the face—examples include, respectively, cinnabar (derived from mercury) and Venetian ceruse (derived from lead). Yet another of Sforza’s recipes, “to make the face extremely white and beautiful,” requires litharge of silver, also a byproduct of lead.Footnote 23 Long-term effects of these poisonous compounds included facial lesions, blemishes, and scarring, which subjected their users to a malignant cycle of more painting and further injury. The noxious properties of certain cosmetics were not unknown to early modern commentators, who often invoked this risk with abject detail in their diatribes against women who painted. Applying makeup thus could mean succumbing to the ravages of chemical toxicity as well as, in modern parlance, to those of toxic masculinity.

Figure 1. François Boucher. Pompadour at Her Toilette, 1750 (with later additions). Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum, Bequest of Charles E. Dunlap. Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, 1966.47.

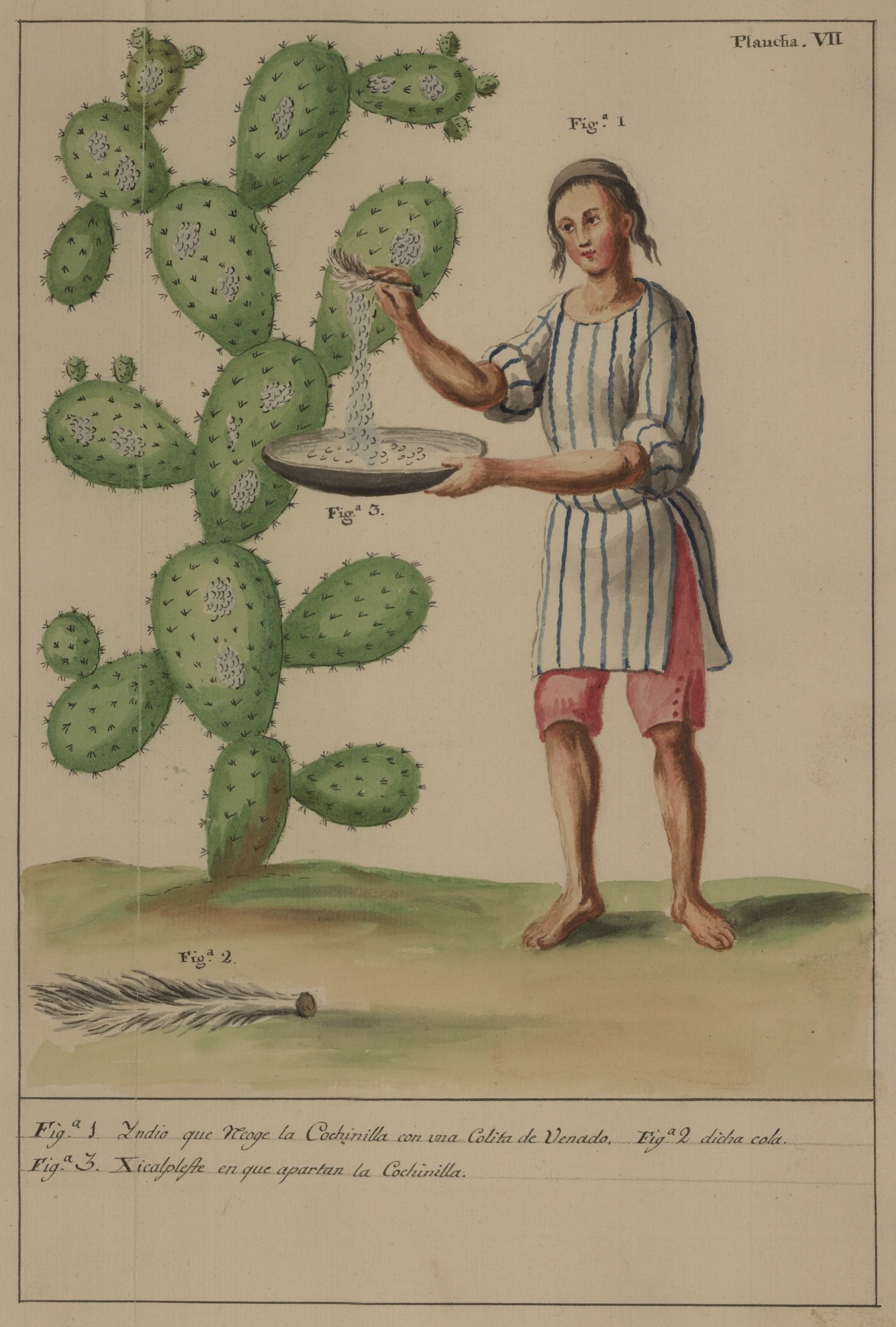

Figure 2. José Antonio Alzate y Ramírez. Memoria sobre la naturaleza, cultibo y beneficio de grana, Mexico, 1777. Real Biblioteca de Palacio, Madrid, Patrimonio Nacional, II/620, plate 7.

These are just a few examples from an abundant corpus of both early modern recipe manuals for makeup and anti-cosmetic tracts that vilified women for wearing it. Besides grotesque descriptions of its dangers and complaints about its ugliness, the most habitual refrain among detractors of makeup was, predictably, its correlation with fabrication, deception, and false beauty. The application of rouge in particular magnified these anxieties because it so disquietingly simulates the natural blush, and because that physiognomic function was long believed to bespeak inherent virtue. Early modern texts of sundry genres accordingly juxtapose these two modes of turning red. Echoing a classical motif already found in Tertullian, a sonnet by Bernardino de Rebolledo (1597–1676) urges women to exchange the superficial contrivances of fucus for their God-given ability to blush, ordaining that “shame paint your countenance.”Footnote 24 In his trademark caustic tone, Francisco de Quevedo (1580–1645) burlesques a woman rubbing rouge on her cheeks, describing the act as applying “prosthetic shame” (“vergüenza postiza”).Footnote 25 Polemicists in England as well as in Spain, such as Thomas Tuke (ca. 1580–1657), Richard Brathwaite (ca. 1588–1673), and Francisco Santos (1623–98), cavil at how rouge overlays, shrouds, and nullifies nature’s blush, with Santos grumbling that women who use it must be without shame, “since their own color can never be seen.”Footnote 26 Likening made-up women to the devil who disguises himself as an angel, Juan de Zabaleta (ca. 1612–ca. 1667) inveighs against the chromatically layered fiction in which “the neckline is underneath alabaster, white underneath coral, pallor underneath roses…and underneath snow, darkness,” all while abiding the “horror” of “cheeks without blood.”Footnote 27 And Antonio Marqués’s (ca. 1570–1649) Afeite y mundo mujeril (Cosmetics and the world of women, ca. 1626) dedicates an entire chapter to how “the greatest makeup and beauty for women is shame,” which summons “from the heart the purest and finest blood in order to grace and embellish the face…revealing there its rubies, its blood and milk.”Footnote 28

The most salient difference between these bimodal forms of blushing, aside from their etiologies, is temporal: while the dynamic contraction and dilation of subdermal capillaries can display transient variations of color instantly, cosmetics fix the redness in place until it is removed, touched up, or gradually worn away by perspiration or contact with other surfaces or materials. Anti-cosmetic tracts seized on this tenuous permanence to fault made-up women both for their static, unchanging demeanor and for the precautions they took to preserve it. Baldassare Castiglione’s (1478–1529) Il cortegiano (Book of the courtier, 1528) declares “how much more attractive” is a woman with “her own natural color, a bit pale, and tinged at times with an open blush from shame or other cause,” contrasting her with a “woman so plastered with [makeup] that she seems to have put a mask on her face and dares not laugh so as not to cause it to crack, and never changes color except in the morning when she dresses; and, then, for the rest of the entire day remains motionless like a wooden statue and shows herself only by torchlight, like wily merchants who display their cloth in a dark place.”Footnote 29 According to this male, courtly gaze, what women forfeited in cosmetic control they gained in sprezzatura, the allure of an apparently effortless beauty. Scholars like Patricia Phillippy and Edith Snook have nonetheless demonstrated how painting became for women a vector of oppression as well as agency.Footnote 30 If makeup “allows women to rewrite the texts that men attempt to read on their faces,” as Iyengar proposes, then it may even be the case that “women painted precisely in order to hide their blushes.”Footnote 31

But with regard to race, studies on facial painting, with important exceptions, have been oddly colorblind, despite Kim F. Hall’s having observed long ago not just the gendered but also the racial implications of texts on cosmetics.Footnote 32 Rouge in particular summons race in at least two ways. First, as Marinello’s and Sforza’s prescriptions for fair skin suggest, Petrarchan idealizations of whiteness are inseparable from redness, even as they elide the more subtle, and often more insidious, assumptions of whiteness as a neutral, unmarked, and unraced norm. In early modern writings, the cosmeticized blush’s link to pallor is more overt than that of the natural blush, whose interface with white skin tends to be but implicit. Yet it is this very fixation on nature’s mechanism for turning red that simultaneously relies on and reinforces the idea of whiteness as similarly natural and, by inference, more desirable. In a 1633 letter on the qualities of a marriage, Quevedo claims that “in whether she is white or dark-skinned…I place no satisfaction or esteem whatsoever; I only want, if she be dark-skinned, that she not make herself white, since of lies one must be more suspicious than enamored.”Footnote 33 Denigrating makeup as a deceitful ruse, Quevedo endorses nature over whiteness, yet the letter’s seeming ambivalence toward skin tone does not attenuate the prestige of whiteness. That racial prestige is just what enables the force of his comparison, casting women who paint as rhetorically inferior even to those whose complexion—whether due to race, ethnicity, or class—would exclude them from early modern ideals of beauty.Footnote 34 Denunciations of makeup’s potential to conceal and deceive, moreover, betray a latent desire, as Kimberly Poitevin perceptively argues, “to recuperate ‘natural’ skin color as a reliable racial marker and to begin constructing race as a category that was no longer fluid, but unchanging and essential.”Footnote 35

The second principal way in which the cosmetic blush intersects with race derives from the origins of its manufacture, in what Jean-François Lozier calls “the transatlantic cosmetic encounter.”Footnote 36 Rouge could be fashioned from ingredients long known to Europe, such as red ochre, alkanet, kermes, lac, madder root, cinnabar, saffron, and safflower, making it affordable enough that Henry Peacham (ca. 1576–ca. 1643) could declare in the mid-seventeenth century that “for a penny, a Chamber-maid may buy as much Red-oaker as will serve seven years for the painting of her Cheeks.”Footnote 37 But red cosmetics could also be elaborated from raw materials newly extracted from the Indies, including annatto, brazilwood, and carmine. Culled from the American cochineal beetle, which feeds on cacti native to the Andean highlands and present-day Southern Mexico (fig. 2), carmine’s brilliant crimson had graced pre-Columbian codices and textiles for centuries. By the late 1500s, the dyestuff was traded around the globe in vast quantities, becoming so lucrative for the Spanish Empire as to vie with those other prized colors of gold and silver.Footnote 38 What was commonly known as Spanish paper, and was also available in leather and wool forms, was a small pad infused with cochineal or other dyes that, when moistened, could be rubbed on the cheeks to apply blush with modish, portable convenience.Footnote 39 Spanish paper from Seville and Granada was especially prized, though on the Peninsula it was known simply as papel de color. Curiously, in a scene from Santos’s Día y noche de Madrid (Day and night of Madrid, 1663), a picaresque chronicle of urban vice, a Celestina-like figure selling cosmetics boasts that the rich crimson of a papel de color is “oriental, made with murex blood, and…found in but one part of Madrid.” Making the sale for 2 reales, the charlatan claims that she acquired the product from a foreigner because “in Madrid they don’t know how to make it so well” and “by being a thing of Foreign Artifice, it is enough to give it value.” Yet the text later divulges not only that she had purchased the papel de color for much less from a Portuguese man in the central Puerta del Sol, but also that the anti-wrinkle cleanser she was hawking was actually water from the lavatory of a tavern where she had stopped to drink a pint “that gives better colors” than her Spanish paper.Footnote 40

If these products’ foreign origins, whether imagined or real, made rouge more desirable, then they also exerted pressure on race-making and nation-building efforts, particularly in England. Just one slice of the growing demand for dispensable imported goods spurred by the East India Company, foreign cosmetics in early modern England became an abiding outlet for grievances over the threat of global trade to national and racial identity. “Cosmetics worn by women,” as Farah Karim-Cooper explains, “were undoubtedly a reminder of the permeability of the flesh and the permeability of England’s borders.”Footnote 41 Thus, when the trend of rouge mingled with that of encyclopedic, globe-spanning compendia, it was often accompanied by ethnocentric censure. Francis Bacon (1561–1626) declared in 1626 that, “as for the Chineses, who are of an ill Complexion (being Olivaster), they paint their Cheeks Scarlet,” while remarking in the same breath that “Barbarous People that go naked, do not only paint themselves, but they pounce and rase their skin.”Footnote 42 By racializing skin tone, Bacon suppresses the obvious parallels with English users of blush to instead blazon red cheeks as a signpost of cultural difference. Influenced by Bacon, the Anthropometamorphosis (1650–53) of John Bulwer (1606–56) catalogues, and frequently harangues, the cosmetic practices of people from around the world. In his entry on the “Cyguanians,” first described in Pietro Martire d’Anghiera’s (1457–1526) New World chronicle of 1516 as “all paynted and spotted with sundry coloures, and especially with blacke and redde,”Footnote 43 Bulwer opines, “I am sure they violate and impudently affront Nature, thus to obscure the Naturall seat of shame and modest bashfulnesse with their painting; so that the flushings of the Purple blood, which nature sends up to releive in the passion of Shame, cannot significantly appeare in their Native hue.”Footnote 44 In his moral panic about how Indigenous forms of facial painting could obfuscate the natural blush, though, Bulwer’s ultimate concern lay not so much with the customs of faraway lands as it did with “our English Ladies, who seeme to have borrowed some of their Cosmeticall conceits from Barbarous Nations.”Footnote 45

Rouge thus opens a window onto the varying social, intercultural, and racial anxieties triggered by the expanded global trade routes that made it increasingly available. What early modern European writings on cosmetics share are misgivings over an unnatural order that is magnified in the gendered and racialized act of blushing. These texts compulsively link whiteness and redness only to expend considerable effort to distinguish between the natural and artificial means of attaining two-tone skin. Yet such distinctions, as the anecdote of Alberti’s Gianozzo betrays, were sometimes more dubious in practice. Even as attempts to mitigate the popularity of painting enhanced the cachet of an apparently genuine blush, they did little to erode the tantalizing appeal of rouge. What I want to suggest, in fact, is that the more such discourses attempted to reassert the difference between artificial and natural blushing, the more they inadvertently reinforced the link between the two, such that the physiological and ostensibly involuntary act of reddening came to be colored, as it were, by shades of performativity. If, as Poitevin argues, English women’s use of cosmetics “encouraged the identification of race with skin color…and helped establish whiteness as the English complexion,” then “by constructing this identity through obviously artificial means, women also exposed the artificiality of race itself.”Footnote 46 Juxtaposing the artificial blush and the natural blush allows one to see not only that such distinctions were rather more precarious than is typically assumed but that this instability likewise troubled the consolidation of early modern racial identities of all stripes.

BLUSHING AND BLACKNESS

By far the most trendsetting consumer of cosmetics in early modernity was Queen Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603), whose chalk-white face and florid cheeks became nothing short of iconic. Near the end of her reign, when her liberal daubing of rouge had thoroughly installed Elizabethan standards of beauty, she would promote the deportation of all so-called “blackamoors” from her realm. The policy followed closely on the heels of William Shakespeare’s (1564–1616) creation of the Black antagonist Aaron the Moor in Titus Andronicus (ca. 1588–93). Spurning the “treacherous hue, that will betray with blushing / The close enacts and counsels of thy heart,”Footnote 47 Aaron derides the white characters, whose translucent skin gives away their moral distress (“What, what, ye sanguine, shallow-hearted boys, / Ye white-limed walls, ye alehouse painted signs!”), while claiming that his own pigmentation negates the blush and therefore renders his inwardness enviably opaque: “Coal-black is better than another hue / In that it scorns to bear another hue.”Footnote 48 Later, when a Goth asks him, “What, canst thou say all this and never blush?” Aaron, donning the familiar racist cloak of animalizing language, replies, “Ay, like a black dog, as the saying is.”Footnote 49 Relying once again on the classical concept that the blush of shame denotes a self-consciousness redolent of virtue, the villainous Aaron’s complexion makes him inscrutable and—more consequential for the graphically violent plot of the early tragedy—allows him to operate with impunity.Footnote 50

If Shakespeare deprives Black bodies of both facial legibility and moral integrity, then his countryman Thomas Wright (1561–1624), in the preface to Passions of the Minde in Generall (1604), inverts the conceit. “The very blushing…of our people,” he exults, “sheweth a better ground, wherevpon Vertue may build, than certaine brazen faces, who never change themselves, although they committe, yea, and be deprehended in enormious crimes.”Footnote 51 Echoing more general suppositions of a coeval European fascination with physiognomy, Wright’s portrayal of the blush ascribes it a generative as well as denotative function, whereby the skin’s capacity to turn red not only signals moral probity but also enables it. Notably, however, Wright was singling out not Elizabeth’s favored scapegoat of “blackamoors” but Spaniards and Italians, whose ruddy complexion, he reasoned, abetted their reputation for immorality and delinquency. Such aspersions are rather predictable in the context of late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century European imperial rivalry and English domestic and foreign policy. As embodied by Shakespeare’s Venetian characters Shylock and Othello, the cosmopolitan Republic of Venice was known for its diversity, while the enmity that had long festered between England and Spain incited the racialization of the latter as an indiscriminate lair of Moors, Muslims, and Black Africans, making the Mediterranean nations an irresistible foil for ethnonationalist fantasies of a pure, white Northern Europe. Wright’s text appeared the same year that the recently coronated James I brought about a peace treaty between England and Spain, and with it a renewed Hispanophobia rooted in hysteria over the prospect that Iberian ethnic diversity could make its way to English shores. If one interprets the anti-Spanish propaganda known as the Black Legend, as Fuchs suggests, not just “metaphorically, with black as a figure for Spain’s cruelty and greed in the New World,” but also as referring “in unambiguous terms to Spain’s racial difference, its intrinsic Moorishness,” then Wright’s denial of blushing to Spaniards takes on another dimension of meaning.Footnote 52 Conceptions of the blush—what its redness signified and who was granted or denied access to it—therefore index larger policy-, nation-, and race-based discourses.

Galenic humoralism notionally allowed for the free circulation of blood irrespective of phenotypic distinctions of skin tone, even if the sanguine type was associated with a ruddiness and sometimes an underlying whiteness. The paradigm’s revival in Juan Huarte de San Juan’s (1529–88) protopsychological Examen de ingenios (Examination of men’s wits, 1575) also eschewed the racial determinism of blood purity in favor of a strictly environmental and temperamental basis for human difference. Yet despite the text’s popularity—it was translated to English in 1594 and ran through dozens of editions across the Continent for the next two centuries—humoral theory did little to dispel the persistent Anglo-American stereotype that nonwhite faces were incapable of blushing. Well into the eighteenth century, Charles White (1728–1813) would ask rhetorically, “In what other corner of the globe shall we find the blush that overspreads the soft features of the beautiful women of Europe, that emblem of modesty, of delicate feelings, and of sense?…Where, except on the bosom of the European woman, two such plump and snowy white hemispheres, tipt with vermillion?”Footnote 53 Shortly after drafting the United States Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), in comparing whiteness with Blackness, similarly couched the dehumanizing privation of blushing in a question of aesthetics: “Are not the fine mixtures of red and white, the expressions of every passion by greater or less suffusions of colour in the one, preferable to that eternal monotony, which reigns in the countenances, that immoveable veil of black which covers all the emotions of the other race?”Footnote 54 White’s and Jefferson’s interrogatives could qualify as examples of how “black skin, rather than red cheeks, emerge [sic] as raced,” as Angela Rosenthal puts it, while white skin becomes “the precondition of emotional legibility” and designates, I would add, the attendant trait of a refined, morally superior sensibility.Footnote 55 In other words, the withholding of blushing from Black skin was rooted not in humoralism, biology, or early science but in culture—a culture for which it proved expedient to link Blackness with moral vacuity and indifference. Such cases underscore how the blush was reliable in abetting transhistorical projects of racial consolidation, yet also, like the concept of race itself, highly adaptable to the demands of a given political regime, whether in the service of nation-building, imperialism, chattel enslavement, or white supremacy.

Yet even within the frame of a tightly periodized early modernity, a transnational approach reveals that the blush was subject to far more differentiated assumptions about its relationship to race and skin color. Luis Pacheco de Narváez’s (1570–1640) influential fencing manual Libro de las grandezas de la espada (Book of the greatness of the sword, 1600) advises opponents of an apparent multitude of Black swordsmen in Spain on how to contend strategically with the “black, or brown, veil” obscuring the telltale facial complexions that otherwise disclose one’s humoral disposition and corresponding martial proclivities.Footnote 56 Unlike Jefferson’s degrading “veil of black,” however, aspersions are conspicuously absent in Narváez’s text. Instead, in what Manuel Olmedo Gobante suggests might constitute “the first scientific typology of Black Africans,” Narváez instructs fellow swordsmen to fixate on signs other than skin color to intuit the humoral bearing of Black challengers, who were revered for their prowess. For the choleric, the most lethal, these alternative signs include “courage, gravity, pride and social intelligence, neatness, and articulateness,” traits “that were typically associated with nobility at the time.”Footnote 57 Narváez’s treatise confirms that stereotypical assumptions about red cheeks and Black skin were not entirely foreign to Spain, yet also that the presumed absence or invisibility of the blush did not necessarily entail the moral corruption imagined by Wright or embodied in Shakespeare’s Aaron.

For Titus Andronicus’s character, one encounters a dramatic foil of sorts in Diego Jiménez de Enciso’s (ca. 1585–1634) Juan Latino (first published 1652, but likely written in the early 1620s), inspired by the historic figure of the same name (ca. 1518–ca. 1595), an enslaved Afro-descendant man, living in Granada, who went on to occupy a professorship in Latin and to write the epic poem Austrias Carmen (1573).Footnote 58 With the fraught Moorish uprising of the Alpujarras as a backdrop, Enciso’s play dramatizes Latino’s determination to overcome manifestly anti-Black racism and attain both his academic appointment and betrothal to a young white noblewoman, Doña Ana. Though the attraction is mutual, she struggles to reconcile her desire with the social and familial pressures that, by all indications, would proscribe their biracial union; Latino, meanwhile, must also contend with an enslaver unwilling to liberate him from bondage. Latino’s demeanor betrays these anxieties as he prepares to confess his love to Doña Ana, and in an aside he admits to feeling embarrassed. That his complexion has changed is implicit in her response—“Are you embarrassed?”—to which Latino replies, “How could you tell, my lady? Because, even if I were embarrassed, I cannot blush.”Footnote 59 In their psychologically evocative exchange, Latino appears to blush only to question Doña Ana’s recognition of the act’s visual evidence, a disavowal at odds with his own admission of embarrassment, to which only the audience is privy. While Titus Andronicus and Juan Latino both charge Black characters with the dialogue that will divest them of the ability to turn red, the latter play’s protagonist claims that he cannot blush almost as a self-deprecating strategy to temper the discomfort naturally induced by blushing itself. Hewing to generic convention, Enciso’s play, it must be acknowledged, often leverages Latino’s complexion as an object of mirth, while trafficking in demeaning, racially charged stereotypes. Nevertheless, there is a tantalizing whiff of irony in the intellectually and rhetorically gifted Latino’s self-abnegating claim, as if it were at once a tongue-in-cheek dismissal of a racial cliché and a latent defiance of a lifetime’s accumulation of other forms of race-based disenfranchisement. Against the backdrop of what Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Maria Wolff long ago described as Juan Latino’s “many incongruous notes,”Footnote 60 such a reading is bolstered by the fact that Latino confesses to blushing on no fewer than four additional occasions throughout the play.Footnote 61

Indeed, seventeenth-century Spanish drama routinely staged a variety of nonwhite characters who mantle as a matter of course. In Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s (1648–95) Los empeños de una casa (House of desires, 1683), set in Toledo, the servant Castaño, native to the Americas and whose name (“Chestnut”) already points to skin tone, calls himself “morena,”Footnote 62 a term that could denote an ambiguous “dark-skinned” complexion as well as someone of African descent.Footnote 63 The character adopts the feminine form of the adjective because, in a noted scene, he fashions an elaborate disguise by adorning himself, piece by piece, with women’s clothing, accessories, and cosmetics, breaking the fourth wall by turns to involve the audience in the extended act of dressing up and undressing. When he comes to rouge, Castaño proclaims, “Blush? I don’t need it, since this effort, perforce, will have me all shades of red by being a maiden of shame.”Footnote 64 Other Spanish plays of the period assign starring, and less overtly comical, roles to Afro-European characters. Luis Vélez de Guevara’s (1579–1644) Virtudes vencen señales (Virtues vanquish visual signs, ca. 1617) stages the plight of Filipo, who is born Black to white parents because, following an early modern fancy of visual imprinting, on the night of his prodigious conception the gaze of his father, the king, was distracted from the carnal act by a tapestry featuring the Ethiopian Queen of Sheba. Though his skin color consigns him to years of solitary imprisonment, when he finally ascends to his rightful place on the throne the moral essence of his noble blood prevails, even in the face of a plot by the character Almirante to overthrow him. When confronted, the traitor refuses to raise his sword in defense, instead prostrating himself before the king and placing his life at the mercy of sovereign authority. So moved is Filipo by the display of reformed deference that he blushes in shame, ordering Almirante to rise while offering clemency for his crimes.Footnote 65 Lacking any semblance of nobility, in contrast, the titular character in Andrés de Claramonte’s (ca. 1580–1626) El valiente negro en Flandes (The valiant Black man in Flanders, ca. 1625) is an Afro-Hispanic soldier named Juan de Mérida, who, though enslaved at birth, gains his freedom and travels to the Low Countries to fight in the Eighty Years’ War (1566–1648). The drama’s action, however, concerns itself less with the attacks by the opposing Dutch rebels than with those of his own countrymen, who, motivated by racial animus and jealousy of his valor, strive repeatedly to humiliate him. Though these attempts mostly fail, the Black soldier nonetheless divulges that he, like Enciso’s Juan Latino and Vélez’s Filipo, has experienced feeling “corrido.”Footnote 66 Notably, though this term is roughly equivalent to “ashamed,” an emotional state in which the blush is but implicit, the lexicographer Sebastián de Covarrubias was insistent in ascribing its etymology to the act of blood running to the face.Footnote 67

The historian of emotion William Reddy would deem such “first-person, present tense emotion claims” “emotives,” or “instruments for directly changing, building, hiding, intensifying emotions.”Footnote 68 An utterance like “estoy corrido,” voiced by Black characters in the plays by Enciso, Vélez, and Claramonte, may thus possess an illocutionary, extradiscursive force that erodes more dominant European discourses depriving dark skin of the blush. There are early modern anecdotes of actors who ostensibly were capable of blushing and blanching at will for the demands of a given scene, an extraordinary theatrical ability that likewise undermines the fixation on the “natural” blush.Footnote 69 Yet for early modern playgoers, these examples of a “spoken blush,” as Emma Whipday has recently argued, were perhaps more consequential than a visible change in the performer’s complexion.Footnote 70 A number of factors in both English and Spanish playhouses would have mitigated the possibility of discerning such minute visual details as chromatic alterations of the face.Footnote 71 In larger amphitheaters, especially, audience members could be seated or standing some distance from the action; their line of sight was sometimes obstructed by posts, pillars, and fellow spectators; the air was regularly clouded by smoke from tobacco and candles; and the stage was poorly illuminated. Whether in the form of blackface, whiteface, or what Iyengar dubs “blushface,” the use of stage makeup, too, would have curtailed, if not altogether eliminated, an audience’s capability to see variations of color on an actor’s skin.Footnote 72 Thus, an utterance such as “estoy corrido,” what Karim-Cooper would call a “gestural annotation,”Footnote 73 not only cues spectators on a character’s psychophysiological state but, on the early modern stage, also becomes an unwitting leveler of racial difference, enabling people of color to reclaim blushing in the face of looming European stereotypes that proverbially stripped them of that ability. Like the widespread use of cosmetic rouge, blushing could be performative and, thus, could exert pressure on normative demands for a “natural” red on white cheeks.

In no way should this interpretation neglect the racially violent realities of early modern Iberia or the larger, albeit implicit, messaging of the plays themselves. Characters like Claramonte’s Juan de Mérida and Enciso’s Juan Latino, critically, would qualify as what Ndiaye deems “built-in pressure outlets,” or “success stories for allegedly exceptional black subjects that made a slaving society look like a fair system of racial meritocracy.”Footnote 74 Cast as exceptional Black men, to achieve whatever hard-won acceptance their social milieu sees fit to allot to them they must first espouse values and excel at behaviors that are anything but racially neutral.Footnote 75 In his brief analysis of El valiente negro in Black Skin, White Masks (1952), Frantz Fanon (1925–61) was categorical in stating that Juan de Mérida must “furnish proof of his whiteness to others and especially to himself.” “Axiologically,” according to Fanon, “he is a white man.”Footnote 76 As they struggle for greater agency, these Black characters must perpetually contend with what Miles P. Grier would call “white interpretive authority,”Footnote 77 or, in the words of Elizabeth R. Wright, “a white-European impulse…to gauge their individual merits with a scale whose calibration mechanism is white and European.”Footnote 78 That the blush remains subject to this authority is epitomized in Lope de Vega’s Auto sacramental de los cantares (1644), a religious play based on Luis de León’s Cantar de los cantares (1561), itself a translation and exegesis of the biblical Song of Solomon. Dramatizing the locution of nigra sum sed formosa, Lope’s rendition presupposes no dissonance between the Shulamite spouse’s self-ascribed Blackness and her “shameful” cheeks.Footnote 79 Yet, while explaining the origins of her “Ethiopian beauty,” the character promises to be “more whole and purer than snow.”Footnote 80 In contrasting the Blackness of her complexion with the whiteness of snow, a detail absent in both the Song of Solomon and Luis de León’s extensive commentary, the play erects an implicit racial-moral hierarchy that essentializes Blackness as a debased condition the spouse must overcome in order to attain the sexual purity that is synonymous with whiteness.

To be clear, and as this example makes evident, the blush is not an elixir or nostrum that, when it emerges on a nonwhite individual’s face, somehow inoculates the blusher against other forms of race-based discrimination. Part of the blush’s power as a signifier, as suggested previously, is precisely its capacity to register the embodied trauma of humiliation to which all manner of ethnoreligious and raced others were habitually subjected, whether through the legally codified and ecclesiastically endorsed body of shame punishments or through popular, spontaneous forms of ridicule. Historical sources reveal an obvious yet no less troubling paradox whereby a blush on Black skin would not have been triggered were it not for the racial hostility enabling it in the first place. The priest Juan de Santiago (fl. ca. early seventeenth century) testified that during Seville’s Holy Week processions of 1604 spectators mocked, whistled at, and “made other shameful noises” at the members of the Black confraternity that was parading through the streets for the solemn occasion; these insults made them “blush with shame” and react in kind.Footnote 81 In response to the pandemonium, later that year city authorities shuttered the Black confraternities, effectively placing the onus for civility and decorum squarely on their members, not on their racist antagonists.

Likewise, the military captain and chronicler Alonso Vázquez (ca. 1556/57–1615), in his testament of the early stages of the Eighty Years’ War, recounts the historic case in 1580 of the Spanish “mulatto” Alonso de Venegas (fl. ca. 1570–ca. 1585), a fellow soldier who, not unlike Claramonte’s fictional Juan de Mérida, had distinguished himself for his gallantry on the battlefield.Footnote 82 Hateful and envious of his stature, an officer goaded the other men of his company to revile Venegas for his Blackness, and, when the offended Venegas challenged him to a duel, the officer refused, claiming that Venegas’s skin color made him an illegitimate opponent.Footnote 83 According to Vázquez, so humiliated was Venegas by the insults and his powerlessness to honorably avenge them that, in a stark deviation from Claramonte’s script, he defected to the opposing camp, whose embrace and promotion of the Black soldier delivered immediate gains for William of Orange’s rebels, much to the detriment of the Spanish. What is significant is that, as in the account of the Black confraternities, the text matter-of-factly applies to Venegas the terms “corrido” and “afrenta,” whose lexical definitions, as noted above, explicitly invoke the action of blood rushing to the face.Footnote 84 Though both texts appear to portray a degree of sympathy for the plight of the Black men who suffer repeated acts of racist debasement, they cannot be said to do so without ulterior motives: Santiago’s testimony aims to restore the dignity not of the fraternal members themselves but of the Catholic ritual in which they were participating; Vázquez’s account, likewise, advances a lesson more practical than moral, underscoring the need for order and mutual respect, lest discord among the ranks become a tactical liability.

Once again, the literary retention of Black blushing does not redeem or diminish the racial violence of early modern Europe’s Atlantic-facing empires, nor does it herald a necessarily reparative reading of the Afro-diasporic cultural representations that of late are beginning to receive their critical due. What the blush does allow, rather, is a micro-perspective on what Ndiaye calls “racecraft,” or “the role that performative practices played in shaping new racial formations,” and on how “early modern performance culture did not passively reflect the intercolonial emergence of blackness as a racial category but actively fostered it.”Footnote 85 The stereotyping of Afro-Europeans as incapable of blushing was, like the use of foreign cosmetics, an uneven process intertwined with larger national and translocal interests. That Afro-descendants in seventeenth-century Spanish drama tend to retain their ability to blush more than their English counterparts supports Ndiaye’s argument that by that time Spain, unlike England, had shifted from a “diabolical script of blackness”—think Shakespeare’s Aaron the Moor—to a “commodifying script of blackness,” due to entrenched economic demands of a society trafficking in enslaved people and no longer needing “to hear exclusionary stories about blackness.”Footnote 86 These ideological differences also align with Baltasar Fra Molinero’s assertion that Iberia’s relatively high population of Black Africans and Muslim and Jewish converts led to a depiction of racial and ethnic minorities in Spanish fiction as less exoticized, albeit far from fully integrated, national subjects.Footnote 87 In their effort to promote “natural” complexion, some Spanish, and even English, writers treated Blackness as an authentic, uncosmeticized ideal.Footnote 88 “In the Spanish comedia,” as Emily Weissbourd contends, “the social ascent of Black characters is enabled by explicitly presenting Blackness as a less threatening form of difference than ‘impure blood,’ in part because Blackness (unlike the ‘taint’ of Jewish or Moorish ancestry) cannot be concealed.”Footnote 89 Although there is anecdotal evidence in travel narratives to suggest, in point of fact, that foreigners applied cosmetics to pass as white Europeans,Footnote 90 the spontaneous volatility of blushing meant that it could serve as material proof of an unmediated bodily surface, whatever its original color. Dramatic stagings of Black blushing disclose that that ability, or the fantasy of its absence, has less to do with fledgling conceptions of physiology than it does with shifting, culturally contingent demands of colorism and learned scripts of everyday performance. The color red at once arbitrates and unsettles those of black and white.

CONCLUSION

The cases I have surveyed here reclaim early modernity as a pivotal moment for the conceptualization of blushing, and for how it reflected, refracted, and mediated embryonic understandings of racial difference in all its complexity. Long before Darwin’s fascination with blushing, the rush of blood to the cheeks was not simply a scientific matter to be settled by dermatological, hematological, or physiological inquiry but a capacious signifier whose meaning changed as it circulated through a capillary-like network of historical, philosophical, literary, and dramatic texts. These writings simultaneously normalized, pathologized, and mythicized the meanings of the blush, and persisted in encoding its presence as white European and its perceived absence as a symptom of abnormality and inferiority. Turning red nonetheless was conceived as neither universal nor exclusively within the purview of whiteness; instead, it varied according to a protean set of intercultural and transnational norms, thus mirroring the insidious malleability of race itself. The blush offers a comparative means for understanding as well as undoing these more global efforts at race-making. Its ligature with various dimensions of performance not only defied assumptions that it was a wholly involuntary response, unmediated by either conscious thought or culture, but also troubled nascent gambits at racial categorization that their proponents expected the blush to help consolidate. On one hand, the more that early moderns attempted to rehabilitate an innate and therefore legitimate blush, to insulate it against imposture, and to preserve its power as a racial indexer, the more they unwittingly reinscribed its affiliation with theatricality, and thus exposed race itself as a masquerade. Yet, on the other hand, reconstructing the cultural history of turning red—discursive, performative, and transitory though it is—restores an imprint of the visceral, bodily shame and material degradation suffered by all manner of raced others. In this vexing dialectic of presence and absence, the blush registers at once the stigma with which they were branded and the humanity they were denied.

Paul Michael Johnson is an Associate Research Professor in the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures at Johns Hopkins University. A specialist in the literary culture of early modern Spain, he is the author of Affective Geographies: Cervantes, Emotion, and the Literary Mediterranean (University of Toronto Press, 2020), as well as essays in journals such as PMLA, Atlantic Studies, and Exemplaria. His current book project studies the racial politics of blushing across the early modern world.